94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 08 October 2020

Sec. Organizational Psychology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576768

Peng Wang1,2,3†

Peng Wang1,2,3† Pengpeng Chu1

Pengpeng Chu1 Jun Wang1

Jun Wang1 Runsheng Pan1

Runsheng Pan1 Yu Sun1

Yu Sun1 Meng Yan1

Meng Yan1 Longzhen Jiao1

Longzhen Jiao1 Xiangping Zhan1*

Xiangping Zhan1* Denghao Zhang2,3†

Denghao Zhang2,3†Utilizing the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model as the theoretical framework, this study examines the relationship between job stress, job burnout, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment among 1,906 university teachers in China, and investigates teachers’ differences across groups. The result of SEM indicates that job burnout and job satisfaction could play mediating roles between job stress and organizational commitment. The result of multi-group analysis shows that for national university teachers, the positive effect of job stress on job burnout is the highest among three types of university teachers, the negative effect of job burnout on organizational commitment is lower compared with provincial university teachers and the negative effect of job burnout on job satisfaction is lower compared with provincial university teachers. Only for provincial university teachers, the job stress can significantly positively predict organizational commitment, and the independent mediating effect of job burnout is significantly greater than job satisfaction. The practical advice to enhance Chinese university teachers’ organizational commitment was provided in the end.

Since teachers experience a great deal of stress during the course of their careers, teaching has long been considered a high-stress occupation (Johnson et al., 2005; Noor and Zainuddin, 2011; Liu and Cheung, 2015). For academic personnel, stressors include high pressure to publish and task-role balance management put extra burden on their shoulders (Graça et al., 2020). This situation can be even harsher for Chinese university teachers due to the ambition of building more world-class universities (Zhu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). According to a survey conducted among Chinese university teachers in 2013, more than 36% of young teachers reported that they were facing great stress, and job stress has been a critical negative factor affecting their job satisfaction (Liu and Zhou, 2016).

To understand the generation mechanism of job stress and its influence, we introduced the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Demerouti et al., 2001), which is an overarching model that may be applied in teacher group (Bakker et al., 2005) and Chinese culture context (Hu et al., 2016). The JD-R model posits that the characteristics of a job can be classified as either job demands or job resources, which are the antecedents of job burnout and engagement. In addition, this model assumes dual different underlying psychological processes of work: a health impairment process which may lead to burnout, while a motivational process that may lead to work engagement and organizational commitment (Bakker et al., 2003, 2005; Hu et al., 2016). Via burnout and work engagement, job demands and job resources have been shown to influence various other aspects of employees functioning (Van den Broeck et al., 2013), such as job satisfaction (Martinussen et al., 2007) and organizational commitment (Hakanen et al., 2008). Meanwhile, job resources could play a moderate role in the relationship between job stress and its psychological outcomes. For example, it can buffer the impact of job demands on burnout (Bakker et al., 2005). With the guidance of the JD-R model, we incorporated study variables well into a theoretical framework which includes the underlying mechanisms regarding how job stress influences organizational commitment, the mediating effect of job burnout and job satisfaction and the moderating effect of university types which represent major difference in organizational resources. Besides, our study also extended the JD-R model in the following two aspects. First, we revisited the relationship of job stress and organizational commitment in a sample of Chinese university teachers. Second, we introduced university types as a moderating effect which is scarcely investigated in the existing literature.

Job stress refers to any affect-laden negative experience that is caused by an imbalance between job demands and the response capability of the workers. When job demands are too high to cope with, stress reactions are likely to occur (Schaufeli and Enzmann, 1998). Teacher’s job stress was firstly defined as teachers’ negative experience due to their negative cognition of classroom environment (Kyriacou and Sutcliffe, 1977). Relevant research showed that people working in the helping professions, especially educators, are particularly prone to being stressed out (Rothmann and Barkhuizen, 2008), and have suffered higher levels of job stress than those working in many other institutions (Winefield and Jarrett, 2001). There is plenty of evidence suggests that academic staff from different countries have suffered above-average level of job stress to some extent (Abouserie, 1996; Yang and Chen, 2016).

Organizational commitment was defined as an employee’s identification and involvement in the organization (Porter et al., 1974). Committed individuals are characterized by sharing of values, desiring to maintain membership, and willing to exert effort on behalf of the organization. As for schools, committed teachers may have a strong psychological connection with their subject areas, students, and school (Firestone and Pennell, 1993). Numerous studies have indicated that the organizational commitment of school is closely related to teachers’ work attitude (Imran et al., 2014), work performance (Wang, 2010; Jing and Zhang, 2014), and turnover intention (Imran et al., 2017). Teachers’ organizational commitment has big impact on the efficiency and effectiveness of their work (Fresko et al., 1997; Louis, 1998) and is directly related to teacher’s job involvement and enthusiasm (Emami et al., 2013).

Job stress is thought to be one of the antecedents of organizational commitment, but understanding of the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment has been both inconsistent and incomplete (Abdelmoteleb, 2019). Although a large number of studies have reported a negative impact of job stress on organizational commitment (e.g., Jamal, 1990; Judeh, 2011; Myers, 2011), other studies have not supported this link (e.g., Parasuraman and Alutto, 1984; Elangovan, 2001; Antón, 2009). In the light of JD-R model, organizational commitment is used as an outcome that may be negatively influenced by burnout through the health impairment process (Hakanen et al., 2006; Llorens et al., 2006). Hu et al. (2011) found that the stress process via burnout led to negative organizational outcomes (low organization commitment, etc.) in two independent Chinese samples. Besides, high demands do not always lead to low organizational commitment. Bakker et al. (2010) found that employees endorse most positive work attitudes (task enjoyment and organizational commitment) when job demands and job resources are both high. Thus, whether job stress brings negative effect is not only related to job demands intensity, but also affected by other factors such as job resources.

In the past two decades, China has witnessed the reform of the employment system in Chinese higher education. Nowadays, new managerialism and academic capitalism have permeated in Chinese university institutions, which prompt the administration structure and performance evaluation system to be more academic productivity-oriented (Bao and Wang, 2012). Under such background, Chinese university teachers need to work harder to increase academic output, they may bear higher job demands in this process, it also means greater chance of promotion and higher salaries (namely high job resources) for hard-working employees, which may facilitate their organizational commitment. For instance, one research conducted in China revealed that perceiving higher job stress would present higher organizational commitment among university PE teachers (Kang and Liu, 2018). Thus, we assume there is positive predictive relation between job stress and organizational commitment in the sample of Chinese university teachers, which is different from the previous research conducted in western culture context.

Hypothesis 1: Job stress could positively predict organizational commitment.

University teachers are among the professionals most susceptible to burnout (Zhong et al., 2009). Job burnout is seen as a psychological syndrome that occurs in response to chronic work-related stressors (Maslach et al., 2001), which is a comprehensive manifestation of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach et al., 1997; Wu et al., 2008; Leiter et al., 2014). Burnout occurs at work like depression occurs in private life, they share similar symptoms such as feeling of low energy and low self-esteem (Ahola et al., 2014). In the JD-R model, Job burnout could be the consequence of two health impairment processes: the exhaustion process caused by high job demands, and the process of failing to meet demands caused by lacking resources (Demerouti et al., 2001). The imbalance that teachers perceived between job demands and job resources affects their psychological well-being at work, which may develop into burnout (Prieto et al., 2008). Job burnout is viewed as a consequence of one’s exposure to chronic job stress (Maslach et al., 2001; Lloyd et al., 2009; Shirom et al., 2009): when short-term stress cannot be alleviated in time, job burnout occurs. Moreover, burnout in teachers is associated with absenteeism, turnover intention, low job satisfaction, negative attitudes and disinterest toward students and their education (D’Amico et al., 2020). Ha et al. (2011) found that emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment were negatively related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment in the group of South Korean PE teachers. In Chinese sample, studies also showed that university teachers with higher job stress would experience higher job burnout (Li, 2018), and job burnout was negatively related to organizational commitment (Zhou, 2015). Consistent with previous research, we propose that job burnout could play a mediating role between job stress and organizational commitment in Chinese university teachers’ group.

Hypothesis 2: Job stress could affect organizational commitment via job burnout.

Job satisfaction is an attitude or subjective experience toward an individual’s job (Miembazi and Qian, 2017). Study shows that there is a negative relationship between job stress and job satisfaction among university staff (Ahsan et al., 2009). For instance, study find that job stress is negatively related to job satisfaction among university teachers in Hong Kong (Leung et al., 2000). Meanwhile, job satisfaction and organizational commitment share a significantly strong positive relationship (Silva, 2006), and job satisfaction can be viewed as an antecedent of organizational commitment (Rusbult and Farrell, 1983; Nagar, 2012; Wang et al., 2016). In addition, job satisfaction could lead to increase in employees’ efficiency, commitment and decrease in absenteeism (Aziri, 2011). It is very important that employees are satisfied with their work so that they can be committed to their organizations (Aksoy et al., 2018). One study conducted under Arabic cultural context found that job satisfaction mediated the influences of role conflict and role ambiguity on various facets of organizational commitment (Yousef, 2013). For teaching occupation, teacher’s satisfaction with his or her job may have strong implications for his or her emotional attachment to the organization (Meyer et al., 2002). To be more specific, job stress influenced psychological health via the mediated effect of job satisfaction (Pan et al., 2010), and job satisfaction is a mediator between job stress and organizational commitment (Lu, 2007). In line with previous research, we indicate that job satisfaction could also play a mediating role between job stress and organizational commitment in Chinese university teachers’ sample.

Hypothesis 3: Job stress could affect organizational commitment via job satisfaction.

Previous scholars tended to view job burnout and job satisfaction as mediate variables since they represent cognition changes of different emotional polarity (Reizer, 2015). Studies have shown a significant negative relationship between job burnout and job satisfaction (Maslach and Schaufeli, 1993). Salehi and Gholtash (2011) noted a negative relationship between burnout and job satisfaction when studying the organizational citizenship behavior of academics. A study conducted by Høigaard et al. (2012) in Norway also observed a strong negative correlation between these two variables. In addition, Wolpin et al. (1991) found burnout appeared to be a cause of reduced job satisfaction in a longitudinal study with teachers and administrators. A study similar to our research conducted by Nagar (2012) which developed a linkage among burnout, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment among university teachers in Jammu’s sample found that burnout led to decreased job satisfaction, and high job satisfaction contributed increase in organizational commitment. Above all, the fourth hypothesis is brought up to explore the mechanism between job stress and organizational commitment among Chinese university teachers.

Hypothesis 4: Job stress could affect organizational commitment via the multiple mediated effect of job burnout and job satisfaction.

Additionally, since burnout is the first response to job stress, it reflects unremitting work demands, which is a result of accumulated work-related stress (Pines and Keinan, 2005). For example, previous research suggested that burnout would mediate the relationship among job stress, depressive symptoms, and low scores on physical health (Zhong et al., 2009). That is, compared with job satisfaction, job stress may be more closely related to job burnout. Thus, we hold that in the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment, the effect of job burnout is stronger than that of job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 5: The independent mediating effect of job burnout is greater than job satisfaction.

According to the classification of administrative subordination, China has three types of public universities: national universities (refer to 211 or 985 project universities, resource-rich and top universities in China), provincial universities (resource-medium and inferior to national universities), and municipal universities (resource-poor and the lowest level among three types of universities). These three types of universities in China are similar to doctoral-granting institution, master-granting institution, and bachelor-granting institution in America separately (Li and Yi, 2010). In China, the resource differences among different university types are of great significance to teachers. Many Chinese scholars have regarded the university type as an indicator of possible difference in the study of university teachers, such as turnover intention (You, 2014) and academic output (Zhang and Xue, 2019). Notably, some research revealed the moderating effect of university types. One study conducted by Chinese scholars Wang and Zhang (2018) which investigated the negative moderating effect of university types on the relationship between university-industry collaboration and research performance in China. They divided universities into research oriented universities (211 or 985 project universities) and non-research oriented universities (non-211 or 985 project universities). Result indicated that organizational resources (i.e., research funds) difference is the key aspect to distinguish different university types. In the JD-R model, job resources may play a role in buffering the health-impairing impact of job demands (Bakker et al., 2007). In addition, job resources was commonly distinguished as both extrinsic and intrinsic aspect to the job (Bakker et al., 2003). For extrinsic, it may be located at the macro, organizational level (e.g., salary or wages, career opportunities, job security) (Demerouti and Bakker, 2011). Although few researchers have noticed the influence of university type, we hold that it reflects the organizational resources difference, which may bring moderating effect. Thus, we attempt to use multi-group analysis to test the differences among three types of university in our research model.

Hypothesis 6: University’s type could moderate the relationships among job stress, job burnout, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment.

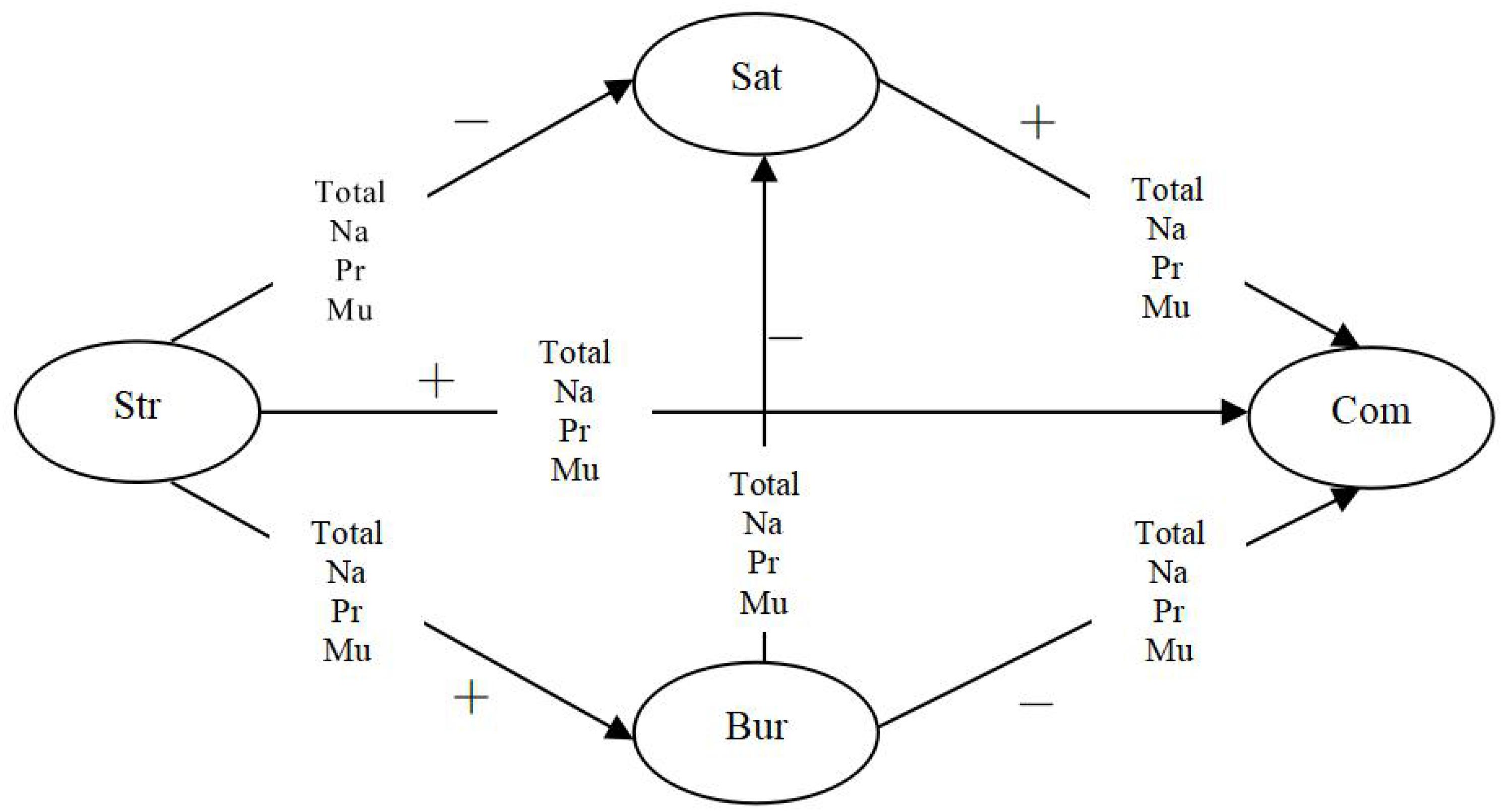

The proposed conceptual model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of the relationship among job stress, job burnout, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and the type of university. Na, national university; Pr, provincial university; Mu, municipal university; Str, job stress; Bur, job burnout; Sat, job satisfaction; Com, organizational commitment.

Our data were obtained from a cluster sample, includes 2,200 teachers from 22 universities in China (encompassing 4 national universities, 10 provincial universities, and 8 municipal universities) by several questionnaires. The authors reached these participants through a contact teacher in each university, and all the contact teachers were trained with unified instruction before the formal test. After informing participants the anonymity of the research and obtaining participants’ agreement, measurement were conducted by trained contact teacher. Finally, all questionnaires were mailed to authors by the contact people.

As a result, 1,988 participants completed and returned the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 90.4%; 82 observations were excluded because of incomplete information, leaving total of 1,906 observations (979 males, 924 females, 3 missing values) for empirical analysis. Most of the participants were highly educated (1,384 having a master’s or doctoral degrees) and were married (n = 1524); 233 were from national universities; 1155 came from provincial universities; and 518 came from municipal universities. 636 of participants were younger than 30, 784 of them were aged between 31 and 40, 355 of them were aged between 41 and 50, 108 of them were older than 50, and 18 of them did not response to age. Approximately 49% of the participants reported 6 to 20 years of teaching experience, approximately 35% reported less than 5 years of teaching experience, and 16% reported more than 20 years of experience as a university teacher.

Job stress was assessed by the Scale for Occupational Stressors on College Teachers (Li, 2008). The scale contains 64 items with 5-point Likert responses (from “no stress” = 0, to “very serious stress” = 4). The items address the stress with various subscales, namely, organizational factors, interpersonal relations, professional development, workloads, lack of interest, job adaptation, scientific research, teacher–student relationships, and family-related factors. An example item is, “It’s hard to get all kinds of honors.” Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this scale was 0.975.

Job burnout was measured using the Scale of Job Burnout on University Teachers (Wang and Gao, 2010), which has 37-item with four subscales include organizational depersonalization, reduced personal accomplishment, emotional exhaustion, and researching exhaustion. Response categories ranged from “not at all” = 0, to “always” = 4. Example items include, “When I wake up in the morning, I feel uneasy at the thought of a day’s work.” Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this scale was 0.959.

Job satisfaction was assessed by the revised Chinese version of the Job Satisfaction Scale (Wang et al., 1993), a highly reliable and valid scale that consists of eight items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 for “not at all satisfied” to 5 for “very satisfied.” An example item is, “The current job is commensurate with your expectations of it.” Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this scale was 0.884.

Organizational commitment was measured using the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Wu and Yang, 1982). The scale contains 15 items with 5-point Likert responses (from “strongly disagree” = 1 to “strongly agree” = 5). Example items include, “I am proud of being a member of this unit.” Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for this scale was 0.905.

All the above scales have Chinese versions with acceptable reliability and validity when being administered to Chinese university teachers (e.g., Wang et al., 2008, 2011, 2013).

The hypothesized independent-dependent variables relationship (H1), mediating effects (H2, H3, H4), specific indirect effect (H5) and moderating effect (H6) were all analyzed using structural equation model (SEM) in Mplus 7.0.

The basic function of SEM is to exploring multivariable (including latent variables) relationships. Before testing specific indirect effect and moderating effects, SEM was set up to investigate predicting relations among study variables. Maximum likelihood method (MLM) was utilized to simultaneously examine relationship between variables while bootstrapping method was used to evaluate mediating effects of job burnout and job satisfaction in SEM. Model fit of the SEM was assessed by using an array of fit criteria. Our total sample size was moderately large (n = 1906) and chi-square is affected by even trivial deviations with a large sample, which easily suggests a poor fit (Kline, 2010). Therefore, we mainly referred to four additional indicators of goodness of fit, namely, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Hu and Bentler (1999) recommended that the cutoff values of good model fit are close to 0.95 for indices such as the CFI and TLI, in combination with a value close to or lower than 0.09 for SRMR and values smaller than 0.06 for RMSEA.

Before constructing SEM, we need to test the assume of multivariate normality, so skewness and kurtosis were examined to determine the normality of the variables (Song et al., 2014). The distribution of the variables was not far from the normality because the absolute value of skewness was less than 3 and the absolute value of kurtosis was less than 10 (see Table 1) (Kline, 2010; Song et al., 2014).

The results of means (M), standard deviations (SD) and correlation analysis among four variables were presented in the overall table (see Table 1) and group-specific table (see Supplementary Tables S1, S2). As shown in the table, all the four focal variables were moderately correlated with each other. A one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Scheffe test was conducted to examine between-group differences in each type of university (i.e., national, provincial, and municipal). The results indicated statistically significant differences between all the study variables (see Supplementary Table S1).

Before testing the measurement model, as suggested by statistical scholars (Little et al., 2002; Bandalos, 2008; Wu and Wen, 2011), item parcels were created for each variable to reduce model complexity and estimation errors. We followed the common strategy by reducing the total number of indicators of each construct to three. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was first conducted for each of the two variables to test whether both of them were unidimensional, which was the premise of item parceling. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for each scale was then carried out to determine the factor loading values for each item. Next, judging by the factor loading, the items of each scale were divided into three parcels for equalizing the average factor loadings through balance method which belongs to factorial algorithm (Rogers and Schmitt, 2004; Wu and Wen, 2011). Finally, each indicator was created by averaging the items in each parcel. As shown in Table 2, the hypothesized four-factor model displayed the best fit indices and was superior to various alternative models.

Since all variables were measure by self-reported scales, common method variance may exist. We detected common method bias by Harman’s single factor test (Harris and Mossholder, 1996). We estimated a CFA model in which the number of latent factors was set to 1. The fitting indexes were as follows: χ2/df = 9.166, RMSEA = 0.079, CFI = 0.423, TLI = 0.414, and SRMR = 0.125. The fit of the one latent method model was much worse (Hu and Bentler, 1999), indicating no serious common method bias.

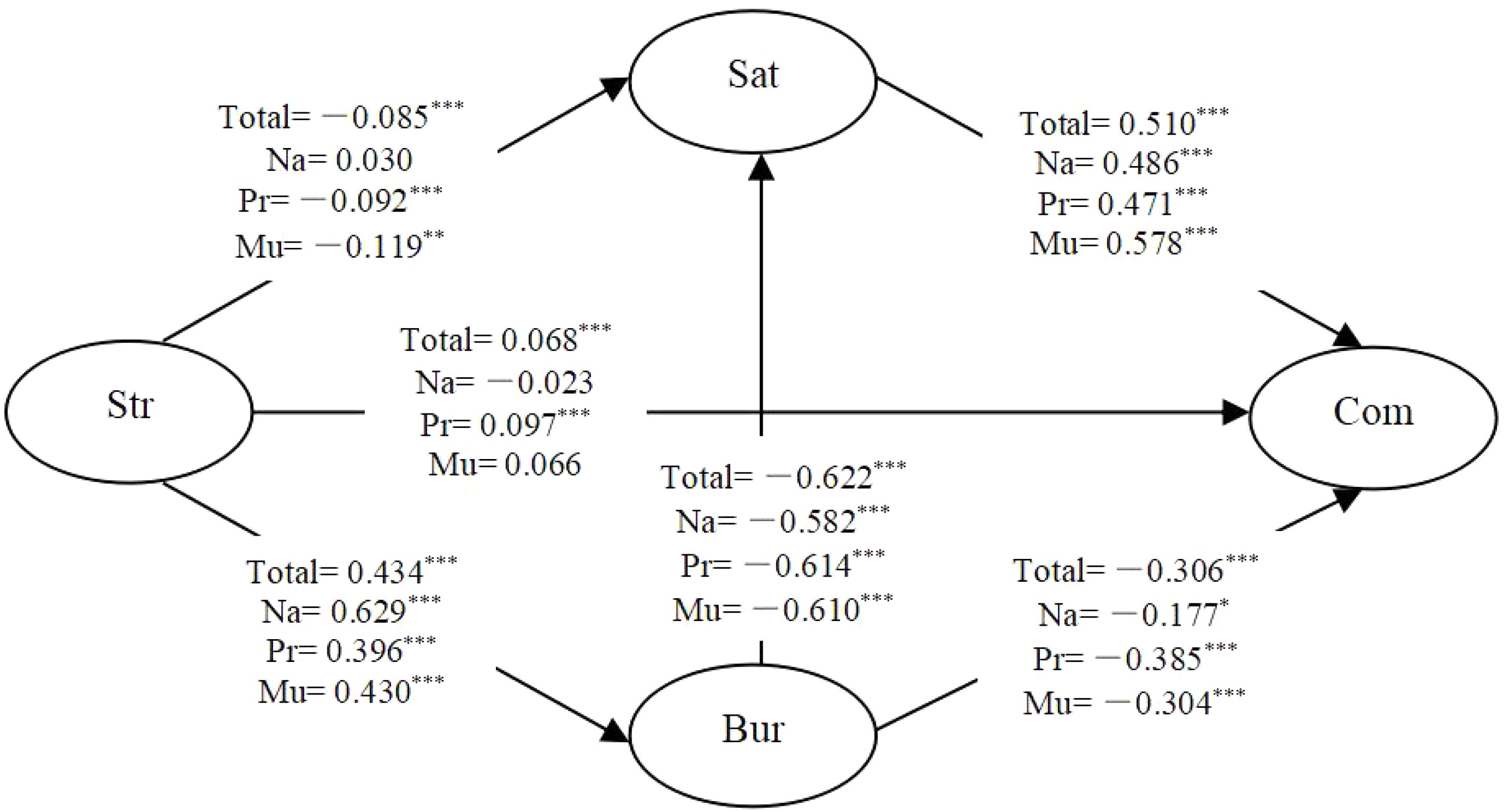

The SEM analysis indicated that the model achieved a good model fit: CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.985, SRMR = 0.023, and RMSEA = 0.053. In Figure 2, the standardized path coefficients of entire sample were all significant. Specifically, job stress negatively affected job satisfaction and positively affected job burnout, job satisfaction affected organizational commitment positively and job burnout influenced job satisfaction and organizational commitment negatively.

Figure 2. Standardized regression coefficient of entire sample and three groups. Na, national university; Pr, provincial university; Mu, municipal university; Str, job stress; Bur, job burnout; Sat, job satisfaction; Com, organizational commitment. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 1 proposed that job stress could positively predict organizational commitment in line with our expectations, the results presented in Figure 2 indicated job stress influenced organizational commitment positively for the overall sample. Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported.

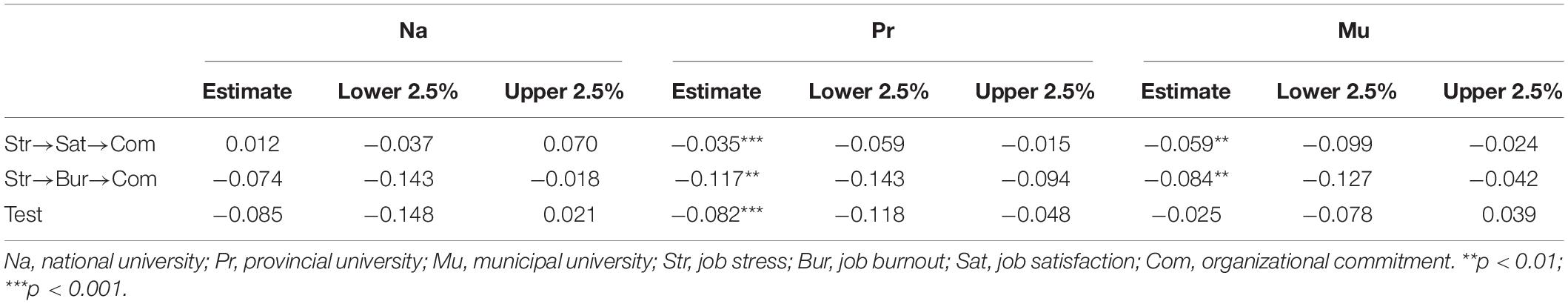

The mediating effects of job burnout and job satisfaction on the job stress-organizational commitment relationships were investigated by computing from 1,000 bootstrap samples. To avoid Type I errors, bias-corrected (BC) interval was be also chosen (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993). BC bootstrap 95% confidence interval indicated significant mediating effect when zero was excluded. From Table 3 we found the indirect relation of job stress with organizational commitment, as mediated by job burnout and job satisfaction independently and jointly. Thus, hypotheses 2, 3, and 4 were supported.

Specific indirect effect test could figure out mediation effect of each mediator in a multiple mediation model. It is sometimes important to test the hypothesis that two indirect effects—whatever their magnitudes may be—are equal in size (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). We applied bootstrapping method in a SEM context for specific indirect effects test in multiple mediator models. First we defined path a was the effect of X on the proposed mediator (M), while path b was the effect of M on Y partialing out the effect of X. Unstandardized regression coefficients were commonly used to quantify all of these paths. The indirect effect of X on Y through M can be quantified as the product of a and b (i.e., ab). Different mediators were distinguished by subscript numbers (e.g., a1, b1 belonged to M1). Then followed by MacKinnon (2000) and Preacher and Hayes (2008), the contrast indirect effects was computed after Equation fc = a1b1 − a2b2 for each bootstrap resample, and a sampling distribution of this contrast was generated.

Through a specific mediation effect difference test, we found that the independent mediating effect of job burnout was significantly greater than job satisfaction in overall sample (see Table 4). In other words, job burnout may play a key mediate role in the job stress—organizational commitment relationships. Thus, hypothesis 5 was supported.

Table 4. Unstandardized mediating effect sizes of job burnout and job satisfaction and their differences.

In provincial universities, the same result of specific mediating effect as the overall sample was observed. However, in national and municipal universities, the specific mediating effect of job satisfaction and job burnout had no significant difference (see Table 5).

Table 5. Unstandardized mediating effect sizes of job burnout and job satisfaction and the differences between them among the three university types.

Before moderating effect test, measurement invariance was first conducted to examine whether the job stress, job burnout, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment were measured in the same way for three types of university teachers. We examined the measurement variance by testing factorial invariance (i.e., testing whether factor loadings are equal across groups). We compared a baseline model where all the factor loadings could vary among the three groups with a measurement model where equality restrictions were placed on the factor loadings. We did not restrict factor variances and co-variances because they were expected to be sample specific, whereas factor loadings should be equal (Rooks et al., 2016). A chi-square test showed that measurement variance was not present.

Then we examined the moderating effects of university types on the relationship among job stress, job burnout, job satisfaction and organizational commitment through multi-group analysis methods. First, in order to determine whether the data of each group fit the structural model well to conduct multi-group analysis, we estimated the baseline model of each group separately. The results showed that all three groups met sufficient fit index (National: RMSEA = 0.036, CFI = 0.995, TLI = 0.993, SRMR = 0.032; Provincial: RMSEA = 0.049, CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.987, SRMR = 0.022; Municipal: RMSEA = 0.065, CFI = 0.984, TLI = 0.977, SRMR = 0.028). Across the three groups, differences in the structural path coefficients were observed (see Figure 2).

Second, we estimated a model initially in which all the path coefficient was estimated freely across the three groups (M0). In the unconstrained model, all parameters were allowed to be estimated freely across the three groups (M0). For M0, the model matched the data (CFI = 0.986, TLI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.049, SRMR = 0.032).

Third, we constrained the path estimation to be equal sequentially, one parameter at a time. In the constrained model, each path coefficient was fixed as equal sequentially across the three groups. Chi-square difference test was used to evaluate whether the goodness of fit has significantly different between the constrained models and M0. Additionally, a scaled chi-square test by Satorra (1999) was used when testing the nested models. A significant chi-square test of difference suggests that the less constrained model should be retained, and a non-significant test indicates that the two models provide equal fit to the data. The results indicated that the four paths were different among the three university types: the positive effect of job stress on job burnout between national and provincial universities (Δχ2 = 16.297, Δdf = 1, p < 0.001), the positive effect of job stress on job burnout between national and municipal universities (Δχ2 = 9.166, Δdf = 1, p < 0.01), the negative effect of job burnout on organizational commitment between national and provincial universities (Δχ2 = 10.876, Δdf = 1, p = 0.001), and the negative influence of job burnout on job satisfaction between national and municipal universities (Δχ2 = 5.237, Δdf = 1, p < 0.05).

Under the framework of the JD-R model, the objectives of this study were to assess the relationships among job stress and organizational commitment as well as the mediating effect of job burnout and job satisfaction, and to examine the moderating role of university types. Overall, the conceptual model was entirely supported by the results from SEM and multi-group analysis. The analysis and interpretations of results were presented as follows.

We assumed that job stress could positively predict organizational commitment among our research sample—Chinese university teachers. Within our expectation, the significant positive direct effect between job stress and organizational commitment was observed, that is, an increase in the stress level of university teachers could promote (rather than reduce) their organizational commitment. The result was inconsistent with most previous research findings that the direct effect of job stress to organizational commitment was negative (Jepson and Forrest, 2006) or non-significant (Antón, 2009); but consistent with the study implemented by Kang and Liu (2018) in Chinese sample. This result can be explained in the following three aspects. First and foremost, cultural differences may lead to different perceptions of organizational commitment. Researchers have argued that commitment is a complex attitude influenced by the nature of the groups and contextual contingent (Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Razak et al., 2010). Chinese dominant culture highly values collectivism, and loyalty and commitment to group goals are core features of Chinese collectivist values (Chang and Lu, 2007; Lu et al., 2010). Studies have found that Chinese employees reported a higher-level commitment than their counterparts in other countries (Perrewe et al., 1995; Cheng and Stockdale, 2003; Miembazi and Qian, 2017). In order to take responsibility for the unity and good functioning of the organization, Chinese people are more likely to show a positive side in the face of stress, namely perceiving stress as a challenge rather than burden. In this way, their emotion toward the organization could be enhanced. At the same time, universities have been long described as the Ivory Tower, where people work there enjoy a stable working environment, job security and high social status. Thus, becoming a university teacher has extraordinary significance for most Chinese people, which makes them have more attachment to this profession. For instance, one study showed the organizational commitment of Chinese university teachers is above average (Zhou, 2015). In addition, job stress can be the obstacle as well as the support. Xu and Zheng (2012) put forward that young university teachers’ working efficiency will be enhanced unceasingly even under the stress of difficult task when they obtained proper support from organization. Also, an exploratory study conducted in China identified challenging job demands may have positive effect on university teachers’ well-being (Han et al., 2019).

In this study, job burnout was observed to be a mediator in the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment. The effect of job stress to organizational commitment was partially mediated by job burnout, suggesting that university teachers perceiving higher levels of job stress for a long time would feel burnout by their job, and be reluctant to stay in the organization consequently. Researchers have argued that job burnout occurs when an individual’s lost resources are not recovered or incomplete for a long time (Głebocka and Lisowska, 2007), as a result their attitudes toward work will be affected (Cordes and Dougherty, 1993). These opinions were supported in this study.

Job satisfaction was found to act as a mediator in the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment, corresponding to ideas that consider job satisfaction as a prior variable of organizational commitment (e.g., Nagar, 2012; Miembazi and Qian, 2017). This result suggested that university teachers perceiving a higher level of job stress would feel unsatisfied with their job and be reluctant to stay in the organization as before. We also found the serial mediated effect of job burnout and job satisfaction in the mechanism of how job stress influencing organizational commitment. Specifically speaking, when university teachers feel high job stress in the long term, they would feel burnout, and then result in unsatisfying with their job; therefore, their willingness to stay in the organization may be reduced.

Furthermore, a specific mediation effect difference test revealed that the independent mediating effect of job burnout is significantly greater than job satisfaction in the overall sample. As a result, job stress is more likely to affect organizational commitment via job burnout, that is, job burnout may play a key mediate role in the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment.

The result of multi-group analysis showed that for national university teachers, the positive effect of job stress on job burnout is the highest among three types of university teachers. National university teachers are burdened by great expectations from the public because they have taken on the mission of university, which is to play exemplary and guiding role in improving pedagogy, scientific research, and social services. To achieve performance appraisal standards and requirements, their resources are always in a state of high consumption. Liu’s (2015) study found that on average, Chinese university teachers work 52 h per week, which is much higher than the legal weekly working hours (44 h); even during vacations, they work 32.9 h per week. Additionally, the average working hours of 211 project university (a category of national university) teachers are longer than their non- 211 project counterparts. This phenomenon perhaps explains why national university teachers experience a higher degree of job stress and are more prone to burnout. Compared with counterparts, national university teachers have a high level of job stress; however, they could enjoy higher salaries, more advantageous research conditions, easier access to necessary resources and other benefits. Maybe these resources that they enjoy could alleviate their negative attitude toward work and organization. As the results of this study displayed, the negative effect of job burnout on organizational commitment for teachers in national university is lower compared with those who in provincial university; and the negative effect of job burnout on job satisfaction for teachers in national university is lower compared with those who in provincial university.

We also observed that only the job stress of provincial university teachers can significantly positively predict their organizational commitment, that is, the positive direct effect from job stress to organizational commitment may be mainly contributed by provincial university teachers. Provincial university teachers enjoy medium-quality scientific research conditions and welfare treatment, they have vastly potential for development, so they work hard to catch up with national university teachers. However, the actual situation is that they received the least educational output. For example, the Annual Report of China’s Education indicated that the employment rate of provincial university students (67.4%) is much lower than that of national university students (75.5%) and municipal university students (78.1%) (Yang, 2014). According to Festinger’s (1957) cognitive dissonance theory, when an individual’s attitudes are inconsistent with their actions, cognitive dissonance occurs. Since cognitive dissonance can produce mental tension, individuals will strive to eliminate this tension to restore cognitive balance. As for provincial university teachers, there is a conflict between attitude and action perhaps they can only change their attitude toward work place to restore cognitive balance, namely put love organization as a reason for high stress work, in this way organizational commitment increased with stress. At the same time, through the specific mediation effect difference test, we found that only in provincial universities the independent mediating effect of job burnout is significantly greater than job satisfaction. That is to say, their organizational support mismatched development ambition, and their input is disproportionate with output, which are more likely to make them job burnout, rather than job satisfaction.

This paper innovatively compared different types of samples in the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment under non-western culture context. Although the theories and methods in this paper were from western, the questionnaires were developed by Chinese scholars and participants were selected from China, which were more suitable for China’s indigenization research. This study also extended the JD-R model with the sample of Chinese university teachers, and introduced a new kind of job resources—university types, which accumulates empirical evidence for cross-cultural research on organizational behavior field in the future.

The current research has its implication in organizational psychology. University administrators can implement measures to stimulate teachers’ positive work attitude to reduce job burnout, and provide effective interventions to enhance job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Interventions can be taken to avoid the feeling of burnout, such as showing the effects of stress and techniques to cope with occupational stress, which is proved effective (Wu et al., 2006). Overall, the result of this study showed that the higher the job stress perceived, the stronger the organizational commitment would be. Therefore, it is good for university teachers to maintain a moderate work pressure. Besides, university type plays an important role among the relationship of the variables, education organization could take measures from the view of improving resource allocation. To be more specific, as for provincial universities, striking a balance between resources and tasks is an effective way to reduce job burnout, which can further increase employee loyalty to the university. As for municipal universities, optimizing resource allocation is a good way to enhance teachers’ job satisfaction. Fortunately, the problem of uneven distribution of higher education resources has been put on the agenda in National People’s Congress (NPC, the highest organ of state power of the People’s Republic of China), and this gap will be narrowed for the foreseeable future.

There are two limitations in the present study. First, this study only examined the moderating role of three types of university, and pointed out that resource difference may be the reasons for groups’ different presented in the study model. We suggest future studies to include other potential organizational factors, such as organizational climate and leadership style to explain these differences in a more comprehensive way. Second, we have studied the influence of job stress on job satisfaction, job burnout and organizational commitment under the guidance of previous research, but it is also possible that one’s organizational commitment affects feelings of job stress. Hence, cross-lagged longitudinal design should be further considered to infer causality among variables.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Shandong Normal University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

PW conceived this study. PC designed and completed the manuscript. JW participated in data analysis. RP polished the language. YS, MY, and LJ participated in data collection. XZ submitted and revised the manuscript. DZ provided significant advice in revision process. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by the fund for building world-class universities (disciplines) of Renmin University of China.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge the reviewers IS and VC for their valuable comments and suggestions.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576768/full#supplementary-material

Abdelmoteleb, S. A. (2019). A new look at the relationship between job stress and organizational commitment: a three-wave longitudinal study. J. Bus. Psychol. 34, 321–336. doi: 10.1007/s10869-018-9543-z

Abouserie, R. (1996). Stress, coping strategies and job satisfaction in university academic staff. Educ. Psychol. 16, 49–56. doi: 10.1080/0144341960160104

Ahola, K., Hakanen, J., Perhoniemi, R., and Mutanen, P. (2014). Relationship between burnout and depressive symptoms: a study using the person-centred approach. Burn. Res. 1, 29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2014.03.003

Ahsan, N., Abdullah, Z., Yong, D., Yong, G.-F. D., and Alam, S. S. (2009). A study of job stress on job satisfaction among university staff in Malaysia: empirical study. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 8, 123–131.

Aksoy, C., Halil Íbrahim, S., and Yunus, Y. (2018). Examination of the relationship between job satisfaction levels and organizational commitments of tourism sector employees: a research in the Southeastern Anatolia region of Turkey. Electron. J. Soc. Sci. 17, 356–365. doi: 10.17755/esosder.343032

Antón, C. (2009). The impact of role stress on workers’ behaviour through job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Int. J. Psychol. 44, 187–194. doi: 10.1080/00207590701700511

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 10, 170–180. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2003). Dual processes at work in a call centre: an application of the job demands-resources model. Eur. J. Organ. Psychol. 12, 393–417. doi: 10.1080/13594320344000165

Bakker, A. B., Hakanen, J. J., Demerouti, E., and Xanthopoulou, D. (2007). Job resources boost work engagement, particularly when job demands are high. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 274–284. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.274

Bakker, A. B., Veldhoven, M. V., and Xanthopoulou, D. (2010). Beyond the demand–control model: thriving on high job demands and resources. J. Pers. Psychol. 9, 3–16. doi: 10.1027/1866-5888/a000006

Bandalos, D. L. (2008). Is parceling really necessary? A comparison of results from item parceling and categorical variable methodology. Struct. Equ. Model. 15, 211–240. doi: 10.1080/10705510801922340

Bao, W., and Wang, J. Y. (2012). Stress in the ivory tower: an empirical study of stress and academic productivity among university faculty in China. Peking Univ. Educ. Rev. 10, 124–191.

Chang, K., and Lu, L. (2007). Characteristics of organizational culture, stressors and wellbeing: the case of Taiwanese organizations. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 549–568. doi: 10.1108/02683940710778431

Cheng, Y., and Stockdale, M. S. (2003). The validity of the three-component model of organizational commitment in a Chinese context. J. Vocat. Behav. 62, 465–489. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8791(02)00063-5

Cordes, C. L., and Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad. Manage. Rev. 18, 621–656. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1993.9402210153

D’Amico, A., Geraci, A., and Tarantino, C. (2020). The relationship between perceived emotional intelligence, work engagement, job satisfaction, and burnout in Italian school teachers: an exploratory study. Psychol. Top. 29, 63–84. doi: 10.31820/pt.29.1.4

Demerouti, E., and Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands-resources model: challenges for future research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 37:a974. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Efron, B., and Tibshirani, R. J. (1993). An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-4541-9

Elangovan, A. R. (2001). Causal ordering of stress, satisfaction and commitment, and intention to quit: a structural equations analysis. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 22, 159–165. doi: 10.1108/01437730110395051

Emami, F., Bavarsad Omidian, N., Fazel Hashemi, S. M., and Pajoumnia, M. (2013). Teacher’s job attitudes: comparison and relationship between organizational commitment and job involvement among physical education teachers of Iran. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 7, 7–11.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Am. J. Psychol. 207, 2112–2114. doi: 10.1192/bjp.109.458.164

Firestone, W. A., and Pennell, J. R. (1993). Teacher commitment, working conditions, and differential incentive policies. Rev. Educ. Res. 63, 489–525. doi: 10.3102/00346543063004489

Fresko, B., Kfir, D., and Nasser, F. (1997). Predicting teacher commitment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 13, 429–438. doi: 10.1016/s0742-051x(96)00037-6

Głebocka, A., and Lisowska, E. (2007). Professional burnout and stress among polish physicians explained by the Hobfoll resources theory. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 58(Suppl. 5(Pt1), 243–252. doi: 10.1152/jn.z9k-8581-corr.2007

Graça, M., Pais, L., Mónico, L., Santos, N. R. D., Ferraro, T., and Berger, R. (2020). Correction to: decent work and work engagement: a profile study with academic personnel. Appl. Res. Qual. Life doi: 10.1007/s11482-020-09814-5

Ha, J., King, K. M., and Naeger, D. J. (2011). The impact of burnout on work outcomes among South Korean physical education teachers. J. Sport Behav. 34, 343–357.

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A., and Schaufeli, W. (2006). Burnout and engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 43, 495–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., and Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: a three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work Stress 22, 224–241. doi: 10.1080/02678370802379432

Han, J., Yin, H., Wang, J., and Bai, Y. (2019). Challenge job demands and job resources to university teacher well-being: the mediation of teacher efficacy. Stud. High. Educ. 45, 1171–1185. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1594180

Harris, S. G., and Mossholder, K. W. (1996). The affective implications of perceived congruence with culture dimensions during organizational transformation. J. Manage. 22, 527–547. doi: 10.1177/014920639602200401

Høigaard, R., Giske, R., and Sunsdsli, K. (2012). Newly qualified teachers’ work engagement and teacher efficacy influences on job satisfaction, burnout, and the intention to quit. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 35, 347–357. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2011.633993

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, Q., Schaufeli, W. B., and Taris, T. W. (2011). The job demands-resources model: an analysis of additive and joint effects of demands and resources. J. Vocat. Behav. 79, 181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.009

Hu, Q., Schaufeli, W. B., and Taris, T. W. (2016). Extending the job demands-resources model with guanxi exchange. J. Manag. Psychol. 31, 127–140. doi: 10.1108/jmp-04-2013-0102

Imran, H., Arif, I., Cheema, S., and Azeem, M. (2014). Relationship between job satisfaction, job performance attitude towards work and organizational commitment. Entrep. Innov. Manage. J. 2, 135–144.

Imran, R., Allil, K., and Mahmoud, A. B. (2017). Teacher’s turnover intentions: examining the impact of motivation and organizational commitment. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 31, 828–842. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-05-2016-0131

Jamal, M. (1990). Relationship of job stress and type-a behaviour to employees’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, psychosomatic health problems, and turnover motivation. Hum. Relat. 43, 727–738. doi: 10.1177/001872679004300802

Jepson, E., and Forrest, S. (2006). Individual contributory factors in teacher stress: the role of achievement striving and occupational commitment. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 76, 183–197. doi: 10.1348/000709905X37299

Jing, L., and Zhang, D. (2014). Does organizational commitment help to promote university faculty’s performance and effectiveness. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 23, 201–212. doi: 10.1007/s40299-013-0097-6

Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S., Donald, L., Taylor, P., and Millet, C. (2005). The experience of work-related stress across occupations. J. Manag. Psychol. 20, 178–187. doi: 10.1108/02683940510579803

Judeh, M. (2011). Role ambiguity and role conflict as mediators of the relationship between orientation and organizational commitment. Int. Bus. Res. 4, 171–181. doi: 10.5539/ibr.v4n3p171

Kang, X. L., and Liu, L. (2018). Discussion of the relationship between perceived job characteristics and organizational commitment of university pe teachers-from the aspect of job stress. J. Interdiscip. Math. 21, 317–327. doi: 10.1080/09720502.2017.1420562

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Kyriacou, C., and Sutcliffe, J. (1977). Teacher stress: a review. Educ. Rev. 29, 299–306. doi: 10.1080/0013191770290407

Leiter, M. P., Bakker, A. B., and Maslach, C. (2014). Burnout at Work: A Psychological Perspective. New York, NY: Psychology Press. doi: 10.4324/978131589416

Leung, T. W., Siu, O. L., and Spector, P. E. (2000). Faculty stressors, job satisfaction, and psychological distress among university teachers in Hong Kong: the role of locus of control. Int. J. Stress Manage. 7, 121–138. doi: 10.1023/A:1009584202196

Li, F. C. (2008). A Compilation of the Scale for Occupational Stressors on College Teachers. Master’s thesis, Shandong Normal University, Jinan.

Li, J. J. (2018). A study on university teachers’ job stress-from the aspect of job involvement. J. Interdiscip. Math. 21, 341–349. doi: 10.1080/09720502.2017.1420564

Li, Z. F., and Yi, J. (2010). The stratification of the academic profession in different types of Universities in America: characteristics and Enlightments. Tsinghua J. Educ. 31, 57–68. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-4519.2010.02.009

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., and Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. 9, 151–173. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem0902_1

Liu, B. (2015). A Study of University Teachers’. Working Time. Open Educ. Res. 21, 56–62. doi: 10.13966/j.cnki.kfjyyj.2015.02.006

Liu, H., and Cheung, F. M. (2015). The role of work-family role integration in a job demands-resources model among Chinese secondary school teachers. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 18, 288–298. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12103

Liu, X. P., and Zhou, Y. Y. (2016). Research on the impact of job stress on job satisfaction of college teachers. High. Educ. Explor. 153, 125–129.

Llorens, S., Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., and Salanova, M. (2006). Testing the robustness of the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manage. 13, 378–391. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.13.3.378

Lloyd, C., King, R., and Chenoweth, L. (2009). Social work, stress and burnout: a review. J. Ment. Health 11, 255–265. doi: 10.1080/09638230020023642

Louis, S. K. (1998). Effects of teacher quality of work life in secondary schools on commitment and sense of efficacy? Sch. Effect. Sch. Improve. 9, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/0924345980090101

Lu, H. J. (2007). The Research on the Relationships among Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment of University Faculty. Master’s thesis, Sichuan University, Chengdu.

Lu, L., Siu, O. L., and Lu, C. Q. (2010). Does loyalty protect Chinese workers from stress? The role of affective organizational commitment in the greater China region. Stress Health 26, 161–168. doi: 10.1002/smi.1286

MacKinnon, D. P. (2000). “Contrasts in multiple mediator models,” in Multi-Variate Applications In Substance Use Research: New Methods for New Questions, eds J. Rose, L. Chassin, C. C. Presson, and S. J. Sherman (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 141–160.

Markus, H. R., and Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 98, 224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Martinussen, M., Richardsen, A. M., and Burke, R. J. (2007). Job demands, job resources and burnout among police officers. J. Crim. Justice 35, 239–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2007.03.001

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., and Leiter, M. P. (1997). “The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual,” in Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources, eds C. P. Zalaquett and R. J. Wood (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press), 191–218.

Maslach, C., and Schaufeli, W. B. (1993). “Historical and conceptual development of burnout,” in Professional Burnout: Recent Development in Theory and Research, eds W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, and T. Marek (Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis), 1–16. doi: 10.4324/9781315227979-1

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., and Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., and Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organisation: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 61, 20–52. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Miembazi, M., and Qian, Y. (2017). Research on the impact of organizational commitment on job satisfaction between China and Congo-Brazzaville. J. Res. Bus. Econ. Manage. 8, 1444–1450.

Myers, M. J. (2011). Effect of social support on role stress and organizational commitment: tests of three theoretical models. J. Pharm. Mark. Manage. 9, 93–116. doi: 10.3109/J058v09n02_05

Nagar, K. (2012). Organizational commitment and job satisfaction among teachers during times of burnout. Vikalpa 37, 43–60. doi: 10.1177/0256090920120205

Noor, N. M., and Zainuddin, M. (2011). Emotional labor and burnout among female teachers: work-family conflict as mediator. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 14, 283–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839x.2011.01349.x

Pan, X., Wang, J., Zheng, Z. J., and Tang, Y. (2010). Analysis-how job pressure mediates psychological health of college teachers in Shanxi. China J. Health Psychol. 18, 29–32.

Parasuraman, S., and Alutto, J. A. (1984). Sources and outcomes of stress in organizational settings: toward the development of a structural model. Acad. Manage. J. 27, 330–350. doi: 10.2307/255928

Perrewe, P. L., Ralston, D. A., and Fernandez, D. R. (1995). A model depicting the relations among perceived stressors, role conflict, and organizational commitment: a comparative analysis of Hong Kong and the United States. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 12, 1–21.

Pines, A. M., and Keinan, G. (2005). Stress and burnout: the significant difference. Pers. Individ. Differ. 39, 625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.009

Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., and Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 59, 603–609. doi: 10.1037/h0037335

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879

Prieto, L. L., Soria, M. S., Martínez, I. M., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). Extension of the job demands-resources model in the prediction of burnout and engagement among teachers over time. Psicothema 20, 354–360.

Razak, N. A., Darmawan, I. G. N., and Keeves, J. P. (2010). The influence of culture on teacher commitment. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 13, 185–205. doi: 10.1007/s11218-009-9109-z

Reizer, A. (2015). Influence of employees’ attachment styles on their life satisfaction as mediated by job satisfaction and burnout. J. Psychol. 149, 356–377. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2014.881312

Rogers, W. M., and Schmitt, N. (2004). Parameter recovery and model fit using multidimensional composites: a comparison of four empirical parceling algorithms. Multivariate Behav. Res. 39, 379–412. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3903_1

Rooks, G., Sserwanga, A., and Frese, M. (2016). Unpacking the personal initiative-performance relationship: a multi-group analysis of innovation by Ugandan rural and urban entrepreneurs. Appl. Psychol. 65, 99–131. doi: 10.1111/apps.12033

Rothmann, S., and Barkhuizen, N. (2008). Burnout of academic staff in South African higher education institutions. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 22, 321–336. doi: 10.1177/008124630803800205

Rusbult, C. E., and Farrell, D. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: the impact on job satisfaction, job commitment, and turnover of variations in rewards, costs, alternatives, and investments. J. Appl. Psychol. 68, 429–438. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.68.3.429

Salehi, M., and Gholtash, A. (2011). The relationship between job satisfaction, job burnout and organization commitment with the organizational citizenship behaviour among members of faculty in the Islamic Azad University-First district branches, in order to provide the appropriate model. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 15, 306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.091

Satorra, A. (1999). Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. Econ. Work. Pap. 36, 233–247. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.189431

Schaufeli, W. B., and Enzmann, D. (1998). The Burnout Companion to Study and Practice: A Critical Analysis. London: Taylor and Francis.

Shirom, A., Oliver, A., and Stein, E. (2009). Teachers’ stressors and strains: a longitudinal study of their relationships. Int. J. Stress Manage. 16, 312–332. doi: 10.1037/a0016842

Silva, P. (2006). Effects of disposition on hospitality employee job satisfaction and commitment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 18, 317–328. doi: 10.1108/09596110610665320

Song, T. M., An, J. Y., Hayman, L. L., Woo, J. M., and Yom, Y. H. (2014). Stress, depression, and lifestyle behaviors in Korean adults: a latent means and multi-group analysis on the Korea health panel data. Behav. Med. 42, 72–81. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2014.943688

Van den Broeck, A., Van Ruysseveldt, J., Vanbelle, E., and De Witte, H. (2013). The job demands-resources model: overview and suggestions for future research. Adv. Posit. Organ. Psychol. 1, 83–105. doi: 10.1108/s2046-410x(2013)0000001007

Wang, C. (2010). An empirical study of the performance of university teachers based on organizational commitment, job stress, mental health and achievement motivation. Can. Soc. Sci. 6, 127–140.

Wang, J. H., Tsai, K. C., Lei, L. J. R., Chio, I. F., and Lai, S. K. (2016). Relationships among job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intention: evidence from the gambling industry in Macau. Bus. Manage. Stud. 2, 104–110. doi: 10.11114/bms.v2i1.1280

Wang, P., and Gao, F. Q. (2010). Full-Information Item Bifactor Analysis of the Job Burnout Scale for Chinese College Teachers. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 5, 5–7. doi: 10.4156/jcit.vol5.issue7.20

Wang, P., Gao, F. Q., and Li, Y. (2013). Group types of job burnout for University Teachers in China. Educ. Res. 34, 107–117.

Wang, S. N., Gao, H., Wang, P., Jiang, N. Z., and Gao, F. Q. (2008). The relation between high school middle-level leader and teacher work attitude–based on multilayer analysis for teacher collective efficacy. Psychol. Res. 1, 42–48.

Wang, X. D., Wang, X. L., and Ma, H. (1993). Handbook of Mental Health Rating Scale (Revised). Beijing: China mental health magazine, 127–129.

Wang, X. H., and Zhang, B. (2018). Relationship between university-industry collaboration and research performance of universities: the moderating effect of university types. Sci. Res. Manage. 39, 135–142.

Wang, Y., Wang, P., and Gao, F. Q. (2011). Relationship between College Teachers’ Personality, Job burnout and Job Satisfaction. J. Nanjing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 13, 90–95. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-2129.2011.04.021

Winefield, A. H., and Jarrett, R. (2001). Occupational stress in university staff. Int. J. Stress Manage. 8, 285–298. doi: 10.1023/A:1017513615819

Wolpin, J., Burke, R. J., and Greenglass, E. R. (1991). Is job satisfaction an antecedent or a consequence of psychological burnout? Hum. Relat. 44, 193–209. doi: 10.1177/001872679104400205

Wu, J. J., and Yang, Q. L. (1982). A Study of Personal Characteristics, Organizational Climate, and Organizational Commitment. Master’s thesis, National Chengchi University, Taipei.

Wu, S., Zhu, W., Li, H., Wang, Z., and Wang, M. (2008). Relationship between job burnout and occupational stress among doctors in China. Stress Health 24, 143–149. doi: 10.1002/smi.1169

Wu, S. Y., Li, J., Wang, M. J., Wang, Z. M., and Li, H. Y. (2006). Short communication: intervention on occupational stress among teachers in the middle schools in China. Stress Health 22, 229–236. doi: 10.1002/smi.1108

Wu, Y., and Wen, Z. L. (2011). Item parceling strategies in structural equation modeling. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 19, 1859–1867.

Xu, Z. J., and Zheng, X. C. (2012). “A research on stress of scientific research and performance management for young teacher at University —Based on application research of Yerkes-Dodson Law,” in Proceedings of the 2012 Conference on Creative Education, Shanghai, 230–234.

Yang, X. L., and Chen, F. (2016). University and college teachers’ working pressure and distribution difference: an empirical study. Contemp. Teach. Educ. 9, 77–83.

You, Y. (2014). Opportunity costs and faculty turnover intention: an empirical investigation. China High. Educ. Res. 60–67.

Yousef, D. A. (2013). Job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between role stressors and organizational commitment: a study from an Arabic cultural perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 17, 250–266. doi: 10.1108/02683940210428074

Zhang, J., Cao, C., Shen, S., and Qian, M. (2019). Examining effects of self-efficacy on research motivation among Chinese University teachers: moderation of leader support and mediation of goal orientations. J. Psychol. 153, 414–435. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2018.1564230

Zhang, Z. M., and Xue, Q. X. (2019). Empirical analysis of college types, teachers’ research ability and academic output–based on a national sample survey of sociology faculty. J. Hebei Univ. Sci. Technol. 19, 85–91.

Zhong, J., You, J., Gan, Y., Zhang, Y., Lu, C., and Wang, H. (2009). Job stress, burnout, depression symptoms, and physical health among Chinese university teachers. Psychol. Rep. 105, 1248–1254. doi: 10.2466/pr0.105.f.1248-1254

Zhou, Y. G. (2015). Effect of organizational commitment on job burnout and satisfaction. Psychol. Res. 8, 62–67.

Keywords: job stress, organizational commitment, job burnout, job satisfaction, Chinese university teacher, the type of university

Citation: Wang P, Chu P, Wang J, Pan R, Sun Y, Yan M, Jiao L, Zhan X and Zhang D (2020) Association Between Job Stress and Organizational Commitment in Three Types of Chinese University Teachers: Mediating Effects of Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 11:576768. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576768

Received: 26 June 2020; Accepted: 31 August 2020;

Published: 08 October 2020.

Edited by:

Berta Schnettler, University of La Frontera, ChileReviewed by:

Vincenza Capone, University of Naples Federico II, ItalyCopyright © 2020 Wang, Chu, Wang, Pan, Sun, Yan, Jiao, Zhan and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiangping Zhan, Nzk4MDMzMTk1QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.