- 1Peking University HuiLongGuan Clinical Medical School, Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, Beijing, China

- 2Zhumadian Psychiatric Hospital, Zhumadian, China

- 3Department of Neurosurgery, Sanbo Brain Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 4Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Biomedicine and Translational Medicine, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

Objective: Considerable evidence has shown that facial expression recognition ability and cognitive function are impaired in patients with depression. We aimed to investigate the relationship between facial expression recognition and cognitive function in patients with depression.

Methods: A total of 51 participants (i.e., 31 patients with depression and 20 healthy control subjects) underwent facial expression recognition tests, measuring anger, fear, disgust, sadness, happiness, and surprise. The Chinese version of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB), which assesses seven cognitive domains, was used.

Results: When compared with a control group, there were differences in the recognition of the expressions of sadness (p = 0.036), happiness (p = 0.041), and disgust (p = 0.030) in a depression group. In terms of cognitive function, the scores of patients with depression in the Trail Making Test (TMT; p < 0.001), symbol coding (p < 0.001), spatial span (p < 0.001), mazes (p = 0.007), the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test (BVMT; p = 0.001), category fluency (p = 0.029), and continuous performance test (p = 0.001) were lower than those of the control group, and the difference was statistically significant. The accuracy of sadness and disgust expression recognition in patients with depression was significantly positively correlated with cognitive function scores. The deficits in sadness expression recognition were significantly correlated with the TMT (p = 0.001, r = 0.561), symbol coding (p = 0.001, r = 0.596), maze (p = 0.015, r = 0.439), and the BVMT (p = 0.044, r = 0.370). The deficits in disgust expression recognition were significantly correlated with impairments in the TMT (p = 0.005, r = 0.501) and symbol coding (p = 0.001, r = 0.560).

Conclusion: Since cognitive function is impaired in patients with depression, the ability to recognize negative facial expressions declines, which is mainly reflected in processing speed, reasoning, problem-solving, and memory.

Introduction

Facial expression recognition isx considered an essential skill for successful social interactions, and it represents how others think of an individual and can potentially provide vague self-referential cues for making inferences and decisions. Accurate recognition of facial expressions is critical for the composition of interpersonal and cognitive functions (Wang et al., 2011; Hiser and Koenigs, 2018). In the 1970s, Ekman and Friesen proposed that human facial expressions contain six basic emotions, namely, happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise. These basic emotions are stable across cultures and races (Goghari and Sponheim, 2013). The facial emotion recognition deficit is a disorder, in which individuals experience difficulty in recognizing the emotional states of other people through facial expressions. Such a deficit may lead to a misunderstanding of the social behavior of others and interfere with the social function of an individual (Behere, 2015; Lee et al., 2020). The deficits in facial expression recognition have been found to be associated with depression and other mental illnesses (Cotter et al., 2018; Hayashi et al., 2021).

Cognitive theories suggest that people with depression interpret self-referential social information negatively, including facial expression recognition (Bone et al., 2019). Beck (1967) proposed that negative self-patterns may affect the interpretation of facial expressions, for example, by making ambiguous expressions more susceptible to negative interpretations. Since then, some studies have found that depressed people have a reduced ability to recognize facial expressions, in which neutral or ambiguous faces may be interpreted as sad (Gur et al., 1992; Gollan et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2016). In recent studies of depression, negative processing bias is considered to play a causal role in the development of depressive symptoms (Roiser et al., 2012). Studies have found that when compared with healthy controls, patients with depression are less accurate in recognizing happy expressions or are less likely to interpret neutral faces as happiness (Zwick and Wolkenstein, 2016; Vidal-Ribas et al., 2018). However, the results of the studies on facial expression recognition in patients with depression remain mixed.

Facial expression recognition is a special field of cognitive function. Impaired facial affect recognition and cognitive deficits are prevalent in people with depression (Vechetova et al., 2019). Being a core symptom of depression, cognitive dysfunction may be the underlying phenotype of affective disorders (Miskowiak et al., 2016). The degree of cognitive impairment and the severity of disease were found to be associated with deficits in facial expression recognition (Wiechetek Ostos et al., 2011; Sheardova et al., 2014). The deficits in facial expression recognition are related to cognitive functions such as working memory, attention, and even language ability (Barrett et al., 2011; Heck et al., 2017; Leib, 2019). Some studies have found that executive functions are related to deficits in facial expression recognition among adults with mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia (Yang et al., 2015). Similarly, Phillips et al. (2010) found that executive function could predict the performance of facial expression recognition in patients with depression. Research on cognitive bias suggests that depression is characterized by negative automatic thinking and biases in attention, interpretation, and memory (Mathews and MacLeod, 2005). The extant literature indicates that cognitive deficits in memory, processing speed, and executive functioning are particularly common in depression (Woo et al., 2016; Rao et al., 2019). However, the relationship between facial expression recognition and various aspects of cognitive impairment resulting from depression is yet to be fully determined. Accordingly, research on potential mechanisms, such as deficits in the recognition of emotions of other people, which might link the impaired cognitive function to interpersonal problems and behavioral disturbances, would increase our understanding of life with cognitive impairment in depression. The tests of emotion recognition may represent a potential tool for detecting early-stage cognitive impairment. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the relationship between facial expression recognition and cognitive function in patients with depression.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Huilongguan Hospital and the Ethics Committee of Zhumadian Psychiatric Hospital (ethics approval number: 2016-72). All subjects were informed of the content before the trial, freely volunteered to participate, and signed an informed consent form.

Participants

A total of 51 participants took part in this study, including 31 patients with depression and 20 healthy individuals, with similar age, gender, and education.

In the patient group, we recruited patients with depression who were outpatients or inpatients at Zhumadian Psychiatric Hospital from July 2018 to August 2019. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) met the United States Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for depression diagnosis, (2) the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17) score of ≥17 points, with more than two depressive episodes, (3) Han nationality, and (4) aged 18–50 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) presence of other mental disorder (comorbid anxiety disorders were not excluded), (2) history of cerebral organic diseases, cerebral injury, electrical shock treatment, or other serious physical diseases, (3) history of alcohol and substance abuse, (4) mental retardation, (5) pregnant and lactating women, and (6) claustrophobia.

In the control group, healthy subjects in the community surrounding the Zhumadian Second People’s Hospital during the same period were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) no past history of mental disorders, (2) matched the race, age, sex, and years of education of the patient groups, (3) HAMD-17 score of <7 points, and (4) no family history of mental disorders. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) first-degree relatives diagnosed with a mental illness, (2) history of cerebral organic diseases, cerebral injury, electrical shock treatment, or other serious physical illnesses, (3) history of alcohol and substance abuse, (4) mental retardation, and (5) pregnant and lactating women.

Facial Expression Recognition

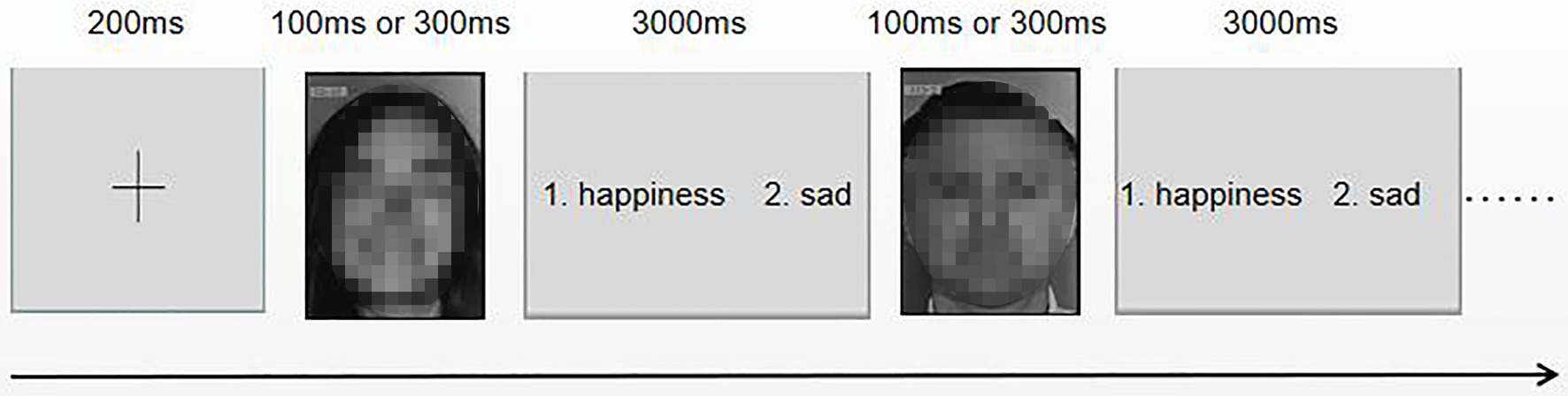

The participants performed the facial expression recognition tests. Ten models (i.e., six females and four males) were selected from the Ekman gallery. Each model had six unique facial expressions (i.e., happiness, sadness, fear, disgust, surprise, and anger), with a total of 60 pictures. The experimental program was compiled and run with E-prime 2.0 (experimental program software). Before the test, the participants were informed about the rules of the test and practiced. In each trial, the participants were asked to distinguish between the two facial expressions of 10 models (i.e., a total of 15 sets of faces, each set of 20 pictures). As shown in Figure 1, after the subjects pressed the “space” key, the participants were presented with a fixation point “+” for 200 ms in the center of the screen. Subsequently, the fixation point disappeared, and then a picture of the emotional expression of the model was randomly presented. The presentation time was randomly set for the picture to appear for either 100 or 300 ms. The task was to choose one or two of the two expression options to judge the expression presented. To prevent the subjects from stopping the task or being distracted during the task, they were asked to make a judgment within 3,000 ms; otherwise, the task automatically jumped to the next picture. An expression without a judgment was marked as incorrect. The advantage of this paradigm is that it is a comprehensive test of basic facial recognition.

Cognitive Function Test

All participants were instructed to complete the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) using a computer under the guidance of an experienced physician. The 10 subtests of the MCCB were organized into the following seven domains:

1. Speed of processing (SOP): Trail Making Test (TMT), Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) symbol coding (SC), and category fluency (CF)

2. Attention/vigilance (AV): continuous performance test-identical pairs (CPT-IP)

3. Working memory (WM): spatial span (SS) and digital sequence (DS)

4. Verbal learning (VBL): Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R)

5. Visual learning (VSL): Brief Visuospatial Memory Rest-Revised (BVMT-R)

6. Reasoning and problem-solving (RPS): Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB) mazes

7. Social cognition (SC): Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) managing emotions (ME).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA, Version 23.0). The experimental data of each group were expressed as x ± s. The chi-square test was used for sex between groups, and an independent sample t-test was used to compare age and education level. For the bilateral test, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We used to represent the accuracy of facial expression recognition – the measurement value of discriminate ability – which follows the signal detection theory and uses the hit rate and false positive rate to estimate recognition ability (Macmillan and Creelman, 2005). Raw scores for each of the 10 MCCB tests were transformed into T-scores. First, we calculated a series of t-tests to assess differences between patient groups and controls regarding emotion recognition performance and cognitive function variables. Second, we assessed the bivariate two-tailed Pearson’s correlations between facial expression recognition and cognitive scores in patients with depression. Finally, we used Pearson’s correlation to analyze the relationship between facial expressions that were significantly associated with cognitive function scores and various cognitive domains.

Results

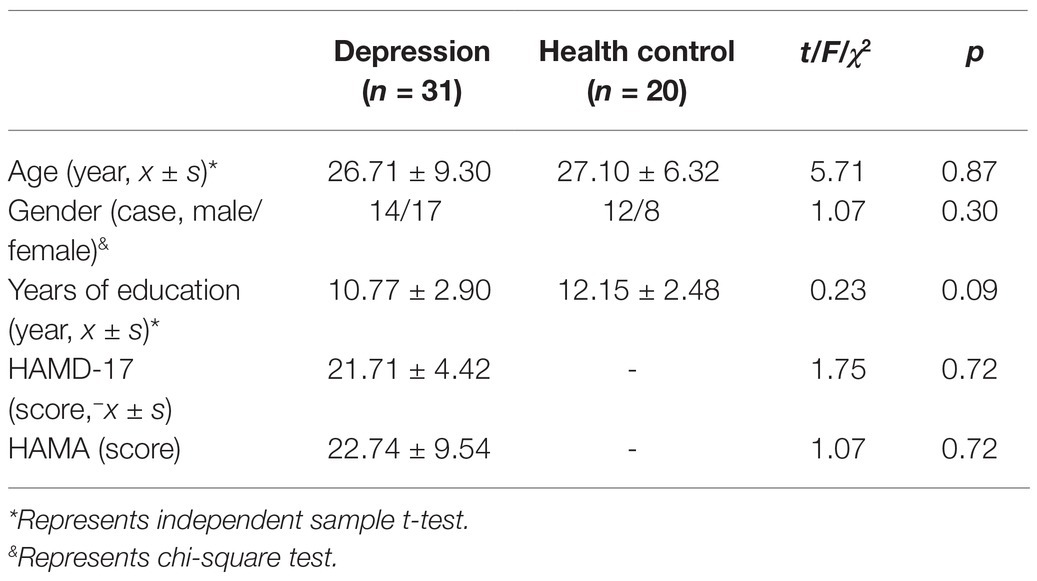

Descriptive information is presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age (F = 5.71, p = 0.87), gender (F = 1.07, p = 0.30), or years of education (F = 0.23, p = 0.09).

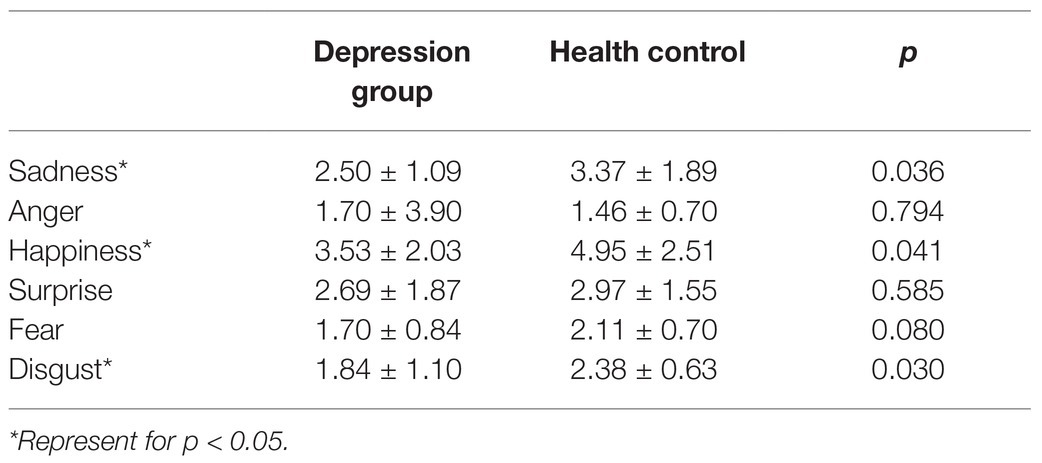

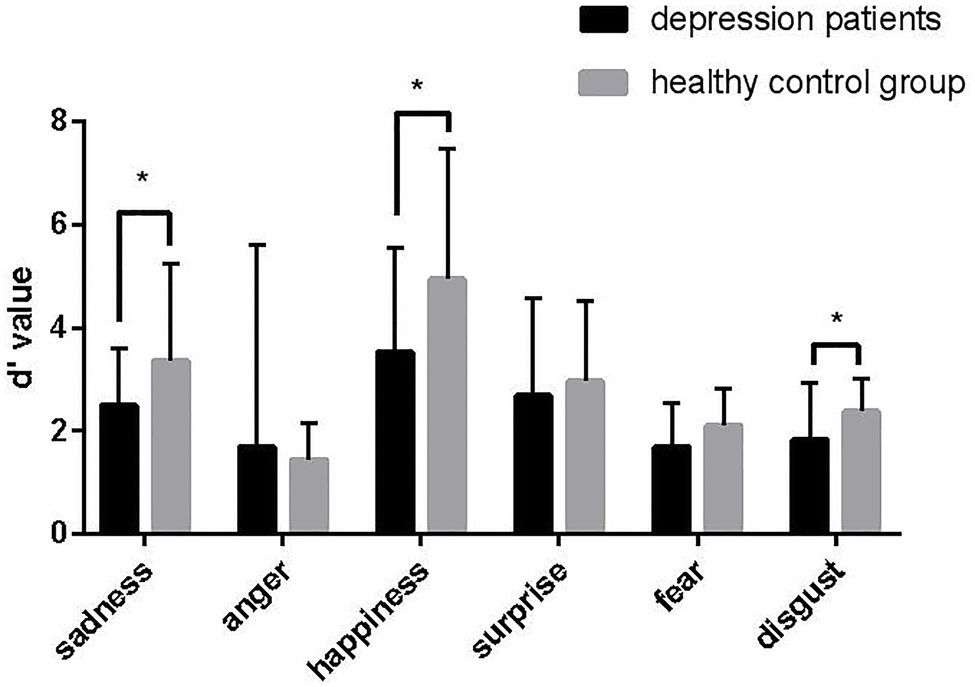

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, compared with the healthy control group, there were differences in the recognition of sadness (p = 0.036), happiness (p = 0.041), and disgust (p = 0.030) expressions in the depression group.

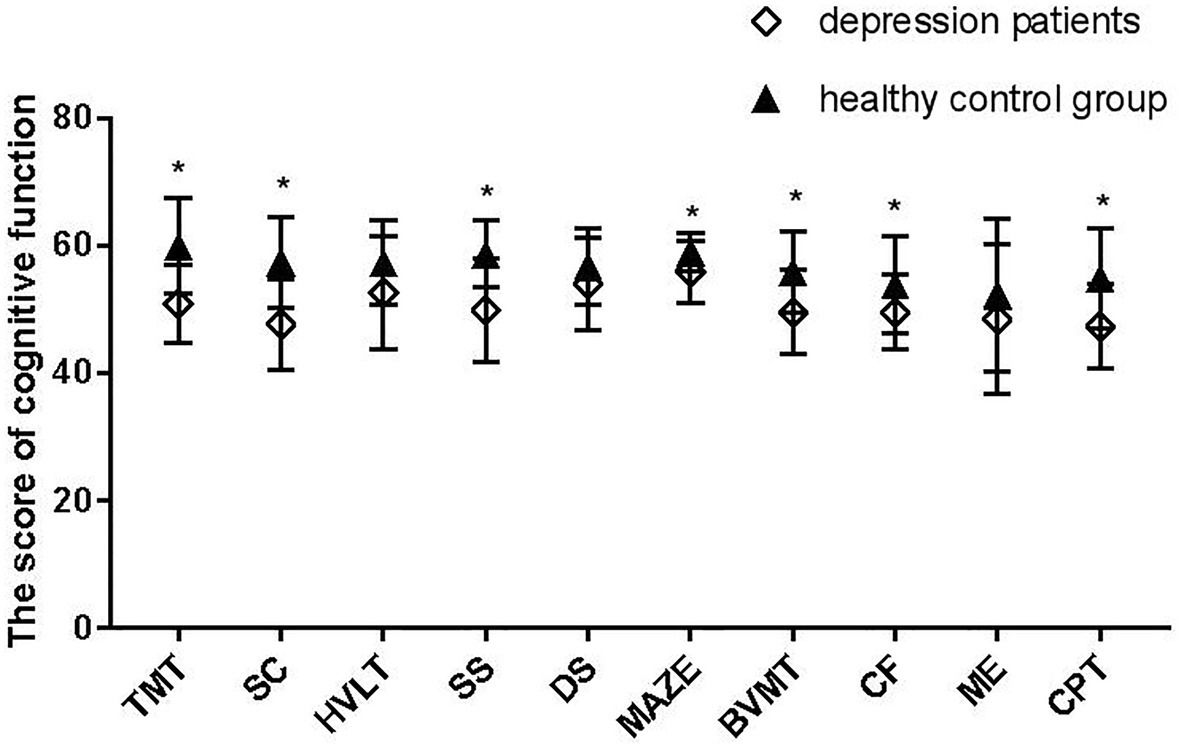

There are significant differences in TMT (p < 0.001), SC (p < 0.001), SS (p < 0.001), MAZE (p = 0.007), BVMT (p = 0.001), CF (p = 0.029), and CPT (p = 0.001) between the depression group and the control group (Figure 3).

Figure 3. MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) scores for the depression group and control group. *Represent for p < 0.05.

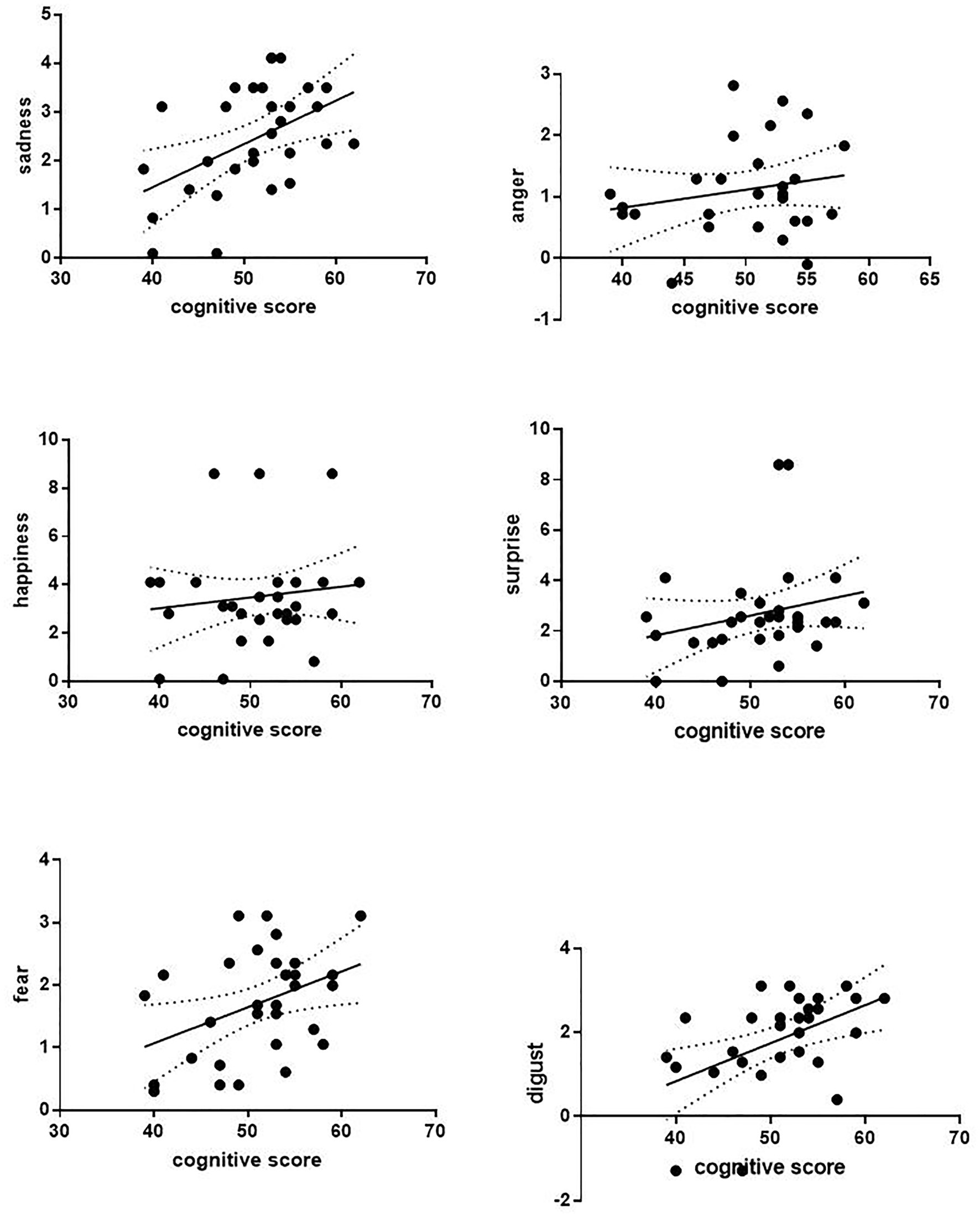

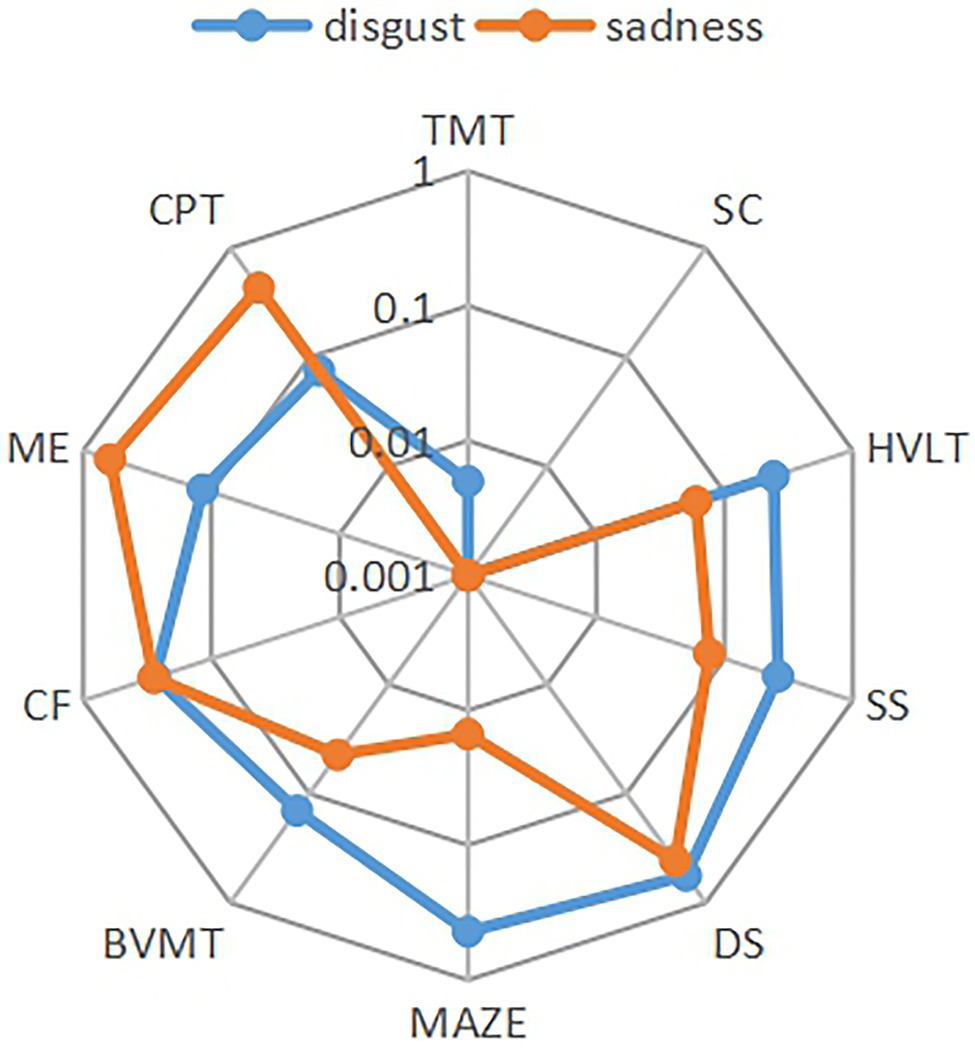

The correlation analysis of the relationship between six facial expressions and total cognitive scores was performed. Except for the weak correlation between disgust expression and cognitive score (p = 0.049, r = 0.445), other facial expressions were not correlated with cognitive scores in the control group. It also shows that the recognition of sadness (p = 0.005, r = 0.502) and disgust (p = 0.006, r = 0.486) facial expressions was positively correlated with cognitive function in patients with depression (Figure 4). The correlation analysis was performed between facial expression recognition and the cognitive domain in the depression group (Figure 5). Recognition of sadness facial expressions was related to TMT (p = 0.001, r = 0.561), SC (p = 0.001, r = 0.596), MAZE (p = 0.015, r = 0.439), and BVMT (p = 0.044, r = 0.370). Recognition of disgust facial expressions was related to TMT (p = 0.005, r = 0.501) and SC (p = 0.001, r = 0.560).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the association between cognitive function and recognition of emotions in facial expressions for patients with depression. The main finding was that people with depression were less able to recognize facial expressions, especially in differentiating negative expressions. Earlier studies found a negative bias in facial expression recognition for depression, which leads to a tendency to identify neutral faces as sad ones (Gur et al., 1992; Leppänen et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2016). Our study further found that people with depression have trouble distinguishing between negative and neutral expressions. This difference may be due to differences in the paradigm experiment. Our experiment was less accurate at identifying pairs of negative and neutral expressions, such as fear and surprise, in a limited set of two expressions. Facial expression recognition is mediated by a distributed neural system in humans that involves multiple bilateral regions (Haxby et al., 2000). The discrimination of facial expressions may be reflected in brain activity patterns. For example, Vrticka et al. (2014) considered fear as a negatively valenced surprise. We hypothesized that the brain regions that govern the expression of these two facial expressions may come from the same region, which also increases the difficulty of expression recognition and leads to a decrease in accuracy. In addition, many earlier studies have used small samples (Chiu et al., 2018; Yılmaz et al., 2019), or selected several facial expressions for research (Milders et al., 2010; Lawlor-Savage et al., 2014), as well as experiments to study the perception of different expression tensions (Branco et al., 2017). Conversely, although our sample size was small, each subject was selected from two limited facial expressions and a total of 300 times were recognized for six facial expressions of 10 models, which significantly increased the stability and accuracy of the experiment. Moreover, as in several earlier studies, we did not consider the length of stimulus presentation as a variable in itself and only varied the duration to avoid habituation (Jerram et al., 2013; Gohier et al., 2014).

The second finding is that the decline in the facial expression recognition ability of patients with depression is related to the decline of cognitive function, especially for negative facial expressions. The recognition of negative facial expressions is mainly related to processing speed, reasoning, and problem-solving ability, which is consistent with earlier studies. Major depressive disorder is frequently associated with cognitive impairment. Earlier research has shown that depression is related to executive function, memory, and processing speed (Nebes et al., 2000; Butters et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2015). The results of a meta-analysis showed that patients with depression have various forms of cognitive decline, including attention, processing speed, executive function, and memory (Lim et al., 2013). In clinical practice, further research is needed to improve the cognitive function of patients by improving their processing speed, reasoning ability, and problem-solving ability. In addition, distinguishing depressed patients from the normal control group by recognizing facial expressions is the next step in our research.

Emotional dysregulation is a key clinical feature of depression. An increasing number of studies have shown that emotional processing and emotional regulation in patients with affective disorders are impaired, and some of them have potential neurocognitive dysfunction (Assion et al., 2010). Frank et al. (2014) believed that successful emotion regulation often implies prefrontal control over emotional reactivity associated with amygdala responses. The present functional magnetic resonance imaging shows that, when compared with healthy people, those suffering from depression have greater subcortical limbic activity when recognizing positive and negative facial expressions (Almeida et al., 2009). Studies have also found that the amygdala is involved in the recognition of not only fear but also other expressions such as happiness and sadness (Juruena et al., 2010). The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is related to various social, cognitive, and affective functions that are commonly disrupted in mental illness (Hiser and Koenigs, 2018). The current research suggests that the vmPFC regulates the fear response by inhibiting the amygdala (Quirk et al., 2003; Rosenkranz et al., 2003). Therefore, we speculated that patients with depression may differ from healthy people in brain areas such as the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the vmPFC.

The study on the structure and function of the brain in patients with depression has suggested some possible explanations for the link between cognitive decline and depression. The frontoparietal network is involved in the top–down regulation of attention and emotion, while the default network and the dorsal attention network are involved in internal and external attention, respectively (Nani et al., 2019). The dysregulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is associated with executive function, has been reported in the functional neuroimaging studies of depression during executive function. By using the meta-analysis, Kaiser et al. (2015) found that in the frontal network of depressed patients, there was low connectivity between the brain regions related to the cognitive control of attention and emotion regulation and between the frontoparietal and the parietal regions. Earlier research has suggested that WM, processing speed, and nonverbal memory capabilities are the indispensable components of emotional perception (Phillips et al., 2008; Mathersul et al., 2009). When attention, problem-solving ability, and speed of patients with depression decrease, the error rate of facial expression recognition increases. This implies that the decline in cognition in patients with depression may be caused by an imbalance between the brain networks. Thus, it is significant for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of depression to explore the abnormal brain structure and the mechanism of depression through the recognition of facial expressions in patients with depression.

This study has several limitations. First, whether the decline in facial expression recognition is caused by depression or cognitive decline remains an open question. Second, although the credibility of the experiment was high, the sample size was small. The neural mechanisms of facial expression recognition in patients with depression will be the next step in our study.

Conclusion

Since the cognitive function is impaired in patients with depression, the ability to recognize negative facial expressions declines, which is mainly reflected in processing speed, reasoning, problem-solving, and memory and is caused by the imbalance between the brain networks.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Beijing Huilongguan Hospital and the Ethics Committee of Zhumadian Mental Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

WZ and YF developed the concept and design of this study. MR and GH performed the experiments and analyzed the data. CN, LP, LS, TS, TY, SJ, and TL restructured, polished, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study received financial support from the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Project (grant nos. Z181100001518005, Z171100001017021, and Z17110000107022) and the Estonian Research Council-European Union Regional Developmental Fund Mobilitas Pluss Program number MOBTT77.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the doctors and nurses of Zhumadian Psychiatric Hospital for their support of the trial.

References

Almeida, J. R. C. D., Versace, A., Mechelli, A., Hassel, S., Quevedo, K., Kupfer, D. J., et al. (2009). Abnormal amygdala-prefrontal effective connectivity to happy faces differentiates bipolar from major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 6, 451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.024

Assion, H. J., Wolf, F., and Brüne, M. (2010). P01-190—Theory of mind and neurocognitive functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 26:191. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(11)71901-0

Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., and Gendron, M. (2011). Context in emotion perception. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20, 286–290. doi: 10.1177/0963721411422522

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. JAMA 203, 1144–1145. doi: 10.1001/jama.1968.03140130056023

Behere, R. V. (2015). Facial emotion recognition deficits: the new face of schizophrenia. Indian J. Psychiatry 57, 229–235. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.166641

Bone, J. K., Lewis, G., Button, K. S., Duffy, L., and Lewis, G. (2019). Variation in recognition of happy and sad facial expressions and self-reported depressive symptom severity: a prospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 257, 461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.025

Branco, L. D., Cotrena, C., Ponsoni, A., Salvador-Silva, R., Sjl, V., and Fonseca, R. P. (2017). Identification and perceived intensity of facial expressions of emotion in bipolar disorder and major depression. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 33, 1–11. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acx080

Butters, M. A., Whyte, E. M., Nebes, R. D., Begley, A. E., Dew, M. A., Mulsant, B. H., et al. (2004). The nature and determinants of neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61, 587–595. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587

Chen, J., Zhang, Y., Wei, D., Wu, X., Fu, Q., Xu, F., et al. (2015). Neurophysiological handover from MMN to P3a in first-episode and recurrent major depression. J. Affect. Disord. 174, 173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.049

Chiu, I., Piguet, O., Diehl-Schmid, J., Riedl, L., Beck, J., Leyhe, T., et al. (2018). Facial emotion recognition performance differentiates between behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 79:19. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11342

Cotter, J., Granger, K., Backx, R., Hobbs, M., Looi, C. Y., and Barnett, J. H. (2018). Social cognitive dysfunction as a clinical marker: a systematic review of meta-analyses across 30 clinical conditions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 84, 92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.014

Frank, D. W., Dewitt, M., Hudgens-Haney, M., Schaeffer, D. J., Ball, B. H., Schwarz, N. F., et al. (2014). Emotion regulation: quantitative meta-analysis of functional activation and deactivation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 45, 202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.06.010

Goghari, V. M., and Sponheim, S. R. (2013). More pronounced deficits in facial emotion recognition for schizophrenia than bipolar disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 54, 388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.10.012

Gohier, B., Senior, C., Radua, J., El-Hage, W., Reichenberg, A., Proitsi, P., et al. (2014). Genetic modulation of the response bias towards facial displays of anger and happiness. Eur. Psychiat. 29, 197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.03.003

Gollan, J. K., McCloskey, M., Hoxha, D., Coccaro, E. F., and Watson, D. (2010). How do depressed and healthy adults interpret nuanced facial expressions? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 119, 804–810. doi: 10.1037/a0020234

Gur, R. C., Erwin, R. J., Gur, R. E., Zwil, A. S., and Kraemer, H. C. (1992). Facial emotion discrimination: II. Behavioral findings in depression. Psychiatry Res. 42, 241–251. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90116-K

Haxby, J. V., Hoffman, E. A., and Gobbini, M. I. (2000). The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 223–233. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01482-0

Hayashi, S., Terada, S., Takenoshita, S., Kawano, Y., Yabe, M., Imai, N., et al. (2021). Facial expression recognition in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: is the preservation of happiness recognition hypothesis true? Psychogeriatrics 21, 54–61. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12622

Heck, A., Hock, A., White, H., Jubran, R., and Bhatt, R. S. (2017). Further evidence of early development of attention to dynamic facial emotions: reply to Grossmann and Jessen. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 153, 155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2016.08.006

Hiser, J., and Koenigs, M. (2018). The multifaceted role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in emotion, decision making, social cognition, and psychopathology. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.10.030

Jerram, M., Lee, A., Negreira, A., and Gansler, D. (2013). The neural correlates of the dominance dimension of emotion. Psychiatry Res. 221, 135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.11.007

Juruena, M. F., Glampietro, V. P., Smith, S. D., Surguladze, S. A., Dalton, J. A., Benson, P. J., et al. (2010). Amygdala activation to masked happy facial expressions. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 16, 383–387. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709991172

Kaiser, R. H., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Wager, T. D., and Pizzagalli, D. A. (2015). Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiat. 72, 603–611. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0071

Lawlor-Savage, L., Sponheim, S. R., and Goghari, V. M. (2014). Impaired recognition of happy facial expressions in bipolar disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 26, 253–259. doi: 10.1017/neu.2014.6

Lee, S., Liu, C., Kuo, C., Hsueh, I., and Hsieh, C. (2020). Sensitivity and specificity of a facial emotion recognition test in classifying patients with schizophrenia. J. Affect. Disord. 275, 224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.003

Lee, J., Mathews, A., Shergill, S., and Yiend, J. (2016). Magnitude of negative interpretation bias depends on severity of depression. Behav. Res. Ther. 83, 26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.05.007

Leib, S. (2019). Shedding light on the interconnected relationship between depressive symptoms, facial emotion recognition, and working memory. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Leppänen, J. M., Milders, M., Bell, J. S., Terriere, E., and Hietanen, J. K. (2004). Depression biases the recognition of emotionally neutral faces. Psychiatry Res. 128, 123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.05.020

Lim, J., Oh, I. K., Han, C., Huh, Y. J., Jung, I., Patkar, A. A., et al. (2013). Sensitivity of cognitive tests in four cognitive domains in discriminating MDD patients from healthy controls: a meta-analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 25, 1543–1557. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000689

Macmillan, N. A., and Creelman, C. D. (2005). Detection Theory: A User’s Guide. 2nd Edn. Vol. 8. New York: Psychology Press, 110–117.

Mathersul, D., Palmer, D. M., Gur, R. C., Gur, R. E., Cooper, N., Gordon, E., et al. (2009). Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: II. Core domains and relationships with general cognition. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsycol. 31, 278–291. doi: 10.1080/13803390802043619

Mathews, A., and MacLeod, C. (2005). Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1, 167–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143916

Milders, M., Bell, S., Platt, J., Serrano, R., and Runcie, O. (2010). Stable expression recognition abnormalities in unipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 179, 38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.015

Miskowiak, K. W., Kjærstad, H. L., Meluken, I., Petersen, J. Z., and Carvalho, A. F. (2016). The search for neuroimaging and cognitive endophenotypes: a critical systematic review of studies involving unaffected first-degree relatives of individuals with bipolar disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 73, 1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.011

Nani, A., Manuello, J., Mancuso, L., Liloia, D., Costa, T., and Cauda, F. (2019). The neural correlates of consciousness and attention: two sister processes of the brain. Front. Neurosci. 13:1169. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01169

Nebes, R. D., Butters, M. A., Mulsant, B. H., Pollock, B. G., Zmuda, M. D., Houck, P. R., et al. (2000). Decreased working memory and processing speed mediate cognitive impairment in geriatric depression. Psychol. Med. 30, 679–691. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799001968

Phillips, L. H., Channon, S., Tunstall, M., Hedenstrom, A., and Lyons, K. (2008). The role of working memory in decoding emotions. Emotion 8, 184–191. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.184

Phillips, L. H., Scott, C., Henry, J. D., Mowat, D., Bell, J. S., and Blanchard-Fields, F. (2010). Emotion perception in Alzheimer’s disease and mood disorder in old age. Psychol. Aging 25, 38–47. doi: 10.1037/a0017369

Quirk, G. J., Likhtik, E., Pelletier, J. G., and Paré, D. (2003). Stimulation of medial prefrontal cortex decreases the responsiveness of central amygdala output neurons. J. Neurosci. 23, 8800–8807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08800.2003

Rao, D., Xu, G., Lu, Z., Liang, H., Lin, K., and Tang, M. (2019). Comparative study of cognitive function between treatment-resistant depressive patients and first-episode depressive patients. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 15, 3411–3417. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s226405

Roiser, J. P., Elliott, R., and Sahakian, B. J. (2012). Cognitive mechanisms of treatment in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 117–136. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.183

Rosenkranz, J. A., Moore, H., and Grace, A. A. (2003). The prefrontal cortex regulates lateral amygdala neuronal plasticity and responses to previously conditioned stimuli. J. Neurosci. 23, 11054–11064. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.23-35-11054.2003

Sheardova, K., Laczó, J., Vyhnalek, M., Andel, R., Mokrisova, I., Vlcek, K., et al. (2014). Famous landmark identification in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 9:e105623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105623

Vechetova, G., Pastrnak, M., Sevcikova, M., Bartoskova, M., and Preiss, M. (2019). Cognitive functions in depression—current perspectives. Cesk. Psychol. 63, 562–575.

Vidal-Ribas, P., Brotman, M. A., Salum, G. A., Kaiser, A., Meffert, L., Pine, D. S., et al. (2018). Deficits in emotion recognition are associated with depressive symptoms in youth with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Depress. Anxiety 35, 1207–1217. doi: 10.1002/da.22810

Vrticka, P., Lordier, L., Bediou, B., Sander, D., and DeSteno, D. (2014). Human amygdala response to dynamic facial expressions of positive and negative surprise. Emotion 14, 161–169. doi: 10.1037/a0034619

Wang, Y., Su, Y., Fang, P., and Zhou, Q. (2011). Facial expression recognition: can preschoolers with cochlear implants and hearing aids catch it? Res. Dev. Disabil. 32, 2583–2588. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.06.019

Wiechetek Ostos, M., Schenk, F., Baenziger, T., and von Gunten, A. (2011). An exploratory study on facial emotion recognition capacity in beginning Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. Neurol. 65, 361–367. doi: 10.1159/000327979

Woo, Y. S., Rosenblat, J. D., Kakar, R., Bahk, W., and McIntyre, R. S. (2016). Cognitive deficits as a mediator of poor occupational function in remitted major depressive disorder patients. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 14, 1–16. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2016.14.1.1

Yang, C., Zhang, T., Li, Z., Heeramun-Aubeeluck, A., Liu, N., Huang, N., et al. (2015). The relationship between facial emotion recognition and executive functions in first-episode patients with schizophrenia and their siblings. BMC Psychiatry 15:241. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0618-3

Yılmaz, O., Mırçık, A. B., Kunduz, M., Çombaş, M., Öztürk, A., Deveci, E., et al. (2019). Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy, existential psychotherapy and supportive counselling on facial emotion recognition among patients with mild or moderate depression. Psychiatry Investig. 16, 491–503. doi: 10.30773/pi.2019.03.14

Keywords: depression, cognitive function, facial expression recognition, processing speed, problem-solving

Citation: Ruihua M, Hua G, Meng Z, Nan C, Panqi L, Sijia L, Jing S, Yunlong T, Shuping T, Fude Y, Li T and Zhiren W (2021) The Relationship Between Facial Expression and Cognitive Function in Patients With Depression. Front. Psychol. 12:648346. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648346

Edited by:

Tong Chen, Southwest University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Ruihua, Hua, Meng, Nan, Panqi, Sijia, Jing, Yunlong, Shuping, Fude, Li and Zhiren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yang Fude, eWFuZ2ZkMjAwQDEyNi5jb20=; Wang Zhiren, emhpcmVuNzVAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Ma Ruihua

Ma Ruihua Guo Hua2†

Guo Hua2† Zhao Meng

Zhao Meng Chen Nan

Chen Nan Tan Shuping

Tan Shuping Tian Li

Tian Li Wang Zhiren

Wang Zhiren