94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 29 November 2022

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1018290

Introduction: This paper explores consumers’ coping strategies when they feel negative emotions due to forced deconsumption during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns.

Methods: The tool used for data collection is the questionnaire. It was made using the LimeSurvey software. A total of 621 complete observations were analyzed.

Results: The findings demonstrate that anger positively influences the activation of seeking social support, mental disengagement, and confrontive coping strategies. Besides, disappointment activates mental disengagement but only marginally confrontive coping and not behavioral disengagement. Furthermore, regret is positively related to confrontive coping, behavioral disengagement, acceptance, and positive reinterpretation. Finally, worry positively impacts behavioral disengagement, self-control, seeking social support, mental disengagement, and planful problem-solving.

Discussion: The study’s originality lies in its investigation of consumers’ coping strategies when experiencing negative emotions due to forced deconsumption in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.

At the end of 2019, the entire planet faced a crisis, first sanitary and then economic, called the Covid-19 pandemic. To curb the pandemic, government authorities worldwide have decreed health emergency measures such as lockdowns, widespread work stoppages, the closure of businesses selling non-essential goods and services, social distancing, or curfews (Mehrsafar et al., 2021; Warnock-Parkes et al., 2021).

These measures have led to a major upheaval in consumer consumption habits (Ivascu et al., 2022; Zhang and Li, 2022). Indeed, according to Colla (2020), except for fresh and natural products, the food sector has experienced considerable growth. In addition, the do-it-yourself (DIY), furniture and household appliances, electronics, video on demand (VOD), indoor games, home sports, and hygiene sectors experienced spectacular consumer success. On the other hand, sectors such as clothing and cosmetics have fallen sharply, leading to deconsumption (Colla, 2020). In addition, some well-established responsible consumption behaviors have also regressed, such as recycling, composting, sharing, or public transport (Trespeuch et al., 2020; Hansen et al., 2021).

Deconsumption may be defined from the consumer’s point of view as an individual’s behavior aimed at voluntarily reducing their consumption, at consuming less through the reduction of the sums spent, the reduction of the quantities consumed, or even the transfer of consumption. From certain products to others with better value for the consumer (de Lanauze and Siadou-Martin, 2013). But deconsumption, when forced, as in the context of the pandemic, can lead to negative consumer resentment.

In fact, this upheaval in consumption habits observed in individuals has generated various emotions, especially a “relative negative feeling of being less happy” (Martinelli et al., 2021, p. 18). In fact, “when lockdown measures were taken […] public response was marked with negative emotions” (Rodas et al., 2022, p. 323). In addition, to Garnefski and Kraaij (2006, 2018), these include, for example, anger, anxiety, depression, or stress. Therefore, how did consumers adapt to forced deconsumption during the Covid-19 crisis?

The rich theoretical framework on consumers’ adaptation to adverse events, also called “coping” (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Yi and Baumgartner, 2004; Duhachek, 2005; Gelbrich, 2009), can be advantageous in answering correctly to that critical question. Several studies, such as Yi and Baumgartner (2004) or Duhachek (2005), and Gelbrich (2009), studied the relationship between specific emotions and the activation of coping strategies. Given that Yi and Baumgartner’s (2004) research investigates how consumers manage stressful, emotional experiences in purchase-related situations, we shall retain this work as the theoretical framework of this study.

Consequently, this study answers the abovementioned question. It contributes fundamentally to the literature since it explores the coping strategies of consumers when they feel negative emotions related to forced deconsumption in a pandemic context and crisis context in general. The study also has practical, managerial, clinical, and applied importance, especially since the number of pandemics might potentially increase in the future, especially with climate change (Seo, 2021). These results enable managers and decision-makers to better anticipate consumer reactions and adjust their strategies and policies appropriately.

Our overall research objective is, therefore, to identify the different strategies that consumers have adopted in the context of the crisis to adapt to the upheaval in their consumption habits, and above all, to the forced deconsumption of specific goods and services.

To achieve this objective, we asked ourselves some specific research questions, namely:

1. How do consumers adapt to the anger felt following the forced deconsumption induced by the Covid-19 pandemic context?

2. How do consumers deal with disappointment after the forced deconsumption observed during the Covid-19 pandemic?

3. Faced with the regret felt following the involuntary consumption caused by the pandemic context of Covid-19, how do consumers adapt?

4. How do consumers adapt to the worry felt following the involuntary consumption caused by the context of the Covid-19 crisis?

The paper starts with a literature review on coping (Section “Literature review”) before presenting the theoretical and conceptual framework of the research (Section “Theoretical background and conceptual framework”). Then follow the research methodology (Section “Methodology”), the data analysis and results (Section “Analysis and results”), and the discussion of the results (Section “Discussion of the results”). Sections “Theoretical implications” and “Managerial implications” outline the implications for theory and practice, respectively. Section “Limitations and future research avenues” underscores the limitations of the research and their corresponding avenues for future research, while section 10 wraps up the paper with a short conclusion.

Yi and Baumgartner (2004) studied the adaptation of consumers to four negative emotions felt in a problematic purchasing situation: anger, regret, disappointment, and fear. Eight adaptation strategies emerge. Indeed, the consumer can get angry in front of a rude service provider. And to deal with anger, he can resort to confrontation (the consumer openly displays his dissatisfaction, defends his point of view, and tries to change the mind of the other party, the service provider, for example) or mental disengagement (the consumer moves on and avoids thinking about the situation). The consumer who feels disappointed because the products purchased do not live up to his expectations resorts to confrontation, mental disengagement, or behavioral disengagement (the consumer refuses any additional effort in the direction of the stressful situation). The consumer who feels he has made the wrong product choice and feels regret resorts to acceptance (the consumer accepts the unfavorable situation) or positive reinterpretation (the consumer finds a valid reason for the unfavorable situation and draws positive lessons). And finally, the consumer who is worried about the undesirable consequences linked to the purchase and consumption of a product resorts to the planned resolution of the problem (the consumer thinks about what can be done to manage the stressful situation, develops a plan of action, then takes the necessary steps to resolve the problem); seeking social support (the consumer seeks to discuss his feelings with a loved one in order to obtain comfort); self-control (consumers control and master their negative emotions) or even mental disengagement.

The interaction of negative emotions (fear and anger), coping strategies (acting out anger and psychological distance), and perceptions of information technology are examined by Zheng and Montargot (2022). The findings show that employees’ negative emotions (anger and fear) significantly and negatively affect how they perceive implementing a new reservation system by using coping strategies (i.e., venting anger and psychological distancing). Additionally, employees’ attitudes about using a cutting-edge reservation system positively impact their intention to do so.

Kwon and Kwak (2022) claim that the global COVID-19 pandemic drove the majority of sports leagues to postpone games in March and April 2020, leaving sports enthusiasts without any matches to watch. Their research investigated how sports fans assess stress and participate in coping strategies due to the global pandemic-related sports lockout. The findings demonstrated that anger, aggressiveness, and the desire for affiliation raised threat perceptions toward the COVID-19 lockout, which in turn had a substantial impact on coping strategies that were emotion-focused and disengaging.

The research by Bae (2022) investigated whether people’s coping strategies and the reasons they utilize social media serve as mediators between real COVID-19-related stress and the belief that doing so can be alleviated. The results revealed that the active coping strategies used by those experiencing COVID-19-related stress were more likely to be linked to informational and social interaction demands, leading people to attribute stress relief to social media use. Those under pressure were inspired to seek social engagement through the expressive support coping technique, which led people to believe that using social media to relax during the pandemic. By enabling people to lose themselves in social media activities and ignore negative thoughts related to the pandemic, emotional venting and avoidance coping strategies substantially influenced escape, social contact, and amusement seeking.

The paper of Kemp et al. (2021) attempts to investigate the distinctive emotional distress felt during the COVID-19 pandemic. It examines the function of fear and anxiety, what caused it, and how those emotions affected consumption as well as compliant and conformist behaviors. According to both exploratory and empirical studies, ruminative thoughts are positively correlated with fears and anxieties, but trust in leadership is inversely correlated with these emotions. Furthermore, large-scale purchases made following recommendations to stop the virus from spreading and regulate negative emotions via consumption were similarly linked to sentiments of fear and anxiety.

Satish et al. (2021) examined the Covid-19 pandemic-related changes in consumer behavior and purchasing patterns. Consumer stockpiling as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic has its own repercussions. The paper suggests that “minimalism in consumption” is crucial to preventing consumer greed. According to the study, customers’ buying habits will change if lockdowns are used in the future or during any other crisis. However, because they worry about the scarcity of necessities, consumers now have a hoarding mindset.

Nath et al. (2022) compared the consumers of India and Bangladesh and identified the existence of two emotion-based coping strategies, namely religiosity and social support. The authors further claimed that the COVID-19 pandemic strongly affected consumers’ general well-being. However, little is known about how the COVID-19 condition impacts consumer well-being and how subsistence consumers manage special tensions and well-being-related worries. The results show that subsistence consumers faced particular stressors and hardships during COVID-19, including unanticipated temporary financial difficulty, psychosocial stress, and stress connected to the market and consumption.

The study by Park et al. (2022) classified consumer groups based on their perceived negative emotions (i.e., anxiety, fear, depression, anger, and boredom). Four groups—anxiety, depression, anger, and indifference—were developed by clustering analysis. The study next looked at how each emotional group differs in its impact on the shopping-related motives (such as mood improvement, enjoyment of the shopping experience, socializing seeking, and self-control wanting) and actions (i.e., shopping for high-priced goods and buying bulk goods). The findings showed that all emotional groups had an impact on intentions for expensive buying as well as socializing seeking. However, depression and indifference are linked favorably to the need for social interaction and affect plans to buy in bulk. In addition, emotions other than anxiety impact mood enhancement and high-priced purchase intentions. Finally, anger influences intentions for bulk purchases and is linked to self-control striving.

Further, a study by Wang et al. (2017) highlighted that a negative encounter with a product or service disengages consumers, leaving the situation as an avoidance-focused coping strategy. Incongruity in emotions due to purchasing some faulty product leads to conflict in the minds of consumers, where they cogitate about whether they need the product, which in turn leads to negative behavior (Powers et al., 2019). In these situations, consumers regret and feel their responsibility toward purchase without careful consideration (Chan et al., 2017).

Moreover, in his study to better the theorization of coping strategies, Duhachek (2005) establishes links between eight coping strategies (active coping, rational thinking, positive thinking, emotional discharge, instrumental support, social support, avoidance, and denial) and some emotions related to the feeling of threat (fear, worry, threat, anxiety) and anger (anger and frustration). These include the link between negative emotions of threat and avoidance strategies, the link between threat and social support; but also, and the link between the threat and the active strategies (active adaptation, positive thinking, rational thinking).

Also, Gelbrich (2009) establishes a link between anger and the search for social support on the one hand and between anger and confrontation on the other hand. However, beyond this non-exhaustive list of studies on coping strategies and negative emotions, no previous (a priori) study has looked at consumers’ coping strategies when they experience negative emotions due to forced consumption in the context of a pandemic. The study by Cole et al. (2017) also insisted that a consumer may try to find some social support from his peers to arrive at emotional well-being if he receives a faulty product. But on the other hand, a study by Kim and Florack (2020) indicated that frequent social interactions could not provide stress relief during COVID-19, increasing emotional instability and triggering impulse buying. Authors further suggested that frequent interactions increased psychological emotions like fear and worry, affecting consumer behavior. Yuen et al. (2020) found an absence of knowledge during the pandemic as one of the factors that motivated them to shop more, feel secure, and relieve stress.

From the previous studies, it is evident that there is a semi-consensus on the importance of consumers’ coping strategies when they feel negative emotions in the face of forced deconsumption during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns.

According to Delelis et al. (2011), coping is part of a set of regulatory processes called affect regulation. Different approaches were proposed to explain that process, and among these different affect regulation approaches, the most popular and the subject of the most attention is Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) regulation of stress or coping (Nicchi and Le Scanff, 2005). To them, the concept of stress regulation equates coping and refers to the process of managing negative emotions. More specifically, it uses various strategies to control or dissipate the stress caused by an unwelcome event. Consequently, Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) conception will be retained for the remainder of this study. Besides, this study relates coping strategies to specific negative emotions, which corresponds to the research problem of this study: to explore the management of negative emotions under forced deconsumption.

Following Lazarus and Folkman (1984), coping is defined as “the dynamic use of cognitive and behavioral efforts to respond to external and internal demands assessed as exhausting or exceeding personal resources” (Nicchi and Le Scanff, 2005, p. 97). In other words, coping is an organized set of cognitive and behavioral efforts (strategies) that people make to anticipate and detect potential stressors or to manage (for example, prevent, minimize or control) the demand arising from transactions between themselves and their environment. The following sub-section delves deeper into those strategies.

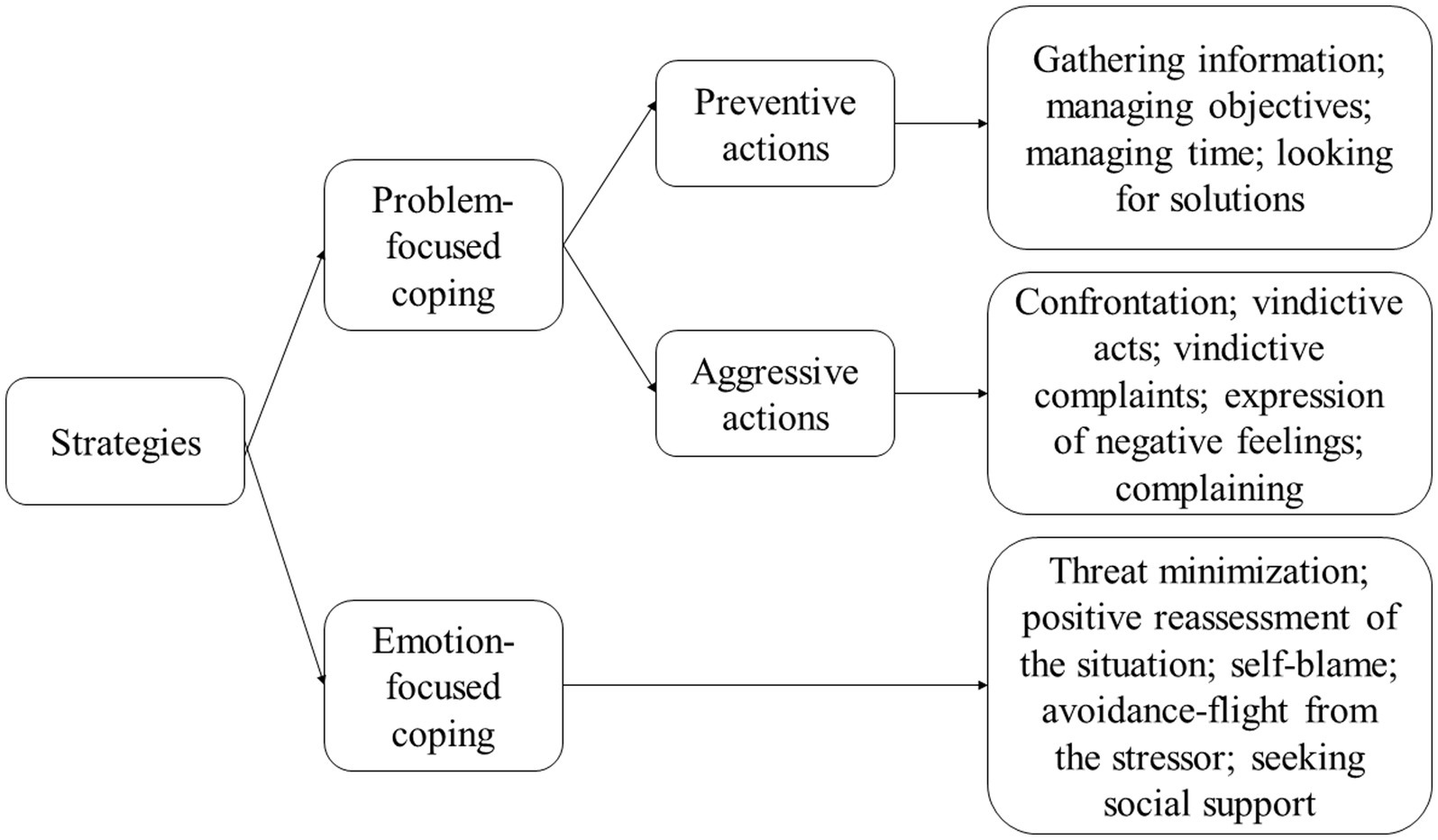

Coping strategies vary by author, but the most influential typology is the one developed by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) and Nicchi and Le Scanff (2005), which can either be problem-centered strategies or emotion-centered ones.

Problem-focused strategies involve efforts to manage or lessen the difficulty at the source of the stress. We distinguish, on the one hand, the preventive actions, which relate to the anticipation of the action and, therefore, to the reduction of the threat (gathering information, managing objectives, managing time, looking for solutions), and on the other, aggressive actions (confrontation; vindictive acts; vindictive complaints; expression of negative feelings; complaining), which eliminate or reduce the source of an existing difficulty.

Problem-focused strategies reduce the gap between the state of person-environment transactions and the desired (or hoped-for) state of these transactions. Furthermore, reducing this gap will curb the stress caused (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Nicchi and Le Scanff, 2005).

Emotion-focused strategies (emotional management) are used when it is impossible to eliminate stress and involve regulating negative emotions resulting from the stressor. They do not impact the person-environment relationship but contribute to the individual’s well-being. These strategies involve predominantly physiological techniques, such as relaxation or cognitive efforts to change the meaning of the problem and reduce the threat (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Nicchi and Le Scanff, 2005). These five strategies centered on emotions, namely:

• Threat minimization: this technique gives little or no importance to the danger reflected in the stressful situation. For example, those who were called “conspiracy theorists” during the pandemic supported the position that the Covid-19 pandemic did not exist or was not as bad as announced in the media: the pandemic was more of a “plandemic” (Eberl et al., 2021). These individuals were reluctant to take barrier gestures or wear masks and, therefore, certainly experienced less stress.

• The positive reassessment of the situation consists of positively reinterpreting the situation with which one is confronted to dissipate the negative emotion one feels. For example, some observers (researchers, decision-makers, journalists, etc.) sought to positively reinterpret the pandemic as an opportunity to shift towards more sustainability and more responsible consumption (Trespeuch et al., 2021).

• Self-blame: recognizing one’s share of responsibility in a situation to forgive oneself and forget the situation and the stress that goes with it. Example: Gaétan buys a damaged product. He resolves not to go back to change it because he considers it his fault that he was not vigilant.

• Avoidance-flight from the stressor: fleeing or avoiding the stressor. For example, in front of impolite and aggressive agents enforcing mask-wearing and social distancing measures, a person is deterred from going to public places and prefers to stay home.

• Seeking social support: complaining about the situation to others in order to get their support. For example, a person who struggles with social distancing and lockdowns might find comfort and support in verbalizing his/her feelings to understand others.

Figure 1 summarizes the types of coping strategies according to Lazarus and Folkman (1984).

Figure 1. Coping strategies. Drawn using source data from Lazarus and Folkman (1984).

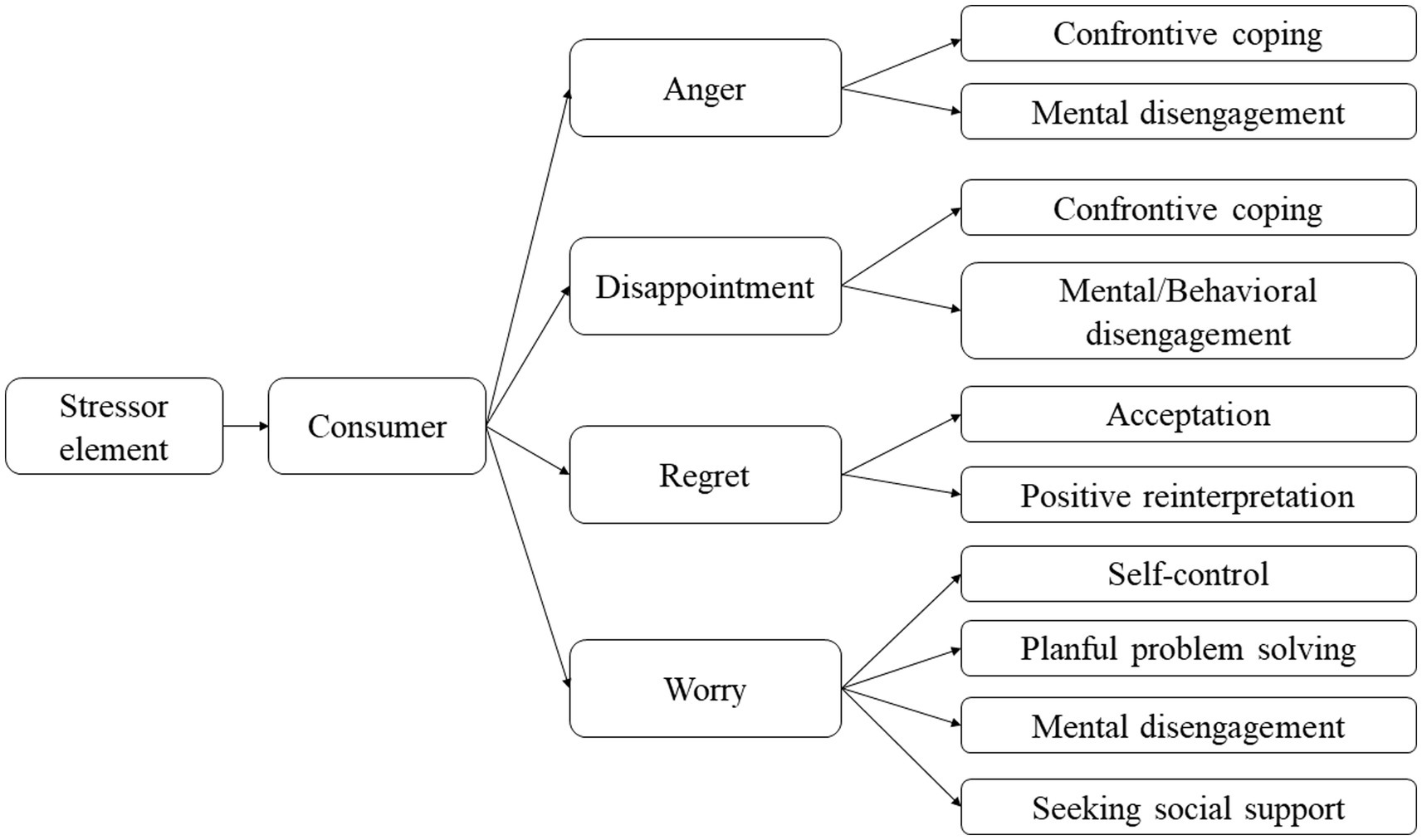

Several authors have studied coping strategies in consumption settings. Notably, Yi and Baumgartner (2004) identified eight strategies for managing negative emotions (i.e., anger, regret, worry, and disappointment) caused by destabilizing circumstances or events for the consumer. These are: “planned problem solving,”; “confrontation, “; “seeking of social support,”; “mental disengagement,”; “behavioral disengagement,”; “positive reinterpretation,”; “self-control,” and “acceptance of the problem.”

Indeed, when blame is assigned to another party and the situation is seen as changeable, as in the case of anger and disappointment, confrontation (the most important strategy in problem-based management and the least important in emotion-based management) is the most used. If the confrontation fails, the consumer uses mental disengagement.

When expectations are not met due to some circumstance (i.e., results-related disappointment), mental or behavioral disengagement, which is relatively unfocused on issues and emotions, is the most common coping strategy.

When consumers blame themselves for making the wrong choice and, therefore, experience regret, they tend to cope using acceptance and positive reinterpretation, which are less problem-focused and, therefore, more emotion-focused.

Finally, in cases of worry due to the prospect of future undesirable consequences, consumers refer to planned problem-solving, seeking social support, self-control, and mental disengagement.

The following diagram by Figure 2 summarizes the consumer’s strategies in a difficult situation and with negative emotions.

Figure 2. Consumers’ coping strategies. Drawn using source data from Yi and Baumgartner (2004).

To Yi and Baumgartner (2004), consumers activate confrontation and mental disengagement strategies when they experience the emotion of anger. Duhachek (2005) abounds in the same direction and affirms that the emotion of anger, accompanied by a strong impression of effectiveness, leads to the adoption of active coping strategies (coping through action, rational thinking, and positive thinking) or expressive support (emotional relief, instrumental support, and emotional support). However, the emotion of anger associated with the impression of a low-efficiency level can lead to using these same strategies if the emotion of anger is very strong. Also, according to Duhachek (2005), the impression of a very low level of efficacy can lead angry consumers to adopt avoidance strategies (denial, avoidance). Gelbrich (2009) adds that anger associated with a low level of helplessness reinforces the activation of the strategy of vindictive complaint (act of confrontation) or seeking support (vindictive word of mouth) if the level of helplessness is high. Seeking social support could be an additional strategy for mental and behavioral disengagement. Therefore:

H1a: The emotion of anger has a positive influence on the activation of confrontive coping.

H1b: The emotion of anger has a positive influence on the activation of the mental disengagement strategy.

H1c: The emotion of anger has a positive influence on the activation of seeking social support.

Furthermore, according to Yi and Baumgartner (2004), disappointed consumers resort to confrontation, which is somewhat similar to the case of anger. And when the attempted confrontation strategies fail, consumers may resort to mental and behavioral disengagement. This leads us to postulate the following set of hypotheses:

H2a: The emotion of disappointment positively influences the activation of confrontive coping.

H2b: The emotion of disappointment positively influences the activation of the mental disengagement strategy.

H2c: The emotion of disappointment positively influences the activation of the behavioral disengagement strategy.

Moreover, the consumer who feels regret feels guilty for having transgressed his principles, standards, or values (Izard, 1977). This shows a complementarity between the emotion of regret and the emotion of guilt. Kubany and Watson (2003) demonstrate that the consumer who feels guilt engages in a positive reinterpretation of the events that led him to this feeling. Yi and Baumgartner (2004) validate the hypothesis that the consumer who feels regret tends to get over it by using acceptance and positive reinterpretation. Mattila and Ro (2008) claim that consumers who experience regret also employ confrontational strategies (direct complaint). However, for Le and Ho (2020), consumers who experience regret do not indulge in an immediate complaint; instead, they choose between either negative word-of-mouth or behavioral disengagement (they prefer to ignore the incident). Based on these developments, we build this other set of four hypotheses, namely:

H3a: The emotion of regret has a positive influence on the adoption of the confrontation strategy.

H3b: The emotion of regret has a positive influence on the adoption of the acceptance strategy.

H3c: The emotion of regret positively influences the adoption of the positive reinterpretation strategy.

H3d: The emotion of regret positively influences the adoption of the behavioral disengagement strategy.

In addition, for Yi and Baumgartner (2004), consumer refers to planned problem solving, seeking social support, self-control, and mental disengagement when experiencing worry. Moreover, Mercanti-Guérin (2008) thinks that worry can push the consumer to adopt a posture of avoidance and withdrawal with regard to the frightening situation, which relates to behavioral disengagement. Consequently, we decide to test the following hypotheses:

H4a: The emotion of worry positively influences self-control.

H4b: The emotion of worry positively influences mental disengagement.

H4c: The emotion of worry positively influences the activation of a planful problem-solving strategy.

H4d: The emotion of worry positively influences the activation of the social support seeking strategy.

H4e: The emotion of worry positively influences the activation of the search strategy of behavioral Disengagement.

The diagram in Figure 3 represents the conceptual model under study.

To ensure that our study meets all the ethical standards for research involving humans, we submitted our research project for approval to a university ethics certification committee. Our project has therefore been certified as compliant with ethical standards for research with human beings, and a certificate [no. 2021-554] has been awarded to us for this matter.

The data was collected by a survey questionnaire programmed with the LimeSurvey software. We used 5-point Likert scales (“1 = totally disagree,” “2 = Rather disagree,” “3 = Indifferent,” “4 = Rather agree,” and “5 = totally agree”) as instruments for gauging participants’ responses to each survey item.

The questionnaire items are adapted from the measurement scale of eight coping strategies used in unpleasant buying situations by Yi and Baumgartner (2004). Table 1 shows the original items by Yi and Baumgartner (2004) and their adaptation to the current study.

Additional questions measure the level of emotions felt by the respondents. Negative emotions were not the subject of an experimental protocol in our study but were exclusively inspired by Yi and Baumgartner (2004), who had already done preliminary work on the four emotions (anger, disappointment, regret, worry) felt by consumers in difficult buying situations. Therefore:

• I feel angry that I have to buy less stuff.

• I feel disappointed that I have to buy less stuff.

• I feel regret because I have to buy less stuff.

• I feel worried because I have to buy less stuff.

Finally, we added sociodemographic gender questions, including sex, age, gender, occupational status, marital status, and annual income.

When establishing the appropriate sample size, several factors must be considered, including the anticipated analytics. In our case, we plan to use factor analysis and structural equation modeling. We thus used a combination of approaches and techniques in order to triangulate for optimal sample size. First, a rule of thumb suggests at least ten respondents for questionnaire item, that is, a 10:1 ratio of respondents to item (Nunnally, 1978). Since we had 43 items except for five sociodemographic questions, this would have meant at least 430 respondents (or 480 with all survey questions included). Second, we turn to the literature that suggests a sample size independent of the number of measurement items. Usually, for factor analysis, a range of 200 to 300 observations is appropriate (Comrey, 1988; Guadagnoli and Velicer, 1988), but at least 300 to 450 is necessary to identify acceptable levels of comparability of patterns, while replication is necessary for sample sizes that are below 300 (Guadagnoli and Velicer, 1988). This is also in line with Clark and Watson’s (2016) suggestion of at least 300 observations after pre-test. Since a larger sample size is always better as it ensure more stable factor loadings, generalizable results, replicable factors and lower measurement errors (Comrey and Lee, 2013), we use Comrey and Lee’s (1992) graded scale (100 = poor; 200 = fair; 300 = good; 500 = very good; ≥ 1,000 = excellent). Although specific to scale measurement purposes, this scale provides numerical reference points to ensure a proper sample size. Since a sample above 500 respondents is deemed “very good,” and larger is always better for multivariate analysis (Osborne and Costello, 2004), we set the appropriate sample size at around 600 respondents.

North American consumers aged 18 and over were recruited online on the Mturk platform. Despite its non-random sampling frame, MTurk has several desirable features: an integrated system of remuneration for participants, a large pool of participants, a simplified study design process, recruitment of participants, and data collection (Buhrmester et al., 2016). Besides, according to Buhrmester et al. (2016), compared to standard Internet samples, there is a slightly better demographic diversification of the MTurk respondents, speed in the recruitment process, lower cost of recruitment, and a collection of quality data. Within 1 month, we recruited 632 respondents, with 621 complete and 11 partial responses.

The project has obtained a certificate of ethics [CER-2021-554] issued by the ethics committee from the university with which the authors are affiliated. Once recruited, the participants read an introduction to the study, which states the certificate of ethics, and then presents the research team and the study background and objectives. This section explains in detail that the Government has implemented several measures to curb the spread of the coronavirus. Some economic sectors (e.g., catering, events, tourism, sport/recreation) have been declared “non-essential” and have had to close their doors since December 25, 2020, or as early as September 28, 2020. As a consumer, this forces them to buy less than before by limiting themselves to “essential” goods and services (as defined by the Government’s “priority shopping list”). The text further states that the purpose of the study is to analyze how participants have dealt with these changes in their consumption patterns. Additional information was then provided to the respondents regarding the procedure (including the estimated completion time of 10 min), the risks and benefits of participating in the study, and different matters pertaining to confidentiality, retention of data, compensation, voluntary participation, and right of withdrawal of the study, and the responsibility of the principal investigator. The participants then provided their informed consent to participate in the study by ticking “yes” or “no.” Participants are then redirected to the questionnaire with mandatory fill-ins for all 48 questions. Since the survey was only for participants aged 18 and over, a screener question ensured that the participant was at least 18 years old. The questions relating to the emotion came first and were then followed by those on the coping strategies employed. After responding to the questions, a thank you page appeared on the screen and informed the participants that the survey was now over.

The data was checked for quality and adequacy before applying statistical tools. Then, various preliminary statistical tests were applied to derive the results. First, the missing data were substituted with arithmetic mean, as suggested by Byrne (2013) and Shashi and Singh (2015). Further, the data were checked to detect the existence of common method bias (CMB). To this end, Harman’s single-factor test was performed (Harman, 1976). This procedure involves “constraining all the scale items into a single unrotated factor in exploratory factor analysis, with the assumption that the presence of CMB is indicated by the emergence of either a single factor or a general factor accounting for the majority of covariance among measures” (Podsakoff et al., 2003, p. 889). The recommended value is not more than 50% of the explained variance for the single-factor solution (Harman, 1976). The results indicated 32.25% for a single factor variance below the recommended value indicating that CMB is not present.

Table 2 presents the demographic profile of the sample. Of all the respondents, 64.73% were males, and 35.27% were females. The annual income of most of the respondents ranged between 50,000$–79,999$ (35.43%) and 20,000$–49,999$ (32.85). Undergraduates (45.57%) dominated the sample, followed by graduates holding a Master’s degree (21.90%) and a Professional degree (13.37%). The vast majority of respondents were full-time employees (79.87%) and aged 25 to 44 (72.8%).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed to assess the reliability and validity of the data and confirm the theoretically grounded model reflecting postulated relationships between exogenous and endogenous constructs, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed (Mueller and Hancock, 2001, p. 5240). To estimate the convergent validity, the standardized loadings of the constructs and the average variances extracted (AVEs) were considered (Hair et al., 2011). Standardized loadings of 0.6 or higher suggest that items exhibit validity (Kline, 2005). AVE values above 0.5 indicate adequate convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Bagozzi et al., 1991). Internal consistency (i.e., reliability) was addressed by computing composite reliability (CR). 0.7 signals an acceptable internal consistency (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Castagna et al., 2020).

Table 3 shows the measurement model results. A few scale items, such as RP4 for Planful problem solving, DM2 and DM4 for Mental Disengagement, RPOS3 for Positive Interpretation, MDS1 for Self-control, as well as ACC2 and ACC3 for Acceptance were removed due to low factor loadings. The standardized item loadings lay between 0.600 and 0.824, thus exceeding the recommended minimum value of 0.60 (Kline, 2005; Hair et al., 2011). The critical ratio values of all the scale items were above 1.96, suggesting a normal data distribution (Byrne, 2013). These results indicate the existence of convergent validity. Composite reliabilities (CRs) of the variables lay between 0.711–0.89 and are above the recommended value of 0.7, reflecting good internal consistency of the factors. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of each construct was above the recommended value of 0.5 and lay between 0.507–0.656, indicating that all constructs exhibit convergent validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

Discriminant validity was measured by calculating the AVE’s square root, which ranges between 0.712 and 0.809 (see the diagonal values in Table 4). All these values were above the inter-item correlations (see the off-diagonal values in Table 4), meeting the discriminant validity criteria (Hair et al., 2011).

After ascertaining the satisfactory factor structure, the proposed hypotheses positing relationships between dependent and independent variables were tested using structural equation modeling (SEM). Table 5 provides the results of the structural model. Model fit indices indicated a good model fit (CMIN/df = 4.22, GFI = 0.985, NFI = 0.989, CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.960, IFI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.071).

The impact of anger was empirically validated on confrontive coping, mental disengagement, and seeking social support. Seeking social support was the most strongly impacted by anger (β = 0.184, p ≤ 0.001), followed by mental disengagement (β = 0.177, p ≤ 0.001). Confrontive coping (β = 0.142, p ≤ 0.001), though significant, was less influenced by anger than mental disengagement and seeking social support. Collectively, these results lend support to H1a–c.

Disappointment significantly influenced mental disengagement (β = 0.156, p = 0.001), supporting H2b. This indicates that disappointed consumers tend to escape from the situation and try to forget the situation of forced deconsumption. Surprisingly, the emotion of disappointment had only a marginal impact on confrontive coping (β = 0.060, p = 0.087) and did not significantly impact behavioral disengagement (β = 0.033, p = 0.375), so H2a and H2c are not supported.

The impact of regret was assessed on confrontative coping, acceptance, positive reinterpretation, and behavioral disengagement. Regret strongly influenced confrontive coping (β = 0.199, p ≤ 0.001) and behavioral disengagement (β = 0.177, p ≤ 0.001), thus supporting H3a and H3d. Regret also influenced acceptance (β = 0.140, p ≤ 0.001). Albeit significant, positive reinterpretation was the least impacted by regret (β = 0.101, p = 0.004) compared to other coping strategies. These results collectively support H3b and H3c.

The effect of worry was estimated on self-control, mental disengagement, planful problem-solving, seeking social support, and behavioral disengagement. Among all, behavioral disengagement (β = 0.400, p = 0.000) and self-control (β = 0.391, p ≤ 0.001) were the most impacted by worry. Furthermore, seeking social support (β = 0.315, p ≤ 0.001), mental disengagement (β = 0.261, p ≤ 0.001), and planful problem-solving (β = 0.243, p ≤ 0.001) were also significantly influenced by the emotion of worry. Therefore, H4a–e are supported.

Coping strategies are derived from work on reaction to stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984) and, as such, are highly relevant to the study of the consumers’ responses to the key stressors of the Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdowns. Using Yi and Baumgartner’s (2004) theoretical framework on coping strategies under difficult purchasing situations, this research investigates consumers’ coping strategies when they feel negative emotions in the face of forced deconsumption during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns. In fact, Yi and Baumgartner’s (2004) study findings are continually used as a framework of reference to draw connections between coping mechanisms and negative emotions in the circumstances involving purchases (Jun and Yeo, 2012; Zheng and Montargot, 2022).

The results of Zheng and Montargot (2022) show how critical it is to consider unfavorable feelings while adopting IT innovations. Additionally, the model created in this study supports that, compared to a valence-based approach, an appraisal tendency approach better defines the circumstances in which various emotions are activated to anticipate and explain how emotions connect to IT usage through adaption actions. Kwon and Kwak (2022) offer factual proof of how sports fans react to the pandemic-related sports lockdown and deal with the unusual circumstances. By classifying consumers according to their psychological tendencies, it may be possible to anticipate which sports fans would participate in coping strategies. According to Bae (2022), communicators can better understand how users can encourage people to cope with stress by providing people with more effective social media, which will lead to stress reduction and improved well-being by understanding how stress-induced coping strategies influence people’s specific motivations and reduce users’ stress levels. The study of Kemp et al. (2021) sheds fresh light on what causes fear and anxiety during pandemics and explores how these emotions affect consumption as well as conformity and compliance behaviors. According to Satish et al. (2021), a situational impact of the pandemic has been a sharp shift in consumer behavior. Each crisis has a unique impact on consumer behavior. In this study, Covid-19 was taken into account when analyzing fear, greed, and anxiety. On the other hand, the research aims to make reasonable inferences based on customers’ experiences during the lockdown. Based on the data of Nath et al. (2022) study, which is based on the appraisal theory of stress, reveals that religion and social support, two emotion-focused coping strategies, coexist in India and Bangladesh and work together to help people overcome their worries about their well-being. The severe effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on customers who are socioeconomically subsistence may thus be of special importance to managers and policymakers. In pandemic scenarios like the present COVID-19 issue, the study of Park et al. (2022) helps practitioners and academics better understand how individuals manage their negative emotions by engaging in retail therapy.

The results demonstrate that anger positively influences the activation of seeking social support, mental disengagement, and confrontive coping, and this finding is in sync with the previous study by Stone et al. (2003). That angry customers mainly seek social support in the face of anger underscores the generic importance of social ties and relationships in the wake of crises (Hobfoll et al., 1986; Stone et al., 2003). Mental disengagement’s secondary importance could be explained by the fact that this strategy may appear after consumers’ original outpouring of anger dissipates or after the situation becomes unchangeable. Interestingly and counter-intuitively, confrontive coping, which places a higher emphasis on (aggressive) problem-solving than on emotions (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), was the last coping mechanism employed by customers to control their anger. This can be explicable by the specific nature of the Covid-19 crisis, during which consumers were confined at home and could not easily confront those they deemed responsible for the situation. On the other hand, they could communicate well with other people. In fact, Internet communications boomed during that period (Abir et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2021), hence the relative prevalence of seeking social support over confrontation.

Second, the results underline that the emotion of disappointment has a milder effect on coping strategies. These results contradict the previous studies by Duhachek (2005) and Gelbrich (2009), where disappointed consumers restrain themselves from any purchase. In contrast to angry consumers who resort to a broader range of coping strategies, disappointed ones tend to recourse exclusively to mental disengagement. Although the impact on confrontive coping was marginally significant, a parallel between mental disengagement and confrontive coping can be drawn. More specifically, the observation that disappointment might occasionally be person-related could trigger confrontational coping (see van Dijk et al., 2019). In fact, although the issue may be context-based (e.g., government decrees and stores adapting to new regulations), consumers who are disappointed have a strong tendency to hold another party (such as the marketer) accountable for the fact that their expectations were not met, even when the exchange partner was not directly at fault for the issue (Yi and Baumgartner, 2004). This can be because consumerism has pushed people to stand up for their rights when confronted with a poor product or service experience (Khalil et al., 2021).

Additionally, dissatisfaction and mental disengagement are linked. For example, when consumers blamed the disconfirmation on impersonal circumstances (i.e., when the disappointment was result-related) and believed that nothing could be done to remedy the situation, dissatisfied customers may use mental disengagement (Jung and Park, 2018). Future studies should make a clearer distinction between the two types of disappointment, especially in light of how differently they affect coping mechanisms.

Third, similarly to anger, the emotion of regret arising from forced deconsumption due to the Covid-19 pandemic activates a broad range of coping strategies. These include, respectively, confrontive coping, behavioral disengagement, acceptance, and positive reinterpretation. Acceptance and positive reinterpretation were utilized by customers who felt remorse in dealing with their emotional condition. Both coping mechanisms place a strong emphasis on emotions over problems. However, in contrast to Yi and Baumgartner’s (2004) findings, the lower impact of regret on both strategies indicates that regretful customers are slightly less likely to make an effort to regulate or alter their feelings as well as adjust to the circumstance in the case of forced deconsumption due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Instead, confrontive coping and behavioral disengagement were more prevalent, which could be explained by consumers’ longing for how things were before the pandemic outbreak, before the mandates, and before the lockdowns. Gittings et al. (2021) underscore this by emphasizing how consumers felt that their lives got “stuck” (p. 947) during the lockdowns. In fact, many found it preferable to “get back to normal” (NHS, 2021) instead of going further into the “new normal” (Emanuel et al., 2022, pp. 211–212).

Fourth, the findings show that worry positively influences, by order of importance, behavioral disengagement, self-control, seeking social support, mental disengagement, and planful problem-solving. As predicted by Yi and Baumgartner’s (2004) framework, worry produced the broadest range of coping mechanisms compared to the other emotions. Consumers who experienced anxiety disengaged behaviorally, exercised self-control, sought social support, disengaged mentally, and solved problems planfully. Worry is a response to the possibility of an unfavorable future with little control and predictability. Consequently, a rational, problem-focused approach seems inappropriate for dealing with such emotion. Instead, worried consumers seem to predominantly recourse to emotion-based coping approaches such as avoidance-flight from the stressor and self-mastery, according to Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) typology. More specifically, they adjust to the circumstance and regulate the feeling via behavioral detachment – and, to a lesser extent, mental disengagement - and self-control. Yet, as underscored by Yi and Baumgartner (2004), despite unpredictability, the results further show that worry also entails problem-based strategies, especially seeking social support and planful problem-solving.

This study contributes to the literature by exploring how consumers cope with four negative emotions from forced deconsumption amid the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak and ensuing lockdowns. As such, it contributes to advancing the literature on consumer adaptation and coping strategies.

It has been argued so far in the literature (e.g., Yi and Baumgartner, 2004; Duhachek, 2005) that in the event of confrontation and social support failure, angry consumers adopt disengagement (avoidance) strategies. We have demonstrated that in the specific context of lockdowns, angry consumers – due to their inability to access their leaders and go out of their homes - resort slightly more to social support seeking and avoidance through mental disengagement than to confrontational strategies.

Furthermore, past research (e.g., Yi and Baumgartner, 2004; Mattila and Ro, 2008) suggested that when feeling disappointed, consumers can adopt confrontative strategies, avoidance, and, albeit more marginally, seeking social support. This study indicates that consumers disappointed by forced deconsumption in a crisis context preferred avoidance strategies and mental disengagement. The lack of impact on either confrontation or behavioral disengagement can be related to the absence of access to authorities and, syllogistically, the incapacity to avoid them.

Kubany and Watson (2003) suggest that consumers who feel regret adopt positive reinterpretation strategies. Similarly, Yi and Baumgartner (2004) argue that in the event of regret, consumers use positive reinterpretation and acceptance strategies. As for Mattila and Ro (2008), in the event of regret, the consumer can use confrontation to search for social support. If those strategies all fail, the regretful consumer may decide to simply ignore the incident, so he behaviorally disengages from it (Le and Ho, 2020). Our study has shown that while disappointment does not produce confrontive coping, and anger activates that strategy but slightly less automatically than others, regret is the most conducive to confrontation (cf. Mattila and Ro, 2008) and behavioral disengagement. Nostalgic feelings which create retro perspectives (Hallegatte et al., 2018) by thinking about the days before the pandemic (and how better they were for some people [Gittings et al., 2021]) appear as a stronger drive for aggressive problem-based coping than disappointment or even anger. The study also confirms the emergence of acceptance and positive reinterpretation, in line with past research (e.g., Kubany and Watson, 2003; Yi and Baumgartner, 2004).

In the event of worry, consumers may activate several active strategies (planned resolution and social support) and emotion-focused strategies (mental disengagement and self-control; Yi and Baumgartner, 2004). To Mercanti-Guérin (2008), consumers tend to adopt a posture of avoidance and withdrawal regarding the frightening situation. Our study specifies and complements Mercanti-Guérin’s (2008) work in that, overall, avoidance is predominant in the form of behavioral disengagement. In line with Yi and Baumgartner (2004), this strategy is followed by self-control, and both are emotion-focused strategies, while other strategies are more problem-focused (i.e., seeking social support and planful problem solving).

This research draws on Yi and Baumgartner’s (2004) study as the theoretical framework in this paper. However, since their study investigates how consumers cope with stressful, emotional experiences in generic purchase-related situations, their results remain general and a priori inapplicable to extreme consumption events such as forced deconsumption induced by the Covid-19 pandemic. In fact, while confrontive coping appeared to be the most prominent when feeling anger and disappointment (Yi and Baumgartner, 2004), in our study, this strategy came only third after social support seeking and mental disengagement for anger and did not even constitute an outcome of disappointment. This absence of immediate confrontive coping in response to anger or disappointment may be due to the fact that in contrast to conventional purchase situations where consumers may attribute the issue related to the negative emotion to another person, the responsibility for Covid-19-related policies and measures (e.g., obligation to purchase essential products and services) did not only involve a single individual (e.g., employee, franchisee) or specific retails chains or brands, but rather numerous agents, including municipal authorities, provincial and federal/national governments, and even supranational entities (e.g., WHO). This is also manifest in mental disengagement - a strategy appearing second after an anger outburst [anger] or when the situation seems unchangeable [disappointment] (Yi and Baumgartner, 2004).

However, while regret generated two emotion-based strategies, such as acceptance and positive reinterpretation in Yi and Baumgartner (2004), our study showed that this emotion triggers aggressive problem-based coping through confrontive strategies and behavioral disengagement. In sum, nostalgic feelings of regret seem more conducive to aggressive problem-based coping and, to a lesser extent, acceptance and positive reinterpretation, possibly when the situation appears unchangeable.

Finally, we concur with Yi and Baumgartner (2004) that worry generates the most diverse assortment of coping strategies. Yet, those found by Yi and Baumgartner (2004) slightly differ from ours. Behavioral disengagement appeared first, although Yi and Baumgartner (2004) identified this as a non-viable strategy because worry concerns the prospect of undesirable future events. In our case, behavioral disengagement with a merchant might have consisted in using online commerce, which notably boomed during that period since access to stores for non-essential goods was forbidden. However, although not necessarily in the same order, our study matches Yi and Baumgartner’s (2004) in that the following strategies consisted mainly of self-control, seeking social support and planful problem-solving.

Under extreme situations such as forced deconsumption due to the Covid-19-related lockdowns and closure of non-essential businesses, consumers who experience anger and/or regret are the most likely to resort to direct confrontation with whomever they deem responsible for the situation, including retailers and business owners. They are more reluctant, less collaborative, and engage in attitudes of persuasion and retaliation. Hence, they require particular attention. The desire to deal with the restrictive situation means that this type of consumer would likely collaborate if they are made aware and supported. According to Bonifield and Cole (2007), recovery efforts that attenuate anger decrease consumer retaliatory attitudes. Therefore, we recommend that marketers, producers, and business leaders complement their conventional products and/or services with additional or complementary ones daringly. For example, two products for one, small gifts (e.g., pens) and notably products that specifically answer the consumer’s needs during the crisis), or even a thank-you note underscoring the retailer’s gratitude to the consumer for supporting local businesses. These may constitute forms of recovery to make up for the situation. Also, resistant products over time should be offered to facilitate long-term use and therefore reduce the purchase and excessive consumption of goods. Angry and worried consumers will seek social support, and hence human presence, be they clerks, store managers, and overall staff, will act as reassuring reference points for them. It will be necessary for employees to be good ambassadors of the brand in that process. Worried customers, in particular, will necessitate assistance in jugulating their emotions as they resort primarily to emotion-based strategies. Although disappointed consumers are least likely to activate a broad array of coping strategies, and if they do, they will seek to disengage from the situation mentally, managers may still be able to assist those consumers while also caring for angry and worried consumers as well. Conducting “business as usual” and displaying minimal references to the crisis is particularly suitable.

Although conducted to the best of our abilities, this study is not without limitations. It investigates four negative emotion variables without using control variables to check whether consumers felt other emotions. In addition, although the context of the pandemic had a strong effect, the emotions felt by consumers may be linked to other factors such as the virus, unemployment, bankruptcy, indebtment, lockdown, and so on, but this has not been controlled for in this study. Additional studies might therefore investigate the effect of such variables and of other unrelated variables by using them as control variables, for example. Besides, future research could explore additional emotions using Duhachek’s (2005) typology (e.g., fear, worry, threat, anxiety, anger, and frustration) and control for specific adverse outcomes of the lockdowns for respondents. Moreover, since the study relies on self-reported data, doubts about emotions felt during lockdowns and forced deconsumption could have caused bias in the data collected. However, we are confident that a traumatic situation such as a quasi-worldwide lockdown is so exceptional and unprecedented that it marks individuals and imprints their memory. In fact, several researchers diagnosed the Covid-19 pandemic as a “traumatic stressor” (Bridgland et al., 2021), which even caused post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) symptomatology and various other psychological problems worldwide due to the psychological distress caused by the Covid-19 emergency (Alshehri et al., 2020; Forte et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020). Besides, the analytical design reinforces the robustness of the results by allowing the direct examination of negative emotion variables and their link with coping strategies. Another limitation of this study is that we did not use control for “internet purchase.” While it is clear that consumers have deconsumed by buying products in stores, they might have compensated for this forced deconsumption by shopping online. However, suppose we start from the premise that Internet shopping might dampen negative feelings. If the study design can still capture negative emotions and their significant effect on coping, then the design and related results are rather conservative and should increase trust in the findings. Additional studies using this variable as a control or as a group differentiator might nonetheless find possibly stronger effects among consumers who did not purchase online.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comité d’éthique de la recherche, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

ME and GQ devised the project, the main conceptual ideas, and the proof outline, collected the data, and conceived and planned the survey. GQ and SS performed the preliminary set of analyses. UT curated the data, performed the analysis, and reported the results. ME wrote the manuscript in consultation with UT, MS, and SS, and supervised and funded the project. MS reviewed the manuscript. SS formatted the manuscript with the help of ME. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research has benefitted from the Covid 2020–2021 supplement provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada and is related to another grant in consumption studies received by the first author (grant number 430-2018-00415).

The authors are thankful for the support provided by the IT department of the University of Quebec at Chicoutimi for survey programming. They are also grateful for the exceptional support offered by the institution to researchers in enabling them to continue their research projects during the Covid-19 lockdowns.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abir, T., Osuagwu, U. L., Nur-A Yazdani, D. M., Mamun, A. A., Kakon, K., Salamah, A. A., et al. (2021). Internet use impact on physical health during COVID-19 lockdown in Bangladesh: a web-based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:10728. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010728

Alshehri, F. S., Alatawi, Y., Alghamdi, B. S., Alhifany, A. A., and Alharbi, A. (2020). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 28, 1666–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.10.013

Bae, M. (2022). Coping strategies initiated by COVID-19-related stress, individuals' motives for social media use, and perceived stress reduction. Internet Res., Ahead-of-print. doi: 10.1108/INTR-05-2021-0269

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., and Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 36, 421–458. doi: 10.2307/2393203

Bonifield, C., and Cole, C. (2007). Affective responses to service failure: anger, regret, and retaliatory versus conciliatory responses. Mark. Lett. 18, 85–99. doi: 10.1007/s11002-006-9006-6

Bridgland, V. M., Moeck, E. K., Green, D. M., Swain, T. L., Nayda, D. M., Matson, L. A., et al. (2021). Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS One 16:e0240146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240146

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., and Gosling, S. D. (2016). “Amazon's mechanical turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data?” in Methodological Issues and Strategies in Clinical Research. ed. A. E. Kazdin (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 133–139.

Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. New York, NY: Routledge.

Castagna, F., Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., Oropallo, E., and Strazzullo, S. (2020). Assessing SMEs’ internationalisation strategies in action. Appl. Sci. 10:4743. doi: 10.3390/app10144743

Chan, T. K. H., Cheung, C. M. K., and Lee, Z. W. Y. (2017). “The state of online impulsebuying research: A literature analysis. Information & Management, 54, 207–217.

Clark, L. A., and Watson, D. (2016). “Constructing validity: basic issues in objective scale development,” in Methodological Issues and Strategies in Clinical Research. ed. A. E. Kazdin (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 187–203.

Cole, D. A., Nick, E. A., Zelkowitz, R. L., Roeder, K. M., and Spinelli, T. (2017). Online social support for young people: does it recapitulate in-person social support; can it help?. Computers in human Behavior, 68, 456–46.

Colla, E. (2020). L’impact du Covid-19 sur la consommation et l’achat pendant et après le confinement. ESCP Impact Paper No. IP2020-82-FR.

Comrey, A. L. (1988). Factor-analytic methods of scale development in personality and clinical psychology. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 56, 754–761. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.5.754

Comrey, A. L., and Lee, H. B. (1992). A First Course in Factor Analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

de Lanauze, G. S., and Siadou-Martin, B. (2013). Deconsumption practices and motivations: a theory of value approach. Revue Francaise de Gestion 230, 55–73. doi: 10.3166/RFG.230.55-73

Delelis, G., Christophe, V., Berjot, S., and Desombre, C. (2011). Are emotional regulation strategies and coping strategies linked? Bull. Psychol. 515, 471–479. doi: 10.3917/bupsy.515.0471

Duhachek, A. (2005). Coping: a multidimensional, hierarchical framework of responses to stressful consumption episodes. J. Consum. Res. 32, 41–53. doi: 10.1086/426612

Eberl, J. M., Huber, R. A., and Greussing, E. (2021). From populism to the “plandemic”: why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 31, 272–284. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2021.1924730

Emanuel, E. J., Osterholm, M., and Gounder, C. R. (2022). A national strategy for the “new normal” of life with Covid. JAMA 327, 211–212. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24282

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18, 382–388. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313

Forte, G., Favieri, F., Tambelli, R., and Casagrande, M. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic in the Italian population: validation of a post-traumatic stress disorder questionnaire and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:4151. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114151

Garnefski, N., and Kraaij, V. (2006). Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: a comparative study of five specific samples. Personal. Individ. Differ. 40, 1659–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.009

Garnefski, N., and Kraaij, V. (2018). Specificity of relations between adolescents' cognitive emotion regulation strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Cognit. Emot. 32, 1401–1408. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1232698

Gelbrich, K. (2009). Beyond just being dissatisfied: how angry and helpless customers react to failures when using self-service technologies. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 61, 40–59. doi: 10.1007/BF03396779

Gittings, L., Toska, E., Medley, S., Cluver, L., Logie, C. H., Ralayo, N., et al. (2021). ‘Now my life is stuck!’: experiences of adolescents and young people during COVID-19 lockdown in South Africa. Glob. Public Health 16, 947–963. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1899262

Guadagnoli, E., and Velicer, W. F. (1988). Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol. Bull. 103, 265–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.265

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hallegatte, D., Ertz, M., and Marticotte, F. (2018). Blending the past and present in a retro branded music concert: the impact of nostalgia proneness. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 27, 484–497. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-08-2017-1546

Hansen, N. C., Treider, J. M. G., Swarbrick, D., Bamford, J. S., Wilson, J., and Vuoskoski, J. K. (2021). A crowd-sourced database of coronamusic: documenting online making and sharing of music during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:684083. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.684083

Hobfoll, S. E., Nadler, A., and Leiberman, J. (1986). Satisfaction with social support during crisis: intimacy and self-esteem as critical determinants. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 296–304. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.2.296

Ivascu, L., Domil, A. E., Artene, A. E., Bogdan, O., Burcă, V., and Pavel, C. (2022). Psychological and behavior changes of consumer preferences during COVID-19 pandemic times: an application of GLM regression model. Front. Psychol. 13:879368. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879368

Izard, C. E. (1977). “Differential emotions theory” in Human Emotions (Boston, MA: Springer), 43–66.

Jun, S., and Yeo, J. (2012). Coping with negative emotions from buying mobile phones: a study of Korean consumers. J. Fam. Econ. Iss. 33, 167–176. doi: 10.1007/s10834-012-9311-6

Jung, Y., and Park, J. (2018). An investigation of relationships among privacy concerns, affective responses, and coping behaviors in location-based services. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 43, 15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.05.007

Kim, H., and Florack, A. (2020). Preparing for a crisis: examining the influence of fear and anxiety on consumption and compliance. PsyArXiv Preprints. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/sg5vx

Kemp, E., Bui, M. M., and Porter, M. III (2021). Preparing for a crisis: examining the influence of fear and anxiety on consumption and compliance. J. Consum. Mark. 38, 282–292. doi: 10.1108/JCM-05-2020-3841

Khalil, S., Ismail, A., and Ghalwash, S. (2021). The rise of sustainable consumerism: evidence from the Egyptian generation Z. Sustainability 13:13804. doi: 10.3390/su132413804

Kline, T. (2005). Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach to Design and Evaluation. London: Sage Publication

Kubany, E. S., and Watson, S. B. (2003). Guilt: elaboration of a multidimensional model. Psychol. Rec. 53, 51–90.

Kwon, Y., and Kwak, D. H. (2022). No games to watch: empirical analysis of sport fans’ stress and coping strategies during COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 23, 190–208. doi: 10.1108/IJSMS-02-2021-0053

Le, A. N. H., and Ho, H. X. (2020). The behavioral consequences of regret, anger, and frustration in service settings. J. Glob. Mark. 33, 84–102. doi: 10.1080/08911762.2019.1628330

Liang, L., Gao, T., Ren, H., Cao, R., Qin, Z., Hu, Y., et al. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder and psychological distress in Chinese youths following the COVID-19 emergency. J. Health Psychol. 25, 1164–1175. doi: 10.1177/1359105320937057

Martinelli, N., Gil, S., Belletier, C., Chevalère, J., Dezecache, G., Huguet, P., et al. (2021). Time and emotion during lockdown and the Covid-19 epidemic: determinants of our experience of time? Front. Psychol. 11:616169. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.616169

Mattila, A. S., and Ro, H. (2008). Discrete negative emotions and customer dissatisfaction responses in a casual restaurant setting. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 32, 89–107. doi: 10.1177/1096348007309570

Mehrsafar, A. H., Moghadam Zadeh, A., Gazerani, P., Jaenes Sanchez, J. C., Nejat, M., Rajabian Tabesh, M., et al. (2021). Mental health status, life satisfaction, and mood state of elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a follow-up study in the phases of home confinement, reopening, and semi-lockdown condition. Front. Psychol. 12:630414. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.630414

Mercanti-Guérin, M. (2008). Consumers' perception of the creativity of advertisements: development of a valid measurement scale. Recher. Applicat. Market. 23, 97–118. doi: 10.1177/205157070802300405

Mueller, R. O., and Hancock, G. R. (2001). “Factor analysis and latent structure: confirmatory factor analysis” in International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. eds. N. J. Smelser and P. B. Baltes (Oxford: Pergamon), 5239–5244.

Nath, S. D., Jamshed, K. M., and Shaikh, J. M. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on subsistence consumers' well-being and coping strategies: insights from India and Bangladesh. J. Consum. Aff. 56, 180–210. doi: 10.1111/joca.12440

NHS (2021). 11 tipes to cope with anxiety about getting “back to normal.” Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/every-mind-matters/coronavirus/tips-to-cope-with-anxiety-lockdown-lifting/

Nicchi, S., and Le Scanff, C. (2005). Les stratégies de faire face [Coping strategies]. Bull. Psychol. 475, 97–100. doi: 10.3917/bupsy.475.0097

Osborne, J. W., and Costello, A. B. (2004). Sample size and subject to item ratio in principal components analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 9, 1–9. doi: 10.7275/ktzq-jq66

Park, I., Lee, J., Lee, D., Lee, C., and Chung, W. Y. (2022). Changes in consumption patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic: analyzing the revenge spending motivations of different emotional groups. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 65:102874. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102874

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Powers, T. L., Jack, E. P., and Choi, S. (2019). Is Store or Service Satisfaction More Important to Customer Loyalty?. Marketing Management Journal, 29, 16–30.

Rodas, J. A., Jara-Rizzo, M. F., Greene, C. M., Moreta-Herrera, R., and Oleas, D. (2022). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychological distress during lockdown due to COVID-19. Int. J. Psychol. 57, 315–324. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12818

Satish, K., Venkatesh, A., and Manivannan, A. S. R. (2021). Covid-19 is driving fear and greed in consumer behavior and purchase pattern. South Asian J. Market. 2, 113–129. doi: 10.1108/SAJM-03-2021-0028

Seo, S. N. (2021). “A story of infectious diseases and pandemics: will climate change increase deadly viruses?” in Climate Change and Economics (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 187–202.

Shashi, S., and Singh, R. (2015). Modeling cold supply chain environment of organized farm products retailing in India. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 3, 197–212. doi: 10.5267/j.uscm.2015.4.004

Stone, H. W., Cross, D. R., Purvis, K. B., and Young, M. J. (2003). A study of the benefit of social and religious support on church members during times of crisis. Pastor. Psychol. 51, 327–340. doi: 10.1023/A:1022537400283

Trespeuch, L., Corne, A., Parguel, B., Kréziak, D., Robinot, É., Durif, F., et al. (2020). La pandémie va-t-elle (vraiment) changer nos habitudes? The Conversation 11:2020.

Trespeuch, L., Robinot, É., Botti, L., Bousquet, J., Corne, A., et al. (2021). Allons-nous vers une société plus responsable grâce à la pandémie de Covid-19? Nat. Sci. Soc. 29, 479–486. doi: 10.1051/nss/2022005

van Dijk, F. A., Schirmbeck, F., Boyette, L. L., and de Haan, L. (2019). Coping styles mediate the association between negative life events and subjective well-being in patients with non-affective psychotic disorders and their siblings. Psychiatry Res. 272, 296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.020

Wang, J., Li, Y., and Rao, H. R. (2017). Coping responses in phishing detection: an investigation of antecedents and consequences. Information Systems Research, 28:378–396.

Warnock-Parkes, E., Thew, G. R., and Clark, D. M. (2021). Belief in protecting others and social perceptions of face mask wearing were associated with frequent mask use in the early stages of the COVID pandemic in the UK. Front. Psychol. 12:680552. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680552

Wong, C. W., Tsai, A., Jonas, J. B., Ohno-Matsui, K., Chen, J., Ang, M., et al. (2021). Digital screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: risk for a further myopia boom? Am J. Ophthalmol. 223, 333–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.07.034

Yi, S., and Baumgartner, H. (2004). Coping with negative emotions in purchase-related situations. J. Consum. Psychol. 14, 303–317. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp1403_11

Yuen, K. F., Wang, X., Ma, F., and Li, K. X. (2020). The psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, 351

Zhang, N., and Li, J. (2022). Effect and mechanisms of state boredom on consumers’ livestreaming addiction. Front. Psychol. 13, –826121. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.826121

Keywords: deconsumption, COVID-19, coping, emotions, pandemic, lockdown, survey, questionnaire

Citation: Ertz M, Tandon U, Quenum GGY, Salem M and Sun S (2022) Consumers’ coping strategies when they feel negative emotions in the face of forced deconsumption during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns. Front. Psychol. 13:1018290. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1018290

Received: 05 September 2022; Accepted: 03 November 2022;

Published: 29 November 2022.

Edited by:

Dawei Wang, Shandong Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Kaihua Zhang, Shandong Normal University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Ertz, Tandon, Yao Quenum, Salem and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Myriam Ertz, TXlyaWFtX0VydHpAdXFhYy5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.