- Department of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany

Background: In Germany, a large proportion of mentally ill offenders spends many years in a forensic psychiatric hospital. To ensure that the highly restrictive living conditions in these closed institutions meet patient needs, research must assess and analyze patient quality of life. For this purpose, we adapted the Measuring the Quality of Prison Life questionnaire to measure the quality of life in forensic psychiatric hospitals from the patient perspective. This study aimed to assess the reliability (internal consistency) and construct validity of the adapted questionnaire.

Methods: To evaluate the questionnaire, a one-time survey was carried out at 13 forensic psychiatric hospitals in Germany. Item characteristics and internal consistency of the scale and subscales were calculated and the factor structure was tested using confirmatory factor analysis. To test of responsiveness we compared the mean quality of life between the 13 hospitals and further investigated whether the patients' evaluation of quality of life is depending on age and duration of accommodation.

Results: The analysis of the psychometric properties revealed very good item characteristics and very good to excellent internal reliability. Construct validity was demonstrated. Patient's quality of life was significantly associated with age and duration of accommodation.

Discussion: The adapted Measuring the Quality of Prison Life questionnaire is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring quality of life in forensic psychiatric hospitals and can be used in the future to compare hospitals and identify the strengths and weaknesses of each.

Introduction

Detaining patients in forensic psychiatric hospitals has two objectives, i.e., to treat mental illness and reduce the risk of relapse. A large proportion of forensic psychiatric patients spends many years in a closed forensic psychiatric hospital (mean duration for patients with severe mental disorders: 4.6 years, range: 0.5–16.1 years; Dessecker, 2008). In these institutions, the daily routine is firmly structured and the opportunities for independent action are very limited. These narrow framework conditions sometimes block individuating personality maturation and limit therapeutic options. Therefore, to enable patients to develop positively, we need to assess their quality of life and adapt the living conditions to their needs.

Quality of life describes people's well-being and satisfaction with their current living conditions (Lehmann, 1983). According to the World Health Organization Quality of Life Workgroup (WHOQOL), quality of life is defined as “an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person's physical health, psychological state, personal beliefs, social relationships and their relationships to salient features of their environment” (Whoqol Group, 1995). Most authors consider quality of life as a multidimensional concept that includes both objective (e.g., health, income) and subjective indicators (e.g., satisfaction with social relations).

Experience from hospital practice shows, that patients evaluate their quality of life in forensic psychiatric hospitals quite differently. Some experience their detainment as unpleasant and negative, whereas others find the structured environment to be beneficial and protective. Given this potential range of subjective experiences, the present study aimed to develop and evaluate a questionnaire for mentally ill offenders that measures the quality of life in forensic psychiatric hospitals. The questionnaire “Measuring the Quality of Prison Life” (MQPL) by Liebling et al. (2011), which was designed for use in correctional facilities, served as a template. Liebling et al. used a bottom-up approach, i.e. they accompanied inmates in five different prisons for a year, had numerous conversations with them and thus gained insight into the issues that were relevant to them. From their observations at the grassroots level, they created a questionnaire with over 100 items, which was subsequently evaluated and validated in various prisoner populations (N = 1,147). In this way, Liebling's working group succeeded in identifying and statistically recording the parameters that were particularly important in the prisoners' daily lives. The questionnaire is now used worldwide and results are available from England, Spain, Norway, Sweden, Australia, Kosovo, and New Zealand (e.g., Leeson et al., 2015; Skar et al., 2019).

Liebling et al. found large differences between individual prisons with regard to prisoner's well-being and their current psychological distress (Liebling, 2009; Crewe et al., 2015). For example, some institutions are experienced as being more punitive than others. Significant correlations were also found between inmates' quality of life and the suicide rates in the respective institutions (Liebling et al., 2005). A study from Norway by Johnsen et al. (2011), examined the influence of prison size on inmates' evaluation of quality of life and found that they rated it most positively in prisons with fewer than 50 inmates (Johnsen et al., 2011). Skar et al. (2019) performed a study in a prison in Kosovo to investigate whether inmates' quality of life was associated with their mental health and the level of violence. They found a significant negative relationship between anxious symptoms, physical and psychological violence and quality of life (Skar et al., 2019).

Numerous studies have examined quality of life among prison inmates, and research on quality of life in forensic psychiatric hospitals is also making progress (Radoschewski, 2000; Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2002; Schalast et al., 2008; Vorstenbosch et al., 2014; Tonkin, 2016). However, only a small proportion of the studies focus on quality of life as a multidimensional construct that covers both objective living conditions and subjective well-being. Sampson et al. (2016) compared forensic psychiatric care in 18 European countries by conducting interviews with mental health experts. They concluded that improving the well-being and quality of life of long-term housed patients was essential for treatment (Sampson et al., 2016). Two studies from the Netherlands showed that patients' own assessment of quality of life and the way staff assess patients' quality of life diverge (Schel et al., 2015; de Vries et al., 2016) and Büsselmann et al. (2020) revealed that the social aspects of quality of life of forensic psychiatric patients are associated with suicidal thoughts, the severity of depressive symptoms and hopelessness.

The aims of the present study were threefold: First, the Measuring the Quality of Prison Life questionnaire (Liebling et al., 2011) should be translated into German and adapted to the living conditions of forensic psychiatric hospitals to assess the quality of life of forensic psychiatric patients, including adding items on patient-therapist relationships. Second, for the psychometric evaluation of our adapted questionnaire, a one-time survey was carried out at 13 forensic psychiatric hospitals. The reliability of the main scale and subscales should be determined using internal consistency and the construct validity should be tested by means of a confirmatory factor analysis. Third, to test of responsiveness, it should be investigated whether significant differences can be found between different forensic hospitals or between different patient groups (older vs. younger, patients with long and patients with short length of stay).

Materials and Methods

Sample

A total of 255 forensic psychiatric patients (25 women, 230 men) took part in the study; however the data of 25 patients were excluded from the analysis because too many values were missing. All patients were detained according to Section 63 (severe mental disorder, n = 81; 35%) or Section 64 (substance use disorder, n = 149; 65%) of the German penal code.

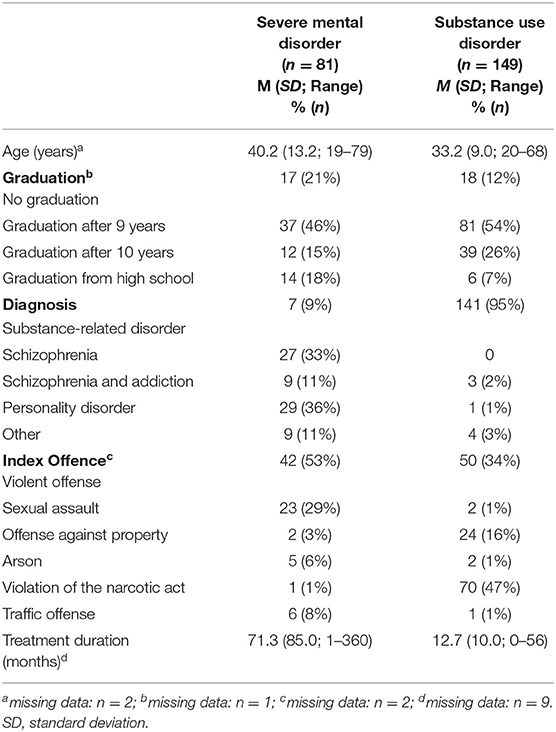

An overview of sociodemographic and forensic-psychiatric characteristics of the two subsamples of patients (i.e., those with severe mental disorders and those with substance use disorders) is shown in Table 1.

Assessment of Socio-Demographic, Hospital, and Legal Data

Patients were asked for the following information: gender, age, highest school leaving certificate, duration of actual detention, diagnosis, legal terms of detaining, index offense, and level of movement allowed.

Measuring the Quality of Life

With kind permission of the authors, we translated the MQPL questionnaire (Liebling et al., 2011) into German. The original questionnaire consists of 128 items and covers both positive and negative living conditions of inmates. Because the MQPL questionnaire is tailored to the needs of prison inmates, the items related to therapeutic help and support were inappropriate for forensic psychiatric patients and were omitted. Instead, we drew on our own prior work, the Questionnaire for Investigating Therapeutic Alliance in Forensic Setting (FTBF; Vasic et al., 2015). The FTBF takes into account the formal and infrastructural characteristics of forensic psychiatric hospitals. We adopted items on the patient-therapist relationship and satisfaction with the therapeutic process. The adapted version, named aMQPL, consisted of 73 items, which were assigned to 14 subscales: entry in forensic psychiatry, relationship with fellow inmates, relationship with caregivers, relationship with therapists, family contact, respect, fairness, transparency of procedures and decisions, safety, quality of accommodation, therapeutic options/personal development, suicide prevention, drug consumption and treatment of foreign patients. The items were answered on a five-point-Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree). To evaluate the questionnaire, we calculated the mean score for the subscales and the total score. The higher the respective mean score was, the more positive patients rated the specific aspects of their quality of life (reflected by the subscales) or their overall quality of life (reflected by the total score).

Procedure

From February to November 2018 we recruited N = 255 forensic patients in 13 out of 14 Bavarian (German) forensic hospitals. The patients were informed about the aim and procedure of the study and about the fact that neither participation nor non-participation would have any advantages or disadvantages with respect to their treatment. In addition, they were not offered either payment or other forms of compensation. Subsequently, they were asked to decide whether or not they were willing to participate in this study. If they agreed to participate, patients gave written informed consent and received a sheet with contact details of the research team. They were informed that they could withdraw their consent at any time. Thus, the study was performed in accordance with the criteria of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants completed the questionnaires in small groups in a separate room on the ward, and a research assistant was available to help.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 25 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Item characteristics were determined by means of item difficulties and item discriminations. Reliability was calculated via internal consistency analyses (Cronbachs' alpha). The factorial validity was examined with the help of a confirmatory factor analysis.

Analyses of variance were performed to test statistically significant differences between the 13 participating forensic psychiatric hospitals. The mean value of the respective aMQPL-subscale/total scale was used as the dependent variable; the independent variable was the affiliation to one of the 13 hospitals.

To test whether there are correlations between patients' age and quality of life, Spearman correlations were calculated separately for patients with a severe mental disorder and for patients with substance use disorders. To check if the duration of their accommodation (above and below the 50th percentile of the distribution of the mean duration) was associated with the assessment of quality of life, t-tests for independent groups were calculated for each aMQPL-subscale and the aMQPL-total scale.

Results

Psychometric Evaluation of the Questionnaire

For the interpretation of item characteristics and internal reliability, we followed the guidelines by Bühner (2011): The item difficulties (in percent) should cover as wide a range as possible (0–100), since extreme difficulties also allow differentiation in peripheral areas of the covered domains. The item discrimination index corresponds to the correlation coefficient between the item response i and the total scale score. The total scale value is calculated as the sum of all items without item i. Good item discrimination indices are greater than ri(t−i) = 0.30. Cronbach's alpha is a measure of the internal consistency of the scale or subscale. It indicates how strongly the individual items are related to each other. Cronbach's alpha should assume a value greater than r = 0.65.

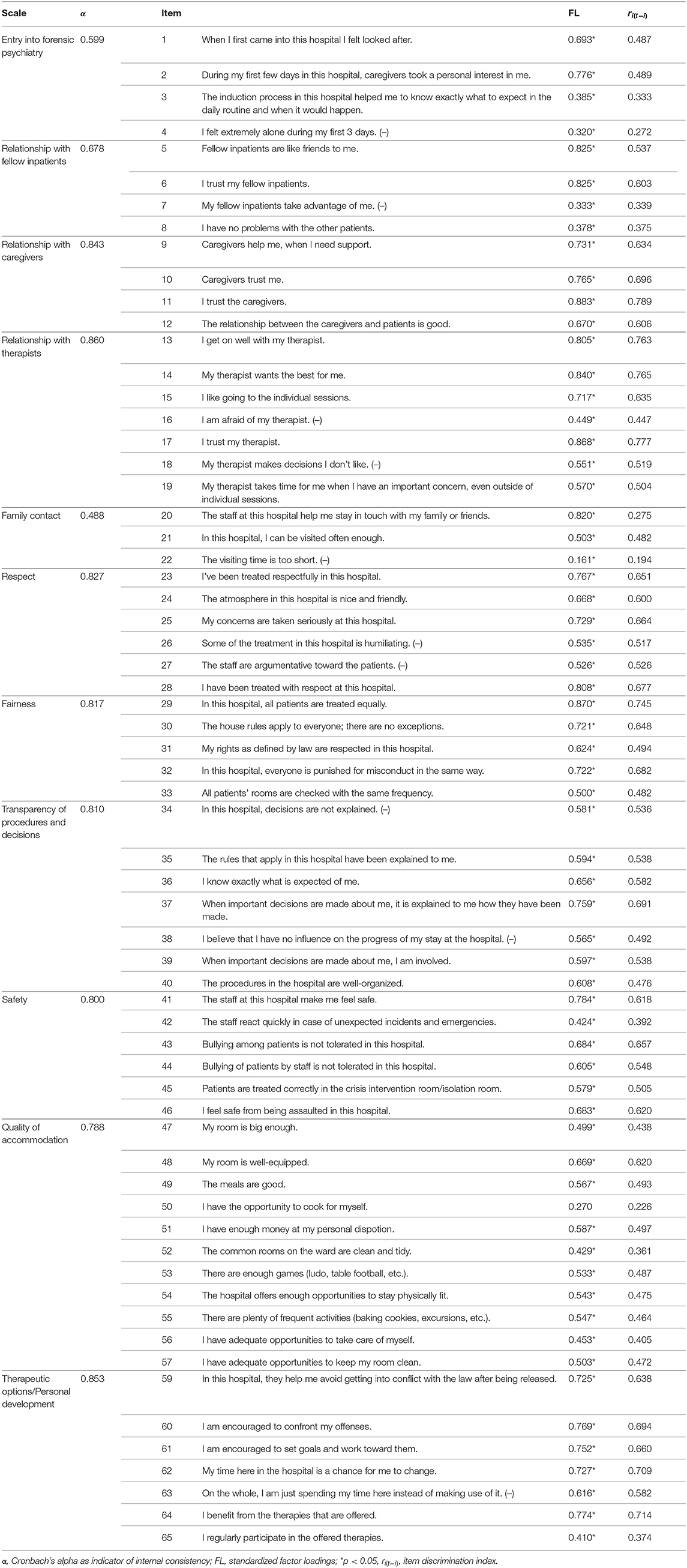

Nine items and the 3 related subscales were excluded due to insufficient internal consistencies (Cronbach's alpha: suicide prevention = 0.335; drug use = 0.308 and treatment of foreign patients = 0.013). The results of the evaluation of the 64 remaining items and 11 subscales can be found in Table 2. Item difficulties ranged between 33.8 and 64.6. The reliability of the total scale can be rated as excellent (Cronbach's alpha of the total score: r = 0.953).

Table 2. Item characteristics and reliabilities of the adapted measuring the quality of prison life questionnaire.

Factor structure was tested by confirmatory factor analysis and is given [Chi2(1897) = 3442.143; p < 0.001; Bollen-Stine bootstrap-corrected p = 0.008; RMSEA = 0.067; 90% confidence interval: 0.064–0.071; for interpretation: good models have values RMSEA ≤ 0.08]. Significant standardized factor loadings are listed in Table 2.

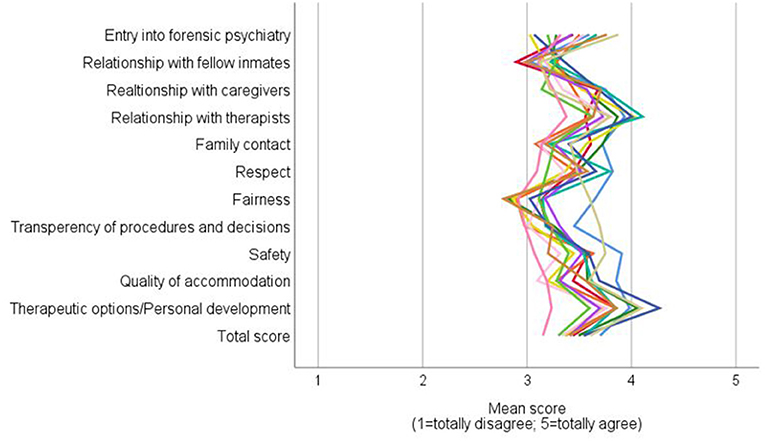

Test of Responsiveness: Differences Between Forensic Psychiatric Hospitals

As can be seen in Figure 1, significant differences were found between the 13 participating forensic psychiatric hospitals in the following subscales: entry into forensic psychiatry [F(12, 242) = 1.993; p = 0.026; part. Eta2 = 0.090], fairness [F(12, 241) = 1.982; p = 0.026; part. Eta2 = 0.090], quality of accommodation [F(12, 242) = 4.164; p < 0.001; part. Eta2 = 0.171] and therapeutic options/personal development [F(12, 241) = 1.870; p = 0.039; part. Eta2 = 0.085].

Figure 1. Mean values of the 13 participating Bavarian forensic psychiatric hospitals across the individual subscales and the total score of the aMOPL.

Test of Responsiveness: Associations Between Quality of Life and Patients' Age and Duration of Hospital Stay

For patients with severe mental disorders, the analyses further showed, that there was a significant negative correlation between the patients' age and the subscale family contact (Spearman's ρ = −0.222, p = 0.049). For patients with substance use disorders we found significant positive correlations between the patients' age and the subscales fairness (Spearman's ρ = 0.207, p = 0.011) and quality of accommodation (Spearman's ρ = 0.172, p = 0.036).

The duration of the hospital stay also influenced quality of life. Patients with severe mental disorders, who were accommodated in a forensic psychiatric hospital for 43 months or more rated entry in forensic psychiatry [t(70) = −2.622; p = 0.011; dCohen = −0.627], relationship with caregivers [t(70) = −2.107; p = 0.039; dCohen = −0.504], transparency of procedures and decisions [t(70) = −3.034; p = 0.003; dCohen = −0.725] and therapeutic options/personal development [t(70) = −2.257; p = 0.027; dCohen = −0.540] more positive than patients who were accommodated for a shorter period of time (< 43 months). Patients with substance use disorders who were accommodated for 12 or more months rated the quality of life more negatively than patients with a shorter length of stay, total score [t(146) = 2.083; p = 0.039; dCohen = 0.345]. The same applied to the subscales relationships with therapists [t(128, 838) = 2.301; p = 0.023; dCohen = 0.405], respect [t(146) = 2.361; p = 0.020; dCohen = 0.391], and transparency of procedures and decisions [t(146) = 3.153; p = 0.002; dCohen = 0.522].

Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the psychometric properties of a translated and adapted version of the Measuring the Quality of Prison Life questionnaire (Liebling et al., 2011). The analysis of the psychometric properties of the adapted German questionnaire revealed good to excellent values for reliability and a confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the factor structure.

We found significant differences between the participating hospitals in the subscales entry into forensic psychiatry, fairness, quality of accommodation and therapeutic options/personal development. Because the aMQPL questionnaire allows the current quality of life at individual forensic psychiatric hospitals to be assessed, the aMQPL can be used in the future both to inform staff if any areas still need to be optimized and to compare conditions between hospitals.

Furthermore, our study shows that the age of patients in forensic psychiatric hospitals affects their quality of life. Young patients with substance use disorders feel treated more unfair than older patients. This finding gives rise to the question whether younger patients' concerns may be taken not so serious than older patients' concerns. In addition, young patients with substance use disorders rate the quality of accommodation significantly more negatively than older patients. One possible explanation for this difference may be that the living conditions and recreational opportunities available to young patients are not age-appropriate.

Patients with severe mental disorders rate their quality of life more positively the longer they have been detained in a forensic hospital (>3.5 years). The reason for that could be a therapeutically unintentional habituation to the forensic hospital. Being locked up for a long time creates helplessness, and over the years patients may become increasingly worried that they will not be able to cope with the practical demands of life outside the forensic hospital. Therapists and caregivers can try to reverse this effect of hospitalization by carefully preparing patients for discharge and relieving their worries about their new life “on the outside.”

In conclusion, a high quality of life should be ensured in forensic psychiatric hospitals to promote the best possible course of therapy. And the aMQPL appears to be a suitable self-assessment instrument for evaluating patients' quality of life. The developed questionnaire can be used with two different intentions: (a) to monitor the current status and further development of an individual forensic psychiatric hospital or (b) as an instrument to compare different forensic psychiatric hospitals with each other.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the sample consisted only German forensic psychiatric patients, so the results cannot be generalized to general psychiatric patients or forensic patients from other countries. Second, self-reported data can result in various biases.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of the University Ulm, Germany. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MD, JS, and MB designed the study. MB collected the data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. MB, JS, and ML analyzed the data. MB, JS, and LT interpreted the data. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis, contributed to read, and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Bavarian State Ministry for Family, Labor and Social Affairs, Germany.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jacquie Klesing, Medical-Editor, and Translator and Board-certified Editor in the Life Sciences (ELS), for editing assistance with the manuscript.

References

Bühner, M. (2011). Einführung in die Test-und Fragebogenkonstruktion. München: Pearson Deutschland GmbH.

Büsselmann, M., Nigel, S., Otte, S., Lutz, M., Franke, I., Dudeck, M., et al. (2020). High quality of life reduces depression, hopelessness, and suicide ideations in patients in forensic psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry 10:1014. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01014

Crewe, B., Liebling, A., and Hulley, S. (2015). Staff-prisoner relationships, staff professionalism, and the use of authority in public-and private-sector prisons. Law Soc. Inquiry. 40, 309–344. doi: 10.1111/lsi.12093

de Vries, M. G., Brazil, I. A., Tonkin, M., and Bulten, B. H. (2016). Ward climate within a high secure forensic psychiatric hospital: perceptions of patients and nursing staff and the role of patient characteristics. Arch. Psychiatric Nurs. 30, 342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.12.007

Dessecker, A. (2008). Lebenslange Freiheitsstrafe, Sicherungsverwahrung und Unterbringung in einem psychiatrischen Krankenhaus: Dauer und Gründe der Beendigung im Jahr 2006. Wiesbaden: Kriminologische Zentralstelle e.V.

Johnsen, B., Granheim, P. K., and Helgesen, J. (2011). Exceptional prison conditions and the quality of prison life: prison size and prison culture in Norwegian closed prisons. Europ. J. Crimin. 8, 515–529. doi: 10.1177/1477370811413819

Leeson, S., Rynne, J., Smith, C., and Adams, Y. (2015). Incarcerating aboriginal and torres strait islander women in australia: finding a balance in defining the ‘just prison'. Austral. Indigen. Law Rev. 19, 76–96.

Lehmann, A. (1983). The well-being of chronic mental patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 40, 369–373. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790040023003

Liebling, A. (2009). “Moralische Leistung und Auswirkungen von Gefangensch,” in Neue Kriminalpolitik 14–20. doi: 10.5771/0934-9200-2009-1-14

Liebling, A., Durie, L., Stiles, A., and Tait, S. (2005). “Revisiting prison suicide: the role of fairness and distress,” in The Effects of Imprisonmen,t 209–231.

Liebling, A., Hulley, S., and Crewe, B. (2011). “Conceptualising and measuring the quality of prison life,” in The SAGE Handbook of Criminological Research Methods 358–372. doi: 10.4135/9781446268285.n24

Nieuwenhuizen, C. V., Schene, A. H., and Koeter, M. W. J. (2002). Quality of life in forensic psychiatry: an unreclaimed territory? Int. Rev. Psychiatry 14, 198–202. doi: 10.1080/09540260220144993

Radoschewski, M. (2000). Gesundheitsbezogene lebensqualität–konzepte und maße. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz. 43, 165–189. doi: 10.1007/s001030050033

Sampson, S., Edworthy, R., Vollm, B. A., and Bulten, E. (2016). Long-term forensic mental health services: an exploratory comparison of 18 European countries. Int. J. Forens. Mental Health 15, 333–351. doi: 10.1080/14999013.2016.1221484

Schalast, N., Redies, M., Collins, M., Stacey, J., and Howells, K. (2008). EssenCES, a short questionnaire for assessing the social climate of forensic psychiatric wards. Crim. Behav. Mental Health 18, 49–58. doi: 10.1002/cbm.677

Schel, S. H. H., Bouman, Y. H. A., and Bulten, B. H. (2015). Quality of life in long-term forensic psychiatric care: comparison of self-report and proxy assessments. Arch. Psychiatric Nurs. 29, 162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.01.004

Skar, M., Lokdam, N., Liebling, A., Muriqi, A., Haliti, D., Rushiti, F., et al. (2019). Quality of prison life, violence and mental health in dubrava prison. Int. J. Prisoner Health 15, 262–272. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-10-2017-0047

Tonkin, M. (2016). A review of questionnaire measures for assessing the social climate in prisons and forensic psychiatric hospitals. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Crim. 60, 1376–1405. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15578834

Vasic, N., Dudeck, M., Knein, A. M., Rasche, K., Mentel, R., Streb, J., et al. (2015). Fragebogen zur therapeutischen Beziehung in der Forensik (FTBF): ergebnisse einer Pilotstudie. Fortschritte der Neurol. Psychiatrie 83, 686–693. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-110391

Vorstenbosch, E. C., Bouman, Y. H., Braun, P. C., and Bulten, E. B. (2014). Psychometric properties of the forensic inpatient quality of life questionnaire: quality of life assessment for long-term forensic psychiatric care. Health Psych. Behav. Med. Open Access J. 2, 335–348. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2014.894890

Keywords: quality of life, well-being, forensic psychiatry, mentally ill offenders, living conditions

Citation: Büsselmann M, Titze L, Lutz M, Dudeck M and Streb J (2021) Measuring the Quality of Life in Forensic Psychiatric Hospitals. Front. Psychol. 12:701231. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.701231

Received: 27 April 2021; Accepted: 07 June 2021;

Published: 09 July 2021.

Edited by:

Heng Choon Chan, City University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReviewed by:

Peter Bartlett, University of Nottingham, United KingdomDaniel Tan Lei Shek, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

Copyright © 2021 Büsselmann, Titze, Lutz, Dudeck and Streb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael Büsselmann, bWljaGFlbC5idWVzc2VsbWFubkBia2gtZ3VlbnpidXJnLmRl

Michael Büsselmann

Michael Büsselmann Larissa Titze

Larissa Titze Maximilian Lutz

Maximilian Lutz Manuela Dudeck

Manuela Dudeck Judith Streb

Judith Streb