94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 21 December 2022

Sec. Performance Science

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1003053

This article is part of the Research Topic Athlete Psychological Resilience and Digital Mental Health Implementation View all 5 articles

We systematically reviewed resilience research in sport and exercise psychology. Sample included 92 studies comprising empirical qualitative and quantitative studies, mixed-method studies, review studies and conceptual/theoretical studies on psychological resilience in sports context. From the findings, we synthesized an evidence-based sport-specific definition and meta-model of “Sporting Resilience.” The review incorporates evidence from global culture contexts and evidence synthesized into the new definition and meta-model to achieve its aim. Conceptual detail and testability of the operational definition is provided. Sporting resilience provides a guiding framework for research and applied practice in a testable, objective manner. The new theoretical meta-model of resilience is derived from systematic evidence from sport psychology with theoretical considerations from positive and clinical psychology allowing generalizability. This original theory posits that there is a resilience filter comprised of biopsychosocial protective factors. The strength of this filter determines the impact of adversity and establishes the trajectory of positive adaptation. The findings of the review are used to discuss potential avenues of future research for psychological resilience in sports psychology.

Systematic review registration: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AFWRU.

Psychological resilience is the ability to withstand—and/or adapt—after an adversity. Psychological resilience has been studied in high-risk children and communities (Condly, 2006; Mancini and Bonanno, 2009) and among individuals after significant stress producing adversities such as childhood sexual abuse (Bogar and Hulse-Killacky, 2006), death of a parent (Greeff and Human, 2004), and terrorism (Bonanno et al., 2007). Resilience is often termed as “ordinary magic” (Masten, 2001, p. 227) because resilience in children can be developed by the correct combination of environments, relationships, and the chance to explore the world around with psychological safety (Masten, 2001).

Individuals who participate in sport actively engage with failure and adversity. Athletes experience failures, adversities, and stressors of different magnitudes in their careers (Mellalieu et al., 2009; Tamminen et al., 2013). Literature shows that athlete and non-athlete populations experience different stressors (Pritchard and Wilson, 2005), have different body image conceptualization (Hausenblas and Downs, 2001) and show differences in emotional intelligence and mental health (Bostani and Saiiari, 2011). Division 47 of the APA noted that “the sport context is a unique performance environment that requires specialized training beyond general performance principles… because of the unique culture of sport” (American Psychological Association, 2011, p. 14). Besides natural life stressors, athletes also experience obstacles such as injuries (Podlog and Eklund, 2006) and mental health issues (Papathomas and Lavallee, 2012) because of being in a highly evaluative environment with high impact positive and negative consequences associated with outcomes (see for review Sarkar and Fletcher, 2014).

Resilience has been implied as a functional necessity for success in sport because “the question is not if an athlete will encounter adversity in sport, but instead how will they respond when adversity occurs (Galli and Gonzalez, 2015, p. 1, italics as in original). Fletcher and Sarkar (2012) used grounded theory to study Olympic champions (experiences of adversity) and formulated the first sport-specific definition of psychological resilience: “the role of mental processes and behavior in promoting personal assets and protecting an individual from the potential negative effect of stressors” (p. 675).

Narrative reviews have outlined the stressors (e.g., performance standards, selection, funding, injury, media evaluations) and protective factors of psychological resilience (e.g., social support, environment, metacognitive appraisal) in sport performers (Sarkar and Fletcher, 2014) as well as implications for research and practice (see Galli and Gonzalez, 2015). Narrative reviews provide excellent evidence-based insight and a historical overview, but are difficult to replicate (Pae, 2015). In contrast, a systematic review adopts a structured, replicable method to search and analyse literature on a topic, providing insights into the empirical/theoretical advancements in an area (Hanley and Cutts, 2013).

A citation network analysis by Bicalho et al. (2020) indicated that there has been a rapid increase of publications on resilience between 2012 and 2018. A systematic review conducted in 2016 presented the definitions of resilience used in literature and the relationship of resilience with other psychological resources (see Bryan et al., 2019). Therefore, there is a need to review the resilience literature because previous narrative reviews preceded the expansion of publications. A systematic review categorizes and catalogs evidence across multiple studies to provide reliable findings with observable conclusions (Chandler et al., 2017, p. 5). This systematic review finds its rationale in an updated summary of the evidence base and future directions for research.

A review that summaries existing literature is crucial because previous evidence indicates that there are instances of ambiguous theorizing which hamper the understanding of resilience (Bryan et al., 2019). This imprecision creates simplistic “colloquialisms” in applied practice (p. 70). An updated systematic review of recent literature clarifies and guides future research. Researchers often conflate resilience or use it interchangeably with coping (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Rutter, 2012), mental toughness (Gucciardi et al., 2011), hardiness (Windle, 2011; Howe et al., 2012), and thriving (Brown et al., 2020). For instance, resilience is the process of adaptation post exposure to adversity/stressors (Luthar et al., 2000; Fletcher and Sarkar, 2012; Sarkar and Fletcher, 2013) whereas thriving is a value-added construct which describes the process of achieving a greater level of functioning in response to threat and risk (O'Leary and Ickovics, 1995).

Therefore, while resilience characterizes adaptive recovery (i.e., return to pre-adversity level of functioning by adaptation), thriving is value-added (i.e., exhibition of a superior level of functioning) (see Carver, 1998; Brown et al., 2020). Similarly, mental toughness, defined as “unshakeable perseverance and conviction toward some goal despite pressure or adversity” (Middleton et al., 2004, p. 1) is distinct from resilience. To illustrate, resilience in sport performers arises out of protective factors (see Sarkar and Fletcher, 2014). Resilient individuals can engage these protective factors to adapt successfully to adversity and stressors (Waaktaar and Torgerson, 2010; Windle, 2011; Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013); however, empirical evidence often strays from this operationalisation (Gucciardi et al., 2011). For example, Estrada et al. (2016) noted that 89% of the measures of resilience indirectly measuring antecedents, outcomes and/or covariates of resilience, not resilience itself. The current systematic review will (1) synthesize and summarize the growing evidence base to display which definitions of resilience studies are using, (2) appraise the definitions used to check whether they are supported by the empirical evidence, and (3) provide an operational definition of sporting resilience supported by the evidence from the systematic review.

Bryan et al. (2019) argued for defining resilience accurately using evidence from peer-reviewed research. Evidence-based definitions are essential to embrace sound scientific standards of research and rigorous applied practice (Moore, 2007; Winter and Collins, 2015). This article presents a systematic review of research that included resilience as a direct variable of investigation. We extend the conceptual ideation put forward by Den Hartigh et al. (2022) by using a systematic review method to isolate trends in the resilience in sport evidence base. There are four objectives of this study: first, we summarize the current empirical evidence base, and the definitions of resilience used. Second, we extract data from the empirical evidence to evaluate the definitions of resilience in sport for relevance. Third, we review the evidence to understand which empirical findings support which aspects of resilience theory. Four, reviewing theory present in literature against recent empirical evidence, we deliver a focused investigation into each component of resilience in the sporting context and develop the proposed meta-model.

This systematic review used Pluye and Hong (2014) and PRISMA (Moher et al., 2015) models for systematic reviews to best extract, appraise and synthesize data on resilience research in sport. This combination is replicated here because it has been used to systematically review sport psychology literature (cf. Gledhill et al., 2017; Bryan et al., 2018). This review was registered in the Open Science Framework for transparency, reproducibility and reduction of potential bias. All data related to the review and registration is available at (https://osf.io/afwru/?view_only=ab1ff15d3fff4bc18a96f6a011cfbe84). This review is integrative (collating different sources of data on resilience) and inductive (observations from analysis of existing research is appraised to come up with a general principle). We provide a synthesis of evidence of empirical, review and conceptual literature on resilience in sport.

Studies were selected in line with the inclusion criteria of: (a) original peer-reviewed articles; (b) book chapters because they are a valuable source of theoretical discourse; (c) full-text was obtainable; (d) examined psychological resilience at the individual level in sport contexts; (e) empirical studies that examined protective factors of psychological resilience or outcomes of being resilient in sport as a variable of investigation.

Studies that operationalized psychological resilience as stress-related growth and/or mental toughness and/or adversarial growth (see section above for resilience operationalization) were deemed ineligible to ensure clarity and a superior answer to the research question. Unpublished literature was excluded because they typically have no abstract and search markers to match against inclusion criteria (Benzies et al., 2006; Pappas and Williams, 2011). Review literature was included since they show conceptual development and inference of evidence into theory across the history of sport resilience research. Non-English literature was excluded due to lack of English translation resources; however, this exclusion does not constitute a limitation to the global nature of this systematic review because many non-Western countries have active English-publication scientific communities.

We conducted an initial scoping search from 1st to 5th November 2020 to check the feasibility of the review. A later search was conducted on May-June 2021. Final updated search was conducted from 20th December 2021 to 5th January 2022 using the strategy outlined below.

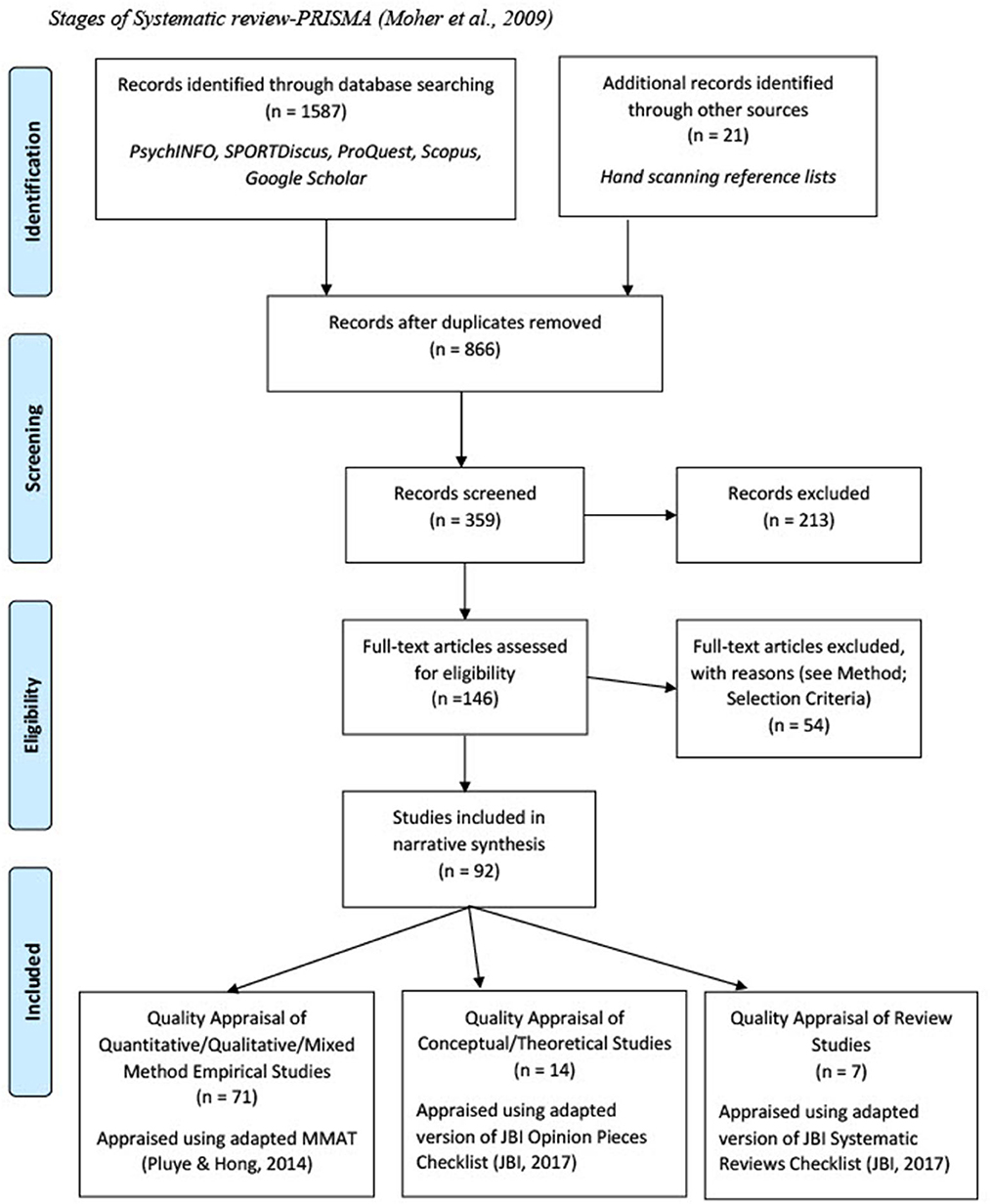

The search was conducted using the following integrated combination of keywords as Boolean operators to search for titles and keywords: Resil* AND athlete* AND Success; Resil* AND Sport; Resil* AND Coach; Resil* AND Sport*; Bounce* AND Back* AND Sport*; Resil* AND Player*. Electronic databases of PsychINFO, SPORTDiscus, ProQuest (Nursing and Allied Health Database; Sports Medicine and Education) and SCOPUS were searched. Further double-checking searches using paper titles and keywords using Google Scholar and ResearchGate was conducted to ensure relevant papers were not excluded. Reference sections of retained papers were hand-scanned to ensure thorough search of literature (Greenhalgh and Peacock, 2005). Authors were emailed to secure full texts if not available via libraries. A study was excluded if authors did not respond after three email contacts. No publication limit was set to capture all relevant evidence on resilience research in sport in line with the research question. In total, this search produced 1,598 studies (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stages of systematic review-PRISMA (Moher et al., 2015).

Searches were collated, noted, and traced manually using Microsoft Excel. De-duplication from databases was done in Excel and crosschecked using RefWorks. Assessment for inclusion was done in two levels. First, title and abstracts were screened against inclusion criteria (Level I). Where screening could not be undertaken by abstract alone, full-text was screened against inclusion criteria (Level II). The process is highlighted in the PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2015) (see Figure 1). The second author independently carried out the same search for rigor. Discrepancies were discussed and accepted/rejected according to eligibility criteria. Ten percent of the included articles were randomly selected for an independent third party peer review to confirm the rationale for including articles according to the pre-set criteria. The lead author rather the quality of method used in the study before reading results section to prevent bias while doing full-text analysis (Higgins et al., 2019). The second author reviewed a random selection of the quality appraisal to ensure rigor.

Data extraction from the selected studies was conducted using an extraction protocol which focused on (i) Conceptual/Theoretical framework of resilience; (ii) Operational definition of resilience used; (iii) Method with focus on design, sample (with demographics, sport type, sport level) and analysis procedures; (iv) Measures used to study resilience; (v) Results. Data extracted from included studies were manually recorded. This was then uploaded into a spreadsheet for quality appraisal and synthesis prior to transfer to tables during manuscript writing. Methodological quality for empirical studies was assessed using an adapted MMAT framework (Pluye et al., 2009; Pluye and Hong, 2014). For systematic reviews and conceptual papers/chapters, an adapted version of the JBI Systematic Review and Opinion Pieces checklist (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017) was used (see Appendix A). Total number of questions were converted to provide a percentile point of 100. “Yes” responses to each question gave an equal point weightage score. “No” responses equalled zero (see Appendix A for assessment tool). The second author extracted data using the protocol from a random selection of articles. If independently extracted data was discrepant. Authors reverted to the original article and discussed to clarity to achieve consensus.

A theoretical synthesis of findings was conducted following data extraction and quality appraisal replicating best practice guidance in systematic reviews (see cf. Pluye and Hong, 2014; Moher et al., 2015; Gledhill et al., 2017; Bryan et al., 2019). Theoretical synthesis process included: (a) Understanding resilience construct placement (i.e., whether resilience was viewed as a “trait” i.e., stable and difficult to change or “dynamic” i.e., malleable with conditions); (b) Theoretical orientation (i.e., theoretical frameworks used to understand resilience in selected studies); (c) Appraisal of empirical evidence to see which components of resilience construct and theory is supported/refuted. Meta-analysis was not conducted since data included multiple research designs.

The final sample comprised 92 studies. Seventy-one were empirical studies (quantitative = 54; qualitative = 13; mixed methods = 4), 12 were theoretical/conceptual studies and 7 were review studies. The overall quality appraisal score overall was high at 85.22%. Empirical studies scored at 83.03% (Quantitative = 76.59%; Qualitative = 98.66%; Mixed-Methods = 90%), theoretical/conceptual studies were scored at 98.66% and review studies were scored at 86.85% (see Appendix B).

The process of theoretical synthesis was conducted in two phases and is outlined to enable replication. In Phase 1, data (i.e., articles) were analyzed by clustering variables that were linked to resilience by frequency counts. For example, “Mastery”/“Sense of Control” was explored by 6 studies. In Phase II, the relevant studies exploring a variable of interest (e.g., “Mastery”/“Sense of Control”) was analyzed to infer whether the empirical evidence in those studies indicated that mastery was a key protective factor of resilience. If the empirical evidence indicated so, the variable was incorporated into the theoretical synthesis. The frequency count and empirical studies for each variable and/or characteristic of resilience is outlined in Tables 1, 2 for rigor and replicability.

Table 2. Definitional clarity and empirical evidence of components of “biopsychosocial protective filter” of sporting resilience.

Results of this systematic review provide fruitful insight into the definitional heterogeneity of resilience research in sport. We augment the preliminary findings of Bryan et al. (2019) by recognizing there are multiple definitions of resilience. Most definitions are “borrowed” from other fields of psychology and are not validated in the sport context. Among the included studies, 66 cited 25 guiding definitions of resilience. Nine outlined their own definition, 21 provided no operational definition (summarized in Appendix C). Multiple corresponding definitions were found. The definition by Fletcher and Sarkar (2012) is from the sport context but is restricted to Olympic champions and may not be ecologically valid. Few other definitions conceptually review sport as a setting (see Galli and Pagano, 2018; Hill et al., 2018a,b).

Bicalho et al. (2020) noted that 60% of studies on psychological resilience in sport since 2012 used Fletcher and Sarkar's (2012) definition. Results of our systematic review note that 22.8% of the included articles use this definition. Although this definition provides an excellent foundation, analysis indicates several areas where research can evolve to refine conceptual and methodological clarity. First, they operationalise resilience as psychological and note it to be “the role of mental processes and behavior in promoting personal assets and protecting an individual from the potential negative effect of stressors” (p. 675); however, resilience is a dynamic process which does not stop at protection from stressors, but encompasses positive adaptation (Luthar et al., 2000, p. 543; Luthar, 2006; Hill et al., 2018a; Gupta and McCarthy, 2021) not only from stressors/adversities but also from novel challenges in new situations, because if “circumstances change, resilience alters” (Rutter, 1981, p. 317). A major strength of the definition is the inclusion of mental processes and metacognitive components; however, it does not consider the developmental component of resilience because it is a capacity that develops over time in relation to the context of person-environment interactions (Egeland et al., 1993; see for definitional review Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013). Resilience exists on a continuum present to different degrees in different contexts (Pietrzak and Southwick, 2011), with specific influence of environmental and sociocultural contexts (Wagstaff et al., 2016).

Bryan et al. (2019) conducted a frequency word analysis on guiding definitions of resilience and noted that most definitions included three core concepts: adversity, positive adaptation, and bouncing-back/rebound and maintenance of wellbeing in line with Fletcher and Sarkar (2013). Synthesizing the frequency analysis of the most “prominent and frequent aspects of a multitude of definitions” (p. 77) they provided a definition stating resilience to be “a dynamic process encompassing the capacity to maintain regular functioning through diverse challenges or to rebound using facilitative resources” (p. 77). This definition is classifying resilience as a dynamic process, where individuals use resources to rebound after adversity (Sarkar and Fletcher, 2014). However, using a frequency word count of existing definitions to create another definition is not an empirically based conceptualization. This definition is synthesized from work and sport literature and is not tailored to the sport context. This point is crucial because resilience is best understood within domain-specific contexts (Luthar and Cicchetti, 2000; Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013). Since it is partially founded upon a work context, the definition does not account for the unique environmental configurations of the phenomenological reality of sport.

Hill et al. proposed a dynamical perspective of resilience in sports (Hill et al., 2018a) and a definition (Hill et al., 2018b) noting resilience to be “the dynamic process by which a biopsychosocial system returns to the previous level of functioning following a perturbation caused by a stressor” (p. 367). This “biopsychosocial system” is a conceptual advancement because the sports setting is a complex amalgam of physiological capacity, psychomotor skills, psychological elements, and social processes. They do not, however, provide an empirical backing to the conceptualization. Resilience is conceptualized as an outcome of withstanding perturbations and returning to a previous state. And this excludes positive adaptation capacity, which is a cornerstone of resilience operationalization distinguishing it from hardiness and/or mental toughness (see Gucciardi et al., 2008; Windle, 2011).

Clarity is crucial because “concepts are integral to every argument, for they address the most basic question of social science research: what are we talking about?” (Gerring, 2012, p. 112). We argue that the sport context is unique where athletes encounter multiple challenges/adversities simultaneously rather than in temporal isolation (Galli and Reel, 2012). Kiefer et al. (2018) also highlighted the importance of studying resilience as a situated, iterative-process driven by multiple variables whose influence is time-dependent and contextual. Therefore, operationalization of resilience needs to be contextually specific (cf. Luthar and Cicchetti, 2000; Fletcher and Sarkar, 2016; Wagstaff et al., 2016; Sarkar, 2017), founded upon empirical literature from sport psychology. The results of this systematic review provide the rationale to conceptualize a “sporting” i.e., sport-context specific model. The individual in the sporting context is not socially isolated, and therefore, by logical extension, nor is their resilience. Rather, because of their involvement in the sporting context, resilience is formed from and used to maintain positive equilibrium and/or adapt to a diverse range of sport-related stressors (see Fletcher and Sarkar, 2012; Gupta and McCarthy, 2021).

Keeping in mind the limitations of existing definitions and sourcing empirical evidence from this systematic review, we propose a definition of sporting resilience. The definition does not pull together broad descriptors but collates components which have found empirical support. We adhered to recommendations from literature to limit subjectivity (Gerring, 2012; Goertz and Mahoney, 2012).

Our definition outlines “Sporting resilience is a person's ability to evaluate what they think, feel and do when faced with an adversity which allows them to operate at their previous level and successfully adapt to persist.” Sporting resilience is learned as a process through interactions with the world (see Table 1 for components and evidence synthesis). Evidence indicates that sporting resilience is the environmentally adaptable, interaction dominant, dynamic-process trajectory that encompasses a sporting individual's metacognitive-emotional-behavioral capacities to maintain a positive equilibrium and successfully adapt to a diverse range of sport-related adversities. Although sporting resilience captures an individual's resilience process in sport, it also is learned from non-sport components because individuals do not live in a vacuum.

The definition of sporting resilience is a comprehensive, empirically deduced definition by considering all aspects of the ontology of resilience in sport rather than reduction in favor of convenience (Podsakoff et al., 2016). The definition encompasses capacities, processes, and outcomes in line with recommendations of a constructivist, holistic conceptualization for multidimensional concepts (Blalock, 1968; MacKenzie et al., 2011). Empirical findings were systematically reviewed to formulate the final definition in evidence-based antecedents and consequences (Podsakoff et al., 2016) (see evidence mapping in Table 1). Resilience is a multidimensional construct that manifests in protective factors and outcomes (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013). Our definition comprehensively outlines the sporting resilience construct, with its constituent components of the definition open to empirical verification. This serves to circumvent ambiguity fallacy (Bennett, 2012). For example, empirical research can study the “interaction dominant” component via empirical testing with controls to see whether resilient individuals gain from interaction. The comprehensive and concrete elements of the definition are isolated from existing empirical support (see Table 1) which will aid future operationalisations of resilience to measure and test specific components of the observed reality of sporting resilience. The range of testable components proposed by the definition heeds William James' warning of vicious abstractionism which “becomes a means of arrest far more than a means of advance in thought” (James and Katz, 1975, p. 136).

Table 1 highlighted above provides the definitional clarity and empirical evidence of each component of the definition of sporting resilience. We also provide conceptual detail from the evidence synthesis to provide clarity for testability and operationalization of the definition.

• Sporting resilience is defined as “dynamic” because it is changing and is determined by temporal and interactive factors such as a moment in one's career, personal life circumstances, and nature of adversity colloquially characterized as “ups and downs” “when-what-where.” There is a constant interface between the individual and the environment, making sporting resilience “environmentally adaptable.” For instance, Fletcher and Sarkar (2016) strongly advocated how an environment providing balanced challenge and support contributes to building resilience.

• Sporting resilience is “interaction-dominant” which means it is determined by the interaction of an individual within themselves and engaging with their environments, resulting in a dynamic cycle of environmentally adaptable learning and relearning. Behavior patterns emerge and alter over time as the athlete with existing capacities interact with an ever-evolving environment resulting in a change (Hill et al., 2018a). This interactional learning occurs in sport and non-sport environment; however, an emphasis is on the sport environment because individuals spend the bulk of their time in that context.

• We hypothesize that the “dynamic” nature of sporting resilience is mediated by its “environmentally adaptable” and “interaction-dominant” components. Sporting resilience arises from, and in response to, sport-related adversities (Sarkar and Fletcher, 2013). We propose it is an iterative learning process transferrable in line with qualitative evidence from Hall (2011), which notes how resilience was something athletes had taken from sport to general life. Non-sport experiences also play an active role in the dynamic developmental process of sporting resilience. For example, dealing with race/sex/ethnic based discrimination could result in dynamic action taken by the individual to forge a self-identity, perceived/tangible social support and/or a motivational climate which would have a transfer and develop resilience to be used in sport (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2016; Wagstaff et al., 2016).

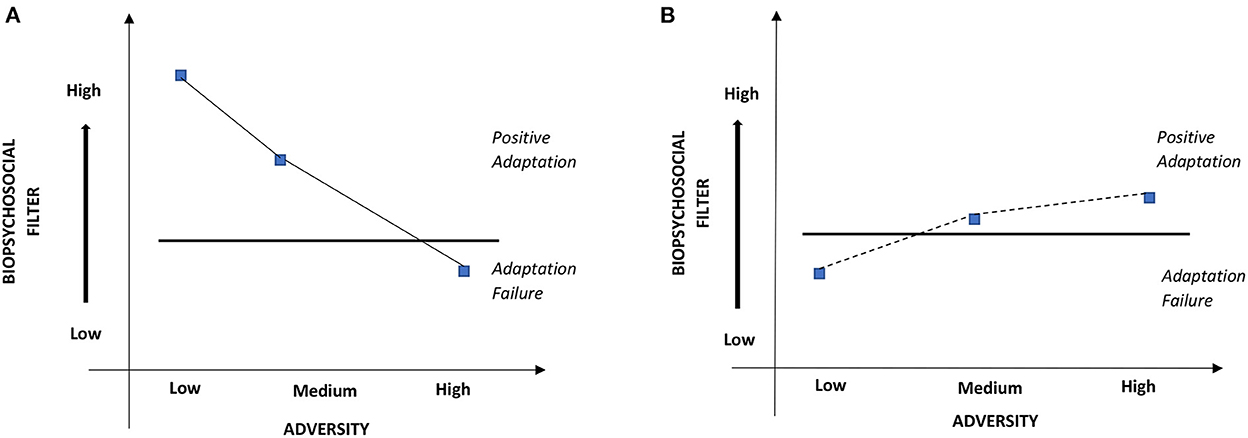

• Sporting resilience has a dynamic process-trajectory. It maximizes performance and adaptation capacity while adhering to a set of constraints determined by one's protective factors. The sport performer chooses context appropriate solutions by engaging their protective resources in an environmentally adaptable manner, ensuring performance and positive adaptation (Davids et al., 2013). This concept of “metastability” of resilience grants the ability for environmental-appropriate creative task solution which enables positive adaptation to adversity (Kiefer et al., 2018). The process is a trajectory (i.e., constrained by the extant protective resources that the individual has and must creatively use to adapt). For example, cricket batsmen who faced performance slumps avoided putting a label of “out-of-form” on his slump. He then engaged available personal resources such as work ethic, confidence and viewed “slumps as opportunities for personal growth and learning” (Brown et al., 2020, p. 284) (see Figure 2).

• The existing protective resources determine the process-trajectory which includes “metacognitive-emotional-behavioural” capacities. These capacities operate in tandem and not in isolation because cognitive evaluation of thinking, emotional responses and behavioral capacities often have high overlap (see CBT models Beck and Beck, 2011; Padesky and Mooney, 2012; Turner, 2016, 2019). These capacities develop over time through repeated adversity experiences. They are influenced by the individuals sporting and personal life experiences. For example, from an REBT perspective, resilience comprises flexible cognitive-emotive-behavioral responses to adversities which can be learned (Turner, 2016; Deen et al., 2017). We often see this through the ability to monitor, assess and replace debilitative negative thoughts with facilitative positive ones (i.e., cognitive reappraisal/flexibility) (Wu et al., 2013; McRae and Mauss, 2016).

Figure 2. Graphical model of adversity adaptation. Two examples of relationship between biopsychosocial filter strength, adversity intensity and resilience process. The left graph [Athlete (A)] is an example of an athlete with various levels of protective resources interacting with adversities of different intensities. Athlete (A) engages resilience and positively adapts when filter is strong enough to handle adversity and has adaptation failure when high-intensity/acute adversity becomes too much for low biopsychosocial resources. The right curve [Athlete (B)] is an example of a resilience response engaged over time relative to a matched adversity-biopsychological filter level where the athlete is engaged in a prolonged and iterative learning process. In the case of Athlete (B), this is an example of emergent process-trajectory of resilience (hypothetical scenario mapped for pictorial representation.

The breakdown of the definition of sporting resilience makes it operational. The dynamic nature of resilience is rooted in dynamic psychological processes, but clinical assessors such as psychometrics capture snapshots at a moment in time or retrospective, or aggregated over time (Wright and Hopwood, 2016). Assessment and formulation principles from CBT and REBT, which aim to secure quantitative/qualitative/situational information on “who-what-where-when” shows promise. Psychometrics used as part of mixed-method, longitudinal designs have already shown promise in evaluating resilience (see Kegelaers et al., 2019; Chandler et al., 2020). Qualitative evidence in extant literature rates highly and has provided insight into the dynamic process of resilience across various sport samples and contexts (see Fletcher and Sarkar, 2012; Brown et al., 2015, 2020; Morgan et al., 2015, 2019; Timm et al., 2017). These techniques would also provide insight into the “metacognitive-emotional-behavioural” capacities that the individual possesses. Motivational interviewing also holds relevance as a source of testability (Mack et al., 2017) particularly if underpinned by self-determination theory (Markland et al., 2005). Maintenance of equilibrium and positive adaptation to adversity are relatively easy to determine because they are commonly overtly observed or can be sourced by triangulation observational data and inputs from the athlete and others in the sporting environment.

Three sport-specific theories of psychological resilience materialized in this review: conceptual model of psychological resilience (Galli and Vealey, 2008), grounded theory of psychological resilience (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2012) and team resilience theory (Morgan et al., 2015). Empirical studies in sport have used non-sport theoretical models such as the resiliency model (Richardson et al., 1990), process conceptualization of resilience (Luthar et al., 2000), challenge model of resilience (Fergus and Zimmerman, 2005) and self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2012). There are also recent conceptual models, such as the dynamic perspective of resilience in sport (Hill et al., 2018a) which has sparked response commentaries (cf. Galli and Pagano, 2018; Hill et al., 2018b) (see Appendix B for overview).

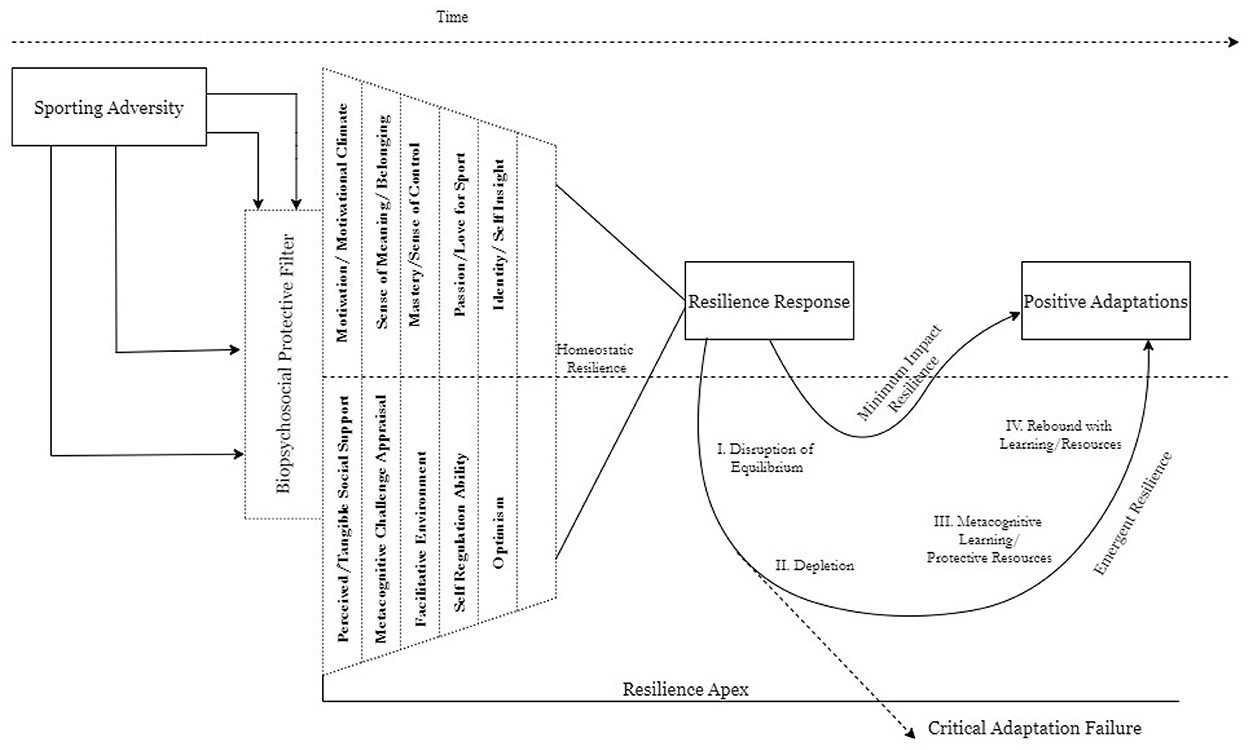

There is a theory-practice gap in sport psychology associated with transferring research into applied practice (Vealey, 2006; Keegan et al., 2017). The sharp growth of resilience research in a brief span of time (2012–2020) is at risk of becoming fragmented and suffers from the same theory-practice gap. The empirical findings of this systematic review update the theoretical conceptualisations of resilience that have empirical support. Aligned to the assertions of Den Hartigh et al. (2022), we build upon existing theoretical formulations of protective factors and resilience response to provide an evidence based conceptual advancement in line with theory development research (Magee, 1974). This integration equips researchers and practitioners with a testable framework for resilience for research and practice. Synthesizing the existing evidence (see Tables 1, 2) (cf. Appendix C), we propose the meta model of sporting resilience (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sporting resilience meta-model. The adversity experience passes through the individual's biopsychosocial protective filter. Depending on the strength of the resources available in this protective filter, the impact of the adversity initiates a specific trajectory of resilience response. Response Trajectory A- causes a minimum disruption due to low intensity adversity and/or a strong protective filter causes quicker resilience adaptation. Trajectory B- undergoes through four levels of Disruption of Equilibrium, Disruption, Metacognitive Appraisal and Rebound during the course of resilience adaptation.

The model results from a synthesis of empirical evidence. Many of the components operate concurrently and subjectively in an individual's phenomenological reality. The meta model outlines the protective factors of resilience that have received empirical support. In line with the inductive approach of this theoretical synthesis (see Jones et al., 2009 for precedence), we first reviewed the empirical evidence. Studies which provided quality evidence regarding a specific variable acting as a protective factor of resilience were included as part of the “biopsychosocial filter.” The list does not imply that every individual has all those protective factors. Rather, it highlights the idiosyncrasy of the resilience process determined by the dynamic person-environment-adversity interaction (Luthar et al., 2000; Galli and Pagano, 2018; Hill et al., 2018a; Bryan et al., 2019).

In line with Galli and Reel (2012), guided by recommendations to integrate resource theories and grounded theories of resilience (cf. Bryan et al., 2018) we propose that individuals in the sporting context face multiple simultaneous stressors/adversities of varying magnitudes. Sporting resilience is an oscillatory process in response to each stressor and adversity that develops through the individual's response to these adversities. It is not an isolated linear process with a discrete start-middle-end. This conceptualization of resilience as a dynamic process unfolding over time has found empirical support (see Galli and Vealey, 2008; Galli and Gonzalez, 2015; Bryan et al., 2018; Galli and Pagano, 2018; see also Bonanno, 2004, 2012; Bonanno and Diminich, 2013). Initial evidence from resilience research in sport psychology, where studies have included multiple data collection points/longitudinal designs, supports this conceptualization (Secades et al., 2016; Ueno and Suzuki, 2016; Timm et al., 2017; Codonhato et al., 2018; Morgan et al., 2019; Sorkkila et al., 2019). Taken together, they support resilience as a construct to have temporal stability.

Components and outcomes of resilience, however, change over time (Hill et al., 2018a) as the individual is exposed to different environments. The meta model of sporting resilience yields a relatively stable snapshot of the resilience process determined by the individual's interaction-dominant biopsychosocial protective factors. The biopsychosocial filter expands and affords an evidence-basis and testability of the “personal assets” in Fletcher and Sarkar's (2012) definition.

One theoretical advancement is that the individual develops the protective filter comprising biopsychosocial protective factors of resilience and is available when faced with a stressor. Included components of the biopsychosocial protective filter have already received preliminary empirical support (outline in Table 2). The presence or absence of these protective components determines the strength of the protective filter. In an individual case, we can measure objectively each component of this filter through established means (see Table 2). A strong and expansive protective filter grants an individual with available biopsychosocial resources to deploy to overcome an adversity which dilutes the magnitude of the adversity and its effect on the individual during the initial resilience response. For example, if an injured athlete is in a facilitative environment, receives medical and psychological support, has optimism and self-regulatory ability and a strong sense of meaning, the injured athlete finds it easier to engage resiliently against the adversity and adapt positively compared to an injured athlete who does not possess these protective resources (Podlog et al., 2014). Despite a strong protective filter; however, the individual must have a resilient response to the adversity because resilience does not imply an absence of negative pathological consequences post adversity (Southwick et al., 2014).

The protective filter is interaction dominant. It builds through dynamic individual-environment interaction because resilience includes positive adaptations which are determined by culturally/sport specific milestones which are socially constructed (Walsh, 2002; Ungar, 2008; Wagstaff et al., 2016). For example, positive adaptation is different in different sports and signposts unique things to different individuals. Sporting resilience is also environmentally adaptable because the origin of adversity is important, but so is the timing and type of adversity in the phenomenological experience (Sarkar and Fletcher, 2013; Brown et al., 2015). For instance, metacognitive challenge appraisal of the athlete will be different when they are recovering from an injury compared to when they are about to compete in the finals of an elite level global competition. This protective filter is not rigid but malleable and determines an individual's “Homeostatic Resilience” in line with extant conceptualisations that there is a stable level of resilience before perturbations and adversity (Richardson et al., 1990). The components of the protective filter do not have a fixed rank hierarchy but are subjectively evaluated to determine centrality as different stressors affect different athletes in different ways (Thelwell et al., 2007; Sarkar and Fletcher, 2014). Every individual athlete is idiosyncratic. They will not only possess but will rely on particular protective resources in different manners. For example, a sense of meaning and/or passion can be interpreted subjectively differently by two different athletes. The protective filter encompasses the proactive-protective (robust resilience) [i.e., resources which contribute to resilience (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2016)].

So how does the model work? The model showcases the resilience process of the individual at a specific period of linear time. It can trace resilient adaptation to inform the “how-what-where-when” of interventions. We start with adversity, which is percolated through the Biopsychosocial Filter. The stronger the filter is, the weaker the influence of the adversity on the individual. To use a metaphor, the filter acts like a tea strainer. The stronger the filter (resilience protective resources), the more tea leaves (adversity) it filters out. After this, the resilience response of the individual is initiated in one of two trajectories (see Figure 3).

The sporting resilience model reflects aspects of Bonanno and Diminich (2013) model, who noted that resilience has two potential pathways depending on the relevance and magnitude of the adversity. We extend this theorization by stating that the resilience response trajectories are determined by the strength of the protective filter and the response capacity. This process draws parallel from biological immune systems. A strong immune system can either protect the body entirely from illness with no adverse disruption or can engage in a defending process which disrupts internal biological homeostasis, eventually leading to health recovery (Miller and Maner, 2011; Kotas and Medzhitov, 2015) and from protective factors in 5P psychotherapy formulation model. If the protective filter is strong, it filters the adversity to a manageable level, resulting in “minimal impact resilience” (Bonanno and Diminich, 2013, p. 380). As a result, the individual maintains wellbeing and resiliently adapts using existing resources. They only dip slightly below the level of homeostatic resilience and equilibrium functioning (see Figure 3). If the protective filter is weak, however, the adversity is not filtered, and the individual engages in “emergent resilience” (Bonanno and Diminich, 2013, p. 379), and undergoes disruption to the equilibrium performance and shifts from homeostatic resilience.

In the emergent resilience trajectory, there is (1) a disruption of the equilibrium level of functioning that characterizes daily life and routine of the individual; (2) depletion of personal resources and performance because of the intensity of the adversity overwhelming the strength of the protective filter; (3) metacognitive learning via self-reflection of the experience and development of existing and new protective resources strengthening the filter; (4) rebound process with newly learned resources and a stronger filter which allows the individual resiliently adapt to the adversity leading to positive adaptation. The resilience process is reactive-integrative (rebound resilience) (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2016).

In time, both trajectories lead to eventual positive adaptation characterized by return to homeostatic resilience and equilibrium functioning. In the sporting context, this is characterized by positive mental health and positive sport-specific performance levels. Sporting resilience is a dialectical and iterative process. Qualitative evidence indicates that it goes beyond a single cycle of reconfiguration and reintegration but involves a positive link between many experiences with adversity and resilient learning from adversity encounters (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2012; Brown et al., 2015). Resilience is a break-build or learning-relearning process that happens with every adversity experience over time.

When the adversity is of a high magnitude, the individual takes trajectory B (i.e., emergent resilience). The individual possesses the appropriate adaptive resources to appraise the diverse range of adversity as a challenge rather than threat post disruption and depletion stages. This results in identification of new possibilities (Day, 2013), via metacognitive learning and utilization of resources in a dynamic, interaction-dominant process. This extends the diversifying experience model on creativity and multiculturalism (Gocłowska et al., 2018). This dialectic process is environmentally adapted to suit requirements and is proactive in identifying and reactive in using extant and/or new resources, resulting in a return to positive equilibrium/adaptation. The strength of the protective filter also determines the “resilience apex” (i.e., the limit of resilience response as determined by the strength of the protective filter, much like muscle strength determines lifting capacity). If an acute level adversity is prolonged, the individual's protective factors cannot enable positive adaptation, much like low strength and endurance cannot sustain the physiological load. Where adversity is a high magnitude and prolonged, even with a strong protective filter the individual may engage in emergent resilience trajectory and get trapped in stage II- Depletion, leading to a continuous depletion of resources resulting in a downward negative spiral (Fredrickson, 2001) which eventually crosses the resilience apex resulting in a “critical adaptation failure.”

The sporting resilience meta-model has been developed for research and practice, cognizant of the fact that stress and adversity are necessary conditions for resilience (Masten, 2001; Masten and Reed, 2002; Sarkar and Fletcher, 2014; Galli and Gonzalez, 2015; Gonzalez et al., 2018). The protective filter can be expanded as future empirical research cements the existing variables cited and/or discovers new variables which act as protective factors of resilience in sport. Conversely, as future research disproves the evidence supporting a specific component, it can be discounted as a protective component. This provides future research with a clear target of biopsychosocial components to test empirically leading to inclusion or exclusion from the list of protective resources. Using the meta-model will provide the opportunity to assess the interplay of protective factors and capture the dynamicity of the resilience process (Hill et al., 2020).

In applied practice, the model can be used to assess an individual athlete's protective filter, and trajectory of resilient adaptation. Using assessment interviews and formulation, the practitioner can map the protective factors available to the individual at that given moment in time to formulate their protective filter. As a need-analysis and/or a diagnostic guide, this will allow the practitioner to inform interventions and chart potential process-trajectories of resilience. Practitioners who use CBT/REBT in practice can utilize this model as part of their assessment and formulation stage. This model can be used as an initial self-report tool and responses could be then triangulated via psychometrics, therapeutic formulation, and observational data (see Table 2). The model can also evaluate the longitudinal duration of interventions and evaluate efficacy. For instance, after the protective filter has been identified, psychotherapy can strengthen prevailing components (i.e., highlight the self-identification and interaction between components to increase resilience via building biopsychosocial resources) (Mandrekar and Gupta, 2022).

Results of this systematic review indicate that interventions to build resilience is aligned to stress inoculation theorisation as stress experience builds mastery and improves resilience via reintegration (Flach, 1988, 1998; Galli and Vealey, 2008; Fletcher and Sarkar, 2016; Kegelaers et al., 2019). There are also suggestions that moderate cumulative lifetime adversity is associated with more positive responses to subsequently encountered stressors (Moore et al., 2018). Relevant to this is establishing an environment which balances challenge and support (Fletcher and Sarkar, 2016) which leads to acceptance of the adversity and seeking meaning/comprehension of adversity (Howells and Fletcher, 2015). Following this, there is a consequent positive reframing of negative experience and derogation of adversity related experiences allow athletes to perceive adversities in a different light to develop a positive bias in the future. Considering these recommendations, we advocate using the systematic self-reflection model of resilience (Crane et al., 2019) for resilience intervention in sport to improve the metacognitive, perceived/tangible social support, self-insight and self-regulation components of sporting resilience by enhancing the strength of the protective filter. Caution must be taken to be mindful of the magnitude of stressors provided and tailor it to the strength of the individual's protective filter to prevent the response exceeding the resilience apex and resulting in critical adaptation failure. We recommend using the “adversity exposure matrix” (Bryan et al., 2019, p. 80) which can be used with the meta-model of sporting resilience to determine the process-trajectory of sporting resilience in specific idiosyncratic cases by practitioners.

A major significance of this review is the method applied. We showcase and extend a template of theoretical advancement in psychological science, building upon the work of Fredrickson (2001) and Jones et al. (2009). We start from search and review of evidence (theoretical and empirical) already present, describe and evaluate the evidence, integrate empirically validated components into an explanatory theoretical frame. Because of the rigorous systematic review process and scientist-practitioner focus of the theory and definition, using this definition for future research rather than proposing novel operationalization's constitutes better use of resources and will develop scientific knowledge in positive psychology.

This study has undertaken a systematic synthesis of resilience literature to offer an evidence based operational definition and meta-model of sporting resilience. The definition of sporting resilience provided can be used by researchers to consolidate the operationalization of resilience research in sport. This will allow replicability of findings and greater consensus in evidence. For example, the frequency counts of supporting evidence given in Table 2 can be used by researchers to better understand the gap in evidence. The sporting resilience meta-model offers a theoretical model explaining the process-trajectory of how resilience unfolds and for applied practice assessment and interventions. Specifically, the model can be used in youth sport to develop sporting resilience profiles of young athletes and linking it to talent development for elite performance, injury rehabilitation, and performance slumps. At this stage, the model is suited to guiding practitioners rather than providing a prescriptive blueprint because theory is an ongoing process rather than an established fact (Morse, 1997). Future research needs to add to the sporting resilience meta-model to confirm/refute components as the evidence base grows. The conceptual advances of this model have been validated preliminarily by the existing data this systematic review analyzed and by a grounded theory investigation. It can be tested in other samples in research projects.

This systematic review included longitudinal studies and evidence synthesized from findings, providing initial support for the predictive stability of resilience as a construct while highlighting its constancy. Findings support the notion that resilience is an exclusive psychological construct and does not risk construct redundancy with constructs such as hardiness and/or grit (Martin et al., 2015). Therefore, directions entreated by Galli and Gonzalez (2015) and Bryan et al. (2019) have initial evidence to support resilience to be a predictive, moderately stable state-like process determined via person-environment interactions. Our review supports the findings of Bryan et al. (2019) in stating that most measures of resilience view it as a trait and there is a pressing need for a sport specific measure. We recommend future research to use the operationalisation of sporting resilience as the foundation for psychometric development (Hinkin, 1995).

From its infancy in the early 2000s to the robust growth in the last decade, the science of resilience is growing. Resilience is being heralded by the lingua franca of psychology research and applied practice. Considering the massive rupture in the continuity and normalcy of sports worldwide that is expected to follow in the aftermath of COVID-19, resilience has never been more important (Gupta and McCarthy, 2021).

Sporting resilience and its meta-model proposed in this systematic review is rooted in Vealey (2006) prompt to “examine the box” (p. 129) of a paradigm to maintain the much-needed wonder in investigative inquiry. This systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of the existing epistemological base of resilience research in sports psychology whilst striving to push its ontological box. While results of this systematic review indicate that resilience research has permeated to Non-WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) contexts (Henrich et al., 2010), research in sporting resilience should strive to be inclusive of cross-cultural theory and praxis, because sport is transcultural (Gupta, 2022; Gupta and Divekar, 2022). The operationalisation of Sporting Resilience and the meta model allows a more systematic empirical examination of the construct in sport psychology.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

SG: research ideation, design, data collection, data analysis, conceptual model, definitional advancement, and manuscript preparation. PM: research methodology, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with the author PM.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1003053/full#supplementary-material.

Adam, R., and Cogan, N. (2019). The personal meanings and experiences of resilience amongst elite badminton athletes in the build up to competition. J. Qual. Res. Sport. Stud. 13, 61–84. Available online at: https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/70304/1/Cogan_JQRSS_2019_The_personal_meanings_and_experiences_of_resilience_amongst.pdf

Allen, J. B. (2006). The perceived belonging in sport scale: examining validity. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 7, 387–405. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2005.09.004

American Psychological Association. (2011). Defining the Practice of Sport and Performance Psychology. Division 47, Exercise and Sport Psychology, Practice Committee.

Ames, C. (1992). Achievement goals and the classroom motivational climate. Student Percept. Classroom, 1, 327–348.

Aydogan, D., and Gaye, H. A. D. I. (2020). Resilience in turkish physically disabled athletes: The role of sport participation. OPUS Uluslararasi Toplum Araştirmalari Dergisi. 16, 2401–2425. Available online at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1203167

Beck, J. S., and Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive Behavior Therapy. New York, NY: Basics and beyond. Guilford Publication.

Belem, I. C., Caruzzo, N. M., Nascimento Junior, J. R. A. D., Vieira, J. L. L., and Vieira, L. F. (2014). Impact of coping strategies on resilience of elite beach volleyball athletes. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano. 16, 447–455. doi: 10.5007/1980-0037.2014v16n4p447

Bennett, B. (2012). Logically Fallacious: The Ultimate Collection of Over 300 Logical Fallacies (Academic Edition). Boston, MA: EBookIt. com.

Benzies, K. M., Premji, S., Hayden, K. A., and Serrett, K. (2006). State-of-the-evidence reviews: advantages and challenges of including grey literature. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 3, 55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00051.x

Bicalho, C. C. F., Melo, G. F., and Noce, F. (2020). Resilience of athletes: a systematic review based on a citation network analysis. Cuadernos Psicol. Deporte 20, 26–40. doi: 10.6018/cpd.391581

Blalock, H. M. Jr. (1968). “The measurement problem: a gap between the languages of theory and research,” in Methodology in Social Research, eds H. M. Blalock and A. B. Blalock (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill), 5–27. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2006.10491876

Blanco-García, C., Acebes-Sánchez, J., Rodriguez-Romo, G., and Mon-López, D. (2021). Resilience in sports: Sport type, gender, age and sport level differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 8196.

Bogar, C. B., and Hulse-Killacky, D. (2006). Resiliency determinants and resiliency processes among female adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J. Counsel. Develop. 84, 318–327.

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 59, 20. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

Bonanno, G. A. (2012). Uses and abuses of the resilience construct: loss, trauma, and health- related adversities. Soc. Sci. Med. 74, 753. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.022

Bonanno, G. A., and Diminich, E. D. (2013). Annual research review: positive adjustment to adversity–trajectories of minimal–impact resilience and emergent resilience. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 54, 378–401. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12021

Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., and Vlahov, D. (2007). What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 75, 671. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.671

Bostani, M., and Saiiari, A. (2011). Comparison emotional intelligence and mental health between athletic and non-athletic students. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 30, 2259–2263. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.441

Brown, D. J., Sarkar, M., and Howells, K. (2020). “Growth, resilience, and thriving: a jangle fallacy?” in Growth Following Adversity in Sport (New York, NY: Routledge), 59–72. doi: 10.4324/9781003058021-5

Brown, H. E., Lafferty, M. E., and Triggs, C. (2015). In the face of adversity: resiliency in winter sport athletes. Sci. Sports 30, e105–e117. doi: 10.1016/j.scispo.2014.09.006

Bryan, C., O'Shea, D., and MacIntyre, T. (2019). Stressing the relevance of resilience: a systematic review of resilience across the domains of sport and work. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 12, 70–111. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2017.1381140

Bryan, C., O'Shea, D., and MacIntyre, T. E. (2018). The what, how, where and when of resilience as a dynamic, episodic, self-regulating system: A response to Hill et al. (2018). Sport. Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 7, 355–362. doi: 10.1037/spy0000133

Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., and Stein, M. B. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 585–599. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001

Cardoso, F. L., and Sacomori, C. (2014). Resilience of athletes with physical disabilities: A cross-sectional study. Revista de Psicología del Deporte. 23, 15–22.

Carey, K. B., Neal, D. J., and Collins, S. E. (2004). A psychometric analysis of the self- regulation questionnaire. Addict. Behav. 29, 253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.001

Carver, C. S. (1998). Resilience and thriving: issues, models, and linkages. J. Soc. Issues 54, 245–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01217.x

Chacón-Cuberos, R., Zurita-Ortega, F., Olmedo-Moreno, E. M., and Castro-Sánchez, M. (2019). Relationship between academic stress, physical activity and diet in university students of education. Behav. Sci. 9, 59. doi: 10.3390/bs9060059

Chandler, G. E., Kalmakis, K. A., Chiodo, L., and Helling, J. (2020). The efficacy of a resilience intervention among diverse, at-risk, college athletes: a mixed- methods study. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 26, 269–281. doi: 10.1177/1078390319886923

Chandler, J., Higgins, J. P. T., Deeks, J. J., Davenport, C., and Clarke, M. J. (2017). “Introduction,” in Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.2.0), eds J. P.T. Higgins, R. Churchill, J. Chandler, and M. S. Cumpston. Available online at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. (accessed December 21, 2021).

Codonhato, R., Rubio, V., Oliveira, P. M. P., Resende, C. F., Rosa, B. A. M., Pujals, C., and Fiorese, L. (2018). Resilience, stress and injuries in the context of the Brazilian elite rhythmic gymnastics. PLoS ONE 13, e0210174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210174

Condly, S. J. (2006). Resilience in children: a review of literature with implications for education. Urban Educ. 41, 211–236. doi: 10.1177/0042085906287902

Cowden, R. G., and Meyer-Weitz, A. (2016). Self-reflection and self-insight predict resilience and stress in competitive tennis. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 44, 1133–1149. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2016.44.7.1133

Cox, H., Neil, R., Oliver, J., and Hanton, S. (2016). PasSport4life: A trainee sport psychologist's perspective on developing a resilience-based life skills program. J. Sport Psychol. Act. 7, 182–192. doi: 10.1080/21520704.2016.1240733

Crane, M. F., Searle, B. J., Kangas, M., and Nwiran, Y. (2019). How resilience is strengthened by exposure to stressors: the systematic self-reflection model of resilience strengthening. Anxiety Stress Coping 32, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2018.1506640

Davids, K., Araújo, D., Vilar, L., Renshaw, I., and Pinder, R. (2013). An ecological dynamics approach to skill acquisition: implications for development of talent in sport. Talent Dev. Excell. 5, 21–34.

Day, M. C. (2013). The role of initial physical activity experiences in promoting posttraumatic growth in Paralympic athletes with an acquired disability. Disabil. Rehabil. 35, 2064–2072. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.805822

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2012). “Self-determination theory,” in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, eds P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.), 416–436. doi: 10.4135/9781446249215.n21

Deen, S., Turner, M. J., and Wong, R. S. (2017). The effects of REBT, and the use of credos, on irrational beliefs and resilience qualities in athletes. Sport Psychol. 31, 249–263. doi: 10.1123/tsp.2016-0057

Den Hartigh, R. J., Hill, Y., and Van Geert, P. L. (2018). The development of talent in sports: a dynamic network approach. Complexity. 2018, 9280154. doi: 10.1155/2018/9280154

Den Hartigh, R. J., Meerhoff, L. R. A., Van Yperen, N. W., Neumann, N. D., Brauers, J. J., Frencken, W. G., et al. (2022). Resilience in sports: a multidisciplinary, dynamic, and personalized perspective. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 66, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2022.2039749

Drew, B., and Matthews, J. (2019). The prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in student-athletes and the relationship with resilience and help-seeking behavior. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 13, 421–439. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.2017-0043

Egeland, B., Carlson, E., and Sroufe, L. A. (1993). Resilience as process. Dev. Psychopathol. 5, 517–528. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400006131

Estrada, A. X., Severt, J. B., and Jiménez-Rodríguez, M. (2016). Elaborating on the conceptual underpinnings of resilience. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 9, 497–502. doi: 10.1017/iop.2016.46

Fergus, S., and Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 26, 399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognitive and cognitive monitoring: a new era of psychological inquiry. Am. Psychol. 34, 906–1111. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2012). A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 13, 669–678. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.007

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur. Psychol. 18, 12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

Fletcher, D., and Sarkar, M. (2016). Mental fortitude training: an evidence-based approach to developing psychological resilience for sustained success. J. Sport Psychol. Action 7, 135–157. doi: 10.1080/21520704.2016.1255496

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden- and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. London. Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 359, 1367–1377.

Freeman, P., Coffee, P., and Rees, T. (2011). The PASS-Q: the perceived available support in sport questionnaire. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 33, 54–74. doi: 10.1123/jsep.33.1.54

Galli, N. (2016). “Team resilience,” in Routledge International Handbook of Sport Psychology, eds R. J. Schinke, K. R. McGannon, and B. Smith (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group), 378–386.

Galli, N., and Gonzalez, S. P. (2015). Psychological resilience in sport: a review of the literature and implications for research and practice. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 13, 243–257. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2014.946947

Galli, N., and Pagano, K. (2018). Furthering the discussion on the use of dynamical systems theory for investigating resilience in sport. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 7, 351–354. doi: 10.1037/spy0000128

Galli, N., and Reel, J. J. (2012). ‘It was hard, but it was good': a qualitative exploration of stress- related growth in Division I intercollegiate athletes. Qualit. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 4, 297–319. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2012.693524

Galli, N., and Vealey, R. S. (2008). “Bouncing back” from adversity: athletes' experiences of resilience. Sport Psychol. 22, 316–335. doi: 10.1123/tsp.22.3.316

Gavrilov-Jerković, V., Jovanović, V., Žuljević, D., and Brdarić, D. (2014). When less is more: a short version of the personal optimism scale and the self-efficacy optimism scale. J. Happiness Stud. 15, 455–474. doi: 10.1007/s10902-013-9432-0

Gerring, J. (2012). Social Science Methodology: A Unified Framework, 2nd Edn. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139022224

Gledhill, A., Harwood, C., and Forsdyke, D. (2017). Psychosocial factors associated with talent development in football: a systematic review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 31, 93–112. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.04.002

Gocłowska, M. A., Damian, R. I., and Mor, S. (2018). The diversifying experience model: taking a broader conceptual view of the multiculturalism–creativity link. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 49, 303–322. doi: 10.1177/0022022116650258

Goertz, G., and Mahoney, J. (2012). A Tale of Two Cultures: Qualitative and Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.23943/princeton/9780691149707.001.0001

González, L., Castillo, I., and Balaguer, I. (2019). Exploring the role of resilience and basic psychological needs as antecedents of enjoyment and boredom in female sports. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English ed.). 24, 131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.psicoe.2019.02.001

Gonzalez, S. P., Newton, M., Hannon, J., Smith, T. W., and Detling, N. (2018). Examining the process of psychological resilience in sport: performance, Cortisol, and emotional responses to stress and adversity in a field experimental setting. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 49, 112–133. doi: 10.7352/IJSP2018.49.112

Greeff, A. P., and Human, B. (2004). Resilience in families in which a parent has died. Am. J. Family Ther. 32, 27–42.

Greenhalgh, T., and Peacock, R. (2005). Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 331, 1064–1065.

Gucciardi, D. F., Gordon, S., and Dimmock, J. A. (2008). Towards an understanding of mental toughness in Australian football. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 20, 261–281. doi: 10.1080/10413200801998556

Gucciardi, D. F., Jackson, B., Coulter, T. J., and Mallett, C. J. (2011). The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Dimensionality and age-related measurement invariance with Australian cricketers. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 12, 423–433. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.02.005

Gupta, S. (2022). “Reflect in & Speak Out: An autoethnographic study on Race and the embedded Sport Psychology Practitioner. Case Studies in Sport & Exercise Psychology. Special Issue: Making Good Trouble.

Gupta, S., and Divekar, S. (2022). A symmetry or asymmetry: reflecting upon realities of cultural practice in sport psychology. Br. Psychol. Soc. Sport Exerc. Psychol. Rev. Special Issue. 17, 60–72.

Gupta, S., and McCarthy, P. J. (2021). Sporting resilience during COVID-19: what is the nature of this adversity and how are competitive elite athletes adapting? Front. Psychol. 12, 374. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.611261

Gupta, S., and Sudhesh, N. T. (2019). Grit, self-regulation and resilience among college football players: a pilot study. Int. J. Physiol. Nutr. Phys. Educ. 4, 843–848.

Hall, N. (2011). “Give it everything you got”: resilience for young males through sport. Int. J. Mens Health. 10, 65. doi: 10.3149/jmh.1001.65

Hausenblas, H. A., and Downs, D. S. (2001). Comparison of body image between athletes and nonathletes: a meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 13, 323–339. doi: 10.1080/104132001753144437

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., and Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature 466, 29–29. doi: 10.1038/466029a

Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., et al. (2019). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. doi: 10.1002/9781119536604

Hill, Y., Den Hartigh, R. J., Meijer, R. R., De Jonge, P., and Van Yperen, N. W. (2018a). Resilience in sports from a dynamical perspective. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 7, 333. doi: 10.1037/spy0000118

Hill, Y., Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Meijer, R. R., De Jonge, P., and Van Yperen, N. W. (2018b). The temporal process of resilience. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 7, 363–370. doi: 10.1037/spy0000143

Hill, Y., Meijer, R. R., Van Yperen, N. W., Michelakis, G., Barisch, S., and Den Hartigh, R. J. (2020). Nonergodicity in protective factors of resilience in athletes. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 10, 217–223. doi: 10.1037/spy0000246

Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. J. Manag. 21, 967–988. doi: 10.1177/014920639502100509

Holt, N. L., and Dunn, J. G. (2004). Toward a grounded theory of the psychosocial competencies and environmental conditions associated with soccer success. J. Appl. Sport. Psychol. 16, 199–219. doi: 10.1080/10413200490437949

Howe, A., Smajdor, A., and Stöckl, A. (2012). Towards an understanding of resilience and its relevance to medical training. Med. Educ. 46, 349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04188.x

Howells, K., and Fletcher, D. (2015). Sink or swim: adversity-and growth-related experiences in Olympic swimming champions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 16, 37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.004

James, W., and Katz, E. (1975). The Meaning of Truth, Vol. 2. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Joanna Briggs Institute. (2017). The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews: Checklist for Prevalence Studies. Retreived November, 15, 2018.

Jones, M., Meijen, C., McCarthy, P. J., and Sheffield, D. (2009). A theory of challenge and threat states in athletes. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2, 161–180. doi: 10.1080/17509840902829331

Keegan, R. J., Cotterill, S., Woolway, T., Appaneal, R., and Hutter, V. (2017). Strategies for bridging the research-practice ‘gap'in sport and exercise psychology. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 26, 75–80.

Kegelaers, J., and Wylleman, P. (2019). Exploring the coach's role in fostering resilience in elite athletes. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 8, 239–254. doi: 10.1037/spy0000151

Kegelaers, J., Wylleman, P., Bunigh, A., and Oudejans, R. R. (2019). A Mixed Methods Evaluation of a pressure training intervention to develop resilience in female basketball players. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 8, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/10413200.2019.1630864

Kiefer, A. W., Silva, P. L., Harrison, H. S., and Araújo, D. (2018). Antifragility in sport: leveraging adversity to enhance performance. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 7, 342–350. doi: 10.1037/spy0000130

Kotas, M. E., and Medzhitov, R. (2015). Homeostasis, inflammation, and disease susceptibility. Cell 160, 816–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.010

Love, S., Kannis-Dymand, L., and Lovell, G. P. (2019). Development and validation of the metacognitive processes during Performances Questionnaire. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 41, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.12.004

Lu, F. J., Lee, W. P., Chang, Y. K., Chou, C. C., Hsu, Y. W., Lin, J. H., et al. (2016). Interaction of athletes' resilience and coaches' social support on the stress-burnout relationship: A conjunctive moderation perspective. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 22, 202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.08.005

Luthar, S., Cicchetti, D., and Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 71, 543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164

Luthar, S. S. (2006). “Resilience in development: a synthesis of research across five decades,” in Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation, eds D. Cicchetti and D. J. Cohen (John Wiley and Sons, Inc.), 739–795. doi: 10.1002/9780470939406.ch20

Luthar, S. S., and Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev. Psychopathol. 12, 857–885. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004156

Machida, M., Irwin, B., and Feltz, D. (2013). Resilience in competitive athletes with spinal cord injury: The role of sport participation. Qual. Health Res. 23, 1054–1065. doi: 10.1177/1049732313493673

Mack, R., Breckon, J., Butt, J., and Maynard, I. (2017). Exploring the understanding and application of motivational interviewing in applied sport psychology. Sport Psychol. 31, 396–409. doi: 10.1123/tsp.2016-0125

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Quart. 293–334. doi: 10.2307/23044045

Madsen, E. E., Krustrup, P., Larsen, C. H., Elbe, A. M., Wikman, J. M., Ivarsson, A., et al. (2021). Resilience as a protective factor for well-being and emotional stability in elite-level football players during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Med. Football. 5, 62–69. doi: 10.1080/24733938.2021.1959047

Mancini, A. D., and Bonanno, G. A. (2009). Predictors and parameters of resilience to loss: toward an individual differences model. J. Pers. 77, 1805–1832. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00601.x

Mandrekar, T., and Gupta, S. (2022). This is going to stay: A longitudinal mixed method pilot study on the psychological impact of living through a pandemic. Illness, Crisis and Loss. doi: 10.1177/10541373221119116

Markland, D., Ryan, R. M., Tobin, V. J., and Rollnick, S. (2005). Motivational interviewing and self–determination theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 24, 811–831. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.6.811

Marsh, H. W., Vallerand, R. J., Lafrenière, M. A. K., Parker, P., Morin, A. J., Carbonneau, N., et al. (2013). Passion: does one scale fit all? Construct validity of two-factor passion scale and psychometric invariance over different activities and languages. Psychol. Assess. 25, 796. doi: 10.1037/a0032573

Martin, J. J., Byrd, B., Watts, M. L., and Dent, M. (2015). Gritty, hardy, and resilient: predictors of sport engagement and life satisfaction in wheelchair basketball players. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 9, 345–359. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.2015-0015

Martin-Krumm, C. P., Sarrazin, P. G., Peterson, C., and Famose, J. P. (2003). Explanatory style and resilience after sports failure. Pers. Individ. Differ. 35, 1685–1695. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00390-2

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 56, 227. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227

Masten, A. S., and Reed, M. G. J. (2002). “Resilience in development,” Handbook of Positive Psychology. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 74, 88.

McRae, K., and Mauss, I. B. (2016). “Increasing positive emotion in negative contexts: Emotional consequences, neural correlates, and implications for resilience,” in Positive Neuroscience, eds J. D. Greene, I. Morrison, and M. E. P. Seligman (Oxford University Press), 159–174. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199977925.003.0011

Meggs, J., Golby, J., Mallett, C. J., Gucciardi, D. F., and Polman, R. C. (2016). The cortisol awakening response and resilience in elite swimmers. Int. J. Sport. Med. 37, 169–174. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1559773

Mellalieu, S. D., Neil, R., Hanton, S., and Fletcher, D. (2009). Competition stress in sport performers: stressors experienced in the competition environment. J. Sports Sci. 27, 729–744. doi: 10.1080/02640410902889834

Middleton, S. C., Marsh, H. W., Martin, A. J., Richards, G. E., and Perry, C. (2004). “Discovering mental toughness: A qualitative study of mental toughness in elite athletes,” in Self-Concept, Motivation And Identity, Where To From Here?: Proceedings of the Third International Biennial Self Research Conference.

Miller, S. L., and Maner, J. K. (2011). Sick body, vigilant mind: the biological immune system activates the behavioral immune system. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1467–1471. doi: 10.1177/0956797611420166