- 1Applied Research Division for Cognitive and Psychological Science, European Institute of Oncology, IRCCS, Milan, Italy

- 2Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, and Health Studies, Faculty of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

- 3Division of Gastrointestinal Medical Oncology and Neuroendocrine Tumors, European Institute of Oncology, IRCCS, Milan, Italy

- 4Department of Oncology and Hemato-Oncology, University of Milan, Milan, Italy

Background: The role of personality in cancer incidence and development has been studied for a long time. As colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most prevalent cancer types and linked with lifestyle habits, it is important to better understand its psychological correlates, in order to design a more specific prevention and intervention plan. The aim of this systematic review is to analyze all the studies investigating the role of personality in CRC incidence.

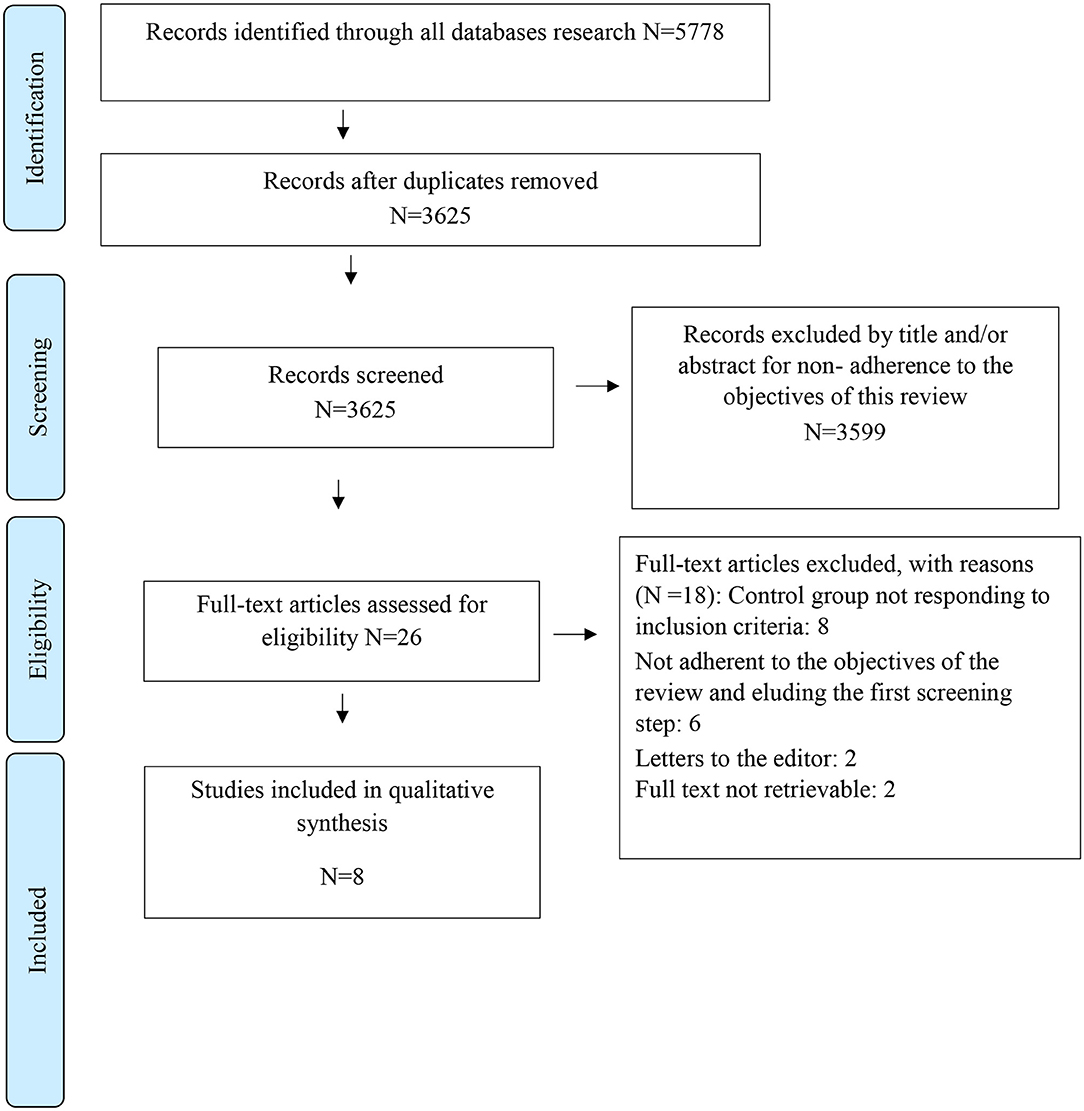

Methods: All studies on CRC and personality up to November 2020 were scrutinized according to the Cochrane Collaboration and the PRISMA statements. Selected studies were additionally evaluated for the Risk of Bias according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Results: Eight studies met the inclusion criteria and were eventually included in this review. Two main constructs have been identified as potential contributors of CRC incidence: emotional regulation (anger) and relational style (egoism).

Conclusion: Strong conclusions regarding the influence of personality traits on the incidence of CRC are not possible, because of the small number and the heterogeneity of the selected studies. Further research is needed to understand the complexity of personality and its role in the incidence of CRC and the interaction with other valuable risk factors.

Introduction

Colorectal Cancer (CRC), a tumor affecting the large intestine that includes the ascending, transverse, descending and rectal tract, is the third most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer deaths, with approximately 1.9 million new cases and 935,000 deaths worldwide reported in 2020, according to World Health Organization Globocan database (Sung et al., 2021). The 1-year survival rate is about 80% after diagnosis. The 5-year rate is between 45 and 65% in developed countries and between 8 and 45% in developing countries (Keum and Giovannucci, 2019). Industrialization and economic growth have worsened the situation, promoting a sedentary lifestyle, poor dietary habits, alcohol consumption and smoking (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Murphy et al., 2019). Such behavioral factors, together with environmental and genetic factors are considered among the major risk factors for CRC development (Murphy et al., 2019). The impact of psychological factors on the incidence of CRC has been studied including anxiety and depression (Kroenke et al., 2005) and perceived stress (Kikuchi et al., 2017). Such studies are coherent with paradigms that consider psychological components and personality characteristics as factors affecting mortality (Roberts et al., 2007; O'Súilleabháin et al., 2021). According to recent works, psychological traits seem to share a common pathogenic mechanism typical of increased mucosal inflammation, metabolic parameters and proinflammatory status (Mancini et al., 2020). In line with this, an increasing number of studies are equating psychosocial factors (depression, anxiety, hostility, social isolation) to biological factors (smoking, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, obesity, diabetes) in the pathogenesis of several diseases (Attilio et al., 2018). In the oncological field, a meta-analysis carried out on 165 controlled studies showed that stress-prone personality or unfavorable coping styles and negative emotional responses are related to an increased incidence of cancer, a worse prognosis and an increase in mortality (Chida et al., 2008).

Considering the multifactorial characterization of CRC, the aim of the present work was to investigate the psychological factors that may affect the incidence of CRC. Some studies (Schoormans et al., 2017; Lloyd et al., 2019; Coker et al., 2020) investigated personality characteristics either as outcomes of diagnosis and oncological treatments or as predictors of recovery from cancer. Fewer studies investigated the contribution of such characteristics on the incidence of CRC.

Personality can be defined as “relatively stable ways of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others” (Lingiardi and McWilliams, 2017). Coherently with such a definition, expression of personality can be found in specific actions that allows the individual to protect him or herself from emotional hazards and to adaptively connect with the environment and with others. These protective and adaptive actions move along a continuum from full awareness to unconsciousness, with deliberative behaviors on one extreme, defensive mechanisms (Butow et al., 2000; Drageset and Lindstrøm, 2003; Beresford et al., 2006; Chida et al., 2008; Perry et al., 2015), on the other extreme and coping style (Neeleman et al., 2004; Perry et al., 2015) in between. In this perspective, personality denotes the kind of adaptation that individuals make to the external environment, including life-styles (Sutin et al., 2019), and health related behaviors. Similarly, personality features such as conscientiousness and neuroticism (Nakaya et al., 2010; Grov and Dahl, 2020) have been related to obesity (Mills et al., 2018) and dietary habits (Lutgendorf and Sood, 2011). If personality is related to behaviors, behaviors seem to be related to diseases. In particular, behavioral and life-style patterns as dietary habits, physical inactivity, obesity and abdominal fat, smoking and alcohol consumption have been associated with the incidence of diseases such as CRC (Murphy et al., 2019). Such personality and behavioral factors may influence cancer development and progression through mechanisms such as cellular immune response, oxidative stress, invasion, angiogenesis and inflammation (Jaffe, 2013; Di Giuseppe et al., 2018; O'Súilleabháin et al., 2021). However, studies investigating premorbid common traits in individuals developing any type of cancer showed controversial results: some large-scale cohort studies found no association between personality and cancer incidence (Temoshok, 1987; Jokela et al., 2014), while other studies did (Lemogne et al., 2013; Dong and Jin, 2018). In another study, Type C (or cancer prone personality, that implies the suppression of feeling and/or expression of negative emotions, focus on others' needs more than on one's own, unassertiveness, cooperation and acceptance) (Wellisch and Yager, 1983) and Type D (or depressed that means negative affectivity and social inhibition) personalities have been the object of investigation. More specifically, according to Temoshok (1987), Type C personality is associated with the weakening of the immune system and consequently the risk of developing cancer. Other authors hypothesized that reactions of helplessness and hopelessness to stressors are predictive of a worse outcome in breast cancer patients (Greer et al., 1979) or incidence of a new cancer in individuals (Greer and Watson, 1985). However, as Wellisch and Yager (1983) argued, not all types of cancer are the same and searching for common personality traits in individuals with different types of cancer could obscure features related to some specific sub-types. In the case of CRC, several studies investigated the role of personality on specific outcomes following a cancer diagnosis and treatment. For example, there is evidence of the role of personality characteristics [such as emotional lability, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, conscientiousness (Paika et al., 2010), denial and sense of coherence (Hyphantis et al., 2011), repression and sense of coherence (Glavić et al., 2014) or neuroticism (Ristvedt and Trinkaus, 2005)] in predicting Quality of Life (QoL) and illness perception (Mols et al., 2012a; Schoormans et al., 2017) after cancer and related treatments. In other studies, Type D Personality and its components (negative affectivity and social inhibition) were associated with all-cause mortality (Shun et al., 2011), worse QoL in different domains (Shun et al., 2011; Mols et al., 2012b; Husson et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016) and most disease-specific symptoms (Zhang et al., 2016) in CRC patients. Beside the importance of personality in coping with cancer after a diagnosis, this review wants to focus on personality as a contributing risk factor for the incidence of CRC. Indeed, recent studies illustrated the need to consider also psychological and behavioral factors, besides genetic and environmental factors, to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the determinants underlying the incidence of CRC. Moreover, as personality refers to stable characteristics that affect individuals' behavior across different life domains, we were interested to investigate whether specific personality patterns are more likely to be associated with CRC incidence. To the best of our knowledge, a systematic review on personality features related to the incidence of CRC has never been realized.

Methods

Search Strategy

The procedure has been conducted according to the PRISMA statement (Moher et al., 2009). To include the broadest range of relevant literature, an electronic search was conducted on the major databases in the field of health and social sciences: Pubmed, Scopus, Embase, PsycInfo, Ovid, and Web of Science. The search was performed using Mesh terms/Keywords (depending on the database) with the same search strategy: “Colorectal neoplasm,” “Colon-Rectal Cancer” OR “Colorectal cancer” OR “Rectal cancer” OR “Colon cancer” OR “bowel cancer” AND “Personality” OR “Personality disorder” OR “Temperament” OR “Character.” The use of Mesh terms further guaranteed the complete description of any aspect of the main subject (personality). Our definition of personality pertains to a continuum, ranging from healthy (personality traits and styles, character, temperament) to the pathologic (e.g., personality disorders) in order to catch the widest number of papers on the topic. The choice of the keywords reflects the wide range definition of personality that we adopted.

The search was limited to papers in English published up to November 30th 2020. An additional analysis of the reference list of each selected paper was also performed. If the full text was not retrievable, the study was excluded.

Inclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were adopted in the articles' selection phase: (1) Studies with an analytical study design as defined by Grimes and Schulz (2002), in particular prospective and retrospective, case-control, longitudinal, cohort studies, randomized and clinical trials; (2) studies concerning the incidence of CRC with a confirmed histology, without time limits after diagnosis; (3) studies published in English.

Exclusion Criteria

The following exclusion criteria were adopted: (1) studies that evaluated the role of personality on patients' outcomes after diagnosis and treatment; (2) articles investigating the contribution of personality on recurrence and on cancer survivorship; (3) studies based on animal models; (4) letters, commentaries, editorials, case reports, conference papers, book chapters, reviews, meta-analyses; (5) Self-reported diagnosis of CRC; (6) Correlational studies (also cohort studies without comparison/control group(s) have not been included); (7) Number of subjects per group ≤ 20 to have a stronger statistical power.

Data Extraction

Study selection was performed by two independent reviewers with research expertise in general and clinical psychology (FG and LS) who assessed the relevance of the study for the objectives of this review. After the initial step of identification of records through different databases and duplicate removal, the following phase (screening) was the selection of papers on the base of title, abstract, and keywords of each study. The full text was retrieved, if the reviewers did not reach a consensus or the abstract did not contain sufficient information.

In the phase of eligibility, all full-texts were retrieved and a final check was made to exclude papers not responding to inclusion/exclusion criteria. A final consensus to decide the inclusion in the final selection was taken.

A standardized data extraction form was prepared; data were independently extracted by two of the authors (FG and LS) and inserted into a study database. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by a process of discussion/consensus moderated by a third reviewer (KM) (Furlan et al., 2009) (Figure 1).

Statistical Methods

A systematic analysis was conducted according to the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines (Higgins and Green, 2011) and the PRISMA Statement (Moher et al., 2009). It was not considered appropriate to undertake a meta-analysis as the included studies were highly heterogeneous in terms of variables, instruments and outcomes (Higgins and Green, 2011).

Risk of Bias

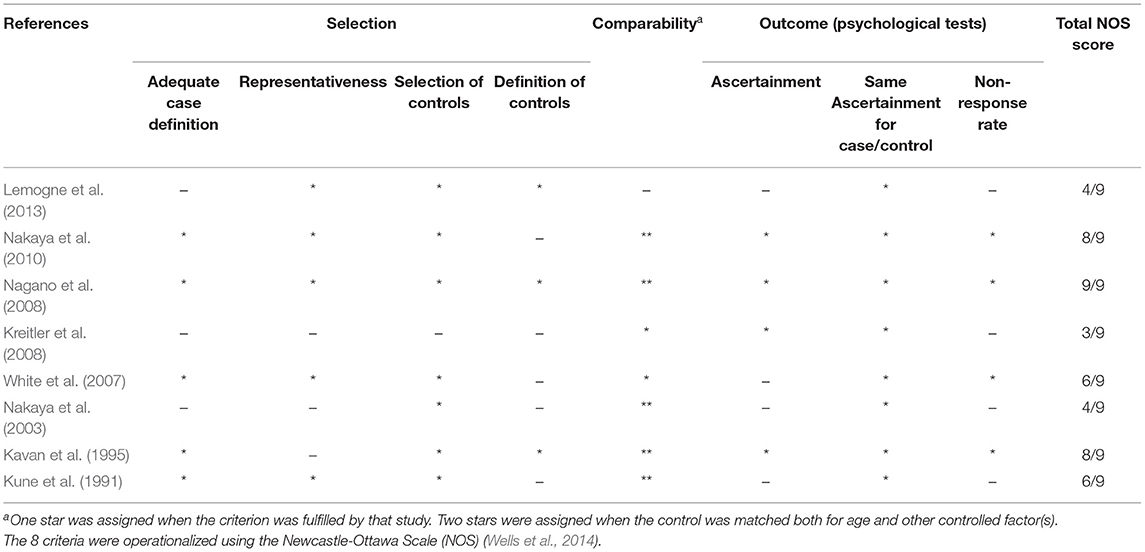

Quality assessment of each of the included studies was evaluated following the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for case-control studies on a 9-star model (Wells et al., 2014) (Table 2). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale quality instrument is scored by awarding a point for each question in relation to the following categories: selection comparability and outcome. Possible total scoring is four points for Selection, two points for Comparability, and three points for Outcomes. Two reviewers (LS and FG) independently extracted relevant information and data from all eligible studies according to the appropriate inclusion criteria. Studies scoring above the median NOS value were considered as high quality (low risk of bias) and those scoring below the median value were considered as low quality (high risk of bias).

Characteristics of Study Populations

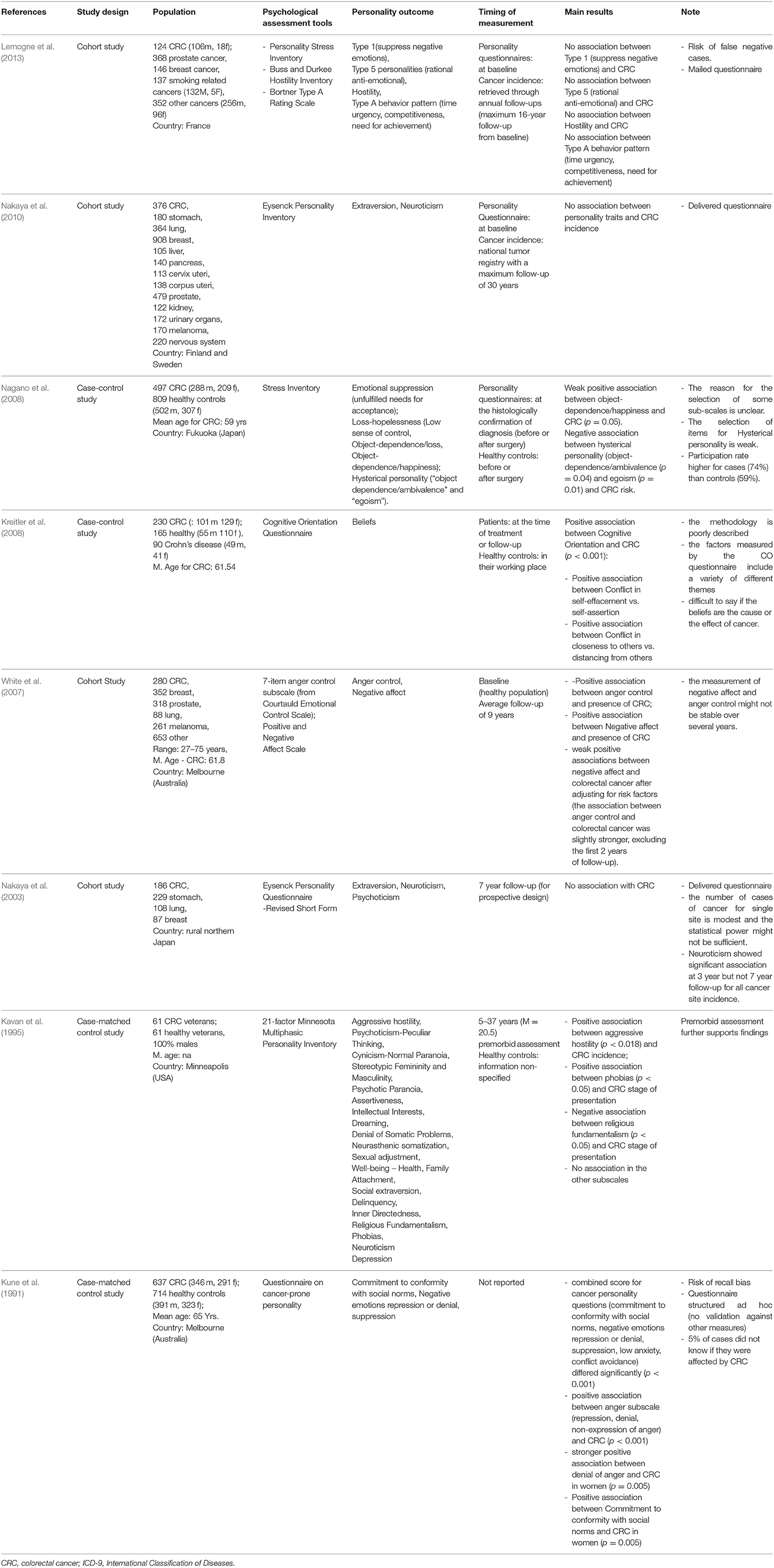

The overall number of CRC patients in the examined studies was 3,105 (Table 1). CRC patients were at different disease stages and/or treatment stages (undergoing/undergone surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy). Healthy controls were 75,097 while other cancer controls (prostate cancer, breast, lung or smoking-related cancer) were 8,128 (Table 1).

Results

Eight studies were included in the final qualitative analysis. Table 1 reports the details of all the selected studies (Kune et al., 1991; Kavan et al., 1995; Nakaya et al., 2003, 2010; White et al., 2007; Kreitler et al., 2008; Nagano et al., 2008; Lemogne et al., 2013).

Characteristics of Reviewed Studies

Psychological Assessment Tools

All the selected studies adopted differing instruments of assessment (see Table 1): questionnaires on cancer-prone personality (Questionnaire on cancer-prone personality) (Kune et al., 1991), questionnaires grounded on specific theories as the Personality Stress Inventory (Lemogne et al., 2013), the Stress Inventory (Nagano et al., 2008), the Buss and Durkee Hostility Inventory (Lemogne et al., 2013), the Bortner Type A Rating Scale (Lemogne et al., 2013), the Cognitive Orientation Questionnaire (Kreitler et al., 2008), the Courtauld Emotional Control Scale (White et al., 2007) or more acknowledged ones as the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (White et al., 2007) for the evaluation of negative or positive affect, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (Kavan et al., 1995) and the Eysenck Personality Inventory (Nakaya et al., 2003, 2010) for the assessment of personality.

Timing of Assessment

The follow-up period ranged from 0 (coincident with the moment of CRC diagnosis) to 37 years.

Research Design

Out of the eight studies, four adopted a case-control design (Kune et al., 1991; Kavan et al., 1995; Kreitler et al., 2008; Nagano et al., 2008) while the remaining four were cohort studies (Nakaya et al., 2003, 2010; White et al., 2007; Lemogne et al., 2013).

Case-Control Studies

The study by Kavan et al. (1995) was conducted on a sample of 124 male veterans living in Minneapolis (USA) who completed the personality questionnaire (MMPI) between 1947 and 1975. Among those, 61 were identified through the regional tumor registry as having had a colon cancer diagnosis in the years between 1977 and 1988. The interval between the MMPI completion and colon cancer diagnosis ranged from 5 to 37 years. The 61 control cases were matched for age, education and source of referral for medical care.

Nagano et al. (Nagano et al., 2008) recruited 497 newly diagnosed CRC patients (age: 20–74) from 8 large hospitals in the Fukuoka area of Japan and 809 controls (age: 20–74) matched by gender and age and randomly selected in the same community area. A survey was performed by a research nurse during which questionnaires on personality and health habits were administered before or after surgery for cases and controls.

In Kreitler et al.'s study (Kreitler et al., 2008) 230 patients with CRC (mean age: 61.54) were compared with 90 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of Crohn's disease and with 165 healthy controls. The proportions of men in the three groups are were 33.3, 50.6, and 43.9%, respectively. No other information on the sample and on recruiting methods was reported.

The case-control study by Kune et al. (1991) involved 637 patients (346 males and 291 females) with first diagnosis of CRC between April 1980 and April 1981 and resident in Melbourne. Seven hundred and fourteen controls (391 males and 323 females) were randomly selected from the Community of the Metropolitan Melbourne area, and matched with cases according to age and gender.

Cohort Studies

Nakaya et al. (2010) conducted a prospective study based on combined data of Swedish twins and singletons (N = 29,828; age range: <20–49) born before 1958 and that responded to the baseline questionnaire in 1973 and of Finnish twins and singletons (N = 29,720; age range: <20–>70) born before 1958 and that responded to the baseline questionnaire in 1975. Information on cancer diagnoses was obtained by record linkage to the national cancer registries in Finland and Sweden, both holding information on all cases of cancer diagnosed since 1958. Personality was measured at baseline, together with socio-demographic information and health habits. Information on cancer diagnosis was retrieved by record linkage to the national cancer registries in Finland and Sweden with a maximum 30-year follow-up. Another study conducted by Nakaya et al. (2003) investigated the role of personality on cancer risk in 30,277 persons (age range: 40–64) living in northern Japan from June through August 1990. Questionnaires on personality and health habits were collected at the participants' residences by the health promotion committees appointed by the government. Information on cancer incidence was collected through the linkage with the Prefectural Cancer Registry that covers the study area, for a maximum of 7-years follow-up. Lemogne et al. (2013) conducted a cohort study on a target population consisting of 44,992 employees of the French national gas and electricity company. Among those, 20,625 employees (45.8%) (15,011 men and 5,614 women) volunteered to participate and 20,488 completed the survey. Among these, personality measures were available at baseline for 13,768 participants. Annual follow-ups to check for diagnosis of primary cancer were conducted from 1994 to 2009. Diagnoses self-reported by patients were verified through the French national cause-of-death registry.

The study by White et al. (2007) included a cohort of 19,730 participants (aged range: 27–75) recruited from 1990 to 1994 in Melbourne, Australia. Participants completed a questionnaire on personality, health habits, biological and demographic variables in an assessment center. Physical assessments (e.g., blood test, height, weight) were also performed. Cancer diagnoses were identified by record linkage to the State Cancer Registry during the follow-up period (average follow-up: 9 years).

Risk of Bias

Five studies were quoted as high quality (low risk of bias) and three were low quality (high risk of bias) by NOS (see Table 2).

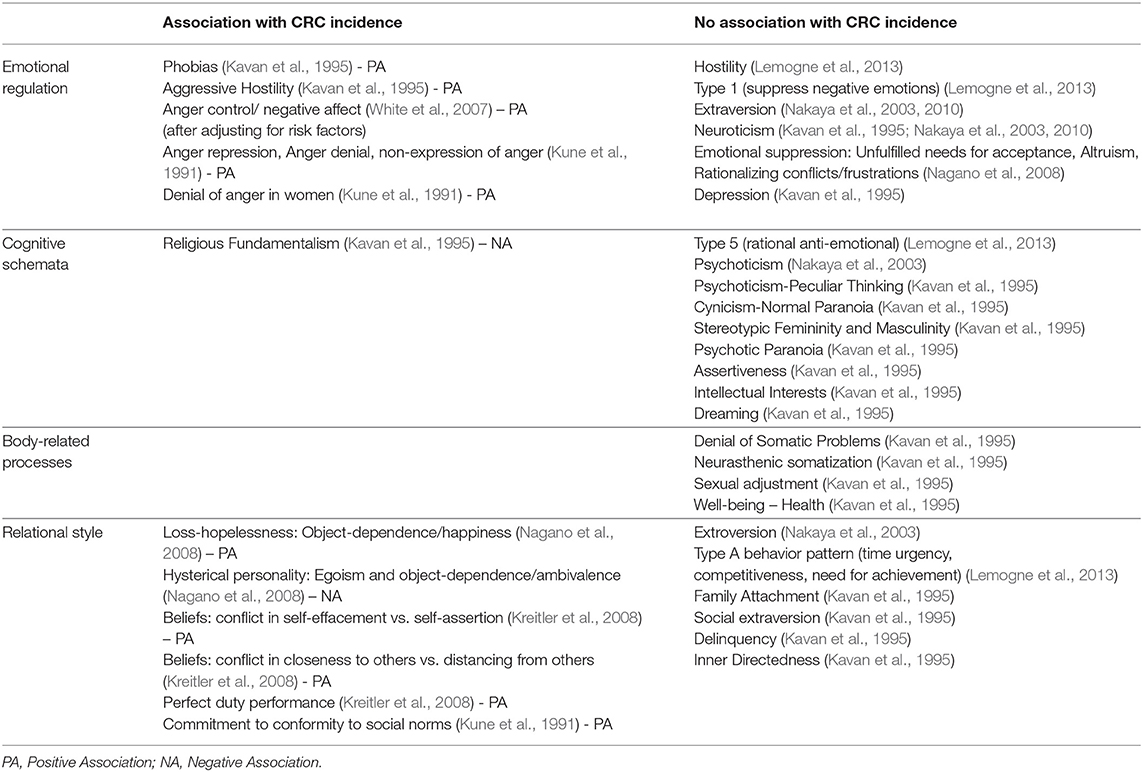

Narrative Synthesis on Personality Characteristics

Relative to the specific personality characteristics, the studies presented a high heterogeneity in the type of characteristics assessed and in the assessment measures (see Table 1). We divided them into 4 main categories: emotional regulation, cognitive schemata, body-related processes and relational style (see Table 3).

Emotional Regulation

ER refers to the processes that individuals use to identify which emotions they have, when they have them, and how these emotions are experienced and expressed (Gross, 2002). Two studies (Kavan et al., 1995; Lemogne et al., 2013) investigating the role of Hostility, showed opposing results. More specifically, Kavan et al. (1995) found that the two factors that significantly discriminated between CRC patients and healthy controls, among those measured by the MMPI, were Phobias and Aggressive Hostility, with a higher level of these variables in CRC patients compared to healthy subjects. On the contrary, Lemogne et al. (2013) did not find any association between incidence of CRC and Hostility and Type 1 (suppress negative emotions). However, it is worth noting that Lemogne used questionnaires different from MMPI. Similarly, two other studies found opposing results for repression/denial of emotions (Kune et al., 1991; Nagano et al., 2008). Kune et al. (1991) showed a positive significant association between such characteristics and incidence of CRC. More specifically, compared to healthy control subjects, cancer patients presented a higher tendency of denial and repression of negative emotions and suppression of negative emotional reactions. Indeed, Nagano et al. (2008) demonstrated no association between emotional suppression (measured with the Stress Inventory) and incidence of CRC.

Similar to Kune et al. (1991) and White et al. (2007), in a prospective study, found a weak positive association between negative affect and colorectal cancer incidence, but only after adjusting for risk factors such as dietary habits or smoking. A similar trend for anger control was present from the third year of follow-up. Regarding neuroticism, that is a trait linked to negative affect, including anger, anxiety, irritability, emotional instability (Gross, 2002) it has been measured by three studies: in the study by Kavan et al. (1995) in which MMPI-2 was used no differences were found between cancer patients and the matched healthy controls. Similarly, the study by Nakaya et al. (2003) using EPQ did not find any differences. In a later study (Nakaya et al., 2010), they confirmed that no association exists between neuroticism or any other personality characteristics (Extraversion) on incidence of CRC, using the same questionnaire in a revised version (EPI).

Cognitive Schemata

Cognitive schemata refer to mental structures that individuals use to organize knowledge and guide cognitive processes and behavior (Kite and Whitley, 2016). They are models built on experiences, they are stable and automatic and allow individuals to respond effortlessly to the environment and to adapt to it.

Cognitive schemata such as personality-related aspects can be represented by the factors measured by MMPI-2 (e.g., Cynicism-Normal Paranoia, Religious Fundamentalism, Dreaming, Psychotic Paranoia; Stereotypic Femininity and Masculinity) (Kavan et al., 1995). Only the Religious Fundamentalism seems to be negatively associated with CRC incidence. No association was found for Type 5 (rational anti-emotional) (Lemogne et al., 2013) and Psychoticism (Nakaya et al., 2003).

Relational Style

Relational style refers to the attitude people adopt when they relate to others. In particular, people naturally respond to internal and external requests. However, they may show a propensity to believe and behave with others with a self-oriented attitude or with an others-oriented attitude. Nagano et al. (2008) investigated such attitudes using the hysterical personality scale of the Stress Inventory. The hysterical personality scale is characterized by two sub-scales: egoism (a self-defensive, self-interest-oriented attitude) and object-dependence/ambivalence (oscillation between idealizing and devaluing an object or a person). The study showed a negative relationship between CRC risk and the two subscales of egoism and object-dependence/ambivalence. In this perspective, egoism and independence from others are protective factors for CRC. The importance of the focus on relationships can be seen also in Kreitler's findings (Kreitler et al., 2008): according to them, perfect duty performance, the conflict between self-effacement vs. self-assertion, and the conflict between closeness to others vs. distancing from others are the personality risk factors of colorectal cancer. Perceiving the conflict between listening and pursuing the personal needs (self-assertion) vs. the others' requests has been demonstrated as a risk factor for CRC, confirming the protective role of egoism described by Nagano et al. (2008). Extroversion (Nakaya et al., 2003), Type A (Lemogne et al., 2013), Family attachment (Kavan et al., 1995), Delinquency (Kavan et al., 1995), Social Extroversion (Kavan et al., 1995) and Inner directedness (Kavan et al., 1995) did not show significant associations with CRC incidence.

Body-Related Processes

Few dimensions that, in our opinion, had a lower fit with the previous categories were those related to the body as a relevant component of processes that define the way individuals feel, think and behave or interact with the self and the world. Kavan et al. (1995) used the MMPI-2 questionnaire that provides information related to the body (e.g., neurasthenic somatization or denial of somatic problems), that can be viewed as object of a possible pathology or dysfunction. No association was found between body-related factors and CRC incidence.

Discussion and Conclusion

This systematic review showed that scant studies exist on the contribution of personality features in CRC incidence, with only eight studies reflecting the criteria of selection. Summing up the findings from the different studies, we cannot indisputably conclude that there is a data-driven role of personality in the incidence of CRC. More specifically, 4 out of the 8 analyzed studies found a positive association between the investigated personality dimensions [phobias (Kavan et al., 1995); emotional repression/denial (Kune et al., 1991); commitment to conformity to social norms (Kune et al., 1991); anger control/negative affect (White et al., 2007); conflict in self-assertion vs. self-effacement (Kreitler et al., 2008); conflict between closeness to and distance from others (Kreitler et al., 2008); aggressive hostility (Kavan et al., 1995); loss/hopelessness (Nagano et al., 2008)], perfect duty performance (Kreitler et al., 2008) and cancer incidence. Two studies found a negative association for egoism or object-dependence/ambivalence (Nagano et al., 2008) and with religious fundamentalism (Kavan et al., 1995) with CRC. The remaining 3 studies (Nakaya et al., 2003, 2010; Lemogne et al., 2013) found no association between personality dimensions and CRC incidence.

In synthesis, we can state that among personality factors the constructs of emotional regulation and relational style gathered the most part of the studies. The role of anger regulation received a consistent attention across different studies, and it might be related to CRC incidence. However, the small number of studies, the different methods of assessment and direction of the findings do not allow any clear conclusion. However, the involvement of a dysregulation of the anger control system warrant further study in the field of CRC. Anger means a cascade of events through multiple communication pathways, including autonomic and immune system, neurotransmitters, and an inflammatory cascade via the gut-brain axis potentially influencing intestinal microbiota (Huanga et al., 2021). We still do not know if long-lasting abnormal anger control may lead to gut dysbiosis-mediated inflammation which may affect colon epithelium influencing carcinogenesis (Otegbeye et al., 2021).

On the side of relational style, we note the protective role of egoism that is the only item negatively associated and it may be a topic of interest in future studies. Moreover, we underline a likely role for dimensions related to conflict aspects on the incidence of CRC. The categories of cognitive schemata and body-related processes did not reveal any relevant feature potentially related to CRC incidence. Additionally, we did not find studies outlining any significant association with categories of psychopathological meanings (e.g., neuroticism or depression).

Further studies that adopt a stronger methodology and a more homogeneous theory of personality that integrate different approaches are needed, with personality dimensions assessed over a continuum and not as simple categories (Galli et al., 2019). A topic of interest may be the study of the role of personality disorders on the CRC incidence as classified by the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) or PDM (Lingiardi and McWilliams, 2017). We know that individuals with personality disorders show an increased risk of negative health outcome (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015).

The examined studies showed lack of consistency and often contradictory findings. It was also difficult to compare results since each survey used different diagnostic tools to investigate psychological predictors. Further, studies adopted different research strategies (e.g., cohort or case-control studies, prospective or retrospective, self-assessment or clinical interviews, in-patients or subjects from national registries) and again the comparison of results was difficult. Accordingly, we need further studies adopting stronger methodology and theory of psychological functioning. Heterogeneity of results may be due to two main factors: (1) patients involved in the studies were at different stages of disease and treatment (2) different tools investigated various predictors, although similar in some cases. Difficulties of measuring personality before disease and the long time requested for such longitudinal studies could explain differences and contradictory findings. Furthermore, the study of personality should be always carried out controlling as additional covariates factors as lifestyle habits (e.g., inactivity) and nutritional factors (e.g., quantity of red/processed meat). Additionally, the inconsistency of results among studies could be explained by the absence of data on the interaction or mediation effect by other intervening variables. In this perspective, and in line with the new trends of research on big data, other psychological constructs (e.g., dispositional optimism, coping style, and self-efficacy), lifestyle habits (e.g., inactivity, smoking, nutrition), genetic and environmental factors should be investigated and analyzed together, in order to provide a more comprehensive profile of the specific cancer patient profile. The investigation of single or only a few isolated aspects that characterize the person, in his/her thinking, feeling, behavioral and relational components is one of the main shortcomings of the different studies included in the present review.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on the role of personality characteristics in CRC incidence, although we appreciate that our study has limitations. The definition of personality and its peculiarities is ongoing in a framework of complexity and different theoretical models, and the possibility that some studies had not been included in our review is not to be ruled out.

The prevention of CRC is a public health problem, and personalized strategies for prevention should be implemented (Oliveri et al., 2019), as modifiable risk factors are related to CRC. Furthermore, CRC incidence and mortality can be greatly reduced by screening, and again public health policies should take into account factors that may contribute to the risk of cancer, in order to tailor intervention based on specific profiles. Healthcare systems are gradually moving in the direction of personalized medicine where patients' needs, preferences and well-being are the main focus to address (Kondylakis et al., 2017; Galli and Pravettoni, 2020). The study of personality could be another key to include in the framework of any personalized approach (Gorini et al., 2015; Kondylakis et al., 2020). The development of electronic platforms that allow patients to communicate with their doctors, already allows several types of data to be gathered. This may represent an opportunity to integrate additional variables that would otherwise be difficult to collect in a single study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

The review was conceived by FG and KM. Data extraction was carried out by FG and LS with support by KM. Reporting of findings was led by FG and LS with support from SR, MGZ, KM, and GP. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and approved it.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Attilio, C., Lorenzo, A., Valentina, Q., Roberto, C., and Enza, C. (2018). Psychoneuroendocrineimmunology (PNEI) and longevity. Healthy Aging Res. 7:12. doi: 10.12715/har.2018.7.12

Beresford, T. P., Alfers, J., Mangum, L., Clapp, L., and Martin, B. (2006). Cancer survival probability as a function of ego defense (adaptive) mechanisms versus depressive symptoms. Psychosomatics 47, 247–253. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.3.247

Butow, P. N., Hiller, J. E., Price, M. A., Thackway, S. V., Kricker, A., and Tennant, C. C. (2000). Epidemiological evidence for a relationship between life events, coping style, and personality factors in the development of breast cancer. J. Psychosom. Res. 49, 169–181. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00156-2

Chida, Y., Hamer, M., Wardle, J., and Steptoe, A. (2008). Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 5, 466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134

Coker, D. J., Koh, C. E., Steffens, D., Alchin, L., and Solomon, M. J. (2020). The affect of personality traits and decision-making style on postoperative quality of life and distress in patients undergoing pelvic exenteration. Colorect. Dis. 22, 1139–1146. doi: 10.1111/codi.15036

Di Giuseppe, M., Ciacchini, R., Micheloni, T., Bertolucci, I., Marchi, L., and Conversano, C. (2018). Defense mechanisms in cancer patients: a systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 115, 76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.10.016

Dixon-Gordon, K. L., Whalen, D. J., Layden, B. K., and Chapman, A. L. (2015). A systematic review of personality disorders and health outcomes. Can. Psychol. 56, 168–190. doi: 10.1037/cap0000024

Dong, X. Y., and Jin, J. (2018). Personality risk factors of occurrence of female breast cancer: a case-control study in China. Psychol. Health Med. 23, 1239–1249. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2018.1467022

Drageset, S., and Lindstrøm, T. C. (2003). The mental health of women with suspected breast cancer: the relationship between social support, anxiety, coping and defence in maintaining mental health. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 10, 401–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00618.x

Furlan, A. D., Pennick, V., Bombardier, C., van Tulder, M., and Editorial Board Cochrane Back Review Group (2009). 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine 34, 1929–1941. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1c99f

Galli, F., and Pravettoni, G. (2020). Burning mouth syndrome - opening the door to a psychosomatic approach in the era of patient-centered medicine. JAMA Otolaryngol. 146, 569–570. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0524

Galli, F., Tanzilli, A., Simonelli, A., Tassorelli, C., Sances, G., Parolin, M., et al. (2019). Personality and personality disorders in medication-overuse headache: a controlled study by SWAP-200. Pain Res. Manag. 12:1874078. doi: 10.1155/2019/1874078

Glavić, Z., Galić, S., and Krip, M. (2014). Quality of life and personality traits in patients with colorectal cancer. Psychiatr. Danub. 26, 172–180.

Gorini, A., Mazzocco, K., Gandini, S., Munzone, E., McVie, G., and Pravettoni, G. (2015). Development and psychometric testing of a breast cancer patient-profiling questionnaire. Breast Cancer 7, 133–146. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S80014

Greer, S., Morris, T., and Pettingale, K. W. (1979). Psychological response to breast cancer: effect on outcome. Lancet 2, 785–787. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(79)92127-5

Greer, S., and Watson, M. (1985). Towards a psychobiological model of cancer: psychological considerations. Soc. Sci. Med. 20, 773–777. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90330-2

Grimes, D. A., and Schulz, K. F. (2002). An overview of clinical research: the lay of the land. Lancet 359, 57–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07283-5

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 39, 281–291. doi: 10.1017/S0048577201393198

Grov, E. K., and Dahl, A. A. (2020). Is neuroticism relevant for old cancer survivors? A controlled, population-based study (the Norwegian HUNT-3 survey). Supp. Care Canc. 29, 3623–32. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05870-7

Higgins, J. P. T., and Green, S. (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011. Available online at: www.handbook.cochrane.org (accessed February 2, 2020).

Huanga, J., Caia, Y., Sua, Y., Zhanga, M., Shia, Y., Zhua, N., et al. (2021). Gastrointestinal symptoms during depressive episodes in 3256 patients with major depressive disorders: findings from the NSSD. J. Aff. Dis. 286, 27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.039

Husson, O., Vissers, P. A., Denollet, J., and Mols, F. (2015). The role of personality in the course of health-related quality of life and disease-specific health status among colorectal cancer survivors: a prospective population-based study from the PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol. 54, 669–677. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.996663

Hyphantis, T., Paika, V., Almyroudi, A., Kampletsas, E. O., and Pavlidis, N. (2011). Personality variables as predictors of early non-metastatic colorectal cancer patients' psychological distress and health-related quality of life: a one-year prospective study. J. Psychosom. Res. 70, 411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.011

Jokela, M., Batty, G. D., Hintsa, T., Elovainio, M., Hakulinen, C., and Kivimäki, M. (2014). Is personality associated with cancer incidence and mortality? An individual-participant meta-analysis of 2156 incident cancer cases among 42,843 men and women. Br. J. Cancer. 110, 1820–1824. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.58

Kavan, M. G., Engdahl, B. E., and Kay, S. (1995). Colon cancer: personality factors predictive of onset and stage of presentation. J. Psychosom. Res. 39, 1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00523-4

Keum, N., and Giovannucci, E. (2019). Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 713–732. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0189-8

Kikuchi, N., Nishiyama, T., Sawada, T., Tamakoshi, A., and Kikuchi, S. (2017). Perceived stress and colorectal cancer incidence: the Japan collaborative cohort study. Sci. Rep. 7:40363. doi: 10.1038/srep40363

Kite, M. E., and Whitley, B. E. Jr. (2016). Psychology of Prejudice and Discrimination: 3rd Edition. 1st Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kondylakis, H., Bucur, A., Crico, C., Dong, F., Graf, N., Hoffman, S., et al. (2020). Patient empowerment for cancer patients through a novel ICT infrastructure. J. Biomed. Inform. 101:103342. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103342

Kondylakis, H., Bucur, A., Dong, F., Renzi, C., Manfrinati, A., Graf, N., et al. (2017). “iManageCancer: developing a platform for Empowering patients and strengthening self-management in cancer diseases,” in 2017 IEEE 30th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS) (IEEE), 755–760.

Kreitler, S., Kreitler, M. M., Len, A., Alkalay, Y., and Barak, F. (2008). Psychological risk factors for colorectal cancer? Psychooncologie 2, 131–145. doi: 10.1007/s11839-008-0094-9

Kroenke, C. H., Bennett, G. G., Fuchs, C., Giovannucci, E., Kawachi, I., Schernhammer, E., et al. (2005). Depressive symptoms and prospective incidence of colorectal cancer in women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 162, 839–848. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi302

Kune, G. A., Kune, S., Watson, L. F., and Bahnson, C. B. (1991). Personality as a risk factor in large bowel cancer: data from the Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study. Psychol. Med. 21, 29–41. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700014628

Lemogne, C., Consoli, S. M., Geoffroy-Perez, B., Coeuret-Pellicer, M., Nabi, H., Melchior, M., et al. (2013). Personality and the risk of cancer: a 16-year follow-up study of the GAZEL cohort. Psychosom. Med. 75, 262–271. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828b5366

Lingiardi, V., and McWilliams, N. (2017). Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual-2nd ed. Personality Syndromes. London: The Guilford Press.

Lloyd, S., Baraghoshi, D., Tao, R., Samadder, N. J., and Hashibe, M. (2019). Mental health disorders are more common in colorectal cancer survivors and associated with decreased overall survival. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. Cancer Clin. Trials 42, 355–362. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000529

Lutgendorf, S. K., and Sood, A. K. (2011). Biobehavioral factors and cancer progression: physiological pathways and mechanisms. Psychosom. Med. 73, 724–730. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318235be76

Mancini, S., Alboni, S., Mattei, G., Rioli, G., Sena, P., Marchi, M., et al. (2020). Preliminary results of a multidisciplinary Italian study adopting a psycho-neuro-endocrine-immunological (PNEI) approach to the study of colorectal adenomas. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parmensis 92:e2021014. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92i1.10197

Mills, J. S., Weinheimer, L., Polivy, J., and Herman, C. P. (2018). Are there different types of dieters? A review of personality and dietary restraint. Appetite 125, 380–400. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.014

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). PRISMA group, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Int. Med. 151, 264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Mols, F., Denollet, J., Kaptein, A. A., Reemst, P. H., and Thong, M. S. (2012a). The association between Type D personality and illness perceptions in colorectal cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. J. Psychosom. Res. 73, 232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.07.004

Mols, F., Thong, M. S. Y., de Poll-Franse, L. V. V., Roukema, J. A., and Denollet, J. (2012b). Type D (distressed) personality is associated with poor quality of life and mental health among 3080 cancer survivors. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.034

Murphy, N., Moreno, V., Hughes, D. J., Vodicka, L., Vodicka, P., Aglago, E., et al. (2019). Lifestyle and dietary environmental factors in colorectal cancer susceptibility. Mol. Aspects Med. 69, 2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2019.06.005

Nagano, J., Kono, S., Toyomura, K., Mizoue, T., Yin, G., Mibu, R., et al. (2008). Personality and colorectal cancer: the Fukuoka colorectal cancer study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 553–561. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn067

Nakaya, N., Bidstrup, P. E., Saito-Nakaya, K., Frederiksen, K., Koskenvuo, M., Pukkala, E., et al. (2010). Personality traits and cancer risk and survival based on Finnish and Swedish registry data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 172, 377–385. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq046

Nakaya, N., Tsubono, Y., Hosokawa, T., Nishino, Y., Ohkubo, T., Hozawa, A., et al. (2003). Personality and the risk of cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 95, 799–805. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.11.799

Neeleman, J., Bijl, R., and Ormel, J. (2004). Neuroticism, a central link between somatic and psychiatric morbidity: path analysis of prospective data. Psychol. Med. 34, 521–531. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001193

Oliveri, S., Scotto, L., Ongaro, G., Triberti, S., Guiddi, P., and Pravettoni, G. (2019). “You do not get cancer by chance”: communicating the role of environmental causes in cancer diseases and the risk of a “guilt rhetoric”. Psychooncology 28, 2422–2424. doi: 10.1002/pon.5224

O'Súilleabháin, P. S., Turiano, N. A., Gerstorf, D., Luchetti, M., Gallagher, S., Sesker, A. A., et al. (2021). Personality pathways to mortality: Interleukin-6 links conscientiousness to mortality risk. Brain Behav. Immun. 93, 238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.01.032

Otegbeye, E. E., Fritz, C. D. L., Liao, J., Smith, R. K., and Cao, Y. (2021). Behavioral risk factors and risk of early-onset colorectal cancer: review of the mechanistic and observational evidence. Curr. Colorectal Cancer Rep. 17, 43–45. doi: 10.1007/s11888-021-00465-8

Paika, V., Almyroudi, A., Tomenson, B., Creed, F., Kampletsas, E. O, Siafaka, V., et al. (2010). Personality variables are associated with colorectal cancer patients' quality of life independent of psychological distress and disease severity. Psychooncology 19, 273–282. doi: 10.1002/pon.1563

Perry, J. C., Metzger, J., and Sigal, J. J. (2015). Defensive functioning among women with breast cancer and matched community controls. Psychiatry 78, 156–169. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2015.1051445

Ristvedt, S. L., and Trinkaus, K. M. (2005). Psychological factors related to delay in consultation for cancer symptoms. Psychooncology 14, 339–350. doi: 10.1002/pon.850

Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., and Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: the comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2, 313–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x

Schoormans, D., Husson, O., Denollet, J., and Mols, F. (2017). Is Type D personality a risk factor for all-cause mortality? A prospective population-based study among 2625 colorectal cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. J. Psychosom. Res. 96, 76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.03.004

Shun, S. C., Hsiao, F. H., Lai, Y. H., Liang, J. T., Yeh, K. H., and Huang, J. (2011). Personality trait and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 38, E221–E228. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E221-E228

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., et al. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71, 209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

Sutin, A. R., Ferrucci, L., Zonderman, A. B., and Terracciano, A. (2019). Personality and obesity across the adult life span. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 579–592. doi: 10.1037/a0024286

Temoshok, L. (1987). Personality, coping style, emotion and cancer: towards an integrative model. Cancer Surv. 6, 545–567.

Wellisch, D. K., and Yager, J. (1983). Is there a cancer-prone personality? CA Cancer J. Clin. 33, 145–153. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.33.3.145

Wells, G. A., Shea, B., O'Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., et al. (2014). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Appl. Eng. Agric. 18, 727–734.

White, V. M., English, D. R., Coates, H., Lagerlund, M., Borland, R., and Giles, G. G. (2007). Is cancer risk associated with anger control and negative affect? Findings from a prospective cohort study. Psychosom. Med. 69, 667–674. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31814d4e6a

Keywords: colorectal cancer, cancer risk, personality, character, behavior, cancer incidence, cancer onset

Citation: Galli F, Scotto L, Ravenda S, Zampino MG, Pravettoni G and Mazzocco K (2021) Personality Factors in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 12:590320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.590320

Received: 01 August 2020; Accepted: 06 October 2021;

Published: 03 November 2021.

Edited by:

Lesley L. Verhofstadt, Ghent University, BelgiumReviewed by:

Mariagrazia Di Giuseppe, University of Pisa, ItalyErika Limoncin, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy

Marieke Van Schoors, Ghent University, Belgium

Copyright © 2021 Galli, Scotto, Ravenda, Zampino, Pravettoni and Mazzocco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ketti Mazzocco, a2V0dGkubWF6em9jY29AdW5pbWkuaXQ=

†These authors share last authorship

Federica Galli

Federica Galli Ludovica Scotto

Ludovica Scotto Simona Ravenda3

Simona Ravenda3 Ketti Mazzocco

Ketti Mazzocco