- School of Management, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China

Given that customer voice behaviors are confused with customer complaint behaviors in usage, this study thoroughly explains the essential differences between the two constructs. On that basis, this study investigates how employee–customer interaction (ECI) quality affects customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors, which is an crucial type of customer voice behaviors, by examining customer trust and identification as mediators. Data from 395 restaurant customers are collected and analyzed using structural equation modeling. Results show that ECI quality positively affects customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. In this effect, customer trust and identification play direct and sequential mediating roles. This study contributes theoretically to the current knowledge by clearly distinguishing customer voice behaviors from customer complaint behaviors and by providing new insights into the mechanism of customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors from the perspectives of service interaction and relational benefit enhancement. The practical implications of this study can help pointedly foster customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

Introduction

Based on the service-dominant logic, customers are co-producers of value for enterprises (Vargo and Lusch, 2001; Fellesson and Salomonson, 2016; Dellaert, 2019). Thus, the notion of value co-creation has received increasing attention in marketing study and practice. Value co-creation addresses the roles of customers as “partial employees” who play joint roles with enterprises in creating value in the service production (Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer, 2012; Halbesleben and Stoutner, 2013). Under the concept of value co-creation, the communication modes between enterprises and customers have changed from one-way delivery to mutual dialog, which implies that enterprises can obtain customer feedback to gain helpful information and resources for improvement (Payne et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2019). Against this background, customer voice behaviors, conceptualized as customers’ extra-role communicative behaviors of proactively expressing their suggestions or opinions to enterprises have received considerable attention to strengthen customer dialogs with enterprises (Ran and Zhou, 2020). Customer voice behaviors present a unique opportunity for enterprises to receive customer feedback, which in turn provides much value for co-creation between customers and enterprises (Bai et al., 2020). Hence, enhancing customer voice behaviors in the era of value co-creation is considerably important.

Customer voice is an important manifestation of customers’ commitment to the company (Min and Kim, 2019; He et al., 2020). Unfortunately, existing study confused customers’ voice and complaint behaviors (Wei et al., 2012; Raval, 2020). Many scholars analyzed the relationship between consumer complaint behaviors and loyalty and satisfaction (Raval, 2020). Research on consumer voice behaviors currently pays much attention to the effect of employee voice on corporate performance (Kaufman, 2014; Lin and Johnson, 2014; Chou et al., 2019; Torre et al., 2021). Besides, extant research explored the influencing factors of customer voice behaviors including satisfaction, loyalty and right (Yoon and Kim, 2016; Briñol et al., 2017; Rather and Sharma, 2017; Wan and Li, 2021). These studies mainly focused on the interactive relationship between customers and enterprises, while ignoring the interactive relationship between customers and employees. In addition, existing scholars mainly analyzed customer engagement and loyalty from customer brand identification (So et al., 2013; Rather et al., 2019; Raza et al., 2020), ignoring the mediating role of customer trust and identification in the relationship between employee–customer interaction and customer’s voice behaviors. Customer trust is an important construct in relationship marketing theory, which deals with customers’ confident beliefs about the integrity and reliability of an enterprise (Jose, 2013). Customer identification is demonstrated as positively related to customer satisfaction, loyalty, purchase intention, and product utilization behaviors (Li et al., 2021). The mediating role of customer identification between external stimuli and customer behavioral responses has been verified (Paulssen et al., 2019; Yang and Hao, 2020). Therefore, this study explores the mediating role of customer trust and identification in customer-employee interaction quality and customer voice behaviors.

The underlying mechanism of customer voice behaviors are increasingly investigated by highlighting the roles of customer inclusion, identification, and the perceived trustworthiness and power of service workers (Bove and Robertson, 2005; Béal and Sabadie, 2018; Ran and Zhou, 2019). However, existing studies have four clear drawbacks. First, customer voice behaviors are considerably confused with customer complaint behaviors. Boote (1998) refers to customer voice as an act of complaint, which expresses complaints verbally to service providers (Marquis and Filiatrault, 2002; Bove and Robertson, 2005). However, this definition of customer voice behaviors has been unable to meet the current actual situation and research. Assaf et al. (2015) proposed that customer satisfaction and complaints are two basic customer voice variables, while Béal and Sabadie (2018) divided customer voice behaviors into two dimensions, such as complaint intention and service improvement suggestions. In those studies, complaints and suggestions are all customer voices (Cossío-Silva et al., 2016; Béal and Sabadie, 2018). In general, the two terms are mixed in usage (Boote, 1998; Béal and Sabadie, 2018; Ran and Zhou, 2019), which casts a negative light on the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of these two behaviors. Therefore, the essential differences of the two constructs require clear explanation.

Second, little importance is paid to the roles of employees in the formation of customer voice behaviors, despite their inevitable customer interactions in the consumption process (Huang and Xie, 2017). Indeed, the influences of employee–customer interaction (ECI) quality on customer evaluations of service encounters and post-purchase behaviors are well documented (Zolfagharian et al., 2018; Wang and Lang, 2019). Unfortunately, the effect of ECI quality on customer voice behaviors is rarely explored. Bove and Robertson (2005) proposed that trust is a predicting factor of customer voice behaviors. Yang and Hao (2020) found that customer identification affects promotive voice behavior. Although these scholars explored the influencing factors of voice behaviors, but these belong to proximal factors. And the distal factors and mechanisms of customer voice behaviors need to be further explored. In addition, although the relationship between the enterprise and the customer will affect the customer voice behaviors. However, the relationship between ECI quality and customer voice behaviors is full of uncertainty, especially customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

Third, customer voice behaviors include promotive and prohibitive aspects (Ran and Zhou, 2020), but existing research pays great importance to the former (Chamberlin et al., 2017; Wang and Lang, 2019; Hudson et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020) while fairly neglecting the latter. Béal and Sabadie (2018) found that psychological ownership stimulates customer voice behaviors. The underlying mechanism of customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors are expected to be further explored. Fourth, the role of customer identification in driving customer voice behaviors is examined (Ran and Zhou, 2019, 2020; Rather et al., 2019; Yang and Hao, 2020), but the factors that drive customer identification are not considered. Thus, limited managerial implications are provided for the promotion of customer voice behaviors. For instance, Rather et al. (2019) indicated that customer brand identification, affective commitment, customer satisfaction, and brand trust as antecedents of customer behavioral intention of loyalty. Thus, limited managerial implications are provided for the promotion of customer voice behaviors. Although these scholars explore the impact of customer brand identification on loyalty behavior and organizational citizenship behavior, these are still near-end factors, and it is necessary to explore more remote influencing factors and mechanisms of customer voice behaviors.

To fill the gaps, the present study investigates the effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors by examining the mediating roles of customer trust and identification on the basis of clear distinctions between customer voice and complaint behaviors. The significant contributions of this study are as follows. First, the essential differences between customer voice and complaint behaviors are thoroughly explained, which provides a solid foundation for the understanding of the underlying mechanism of these two behaviors. Drawing on the study of Chamberlin et al. (2017) and Yu et al. (2020) on the classification of employee voices, we classify customer voices into promotive and prohibitive voices, and address the gap in customer voice behavior. Second, existing research explores the impact of customer corporate identity (Yang and Hao, 2020) on customer’s voice behavior, while this article explores more remote factors and verifies the positive behavior of customers on service contact and after purchase by Zolfagharian et al. (2018). This paper finds that ECI quality has a positive impact on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. This study presents a pioneer attempt to explore the role of ECI quality in predicting customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. This study is a valuable addition to the antecedents of such behaviors from the perspective of service interactions and provides helpful practical implications for its stimulation.

Third, the findings of this paper extend the research of Wang and Lang (2019) and find that the quality of customer-employee interaction can improve customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors through customer identification, not just promotive voices. This study supports the positive effects of Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer (2012) and Ran and Zhou (2020) on the role of customers as “partial employees.” In addition, the results of this research show that customer trust and identification have a positive impact on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. This validates the work of Roy et al. (2018) and Ran and Zhou (2019, 2020) and expands its application areas. Finally, two relational variables (i.e., customer trust and identification) are integrated to open the “black boxes” of how ECI quality indirectly affects customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors by building relational benefits. This integration considerably improves the works of Ran and Zhou (2019, 2020) that pay limited attention to the upstream predictors of customer identification. This paper finds that customer trust and identification play sequential mediating roles ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. This result further rationalizes the logical relationship between employee-customer relationship quality, customer trust, customer identification and customers’ voice behaviors.

Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

Customer Voice Behaviors

The concept of customer voice behaviors extends from that of employees in organizational behavior research (Ran and Zhou, 2019, 2020). Dyne and Lepine (1998) argue that employee voice behaviors act as extra-role communicative behaviors in which employees initiate putting forward constructive suggestions and opinions to organizations. Similarly, customer voice behaviors refer to customers’ proactively vocal expressions of providing feedback or viewpoints to enterprises beyond their required roles (Ran and Zhou, 2020). In light of the opinions of Groth (2005) and Yi and Gong (2006), customer voice behaviors describe that customer provide useful feedback information, particularly suggestions and opinions for product and service improvement to enterprises. Yang and Hao (2020) defined customer voice behavior as the role of consumers providing suggestions or opinions to the enterprise. Essentially, this feedback provision pertains to customer citizenship behaviors. Surprisingly, numerous studies regard customer complaint behaviors, which obviously do not pertain to customer citizenship, as a type of customer voice behaviors (Assaf et al., 2015; Béal and Sabadie, 2018; Won-Moo et al., 2018; Ran and Zhou, 2019), which is a considerable misinterpretation. Thus, distinguishing these two behaviors is necessary before conducting empirical research.

Based on the well-documented distinctions between employee voice and complaint behaviors (Barry and Wilkinson, 2016; Lu and Liu, 2016; Nechanska et al., 2020), the present study argues that customer voice and complaint behaviors have essential differences, and that the latter does not pertain to the former. Specifically, the basic purpose of customer voice behaviors is to improve enterprise performance by actively expressing customer suggestions and opinions (Ran and Zhou, 2020), while that of customer complaint behaviors is to express customer discontent, vent negative emotions, and even seek compensation from enterprises (Day et al., 1981; Bitner et al., 1990; Yang and Hao, 2020). In addition, customer complaint behaviors generally occur on the premise of dissatisfaction, that is, customers generally complain to employees when encountering unpleasant experiences in the consumption (Day et al., 1981; Bitner et al., 1990). Meanwhile, customer voice behaviors can develop in the absence of displeasure, that is, customers are likely to exhibit vocal suggestions and opinions to enterprises when they do not encounter dissatisfaction (Ran and Zhou, 2020). Essentially, customer voice behaviors pertain to a type of customer citizenship behaviors (Groth, 2005; Yi and Gong, 2006; Ran and Zhou, 2020), whereas customer complaint behaviors do not. Therefore, the influences of customer voice behaviors on enterprises are generally positive whereas those of customer complaint behaviors tend to be negative.

According to the above arguments and in accordance with the opinions of Ran and Zhou (2020), the present study divides customer voice behaviors into two types: customers’ promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors. The former refers to customer expressions of innovative suggestions and ideas for improvement of products and services of enterprises, while the latter refers to customer proactive behaviors of kindly informing enterprises of practical and potential problems that are not conducive to enterprise development (Ran and Zhou, 2020). The underlying mechanism of customer voice behaviors has been investigated (Bove and Robertson, 2005; Béal and Sabadie, 2018; Ran and Zhou, 2019, 2020). However, these studies mainly focus on the drivers of customer voice behaviors regarding its promotive aspect, but pay limited attention to the prohibitive dimension (Béal and Sabadie, 2018; Ran and Zhou, 2019) despite the latter’s contribution to enterprises by preventing potential problems and correcting actual errors (Ran and Zhou, 2020). The role of ECI quality in predicting customer voice behaviors is also scarcely examined despite its important influence on customer attitudes and behaviors (Zolfagharian et al., 2018; Wang and Lang, 2019). Accordingly, the present study highlights customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors and empirically examines the effect of ECI quality on such behaviors.

Effect of Employee–Customer Interaction Quality on Customer Prohibitive Voice Behaviors

Employee–customer interaction (ECI) is a dynamic process that generally runs through the consumption experience within the context of high-contact service delivery, such as restaurants and hotels (Huang and Xie, 2017). From the customer perspective, ECI quality is defined as customer perceptions of the superiority of their interactions with employees. High-quality ECI are characterized as customers’ sense of effectiveness, helpfulness, and comfort regarding their interactions with employees (Lin and Wong, 2020). Customers generally deal with employees when receiving services in a hospitality setting. Thus, the roles of employees in improving customer experience must not be underestimated. Employee–customer interaction quality is conductive to improving customer–employee connections and customer satisfaction and loyalty (So et al., 2013; Ranjan et al., 2015; Kaminakis et al., 2019; Wang and Lang, 2019), and moderates the positive effect of customer–to–customer interactions on brand experience (Lin and Wong, 2020). Nonetheless, scant research empirically explores the effect of ECI quality on customers’ extra-role behaviors (customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors). Therefore, the present study is carried out to fill this gap.

This study proposes that ECI quality is positively associated with customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. High-quality ECI is characterized as customers receiving personal care, useful help, and sense of genuineness from employees. The customer–employee interaction can be regarded as a type of social exchange relationship. According to the reciprocity principle in social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), if customers sense a gain of personal benefits in high-quality ECI from employees of enterprises, then they are inclined to do or give a positive act for the employees or the enterprises as rewards in the social exchange relationship. Customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors essentially pertain to a type of customer citizenship behaviors (Groth, 2005; Ran and Zhou, 2020), which can be viewed as customers’ positive rewards for employees or enterprises. Hence, in light of social exchange theory, this study argues that ECI quality positively affects customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. In addition, Yi and Gong (2006) also reveal that, as important manifestations of high-quality ECI, perceived personal attention and courteousness from employees are positively associated with customer citizenship behaviors. Therefore, this study proposes that ECI quality is positively associated with customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. Accordingly, the present study proposes that:

H1. ECI quality positively influences customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

Direct Mediating Role of Customer Trust

Customer trust is an important construct in relationship marketing theory, which deals with customers’ confident beliefs about the integrity and reliability of an enterprise (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). If customers perceive that an enterprise performs as promised or expected, then the former are inclined to believe that the latter is trustworthy and has high credibility (Kim et al., 2018). Morgan and Hunt (1994) argue that trust occurs when individuals have faith in an exchange partner’s credibility and integrity, and customer trust is the antecedent of customer commitment (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Martínez and Bosque, 2013). Accordingly, gaining customer trust is considered the prerequisite for customer loyalty (Reichheld and Schefter, 2000; Martínez and Bosque, 2013; Ranganathan et al., 2013).

High-quality ECI marked by promptness, courtesy, and thoughtfulness is regarded as a service provider–customer interface (Hartline and Ferrell, 1996; Lee et al., 2014). Service is intangible and inseparable, and therefore customers generally evaluate service enterprises on the basis of their perceptions of how well employees treat them. This view supports that higher ECI quality leads to the higher likelihood that customers perceive the organization as reliable and trustworthy (Yieh et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2014). Moreover, rapport is characterized by enjoyable ECI and helps decrease uncertainty and increase confidence (Macintosh, 2009). If customers gain personal care and attention from employees in service interactions, then they tend to develop favorable evaluations toward employees and thereby establish trust-based relationships with service enterprises (Matute et al., 2018). In addition, many existing studies provide statistical evidence for the role of ECI quality in driving customer trust (Yieh et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2014). Employee–customer interaction quality generate emotional trust of customer (Johnson and Grayson, 2005; Kumar et al., 2013). Hence, this study suggests that:

H2. ECI quality positively influences customer trust.

Based on social psychology literature, customer trust is divided into cognitive and emotional trust (Mcallister, 1995; Dirks and Ferrin, 2002; Punyatoya, 2019). Cognitive trust is based on the values, experience, and information cues shared between customers and service providers, which is the customer’s confidence or willingness to rely on the service provider (Johnson and Grayson, 2005; Castaldo, 2007; Sekhon et al., 2013). Emotional trust is the result of ECI. If service providers give more care to customers, deep emotions can be established between them (Johnson and Grayson, 2005; Harms et al., 2016). At this time, customers are more willing to make voices behaviors. Therefore, customer trust promotes customers’ voices behaviors.

A high level of trust allows customers to gain much confidence in service providers, and drives them to act as advocators for enterprises (Gremler et al., 2001). Undoubtedly, advocating customers are inclined to voluntarily exhibit voice behaviors toward enterprises for its long-term development. On this basis, Morgan and Hunt (1994) early point out that customer trust can lead to customer cooperation behaviors, which are a type of customers’ voluntary behaviors. According to social exchange theory, customer trust is a key component of relationship utility, which can enhance customers’ expectations of long-term mutual benefit. Therefore, customer trust is expected to promote customers’ supportive extra-role behaviors toward enterprises on the basis of the reciprocity principle suggested by social exchange theory (Blau, 1964). Customers are “partial employees” of the company, and their trust and sense of responsibility in the company will promote their voice behaviors (Fuller et al., 2006; Chamberlin et al., 2017; Arain et al., 2019). Furthermore, past evidence supports the positive effect of trust on customers’ beneficial behaviors toward enterprises, such as raising helpful ideas for improvements and providing feedback on service-related problems (Di et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2018; Roy et al., 2018). In essence, customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors are customers’ supportive and beneficial behaviors beyond their required roles (Ran and Zhou, 2019, 2020). Thus, this study puts forward that:

H3. Customer trust positively influences customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

Numerous studies confirm the mediating role of customer trust in the linkages between external driving factors and customer behaviors (Di et al., 2010; Martínez and Bosque, 2013; Kim et al., 2018). Apiradee and Nuttapol (2018) found online sellers can build customer engagement with customer trust as mediators. Yu et al. (2020) explored the influence of corporate social responsibility image on the consumption behavior and co-developing behavior of customers. Chen et al. (2021) found that cognitive trust increases people’s willingness to disclose information and reduces their willingness to falsify it. Delgosha and Hajiheydari (2021) drawing on trust in technology model, proposes a conceptual dual model to explain robot users’ post-adoption behaviors, while considers the mediating roles of trust. In light of relationship marketing theory, customer trust serves as a mediator to link stimulating factors and customer behavioral responses (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Martínez and Bosque, 2013). Hence, the present study considers that ECI quality, as a type of social environmental stimulus, can help develop trust-based relationships between enterprises and customers, thereby indirectly fostering customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors toward enterprises. In other words, high-quality ECI is conductive to increasing customers’ perceptions of enterprise reliability and credibility, and such perceptions in turn drive customers to exhibit various voice behaviors toward enterprises. Therefore, this study hypothesizes that:

H4. Customer trust plays a direct mediating role in the positive effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

Direct Mediating Role of Customer Identification

Customer identification is defined as customer’ cognitive state of self-categorization, connection, and sense of belonging toward an enterprise (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2003). According to social identity theory, individuals have needs to develop social identity and self-definition; therefore, customers are inclined to build close relationships with enterprises by positioning themselves as part of the organization to satisfy their intrinsic motivations (Ahearne et al., 2005; Martínez and Bosque, 2013; Mohan et al., 2021). As the level of customer identification increases, the higher the likelihood that customers exhibit positive attitudes and behaviors toward an enterprise (Ahearne et al., 2005; Ran and Zhou, 2019). On this basis, customer identification is demonstrated as positively related to customer satisfaction, loyalty, purchase intention, and product utilization behaviors (Ahearne et al., 2005; Keh and Xie, 2009; Martínez and Bosque, 2013).

High-quality ECI is conductive to creating favorable associations between employees and customers, thereby providing a unique opportunity to establish positive customer–enterprise relationships (Yim et al., 2008). Customer identification is exactly an important form of such relationships. Hence, ECI quality is considered to foster customer identification. Enjoyable ECI is the basic element of customer experience of rapport, which occurs when customers have positive interactions with employees (Gremler et al., 2001). Linzmajer et al. (2020) suggest that rapport is an important antecedent of customer identification. Accordingly, the present study argues that ECI quality can predict customer identification. Moreover, Marín and Salvador (2013) suggest that ECI quality can increase customer identification with enterprises. Similarly, Homburg et al. (2009) indicate that enjoyable ECI helps develop customers’ social identity with enterprises. Therefore, the present study posits that:

H5. ECI quality positively influences customer identification.

In light of social identity theory, strong identification prompts individuals to regard themselves to have close connections with an organization, thus motivating them to act supportively toward the organization as if doing the same for their own sake (Ran and Zhou, 2020). Moreover, existing literature has empirically addressed the role of customer identification in promoting customers’ extra-role behaviors (Ahearne et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2017; Hur et al., 2018). Customer voice behaviors pertain to a type of customers’ extra-role behavior that helps organizations understand their shortcomings and improvement directions (Ran and Zhou, 2019, 2020). Therefore, this study argues that customer identification likely affects customer voice behaviors. Using 394 students as samples, Ran and Zhou (2020) also empirically examine the role of customer identification in predicting customers’ prohibitive and prohibitive voice behaviors. Wang and Lang (2019) pointed out that the customer identification will increase customers’ emotion and commitment to the brand. Yang and Hao (2020) found that customer identification is positively correlated with customers’ voices. Thus, the present study predicts that:

H6. Customer identification positively influences customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

The mediating role of customer identification in the relationship between external stimuli and customer behavioral responses has been extensively verified (Ahearne et al., 2005; Martínez and Bosque, 2013; Hur et al., 2018). Social identity theory also supports that customer identification is often applied to link enterprise-related factors and customer responses (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2003). Bove and Robertson (2005) proposed that relational variables will be an important antecedent of customer voices. Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) believe that customer identification can satisfy consumers’ psychological needs for self-identification, and then influence their behavior. Albert et al. (2020) think that customers identification will motivate to show voluntary and positive behavior toward the company. Existing research supports the view that consumer-enterprise identity has a positive effect on consumers’ extra-role behavior (Karaosmanoglu et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2017; Hur et al., 2018).

On this basis, the present study argues that customer identification may act as a mediator in the relationship between ECI quality and customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. Specifically, as a crucial enterprise-related factor, ECI quality can potentially influence customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors through the indirect path of customer identification. In other words, ECI quality can indirectly stimulate customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors by promoting customer identification. Accordingly, this study proposes that:

H7. Customer identification plays a direct mediating role in the positive effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

Sequential Mediating Roles of Customer Trust and Identification

Previous research extensively supports the positive effect of customer trust on customer identification (Keh and Xie, 2009; Martínez and Bosque, 2013; Martíner and Ignacio, 2015). Customers generally have a good evaluation of enterprises they trust, on which basis they easily develop identification. Keh and Xie (2009) suggest that customers tend to identify with reliable and honest enterprises to facilitate self-definition and enhance self-esteem. By developing identification with enterprises characterized as credible, trustworthy, and honest, customers are inclined to depict similar profiles toward themselves (Keh and Xie, 2009; Martínez and Bosque, 2013). Ho (2014) proposes that individuals who trust a brand are likely to identify as a part of the brand community. Martíner and Ignacio (2015) similarly argue that customer identification with an enterprise in the absence of trust is almost impossible. Hence, this study posits that:

H8. Customer trust positively influences customer identification.

On the basis of the above discussions, this study argues that customer trust and identification sequentially mediate the positive effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. Specifically, ECI quality can establish customers trust (Arnold et al., 2014; Park and Jang, 2014). Customers generally have a good evaluation of enterprises they trust, on which basis they easily develop identification (Martínez and Bosque, 2013; Martíner and Ignacio, 2015). Customer identification in promoting customers’ engagement and extra-role behaviors (Wu et al., 2017; Hur et al., 2018; Roy et al., 2018). Overall, if customers experience high-quality ECI in the consumption process, then they are inclined to trust the enterprises (H2); such trust can improve customer identification with enterprises (H8); and such identification further promotes customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors (H6). As such, ECI quality can positively influence customer’ prohibitive voice behaviors though the sequential mediation of customer trust and identification. Thus, this study hypothesizes that:

H9. Customer trust and identification play sequential mediating roles in the positive effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

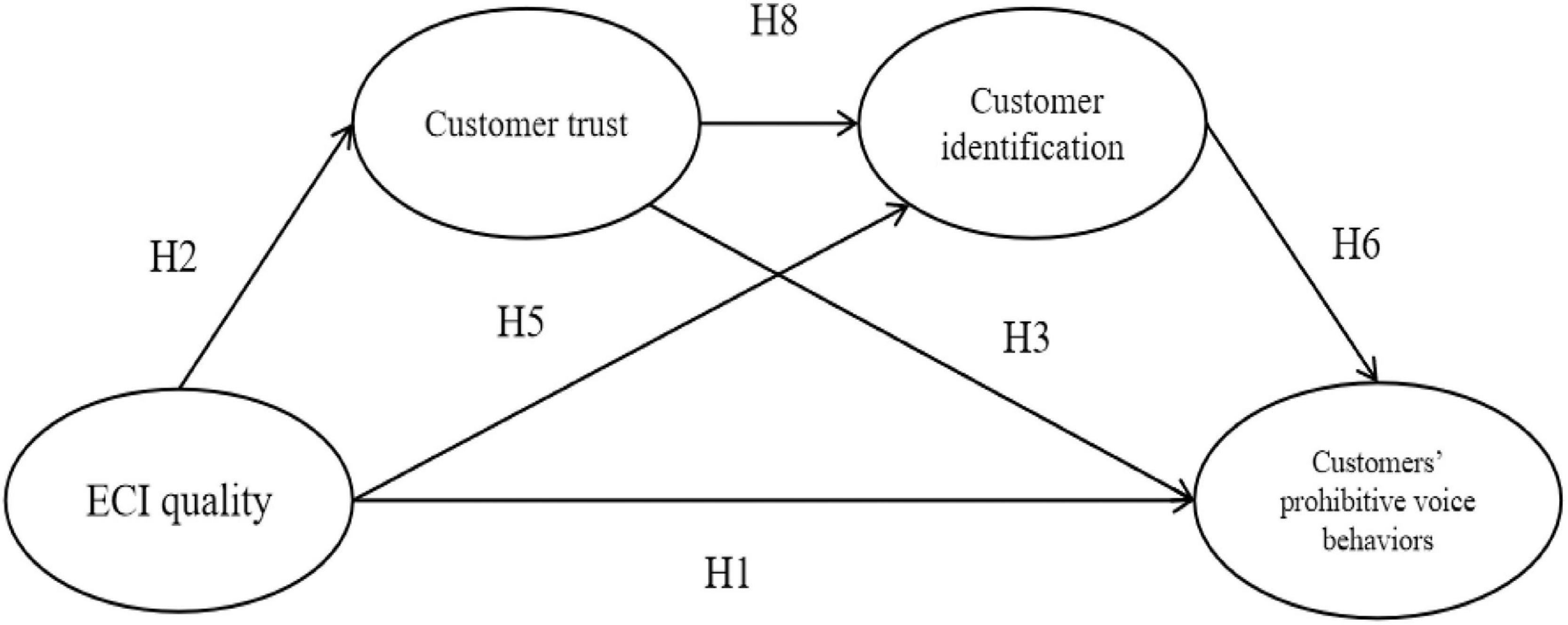

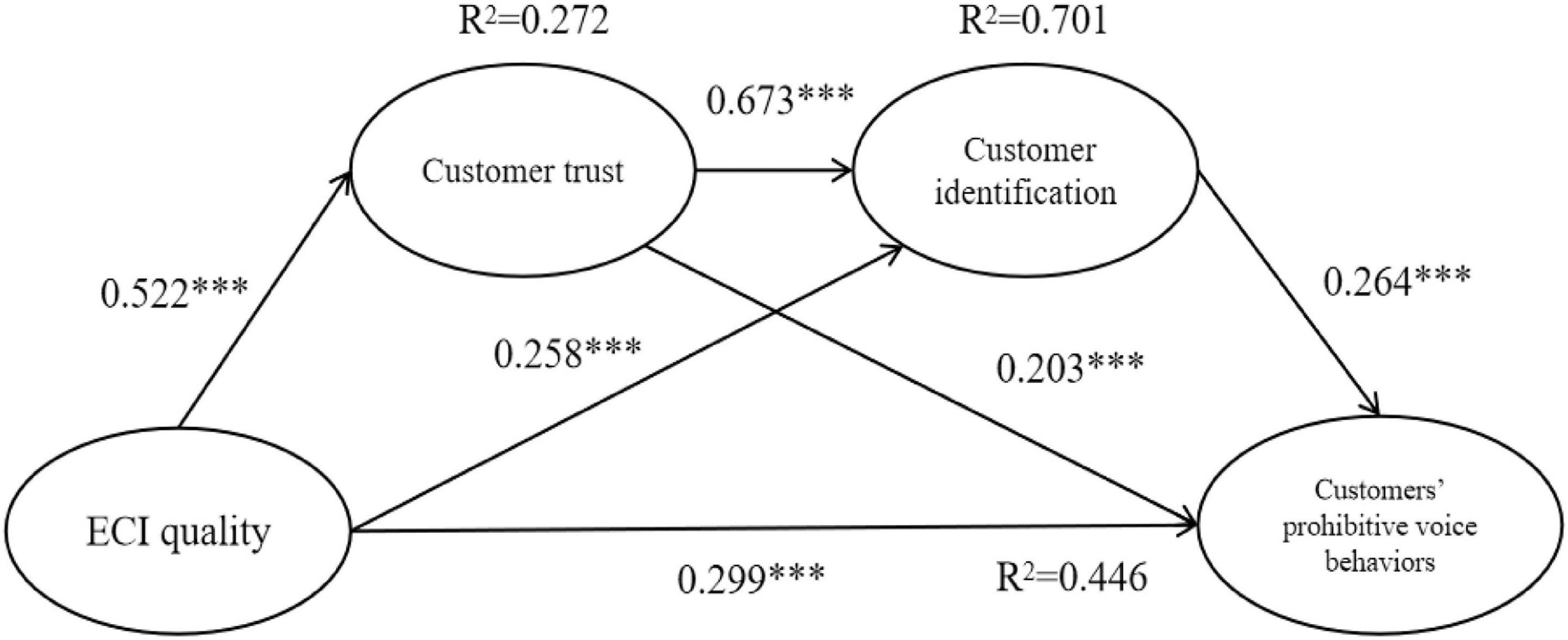

Figure 1 outlines the theoretical model where ECI quality is the antecedent, customer trust and identification are the mediators, and customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors are the outcomes. Customer trust and identification are hypothesized to directly and sequentially mediate the effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

Methodology

Measurement

Multiple-item 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree) were applied to measure all constructs. ECI quality was measured with three items obtained from Lin and Wong (2020). Customer trust was assessed with a three-item scale drawn from Morgan and Hunt (1994). Customer identification was measured with four items provided by Yang et al. (2017). Customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors were evaluated using a three-item scale adapted from Ran and Zhou (2020). Translation and back-translation procedures were administrated to translate the English scales into Chinese. In addition, a panel of researchers and customers in the pre-test helped improve the item statements to ensure suitability in the study context prior to the main survey.

Data Collection

The target population was defined as customers who had visited a restaurant in the last half month at the time of the survey. The participants were required to be 18 of age or older who were willing to help complete an online survey. The questionnaire was created and distributed via social network platforms using a snowball sampling approach in July and August 2020.

COVID–19 had been generally under control in China when the survey was conducted, and more and more people dined out at restaurants. However, to reduce unnecessary interpersonal communications with data collectors, most customers still rejected to help fill in questionnaires in a field survey. Therefore, an online survey presented an alternative way to effectively collect data. In addition, online survey is extensively applied in tourism and hospitality research and is thus suitable for this study (Roy et al., 2018; Wang and Lang, 2019; Taylor, 2020).

Similar to existing research (Yoon and Kim, 2016; Moon et al., 2017), this study used the popular snowball sampling approach which presents advantages of easily reaching large numbers of potential participants with a broad spectrum of sample distribution (Yoon and Kim, 2016). Despite its shortcoming of sample representativeness, snowball sampling approach is an adequate alternative as the use of social networks can increase the sample size and representativeness (Baltar and Brunet, 2012).

Four authors and five assistants contacted their friends and relatives to complete the questionnaire. In turn, the invited participants used their social networks to ask other respondents to fill in the questionnaire. Finally, 395 usable responses were obtained from a pool of 526 returned questionnaires. The final sample is more than 15 times the number of scale items and can thus be considered fairly sufficient (Stevens, 1996).

Data Analysis

The reliability and validity of all scales were assessed on the basis of results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Then, the proposed hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H5, H6, and H8) were statistically examined using structural equation modeling (SEM). Finally, the Bootstrapping approach was applied to test the hypotheses for mediation hypotheses (H4, H7, and H9). SPSS 24 and Amos 24 were used for the data analysis in this study.

Results

Sample Profiles

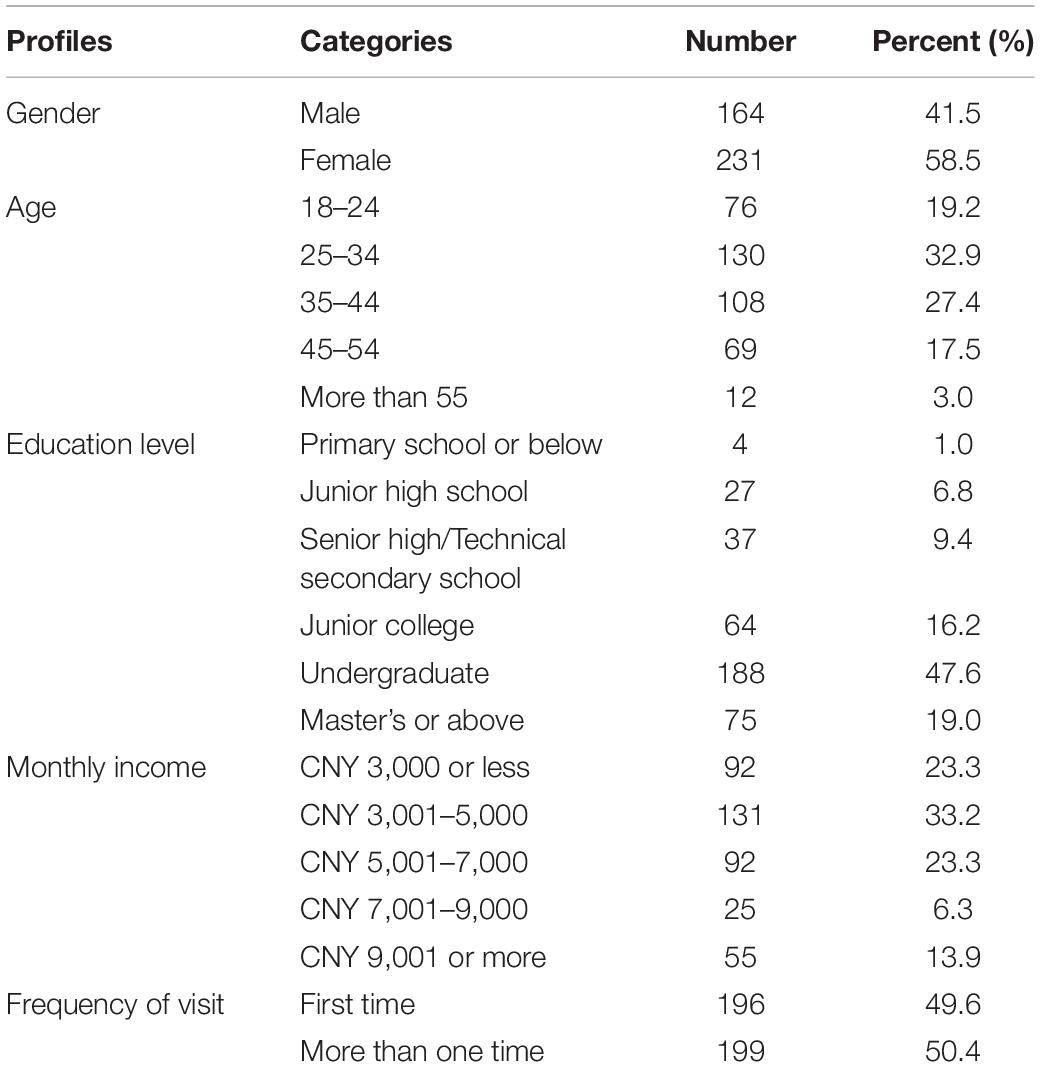

Descriptive analysis of sample profiles in Table 1 indicates that 41.5% were male customers and 58.5% were female. The majority of respondents were 25–34 years old (32.9%) followed by those aged 35–44 (27.4%). Most of the respondents held bachelor’s degrees (47.6%). With regard to monthly income, the distribution was 33.2% in the range of CNY 3,001–5,000. The respondents who visited a restaurant for the first time accounted for 49.6%.

Common Method Bias

In this study, a cross-sectional design was applied to collect data via self-reported questionnaires. Therefore, Common Method Bias (CMB) may occur. This potential issue was addressed using procedural and statistical methods. Procedurally, at the beginning of the questionnaires, participants were informed of their anonymity and confidentiality, and that each question had no right or wrong answer. Statistically, a common factor analysis test was applied to detect the possibility of CMB (Kamboj, 2020). The results indicated that the model fit indices of the simple factor model (2/df = 12.845, GFI = 0.715, CFI = 0.753, TLI = 0.704, RMR = 0.069, and RMSEA = 0.173) were worse than those of the measurement model with four-factors (2/df = 1.506, GFI = 0.967, CFI = 0.990, TLI = 0.987, RMR = 0.018, and RMSEA = 0.036). These results showed that CMB was not a concern in this study.

Measurement Model

Data normality was assessed using the skewness and kurtosis of each item. The results indicated that the distribution of skewness (ranging from −0.643 to −0.316) and that of kurtosis (from −0.215 to 1.384) were acceptable as suggested by Kline (2011). Thus, the collected data generally accorded with normality assumptions.

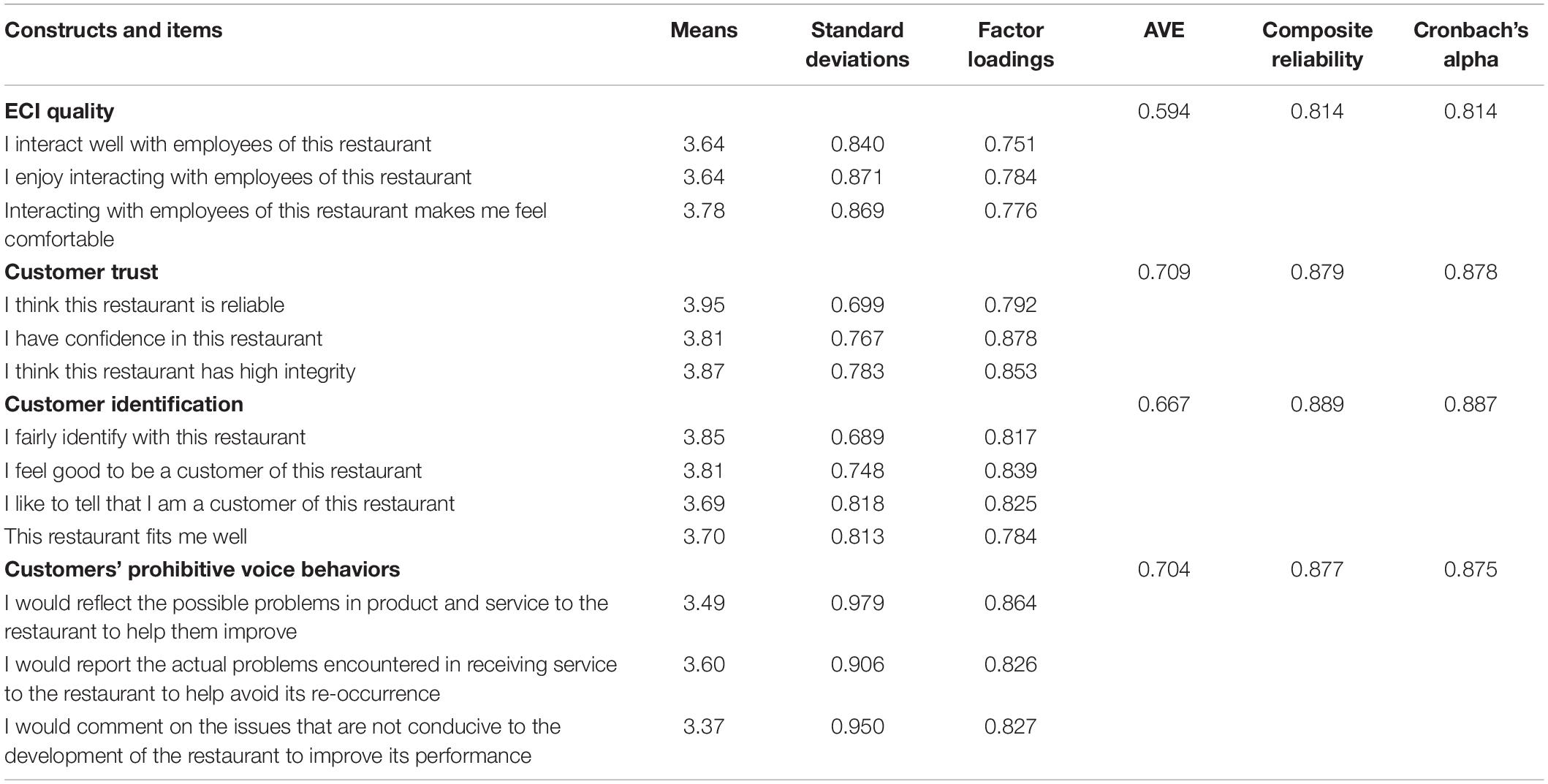

Table 2 presents the results of CFA. Cronbach’s alpha (varying from 0.814 to 0.887, greater than 0.60) and composite reliability (ranging from 0.814 to 0.889, larger than 0.60) indicated satisfactory reliability (Fornell and Larcher, 1981; Kline, 2011). In addition, the results of standard factor loadings (varying from 0.751 to 0.878, greater than 0.60) and of average variance extracted (AVE) (ranging from 0.594 to 0.709, larger than 0.50) supported acceptable convergent validity (Fornell and Larcher, 1981).

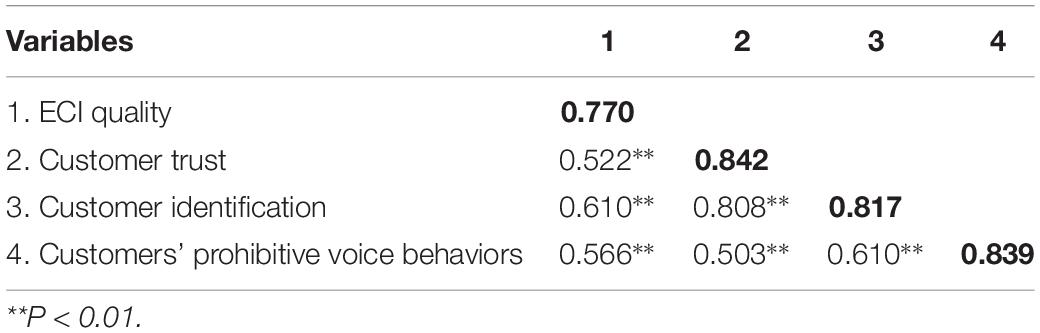

Discriminant validity was assessed using comparisons between the square roots of AVE and the corresponding Pearson correlation coefficients of any pair of constructs. Table 3 shows that the corresponding Pearson correlation coefficients were lower than the square roots of AVE of the concerned constructs, indicating good discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcher, 1981).

Structural Model

Figure 2 presents the results of SEM with a satisfied model fit (2/df = 1.506, GFI = 0.967, CFI = 0.990, TLI = 0.987, RMR = 0.018, and RMSEA = 0.036). The structural model explained 27.2%, 70.1%, and 44.6% variance of customer trust, identification, and prohibitive voice behaviors, respectively.

Figure 2 indicates that ECI quality was positively associated with customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors (β = 0.229, p < 0.001), trust (β = 0.522, p < 0.001), and identification (β = 0.258, p < 0.001). Therefore, H1, H2, and H5 were statistically supported. These findings implied that enjoyable interactions with restaurant employees motivated customers to exhibit prohibitive voice behaviors to help the restaurant achieve success. In addition, these findings also indicated that high-quality ECI was a significant accelerator for customer trust toward and identification with the restaurant. Customer trust positively influenced customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors (β = 0.203, p < 0.05), and thus statistically supported H3. These findings implied that if customers perceived the restaurant to be reliable and trustworthy, then they tended to benefit the restaurant by offering prohibitive voice behaviors. Customer identification was positively associated with customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors (β = 0.264, p < 0.01), and thus statistically supported H6. These findings implied that if customers identified with the restaurant, then they were inclined to exhibit their prohibitive “voices” to give beneficial feedback. Customer trust positively influenced customer identification (β = 0.673, p < 0.001), and thus statistically supported H8. These findings implied that customers tended to develop identification with restaurants with high integrity and reliability.

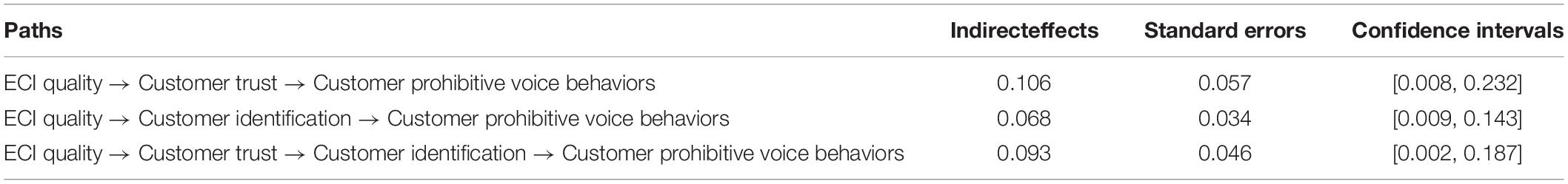

Mediation Analysis

The Bootstrapping approach with 5,000 samples and 95% confidence intervals was applied to examine the mediating roles of customer trust and identification in the relationship between ECI quality and customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. Jose (2013) suggested that the mediating effect exists if the confidence interval excludes zero, and none otherwise. Table 4 shows the results of the mediation analysis. The indirect effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors via customer trust was 0.106 with a 95% confidence interval [0.008, 0.232]. Therefore, H4 was supported. These results indicated that customer trust played a direct mediating role in the linkage between ECI quality and customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. Similarly, the indirect effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors via customer identification was 0.068 with a 95% confidence interval [0.009, 0.143]. Accordingly, H7 was supported. These results implied that customer identification also played a direct mediating role in the association between ECI quality and customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. Furthermore, the indirect effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors via customer trust and identification was 0.093 with a 95% confidence interval [0.002, 0.187]. These results indicated that customer trust and identification sequentially mediated the effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. Therefore, H9 was supported.

Discussion

Findings

First, the findings support the positive effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. High-quality ECI is characterized as customers receiving personal care, useful help, and sense of genuineness from employees. The customer–employee interaction can be regarded as a type of social exchange relationship. According to the reciprocity principle in social exchange theory, if customers gain emotion care or useful help in ECI, then they are inclined to give a positive act for the employees or the enterprises as rewards in the social exchange relationship. These findings reconfirm the importance of employee–customer interaction quality in affecting customer attitudes and behaviors in the hospitality industry (Huang and Xie, 2017; Wang and Lang, 2019). The results also support those of Yi and Gong (2006) that high-quality ECI is an important accelerator of customers’ extra-role behaviors. This finding expands research conclusions of Yang and Hao (2020) from the enerprise-customer perspective and discovers another antecedent variable that promotes customer voices from the employee-customer perspective.

In addition, the present findings indicate that customer trust and identification not only directly but also sequentially mediate the positive effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. If customers gain personal care and attention from employees in service interactions, then they tend to develop favorable evaluations toward employees and thereby establish trust-based relationships with service enterprises. In addition, many existing studies provide statistical evidence for the role of ECI quality in driving customer trust. Based on the social exchange theory and the norm of reciprocity, the senses, and experience of customers interacting with service providers can generate emotional trust. Customer trust is expected to promote the supportive extra-role behavior of customers toward the enterprise. According to the social identity theory, strong sense of common identity makes individuals see the organization as part of themselves. Customers are “partial employees” of the company, and their trust and sense of responsibility in the company will promote their opinions and behaviors. Therefore, customers with a high level of identification will be more motivated to show voluntary and positive behavior toward the company. The findings imply that when customers have enjoyable interactions with employees, they are inclined to trust and identify with the restaurant. In turn, such trust and identification simply and jointly promote customer behaviors of expressing prohibitive voices toward the restaurant.

Finally, the direct mediating roles of customer trust and identification in this study provide further evidence of their mediation effects in external stimuli on customer responses (Keh and Xie, 2009; Martínez and Bosque, 2013). The sequential mediating roles further open the “black boxes” of how ECI quality affects customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors, and support the existence of the indirect path of “ECI quality → Customer trust → Customer identification → Customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors”. If customers enjoy high ECI quality during the consumption process, they are more inclined to trust the company; this trust can increase the customer’s identification of the company. This identification further promotes customer’s prohibitive voices. Therefore, ECI quality have a positive impact on customers’ prohibitive voice behavior through the intermediary role of customer trust and identification. Such findings highly improve the understanding of the underlying mechanism of the effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors from the perspective of relational benefit enhancement of customers.

Theoretical Contribution

First, the differences between employee voice and complaint behaviors have been explicitly addressed, this study is a pioneer attempt to thoroughly differentiate the concept of customer voice behaviors from that of customer complaint behaviors. Specifically, customer voice behaviors are committed to benefiting enterprises and can occur in the absence of discontent, which essentially pertain to customer citizenship behaviors. Meanwhile, customer complaint behaviors aim to express customers’ dissatisfaction and negative emotions from unpleasant experiences or service failure in the consumption process, which do not pertain to customer citizenship behaviors. These important distinctions can provide useful reference value for future research on related topics. This study draws on the research of Liang et al. (2012) and Ran and Zhou (2020) about the classification of employee voices. We divide customer voices into promotive and prohibitive voices, which fill the gap in customer voice behavior. The new definition and dimension of customer voice proposed in this paper will help existing research on customer voice behavior and provide inspiration for future researchers.

Second, this study responds to Ran and Zhou (2020) call to pay attention to customer voice behaviors. Customer citizenship behaviors are extensively addressed in past literature (Groth, 2005; Hur et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018), but limited research focuses on customer voice behaviors, especially on the prohibitive ones. This study focuses customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors and enriches the existing literature on the predictors of such behaviors from the perspective of service interactions. The findings support the driving effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to empirically investigate the drivers of customer voice behaviors by addressing the roles of employees, and thereby helps deepen the understanding of such roles in the formation of customer citizenship behaviors. Existing research explores the impact of customer – corporate identification (Yang and Hao, 2020) on customer’s voice behavior, while this article explores more remote factors and verifies the positive behavior of customers on service contact and after purchase by Zolfagharian et al. (2018). This paper finds that ECI quality has a positive impact on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. This study presents a pioneer attempt to explore the role of ECI quality in predicting customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. This study is a valuable addition to the antecedents of such behaviors from the perspective of service interactions and provides helpful practical implications for its stimulation.

Third, the results of this paper show that customer trust and identification have a positive impact on customers’ forbidden voices. This validates the work of Roy et al. (2018) and Wang and Lang (2019) and expands their application areas. The results of this study extend the research of Wang and Lang (2019) and find that the quality of customer-employee interaction can improve the prohibited behaviors through customer identification, not just promotive voices. This research verifies the positive effects of Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer (2012) and Ran and Zhou (2020) on the role of customers as “partial employees.”

Finally, this study analyzes the underlying mechanism of how ECI quality indirectly affects customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors by examining the mediating roles of customer trust and identification. The mediating roles of customer trust and identification in the relationships between customer perceptions and behaviors have been widely explored (Ahearne et al., 2005; Martínez and Bosque, 2013; Kim et al., 2018), but scant research applies these two constructs to link customers’ perceptions of employee-related factors and customers’ extra-role behaviors. The present study adds evidence to current knowledge by exploring the direct and sequential mediating roles of customer trust and identification, and provides a comprehensive understanding of the effects of these two constructs on customers’ extra-role behaviors. To stimulate customer voice behaviors, enhancing customer trust and identification is necessary.

This article integrates two relationship variables (customer trust and recognition), and opens up the “black box” of how ECI quality indirectly affects the forbidden speech behavior of customers by establishing relationship benefits. This integration greatly improves the work of Ran and Zhou (2019, 2020), which has not yet focused on upstream predictive factors for customer identification. The research in this article finds that customer trust and identification play sequential mediating roles in the positive effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. This result further rationalizes the logical relationship between employee-customer relationship quality, customer trust, customer recognition and customer voice behaviors.

Practical Implication

The findings indicate that ECI quality has positive effects on customer trust, identification, and prohibitive voice behaviors. Therefore, effectively improving ECI quality in the restaurant context is important. Specifically, restaurant managers are suggested to pay considerable attention to improving employees’ communicative skills through targeted training. Important procedures characterized by frequent ECI, such as inquiry, ordering, and settling accounts, should be highlighted. Employees’ willingness to interact with customers is a basis of high-quality ECI. Accordingly, restaurant managers can implement measures to encourage employees to sincerely interact with customers, attach importance to customers’ personal preference, and provide customers with useful help. An important consideration is that employees should protect the personal privacy of customers in the ECI to prevent the latter from feeling upset and worried. Alternatively, an incentive system regarding ECI quality can be formulated on the basis of customer comments and scores.

In addition to the above measures for improving ECI quality, restaurant managers can use other means to promote customer trust and identification, which are found to play significant roles in predicting customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. For example, restaurant managers can foster customer trust and identification by improving service quality, enhancing firm reputation, reinforcing consumer participation, and strengthening corporate social responsibility (Keh and Xie, 2009; Martínez and Bosque, 2013; Ho, 2014). Thus, the goal of further promoting customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors can be achieved.

For another example, before the COVID-19 pandemic, the interaction between employees and customers was more face-to-face, and employees can increase service content and targeted recommendations for customers, which helps customers make appropriate choices and enhance customer trust and identification. During the epidemic, companies actively implemented social responsibilities and ensured food safety. Employees take protective measures, and provide customers with free masks, disinfection water. And employees should remind customers to pay attention to safety protection. These ECI promote customer trust and identification and encourage consumer voice behaviors. After the epidemic, more discounts will be given to customers who have made contributions to the epidemic to encourage their contributions. These can not only gain customers’ trust and identification, but also further encourage them to participate in epidemic prevention and control activities. Customers can gain recognition and trust, and encourage them to give more voices via increasing the interaction between employees and customers.

Conclusion

On the basis of social exchange and identity theories, this study explores the effect of ECI quality on customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors in the restaurant context. The mediating roles of customer trust and identification are particularly examined. Results of this study show that ECI quality positively affects customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors. In this effect, customer trust and identification play direct and sequential mediating roles. This result further rationalizes the logical relationship between employee-customer relationship quality, customer trust, customer recognition and customer voice behaviors. This study contributes theoretically to the current knowledge by clearly distinguishing customer voice behaviors from customer complaint behaviors and by providing new insights into the mechanism of customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors from the perspectives of service interaction and relational benefit enhancement. The practical implications of this study can help pointedly foster customers’ prohibitive voice behaviors.

This study acknowledges a few limitations. First, this article explores the impact of customer-employee interaction quality on customer voice behaviors. However, the customer’s voice behaviors may be affected by factors such as the customer’s own characteristics and corporate behaviors. Therefore, we encourage more research on the potential mechanism of customer voice behaviors and the results of customer voice behaviors from different theoretical perspectives. Second, the non-probability sampling technique in the online survey may lead to concerns on sample representativeness. Hence, other sampling methods can be applied for data collection to further examine the findings. The self-reported survey in a cross-sectional design may cause response biases and has limited persuasiveness to illustrate causal relationships among the variables. Future research is therefore encouraged to employ multi-source survey data based on longitudinal designs to re-examine the proposed hypotheses. Third, another limitation is that this study was conducted merely in the restaurant context in China, thus, the findings may have limited generalization in other contexts. Future research can replicate the model in other service contexts and diversely cultural settings. Finally, this study was only done in high contact industries, whether these findings apply to low contact industries remains open to debate. Thus, future research can be conducted similar research in the low contact industries context.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

GC and SL: conceptualization, methodology, software, and validation. SL: formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation. GC: writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, and project administration. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by China University Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education Reform Research Fund Project (Grant No: 2020CCJG01Z002) and the Social Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No: FJ2018MGCZ010).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their beneficial suggestions that helped improve this article.

References

Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., and Gruen, T. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of customer–company identification: expanding the role of relationship marketing. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 574–585. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.574

Albert, S., Ashforth, B. E., and Dutton, J. E. (2020). Organizational identity and identification: charting new waters and building new bridges. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 13–17. doi: 10.5465/amr.2000.2791600

Apiradee, W., and Nuttapol, A. (2018). The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J. Bus. Res. 117, 543–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.032

Arain, G. A., Hameed, I., and Crawshaw, J. R. (2019). Servant leadership and follower voice: the roles of follower felt responsibility for constructive change and avoidance-approach motivation. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 28, 555–565. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2019.1609946

Arnold, M. J., Reynolds, K. E., Jones, M. A., Tugut, M., and Gabler, C. B. (2014). Regulatory focus intensity and evaluations of retail experiences. Psychol. Market. 3, 958–975. doi: 10.1002/mar.20746

Assaf, A. G., Josiassen, A., Cvelbar, L. K., and Woo, L. (2015). The effects of customer voice on hotel performance. Int. J. Hospital. Manag. 44, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.09.009

Bai, L., Yan, X., and Yu, G. (2020). Impact of consumer engagement on firm performance. Market. Intell. Plann. 38, 847–861. doi: 10.1108/mip-08-2019-0413

Baltar, F., and Brunet, I. (2012). Social research 2.0: virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Int. Res. 22, 57–74. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5312

Barry, M., and Wilkinson, A. (2016). Pro-Social or pro-management? a critique of the conception of employee voice as a pro-social behavior within organizational behavior. Br. J. Industrial Relations 54, 261–284. doi: 10.1111/bjir.12114

Béal, M., and Sabadie, W. (2018). The impact of customer inclusion in firm governance on customers’ commitment and voice behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 92, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.019

Bhattacharya, C. B., and Sen, S. (2003). Consumer–company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Market. 67, 76–88. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., and Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. J. Market. 54, 71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2007.05.028

Boote, J. (1998). Towards a comprehensive taxonomy and model of consumer complaining behavior. J. Consumer Satisfact. Dissatisfact. Complaining Behav. 11, 140–151.

Bove, L. L., and Robertson, N. L. (2005). Exploring the role of relationship variables in predicting customer voice to a service worker. J. Retailing Consumer Serv. 12, 83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2004.03.003

Briñol, P., Petty, R. E., Valle, C., Rucker, D. D., and Becerra, A. (2017). The effects of message recipients’ power before and after persuasion: a self-validation analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 93, 1040–1053. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1040

Chamberlin, M., Newton, D. W., and Lepine, J. A. (2017). A meta-analysis of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms: identification of key associations, distinctions, and future research directions. Personnel Psychol. 70, 11–71.

Chen, S. J., Waseem, D., Xia, Z. R., Tran, K. T., and Yao, J. (2021). To disclose or to falsify: the effects of cognitive trust and affective trust on customer cooperation in contact tracing. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 94:102867. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102867

Chou, H. H., Fang, S. C., and Yeh, T. K. (2019). The effects of facades of conformity on employee voice and job satisfaction: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Manag. Decision 58, 495–509.

Cossío-Silva, F. J., Revilla-Camacho, M. A., Vega-Vazquez, M., and Palacios-Florencio, B. (2016). Value co-creation and customer loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 69, 1621–1625.

Day, R. L., Grabicke, K., Schaetzle, T., and Staubach, F. (1981). The hidden agenda of consumer complaining. J. Retail. 57, 86–106.

Delgosha, M. S., and Hajiheydari, N. (2021). How human users engage with consumer robots? a dual model of psychological ownership and trust to explain post-adoption behaviors. Comp. Hum. Behav. 117:106660. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106660

Dellaert, B. (2019). The consumer production journey: marketing to consumers as co-producers in the sharing economy. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 47, 238–254. doi: 10.1007/s11747-018-0607-4

Di, E., Huang, C. J., Chen, I. H., and Yu, T. C. (2010). Organisational justice and customer citizenship behavior of retail industries. Service Industries J. 30, 1919–1934. doi: 10.1080/02642060802627533

Dirks, K. T., and Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 611–628. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611

Dyne, L. V., and Lepine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad. Manag. J. 41, 108–119. doi: 10.5465/256902

Fellesson, M., and Salomonson, N. (2016). The expected retail customer: value co-creator, co-producer or disturbance? J. Retailing Consumer Services 30, 204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.02.006

Fornell, C., and Larcher, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.2307/3151312

Fuller, J. B., Marler, L. E., and Hester, K. (2006). Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 1089–1120. doi: 10.1002/job.408

Gremler, D. D., Gwinner, K. P., and Brown, S. W. (2001). Generating positive word-of-mouth communication through customer–employee relationships. Int. J. Service Industry Manag. 12, 44–59. doi: 10.1108/09564230110382763

Grissemann, U. S., and Stokburger-Sauer, N. E. (2012). Customer co-creation of travel services: the role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tourism Manag. 33, 1483–1492.

Groth, M. (2005). Customers as good soldiers: examining citizenship behaviors in internet service deliveries. J. Manag. 31, 7–27.

Halbesleben, J., and Stoutner, O. K. (2013). Developing customers as partial employees: predictors and outcomes of customer performance in a services context. Hum. Resource Dev. Quar. 24, 313–335. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.21167

Harms, P. D., Bai, Y., and Han, G. H. (2016). How leader and follower attachment styles are mediated by trust. Hum. Relations 69, 1853–1876. doi: 10.1177/0018726716628968

Hartline, M. D., and Ferrell, O. C. (1996). The management of customer contact service employees: an empirical investigation. J. Market. 60, 52–70. doi: 10.1080/00224540903347297

He, L., Han, D., Zhou, X., and Qu, Z. (2020). The voice of drug consumers: online textual review analysis using structural topic model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:3648. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103648

Ho, C. W. (2014). Consumer behavior on Facebook: does consumer participation bring positive consumer evaluation of the brand? Euro Med. J. Bus. 9, 252–267. doi: 10.1108/emjb-12-2013-0057

Homburg, C., Wieseke, J., and Hoyer, W. D. (2009). Social identity and the service-profit chain. J. Market. 73, 38–54. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.2.38

Huang, Q., and Xie, C. (2017). The effect of interaction between hotel employees and customers on employees’ work efficiency and customer satisfaction. Tourism Tribune 32, 66–77.

Hudson, S., Nahrgang, J. D., Newton, D. W., and Melissa, C. (2020). I’m tired of listening: the effects of supervisor appraisals of group voice on supervisor emotional exhaustion and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 105, 619–636. doi: 10.1037/apl0000455

Hur, W. M., Kim, H., and Kim, H. K. (2018). Does customer engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives lead to customer citizenship behavior? the mediating roles of customer–company identification and affective commitment. Corporate Soc. Responsibility Environ. Manag. 25, 1258–1269.

Johnson, D., and Grayson, K. (2005). Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. J. Bus. Res. 58, 500–507. doi: 10.1016/s0148-2963(03)00140-1

Kamboj, S. (2020). Applying uses and gratifications theory to understand customer participation in social media brand communities: perspective of media technology. Asia Pacific J. Market. Log. 32, 205–231. doi: 10.1108/apjml-11-2017-0289

Kaminakis, K., Karantinou, K., Koritos, C., and Gounaris, S. (2019). Hospitality service scape effects on customer–employee interactions: a multilevel study. Tourism Manag. 72, 130–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2018.11.013

Karaosmanoglu, E., Bas, A., and Zhang, J. K. (2011). The role of other customer effect in corporate marketing: its impact on corporate image and consumer-company identification. Eur. J. Market. 45, 1416–1445. doi: 10.1108/03090561111151835

Kaufman, B. (2014). Explaining breadth and depth of employee voice across firms: a voice factor demand model. J. Labor Res. 35, 296–319. doi: 10.1007/s12122-014-9185-5

Keh, H. T., and Xie, Y. (2009). Corporate reputation and customer behavioral intentions: the roles of trust, identification and commitment. Indus. Market. Manag. 38, 732–742.

Kim, M. S., Shin, D. J., and Koo, D. W. (2018). The influence of perceived service fairness on brand trust, brand experience and brand citizenship behavior. Int. J. Contemporary Hospitality Manag. 30, 2603–2621. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-06-2017-0355

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Kumar, R. V., Madupu, S., Sen, R., and Brooks, J. (2013). Affective and cognitive antecedents of customer loyalty towards e-mail service providers. J. Services Marketing 27, 195–206.

Lee, Y. K., Jeong, Y. K., and Choi, J. (2014). Service quality, relationship outcomes, and membership types in the hotel industry: a survey in Korea. Asia Pacific J. Tourism Res. 19, 300–324. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2012.749930

Li, Y., Guo, W., Armstrong, S. J., Xie, Y. F., and Zhang, Y. (2021). Fostering employee-customer identification: the impact of relational job design. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 94:102832. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102832

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., and Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two- wave examination. Acad. Manag. J. 55, 71–92. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Lin, S. H., and Johnson, R. E. (2014). Promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors: the role of self-regulation. Acad. Manag. Ann. Meet. Proc. 1, 12879–12879. doi: 10.5465/ambpp.2014.12879abstract

Lin, Z., and Wong, I. A. (2020). Cocreation of the hospitality brand experience: a triadic interaction model. J. Vacation Market. 26, 412–426. doi: 10.1177/1356766720932361

Linzmajer, M., Brach, S., Walsh, G., and Wagner, T. (2020). Customer ethnic bias in service encounters. J. Service Res. 23, 194–210. doi: 10.1177/1094670519878883

Lu, L., and Liu, J. (2016). An exploratory study on the research framework of workplace complaints. Hum. Resources Dev. China 9, 6–14.

Macintosh, G. (2009). The role of rapport in professional services: antecedents and outcomes. J. Services Market. 23, 71–79.

Marín, L., and Salvador, R. D. M. (2013). The role of affiliation, attractiveness and personal connection in consumer–company identification. Eur. J. Market. 47, 655–673. doi: 10.1108/03090561311297526

Marquis, M., and Filiatrault, P. (2002). Understanding complaining responses through consumers’ self-consciousness disposition. Psychol. Market. 19, 267–292. doi: 10.1002/mar.10012

Martíner, G. D. L. P., and Ignacio, R. D. B. R. (2015). Exploring the antecedents of hotel customer loyalty: a social identity perspective. J. Hospitality Market. Manag. 24, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2014.891961

Martínez, P., and Bosque, I. R. D. (2013). CSR and customer loyalty: the roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 35, 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.05.009

Matute, J., Palau-Saumell, R., and Viglia, G. (2018). Beyond chemistry: the role of employee emotional competence in personalized services. J. Services Market. 32, 346–359. doi: 10.1108/jsm-05-2017-0161

Mcallister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. 38, 24–59. doi: 10.2307/256727

Min, H., and Kim, H. J. (2019). When service failure is interpreted as discrimination: emotion, power, and voice. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 82, 59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.017

Mohan, M., Nyadzayo, M. W., and Casidy, R. (2021). Customer identification: the missing link between relationship quality and supplier performance. Industrial Market. Manag. 97, 220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.07.012

Moon, H., Yoon, H. J., and Han, H. (2017). The effect of airport atmospherics on satisfaction and behavioral intentions: testing the moderating role of perceived safety. J. Travel Tourism Market. 34, 749–763. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2016.1223779

Morgan, R. M., and Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment–trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Market. 58, 20–38. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0348

Nechanska, E., Hughes, E., and Dundon, T. (2020). Toward an integration of employee voice and silence. Hum. Resource Manag. Rev. 30:100674.

Park, J., and Jang, S. (2014). Psychographics: static or dynamic? Int. J. Tour. Res. 16, 351–354. doi: 10.1002/jtr.1924

Paulssen, M., Brunneder, J., and Sommerfeld, A. (2019). Customer in-role and extra-role behaviors in a retail setting: the differential roles of customer-company identification and overall satisfaction. Eur. J. Market. 53, 2501–2529. doi: 10.1108/EJM-06-2017-0417

Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., and Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 36, 83–96.

Punyatoya, P. (2019). Effects of cognitive and affective trust on online customer behavior. Market. Intell. Plann. 37, 80–96. doi: 10.1108/mip-02-2018-0058

Ran, Y., and Zhou, H. (2019). How does customer–company identification enhance customer voice behavior? a moderated mediation model. Sustainability 11:4311. doi: 10.3390/su11164311

Ran, Y., and Zhou, H. (2020). Customer–company identification as the enabler of customer voice behavior: how does it happen? Front. Psychol. 11:777. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00777

Ranganathan, S. K., Madupu, V., Sen, S., and Brooks, J. R. (2013). Affective and cognitive antecedents of customer loyalty towards e-mail service providers. J. Services Market. 27, 195–206. doi: 10.1108/08876041311330690

Ranjan, K. R., Sugathan, P., and Rossmann, A. (2015). A narrative review and meta-analysis of service interaction quality: new research directions and implications. J. Services Market. 29, 3–14.

Rather, R. A., and Sharma, J. (2017). Customer engagement for evaluating customer relationships in hotel industry. Eur. J. Tour. Hospital. Recreation 8, 1–13.

Rather, R. A., Tehseen, S., Itoo, M. H., and Parrey, S. H. (2019). Customer brand identification, affective commitment, customer satisfaction, and brand trust as antecedents of customer behavioral intention of loyalty: an empirical study in the hospitality sector. J. Global Scholars Market. Sci. 29, 196–217. doi: 10.1080/21639159.2019.1577694

Raval, D. (2020). Whose voice do we hear in the marketplace? evidence from consumer complaining behavior. Market. Sci. 39, 168–187. doi: 10.1287/mksc.2018.1140

Raza, A., Rather, R. A., Iqbal, M. K., and Bhutta, U. S. (2020). An assessment of corporate social responsibility on customer company identification and loyalty in banking industry: a PLS-SEM analysis. Manag. Res. Rev. 43, 1337–1370. doi: 10.1108/mrr-08-2019-0341

Reichheld, F. F., and Schefter, P. (2000). E-loyalty your secret weapon on the Web. Harvard Bus. Rev. 78, 105–113.

Roy, S. K., Balaji, M. S., Soutar, G., Lassar, W. M., and Roy, R. (2018). Customer engagement behavior in individualistic and collectivistic markets. J. Bus. Res. 86, 281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.06.001

Sekhon, H., Roy, S., and Shergill, A. G. (2013). Pritchard modelling trust in service relationships: a transnational perspective. J. Services Market. 27, 76–86.

So, K. K. F., King, C., Sparks, B., and Wang, Y. (2013). The influence of customer brand identification on hotel brand evaluation and loyalty development. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 34, 31–41.

Stevens, J. (1996). Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 3rd Edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Taylor, D. G. (2020). Putting the “self” in selfies: how narcissism, envy and self-promotion motivate sharing of travel photos through social media. J. Travel Tour. Market. 37, 64–77. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2020.1711847

Torre, E. D., Gritti, A., and Salimi, M. (2021). Direct and indirect employee voice and firm innovation in small and medium firms. Br. J. Manag. 32, 760–778. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12504

Vargo, S. L., and Lusch, R. F. (2001). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Market. 68, 1–17. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

Wan, W., and Li, H. (2021). Power drives consumer voice behavior. J. Contemporary Market. Sci. 4, 22–43. doi: 10.1108/JCMARS-09-2020-0039

Wang, Y. C., and Lang, C. (2019). Service employee dress: effects on employee–customer interactions and customer–brand relationship at full-service restaurants. J. Retail. Consumer Serv. 50, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.04.011

Wei, W., Li, M., Cai, L. A., and Adler, H. (2012). The influence of self-construal and co-consumption others on consumer complaining behavior. Int. J. Hospitality Manag. 31, 764–771. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.09.013

Won-Moo, H., Hanna, K., and Kyung, K. H. (2018). Does customer engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives lead to customer citizenship behavior? the mediating roles of customer-company identification and affective commitment. Corporate Soc. Responsibil. Environ. Manag. 25, 1258–1269. doi: 10.1002/csr.1636

Wu, S. H., Huang, S. C. T., Tsai, C. Y. D., and Lin, P. Y. (2017). Customer citizenship behavior on social networking sites: the role of relationship quality, identification, and service attributes. Int. Res. 27, 428–448. doi: 10.1108/IntR-12-2015-0331

Yang, A. J. F., Chen, Y. J., and Huang, Y. C. (2017). Enhancing customer loyalty in tourism services: the role of customer–company identification and customer participation. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 22, 735–746.

Yang, R., and Hao, Z. (2020). Customer–company identification as the enabler of customer voice behavior: how does it happen? Front. Psychol. 11:777.

Yi, Y., and Gong, T. (2006). The antecedents and consequences of service customer citizenship and badness behavior. Seoul J. Bus. 12, 145–176.

Yieh, K., Chiao, Y. C., and Chiu, Y. K. (2007). Understanding the antecedents to customer loyalty by applying structural equation modeling. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 18, 267–284.

Yim, C. K., Tse, D. K., and Chan, K. W. (2008). Strengthening customer loyalty through intimacy and passion: roles of customer–firm affection and customer–staff relationships in services. J. Market. Res. 45, 741–756. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.45.6.741

Yoon, D., and Kim, Y. K. (2016). Effects of self-congruity and source credibility on consumer responses to coffeehouse advertising. J. Hospitality Market. Manag. 25, 167–196. doi: 10.1080/19368623.2014.1001932

Yu, W., Han, X., Ding, L., and He, M. (2020). Organic food corporate image and customer co-developing behavior: the mediating role of consumer trust and purchase intention - sciencedirect. J. Retailing Consumer Serv. 59:102377. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102377

Zhao, Y., Zhang, J., and Wu, M. (2019). Finding users’ voice on social media: an investigation of online support groups for autism-affected users on facebook. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:4804. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234804

Keywords: customer trust, customer identification, customer voice behaviors, employee–customer interaction quality, prohibitive voice behaviors, restaurant

Citation: Chen G and Li S (2021) Effect of Employee–Customer Interaction Quality on Customers’ Prohibitive Voice Behaviors: Mediating Roles of Customer Trust and Identification. Front. Psychol. 12:773354. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.773354

Received: 29 September 2021; Accepted: 16 November 2021;

Published: 14 December 2021.

Edited by:

Muddassar Sarfraz, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Susmita Mukhopadhyay, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, IndiaEduardo Moraes Sarmento, Lusophone University of Humanities and Technologies, Portugal

Copyright © 2021 Chen and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuhao Li, eG1sc2gyMDE4QDEyNi5jb20=

Guofu Chen

Guofu Chen Shuhao Li

Shuhao Li