94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 27 January 2023

Sec. Personality and Social Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1084731

This article is part of the Research TopicCollective Behavior and Social Movements: Socio-psychological PerspectivesView all 17 articles

Bertha Estela-Delgado1

Bertha Estela-Delgado1 Gilmer Montenegro1

Gilmer Montenegro1 Jimmy Paan1

Jimmy Paan1 Wilter C. Morales-García2,3*

Wilter C. Morales-García2,3* Ronald Castillo-Blanco4

Ronald Castillo-Blanco4 Liset Sairitupa-Sanchez5

Liset Sairitupa-Sanchez5 Jacksaint Saintila6*

Jacksaint Saintila6*Crises negatively affect the economy of a country, increasing financial risk, as they affect work activities and the well-being of the population. This study aimed to examine the mediating role of financial well-being in the relationship between personal well-being and financial threats. A predictive cross-sectional study was conducted. The variables analyzed were personal well-being, financial threats, and financial well-being. A total of 416 Peruvian adults from the three regions of Peru participated. The mean age was M = 35.36, SD = 8.84, with a range of 19–62 years. To represent the statistical mediation model, a structural equation model (SEM) was used. The analysis showed that the variables were significantly related (p < 0.001). The theoretical model indicated a perfect mediation, also obtaining a good fit, χ2(168) = 394.3, CFI = 0.931, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.062. The study showed that personal well-being serves as a basis for promoting financial well-being and this contributes to the reduction of financial threats.

Health crises such as COVID-19 have led to unstable labor situations and increased labor concerns, negatively affecting the global and Peruvian economy (Barraza, 2020; Wilson et al., 2020; Durst et al., 2021). Financial risks have had an impact on labor and business activities, causing negative consequences due to temporary layoffs, business closures, and job insecurity (Alcover et al., 2020). The increase in unemployment was more constant along with the financial difficulties of micro and small businesses. Families were affected by economic uncertainty, expressing greater pessimism about the economic situation, and there was less financial well-being (Barrafrem et al., 2020). Informal workers are unable to earn income due to public health restrictions and depending on government assistance and food donations, these financial threats affect their financial well-being (Salameh et al., 2020; Botha et al., 2021). However, the more experience one has with economic hardship, the more financial threats to the population increase (Fiksenbaum et al., 2017b). Social scientists indicate that personal finances are related to well-being; therefore, financial crises predict poor physical and psychological health outcomes for the population (Richardson et al., 2013).

Financial well-being is considered as an objective condition when considering material economic resources, and it is also a subjective experience when considering and evaluating one’s own economic condition (Sorgente and Lanz, 2017; Kaur et al., 2021). Not all people have the same perception of their financial situation. Some people with few resources are satisfied with their lives, while others, full of opportunity and wealth, struggle because they don’t have enough finances (Grezo and Sarmany-Schuller, 2015). Financial well-being has been an important variable during the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the effect on occupational, economic, and health vulnerability during the quarantine period (Chori et al., 2021). Making good decisions has an impact on financial well-being, but you need to plan for the long term, saving, in order to establish short-term security (Fan, 2021). People often find it difficult to administer or manage their finances, which leads to behaviors that have a negative effect on their savings and increase their financial threats, as they become vulnerable to financial crises (Braunstein and Welch, 2002; Ullah and Yusheng, 2020). Studies show that adults lack financial knowledge and skills, as they are faced with many financial areas such as spending, savings, housing, retirement, and credit cards that could ensure their financial well-being, yet they possess low financial education that causes debts, savings, retirement plans to affect their future financial well-being (Rutherford and Fox, 2010; Sinha et al., 2018). In fact, being financially educated may help acquire attitudinal and behavioral roles related to financial well-being and alleviate or reduce the anxiety or stress that accompanies crises (Shim et al., 2009).

Personal well-being allows when the person faces challenges or threats, to go through a process of adaptation in order to balance demands such as psychosocial health and to have some coping strategies. This allows the person to emerge with adaptive resources for future challenges (Gonzalez et al., 2022). Whereas, constraints such as concerns about money or financial resources affect personal well-being (Rea et al., 2018). During the pandemic, parents have promoted well-being, health, and ability to cope with internal and external factors (Russell et al., 2020). Therefore, decreasing the factors that affect financial states allows for better financial well-being and improved personal well-being. Decreased personal well-being influences financial well-being due to crises and can have lasting effects on physical health, increased heart disease, lower job performance, and shorter life expectancy (Ferreira et al., 2021).

Financial problems contribute to an increase in negative psychosocial outcomes, such as psychological distress, depression, suicidal intent, and dissatisfaction with life, among others (Mamun et al., 2020). The financial threat is the way in which the person evaluates stressful situations and usually produces fear, worry, or uncertainty of financial stability and security, because as there is a financial crisis, financial situations also deteriorate (Marjanovic et al., 2015). It is important to make a primary assessment to establish the harm that some stressors may cause in the future. Therefore, the higher the estimation of harm, the higher the perception of the different stressors as threatening (Fiksenbaum et al., 2017b). The analysis of threat levels is followed by an evaluation of the potential aspects to address financial threats. Financial threats increase in times of crisis or financial deterioration (Folkman, 2013; Mamun et al., 2020).

Financial well-being is a person’s objective and subjective assessment of his or her current situation. A person’s dynamic assessment of his or her own well-being is determined by various personal and contextual factors that are changeable (Brüggen et al., 2017). Financial literacy has become an essential skill due to unstable global markets (Philippas and Avdoulas, 2019). Several studies have found that the influence of personal factors is important in financial well-being, since financial well-being allows control over finances and is able to absorb financial threats, the freedom to make decisions that promote the well-being of the individual (Zhang and Cao, 2010; Ponchio et al., 2019). Financial well-being results from meeting financial commitments, financial resilience for future events. In addition, behavioral factors such as spending restraint, active savings, and no borrowing for daily expenses, allow for greater financial well-being (Carton et al., 2022). Stress can lead to short-term credit decisions that can aggravate initial debt problems (Gathergood and Weber, 2014). Furthermore, the literature indicates that there is a detrimental relationship between financial hardship and mental health (Bialowolski et al., 2021). Thus, financial well-being can be a mediator between personal well-being and financial threats.

Subjective well-being is the cognitive appraisals of general satisfaction, emotional appraisals of happiness, and emotional balance (Diener et al., 1999; Diener and Oishi, 2009). Personal well-being has been evaluated in different ways such as life satisfaction, happiness, and general well-being, it also involves activities subject to finances, as there are a large number of factors that contribute to personal well-being. Personal well-being is a predictor of financial well-being (Gerrans et al., 2013). Models such as Joo (2008) indicate that financial well-being is a component of personal well-being. However, there is a causal link between financial well-being and personal well-being, since an increase in financial well-being is associated with an increase in personal well-being (Gerrans et al., 2013).

Financial threat refers to fearful-anxious uncertainty regarding current or future conditions. In the midst of economic crises, financial threat tends to increase more than normal. This to the likelihood of economic deterioration, high unemployment rates, and declining quality of life (Marjanovic et al., 2013; Fiksenbaum et al., 2017a). Likewise, Lazarus and Folkman (2013) indicate that threatening perceptions are not always based on reality, but more of a perceived danger of stress and focus on coping skills. In the face of this people whose financial well-being has been eroded their financial stability as a result of economic instability allows them to experience greater financial threat and leads to greater psychological distress. Likewise, people who experience greater financial threat are those who experience situations such as job loss, financial difficulties, loss of income, and stress (de Miquel et al., 2022; Figure 1).

Based on the above, it is proposed that financial well-being mediates the relationship between personal well-being and financial threats, considering the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Personal well-being will have an effect on financial threat.

Hypothesis 2: Financial well-being mediates the relationship between personal well-being and financial threat.

A cross-sectional and explanatory study was designed considering latent variables represented by a system of structural equations (Ato et al., 2013). The number of participants was determined using Soper software that considers the number of observed and latent variables for structural equation models (SEM), whereby the anticipated effect size (λ = 0.3), statistical power levels (1 – β = 0.95), and the desired probability (α = 0.05), indicated a number of 184 of participants (Soper, 2021). The final sample consisted of 416 Peruvian adults from the 3 regions of Peru (coast, highlands, and jungle) using a convenience sampling method, taking into account the absence of data and lack of response.

After approval by the ethics committee of the University (Cod: 2021- CE-EPG-000078), participants were invited to complete the questionnaire available from 21 November 2021, to 20 February 2022 via Google Forms, which allowed online sharing. Prior to data collection, the guidelines stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki and the norms of confidentiality were considered by informing participants about the nature of the project, followed by obtaining informed consent. The completeness of the questionnaires presented below was evaluated.

Measures of personal well-being, financial threat, and financial well-being adopted from existing research were considered and translated into Spanish according to established guidelines for the translation and cross-cultural validation of instruments (Tsang et al., 2017).

1. Initially, three PhDs with expertise in business administration and finance and accounting, fluent in English and Spanish, made a direct and independent translation of the three measures into Spanish (Peru)

2. Second, the first Spanish version was independently translated into English by two translators whose native language was English and who were fluent in Spanish

3. Third, based on both versions, the research team, together with the translators mentioned above, evaluated the translated versions and performed a comparative analysis with this existing version, considering some linguistic and cultural similarities. The items were evaluated by financial and management experts in the field who considered that the items were appropriate and that the instrument was relevant to the Peruvian population, so the initial version of the measures of personal well-being, financial threat, and financial well-being was developed

4. Fourth, a pilot test was conducted, in which the initial version was applied to 10 students to check the readability and comprehension of the items

5. In fifth place, the research group evaluated the pilot, test and no modifications were suggested, which made it possible to have the version of personal well-being, financial threat, and financial well-being (Annex 1). The instruments are described below.

Financial well-being was measured using the inventory that included six of the items from the Prawitz et al. (2012) measure of financial distress/financial well-being. Participants were asked to indicate their degree of financial stress on a scale of 1–10. For example, “on a scale of 1–10, where one is” overwhelmingly stressed “and ten is” no stress at all.” In this study, the model presented adequate reliability indices on the total scale (ordinal α = 092, ω = 0.89, H = 0.92), and the model presented adequate validity indices (χ2 = 85.732; df = 9; p = 0.000; CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.997, RMSEA = 0.073, SRMR = 0.028).

Personal well-being will be measured using the PWI-A (International Wellbeing Group, 2006), which contained 8 items and a general well-being question that was used by the International Wellbeing Group to validate the index. Participants indicated their degree of satisfaction in different areas of life: life as a whole, standard of living, health, life achievements, personal relationships, present security, feeling part of a community, future security, and spirituality or religion. For each item, participants were asked to indicate a value from 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied), with 5 being neutral. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.70 to 0.85. In this study, 6 items were considered (see Appendix 1), the model presented adequate reliability indices (ordinal α = 0.90, ω = 0.92, H = 0.93), and the model presented adequate validity indices (χ2 = 73.556; df = 9; p = 0.000; CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.066, SRMR = 0.021).

The five-element FTS was developed in accordance with existing threat measures and threat research (Marjanovic et al., 2013). The aim is to cover a wide range of the hypothetical financial threat construct with as few elements as possible. Its five items cover areas of uncertainty, risk, perceived threat (included to reinforce face validity), worry, and cognitive concern with current personal finances. The five items are supported along five-point scales, the endpoints of which change slightly to reflect the content of the item. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 was obtained. In this study, the model presented adequate reliability indices (ordinal α = 0.98, ω = 0.87 and H = 0.96), and the model presented adequate validity indices (χ2 = 14.689; df = 2; p = 0.000; CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.064, SRMR = 0.020).

The theoretical model under study was analyzed using structural equation modeling with the MLR estimator, which is appropriate for numerical variables and is robust to inferential normality deviations (Muthen and Muthen, 2017). The evaluation of the fit was performed with the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI values of >0.90 were used (Bentler, 1990), RMSEA <0.080 (MacCallum et al., 1996), and SRMR <0.080 (Browne and Cudeck, 1992). For the mediation analysis, the bootstrapping method was used with 5,000 iterations and a 95% confidence interval (Yzerbyt et al., 2018). Regarding reliability analysis, the internal consistency method was used with the alpha coefficient (α), ordinal α, and coefficient ω (McDonald, 1999; Hancock and Mueller, 2001; Pascual-Ferrá and Beatty, 2015) expecting magnitudes greater than 0.80 (Raykov and Hancock, 2005; Dominguez-Lara, 2016).

The structural equation modeling analysis was performed with the “R” software in version 4.0.5 and the “lavaan” library was used (Rosseel, 2012). The organization of the initial database and the first descriptive results were obtained with IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software.

The final sample was comprised 416 Peruvian adults. The mean age was M = 35.36 (SD = 8.84) ranging from 19 to 62 years. Among them (Table 1), it is shown that the majority were between 29 and 38 years old (42.3%), with an income level of 0 to 930 (33.7%), from the coastal region (76.0%), with a high school technical education (32.7%), self-employed (50.7%), with an average financial education (57.9), and savings (56.3).

The scores of the study variables were scaled between values between 0 and 30 in order to facilitate their reading. Table 2 shows the correlation matrix and the descriptive results, where the correlation results are between 0.24 and 0.50 in absolute value. In addition, this table also shows the internal consistencies that were found between the values of 0.87 and 0.94.

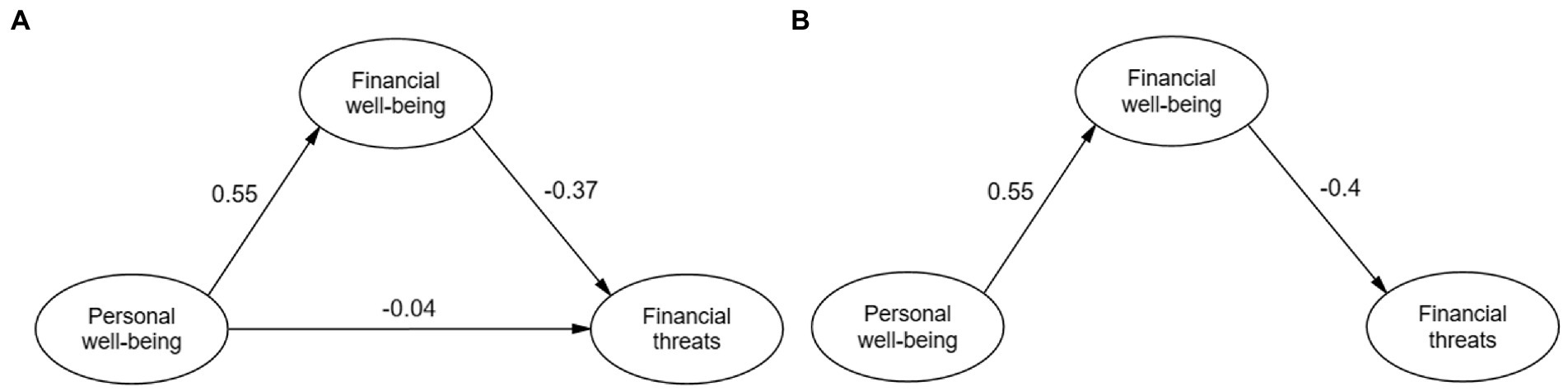

In the theoretical model analysis, an adequate fit was obtained, 2 (167) = 393.4, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.931, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.057, results that can be visualized in the left model in Figure 2 (model a). Given the close to null value of the effect of personal well-being on financial threats, and in consideration of the parsimony criteria of the model proposal, we chose to restrict this relationship to zero, also obtaining a good fit, 2 (168) = 394.3, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.931, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.062. This model is presented on the right side of the Figure 2 (model b).

Figure 2. Results of the structural model: (A) Including direct effect and (B) excluding direct effect.

For the mediation analysis, bootstrapping of 5,000 iterations was used. Then, with respect to H2, the mediating effect of financial well-being on the effect of Personal Well-Being on Financial Threats is confirmed, β = −0.22, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.12, −0.05].

The financial crises resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in considerable losses not only in the health aspect but also in the economy in Peru and worldwide. Peru had been suffering economic problems and these were aggravated by the various measures adopted by the government, where many companies had to close and there was a massive layoff of personnel, which increased unemployment (Barreto et al., 2021). Subsequently, due to the normalization of economic activities and the new measures taken by the government, the economy recovered after a downturn; however, the drop in formal employment and loss of income continue without a visible recovery (Barreto et al., 2021). The purpose of this study was to examine how personal well-being influences financial threats through financial well-being. The results supported that personal well-being was positively associated with financial well-being, which, in turn, was negatively associated with financial threats. The study contributes to a more complete understanding of the process of personal well-being through the underlying mechanism of how personal well-being affects financial threats during a crisis.

As expected, personal well-being was positively associated with financial well-being. The result was consistent with previous studies (Nanda and Banerjee, 2021), as they indicate a healthy balance between savings and expenses crucial to personal and financial well-being (Brüggen et al., 2017). So financial well-being allows for a state of overall happiness or satisfaction with financial situations, and encompasses greater security with income or savings and thus maintaining material security (Mahdzan et al., 2020). Thus, proper financial behavior and self-control allow for greater financial well-being (Strömbäck et al., 2017). Therefore, credit counseling can help in having positive financial behaviors, which results in better health and greater financial well-being (O’Neill et al., 2013).

Likewise, the results indicated that financial well-being was negatively associated with financial threat. Previous studies indicate that the results are consistent, since financial well-being indicates an adequate standard of living without financial disruption or instability, while in times of financial crisis or threat, it tends to increase and may be higher than normal due to economic deterioration (Marjanovic et al., 2013). This may also be due to the pessimistic economic outlook people have about the future. Thus, those who assess their own economic situation in comparison with the national or global situation have better ways of coping with financial threats. Unlike pessimistic people who are less prepared for negative economic shocks, the negative effect of financial threats is increased (Barrafrem et al., 2020).

Finally, our results indicated that financial well-being mediated the relationship between personal well-being and financial threats. This indicates that those with decreased personal well-being report greater economic problems and increased financial distress (Fiksenbaum et al., 2017a). The study also showed that there is no indirect relationship between personal well-being and financial threats. This suggests that financial well-being mediates individual well-being resources and financial threats due to the fact that the individual could change his or her behavior in the midst of financial crises by reducing spending and increasing income, seeking employment (de Miquel et al., 2022). Therefore, financial well-being has a function in which it allows the evaluation of personal resources for stress management. However, more studies are needed to extend the assessment of coping and motivations in adverse situations to reduce financial and psychological distress.

Generally, people often make decisions to improve their state and well-being financially. These decisions include spending responsibly, opening savings accounts, and borrowing in order to grow assets and protect financial resources (Sehrawat et al., 2021). However, in the current national and global financial context, financial decisions can be particularly challenging. On the one hand, at the national level, the political crisis that the country (Peru) is going through is challenging for the economic life of Peruvian households, considering that financial well-being depends to a certain extent on political stability and people’s confidence in the government (Barrafrem et al., 2021). In fact, trust or distrust in public institutions is an important pillar to face financial challenges and improve financial well-being (Algan and Cahuc, 2010). On the other hand, at the global level, there is a concern on the part of political leaders to find effective strategies to improve the financial sector, financial well-being, and stability of households (World Bank, 2013). Whereas citizens can easily find themselves trapped in an unfavorable economic situation if not managed with responsible financial behavior, therefore, it is imperative to adopt financial measures such as identifying personality traits, improving financial literacy or specific economic behaviors through appropriate financial education to help people cope in these times of difficult economic and health crises to ensure their financial well-being (Netemeyer et al., 2018; Riitsalu and Murakas, 2019). Moreover, to increase or improve financial well-being, it is necessary to adopt adequate financial strategies that lead to an increase in satisfaction in relation to the financial situation; these strategies include having defined financial objectives in such a way that they help to have a systematic saving for future emergencies, having control over income and expenses through a budget, not generating unnecessary debts, and making expenses according to the financial possibilities that are available; all of these are fundamental to increase financial well-being (Netemeyer et al., 2018; Riitsalu and Murakas, 2019).

The results may be useful to organizations or professionals capable of formulating public policies. Variables such as financial well-being and threats make it possible to develop financial education programs that have an impact on families affected by crises. Because better management of financial affairs could help to control, improve financial skills and decisions, and achieve financial and personal well-being. Likewise, programs should raise awareness among teachers and children in order to motivate them to save from childhood, so that as adults they can increase their level of confidence and make better financial decisions. More cross-cultural studies are needed due to the scarcity of studies and the performance of studies with other sociodemographic characteristics that allow greater representativeness of the adult population. Thus, financial phenomena such as well-being and other variables with different characteristics and dynamics could be tested.

This study has some limitations to consider. First, the study was cross-sectional and cannot adequately explore the causal relationships between variables, hence a more robust analysis. Therefore, longitudinal studies are recommended to test for causal connections. Second, political, social, and economic factors may be different in other countries, which may lead to different results. Third, the self-administered instruments used together may not represent a measure of an individual’s financial behavior and threat.

Personal well-being provides greater overall satisfaction with financial matters, in turn, appropriate financial behavior results in greater financial well-being. Financial well-being provides a standard of living with greater financial stability and makes it possible to cope with financial crises. So lower financial well-being can cause greater financial problems due to the inability to cope with financial threats. Thus, when a person perceives greater well-being, it serves as a basis for promoting financial well-being and contributes to the reduction of financial threats.

The data on which this study is based can be requested from the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the study was reviewed by the ethics committee of the Universidad Peruana Unión (Cod: 2021-CE-EPG-000078). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

BE-D, GM, JP, and WM-G participated in the conceptualization. WM-G, JS, and LS-S were in charge of the methodology and software. WM-G and RC-B performed validation, formal analysis, and research and commissioned data and resource conservation. First draft writing, review, and editing, visualization, and supervision were handled by WM-G, RC-B, JS, and LS-S. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors would like to thank Varisier Noel during the manuscript writing process.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1084731/full#supplementary-material

Alcover, C.-M., Salgado, S., Nazar, G., Ramírez-Vielma, R., and González-Suhr, C. (2020). Job insecurity, financial threat and mental health in the COVID-19 context: the buffer role of perceived social support MedRxiv, 1–30. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.31.20165910

Algan, Y., and Cahuc, P. (2010). Inherited trust and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 100, 2060–2092. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.5.2060

Ato, M., López, J. J., and Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 29, 1038–1059. doi: 10.6018/ANALESPS.29.3.178511

Barrafrem, K., Tinghög, G., and Västfjäll, D. (2021). Trust in the Government Increases Financial Well-Being and General Well-Being during COVID-19. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 31:100514. doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2021.100514

Barrafrem, K., Västfjäll, D., and Tinghög, G. (2020). Financial well-being, COVID-19, and the financial better-than-average-effect. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 28:100410. doi: 10.1016/J.JBEF.2020.100410

Barraza, B. J. S. (2020). Crisis económica mundial del 2008 y su impacto en la evolución de la economía peruana. Quipukamayoc 28, 35–42. doi: 10.15381/quipu.v28i57.15135

Barreto, I. B., Sánchez, R. M. S., and Marchan, H. A. S. (2021). Consecuencias económicas y sociales de la inamovilidad humana bajo COVID – 19 caso de estudio Perú. Lect. Econ. 94, 285–303. doi: 10.17533/UDEA.LE.N94A344397

Bentler, P. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bialowolski, P., Weziak-Bialowolska, D., Lee, M. T., Chen, Y., VanderWeele, T. J., and McNeely, E. (2021). The role of financial conditions for physical and mental health. Evidence from a longitudinal survey and insurance claims data. Soc. Sci. Med. 281:114041. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2021.114041

Botha, F., New, J. P. d., New, S. C. d., Ribar, D. C., and Salamanca, N. (2021). Implications of COVID-19 labour market shocks for inequality in financial wellbeing. J. Popul. Econ. 34, 655–689. doi: 10.1007/S00148-020-00821-2

Braunstein, S., and Welch, C. (2002). Financial literacy: an overview of practice, research, and policy. Fed. Reserv. Bull. 88, 445–457. doi: 10.17016/BULLETIN.2002.88-11

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 21, 230–258. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002005

Brüggen, E. C., Hogreve, J., Holmlund, M., Kabadayi, S., and Löfgren, M. (2017). Financial well-being: a conceptualization and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 79, 228–237. doi: 10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2017.03.013

Carton, F. L., Xiong, H., and McCarthy, J. B. (2022). Drivers of financial well-being in socio-economic deprived populations. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 34:100628. doi: 10.1016/J.JBEF.2022.100628

Chori, A., Bai, N., and Ghezelsofloo, H. (2021). The role of job insecurity during the Corona virus pandemic on the mental health of football schools’ coaches with the mediating role of financial well-being. Sport Psychol. Stud. 11, 295–320. doi: 10.22089/SPSYJ.2021.11312.2232

Miquel, C.de, Domènech-Abella, J., Felez-Nobrega, M., Cristóbal-Narváez, P., Mortier, P., Vilagut, G., et al. (2022). The mental health of employees with job loss and income loss during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of perceived financial stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 19:3158. doi: 10.3390/IJERPH19063158

Diener, E., Lucas, R., and Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective Weil-being: three decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 125, 276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Diener, E., and Oishi, S. (2009). TARGET ARTICLE: the nonobvious social psychology of happiness. Int. J. Adv. Psychol. Theory 16, 162–167. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1604_04

Dominguez-Lara, S. A. (2016). Evaluación de la confiabilidad del constructo mediante el coeficiente H: breve revisión conceptual y aplicaciones. Psychologia. Av. Discip. 10, 87–94.

Durst, S., Palacios Acuache, M. M. G., and Bruns, G. (2021). Peruvian small and medium-sized enterprises and COVID-19: time for a New start! J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 13, 648–672. doi: 10.1108/JEEE-06-2020-0201

Fan, L. (2021). A conceptual framework of financial advice-seeking and short- and long-term financial behaviors: an age comparison. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 42, 90–112. doi: 10.1007/S10834-020-09727-3

Ferreira, M. B., Almeida, F. d., Soro, J. C., Herter, M. M., Pinto, D. C., and Silva, C. S. (2021). On the relation between over-indebtedness and well-being: an analysis of the mechanisms influencing health, sleep, life satisfaction, and emotional well-being. Front. Psychol. 12:1199. doi: 10.3389/FPSYG.2021.591875

Fiksenbaum, L., Marjanovic, Z., and Greenglass, E. (2017a). Financial threat and individuals’ willingness to change financial behavior. Rev. Behav. Finance 9, 128–147. doi: 10.1108/RBF-09-2016-0056

Fiksenbaum, L., Marjanovic, Z., Greenglass, E., and Garcia-Santos, F. (2017b). Impact of economic hardship and financial threat on suicide ideation and confusion. J Psychol. 151, 477–495. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2017.1335686

Folkman, S. (2013). “Stress: appraisal and coping”, in Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. eds. M. D. Gellman and J. R. Turner New York, NY: Springer.

Gathergood, J., and Weber, J. (2014). Self-control, financial literacy and the co-holding puzzle. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 107, 455–469. doi: 10.1016/J.JEBO.2014.04.018

Gerrans, P., Speelman, C., and Campitelli, G. (2013). The relationship between personal financial wellness and financial wellbeing: a structural equation modelling approach. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 35, 145–160. doi: 10.1007/S10834-013-9358-Z

Gonzalez, M. R., Brown, S. A., Pelham, W. E., Bodison, S. C., McCabe, C., Baker, F. C., et al. (2022). Family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: the risks of financial insecurity and coping. J. Res. Adolesc., 1–16. doi: 10.1111/JORA.12776

Grezo, M., and Sarmany-Schuller, I. (2015). Coping with economic hardship: a broader look on the role of dispositional optimism. J. Psychol. 2, 6–14.

Hancock, G. R., and Mueller, R. O. (2001). “Rethinking construct reliability within latent variable systems” in Structural Equation Modeling: Present and Future—A Festschrift in Honor of Karl Joreskog. eds. R. Cudeck, S. D. Toit, and D. Soerbom (Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International), 195–216.

International Wellbeing Group (2006). Personal Wellbeing Index, Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University.

Joo, S. (2008). “Personal financial wellness” in Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. ed. J. J. Xiao (New York, NY: Springer), 21–33.

Kaur, G., Singh, M., and Singh, S. (2021). Mapping the literature on financial well-being: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 71, 217–241. doi: 10.1111/ISSJ.12278

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., and Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling of fit involving a particular measure of model. Psychol. Methods 13, 130–149.

Mahdzan, N. S., Zainudin, R., Abd Sukor, M. E., Zainir, F., and Wan Ahmad, W. M. (2020). An exploratory study of financial well-being among Malaysian households. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 27, 285–302. doi: 10.1108/JABES-12-2019-0120

Mamun, M. A., Akter, S., Hossain, I., Faisal, M. T. H., Rahman, M. A., Arefin, A., et al. (2020). Financial threat, hardship and distress predict depression, anxiety and stress among the unemployed youths: a Bangladeshi Multi-City study. J. Affect. Disord. 276, 1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/J.JAD.2020.06.075

Marjanovic, Z., Greenglass, E. R., Fiksenbaum, L., and Bell, C. M. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the financial threat scale (FTS) in the context of the great recession. J. Econ. Psychol. 36, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/J.JOEP.2013.02.005

Marjanovic, Z., Greenglass, E. R., Fiksenbaum, L., Witte, H.De, Garcia-Santos, F., Buchwald, P., et al., (2015). Evaluation of the financial threat scale (FTS) in four European, non-student samples. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 55, 72–80. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCEC.2014.12.001

Nanda, A. P., and Banerjee, R. (2021). Consumer’s subjective financial well-being: a systematic review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 45, 750–776. doi: 10.1111/IJCS.12668

Netemeyer, R. G., Warmath, D., Fernandes, D., and Lynch, J. G. (2018). How Am I Doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. J. Consum. Res. 45, 68–89. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucx109

O’Neill, B., Sorhaindo, B., Xiao, J. J., and Garman, E. T. (2013). Financially distressed consumers: their financial practices, financial well-being, and health. J. Financ. Couns. Plann. 16, 1–15.

Pascual-Ferrá, P., and Beatty, M. J. (2015). Correcting internal consistency estimates inflated by correlated item errors. Commun. Res. Rep. 32, 347–352. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2015.1089858

Philippas, N. D., and Avdoulas, C. (2019). Financial literacy and financial well-being among generation-Z university students: evidence from Greece. Eur. J. Finance 26, 360–381. doi: 10.1080/1351847X.2019.1701512

Ponchio, M. C., Cordeiro, R. A., and Gonçalves, V. N. (2019). Personal factors as antecedents of perceived financial well-being: evidence from Brazil. Int. J. Bank Mark. 37, 1004–1024. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-03-2018-0077

Prawitz, A. D., Kalkowski, J. C., and Cohart, J. (2012). Responses to economic pressure by low-income families: financial distress and hopefulness. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 34, 29–40. doi: 10.1007/S10834-012-9288-1

Raykov, T., and Hancock, G. R. (2005). Examining change in maximal reliability for multiple-component measuring instruments. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 58, 65–82. doi: 10.1348/000711005X38753

Rea, J. K., Danes, S. M., Serido, J., Borden, L. M., and Shim, S. (2018). “Being able to support yourself”: young adults’ meaning of financial well-being through family financial socialization. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 40, 250–268. doi: 10.1007/S10834-018-9602-7

Richardson, T., Elliott, P., and Roberts, R. (2013). The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33, 1148–1162. doi: 10.1016/J.CPR.2013.08.009

Riitsalu, L., and Murakas, R. (2019). Subjective financial knowledge, prudent behaviour and income. Int. J. Bank Mark. 37, 934–950. doi: 10.1108/IJBM-03-2018-0071

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Russell, B. S., Hutchison, M., Tambling, R., Tomkunas, A. J., and Horton, A. L. (2020). Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent–child relationship. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 51, 671–682. doi: 10.1007/S10578-020-01037-X

Rutherford, L. G., and Fox, W. S. (2010). Financial wellness of young adults age 18–30. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 38, 468–484. doi: 10.1111/J.1552-3934.2010.00039.X

Salameh, P., Hajj, A., Badro, D. A., Abou Selwan, C., Aoun, R., and Sacre, H. (2020). Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic and a collapsing economy: perspectives from a developing country. Psychiatry Res. 294:113520. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYCHRES.2020.113520

Sehrawat, K., Vij, M., and Talan, G. (2021). Understanding the path toward financial well-being: evidence from India. Front. Psychol. 12:638408. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.638408

Shim, S., Xiao, J. J., Barber, B. L., and Lyons, A. C. (2009). Pathways to life success: a conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 30, 708–723. doi: 10.1016/J.APPDEV.2009.02.003

Sinha, G., Tan, K., and Zhan, M. (2018). Patterns of financial attributes and behaviors of emerging adults in the United States. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 93, 178–185. doi: 10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2018.07.023

Soper, D. (2021). A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. Free Statistics Calculators (2020). Available at: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89

Sorgente, A., and Lanz, M. (2017). Emerging adults’ financial well-being: a scoping review. Adolesc. Res Rev 2, 255–292. doi: 10.1007/s40894-016-0052-x

Strömbäck, C., Lind, T., Skagerlund, K., Västfjäll, D., and Tinghög, G. (2017). Does self-control predict financial behavior and financial well-being? J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 14, 30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2017.04.002

Tsang, S., Royse, C. F., and Terkawi, A. S. (2017). Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J. Anaesth. 11, S80–S89. doi: 10.4103/SJA.SJA_203_17

Ullah, S., and Yusheng, K. (2020). Financial socialization, childhood experiences and financial well-being: the mediating role of locus of control. Front. Psychol. 11:2162. doi: 10.3389/FPSYG.2020.02162

Wilson, J. M., Lee, J., Fitzgerald, H. N., Oosterhoff, B., Sevi, B., and Shook, N. J. (2020). Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 62, 686–691. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001962

World Bank (2013). Financial Capability Surveys Around the World: Why Financial Capability Is Important and How Surveys Can Help (No. 80767). Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/693871468340173654/pdf/807670WP0P14400Box0379820B00PUBLIC0.pdf (Accessed September 15, 2022).

Yzerbyt, V., Muller, D., Batailler, C., and Judd, C. M. (2018). New recommendations for testing indirect effects in mediational models: the need to report and test component paths. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 115, 929–943. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000132

Keywords: personal well-being, financial, threats, Peruvian adult, mediation

Citation: Estela-Delgado B, Montenegro G, Paan J, Morales-García WC, Castillo-Blanco R, Sairitupa-Sanchez L and Saintila J (2023) Personal well-being and financial threats in Peruvian adults: The mediating role of financial well-being. Front. Psychol. 13:1084731. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1084731

Received: 30 October 2022; Accepted: 15 December 2022;

Published: 27 January 2023.

Edited by:

Huseyin Çakal, Keele University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Ionel Bostan, Ștefan cel Mare University of Suceava, RomaniaCopyright © 2023 Estela-Delgado, Montenegro, Paan, Morales-García, Castillo-Blanco, Sairitupa-Sanchez and Saintila. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wilter C. Morales-García,  d2lsdGVybW9yYWxlc0B1cGV1LmVkdS5wZQ==; Jacksaint Saintila,

d2lsdGVybW9yYWxlc0B1cGV1LmVkdS5wZQ==; Jacksaint Saintila,  c2FpbnRpbGFqYWNrQGNyZWNlLnVzcy5lZHUucGU=

c2FpbnRpbGFqYWNrQGNyZWNlLnVzcy5lZHUucGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.