- 1School of Business Administration, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China

- 2Xingjian College of Science and Liberal Arts, Guangxi University, Nanning, China

- 3School of Management, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

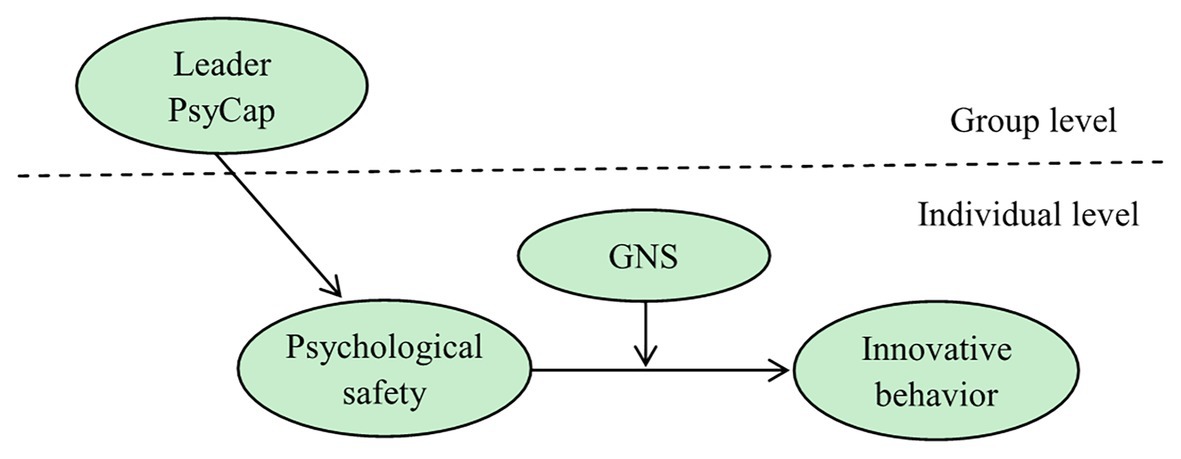

The study reported in this paper analyzed the influence of leader psychological capital (PsyCap) on employees’ innovative behavior and the roles of psychological safety and growth need strength (GNS) in this process within the context of positive psychology theory and conservation of resources theory. Three stages of questionnaire surveys were administered to 81 enterprise leaders and their 342 direct subordinates in South China to test our theoretical model. The results showed that leader PsyCap had significant and positive effects on employee innovative behavior, psychological safety had a partially mediating effect, and GNS positively moderated the relationship between psychological safety and innovative behavior. The results revealed the mechanism of PsyCap and external boundary conditions of the influence of leader PsyCap on employee innovative behavior. The study expands the research results of leader PsyCap theory and also provides guidance on how enterprises manage employees’ innovative behavior.

Introduction

Innovative behavior is effective for an organization to adapt to environmental changes and maintain its competitiveness (Devloo et al., 2014; Parahoo et al., 2017). Employee innovation plays a key role in providing continuous competitive advantage to the organization (Ghosh, 2010; Turró et al., 2014; Odoardi et al., 2015; Shin et al., 2017). Many literature concern with employee innovation, and these reviews identified that employee psychological capital has a positive effect on employee innovation (Liang and Li, 2016; Fang et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2019; Tsegaye et al., 2020), but few of these studies focus on the relationship between leader psychological capital and employee innovation (Peterson et al., 2009; Li et al., 2020). Positive psychology posits that leader psychological capital (PsyCap) is a positive psychological resource. In addition to an active attitude toward their work and high working performance, leaders with a high PsyCap level are enthusiastic at work and set an example for their followers (Walumbwa et al., 2010). The literature shows that the innovation ability of employees is influenced by their leaders (Zubair et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017; Harbi et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019), and research on how to improve employee innovation by leader psychological capital is growing (Mohamad et al., 2019). However, knowledge on the level of leader psychological capital affected employees’ innovative behavior remains ambiguous (Li et al., 2020). Therefore, this study explored the effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior in employees.

Innovative behavior, which is often associated with uncertain outcomes, is considerably risky (Janssen, 2003; Hon, 2013; Hon and Lu, 2015; Hon and Lui, 2016; Mumtaz and Parahoo, 2019). For example, an employee with creative ideas may challenge the given organizational policies, working methods, and mission (Hon, 2012), but his or her supervisor and colleagues might refuse to these creative minds to change in order to avoid insecurity and stress due to the change (Jones, 2001; Janssen, 2003). The presentation of new ideas may challenge the established way of conduct or infringe upon the vested interest of other members of the organization (Edmondson et al., 2001; Detert and Burris, 2007). Moreover, trying new ways in the workplace may end up with failure, which causes the negative view on the relevant individuals. Once risks are involved, the lack of psychological safety will prevent employees from proposing innovative ideas and more favorable methods of working (Newman et al., 2017). Employees are motivated to be innovative only when they perceive that their interpersonal relationships will remain intact after proposing an innovative project (Edmondson, 1999). Psychological safety is the perception and experience of a high level of interpersonal trust (Hu et al., 2018). Accordingly, this study hypothesized that psychological safety is an antecedent of employee innovative behavior. Leadership largely affects employees’ psychological safety (Edmondson and Lei, 2014). Empirical studies evidenced that openness of the management and a good relationship between leaders and subordinates will improve the psychological safety of the followers (Edmondson, 2004; Li et al., 2015). Leaders with high psychological capital will contribute to effective interpersonal relationship, settlement of misunderstanding and conflict, and a healthy working environment (Chen et al., 2017). When leaders exhibit positive psychological characteristics (i.e., hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and flexibility), the subordinates are likely to believe that their leaders have strong leadership and have trust in them (Norman et al., 2010), that is, the employees’ trust in their leaders is positively correlated with leader PsyCap level. Therefore, leader PsyCap may indirectly affect innovative behavior through the mediating effect of psychological safety among employees during the entire process.

Engaging in innovative behavior requires employees to consume various resources, including time, effort, and emotional labor. A study by Graen et al. argued that a high level of growth need strength (GNS) is a prerequisite for motivating employees to finish complex and challenging tasks (Graen et al., 1986). Individuals with high GNS have strong initiative, emphasize personal growth, development, and achievement, and positively respond to challenging and stimulating tasks (Chae and Choi, 2018), from which they can obtain a higher level of intrinsic motivation (Tiegs et al., 1992). The conservation of resources theory posits that individuals are highly motivated to acquire new resources and avoid resource loss because losing or owning few resources can increase pressure (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Therefore, when encountering innovative work that is highly risky and challenging, individuals with high GNS tend to consider innovation as an opportunity for personal growth, development, and resource acquisition. By contrast, those with low GNS refuse to perform innovative yet adventurous tasks in order to protect their resources. Few scholars have conducted empirical research on GNS and its relationship with innovative behavior (Li et al., 2018). This study introduced GNS as a moderator to analyze its boundary effect on the relationship between leader PsyCap and innovative behavior in employees.

On the basis of positive psychology and conservation of resources theory, this study explored the effect of leader PsyCap on employee innovative behavior, the mediating effect of psychological safety, and the moderating effect of GNS. Despite being rarely studied in academia, leader PsyCap is an essential psychological resource that can be effectively developed in an organization. Moreover, because employee innovation largely affects organizational competitive advantage, the effect of leader PsyCap on such innovation warrants further exploration. The results of this study are expected to diversify and expand leader PsyCap research and provide suggestions for managers on solving problems related to employee innovation from the perspective of leader PsyCap.

Theory and Hypotheses

Relationship Between Leader PsyCap and Employee Innovative Behavior

As a critical concept of positive psychology, psychological capital was first introduced and extended to the field of organizational management by Luthans. Psychological capital indicates the psychological state of the employees who show positive organizational behavior composed of four items such as hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism (Luthans, 2012; Wang et al., 2013), the combined initials of the four items being HERO, which displays the positive feature of core psychological capital. Moreover, as an integrated concept, these four elements illustrate that an individual has an optimistic assessment of his or her surroundings and reasonable anticipation of the possibility of success based on the reasonable evaluation of his or her own ability and resource. HERO also shows the psychological feature and behavior tendency of an individual who persists to hit the expected target when facing a difficulty (Grgens-Ekermans and Herbert, 2013). Previous literature evidence that psychological capital can forecast the positive perception, attitude, and initiative behavior such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors (Avey et al., 2011b; Newman et al., 2014). Leader PsyCap is a critical research subfield of PsyCap. Leader PsyCap refers to a psychological property that motivates leaders to develop a positive mental state, shape positive organizational behaviors, pay attention to themselves and their subordinates, and focus on helping subordinates achieve their full potential, all of which contribute to improved business performance (Jensen and Luthans, 2006). Four characteristics of leader PsyCap, namely, self-efficacy, optimism, resilience, and hope as well as the overall concept of PsyCap facilitate leadership effectiveness, creating opportunities for a team to achieve outstanding performance and other positive work outcomes (Norman et al., 2005, 2010).

Creativity is a concept closely related to innovation; the two terms can be used interchangeably in certain cases (e.g., Amabile, 1988; Martins and Terblanche, 2013; Anderson et al., 2014). It was proposed that creativity and innovation are structurally connected, which are the two consecutive periods in the process of introducing new and improved ways to the job. Hence, in order to reveal a huge innovative organization, creativity and innovation should combine together rather than separate from each other (Hon and Lui, 2016), but there is no consensus among scholars on the specific definition of the two concepts (Anderson et al., 2014). Creativity and innovation are considered to be different and correlated (e.g., Ghosh, 2015; Castañer, 2016). Creativity is referred to as a significant antecedent variable of innovation (Amabile et al., 1996; Heye, 2006; Schilling, 2008). Shilling (2006) proposed that creative thinking is the base of innovation, while innovation is the successful performance of creative thinking. Additionally, individuals with novel and unique thinking are more likely to innovate effectively (Woodman et al., 1993). According to the concept defined by Scott and Bruce (1994), our study refers to innovation to be a course of issues as employee identification, proposing new ideas and solution, and generating a new product, which concedes with a previous study that innovation is the successful performance of creative thinking (Shilling, 2006).

Employee innovative behavior occurs when employees practice their innovative ideas generated in organizational activities, including innovation, technological development, and management procedural changes (Shi, 2012). Sheppard et al. (2010) confirmed that a positive work attitude is a deciding factor affecting individual innovation. Norman et al. (2010) demonstrated that leaders with positive psychological states (i.e., confidence, optimism, hopefulness, and resilience) serve as an example for subordinates. Leaders with a higher level of psychological capital have much higher possibility and driving force for success in addition to setting a more challenging target. They are also more willing to achieve success as well as find solutions to overcome obstacles positively (Peterson et al., 2009; Avey et al., 2011a). Subordinates with high leader PsyCap had significantly enhanced problem-solving skills and creativity than those with low leader PsyCap did (Avey et al., 2011a, 2012). Meanwhile, leaders with a higher level of psychological capital show a more positive attitude toward their followers because they see more opportunity to achieve the goal and show more confidence and support to their followers (Norman et al., 2010; Story et al., 2013). In an empirical study, Zhu and Wang (2011) demonstrated that the entrepreneurs’ optimistic and flexible attitudes allow the employees to experiment with new ideas despite the probability of failure. Therefore, this study assumed that leaders with high PsyCap positively affect their employees’ innovative behavior. Accordingly, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: Leader PsyCap significantly and positively affects employee innovative behavior.

The Mediating Effect of Psychological Safety

Psychological safety is the belief among employees that they can participate in risky acts in an organization without affecting their image or status (Kahn, 1990). As a perception that one’s actions are safe, psychological safety reduces the employees’ expectation that proposing a new idea will be risky (Liang et al., 2012), enabling them to focus on improvement and find new solutions (Carmeli et al., 2014) rather than worrying about how others will react to their behavior (Frazier et al., 2017). Palanski and Vogelgesang (2011) contended that psychological safety positively predicts employees’ innovative thinking and willingness to engage in risky activities. Therefore, this study expected psychological safety to positively affect employee innovation.

Psychological safety is subject to the individuals and systems of an enterprise, wherein the effect of leaders is the most substantial (May et al., 2004). When leaders are open-minded, available, and easy-going, the employees’ psychological safety will be developed as a result. Leader PsyCap is a critical element to build up effective leader-member relation since it can enhance the charming personality of leaders (Luthans et al., 2007b). Confident leaders believe in his or her ability in the course of management and provide more support for employees (Bandura, 1997). A leader with a high level of hope can come up with various solutions in terms of different situations, attain the group goal, and earn the trust of the members (Snyder and Shorey, 2003). Optimistic team leaders hope for the best for the future; they believe that they can remove the obstacles to achieve the goal with their effort and encourage members as well (Brissette et al., 2002). Resilient leaders are accomplished in guiding members to gain a positive emotion, leading the team to go through the adverse situation and setbacks (Masten and Reed, 2002). To sum up, high PsyCap leaders play a key role in establishing a relationship of faithfulness, harmony, and mutual trust among team members, and the organizational atmosphere of equality, tolerance, and trust helps to improve the employees’ sense of psychological safety (Zeng et al., 2020). Accordingly, this study hypothesized that leader PsyCap positively affects psychological safety among employees and proposed the following hypotheses:

H2a: Leader PsyCap significantly and positively affects psychological safety.

H2b: Psychological safety significantly and positively affects innovative behavior.

H2c: Psychological safety mediates the effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior.

The Moderating Effect of GNS

GNS refers to the degree to which individuals attach importance to personal growth and development opportunities at work (Oldham and Hackman, 2010) and to a person’s motivation for personal achievement and growth as well as a desire for independent thinking and acts (Hackman and Oldham, 1980). The higher a person’s GNS level, the more he or she craves difficult challenges (Nguyen, 2019). Individuals with high GNS “want to learn new things, stretch themselves, and strive to do better in their jobs” (Shalley et al., 2009, p. 489) and are more likely to look for opportunities to expand and demonstrate their innovation (Mumtaz and Parahoo, 2019). In innovative work, GNS is an internal drive that motivates employees (Lin et al., 2016). Without such internal drive, employees are rarely motivated to continue focusing on innovative work (Liu et al., 2016).

The conservation of resources theory proposes that individuals are inclined to obtain, retain, foster, and protect their cherished resource (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Individuals with abundant resources are less likely to be affected by resource losses and can obtain resources more easily (Wheeler et al., 2012; Hobfoll et al., 2018). In the case of resource losses, individuals will endeavor to guard the existing resource by resource investment. They will also attain new resource to less net loss deprived from original resource obtained, which leads to resource gain spirals (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Halbesleben et al. (2014) defined resource as any item that can be perceived by individuals to aid for accomplishing something. Individuals will evaluate the value of resource from two aspects: one is whether a certain item possesses universal value based on the culture one is cultivated; the other is the matching level between certain items and demand of individuals. As mentioned above, psychological safety positively predicts employees’ intent to risk and creative thinking (Palanski and Vogelgesang, 2011). Consequently, psychological safety can be regarded as a kind of psychological resource matching with innovative work. In addition, growth need strength is identified to be positively related to openness to experience which is individual difference relevant to creativity (De Jong et al., 2001; George and Zhou, 2001), so growth need strength can be regarded as another psychological resource matching with innovative work. In terms of the conservation of resources theory, innovative work can be considered as a context of resource loss. This perceived resource loss will result in either withdrawal behavior of employees to protect their residual resource or employees’ deployment of residual resource to gain more new resource (Kiazad et al., 2014). High-GNS employees are internally motivated to consider innovative yet challenging work as an opportunity to acquire knowledge, pursue self-improvement, fulfill self-growth and development needs, and obtain more resources. Accordingly, if employees possess both high GNS and psychological safety, they will take the initiative to invest resources in innovation to acquire more resources. The success of innovation can enable them to obtain resources in an incremental manner (e.g., acquire more confidence or more positive evaluations from leaders and colleagues). Even if employees with high GNS make mistakes, they regard these mistakes as opportunities for learning and honing their skills. They then actively seek solutions to correct the mistakes. Employees with high GNS continually hold the perception that their self-growth and development needs are met when learning from mistakes, and they exhibit more innovative behaviors. This forms a cycle that continually creates value-added resources.

According to the conservation of resources theory, individuals with less initial resource are prone to suffering from resource loss and weaker ability to gain new resource, and employees with limited resource will take negative action to secure existing resource (Hobfoll, 2011; Xu et al., 2017; Lan et al., 2020). Due to the stress and pressure caused by resource loss, individuals endeavor to avoid resource loss (Halbesleben and Bowler, 2007; Halbesleben, 2010; Halbesleben and Wheeler, 2011). Employees with less GNS perceived that innovative work will not bring about added value in resource, but instead it will cost their resource. Even when they perceive sufficient psychological safety, these employees strive to maintain existing resources and reduce investment in innovative behavior to avoid consuming their own resources. Consequently, employees with low GNS do not or rarely exhibit innovative behavior. Regarding employees with high GNS, innovative behavior can considerably differ in employees with high and low psychological safety. By contrast, in employees with low GNS, those with high and low psychological safety rarely engage in innovation, resulting in few differences in innovation between the two groups. On the basis of the aforementioned assumptions, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H3a: GNS moderates the relationship between psychological safety and innovative behavior. That is to say, psychological safety affects innovative behavior more in employees with high GNS compared with those with low GNS.

Relevant empirical studies have suggested that the GNS level moderates employee innovation. For example, employee GNS can moderate the relationship between their opportunities for growth and innovation (Graen et al., 1986). Accordingly, this study proposed another hypothesis as follows:

H3b: GNS moderates the mediating effect between leader PsyCap and innovative behavior caused by psychological safety, that is, the mediating effect is stronger among employees with high GNS.

This study established a theoretical model summarizing the aforementioned theoretical analyses and logical inferences (Figure 1).

Materials and Methods

Research Samples and Sampling Process

To avoid common-method variance, multisource and multiwave data collection methods were integrated with paired data collection. Employees and their direct supervisors working in South China were recruited as research participants. Specifically, the researchers selected several supervisors who are alumni of a business college, students in a Master of Business Administration program, or students in a training class for top-level managers at a university in southern China. Each supervisor was asked to randomly select at least three subordinates and provide their e-mail addresses. When recording the email address, we mark every supervisor as supervisors1, supervisors2, supervisors3, and so forth. Similarly, we name every subordinate following the corresponding supervisor as subordinate1-1, subordinate1-2, subordinate1-3, etc. We match the data and assure anonymity simultaneously. In total, 96 supervisors and 418 of their direct subordinates were selected to be participants in this study. Before the investigation, the researchers sent emails to all participants, informing them about the research purpose and process and assuring them of anonymity and confidentiality. A questionnaire survey was conducted after these participants granted their consent to participate. Data were collected in three stages. In the first stage, a leader PsyCap questionnaire (Questionnaire A) was distributed to the supervisors. In the second stage, 2 to 3 months after the Questionnaire A responses were collected, a questionnaire measuring psychological safety and GNS was distributed to the subordinates (Questionnaire B). Finally, the supervisors were asked to complete a questionnaire on their subordinates’ innovative behavior (Questionnaire C) 2–3 months after the Questionnaire B responses were collected. After excluding incomplete and unmatched responses and those failing to meet the questionnaire requirements, 81 and 342 valid responses were collected from the supervisors and their subordinates, respectively. The supervisor-subordinate ratio was 1:4.22, with response rates reaching 84.4 and 81.8% for the supervisors and the subordinates, respectively.

The sample consisted of a total of 81 leaders (58.0% males; 42.0% females). Leaders with the following characteristics comprised the largest percentage proportions in the sample: 31–35 years old (39.5%), undergraduate level of education (49.4%), 8 to 10 years of work experience (39.5%), and middle managers (43.2%). There was a total of 342 subordinate participants (47.1% males; 52.9% females). Employees aged ≤25, 26–30, 31–35, 36–40, and ≥ 41 years accounted for 24.6, 35.7, 21.3, 9.6, and 8.8% of the sample, respectively. Regarding their educational attainment, 9.9, 26.9, 53.2, and 9.9% of the subordinates had a high school degree or less, a vocational college diploma, a bachelor’s degree, and a master’s degree or higher, respectively. Most employees had worked for 2–4 years (27.8%), followed by their counterparts who had worked for >10 years (24.6%), <2 years (19.0%), 5–7 years (17.0%), and 8–10 years (11.7%). Most of the subordinates (23.4%) had worked with their supervisors for less than 1 year, followed by those who had worked for 1 to 2 years (22.2%), >5 years (21.9%), 2 to 3 years (18.1%), and 3–5 years (14.3%) with their supervisors.

Variable Measurement

This study selected scales published in well-known journals to ensure their validity and reliability. A standard translation/back-translation procedure was adopted for the English scales. Leader PsyCap was measured using the 24-item scale developed by Luthans et al. (2007a) that divides leader PsyCap into four dimensions: hope, optimism, self-efficacy, and resilience (Cronbach’s α = 0.89). Psychological safety was measured using the one-dimensional scale designed by Edmondson (1999) with seven items (Cronbach’s α = 0.78). GNS was measured using the Hackman-Oldham scale (1980) including six items (Cronbach’s α = 0.84). The eight-item one-dimensional scale developed by Wang and Zhu (2012) was adopted to measure innovative behavior (Cronbach’s α = 0.82). All the items in these scales were rated using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

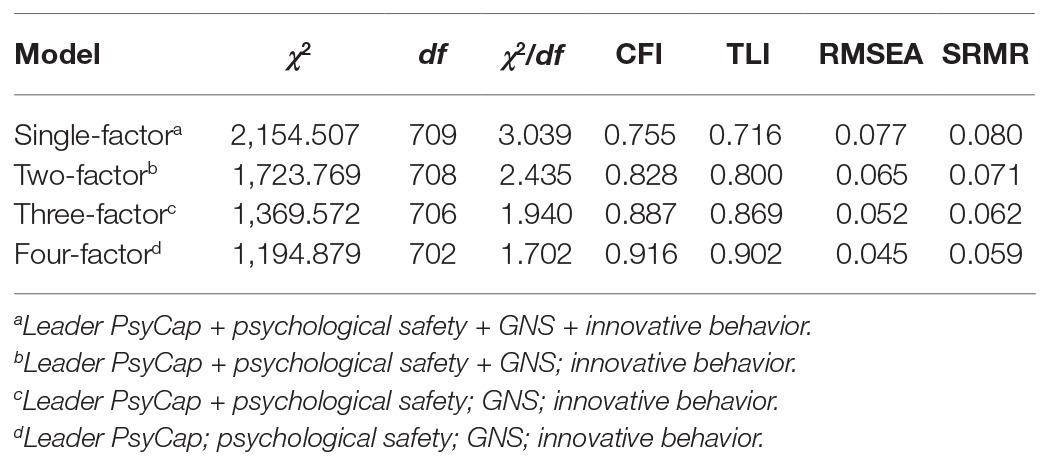

Discriminant Validity of Variables

In Harman’s single-factor test, the first unrotated factor explained 23.11% of covariance, which was less than the 40% of the threshold, indicating no serious common-method bias in the research data. Furthermore, in a confirmatory factor analysis of these data, the discriminant validity of each variable was identified using model comparison. Table 1 indicates that the four-factor model exhibited optimal fit, demonstrating desirable discriminant validity among the constructs in this study.

Strategies for Statistical Analysis

Leader PsyCap was regarded as a group-level variable in the theoretical model, whereas psychological safety, innovative behavior, and GNS were individual-level variables. The study used Mplus7.4 (Los Angeles, CA, USA) to develop multilevel structural equations to test the theoretical model. Because supervisors self-rated their leader PsyCap, data aggregation was not required. However, before statistical analysis, the interclass difference between outcome variables of innovative behavior required verification to assess the necessity of cross-level analysis. The ICC(1) of innovative behavior was 0.39, which exceeded 0.12. This indicated that 39% of employee innovation variance was caused by - class differences, thereby necessitating a cross-level analysis for hypothesis verification.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

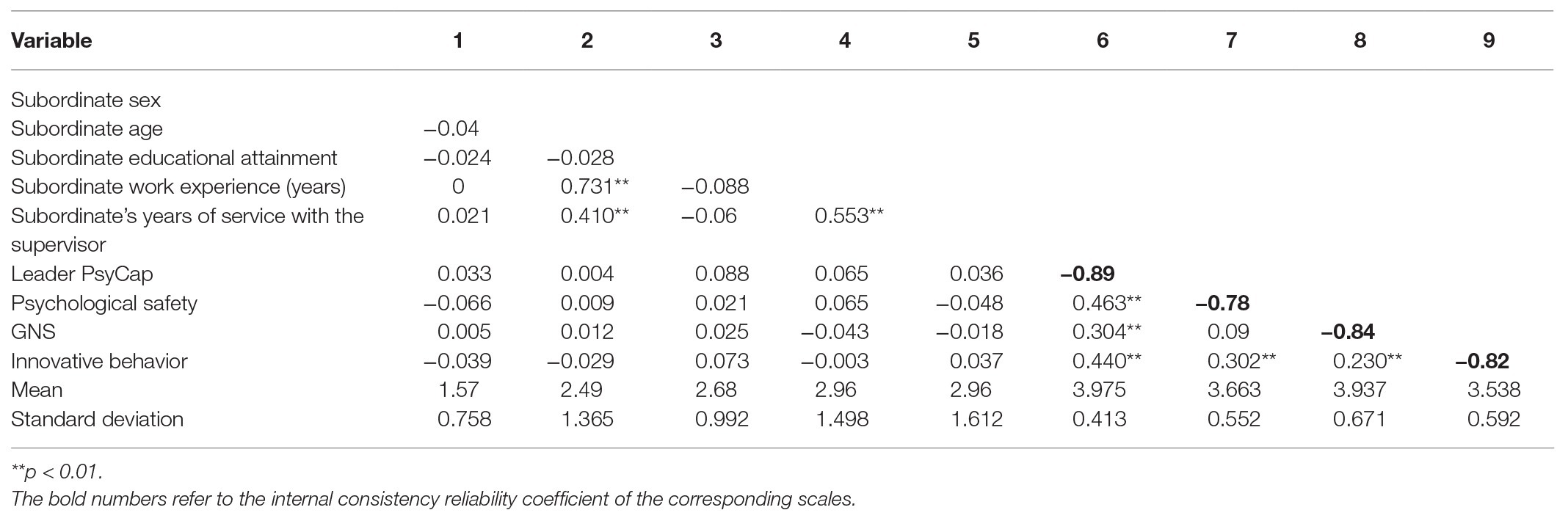

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all variables. The coefficients between leader PsyCap and psychological safety (r = 0.463; p < 0.01) and between leader PsyCap and innovative behavior (r = 0.440; p < 0.0) reached significance. The coefficient between psychological safety and innovative behavior (r = 0.302; p < 0.01) was also significant, demonstrating that the variables of interest were closely related and thereby providing the foundation for subsequent hypothesis verification.

Hypothesis Verification

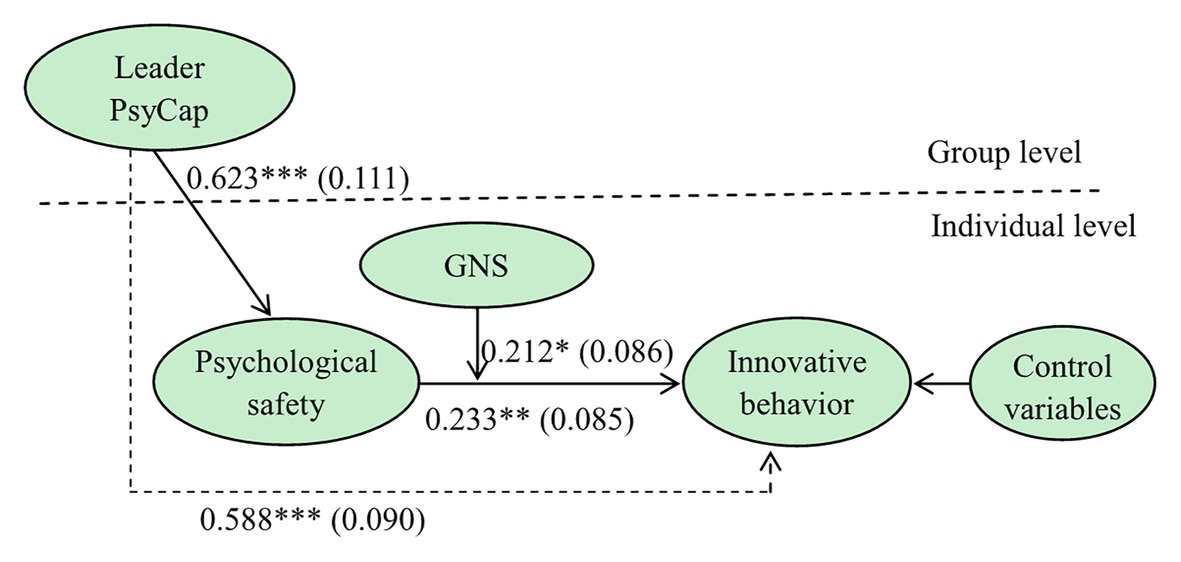

To verify the aforementioned hypotheses, this study used Mplus7.4 to develop a multilevel structural equation model (Figure 2). An analysis of this model identified the path coefficients and standard deviations (SDs) between all variables. Specifically, leader PsyCap positively affected psychological safety (β = 0.623; p < 0.001), supporting H2a. Similarly, psychological safety positively affected innovative behavior (β = 0.233; p < 0.01), supporting H2b. The verification of H2a and H2b supported H2c. The direct effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior was also significant (β = 0.588; p < 0.001), indicating that psychological safety partially mediated the relationship between leader PsyCap and innovative behavior. Finally, GNS positively moderated the relationship between psychological safety and innovative behavior (β = 0.212; p < 0.05), supporting H3a.

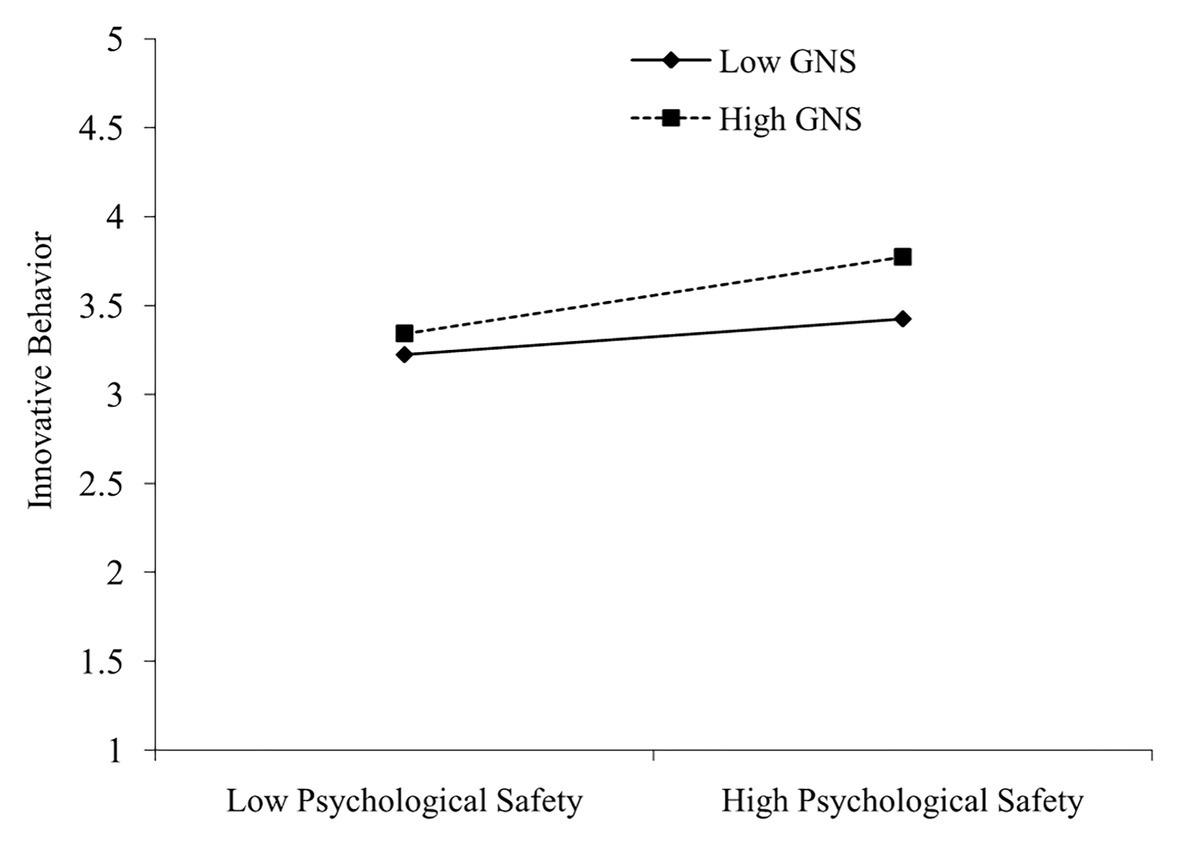

To clearly explain the moderating effect of GNS on the relationship between psychological safety and innovative behavior, we plotted simple slopes for the relationship between psychological safety and innovative behavior at high (mean + SD) and low (mean-SD) levels of GNS (Figure 3). Figure 3 illustrates that, compared with employees with low GNS, the regression slope between innovative behavior and psychological safety is greater for employees with high GNS. Specifically, when GNS was high, the positive effect of psychological safety on innovative behavior was significant (β = 0.39; p < 0.001). By contrast, when GNS was low, the positive effect of psychological safety on innovative behavior was nonsignificant (β = 0.18; p > 0.05), thereby supporting H3a.

Figure 3. Moderating effect of growth need strength on the relationship between psychological safety and innovative behavior.

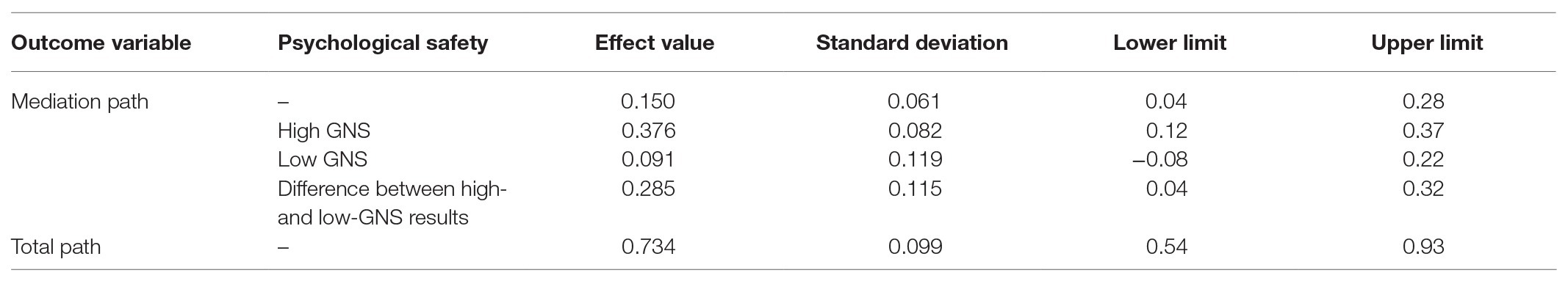

Because a cross-level analysis was used to verify the proposed hypotheses, the researchers simulated the confidence interval by using the Monte Carlo approaches, the results of which were used to verify the total, mediating, and moderated mediating effects. As presented in Table 3, the mediating role of psychological safety in the relationship between leader PsyCap and innovative behavior was 0.150 (95% confidence interval, CI: 0.04–0.28), further supporting H2c. The direct effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior was 0.734 (95% CI: 0.54–0.93); thus, H1 was supported. In a high-GNS scenario, the indirect effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior through psychological safety was 0.376 (95% CI: 0.12–0.37), whereas the effect was 0.091 in a low-GNS scenario (95% CI: −0.08–0.22), resulting in a difference of 0.285 between the two values (95% CI: 0.04–0.32). Therefore, the indirect effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior via psychological safety was moderated by GNS. The higher the GNS, the stronger the effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior through psychological safety, thereby verifying H3b.

Discussion

On the basis of the conservation of resources theory, this study developed a multilevel linear model to analyze the effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior. The study findings were as follows: (1) Leader PsyCap positively affected subordinate innovative behavior. Specifically, leaders with high PsyCap are confident about future development, adept at eliciting positive emotions in employees, and can support their employees with empathy. Therefore, supervisors with high leader PsyCap can positively affect employee innovation; (2) Psychological safety partially mediated the effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior, suggesting that leader PsyCap affects innovative behavior through its effect on risk perception among employees; (3) Regarding the moderating effect of GNS on the relationship between psychological safety and innovative behavior, this study demonstrated that innovative behavior was consistently rare among employees with low GNS regardless of psychological safety in the workplace. By contrast, when employees with high GNS perceived that innovation failure would not affect their status or image, they actively engaged in innovative work.

Theoretical Implications

This study investigated the impact of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior, which contributes to leadership research, especially leader PsyCap research. Most of the previous studies highlight on the diverse style of leadership, such as humble leadership, coaching leadership, and so on. Besides this, research on the relationship between PsyCap and employees’ innovation are merely limited to employees’ PsyCap (Bruccoleri and Riccobono, 2018). Considering leader PsyCap as an antecedent, this study examined the positive impact of leader PsyCap on employees’ innovative behavior through the effect of psychological safety, elaborating the mechanism of leader PsyCap affecting employee innovation and diversifying and filling gaps in leader PsyCap research.

The researchers explored the mediation effect of subordinate psychological safety in the relationship between leader PsyCap and innovative behavior. Previous empirical studies verified that psychological safety was a vital cognitive process which links leaders and followers (Hirak et al., 2012; Zhu and Zhang, 2019), but existing literature over the research on antecedents of psychological safety is included in an area that involves the following styles: transformational leadership (i.e., Detert and Burris, 2007; Nemanich and Vera, 2009), ethical leadership (i.e., Walumbwa and Schaubroeck, 2009; Sağnak, 2017; Hu et al., 2018; Men et al., 2018), servant leadership (i.e., Schaubroeck et al., 2011; Chughtai, 2016), empowering leadership (i.e., Jada and Mukhopadhyay, 2018), humble leadership (i.e., Wang et al., 2018a,b), and leader-member exchange (Hu et al., 2018; Opoku et al., 2020). Moreover, existing studies over the result of psychological safety mainly focus on information sharing (Siemsen et al., 2009; Bunderson and Boumgarden, 2010), voice behavior (i.e., Chughtai, 2016; Sağnak, 2017; Hu et al., 2018; Jada and Mukhopadhyay, 2018; Opoku et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020), creativity (Wang et al., 2018a,b), and task performance (Baer and Frese, 2003; Schaubroeck et al., 2011). Scarce literature discuss the mediating effect of psychological safety in the relationship between leader PsyCap and employees’ innovative behavior. Frazier et al. (2017) suggested that examining leadership impact on psychological safety from various prospect will contribute to the research on psychological safety and leadership. This finding provides insight for leader PsyCap theories, which consist of findings by Frazier et al. (2017), thereby expanding research on the mechanism of psychological safety and supplementing current research on psychological safety and leadership.

This study revealed and confirmed the moderating effect of GNS on the relationship between psychological safety and innovative behavior. Research on GNS originated from the job characteristics model. However, current research regard GNS a specific personality trait and explore GNS effect on employees’ positive behavior beyond the model (i.e., Shalley et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018b). Similarly, this study considers GNS a positive personality trait, introducing GNS to the research framework for employee innovation and examining the moderating effect of GNS on the effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior through psychological safety on the basis of the conversation of resource theory. Individuals with high GNS proactively invested resources in innovation when their psychological safety was guaranteed. By contrast, in scenarios with high GNS that lacked safety, low GNS with sufficient safety, and low GNS that lacked safety, individuals proactively reduced resource-consuming innovation to protect their resources. Consequently, innovative behavior in these three scenarios was rare. Newman et al. (2017) suggested that alternate theories, such as the conservation of resources theory, should be adopted to explain how psychological safety, generated by resource acquisition at work, encourages employees to invest their resources in learning, self-growth, and self-development. The theoretical analyses and empirical results of this study responded to this suggestion and applied the conservation of resources theory.

Practical Implications

Organizations should emphasize the development and management of leader PsyCap. The path of leader PsyCap affecting innovative behavior through employee psychological safety demonstrated that the positive effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior should be highlighted in organizational management. Firstly, organizations should pay more attention to developing and improving leader PsyCap. Due to the state-like and exploitable traits of PsyCap (Luthans et al., 2010), organizations should purposely arrange for managers to receive specific training and increase leader PsyCap by a series of practice in accordance with the four dimensions of construct of PsyCap. PsyCap can also be rapidly improved by building a positive organizational climate, supporting, authorizing, positively evaluating, and crediting leaders who accept the training to develop PsyCap, which can give rise to expected outcomes (Petersen, 2015). Secondly, leaders should foster the effective transmission of their PsyCap. Besides this, leaders should not only transmit high PsyCap but also make efforts to transmit their PsyCap to all the members consistently, which can generate effective incentive to their teams (Rego et al., 2017). In other words, to make good use of leader PsyCap, leaders have to dedicate to building a fair and harmonious climate, present their passion, confidence, resilience, and creativity to their followers indifferently, be liable for their commitment, and keep a good interpersonal relation with their followers in the routine work.

Enterprises should emphasize and strengthen employee GNS. Although leader PsyCap can stimulate innovative behavior in employees, the effect can vary between employees with different levels of GNS. Because employees with high GNS exhibit more innovative behaviors when they perceive sufficient psychological safety, organizations can recruit such employees by designing specific standards for talent recruitment, thereby increasing innovative behavior. Additionally, enterprises can implement suitable training and propose corresponding encouragement policies to raise awareness of self-growth among employees. Subsequently, employees should be assigned suitable tasks at different stages and be provided with opportunities and a platform to fulfill their growth needs. Employees can then continually increase their growth needs, creating a virtuous cycle in which employees enhance their innovative thinking skills and develop the habit of innovation.

Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

First, this study adopted an indirect measurement research method and collected data by using a questionnaire. Future research should adopt a quasi-experimental design or conduct experiments to enhance the accuracy of research conclusions. Second, this study used subjective indicators to measure the variables of interest. Third, this study did not take the sectors that leaders and subordinates were employed into account in the process of data analysis, although it is theoretically evidenced that GNS is highly correlated to the individuals’ working environment. Thus, future studies should incorporate the sectors that leaders and subordinates were employed into relevant statistical analysis. Currently, leader PsyCap research has been inadequate. In particular, research on the structure and measurement of leader PsyCap in China remains lacking and warrants exploration. Finally, although this study investigated the effect of leader PsyCap on innovative behavior mediated by psychological safety from the perspectives of employee awareness, motivation, and demands, several internal and external mechanisms in the research process might have remained unknown. Therefore, future studies should focus on clarifying these mechanisms.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

YW designed the study and collected the data. YC wrote and revised the manuscript. YW and YZ gave guidance throughout the whole research process. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos.71772069 and 71602075) and the General Foundation Program of the Ministry of Education of Humanities and Social Science (Grant Nos.15YJC630197 and 17YJA630101).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 10, 123–167.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., and Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 39, 1154–1184.

Anderson, N., Potocnik, K., and Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations a state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. J. Manag. 40, 1297–1333. doi: 10.1177/0149206314527128

Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., and Luthans, F. (2011a). Experimentally analyzing the impact of leader positivity on follower positivity and performance. Leadersh. Q. 22, 282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.02.004

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., and Mhatre, K. H. (2011b). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 22, 127–152. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.20070

Avey, J. B., Richmond, F. L., and Nixon, D. R. (2012). Leader positivity and follower creativity: an experimental analysis. J. Creat. Behav. 46, 99–118. doi: 10.1002/jocb.8

Baer, M., and Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. J. Organ. Behav. 24, 45–68. doi: 10.1002/job.179

Brissette, I., Scheier, M. F., and Carver, C. S. (2002). The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82, 102–111. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.102

Bruccoleri, M., and Riccobono, F. (2018). Management by objective enhances innovation behavior: an exploratory study in global management consulting. Knowl. Process. Manag. 25, 180–192. doi: 10.1002/kpm.1577

Bunderson, J. S., and Boumgarden, P. (2010). Structure and learning in self-managed teams: why “bureaucratic” teams can be better learners. Organ. Sci. 21, 609–624. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1090.0483

Carmeli, A., Sheaffer, Z., Binyamin, G., Reiter-Palmon, R., and Shimoni, T. (2014). Transformational leadership and creative problem-solving: the mediating role of psychological safety and reflexivity. J. Creat. Behav. 48, 115–135. doi: 10.1002/jocb.43

Castañer, X. (2016). Redefining creativity and innovation in organisations: suggestions for redirecting research. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 20:1640001. doi: 10.1142/s1363919616400016

Chae, H., and Choi, J. N. (2018). Contextualizing the effects of job complexity on creativity and task performance: extending job design theory with social and contextual contingencies. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 91, 316–339. doi: 10.1111/joop.12204

Chen, Q., Wen, Z., Kong, Y., Niu, J., and Hau, K. T. (2017). Influence of leaders’ psychological capital on their followers: multilevel mediation effect of organizational identification. Front. Psychol. 8:1776. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01776

Chughtai, A. A. (2016). Servant leadership and follower outcomes: mediating effects of organizational identification and psychological safety. J. Psychol. 150, 866–880. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2016.1170657

De Jong, R. D., Mandy, E. G., Van Der Velde, and Jansen, P. G. W. (2001). Openness to experience and growth need strength as moderators between job characteristics and satisfaction. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 9, 350–356. doi: 10.1111/1468-2389.00186

Detert, J. R., and Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad. Manag. J. 50, 869–884. doi: 10.2307/20159894

Devloo, T., Anseel, F., Beuckelaer, A. D., and Salanova, M. (2014). Keep the fire burning: reciprocal gains of basic need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and innovative work behavior. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 24, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/1359432x.2014.931326

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 44, 350–383.

Edmondson, A. C. (2004). “Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: a group level lens” in Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches. eds. R. M. Kramer and K. S. Cook (New York: Russell Sage Foundation), 239–272.

Edmondson, A. C., Bohmer, R. M., and Pisano, G. P. (2001). Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Adm. Sci. Q. 46, 685–716. doi: 10.2307/3094828

Edmondson, A. C., and Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 1, 23–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

Fang, Y. C., Chen, J. Y., Wang, M. J., and Chen, C. Y. (2019). The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behaviors: the mediation of psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 10:1803. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01803

Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., and Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: a meta-analytic review and extension. Pers. Psychol. 70, 113–165. doi: 10.1111/peps.12183

George, J. M., and Zhou, J. (2001). When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: an interactional approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 86:513. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.513

Ghosh, K. (2010). Developing organizational creativity and innovation: toward a model of self-leadership, employee creativity, creativity climate and workplace innovative orientation. Manag. Res. Rev. 38, 1126–1148. doi: 10.1108/MRR-01-2014-0017

Ghosh, K. (2015). Developing organizational creativity and innovation. Manag. Res. Rev. 38, 1126–1148. doi: 10.1108/mrr-01-2014-0017

Graen, G. B., Scandura, T. A., and Graen, M. R. (1986). A field experimental test of the moderating effects of growth need strength on productivity. J. Appl. Psychol. 71, 484–491. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.484

Grgens-Ekermans, G., and Herbert, M. (2013). Psychological capital: internal and external validity of the psychological capital questionnaire (pcq-24) on a south African sample. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 39, 1–12. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v39i2.1131

Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2010). “A meta-analysis of work engagement: relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences” in Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research. eds. A. B. Bakker and M. P. Leiter (London: Psychology. Press) 12–117.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., and Bowler, W. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: the mediating role of motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 93–106. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.93

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., and Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 40, 1334–1364. doi: 10.1177/0149206314527130

Halbesleben, J. R. B., and Wheeler, A. R. (2011). I owe you one: coworker reciprocity as a moderator of the day-level exhaustion-performance relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 32, 608–626. doi: 10.1002/job.748

Harbi, J., Alarifi, S., and Mosbah, A. (2019). Transformation leadership and creativity: effects of employees psychological empowerment and intrinsic motivation. Pers. Rev. 48, 1082–1099. doi: 10.1108/PR-11-2017-0354

Heye, D. (2006). Creativity and innovation: two key characteristics of the successful 21st century information professional. Bus. Inf. Rev. 23, 252–257. doi: 10.1177/0266382106072255

Hirak, R., Peng, A. C., Carmeli, A., and Schaubroeck, J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: the importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadersh. Q. 23, 107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.009

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., and Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Hon, A. H. Y. (2012). Shaping environments conductive to creativity: the role of intrinsic motivation. Cornell Hosp. Q. 53, 53–64. doi: 10.1177/1938965511424725

Hon, A. H. Y. (2013). Does job creativity requirement improve service performance? A multilevel analysis of work stress and service environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 35, 161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.06.003

Hon, A. H. Y., and Lu, L. (2015). Are we paid to be creative? The effect of compensation gap on creativity in an expatriate context. J. World Bus. 50, 159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2014.03.002

Hon, A. H. Y., and Lui, S. S. (2016). Employee creativity and innovation in organizations: review, integration, and future directions for hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 28, 862–885. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-09-2014-0454

Hu, Y., Zhu, L., Zhou, M., Li, J., Maguire, P., Sun, H., et al. (2018). Exploring the influence of ethical leadership on voice behavior: how leader-member exchange, psychological safety and psychological empowerment influence employees’ willingness to speak out. Front. Psychol. 9:1718. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01718

Jada, U. R., and Mukhopadhyay, S. (2018). Empowering leadership and constructive voice behavior: a moderated mediated model. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 26, 226–241. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-03-2017-1146

Janssen, O. (2003). Innovative behavior and job involvement at the price of conflict and less satisfactory relations with co-workers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 76, 347–364. doi: 10.1348/096317903769647210

Jensen, S. M., and Luthans, F. (2006). Relationship between entrepreneurs’ psychological capital and their authentic leadership. J. Manager. Iss. 18, 254–273.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724.

Kiazad, K., Seibert, S. E., and Kraimer, M. L. (2014). Psychological contract breach and employee innovation: a conservation of resources perspective. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 87, 535–556. doi: 10.1111/joop.12062

Lan, T., Chen, M., Zeng, X., and Liu, T. (2020). The influence of job and individual resources on work engagement among Chinese police officers: a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 11:497. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00497

Li, T., Liang, W., Yu, Z., and Dang, X. (2020). Analysis of the influence of entrepreneur’s psychological capital on employee’s innovation behavior under leader-member exchange relationship. Front. Psychol. 11:1853. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01853

Li, R., Tian, X. M., and Ling, W. Q. (2015). Mechanisms of how managerial openness and supervisor-subordinate guanxi impact on employee pro-social rule breaking. Sys. Eng. Theory Pract. 35, 342–357.

Li, Y., Yang, B., and Ma, L. (2018). When is task conflict translated into employee creativity? The moderating role of growth need strength. J. Pers. Psychol. 17, 22–32. doi: 10.1027/1866-5888/a000192

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., and Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: a two-wave examination. Acad. Manag. J. 55, 71–92. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Liang, F., and Li, S. W. (2016). The study on the relationship between transformational leadership and employee innovative behavior: a cross-layer model. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 33, 147–153. doi: 10.6049/kjjbydc.2016080675

Lin, X. S., Qian, J., Li, M., and Chen, Z. X. (2016). How does growth need strength influence employee outcomes? The roles of hope, leadership, and cultural value. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 29, 2524–2551. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1255901

Liu, D., Jiang, K., Shalley, C. E., Keem, S., and Zhou, J. (2016). Motivational mechanisms of employee creativity: a meta-analytic examination and theoretical extension of the creativity literature. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 137, 236–263. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.08.001

Liu, B., Qi, L., and Xu, L. A. (2017). Cross-level impact study of inclusive leadership on employee feedback seeking behavior. J. Manag. 14, 677–685. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-884x.2017.05.005

Luthans, F. (2012). Psychological capital: implications for hrd, retrospective analysis, and future directions. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 23, 1–8. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.21119

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., and Peterson, S. J. (2010). The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 21, 41–67. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.20034

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., and Norman, S. M. (2007a). Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 60, 541–572. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006847

Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., and Avolio, B. J. (2007b). Psychological capital: Developing the human competitive edge. New York: Oxford University Press.

Martins, E. C., and Terblanche, F. (2013). Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 6, 64–74. doi: 10.1108/14601060310456337

Masten, A. S., and Reed, M. G. (2002). “Resilience in development” in The handbook of positive psychology. eds. S. R. Snyder and S. J. Lopez (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 74–88.

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., and Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 77, 11–37. doi: 10.1348/096317904322915892

Men, C., Fong, P. S. W., Huo, W., Zhong, J., Jia, R., and Luo, J. (2018). Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: a moderated mediation model of psychological safety and mastery climate. J. Bus. Ethics 166, 461–472. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-4027-7

Mohamad, A. A., Lo, M. C., Ramayah, T., and Ling, K. (2019). The effectiveness of LMX in employee outcomes in the perspective of organizational change. Asia Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 19, 112–120.

Mumtaz, S., and Parahoo, S. K. (2019). Promoting employee innovation performance: examining the role of self-efficacy and growth need strength. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 69, 704–722. doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-12-2017-0330

Nemanich, L. A., and Vera, D. (2009). Transformational leadership and ambidexterity in the context of an acquisition. Leadersh. Q. 20, 19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.11.002

Newman, A., Donohue, R., and Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: a systematic review of the literature. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 27, 521–535. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

Newman, A., Ucbasaran, D., Zhu, F., and Hirst, G. (2014). Psychological capital: a review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 35, S120–S138. doi: 10.1002/job.1916

Nguyen, L. T. (2019). The impact of training on turnover intention: the role of growth need strength among Vietnamese female employees. S. East Asian J. Manag. 13, 1–17. doi: 10.21002/seam.v13i1.9996

Norman, S. M., Avolio, B. J., and Luthans, F. (2010). The impact of positivity and transparency on trust in leaders and their perceived effectiveness. Leadersh. Q. 21, 350–364. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.002

Norman, S., Luthans, B., and Luthans, K. (2005). The proposed contagion effect of hopeful leaders on the resiliency of employees and organizations. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 12, 55–64. doi: 10.1177/107179190501200205

Odoardi, C., Montani, F., Boudrias, J. S., and Battistelli, A. (2015). Linking managerial practices and leadership style to innovative work behavior: the role of group and psychological processes. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 36, 545–569. doi: 10.1108/lodj-10-2013-0131

Oldham, G. R., and Hackman, J. R. (2010). Not what it was and not what it will be: the future of job design research. J. Organ. Behav. 31, 463–479. doi: 10.1002/job.678

Opoku, M. A., Choi, S. B., and Kang, S. W. (2020). Psychological safety in Ghana: empirical analyses of antecedents and consequences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:214. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010214

Palanski, M. E., and Vogelgesang, G. R. (2011). Virtuous creativity: the effects of leader behavioural integrity on follower creative thinking and risk taking. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 28, 259–269. doi: 10.1002/cjas.219

Parahoo, S. K., Mumtaz, S., and Salem, S. (2017). Modelling organisational innovation in UAE: investigating the love triangle involving leadership, organisational culture and innovation. Int. J. Knowl. Manage. Tour. Hospital. 1:110. doi: 10.1504/IJKMTH.2017.10005431

Petersen, K. (2015). Authentic leadership and unit outcomes: additive and interactive contributions of climate and psychological capital. [PhD Thesis], Bellevue Univ., Bellevue, Neb

Peterson, S. J., Walumbwa, F. O., Byron, K., and Myrowitz, J. (2009). CEO positive psychological traits, transformational leadership, and firm performance in high technology start-up and established firms. J. Manag. 35, 348–368. doi: 10.1177/0149206307312512

Rego, A., Yam, K. C., Owens, B. P., Story, J. S. P., Miguel, P. E. C., and Bluhm, D. (2017). Conveyed leader PsyCap predicting leader effectiveness through positive energizing. J. Manag. 45, 1–24. doi: 10.1177/0149206317733510

Sağnak, M. (2017). Ethical leadership and teachers’ voice behavior: the mediating roles of ethical culture and psychological safety. Educ. Sci. 17, 1101–1117. doi: 10.12738/estp.2017.4.0113

Schaubroeck, J., Lam, S. S. K., and Peng, A. C. (2011). Cognition-based and affect-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influences on team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 863–871. doi: 10.1037/a0022625

Scott, S. G., and Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: a path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 37, 580–607. doi: 10.2307/256701

Shalley, C. E., Gilson, L. L., and Blum, T. C. (2009). Interactive effects of growth need strength, work context, and job complexity on self-reported creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 52, 489–505. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2009.41330806

Sheppard, B., Hurley, N., and Dibbon, D. (2010). Distributed leadership, teacher morale, and teacher enthusiasm: Unravelling the leadership pathways to school success. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Denver, Colorado.

Shi, J. T. (2012). Influence of passion on innovative behavior: an empirical examination in People’s Republic of China. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 6, 8889–8896. doi: 10.5897/AJBM11.2250

Shilling, M. A. (2006). Strategic management of technological innovation. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Shin, S. J., Yuan, F., and Zhou, J. (2017). When perceived innovation job requirement increases employee innovative behavior: a sense making perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 38, 68–86. doi: 10.1002/job.2111

Siemsen, E., Roth, A. V., Balasubramanian, S., and Anand, G. (2009). The influence of psychological safety and confidence in knowledge on employee knowledge sharing. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 11, 429–447. doi: 10.1287/msom.1080.0233

Snyder, C. R., and Shorey, H. (2003). “Hope and leadership” in Encylopedia of leadership. ed. Ì. L. Christensen (Harrison, NY: Berkshire Publishers).

Song, Y., Peng, P., and Yu, G. (2020). I would speak up to live up to your trust: the role of psychological safety and regulatory focus. Front. Psychol. 10:2966. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02966

Story, J. S., Youssef, C. M., Luthans, F., Barbuto, J. E., and Bovaird, J. (2013). Contagion effect of global leaders’ positive psychological capital on followers: does distance and quality of relationship matter? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 24, 2534–2553. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.744338

Su, W., Lin, X., and Ding, H. (2019). The influence of supervisor developmental feedback on employee innovative behavior: a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 10:1581. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01581

Tang, Y., Shao, Y. F., and Chen, Y. J. (2019). Assessing the mediation mechanism of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on innovative behavior: the perspective of psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 10:2699. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02699

Tiegs, R. B., Tetrick, L. E., and Fried, Y. (1992). Growth need strength and context satisfactions as moderators of the relations of the job characteristics model. J. Manag. 18, 575–593.

Tsegaye, W. K., Su, Q., and Malik, M. (2020). The quest for a comprehensive model of employee innovative behavior: the creativity and innovation theory perspective. J. Dev. Areas 54, 163–178. doi: 10.1353/jda.2020.0022

Turró, A., Urbano, D., and Peris-Ortiz, M. (2014). Culture and innovation: the moderating effect of cultural values on corporate entrepreneurship. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 88, 360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2013.10.004

Walumbwa, F. O., Peterson, S. J., Avolio, B. J., and Hartnell, C. (2010). An investigation of the relationships among leader and follower psychological capital, service climate, and job performance. Pers. Psychol. 63, 937–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01193.x

Walumbwa, F. O., and Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 94, 1275–1286. doi: 10.1037/a0015848

Wang, Y. F., Liu, J., and Zhu, Y. (2018a). Humble leadership, psychological safety, knowledge sharing, and follower creativity: a cross-level investigation. Front. Psychol. 9:1727. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01727

Wang, Y. F., Liu, J. Q., and Zhu, Y. (2018b). How does humble leadership promote follower creativity? The roles of psychological capital and growth need strength. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 39, 507–521. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-03-2017-0069

Wang, H., Sui, Y., Luthans, F., Wang, D., and Yanhong, W. U. (2013). Impact of authentic leadership on performance: role of followers’ positive psychological capital and relational processes. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 5–21. doi: 10.1002/job.1850

Wang, Y. F., and Zhu, Y. (2012). Organizational socialization, trust, knowledge sharing and innovation behavior: research on mechanism and path. R&D Manag. 24, 34–42. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-8308.2012.02.005

Wheeler, A. R., Harris, K. J., and Sablynski, C. J. (2012). How do employees invest abundant resources? The mediating role of work effort in the job-embeddedness/job-performance relationship. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 42, E244–E266. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.01023.x

Woodman, R., Sawyer, J., and Griffin, R. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 18, 293–321.

Xu, J., Liu, Y., and Chung, B. (2017). Leader psychological capital and employee work engagement: the roles of employee psychological capital and team collectivism. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 38, 969–985. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-05-2016-0126

Zeng, H., Zhao, L., and Zhao, Y. (2020). Inclusive leadership and taking-charge behavior: roles of psychological safety and thriving at work. Front. Psychol. 11:62. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.0006

Zhu, Y., and Wang, Y. F. (2011). The relationship between entrepreneur psychological capital and employee’s innovative behavior: the strategic role of transformational leadership and knowledge sharing. Adv. Mater. Res. 282–283, 691–696. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.282-283.691

Zhu, J., and Zhang, B. (2019). The double-edged sword effect of abusive supervision on subordinates’ innovative behavior. Front. Psychol. 10:66. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00066

Keywords: psychological capital, leader psychological capital, psychological safety, growth need strength, innovative behavior, conservation of resources theory

Citation: Wang Y, Chen Y and Zhu Y (2021) Promoting Innovative Behavior in Employees: The Mechanism of Leader Psychological Capital. Front. Psychol. 11:598090. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.598090

Edited by:

Konstantinos G. Kafetsios, University of Crete, GreeceReviewed by:

Konstantinos Papachristopoulos, University of Crete, GreeceAndreas Tsounis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Copyright © 2021 Wang, Chen and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Chen, NDEwMjEwNzk3QHFxLmNvbQ==; Yu Zhu, emh1eXVAam51LmVkdS5jbg==

Yanfei Wang

Yanfei Wang Yi Chen

Yi Chen Yu Zhu3*

Yu Zhu3*