- 1Facultad de Educación y Ciencias Sociales, Universidad Andres Bello, Santiago, Chile

- 2Faculty of Psychology, University of the Basque Country, San Sebastian, Spain

Editorial on the Research Topic

Social Belongingness and Well-Being: International Perspectives

This Research Topic presents a set of studies examining the psychosocial determinants of Well-Being (WB). They come from different parts of the world, and several of them are cross-cultural. Rather than merely reporting what they say, we believe this editorial can serve in a better way positioning them among the debate regarding the different concepts currently used to report this still nebulous field of belongingness.

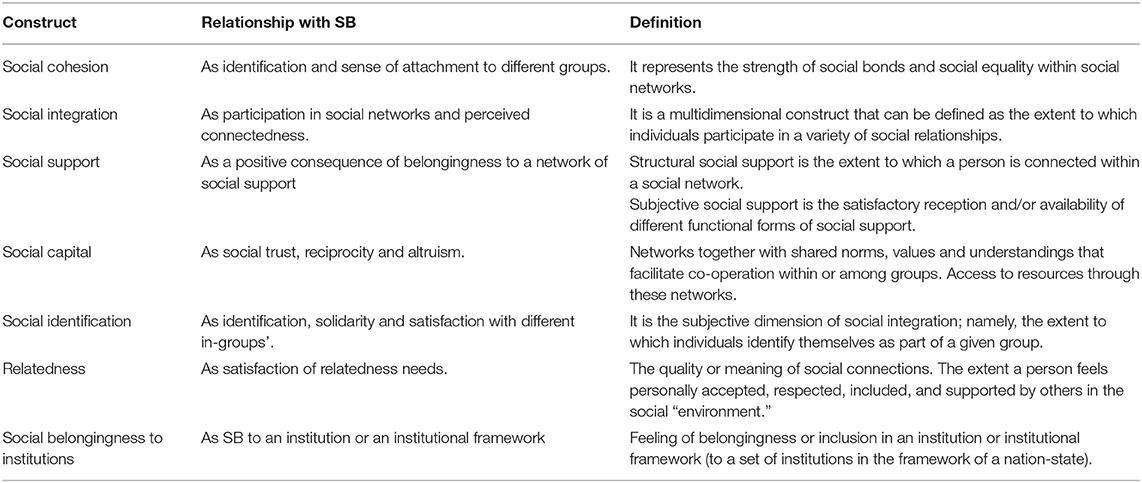

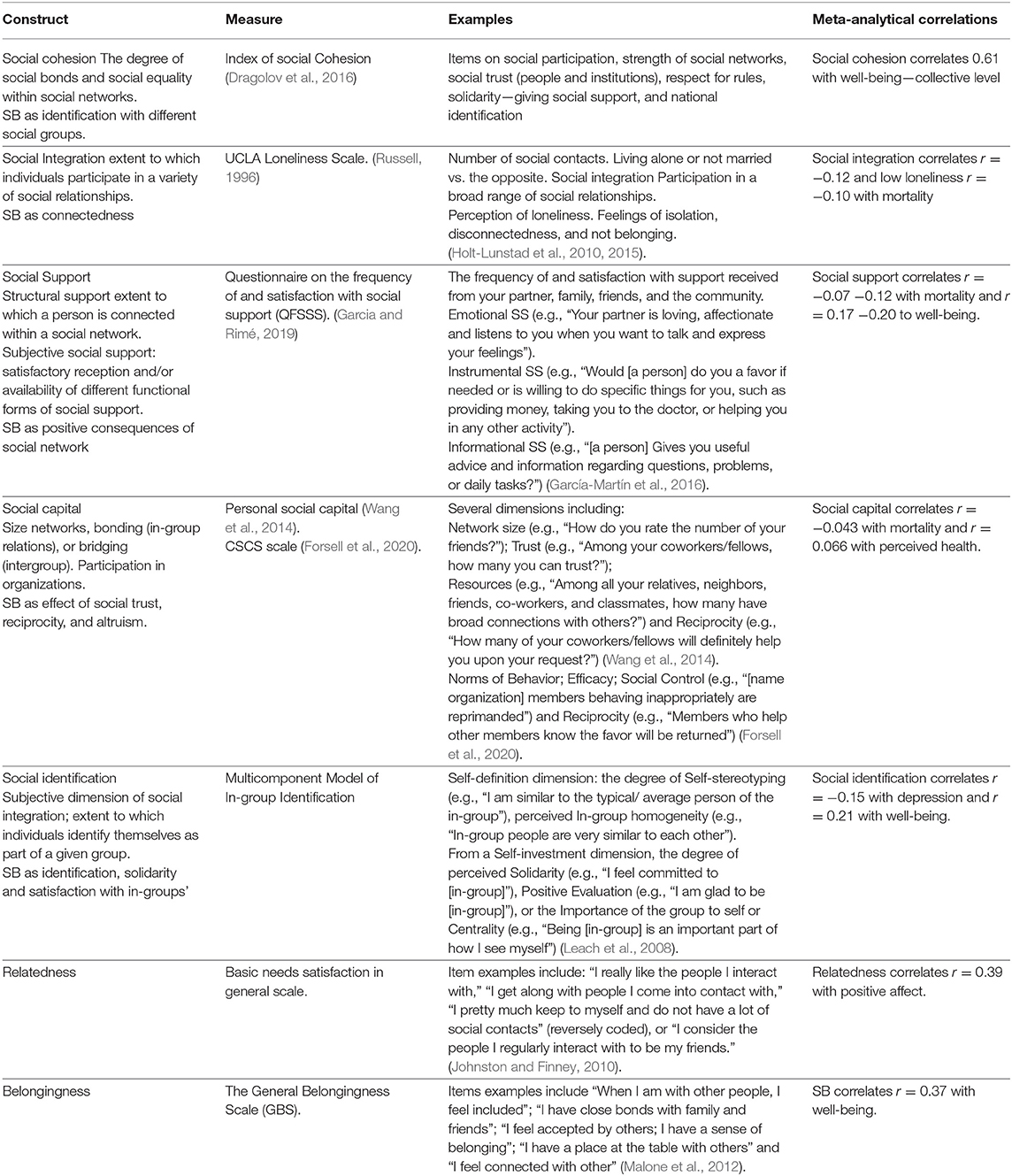

The literature on social relations and WB describes several concepts as associated with social belongingness (SB). Among them, we can find social cohesion (SCo), social integration (SI), social support (SS), social capital (SC), social or group identification (IS), and belonging or relatedness needs (RN)—see Table 1.

Durkheim defines SCo as a characteristic of a society that shows strong social bonds (Durkheim, 1897/1963). A recent conceptual review includes in SCo a social-psychological perspective of it as an attraction to the group and social capital (Schiefer and van der Noll, 2016). The definition of SCo from social psychology emphasizes the subjective aspect, affirming that it is the “degree of consensus felt by the members of a social group in the perception of belonging to a common project or situation” (Morales et al., 2007: 810). SCo could be defined as a collective attribute from a macrosocial approach, indicating the extent of connectedness and solidarity among groups in society. Social belongingness is an aspect or consequence of higher SCo, a subjective feeling of social integration related to identification and attachment to groups that enhances WB (Schiefer and van der Noll, 2016). Based on Schiefel and van der Noll, an SCo index was created, including social participation, the strength of social networks, social trust (people and institutions), respect for rules, solidarity—the first components are similar to SC (see Table 2 for items). Controlling GDP and Gini Index, the national mean of SCo predicts B = 0.17 individual WB in 34 nations (Dragolov et al., 2016).

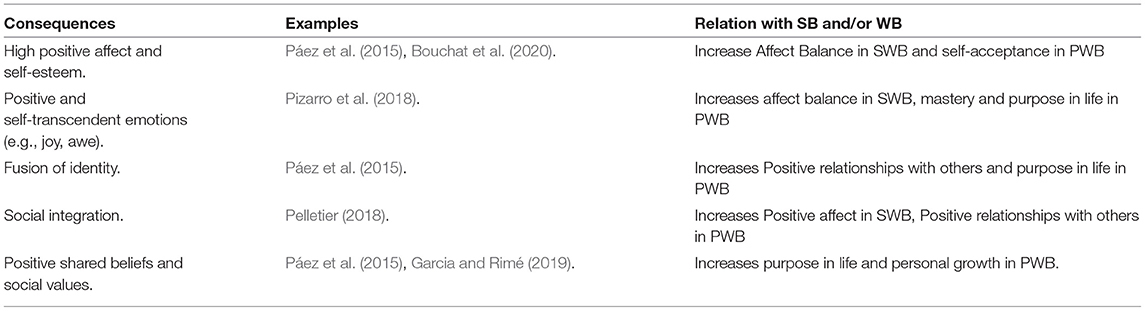

In this monograph, five studies deal with SCo and WB. Both Wlodarczyk et al. and Zumeta et al. show that effervescence during collective gatherings or perceived emotional synchrony is the primary mechanism explaining positive effects on social cohesion and WB of demonstrations and rituals (see Table 3). Reyes-Valenzuela et al. examined responses to collective trauma or disasters. They found that the intensity of the trauma influences social well-being through the mediation of collective effervescence or social sharing of emotions and community appraisal, allowing communities to cope collectively with extreme adverse events. Bravo et al. report that identification with the national football team predicts collective pride that mediates the relationship between identification with the national team and WB (see Table 3). Finally, Torres et al. report that the frontiers between individual well-being and community and even national well-being are diffuse, challenging the idea of subjective well-being only as an individually based phenomenon.

Table 3. Effects of participation in collective gatherings and perceived emotional synchrony on well-being.

SC refers to a successful level of social integration that affords SB. Studies in SC tradition characterize social cohesion by strong social networks and a high level of generalized trust (Ponthieux, 2006). A meta-review concludes that nine reviews provided strong, and sixteen provided weak to moderate evidence that SC is related to health (Ehsan et al., 2019). Three meta-analyses found minor SC effects on mortality and self-rated health (Gilbert et al., 2013; Choi et al., 2014; Nyqvist et al., 2014). Some studies even suggest associations between the perception of health service treatment and subjective well-being (Rubio et al., 2020). Individuals with a more extensive social network, who perceived higher social cohesion and trusted their neighbors, were more likely to report higher WB (Hart et al., 2018). Montero et al., found that more segregated zones show higher WB, probably because neighborhoods' income homogeneity reinforces social capital. Da Costa et al. show that micro-level factors such as a transformational culture, close to a high SC in the organization, are directly and indirectly associated with individual WB through psychosocial factors like low stress, high role autonomy, social support, and quality leadership. These results are consistent with longitudinal work reported on the relationship between work and subjective well-being (Unanue et al., 2017). However, meso-social factors influence only social WB or emotional climate. Lopez et al. found that a positive school climate, beyond students' individual socio-demographic and family support, predicts WB. Labra et al. show that passing through the university increases the likelihood of forming friendship networks, a kind of social capital that can reduce socioeconomic segregation in highly unequal societies.

SI is defined as the frequency and number of social contacts or as the number of social ties or social network size. Durkheim-inspired SI theory posits that WB would be proportional to the degree of social integration of people in the groups they belong to (Berkman et al., 2000). Three meta-analyses found small associations between mortality and quantitative SI and subjective SI or low loneliness (Schwarzer and Leppin, 1989; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010, 2015). Ventura-Leon et al. report that a scale of fear of loneliness correlates negatively with WB.

Another literature emphasizes the construct of SS as essential to the positive effect of SB. House et al. (1988) identify SS as a process through which networks or structures of social relations may influence WB. Structural SS refers to how a person is integrated within a social network, like the number of social ties (see social network item in SC). Functional SS looks at the specific functions that members in this social network can provide, such as emotional, instrumental, and informational support (House et al., 1988; Turner and Turner, 2013). In this sense, SB is related to satisfactory functional SS. Four meta-analyses (Schwarzer and Leppin, 1989; Pinquart and Sorensen, 2000; Chu et al., 2010; Bender et al., 2019) found that subjective and objective SS correlates with WB. Marenco-Escudero et al. found an association between SS and network size with community empowerment—but marginally significant. Quintero et al. found that the WB of victims of collective violence in Colombia who returned to their places of origin was higher than those who chose to settle elsewhere, probably because the first could strengthen SS in their old neighborhood's networks. Cobo-Rendon et al. show that people who improve their balance of affects increase SS, while those who worsen it decrease it. Donoso et al. examine the effects of social media on well-being, reporting that intense use of the internet for social, recreational, and educational purposes, as long as it is not problematic, has a positive association with students' subjective well-being.

Social psychologists posit that the current operationalization of social integration as the frequency of social contacts neglects the subjective dimension, namely IS (Postmes et al., 2018). Leach et al. (2008) proposed the Group Identification Scale. This scale includes a self-definition dimension, focusing on the perceived similarity of the self to prototypical members of the in-group. This dimension also includes an appraisal of the in-group homogeneity. The scale also has a self-investment dimension, referring to importance, solidarity (“I feel committed to [in-group]”), and satisfaction (“I am glad to be [in-group]”) (Leach et al., 2008). The last two components of identification are akin to SB. WB correlates with organizational IS (Steffens et al., 2016) and ethnic IS (Smith and Silva, 2011). IS was found to be negatively associated with depression (Postmes et al., 2018). Some studies found that IS predicts WB better than quantitative social support (Sani et al., 2012), while other studies found that SS was a strong predictor than IS of WB (Haslam et al., 2005). Zabala et al. support the association between Basque IS, collective empowerment, and WB. Cuadros et al. show structural validity of collective esteem scale, and scale scores correlate with WB. Pinto et al. find that the European supranational identity is associated with social WB or a climate of prosocial behavior and migrant inclusion. Garcia et al. show that ethnic IS buffers distress in the face of discrimination and is associated with WB. Moyano-Díaz and Mendoza-Llanos show that participation in groups with a sense of belonging to the neighborhood, such as community-based organizations, is associated with WB. Nonetheless, it seems to be social identification with the neighborhood -and not belongingness- that predicts WB. Navarro-Carrillo et al. analyze a classic issue: how objective and subjective measures of socioeconomic status correlate with WB – r = 0.16 and r = 0.22, respectively (Zell and Strickhouser, 2018). They adapted the MacArthur pictorial social ladder to income, education, and occupation that emerged as predictors of psychological WB over and above the MacArthur Scale.

Baumeister and Leary (1995) argue that belongingness is a social need, whose essential components are regular social contact and feelings of connectedness, and satisfaction of this need reinforces WB. Ryan and Deci (2017) postulates relatedness as a basic need that involves feeling a sense of support and connection with others and is akin to SB. The Basic Needs Satisfaction Scale measures relatedness with items like “I really like the people I interact with” (Johnston and Finney, 2010). A meta-analysis found that satisfaction of relatedness correlates with WB (Stanley et al., 2020). Pardede et al. explore different dimensions of belongingness. They do so by analyzing several items representing the need for acceptance and belongingness. They found only three correlated dimensions, a factor of belonging, one of emotional expression, and another of self-presentation to others—showing the importance of sharing emotions for SB. Gonzalez et al. found that subjective evaluation and functioning or satisfaction of basic needs, social ties, and respect predicts WB. They also report that functioning respect and human security predicts social WB. García-Cid et al. show that a sense of community that includes emotional connection with the group buffers the adverse effects of discrimination on the psychological WB of migrants. Urzua et al. examines the effect of discrimination in migrants and found that negative affect mediates between the first and low WB. Simkin examines the experiences of Latin American Jews that migrated to Israel and found that the centrality of this event was positively related to WB—probably because migration satisfies needs for belongingness and is congruent with self-transcendent beliefs. Oriol et al. analyze the role of self-transcendent prosocial aspirations, confirming that they were related directly to WB and indirectly through the self-transcendent emotion of gratitude.

Finally, a more focused tradition analyzes the association between social belonging and adjustment occurring in formal institutions, such as schools (Malone et al., 2012). Students who feel personally accepted and supported by others in the school report positive WB (Korpershoek et al., 2019). Paricio et al. found that group identification with the school correlates with hedonic and psychological WB. Mera-Lemp et al. show that self-efficacy reduced the negative effect of prejudice in satisfaction with school in immigrant students, suggesting that improving intercultural skills can increase SB in school. Cespedes et al. found that migrants students report a higher self-academic concept than native, but not higher WB. Correlations between academic self-concept and WB were lower in migrants than natives, showing the limits of academic success to enhance WB. Gempp and Gonzalez-Carrasco examine peer relatedness, school satisfaction, and life satisfaction in secondary school students. A reciprocal influence between school satisfaction and overall life satisfaction was found, and the association of peer relatedness with life satisfaction was fully mediated by school satisfaction.

A Brief Balance and Future Challenges

The COVID 19 pandemic has meant fundamental challenges to the way we understand our nexuses with other people. Extended periods of isolation have affected the way we interact with people, replacing, for a high number of people, the usual face-to-face contact for a technologically mediated one. The pandemic has also limited the way we interact in face-to-face settings by enforcing social distancing rules. The need to be careful about the people around us has brought a new meaning to the Sartrean idea that “L'enfer, c'est les autres.”

These new ways of interacting have challenged several aspects of the way we used to create society. The pandemic has put a heavy strain on families, increasing their interactions in restricted spaces and sharing personal space for more extended and intense periods. It has challenged the way we educate, forcing the closure of schools and re-engaging the family in educational activities. It has also meant transformations in the world of work, which most probably will have a long-lasting effect, such as remote working agreements. These changes will affect traditional sources of socialization, such as labor unions or educational institutions, requiring them to update and adapt to this new, less territorially based world or witnessing a severe weakening of their social relevance. Finally, it has also affected the way we celebrate and play, modifying the way collective gatherings and rituals are enacted.

While we develop a “psychosocial vaccine” to prevent the long-lasting adverse psychological effects of the pandemic, we must remember that what makes us human is, at the very end, to be among humans.

We expect that the articles contained in this Research Topic have contributed to this end, highlighting the complexities of researching how belongingness affects our well-being.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Spanish Mineco Grant Culture, Coping and Emotional Regulation: well-being and community coping [PID2020-115738GB-I00] and grants SCIA ANID CIE160009 and FONDECYT 1181533 from the Chilean Agencia Nacional de Investigacion y Desarrollo. The authors also want to recognize Cuma and Uma for their continual social support.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bender, M., van Osch, Y., Sleegers, W., and Ye, M. (2019). Social support benefits psychological adjustment of international students: evidence from a meta-analysis. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 50, 827–847. doi: 10.1177/0022022119861151

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., and Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 51:843857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4

Bouchat, P., Rimé, B., Van Eycken, R., and Nils, F. (2020). The virtues of collective gatherings. A study on the positive effects of a major scouting event. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 50:189201. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12649

Choi, M., Mesa-Frias, M., Nüesch, E., Hargreaves, J., Prieto-Merino, D., and Bowling, A. (2014). Social capital, mortality, cardiovascular events and cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43:18951920. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu212

Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A., and Hafner, E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and WB in children and adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 29, 624–645. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.624

Dragolov, G., Ignacz, Z. S., Lorenz, J., Delhey, J., Boehnke, K., and Unzicker, K. (2016). Social Cohesion in the Western World. What Holds Societies Together. Springer Briefs in WB and Quality of Life. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-32464-7

Ehsan, A., Klaas, H. S., Bastianen, A., and Spini, D. (2019). Social capital and health: a systematic review of systematic reviews. SSM Popul. Health 8:100425. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100425

Forsell, T., Tower, J., and Polman, R. (2020). Development of a scale to measure social capital in recreation and sport clubs. Leisure Sci. 42, 106–122. doi: 10.1080/01490400.2018.1442268

Garcia, D., and Rimé, B. (2019). Collective emotions and social resilience in the digital traces after a terrorist attack. Psychol. Sci. 30, 617–628. doi: 10.1177/0956797619831964

García-Martín, M., Hombrados-Mendieta, I., and Gómez-Jacinto, L. (2016). A Multidimensional approach to social support: the questionnaire on the frequency of and satisfaction with social support (QFSSS). Anal. Psicol. 32, 501–515. doi: 10.6018/analesps.32.2.201941

Gilbert, K. L., Quinn, S. C., Goodman, R. M., Butler, J., and Wallace, J. (2013). A meta-analysis of social capital and health: a case for needed research. J. Health Psychol. 18, 1385–1399. doi: 10.1177/1359105311435983

Hart, E., Lakerveld, J., McKee, M., Oppert, J. M., Rutter, H., Charreire, H., et al. (2018). Contextual correlates of happiness in European adults. PLoS ONE 13:e0190387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190387

Haslam, S. A., O'Brien, A., Jetten, J., Vormedal, K., and Penna, S. (2005). Taking the strain: social identity, social support, and the experience of stress. British J. Soc. Psychol. 44:355370. doi: 10.1348/014466605X37468

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., and Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Pers. Psychol. Sci. 10, 227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., and Layton, J. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

House, J. S., Landis, K. R., and Umberson, D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science 241, 540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889

Hu, T., Zhang, J., and Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Pers. Individ. Diff. 76, 18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039

Johnston, M. J., and Finney, S. F. (2010). Measuring basic needs satisfaction: evaluating previous research and conducting new psychometric evaluations of the Basic Needs Satisfaction in General Scale. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 35, 280–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.04.003

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., and de Boer, H. (2019). The relationships between school belonging and students' motivational, social-emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes in secondary education: a meta-analytic review. Res. Pap. Educ. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116

Leach, C. W., van Zomeren, M., Zebel, S., Vliek, M. L. W., Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., et al. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95, 144–165. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.144

Malone, G. P., Pillow, D. R., and Osman, A. (2012). The General Belongingness Scale (GBS): assessing achieved belongingness. Pers. Individ. Diff. 52, 311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.027

Morales, J. F., Gaviria, E., Moya, M., and Cuadrado, I. (2007). Psicología Social. Madrid: McGraw Hill.

Nyqvist, F., Pape, B., Pellfolk, T., Forsman, A. K., and Wahlbeck, K. (2014). Structural and cognitive aspects of social capital and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Soc. Indic. Res. 116, 545–566. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0288-9

Páez, D., Rimé, B., Basabe, N., Wlodarczyk, A., and Zumeta, L. (2015). Psychosocial effects of perceived emotional synchrony in collective gatherings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 108, 711–729. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000014

Pelletier, P. (2018). The pivotal role of perceived emotional synchrony in the context of terrorism: challenges and lessons learned from the March 2016 attack in Belgium. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 48, 477–487. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12526

Pinquart, M., and Sorensen, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective WB in later life: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 15, 187–224. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.15.2.187

Pizarro, J. J., Cusi, O., Alfaro-Beracoechea, L., González-Burboa, A., Vera-Calzaretta, A., Carrera, P., et al. (2018). Asombro maravillado, temor admirativo o respeto sobrecogido: revisión teórica y Validación de una Escala de Asombro en Castellano. PsyCap 4:5776.

Postmes, T., Wichmann, L. J., van Valkengoed, A. M., and van der Hoef, H. (2018). Social identification and depression: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 117. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2508

Rubio, A., Mendiburo, A., Oyanedel, J. C., Benavente, L., and Paez, D. (2020). Relationship between the evaluation of the health system personnel by their users and their subjective well-being: a cross-sectional study. Medwave 20:e7958. doi: 10.5867/medwave.2020.06.7958

Russell, D. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale (version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 66, 20–40.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Sani, F., Herrera, M., Wakefield, J. R., Boroch, O., and Gulyas, C. (2012). Comparing social contact and group identification as predictors of mental health. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 51, 781–790. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2012.02101.x

Schiefer, D., and van der Noll, J. (2016). The essentials of social cohesion: a literature review. Soc. Indic. Res. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1314-5

Schwarzer, R., and Leppin, A. (1989). Social support and health: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Health 3:115. doi: 10.1080/08870448908400361

Smith, T. B., and Silva, L. (2011). Ethnic identity and WB of people of color: an updated meta-analysis. J. Counsel. Psychol. 58, 42–60. doi: 10.1037/a0021528

Stanley, P. J., Schutte, N. S., and Phillips, W. (2020). A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between basic psychological need satisfaction and affect. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 10:16. doi: 10.47602/jpsp.v5i1.210

Steffens, N. K., Haslam, A., Sebastian, Schuh, S. C., Jetten, J., and van Dick, R. (2016). A meta-analytic review of social identification and health in organizational contexts. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 21. doi: 10.1177/1088868316656701

Turner, J. B., and Turner, R. J. (2013). Social relations, social integration, and social support, in Handjournal of the Sociology of Mental Health, eds C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, and A. Bierman (Dordrecht: Springer), 341–356. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_17

Unanue, W., Gómez, M., Cortes, D., Oyanedel, J. C., and Mendiburo-Seguel, A. (2017). Revisiting the link between job satisfaction and life satisfaction: the role of basic psychological needs. Front. Psychol. 8:680. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00680

Wang, P., Chen, X., Gong, J., and Jacques-Tiura, A. J. (2014). Reliability and validity of the personal social capital scale 16 and personal social capital scale 8: two short instruments for survey studies. Soc. Indic. Res. 119, 1133–1148. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0540-3

Keywords: well–being, belongingness, social cohesion, social identity, social capital (culture), social integration, social support

Citation: Oyanedel JC and Paez D (2021) Editorial: Social Belongingness and Well-Being: International Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 12:735507. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.735507

Received: 02 July 2021; Accepted: 26 July 2021;

Published: 30 August 2021.

Edited and reviewed by: Anna Włodarczyk, Universidad Católica del Norte, Chile

Copyright © 2021 Oyanedel and Paez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Juan Carlos Oyanedel, anVhbi5veWFuZWRlbEB1bmFiLmNs

Juan Carlos Oyanedel

Juan Carlos Oyanedel Dario Paez

Dario Paez