- 1Virtual-Physical Arts Research Center, Educational Science Research Institute of Shenzhen, Shenzhen, China

- 2School of Psychology, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

Research has consistently found that poor family functioning is a risk factor for adolescents' internalizing problems. However, studies of the mediating and moderating mechanisms underlying this relation are insufficient. In this study, we explore the association between family functioning and adolescents' internalizing problems by testing the mediating roles of positive youth development (PYD) attributes and the moderating role of migrant status. A large cross-sectional sample of 11,865 Chinese adolescents (mean age = 14.45 years, standard deviation = 1.55 years) were used to measure internalizing problems, family functioning, PYD, migrant status, and other demographic information. After controlling for covariates (age, gender, grade, and socioeconomic status), the results revealed that PYD mediated the relation between family functioning and internalizing problems. Moreover, migrant status moderated the relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems. Specifically, the effects of family functioning on internalizing problems were stronger among local-born adolescents than among migrant adolescents. The findings indicate that improving family functioning and PYD attributes may be promising approaches to prevent/reduce adolescent internalizing problems.

Introduction

Adolescence is a period of rapid physical, psychological, and social development. In this period, problem behaviors of adolescents can frequently occur, such as internalizing problems. Internalizing problems is generally considered a branch of psychopathology that involves emotional or mood disorders (Graber and Sontag, 2009). Currently, studies have indicated that teenagers are the group with the highest incidence of internalizing problems (Shek, 2002a; Graber and Sontag, 2009; Jamnik and Dilalla, 2019), which is harmful to their healthy development (Rosenfield et al., 2005), including school maladaptation (Jankowska et al., 2015), low social functioning (Ohtani et al., 2015), sleep disturbance (Pieters et al., 2015), substance use (Miettunen et al., 2014), and even self-harm and suicidal behavior (Lee et al., 2006). Despite extensive research exploring the influencing factors of internalizing problems among adolescents in the Western countries, studies are inadequate in China. China has the second largest youth population in the world, and the mental health problems of adolescents are increasingly serious (Xiong et al., 2017). Thus, there is an urgent need to identify the relevant factors and underlying mechanisms of adolescent internalizing problems in order to develop effective prevention/intervention programs.

According to the ecological model, the family environment is the most direct and predominant environment of an individual's development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Based on this model, a series of studies have explored the relationships between family factors and adolescents' internalizing problems (Ha et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2013). Among these factors, family functioning plays an especially important role in adolescent development. Generally, family functioning is regarded as the ability of the family to perform its functions, such as meeting the physical and emotional needs of its members (Dickstein, 2002; Eichelsheim, 2011). Increasing evidence suggests that family functioning is significantly associated with adolescents' internalizing problems (Shek, 2002a; Ma et al., 2013), such as anxiety and depression (Sheeber et al., 1997, 2001; Guberman and Manassis, 2011; Stark et al., 2012). For example, previous studies have found that adolescents with strong family cohesion will develop less anxiety and fewer withdrawal behaviors (Roosa et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 2001). In contrast, poor family relationships (e.g., parent–child conflicts and conflicts between parents) increase the risk of depressive symptoms among adolescents (Formoso et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2011; Claire et al., 2013).

Although previous studies indicated that family functioning was negatively associated with internalizing problems, the underlying mediating mechanism (i.e., how family functioning influences internalizing problems) and moderating mechanism (i.e., when family functioning is related to internalizing problems, or the different influence of family functioning on internalizing problems in different groups) remain unclear, particularly with regard to Chinese adolescents. Therefore, in this study, we constructed a moderated mediation model to test the mediating role of positive youth development (PYD) and the moderating role of migrant status on the relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems in Chinese adolescents.

The Mediating Role of PYD

To comprehensively study adolescents' positive development, the concept of PYD was brought forward, consisting 15 positive developmental qualities (i.e., bonding, resilience, social competence, recognition for positive behavior, emotional competence, cognitive competence, behavioral competence, moral competence, self-determination, self-efficacy, clear and positive identity, belief in the future, prosocial involvement, prosocial norms, and spirituality), and emphasizing the development potential of teenagers to cope with their growing environment. An increasing number of studies have suggested that the characteristics of PYD play an important role in the healthy development of adolescents (Chang and Zhang, 2013). The development assets framework emphasizes the joint effects of external assets (e.g., environmental characteristics) and internal assets (e.g., psychological resources) on adolescent development (Benson et al., 2007). Moreover, the model has also stressed that external resources may impact adolescent behavioral performance through internal resources (Chang and Zhang, 2013). Empirical studies have supported this view. For example, previous studies found that healthy family functioning (e.g., good family communication) is correlated with higher level of positive development (e.g., greater self-esteem and resilience), as well as a lower likelihood of anxiety and depression in adolescents (Russell et al., 2000; Stark et al., 2012; Yee and Sulaiman, 2017). PYD attributes (e.g., resilience, prosocial behavior, etc.) were significantly associated with less internalizing problems among adolescence such as adolescent depression (Catalano et al., 2002; Reivich et al., 2013; Shek and Sun, 2013; Leung and Shek, 2015; Leung et al., 2017). Additionally, favorable family functioning (e.g., frequent communication, family harmony, a good parent–child relationship) can promote PYD features such as resilience, self-efficacy, socioemotional competence, and prosocial behaviors in adolescents (Renzaho et al., 2013; Cigala et al., 2014; Reitz et al., 2014; Yee and Sulaiman, 2017), which may further predict the lower likelihood of internalizing problems (e.g., depression; Reivich et al., 2013; Wang and Saudino, 2015; Rocchino et al., 2017; Yee and Sulaiman, 2017). Based on the development assets framework and previous studies, PYD is expected to act as an important factor that mediates the relationships between family functioning and internalizing problems (Hypothesis 1).

The Moderating Role of Migrant Status

According to person–context interaction theory, the interaction between the individual and the environment determines individual development (Magnusson and Stattin, 1998; Lerner et al., 2006), which indicates that the negative effect of unhealthy family functioning on adolescents may vary from individual to individual (Claire et al., 2013). Several studies have suggested that migrant status may be a risk factor exacerbating the impact of a poor family environment (e.g., family functioning and parent–child relationship) on psychological well-being (e.g., life satisfaction), which may be attributed to environmental adaptation pressure and acculturation stress (Cheung, 2013; Wang et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2019). For instance, researchers have reported that poor family functioning had a more negative effect on life satisfaction in migrant children than in local-born children (Hou et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2019). However, several other studies took the opposite view, arguing that despite the acculturative stress, migrant students had better academic performance and higher levels on a psychological well-being index than their local-born counterparts, which may be attributed to increased resilience from migration (Fan et al., 2009; García-Coll and Marks, 2012; Serap et al., 2018). For example, previous research found that strict parental discipline had a greater negative impact on problem behaviors in local-born children but not in immigrant children (Hackett et al., 1991). These findings indicate that whether migrant status plays a risk-buffering or risk-intensifying role in the relationship between family environmental factors and adolescent mental health remains inconsistent and requires further research. Based on person–context interaction theory and previous studies, we hypothesized that migrant status moderates the link between family functioning and internalizing problems (Hypothesis 2), as well as the link between family functioning and PYD (Hypothesis 3).

The Present Study

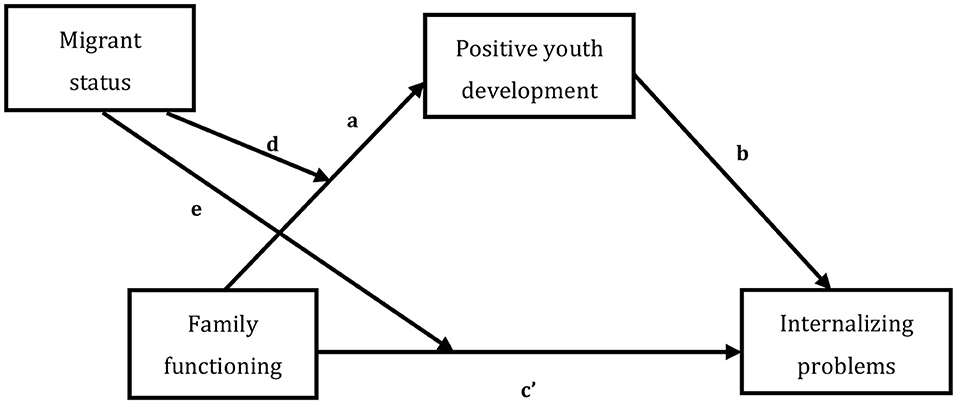

In summary, based on ecological theory, the development assets framework and person–context interaction theory, we constructed a moderated mediation model (Figure 1) to explore the effects of family functioning, PYD, and migrant status on adolescents' internalization of problems. Specifically, this study attempted to examine the mediating effects of PYD and migrant status on the association between family functioning and internalizing problems in adolescents. We expect that the results of the study can provide suggestions for the prevention of and intervention in adolescent problem behaviors.

Figure 1. The moderated mediation model. a = the relation between family functioning and positive youth development; b = the relation between positive youth development and internalizing problems; c′ = the relation between family functioning and internalizing problems; d = the moderating effect of migrant/local-born adolescents on the relation between family functioning and positive youth development. e = the moderating effect of migrant/local-born adolescents on the relation between family functioning and internalizing problems.

Methods

Participants and Sampling

Participants were recruited from high schools in the city of Shenzhen in southern China. Shenzhen is a typical migrant city in China. Up to 2018, there were ~390 middle and high schools in Shenzhen, with 448,000 students enrolled in school, of which nearly 40% were migrant students (Anonymous, 2018). Thus, it is appropriate to select Shenzhen for immigration-related research. With the assistance of the Shenzhen Educational Science Research Institute, an investigation was conducted using a large population for multistage random sampling. Based on the total number of schools in Shenzhen and our sampling ratio, we invited 70 public middle and high schools (seven schools in each of 10 districts) to participate in the study, and a total of 67 schools accepted the invitation. In each school, 200 students who agreed and had consent from their guardians to participate in the study were randomly recruited.

Initially, 12,244 adolescents participated, and the valid data from 11,865 were ultimately studied. The mean age of the adolescents was 14.45 years [standard deviation (SD) = 1.55 years, range = 12–18 years], including 5,883 boys (49.6%) and 5,982 girls (50.4%). With regard to the grade levels, 4,250 students (35.8%) were in the seventh grade, 3,498 students (29.5%) were in the eighth grade, 1,159 students (9.8%) were in the ninth grade, 1,356 students (11.4%) were in the 10th grade, 841 students (7.1%) were in the 11th grade, and 761 students (6.4%) were in the 12th grade. The sample included 9,344 local-born adolescents (78.8%) and 2,521 migrant adolescents (21.2%); all the migrant adolescents (i.e., internal migration within China) came from cities other than Shenzhen, and they had similar ethnic and cultural backgrounds (i.e., collectivist culture) as the adolescents born in Shenzhen. The average duration of their migration to Shenzhen was 7.82 years (SD = 3.538 years).

Procedure

The study was performed in classroom settings at participants' schools using written questionnaires. Each school received official approval and obtained the informed consent of participants and their guardians in advance. Recruitment and data collection procedures were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Shenzhen University. Twenty trained research assistants took charge of the data collection, with teams of two to three research assistants responsible for 40 to 50 adolescents. Participants were randomly assigned to different classrooms. To maximize the effectiveness of self-reporting, we conducted pilot testing with standardized instructions and assured participants that their answers would be anonymous and confidential.

Measures

Demographic Information

Demographic information consisted of age, gender, grade, migrant status, parental educational levels, and family monthly income. Migrant status was determined by the yes/no question, “Are you a migrant emigrating to Shenzhen from other cities?” The family socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed via parental educational level and family monthly income. Specifically, there were four options for parental educational level: (a) middle school graduation or lower, (b) high school or junior college graduation, (c) bachelor's degree graduation, and (d) master's degree graduation or higher. With regard to family monthly income, there were five available options: (a) 2,000–3,999 CNY per month, (b) 4,000–5,999 CNY per month, (c) 6,000–7,999 CNY per month, (d) 8,000–9,999 CNY per month, and (e) more than 10,000 CNY per month. Following the suggestion of Kraus et al. (2009), we standardized parental educational level and family monthly income and then summed them for the indicator of family SES.

Family Functioning

Family functioning was assessed by the Family Function core scale, which is a revised version of the Chinese Family Assessment Instrument (C-FAI) adapted by Shek (2002b). The C-FAI is suitable for adolescent participants with a Chinese cultural background and has five dimensions: communication, mutuality, conflict, parental concern, and parental control. For the current study, we selected three subscales (nine items) of the C-FAI: communication (three items, e.g., “My parents and I often have conversations”), mutuality (three items, e.g., “My family lives in harmony”), and conflict (three items, e.g., “We have a lot of conflict,” reverse scoring). Items were answered on a five-point scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = very dissimilar, 5 = very similar). The mean value of each subscale was used as an indicator of family functioning. The higher the score, the better the family's functioning. Previous studies have confirmed the reliability and validity of the C-FAI (e.g., Leung and Shek, 2015). For the current study, Cronbach α for the questionnaire was 0.87.

Positive Youth Development

PYD was assessed using the Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale (Shek et al., 2007). Because Chinese teenagers generally have no religious belief, we chose 14 dimensions of the scale other than spirituality: bonding (three items), resilience (three items), social competence (three items), recognition for positive behavior (three items), emotional competence (three items), cognitive competence (three items), behavioral competence (three items), moral competence (three items), self-determination (three items), self-efficacy (two items), clear and positive identity (three items), belief in the future (three items), prosocial involvement (three items), and prosocial norms (three items). A sample item was “If I'm sad, I can express my emotions properly.” Items were answered on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 to 6 (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree), and the average of the total score was used as an indicator of adolescent positive development. For the current study, Cronbach α for the questionnaire was 0.98.

Internalizing Problems

To measure participants' internalization of problems, we selected the evaluation scale for internalizing problems by teenagers, which is a subscale of the Evaluation Scale for Risk Behavior of Teenagers established by Bai (2007). The scale is mainly divided into 4 dimensions and 21 items: anxiety (six items, e.g., “I seem to be easily frightened”), depression (nine items, e.g., “I am considered a quiet, perverse person”), neuroticism (three items, e.g., “I often feel my heart beating fast”), and withdrawal (three items, e.g., “I dare not speak loudly in front of many people, and I always hide away quietly”). Items were answered on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = never, 5 = always). The higher the participant's score, the more serious their internalization of problems. For the current study, Cronbach α for this questionnaire was 0.96.

Statistical Analyses

After entering the data into a computer, we used SPSS 21.0 software for data analysis. The steps are as follows: common method biases analysis was performed first; second, descriptive statistics of the main variables and Pearson correlation analysis were conducted; third, a non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U-test) was done to determine the differences with migrant status for all factors; fourth, the PROCESS plug-in developed by Hayes was used, with models four and eight selected to test the mediation model and the moderated mediation model, respectively (Hayes, 2013). The confidence interval (CI) was 95%, and there were 5,000 bootstrap samples. That the 95% CI does not contain zero suggests a significant conditional indirect effect. Previous studies found that age, gender, grade, and family SES were significantly correlated with adolescents internalizing problems (Leadbeater et al., 1999; Bradley and Corwyn, 2002; Yu et al., 2017), so we controlled for gender, age, and SES as covariates.

Results

Testing of Common Method Biases

Because of the self-report method of data collection, there may be a common method bias. Therefore, the subjects were asked to complete the questionnaire anonymously, and some items were controlled by reverse questions. Further, Harman's single-factor analysis was used to test the common method variance effect (Xiong et al., 2012). The results showed that the variance interpretation rate of the first common factor was 33.70%, less than the critical standard of 40%, indicating that the influence of the common method bias in this study was relatively minor.

Preliminary Analyses

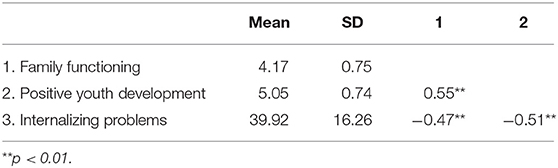

First, the data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including the mean and SD of family functioning (mean = 4.17, SD = 0.75), PYD (mean = 5.05, SD = 0.74), and internalizing problems (mean = 39.92, SD = 16.26). The family functioning and PYD levels of the surveyed adolescents were medium and above. In addition, the score for internalizing problems was lower than the norm (second-year junior high school students, mean = 44.51). Next, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted on family functioning, PYD, and internalizing problems, and we found there was a significant correlation among the three (Table 1). Family functioning was positively correlated with PYD and negatively correlated with internalizing problems. PYD was negatively correlated with internalizing problems.

In addition, a non-parametric test was used to determine the differences that migrant status made with all factors. We tested the data for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk method, with family functioning, PYD, and internalizing problems as dependent variables and migrant status as a factor and found that all p-values were <0.001, indicating that the data were not normally distributed. Thus, we used the Mann–Whitney U-test of two independent samples. Results showed that the average rank of migrant adolescents for family functioning (average rank = 5,413.81) was lower than that of local-born adolescents (average rank = 6,073.08), z = −8.599, p < 0.001; the average rank of migrant adolescents on PYD (average rank = 5,714.44) was lower than that of local-born adolescents (average rank = 5,991.97), z = −3.612, p < 0.001; the average rank of migrant adolescents on internalizing problems (average rank = 6,212.15) was lower than that of local-born adolescents (average rank = 5,857.69), z = −4.614, p < 0.001.

Testing for the Mediation Model

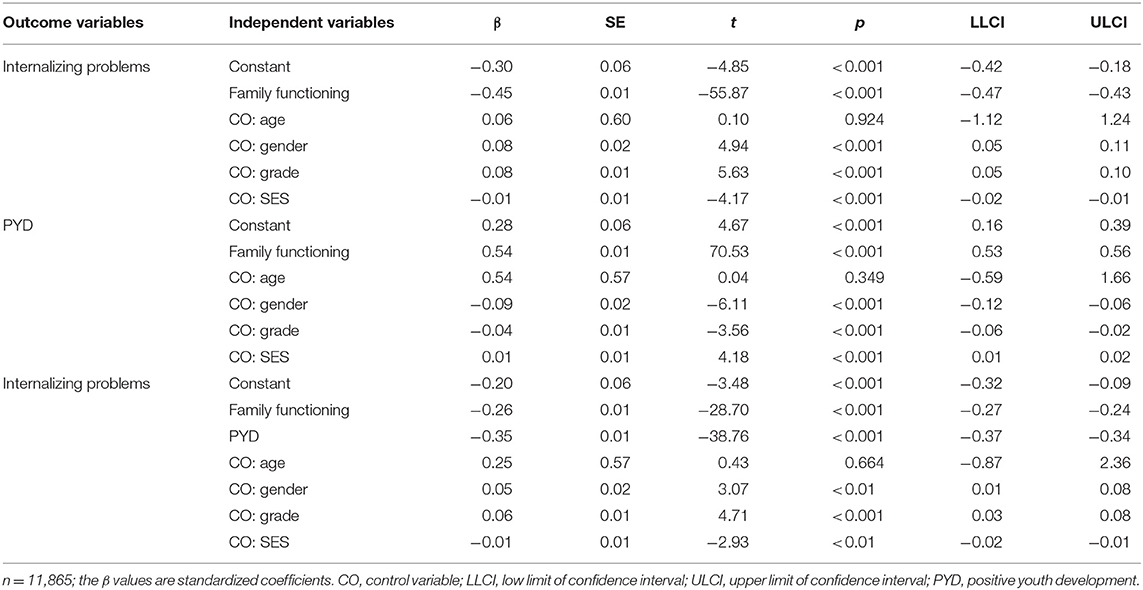

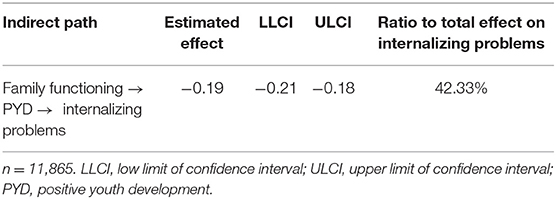

To examine Hypothesis 1, model 4 of the PROCESS macro was used with age, gender, grade, and SES being controlled as the covariates. As shown in Table 2, family functioning was negatively associated with internalizing problems (β = −0.45, p < 0.001) in the absence of a mediator, whereas family functioning was positively correlated with PYD (β = 0.54, p < 0.001). In addition, when covariates and family functioning were controlled for, PYD was negatively associated with internalizing problems (β = −0.35, p < 0.001). When covariates and PYD were controlled for, the relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems was significantly negative (β = −0.26, p < 0.001). Finally, to examine the mediation model, the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method was used. As shown in Table 3, the indirect effect of PYD was −0.19 (95% CI = −0.21 to −0.18); the empirical 95% CI did not contain zero, indicating that the mediation effect was significant. Furthermore, the mediation effect accounted for 42.33% of the total effect of the relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Testing for the Moderated Mediation Model

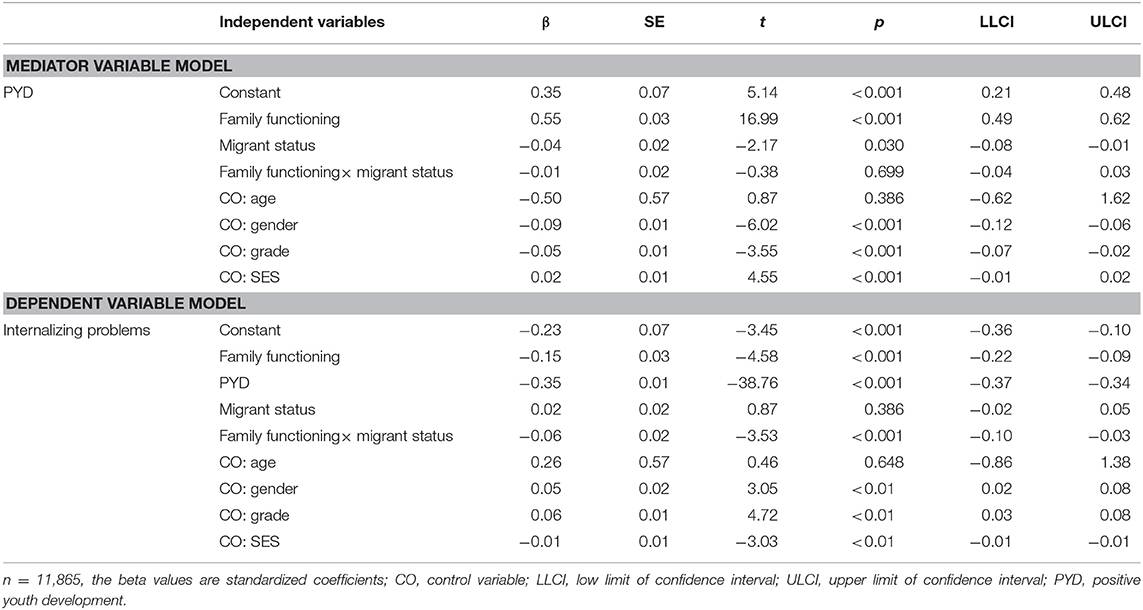

To examine Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3, model 8 of the PROCESS macro was used, with age, gender, and SES controlled for as the covariates. The moderated mediation analyses are shown in Table 4. After controlling for demographic covariates, the mediator variable model indicated that family functioning was positively associated with PYD (β = 0.55, p < 0.001), and the interaction between family functioning and migrant status was not significant (β = −0.01, p = 0.699). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was not supported. As shown in the dependent variable model, family functioning was negatively correlated with internalizing problems (β = −0.15, p < 0.001), whereas the interaction between family functioning and migrant status was negatively correlated with internalizing problems (β = −0.06, p < 0.001). Therefore, migrant status moderated the relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems, and Hypothesis 2 was supported.

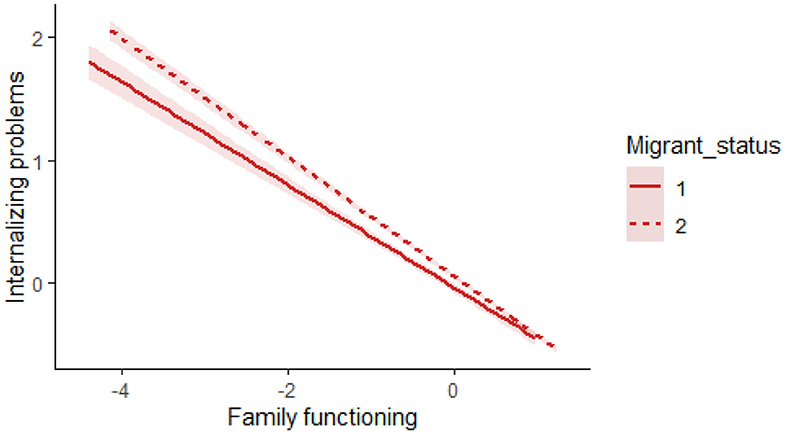

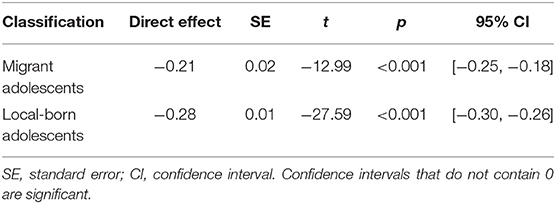

These results indicated that migrant status could moderate the relationships between family functioning and internalizing problems but could not moderate the relationships between family functioning and PYD. To more completely understand the moderating effects of migrant status, R Studio was used to create the image in Figure 2, which describes the relationships between family functioning and internalizing problems for two conditions of migrant status (i.e., migrant adolescents and local-born adolescents). In addition, the study further tested the conditional direct effect and indirect effect. As can be observed in Table 5, the effect of family functioning on internalizing problems was observed whether adolescents were migrants (β = −0.21, p < 0.001) or local-born (β = −0.28, p < 0.001). The 95% CI did not contain zero.

Figure 2. The moderating role of migrant status in the relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems. The solid line (migrant status is 1) indicates the group of migrant adolescents; the dotted line (migrant status is 2) indicates the group of local-born adolescents. The shadowed areas represent standard errors.

Table 5. Conditional direct effect of family functioning on internalizing problems for two migrant statuses.

Discussion

Based on a large-scale sample, the present study examined a moderated mediation model and revealed the mechanism underlying the relationships between family functioning and internalizing problems among Chinese adolescents. The results showed that PYD significantly mediated the association between family functioning and internalizing problems in Chinese adolescents, and migrant status significantly moderated the relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems. These findings may provide theoretical and practical implications for the positive development of Chinese adolescents.

The Mediating Role of Positive Youth Development

The study found that PYD partially accounted for the relationships between family functioning and internalizing problems among adolescents (H1 was supported), which was in line with previous studies (Catalano et al., 2002; Benson, 2006; Sun and Shek, 2013). In other words, family functioning not only can directly affect adolescents' internalizing problems but also can affect adolescents' internalizing problems through PYD attributes.

The development assets framework and the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 2002; Benson et al., 2007) suggest that individuals' psychological resources may be weakened by a poor external environment, which may further lead to psychological stress. Such mental stress usually causes individuals to experience internalizing problems such as anxiety and depression (Scales et al., 2000; Hobfoll et al., 2003). By analogy, if the parent–child relationship is unsound, and family communication is lacking, this may negatively affect the formation of an adolescent's positive individual traits and psychological resources. Adolescents with deficient positive traits (e.g., resilience, emotional regulation ability) may not cope with adverse situations or stressful events, and these factors may ultimately increase the risk for the occurrence of internalizing problems (Lerner, 2007; Lougheed and Hollenstein, 2012). The findings of the present study indicate that improving PYD attributes may be a promising approach for reducing the risk of adolescent internalizing problems.

The Moderating Role of Migrant Status

This study found that the effect of family functioning on internalizing problems was stronger among local-born adolescents than among migrant adolescents. Specifically, when family functioning was in good condition, there were minimal internalizing problems in either group, and there were no significant differences. However, when the family functioning was poor, internalizing problems increased significantly in both groups, and the problems were more serious in the group of local-born adolescents. These findings indicate that migrant status might serve as a buffer to alleviate the negative effects on adolescent development of unhealthy family functioning, which is in line with previous research (e.g., Hackett et al., 1991). The following factors may explain the findings.

The resiliency model suggests that in confronting the acculturation stress of migration, the migrant family gradually adjusts, which fosters resilience and personal strengths (e.g., toughness and grit; Greeff and Holtzkamp, 2007; Gui et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014; Lan and Radin, 2020). Adolescents with high levels of resilience may be more proactive in adjusting their emotions and finding solutions to problems, which may, in turn, help prevent or reduce depression in migrant adolescents (Wingo et al., 2010; Masten and Tellegen, 2012; Ye et al., 2016). Moreover, researchers have suggested that aside from resilience, migrant youths may have some unobserved traits such as ambition or aspiration that enable them to cope with the transitional stress more independently and perhaps be less affected by poor family functioning (Georgiades et al., 2007; Chiswick et al., 2008; Sheidow et al., 2013). Several studies have reported that migrant youths outperform their local-born counterparts in school; they may be more ambitious and industrious than their native peers in order to achieve more academically (Fuligni, 1997; Motti-Stefanidi and Masten, 2013; Chen et al., 2019). These expectations of academic performance may buffer the influence on their mental health of poor family functioning. This study's findings indicated that migrant status may buffer the influence of poor family functioning on internalizing problems.

We found that migrant status had no significant moderating effect on the association of family functioning with PYD, which is similar to previous studies (e.g., Wissink et al., 2006). The findings indicate that regardless of whether adolescents are migrants, family functioning has an impact on their positive development, which reemphasizes the importance of family functioning and its general applicability to developing PYD attributes. Several factors may explain the non-significant moderating effect. First, almost all the migrant youths we investigated were attending public schools. Previous studies have demonstrated that migrant students in public schools exhibited greater psychosocial competencies (e.g., self-esteem) than migrant students in private schools, and they were not that different from their local peers (Li et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010; Yuan, 2011). Our study confirmed previous research and found that the difference in the scores of PYD attributes between local-born and migrant children was fairly small (effect size = −0.05, Cohen d = −0.09). This leads to more similarity than difference in the effect of family functioning on PYD and thus leads to insignificant results. The second factor may be that the ratings of PYD attributes among both migrant and local-born adolescents were relatively positive (mean = 5.00 of 6.00 points for migrant adolescents vs. mean = 5.06 for local-born adolescents); the limited variation in PYD score may not be sufficient to be predicted by local and migrant children's family functioning (i.e., the ceiling effect; Weng et al., 2019; Chi et al., 2020).

Limitation and Implications

There were several limitations to the present study. First, data from the cross-sectional design are unable to test the casual relationship that occurs over time between family functioning and internalizing problems in adolescents (Hu et al., 2009). To better verify the moderated mediation model, a future longitudinal study is required. Additionally, the direction between variables in our study was unidirectional (Figure 1), but the arrow direction between PYD and family functioning could also be bidirectional. Thus, cross-lagged longitudinal regression studies will be conducted to see if there are bidirectional relationships between the variables. Second, the measurement of family functioning in this study only included unilateral data from adolescents, and there is a lack of data from other paths, such as parents and teachers. Future research may fill this gap. Third, our study was conducted only in Shenzhen, and the generalizability of the findings is open to discussion. Thus, a nationwide survey is required in the future. Finally, the internal consistency of the questionnaires for PYD and internalizing problems in this study is too high, which may indicate that some items are testing the same question in different guises. This may also be the reason for the ceiling effect on PYD scores of migrant and local-born adolescents. Therefore, careful consideration is needed in the selection of scales for future research.

Although there are limitations, our findings have several theoretical and practical implications. First, the present study found a significant negative relationship between family functioning and internalizing problems, which indicates that adverse family circumstances may correlate with adolescent problem behaviors. Thus, special help is needed for adolescents in poorly functioning families to reduce their propensity for internalizing problems. For parents, better communication, decreasing conflict, and parental caring may be ensured to prevent children from internalizing problems. Second, a significant mediating role was found of PYD on the relationships between family functioning and internalizing problems. Thus, relevant courses or activities should be set up to cultivate and improve levels of PYD features to promote the adoption of positive strategies to cope with adverse situations and negative emotions. For policymakers, a PYD program could be carried out (e.g., Project P.A.T.H.S. in Hong Kong) to promote the positive development of youths (Shek and Sun, 2013). Third, we found a significant moderating role of migrant status on the relationships between family functioning and internalizing problems, which may contribute to a better understanding of the mechanism behind these correlations in adolescents. Specifically, migrant status could buffer the influence of poor family functioning on internalizing problems among adolescents in the study. The results make efforts important for reducing the effects of negative stereotypes about migrant adolescents and, most importantly, to help them enhance self-efficacy, resist adverse environments, and reduce problem behaviors.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the project is building another project based on this dataset. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to eGlubGljaGlAMTI2LmNvbQ==.

Ethics Statement

Recruitment and data collection procedures were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (No:2020005) of Shenzhen University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

QW and XC conceived the study. QW conducted all data collection work. SP conducted statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. XC critically reviewed the manuscript. XC and SP revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Grant No. 16CSH049 from National Social Science Foundation. Educational Science Planning Project of Guangdong Province: Study and Practice of the Three Preconditions System of Psychological Crisis in Primary and Secondary Schools (2019YQJK059).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Anonymous (2018). Shenzhen Municipal Statistics Bureau. Shenzhen statistical bulletin on national economic and social development 2018. Available online at: http://tjj.sz.gov.cn/

Bai, J. (2007). Establishment of Evaluation Scale for Risk Behavior of Teenagers. Doctoral dissertation of Shanxi University.

Benson, P. L. (2006). All Kids are our Kids: What Communities Must do to Raise Caring and Responsible Children and Adolescents. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Benson, P. L., Scales, P. C., Hamilton, S. F., and Sesma, A. JR (2007). “Positive youth development: theory, research, and applications,” in Handbook of Child Psychology (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 1. doi: 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0116

Bradley, R. H., and Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53, 371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A. M., Lonczak, H. S., and Hawkins, J. D. (2002). Positive youth development in the United States: research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 591, 98–124. doi: 10.1177/0002716203260102

Chang, S., and Zhang, W. (2013). The developmental assets framework of positive human development: an important approach and field in positive youth development study. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 21, 86–95. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2013.00086

Chen, X., Li, D., Xu, X., Liu, J., Fu, R., Cui, L., et al. (2019). School adjustment of children from rural migrant families in urban China. J. Sch. Psychol. 72, 14–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.12.003

Cheung, N. W. T. (2013). Rural-to-urban migrant adolescents in Guangzhou, China: Psychological health, victimization, and local and trans-local ties. Soc. Sci. Med. 93, 121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.021

Chi, X. L., Hong, X., and Chen, X. C. (2020). Profiles and sociodemographic correlates of Internet addiction in early adolescents in southern China. Addict. Behav. 106:106385. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106385

Chiswick, B. R., Lee, Y. L., and Miller, P. W. (2008). Immigrant selection systems and immigrant health. Contemp. Econ. Policy 26, 555–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7287.2008.00099.x

Cigala, A., Venturelli, E., and Fruggeri, L. (2014). Family functioning in microtransition and socio-emotional competence in preschoolers. Early Child Dev. Care 184, 553–570. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2013.800053

Claire, H., Nancy, E., Spinrad, T. L., Morris, A. S., Gershoff, E., Valiente, C., et al. (2013). Mother–adolescent conflict: stability, change, and relations with externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Soc. Dev. 22, 259–279. doi: 10.1111/sode.12012

Dickstein, S. (2002). Family routines and rituals – The importance of family functioning: comment on the special section. J. Family Psychol. 16, 441–444. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.16.4.441

Eichelsheim, V. I. (2011). The complexity of families assessing family relationships and their association with externalizing problems. Dissertation, Utrecht University, Netherlands.

Fan, X., Fang, X., Liu, Q., and Liu, Y. (2009). A social adaptation comparison of migrant children, left-behind Children, and ordinary children. J. Beijing Normal University 5, 33–40.

Formoso, D., Gonzales, N. A., and Aiken, L. S. (2000). Family conflict and children's internalizing and externalizing behavior: protective factors. Am. J. Community Psychol. 28. doi: 10.1023/A:1005135217449

Fuligni, A. J. (1997). The academic achievement of adolescents from immigrant families: the role of family background, attitudes, and behavior. Child Dev. 68, 351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x

García-Coll, C. E., and Marks, A. K. E. (2012). The Immigrant Paradox in Children and Adolescents: Is Becoming American a Developmental Risk? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Georgiades, K., Boyle, M. H., and Duku, E. (2007). Contextual influences on children's mental health and school performance: the moderating effects of family immigrant status. Child Dev. 78, 1572–1591. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01084.x

Graber, J. A., and Sontag, L. M. (2009). “Internalizing problems during adolescence, in Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society. doi: 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy001020

Greeff, A. P., and Holtzkamp, J. (2007). The prevalence of resilience in migrant families. Fam. Community Health 30, 189–200. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000277762.70031.44

Guberman, C., and Manassis, K. (2011). Symptomatology and family functioning in children and adolescents with comorbid anxiety and depression. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolescent Psychiatry 20, 186–195.

Gui, Y., Berry, J. W., and Zheng, Y. (2012). Migrant worker acculturation in China. Int. J. Intercultural Relations 36, 598–610 doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.11.007

Ha, T., Overbeek, G., Vermulst, A. A., and Engels, R. C. M. E. (2009). Marital quality, parenting, and adolescent internalizing problems: a three-wave longitudinal study. J. Family Psychol. 23, 263–267. doi: 10.1037/a0015204

Hackett, L., Hackett, R., and Taylor, D. C. (1991). Psychological disturbance and its associations in the children of the Gujarati Community. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 32, 851–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb01907.x

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J. Educ. Measurement 51, 335–337. doi: 10.1111/jedm.12050

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. General Psychol. 6, 307–324. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307

Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., and Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 632–643. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.632

Hou, J., Zou, H., and Li, X. (2009). The characteristics of the family environment and its influence on the life satisfaction of migrant children. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2, 78–85.

Hu, N., Deng, L. Y., Zhang, J. T., Fang, X. Y., Chen, L., and Mei, H. Y. (2009). A longitudinal study of the relationship between family functioning and adolescent problematic behaviors. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 25, 93–100.

Jamnik, M. R., and Dilalla, L. F. (2019). Health outcomes associated with internalizing problems in early childhood and adolescence. Front. Psychol. 10:60. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00060

Jankowska, A. M., Lewandowska-Walter, A., Chalupa, A., Jonak, J., Duszynski, R., and Mazurkiewicz, N. (2015). Understanding the relationships between attachment styles, locus of control, school maladaptation, and depression symptoms among students in foster care. School Psychol. Forum 9, 44–58.

Johnson, H. D., Lavoie, J. C., and Mahoney, M. (2001). Interparental conflict and family cohesion: predictors of loneliness, social anxiety, and social avoidance in late adolescence. J. Adolesc. Res. 16, 304–318. doi: 10.1177/0743558401163004

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., and Keltner, D. (2009). Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol, 97, 992. doi: 10.1037/a0016357

Lan, X., and Radin, R. (2020). Direct and interactive effects of peer attachment and grit on mitigating problem behaviors among urban left-behind adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 29, 250–260. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01580-9

Leadbeater, B. J., Kuperminc, G. P., Blatt, S. J., and Hertzog, C. (1999). A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents' internalizing and externalizing problems. Dev. Psychol. 35, 1268–1282. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1268

Lee, M. T. Y., Wong, B. P., Chow, W. Y., and McBride-Chang, C. (2006). Predictors of suicide ideation and depression in hong kong adolescents: perceptions of academic and family climates. Suicide Life Threatening Behav.36, 82–96. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.1.82

Lerner, R. M. (2007). “Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development,” in Handbook of Child Psychology (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.). doi: 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0101

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J., and Theokas, C. (2006). Dynamics of Individual← → Context Relations in Human Development: A Developmental Systems Perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Leung, C. L., Bender, M., and Kwok, S. Y. (2017). A comparison of positive youth development against depression and suicidal ideation in youth from Hong Kong and the Netherlands. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health. 32. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2017-0105

Leung, J. T. Y., and Shek, D. T. L. (2015). Family functioning, filial piety and adolescent psycho-social competence in chinese single-mother families experiencing economic disadvantage: implications for social work. Br. J. Soc. Work 46, 1809–1827. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcv119

Li, X., Zou, H., Wang, R., and Dou, D. (2008). The developmental characteristics of temporary migrant children's self-esteem and its relation to learning behavior and teacher-student relationship in Beijing. Psychol. Sci. 4, 909–913. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2008.04.025

Liu, H., Tian, L., Wang, S., et al. (2011). Adolescents' relationships with mothers and fathers and their effects on depression. J. Psychol. Sci. 6, 1403–1408. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2011.06.012

Lougheed, J. P., and Hollenstein, T. (2012). A limited repertoire of emotion regulation strategies is associated with internalizing problems in adolescence. Rev. Soc. Dev. 21, 704–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00663.x

Ma, X., Yao, Y., and Zhao, X. (2013). Prevalence of behavioral problems and related family functioning among middle school students in an eastern city of China. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 5, E1–E8. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-5872.2012.00211.x

Magnusson, D., and Stattin, H. (1998). “Person-context interaction theories,” in Handbook of Child Psychology Lerner, R. M, ed vol. 1. (5th ed.) (New York, NY: Wiley), 685–759.

Martin, M. J., Conger, R. D., Schofield, T. J., and Family Research Group. (2010). Evaluation of the interactionist model of socioeconomic status and problem behavior: a developmental cascade across generations. Dev. Psychopathol, 22(03):695–713. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000374

Masten, A. S., and Tellegen, A. (2012). Resilience in developmental psychopathology: contributions of the project competence longitudinal study. Dev. Psychopathol. 24, 345–361 doi: 10.1017/S095457941200003X

Miettunen, J., Murray, G. K., Jones, P. B., Mäki, P., Ebeling, H., Taanila, A., et al. (2014). Longitudinal associations between childhood and adulthood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology and adolescent substance use. Psychol. Med. 44, 1727–1738. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002328

Motti-Stefanidi, F., and Masten, A. S. (2013). School success and school engagement of immigrant children and adolescents. Eur. Psychol. 18, 126–135. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000139

Ohtani, T., Nishimura, Y., Takahashi, K., Ikedasugita, R., Okada, N., and Okazaki, Y. (2015). Association between longitudinal changes in prefrontal hemodynamic responses and social adaptation in patients with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 176, 78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.042

Pieters, S., Burk, W. J., Van der Vorst, H., Dahl, R. E., Wiers, R. W., and Engels, R. C. (2015). Prospective relationships between sleep problems and substance use, internalizing and externalizing problems. J. Youth Adolesc. 44, 379–388. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0213-9

Reitz, A. K., Mottistefanidi, F., and Asendorpf, J. B. (2014). Mastering developmental transitions in immigrant adolescents: The longitudinal interplay of family functioning, developmental and acculturative tasks. J. Dev. Psychol. 50, 754–765. doi: 10.1037/a0033889

Reivich, K., Gillham, J. E., Chaplin, T. M., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2013). From Helplessness to Optimism: The Role of Resilience in Treating and Preventing Depression in Youth. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer, 201–214. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_12

Renzaho, A., Mellor, D., McCabe, M., and Powell, M. (2013). Family functioning, parental psychological distress and child behaviours: evidence from the Victorian child health and wellbeing study. Aust. Psychol. 48, 217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00059.x

Rocchino, G. H., Dever, B. V., Telesford, A., and Fletcher, K. (2017). Internalizing and externalizing in adolescence: the roles of academic self-efficacy and gender. Psychol. Sch. 54, 905–917. doi: 10.1002/pits.22045

Roosa, M. W., Dumka, L., and Tein, J. (1996). Family characteristics as mediators of the influence of problem drinking and multiple risk status on child mental health. Am. J. Community Psychol. 24, 607–624. doi: 10.1007/BF02509716

Rosenfield, S., Lennon, M. C., and White, H. R. (2005). The self and mental health: self-salience and the emergence of internalizing and externalizing problems. J. Health Soc. Behav. 46, 323–340. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600402

Russell, T. T., Salazar, G., and Negrete, J. M. (2000). A Mexican American perspective: the relationship between self-esteem and family functioning. TCA J. 28, 86–92. doi: 10.1080/15564223.2000.12034570

Scales, P. C., Benson, P. L., Leffert, N., and Blyth, D. A. (2000). Contribution of developmental assets to the prediction of thriving among adolescents. Appl. Dev. Sci. 4, 27–46. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0401_3

Serap, K., Asgeir, R. O., Thormod, I., and Mari-Anne, S. (2018). The longitudinal association between internalizing symptomms and academic achievement among immigrant and non-immigrant children in Norway. Scand. J. Psychol.?59, 392–406. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12454?

Sheeber, L., Hops, H., Alpert, A., Davis, B., and Andrews, J. (1997). Family Support and Conflict: Prospective Relations to Adolescent Depression. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 25, 333–344. doi: 10.1023/A:1025768504415

Sheeber, L., Hops, H., and Davis, B. (2001). Family processes in adolescent depression. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 4, 19–35. doi: 10.1023/A:1009524626436

Sheidow, A. J., Henry, D. B., Tolan, P. H., and Strachan, M. K. (2013). The role of stress exposure and family functioning in internalizing outcomes of urban families. J. Child Fam. Stud. 23, 1351–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9793-3

Shek, D. T. L. (2002a). Family functioning and psychological well-being, school adjustment, and problem behavior in Chinese adolescents with and without economic disadvantage. J. Genetic Psychol. 163, 497–502. doi: 10.1080/00221320209598698

Shek, D. T. L. (2002b). Assessment of family functioning in chinese adolescents: the chinese version of the family assessment device. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 12, 502–524. doi: 10.1177/1049731502012004003

Shek, D. T. L., Siu, A. M. H., and Lee, T. Y. (2007). The Chinese positive youth development scale: a validation study. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 17, 380–391. doi: 10.1177/1049731506296196

Shek, D. T. L., and Sun, R. C., (eds.). (2013). Development and Evaluation of Positive Adolescent Training through Holistic Social Programs (PATHS) (Vol. 3). Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. doi: 10.1007/978-981-4451-54-3

Shi, L., Chen, W., Bouey, J. H., Lin, Y., and Ling, L. (2019). Impact of acculturation and psychological adjustment on mental health among migrant adolescents in Guangzhou, China: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. BMJ Open 9:e022712. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022712

Stark, K. D., Banneyer, K. N., Wang, L. A., and Arora, P. (2012). Child and adolescent depression in the family. Couple Family Psychol. 1:161. doi: 10.1037/a0029916

Sun, R. C. F., and Shek, D. T. L. (2013). Longitudinal influences of positive youth development and life satisfaction on problem behavior among adolescents in Hong Kong. Soc. Indic. Res. 114, 1171–1197. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0196-4

Wang, M., and Saudino, K. J. (2015). Positive affect: phenotypic and etiologic associations with prosocial behaviors and internalizing problems in toddlers. Front. Psychol. 6:416. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00416

Wang, Z., Jin, G., Lin, X., et al. (2014). The effect of migrant children's resilience on their depression and loneliness. Chinese J. Special Educ. 4, 54–59.

Wang, Z., Li, X., and Fang, X. (2010). A comparative study of migrant children's urban adaptation in public schools and schools for migrant workers' children. Chin. J. Special Educ. 12, 21–26.

Weng, L. C., Huang, H. L., Lee, W. C., Tsai, Y. H., Wang, W. S., and Chen, K. H. (2019). Health-related quality of life of living liver donors1year after donation. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 8, 1–9. doi: 10.21037/hbsn.2018.11.10

Wingo, A. P., Wrenn, G., Pelletier, T., Gutman, A. R., Bradley, B., and Ressler, K. J. (2010). Moderating effects of resilience on depression in individuals with a history of childhood abuse or trauma exposure. J. Affect. Disord. 126, 411–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.009

Wissink, I. B., Dekovic, M., and Meijer, A. M. (2006). Parenting behaviour, quality of the parent–adolescent relationship, and adolescent functioning in four ethnic groups. J. Early Adolescence 26, 133–159. doi: 10.1177/0272431605285718

Wu, Q., Tsang, B., and Ming, H. (2014). Social capital, family support, resilience and educational outcomes of chinese migrant children. Br. J. Soc. Work 44, 636–656. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcs139

Xiong, H. X., Zhang, J., Ye, B. J., Zheng, X., and Sun, P.-Z. (2012). Common method variance effects and the models of statistical approaches for controlling it. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 20, 757–769. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2012.00757

Xiong, J., Qin, Y., Gao, M., and Hai, M. (2017). Longitudinal study of a dual-factor model of mental health in Chinese youth. Sch. Psychol. Int. 38, 287–303. doi: 10.1177/0143034317689970

Ye, Z., Chen, L., Harrison, S. E., Guo, H., Li, X., and Lin, D. (2016). Peer victimization and depressive symptoms among rural-to-urban migrant children in China: the protective role of resilience. Front. Psychol. 7:1542. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01542

Yee, N. Y., and Sulaiman, W. S. W. (2017). Resilience as mediator in the relationship between family functioning and depression among adolescents from single parent families. Akademika 87. doi: 10.17576/akad-2017-8701-08

Yu, M., Xu, Q., Zhu, Y., Xu, W., Zhou, N., and Wang, J. (2017). The current status and predictive factors of Internalizing and externalizing symptoms among Chinese adolescents. China J. Health Psychol. 25, 1733–1738. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2017.11.035

Yuan, L. (2011). Comparison of discrimination status of migrant children in public schools and migrant schools. Chinese J. School Health 32, 856–857. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2011.07.043

Keywords: internalizing problems, family functioning, positive youth development, migrant children, Chinese adolescents

Citation: Wang Q, Peng S and Chi X (2021) The Relationship Between Family Functioning and Internalizing Problems in Chinese Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 12:644222. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644222

Received: 20 December 2020; Accepted: 09 February 2021;

Published: 24 March 2021.

Edited by:

Nora Wiium, University of Bergen, NorwayReviewed by:

Xiaoyu Lan, University of Padua, ItalyHatta Sidi, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Yekoyealem Kebede, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2021 Wang, Peng and Chi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinli Chi, eGlubGljaGlAMTI2LmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Qiuying Wang1†

Qiuying Wang1† Xinli Chi

Xinli Chi