95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Psychol. , 21 May 2021

Sec. Emotion Science

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647473

This article is part of the Research Topic Social Convergence in Times of Spatial Distancing: The Role of Music During the COVID-19 Pandemic View all 45 articles

The COVID-19 outbreak required diverse strategies, such as social distancing and self-isolation, to avoid a healthcare system crisis. However, these measures have been associated with the onset or increase of anxiety and depression symptoms in the population. Music listening was previously shown to regulate emotion, consequently reducing depression symptoms. Since previous studies with Brazilian samples have already shown a high prevalence of depressive symptoms during the first confinement period, the aim of this study was threefold: (i) to compare groups with severe depression symptoms and no depression in what concerns to demographic and socio-economic factors as well as symptoms of anxiety and resilience levels, (ii) to explore changes in music listening daily routine during the confinement measures by both groups (no depression and severe depression), and (iii) to investigate which were the main factors influencing both two groups to music listening during the COVID-19 pandemic. This cross-sectional study included 494 Brazilian respondents aged 18 years and above. Our online survey comprised demographics, socio-economic, and COVID-19 related questionnaires, with questions regarding music listening used during social distancing measures on which the participants rated how much each of the 41 potential reasons for listening to music changed in importance compared to the situation before the pandemic and also the evaluation of anxiety, depression, and resilience levels. The respondents with severe depression were younger and showed higher levels of anxiety symptoms and lower resilience level. Furthermore, they were increasingly likely to listen to music to feel emotionally better with the situation, to feel comfort, to forget problems, to be energetic, to decrease sad feelings, to relax, to cheer up, to forget concerns, to express feelings, to reduce anxiety, to remember better times, to relieve boredom, to mentally stimulate themselves, and to ward off stressful thoughts compared to the participants with no depression. The exploratory factor analysis (FA) identified four types of music listening functions during social distancing measures: negative mood management, cognitive functioning, positive mood management, and physical involvement, in which the participants with severe depression revealed significant differences compared to non-depressed participants for the negative mood management factor, which shows the importance of music listening to regulate their negative emotions. As a conclusion, we can argue that most of our respondents used music listening to cope with and regulate their moods during confinement, especially those who presented with severe depression symptoms.

The COVID-19 disease was identified in December 2019 in China (Zhu et al., 2020). However, it rapidly spread to other countries, such as Brazil, in which the first case was confirmed on February 25 (Ribeiro and Leist, 2020). On March 11, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). Since then, strategies to prevent the spread of the virus and the burden on healthcare systems have been implemented globally, such as social distancing, confinement, school closure as well as recommendations to work from home. Nevertheless, several studies have shown a negative impact of the strategies mentioned above on psychological disorders’ burden (Brooks et al., 2020; Campos et al., 2020b). In the following paragraphs, we will introduce the impact of COVID-19 on mental health burden and music listening to regulate emotions.

Some of the psychological impacts of a pandemic might include the fear of getting sick or dying (Hall et al., 2008), the loss of a loved one (Hawryluck et al., 2005), the loss of income (Van Bortel et al., 2016) as well as decreasing satisfaction in life (Ammar et al., 2020) and well-being (Chtourou et al., 2020; Trabelsi et al., 2021) associated with the experience of social isolation. The lack of reliable and up-to-date information on the recovery cases and possible treatments can increase anxiety, stress (Wang et al., 2020), and depression symptoms (Hyland et al., 2020; Feter et al., 2021). Levels of uncertainty can be aggravated by inaccurate or misleading information about the outbreak in social media (Tang et al., 2018), a factor that has been recurrent in Brazil (Ribeiro and Leist, 2020).

It is necessary to point out that behavioral and mental disorders (BMD) are frequent among Brazilians of working productive age, hindering personal, social, and professional development (Santos and Siqueira, 2010). Thus, epidemiological studies indicate that among people aged 25–54, women are more affected by anxiety and mood disorders, being two to three times more susceptible to depression disorders (Santos and Siqueira, 2010; Carneiro and Baptista, 2012). Besides this, high-intensity stressors can potentially trigger suicidal ideas and suicide attempts, especially among young women with low socio-economic status (Rodrigues et al., 2012). A screening using a probabilistic sample of 5,037 Brazilian adults over 18 showed a prevalence (44.8%) of at least one BMD throughout their life—in which severe depression is one of the most frequent (16.9%) (Viana and Andrade, 2012) among all disorders that can be intensified due to confinement to avoid the spread of COVID-19 (Liu et al., 2020).

In a cross-sectional survey in China, during the COVID-19 outbreak, 53.8% of respondents rated the psychological impact of the epidemic as moderate or severe, and the effect was more significant on women. The results also showed a greater psychological impact of the outbreak and higher stress levels, anxiety, and depression in students (Wang et al., 2020) but lower when compared to developing countries such as Bangladesh (Islam et al., 2020) or even Brazil (Goularte et al., 2021; Ribeiro et al., 2021b).

Moreover, Ribeiro et al. (2021b) explored the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on mental health, especially depression and anxiety symptoms, in 936 Brazilian adults. They showed the prevalence of severe depression symptoms in 66.13% of the population, especially in women and young adults (18–39 years old). Congruently, Goularte et al. (2021), with a larger sample (N = 1996), identified that anxiety (81.9%) and depression (68%) were the most common psychological disorders found during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazilian adults. Furthermore, the pandemic can worsen the condition of patients with pre-existing mental health diseases (Ho et al., 2020; Feter et al., 2021). Given this scenario, studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Fullana et al. (2020) and recommended activities to prevent or mitigate the impacts of confinement on mental health, such as music listening (Kar et al., 2020).

Music is a crucial part of our daily life, and its influence on individuals’ mental health has been consistently shown by previous studies (DeNora, 1999; Sloboda and O’Neill, 2001; Silk et al., 2003; Pan et al., 2020). Saarikallio (2012) proposed that music listening’s effect on emotions has an essential impact on the listener’s mental health, in which music can evoke esthetic pleasure, emotional awareness, and autobiographical memories. Furthermore, she suggests three psychological aspects related to music listening which were organized by observing the results of previous studies. The first is the use of music to express, experience, and/or regulate emotions (Juslin and Västfjäll, 2008; Saarikallio et al., 2020); secondly, music is used as a means for reflection, personal development, relaxation, and mental work; and thirdly, music is used as an element to enhance social bonding, social cohesion, and/or identity.

Studies exploring why subjects listen to music revealed various reasons; for example, in the study of Lonsdale and North (2011), they noticed six motives for music listening, namely: negative mood management (music is utilized to relieve negative feelings and to improve mood), personal identity (music is used for the development of identity or to express a social image for others), surveillance (where music is used to keep up with current events or learn about things), positive mood management (music as a means to reach and enhance a positive mood), interpersonal relationships (music is used to encourage and sustain social contact), and diversion (music as a means to distraction, alleviate boredom, or pass the time). In a study carried out with adults with and without depression, Wilhelm et al. (2013) found 10 main reasons for listening to music as follows: energy and motivation, mood enhancement, relax or reduce stress, inspiration and stimulation, to express, experience, or understand emotion, focus and concentration, to match or reflect the mood, escape, distraction, or immersion, to reminisce, and solace, although all participants reported similar reasons for listening to music. The uses to express, experience, or understand emotion were more prevalent among participants with depression, while people without depression were more likely to endorse the themes of energy, motivation, inspiration, and stimulation.

Nevertheless, Schäfer et al. (2013) argue in their review that surveys diverge in the number of musical functions as well as its dimensions because they are quite analogous concerning social or emotional functions as well as cognitive or self-related purposes and arousal-associated or physiological functions. Notwithstanding, more recently, Sakka and Juslin (2018) evidenced that the most used strategy during music listening was discharging (the release of sad emotions).

Another point is that studies have shown that, in collectivist countries, i.e., Brazil, which prioritizes the group’s aims more than an individual’s needs, the population uses music to reach relaxation, motivation, and happy states, in contrast with individualist countries where people look for sadness–melancholy (Juslin et al., 2016; Saarikallio et al., 2020).

During the confinement and the measures imposed by the COVID-19 outbreak, a sharp increase in new users of musical streaming apps was observed (Hall, 2020); the time dedicated to music listening has also increased (Cabedo-Mas et al., 2020; Krause et al., 2020: Ribeiro et al., 2021a). One possibility is that music listening has been used more frequently to improve affective states. In fact, music listening has been established as one of the means to alleviate the impact of social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic since it reduces loneliness and is a means of distraction (Rodero, 2020), thus increasing mental wellness (Puyat et al., 2020).

Previous systematic reviews demonstrated that music listening can significantly decrease cortisol levels, consequently reducing physiological arousal and stress (Finn and Fancourt, 2018; de Witte et al., 2019). Other literature review showed, through 19 randomized controlled trials, that music listening could decrease subjective anxiety symptoms (Panteleeva et al., 2017). Besides these, music listening is often used by subjects presenting severe symptoms of depression, mainly for mood regulation, relaxation, and reflection (Maratos et al., 2008; Chan et al., 2011; Leubner and Hinterberger, 2017).

A recent study carried out by Pan et al. (2020) evidenced an enhancement in the symptoms of depression by those involved in a program that contrasted daily music listening to controls. The authors’ main rationale was that music is a vehicle of emotion, facilitating the non-verbal expression of emotion and affecting individuals’ innermost feelings without being threatening. For instance, music listening could regulate the mood of participants with depressive symptoms, serving as a tool for emotional catharsis (Pan et al., 2020).

Although we understand the essential role that music plays under the capacity of emotional regulation, music uses in the daily lives of people with depression in a pandemic context are underexplored.

For this reason, the main objective of this study was to explore changes in music listening during the period of social estrangement due to the COVID-19 pandemic and investigate the main factors for listening to music by participants with severe depression symptoms compared to subjects with no depression symptoms. The scenario of social isolation imposed by the pandemic of the new coronavirus asks questions about the potential effects of listening to daily music, which is relevant to be better understood in a population in which depressive symptoms seem to be highly prevalent (Campos et al., 2020b; Feter et al., 2021). Especially in developing countries like Brazil, the difficulties in offering mental health care to the population are known, so it is crucial to understand the effects of ecologically valid coping strategies, such as listening to music (de Souza and Machado-de-Sousa, 2017; Rzewuska et al., 2017; Fullana et al., 2020).

Our research questions were as follows: (i) are there socio-demographic, anxiety, and resilience level differences between groups (no depression and severe depression)? (ii) are there changes in music listening daily routine during the confinement measures by both groups?; and (iii) which are the main factors underlying music listening by the two groups?

The Ethics Committee of São Paulo State University “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” Bauru Campus approved this study (Process: 4.021.098). We obtained electronic informed consent from all participants before they began to fill the online survey.

This quantitative and cross-sectional study was performed to assess the music used by Brazilians during the COVID-19 outbreak. Data were collected using a snowball sampling approach through online-administered questionnaires disseminated in various personal social media platforms by the three authors (FR, FS, and GD). As our sample was composed of volunteers and the questionnaire was available online for a short period of time, it was not possible to establish the sample’s randomness. The inclusion criteria were subjects ≥18 years and in social distancing at the time of study data collection.

After excluding repetition (n = 23), those that did not accept to participate (n = 3), incomplete surveys (n = 25), and participants less than 18 years old (n = 3), a total of 494 participants who completed at least 90% of the survey were included in the analysis. From the total cohort of participants, 315 were female (63.77%) aged 18–72 years (M = 38.84, SD = 14.20) and 179 were male (36.23%) aged 18–76 years (M = 38.37, SD = 13.67). Four hundred seventy-seven participants were living in Brazil, while seven were living in North America, one in Asia, and 10 in Europe. We detected that 63.97% (64.76% of females) of our sample presented severe reported depression symptoms.

The data was collected between May 12 and June 12, 2020 through an anonymous online questionnaire available in free software (Google Forms®) that was circulated via social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other message apps). The study aims, confidentiality, and anonymity were clearly explained before the participants began the online survey. We obtained electronic informed consent from all participants before they began the online survey, and they participated voluntarily in the study. The participants could conclude the survey at any time, and no compensation was given for their participation.

The questionnaire was regarding a follow-up of the rules related to COVID-19, including data regarding schooling, age, marital status, gender, and socio-economic status.

These were questions about the use of music listening during social distancing measures, inclusive of 41 questions about their engagement with music (all items are displayed in Supplementary Material 4).

The Brief Resilience Scale [Smith et al. (2008), Portuguese version from Coelho et al. (2016)]: It assesses respondents’ capacity to deal with social relationships and health situations. It consists of five items, in which the participants respond on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

General Anxiety Disorder (Spitzer et al., 2006): It assesses generalized anxiety symptoms through seven items. The respondents should reply in a four-point Likert scale going from “not at all” to “several days,” “more than half of the days,” and “nearly every day.” The participants were classified with severe symptoms of anxiety when they presented ≥15 points on the sum of all the items.

Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977; Filho et al., 2011): This instrument comprises 20 items investigating depressive symptoms in various age groups in epidemiological studies. The participants were classified with severe symptoms of depression when they presented ≥15 points on the sum of all the items.

Data were analyzed descriptively. When appropriate, comparisons were made between groups with severe and no depression symptoms using t-tests for independent samples and chi-square tests (χ2). Moreover, to perform the previous quoted analyses, we excluded those respondents who answered: “I don’t know” or “I never had this habit” to be able to observe possible changes after the beginning of the social restriction measures. Descriptive statistics were generated for participants with severe depression and no depression; however, only statistically significant findings are discussed.

Subsequently, factor analysis (FA) was used to investigate the factors related to music listening during the COVID-19 pandemic for the whole sample. To check the best factor structure that would be suitable for the music questionnaire, two different techniques were applied: parallel analysis (PA) and very simple structure (VSS), both on R 3.4 (R Core Team, 2020). PA is a technique based on parameters given through the data used in order to randomly calculate eigenvalues from correlation matrices. On the other hand, VSS compares the fit of different factor solutions and shows these indices so the researcher can choose the best one based on the theoretical expectation. Altogether these two techniques can provide a robust factor solution to be extracted (Campos et al., 2020a; Revelle, 2020).

Then, a FA with the polychoric correlations and maximum likelihood extraction was used from the results of PA and VSS (see the Supplementary Material). After that, factor congruence was done to seek comparisons between the empirical factor loadings for each item and the factor structure’s theoretical factor loadings. In other words, factor congruence correlates the factor loadings found in the FA with each item’s expected factor loadings (i.e., “1” for the theoretical factor, and “0” for the other; Zanon et al., 2018; Revelle, 2020). When the best factor solution was found, Pearson correlation was used to check for external validity evidence, and violin plots were created from the score distribution according to the depression groups’ classification (no depression and severe depression symptoms) for each factor. Finally, the Yuen test for independent groups was used to explore whether differences could exist by comparing the severe depression and no-depression groups for each factor found. All analyses were performed on R 3.4 (R Development Team, 2020) through the packages dplyr (Wickham et al., 2018), ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016), and psych (Revelle, 2020).

Table 1 displays comparisons between respondents with severe depression and no depression symptoms during confinement measures. The Student’s t-test for independent measurements showed that the members of the severe depression group were younger than those of the no-depression group. Moreover, we detected that participants with severe depression presented lower levels of resilience but higher levels of anxiety symptoms than the group with no depression symptoms. Other significant differences detected by chi-square tests (χ2) were severe depression symptoms in groups with less formal education, less income, and whose members were likely to be single. Finally, the subjects with severe depression reported having a harder time staying at home during the social distancing measures than those without depression.

The second set of analysis using chi-square tests (χ2) showed that those participants with severe depression symptoms were more likely to report relying on music listening to change their mood (93.65%) compared to those with no depression (80%) during the confinement, χ2(2) = 20.61, p < 0.001. Moreover, participants with severe symptoms of depression reported that music was present in their daily life (83%); they were more likely to study or work listening to music (58%) as well compared to subjects without depression (74 and 49%, respectively, χ2 = 14.69, p < 0.001, χ2 = 11.27, p = 0.004).

Furthermore, the analysis carried out with the logistic regression detected that only listening to music to change the mood was associated with lower symptoms of depression (p = 0.004; OR = 0.36.1; 95% CI = 0.17–0.73).

The chi-square tests (χ2), including the responses for the use of music during social distancing measures comparing participants with severe symptoms of depression with those without depression, showed that the former was more likely to report listening to music as much more important to making them energetic, to decrease sad feelings, to take the tension off and relax, to cheer them up, to stop forgetting their concerns, to ward off stressful thoughts, to express feelings, to reduce anxiety, to entertain, to increase self-esteem, to help them think about their lives in a different perspective, to remind them of better times, to relieve boredom, to mentally stimulate, and to surf the Internet. It is a source of inspiration (p < 0.004; see Supplementary Table 3).

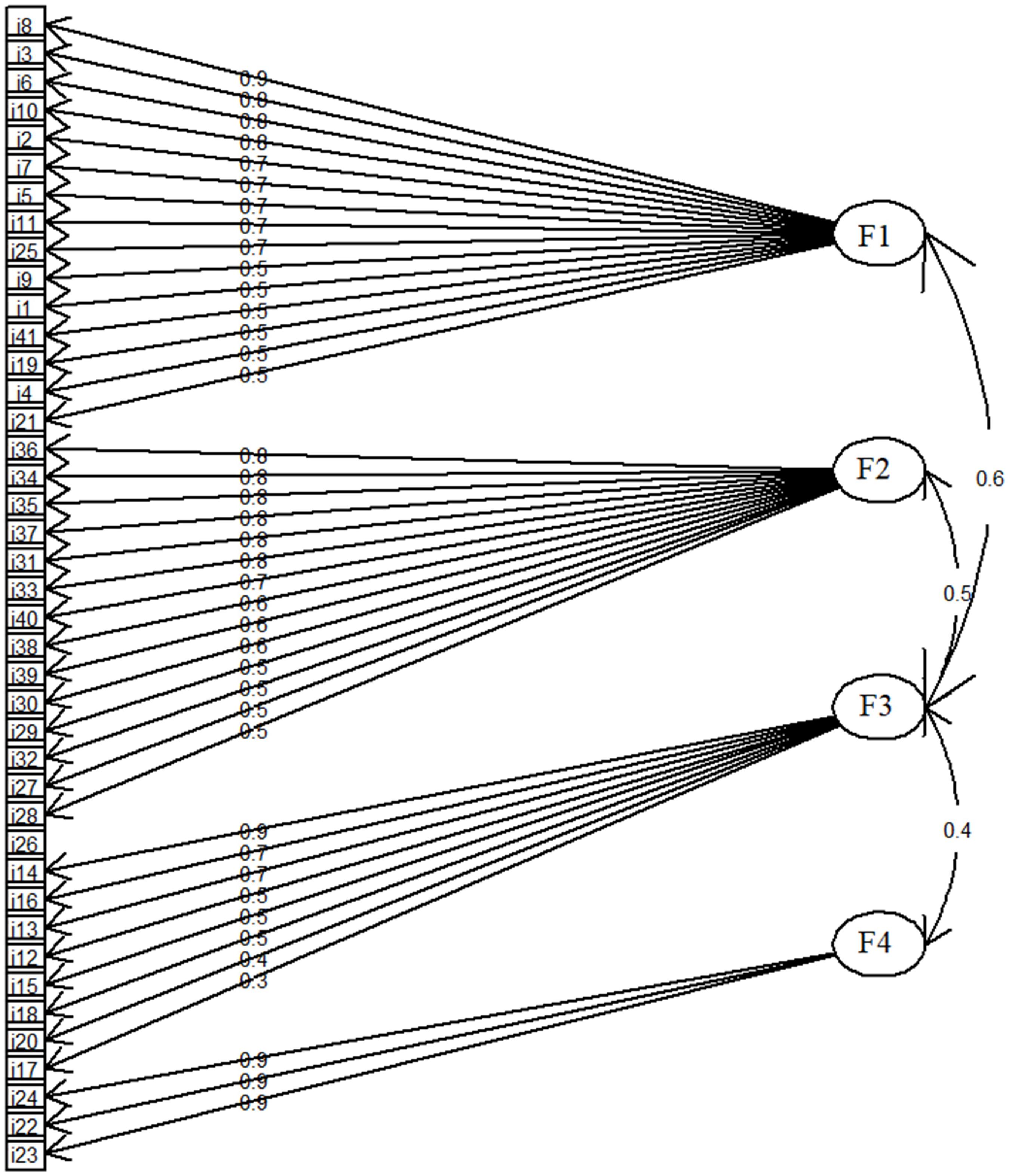

The FA conducted on the participants’ responses to the questionnaire items about the use of music during social distancing measures showed four different factors with higher eigenvalues. These together accounted for 46% of the variance present in the participants’ ratings. Factor loadings greater than 0.30 are shown in Figure 1 (for detailed results, see Supplementary Table 4). Specifically, factor 1 might be translated as “negative mood management” since it includes items regarding relieving negative feelings and mood improvement. Factor 2 might be interpreted as “cognitive function” where music is applied to perform cognitive skills, such as reading, arithmetic, memorizing, and learning new content. Factor 3 can be understood as “positive mood management” in which music is used to convey a positive mood, and, finally, factor 4 can be interpreted as “physical involvement.”

Figure 1. Factor loadings for music listening during pandemics. Fl, negative mood management; F2, cognitive function; F3, positive mood management; F4, physical involvement. All the questionnaire items are displayed in Supplementary Table 4.

As shown in Table 2, the Yuen test for independent groups was used to explore whether differences could exist by comparing the severe depression and no-depression groups for each factor found. We found that the groups differed only in the first factor (negative mood management).

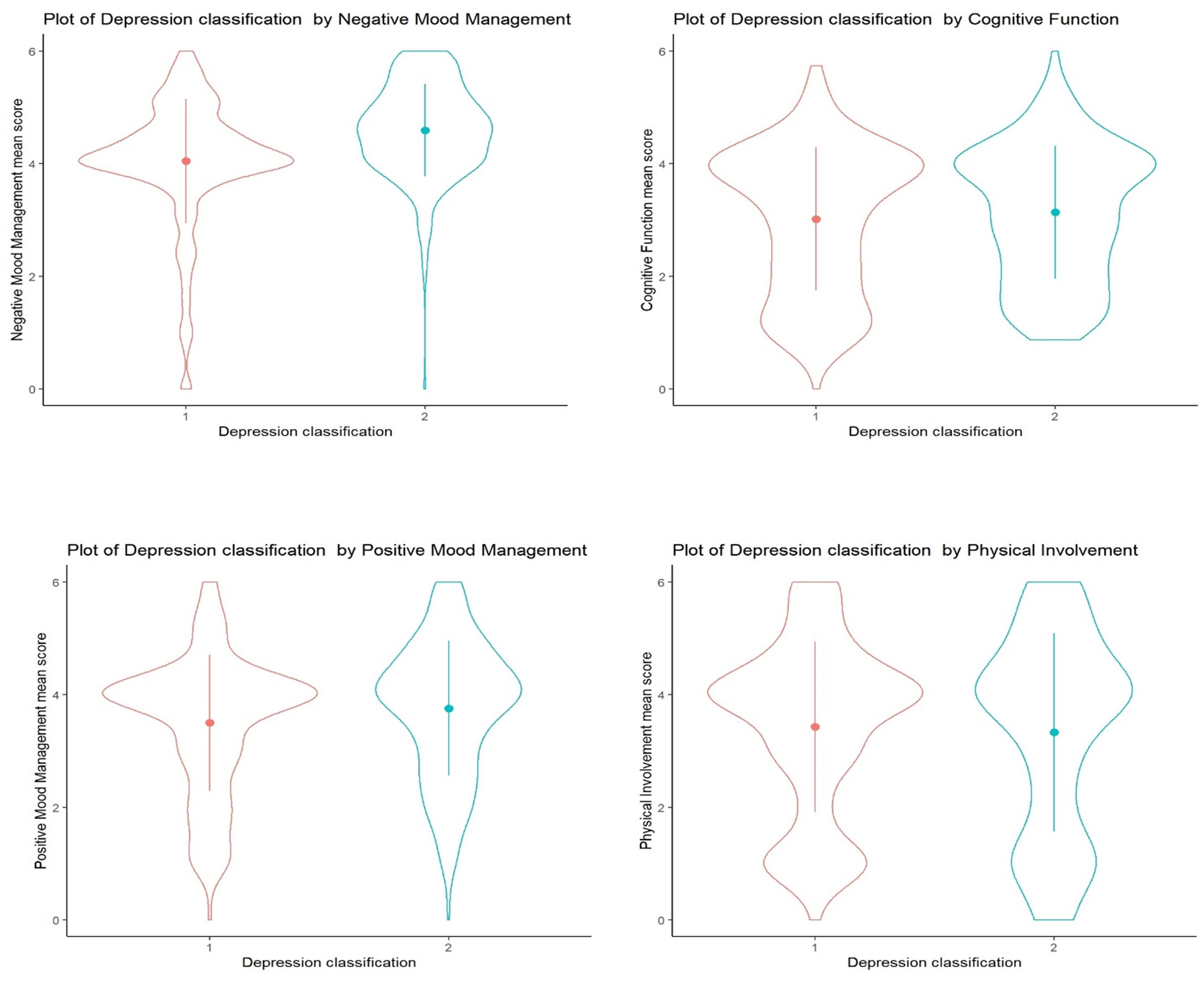

In the violin plot (see Figure 2), it is possible to find out the representation of distributions for the responses of each factor by groups and observe that the severe depression group had higher punctuation in what concerns negative mood management compared to the no-depression group, which means that, possibly, the first relies more on music to regulate the member’s negative mood.

Figure 2. Violin plots representing the distribution of the data for each factor by groups. 1, no depression; 2, severe depression.

Our aims with this study were to explore changes in music listening in individuals experiencing severe levels of depression and those with no depression symptoms and to investigate which were the factors underlying music listening during social distancing measures due to the COVID-19 outbreak by testing if music listening would be diverse from those without depression. In the following sections, we aimed to discuss the results for our three questions.

First of all, as we were expecting it, a prevalence of 63.96% for severe depression symptoms was detected, which is higher compared to that of other countries, such as the United States (Fitzpatrick et al., 2020), Ireland (Hyland et al., 2020), Germany (Bäuerle et al., 2020), Spain, and Greece (Papandreou et al., 2020), but in congruence with developing countries such as Bangladesh (Islam et al., 2020) as well as a study carried out in Brazil at the beginning of the pandemic (Campos et al., 2020b). These results might be related to the fear of losing their jobs and/or their beloved ones (Hawryluck et al., 2005), financial insecurity, and fewer resources from governmental measures (Van Bortel et al., 2016). In line with these arguments, we found that those respondents with severe symptoms of depression were more likely to have lower education, have a lower income, and be single. Some possible explanations are the difficulties that the population with lower socio-economic status have to deal with, such as difficulty in accessing the health system, inability to perform confinement for work reasons, and fear of losing their job, making them a more vulnerable group (Campos et al., 2020b).

Furthermore, in Brazil, it was possible to observe discrepant speeches from the power figures of the states and presidency and a lack of up-to-date information regarding the COVID-19 cases, which are features that might also hamper the sense of security and, consequently, the mental health of the respondents (Tang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020).

Moreover, we detected that those respondents presenting severe depression during the social distancing measures were younger, with lower resilience and with higher scores on the anxiety scores. These outcomes indicate a difficulty for younger people to cope with stressors and keep psychological distress at lower levels during this pandemic (Chen and Bonanno, 2020), possibly due to uncertainty about their future prospects (Ribeiro et al., 2021b).

In general, 87% of the participants revealed more engagement with music listening during social distancing measures, which agrees with studies showing increases in the use of music listening during the COVID-19 outbreak (Cabedo-Mas et al., 2020; Krause et al., 2020; Ribeiro et al., 2021a). However, we observed that those participants with severe depression symptoms differed significantly from those without depression regarding music uses during the distancing measures for coping with distressful emotions. For instance, it was possible to see more use in regards the relief of a negative mood (i.e., “to ward off stressful thoughts,” “take the tension off and relax,” “to cheer me up,” “to reduce my anxiety,” “decreases sad feelings,” “stop forgetting my concerns”), which was corroborated by the factor analyses. One possible explanation for differences just in these items might be, as previously shown, that individuals with depression use music to maintain their mood in order to feel validated and to feel acknowledged (Stewart et al., 2019).

Moreover, it is essential to mention that the subject’s music may include benefits in what consists of evoking positive moments, serving as a protective factor against symptoms of depression and improving well-being (Rutter, 2012). Besides these, even the choice of songs that have a negative-mood-matching component can promote a reduction in the intensity of the sad emotions, causing an improvement in depressive symptoms (Davis et al., 2008) due to its esthetically pleasant chords (Sachs et al., 2015). It can also provide moments of distraction beyond what is experienced at the moment by reducing the time spent on rumination (Polanco-Roman et al., 2015).

Through the FA, we observed four factors which correspond to “negative mood management,” cognitive enhancing, “positive mood management,” and “physical involvement,” which is in line with previous studies showing the importance of music listening to positive and negative mood management (Lonsdale and North, 2011; Schäfer et al., 2013). Besides this, this study found that the music listening main difference is in managing emotions, specifically for those positive and negative ones, which was also shown by Lonsdale and North (2011). This is important since we can detect those participants with depressive symptoms that could use diverse strategies in dealing with music compared to the non-depressive ones, more specifically to alleviate a negative mood (i.e., depressive symptoms, loneliness, and others) or/and produce or boost a positive mood (i.e., energize, relax, and others). In this context, we detected that individuals with severe depression symptoms respond differently to one of the factors, specifically the “negative mood management,” i.e., included questions related to decreasing of a sad feeling, boredom, stressful thoughts, and anxiety, in comparison to non-depressed participants. This might be explained by the importance of music listening in activating cerebral responses related to rewarding as well as neurophysiological responses such as relaxation (Osuch et al., 2009). Furthermore, people with depressive symptoms would use different strategies, as suggested by Sakka and Juslin (2018), in which the common regulatory strategy was the discharge—in other words, the release of negative emotions, although we could not confirm whether music listening in the participants with severe depression was characterized by adaptive behavior. It is crucial to claim robust findings pointing that personal music choice might improve depressive symptoms (Chan et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2020).

As far as we know, this is the first study to establish a model for using music in coping strategies. Therefore, the FA is a strength of this paper since it allowed us to identify the components implicit in the music experience coping strategies during the COVID-19 outbreak. This might guide clinicians and music therapists to use music in helping clients identify their emotions and take control over them (Maratos et al., 2008; Leubner and Hinterberger, 2017; Pan et al., 2020).

Although the number of participants is sufficient for statistical purposes, they provide enough power for the conclusions obtained. A key limitation of the study is the sample size in terms of national representativity. Firstly, it is due to a socio-economic bias, as individuals with lower income usually have less engagement with research—particularly with digital resources; second, despite our advert to participants which said, “the music in the pandemic,” we cannot rule out that the topic attracted more participants with depression than others. Finally, it is essential to highlight that the findings are based on the screening scale of depressive symptoms. It would be desirable to expand the work by testing this model in a clinically diagnosed sample. Moreover, we also need to point out that we did not assess the participants before the beginning of the pandemic. It is possible to suggest that the participants already had mild depressive symptoms, which worsened after the COVID-19 restrictions (Wang et al., 2020). A follow-up would still be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Based on our results, a high percentage of our sample adopted music listening during this context of uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 outbreak to improve their mood and deal with isolation, especially those with severe depressive symptoms.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Universidade Estadual Paulista/Campus Bauru. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

FR, FS, and GD designed the study. FS conceived the model for the theoretical framework. FR and JL analyzed the data. FR drafted the initial manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved its final version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank all the participants who collaborated in this study.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647473/full#supplementary-material

Ammar, A., Chtourou, H., Boukhris, O., Trabelsi, K., Masmoudi, L., Brach, M., et al. (2020). COVID-19 home confinement negatively impacts social participation and life satisfaction: a worldwide multicenter study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:6237. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176237

Bäuerle, A., Teufel, M., Musche, V., Weismüller, B., Kohler, H., Hetkamp, M., et al. (2020). Increased generalised anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Germany. J. Public Health (Bangkok) 42, 672–678. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa106

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395, 912–920. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30460-8

Cabedo-Mas, A., Arriaga-Sanz, C., and Moliner-Miravet, L. (2020). Uses and perceptions of music in times of COVID-19: a Spanish population survey. Front. Psychol. 11:606180. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606180

Campos, C. C., Oliveira, K. S., Lessa, J. P. A., and Primi, R. (2020a). Adaptation and validity study for the Brazilian population for the creativity domains scale. Psico 51:e34502. doi: 10.15448/1980-8623.2020.3.34502

Campos, J. A. D. B., Martins, B. G., Campos, L. A., Marôco, J., Saadiq, R. A., and Ruano, R. (2020b). Early psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: a national survey. J. Clin. Med. 9:2976. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092976

Carneiro, A. M., and Baptista, M. N. (2012). Saúde geral e sintomas depressivos em universitários. Salud Soc. 3, 166–178. doi: 10.22199/S07187475.2012.0002.00004

Chan, M. F., Wong, Z. Y., and Thayala, N. V. (2011). The effectiveness of music listening in reducing depressive symptoms in adults: a systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 19, 332–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.08.003

Chen, S., and Bonanno, G. A. (2020). Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: a resilience perspective. Psychol. Trauma 12, S51–S54. doi: 10.1037/tra0000685

Chtourou, H., Trabelsi, K., H’mida, C., Boukhris, O., Glenn, J. M., Brach, M., et al. (2020). Staying physically active during the quarantine and self-isolation period for controlling and mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic overview of the literature. Front. Psychol. 11:1708. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01708

Coelho, G. L., de, H., Hanel, P. H. P., Cavalcanti, T. M., Rezende, A. T., and Gouveia, V. V. (2016). Brief resilience scale: testing its factorial structure and invariance in Brazil. Univ. Psychol. 15, 397–408. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.upsy15-2.brst

Davis, W., Gfeller, K. E., and Thaut, M. H. (2008). An Introduction to Music Therapy: Theory and Practice, 3 Edn. Silver Spring, MD: American Music Therapy Association.

de Souza, I. M., and Machado-de-Sousa, J. P. (2017). Brazil: world leader in anxiety and depression rates. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 39, 384–384. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2300

de Witte, M., Spruit, A., van Hooren, S., Moonen, X., and Stams, G.-J. (2019). Effects of music interventions on stress-related outcomes: a systematic review and two meta-analyses. Health Psychol. Rev. 14, 294–324. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2019.1627897

DeNora, T. (1999). Music as a technology of the self. Poetics 27, 31–56. doi: 10.1016/S0304-422X(99)00017-0

Feter, N., Caputo, E. L., Doring, I. R., Leite, J. S., Cassuriaga, J., Reichert, F. F., et al. (2021). Sharp increase in depression and anxiety among Brazilian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the PAMPA cohort. Public Health 190, 101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.11.013

Filho, N. H., Federal, U., Grande, R., Ant, S. M., Teixeira, P., Federal, U., et al. (2011). A estrutura fatorial da escala CES-D em estudantes universitários Brasileiros. Avaliação Psicol. 10, 91–97.

Finn, S., and Fancourt, D. (2018). “The biological impact of listening to music in clinical and nonclinical settings: a systematic review,” in The Arts and The Brain: Psychology and Physiology Beyond Pleasure, eds J. F. Christensen and A. Gomila (Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V.), 173–200. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.03.007

Fitzpatrick, K. M., Harris, C., and Drawve, G. (2020). Living in the midst of fear: depressive symptomatology among US adults during the COVID−19 pandemic. Depress. Anxiety 37, 957–964. doi: 10.1002/da.23080

Fullana, M. A., Hidalgo-Mazzei, D., Vieta, E., and Radua, J. (2020). Coping behaviors associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J. Affect. Disord. 275, 80–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.027

Goularte, J. F., Serafim, S. D., Colombo, R., Hogg, B., Caldieraro, M. A., and Rosa, A. R. (2021). COVID-19 and mental health in Brazil: psychiatric symptoms in the general population. J. Psychiatr. Res. 132, 32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.021

Hall, R. C. W., Hall, R. C. W., and Chapman, M. J. (2008). The 1995 Kikwit Ebola outbreak: lessons hospitals and physicians can apply to future viral epidemics. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 30, 446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.003

Hall, S. (2020). This is How COVID-19 is Affecting the Music Industry. World Econ. Forum. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/this-is-how-covid-19-is-affecting-the-music-industry/ (accessed December 28, 2020).

Hawryluck, L., Gold, W., Robinson, S., Pogorski, S., Galea, S., and Styra, R. (2005). SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 354–355. doi: 10.3201/eid1102.040760

Ho, C. S., Chee, C. Y., and Ho, R. C. (2020). Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 49, 155–160. doi: 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.202043

Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., McBride, O., Murphy, J., Karatzias, T., Bentall, R. P., et al. (2020). Anxiety and depression in the Republic of Ireland during the COVID−19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 142, 249–256. doi: 10.1111/a.13219

Islam, M. A., Barna, S. D., Raihan, H., Khan, M. N. A., and Hossain, M. T. (2020). Depression and anxiety among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: a web-based cross-sectional survey. PLoS One 15:e0238162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238162

Juslin, P. N., Barradas, G. T., Ovsiannikow, M., Limmo, J., and Thompson, W. F. (2016). Prevalence of emotions, mechanisms, and motives in music listening: a comparison of individualist and collectivist cultures. Psychomusicology 26, 293–326. doi: 10.1037/pmu0000161

Juslin, P. N., and Västfjäll, D. (2008). Emotional responses to music: the need to consider underlying mechanisms. Behav. Brain Sci. 31, 559–575. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X08005293

Kar, S. K., Yasir Arafat, S. M., Kabir, R., Sharma, P., and Saxena, S. K. (2020). “Coping with mental health challenges during COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19),” in Medical Virology: From Pathogenesis to Disease Control, ed. S. Saxena (Singapore: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-4814-7_16

Krause, A. E., Dimmock, J., Rebar, A. L., and Jackson, B. (2020). Music listening predicted improved life satisfaction in university students during the early stages of the COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 11:631033. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.631033

Leubner, D., and Hinterberger, T. (2017). Reviewing the effectiveness of music interventions in treating depression. Front. Psychol. 8:1109. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01109

Liu, S., Yang, L., Zhang, C., Xiang, Y.-T., Liu, Z., Hu, S., et al. (2020). Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 7, e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8

Lonsdale, A. J., and North, A. C. (2011). Why do we listen to music? A uses and gratifications analysis. Br. J. Psychol. 102, 108–134. doi: 10.1348/000712610X506831

Maratos, A., Gold, C., Wang, X., and Crawford, M. (2008). Music therapy for depression. cochrane database. Syst. Rev. 11:CD004517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004517.pub2

Osuch, E. A., Bluhm, R. L., Williamson, P. C., Théberge, J., Densmore, M., and Neufeld, R. W. J. (2009). Brain activation to favorite music in healthy controls and depressed patients. Neuroreport 20, 1204–1208. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832f4da3

Pan, Y. Y., Sun, X. Y., Dang, Y. N., Chen, M., Wang, L., and Shen, L. (2020). Effect of music intervention on depression in graduate students. Music Educ. Res. 23, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2020.1847058

Panteleeva, Y., Ceschi, G., Glowinski, D., Courvoisier, D. S., and Grandjean, D. (2017). Music for anxiety? Meta-analysis of anxiety reduction in non-clinical samples. Psychol. Music 46, 473–487. doi: 10.1177/0305735617712424

Papandreou, C., Arija, V., Aretouli, E., Tsilidis, K. K., and Bulló, M. (2020). Comparing eating behaviours, and symptoms of depression and anxiety between Spain and Greece during the COVID−19 outbreak: cross−sectional analysis of two different confinement strategies. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 28, 836–846. doi: 10.1002/erv.2772

Polanco-Roman, L., Jurska, J., Quiñones, V., and Miranda, R. (2015). Brooding, reflection, and distraction: relation to non-suicidal self-injury versus suicide attempts. Arch. Suicide Res. 19, 350–365. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2014.981623

Puyat, J. H., Ahmad, H., Avina-Galindo, A. M., Kazanjian, A., Gupta, A., Ellis, U., et al. (2020). A rapid review of home-based activities that can promote mental wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 15:e0243125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243125

R Core Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Found. Stat. Comput. Available online at: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed December 28, 2020).

R Development Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.6.3

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

Revelle, W. (2020). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=psych (accessed March 27, 2021).

Ribeiro, F., and Leist, A. (2020). Who is going to pay the price of Covid-19? Reflections about an unequal Brazil. Int. J. Equity Health 19:91. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01207-2

Ribeiro, F. S., Braun Janzen, T., Passarini, L., and Vanzella, P. (2021a). Exploring changes in musical behaviors of caregivers and children in social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychol. 12:633499. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633499

Ribeiro, F. S., Santos, F. H., Anunciação, L., Barrozo, L., Landeira-Fernandez, J., and Leist, A. K. (2021b). Exploring the frequency of anxiety and depression symptoms in a Brazilian sample during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:4847. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094847

Rodero, E. (2020). La radio: el medio que mejor se comporta en las crisis. Hábitos de escucha, consumo y percepción de los oyentes de radio durante el confinamiento por el Covid-19. El Prof. Inf. 29:e290306. doi: 10.3145/epi.2020.may.06

Rodrigues, M. E., da, S., Silveira, T. B., da, Jansen, K., Cruzeiro, A. L. S., et al. (2012). Risco de suicídio em jovens com transtornos de ansiedade: estudo de base populacional. Psico USF 17, 53–62. doi: 10.1590/S1413-82712012000100007

Rutter, M. (2012). Resilience as a dynamic concept. Dev. Psychopathol. 24, 335–344. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000028

Rzewuska, M., de Azevedo-Marques, J. M., Coxon, D., Zanetti, M. L., Zanetti, A. C. G., Franco, L. J., et al. (2017). Epidemiology of multimorbidity within the Brazilian adult general population: evidence from the 2013 National Health Survey (PNS 2013). PLoS One 12:e0171813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171813

Saarikallio, S. (2012). “Cross-cultural approaches to music and health,” in Music, Health, and Well-Being, eds R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, and L. Mitchell (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 477–490.

Saarikallio, S., Alluri, V., Maksimainen, J., and Toiviainen, P. (2020). Emotions of music listening in Finland and in India: comparison of an individualistic and a collectivistic culture. Psychol. Music 30, 307–340. doi: 10.1177/0305735620917730

Sachs, M. E., Damasio, A., and Habibi, A. (2015). The pleasures of sad music: a systematic review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9:404. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00404

Sakka, L. S., and Juslin, P. N. (2018). Emotion regulation with music in depressed and non-depressed individuals. Music Sci. 1:205920431875502. doi: 10.1177/2059204318755023

Santos, É. G., and Siqueira, M. M. (2010). Prevalência dos transtornos mentais na população adulta brasileira: uma revisão sistemática de 1997 a 2009. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 59, 238–246. doi: 10.1590/S0047-20852010000300011

Schäfer, T., Sedlmeier, P., Städtler, C., and Huron, D. (2013). The psychological functions of music listening. Front. Psychol. 4:511. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00511

Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., and Morris, A. S. (2003). Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Dev. 74, 1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x

Sloboda, J. A., and O’Neill, S. A. (2001). “Emotions in everyday listening to music,” in Music and Emotion: Theory and Research. Series in Affective Science, eds P. N. Juslin and J. A. Sloboda (Newcastle: Oxford University Press), 415–429.

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., and Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 15, 194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., and Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalised anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Stewart, J., Garrido, S., Hense, C., and McFerran, K. (2019). Music use for mood regulation: self-awareness and conscious listening choices in young people with tendencies to depression. Front. Psychol. 10:1199. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01199

Tang, L., Bie, B., Park, S. E., and Zhi, D. (2018). Social media and outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases: a systematic review of literature. Am. J. Infect. Control. 46, 962–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.02.010

Trabelsi, K., Ammar, A., Masmoudi, L., Boukhris, O., Chtourou, H., Bouaziz, B., et al. (2021). Globally altered sleep patterns and physical activity levels by confinement in 5056 individuals: ECLB COVID-19 international online survey. Biol. Sport. 38, 495–506.

Van Bortel, T., Basnayake, A., Wurie, F., Jambai, M., Koroma, A. S., Muana, A. T., et al. (2016). Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community and international levels. Bull. World Health Organ. 94, 210–214. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.158543

Viana, M. C., and Andrade, L. H. (2012). Lifetime prevalence, age and gender distribution and age-of-onset of psychiatric disorders in the São Paulo Metropolitan area, Brazil: results from the São Paulo Megacity Mental health survey. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 34, 249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.rbp.2012.03.001

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., et al. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., and Müller, K. (2018). dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed March 05, 2021).

Wilhelm, K., Gillis, I., Schubert, E., and Whittle, E. L. (2013). On a blue note: depressed peoples’ reasons for listening to music. Music Med. 5, 76–83. doi: 10.1177/1943862113482143

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online at: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed January 10, 2021).

Zanon, C., Lessa, J. P. A., and Dellazzana-Zanon, L. L. (2018). Acquiescence in self-report personality assessment: a comparison between methods. Inter. Am. J. Psychol. Assess. 17, 428–438. doi: 10.15689/ap.2018.1704.3.03

Keywords: COVID-19, social distancing, depression, music listening, Brazil

Citation: Ribeiro FS, Lessa JPA, Delmolin G and Santos FH (2021) Music Listening in Times of COVID-19 Outbreak: A Brazilian Study. Front. Psychol. 12:647473. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647473

Received: 30 December 2020; Accepted: 06 April 2021;

Published: 21 May 2021.

Edited by:

Melanie Wald-Fuhrmann, Max Planck Society (MPG), GermanyReviewed by:

Hamdi Chtourou, University of Sfax, TunisiaCopyright © 2021 Ribeiro, Lessa, Delmolin and Santos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fabiana Silva Ribeiro, ZmFiaWFuYXJpYmVpcm9wc2lAZ21haWwuY29t; Flávia H. Santos, ZmxhdmlhLnNhbnRvc0B1Y2QuaWU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.