- 1Beijing Key Laboratory of Learning and Cognition, School of Psychology, Capital Normal University, Beijing, China

- 2Beijing Xuanwu Foreign Language Experimental School, Beijing, China

Due to the close relationship among intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, regulatory focus, and creativity revealed by previous literature, intrinsic/extrinsic motivation may play a mediating role between regulatory focus and creativity. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between regulatory focus and creativity by combining intrinsic/extrinsic motivation. In this study, senior high school students (n = 418) completed the Regulatory Focus Questionnaire, the Working Preference Inventory, the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet, and the Kirton Adaption–Innovation Inventory. The correlation analysis showed that both promotion and prevention focus positively correlated with intrinsic motivation; intrinsic motivation and promotion focus positively correlated with creativity personality and innovative-adaptive cognitive style; and extrinsic motivation and prevention focus negatively correlated with innovative–adaptive cognitive style. Furthermore, a path model showed that promotion focus positively predicted creativity through the mediation of intrinsic motivation. In general, our study suggests that intrinsic motivation plays a mediating role between promotion focus and creativity. Our results complement those of previous studies and serve as inspiration for the cultivation of creativity in classroom or enterprise settings.

Introduction

Creativity plays an increasingly important role in environmental adaptation from both individual and organizational perspectives in the increasingly changing world. Previous studies have revealed that both regulatory focus and intrinsic/extrinsic motivation have a significant impact on creativity (Amabile, 1983; Guo et al., 2000; Eisenberger and Rhoades, 2001; Lam and Chiu, 2002; Herman and Reiter-Palmon, 2011; Bittner and Heidemeier, 2013; Sacramento et al., 2013; Tang et al., 2015); however, it remains unclear whether intrinsic/extrinsic motivation plays a mediating role between regulatory focus and creativity. Thus, the present study attempted to examine the relationship between regulatory focus and creativity in conjunction with intrinsic/extrinsic motivation.

The regulatory focus theory describes how individuals achieve goals through self-regulation (Higgins, 1997). Higgins (1997) distinguished between two kinds of regulatory focus, i.e., promotion focus and prevention focus; the former reflects an inclination toward hope, aspiration, and accomplishment, whereas the latter reflects an inclination toward security, safety, and responsibility. Individuals who are promotion focused pay more attention to information related to positive outcomes, and they prefer eager strategies to obtain gains; in contrast, individuals who are prevention focused usually concentrate more on information related to negative outcomes, and they prefer vigilant strategies to avoid possible losses (Higgins et al., 2001). The literature on the relationship between regulatory focus and creativity has revealed that promotion focus is positively correlated with creativity, while prevention focus is negatively correlated with creativity (Lam and Chiu, 2002; Herman and Reiter-Palmon, 2011; Bittner and Heidemeier, 2013; Sacramento et al., 2013). For example, Friedman and Förster (2001) found that compared with prevention focus, promotion focus is more conducive to producing creative thinking and creative ideas. Researchers have also found that promotion focus prompts people to seek more solutions during problem solving, thus, improving the fluency of idea generation in creative tasks (Lam and Chiu, 2002). Jin et al. (2016) reported that promotion focus could positively predict creativity, while prevention focus negatively predicted creativity. This relation may be explained by the impact of regulatory focus on attention and the cognitive process (Bittner and Heidemeier, 2013; Sacramento et al., 2013). Promotion focus can expand an individual’s attention and is conducive to the acquisition of more extensive cognitive elements, which benefits fluency and flexibility (Derryberry and Tucker, 1994; Förster et al., 2006). To sum up, promotion focus is positively associated with creativity, while prevention focus is negatively associated with creativity.

Intrinsic motivation is one of the most important predictors of creativity. Intrinsic/extrinsic motivation is one of the most basic distinctions in the field of psychology; the former refers to doing something for the sake of personal interest and enjoyment, while the latter refers to doing something for a reward or some kind of attractive outcome (Deci, 1975; Collins and Amabile, 1999). The relationship between intrinsic/extrinsic motivation and creativity has been of interest to researchers since the 1990s. The literature has consistently shown that intrinsic motivation is conducive to creativity in both Western and Eastern populations (Amabile, 1983; Dong, 1993; Yang and Zhang, 2004; Cooper and Jayatilaka, 2006; Prabhu et al., 2008). When driven by personal interest in a task, individuals are more likely to spend considerable time and effort exploring various or new ways to complete the task and are less likely to accomplish it through the most direct and typical means. Therefore, intrinsic motivation is more conducive to creativity. Regarding the relationship between extrinsic motivation and creativity, previous studies obtained inconclusive results. Some studies have reported that creativity might be reduced by rewards (Amabile, 1983; Dong, 1993; Yang and Zhang, 2004), whereas other studies have suggested that extrinsic motivation could be conducive to creativity (Collins and Amabile, 1999; Eisenberger and Rhoades, 2001; Xue et al., 2001; Cooper and Jayatilaka, 2006). In addition, some studies have reported that there was no significant relation between extrinsic motivation and creativity (Guo et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2015). More recently, Amabile and Pratt (2016) brought about the concept of synergistic extrinsic motivation and insisted that some kinds of extrinsic motivators can show a positive effect on intrinsic motivation and creativity. Thus, not only is intrinsic motivation conducive to creativity, but informational or enabling extrinsic motivation can also be conducive to creativity, especially if initial levels of intrinsic motivation are high; however, controlling extrinsic motivation is detrimental to creativity (Amabile and Pratt, 2016). Similarly, Fischer et al. (2019) also revealed that extrinsic motivators such as relational rewards may have a positive effect on intrinsic motivation and creativity, while extrinsic motivators such as transactional rewards may have no effect on intrinsic motivation and creativity. Therefore, intrinsic motivation shows a positive effect on creativity, while the effect of extrinsic motivation is far more complex.

The previous literature has also revealed a close relationship between regulatory focus and intrinsic/extrinsic motivation. For example, Smith et al. (2009) found that promotion focus could increase intrinsic motivation; specifically, promotion-focused individuals not only view a boring task as more interesting but also put forth the effort to make it more interesting. Similarly, Li et al. (2016) argued that promotion-focused persons prefer tactics that produce desirable results, and they are more likely to be driven by autonomous motivation, which is closer to the intrinsic motivation end of the self-determination continuum of Deci and Ryan (1985); in contrast, prevention-focused persons prefer tactics that allow them to avoid undesirable results, and they are more likely to be driven by controlling motivation, which is closer to the extrinsic motivation end of the aforementioned self-determination continuum. Furthermore, Vaughn’s recent need-support model (Vaughn, 2016a) emphasized the close relation between self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000) and regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997, 1998). Vaughn (2016b) found that when pursuing promotion-focused goals, people experience more intrinsic motivation and identified motivation (“somewhat intrinsic motivation,” Ryan and Deci, 2000), whereas when pursuing prevention-focused goals, they experience more extrinsic motivation and introjected motivation (“somewhat extrinsic motivation,” Ryan and Deci, 2000). In addition, Vaughn (2016a) reported that compared with prevention focus, promotion focus leads to higher satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs; according to the self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000; Vansteenkiste and Ryan, 2013), high satisfaction of psychological needs promotes intrinsic motivation. Thus, promotion focus might indirectly improve intrinsic motivation through the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs. In short, promotion focus shows a closer association with intrinsic motivation than prevention focus.

Regarding the relationship between regulatory focus and creativity, there have been some studies on the underlying mechanism. For example, Baas et al. (2008) found that the interaction between mood activation level and its associated regulatory focus predicts creativity; specifically, high-activating and promotion-focused mood improves creativity, while high-activating and prevention-focused mood inhibits creativity. Further research (Baas et al., 2011) revealed that regulatory closure (whether the goal is attained or not) may moderate the relation between regulatory focus and creativity. Indeed, only in the closure-present condition (goal attained) did the promotion focus group show higher creativity than the prevention focus group, while no difference was found between two foci in the closure-absent condition (goal not attained); furthermore, the activation level mediated the relation between the closure × focus interaction and creativity.

However, questions remain. First, some of these studies (for example, Baas et al., 2008) focused on the relation between mood and creativity, viewing the regulatory focus as a moderator or mediator variable between them, rather than focused on the relation between regulatory focus and creativity. Second, previous literature has investigated the moderating effect underlying the regulatory focus-creativity link but has not probed the mediating variable between regulatory focus and creativity; thus, we know little about the path through which regulatory focus influences creativity. Third, previous findings on the relation between regulatory focus and creativity were mainly obtained among undergraduate students [the only exception being the research of Jin et al. (2016)]; thus, it is not clear whether the conclusions can be generalized to other age groups such as high school students, who are in the critical developmental period for thinking and creativity.

Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the relationship between regulatory focus and creativity in conjunction with intrinsic/extrinsic motivation among high school students, with a focus on whether intrinsic/extrinsic motivation mediates the relationship between regulatory focus and creativity. Based on the aforementioned close relationship among regulatory focus, intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, and creativity, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Promotion focus is positively related to creativity, while prevention focus is negatively related to creativity.

Hypothesis 2: Intrinsic motivation is positively correlated with creativity, while extrinsic motivation is negatively correlated with creativity.

Hypothesis 3: Intrinsic motivation is positively correlated with promotion focus and negatively correlated with prevention focus, while extrinsic motivation is positively correlated with prevention focus and negatively correlated with promotion focus.

Hypothesis 4: Regulatory focus predicts creativity through the mediation of intrinsic/extrinsic motivation.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

A total of 418 senior high school students (43% male; Mage = 16.26, SD = 0.67, range = 15–18 years) in Beijing, China, participated in this study. Among the participants, 54% were in senior grade 7 (n = 224), and 46% were in senior grade 8 (n = 194). The survey was administered in a classroom setting. The participants completed the Regulatory Focus Questionnaire, the Working Preference Inventory, the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet, and the Kirton Adaption–Innovation Inventory successively. All participants were given the option to not participate in the survey and to withdraw from the survey at any time without consequence. After finishing all the questionnaires, they were thanked and compensated with a stationery set valued at approximately ¥10 (approximately $1.40).

Instruments

Regulatory Focus Questionnaire

The Regulatory Focus Questionnaire (Higgins et al., 2001) consists of a promotion focus subscale (six items; e.g., “How often have you accomplished things that got you “psyched” to work even harder?”) and a prevention focus subscale (five items; e.g., “Did you get on your parents’ nerves often when you were growing up?”). The participants responded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). In this study, the alphas of the two subscales were 0.73 and 0.72.

Working Preference Inventory

The Working Preference Inventory (Amabile et al., 1994) consists of an intrinsic motivation subscale (15 items; e.g., “I want to find out how good I really can be at my work”) and an extrinsic motivation subscale (15 items; e.g., “I am strongly motivated by the recognition I can earn from other people”). The participants indicated their agreement or disagreement on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this study, the alphas of the intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation subscales were 0.75 and 0.70, respectively.

Williams Creativity Assessment Packet

The Williams Creativity Assessment Packet (Chinese version, Lin and Wang, 1997) consists of four dimensions: curiosity (14 items; e.g., “I like to do a lot of new things”), complexity (12 items; e.g., “I often do things in the same way, and I don’t like to look for other new methods”), risk-taking (11 items; e.g., “It’s fun to try new games and activities”), and imagination (13 items; e.g., “I like to imagine that I will become an artist, a musician, or a poet someday”). The participants indicated their choices on a three-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (certainly false) to 3 (certainly true). In this study, the total alpha was 0.86.

The Kirton Adaption–Innovation Inventory

The Kirton Adaption–Innovation Inventory (Kirton, 1976) consists of three subscales: originality (13 items; e.g., “Copes with several new ideas at the same time”), efficiency (seven items; e.g., “Is methodical and systematic”), and rule (12 items; e.g., “Never seeks to bend or break the rules”). The participants responded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (certainly false) to 5 (certainly true). In this study, the alphas of the three subscales were 0.77, 0.74, and 0.75, respectively.

Since creativity comprises different aspects, such as creative thinking aspects (i.e., cognitive aspects of creative information processing) and creative personality aspects (i.e., the personal inclinations that are vital to creative activities) (Zhang et al., 2007), two measures were combined in the present study, the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet score was the indicator of creative personality, and the Kirton Adaption–Innovation Inventory score was the indicator of innovative-adaptive cognitive style.

Results

Common Method Bias Test

We adopted Harman’s single-factor analysis to examine possible common method bias. The results suggested that there were 27 factors with characteristic roots greater than 1, with a total contribution rate of 62.59%; the variation contribution rate of the first factor was 11.95%. Thus, there was no severe common method bias in this study.

Difference Tests

A t-test showed that there was a significant gender difference in prevention focus (t = 2.51, p = 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.25) and that female participants (M = 3.57, SD = 0.65) were more prevention focused than were male participants (M = 3.40, SD = 0.66). Moreover, there was a significant grade difference in intrinsic motivation (t = 2.102, p = 0.036, Cohen’s d = 0.21); the participants in grade 7 (M = 3.80, SD = 0.45) were more intrinsically motivated than those in grade 8 (M = 3.70, SD = 0.46).

Correlation Analysis

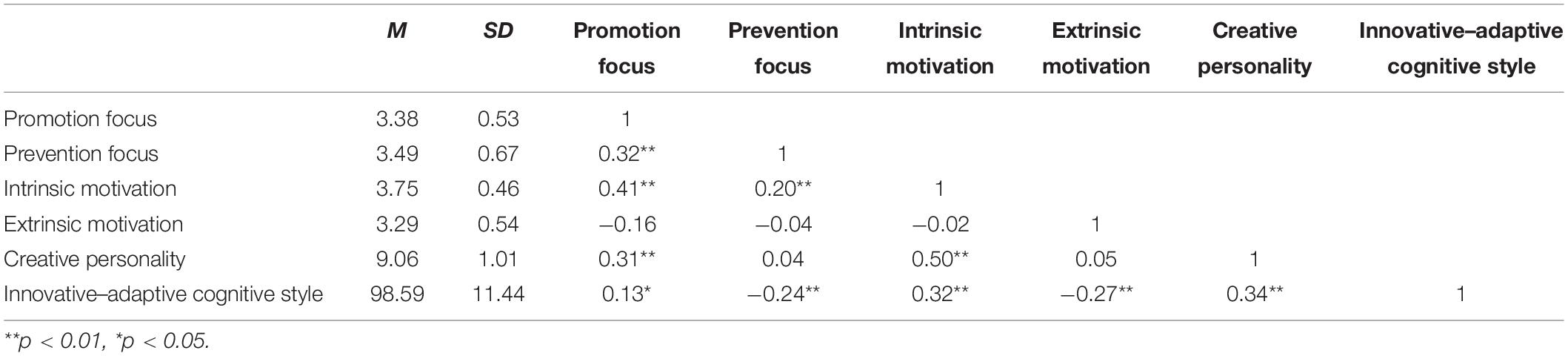

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and the correlation coefficients between variables. Intrinsic motivation and promotion focus were both positively correlated with two indicators of creativity, and extrinsic motivation and prevention focus were both negatively correlated with adaptive–innovative cognitive style. In addition, promotion focus and prevention focus were both positively correlated with intrinsic motivation; however, neither type of focus was significantly correlated with extrinsic motivation.

Measurement Model

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted for promotion focus, prevention focus, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and creativity. The item parceling method was used for the former four variables, in which we used a factorial algorithm (Rogers and Schmitt, 2004) to create three parcels with three to five items in each parcel, and creativity was measured by the Williams Creativity Assessment Packet score and Kirton Adaption–Innovation Inventory score. The model fits the data moderately well, χ2 (58, N = 418) = 126.95, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.92, and RMSEA = 0.053. All indicators loaded significantly (ps < 0.001) on each latent variable, and the standardized factor loadings were between 0.33 and 0.85.

Path Model

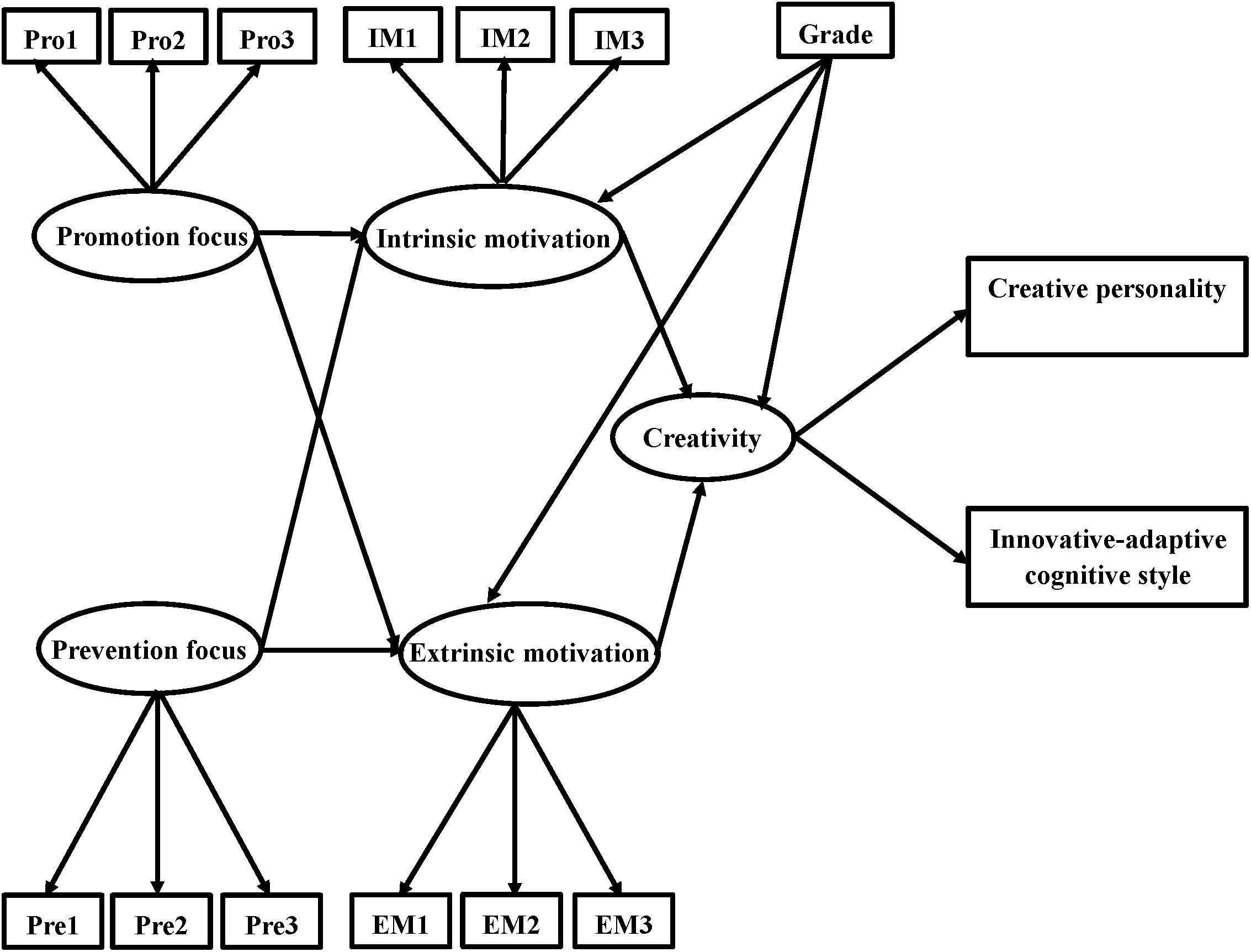

Based on the aforementioned hypotheses, we proposed the hypothesized model depicted in Figure 1, in which promotion focus and prevention focus both predicted creativity through the mediation of intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation, and the effect of grade was controlled because of the significant difference in intrinsic motivation between grades.

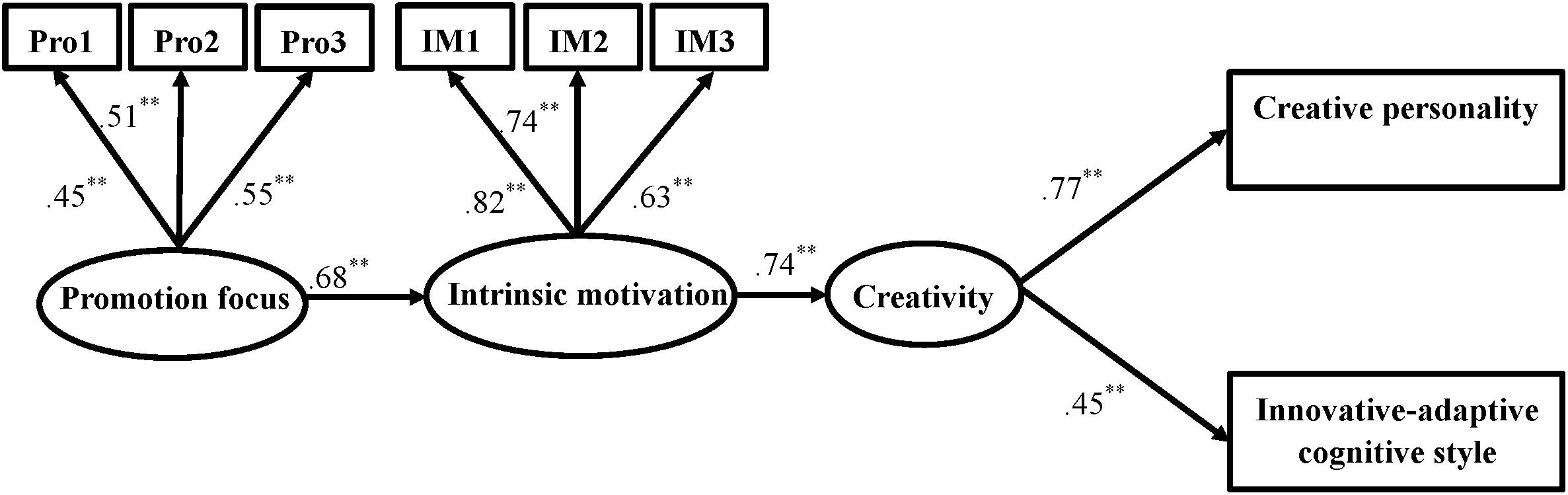

The hypothesized model was tested using structural equation modeling (SEM) with Mplus. The SEM results revealed that the fit was inadequate, χ2 (81, N = 418) = 311.71, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.83, TLI = 0.78, RMSEA = 0.083. In addition, as shown in Figure 2, some paths in the hypothesized model were not significant. Both the fit indexes and path coefficients indicated that further adjustment of the model was necessary.

Figure 2. The hypothesized model of regulatory focus, motivation, and creativity with path coefficients. **p < 0.01; ⇢: indicates path that was hypothesized but not significant.

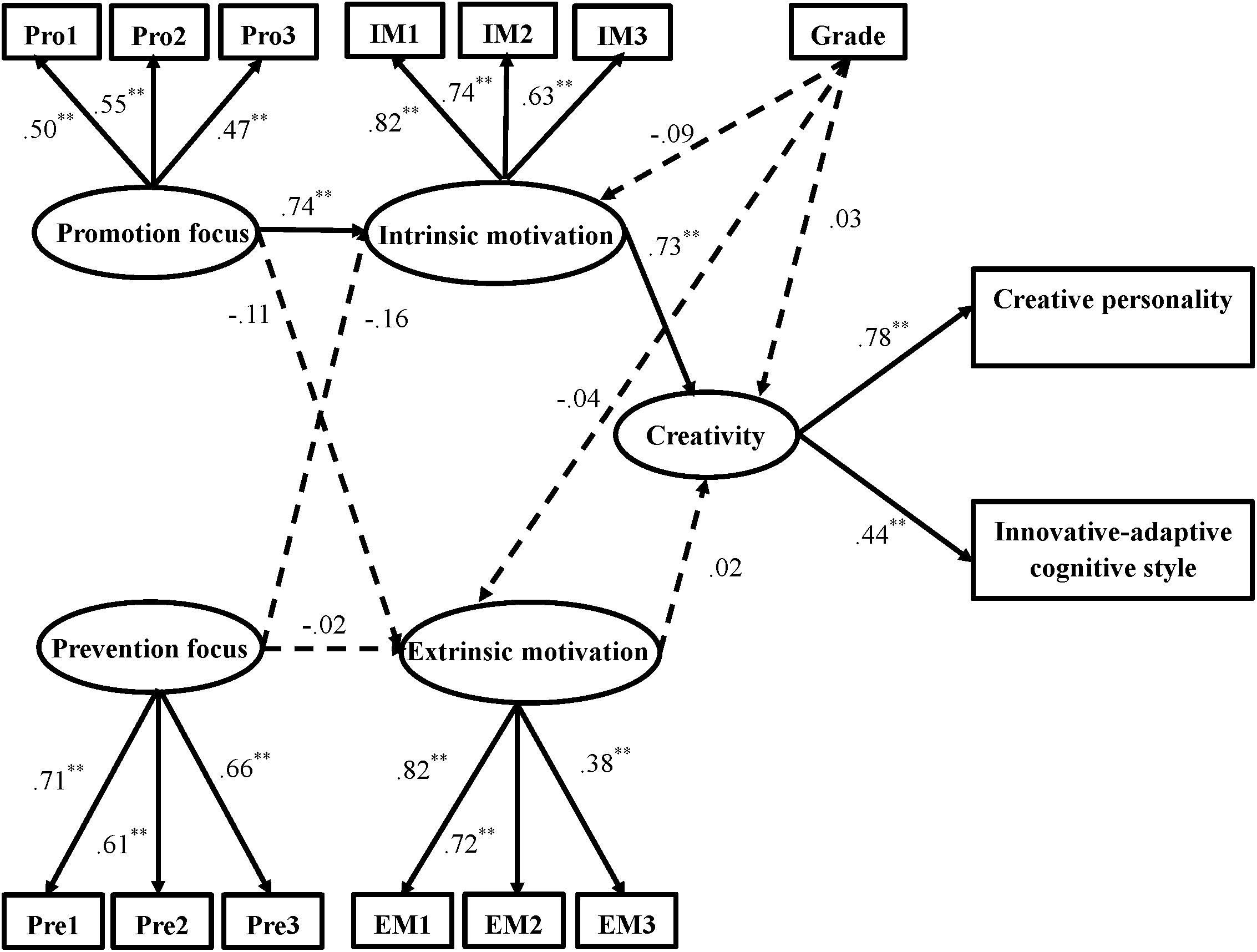

The hypothesized model was adjusted according to the modification indexes, and all the non-significant paths were removed from the model, i.e., the paths from grade to intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and creativity, the path from prevention focus to extrinsic motivation, the path from prevention focus to intrinsic motivation, the path from promotion focus to extrinsic motivation, and the path from extrinsic motivation to creativity. Thus, we obtained the modified model shown in Figure 3. The modified model fits the data well, χ2 (18, N = 418) = 43.40, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, and RMSEA = 0.058.

The modified model indicated that promotion focus positively predicted intrinsic motivation, which, in turn, positively predicted creativity. Thus, taken together, the results show that promotion focus positively predicted creativity through the mediation of intrinsic motivation. Moreover, we examined the mediating role of intrinsic motivation by calculating the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the effects of promotion focus on creativity through bootstrapping with 1,000 random samples. The indirect effect of promotion focus on creativity was 0.50, and the 95% CI did not include zero (95% CI = [0.361, 0.648]), which suggests that the mediating effect was significant.

Discussion

Gender Differences on Regulatory Focus

In our study, female participants were more prevention focused than were male participants. Higgins (1997) argued that regulatory focus is closely related to parenting behavior; if parents prefer the satisfaction of growth needs, children are more likely to become promotion focused, whereas if parents prefer the satisfaction of security needs, children tend to become prevention focused. In China, parents traditionally show differential rearing styles for daughters and sons (Xu, 2008; Zeng, 2010). Specifically, parents are more concerned with the satisfaction of the growth needs of sons, encouraging boys’ exploration and innovation; in contrast, they are more concerned with the satisfaction of the security needs of daughters, guiding girls to follow rules and to protect their personal safety (Xu, 2008). As a result, in Chinese participants, girls might be more prevention focused than boys.

The Relationship Between Regulatory Focus and Creativity

Our study revealed a positive association between promotion focus and creativity, and this result is consistent with previous research (e.g., Friedman and Förster, 2001; Lam and Chiu, 2002; Jin et al., 2016; Lin, 2017). The reason for this finding may be that promotion-focused individuals are inclined to explore more strategies to solve problems, which will result in the generation of more creative ideas (Lam and Chiu, 2002). In addition, promotion focus is closely related to an integrated, global information processing style, which helps activate more cognitive elements and further benefits the establishment of more and unusual connections among cognitive elements (Semin et al., 2005; Sacramento et al., 2013). Furthermore, a previous study indicated that people who are promotion focused are more inclined to invest in risk-taking behavior than those who are prevention focused (Hamstra et al., 2011). Sacramento et al. (2013) also reported that people who are promotion focused are more likely to choose a risky scheme, which, in turn, enhances creativity, whereas people who are prevention focused tend to choose safe and conservative regimes, which inhibits creativity. Additionally, regulatory focus was closely related to openness. For example, studies have found that openness is positively associated with promotion focus and negatively connected with prevention focus because promotion-focused individuals are less risk averse and enjoy changing and exploring the world, whereas people who are prevention focused are inclined to follow the rules and avoid unknown or unpredictable results (Vaughn et al., 2008; Yen et al., 2011; Lanaj et al., 2012).

On the other hand, in our study, regarding the relation between prevention focus and creativity, SEM revealed no significant results. In the previous literature, some studies have supported the negative effect of prevention focus on creativity (Baas et al., 2008; Bittner and Heidemeier, 2013); however, inconsistent results have been reported. For example, a meta-analysis revealed that prevention-focused states lead to similar levels of creativity as promotion-focused states if the task goal has not been reached (Baas et al., 2011). Another study suggested that regulatory focus and the evaluation subtype interact to influence creativity; promotion focus might improve creativity in information evaluation situations, whereas prevention focus might benefit creativity in controlling evaluation situations (Wang et al., 2017). In addition, the effect of regulatory focus on creativity might depend on situational factors, such as task demand (Li, 2015); promotion focus might benefit creativity under high task demand, while prevention focus might benefit creativity under low task demand. Thus, although researchers have argued that prevention focus might be harmful to creativity due to the associated sensitivity to negative outcomes (Lam and Chiu, 2002), the preference for vigilant strategies (Sacramento et al., 2013), and the preference for a local processing style (Semin et al., 2005; Sacramento et al., 2013), the effects of prevention focus are more complex than the effects of promotion focus and should be discussed in greater detail in future research.

The Relationship Between Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivation and Creativity

Our study showed that intrinsic motivation was positively associated with creativity, and this result is consistent with previous studies (Amabile, 1983; Dong, 1993; Yang and Zhang, 2004). Higher intrinsic motivation can expand an individual’s attention and cognition and stimulate associations between ideas, which is beneficial to fluency and the flexibility of ideas (Grant and Berry, 2011). In addition, researchers have argued that individuals with high intrinsic motivation are more inquisitive, adventurous, and cognitively flexible and show high persistence in the face of obstacles (Shalley et al., 2004); therefore, intrinsic motivation facilitates the production of original and unusual thoughts.

However, regarding the relationship between extrinsic motivation and creativity, SEM showed that there was no significant path between them, and this result is consistent with studies by Guo et al. (2000) and Tang et al. (2015). As mentioned in the “Introduction” section, the existing literature on the relationship between extrinsic motivation and creativity has not reached a consistent conclusion, and positive, negative, and non-significant results have been reported. We postulate that both the inconsistency of the results and the non-significant results may be explained by the existence and effect of some moderator variables. Research has suggested that the relationship between competitiveness level and creativity differs between a closed group (whose members do not change) and an open group (in which new members join and original members leave) (Baer et al., 2010). Conti et al. (2001) also found that competition had different effects on males and females, improving creativity for boys but reducing creativity for girls, because boys view competition as challenging and exciting, but girls feel controlled under conditions of competition (Conti et al., 2001). More closely related to our study, recent work by Amabile and Pratt (2016) suggested that synergistic extrinsic motivation can be conducive to creativity, while controlling extrinsic motivation would undermine creativity. Fischer et al. (2019) also revealed that relational rewards and transactional rewards show different effects on intrinsic motivation and creativity. Earlier studies of Ryan et al. (1983) also found that controlling extrinsic motivation inhibits intrinsic motivation, while informational extrinsic motivation improves intrinsic motivation. Thus, the relationship between extrinsic motivation and creativity may depend on the different types of extrinsic motivation. In our study, the items in the instruments of extrinsic motivation involve competition, evaluation, recognition, money or other tangible incentives, and constraint by others (Amabile et al., 1994), which means that the extrinsic motivation measured by it was a composition of synergistic extrinsic motivation, informational extrinsic motivation, and controlling extrinsic motivation, and this may be the reason why in our study there was no significant relationship between extrinsic motivation and creativity.

The Relationship Between Promotion Focus and Intrinsic Motivation

Our study also found that promotion focus was positively associated with intrinsic motivation, and this result is consistent with previous studies (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Smith et al., 2009; Vansteenkiste and Ryan, 2013; Li et al., 2016; Vaughn, 2016a,b). Previous research has suggested that regulatory focus affects intrinsic motivation both directly and indirectly. Promotion-focused individuals not only experience higher interest in a boring task but also try to make the task more interesting (Smith et al., 2009). Vaughn’s (2016a,b, 2019) recent work revealed that people who pursue promotion-focused goals experience more intrinsic motivation, while people who pursue prevention-focused goals experience more extrinsic motivation, which might be because a promotion focus leads to higher satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs than prevention focus. Therefore, promotion focus might improve intrinsic motivation through the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs.

The Mediating Effect of Intrinsic Motivation Between Regulatory Focus and Creativity

Moreover, consistent with our hypotheses, our study supported the mediating effect of intrinsic motivation between regulatory focus and creativity. This finding might be explained by the beneficial effect of intrinsic motivation on creativity (Amabile, 1983) and Vaughn’s need-support model (Vaughn, 2016a); the latter combines regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997, 1998) and self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000) to reveal the relation between regulatory focus and intrinsic/extrinsic motivation. Vaughn’s need-support model (Vaughn, 2016a) suggests that promotion focus might result in intrinsic motivation; furthermore, numerous studies have supported that intrinsic motivation is conducive to creativity (Amabile, 1983; Dong, 1993; Yang and Zhang, 2004; Cooper and Jayatilaka, 2006; Prabhu et al., 2008). Thus, promotion focus might benefit creativity by improving intrinsic motivation.

Contributions

Regarding the relationship between regulatory focus and creativity, there have been some studies on the underlying moderating mechanism (for example, Baas et al., 2008, 2011); however, previous literature has not probed the mediating effect underlying the regulatory focus–creativity link. Thus, since our study revealed the mediating role of intrinsic motivation, it contributed to the existing literature by enlightening the understanding of the path through which regulatory focus exhibits its impact on creativity, and providing and initiating a new research perspective on the regulatory focus–creativity link. Second, Vaughn’s (2016a,b, 2019) need-support model emphasized the close relationship between regulatory focus and intrinsic/extrinsic motivation; thus, our finding about the mediating role of intrinsic motivation in the regulatory focus–creativity link provided empirical support for the need-support model. Third, previous studies on the relationship between regulatory focus and creativity focused mainly on undergraduate students [with the exception of the research of Jin et al. (2016)]; thus, our study focusing on adolescent participants greatly enriched the previous literature by improving the understanding of adolescents’ creativity development and its determinants.

The results of our study also have practical implications for the cultivation of creativity in the settings of school and family. Although creative thinking training is important and effective for creativity cultivation (Shen et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2016; Kashani-Vahid et al., 2017), it is not the only approach, since creativity involves both an ability/thinking aspect and a motivation/attitude aspect (Wang et al., 1998; Sternberg, 1999; Li and Zhang, 2006). Thus, from this perspective, our study underlined the importance of the motivation approach of creativity cultivation.

Moreover, given that promotion focus is beneficial to creativity, fostering promotion focus may result in the improvement of creativity. Higgins (1997) asserted that regulatory focus is closely related to parenting behavior, especially how parents satisfy children’s needs; to be detailed, the satisfaction of children’s growth needs would strengthen promotion focus, while the satisfaction of children’s safety needs would induce prevention focus. Thus, to instill promotion focus, parents should pay more attention and provide enough satisfaction to children’s growth needs rather than safety needs, encourage their exploration to the world, and provide necessary assistance for them. This is especially of great importance for girls because they are more prevention focused than boys. Parents of girls should deliberately reduce the various restraints imposed on girls for the sake of safety and avoid delivering high-level worry about safety to them. Furthermore, regulatory focus is not only a chronic proposition resulting from long-term family environmental influences but also an inclination that is sensitive to temporary situational induction (Zaal et al., 2011). Thus, in the school setting, to induce promotion focus, teachers can guide students to pay more attention to their personal interests, aspirations, and ideals rather than duties and responsibilities.

In addition, since intrinsic motivation is conducive to creativity, the enhancement of intrinsic motivation is also an important path of creativity cultivation. According to the self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000), autonomy support from teachers or parents can provide satisfaction to students’ psychological needs, which would further induce intrinsic motivation; in contrast, environment control can result in the frustration of psychological needs, which would further induce extrinsic motivation (Costa et al., 2016; Collie et al., 2019). Thus, teachers and parents should create a more autonomy-supportive atmosphere instead of an atmosphere full of stress, threat, and strict constraints. In the classroom, teachers can guide students to set appropriate goals based on their personal interests and innovate teaching methods that incentivize students’ curiosity, which are also helpful to instill students’ intrinsic motivation.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of this study must be addressed. First, since the data used in this study are cross-sectional, the conclusions on the relationships between variables must be treated with caution. Future research can further examine this relationship with an experimental or longitudinal research design. Second, in our study, the hypothesized mediating effect of extrinsic motivation was not supported, and extrinsic motivation showed no significant relationship with regulatory focus and creativity. Although there is a possibility that this result is valid, there might be other possibilities. For example, this result might imply the existence of a floor effect, i.e., the extrinsic motivation scores were too low, and therefore, the relation between extrinsic motivation and other variables was concealed. In addition, this result might be associated with the measure of extrinsic motivation. In our study, extrinsic motivation was measured by the extrinsic motivation subscale of the Working Preference Inventory (Amabile et al., 1994), in which the items involve synergistic extrinsic motivation, informational extrinsic motivation, and controlling extrinsic motivation; thus, this compound extrinsic motivation would show no effect on creativity, since different types of extrinsic motivation exhibit different effects on creativity (Amabile and Pratt, 2016). Future research can further explore the extrinsic motivation–creativity link by adopting instruments that can assess different types of extrinsic motivation. Last, our study found no significant relationship between prevention focus and creativity. Future research using alternative measures of both regulatory focus and creativity (such as creative tasks or behavior indexes) may reveal a clearer relationship between prevention focus and creativity, as well as the underlying mediation mechanism and moderation mechanism between them.

Conclusion

In this study, SEM showed that promotion focus positively predicted intrinsic motivation, which, in turn, positively predicted creativity, and the bootstrapping method showed that the mediating effect was significant. In general, our study suggested that intrinsic motivation played a mediating role between promotion focus and creativity in adolescents.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Psychology College of Capital Normal University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

LW contributed to the conception and design of the study. JW contributed to the participants recruit and organized the survey. XW and KD organized the database. YC, XW, and ZL performed the statistical analysis. XW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LW, XW, and YC wrote the sections of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Beijing Social Science Fund Project (18JYB013).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: a componential conceptualization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 45, 357–376. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357

Amabile, T. M., Hill, K. G., Hennessey, B. A., and Tighe, E. M. (1994). The work preference inventory: assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 66, 950–967. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.950

Amabile, T. M., and Pratt, M. G. (2016). The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 36, 157–183. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2016.10.001

Baas, M., De Dreu, C. K. W., and Nijstad, B. A. (2008). A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: Hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus? Psychol. Bull. 134, 779–806. doi: 10.1037/a0012815

Baas, M., De Dreu, C. K. W., and Nijstad, B. A. (2011). When prevention promotes creativity: the role of mood, regulatory focus, and regulatory closure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 100, 794–809. doi: 10.1037/a0022981

Baer, M., Leenders, R. A. G., Oldham, G. R., and Vadera, A. K. (2010). Win or lose the battle for creativity: the power and perils of intergroup competition. Acad. Manag. J. 53, 827–845. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2010.52814611

Bittner, J. V., and Heidemeier, H. (2013). Competitive mindsets, creativity, and the role of regulatory focus. Think. Skills Creativ. 9, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2013.03.003

Collie, R. J., Granziera, H., and Martin, A. J. (2019). Teachers’ motivational approach: links with students’ basic psychological need frustration, maladaptive engagement, and academic outcomes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 86:102872. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.07.002

Collins, M. N., and Amabile, T. M. (1999). “Motivation and creativity,” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. R. J. Stemberg (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 297–312. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511807916.017

Conti, R., Collins, M. A., and Picariello, M. L. (2001). The impact of competition on intrinsic motivation and creativity: considering gender, gender segregation and gender role orientation. Pers. Individ. Diff. 31, 1273–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00217-8

Cooper, R. B., and Jayatilaka, B. (2006). Group creativity: the effects of extrinsic, intrinsic, and obligation motivations. Creativ. Res. J. 18, 153–172. doi: 10.1207/s15326934crj1802_3

Costa, S., Cuzzocrea, F., Gugliandolo, M. C., and Larcan, R. (2016). Associations between parental psychological control and autonomy support, and psychological outcomes in adolescents: the mediating role of need satisfaction and need frustration. Child Indic. Res. 9, 1059–1076. doi: 10.1007/s12187-015-9353-z

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Derryberry, D., and Tucker, D. M. (1994). “Motivating the focus of attention,” in The Heart’s Eye: Emotional Influences in Perception and Attention, eds P. M. Niedenthal and S. Kitayama (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 167–196. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-410560-7.50014-4

Dong, Q. (1993). The Characteristics of Children’s Psychological Development in Creative Ability. Zhejiang: Zhejiang Education Publishing House.

Eisenberger, R., and Rhoades, L. (2001). Incremental effects of reward on creativity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 728–741. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.4.728

Fischer, C., Malycha, C. P., and Schafmann, E. (2019). The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Front. Psychol. 10:137. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00137

Förster, J., Friedman, R., Özelsel, A., and Denzler, M. (2006). Enactment of approach and avoidance behavior influences the scope of perceptual and conceptual attention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 42, 133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.02.004

Friedman, R. S., and Förster, J. (2001). The effects of promotion and prevention cues on creativity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 1001–1013. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1001

Grant, A. M., and Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 54, 73–96. doi: 10.1017/S0031819100026383

Guo, D., Huang, M., and Ma, Q. (2000). Creativity and creative motivation of scientific researchers. Chin. J. Appl. Psychol. 6, 8–13.

Hamstra, M. W., Bolderdijk, J. W., and Veldstra, J. L. (2011). Everyday risk taking as a function of regulatory focus. J. Res. Pers. 45, 134–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.017

Herman, A., and Reiter-Palmon, R. (2011). The effect of regulatory focus on idea generation and idea evaluation. Psychol. Aesthet. Creativ. Arts 5, 13–20. doi: 10.1037/a0018587

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 52, 1280–1300. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.12.1280

Higgins, E. T. (1998). “Promotion and prevention: regulatory focus as a motivational principle,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 30, ed. M. P. Zanna (New York, NY: Academic Press), 1–46. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60381-0

Higgins, E. T., Friedman, R. S., Harlow, R. E., Idson, L. C., Ayduk, O. N., and Taylor, A. (2001). Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: promotion pride versus prevention pride. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 31, 3–23. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.27

Jin, X., Wang, L., and Dong, H. (2016). The relationship between self-construal and creativity—Regulatory focus as moderator. Pers. Individ. Diff. 97, 282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.044

Kashani-Vahid, L., Afrooz, G., Shokoohi-Yekta, M., Kharrazi, K., and Ghobari, G. (2017). Can a creative interpersonal problem solving program improve creative thinking in gifted elementary students? Think. Skills Creativ. 24, 175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2017.02.011

Kirton, M. J. (1976). Adaptors and innovators: a description and measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 61, 622–629. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.61.5.622

Lam, W. H., and Chiu, C. Y. (2002). The motivational function of regulatory focus on creativity. J. Creative Behav. 36, 138–150. doi: 10.1002/j.2162-6057.2002.tb01061.x

Lanaj, K., Chang, C. H., and Johnson, R. E. (2012). Regulatory focus and work-related outcomes: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 138, 998–1034. doi: 10.1037/a0027723

Li, A., and Zhang, Q. (2006). A study of graduate students’ creative motivation. Psychol. Sci. 29, 857–860. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2006.04.022

Li, M. (2015). The Relationship of Challenge Stressor, Regulation Focus and Creativity. M.A. thesis. Chongqing: Southwest University.

Li, M., Gao, J., Wang, Z., and You, X. (2016). Regulatory focus and teachers’ innovative work behavior: the mediating role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 14, 42–50.

Lin, C. (2017). A multi-level test for social regulatory focus and team member creativity: mediating role of self-leadership strategies. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 38, 1057–1077. doi: 10.1108/lodj-05-2016-0125

Lin, X., and Wang, M. (1997). Williams Creativity Assessment Packet (in Chinese). Taibei: Psychology Press.

Prabhu, V., Sutton, C., and Sauser, W. (2008). Creativity and certain personality traits: understanding the mediating effect of intrinsic motivation. Creativ. Res. J. 20, 53–66. doi: 10.1080/10400410701841955

Rogers, W. M., and Schmitt, N. (2004). Parameter recovery and model fit using multidimensional composites: a comparison of four empirical parceling algorithms. Multivariate Behav. Res. 39, 379–412. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3903_1

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., Mims, V., and Koestner, R. (1983). Relation of reward contingency and interpersonal context to intrinsic motivation: a review and test using cognitive evaluation theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 45, 736–750. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.736

Sacramento, C. A., Fay, D., and West, M. A. (2013). Workplace duties or opportunities? Challenge stressors, regulatory focus, and creativity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. Process. 121, 141–157. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2013.01.008

Semin, G. R., Higgins, T., de Montes, L. G., Estourget, Y., and Valencia, J. F. (2005). Linguistic signatures of regulatory focus: how abstraction fits promotion more than prevention. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 89, 36–45. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.36

Shalley, C. E., Zhou, J., and Oldham, G. R. (2004). The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: where should we go from here? J. Manag. 30, 933–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.007

Shen, D., Lv, Y., and Ma, L. (2000). Experimental study on divergent thinking training for high school students. Explor. Psychol. 20, 24–29. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-5184.2000.04.006

Smith, J. L., Wagaman, J., and Handley, I. M. (2009). Keeping it dull or making it fun: task variation as a function of promotion versus prevention focus. Motiv. Emot. 33, 150–160. doi: 10.1007/s11031-008-9118-9

Sternberg, R. J. (1999). Handbook of Creativity, Vol. 1999. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 251–272.

Sun, J., Chen, Q., Zhang, Q., Li, Y., Li, H., Wei, D., et al. (2016). Training your brain to be more creative: Brain functional and structural changes induced by divergent thinking training. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 3375–3387. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23246

Tang, C., Li, M., and Shao, Y. (2015). The relationships between material rewards and motivating employee’s creative ideas. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Sci. Ed.) 42, 644–651. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9497.2015.06.003

Vansteenkiste, M., and Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 23, 263–280. doi: 10.1037/a0032359

Vaughn, L. A. (2016a). Foundational tests of the need-support model: a framework for bridging regulatory focus theory and self-determination theory. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 43, 313–328. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/bfr5s

Vaughn, L. A. (2016b). Self-Determined Motivation is Higher to Strive for Promotion-Focused Goals than Prevention-Focused Goals. Unpublished manuscript. Ithaca, NY: Ithaca College.

Vaughn, L. A. (2019). Distinguishing between need support and regulatory focus with LIWC. Collab. Psychol. 5:32. doi: 10.1525/collabra.185

Vaughn, L. A., Baumann, J., and Klemann, C. (2008). Openness to experience and regulatory focus: evidence of motivation from fit. J. Res. Pers. 42, 886–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.008

Wang, H., Zhang, J., Lin, L., and Xu, B. (1998). Study on the creativity development of middle school students. Psychol. Sci. 30, 57–63.

Wang, J., Wang, L., Liu, R., and Dong, H. (2017). How expected evaluation influences creativity: regulatory focus as moderator. Motiv. Emot. 41, 147–157. doi: 10.1007/s11031-016-9598-y

Xu, X. (2008). Correlational study on parental style and coping style of adolescence. J. Xi Univ. Arts Sci. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 11, 117–120. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-777X.2008.01.029

Xue, G., Dong, Q., Zhou, L., Zhang, H., and Chen, C. (2001). The relationship of intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation to creativity. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 17, 6–11. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-4918.2001.01.002

Yang, L., and Zhang, Q. (2004). An experimental study on relationship between intrinsic-extrinsic motivation and creativity of 1-grade junior high school students. J. Southw. China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 29, 123–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02911031

Yen, C., Chao, S., and Lin, C. (2011). Field testing of regulatory focus theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 41, 1565–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00766.x

Zaal, M. P., Laar, C. V., Stahl, T., Ellemers, N., and Derks, B. (2011). By any means necessary: the effects of regulatory focus and moral conviction on hostile and benevolent forms of collective action. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 670–689. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02069.x

Zeng, X. (2010). Effect mechanism of parenting style on college students’ subjective well-being. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 26, 641–649. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2010.06.012

Keywords: regulatory focus, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, creativity, mediator, adolescents

Citation: Wang L, Cui Y, Wang X, Wang J, Du K and Luo Z (2021) Regulatory Focus, Motivation, and Their Relationship With Creativity Among Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 12:666071. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.666071

Received: 09 February 2021; Accepted: 01 April 2021;

Published: 20 May 2021.

Edited by:

Alessandro Antonietti, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Denise Fleith, University of Brasilia, BrazilEvangelia Karagiannopoulou, University of Ioannina, Greece

Copyright © 2021 Wang, Cui, Wang, Wang, Du and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ling Wang, d2FuZ2xpbmdfbHdAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Xinjing Wang, MzAzODcyMTIwQHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Ling Wang

Ling Wang Yue Cui

Yue Cui Xinjing Wang

Xinjing Wang Jin Wang

Jin Wang Kaiye Du

Kaiye Du Zheng Luo

Zheng Luo