- Department of Media and Communication, The City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

This study seeks to explain the wide acceptance of the stringent zero-COVID policy in two Chinese societies—Mainland China (n = 2,184) and Taiwan (n = 1,128)—from perspectives of cultural values and trust. By employing the efficacy mechanism, this study identifies significant indirect effects of trust in government and key opinion leaders (KOL) on people’s policy acceptance in both societies. Namely, people who interpret the pandemic as a collectivist issue and who trust in government will be more accepting of the zero-COVID policy, whereas those who framed the pandemic as an individual issue tend to refuse the policy. Trust in government and KOLs foster these direct relationships, but trust in government functions as a more important mediator in both societies. The different contexts of the two Chinese societies make the difference when shaping these relationships. These findings provide practical considerations for governmental agencies and public institutions that promote the acceptance of the zero-COVID policy during the pandemic.

Introduction

Starting from the end of 2019, COVID-19 has infected more than 617.6 million people worldwide and caused over 6.5 million deaths as of October 2022 (WHO, 2022). This long-lasting pandemic has sprawled and wreaked havoc on the economy as well as daily lives worldwide. It has been estimated that due to the disease, the global economy shrank by 4.4% in 2020 alone (BBC, 2021), with 6.5% of the global population out of work (The United Nations, 2021). To recover from the damage caused by the pandemic and get back to the pre-pandemic routines, countries including Denmark, South Korea, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States have suggested that these countries must “live with the covid” soon (CNN, 2021; NPR, 2021; BBC, 2022), which means lifting stringent public health interventions such as social distancing and masking, deemphasizing testing, and treating the disease the same as other illnesses like influenza (Hartman, 2021). There are still countries or regions sticking with the “zero-COVID” strategy, and Mainland China as well as Taiwan are two representatives. Contrary to the “living with the covid,” the “zero-COVID” strategy utilizes rigid preventive measures including mass lockdowns, mandated testing, international travel bans, and mandatory quarantines to crush any hint of an outbreak (The Economist, 2022). From the beginning of the pandemic in December 2019, both Mainland China and Taiwan adopted this “zero-COVID” strategy. As the place where the first case of COVID-19 was discovered, Mainland China has remained vigilant about infections, and has no plan to abandon this strategy. Taiwan maintained strict intervention against the disease throughout the period of this study (December 2021). Compared with protests against the lockdowns in the West (e.g., in Germany, the Netherlands, and Austria), these two regions have endured tightened public health controls almost without public resistance. What could explain the overall acceptance of the “zero-COVID” strategy in these two Chinese societies?

The “individualism–collectivism” (Chen et al., 2015) dimension of cultural values has been long considered one explanation for people’s attitudes toward interventionist policies from the state. Intuitively, collectivism has been associated with more obedience and tolerance toward interventionist policies, while individualism reduces people’s preference for state intervention (Nikolaev et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2021; Kemmelmeier and Jami, 2021). Under the context of the pandemic, collectivist values have been proven to increase people’s compliance with preventive measures such as social distancing, while individualist values work in the opposite way (Wang, 2021). Specifically, a recent study on Chinese university students has demonstrated the significant effect of individual-level cultural orientations (i.e., collectivism–individualism) on people’s public health policy compliance during the COVID period (Xiao, 2021).

However, what factors give rise to such a division is still under discussion. The internal factors of “I-C” dichotomy, which is argued by Hofstede et al. (2005) as well as Pitlik and Rode (2017), may be inherent cultural traits and beliefs that lead to differences in policy acceptance (Otto et al., 2020; Atalay and Solmazer, 2021; Lyu et al., 2022). Apart from internal factors, trust has been found to play a siginificant role in many behavioral outcomes (Huang et al., 2021; Dai et al., 2022). Thus, we argue that people’s trust in government and key opinion leaders (i.e., KOLs), subjected to influences of self-efficacy and cultural values, may also shape their acceptance of zero-COVID policy. The interactions between these social actors and values of “I-C” illuminate how cultural values influence people’s policy acceptance and may generate more practical implications for practitioners in terms of mobilizing support for a given policy.

We hereby present three research questions to examine the relationship among cultural values, policy attitudes, and the role of trust in government and media: (1): How will cultural values, including collectivist and individualist values, predict the acceptance of the “zero-COVID” strategy in Mainland China and Taiwan? (2): How will people’s trust in government and KOLs mediate the association between cultural values and the “zero-COVID” strategy? and (3) To what extent does the effect of cultural values on people’s policy acceptance differ in Mainland China and Taiwan? Moreover, the research aims to contribute to the current studies on cultural values and policy acceptance by introducing the effect of self-efficacy on people’s trust and examining the interplay between cultural values and trust in policy attitudes. Policy recommendations derived from the analysis will work as the guidelines for campaigns on not only public health measures against the pandemic, but other policies as well.

Individualism–collectivism dichotomy

Culture makes the public institutions that guide people’s behaviors. As the pandemic threatens the stability of countries around the world, numerous studies have been devoted to how different cultural dimensions—including the individualism–collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance, and masculinity-femininity factors identified by Hofstede (1983)—have managed to shape people’s compliance with COVID-19 preventive measures, such as social distancing, vaccination, and self-reporting of infection (Huynh, 2020; Travaglino and Moon, 2021; Voegel and Wachsman, 2022; Lu, 2022). The dichotomy of individualism vs. collectivism has been cited as an explanation for people’s acceptance of interventionist policies before and during the pandemic (Chen et al., 2015; Travaglino and Moon, 2021). Specifically, according to Hofstede et al. (2005), “collectivism” is described as a kind of cultural value that integrates people into “strong, cohesive in-groups, often extended families that continue protecting them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty and oppose other in-groups.” In addition, studies emphasized the core principle of collectivism (e.g., the set of cultural values that make people value group interests more than individual interests; Wang, 2021; Lyu et al., 2022).

In studies related to the political culture in East Asia, “collectivism” is considered one of the major features that shapes the political institution. Shi (2014) specified several political cultural traits in Greater China, and traits like allocentric self-interest, conflict avoidance, and hierarchical orientation toward authority share common features with “vertical collectivism” (Rokeach, 1973; Fiske, 1992; Triandis and Gelfand, 1998). By this token, collectivism plays a significant role in understanding the policy attitudes of people in Greater China. Moreover, despite spending decades in diverse political and economic systems, people in China and Taiwan share similarities in cultural orientation (Head and Sorensen, 1993; Ferle et al., 2008; Bedford et al., 2021) and collectivist values (Cheung and Chow, 1999).

As for individualism, it refers to a society that is bound with loose interpersonal ties in which every member is expected to fend for oneself and his/her immediate family (Hofstede et al., 2005). The origin of this idea dates back to the Age of Enlightenment, during which the concept of individualism in philosophy involved the maximization of individual welfare and freedom (Lukes, 1971). According to Triandis et al. (1993), individualists consist of four features: (1) loosely linked persons in individual terms independent of collectives; (2) driven by own preferences, interests, and rights; (3) prioritizing the rational analyses of the benefits and drawbacks when interacting with others; and (4) individual goals outweighing collective goals, detached from their in-group members. Confrontation and competition are often ready to erupt among individualists (Triandis, 1995).

Despite the fact that both Mainland China and Taiwan are embedded in the relatively collectivist culture, collectivism is not the only element in these societies (Huang et al., 2018); individualism also plays a significant role at both the individual and societal levels (Sima and Pugsley, 2010). Individualist elements were found to be increasingly important in Chinese people’s evaluation of their personal pleasure and life satisfaction (Steele and Lynch, 2013). Particularly, Bao et al. (2022) revealed that, during the past several decades in China, individualism has grown to be acknowledged and linked with various perspectives of life (e.g., income and wealth). Moreover, Pelham et al. (2022) identified the existence of cultural shifts from collectivism to individualism in many societies, which they attribute to the factors such as the rise of national wealth and urbanization (Huggins and Debies-Carl, 2015). Empirical studies have also lent credence to this cultural shift in China (Cao, 2009). Using algorisms, Hamamura et al. (2021) analyzed 50-year printed texts in China to reveal the cultural shift and rising individualism. Against this backdrop, it is important to analyze the effect of individualism on individuals’ acceptance of policies in a comparatively collectivist culture.

Individualism–collectivism and acceptance of interventionist policies: Employing issue interpretation as proxies

Due to differences in cultural traits, individualism has been associated with a less interventionist institution that respects the rights of others, rule of law, and is conducive to market capitalism (Tabellini, 2010). By contrast, collectivism is related to a hierarchical and orderly society that nourishes more government interventions and even authoritarianism (Kemmelmeier et al., 2003).

Popular explanations for the effect of I-C dimension and preferences over government interventions usually deal with cultural traits associated with individualism and collectivism, such as self-direction and self-determination (Pitlik and Rode, 2017). According to Pitlik and Rode (2017)’s theory, individualists find it hard to comply with interventionist policies due to high levels of both self-determination and self-direction, while collectivists are the other way around. Similar patterns are also found in existing empirical studies on preventive measures. For example, Maaravi et al. (2021) found that people ranking high in collectivist values are more likely to adhere to health guidelines issued by the government. The same conclusions are also found in studies of Wang (2021) and Bok et al. (2021), where people who have more collectivist beliefs are more willing to comply with preventive mandates.

Conversely, individualist values have been regarded as barriers to people’s acceptance of interventions from the government. The analysis from Chen et al. (2021) shows that in areas where individualistic culture was more prevalent (e.g., the United States), people were less likely to follow the lockdown regulations. Likewise, Yu et al. (2021) demonstrated in an empirical study conducted in China that stronger beliefs in individualism are associated with vaccine resistance among Chinese.

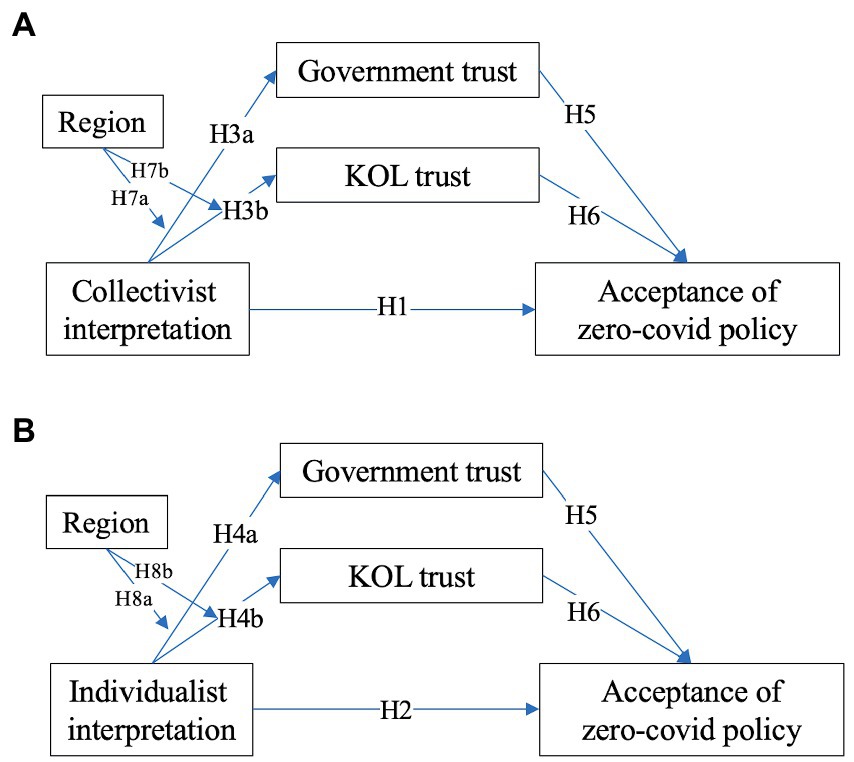

We hereby consider the “zero-COVID policy” a form of preventive mandates in the Chinese context since governments in Chinese societies (e.g., Mainland China and Taiwan) have insisted on the zero-COVID policy to combat the COVID. Specifically, we used respondents’ issue interpretation of pandemic as proxies for their values. Our use of this approach draws on various works. Smeekes and Verkuyten (2013) wrote that collectivists, whose sense of existence as well as personal identity hinges on group membership and social identity, are more motivated to defend the group interests when facing existential risks. Such collectivist beliefs can shape people’s interpretation of an issue (Travaglino and Moon, 2021) and a collective disaster framing that highlights social obligation is more palatable to them (Oyserman et al., 1998). However, individualists, whose sense of existence and personal identity are determined by personal rather than group factors (Smeekes and Verkuyten, 2013), would be more likely to accept a more individual-oriented perspective of the pandemic after evaluating the trade-offs between collective actions and their own self-determination (Travaglino and Moon, 2021). In essence, then, we have employed interpretation of pandemic as a means to discern people’s different foci on how they develop a sense of continued existence over time and space (from which they derive personal identity). Therefore, based on the existing studies reviewed, we propose the following hypotheses (Figure 1):

H1: People’s collectivist issue interpretation of the pandemic is positively associated with their acceptance of the zero-COVID policy.

H2: People’s individualist issue interpretation of the pandemic is negatively associated with their acceptance of the zero-COVID policy.

Cultural values, political trust, and social trust: The self-efficacy perspective

Beliefs and attitudes, however, can also be shaped by external factors such as other social actors instead of being solely determined by individuals’ cultural values. Trust is another essential construct that may affect individuals’ attitudes during a certain crisis. Defined as the willingness to take risks (Johnson-George and Swap, 1982), trust has frequently been adopted to explain individuals’ decision-making processes when encountering a crisis (e.g., pandemic crisis, Algan et al., 2021; financial crisis, Earle, 2009). Cultural values have been found to affect trust in many empirical studies (e.g., Shi, 2001; Hogler et al., 2013; Xu, 2020). The underlying mechanism behind cultural values and people’s trust in certain subjects lies in their perception of self-efficacy. According to Rogers (1975), self-efficacy is people’s ability to perform a specific response. People’s self-efficacy perception will influence their decision-making, aspirations, problem-solving, etc. (Bandura, 1991). When they perceive a low level of self-efficacy in a crisis scenario, people will put more trust in other entities (e.g., government and other institutions; Rogers, 1975; Armaş et al., 2017). On the contrary, higher levels of self-efficacy assume the view of the self as competent and are assumed to be correlated with lower trust in other entities (Gecas, 1989).

Bandura (1986) suggested that self-efficacy can be socially constructed. Numerous studies have shown that individualism as a cultural value is associated with higher self-efficacy, while collectivism is associated with lower self-efficacy (Oettingen, 1995; Xie et al., 2006; Choi and Kim, 2019). Motivated by different levels of self-efficacy, individualists and collectivists invest in different types of trust relations. Due to their emphasis on higher self-reliance and self-refinement as two key components of self-efficacy (Xie et al., 2006), individualists demonstrate less trust in the government (Putnam, 2000); on the other hand, they may have higher levels of social trust because they are more autonomous and seemingly liberated from social bonds, which leads to their higher trust in each other (Realo et al., 2008). In contrast, influenced by in-group solidarity and respect for authority figures, collectivists are more likely to have higher levels of trust in political institutions (Jakubanecs et al., 2018). However, there are also studies showing that collectivism is positively associated with higher levels of social trust due to the benevolence toward others and interdependence underlying collectivist cultures (Shin and Park, 2004).

Against this backdrop, the current study will further focus on trust in government (to manifest political trust) and trust in key opinion leaders (to manifest social trust).

Trust in the government, as a key component of political trust, has been emphasized to explain individuals’ behaviors in response to a huge, worldwide crisis (see Blind, 2007 for a review). During a pandemic, the government functions as the headquarters of a nation. Given the role of government and the emotional value attached to nations, individuals’ trust in government is required as an in-group trust rather than relying on other types of out-group trust; citizens will rely on the government to protect them (Klein and Robison, 2020; Stevens and Haines, 2020) and comply with preventive measures based on their trust in the government (Lyu et al., 2022).

Trust in key opinion leaders (KOL) is our major measurement for social trust, as opinion leaders are wielding growing power in the public sphere under the era of Web 2.0. Opinion leaders are people with a substantial level of influence within their network and are capable of influencing others’ opinions (Shah and Scheufele, 2006; Parau et al., 2017).

Trust in KOLs can also be considered social trust because trust is developed through interpersonal communications between KOLs and members within a community through knowledge and resource sharing (Liu et al., 2019). As they function as a mediator between the media and the public, opinion leaders reinforce the acceptance of certain opinions in the public. During a pandemic, people will also rely on opinion leaders to obtain support. Due to the relationship among political trust, social trust, and the “I-C” dimension, we hypothesized (Figure 1):

H3: People’s collectivist issue interpretation positively predicts (a) their trust in the government and (b) their trust in KOLs.

H4: People’s individualist issue interpretation negatively predicts (a) their trust in the government, but positively predicts (b) their trust in KOLs.

Trust and policy acceptance

Both political trust (measured by trust in government) and social trust (measured by trust in KOLs) can be correlated with policy acceptance. Political trust is essential in determining people’s political behaviors such as political participation (Huang et al., 2017) and policy acceptance (Rubin et al., 2009). In the realm of public health management, trust in public institutions has been associated with people’s acceptance of authorities’ recommendation (Prati et al., 2011; Travaglino and Moon, 2021; Liu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). In this vein, a positive relationship between political trust and the acceptance of the zero-COVID policy can be assumed.

The relationship between social trust and policy acceptance is evidenced by illustration of links of Putnam (1993)’ among public participation, social capital, and the implementation of policies. However, in the case of pandemic, the relationship between social trust (represented by trust in KOLs in the article) and policy acceptance remains under debate (Jäckle et al., 2022). Kelly et al. (1991) indicated that the intervention with key opinion leaders would reduce HIV risk behaviors in the general population. Similarly, Nisbet and Kotcher (2009) examined the influence of opinion leader campaigns on people’s attitudes toward climate change. On the other hand, opposition from the opinion leadership results in public resistance against the policy, especially when the policy is at odds with personal judgment and well-being. In China, the public resistance against the Chinese government’s indifference on the death of Dr. Li Wenliang, a whistleblower of COVID-19, is another example of KOL-led outcry on policy issues (Tsai, 2021). As the zero-COVID policy is controversial due to its stringent intervention in people’s life routine, we propose treating opinion leaders as potential opponents of the policy because higher trust in opinion leaders may lead to lower acceptance of the policy. Given the relationship between trust and policy acceptance, we hypothesized (Figure 1):

H5: Trust in the government will positively predict people’s acceptance of zero-COVID policy.

H6: Trust in the KOLs will negatively predict people's acceptance of zero-COVID policy.

The moderating role of regions

Additionally, we take into consideration contextual factors of two societies as possible moderators that affect the path connecting people’s cultural values with their trust. Mainland China and Taiwan share several common features in terms of political cultures, including similar beliefs in allocative self-interests, the avoidance of conflicts, and a hierarchical relationship with the authority (Shi, 2014). These similarities control the influence of cultural values between both regions, while differences in political and media environments provide the necessary comparison for how external factors influence the effect of cultural values on the policy acceptance.

Mainland China and Taiwan differ in their political system, traditionalist inclination, and preventive measures against the COVID. The political systems in Mainland China and Taiwan are distinct; since 1949, the Chinese Communist Party has ruled the mainland, but Taiwan’s political system has seen considerable changes in the past decades (Huang et al., 2016). Moreover, the level of traditionalist inclination in these two societies differs. Wong et al. (2011) suggested that a higher level of traditionalist orientation appeared in societies with a long history, such as Mainland China, and economic development does not always imply a decline in traditionalism. Furthermore, although complying with the zero-COVID policy, the two regions present certain distinctions in their strictness of preventive policies. Mainland China sticks to the rigorous zero-COVID policy, enacting lockdown measures and tightened controls in high-risk areas, while Taiwan does not plan to implement the lockdown policies as stringently as Mainland (South China Morning Post, 2022).

Given the possible distinctions between the two Chinese societies, we hypothesized a moderating role of the region on the relationship between cultural values and people’s trust in government and KOLs, as follows (Figure 1):

H7: Region moderates the relationships between people’s collectivist issue interpretation and (a) their trust in the government and (b) their trust in KOLs.

H8: Region moderates the relationship between people’s individualist issue interpretation and (a) their trust in the government and (b) their trust in KOLs.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

From November to December 2021, online surveys were conducted in Mainland China and Taiwan with participant recruitment overseen by independent agencies Rakuten Insights in Mainland China and Chungliu Education Foundation in Taiwan. Based on the 2010 Mainland population census, a mix of Probabilities Proportional to Size (PPS) sampling and quota sampling with gender and age was used in Mainland China (November to December 2021). The PPS and quota sampling were adopted for two reasons. First, as mentioned by Zhang et al. (2020), quota sampling enables researchers to target typical subpopulations with good control over the recruitment process. Second, they demonstrate the representativeness of the sample (Wartberg et al., 2014) in fixed targets concerning age and gender, and other demographic features. In summary, we adopted a combination of PPS sampling and quota sampling to ensure the samples in Mainland China were sufficiently representative with respect to the demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, and residence areas). In Taiwan, we utilized Random Digit Dialing (RDD) sampling based on the Taiwan 2020 household registration database (December 2021). All participants in these two regions were asked to complete an online survey on QuestionPro (in Mainland China) and SurveyCake (in Taiwan).

A total of 3,312 valid responses were received (nmainland = 2,184, nTaiwan = 1,128). Pretests with 10 respondents in each region were completed to confirm the questionnaire’s validity and reliability. Back-translation was accomplished to ensure that the original English questions were appropriately delivered (Brislin, 1970).

Demographics of the sample

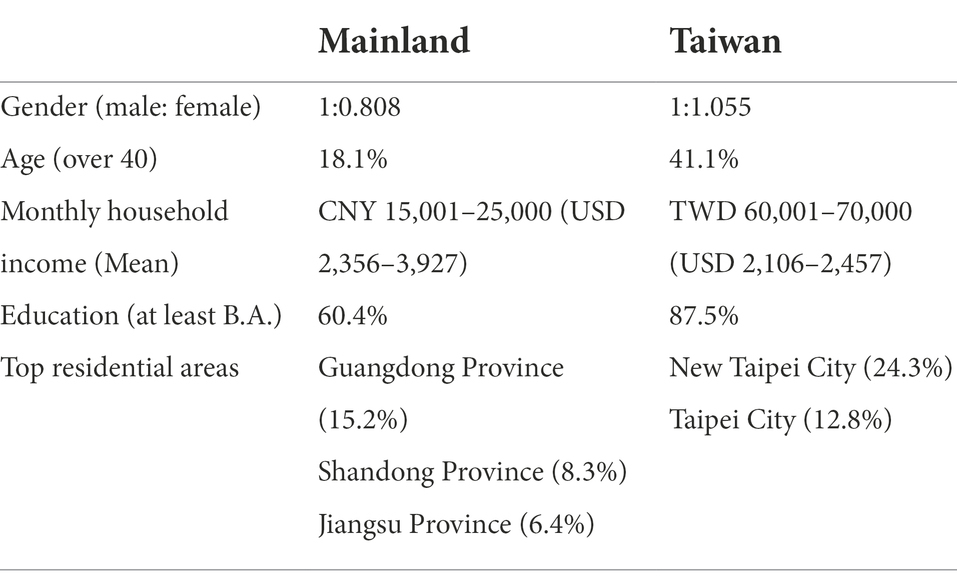

Demographic profiles (i.e., gender, age, and education) of the samples in the two societies were presented in Table 1. Gender proportion in Taiwan was close to 1:1, whereas the number of male respondents was slightly higher than females in Mainland China (1:0.808). Around 41.1% of respondents in Taiwan were over the age of 40 while only 18.1% of participants in Mainland China were in that age group.

The average income of participants in Mainland China was USD 2,356–3,927, while those in Taiwan reported a lower average income of USD 2,106–2,457. Participants in Taiwan received a higher level of education with 87.5% having at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with 60.4% in Mainland.

Participants were selected from 26 provinces or municipalities across the residential regions of Mainland China. Guangdong Province (15.2%), Shandong Province (8.3%), and Jiangsu Province (6.4%) were the top three provinces with the most participation. Respondents were recruited from 22 cities or counties in Taiwan, with New Taipei City (24.3%) and Taipei City (12.8%) ranking first and second.

Measures

As mentioned in the Literature Review, we used issue interpretation as proxies for respondents’ I-C orientation. Detailed measurements are described as follows.

Collectivist issue interpretation of pandemic, as an indicator for people’s orientation toward collectivist values, was measured with three question items on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The question items included the “COVID-19 pandemic is mainly a social/group/national issue.” The responses were then averaged to create collectivist issue interpretation of pandemic (M = 5.33, SD = 1.03, Cronbach’s α = 0.78).

Individualist issue interpretation of pandemic, as an indicator of people’s orientations toward individualist values, was measured with two question items on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree), including the “COVID-19 pandemic is mainly a privacy/personal issue.” The responses were then averaged to create individualist issue interpretation of pandemic (M = 4.16, SD = 1.40, Cronbach’s α = 0.74).

Trust in government (KOLs) was measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly distrust to 7 = strongly trust) based on previous empirical studies (Han and Windsor, 2011; Alotaibi et al., 2019). The question items in Mainland China included trust in experts, key opinion leaders on the Internet (i.e., WeChat official accounts/Weibo in Mainland and the Internet in Taiwan), and opinion leaders from TV/newspaper (M = 4.66, SD = 1.11, Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

Trust in government was measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly distrust to 7 = strongly trust) based on previous studies (Cook and Gronke, 2005; Uslaner and Brown, 2005). The question items in Mainland China included trust in the central government, local government, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Items in Taiwan included trust in central government, county/city government, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and County/City Public Health Bureau (M = 5.36, SD = 1.23, Cronbach’s α = 0.90).

Acceptance of the zero-COVID policy was adapted from scale of Courneya and Bobick (2000), measured by two subgroups: attitudes toward the zero-COVID policy and attitudes toward the living with covid strategy. Under each subgroup, participants were asked “I agree with the zero covid/living with covid strategy,” “This zero covid/living with covid strategy is effective,” “This zero covid/living with covid strategy is beneficial,” and “This zero covid/living with covid strategy is wise.” Responses to the questions were recorded on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Answers for both subgroups were averaged first. The acceptance rates of the zero-COVID policy were computed with the average attitudes toward the zero-COVID policy deducting average attitudes toward the living with covid strategy (M = 0.92, SD = 2.06, zero-COVID strategy Cronbach’s α = 0.94, Living with the covid strategy Cronbach’s α = 0.97).

Region was considered as a categorical variable in which Mainland China was coded as 1 and Taiwan was coded as 0.

Demographics, including participants’ age, gender, education, monthly household income, and with/without children, were included as control variables.

Results

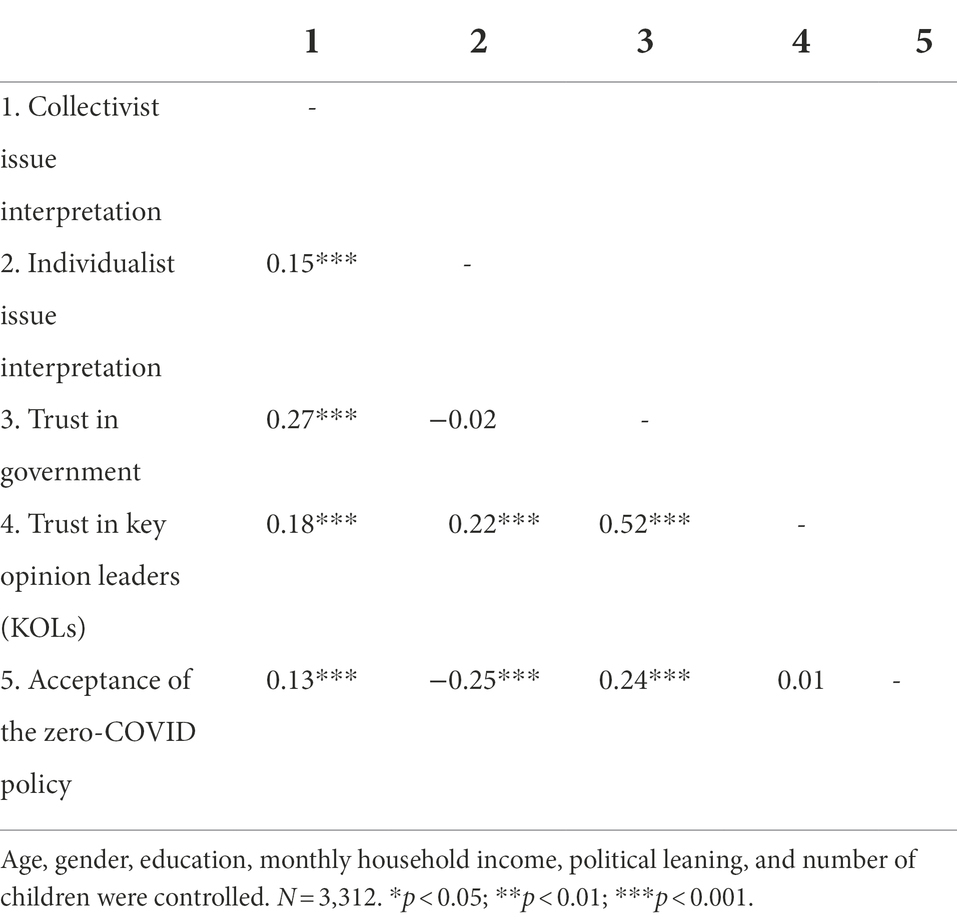

We first used SPSS to conduct parametric correlation analyses of the study variables in two databases (Table 2) and discovered that the majority of the study variables, including collectivist issue interpretation of pandemic, individualist issue interpretation of pandemic, trust in government, trust in key opinion leaders (KOLs), and acceptance of the zero-COVID policy, were significantly correlated. Moreover, we conducted a Bonferroni correction to protect from Type I Error. Five correlation analyses on the same dependent variable would suggest a necessity for a new value of p equal to the original alpha-value (αoriginal = 0.05) divided by the number of correlations: (αaltered = 0.05/5) = 0.01. To decide if any of the five correlations is statistically significant, the value of p must be p < 0.01.

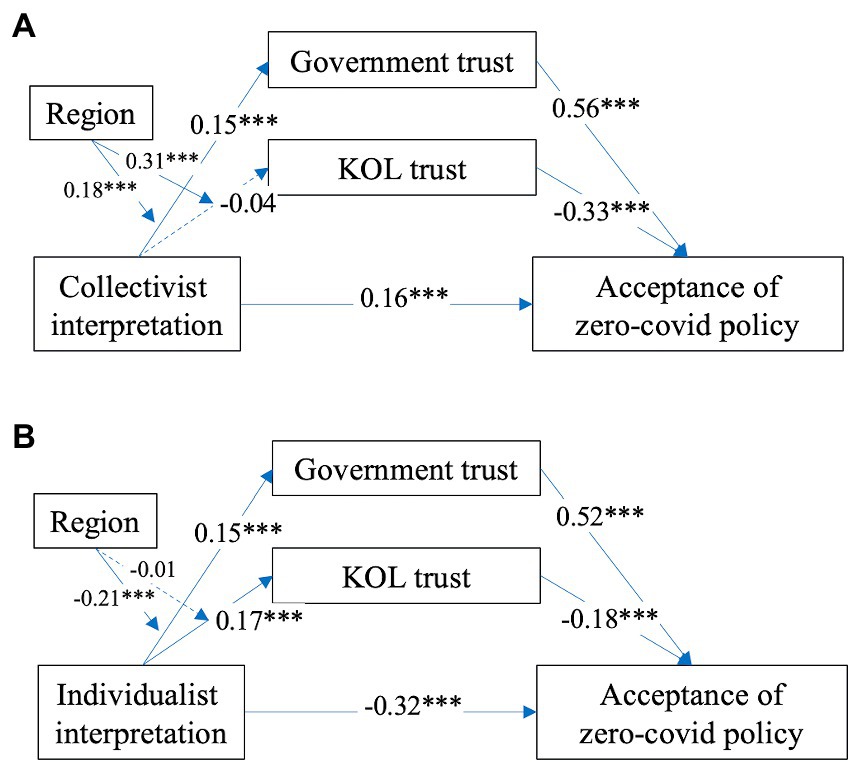

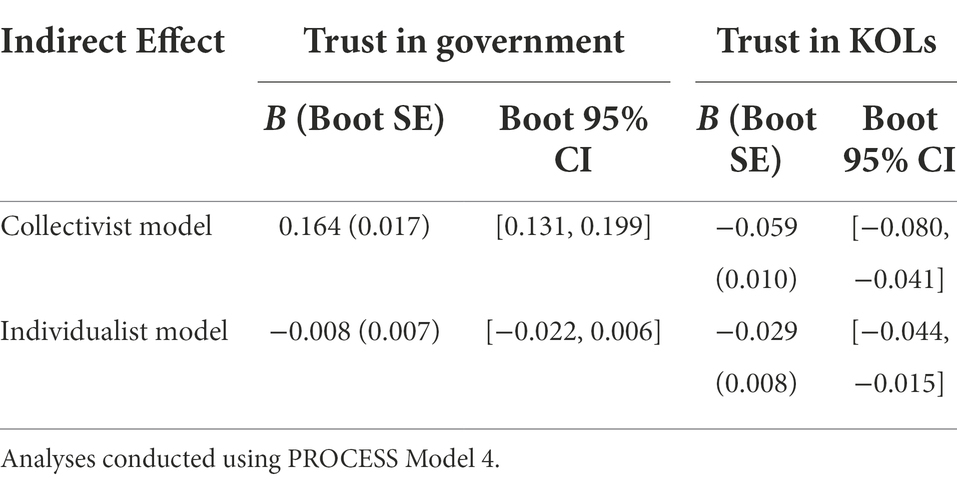

We then adopted PROCESS macro model 4 in SPSS (Hayes, 2017) to test the hypotheses. PROCESS is a widespread technique to study the mediation effects, and it is straightforward to use (Hayes, 2012). The results in Figure 2 showed that controlling for demographics, people’s collectivist issue interpretation of the pandemic was significantly correlated with their acceptance of the zero-COVID policy (β = 0.16, p < 0.001). Thus, H1 was accepted. The zero-COVID strategy was more likely to be endorsed by people who regarded the COVID-19 epidemic as a collective concern. At the same time, the results revealed that people’s individualist issue interpretation of the pandemic was negatively correlated to their acceptance of the zero-COVID policy (β = −0.32, p < 0.001). Thus, H2 was supported. In these two societies, the more that people tended to interpret the COVID-19 pandemic as an individual issue, the more likely they were to accept the zero-COVID policy.

In response to H3, which concerned the relationship between collectivist issue interpretation of the COVID-19 pandemic and trust in KOLs and the government, our results (Figure 2A) showed that collectivist issue interpretation was significantly correlated with trust in government (β = 0.15, p < 0.001). People were more likely to trust the government when they considered the COVID-19 pandemic a collective event. As for trust in key opinion leaders, our findings indicated that collectivist issue interpretation of the COVID-19 pandemic was not significantly correlated with people’s trust in KOLs (β = −0.04, p = 0.22). Thus, H3 was partially supported.

Regarding H4, which focused on the relationship between people’s individualist issue interpretation of the COVID-19 pandemic and the trust in KOLs as well as the government, our findings (Figure 2B) demonstrated that individualist issue interpretation was positively correlated with trust in government in Mainland China and Taiwan (β = 0.15, p < 0.001). People who considered the COVID-19 outbreak a personal issue would show a higher level of trust in government. In terms of trust in key opinion leaders (KOLs), our results suggested that individualist issue interpretation of the COVID-19 epidemic was positively correlated to people’s trust in KOLs (β = 0.17, p < 0.001). Thus, H4 was supported.

H5 and H6 implied the relationship between government trust, KOL trust, and people’s acceptance of the zero-COVID policy. Our findings (Figure 2) showed that trust in government positively correlated with people’s acceptance of the zero-COVID policy (collectivist model: β = 0.56, p < 0.001; individualist model: β = 0.52, p < 0.001). Thus, H5 was supported. This indicated that those with higher trust in government were more likely to have positive attitudes toward the zero-COVID policy. Considering the KOLs trust, our results revealed that trust in KOLs negatively correlated with people’s acceptance of the zero-COVID policy (collectivist model: β = −0.33, p < 0.001; individualist model: β = −0.18, p < 0.001). People with a higher level of trust in KOLs would be less likely to adopt the zero-COVID policy. Thus, H6 was supported.

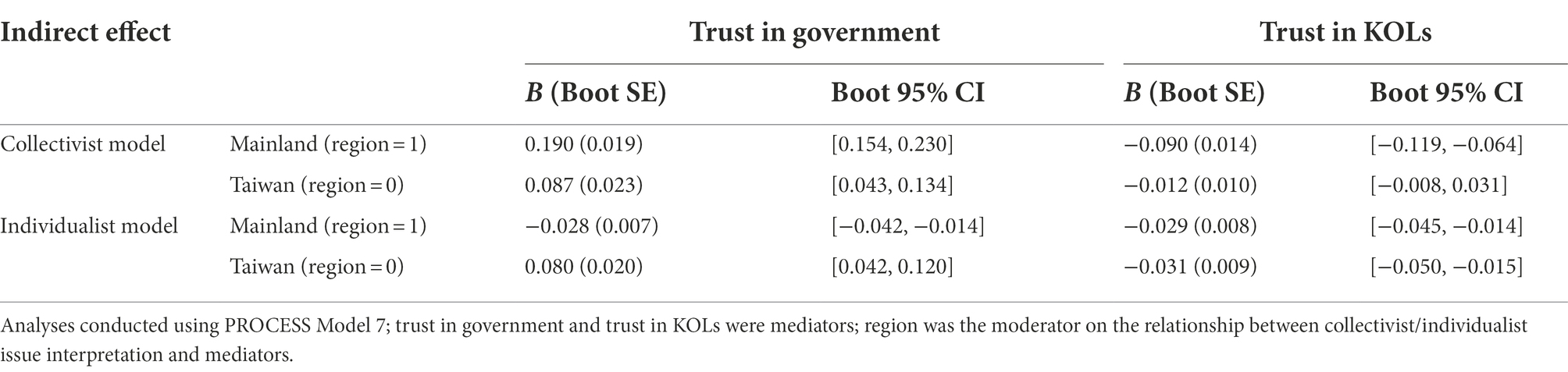

Regarding H7 and H8, which concerned the moderation effect of region on the relationships between people’s collectivist issue interpretation and their trust in the government and trust in KOLs. Our results (Figure 2A) demonstrated that region was a significant moderator of the relationship between people’s collectivist issue interpretation and their trust in the government (β = 0.18, p < 0.001). It also significantly moderated the relationship between people’s collectivist issue interpretation and trust in KOLs (β = 0.31, p < 0.001). Thus, H7 was supported. In response to H8, which evaluated the moderating role of region, results (Figure 2B) revealed that region was a significant moderator of the relationship between people’s collectivist issue interpretation and their trust in the government (β = −0.21, p < 0.001). However, the region was found to be an insignificant moderator on the relationship between people’s individualist issue interpretation and trust in KOLs (β = −0.01, p = 0.70). Thus, H8 was partially supported.

The results in Table 3 suggested the indirect effect of cultural values on the acceptance of the zero-COVID policy. For the path from collectivist issue interpretation of the COVID-19 pandemic to policy acceptance, trust in government was a significant mediator. Trust in KOLs was also a significant mediator of this path. For the path from individualist issue interpretation of the COVID-19 pandemic to policy acceptance, trust in government was not a significant mediator, while trust in KOLs was a significant mediator of the path. Moreover, the difference between two indirect paths (i.e., trust in government and trust in KOLs) was significant.

The results in Table 4 showed the conditional indirect effect of cultural values on zero-COVID policy acceptance. For the path from collectivist issue interpretation of COVID-19 epidemic to policy acceptance, trust in government was found to be a significant mediator in both conditions. Trust in KOLs was a significant mediator of this path in Mainland China but an insignificant mediator in Taiwan. For the path from individualist issue interpretation of COVID-19 pandemic to policy acceptance, trust in government was a significant mediator in both conditions. In both conditions, trust in KOLs was also a significant mediator of the path.

Generally, the direct and indirect effects of collectivist issue interpretation accounted for 11% of the variance in the zero-COVID policy acceptance. The direct and indirect effects of individualist issue interpretation accounted for 14% of the variance in the acceptance of the zero-COVID policy.

Discussion

Under the continually severe pandemic, people’s attitudes toward the covid policy make a difference. The current study suggested that cultural values (i.e., collectivism vs. individualism) directly and indirectly influence people’s acceptance of the zero-COVID policy implemented by the government. With two constructs (i.e., trust in government and trust in key opinion leaders), this study unfolded the underlying mechanism toward the zero-COVID policy acceptance (i.e., efficacy mechanism).

By examining the theoretical framework in Figure 1, this study indicated the direct effect of cultural values on policy acceptance, the mediating role of trust in government, and trust in key opinion leaders in the direct relationship between two Chinese societies. Specifically, people who interpreted the pandemic as a collectivist issue were more likely to accept the zero-COVID policy, whereas individualist issue interpreters tended to reject the policy. Moreover, the cultural orientation of “I-C” both significantly and positively predicts people’s trust in government and KOLs. True distinctions lying in the contexts of two Chinese societies shape this relationship. Furthermore, trust in government promoted people’s policy acceptance, whereas trust in KOLs impeded their acceptance of the zero-COVID policy.

Individualism–collectivism dichotomy and zero-COVID policy acceptance

This study suggested a direct relationship between cultural values and people’s acceptance of the zero-COVID policy in two Chinese societies. Specifically, collectivist issue interpretation positively predicted their policy acceptance. The more likely people interpreted the pandemic as a collectivist issue, the more likely they were to accept the zero-COVID policy. In addition, this study indicated a negative relationship between individualist issue interpretation and people’s acceptance of the zero-COVID policy in Mainland China and Taiwan. People who tended to interpret the pandemic as an individual issue were less likely to adopt the zero-COVID policy. This finding is congruent with previous studies concerning people’s cultural orientations in other contexts (e.g., Cheung and Chow, 1999). Ferle et al. (2008) suggested that respondents from Mainland China and Taiwan reported more collectivist values than individualistic values, demonstrating the proportional importance of collectivism in economies and advertising industries.

The individualism–collectivism dichotomy explained policy compliance behaviors among people in both societies. This finding suggested the significant impact of cultural values on individuals’ policy acceptance. Practically, governmental institutions may provide the collectivist framing about the pandemic that might enhance individuals’ social identity within a group (e.g., community and country), which would, in turn, cultivate a positive attitude toward the zero-COVID policy.

Collectivist issue interpretation and higher levels of political trust

The current study revealed that collectivist issue interpretation would positively predict individuals’ trust in government in two Chinese societies. When people adopted a collectivist issue framing of the pandemic, they presented a higher level of trust in government. However, the relationship between collectivist issue interpretation and trust in KOLs was not significant.

The positive association between collectivist issue interpretation and trust in government is consistent with our expectation that given the self-efficacy mechanism, collectivists generally perceived less self-efficacy which impelled them to rely on and seek support from other entities (e.g., support from institutions or individuals; Choi and Kim, 2019). Moreover, this finding is in line with previous empirical studies that suggest collectivist values will enhance in-group trust (Pathak and Muralidharan, 2016) and that the country functions as a typical type of in-group (Yuki, 2003). Furthermore, the positive relationship between collectivist values and political trust has been revealed in studies conducted in other geographic regions (e.g., a 52-country study, Leonhardt et al., 2020; study in Australia, Shin and Park, 2004).

For the insignificant path from collectivist issue interpretation and trust in KOL, we conducted a post-hoc analysis to examine this relationship in the two societies, respectively. Results indicated that the collectivist issue interpretation of the COVID-19 pandemic positively correlated with people’s trust in KOLs in Mainland China (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) and presented a nonsignificant correlation in Taiwan (β = −0.02, p = 0.48). Possible explanations may lie in the nature of opinion leaders and the more diverse media environment in Taiwan. People with collectivist values were less likely to trust opinion leaders who were independent of the group since they regarded self-interest as a priority (Lukes, 1971). Also, opinion leaders in Taiwan are less likely to be affected by censorship and show a more pluralist inclination toward the zero-COVID policy, which leads to less alignment between them and collectivists.

Individualist issue interpretation and higher levels of political/social trust

Consistent with our expectation, this study indicated a positive correlation between individualist issue interpretation and trust in key opinion leaders in two Chinese societies. When people adopted an individualist issue framing of the pandemic, they presented a higher level of trust in KOLs. This finding is consistent with previous studies revealing that individualists would autonomously present a higher level of social trust (Realo et al., 2008).

However, a positive association between individualist value and trust in government was revealed, which was inconsistent with our expectations and previous studies that suggested individualism to be the barrier to trust (Huang and Van de Vliert, 2006). We further conducted a post-hoc analysis to specify this relationship between two societies. Results indicated that individualist issue interpretation was negatively correlated with trust in government in Mainland China (β = −0.05, p < 0.001), which is congruent with the hypothesis. However, individualist issue interpretation was positively correlated with trust in government in Taiwan (β = 0.15, p < 0.001).

This may be due to the characteristics of individualism in Taiwan. Chiou (2001) indicated that vertical individualism was more prevalent in Taiwan compared to other regions (e.g., Argentina). Distinguished from other types of individualism, vertical individualism emphasized the perception of disparity from self and others (Singelis et al., 1995), with which people sought to be the best through competition (Triandis and Gelfand, 1998). Thus, they may pay close attention to institutions and individuals who offer information and opinions to improve themselves (Choi and Kim, 2019). Under the pandemic, it is plausible that people with a strong sense of vertical individualism in Taiwan recognized the crucial role of government and opinion leaders, sought support from them, and enhanced themselves to resist the virus.

The moderating role of regions

Consistent with the hypotheses and the aforementioned post hoc analyses, this study suggested the differences lying in the two Chinese societies. Specifically, our findings indicated that the region positively moderated the relationship between people’s collectivist issue interpretation and their trust in the government and KOLs. Compared with people in Taiwan, the collectivist issue interpretation among people in Mainland China was more likely to influence their trust in entities.

This can be explained by the distinction of traditionalism and political systems in these two societies. Notably, Wong et al. (2011) have demonstrated the significant role of traditionalism in cultivating political trust among the public. Empirical studies have specifically compared Mainland China and Taiwan in terms of the influence of traditional culture on political trust (Shi, 2001), and discovered that in Taiwan, the performance of the government had a greater impact on political trust than traditional cultural values. Political trust in Mainland, on the other hand, was based on traditional cultural values, particularly the Chinese inclination toward hierarchical order and their collectivist identity (Shi, 2001). Hence, it is plausible to infer that the influence of collectivist issue interpretation on people’s trust in government and KOLs is greater in societies that praise traditional values than those do not. In addition, discrepancies in political systems may play a role in generating distinct political trust. Scholars have recognized that the political system may influence political trust in Chinese societies (Tang, 2005; Bjørnskov, 2007). Parallel to our results, previous studies have demonstrated a relatively stronger correlation between institutional confidence and trust in Mainland China compared with Taiwan (Steinhardt, 2012). China is a one-party state, while Taiwan is a young liberal democratic society. Therefore, it is reasonable to suppose that the effect of collectivist issue interpretation on people’s trust is more considerable in societies with a more authoritarian political system.

This study also demonstrated that region negatively moderated the relationship between people’s individualist issue interpretation and their trust in the government. Compared with people in Mainland China, the individualist issue interpretation among people in Taiwan was more likely to influence their trust in the government. For the individualist issue interpretation, it cannot be explained by the distinction of traditionalism in the two societies. A possible explanation lies in the difference in their strictness of preventive policies. Although both societies adopted the zero-COVID policy, policies in Mainland China were apparently stricter, with lockdowns and tightened controls in risky areas, than in Taiwan (South China Morning Post, 2022). People who interpreted the pandemic as an individualist issue were less likely to trust the government in societies with the very strict zero-COVID policy. Thus, the influence of individualist issue interpretation on people’s trust in government is greater in societies with less rigorous preventive policies during the COVID pandemic.

Overall, the region tends to be a contextual factor within the relationship among cultural values, trust, and policy acceptance. It includes various contextual indicators, such as cultural orientations, traditionalism, and the contemporary strictness of preventive policies in the regions. The influence of region depends on the joint effect of aforementioned indicators.

Different roles of trust in government and KOLs on policy acceptance

The current study revealed trust in government to be a significant predictor of acceptance of the zero-COVID policy among people in both societies. When people present a higher level of governmental trust, a more positive attitude toward the zero-COVID policy will be cultivated. This finding is consistent with previous studies that suggest trust in government will promote policy acceptance (Leland et al., 2021). It sheds light on the idea that under the COVID pandemic, the government serves as the center of public attention, symbolizing its unity and power (Lee, 1977); people would support governmental actions due to their sense of patriotism. Practically, enhancing public trust in government is beneficial to promote the acceptance of the zero-COVID policy, especially for people who developed a strong sense of collective identity.

Additionally, trust in key opinion leaders was a negative predictor of people’s acceptance of the zero-COVID policy in both societies, which is also consistent with our expectations. It is also worth noting that the effect of KOLs is smaller than the effect of government in most of the models presented above. Therefore, it is safe for us to draw the conclusion that KOLs, though in vocal opposition to the zero-COVID policy, wield less power than the government in both societies.

Generally, this study contributes to the current studies of cultural values, trust, and policy acceptance in four ways: firstly, the study examines the relationship between cultural values and policy acceptance, while reiterating the effect of “I-C” dimension in people’s support for preventive measures under the pandemic. Secondly, the study presents an integrated model combining cultural values, trust, and policy acceptance. The model offers new insights to understand how people’s policy attitudes can be co-created by both cultural values and trust, generating new mechanisms to account for the formation of policy acceptance. Thirdly, the study presents differentiated impacts of social and political trust on the acceptance of zero-COVID policies and provides new implications for studying the relationship between trust and policy acceptance. Fourthly, by involving two Chinese societies (i.e., Mainland China and Taiwan), the study suggests the influence of contextual factors (e.g., traditionalism, strictness of preventive policies) within the whole process. Practically, rather than emphasizing the role of opinion leaders on media platforms, governmental institutions, and policymakers should prioritize their own ability and care for the public to promote government trust from citizens. They should endeavor to build social identity among citizens in order to cultivate their trust in government, which would eventually promote their acceptance of the zero-COVID policy implemented by the government.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, in Mainland China, we used a non-probabilistic sample, although we attempted to enlarge the sample size and draw the sample based on the national parameters. Future studies may adopt probability sampling to replicate this study. Second, as a study that concerns the individualism–collectivism dichotomy, it is not sufficient to examine the framework in societies with a relatively higher level of collectivism. It should be noted that our research, despite exploring the cultural logic underlying the public support for zero-COVID policy, did not include other cultural factors apart from individualism–collectivism. Future studies should test a more integrated model in other societies. Third, in addition to mentioning the political impact on people’s policy compliance behaviors, future studies should investigate the effect of political systems. Fourth, given the differences between stringent control in Mainland China and the open policy of Taiwan, potential factors such as social norms and penalties for non-adherence to the norms may be analyzed in future studies. Finally, future studies should take into consideration possible confounders such as an individual’s experience of being infected during the pandemic.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to privacy concerns. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to cmhsaXU5LWNAbXkuY2l0eXUuZWR1Lmhr.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee of City University of Hong Kong (Ethics approval reference nos.: 4-2020-05-F, 17-2021-23-F; Date of approval: 4 June 2020, 3 March 2021). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Y-HH, JL, and RL: conceptualization. RL and YL: methodology, software, and visualization. YL: validation and data curation. RL: formal analysis. Y-HH: resources, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. RL, JL, and YL: writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The work was supported by City University of Hong Kong under Grant (nos: 9380119, 7005703, and 9610573).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1047486/full#supplementary-material

References

Algan, Y., Cohen, D., Davoine, E., Foucault, M., and Stantcheva, S. (2021). Trust in scientists in times of pandemic: panel evidence from 12 countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118:e2108576118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2108576118

Alotaibi, T. S., Alkhathlan, A. A., and Alzeer, S. S. (2019). Instagram shopping in Saudi Arabia: what influences consumer trust and purchase decisions. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 10, 605–613. doi: 10.14569/IJACSA.2019.0101181

Armaş, I., Cretu, R. Z., and Ionescu, R. (2017). Self-efficacy, stress, and locus of control: the psychology of earthquake risk perception in Bucharest, Romania. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 22, 71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.018

Atalay, S., and Solmazer, G. (2021). The relationship between cultural value orientations and the changes in mobility during the Covid-19 pandemic: a National-Level Analysis. Front. Psychol. 12:578190. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.578190

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 4, 359–373. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 248–287. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L

Bao, H.-W.-S., Cai, H., and Huang, Z. (2022). Discerning cultural shifts in China? Commentary on Hamamura et al. (2021). Am. Psychol. 77, 786–788. doi: 10.1037/amp0001013

BBC (2021). Coronavirus: how the pandemic has changed the world economy. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-51706225 (Accessed September 16, 2022).

BBC (2022). Covid: living with Covid plan will restore freedom, says Boris Johnson. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-60455943 (Accessed September 16, 2022).

Bedford, O., Huang, Y.-H. C., and Ito, K. (2021). An assessment of the relational orientation framework for Chinese societies: Scale development and Chinese relationalism. Psych. J. 10, 112–127. doi: 10.1002/pchj.403

Bjørnskov, C. (2007). Determinants of generalized trust: a cross-country comparison. Public Choice 130, 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11127-006-9069-1

Blind, P.K. (2007). "Building trust in government in the twenty-first century: review of literature and emerging issues" in 7th global forum on reinventing government building Trust in Government, (Vienna: UNDESA), 26–29.

Bok, S., Shum, J., Harvie, J., and Lee, M. (2021). We versus me: indirect conditional effects of collectivism on COVID-19 public policy hypocrisy. J. Entrepreneur. Public Policy 10, 379–401. doi: 10.1108/JEPP-05-2021-0060

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1, 185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301

Cao, J. (2009). The analysis of tendency of transition from collectivism to individualism in China. Cross Cultur. Commun. 5, 42–50. doi: 10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020090504.005

Chen, C.-H., Chiu, P.-J., Chih, Y.-C., and Yeh, G.-L. (2015). Determinants of influenza vaccination among young Taiwanese children. Vaccine 33, 1993–1998. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.032

Chen, C., Frey, C. B., and Presidente, G. (2021). Culture and contagion: individualism and compliance with COVID-19 policy. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 190, 191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.07.026

Cheung, G. W., and Chow, I. H.-S. (1999). Subcultures in greater China: a comparison of managerial values in the People's Republic of China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 16, 369–387. doi: 10.1023/A:1015412215053

Chiou, J.-S. (2001). Horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism among college students in the United States, Taiwan, and Argentina. J. Soc. Psychol. 141, 667–678. doi: 10.1080/00224540109600580

Choi, Y., and Kim, J. (2019). Influence of cultural orientations on electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social media. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 48, 292–313. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2019.1627388

CNN (2021). Here are 5 countries that are opening up and living with Covid. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/09/16/world/covid-countries-opening-up-cmd-intl/index.html (Accessed September 16, 2022).

Cook, T. E., and Gronke, P. (2005). The skeptical American: revisiting the meanings of trust in government and confidence in institutions. J. Polit. 67, 784–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00339.x

Courneya, K. S., and Bobick, T. M. (2000). Integrating the theory of planned behavior with the processes and stages of change in the exercise domain. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 1, 41–56. doi: 10.1016/S1469-0292(00)00006-6

Dai, Y., Huang, Y.-H. C., Jia, W., and Cai, Q. (2022). The paradoxical effects of institutional trust on risk perception and risk management in the Covid-19 pandemic: evidence from three societies. J. Risk Res. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2022.2108122

Earle, T. C. (2009). Trust, confidence, and the 2008 global financial crisis. Risk Analy. 29, 785–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01230.x

Ferle, C. L., Edwards, S. M., and Lee, W.-N. (2008). Culture, attitudes, and media patterns in China, Taiwan, and the U.S.: balancing standardization and localization decisions. J. Glob. Mark. 21, 191–205. doi: 10.1080/08911760802152017

Fiske, A. P. (1992). The four elementary forms of sociality: framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychol. Rev. 99, 689–723. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.99.4.689

Gecas, V. (1989). The social psychology of self-efficacy. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 15, 291–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.15.080189.001451

Hamamura, T., Chen, Z., Chan, C. S., Chen, S. X., and Kobayashi, T. (2021). Individualism with Chinese characteristics? Discerning cultural shifts in China using 50 years of printed texts. Am. Psychol. 76, 888–903. doi: 10.1037/amp0000840

Han, B., and Windsor, J. (2011). User's willingness to pay on social network sites. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 51, 31–40. doi: 10.1080/08874417.2011.11645499

Hartman, M. (2021). How We’ll Live With Covid After the Pandemic. Johns Hopkins University. Available at: https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2021/how-well-live-with-covid-after-the-pandemic (Accessed September 17, 2022).

Hayes, A.F. (2012). PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. [white paper]. Available at: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

Hayes, A.F. (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford publications

Head, T. C., and Sorensen, P. F. (1993). Cultural values and organizational development: a seven-country study. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 14, 3–7. doi: 10.1108/01437739310032656

Hofstede, G. (1993). The Cultural Relativity of Organizational Practices and Theories. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 14, 75–89. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490867

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., and Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: Mcgraw-hill.

Hogler, R., Henle, C., and Gross, M. (2013). Ethical behavior and regional environments: the effects of culture, values, and trust. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 25, 109–121. doi: 10.1007/s10672-013-9215-0

Huang, Y.-H. C., Ao, S., Lu, Y., Ip, C., and Kao, L. (2017). How trust and dialogue shape political participation in mainland China. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 11, 395–414. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2017.1368020

Huang, Y.-H. C., Bedford, O., and Zhang, Y. (2018). The relational orientation framework for examining culture in Chinese societies. Cult. Psychol. 24, 477–490. doi: 10.1177/1354067X17729362

Huang, X., and Van de Vliert, E. (2006). Job formalization and cultural individualism as barriers to Trust in Management. Int. J. Cross-cult. Manag. 6, 221–242. doi: 10.1177/1470595806066331

Huang, Y.-H. C., Wang, X., Fong, I. W.-Y., and Wu, Q. (2021). Examining the role of trust in regulators in food safety risk assessment: A cross-regional analysis of three Chinese societies using an integrative framework. SAGE Open. 11, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/21582440211061579

Huang, Y.-H. C., Wu, F., and Cheng, Y. (2016). Crisis communication in context: cultural and political influences underpinning Chinese public relations practice. Public Relat. Rev. 42, 201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.11.015

Huggins, C. M., and Debies-Carl, J. S. (2015). Tolerance in the City: the multilevel effects of urban environments on permissive attitudes. J. Urban Aff. 37, 255–269. doi: 10.1111/juaf.12141

Huynh, T. L. D. (2020). Does culture matter social distancing under the COVID-19 pandemic? Saf. Sci. 130, 104872–104872. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104872

Jäckle, S., Trüdinger, E.-M., Hildebrandt, A., and Wagschal, U. (2022). A matter of trust: how political and social trust relate to the acceptance of Covid-19 policies in Germany. German Politics, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2021.2021510

Jakubanecs, A., Supphellen, M., and Helgeson, J. G. (2018). Crisis management across borders: effects of a crisis event on consumer responses and communication strategies in Norway and Russia. J. East-West Bus. 24, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/10669868.2017.1381214

Johnson-George, C., and Swap, W. C. (1982). Measurement of specific interpersonal trust: construction and validation of a scale to assess trust in a specific other. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 43, 1306–1317. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.6.1306

Kelly, J. A., St Lawrence, J. S., Diaz, Y. E., Stevenson, L. Y., Hauth, A. C., Brasfield, T. L., et al. (1991). HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: an experimental analysis. Am. J. Public Health 81, 168–171. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.81.2.168

Kemmelmeier, M., Burnstein, E., Krumov, K., Genkova, P., Kanagawa, C., Hirshberg, M. S., et al. (2003). Individualism, collectivism, and authoritarianism in seven societies. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 34, 304–322. doi: 10.1177/0022022103034003005

Kemmelmeier, M., and Jami, W. A. (2021). Mask wearing as cultural behavior: an investigation across 45 U.S. states during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:648692. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648692

Klein, E., and Robison, J. (2020). Like, post, and distrust? How social media use affects Trust in Government. Polit. Commun. 37, 46–64. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2019.1661891

Lee, J. R. (1977). Rallying around the flag: foreign policy events and presidential popularity. Pres. Stud. Q. 7, 252–256.

Leland, S., Chattopadhyay, J., Maestas, C., and Piatak, J. (2021). Policy venue preference and relative trust in government in federal systems. Governance 34, 373–393. doi: 10.1111/gove.12501

Leonhardt, J. M., Pezzuti, T., and Namkoong, J.-E. (2020). We’re not so different: collectivism increases perceived homophily, trust, and seeking user-generated product information. J. Bus. Res. 112, 160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.017

Liu, R., Huang, Y.-H. C., Sun, J., Lau, J., and Cai, Q. (2022). A Shot in the arm for vaccination intention: The media and the health belief model in three Chinese societies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:3705. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063705

Liu, J., Zhang, Z., Qi, J., Wu, H., and Chen, M. (2019). Understanding the impact of opinion leaders’ characteristics on online group knowledge-sharing engagement from in-group and out-group perspectives: evidence from a Chinese online knowledge-sharing community. Sustain. For. 11:4461. doi: 10.3390/su11164461

Lu, J. G. (2022). Two large-scale global studies on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy over time: Culture, uncertainty avoidance, and vaccine side-effect concerns. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000320

Lyu, Y., Zhang, J., and Wang, Y. (2022). The impact of national values on the prevention and control of COVID-19: An empirical study. Front. Psychol. 13:901471. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.901471

Maaravi, Y., Levy, A., Gur, T., Confino, D., and Segal, S. (2021). “The tragedy of the commons”: how individualism and collectivism affected the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 9:627559. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.627559

Nikolaev, B., Boudreaux, C., and Salahodjaev, R. (2017). Are individualistic societies less equal? Evidence from the parasite stress theory of values. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 138, 30–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2017.04.001

Nisbet, M. C., and Kotcher, J. E. (2009). A two-step flow of influence?: opinion-leader campaigns on climate change. Sci. Commun. 30, 328–354. doi: 10.1177/1075547008328797

NPR (2021). The white house has a new plan for COVID-19 aimed at getting things back to normal. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2022/03/02/1083905865/the-white-house-has-a-new-plan-for-covid-19-aimed-at-getting-things-back-to-norm (Accessed September 16, 2022).

Oettingen, G. (1995). “Cross-cultural perspectives on self-efficacy” in Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies. ed. A. Bandura (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 149–176.

Otto, L. P., Lecheler, S., and Schuck, A. R. T. (2020). Is context the key? The (non-)differential effects of mediated incivility in three European countries. Polit. Commun. 37, 88–107. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2019.1663324

Oyserman, D., Sakamoto, I., and Lauffer, A. (1998). Cultural accommodation: hybridity and the framing of social obligation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 1606–1618. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1606

Parau, P., Lemnaru, C., Dinsoreanu, M., and Potolea, R. (2017). “Chapter 10—opinion leader detection” in Sentiment Analysis in Social Networks. eds. F. A. Pozzi, E. Fersini, E. Messina, and B. Liu (Boston: Morgan Kaufmann), 157–170.

Pathak, S., and Muralidharan, E. (2016). Informal institutions and their comparative influences on social and commercial entrepreneurship: the role of in-group collectivism and interpersonal trust. J. Small Bus. Manag. 54, 168–188. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12289

Pelham, B., Hardin, C., Murray, D., Shimizu, M., and Vandello, J. (2022). A truly global, non-WEIRD examination of collectivism: the global collectivism index (GCI). Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 3:100030. doi: 10.1016/j.cresp.2021.100030

Pitlik, H., and Rode, M. (2017). Individualistic values, institutional trust, and interventionist attitudes. J. Inst. Econ. 13, 575–598. doi: 10.1017/S1744137416000564

Prati, G., Pietrantoni, L., and Zani, B. (2011). Compliance with recommendations for pandemic influenza H1N1 2009: the role of trust and personal beliefs. Health Educ. Res. 26, 761–769. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr035

Putnam, R. (1993). The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life. American Prospect. 4, 35–42.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J. Democr. 6, 65–78. doi: 10.1353/jod.1995.0002

Realo, A., Allik, J., and Greenfield, B. (2008). Radius of trust: social capital in relation to familism and institutional collectivism. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 39, 447–462. doi: 10.1177/0022022108318096

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. Aust. J. Psychol. 91, 93–114. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803

Rubin, G. J., Amlôt, R., Page, L., and Wessely, S. (2009). Public perceptions, anxiety, and behaviour change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ 339:b2651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2651

Shah, D. V., and Scheufele, D. A. (2006). Explicating opinion leadership: nonpolitical dispositions, information consumption, and civic participation. Polit. Commun. 23, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/10584600500476932

Shi, T. (2001). Cultural values and political trust: a comparison of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan. Comp. Polit. 33, 401–419. doi: 10.2307/422441

Shi, T. (2014). “Cultural norms east and west” in The Cultural Logic of Politics in Mainland China and Taiwan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 41–59.

Shin, H. H., and Park, T. H. (2004). Individualism, collectivism and trust: the correlates between trust and cultural value orientations among Australian national public officers. Int. Rev. Public Administr. 9, 103–119. doi: 10.1080/12294659.2005.10805053

Sima, Y., and Pugsley, P. C. (2010). The rise of a'me culture'in postsocialist China: youth, individualism and identity creation in the blogosphere. Int. Commun. Gaz. 72, 287–306. doi: 10.1177/1748048509356952

Singelis, T. M., Triandis, H. C., Bhawuk, D. P., and Gelfand, M. J. (1995). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: a theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cult. Res. 29, 240–275. doi: 10.1177/106939719502900302

Smeekes, A., and Verkuyten, M. (2013). Collective self-continuity, group identification and in-group defense. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49, 984–994. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.06.004

South China Morning Post. (2022). Taiwan says it will not follow mainland China’s ‘cruel’ Covid lockdowns. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3176149/taiwan-says-it-will-not-follow-mainland-chinas-cruel-covid?module=perpetual_scroll_0&pgtype=article&campaign=3176149 (Accessed May 1, 2022).

Steele, L. G., and Lynch, S. M. (2013). The pursuit of happiness in China: individualism, collectivism, and subjective well-being during China’s economic and social transformation. Soc. Indic. Res. 114, 441–451. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0154-1

Steinhardt, H. C. (2012). How is high Trust in China Possible? Comparing the origins of generalized Trust in Three Chinese Societies. Politic. Stud. 60, 434–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00909.x

Stevens, H., and Haines, M. B. (2020). Trace together: pandemic response, democracy, and technology. East Asian Sci. Technol. Soc. 14, 523–532. doi: 10.1215/18752160-8698301

Tabellini, G. (2010). Culture and institutions: economic development in the regions of Europe. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 8, 677–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4774.2010.tb00537.x

Tang, W. (2005). Public Opinion and Political Change in China. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

The Economist (2022). China’s scientists are looking for a way out of the zero-covid policy. Available at: https://www.economist.com/china/2022/03/10/chinas-scientists-are-looking-for-a-way-out-of-the-zero-covid-policy (Accessed September 17, 2022).

The United Nations (2021). The SDG indicators. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/goal-08 (Accessed September 17, 2022).

Travaglino, G. A., and Moon, C. (2021). Compliance and self-reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-cultural study of trust and self-conscious emotions in the United States, Italy, and South Korea. Front. Psychol. 12:565845. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.565845

Triandis, H. C., and Gelfand, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 118–128. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.118

Triandis, H. C., McCusker, C., Betancourt, H., Iwao, S., Leung, K., Salazar, J. M., et al. (1993). An etic-emic analysis of individualism and collectivism. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 24, 366–383. doi: 10.1177/0022022193243006

Tsai, W.-H. (2021). “The Chinese Communist Party's control of online public opinion: toward networked authoritarianism,” in The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Studies. eds. C. Shei and W. Wei (London: Routledge), 493–504.

Uslaner, E. M., and Brown, M. (2005). Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. Am. Politics Res. 33, 868–894. doi: 10.1177/1532673X04271903

Voegel, J., and Wachsman, Y. (2022). The effect of culture in containing a pandemic: the case of COVID-19. J. Risk Res. 25, 1075–1084. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2021.1986566

Wang, X. (2021). The role of perceived susceptibility and collectivist values in support for using social distancing to prevent COVID-19 in the United States. J. Prevent. Health Promot. 2, 268–293. doi: 10.1177/26320770211015434

Wang, Y., Huang, Y.-H. C., and Cai, Q. (2022). Exploring the mediating role of government -public relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: A model comparison approach. Public Relat. Rev. 48:102231. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102231

Wartberg, L., Kammerl, R., Rosenkranz, M., Hirschhäuser, L., Hein, S., Schwinge, C., et al. (2014). The interdependence of family functioning and problematic internet use in a representative quota sample of adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 17, 14–18. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0494

WHO (2022). WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed October 10, 2022).

Wong, T. K.-Y., Wan, P.-S., and Hsiao, H.-H. M. (2011). The bases of political trust in six Asian societies: institutional and cultural explanations compared. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 32, 263–281. doi: 10.1177/0192512110378657

Xiao, W. S. (2021). The role of collectivism–individualism in attitudes toward compliance and psychological responses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:600826. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.600826

Xie, J. L., Roy, J. P., and Chen, Z. (2006). Cultural and individual differences in self-rating behavior: an extension and refinement of the cultural relativity hypothesis. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 341–364. doi: 10.1002/job.375

Xu, Y. (2020). Building trust across Borders? Exploring the trust-building process between the nonprofit organizations and the government in China. Front. Psychol. 11:582821. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.582821

Yu, Y., Lau, M., and Lau, J. T.-F. (2021). Positive association between individualism and vaccination resistance against COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese adults: mediations via perceived personal and societal benefits. Vaccine 9:1225. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9111225

Yuki, M. (2003). Intergroup comparison versus intragroup relationships: a cross-cultural examination of social identity theory in north American and east Asian cultural contexts. Soc. Psychol. Q. 66, 166–183. doi: 10.2307/1519846

Keywords: zero-COVID, collectivism, individualism, trust in government, trust in KOL, Chinese societies

Citation: Huang Y-HC, Li J, Liu R and Liu Y (2022) Go for zero tolerance: Cultural values, trust, and acceptance of zero-COVID policy in two Chinese societies. Front. Psychol. 13:1047486. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1047486

Edited by:

Xiaopeng Ren, Institute of Psychology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Wilson Hong, Institute for Tourism Studies, Macao SAR, ChinaVincenzo Auriemma, University of Salerno, Italy

Ravi Philip Rajkumar, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), India

Copyright © 2022 Huang, Li, Liu and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruoheng Liu, cmhsaXU5LWNAbXkuY2l0eXUuZWR1Lmhr

Yi-Hui Christine Huang

Yi-Hui Christine Huang Jun Li

Jun Li Ruoheng Liu

Ruoheng Liu Yinuo Liu

Yinuo Liu