- 1Faculty of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

- 2School of Foreign Languages, Southwest University, Chongqing, China

In this study, we examined family support and friend support as potential mediators between psychological suzhi and suicide ideation in a sample of 1,369 Chinese adolescents (48. 1% men, 15.52 ± 1.76 years). The results showed that family support and friend support were found to adequately mediate the relationship between psychological suzhi and suicide ideation. In addition, the effect of psychological suzhi on adolescents' suicide ideation was stronger for family support than friend support. These findings demonstrated the key roles of psychological suzhi, family support, and friend support in reducing adolescents' suicide ideation. It enlightens us that we are supposed to improve adolescents' psychological suzhi and perceived social support (including family support and friend support) through many ways in order to better play its protective role in the future.

Introduction

The 1990–2016 Global Suicide Disease Burden Analysis Report pointed out that, overall, ~800,000 people die of suicide every year in the world. Although the age-standardized death rate of suicide has dropped by 32.7% over the past 20 years, the phenomenon of suicide among teenagers has increased. It has become more and more common and has become a major global public health problem. Suicide has become the second leading cause of death among adolescents worldwide. Especially in the past 10 years, the suicide rate among people aged 10–14 years has almost tripled (Curtin and Heron, 2019); the rate of suicide among Chinese adolescents also did not decrease significantly (Liu Z. R. et al., 2017). Studies have pointed out that an individual's suicide will not only harm themselves and cause great grief to the family, but also induce friends or family members to increase suicide ideation or engage in suicidal behavior, which will have a great negative impact on society (Nanayakkara et al., 2013). Suicidal behavior includes suicide ideation, nonfatal suicide attempts, and fatal suicide (Silverman et al., 2007). Among them, suicide ideation refers to the loss of the desire to live, the start of thinking about plans and ways of suicide, and the notion and behavior that have not caused physical injury for the time being (Beck et al., 1973). From the perspective of suicide formation process, suicide ideation is the main link and inevitable stage of suicidal behavior, and it is also the most sensitive predictor (Miranda et al., 2014; Ni and Chen, 2016). Therefore, it is of great significance for the prevention and intervention of suicidal behavior of teenagers to find out the protective factors that influence suicide ideation and further reveal its influencing mechanism.

The stress-susceptibility model of suicide believes that suicide is a process jointly affected by stress factors (stress events), environmental factors (including family, social, cultural, and other factors), and individual qualities (including susceptibility, personality, cognition, etc.). The protective factors affecting suicidal behavior of adolescents mainly involve resilience, social support, and positive coping styles (Mann and John, 2002). Although there are abundant researches on the factors affecting suicide ideation, there is no research to examine if psychological suzhi affects the suicide ideation of adolescents during middle-school stage, or aiming at identifying a mechanism underlying such an effect (Johnson et al., 2010; Kristin and Sean, 2011; Evan et al., 2013). Therefore, this research aims to investigate the influence of middle-school students' psychological suzhi on suicide ideation from the perspective of psychological suzhi.

Psychological suzhi is a psychological concept with Chinese characteristics. It was first proposed under the background of Chinese vigorous promotion of quality education in the 1980s. Based on theoretical and empirical studies among Chinese students in the past 30 years, we defined it as a basic psychological quality. It has a derivative function related with individuals' developmental, adaptive, and creative behaviors and a multilevel self-organized system that involves steady implicit mental qualities and explicit adaptive behaviors (Zhang et al., 2011; Nie et al., 2020a). The psychological suzhi structure is based on the two-factor model, including general factors and special factors. The former highlights the basic characteristics of psychological suzhi and participates in all aspects of mental activities; the latter is specifically composed of three dimensions: cognitive quality, personality quality, and adaptation (Wu et al., 2017). Cognitive quality is the most basic component in the structure of psychological suzhi, which mainly refers to the mental quality of individuals when reflecting objective things, involving specific operations such as perception. Personality quality is the core of the structure of psychological suzhi, which reflects the individuals' personality psychology. Although it does not directly participate in the specific operations of cognition, it has motivation and regulation functions for the cognitive process. Adaptation mainly reflects the derivative function of psychological suzhi. It reflects the individuals' ability to continuously adapt to environmental changes during the process of interaction with the environment and to coordinate itself with the environment. It is a comprehensive manifestation of the integration of cognitive and individual factors into the individuals' external behavior (Nie et al., 2020b).

At present, the psychological factors concerned by suicide research mainly focus on variables such as self-esteem, depression, and hope, and there are few studies from the perspective of psychological suzhi. For a long time, depression has been regarded as an important risk factor for suicide. A large number of studies have shown that depression can significantly predict individual suicide ideation (Bradvik et al., 2008; Troister and Holden, 2013). At the same time, cognitive theory believes that the appearance of psychological feelings such as depression, loneliness, and suicide ideation is inseparable from self-knowledge (Beck, 1967). People with low self-esteem have insufficient problem-solving skills, and they are prone to extreme, absolute, and one-way judgments when encountering setbacks, which can lead to suicide ideation (Jibeen, 2017). In addition, studies have shown that the sense of hope is not only an effective negative predictor of suicide ideation, but also plays a significant role in regulating ruminant thinking and suicide ideation (O'Keefe and Wingate, 2013; Tucker et al., 2013), which means that hope can reduce the possibility of suicide ideation. Although no research has directly investigated the relationship between psychological suzhi and suicide ideation, many empirical studies have shown that adolescents' psychological suzhi can significantly positively affect self-esteem and hope (Liu G. Z. et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2020) and significantly negatively affect negative emotions such as depression and anxiety (Zhang et al., 2017). Therefore, we speculate that compared to specific mental health indicators such as self-esteem, depression, and hope, psychological suzhi as a comprehensive quality may play a more basic role, but the specific impact mechanism still needs to be further explored.

Perceived social support is the degree of emotional satisfaction that an individual feels subjectively supported and understood (Sarason et al., 1991). The buffer model of social support points out that social support can alleviate the negative effects of negative events and improve the individuals' physical and mental health (Cohen and Wills, 1985). Perceived social support and actual social support are not exactly the same. The former is psychological reality, and the latter is social reality. However, psychological reality is often more able to influence individuals' psychology and behavior; that is, perceived social support is also a potentially important protective factor (Brenning et al., 2015). There are abundant studies on perceived social support and suicide ideation. Some studies have found that compared with economic pressure and psychological resilience, perceived social support has a more significant influence on suicide ideation of adolescents (Lee et al., 2017), and other studies have pointed out that when adolescents have a higher level of perceived social support, it can significantly reduce the negative impact of bullying and reduce the possibility of suicidal ideation (Liu X. Q. et al., 2017). From the specific sources of social support, studies have pointed out that various family factors are risk factors for suicide among teenagers. Family function and parental warmth will have a significant impact on teenagers' suicide ideation (Sylvia, 2011; Li et al., 2016a). Some studies have also pointed out that after controlling for family structure and parental attachment, perceived peer support still has a strong predictive effect on suicide ideation (Li et al., 2016b). Perceived social support itself includes family support, friend support, and other support. Existing studies when investigating the relationship between social support and suicide ideation all consider social support as a whole or examining one aspect of support separately. Few studies examine the effects of family support and friend support separately, but this study aims to compare the two that have more significant effects. Therefore, we speculate that family support and friend support may simultaneously affect adolescents' suicide ideation, but we do not make assumptions about the specific impact mechanism.

Psychological suzhi and perceived social support are the potential factors affecting suicide ideation in adolescents, and there is also a close relation between them. The model of the relationship between psychological suzhi and mental health points out that psychological suzhi will affect the perception of external protective factors (such as social support), thereby affecting the individual's mental health (Zhang and Wang, 2012). As a core and basic psychological quality of adolescents, psychological suzhi has been shown to positively predict perceived social support, and can negatively influence social anxiety through the chain-like mediation of self-esteem and perceived social support (Zhang and Zhang, 2019). In other words, individuals with higher psychological suzhi have a higher level of perceived social support, and psychological suzhi can enhance the individual's mental health and social adaptation level by enhancing the perceived social support. And because it is mentioned above that perceived social support can significantly negatively affect adolescents' suicide ideation, we speculate that perceived social support may play a mediating role in the relationship between adolescents' psychological suzhi and suicide ideation.

In summary, this research will explore the relationship between psychological suzhi, perceived social support (family support, friend support), and suicide ideation in Chinese adolescents for the first time and subsequently attempt to examine internal mechanisms that account for these associations. Thus, we hypothesized that:

H1: Psychological suzhi is negatively related to suicide ideation.

H2: Psychological suzhi is positively related to friend support and family support.

H3: Friend support and family support would mediate the association between psychological suzhi and suicide ideation.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants included 1,369 students recruited from six compulsory secondary education schools in eastern, central, and western China. We randomly selected 30 classes from 7th to 12th grade at six schools (272, 197, 204, 213, 284, and 199 participants, respectively). No significant differences were found in other demographic variables such as gender among schools, so these participants had a good sample representation. Two hundred thirty-six participants were in 7th grade, 211 were in 8th grade, 232 were in 9th grade, 237 were in 10th grade, 222 were in 11th grade, and 231 were in 12th grade. There were 658 (48.1%) boys and 711 (51.9%) girls. Participants were aged 11 to 20 years (mean = 15.52 ± 1.76 years).

The Research Ethics Committee of Chinese Southwest University approved this study. Before the start of the research, we contacted the administrators of the relevant schools, obtained permission for the questionnaire test, and obtained informed consent from the students and parents at the parents' meeting. At the beginning of the test, the researcher introduced the research objectives and procedures to the participants. Then, the participants filled out the questionnaire under the supervision of the researcher and completed it within the specified time. All participants were tested during regular school hours in their classrooms.

Measures

Psychological Suzhi

Psychological suzhi was measured by the Psychological Suzhi Questionnaire for Middle School Students (Hu et al., 2017). This scale contains 24 items. It measures psychological suzhi from three dimensions including cognitive quality (e.g., “I always have explicit pathways when doing exercises”), individuality (e.g., “I always press myself to complete what I should do”), and adaptability (e.g., “I am a popular person”). Please see full details of the questionnaire in the Supplementary Materials. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree), with higher scores indicating greater psychological suzhi. In this study, Cronbach α of the total scale was 0.92 and ranged from 0.79 to 0.84 for the subscales.

Perceived Social Support

Perceived social support was measured by the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet et al., 1988). This scale contains 12 items, which were answered using a 7-point rating scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater perceived social support. It measures perceived support from three aspects including family, friends, and significant others. This scale is suitable for use with adolescents in the Chinese school environment, and the reliability of the whole scale is excellent (Chen et al., 2016). For research purposes, this study selected only eight items to evaluate family support and friend support and scored the two parts separately. In this study, Cronbach α values of family support and friend support were 0.83 and 0.86, respectively.

Suicide Ideation

Suicide ideation was measured by the Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation (PANSI; Osman et al., 1998). This scale contained a six-item subscale of positive suicide ideation and an eight-item subscale of negative suicide ideation. Positive suicide ideation was scored in reverse, and the total score of negative suicide ideation was added to obtain the total score of suicide ideation. Higher scores on the PANSI indicate stronger suicide ideation. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = none of the time, 5 = most of the time). PANSI has been shown to have high reliability and validity in the Chinese school environment (Wang et al., 2011). Cronbach α values of positive suicide ideation and negative suicide ideation were 0.82 and 0.93 respectively, and 0.89 for the total scale in this study.

Analytic Strategy

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 24.0 and Mplus 7. First, descriptive analysis was conducted to calculate the mean and standard deviation for each variable. Next, correlational analyses were conducted to examine whether psychological suzhi was associated with the friend support, family support, and suicide ideation in the expected directions. And then, the measurement model's goodness of fit was evaluated. The following indexes were used to assess goodness of fit for the measurement model: comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI and TLI values of ≥0.90, SRMR values of ≤0.08, and RMSEA values of ≤0.08 indicated good model fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999). Finally, multiple mediation analyses were conducted to examine the mediating roles of family support and friend support in the relationship between psychological suzhi and suicide ideation by using SEM. Following existing studies, age and gender were included as control variables. In this study, we obtained 5,000 bootstrap resamples and used them to determine the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the indirect effects. If the CI did not include zero, then the indirect effect was significant at p = 0.05 (Preacher and Hayes, 2008).

Results

Descriptive Statistics Among the Variables

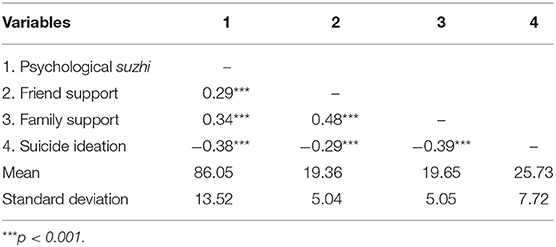

Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations, and the correlations between psychological suzhi, friend support, family support, and suicide ideation. Psychological suzhi was significantly positively correlated with friend support and family support. Both of them were significantly negatively correlated with suicide ideation.

Mediation Analysis

As two potential parallel mediators, friend support and family support were entered into a mediation model to examine whether they mediated the link between psychological suzhi and suicide ideation in Chinese adolescents. The test of the hypothesized mediator model showed a good date fit (χ2 = 863.45, df = 84; CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.07).

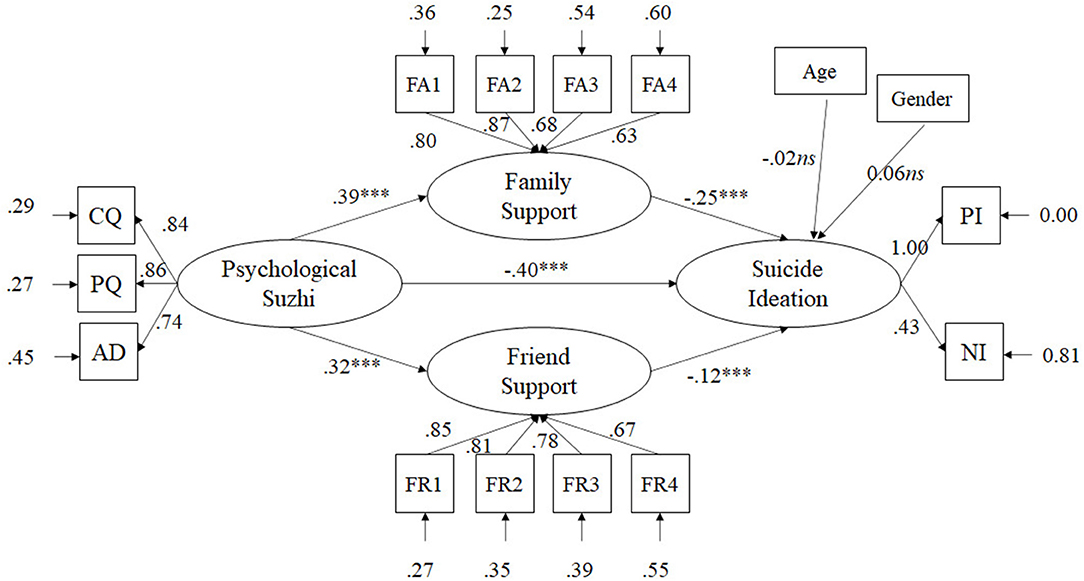

The standardized path coefficients among the main variables are presented in Figure 1. Psychological suzhi significantly related to suicide ideation (β = −0.40), supporting Hypothesis 1. The path coefficients between psychological suzhi and friend support (β = 0.32) and family support (β = 0.39) were both significant, supporting Hypothesis 2. Moreover, paths to suicide ideation from friend support (β = −0.12) and family support (β = −0.25) were both significant in the predicted directions. Therefore, friend support and family support mediated the association between psychological suzhi and suicide ideation; Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Figure 1. Structural equation model with standardized parameters estimates: psychological suzhi and suicide ideation. CQ, cognitive quality; PQ, personality quality; AD, adaptability; FR, friend support; FR1–FR4, four parcels of friend support; FA, family support; FA1–FA4, four parcels of family support. ***p < 0.001.

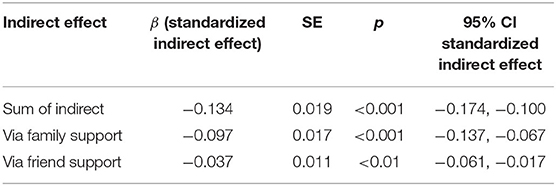

We subsequently used model constraint command of Mplus to create auxiliary variables and used bootstrapping in order to compare the mediation effects (Table 2). Psychological suzhi's indirect correlation with suicide ideation was significantly stronger via family support than via friend support [β = −0.074, SE = 0.028, p < 0.01, 95% CI = (−0.025, −0.137)].

Discussion

In this research, we examined the relations of psychological suzhi and suicide ideation with the effect of family support and friend support as mediators. Our study findings showed that adolescents' psychological suzhi, family support, and friend support were significantly positively correlated with each other, and the three were significantly negatively linked with suicide ideation, which supports our Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. Consistent with prior research, whether it was objective social support or perceived social support, psychological suzhi had a good predictive effect (Zhang and Zhang, 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Additionally, prior studies showed that perceived social support (including family support and friend support) could significantly negatively predict individuals' problem behaviors or even suicide ideation (Pace and Zappulla, 2013; Corbitt-Hall et al., 2018). Although there has not been any research investigating the relationship between psychological suzhi and suicide ideation, a follow-up study on Chinese adolescents found that students' psychological suzhi had a positive effect on individuals' depression, loneliness, and friendship quality (Zhang et al., 2017). These above variables were closely related to the individual's suicide ideation. Therefore, as the core element of mental health (Liu G. Z. et al., 2017), psychological suzhi could also effectively predict individuals' suicide ideation. This result suggests that improving adolescents' psychological suzhi may make them feel more support from family and friends and show a lower level of suicide ideation.

Regarding our third hypothesis, we found that psychological suzhi could affect individuals' suicide ideation through parallel mediation effect of family support and friend support by our model. That is to say, high level of psychological suzhi not only could directly reduce the individuals' suicide ideation, but also could be achieved by enhancing the individuals' perception of support from family and friends. This result supported the notion that family support and friend support had an essential part in the study life of Chinese students, which were consistent with previous studies (Rehman et al., 2020). It reveals that the mental health of adolescents is inseparable from the support and help of family and friends. At the same time, it is also vital to improve their psychological suzhi so that they can better perceive the support of others.

Moreover, we further compared the impact of family support and friend support, and the result showed that family support and friend support partially mediated psychological suzhi's effect on suicide ideation, and the indirect effect was significant stronger via family support than via friend support. However, a study on migrant children in China showed that active friend support had an important protective effect on the individual's emotional and behavioral adaptation, while the protective effect of family support is only reflected in the field of behavioral adaptation (Wang et al., 2018). According to Poulin et al. (2012), in the background of Chinese culture, family support has a greater impact on the individuals' physical and mental health than friend support, but in Western countries, the result is the opposite. A possible explanation for this result is that teenagers are mainly in school life, and the connection between peer relationship and the daily emotional changes of adolescents is closer, but the parental rearing styles, behavior, and attitude toward their children have more important influence on serious problem behaviors such as suicide and crime. This is backed up by some studies. For example, family parenting had a significant impact on the personality traits in juvenile delinquents, and peer relationship only played a moderating role in some ways (Peng et al., 2013). Other studies pointed out that when it comes to stable and long-lasting emotions such as subjective well-being, compared with friend support, the predictive effect of the individuals' own behavior is more obvious (Traylor et al., 2016).

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations of this research should also be noted, which can provide some suggestions and guidance for future research. First, we used a cross-sectional design to test our hypotheses, thereby the current results are preliminary, and we try to use longitudinal or experimental design in the future. Second, this study was conducted in Chinese students; the cultural discrepancies may result in different consequences. Future research can further compare the results under different cultures. Finally, perceived social support may not be consistent with the actual social support, and comparing their impact is also a meaningful topic.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study investigates how adolescents' psychological suzhi influences suicide ideation. Specifically, we found that adolescents' psychological suzhi is negatively related to suicide ideation, and family support and friend support partially mediate this effect. Meanwhile, compared with friend support, family support plays a more important role in reducing adolescents' suicide ideation.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Southwest University approved the study. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

On the basis of reading the relevant literature, ZZ put forward the research questions and the solution, and assisted in study design, data collection, and writing work. At the same time, according to the teachers' and cooperative researchers' recommendations and comments have been amended to formally form the final submission manuscript. DZ was mainly responsible for the supervision and guidance of the entire research process and providing financial support. WT and GL were mainly responsible for modifying and providing guidance to this paper, played an important role in the successful writing of the paper. All of the authors participated in the final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research has been supported by the Theoretical Innovative Research of Guizhou province (GZLCLH-2020-324).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in this study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.632274/full#supplementary-material

References

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression Clinical, Experimental and Theoretical Aspects. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Beck, A. T., Davis, J. H., Frederick, C. J., Perlin, S., Pokorny, A. D., Schulman, R. E., et al. (1973). “Classification and nomenclature,” in Suicide Prevention in the Seventies, eds H. L. P. Resnick, and B. C. Hathorne (Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office).

Bradvik, L., Mattisson, C., Bogren, M., and Nettelbladt, P. (2008). Long-term suicide risk of depression in the Lundby cohort 1947-1997—severity and gender. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 117, 185–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01136.x

Brenning, K., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., and Vansteenkiste, M. (2015). Perceived maternal autonomy support and early adolescent emotion regulation: a longitudinal study. Soc. Dev. 24, 561–578. doi: 10.1111/sode.12107

Chen, W., Lu, C., Yang, X. X., and Zhang, J. F. (2016). A multivariate generalizability analysis of perceived social support scale. Psychol. Explor. 36, 75–78. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-5184.2016.01.014

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Corbitt-Hall, D. J., Gauthier, J. M., and Troop-Gordon, W. (2018). Suicidality disclosed online: using a simulated facebook task to identify predictors of support giving to friends at risk of self-harm. Suicide Life Threat. 49, 598–613. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12461

Curtin, S. C., and Heron, M. (2019). Death Rates Due to Suicide and Homicide Among Persons Aged 10-24: United States, 2000-2017. NCHS Data Brief, no. 352. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Evan, M., Kleiman, John, H., and Riskind (2013). Utilized social support and self-esteem mediate the relationship between perceived social support and suicide ideation: a test of a multiple mediator model. Crisis 34, 42–49. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000159

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, T. Q., Zhang, D. J., and Cheng, G. (2017). Revision of the psychological suzhi questionnaire of the middle school students (simplified version) and the test of the reliability and validity. J. Southwest Univ. 10, 120–126. doi: 10.13718/j.cnki.xdsk.2017.02.015

Jibeen, T. (2017). Unconditional self acceptance and self esteem in relation to frustration intolerance beliefs and psychological distress. J. Ration Emot. Cogn. B Therapy 35, 207–221. doi: 10.1007/s10942-016-0251-1

Johnson, J., Gooding, P. A., Wood, A. M., and Tarrier, N. (2010). Resilience as positive coping appraisals: testing the schematic appraisals model of suicide(sams). Behav. Res. Ther. 48, 179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.007

Kristin, C., and Sean, A. K. (2011). Resilience and suicidality among homeless youth. J. Adolesc. 34, 1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.003

Lee, Y., Pak, S. Y., and Kim, M. J. (2017). Economic stress, depression, suicide ideation, resilience, and social support in college students. J. Kor. Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 26, 151–162. doi: 10.12934/jkpmhn.2017.26.2.151

Li, D. P., Bao, Z. Z., Li, X., and Wang, Y. H. (2016a). Perceived school climate and Chinese adolescents' suicide ideation and suicide attempts: the mediating role of sleep quality. J. School Health 86, 75–83. doi: 10.1111/josh.12354

Li, D. P., Li, X., Wang, Y. H., and Bao, Z. Z. (2016b). Parenting and Chinese adolescent suicide ideation and suicide attempts: the mediating role of hopelessness. J. Child Fam. Stud. 25, 1397–1407. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0334-0

Liu, G. Z., Zhang, D. J., Pan, Y. G., Ma, Y. X., and Lu, X. Y. (2017). The effect of psychological Suzhi on problem behaviors in Chinese adolescents: the mediating role of subjective social status and self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 8:1490. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01490

Liu, X. Q., Chen, G., Hu, P., Guo, G. P., and Xiao, S. Y. (2017). Does perceived social support mediate or moderate the relationship between victimisation and suicide ideation among chinese adolescents? J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 27, 123–136. doi: 10.1017/jgc.2015.30

Liu, Z. R., Huang, Y. Q., Ma, C., Shang, L. L., Zhang, T. T., and Chen, H. G. (2017). Suicide rate trends in China from 2002 to 2015. Chin. Ment. Health J. 10, 756–767. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2017.10.003

Mann and John, J. (2002). A current perspective of suicide and attempted suicide. Ann. Intern. Med. 136, 302–311. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-4-200202190-00010

Miranda, R., Ortin, A., Scott, M., and Shaffer, D. (2014). Characteristics of suicide ideation that predict the transition to future suicide attempts in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psyc. 55, 1288–1296. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12245

Nanayakkara, S., Misch, D., Chang, L., and Henry, D. (2013). Depression and exposure to suicide predict suicide attempt. Depress. Anxiety 30, 991–996. doi: 10.1002/da.22143

Ni, R. X., and Chen, J. M. (2016). A study on the relationship between coping style and suicidal ideation in junior high students. Chin. J. Health Psychol. 24, 1402–1406. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2016.09.031

Nie, Q., Teng, Z. J., Yang, C. Y., Lu, X. Y., Liu, C. X., Zhang, D. J., et al. (2020b). Psychological suzhi and academic achievement in chinese adolescents: a 2-year longitudinal study. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. e12384. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12384

Nie, Q., Yang, C. Y., Teng, Z. J., Furlong, M. J., Pan, Y. G., Guo, C., et al. (2020a). Longitudinal association between school climate and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of psychological suzhi. School Psychol. 35, 267–276. doi: 10.1037/spq0000374

O'Keefe, V. M., and Wingate, L. R. (2013). The role of hope and optimism in suicide risk for American Indians/Alaska Natives. Suicide Life Threat 43, 621–633. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12044

Osman, A., Gutierrez, P. M., Kopper, B. A., Barrios, F. X., and Chiros, C. E. (1998). The positive and negative suicide ideation inventory: development and validation. Psychol. Rep. 82:783. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3.783

Pace, U., and Zappulla, C. (2013). Detachment from parents, problem behaviors, and the moderating role of parental support among Italian adolescents. J. Fam. Issues 34, 768–783. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12461908

Peng, X. F., Du, K. Z., Yin, G. L., and Gui, T. Y. (2020). Parental emotional warmth and children's positive and negative emotion: the continuous mediation of psychological Suzhi and hope and their differences. J. Southwest Univ. 42, 22–28. doi: 10.13718/j.cnki.xdzk.2020.02.004

Peng, Y. S., Wang, Y. L., Gong, L., and Peng, L. (2013). Relationship between parenting style and personality traits in juvenile delinquents: moderating role of peer relationship. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 21, 956–958. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2013.06.006

Poulin, J., Deng, R., Ingersoll, T. S., Witt, H., and Swain, M. (2012). Perceived family and friend support and the psychological well-being of American and Chinese elderly persons. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 27, 305–317. doi: 10.1007/s10823-012-9177-y

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Rehman, A. U., Bhuttah, T. M., and You, X. (2020). Linking burnout to psychological well-being: the mediating role of social support and learning motivation. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 13, 545–554. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S250961

Sarason, B. R., Pierce, G. R., Shearin, E. N., Sarason, I. G., Waltz, J. A., and Poppe, L. (1991). Perceived social support and working models of self and actual others. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 273–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.273

Silverman, M. M., Berman, A. L., Sanddal, N. D., O'Carroll, P. W., and Joiner, T. E. (2007). Rebuilding the tower of babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors part 1: background, rationale, and methodology. Suicide Life Threat 37, 248–263. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.248

Sylvia, K. (2011). Perceived family functioning and suicide ideation. Nurs. Res. 60, 422–429. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e31823585d6

Traylor, A. C., Williams, J. D., Kenney, J. L., and Hopson, L. M. (2016). Relationships between adolescent well-being and friend support and behavior. Child Sch. 38, 179–186. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdw021

Troister, T., and Holden, R. R. (2013). Factorial differentiation among depression, hopelessness, and psychache in statistically predicting suicidality. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 46, 50–63. doi: 10.1177/0748175612451744

Tucker, R. P., Wingate, L. R., O'Keefe, V. M., Mills, A. C., Rasmussen, K., Davidson, C. L., et al. (2013). Rumination and suicide ideation: the moderating roles of hope and optimism. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 55, 606–611. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.013

Wang, H., Xiong, Y. K., and Liu, X. (2018). The protective roles of parent-child relationship and friend support on emotional and behavioral adjustment of migrant adolescents. Psychol. Dev. Edu. 34, 614–624. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2018.05.12

Wang, X. Z., Gong, H. L., Kang, X. R., Liu, W. W., Dong, X. J., and Ma, Y. F. (2011). Reliability and validity of Chinese revision of positive and negative suicide ideation in high school students. China J. Health Psychol. 19, 964–966. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2011.08.014

Wu, L. L., Zhang, D. J., and Cheng, G. (2017). Preliminary study on bifactor structure of primary and secondary students' psychological quality. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 15, 26–33. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2017.01.005

Zhang, D. J., Su, Z. Q., and Wang, X. Q. (2017). Thirty-years study on the psychological quality of chinese children and adolescents: review and prospect. Stud. Psychol. Behav. 15, 3–11. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2017.01.002

Zhang, D. J., Wang, J. L., and Yu, L. (2011). Methods and Implementary Strategies on Cultivating Students' Psychological Suzhi. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Zhang, D. J., and Wang, X. Q. (2012). An analysis of the relationship between mental health and psychological suzhi: from perspective of connotation and structure. J. Southwest Univ. 38, 69–74. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-9841.2012.03.011

Zhang, D. J., Zhu, Z. Z., Liu, G. Z., and Li, Y. (2019). The relationship between social support and problem behavior in adolescent: the chain mediating role of psychological suzhi and self-esteem. J. Southwest Univ. 45, 99–104. doi: 10.13718/j.cnki.xdsk.2019.01.012

Zhang, T., and Zhang, D. J. (2019). The relationship between middle school freshmen's psychological suzhi and social anxiety: the mediating role of self-esteem and perceived social support. J. Southwest Univ. 41, 39–45. doi: 10.13718/j.cnki.xdzk.2019.02.006

Keywords: psychological suzhi, family support, friend support, suicide ideation, adolescents

Citation: Zhu Z, Tang W, Liu G and Zhang D (2021) The Effect of Psychological Suzhi on Suicide Ideation in Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Family Support and Friend Support. Front. Psychol. 11:632274. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.632274

Received: 22 November 2020; Accepted: 30 December 2020;

Published: 11 February 2021.

Edited by:

Carolina Gonzálvez, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Rui Campos, University of Evora, PortugalMatt DeLisi, Iowa State University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Zhu, Tang, Liu and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dajun Zhang, emhhbmdkakBzd3UuZWR1LmNu

Zhengguang Zhu

Zhengguang Zhu Wenchuan Tang2

Wenchuan Tang2 Guangzeng Liu

Guangzeng Liu Dajun Zhang

Dajun Zhang