94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Psychol., 09 December 2020

Sec. Emotion Science

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586161

This article is part of the Research TopicExpanding the Science of CompassionView all 20 articles

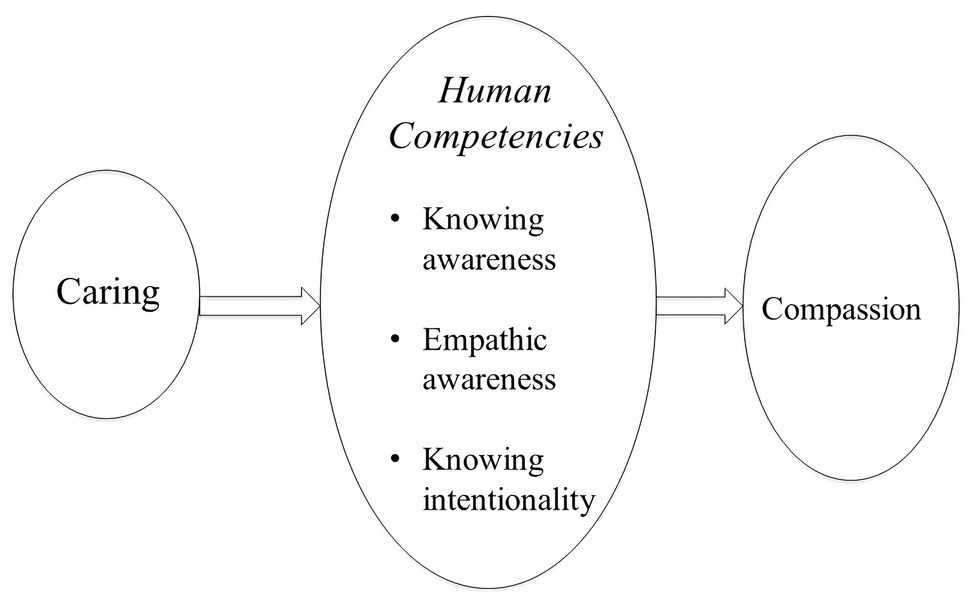

The concept, benefits and recommendations for the cultivation of compassion have been recognized in the contemplative traditions for thousands of years. In the last 30 years or so, the study of compassion has revealed it to have major physiological and psychological effects influencing well-being, addressing mental health difficulties, and promoting prosocial behavior. This paper outlines an evolution informed biopsychosocial, multicomponent model to caring behavior and its derivative “compassion” that underpins newer approaches to psychotherapy. The paper explores the origins of caring motives and the nature and biopsychosocial functions of caring-attachment behavior. These include providing a secure base (sources of protection, validation, encouragement and guidance) and safe haven (source of soothing and comfort) for offspring along with physiological regulating functions, which are also central for compassion focused therapy. Second, it suggests that it is the way recent human cognitive competencies give rise to different types of “mind awareness” and “knowing intentionality” that transform basic caring motives into potentials for compassion. While we can care for our gardens and treasured objects, the concept of compassion is only used for sentient beings who can “suffer.” As psychotherapy addresses mental suffering, cultivating the motives and competencies of compassion to self and others can be a central focus for psychotherapy.

There is a long history of philosophical and spiritual writings, highlighting the value of compassion as an antidote to suffering and anti-social behavior (Dalai Lama, 1995; Lampert, 2005; Ricard, 2015). However, it has only been in the last 30 years or so that we have seen substantial research on the neurophysiological, psychological, and social dimensions of compassion and compassion training (for reviews see Weng et al., 2013; Gilbert, 2017a; Seppälä et al., 2017; Stevens and Woodruff, 2018; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019; Singer and Engert, 2019; Di Bello et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020a). This work has been accompanied by the development of various forms of general compassion training (e.g., Jazaieri et al., 2013; Singer and Engert, 2019; Condon and Makransky, 2020) and cultivating compassion to address personal problems like self-criticism (Neff and Germer, 2017) and mental health issues (Germer and Siegel, 2012; Kirby and Gilbert, 2017). Among the latter, the most well-developed and evidence-based is mindful self-compassion of Neff and Germer (2017) to address self-criticism, and also cognitively-based compassion training, which combines the elements of cognitive therapy with Buddhist practices (Mascaro et al., 2017). This paper explores compassion focused therapy (CFT) rooted in an evolution informed, biopsychosocial approach to mental health problems and psychotherapy (Gilbert, 1984, 1992a,b, 1995, 2019). CFT is an integrative, multidisciplinary, process-based therapy that utilizes insights and wisdoms from many of the main schools of psychotherapy (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2007a,b, 2019; Bell et al., 2020a,b; Fox et al., 2020) with increasing evidence of effectiveness (Craig et al., 2020; Fox et al., 2020). CFT was developed with and for people with mental health difficulties, particularly those who had not responded to other therapies, who had problems with self-criticism, shame, and trauma, often came from difficult backgrounds (Gilbert, 2000, 2010; Gilbert and Choden, 2013) and were fearful and/or distrustful of compassion from others and/or for self (Pauley and McPherson, 2010; Gilbert et al., 2011, 2014; Kirby et al., 2019). This paper is in two main sections. The first is an exploration of the evolution and processes of compassion and some of the key themes that underpin its application in psychotherapy. The second part explores the application of compassion to psychotherapy.

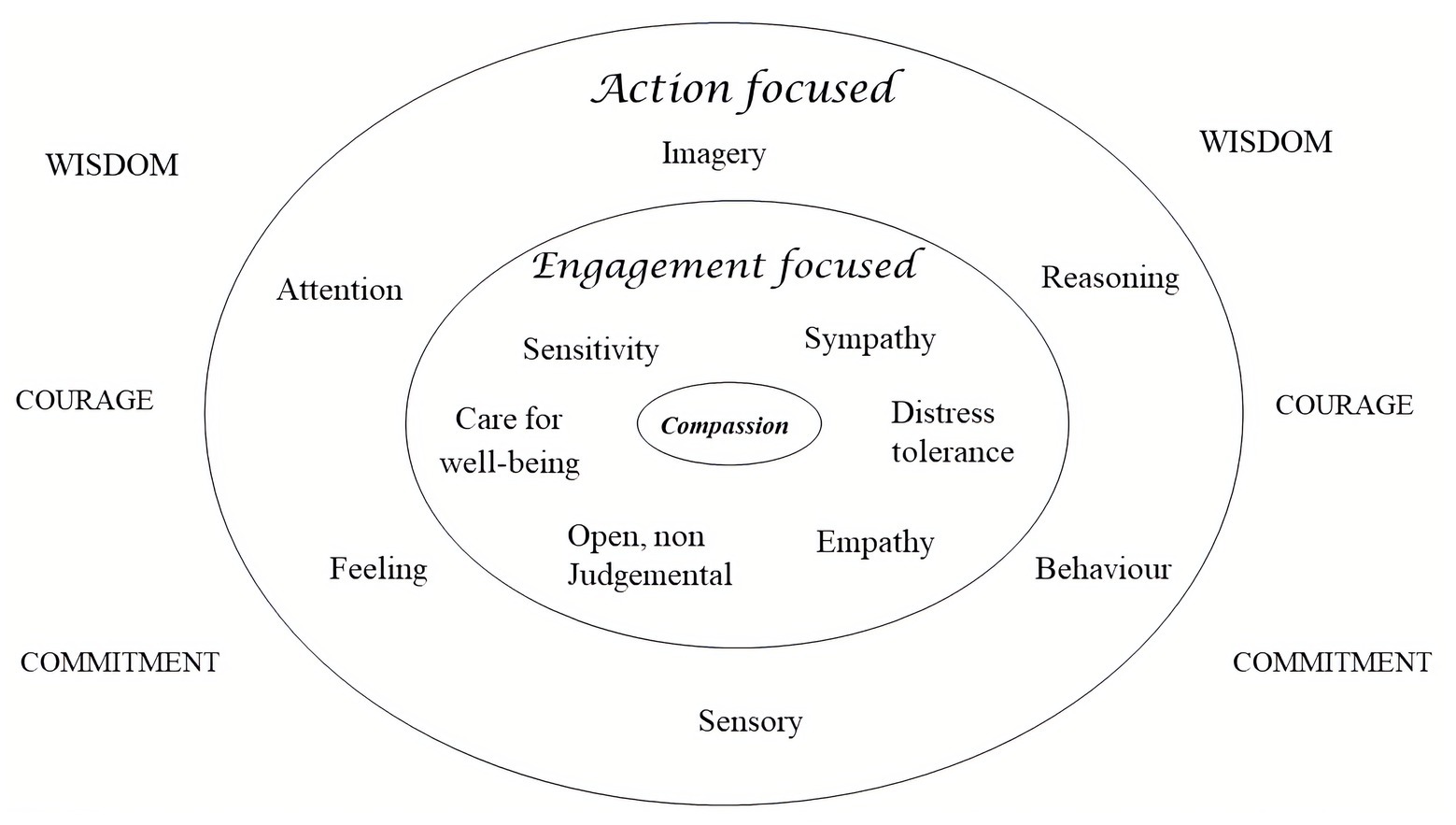

Since there are different approaches to compassion and its application in psychotherapy (Gilbert, 2017b), this section explores the link between the evolution of caring and the emergence of compassion as a human motive and process. When trying to define compassion, we can start by noting that some approaches seek to identify particular core clusters of psychological processes and attributes (often suggested by the contemplative traditions) associated with it. These suggested core processes are then subjected to various forms of factor analysis (Strauss et al., 2016). Using this technique on a number of different approaches and measures, Strauss et al. (2016) concluded that:

A range of definitions from Buddhist and Western psychological perspectives were considered and five components of compassion were identified: recognition of suffering; understanding its universality; feeling sympathy, empathy, or concern for those who are suffering (which we describe as emotional resonance); tolerating the distress associated with the witnessing of suffering; and motivation to act or acting to alleviate the suffering. Each of these components has been articulated by several published definitions of compassion, although no single existing definition explicitly includes all five of them (p. 25)

While these are a commonly agreed set of processes for compassion, as with all such approaches, what we get out of a factor analysis very much depends on what we put into it. This is similar for the controversies in psychiatric diagnosis, which can use the same techniques with the same potential difficulties. Identifying core processes can help us to share conceptualizations but the exact phenomenon included in a cluster or factor can vary, sometimes quite considerably and in the clinical sciences be unreliable ways of identifying specific syndromes [see for example the controversies on one approach to self-compassion (Muris and Otgaar, 2020; Neff, 2020)]. As with psychiatric diagnosis, we can wonder if these are discrete states, traits, or if they are more fluid? Do we need all of the components for any particular act to be regarded as compassionate? Can compassion take place in the absence of (say) accurate empathy (see below), and is there a role for moral and rational compassion where we override what we actually feel (Loewenstein and Small, 2007)? Additionally, many of these qualities are dimensional – we can (say) have “degrees” of being moved by suffering. These dimensions will be affected by relational qualities such as emotional closeness (liking) versus seeing others as enemies (disliking) and trust. All of these attributes may be present, but a person may not actually follow through and act compassionately (Poulin, 2017). So, although statistical approaches have important roles to play in identifying core ways of “being compassionate,” to understand the complex processes of compassion itself requires other approaches too. For a recent major review of these issues (see Mascaro et al., 2020).

Understanding how and why caring and compassion evolved gives insight into a whole range of biopsychosocial processes (e.g., Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2005a, 2009a, 2017a; Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; Goetz et al., 2010; Porges and Furman, 2011; Keltner et al., 2014; Brown and Brown, 2015, 2017; Carter et al., 2017; Porges, 2017; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019). Recognizing that compassion can be understood as an evolved strategy, supporting survival and reproduction, and as a basic, personally experienced motivation that can be in conflict with other strategies and motivations (Gilbert, 2000), such as self-focused competitiveness, offers insight into its role in social behavior and mental states. Hence, rather than focusing on a clustering of “symptoms” or suggested “attributes,” the evolutionary approach seeks the origins of compassion in the evolution of caring motives and behavior, which then allows for the identification of the phylogenetic journey of the algorithms and physiological systems that make caring-compassion possible (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2005a; Goetz et al., 2010; Carter et al., 2017; Porges, 2017; Uomini et al., 2020). This paper outlines a hierarchical, evolution informed, biopsychosocial approach to compassion which enables insights into how lack of care-compassion, particularly early in life, can underpin mental health problems and how cultivating compassion can operate as a psychotherapeutic process, and promote prosocial behavior (see also Weng et al., 2013; Seppälä, et al., 2017; Gilbert, 2020a). Evolutionary approaches address two key questions:

First is the study of its phylogeny:

1. Given that compassion is emergent from caring motivation, we can identify the evolutionary challenges of reproduction that gave rise to certain forms of caring for offspring behavior.

2. We can then explore the motives and algorithms that facilitate those parental, investing reproductive strategies and how they served as a template for other forms of caring and helpful behavior to evolve.

3. The evolution of motives and algorithms require physiological infrastructures to support them. In the case of caring and compassion, candidates include the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin and the methylated part of the parasympathetic nervous system called the vagus nerve and different neurophysiological circuits.

4. Over time, those algorithms recruit and possibly give rise to different types of complex competencies that include ways of reasoning, empathizing, and mindful awareness. Just as these can be recruited to advance any motive, they are utilized in the pursuit of compassion motives.

5. As a social mentality, compassion has a flow in that we can be compassionate to others, be open to the compassion from others and be self-compassionate. For the most part, each flow uses the same psychophysiology competencies.

Second is the study of its ontogeny:

6. Once the basic algorithms with their physiological infrastructures are identified, it is possible to explore how, over the course on an individual’s life, these motives and algorithms are stimulated, recruited, and become incorporated into processes such as self-identity. In essence, we are looking at the phenotype of the motive and in this case the phenotype of caring to compassion.

7. We can explore how motives like caring can recruit different types of emotion and cognitive competencies to cope with different types of context.

8. Like other motives, caring and compassion have facilitators and inhibitors that can be both external and internal.

9. Understanding these processes means that we can then begin to develop contexts and interventions that are specifically aimed to stimulate different contributing processes to compassion, such as identified physiological systems, cognitive competencies and behavioral training, and practizing certain types of meditation. These create a menu of interventions for people with mental health problems; for example, some clients may need particular help with developing vagal tone, others with becoming more empathic, others with fears and distrust of compassion, and yet others with experiencing caring motivation itself and (maybe) to tone down narcissistic self-focus.

10. By understanding these processes, including how motives can conflict with each other (e.g., for pursuing competitive self-advantage versus caring and sharing), we can create compassion focused and guided psychotherapies, education, businesses, and politics.

The basic challenges of life are survival and reproduction, and all living forms have three basic life tasks that give rise to three basic motives: (1) being motivated to avoid harm, injury, and loss; (2) being motivated to secure the resources necessary for survival and reproduction, including sexual access and infant caring; and (3) being able to tone down those motive systems when “resource satisfied” and “safe” to allow “rest and digest” (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2009a, 2020a; Thayer et al., 2012; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019; Workman et al., 2020). The bodily functions for rest and digest cannot proceed if the animal is under threat or is energized for resource seeking; thus, indicating co-regulating processes. The ability to downregulate physical activation through rest and digest has long-term impacts on illness vulnerability and mortality (Thayer et al., 2012). These basic life tasks promote what is called fitness; that is, success in passing genes for specific traits to subsequent generations. As noted below, different emotions are associated with these different life tasks and motives. Within those broad categories are a range of specific motives; for example, finding food and shelter, or in the social domain, competing with others, forming alliances, mating, and caring for offspring.

Different species evolve different (fitness promoting) strategies and ways of pursuing these motives. Primary motives require the organism to be alerted, orientated to, and respond to, certain kinds of stimuli/signal in specific ways so they can approach resources, but avoid threats and harms (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 1993; Panksepp, 1998). Motives also generate behaviors to seek out certain kinds of stimuli/signal. Hence, in order for a motive to operate, it needs an algorithm to guide it, to link stimulus and response. There is no point in being stimulus sensitive, interested, and orientated to (for example) food or sex if the animal does not know what to do. Lions are interested in antelopes as a food source, but if they do not have the foggiest idea of how to hunt or kill prey, they will starve. Evolving algorithms that enable motives to be enacted, therefore, have to have both elements. They begin as feature detectors that enable animals to identify and pay attention to (take an interest in) different kinds of stimuli in the environment, and then respond to those stimuli in appropriate ways. With brains that can learn, exact behaviors may depend on learning, such as lions learning how to hunt and kill and where the prey “hang out.” As noted later, the evolution of complex human cognitive competencies has introduced fundamental and profound new ways by which emotions and motives are triggered, pursued, and expressed.

Algorithms can be identified quite simply as stimulus-response dynamics of if A then do B. Nearly all processes in the universe operate on algorithms that are predetermined and give rise to the laws of physics and chemistry. One’s air-conditioning works on an algorithm of if the temperature goes above a certain level, then it turns itself on. If it goes below a certain level, it turns itself off. All that it needs is a feature detector (in this case) for temperature that links to the response function of the system. This is essentially the same way physiological systems are built. For example, the immune system operates such that if certain foreign agents are detected, then immune responses are stimulated. So basically, algorithms are what motives require to operate. Here are some examples:

➢ if a threat (e.g., predator) then activate arousal and run. This algorithm requires feature detectors for certain types of threat (this links to the preparedness hypothesis such that we are more likely to develop fears of snakes and spiders than electricity or cars which will kill more people). Once detected, it will then trigger physiological systems that enable the body to act to defend against the threat. Defenses can be active, as in running away, or inhibitory, as in freezing or depressive collapse.

➢ if food then activate approach behavior, salivate, and eat. This algorithm requires feature detectors for certain types of food, including internal awareness (hunger) of the need to eat, linked into physiological systems, such as digest once eaten, the body has systems (a gut) to digest and utilize food.

➢ if sexual opportunity then approach and engage in courting behavior and copulate. This algorithm requires feature detectors for certain types of sexual stimuli with physiological systems that prepare sexual organs for action. In some species, triggers are pheromones. For others, it is visual stimuli and sometimes linked to certain times of the year.

➢ if threatened by a more dominant other then escape, or if not possible, then display submissive behavior. This algorithm requires feature detectors for certain types of signal indicating a threatening, powerful, dominant other, and physiological systems that will switch on defensive behaviors, such as submissive hunkering down and eye gaze avoidance.

Now, we can come to the reproductive strategies that give rise to particular motives with particular algorithms for caring behavior:

➢ if signal of distress or need then engage in trying to alleviate it. This algorithm requires feature detectors for certain types of (distress/need) signals emanating from another (e.g., offspring). This requires identification of the offspring (kin vs. non-kin) and identification of the nature of distress or needs (e.g., rescue if in danger, feed if hungry, and thermoregulate if cold). Prevention can also be built into this to the extent that nesting, for example, will take place out of harm’s way (Geary, 2000).

Algorithms can become complex and branch into sets of interconnecting algorithms of “if A then do B, but not if in the presence of C,” or “only if in the presence of D.” What that means is that the system needs a feature detector for “C” and “D,” and then those algorithms can interact. Another typical example is sequenced algorithms, where there is a menu of options so that if one response does not work, another is triggered. For example, in most stress situations animals will first struggle to overcome a stressor but if that does not work then physiological systems automatically switch into a different response pattern which is often to go into helplessness or shutdown states (Overmier, 2002). Third, as noted below, the evolution of complex cognitive competencies has had profound effects on how these human algorithms, motives, and emotions work (Barrett, 2017; Gilbert, 2019).

Before proceeding, we can combine ancient, motive and algorithmic ideas to help define care and compassion (Gilbert, 2017a). In the Mahayana Buddhist tradition (Dalai Lama, 1995) and the evolutionary tradition (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2005a; Keltner et al., 2014), care and compassion are basic motives. Although CFT has defined care and its derivative “compassion” (see below) in slightly different ways over the years, we now try to stick closely to the basic “stimulus – response” algorithm of caring. Hence, the stimulus is some sign of suffering distress or core need that if not met creates suffering, which triggers a motivation and action to try to do something about them. As we will see, this algorithm is very ancient; the provision of care for the purpose of protecting, addressing needs, and supporting flourishing in offspring, can even be detected in fish (McGhee and Bell, 2014). Derived from an exploration of the evolution of caring behavior (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2005a, 2009a; Goetz et al., 2010; Keltner et al., 2014; Cassidy and Shaver, 2016; Mayseless, 2016; Melis, 2018) consistent with the Mahayana Buddhist tradition (Dalai Lama, 1995), compassion can therefore be defined as a basic algorithm of “sensitivity to suffering in self and others with a commitment to try to alleviate and prevent it” (Gilbert, 2014). The intention and focus of care-compassion is clearly different from other motives, such as competitive self-interest, cooperating, or sexuality (Gilbert, 1989/2016). Importantly, however increased sensitivity to suffering by itself can be associated with increased distress and depression (Gilbert et al., 2019). Hence, it is what we do and how we manage these feelings that is crucial.

However each of those motives can be enacted compassionately making compassion a ‘higher order’ motive. One other element to note is that although compassion tends to be focused on alleviation and prevention of suffering, CFT, and indeed other approaches, are broader than that and focus on caring behavior which also has the intent of addressing needs and promoting development and flourishing. This is partly why Choden and I introduced the concept of prevention, into the definition because if needs are not addressed, or support for flourishing is not given, then suffering is likely to follow (Gilbert and Choden, 2013). In the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, one of the major antidotes to mental suffering is enlightenment; that is insight into the nature of mind partly because that prevents suffering. So, the actions and training for prevention are implicited in this approach.

Identifying the evolved algorithms for caring behavior is difficult. For example, one of the roots for compassion is from parental caring behavior. However, many species demonstrate different aspects of caring behavior. For example, some fish show guarding behavior and will chase off predators. McGhee and Bell (2014) studied three-spined sticklebacks, where fathers provide the care and protection. They note that:

During the approximately two weeks that fathers provide care, they defend their nest from predators, fan the nest with their pectoral fins to provide fresh oxygen to the embryos and once the embryos hatch, retrieve fry that stray from the nest. During this period, offspring rely on yolk reserves provisioned by their mother prior to fertilization. Fathers do not feed offspring, but there is evidence that offspring antipredator behaviour …., mate preference …. and morphology …. can be sensitive to the effects of fathers (p.2)

They go onto discuss how paternal caring influences traits such as anxiety in offspring that impact their survival and how paternal caring influences the epigenetics of their offspring. Indeed, it is now known that across many different species, the quality of parental caring impacts epigenetics and can attenuate or amplify vulnerabilities to threat sensitivity (Cowan et al., 2016; Kumsta, 2019). What is also crucial here is that there are a number of different behaviors that constitute caring which may be regulated through different algorithms and physiological systems. Hence, a “father” fish may be good at (say) rescuing straying offspring, but less good at fanning the nest. As noted later, compassion can also be seen as made up of multiple different sensitivities and behaviors depending on context. People may be good at certain aspects of compassion, but not others.

Care of offspring is not the only source for the evolution of caring. Kessler (2020) explores the evolution of what she calls “health-care,” caring for sick individuals, and highlights that many species care for their sick and injured. Kessler refers to the work of Frank et al. (2018), who noted that termite hunting ants (Megaponera Analis) are prone to injury such as losing legs, but are often carried back to the nest by nest mates, where their chances of recovery are 80% compared to 10% of those who are not. Once healed, these ants can return to the group tasks. Kessler also highlights a range of evolved caring behaviors (e.g., grooming) whose function appears to be parasite and infection control. It is common that solutions that work in one species can independently evolve in other species. This is true for caring (Spikins, 2015, 2017; Uomini et al., 2020).

Identifying specific motives to care for the sick is interesting on two fronts. First, at times, this appears to be a specific type of caring and compassion, where individuals can be very motivated to care for the sick or those in danger, but not invest so much in their own families or close relationships. They spend more time in the hospital on duty or working for charities; public and social rather than intimate forms of caring (Gilbert, 1989/2016). To put this another way, some individuals may be specifically sensitive to signals of “sickness or danger” in others, or “committed to a cause” if there is a “danger to the physical body,” but less care and compassion orientated or competent when it is mental states or intimate relating.

Another “life challenge” that may have supported the evolution of caring and compassion is the degree to which certain traits are attractive to others and make individuals desirable as mates and allies (Goetz et al., 2010). It has been known for a while that females prefer altruistic over non-altruistic males, particularly for long term partners and to some degree “heroism” that could be used to protect (Margana et al., 2019). When it comes to forming friendships and reciprocal relationships that can be mutually beneficial, signals of caring, altruism, and trustworthiness also play a key role. Hence, evolving traits for caring is also evolving traits that have beneficial effects on one’s potential to be chosen as a sexual mate or cooperative ally (Goetz et al., 2010). Note, too, that context can play a big role for what and to whom we are compassionate. For example, in groups of fighting men, individuals who are fearful and somewhat avoidant maybe shamed and shunned, whereas fearfulness and avoidance is a central focus for compassionate psychotherapy. In general then, caring has evolved from different selective pressures with different feature detectors that distinguish different types of distress and need signals requiring different types of intervention (e.g., rescue, comfort, or feed).

Another evolutionary angle on the origins of compassion is through the concept of altruism. The evolution of altruism is typically seen to be driven by two processes: (1) kin-based, where caring behavior has a payoff for one’s genetic representation in the next generation and (2) reciprocal, where helping behavior will result in being helped in the future (Buss, 2015; Colqhoun et al., 2020). In a review, Preston (2013) offered the following definitions for altruism, which are very close to the concept of compassion.

Altruistic responding is defined as any form of helping that applies when the giver is motivated to assist a specific target after perceiving their distress or need “…..” Altruistic responding implies an active behavioural response initiated by the perception of need, which is differentiated from cooperative, diffuse, or unintentional forms of altruism that likely derive from other evolutionary and mechanistic origins… Altruistic responding further narrows these classifications to only include cases where the motivation to respond is fomented by direct or indirect perception of the other’s distress or need… This excludes cases that emerged later in time or include diverse processes, such as cooperation or helping influenced by strategic goals, social norms, display rules, or mate signaling (p. 1307; italics added).

For Preston (2013), the origins of altruistic responding are in the evolution of detecting and responding to (retrieving/rescuing) distress calls in infants – coming to their aid. Like CFT, she identifies passive and active forms of caring. Passive forms are providing soothing and comforting, whereas active forms are specific behaviors designed to rescue or alleviate distress in infants and require motor activation. Unlike compassion, this definition of altruism excludes the concepts of sharing or acts that focus on the flourishing and well-being of others or “general caring.” Helping people that does not have a cost or can actually benefit oneself in the long term is questionable as to how altruistic-compassionate it is (Colqhoun et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2020). Clearly, the ultimate benefit of kin-caring is the flourishing of one’s genes in the next generation, sometimes called inclusive fitness. Given that helping behavior is energy expensive, then one would predict far more of it will be given to kin relations and immediate reciprocating others than distal strangers. For the most part, this is exactly what the research demonstrates, that we lavish huge resources on our own children and kin even though we know many other thousands of children around the world will die every day as a result of lack of food, clean water, and simple vaccinations (Colqhoun et al., 2020). And, we are highly focused on our own groups even to the point of physiologically responding to pain differently if it is a member of one’s own group or a different group (Hein et al., 2010). Importantly, Richins et al. (2019) suggested that this empathy inhibition can occur if groups are in competition, but is less noted if they are not. This is an important finding because it indicates that one motive system, such as competitiveness, can change a range of processes such as empathic engagement.

Undoubtedly, humans are prepared to make sacrifices of their own lives to save others, and even strangers, as witnessed in many situations of the rescue services or medical staff working on viral infections around the world including of course Ebola and COVID-19. It is not entirely clear, however, when that kind of altruistic behavior evolved (Kessler, 2020). Nor is it clear when we develop the capacity to make sacrifices of giving up our own resources at a cost to ourselves. For example, although helpful behavior has been observed repeatedly in young children, most research has been when there has been no cost to them for helping. Green et al. (2018) investigated how helpful young children would be if there were a cost. They found that children would help a hand puppet achieve a goal of completing a task (e.g., puzzle) if there was no cost to them, but helping fell significantly when they had to give up something to help the puppet. Even when the puppet made appeals and was clearly distressed, the child still would not give up their own resources or rewards to help the distressed puppet; and even sometimes when they were clearly distressed at their own refusing to help behavior (Kirby personal communication). In a different paradigm, Miller et al., 2020 did find that four to six year olds were prepared to give up things important to them to help others and this was related to heart rate variability and also the child’s experience of maternal care and love. In other words, children growing up in loving and caring households are more likely to care and share with others.

Co-evolution is the way species evolve because of their interactions. For example, prey will evolve attributes (camouflage and escape speed) that enable them to escape predators. This drives predators to become better camouflage detectors and faster pursuers. Cleaner fish evolve in relationship to bigger fish; viruses and bacteria evolve ways to exploit the defenses of hosts. Social co-evolution, however, is different because of its focus on communication and social signaling as information flows between one or more individuals that have direct physiological impacts (Gilbert 2017c). For example, if infants evolve motives and competencies for distress calling, but parents do not evolve the motives and competencies to notice (be stimulus sensitive and “interested”) and respond in specific ways, evolution cannot progress along that dimension. Equally, if mothers evolved capacities for caring and soothing, but infants do not evolve capacities to be receptive and physiologically influenced by those signals, then again, evolution cannot proceed. Hence the relationship (e.g., kin vs. non-kin; friend vs. enemy) triggers the algorithm. Change the relationship and a signal of distress may not activate caring behavior (Mascaro et al., 2020). The quality and type of the relationship textures the processing of social signals. Hence, we can distinguish between non-social motives that do not require the evolution of complex social signaling processing and those that do. Avoiding heights or water (if one cannot swim) and finding food and building shelters are not social. Motives for competing, sex, and caring can only be successful where there is a contributing (not always willing) partner forming interpersonal, reciprocally dynamic dances. Hence, social mentalities are role focused, recruit different algorithms, physiological systems and cognitive competencies to engage in different interpersonal dances in the co-creation of different roles (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2005b, 2017c, 2020a; Hermanto et al., 2017; Mullen and O’Reilly, 2018; Brasini et al., 2020).

The co-evolution of the motives and competencies for forming many different types of social role (e.g., dominant-subordinate, sexual, caring, and sharing) has profoundly influenced the evolution of multiple physiological and structural processes. Lockwood et al. (2020) reviewed considerable evidence looking at the specificity of social behaviors and brain function which is very supportive of social mentality theory. In the case of caring, researchers have drawn attention to adaptations to the central and autonomic nervous systems that facilitated the co-evolution of care providing and care-seeking forms of relating (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2005a; Porges, 2007, 2017; Thayer et al., 2012; Brown and Brown, 2015, 2017; Carter et al., 2017). Not only has the evolution of caring behavior brought modifications to the central (Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005) and autonomic nervous system (Porges, 2017), for another example of the importance of specificities of processes underpinning social mentalities, consider Carter et al. (2009) discussing the evolution of the middle ear:

the middle ear permits detection of high-frequency airborne sounds (i.e., sounds in the frequency of human voice). Even when the acoustic environment is dominated by low-frequency sounds, the development of the mammalian middle ear also was critical in the evolutionary history of sociality because it allowed the mother to eat, nurse and listen to conspecific vocalisations at the same time (p.172).

In essence then, the middle ear in humans was driven (partly) by co-evolution for caring, rooted in social communication, and provided one essential competency for the evolution of speech. It is because social motives depend upon co-evolution and complex reciprocal, dynamic communication processes, they have been called social mentalities (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2005b, 2017c). The importance of decoding (from others) and sending signals to others (conspecifics) in complex interpersonal dances is hugely important because it gives rise to competencies for early forms of empathy and mind-reading (Lockwood et al., 2020; Luyten et al., 2020). In addition, these interactional “dances” have profound physiological impacts, including on epigenetic profiles (Cowan et al., 2016). Hence, many mammals can distinguish between signals of caring, signals of threat, signals of sexual interest, and signals of submission, etc., and will have evolved different responses for each. More specifically, they can distinguish between very different types of distress and suffering that require very different types of intervention and distinguish between different targets (e.g. kin vs non-kin).

The physiological infrastructures underpinning caring and compassion have been subjected to considerable research over the last 20 years (for reviews see Porges and Furman, 2011; Keltner et al., 2014; Brown and Brown, 2015, 2017; Mayseless, 2016; Gilbert, 2017a; Seppälä et al., 2017; Stevens and Woodruff, 2018). We know, for example, that the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin played vital roles in the evolution of caring behavior not only for infants, but also pair bonding (Carter et al., 2017). Variations in this gene may also link to variations in compassion and prosocial behavior (e.g., Tost et al., 2010; Marsh, 2019). Changes to the autonomic nervous system, particularly the myelination of the 10th cranial nerve of the parasympathetic system which evolved to become the vagus nerve, played a significant role in the regulation of threat and the soothing qualities of connectedness (Porges, 2007, 2017; Stellar and Keltner, 2017; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019). It now looks as if the parasympathetic rest and digest system, which regulates (sympathetic) threat and drive states, was incorporated into close relating enabling the signals emanating from a parent to have soothing vagal-mediated qualities on an infant (Porges and Furman, 2011; Porges, 2017). Indeed, different physical interactions of the parent to the infant (e.g., touching, holding, stroking, voice tone, and feeding and processes of intersubjectivity) have considerable but different physiological regulating effects (Hofer, 1994; Porges and Furman, 2011; Siegel, 2012; Cozolino, 2014; Schore, 2019). Supportive of mentality theory there is now considerable evidence that mother and baby can synchronise processes within their autonomic and central nervous systems. These synchronies can be thought of as symphonies and dances between their physiological systems that profoundly impact phenotypes for subsequent prosocial behavior and mental health (Lunkenheimer, et al., 2015; Nguyen, et al., 2020). Furthermore, there is good evidence that the vagus plays a major role in prosocial behavior and caring and compassion in general (Keltner et al., 2014; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019; Di Bello et al., 2020).

As noted above, offspring caring has been identified in multiple species including fish, avian and mammalian, and offspring are epigenetically affected by the quality of the care they receive (Cowan et al., 2016; Uomini et al., 2020). In many species, the interactions between the infant and primary care giver pertain to feeding, thermoregulation, rescuing, and comforting. These effect the maturation of different physiological systems, such as autonomic nervous system, neurochemistry, and immune function (Hofer, 1984, 1994; Brown and Brown, 2017). As a psychiatrist interested in human psychological processes and the development of mental health problems, Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) offered a functional analysis of the impact of parental care-giving/receiving relationships on psychosocial systems and development. He described three core functions associated with what he called attachment (see Cassidy and Shaver, 2016; Music, 2017 for reviews). As noted below, each of these three functions are very important functions of compassion too. When developing a compassionate mind or turning to a compassionate other they are central. These are:

1. Proximity seeking/maintenance relates to feature detectors for access and availability to a caring other, staying close to each other for protection and care, and if lost to find and rescue, and if hungry feed. Many physiological systems are maturing in the context of this close, interpersonal connectedness that can be disrupted with ruptures to that closeness (Hofer, 1994; Wang, 2005; Siegel, 2012). Hence, part of proximity seeking and maintenance is to support maturational interpersonal dances. These are impacting physiological levels, brain development, and epigenetics (Cozolino, 2014; Cowan et al., 2016), and a range of psychological competencies (e.g., empathy) are all developing in this context of closeness (Siegel, 2012; Cozolino, 2014). Indeed, throughout life, the way we maintain our proximity to each other, touch each other, smile, and joke with each other, show affiliation, speak with each other (even on the phone and Zoom), help each other, have fundamental impacts on a range of physiological systems (Cozolino, 2014; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019). We are a physiological, co-regulating species.

2. The provision of a secure base provides an environment free from threat, where infants can explore and learn; the parent acts as the “eyes for threat” and “guards the child” allowing the child to focus attention on exploration, play, and learning. As a secure base, the parent “mediates” the world for the infant, titrating threat exposure, guiding discoveries, and promoting skills development with developmental needs for learning (Gilbert, 1989/2016; Cassidy and Shaver, 2016). This is similar to aspects of a working therapeutic relationship (Holmes and Slade, 2017). Along with guidance, a secure base is also a source of encouragement and inspiration. In the context of a secure base and caring parent, the child experiences playful, joyful, exciting, and affectionate interactions (Schore, 2019). They learn that they exist positively in the minds of others and that others love and like them, and hence develop (positive) internal working models of self in relationship to others (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 1992a; Cassidy and Shaver, 2016; Music, 2017). Out of the complex melange of varied and multipurpose interactions comes our ability to trust others. The more we experience others as providing a secure base for us, the more we trust them, and the more we trust them, the more they are able to provide a secure base of encouragement and guidance (Fonagy et al., 2017). As we grow, our secure base extends to networks of peers and other individuals (Hrdy, 2009; Narvaez, 2017, 2020). Importantly too, a secure base sets clear boundaries for participants in the relationship enabling predictability, but also maintaining respectfulness and care for participating individuals. A secure base is not overly permissive or allows disrespectful or destructive behaviors, or gives in to every “want.” A child who has not learned age appropriate respect for others or impulse control is problematic. This is true in social networks in general. Part of creating secure bases in communities is to have a very clear system of laws, and encouraging citizen respectfulness as a central social behavior.

3. A safe haven is where the parent acts as a soothing and emotion regulating other, particularly but not only when the infant-child is distressed. Humans are biologically setup to expect and need emotion regulation to come from the outside and they are physiologically prepared to respond to that – indeed throughout life the care of others can sooth us. Whereas a secure base is partly about stimulating, encouraging, and inspiring, as well as approving and admiring, a safe haven in some ways is the opposite. This is the ability to be soothing and calming often in the context of high arousal, usually threat, but sometimes overexcitement or impulsiveness. Evidence suggests that a lot of safe haven functions operate through the rest and digest system and, in particular, the myelinated vagus nerve, a view developed by Porges (for a review see Porges, 2017; Stellar and Keltner, 2017). In his classic terry cloth (no food) vs. wire (with food), mother surrogate studies in primates, Harry Harlow showed that it was physical contact rather than feeding that was the crucial stimulus for soothing (for review see Harlow and Mears, 1979). So soothing stimuli and secure base stimuli are different, and therapists need to guide clients to that awareness so that they can distinguish between them. In other words, when distressed, some aspects of caring and compassion will be about encouraging, supporting, validating, and guiding into and not away from areas of difficulty, whereas others will be about soothing and containing physical distress. It is incorrect to see caring and compassion in CFT as only linked to safe haven function and not secure base function.

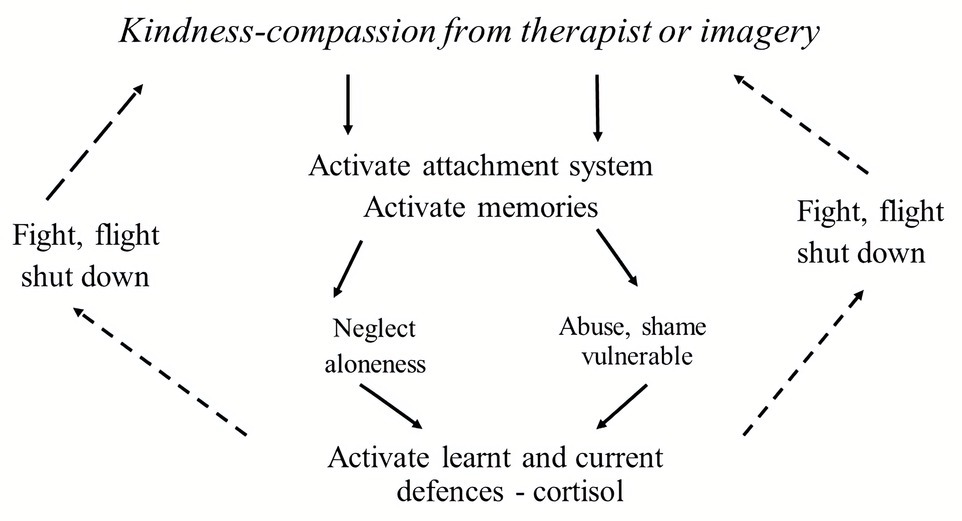

Attachment theorists highlight that if one has experienced these in early life, they become internalized such that we can provide them for ourselves (Cassidy and Shaver, 2016). Hence under stress, we remember to “internally proximity seek;” that is we can be sensitive to our distress with a capacity to tune into and generate an inner sense of soothing (safe base) and self-reassurance and encouragement (secure base). So, vital are these inputs to the infant and child, that failure to receive them, or worse experiences of threat and abuse in early life, reset strategic orientation at a phenotypic level (Cowan et al., 2016; Del Giudice, 2016; Kumsta, 2019; Slavich, 2020). The consequences of insecure attachment history have been well-documented and are known to be major sources of mental health problems and anti-social behavior later in life (for reviews see Music, 2017; Lippard and Nemeroff, 2020). In people with mental health difficulties, these inner abilities to provide themselves a sense of secure base, reassurance, and safe haven as in grounding and soothing are often weak or absent. In their place are forms of hostile self-criticism which amplify (sometimes drastically), rather than dampen threat processing (Gilbert and Irons, 2005; Castilho et al., 2017). In other words, when we are distressed, suffer setbacks, or disappointments rather than having an internal secure base and safe haven, we activate the threat system through harsh self-criticism (Gilbert and Irons, 2005). For those with anti-social problems, the focus is on stealing exploiting or harming others.

Increasingly, many therapists have been influenced by attachment theory and understand the importance of creating a secure base and safe haven (Gilbert, 1989/2016; Rothschild, 2000; Van der Kolk, 2015; Holmes and Slade, 2017). Indeed, for some traumatized clients, this is an essential therapeutic endeavor. Importantly, however, is to recognize that feeling safe is different from safety and that both are important, and that in the early days efforts to help people feel safe, for example, trying to stimulate the vagus nerve, might actually make them feel more anxious. See below on fears, blocks, and resistances. It is crucial therefore to distinguish safety from safeness as the latter is more tricky than the former.

Many forms of mental health difficulties are linked to the way individuals are subjected to, monitor, process, and cope with threats (Gray, 1987; Gilbert, 1989/2016, 1993; Rachman, 1990). This puts threat management center ground to most therapy (Rachman, 1990). CFT distinguishes two quite different basic systems involved with threat regulation and explorative behavior (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 1993, 2000, 2009a). Gray (1987) described a threat focused, behavioral inhibition system (BIS) that is triggered by signals indicating punishment and reduction in rewards (losses) and unexpected or novel stimuli. General levels of threat arousal can influence the degree of threat monitoring. These can activate the responses of the BIS which are: increased arousal, focused attention, and behavioral inhibition. Part of what anti-anxiety drugs and therapies are designed to do is to tone down sensitivity in the BIS. In contrast, is a behavioral activation system (BAS) linked to drive and resource seeking behaviors. It is triggered by signals of reward/resource, an absence of punishment and when activated individuals show higher levels of goal seeking behaviors and positive emotions (see Carver, 2004 for a pros and cons discussion). Various therapies seek to build these too.

Riskind et al. (2012) highlighted that the degree of threat people experience is related to the degree to which they see threat as “looming,” in terms of different types of distance, such as physical and temporal distance and probability of arrival. Individuals also make calculations on the degree of danger and harms and if they can be offset, prepared for, or avoided (Mobbs et al., 2009). All of these can be related to safety seeking and harm prevention or damage limitation. Attentional sensitivity and coping behaviors operate through the physiology of the threat system such as the amygdala, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and sympathetic nervous system (Gray, 1987; Panksepp, 1998). So, we have a sense of safety when the threat system is not picking up on threats, and therefore, is not being stimulated (although is ticking over in the background). This is sometimes called the smoke detector principle (Nesse, 2019), although that does not capture the dimensionality of threat (a little vs. a lot). This is depicted in Figure 1.

In everyday life, it is important that we pay attention to safety behaviors, such as putting on our car seat belt, COVID mask, or taking the vaccine. The focus on safety is prevention of harm. While many animals will need to balance threat against opportunity (seek for food in predator environments), the safety seeking system can be constantly “braking” or interrupting explorative behavior to stay vigilant. Watch feeding animals in the wild. Some have argued that interhemispheric differences in the brain evolved to enable animals to engage in activities like feeding while at the same time attending to and keeping “an eye open for threats” (McGilchrist, 2018). McGilchrist argues that the constant conflict between threat vigilance and securing resources was the source of hemispheric differentiation and lot of emotional difficulty, partly because the two hemispheres process information quite differently with quite different functions. Indeed, studies of people who have had their corpus callosum-lesioned, because of epilepsy, have shown that these two parts of the brain can make quite different decisions (see also McGilchrist, 2018; Schore, 2019). Clients who get stuck in the threat monitoring system can live (aspects of) their lives with elevated vigilance “to looming threat” (Riskind et al., 2012).

Figure 1 is reasonably self-explanatory. It simply shows that in the absence of threat signals the threat system remains low key, but an absence of threat will not necessarily promote exploration, play or positive social engagement. A detected threat will activate the threat system and then will suppress other behaviors not related to dealing with threat. There are obvious individual differences in the degree to which people monitor for both ‘the presence and absence of threat’. There are of course many other ways in which we can have a sense of safety and regulate the BIS. The BIS might have become oversensitized, due to difficult childhood experiences or be regulated through learning skills we have confidence in. Imagine how you might feel if someone threatens you, but you are a Bruce Lee super karate expert. Having an internal model that we can cope with certain threats obviously influences our monitoring (Mobbs et al., 2009). CFT and other therapies try to help people shift out of inappropriate vigilant and safety seeking motives, by developing confidence to appropriately assess threat, and the courage to tolerate and manage threat (Rachman, 1990; Riskind et al., 2012). This then enables a shift in the BIS-BAS balance and be able to pursue behaviors and build relationships that are more enjoyable, but also engage the rest and digest system more functionally. But the awareness of threat itself is not sufficient for us to understand threat regulation.

In 1989, I suggested another dimension for threat regulation that I called the safety system (Gilbert, 1989/2016, p. 88). Using the same reasoning as Gray, of identifying the algorithm in terms of its triggers and responses, I suggested the system was triggered by cues of no threat and also cues (as in attachment theory) of supportive others. However, one did not need to have an attachment relationship with others, but to see others as supportive and helpful. Early background would lay the foundations for openness to these social communicative signals and stimuli. These signals and stimuli did two things. They: (1) deactivated the threat-defense system and (2) promoted reward/resource seeking and affiliative behavior. The creation of friendly relationships then became self-reinforcing such that affiliative relationships activated safety and the positive rewards/emotions of feeling safe increased the orientation toward affiliation. Prosocial behavior, therefore, was a way of creating interpersonal relationships that were mutually pleasurable and beneficial. Sending signals of safety and safeness to each other have major physiological impacts (Gilbert, 2000; Porges, 2007; Petrocchi and Cheli, 2019).

I had opportunities to discuss the issue of social versus non-social stimuli with Gray and how that related to his BAS and he offered some very insightful concepts. I used them in Gilbert (1993). By 1993, the distinction between safety and safeness was becoming more apparent, and so in 1993, I referred to the system as a safety/safeness system, but still lumping the two functions (monitoring absence of threat and monitoring presence of support cues) together. It was the late primatologist Chance (1988), who became a colleague and who on reading my paper on safety and threat (Gilbert, 1993) advised me that I needed to more clearly separate these functions. We discussed how there is big differences between threat vigilance (absence of threat) and feeling safe. These differences were likely to be physiological as well. He used the example of group behavior. In any group which is competitive or where there is a hierarchy that is potentially punitive (common in many primates), individuals focus on safety by ensuring they do not behave in ways that stimulate conflict with those more powerful. The group looks stable, but this is basically what he called an agonic mode, stability through threat and submissive wariness and defense. Families or groups with threatening or bullying parents/bosses can be like this. Levels of stress arousal tend to be high. However, when relationships are friendly and people can trust each other to not be attacking but supportive, the whole group settles into a very different structure of attention and shared physiological arousal; here, there is much more openness and sharing. He called this the hedonic mode. Safeness was when the environment is caring, supportive, helpful and friendly and creates these states of open attention. One of the transitions from primate to hunter gatherer in humans was partly moving away from aggressive hierarchies into hedonic mode type group relating (Boehm, 1999; Ryan, 2019). Ten years later a fascinating, natural event reflected Michael’s view. Robert Sapolsky and team (Sapolsky and Share, 2004) had been studying a group of baboons when some of the dominant males ate from a poisoned rubbish dump and died. This left the group with relatively less aggressive males and females and the group then settled into a much more relaxed state noted in patterns of grooming and general levels of arousal (lower stress) which was maintained even with other males migrating in.

I remain fascinated in how to integrate attachment theory and safeness concept into compassion concepts. Sometime later, I discovered that Steven Porges had explored the functions of the vagus nerve and outline the evolution of what he called a social engagement system, which is very similar to the social safeness system. Articulating very carefully the role of the myelinated vagus nerve, it became known as polyvagal theory (Porges, 2007, 2017). In CFT, we tend to stick with the concept of social safeness rather than engagement, because one can socially engage for all kinds of reasons (Kelly et al., 2012; Armstrong et al., 2020). However, there is a lot of overlap between the two approaches. So, this brings us back to the evolution of how to create a secure base. This is partly created by recognizing boundaries but also by experiencing the friendliness and helpfulness of those around you. This promotes exploration because one is not vigilant to threat; and one’s exploratory behavior is not constantly being interrupted by having to check out on threat. When one feels safe, one has relaxed attention, can explore and play. Social relating are positively rewarding and enticing. This also provides the basis for integrative thinking and learning. Clearly, this is a state you want to create in therapy.

We can explore the concept of safeness and how different it is from safety with attachment theory. Bowlby (1969, 1973) suggested that attachment systems are evolved to work on threat in a different way. The mother acts as a signal of safeness that the child moves toward rather than away from. She is a source of food comfort and protection and when the infant avails themselves of these resources, this stimulates positive reward centers, not threat ones. As a result of different types of repeated interactions such as physical closeness, feeding, thermoregulation, touch/comfort (Hofer, 1984, 1994) the mother is stimulating oxytocin-endorphin-parasympathetic circuits (Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; Lunkenheimer et al., 2018). Over a number of years, Porges (2017) has delineated the special role of the vagus nerve in these functions. What this means is that in her presence, these systems are active and will be suppressing threat system processing. As long as the infant has access to her (or primary care giver) then the infant has access to food, comfort, thermoregulation, protection, guidance, etc. Crucially for CFT, these lay down internal working models such that we can provide them for ourselves; in essence that is the basis of self-compassion to function like a good parent to ourselves and stimulate these oxytocin-endorphin-parasympathetic links when we need to.

A number of early classic experiments showed that when a reliable parent is present, children will show positive affect, curiosity, play, and engage in explorative behavior (see Cassidy and Shaver, 2016 for reviews), what Chance (1988) called a hedonic mode of interaction. In addition, the parent may support, encourage, and guide these behaviors. This is clearly not the case if it is simply a safety vs. threat regulation processing issue; affiliative play is not a part of that. If the parent becomes unavailable or separated (e.g., leaves a room), there may be no actual threat in the room, yet this immediately releases threat system processing and the infant’s motive is then searching for the safe-providing object (mother; see Siegel, 2012; Cozolino, 2014; Cassidy and Shaver, 2016; Schore, 2019 for reviews). In other words, the presence of safeness signals (a trusted parent) suppresses threat system processing, and in so doing, can bring other systems online such as explorative play which in turn can build affiliative relationships. Hence with their removal (mother goes out), this releases the threat system from its inhibition and orientates the child to now pay attention to the (evolutionary important) task of threat vigilance and seeking the return of the safe object. These processes are depicted in Figure 2.

The key element implicited in the mode approach of Chance (1988), attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969), and social mentality theory (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 1992b, 2000) is the process by which the presence or absence of “safeness” signals facilitate, release from inhibition, or suppress threat processing. Individuals who are prone to anxiety and stress, therefore, are not just experiencing facilitators of threat processing, but also the lack of inhibitors of threat processing such as access to caring and support from others or self.

This issue showed up in another way. Wanting to see if we could develop a scale that would tap different types of positive emotion, particularly those linked to excitement and achieving versus linked to rest and digest and “chilling out,” Gilbert et al. (2008) developed a short self-report questionnaire to tap these different dimensions of positive emotion. While excited/energized types of positive emotion formed a separate factor to that of soothing and calming emotions, what we had not anticipated is that relaxed, positive affect is different to “feeling safe” and contentment positive affect. Importantly, the latter was more powerfully linked to mental health issues. This again suggests that experiences of safeness overlaps with, but are not the same as, rest and digest, but rather link to a sense of social safeness and connectedness (Kelly et al., 2012). This was also found by Matos et al. (2018). In other words, when people feel safe, particularly as provided by social contexts, they may feel content which quells excessive resource seeking and threat focused behaviors (Cordaro et al., 2016). Armstrong et al. (2020) found that feelings of safeness could be seen as a separate type of positive emotion that can blend with playfulness or relaxation.

When people feel “socially safe” they are not necessarily in calm, relaxed, or low arousal states, but could be playful, curious, and enjoying social events like parties and further developing relationships with friends and lovers. Keltner et al. (2018) also review some of the subtleties and differences in the autonomic nervous system relating to subtle variations in positive emotions such as awe, excitement, love, and contentment. Indeed, we could argue that many aspects of joyful social relating from sexual encounters through to going to parties, sharing jokes are examples of creating and experiencing social safeness. It is these dimensions of caring that are so essential for creating these interpersonal experiences that regulate our states in mind. Knowing that people care about you, and will address your suffering and distress if needed, helps to create a sense of safeness and builds trust and closeness.

There is considerable research showing that safeness signals downregulate threat. For example, Heinrichs et al. (2003) showed that when subjected to certain types of social stress, a person’s level of cortisol is influenced not only by oxytocin, but also by the presence of a friend. In a priming experiment by Norman et al. (2015), participants were shown “48 pictures depicting caring behavior and individuals enjoying close attachment relationships, such as hugging loved ones” (p. 833). Control subjects were shown pictures of household objects. Being primed with sharing and caring relationships had the effect of attenuating amygdala responses to threat stimuli from facial expressions and dot probe. Kumashiro and Sedikides (2005) showed that people were much more likely to engage with, and be curious about, negative feedback on a task if they had been previously primed with bringing to mind close positive relationships. Hornstein and Eisenberger (2018) did not distinguish safeness from safety, but nonetheless show that what they are calling safety signals, and what I am calling safeness signals, can have powerful impacts on the acquisition of fear and the extinction of fear. Recently, Gillath and Karantzas (2019) provided an extensive overview of the forms and effects of attachment priming. They found that priming attachment security [or what we refer to here as “caring other(s) and social safeness”] studies have used different methodologies, including subliminally and supraliminally exposing people to security words, such as affection, love, and support, names of attachment figures, and pictures of people hugging a child, thus recalling memories of being loved and supported. Priming people in attachment security (or social safeness; Kelly et al., 2012) impacts positively on how people process a range of potentially threat-based scenarios, including tendencies to make them more pro-social. Kelly and Dupasquier (2016) found that student population experiences of social safeness and sense of connectedness mediated the relationship between recalling parental warmth, and the degree to which individuals were fearful of being self-compassionate or being open to receiving compassion from others. It would appear that for us to be able to use compassion, it helps if we have experienced it in our primary relationships.

Signals indicating safeness can also relate to one’s community (e.g., feeling we live in a safe-helpful neighborhood or with safe and supportive neighbors). Keep in mind that these are not just communities that are low threat, but also communities providing a sense of social connection and mutual support; sometimes also seen as social capital. Social safeness is a powerful predictor of well-being, even more than positive and negative effects (Kelly et al., 2012). CFT distinguishes between social safeness and non-social safeness in the sense that being wealthy, and having money easily available, makes the world feel safer than if we are poor. Some forms of an over-reliance on seeking social safeness, however, can be problematic as in those individuals who have what are called dependency problems and who become anxious without access to helpful others; or those who use wealth to feel safe, but want more and more.

Recently, Slavich (2020) wrote extensively on what he called social safety theory linking a whole range of physiological systems and their interactions including: the immune system, hypothalamic pituitary adrenal stress system, the vagus nerve, the lymphatic system, and frontal cortex as very sensitive to an individual’s safety. Indeed, it is another facet of the importance of how various phenotypes, developed in safe versus threatening social environments, can channel individuals to quite different strategic orientations in life. However, a distinction between safety and safeness would help to clarify these processes. What are the physiological effects of being in a relatively low threat environment and how might these be different in a socially enriching, fun, caring, and supportive environment? Although calling it safety rather than safeness, Slavich has offered major new insights into the importance of social safeness and social connectedness (Kelly et al., 2012; Armstrong et al., 2020) on the regulation of multiple physiological systems.

To cut a long story short then, when looked at physiologically, removal of a threat versus the presence of safeness stimuli regulate threat processing via different physiological systems. Especially important is that some degree of a secure base and sense of safe cues of safeness and helpfulness build courage. We cannot build courage by trying to remove ourselves from the source of threat (avoidance). Hence, whereas the absence or removal of a threat stimulus will deactivate threat processing, the presence of affiliative and social safeness signals stimulate the oxytocin-opiate circuits, vagus, and have soothing and/or encouraging qualities (Depue and Morrone-Strupinsky, 2005; Carter et al., 2017). Note, too, how research on “lovingkindness” has powerful and direct effects on threat processing systems. Weng et al. (2018) showed that such meditation practices changed the sensitivity in amygdala to threat signals. It is partly because clients use avoidance as a way of regulating threat, rather than developing courage to tolerate and engage with it, that problems escalate for them (Rachman, 1990). Repeatedly then, CFT tries to help clients build the psychological and physiological infrastructures for creating an internal sense of safeness, secure base, and safe haven. Bratt et al. (2020) explored the experiences of adolescent girls with CFT. One of the central experiences for them was “gaining courage to see and accept oneself.”

On a neural level, secure versus insecure attachment styles have been shown to moderate the degree to which individuals engage in self-criticism during fMRI. Specifically, at greater levels of an amygdala response during self-criticism (i.e., threat), individuals higher on secure attachment measures have greater neural response within the visual cortex, as a potential marker of engagement in imagery than those with lower scores (Kim et al., 2020a). Importantly, this effect was not observed for individuals with higher avoidant attachment scores. This may indicate that an avoidant attachment style is associated with a greater tendency to disengage from the threat of self-criticism, whereas secure attachment is associated with the ability to tolerate the threat of self-criticism. This may explain why an avoidant attachment style is associated with criticizing others rather than criticizing self (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2016). In addition, people who see themselves as superior tend to blame others rather than themselves for their difficulties (Gilbert and Miles, 2000).

As we have come to understand these processes, therapies are now targeting them in a kind of neuropsychophysiotherapy (Gilbert, 2000, 2009a, 2010; Cozolino, 2017; Fiskum, 2019). For example, compassion training has been shown to produce changes in the autonomic nervous system as measured by heart rate variability (Matos et al., 2017; Di Bello et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020c; Steffen et al., 2020) in the immune system (Pace et al., 2009) and in various cortical areas (Weng et al., 2013, 2018; Singer and Engert, 2019; Kim et al., 2020b). Useful too are compassion scales developed to measure both positive levels of compassion engagement and action (Gilbert et al., 2017), and fears of compassion (Gilbert et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2020b) are also sensitive to detecting changes in HRV (Di Bello et al., 2020). Put simply, research is finding that the higher one is in compassion engagement and action the better their HRV, but the more fearful they are of compassion the lower their HRV. In addition, Singer and colleagues (e.g., Singer and Engert, 2019) have shown that specific types of interventions such as mindfulness, empathy, and compassion, stimulate different neurophysiological systems.

One of the early observations that inspired CFT was finding that while working with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), clients could sometimes generate helpful thoughts to counteract negative, self-accusatory, and attacking ones, but these were not always helpful. When I asked a particularly severely depressed client to speak out her “helpful” thoughts as she actually heard them in her mind, her emotional tone was aggressive and contemptuous. Helping her begin to develop a compassion motivation and genuine caring emotional textures to her depression, life tragedies and internal dialogues proved a lot more difficult than I had anticipated. I began to explore the same issues with other clients and sure enough they could generate coping thoughts with helpful content but not with any sense of a compassionate motive or emotional texture. Many clients found that even talking to themselves in a compassionate, sensitive, and caring way is very difficult. Pauley and MacPherson (2010) explored the reasons they found self-compassion difficult. In addition, being open and moved by the compassion of others was also difficult to believe, feel, or trust. This led to an exploration of how and why developing motivation, intention, and emotional textures of caring and compassion can be so difficult for some yet be such a powerful antidote for mental health problems. It also reaffirmed the centrality of that motivation for any intervention (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2000). Part of the explanation involved understanding the function and psychophysiological mechanisms underpinning care motives, compassion and their fears, blocks, and resistances (Kirby et al., 2019). For the most part then, CFT was developed with the more complex and chronic mental health problems and was guided by many of the experiences and recommendations for development that clients offered on their journeys that have improved therapy (Gilbert and Procter, 2006). The therapist uses psychoeducation so that the client has clear insight into why they are doing the practices, particularly in terms of developing different competencies, and brain and body states they might not have had a chance to develop in childhood.

Having explored the evolution of care and the specific functions of care on psychosocial development (which is to provide a secure base and safe haven which in turn sets up an internal regulation of threat by the cultivation of a safeness system or process), the rest of this paper will explore how these insights can be used to guide and support psychotherapy. While many CBT therapies focus on helping people deal with threats fairly directly and often helpfully, this is mostly by working with the threat system itself either through exposure or cognitive change. CFT, however, seeks to work with basic motivational systems and, in particular, how to create inner capacities for feeling supported, and hence able to activate “safeness processing” and to develop mutually supportive, prosocial, and caring relationships, and to live ethically.

This paper does not have space to outline the various interventions and processes of training for developing compassionate mind states and competencies (Gilbert and Choden, 2013; Gilbert and Simos, in press). Simply to say that there are a range of practices and interventions such as breathing practices that stimulate the vagus, a range of different visualizations and meditations, exploration of compassionate reasoning, and compassionate behavior, some of which are guided by understanding the physiological underpinnings of caring compassion. Particularly, important is for clients to begin to understand how to create an inner sense of a secure base and safe haven that counteracts (among other things) shame and self-criticism which they can turn into when distressed and also utilize as a source of encouragement and guidance. These are related to what we call the compassionate self, mind and the compassionate image.

To explore how compassion fits into psychotherapy, we need to explore briefly the different dimensions of functioning that give rise to mental suffering and how care and compassion motivation reorganizes these processes. It is extremely important that therapists do not see working with compassion as a simple a “add on,” but understand how it is used to change the organization of the processes we are going to discuss; ultimately, we need to be able to have long-term physiological impacts (Cozolino, 2017; Schore, 2019; Steffen et al., 2020) and turn states into traits (Goleman and Davidson, 2017).

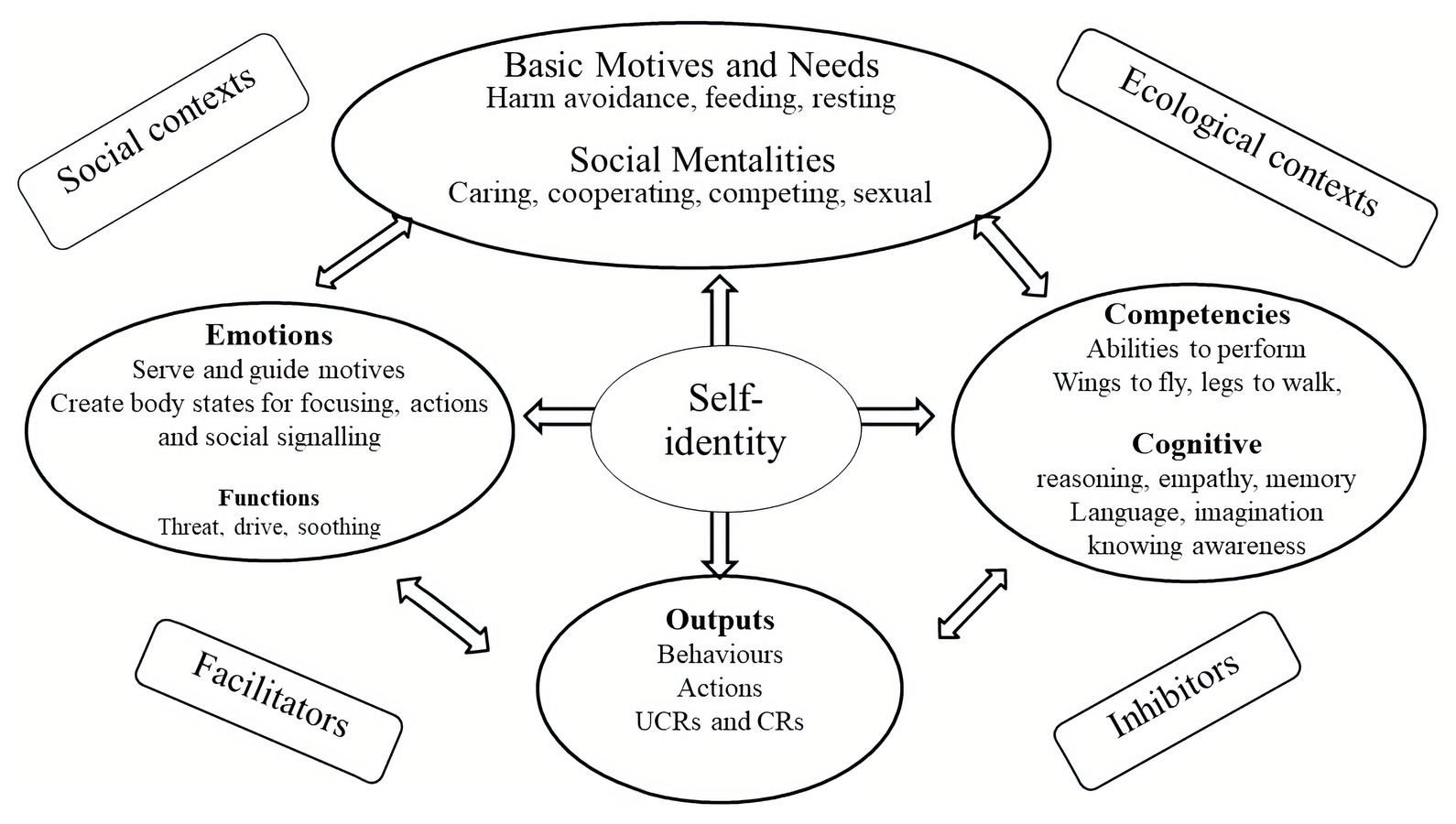

People seeking psychotherapy for distressed states of mind present with many different types of difficulty. Psychotherapists require some overview of the domains of functioning that will become a focus for intervention. In addition, articulating different domains of function enables description of how these functions operate in a motivation such as compassion. Taking the basic psychological science approach, CFT focuses on four main domains: motives, emotions, competencies, and behaviors (Gilbert, 1989/2016, 2019). These are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Mapping the mind. Adapted from Gilbert (2019).

From an evolutionary point of view motives run the show. All life forms are faced by three major life tasks which provide the basis for motives. These are: (1) motives to avoid harm, injury, and loss; (2) motives to acquire social and non-social resources promoting survival and reproduction; and (3) motives to rest and digest when not defending against threats or needing to pursue resources. As noted below, CFT refers to social motives, to create certain types of role relationships as social mentalities. This is partly because they have to co-evolve and create complex interpersonal dances; e.g., between carer and cared for, sexual partners, co-operators, dominant and subordinate, leader and led. Motives are also linked to needs such that we obviously need to eat and (early in life) to be cared for, have a sense of belonging and be able to compete for our share of resources and status (Gilbert, 1989/2016; Neel et al., 2016). If these relationships are compromised, if we feel excluded or rejected, unloved or unwanted, marginalized, oppressed and subordinated, we will suffer. These types of unmet needs or overdeveloped pursuits (e.g., for power) are often a focus in psychotherapy. One of the crucial insights that we have been aware of, even before Freud, is that the mind is full of conflicting motivations, emotions, and beliefs which can be very difficult to understand or regulate (Gilbert, 2000). CFT helps clients to recognize that behind any decision, there can be many different motives. For example there are often motives for, getting married or divorced or changing jobs. Therapists can plot these out in a ‘mind map’.

In many situations, we are often confronted with opportunities to be caring, sharing or self-focused, acquiring, and achieving. Indeed, the more competitive we see the world, and our need to keep up, the less compassion we may have (Piff et al., 2018) and the more vulnerable to mental health problems (Curran and Hill, 2019; Gilbert, 2020b). This is partly because competing for resources immediately opens up the potential of threat from competitors, but also failing. Importantly, whatever the source of our suffering and mental anguish, if we can activate a care focused and compassion motivation system, this will organize our minds in such a way to make it easier to deal with our suffering. Using the definition above, this means that as we shift into care and compassion motivation, we are oriented to be sensitive to ours and other peoples’ suffering; try to turn into it, not away from it, understand it, and then work out the best way to be helpful. This is clearly different from trying to avoid being sensitive to the suffering of self and others, or trying to suppress it, or becoming callous and indifferent. There is increasing evidence that social pressures to be competitive also increase callousness (Piff et al., 2018).

One of the major reasons people come to therapy is because of what they feel, that is problems with their emotions and their moods (Greenberg, 2003). While there are many varieties, textures, and approaches to emotions, taking an evolutionary functional approach, Nesse (2019) suggests that “Emotions are specialized states that adjust physiology, cognition, subjective experience, facial expressions, and behavior in ways that increase the ability to meet the adaptive challenges of situations that have reoccurred over the evolutionary history of a species” (p. 53). Basically, emotions serve motives and prepare the body for certain types of action and cognitive focus. CFT uses an evolutionary clustering of emotions by function approach. The main functions are as supports for primary motives noted above: (1) threat and harm avoidance, (2) resource seeking and acquiring, and (3) rest and digest and soothing (Gilbert, 2005a, 2009a, 2014). Hence, we have emotions that will help us take actions to defend ourselves (anger, anxiety, and disgust); emotions to help us to seek out and repeat behaviors that bring in resources and rewards (joys, fun, and various pleasures), and emotions that allow us to settle, rest, and recuperate (safeness and peaceful contented).