- 1Department of Human Resource Management, School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China

- 2Center for Human Resource Development and Assessment, School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China

In this study, we investigate the coping response of individuals who are being gossiped about. Drawing on face research and affective events theory, we propose that employees who are targets of negative gossip will actively respond to the gossip about them via engagement in negative gossip themselves. The findings showed that negative workplace gossip stimulated fear of losing face and led to subsequent behavioral responses, namely, engaging in negative gossip. Moreover, self-monitoring, as a moderating mechanism, mitigated the negative impacts of negative workplace gossip on the targets. We discuss theoretical implications for gossip research and note its important practical implications.

Introduction

For most people in an organization, it is inevitable to become the target of negative gossip. Negative gossip refers to informal communications with other members (i.e., the receiver) about a negative behavior or characteristics of a third party who is absent at work (Brady et al., 2017). A growing number of studies have suggested that negative gossip can have a detrimental effect on the targets. For example, recent empirical studies have shown that negative gossip can have destructive effects on emotional well-being, e.g., emotional exhaustion (Wu X. et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020), other-directed emotional responses (e.g., Martinescu et al., 2019a,b), cognitions [organization-based self-esteem (e.g., Wu L. Z. et al., 2018)], behaviors [proactive behavior (e.g., Wu X. et al., 2018; Martinescu et al., 2021)], and creative behavior (e.g., Liu et al., 2020) of targeted individuals. Clearly, how these targets deal with negative gossip about them is a subject worth addressing. However, although previous studies have demonstrated the behavioral consequences of being the targets of gossip (e.g., Feinberg et al., 2014; Wu L. Z. et al., 2018; Martinescu et al., 2019a; Dores Cruz et al., 2020), very little attention has been paid to the counterattack of the targets in order to reduce the detrimental effects of negative gossip within organizations.

To fill this gap, this study combines face research with affective events theory (AET, Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996) in an attempt to reveal the emotional consequences of negative gossip in the workplace and corresponding behavioral responses. “Face” refers to “an image of self, delineated in terms of approved social attributes” (Goffman, 1967, p. 5). To a large extent, face, on which people depend to survive in their positions, is built on a variety of foundations, such as reputation, competence, and performance. Therefore, people are generally worried about losing face in the workplace (Brown, 1970). Based on this, this study links negative workplace gossip with face and resulting behavioral responses for the following reasons: first, negative workplace gossip contains information that denigrates the performance and ability in the role of the targets, which could exacerbate their fear of losing face (Gluckman, 1963; Grosser et al., 2010). Second, face research has shown that people worry about their external images related to their positions if threatened, and that these face concerns can prompt them to engage in face-saving behaviors (Goffman, 1955; Harrison et al., 2018; Martinescu et al., 2019a,b). As a result, we suggest that negative gossip may cause the targets to feel fear of losing face and react accordingly.

In short, by combining face research with AET (Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996), we propose a new theoretical framework to understand the emotional impacts of negative gossip in the workplace on targets and their subsequent behavioral responses. Specifically, we identify fear of losing face as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between negative workplace gossip and engaging in negative gossip. We suggest that negative gossip can arouse fear of losing face in the targets (Zhang et al., 2011), and then trigger the targets to participate in negative gossip to ease their worries. According to AET, personality traits can influence the process of emotional response (Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996). Additionally, some studies have shown that individuals respond differently to face their threats, because personality characteristics play an important role in this process (Ho, 1976). Self-monitoring as a trait may play this role, that is, it may affect how the targets react to the gossip about them. Self-monitoring is defined as the extent to which individuals are willing and able to control their public expression and shape their public appearances under the guidance of social appropriateness (Snyder, 1979). Thus, given the importance of self-monitoring in making sense of and dealing with information related to humiliation or embarrassment and external image (Turnley and Bolino, 2001), we identify it as a construct that refers to the extent to which individuals are willing and able to control their public expression and shape their public images (Snyder, 1979). We predict that self-monitoring moderates the relationship between negative workplace gossip and fear of losing face.

This study aims to make several theoretical contributions to the literature. First, our study extends the previous research on negative workplace gossip by addressing how the targets deal with negative gossip, and by introducing a novel face-based mechanism in this process, namely, fear of losing face, as a focal mediating mechanism, which is explicated in detail. Second, we contribute to the workplace gossip literature by integrating it with face research for the first time. Although scholars studying gossip often explicitly or implicitly mention its impact on external images (Wu et al., 2016; Tassiello et al., 2018), empirical research is still scarce. In this regard, we introduce a specific concept related to face, fear of losing face, and theorize and empirically test the connection between the two concepts. Finally, we introduce a moderating mechanism for workplace gossip, namely, self-monitoring.

Theory and Hypothesis Development

Negative Workplace Gossip and Engaging in Negative Gossip

Gossip is ubiquitous in organizations. Recently, it has been defined as “a sender communicating to a receiver about a target who is absent or unaware of the content” (Dores Cruz et al., 2021). Typical gossip can either be positive or negative (Brady et al., 2017). Compared with positive gossip, within an organization, negative gossip is generally considered to have a greater impact on the targets (Wert and Salovey, 2004). After all, “good news travels slowly and bad news has wings.” In the workplace, negative gossip can provide performance-related information, such as poor performance and/or disapproval of the behavior of the targets, which is highly detrimental to the reputation of the targets, as reputation is necessary for their career advancement and development in the organization (Bell, 2003). In addition, negative gossip can be used as a tool to reshape organizational norms. For example, through negative gossip, gossipers could emphasize to the audience the legitimacy of their own norms and make them widely accepted in the group, which helps maintain their images in the position (Foster, 2004; Shaw et al., 2011).

Negative gossip, an evaluative conversation that communicates reputation information, makes the target aware of murmurs about his/her position, criticism of his/her abilities, and even potential damage to his/her external image (Brady et al., 2017), which can be regarded as an affective event (Wu X. et al., 2018). We posit that engaging in negative gossip may be the response of the targets to the negative gossip about them. Gossip has multiple social functions. First, gossiping, as a means of emotional venting and coping, can help relieve the anxiety and stress generated by affective events (Brady et al., 2017; Dores Cruz et al., 2019a). Second, gossiping can be used as a tool for information collection to make sense of the real and actual situations in order to gain insight into the norms of the group. This can help the target reduce the uncertainty created by negative gossip events and take appropriate actions, such as justifying themselves (Eder and Enke, 1991; Beersma and Van Kleef, 2012; Brady et al., 2017). Finally, gossiping is a tool for reshaping organizational norm, allowing gossipers to enforce their own norms, thereby strengthening the legitimacy of their positions and maintaining a positive image of themselves (Noon and Delbridge, 1993; Shank et al., 2019). Also, other studies support the reasoning. For example, research on aggression has suggested that indirect forms of aggression, such as gossiping, are more likely to be used by people than direct forms when manipulating reputation. This is because direct aggression is more obvious and easier to be detected by the targets than an indirect one. That is, it is easy to expose identity or hostile intentions, making perpetrators of direct aggression more likely to be confronted with retaliation from the targets than the perpetrators of indirect aggression (Archer and Coyne, 2005). Studies on negative reciprocity have also shown that the targets will take action against the perpetrators, referred to as “an eye for an eye” (Andersson and Pearson, 1999; Greco et al., 2019). Thus, we suggest that the targets of gossip themselves have a tendency to engage in negative gossip in response to being targeted by gossipers.

Therefore, we propose the following:

H1. Negative workplace gossip is positively related to engaging in negative gossip of the targets.

Negative Workplace Gossip and Fear of Losing Face

Face refers to “an image of self, delineated in terms of approved social attributes” (Goffman, 1967, p. 5). In social interactions, actors can gain face by acting in accordance with the norms of their roles (Kim and Nam, 1998; Tuncel et al., 2020). Actors lose face when they deviate from socially acceptable norms, fail to live up to the expectations of their audience, fail to fully perform their position, and/or are not liked by others (Miron-Spektor et al., 2015; Bourgoin and Harvey, 2018). Actors use face-work, a variety of verbal and non-verbal tactics, to convey the information that improves their face and resist face-threatening events (Ho, 1976; Bourgoin and Harvey, 2018). It is worth noting that face is different from status (Ho, 1976). Status refers to the relative position of a person within a group, for example, which can be obtained through association with other prominent figures (Benjamin and Podolny, 1999), whereas face refers to performing well in social roles. Thus, face is a more inclusive and extensive concept that can be built on and derived from status or other relevant concepts (Ho, 1976). Although the term “face” originally came from China, the central tenet of face is universal (Ho, 1976). Indeed, in social encounters, it is universal to pursue a good reputation and/or a positive self image in the eyes of others (Ho, 1976; Cupach and Metts, 1994). Several studies have shown that face also exists in Western culture (e.g., Mak et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012; Miron-Spektor et al., 2015).

Fear of losing face reflects the concern of an individual with a disapproving image and/or negative evaluations, in terms of their performance in their position (Zhang et al., 2011). In the workplace, face has positive external benefits, such as supervisor performance ratings (Wayne and Ferris, 1990; Huang et al., 2013), pay increase (Bartol and Martin, 1990), and promotions (Liu et al., 2020), and it is also a part of the identity of someone (Harrison et al., 2018). Therefore, these inform us that we should avoid losing face in specific positions.

The AET clarifies that workplace events can trigger the emotional responses of individuals (Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996). Negative workplace gossip, a negative, evaluative talk that involves important information about the poor performance and/or disapproved behaviors of the target in the position, can leave the target worried about damaging his/her reputation and external image in the position, that is, fear of losing face. Therefore, people in the workplace believe that negative gossip about them means that they are already performing poorly in their position, which leads to a negative external image in the eyes of others and ultimately aggravates the fear of losing face. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2. Negative workplace gossip is positively related to fear of losing face.

Fear of Losing Face and Engaging in Negative Gossip

Fear of losing face can trigger behavioral responses in individuals to avoid disapproval or negative evaluation (Zhang et al., 2011). Many previous studies on gossip provide a functional account for gossiping in organizations. Engagement in negative gossip can be a good way for gossipers to preserve their own image through reinforcing the norms (e.g., McAndrew et al., 2007; Watson, 2011; Beersma and Van Kleef, 2012; Brady et al., 2017; Hess and Hagen, 2019; Archer and Coyne 2005). In this regard, we posit that gossiping may be an effective way to deal with the fear of losing face. Specifically, gossiping, as a norm-setting behavior, can help to shift the norms in line with the interests of the gossipers and re-establish their competence in the positions they occupy (Brislin, 1980; Baumeister et al., 2004), which helps them meet or even exceed the expectations in the eyes of others, create good external images, and thus alleviate the fear of losing face (Ho, 1976; Zane and Yeh, 2002). Also, gossiping can be a means of emotional venting and coping. Prior research, for example, has suggested that gossiping may help relieve the negative emotions of the gossipers (Brislin, 1980; Brady et al., 2017; Dores Cruz et al., 2019a). Taken together, we believe that people who fear of losing face may be motivated to engage in negative gossiping to address face concerns. Therefore, we propose the following:

H3. Fear of losing face is positively related to engaging in negative gossip.

H4. Fear of losing face mediates the positive indirect relationship between negative workplace gossip and engagement in negative gossip of the target.

The Moderating Effect of Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring is defined as the extent to which individuals are willing and able to control their public expression and shape their public appearances under the guidance of social appropriateness (Snyder, 1979). High self-monitors, according to social appropriateness, are more willing and proficient in modifying their social images in line with the situational demands and role expectations of others; whereas low self-monitors express behaviors that are less controlled by deliberate attempts to behave in situation-appropriate ways (Snyder, 1979; Kudret et al., 2019). Specifically, similar to social chameleons, high self-monitors have almost all of the requisites and sufficient skills to successfully mold and tailor their self-presentation in line with situational appropriateness (Snyder, 1979; Snyder and Gangestad, 1982, 1986). A series of studies have shown that high self-monitors are attentive to information related to their external images and that, at the same time, they have great skills in controlling the images they present to others (e.g., Turnley and Bolino, 2001; Smart Richman and Leary, 2009; Bolino et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2021). Although high self-monitors are more likely to pay attention to the reputation information around them, they are quite skilled and confident in the management of their own reputation. For example, Harrison et al. (1996) demonstrated that people with a high level of self-monitoring showed higher self-efficacy and better adaptability in their interpersonal communication. In addition, research on social networks has shown that high self-monitors have more instrumental and friendship ties. The former can help to effectively obtain important work information to ease uncertainty, and the latter can help individuals to form friendships to ease emotions (Garland and Beard, 1979; Oh and Kilduff, 2008; Borgatti and Halgin, 2011; Kilduff and Lee, 2020). Therefore, these findings indicate that high self-monitors may be better at dealing with negative gossip and avoiding being perceived as less competent or desirable in their positions, which is to say they are not afraid of losing face.

Therefore, based on the AET, which points out that personality traits influence the process of workplace events that affect emotional responses and subsequent behaviors (Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996), we propose that people who are high self-monitors are less likely to consider negative gossip as a worrying face-threatening event because they are always aware of and alert to negative information around them and they have the confidence to deal with it. Hence, a high level of self-monitoring reduces the damaging impact of negative workplace gossip on the target, thus relieving the fear of losing face. However, when the targets of negative gossip have a low level of self-monitoring, it is more likely that negative gossip further aggravates their bad reputation, because they lack adequate preparation and suppression skills (Turnley and Bolino, 2001), thus increasing the fear of losing face. As a result,

H5. Self-monitoring moderates the relationship between negative workplace gossip and fear of losing face. The relationship is less positive when targeted employees have a high level of self-monitoring.

H6. Self-monitoring moderates the mediating effect of fear of losing face on the relationship between negative workplace gossip and engagement in negative gossip of the targets, such that the mediating effect is stronger for the targets with low levels of self-monitoring than for those with high levels of self-monitoring.

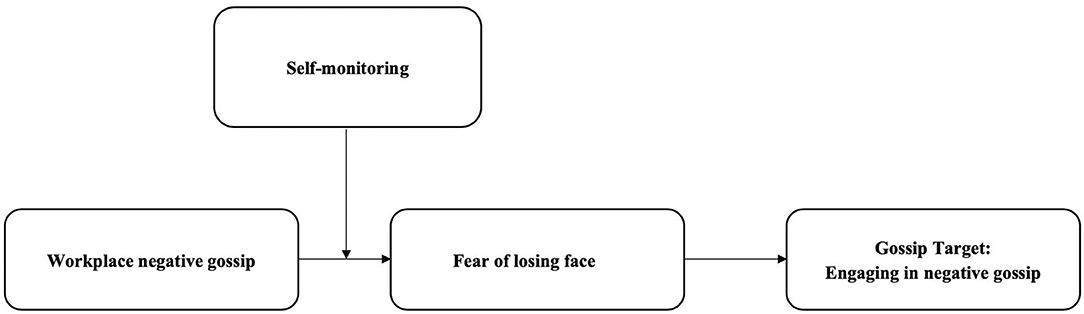

Figure 1 depicts our theoretical framework.

Figure 1. Theoretical model of the current research. Note: Negative workplace gossip and self-monitoring were both measured at time point 1, fear of losing face was measured at time point 2, and engaging in negative gossip was measured at time point 3.

Methods

Data and Sample

The participants were recruited from a large entertainment company located in Beijing, China. At time 1 of data collection, we first assured the participants of confidentiality and voluntary participation, and then distributed the questionnaires to a total of 600 participants from the company. Among them, 498 participants (82.67%) returned the questionnaires. We surveyed all the participants at time 1 again a month later (time 2), and 420 valid questionnaires from the 498 participants were returned, representing a response rate of 84.33%. Finally, another month later (time 3), we surveyed the participants who responded at time 2, yielding the final sample of 326 participants (77.6%).

Among the participants, 144 (44.17%) were female, and their average organizational tenure was 4.97 years (sd = 4.36). On average, the participants were 32.95 years of age (sd = 7.79). The majority of the respondents (52.1%) had a bachelor's degree. In terms of potential non-response bias, the response analyses revealed that the individuals in the final sample of 326 employees were not significantly different from those who were dropped from the analyses in terms of demographics and negative workplace gossip measured at T1. We followed the procedures strictly to translate the English-based measures into Chinese (Brislin, 1980). All the surveys conducted for the three time points were in Chinese.

Measures

We tested the theoretical model across three time points. Specifically, demographic information, engaging in negative gossip, and workplace negative gossip were measured at time 1. A month later (time 2), the participants reported their self-monitoring and fear of losing face. Another month later (time 3), the participants rated their engagement in negative gossip again. Considering the difference between the definition of gossip of a layperson and the theoretical one, we introduced the definition of workplace gossip to the subjects before they filled in the questionnaire in order to avoid misunderstanding of the concept. In particular, we emphasized therein the two basic characteristics of gossip: involving, namely, three parties and the absence of the targets.

Negative Workplace Gossip (T1)

This measured being the target of gossip. A five-item scale developed by Brady et al. (2017) was used to measure negative workplace gossip. The items were rated on a seven-point response scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (more than once a day), and were preceded by a stem referring to “in the last month, how often have colleagues.” The example items were, “asked a work colleague if they have a negative impression of something that I have done” and “questioned my abilities while talking to another work colleague” (α = 0.96).

Fear of Losing Face (T2)

A month later, the participants rated fear of losing face with a five-item scale developed by Zhang et al. (2011). The response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The example items include: “for the past month, I have always avoided talking about my weakness,” “for the past month, it was hard for me to acknowledge a mistake, even if I was really wrong,” and “for the past month, I have done my best to hide my weakness before others” (α = 0.87).

Self-Monitoring (T2)

We measured self-monitoring of the participants with an 18-item scale developed by Snyder and Gangestad (1986). The items were evaluated on a five-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The example items were, “I guess I put on a show to impress or entertain others,” “In different situations and with different people, I often act like very different persons” (α = 0.88).

Engaging in Negative Gossip (T3)

This measures the gossip targets themselves engaging in negative gossip. The participants reported their own engagement in negative gossip with a five-item scale developed by Brady et al. (2017). The response options ranged from 1 (never) to 7 (more than once a day). The example items were as follows: “how often have you asked a work colleague if they have a negative impression of something that another co-worker has done,” and “how often have you questioned a co-worker's abilities while talking to another work colleague” (α = 0.93).

Control Variables

Consistent with the previous research on gossip, we controlled for gender, age, education, and organizational tenure of the participants, because these factors are related to engaging in gossip. We controlled for gender, because men and women differ in gossip frequency, content, and attitudes (Davis et al., 2018). We also controlled for age, education, and organizational tenure because these factors affect the gossip behaviors of individuals (Kim et al., 2019). In addition, it is worth noting that we measured engaging in negative gossip both at T1 and T3, mainly to control the influence of engaging in negative gossip at T1 on engaging in negative gossip at T3. This is because there may be an upward spiral, as previously noted in the mistreatment literature (e.g., Greco et al., 2019), namely, an abuser is more likely to be retaliated against by others and then engage in more abusive behavior. Therefore, we controlled engaging in negative gossip at T1 in our model.

Results

Analytic Strategy

We first conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with Mplus 7.0 (Muthen and Muthen, 2012). We then used the SPSS 22.0 software to test the direct effects, and selected Model 7 for PROCESS plug-in to test our moderated mediating model in order to estimate the model and to obtain bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (using 2,000 bootstrap samples) (Hayes, 2017).

Descriptive Statistics

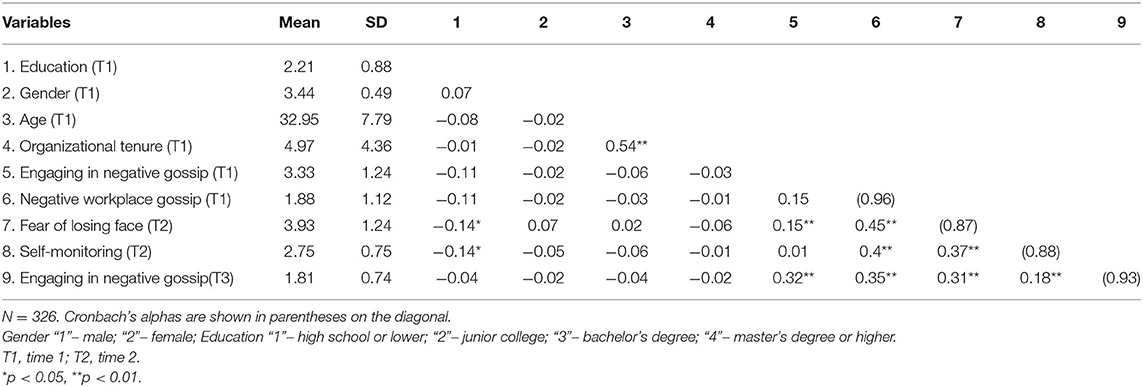

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlations of all key variables.

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

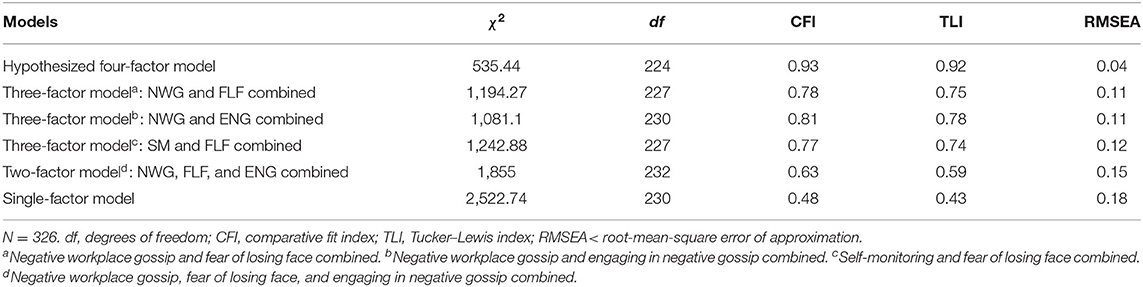

Prior to confirmatory factor analyses, we first performed a Harman's single-factor test considering that all the variables in this study, i.e., negative workplace gossip, fear of losing face, self-monitoring, and engaging in negative gossip, were collected from the same source (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). The result showed that only a factor emerged with only 29.1% of the variance, indicating that the problem of common method bias may be avoided in the current study. Then, we conducted a set of CFAs to further ensure the satisfactory discriminant validity of negative workplace gossip, fear of losing face, self-monitoring, and engaging in negative gossip. The results suggested that the hypothesized four-factor model (χ2 = 535.44, df = 224, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.04) yielded better fit than any other alternative models (see Table 2).

Tests of Hypotheses

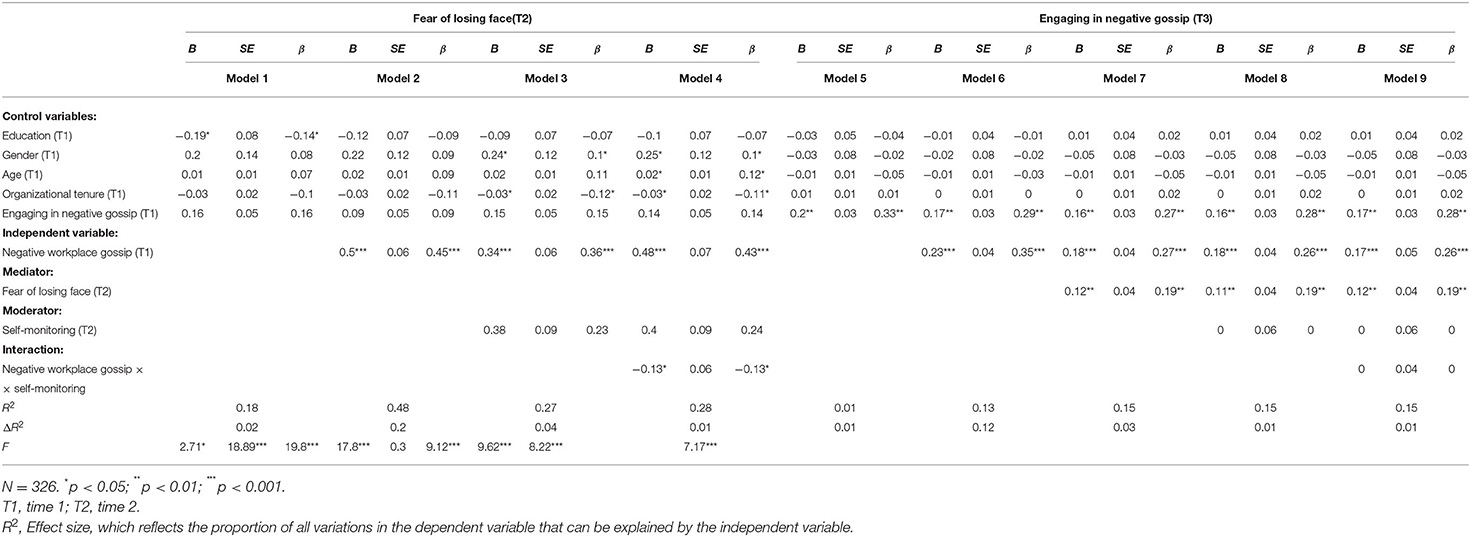

We first conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis to test the hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 predicted that negative workplace gossip is positively related to engaging in negative gossip of targets. As shown by Model 6 in Table 3, negative workplace gossip was positively and significantly related to engaging in negative gossip (β = 0.35, p = 0, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that negative workplace gossip is positively related to fear of losing face. As shown by Model 2 in Table 3, negative workplace gossip was positively related to fear of losing face (β = 0.45, p = 0.001, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 2.

As indicated by Model 7 in Table 3, fear of losing face was positively related to engaging in negative gossip (β = 0.19, p = 0.001, p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

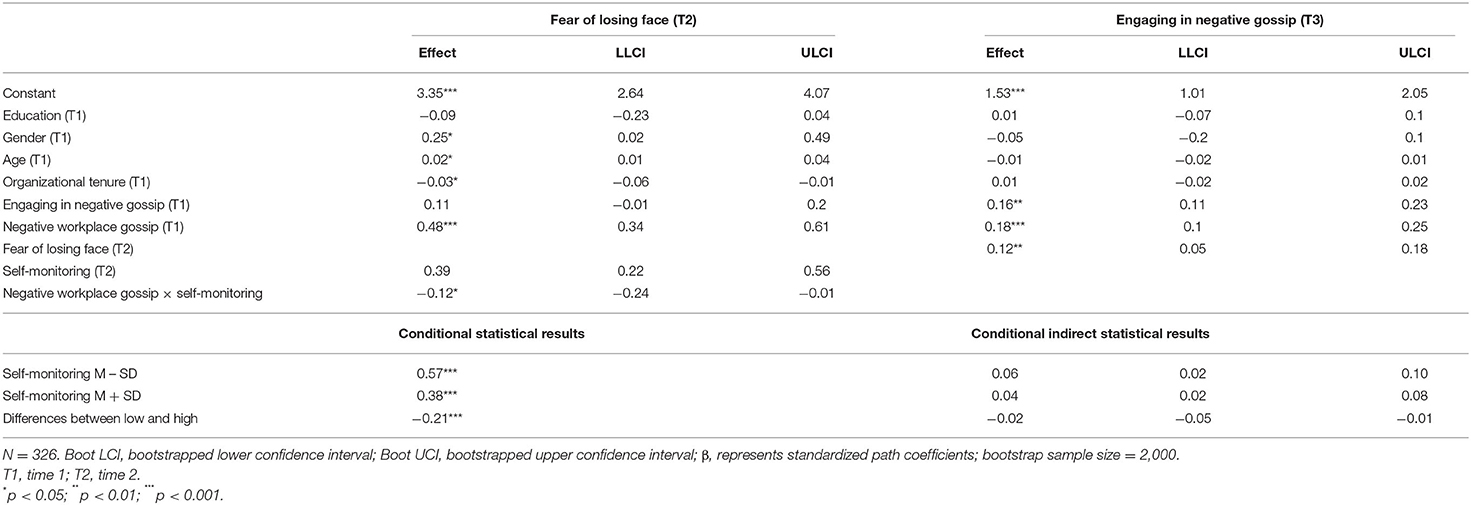

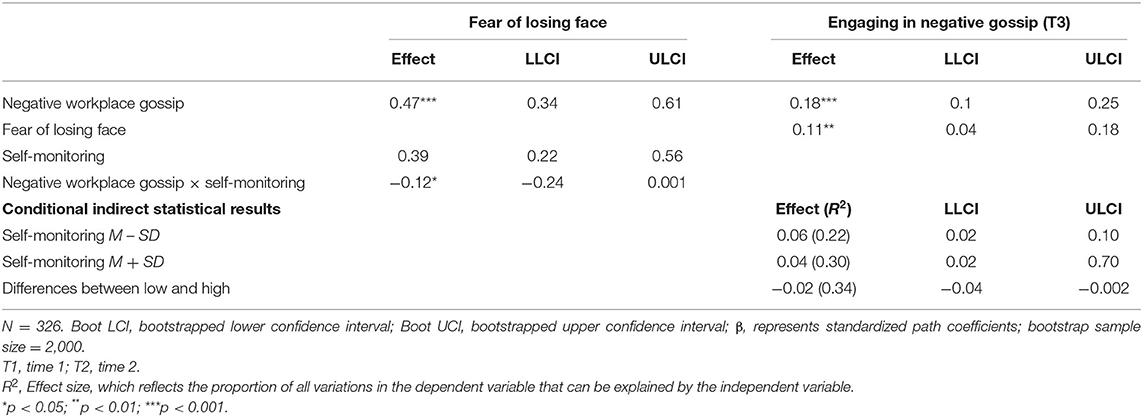

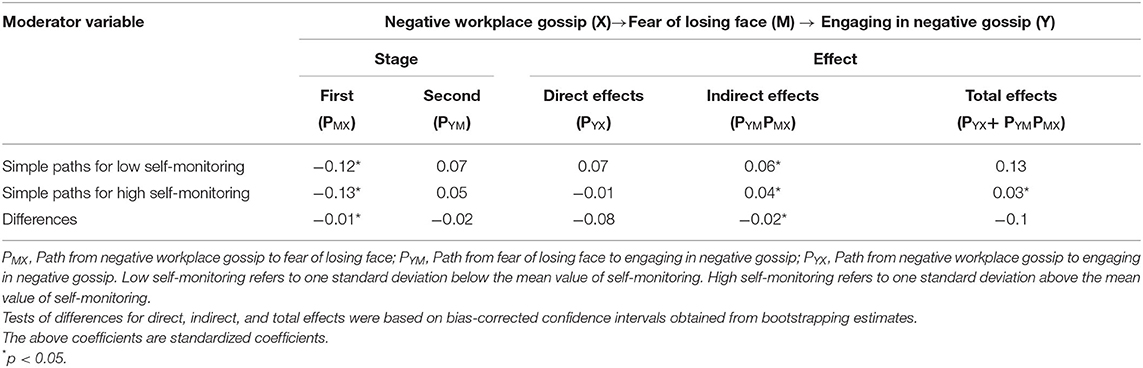

Then, for generating bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs), we employed the PROCESS analysis and opted for Model 7 to test our mediating and moderated mediating effects (Hayes, 2017). Hypothesis 4 predicted that fear of losing face mediates the relationship between negative workplace gossip and engaging in negative gossip. As shown in Table 4, negative workplace gossip was positively related to fear of losing face (β = 0.48, p = 0.0001, p < 0.001, bias-corrected bootstrap 95% CI = [0.34, 0.61], and fear of losing face was positively related to engaging in negative gossip (β = 0.12, p = 0.001, p < 0.01, bias-corrected bootstrap 95% CI = [0.05, 0.18]). Additionally, the PROCESS analysis results showed that there was a significant mediation effect through fear of losing face in the relationship between negative workplace gossip and engaging in negative gossip (β = 0.05, bias-corrected bootstrap 95% CI = [0.02, 0.09]). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported (also see Table 5 for the regression results without control variables and Table 6 for supplementary results of the moderated path analysis).

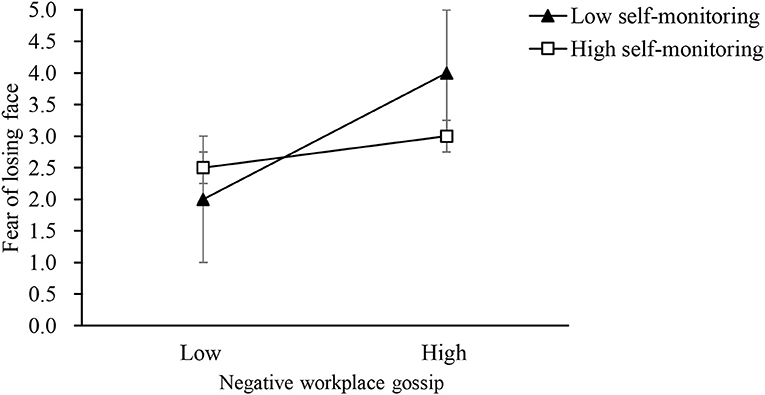

Regarding the moderating effects in this study, Hypothesis 5 predicted that self-monitoring moderates the relationship between negative workplace gossip and fear of losing face. As shown by Model 4 in Table 3, the interaction between negative workplace gossip and self-monitoring was negatively related to fear of losing face (β = −0.12, SE = 0.06, p = 0.036, p < 0.05). Using the procedure of Aiken et al. (1991), we plotted the relationship between negative workplace gossip and fear of losing face according to two levels of self-monitoring, namely, one standard deviation above the mean and one standard deviation below the mean. Figure 2 shows that the positive effect between negative workplace gossip and fear of losing face was stronger when self-monitoring was low (simple slope = 0.57, SE = 0.1, p < 0.001) rather than high (simple slope = 0.38, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 5.

Figure 2. The moderating role of self-monitoring on the relationship between negative workplace gossip and fear of losing face. Note: High and low levels represent 1 SD above and below the mean, respectively. The error bars are represented around the points.

Finally, the results presented in Table 4 provided empirical support for Hypothesis 6. The results showed that self-monitoring moderated the mediating effect of fear of losing face on the relationship between negative workplace gossip and engaging in negative gossip of the targets, such that the mediating effect was stronger for targets with low levels of self-monitoring than for those with high levels of self-monitoring. Specifically, the mediated relationship between negative workplace gossip and engaging in negative gossip through fear of losing face was stronger when self-monitoring was low (i.e., conditional mediation effect = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.11]) vs. high (i.e., conditional mediation effect = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.08]). The difference between the two conditions was −0.02 with 95% CI [−0.05, −0.001]. Thus, we obtained support for Hypothesis 6.

Discussion

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Based on face research and AET, this study developed theoretical arguments and empirically tested the relationships between being the target of negative gossip and engaging in negative gossip behavior of the targets, and further explored the role of face as a mediating mechanism in this process, namely, fear of losing face. This study also examined a contingent effect, namely, self-monitoring, which mitigated the positive relationship between negative workplace gossip and fear of losing face. The results supported the hypotheses. In the following, we discuss how our findings contribute to the existing literature and managerial practices.

This study contributes to prior studies by investigating how targets respond to negative workplace gossip from the perspective of face. As such, we introduced a novel mediating mechanism to the gossip literature, fear of losing face. The findings showed that negative workplace gossip, as an affective event, could enhance fear of losing face and thereby trigger engaging in negative gossip of the targets. This study makes three contributions to the study on negative gossip. First, we add to the research on target responses to gossip. There have been some negative gossip studies that investigated the behavioral responses of the targets after hearing gossip about them. In particular, these studies have focused either on passive responses of the targets, such as a reduction in extra performance or discretionary behavior (Wu X. et al., 2018) and even turnover intentions (Brady et al., 2017), or on adaptive responses, such as cooperation behavior that arises from the concern for reputation or the need to integrate into a group (e.g., Feinberg et al., 2014; Dores Cruz et al., 2019b, 2020). However, relatively less attention has been paid to the active responses of the targets, such as gossiping. We do acknowledge that gossip research has already theorized that the targets of gossip may have a tendency to cope actively. However, in fact, few empirical studies have specified which specific detrimental behavior that the targets may engage in against the perpetrators, let alone studies that have directly examined the relationship between the two. In this study, we empirically found that the gossip targets themselves would also participate in gossip, acting as gossip senders, and theoretically explicated the process by which the gossip targets became gossip senders themselves. In this regard, we extend past studies on the responses of gossip targets. In addition, in terms of the positive aspects of gossip, scholars have pointed out that sharing of negative gossip about a target can have a pro-social motive and be used as a means for effectively deterring selfishness and promoting cooperation of the target, such as protecting others from antisocial or exploitative behavior (e.g., Feinberg et al., 2012, 2014; Milinski, 2016; Dores Cruz et al., 2019a, 2020). However, the results indicated that the targets of negative gossip were indeed likely to deal with the gossipers actively rather than merely respond in a cooperative or adaptive manner. On this basis, we encourage future research to explore the conditions under which gossip targets are more likely to respond in a passive, adaptive, or active way, or in combination of all three.

Second, we provide a faced-based mediating mechanism for workplace gossip research. Specifically, we identified fear of losing face as a mediating mechanism between negative workplace gossip and engaging in negative gossip. Past research has provided some important theoretical perspectives on the effects of gossip on targets, such as social exchange theory (Lee et al., 2016), emotion-related theory (Wu X. et al., 2018), social identity theory (Ye et al., 2019), and conservation of resource theory (Cheng et al., 2020), all of which significantly advance the research on gossip. These perspectives effectively reveal the negative effects of workplace gossip on emotions, cognitions, and behaviors of the targets. For example, negative gossip leads to emotional exhaustion and negative mood (Wu X. et al., 2018; Babalola et al., 2019), increases ego depletion and organization-based self-esteem (Wu L. Z. et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2020), and reduces organizational citizenship behavior, innovative behavior, and other extra-role behaviors (Wu L. Z. et al., 2018; Wu X. et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2019). In contrast, based on a face-based perspective, this study focused more on how these gossip targets dealt with the perpetrators in an active manner, e.g., gossiping behavior, to regain their face. Negative gossip can be insidious and undetectable, and differs from mistreatments such as abuse, workplace bullying, workplace ostracism, and physical aggression (Duffy et al., 2002). Given that face is related to the assessment of abilities of someone in a position, people may be more likely to take relatively covert and safe actions than take a risk with offensive actions, which would do more damage to the face of someone. Further, there is a subtle difference between face and reputation, although the latter also suggests that the targets of gossip may engage in reputation-seeking behavior because of reputation concerns, such as cooperative and organizational citizenship behavior (e.g., Piazza and Bering, 2008; Beersma and Van Kleef, 2011; Wu L. Z. et al., 2018). By definition, face represents the self-worth of a person gained by performing specific social roles that are well-recognized by others (Ho, 1976), whereas reputation reflects the observable qualities or attributes of a person (e.g., gender, age education, institution granting degrees, experience) (Spence, 1974; Ferris et al., 1994). This means that people who perform well in their position, even if they have a bad reputation, will gain face. In this regard, face may be more directly associated with workplace gossip, since workplace gossip mainly involves the evaluation of work-related aspects, while reputation is more multisource and characterized primarily by personal qualities. Thus, compared with reputation theoretically elaborated in previous studies, this study considers fear of losing face as the mediating mechanism of gossip to provide more detailed understanding of how gossip in organizations affects the response of the target.

Finally, the moderating effect of self-monitoring showed that it is a boundary mechanism for how targets react to workplace gossip. Specifically, our findings showed that high self-monitors not only relieved the detrimental effect of negative workplace gossip on them, they also reduced their own gossiping. Therefore, this result, on one hand, verifies the view of previous scholars that self-monitoring, as a personality trait, could be used to effectively deal with workplace gossip (e.g., Xie et al., 2019); on the other, it also provides us with insights, that is, it may be able to restrain the targets from engaging in negative gossip. Existing studies on the boundary mechanisms of gossip have generally focused on the following aspects: situational characteristics, e.g., organizational change, uncertainty, and ambiguity (Mills, 2010); job social support (Tian et al., 2019); work-unit cohesiveness (Loughry and Tosi, 2008); civility climates (Li et al., 2019), gossip characteristics, e.g., gossip veracity (Dores Cruz et al., 2019a); statue of target (Ellwardt et al., 2012); relationships in gossip triad; content of gossip (Tassiello et al., 2018; Giardini and Wittek, 2019), cognitions, e.g., traditionality (Wu X. et al., 2018); just world beliefs (Zhou et al., 2020); reputational concerns (Martinescu et al., 2019a,b); creative self-efficacy (Zhou et al., 2019); trustworthiness (Lee and Barnes, 2020); perceived insider status (Kim et al., 2019), and emotions, e.g., negative affectivity (Wu L. Z. et al., 2018), all of which have made outstanding contributions to the boundary mechanisms of gossip. However, at the same time, we notice that the research on personality traits is still insufficient. In fact, personality traits may have a great potential to play a role in the influence process of gossip. For example, the dark triad (i.e., psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism) is characterized by callousness and a tendency to manipulate others for own benefit (Jones and Figueredo, 2013). It may be more resistant to gossip about themselves, and thus may provide valuable insights for gossip research. To address this gap, we encourage future research to introduce more relevant personality traits and explore their roles in gossiping.

This study has two important practical implications. First, it shows that the targets of negative gossip engaged in negative gossip for fear of losing face. The findings remind managers to pay special attention to employee face issues. Personal face is related to the competence and reputation of someone in a position, which is related to the personal status of an employee in a group and future career development; thus, employees often attach great importance to it. It is a prevalent yet easily overlooked phenomenon in organizational management. Indeed, we rarely see provisions on face in official documents or daily regulations of organizations. However, the findings of this study show that employees who were concerned about losing face would respond to the perpetrators to seek revenge, eventually having a negative impact on individuals and organizations. Therefore, we believe that managers should pay more attention to the face needs of employees. For example, employees who have performed well in their position should be praised publicly and ceremonially. In addition, we also suggest that organizations should establish effective formal feedback channels or communication mechanisms, rather than rely solely on the own gossip networks of employees, in order to help employees communicate with each other about work-related information and provide emotional counseling. Second, our conclusions indicate that self-monitoring might be a personality trait that effectively responds to negative gossip, and that it might also be able to inhibit the subsequent gossip behavior of someone. This conclusion especially reminds us to pay more attention to people with low self-monitoring in the workplace, because they may be more likely to suffer from the negative effects of negative workplace gossip. In this regard, we suggest that managers could provide employees with a variety of training programs on interpersonal communication, conflict, and psychological construction while allowing them to make their own choices, so as to improve their ability to deal with possible gossip about them and other complex interpersonal relationships.

Limitations

There are still several limitations. First, reliance on self-report data in the research may raise concerns about common method variance, but this practice has been inherent in past studies on perceptions of gossip, or in other similar measures that reflect changes in the internal state and behavior of actors. This is because the primary focus of this study was on perceptions of gossip targets rather than on actually having been the targets of gossip, and subsequent emotional and behavioral consequences. In this way, we cannot fully assess whether the perceptions of gossip about them are subjective or, in fact, have already occurred in this group. However, past research has shown that targets of gossip often know who gossiped about them. Predominantly they had heard about the gossip from the recipients, or they had learned about it accidentally (Martinescu, 2017; Dores Cruz et al., 2019a). Nevertheless, addressing this, future studies are encouraged to collect data from multiple sources and reexamine the hypotheses of this study. Similarly, the outcome variable, engaging in negative gossip, was self-reported. Thus, we also encourage reporting from multiple sources in the future.

Second, we collected three-wave data, which do not allow causal inference. Despite that, the research model is validated theoretically and empirically. Longitudinal studies and field experiments are still necessary, considering that they are more effective in causality. In this study, we predicted that being the target of gossip would lead to more gossiping itself. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that it was the gossiping of the targets that made them the target of gossip later on. Based on this, we encourage future studies to reexamine these relationships in longitudinal or experimental ways to further clarify the causation between them.

Finally, in our questionnaires, the word gossip may have negative connotations. Indeed, both a lay perspective and the available data seem to bear this out (e.g., a Dutch sample, Dores Cruz et al., 2020). Therefore, we encourage future researchers to take this into account and rule out the disturbing effects of this problem on their studies. For example, researchers could write a brief description at the top of the questionnaire to inform the participants of the theoretical definition of gossip.

Conclusion

Workplace gossip is a common phenomenon within organizations. Based on face research and AET, this research explored the mediating role of fear of losing face between negative workplace gossip and engagement in negative gossip of the targets and further included self-monitoring as a regulating factor. The results supported the hypotheses. Considering that the information contained in gossip is closely related to the parties concerned, we call for more research on gossip in the workplace and its impact on targets.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Renmin University of China. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

BZ, SX, and LZ: conceptualization. BZ and JQ: methodology. BZ: writing original draft. BZ, SX, LZ, and JQ: review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., and Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Andersson, L. M., and Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Acad. Manage. Rev. 24, 452–471. doi: 10.5465/amr.1999.2202131

Archer, J., and Coyne, S. M. (2005). An integrated review of indirect, relational, and social aggression. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 9, 212–230. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_2

Babalola, M. T., Ren, S., Kobinah, T., Qu, Y. E., Garba, O. A., and Guo, L. (2019). Negative workplace gossip: its impact on customer service performance and moderating roles of trait mindfulness and forgiveness. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 80, 136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.02.007

Bartol, K. M., and Martin, D. C. (1990). When politics pays: factors influencing managerial compensation decisions. Pers. Psychol.43, 599–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1990.tb02398.x

Baumeister, R. F., Zhang, L., and Vohs, K. D. (2004). Gossip as cultural learning. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8, 111–121. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.111

Beersma, B., and Van Kleef, G. A. (2011). How the grapevine keeps you in line: gossip increases contributions to the group. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2, 642–649. doi: 10.1177/1948550611405073

Beersma, B., and Van Kleef, G. A. (2012). Why people gossip: an empirical analysis of social motives, antecedents, and consequences. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 42, 2640–2670. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00956.x

Bell, K. (2003). Competitors, collaborators or compaions? Gossip and storytelling among political journalists in Northern Ireland. J. Soc. Anthr. Europe. 3, 2–13. doi: 10.1525/jsae.2003.3.2.2

Benjamin, B. A., and Podolny, J. M. (1999). Status, quality, and social order in the California wine industry. Admin. Sci. Quart. 44, 563–589. doi: 10.2307/2666962

Bolino, M. C., Long, D., and Turnley, W. (2016). Impression management inorganizations: critical questions, answers, and areas for futureresearch. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psych. 3, 377–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062337

Borgatti, S. P., and Halgin, D. S. (2011). On network theory. Organ. Sci. 22, 1168–1181. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0641

Bourgoin, A., and Harvey, J. F. (2018). Professional image under threat: dealing with learning–credibility tension. Hum. Relat. 71, 1611–1639. doi: 10.1177/0018726718756168

Brady, D. L., Brown, D. J., and Liang, L. H. (2017). Moving beyond assumptions of deviance: the reconceptualization and measurement of workplace gossip. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 1–25. doi: 10.1037/apl0000164

Brislin, R. W. (1980). “Translation and content analysis of oral and written material,” in Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology, eds H. C. Triandis, and J. W. Berry (Boston: Allyn & Bacon), 389–444.

Brown, B. R. (1970). Face-saving following experimentally induced embarrassment. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 6, 255–271. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(70)90061-2

Cheng, B., Dong, Y., Zhang, Z., Shaalan, A., Guo, G., and Peng, Y. (2020). When targets strike back: how negative workplace gossip triggers political acts by employees. J. Bus. Ethics. doi: 10.1007/s10551-020-04648-5. [Epub ahead of print].

Davis, A. C., Dufort, C., Desrochers, J., Vaillancourt, T., and Arnocky, S. (2018). Gossip as an intrasexual competition strategy: Sex differences in gossip frequency, content, and attitudes. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 4, 141–153. doi: 10.1007/s40806-017-0121-9

Dores Cruz, T. D., Balliet, D., Sleebos, E., Beersma, B., Van Kleef, G. A., and Gallucci, M. (2019a). Getting a Grip on the Grapevine: extension and factor structure of the motives to gossip questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 10:1190. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01190

Dores Cruz, T. D., Beersma, B., Dijkstra, M., and Bechtoldt, M. N. (2019b). The bright and dark side of gossip for cooperation in groups. Front. Psychol. 10:1374. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01374

Dores Cruz, T. D., Nieper, A. S., Testori, M., Martinescu, E., and Beersma, B. (2021). An integrative definition and framework to study gossip. Group. Organ. Manage. 46, 252–285. doi: 10.1177/1059601121992887

Dores Cruz, T. D., Thielmann, I., Columbus, S., Molho, C., Wu, J., Righetti, F., et al. (2020). Gossip and reputation in everyday life [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/y79qk

Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C., and Pagon, M. (2002). Social undermining in the workplace. Acad. Manage. J. 45, 331–351. doi: 10.5465/3069350

Eder, D., and Enke, J. L. (1991). The structure of gossip: Opportunities and constraints on collective expression among adolescents. Am. Sociol. Rev. 56, 494–508. doi: 10.2307/2096270

Ellwardt, L., Labianca, G. J., and Wittek, R. (2012). Who are the objects of positive and negative gossip at work?: A social network perspective on workplace gossip. Soc. Networks. 34, 193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2011.11.003

Feinberg, M., Willer, R., and Schultz, M. (2014). Gossip and ostracism promote cooperation in groups. Psychol. Sci. 25, 656–664. doi: 10.1177/0956797613510184

Feinberg, M., Willer, R., Stellar, J., and Keltner, D. (2012). The virtues of gossip: reputational information sharing as prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 1015–1030. doi: 10.1037/a0026650

Ferris, G. R., Fedor, D. B., and King, T. R. (1994). A political conceptualization of managerial behavior. Hum. Resour. Manage. R. 4, 1–34. doi: 10.1016/1053-4822(94)90002-7

Foster, E. K. (2004). Research on gossip: taxonomy, methods, and future directions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8, 78–99. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.78

Garland, H., and Beard, J. F. (1979). Relationship between self-monitoring and leader emergence across two task situations. J. Appl. Psychol. 64, 72–76. doi: 10.1037/h0078045

Giardini, F., and Wittek, R. P. (2019). Silence is golden. six reasons inhibiting the spread of third-party gossip. Front. Psychol. 10:1120. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01120

Gluckman, M. (1963). Papers in honor of Melville J. Herskovits: gossip and scandal. Current. Anthr. 4, 307–316. doi: 10.1086/200378

Goffman, E. (1955). On face-work: an analysis of ritual elements in social interaction. Psychiatr 18, 213–231. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1955.11023008

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction Rituals, Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Greco, L. M., Whitson, J. A., O'Boyle, E. H., Wang, C. S., and Kim, J. (2019). An eye for an eye? A meta-analysis of negative reciprocity in organizations. J. Appl. Psychol. 104, 1117–1143. doi: 10.1037/apl0000396

Grosser, T. J., Lopez-Kidwell, V., and Labianca, G. (2010). A social network analysis of positive and negative gossip in organizational life. Group. Organ. Manage. 35, 177–212. doi: 10.1177/1059601109360391

Harrison, J. K., Chadwick, M., and Scales, M. (1996). The relationship between cross-culturaladjustment and the personality variables of self-efficacy and self-monitoring. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 20, 167–188. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(95)00039-9

Harrison, J. S., Boivie, S., Sharp, N. Y., and Gentry, R. J. (2018). Saving face: how exit in response to negative press and star analyst downgrades reflects reputation maintenance by directors. Acad. Manage. J. 61, 1131–1157. doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.0471

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford publications.

Hess, N. H., and Hagen, E. H. (2019). “Gossip, reputation, and friendship in within-group competition,” in The Oxford Handbook of Gossip and Reputation, eds Giardini and R. Wittek (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 274–302. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190494087.013.15

Huang, G. H., Zhao, H. H., Niu, X. Y., Ashford, S. J., and Lee, C. (2013). Reducing job insecurity and increasing performance ratings: does impression management matter?. J. Appl. Psychol. 98, 852–862. doi: 10.1037/a0033151

Jones, D. N., and Figueredo, A. J. (2013). The core of darkness: uncovering the heart of the Dark Triad. Euro. J. Pers. 27, 521–531. doi: 10.1002/per.1893

Kilduff, M., and Lee, J. W. (2020). The integration of people and networks. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. 7, 155–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-045357

Kim, A., Moon, J., and Shin, J. (2019). Justice perceptions, perceived insider status, and gossip at work: a social exchange perspective. J. Bus. Res. 97, 30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.038

Kim, J. Y., and Nam, S. H. (1998). The concept and dynamics of face: implications for organizational behavior in Asia. Organ. Sci. 9, 522–534. doi: 10.1287/orsc.9.4.522

Kudret, S., Erdogan, B., and Bauer, T. N. (2019). Self-monitoring personality trait at work: an integrative narrative review and future research directions. J. Organ. Behav. 40, 193–208. doi: 10.1002/job.2346

Lee, H. M., Chou, M. J., and Wu, H. T. (2016). Effect of workplace negative gossip on preschool teachers' job performance: Coping strategies as moderating variable. European. J. Res. Refle. 4, 1–13.

Lee, S. H., and Barnes, C. M. (2020). An attributional process model of workplace gossip. J. Appl. Psychol. 106, 300–316. doi: 10.1037/apl0000504

Li, X., McAllister, D. J., Ilies, R., and Gloor, J. L. (2019). Schadenfreude: a counternormative observer response to workplace mistreatment. Acad. Manage. Rev. 44, 360–376. doi: 10.5465/amr.2016.0134

Liu, L. A., Friedman, R., Barry, B., Gelfand, M. J., and Zhang, Z. X. (2012). The dynamics of consensus building in intracultural and intercultural negotiations. Adm. Sci. Q. 57, 269–304. doi: 10.1177/0001839212453456

Liu, X. Y., Kwan, H. K., and Zhang, X. (2020). Introverts maintain creativity: a resource depletion model of negative workplace gossip. Asia. Pac. J. Manage. 37, 325–344. doi: 10.1007/s10490-018-9595-7

Loughry, M. L., and Tosi, H. L. (2008). Performance implications of peer monitoring. Organ. Sci. 19, 876–890. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1080.0356

Mak, W. W., Chen, S. X., Lam, A. G., and Yiu, V. F. (2009). Understanding distress: the role of face concern among Chinese Americans, European Americans, Hong Kong Chinese, and mainland Chinese. Couns. Psychol. 37, 219–248. doi: 10.1177/0011000008316378

Martinescu, E. (2017). Why we Gossip: A Functional Perspective on the Self-Relevance of Gossip for Senders, Receivers and Targets. Groningen: University of Groningen.

Martinescu, E., Jansen, W., and Beersma, B. (2021). Negative gossip decreases targets'organizational citizenship behavior by decreasing social inclusion. a multi-method approach. Group. Organ. Manage. doi: 10.1177/1059601120986876. [Epub ahead of print].

Martinescu, E., Janssen, O., and Nijstad, B. A. (2019a). Self-evaluative and other-directed emotional and behavioral responses to gossip about the self. Front. Psychol. 9:2603. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02603

Martinescu, E., Janssen, O., and Nijstad, B. A. (2019b). “Gossip and emotion,” in The Oxford Handbook of Gossip and Reputation, (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 152. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190494087.013.9

McAndrew, F. T., Bell, E. K., and Garcia, C. M. (2007). Who do we tell and whom do we tell on? Gossip as a strategy for status enhancement. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 37, 1562–1577. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00227.x

Milinski, M. (2016). Reputation, a universal currency for human social interactions. Philos. T. R. Soc. B. 371, 20150100. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0100

Mills, C. (2010). Experiencing gossip: the foundations for a theory of embedded organizational gossip. Grou. Organ. Manage. 35, 213–240. doi: 10.1177/1059601109360392

Miron-Spektor, E., Paletz, S. B., and Lin, C. C. (2015). To create without losing face: the effects of face cultural logic and social-image affirmation on creativity. J. Organ. Behav. 36, 919–943. doi: 10.1002/job.2029

Muthen, L. K., and Muthen, B. O. (2012). Mplus User's Guide. 7th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Noon, M., and Delbridge, R. (1993). News from behind my hand: Gossip in organizations. Organ. Stud. 14, 23–36. doi: 10.1177/017084069301400103

Oh, H., and Kilduff, M. (2008). The ripple effect of personality on social structure: self-monitoring origins of network brokerage. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 1155–1164. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1155

Piazza, J., and Bering, J. M. (2008). Concerns about reputation via gossip promote generous allocations in an economic game. Evol. Hum. Behav. 29, 172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.12.002

Podsakoff, P. M., and Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J. Manage. 12, 531–544. doi: 10.1177/014920638601200408

Shank, D. B., Kashima, Y., Peters, K., Li, Y., Robins, G., and Kirley, M. (2019). Norm talk and human cooperation: Can we talk ourselves into cooperation?. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 117, 99–123. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000163

Shaw, A. K., Tsvetkova, M., and Daneshvar, R. (2011). The effect of gossip on social networks. Complexity 16, 39–47. doi: 10.1002/cplx.20334

Smart Richman, L., and Leary, M. R. (2009). Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: a multimotive model. Psych. Rev. 116, 365–383. doi: 10.1037/a0015250

Snyder, M. (1979). Self-monitoring processes. Adv. Expt. Social. Psyc. 12, 85–128. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60260-9

Snyder, M., and Gangestad, S. (1982). Choosing social situations: two investigations of self-monitoring processes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 43, 123–135. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.1.123

Snyder, M., and Gangestad, S. (1986). On the nature of self-monitoring: matters of assessment, matters of validity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 125–139. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.125

Spence, A. M. (1974). Market Signaling: Informational Transfer in Hiring and RelatedScreening Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tassiello, V., Lombardi, S., and Costabile, M. (2018). Are we truly wicked when gossiping at work? The role of valence, interpersonal closeness and social awareness. J. Bus. Res. 84, 141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.013

Tian, Q. T., Song, Y., Kwan, H. K., and Li, X. (2019). Workplace gossip and frontline employees' proactive service performance. Serv. Ind. J. 39, 25–42. doi: 10.1080/02642069.2018.1435642

Tuncel, E., Kong, D. T., Parks, J. M., and van Kleef, G. A. (2020). “Face threat sensitivity in distributive negotiations: Effects on negotiator self-esteem and demands,” in Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 161, (Elsevier), 255–273. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.07.004

Turnley, W. H., and Bolino, M. C. (2001). Achieving desired images while avoiding undesired images: exploring the role of self-monitoring in impression management. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 351–360. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.2.351

Watson, D. C. (2011). Gossip and the self. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 41, 1818–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00772.x

Wayne, S. J., and Ferris, G. R. (1990). Influence tactics, affect, and exchange quality in supervisor-subordinate interactions: a laboratory experiment and field study. J. Appl. Psychol. 75, 487–499. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.75.5.487

Weiss, H. M., and Cropanzano, R. (1996). “Affective eventstheory: a theoretical discussion of the structure, causes, and consequences of affective experiences at work,” in Research Inorganizational Behavior, eds B. M. Staw, and L. L. Cummings (Greenwich, CT: ElsevierScience/JAI Press), 1–74.

Wert, S. R., and Salovey, P. (2004). A social comparison account of gossip. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8, 122–137. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.122

Wu, C. H., Kwan, H. K., Liu, J., and Lee, C. (2021). When and how favour rendering ameliorates workplace ostracism over time: Moderating effect of self-monitoring and mediating effect of popularity enhancement. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 94, 107–131. doi: 10.1111/joop.12328

Wu, J., Balliet, D., and Van Lange, P. A. (2016). Reputation, gossip, and human cooperation. Social. Personal. P 10, 350–364. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12255

Wu, L. Z., Birtch, T. A., Chiang, F. F., and Zhang, H. (2018). Perceptions of negative workplace gossip: a self-consistency theory framework. J. Manage. 44, 1873–1898. doi: 10.1177/0149206316632057

Wu, X., Kwan, H. K., Wu, L. Z., and Ma, J. (2018). The effect of workplace negative gossip on employee proactive behavior in China: the moderating role of traditionality. J. Bus. Ethics. 148, 801–815. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-3006-5

Xie, J., Huang, Q., Wang, H., and Shen, M. (2019). Coping with negative workplace gossip: the joint roles of self-monitoring and impression management tactics. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 151:109482. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.06.025

Ye, Y., Zhu, H., Deng, X., and Mu, Z. (2019). Negative workplace gossip and service outcomes: an explanation from social identity theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manage. 82, 159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.04.020

Zane, N., and Yeh, M. (2002). “The use of culturally-based variables in assessment: Studies on loss of face,” in Asian American Mental Health, eds K. Kurasaki, S. Okazaki, and S. Sue (Norwell, MA: Kluwer), 123–138. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0735-2_9

Zhang, X. A., Cao, Q., and Grigoriou, N. (2011). Consciousness of social face: The development and validation of a scale measuring desire to gain face versus fear of losing face. J. Soc. Psychol. 151, 129–149. doi: 10.1080/00224540903366669

Zhou, A., Liu, Y., Su, X., and Xu, H. (2019). Gossip fiercer than a tiger: Effect of workplace negative gossip on targeted employees' innovative behavior. Soc. Behav. Personl. 47, 1–11. doi: 10.2224/sbp.5727

Keywords: negative workplace gossip, gossip, face, self-monitoring, affective events theory

Citation: Zong B, Xu S, Zhang L and Qu J (2021) Dealing With Negative Workplace Gossip: From the Perspective of Face. Front. Psychol. 12:629376. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.629376

Received: 14 November 2020; Accepted: 03 May 2021;

Published: 03 June 2021.

Edited by:

Antje Schmitt, University of Groningen, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Terence Daniel Dores Cruz, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, NetherlandsSusan Reh, University of Exeter, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Zong, Xu, Zhang and Qu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shiyong Xu, eHVzeUBydWMuZWR1LmNu

Boqiang Zong

Boqiang Zong Shiyong Xu2*

Shiyong Xu2*