- 1GIFT Business School, GIFT University, Gujranwala, Pakistan

- 2Riphah School of Business and Management, Riphah International University (Lahore), Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan

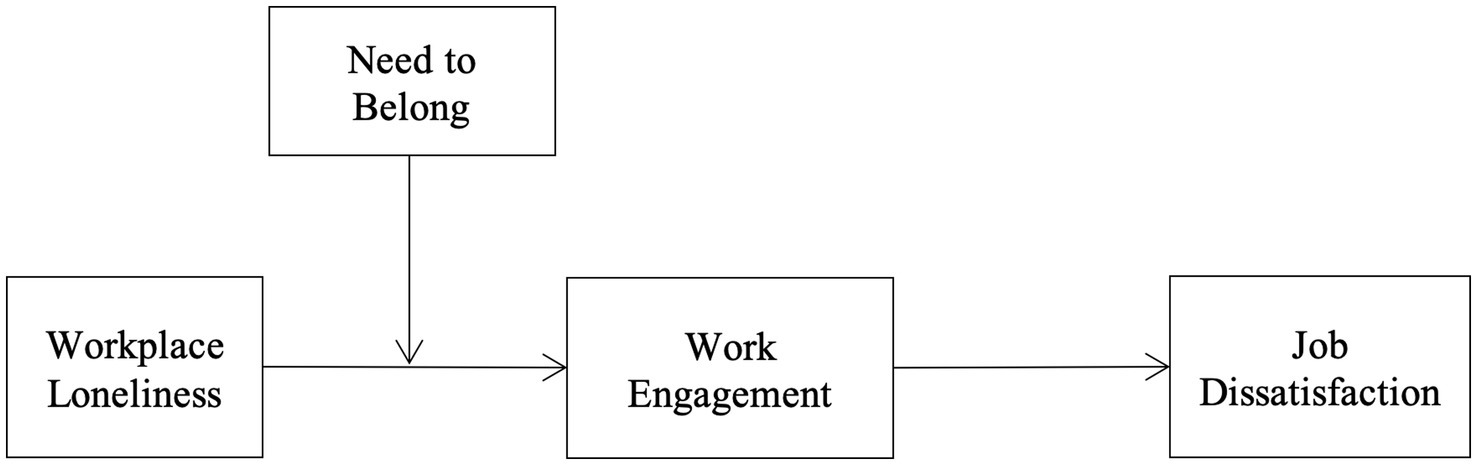

This study investigated the effect of workplace loneliness on work-related subjective well-being by proposing work engagement as an explanatory mechanism in the workplace loneliness—job dissatisfaction relationship. Moreover, the study examines the need to belong as a coping mechanism in the relationship between workplace loneliness and work engagement. Specifically, the study posits that workplace loneliness reduces the positive and fulfilling state of work engagement that in turn increases job dissatisfaction and that this mediation depends on the employee’s level of need to belong. Data were collected from employees (N = 274) working in diverse domestic and multinational organizations in Lahore, Pakistan. Results showed that workplace loneliness reduced the work engagement of lonely individuals that in turn increased their job dissatisfaction. However, the deleterious effect of workplace loneliness on work engagement was weaker for individuals having a higher need to belong. These findings have important implications for organizations wishing to mitigate the harmful effects of workplace loneliness on employees’ subjective well-being.

Introduction

In inclusive organizations, people are valued regardless of their group membership, status, or individual differences. Inclusive workplaces align and make use of employees’ talents through their broad participation and the systems driven by equity. However, this desired state of the inclusive organization is seriously hampered when there is a deficiency of strong and stable relationships among organizational members making them feel lonely and excluded. Workplace loneliness is dissatisfaction in social relationships at the workplace (Lam and Lau, 2012) and is important for employees’ personal and workplace life (Wright, 2012). Employees spend substantial time at the workplace, however, it is not well understood how deprivation of their belongingness needs affect various workplace outcomes and what coping mechanisms can help to mitigate its negative outcomes (Anand and Mishra, 2021). Although the detrimental effects of loneliness on people have been extensively studied in psychology, research on employee workplace loneliness is at an early stages in the organizational behavior literature (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2018) and requires further investigation.

Psychologists believe that, like physical pain, loneliness is a social pain causing serious harm to the cognition, emotion, behavior, and well-being of individuals (Kalil et al., 2010). Research focusing on the outcomes of workplace loneliness has revealed its deleterious effects on various employee outcomes. For instance, where lonely employees demonstrate a decrease in creativity (Peng et al., 2017), in-role and extra-role performance (Lam and Lau, 2012; Ozcelik and Barsade, 2018), affective organizational commitment (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2018), they also show increase in job burnout (Omar et al., 2020; Anand and Mishra, 2021), intention to leave (Chen et al., 2016), and unethical behavior (Gentina et al., 2018). The Covid−19 pandemic has forced many employees performing jobs in different professions to work from home and remain in social isolation thus deteriorating their well-being (Gabr et al., 2021; Nishimura et al., 2021; Chirico et al., 2022). Thus, further investigation is needed as how workplace loneliness negatively affects employees’ work-related well-being, which is an underexplored area in organizational research (Anand and Mishra, 2021; Andel et al., 2021; Wright and Silard, 2021). To address this gap, we examined how workplace loneliness enhances job dissatisfaction which is detrimental for both the employees and the organizations and results in turn over and work withdrawal (Zhou and George, 2001).

Drawing from the employee engagement theories (Kahn, 1990; Bakker and Demerouti, 2008), this study aims to investigate whether workplace loneliness impacts the work-related well-being of employees by decreasing their work engagement and consequently increasing their job dissatisfaction. Researchers are interested to identify factors that help to tone down the negative effects of workplace loneliness (Andel et al., 2021). In response to this call, we introduce need to belong as a moderator in the workplace loneliness—work engagement relationship and contend that the need to belong is highly relevant personal resource that helps employees to cope with work loneliness. Employing social reconnection theory (Maner et al., 2007), we investigate whether the need to belong, as a personal resource and an individual difference, interacts with workplace loneliness to influence work engagement. This study deepens our understanding of how and when the need to belong would weaken the negative relationship between workplace loneliness and work engagement.

We aim to broaden the understanding of workplace loneliness by making mainly three contributions to the HR literature. First, by examining the mediational role of work engagement in the loneliness—dissatisfaction relationship (Anand and Mishra, 2021), we advance organizational research by explaining why lonely individuals are dissatisfied with their work. Second, we respond to the calls by earlier researchers to investigate factors that can help employees to tone down the effects of workplace loneliness (Andel et al., 2021; Wright and Silard, 2021). Third, this study was conducted in a developing country that has a collectivist culture and is an underrepresented region in management research. To address these questions, this study thus proposes and tests a moderated mediational model of workplace loneliness that is rooted in the engagement and social reconnection theories (Figure 1).

Theory and hypotheses

Workplace loneliness

Human beings have a natural need for social interaction and close relationships with others. However, individuals experience loneliness if these needs are not sufficiently met (Baumeister and Leary, 1995; Wright and Silard, 2021). Workplace loneliness is defined as “employees’ subjective affective evaluations of, and feelings about, whether their affiliation needs are being met by the people they work with and the organizations they work for” (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2018). It is often the quality rather than the frequency of interpersonal relationships that leads to feelings of loneliness (Wright et al., 2006). In another study, Azambuja and Islam (2019), found that middle managers often experience alienation due to competing work demands and diverse roles, leading to a lack of personal connections and belonging within their organization. It is important to note that although it may appear similar, workplace loneliness is distinct from concepts such as isolation, aloneness, and solitude as it is a subjective psychological state rather than an objective characteristic of an individual’s social environment (Wright et al., 2006; Ozcelik and Barsade, 2018).

The above evidence thus clearly shows that workplace loneliness is a disturbing social aspect of the workplace that needs more attention in research to understand how inclusive organizations can be developed. This study focuses on how loneliness affects the well-being of individuals at work, such as work engagement and job dissatisfaction, and how the need to belong can influence the deleterious effects of workplace loneliness on well-being.

Workplace loneliness and work engagement

According to McKee (2017), the quality of social interaction with colleagues is crucial for bolstering employee happiness and work engagement because employees feel frustrated when they find themselves lonely, invisible to others, and unnoticed. Work engagement refers to the positive and fulfilling work-related mental state characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption in work (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Employee engagement researchers consider the quality of interpersonal relationships at the workplace an important source of work engagement (Kahn, 1990; Halbesleben, 2010; Christian et al., 2011). For instance, Kahn (1990), argues that interpersonal relationships with superiors and co-workers and leadership style promote work engagement by enhancing psychological safety, which is the perception of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks at the workplace (Edmondson and Lei, 2014). Psychological safety is associated with work engagement in empirical research (May et al., 2004; Halbesleben, 2010).

It can be argued that workplace loneliness is likely to decrease work engagement by reducing psychological safety because lonely employees have a fear of rejection by others and consider it risky for their status in the organization by putting in any further efforts to build relationships with others (Kahn, 1990). Evidence shows that quality relationships reflected by organizational, supervisory, and coworker support are related to work engagement via psychological safety (May et al., 2004; Rich et al., 2010). It is thus likely that the deficiency of high-quality relationships as reflected by the subjective experience of loneliness will reduce work engagement through a decline in psychological safety.

Another stream of engagement research rooted in the job demands-resources theory (Hakanen et al., 2006; Bakker and Demerouti, 2008; Bakker and Bal, 2010; Hu et al., 2011) argue that healthy interpersonal relationships with supervisors and colleagues are job resources that promote work engagement by helping employees to achieve their work goals, to reduce job demands, and to stimulate their personal growth, learning, and development. For instance, the relationship between social support from supervisors and work engagement has been found in several empirical studies with a strong association of social support with dedication followed by the vigor and absorption dimensions of work engagement (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004; Hakanen et al., 2006; Llorens et al., 2006; Bakker et al., 2007; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007; De Lange et al., 2008; Schaufeli et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2011). It can thus be expected that as a deficient job resource, workplace loneliness depletes the cognitive and emotional energies of employees needed to achieve work goals and personal development and makes them withdraw from their work engagement consequently. In addition, there is evidence that the experience of loneliness shatters one’s self-confidence and fosters stress and fear (Hornstein and Eisenberger, 2022). Low self-confidence makes individuals doubt their abilities to perform at work and stress mars their engagement. According to Kahn (1990), low confidence reduces one’s psychological availability (i.e., feeling able to use physical, emotional, and cognitive resources at work) that in turn decreases work engagement.

In addition, evidence shows that a work environment that is deficient in opportunities to integrate and relate with others results in distress and makes individuals withdraw and disengage themselves from the such environment to alleviate their loneliness (Russell et al., 1984; Rastogi et al., 2018). Based on the aforementioned logic and empirical evidence, we propose that:

Hypothesis 1: Workplace loneliness is negatively related to work engagement.

Work engagement and job dissatisfaction

Work engagement and job satisfaction are distinct job attitudes (Christian et al., 2011; Albrecht et al., 2015). Therefore, in their causal model of work engagement, Albrecht et al. (2015) and Gong et al. (2020) have mentioned job satisfaction as a positive individual outcome of work engagement. When employees can develop energetic and affective connections with their work life, they engage and deal well with their job demands (Schaufeli et al., 2008). According to Saks (2006), work engagement is associated with employee attitude, behaviors, and intentions at work. Studies have reported that engaged employees are more satisfied, motivated, and committed to their jobs with lower intentions to quit as compared to disengaged employees (Demerouti et al., 2001; Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004). The cost of bearing a disengaged employee has made understanding the consequences of work engagement even more important (Fleming et al., 2005; Rayton et al., 2012).

Engaged employees expect positive work outcomes and can satisfy their needs by engaging themselves in their work (Mauno et al., 2007). Their high level of engagement enables them to experience positive emotions (Schaufeli and Van Rhenen, 2006) and develop positive feedback that fulfills their needs for appreciation, recognition, and success (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008). However, when employees fail to engage with their work then their work life becomes a repetition of motion and certain practices (Hollis, 2015). According to Kahn (1990), actively disengaged employees seem to be physically present yet psychologically absent from their work, they remain unhappy and share unhappiness with others. Such individuals dwell in a withdrawal state where their creativity declines (De Castella and Byrne, 2015), and job dissatisfaction amplifies (Carnahan, 2013). It is thus proposed that:

Hypothesis 2: Work engagement is negatively related to job dissatisfaction.

The mediating role of work engagement

According to Baumeister and Leary (1995), the unmet social needs of individuals threaten their sense of personal significance and deteriorate their well-being. Such employees are reluctant to emotionally invest their selves in their work (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2011), making them ultimately dissatisfied with their job. We expect that work engagement will mediate the relationship between workplace loneliness and job dissatisfaction because employees want to develop an emotional attachment to and engage their selves with their work through feelings of warmth, belongingness (Meyer et al., 1997), and relatedness (Ryan and Deci, 2000), and they report negative attitudes when such positive experiences do not occur at the workplace (Saks, 2006).

The mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between workplace loneliness and job dissatisfaction is more evident when we view it from the perspective of Kahn’s (1990) theory of employee engagement who argued that the social relations at the workplace determine how safe (or unsafe) employees psychologically feel while engaging in their work roles. Thus, as a result of loneliness, employees’ affiliation needs remain unmet and they are likely to feel psychologically unsafe to express and employ their authentic selves fully at work, leading to their reduced engagement in work roles (Kahn, 1990; May et al., 2004; Rich et al., 2010). Based on the social and emotional needs approach, the typology of loneliness by Weiss (1987), explains that when individuals value a network of relationships where they can integrate and share an interest with others and when they feel valued in their work environment, they tend to fully engage themselves at their workplace (Crawford et al., 2010). Prior researchers (Saks, 2006; Moura et al., 2014; Gong et al., 2020), found that work engagement was related to job satisfaction because when employees experienced their work engagement as fulfilling and positive, they were more likely to report positive attitudes toward their jobs and organizations. Because loneliness erodes the positive and fulfilling experience of work engagement, employees are likely to report dissatisfaction with their jobs. We thus propose that:

Hypothesis 3: Work engagement mediates the positive relationship between workplace loneliness and job dissatisfaction.

The moderating role of need to belong

We have argued above that workplace loneliness reduces work engagement that in turn causes job dissatisfaction among lonely employees. This argument implies that these harmful effects will similarly exist for all lonely individuals. However, we believe that not all individuals are equally harmed by their loneliness because people differ in responding to their social pain of loneliness as a function of their unique individual differences, such as the need to belong. Researchers view the need to belong as a fundamental human motivation (Baumeister and Leary, 1995) and failure to sufficiently fulfill this need amplifies feelings of isolation and loneliness (Mellor et al., 2008). However, we believe that people differ in the degree of this need and the effect of loneliness on their work engagement will depend on whether they have a high or low need to belong.

Earlier studies have linked the need to belong and loneliness with social and psychological well-being (Zumaeta, 2019; Oyanedel and Paez, 2021). Satisfying the need for belongingness is viewed as an antecedent to healthy social ties and a buffer against perceived isolation (Mellor et al., 2008). Lonely employees assume that their colleagues and organization are unable to fulfill their affective needs which makes them reluctant to invest their selves emotionally at work (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2011). Such perceptions influence one’s performance, as individuals with satisfied affective needs work harder (Hackett et al., 1994), while loneliness triggers work withdrawal (Ozcelik and Barsade, 2011; Yilmaz, 2011).

In their social reconnection theory, Maner et al. (2007) note that social exclusion stimulates a desire to reconnect with others because of the need to belong which is a fundamental human motivation behind forming interpersonal relationships. These authors acknowledged and found support that the social exclusion–outcome relation is constrained by various boundary conditions, such as fear of negative evaluation and anticipated interaction with the new partner. Building on Maner et al. (2007), social reconnection argument in the context of work engagement, we contend that not all individuals experience decline in their work engagement due to having a deficiency in their social relationships. The detrimental effect of loneliness on work engagement is less salient for individuals who are high on their need to belong because they exercise alternative strategies to stimulate their pro-social behaviors to build and revive relationships with colleagues and their need to belong pushes them to stay engaged as a means of inclusion in the social interaction process through high performance (Baumeister and Leary, 1995; Maner et al., 2007; Gentina et al., 2018). In contrast, individuals with less need to belong are more likely to detach from their work and will have lesser work engagement. Based on this rationale, we propose that:

Hypothesis 4: Need to belong moderates the negative relationship between workplace loneliness and work engagement such that the relationship is weaker when the need to belong is higher than when it is lower.

Method

Sample and procedure

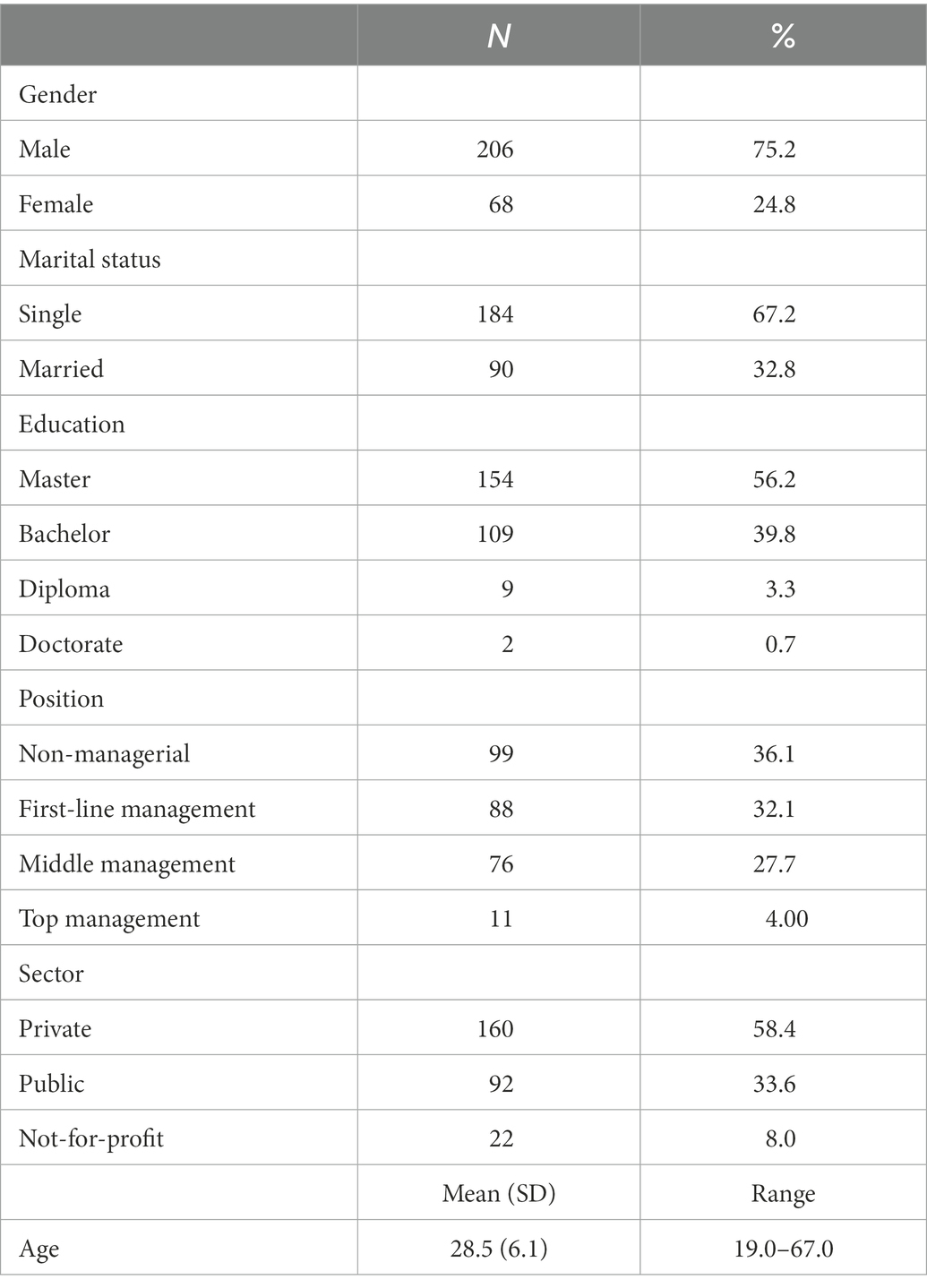

This study was carried out on a wide and diverse range of public, private, and not-for-profit organizations located in Lahore, Pakistan. Most of these companies had offices in a large government-owned software technology park. Among 90 companies that were contacted for this study, 78 agreed to participate. We sent e-mail invitations containing a link to our online survey to the contact persons of these companies who then forwarded the links to their employees. In total, 600 invitations were sent and 290 responses were received, yielding a response rate of 48%. After the initial screening, 274 responses were finalized for the main analysis. Table 1 shows that a majority of the respondents were male (75%), single (67%), had earned master’s degrees (56%) and worked in managerial positions (64%). Most of our respondents were employed in private sector organizations (58%) and an average respondent was 28.5 years (SD = 6.1) old.

Measures

Using self-reported items, respondents indicated the extent of their agreement with each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) for the scales of workplace loneliness, job dissatisfaction, and need to belong. However, for assessing work engagement, a six-point scale was used that ranged from almost never (1) to always (6).

Workplace loneliness. A 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale developed by Russell et al. (1980), was used. A sample item is “I lack companionship at my work.” The Alpha reliability of this scale was 0.90.

Job dissatisfaction. We measured job dissatisfaction with a three-item scale from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Seashore et al., 1982). Following (Zhou and George, 2001), we reverse-coded the items such that higher scores indicated greater job dissatisfaction. A sample item is “In general, I do not like my job.” The Alpha reliability of the scale was 0.77.

Need to belong. We used a 10-item scale of Leary et al. (2013), to measure the need to belong. Three reverse-scored items showed poor reliability and therefore were removed from the analysis. A sample item is “I want other people to accept me.” The Alpha reliability of the scale was 0.76.

Work engagement. We assessed work engagement using a three-item ultra-short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-3) developed by Schaufeli et al. (2019). These items are “At my work, I feel bursting with energy,” “I am enthusiastic about my job,” and “I am immersed in my work.” The Alpha reliability of this scale was 0.71.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

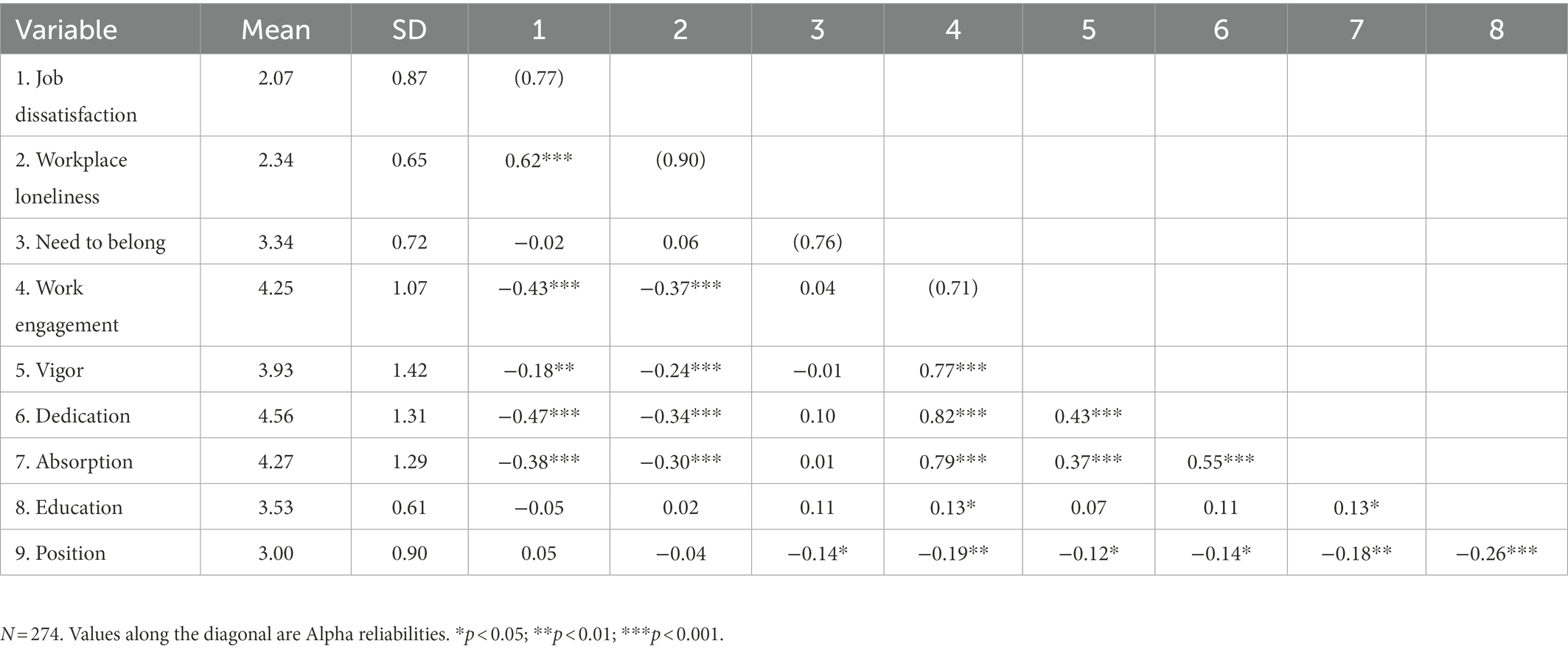

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables. Workplace loneliness significantly correlated to work engagement (r = −0.37, p < 0.001) and job dissatisfaction (r = 0.62, p < 0.001). Work engagement significantly correlated to job dissatisfaction (r = −0.43, p < 0.001). Need to belong, however, showed a non-significant correlation with workplace loneliness, work engagement, and job dissatisfaction. Among the demographic variables, only education and position showed significant correlations with some of our study variables, therefore, their effects were controlled during the main analyses. Furthermore, results of the independent sample t-test showed that the perceptions of male and female participants about loneliness, belongingness, engagement, and dissatisfaction were not statistically different from each other.

Common method bias test

We performed Harman’s single-factor test Podsakoff et al. (2003), to assess the presence of common method bias. All items of the four constructs were forced to load on a single un-rotated factor that extracted only 26% of the variance, indicating that much of the variance was not captured by this single factor. This showed that the common method bias did not influence our findings.

Confirmatory factor analysis

To reduce the complexity of the measurement model, we maintained a favorable parameter-to-sample size ratio and developed a just-identified measurement model using the item parceling method as suggested by methodologists (Landis et al., 2000; Bandalos, 2002; Little et al., 2013). We parceled items of workplace loneliness and need-to-belong scales into three by averaging the items having the highest and lowest factor loadings and repeated this process until we created three item parcels for both these constructs. The CFA results showed that the measurement model achieved a good model fit (χ2(48) = 94.8, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.05; TLI = 0.95; CFI = 0.97). Further, factor loadings of all indicators on their respective constructs were above the conservative cutoff value of 0.50 (workplace loneliness = 0.84–0.90; need to belong = 0.66–0.73; work engagement = 0.52–0.82; job dissatisfaction = 0.60–0.84). Furthermore, the alpha reliabilities (0.71–0.90) and construct reliabilities (0.72–0.90) were above 0.70. These results provided evidence that the measurement model achieved the convergent validity.

Table 3 presents the discriminant validity evidence. The proposed four-factor measurement model showed best model fit [χ2(48) = 94.8, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.05; TLI = 0.95; CFI = 0.97] as compared to all other nested models where relationships were constrained. As compared to all other models, the single factor model (χ2(58) = 856.3, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.23; SRMR = 0.33; TLI = 0.32; CFI = 0.40) showed the poorest model fit. These results demonstrated that the hypothesized four-factor model achieved discriminant validity.

Results of hypotheses testing

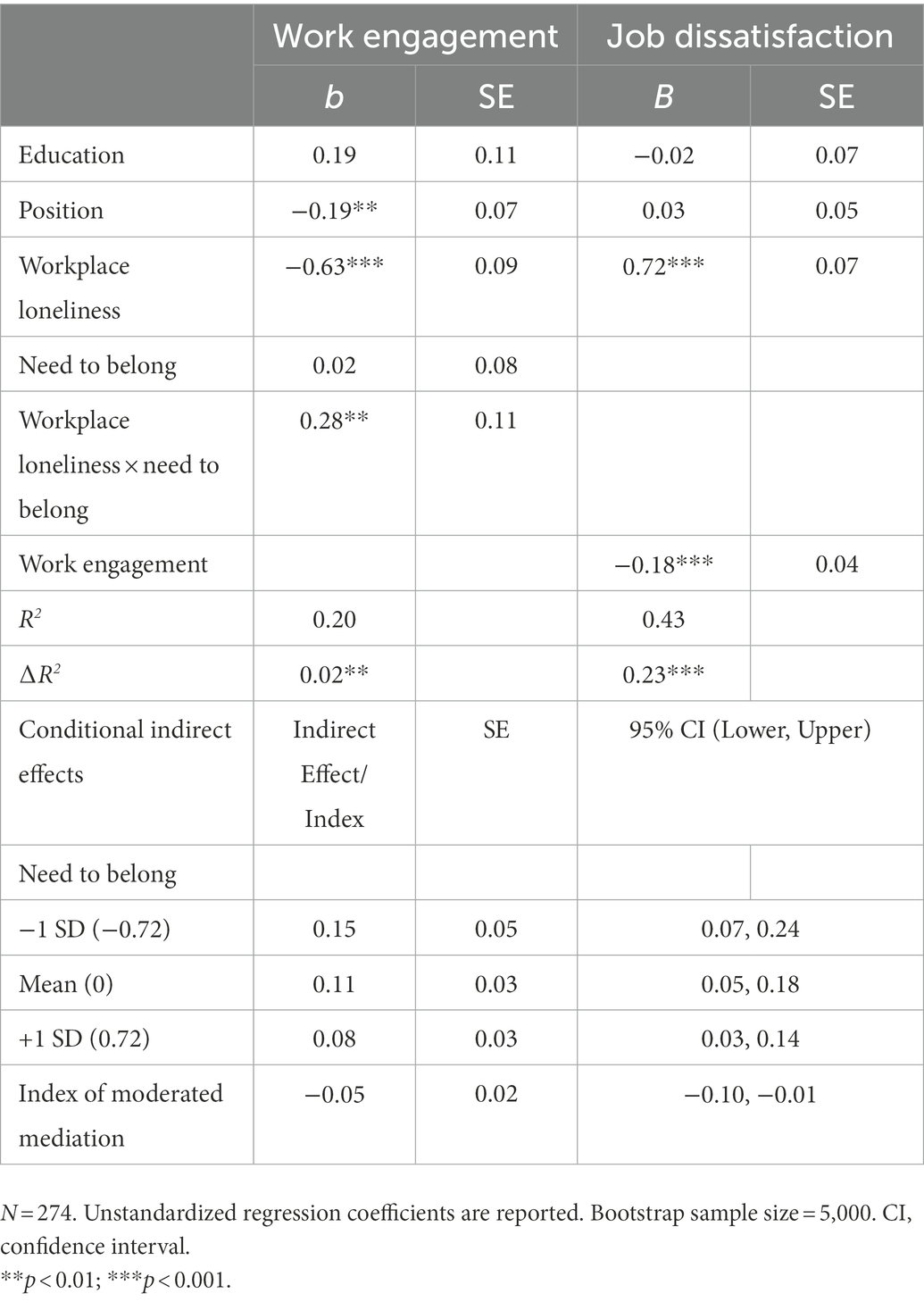

We tested our moderated mediation model using Model 7 of the Process procedure for SPSS (Hayes, 2013) controlling for education and position. Results showed that workplace loneliness had a significant negative effect on work engagement (b = −0.63, p < 0.001), lending support to Hypothesis 1. Work engagement had a significant negative effect on job dissatisfaction (b = −0.18, p < 0.001), providing support to Hypothesis 2. The direct effect of workplace loneliness on job dissatisfaction was significant (b = 0.72, p < 0.001), showing the possibility of the partial mediating effect of work engagement in the relationship between workplace loneliness and job dissatisfaction. We used the bias-corrected bootstrapping method by generating 5,000 bootstrap samples for a 95% level of confidence for the confidence intervals to test the significance of the proposed mediation. Results showed that the mediation effect of work engagement was significant (effect size = 0.11, 95% CI [0.05, 0.18]) because the confidence intervals did not include the value of zero (Hayes, 2013). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

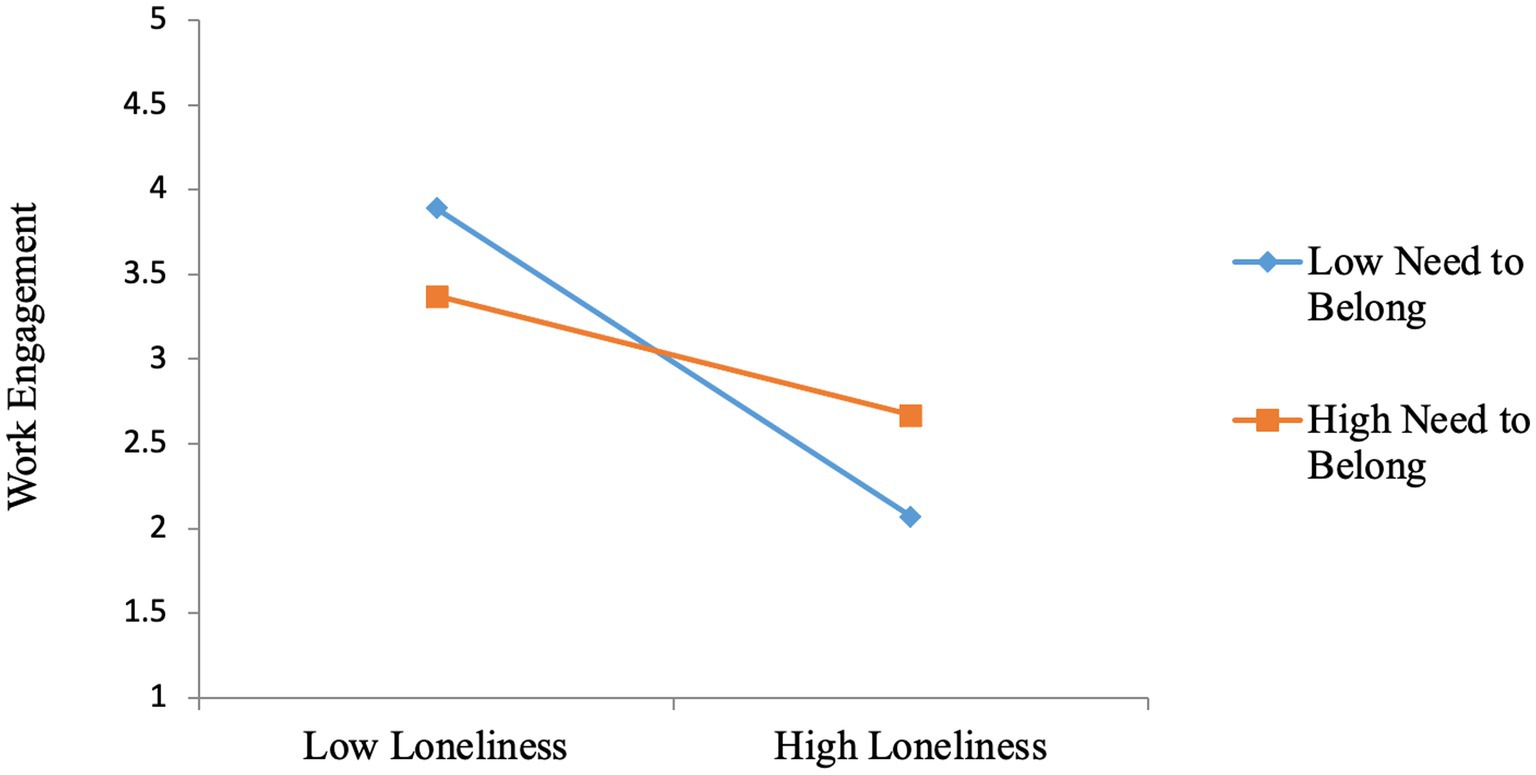

Next, the results showed a significant combined effect of workplace loneliness and the need to belong on work engagement (b = 0.28, p < 0.01). A slope test was performed to verify the nature of this interaction. As shown in Figure 2, individuals who had a higher need to belong continued to demonstrate high work engagement despite their loneliness. This showed that a higher need to belong weakened the deleterious effect of workplace loneliness on work engagement among these individuals. Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Finally, we tested the conditional indirect effect of workplace loneliness on job dissatisfaction via work engagement while taking into account the moderating effect of the need to belong. Table 4 shows that the effect of workplace loneliness on job dissatisfaction via work engagement was weaker (effect size = 0.08, 95% CI [0.03, 0.14]) when the need to belong was higher than when it was lower (effect size = 0.15, 95% CI [0.07, 0.24]). The index of moderated mediation (effect size = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.10, −0.01]) revealed that the conditional indirect effect of workplace loneliness on job dissatisfaction was statistically significant. Thus, the proposed moderated mediation model received significant statistical support.

Discussion

This study aimed to address the effect of workplace loneliness on job dissatisfaction via work engagement along with the moderating role of the need to belong. We tested our moderated mediation model among 274 Pakistani employees who worked in diverse organizations. The findings of this study confirm that workplace loneliness increases job dissatisfaction among lonely employees by decreasing their engagement with work and that this indirect effect of workplace loneliness is weaker when lonely employees have a higher need to belong.

Our findings are in line with previous research showing that a discrepancy between the desired and existing levels of interpersonal relationships makes employees feel lonely and distanced at their workplaces (Wright et al., 2006; Hawkley et al., 2010; Ozcelik and Barsade, 2018). Employees’ desire to have fulfilling relationships at work makes them feel valued, significant, and satisfied with their jobs (Tabancali, 2016). However, loneliness snaps their self-confidence and cultivates stress (Hawkley et al., 2010), generating feelings of doubt and frustration. Because of being unable to satisfy their social need for belongingness at work, lonely employees become demotivated, disengaged, and dissatisfied with their work (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008).

Work engagement is associated with desirable employee attitudes and behaviors (Saks, 2006), as they can satisfy their needs through effective engagement at work (Mauno et al., 2007). Our results support the evidence that for disengaged employees their work routine becomes a mere repetition of work-related behaviors that are devoid of social or emotional connectivity toward work (Hollis et al., 2015). Such employees remain physically present yet psychologically absent and live in a withdrawal state of dissatisfaction toward their work (Carnahan, 2013).

The findings of the present study also revealed that work engagement mediates the relationship between workplace loneliness and job dissatisfaction. These findings indicate that loneliness alienates and isolates employees from their environment, making them personally frustrated and less approachable toward colleagues. Such a work climate is deficient in opportunities for employees to connect and integrate at the workplace, reducing their engagement and commitment toward work (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004; Bakker and Bal, 2010). Employees who are unable to interpersonally integrate at work perceive their selves unnoticed and invisible to others, leading them to demonstrate poor performance, low productivity, and job dissatisfaction (Akçit and Barutçu, 2017).

Furthermore, this study has found that the unmet need for belongingness poses a threat to one’s well-being, whereas the satisfied need for belongingness acts as a buffer against the deleterious effects of workplace loneliness (Mellor et al., 2008). Our findings suggest that employees with a higher need to belong are less affected by their loneliness as compared to the employees with a lower need to belong because they do not try to reconnect with others and rather prefer to detach from their group and work as a means of reaction to their loneliness. Our findings are consistent with the previous research, suggesting that individuals with satisfied and high affective needs work harder (Hackett et al., 1994; Mellor et al., 2008), while loneliness triggers withdrawal and dissatisfaction (Tabancali, 2016; Wright and Silard, 2021). In sum, this study was directed to study relatively less explored phenomena of workplace loneliness and its effects on employees’ work-related well-being.

Contribution to theory and practice

This study contributes to knowledge in several ways. It enhances our understanding of employee loneliness in the domain of work in particular, and reveals it as a barrier for inclusive organizations in general. The role of social needs in the workplace is commonly ignored despite having clear evidence pointing toward its impact on employees’ work outcomes (Zhou and Wu, 2018). The findings of our study augment the existing workplace loneliness literature by exploring the previously unexplored moderating role of the need to belong and mediating role of work engagement in the organizational context. We respond to the calls for research (Anand and Mishra, 2021; Andel et al., 2021; Wright and Silard, 2021), by examining work engagement as a mediator and the need to belong as a moderator in the work loneliness–job dissatisfaction relationship, thus extending the nomological network of workplace loneliness. Furthermore, this study provides evidence for the prevalence of workplace loneliness in the collectivist culture of Pakistan where social bonds are expected to be stronger as compared to the individualistic cultures. This implies that loneliness is a universal social issue having serious consequences for the well-being of its victims.

This study has practical implications for managers to consider. Rapid industrialization and globalization have made organizational cultures overwhelmingly competitive and demanding. The competitive work environments can generate performance in the short term but ignoring workplace loneliness can result in reduced employee well-being and ultimately poor job performance in the long run. Thus, managers seeking to make their organizations effective and inclusive should try to enhance friendly social interactions among colleagues over and above their individual differences. They should align and make use of the talents of their diverse workforce through their broader participation and the systems are driven by equity. Further, to tone down the negative effects of workplace loneliness, HR may consider the need to belong as an important factor in the selection process specifically for desk jobs that require less social interaction. HR should create socialization activities for such employees and provide social support to make them feel socially connected. Moreover, organizations need to pay special attention to employees having a low need to belong and be responsive to workplace loneliness by being more inclusive in their relationship with their employees. Further, both HR and organizations may focus on improving the quality of working conditions which may help to reduce employees’ loneliness.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This study has both strengths and limitations. The occupational diversity of our sample enhances and extends the generalizability of our findings to the broader population of Pakistani employees. In addition, this study produces evidence from a country of 200 million, which has a collectivist culture and is an underrepresented region in management research. A major limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design which decreases our absolute confidence in the causal direction of our constructs although our logical argument supports the causal direction. We suggest that future research should employ time-lagged, longitudinal, or field experiment designs to check if they predict different findings. Furthermore, as loneliness indicates the misfit between one’s existing and desired social needs, it would be interesting to view this concept through the lens of the person-environment fit theory (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; Follmer et al., 2018), to explore more mediating and moderating conditions of the workplace loneliness–outcomes relations.

Conclusion

Modern technology has made possible instant connections and interpersonal communication between hundreds of employees, yet workplace loneliness is on the rise (Mell et al., 2018). Contemporary organizations are seeking to become inclusive where individuals can comfortably use their full potential toward achieving goals and can enhance their well-being. However, workplace loneliness impedes this path and calls for sound management interventions to make organizations more inclusive.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Research Ethics Committee of GIFT University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AB: designed the study, reviewed literature, collected data, and prepared the first draft. SN: reviewed literature and actively participated in writing and finalizing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akçit, V., and Barutçu, E. (2017). The relationship between performance and loneliness at workplace: a study on academicians. Eur. Sci. J., 235–243.

Albrecht, S. L., Bakker, A. B., Gruman, J. A., Macey, W. H., and Saks, A. M. (2015). Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage: an integrated approach. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2, 7–35. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-08-2014-0042

Anand, P., and Mishra, S. K. (2021). Linking core self-evaluation and emotional exhaustion with workplace loneliness: does high LMX make the consequence worse? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 32, 2124–2149. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1570308

Andel, S. A., Shen, W., and Arvan, M. L. (2021). Depending on your own kindness: the moderating role of self-compassion on the within-person consequences of work loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 26, 276–290. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000271

Azambuja, R., and Islam, G. (2019). Working at the boundaries: middle managerial work as a source of emancipation and alienation. Hum. Relat. 72, 534–564. doi: 10.1177/0018726718785669

Bakker, A. B., and Bal, M. P. (2010). Weekly work engagement and performance: a study among starting teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 83, 189–206. doi: 10.1348/096317909X402596

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. international 13, 209–223. doi: 10.1108/13620430810870476

Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., and Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 274–284. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274

Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 9, 78–102. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0901_5

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Carnahan, D. (2013). A Study of employee engagement, job satisfaction and employee retention of Michigan CRNAs. Michigan: University of Michigan-Flint.

Chen, J.-Q., Hou, Z.-J., Li, X., Lovelace, K. J., Liu, Y.-L., and Wang, Z.-L. (2016). The role of career growth in Chinese new employee’s turnover process. J. Career Dev. 43, 11–25. doi: 10.1177/0894845315571412

Chirico, F., Crescenzo, P., Nowrouzi-Kia, B., Tarchi, L., Batra, K., Ferrari, G., et al. (2022). Prevalence and predictors of burnout syndrome among schoolteachers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a cross-sectional study. J. Health Soc. Sci. 7, 195–211. doi: 10.19204/2022/PRVL6

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., and Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: a quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 64, 89–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., and Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: a theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 95, 834–848. doi: 10.1037/a0019364

De Castella, K., and Byrne, D. (2015). My intelligence may be more malleable than yours: personal implicit theories and links with achievement, motivation and student disengagement. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 30, 245–267. doi: 10.1007/s10212-015-0244-y

De Lange, A. H., De Witte, H., and Notelaers, G. (2008). Should I stay or should I go? Examining longitudinal relations among job resources and work engagement for stayers versus movers. Work Stress 22, 201–223. doi: 10.1080/02678370802390132

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Edmondson, A. C., and Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. Organ. Behav. 1, 23–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

Fleming, J. H., Coffman, C., and Harter, J. K. (2005). Manage your human sigma. Harv. Bus. Rev. 83:106–192.

Follmer, E. H., Talbot, D. L., Kristof-Brown, A. L., Astrove, S. L., and Billsberry, J. (2018). Resolution, relief, and resignation: a qualitative study of responses to misfit at work. Acad. Manag. J. 61, 440–465. doi: 10.5465/amj.2014.0566

Gabr, H. M., Soliman, S. S., Allam, H. K., and Raouf, S. Y. A. (2021). Effects of remote virtual work environment during COVID-19 pandemic on technostress among Menoufia university staff, Egypt: a cross-sectional study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 53746–53753. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14588-w

Gentina, E., Shrum, L., and Lowrey, T. M. (2018). Coping with loneliness through materialism: strategies matter for adolescent development of unethical behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 152, 103–122. doi: 10.1007/s10551-016-3329-x

Gong, Y., Wu, Y., Huang, P., Yan, X., and Luo, Z. (2020). Psychological empowerment and work engagement as mediating roles between trait emotional intelligence and job satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 11:232. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00232

Hackett, R. D., Bycio, P., and Hausdorf, P. A. (1994). Further assessments of Meyer and Allen's (1991) three-component model of organizational commitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 79, 15–23. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.79.1.15

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 43, 495–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Halbesleben, J. R. (2010). “A meta-analysis of work engagement: relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences,” in Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. Vol. 8. eds. A. B. Bakker and M. P. Leiter (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 102–117.

Hawkley, L. C., Thisted, R. A., Masi, C. M., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness predicts increased blood pressure: 5-year cross-lagged analyses in middle-aged and older adults. Psychol. Aging 25, 132–141. doi: 10.1037/a0017805

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press

Hollis, L. P. (2015). Bully university? The cost of workplace bullying and employee disengagement in American higher education. SAGE Open 5:215824401558999. doi: 10.1177/2158244015589997

Hollis, C., Morriss, R., Martin, J., Amani, S., Cotton, R., Denis, M., et al. (2015). Technological innovations in mental healthcare: harnessing the digital revolution. Br. J. Psychiatry 206, 263–265. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.142612

Hornstein, E. A., and Eisenberger, N. I. (2022). Exploring the effect of loneliness on fear: implications for the effect of COVID-19-induced social disconnection on anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 153:104101. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2022.104101

Hu, Q., Schaufeli, W. B., and Taris, T. W. (2011). The job demands–resources model: an analysis of additive and joint effects of demands and resources. J. Vocat. Behav. 79, 181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.009

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.2307/256287

Kalil, A., Ziol-Guest, K. M., Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Job insecurity and change over time in health among older men and women. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 65B, 81–90. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp100

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., and Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences OF INDIVIDUALS'FIT at work: a meta-analysis OF person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 58, 281–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

Lam, L. W., and Lau, D. C. (2012). Feeling lonely at work: investigating the consequences of unsatisfactory workplace relationships. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 23, 4265–4282. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.665070

Landis, R. S., Beal, D. J., and Tesluk, P. E. (2000). A comparison of approaches to forming composite measures in structural equation models. Organ. Res. Methods 3, 186–207. doi: 10.1177/109442810032003

Leary, M. R., Kelly, K. M., Cottrell, C. A., and Schreindorfer, L. S. (2013). Construct validity of the need to belong scale: mapping the nomological network. J. Pers. Assess. 95, 610–624. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.819511

Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., and Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol. Methods 18, 285–300. doi: 10.1037/a0033266

Llorens, S., Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W., and Salanova, M. (2006). Testing the robustness of the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 13, 378–391. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.13.3.378

Maner, J. K., DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., and Schaller, M. (2007). Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the "porcupine problem". J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 92, 42–55. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.42

Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., and Ruokolainen, M. (2007). Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: a longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 70, 149–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2006.09.002

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., and Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 77, 11–37. doi: 10.1348/096317904322915892

McKee, A. (2017). How to be Happy at Work: The Power of Purpose, Hope, and Friendship. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 47–52.

Mell, J., Quintane, E., Hirst, G., and Carnegie, A. B. (2018). The influence of manager Machiavellianism on supervisor boundary spanning and employee creativity. Academy of Management Proceedings. 2018:10521. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2018.10521abstract

Mellor, D., Stokes, M., Firth, L., Hayashi, Y., and Cummins, R. (2008). Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 45, 213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.020

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., and Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the Workplace. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Moura, D., Orgambidez, A., and Gonçalves, G. (2014). “Role stress and work engagement as antecedents of job satisfaction,” in Stress and Anxiety: Applications to Social and Environmental Threats, Psychological Well-Being, Occupational Challenges, and Developmental Psychology. (Berlin: Logos Verlag).

Nishimura, Y., Miyoshi, T., Hagiya, H., Kosaki, Y., and Otsuka, F. (2021). Burnout of healthcare workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a Japanese cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2434. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052434

Omar, M. K., Aluwi, A. H., Hussein, N., Mohd, I. H., and Rusdi, S. D. (2020). Workload, job control, work relationship, and work-related stress among employees in Sungai Buloh, Malaysia. Insight J. 6, 168–176.

Oyanedel, J. C., and Paez, D. (2021). Editorial: social belongingness and well-being: international perspectives. Front. Psychol. 12:735507. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.735507

Ozcelik, H., and Barsade, S. (2011). Work loneliness and employee performance. Academy of management proceedings 2011, 1–6. doi: 10.5465/ambpp.2011.65869714

Ozcelik, H., and Barsade, S. G. (2018). No employee an island: workplace loneliness and job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 61, 2343–2366. doi: 10.5465/amj.2015.1066

Peng, J., Chen, Y., Xia, Y., and Ran, Y. (2017). Workplace loneliness, leader-member exchange and creativity: the cross-level moderating role of leader compassion. Personal. Individ. Differ. 104, 510–515. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.020

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rastogi, A., Pati, S. P., Krishnan, T., and Krishnan, S. (2018). Causes, contingencies, and consequences of disengagement at work: an integrative literature review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 17, 62–94. doi: 10.1177/1534484317754160

Rayton, B., Dodge, T., and D'Analeze, G. (2012). The evidence: Employee engagement task force “nailing the evidence” workgroup. Engage for Success. 1–33.

Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., and Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 53, 617–635. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.51468988

Russell, D., Cutrona, C. E., Rose, J., and Yurko, K. (1984). Social and emotional loneliness: an examination of Weiss's typology of loneliness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46, 1313–1321. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.46.6.1313

Russell, D., Peplau, A., and Cutrano, C. (1980). Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence for the UCLA loneliness scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 39, 472–480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 21, 600–619. doi: 10.1108/02683940610690169

Schaufeli, W. B., and Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: a multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 25, 293–315. doi: 10.1002/job.248

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 3, 71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., Hakanen, J., Salanova, M., and De Witte, H. (2019). An ultra-short measure for work engagement. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 35, 577–591. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000430

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., and Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Appl. Psychol. 57, 173–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00285.x

Schaufeli, W., and Van Rhenen, W. (2006). Over de rol van positieve en negatieve emoties bij het welbevinden van managers: Een studie met de job-related affective well-being scale (JAWS)[about the role of positive and negative emotions in managers’ well-being: a study using the job-related affective well-being scale (JAWS)]. Gedrag Organisatie 19, 223–244. doi: 10.5117/2006.019.004.002

Seashore, S. E., Lawler, E. E., Mirvis, P., and Cammann, C. (1982). Observing and Measuring Organizational Change: A Guide to Field Practice. New York: Wiley.

Tabancali, E. (2016). The relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and loneliness at the workplace. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 16, 1–30. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2016.66.15

Weiss, R. S. (1987). Reflections on the present state of loneliness research. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2, 1–16.

Wright, S. L., Burt, C. D., and Strongman, K. T. (2006). Loneliness in the workplace: Construct definition and scale development. New Zealand J. Psychol. 35, 59–68.

Wright, S. (2012). Is it lonely at the top? An empirical study of managers’ and nonmanagers’ loneliness in organizations. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 146, 47–60. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.585187

Wright, S., and Silard, A. (2021). Unravelling the antecedents of loneliness in the workplace. Hum. Relat. 74, 1060–1081. doi: 10.1177/0018726720906013

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 14, 121–141. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121

Yilmaz, E. (2011). An investigation of teachers loneliness in the workplace in terms of human values they possess. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 5, 5070–5075. doi: 10.5897/AJBM10.303

Zhou, J., and George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: encouraging the expression of voice. Acad. Manag. J. 44, 682–696. doi: 10.2307/3069410

Zhou, F., and Wu, Y. J. (2018). How humble leadership fosters employee innovation behavior: a two-way perspective on the leader-employee interaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 39, 375–387. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-07-2017-0181

Keywords: workplace loneliness, job satisfaction, need to belong, work engagement, well-being, moderated-mediation

Citation: Basit AA and Nauman S (2023) How workplace loneliness harms employee well-being: A moderated mediational model. Front. Psychol. 13:1086346. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1086346

Edited by:

Thurasamy Ramayah, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), MalaysiaReviewed by:

Zilong Cui, Jilin University of Finance and Economics, ChinaPietro Crescenzo, Italian Red Cross, Volunteer Military Corps, Italy

Nurka Pranjic, University of Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Copyright © 2023 Basit and Nauman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ameer A. Basit, ✉ YW1lZXJiYXNpdEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Ameer A. Basit

Ameer A. Basit Shazia Nauman

Shazia Nauman