- 1Carrera de Sociología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina

- 2Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

- 3Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Buenos Aires, Argentina

This study aims to explore the impact of migration as a central event in personal identity, spirituality, and religiousness on subjective well-being (SWB). The sample was composed of 204 Latin American immigrants living in Israel, with ages ranging from 18 to 80 years (M = 48.76; SD = 15.36) across both sexes (Men = 34.8%; Women = 65.2%). The results show that, when analyzing the effects on SWB, Positive and Negative Affect, Centrality of Event, Religious Crisis, and Spiritual Transcendence present as the most relevant explanatory variables within the models. However, contrary to expectation, the present study identifies positive associations between the centrality of migration and SWB. Motivations for emigration should be explored in further studies as they could be mediating the relationship between centrality of events and SWB.

Introduction

Since the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, about 92,000 Jews migrated from Latin America (Lesser, 2016) and well over half this group have come from Argentina (58%), with smaller groups from Brazil (11%), Uruguay (9%), Chile (6%), Mexico (4%), Colombia (3%), Venezuela (2%), and other countries (7%) (Babis, 2016). Although ideological, political, and religious reasons for aliyah have featured emphatically in the academic literature (Babis, 2016), Latin Americans’ motivations to migrate to Israel frequently include financial and political factors, and anti-Semitism (Rein, 2010, 2013; Siebzehner, 2010, 2016; Klor, 2016). For example, the cyclical behavior of the Argentine economy and the 2-year anti-Semitic campaign that followed the kidnapping of Eichmann contributed to a surge in the number of Argentine immigrants to Israel in 1963 (Rein, 2001) and, besides the impact of anti-Semitism on migrants’ decisions, most were seriously affected by the country’s economic fluctuations, recessions, and currency devaluations (Krupnik, 2020). Political persecution during military regimes in some Latin American countries, like Argentina and Chile, has also been flagged as factors that influenced this immigration during the 1970s (Babis, 2016). More recently, the 1992 attack on the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires, the 1994 bombing of the AMIA Jewish Community Center in Buenos Aires, and Argentina’s political and economic crisis between 1999 and 2002 have also been flagged among events that have led to Latin American emigration to Israel (Krupnik, 2011; Sznajder, 2015; Babis, 2016; Lesser, 2016).

Migration, Trauma, and Well-Being

According to the literature, when migration is triggered by preservation motivation – when physical, social, and psychological security for self and family are motivators of emigration – it can be a stressful and traumatic event, and may have a negative impact on mental health (Finklestein and Solomon, 2009; Vathi and King, 2017). Migrants from socio-politically unstable countries may have been in situations where their lives or those of friends and family members, were in danger, so they not only have to negotiate the process of adaptation to a new social environment (Babis, 2016; Hashemi et al., 2019), but also may simultaneously experience vulnerability to various psychological symptoms related to higher levels of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and lower levels of subjective and psychological well-being (Foster, 2001; Kalir, 2015; Tartakovsky et al., 2017). Gal (2020) has recently explored childhood experiences of anti-Semitism during Argentina’s last military dictatorship (1976–1983). She interviewed 15 participants, applying the narrative approach method and observations: the thematic textual analysis of these interviews centered on the behavioral and emotional expressions of these immigrants’ past experiences in their current lives as adult immigrants in Israel. The findings revealed that participants were exposed to severe manifestations of anti-Semitism during their childhood and that their present-day experiences include a variety of negative, long-term emotional and behavioral reactions.

The Centrality of Traumatic Events in Personal Identity and Well-Being

Personal memories give meaning and structure to people’s life stories and help bolster individual identity (Baerger and McAdams, 1999; Watson and Dritschel, 2015). According to Berntsen and Rubin (2006), autobiographical memory is usually slanted toward positive life events, so that people tend to remember more positive than negative events from their lives, thus supporting a more positive view of themselves. A conventional life script contains more positive than negative events, often about such culturally expected role transitions as a graduation or a wedding (Berntsen and Rubin, 2006). However, for some individuals, a negative event perceived as traumatic, highly stressful, or shocking, like the loss of a loved one or a near-death experience, could, under certain circumstances, become pivotal. People who define specific stressful or traumatic events as being central to their identities believe that these events make their lives different from those of most other people, and that people who have not experienced these types of events think differently than they do (Berntsen and Rubin, 2006; Vermeulen et al., 2019). These memory characteristics are usually associated with feelings of being detached from other individuals within their own society, with implications for psychological well-being (Watson and Dritschel, 2015). Hence, if migrants’ traumatic memories form “turning points” in the organization of experiences, they may form a central component of personal identity and be harmful to mental health (Bernstein et al., 2003; Cerniglia and Cimino, 2012; Staugaard et al., 2015; Brooks et al., 2017). Results from the systematic review by Gehrt et al. (2018) of 92 publications show that centrality of event probes aspects of autobiographical memory that are of broad relevance to clinical disorders and have specific implications for PTSD.

Religion, Spirituality, and Coping

In stressful times, some individuals tend to turn to religion for support, and although research shows that religion can be a positive force for mental health, it can also have a negative emotional impact in experiences of religious crisis, defined as conflicts related to religion, co-religionists, and relationships with God (Piedmont, 2012; Shilo et al., 2016; Abu-Raiya et al., 2020). Because of this, when triggered by Jewish identity, religion, and spirituality could be related to positive and negative coping mechanisms for post-migration stressors (Koenig et al., 2012; Rosmarin et al., 2017; Pirutinsky et al., 2019). Among other positive and negative issues, while religious affiliation and practice can provide social support for immigrants, they may also prompt feelings of rejection by the religious community when people are unable to live according to strict moral and religious standards (Piedmont, 2009; Dein et al., 2012; Weber and Pargament, 2014; Kim et al., 2020).

Regarding spirituality, while for some authors it may provide a strong sense of connectedness with others, which could help in coping with traumatic events (Braganza and Piedmont, 2015; Sigamoney, 2018; Khursheed and Shahnawaz, 2020), other authors argue that spiritual people without a religious framework are more vulnerable to developing mental disorders (King et al., 2013). Among other positive and negative issues, while spirituality could give people meaning and a sense of purpose (Piedmont, 2012; Le et al., 2019), harmful spirituality includes rigidity of belief, coercion, and the alienation of spirituality groups or cult members from outside supports (Galen, 2015; Kao et al., 2020).

The Present Study

This study aims to explore relationships between centrality of event (migration) in personal identity, religion, spirituality, and subjective well-being (SWB). We postulated that, being central to identities, the experience of migration, spirituality, and religion, are associated with well-being.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The sample was composed of 204 Latin American immigrants living in Israel, with ages ranging from 18 to 80 years (M = 48.76; SD = 15.36), of both sexes (Men = 34.8%; Women = 65.2%). Participants were born in Argentina (54.3%), Bolivia (0.5%), Chile (7.1%), Colombia (17.3%), Costa Rica (1.5%), Cuba (0.5%), Ecuador (1.5%), Guatemala (0.5%), México (2%), Perú (4.6%), República Dominicana (0.5%), Uruguay (5.6%), and Venezuela (4.1%), all countries sharing a language and a broad social and cultural identity (Vergara et al., 2010; Campos-Winter, 2018). Migration dates ranged from 1963 to 2019 (M = 12.16 years; SD = 11.62 years).

Measures

Brief Centrality of Event Scale

The Brief Centrality of Event Scale (CES; Berntsen and Rubin, 2006) is a seven-item self-administered questionnaire that gauges how central an event is to a person’s identity and life-story (e.g., “I feel that this event has become part of my identity”/“Siento que este evento se ha transformado en parte de mi identidad”). In this study, it was specified that participants should focus on the event of migration to Israel. Responses are given via a Likert-type scale with five anchors ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 5 = “totally agree.” For the purposes of the present study, a version was validated and adapted to the Argentine context by Simkin et al. (2017), which reported adequate internal consistency (α = 0.86) and fit statistics [CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.6, and CI (0.03, 0.08)]. In the current study sample, CES has also shown adequate internal consistency (ω = 0.90) and fit statistics [CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, and CI (0.0, 0.1)].

Affect Balance Scale

The Affect Balance Scale (ABS; Warr et al., 1983) is an 18-item self-administered questionnaire measuring both positive (e.g., “Have you felt very happy?”/“¿Te has sentido muy alegre?”) and negative (e.g., “Have you felt like crying?”/“¿Te has sentido con ganas de llorar?”) affective experiences. Responses are given via a Likert-type scale with five anchors ranging from 1 = “never” to 5 = “very frequently.” For the purposed of the present study, a version was validated and adapted to the Argentine context by Simkin et al. (2016), which reported adequate internal consistency for both positive (α = 0.77) and negative affect (α = 0.86), and fit statistics [CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.5, and CI (0.04, 0.06)]. In the current sample, ABS has also shown adequate internal consistency for both positive (ω = 0.90) and negative affect (ω = 0.81), and fit statistics [CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.07, and CI (0.06, 0.08)].

Satisfaction With Life Scale

Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) is a five-item self-administered questionnaire that measures satisfaction with life (e.g., “The conditions of my life are excellent”/“Las condiciones de mi vida son excelentes”). Responses are given via a Likert-type scale with seven anchors ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree.” For the purposes of the present study, the version validated and adapted to the Argentine context by Moyano et al. (2013) was used, which reported adequate internal consistency (α = 0.75). In the current sample, SWLS also shown adequate internal consistency (ω = 0.90) and fit statistics [CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, and CI (0.0, 0.1)].

Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments Scale

Assessment of Spirituality and Religious Sentiments Scale (ASPIRES-SF; Piedmont, 2010) is a 35-item self-report questionnaire that measures Religious Sentiments and Spiritual Transcendence. On the one hand, Religious Sentiment consists of two dimensions: Religious Involvement (e.g., “How often do you pray?”/“¿Cuán seguido reza?”) and Religious Crisis (e.g., “I feel that God is punishing me”/“Siento que Dios me está castigando”). Spiritual Transcendence, on the other, includes three further dimensions: Prayer Fulfillment (e.g., “I find inner strength and/or peace from my prayers or meditations”/“Encuentro fuerza interior y/o paz en mis rezos y/o meditaciones”), Universality (e.g., “I feel that on a higher level all of us share a common bond”/“Siento que en un nivel superior todos compartimos un vínculo común”), and connectedness (“Although they are dead, memories, and thoughts of some of my relatives continue to influence my current life”/“Aunque ya fallecidos, recuerdos y pensamientos de algunos de mis parientes continúan influenciando mi vida actual”). The version used in this study was adapted to the Argentine context by Simkin (2017), with reported adequate internal consistency for Religious Involvement (α = 0.84), Religious Crisis (α = 0.68), Prayer Fulfillment (α = 0.91), Universality (α = 0.76), and Connectedness (α = 0.57), and adequate fit statistics reported both for Religious Sentiments [CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.037, and CI (0.000, 0.060)] and Spiritual Transcendence [CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.069, and CI (0.062, 0.076)]. In the current study sample, ASPIRES also shown adequate internal consistency for Religious Involvement (ω = 0.95), Religious Crisis (ω = 0.91), Prayer Fulfillment (ω = 0.83), Universality (ω = 0.84), and Connectedness (ω = 0.64), and adequate fit statistics both for Religious Sentiments [CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.007, CI (0.004, 0.009)] and Spiritual Transcendence [CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.007, and CI (0.006, 0.008)].

Procedure

A non-probability sampling was carried out to select the cases. Participants were invited to collaborate voluntarily, and their consent was obtained. It was explained to the respondents that the data gathered from the study would be used exclusively for scientific purposes according to the code of ethics established by the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET; Res. D No. 2857/06), and under Argentina’s National Law 25,326.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (Armonk, NY, United States) and EQS 6.4 (Byrne, 1994; Bentler, 2006) for Windows. Goodness of fit for the regression models considered R as an indicator of the effect size and R 2 adjusted as an indicator of total variance (Freiberg and Fernández Liporace, 2015; Darlington and Hayes, 2016; Schroeder et al., 2016). The models’ assumptions of multicollinearity, homoscedasticity of the residuals, and non-autocorrelation were tested to confirm its goodness of fit (Freiberg and Fernández Liporace, 2015). The Durbin-Watson statistic was used to examine the non-autocorrelation – with possible values ranging from 0 to 4, assuming the independence of the residuals, with values in this study lying between 1.30 and 1.75. Likewise, condition index and variance inflation factor (VIF) were used in the diagnosis of multicollinearity, the former being below 30 and the latter below 10.

Results

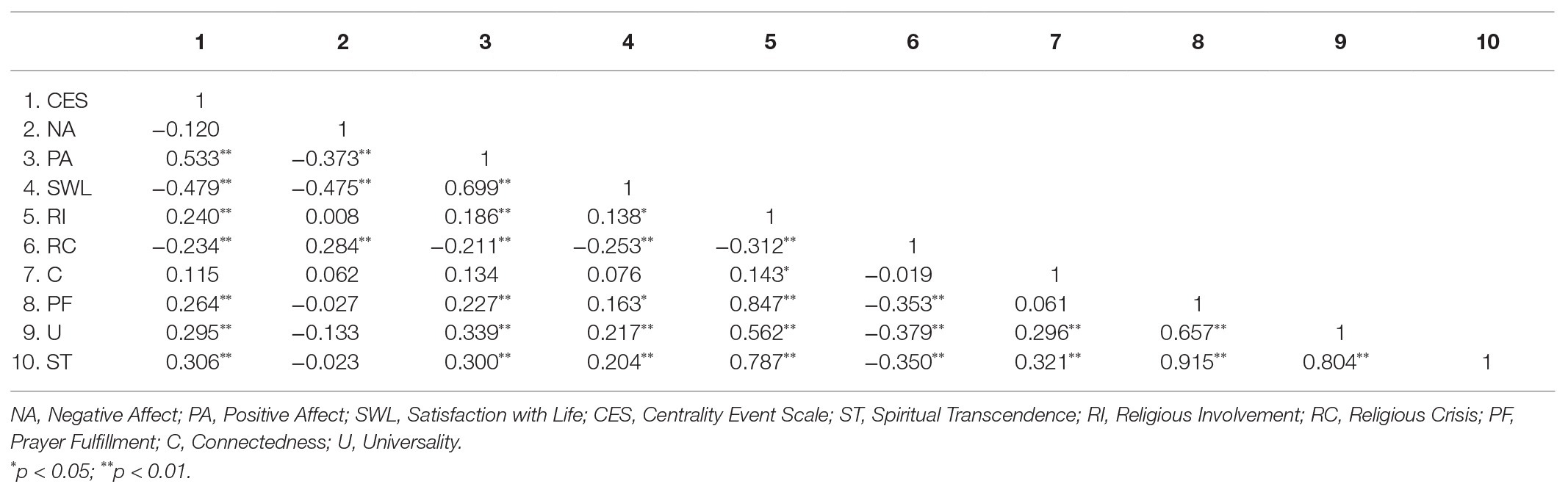

A correlational analysis was conducted to examine the associations between the variables under study (Cohen et al., 1983; Curtis et al., 2016). The results shown in Table 1 suggest Centrality of Events is associated with Positive Affect, Satisfaction with Life, Religious Involvement, Religious Crisis, Prayer Fulfillment, Universality, and Spiritual Transcendence (Table 1).

Three regression models were subsequently tested, including Positive Affect, Negative Affect, and Satisfaction with Life as dependent variables, and Centrality of Event, Spiritual Transcendence, and Religious Crisis as independent variables.

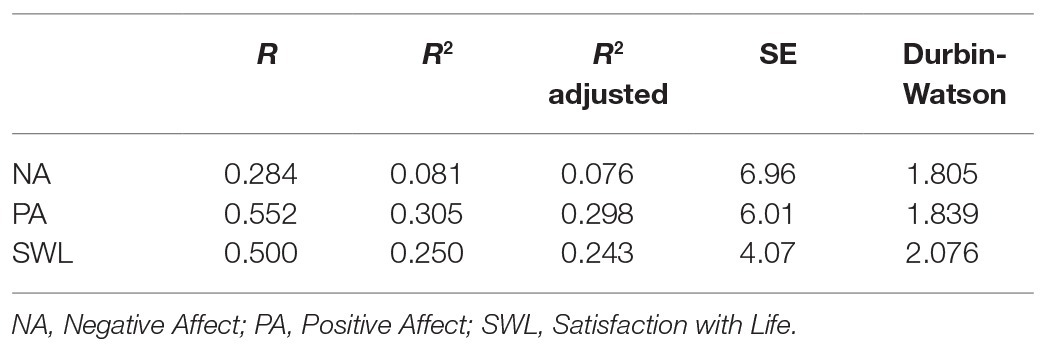

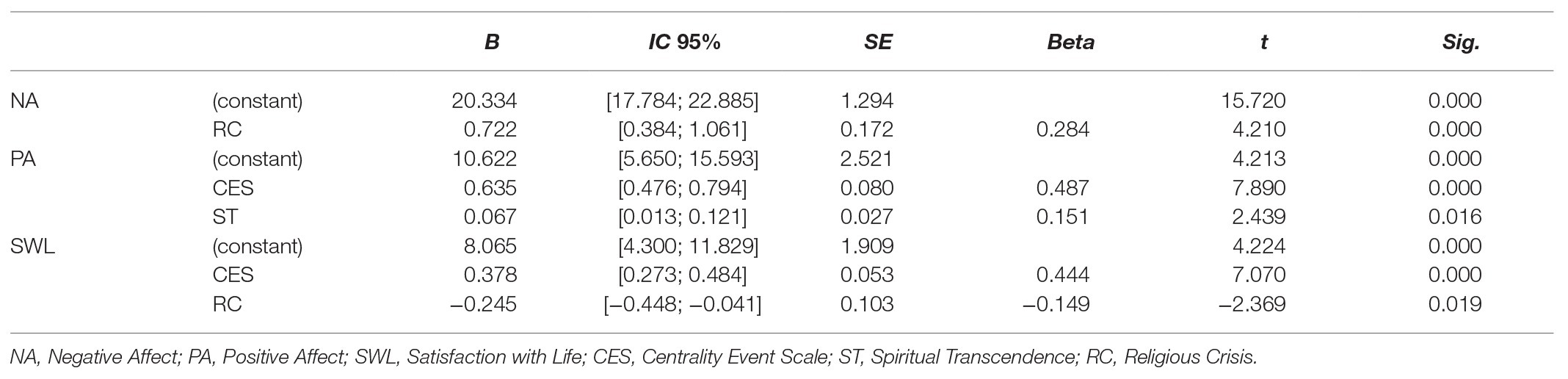

A stepwise regression analysis with backward method was used to address the research questions. Three models were obtained, in which Negative Affect was predicted by Religious Crisis, Positive Affect was predicted by Centrality of Events and Spiritual Transcendence, and Satisfaction with Life was predicted by Centrality of Event and Religious Crisis (Berlanga-Silvente and Vilà-Baños, 2014; Hayes and Rockwood, 2017) (Table 2).

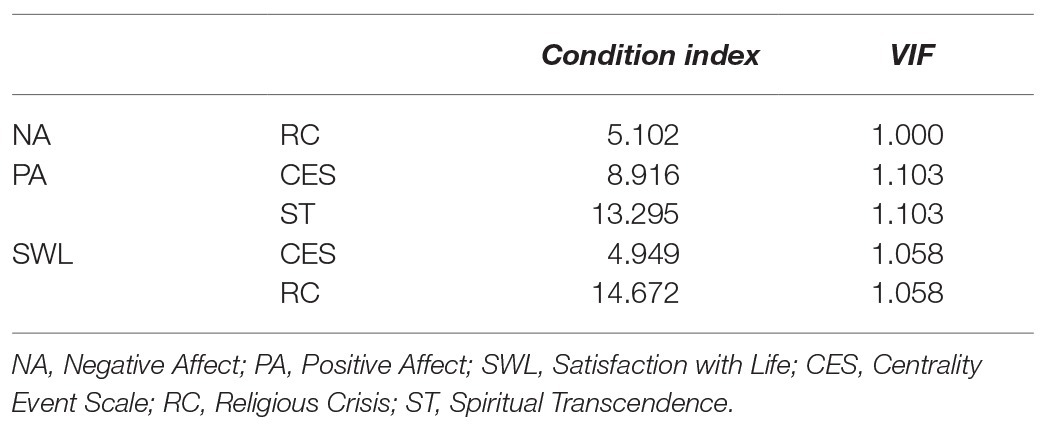

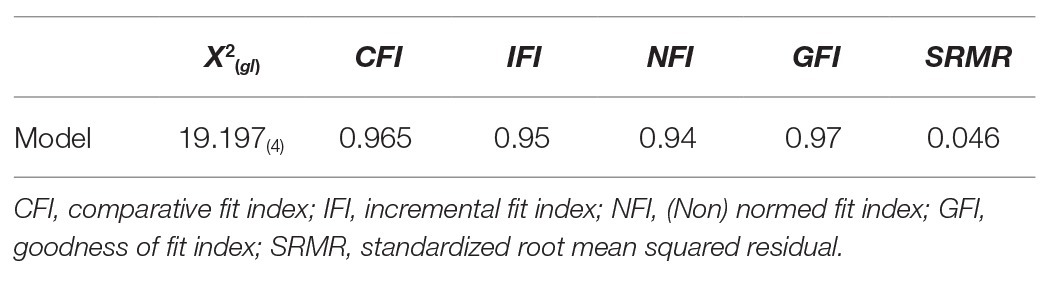

As can be seen in Tables 2 and 3, the model’s goodness of fit has been verified (Table 3).

The results show that, when analyzing the effects on SWB, Positive Affect, and Negative Affect, and Centrality of Event, Religious Crisis, and Spiritual Transcendence appear as the most relevant explanatory variables in the models (Table 4).

Finally, the relations between Centrality of Events, Religion, Spirituality, and SWB in Latin American Jewish Immigrants in Israel were tested using structural equation modeling, evaluated from the CFA model fitting solution by the Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR), as it is suggested for continuum variables (Shi et al., 2018; Pavlov et al., 2020). The results indicated a good model fit (Table 5).

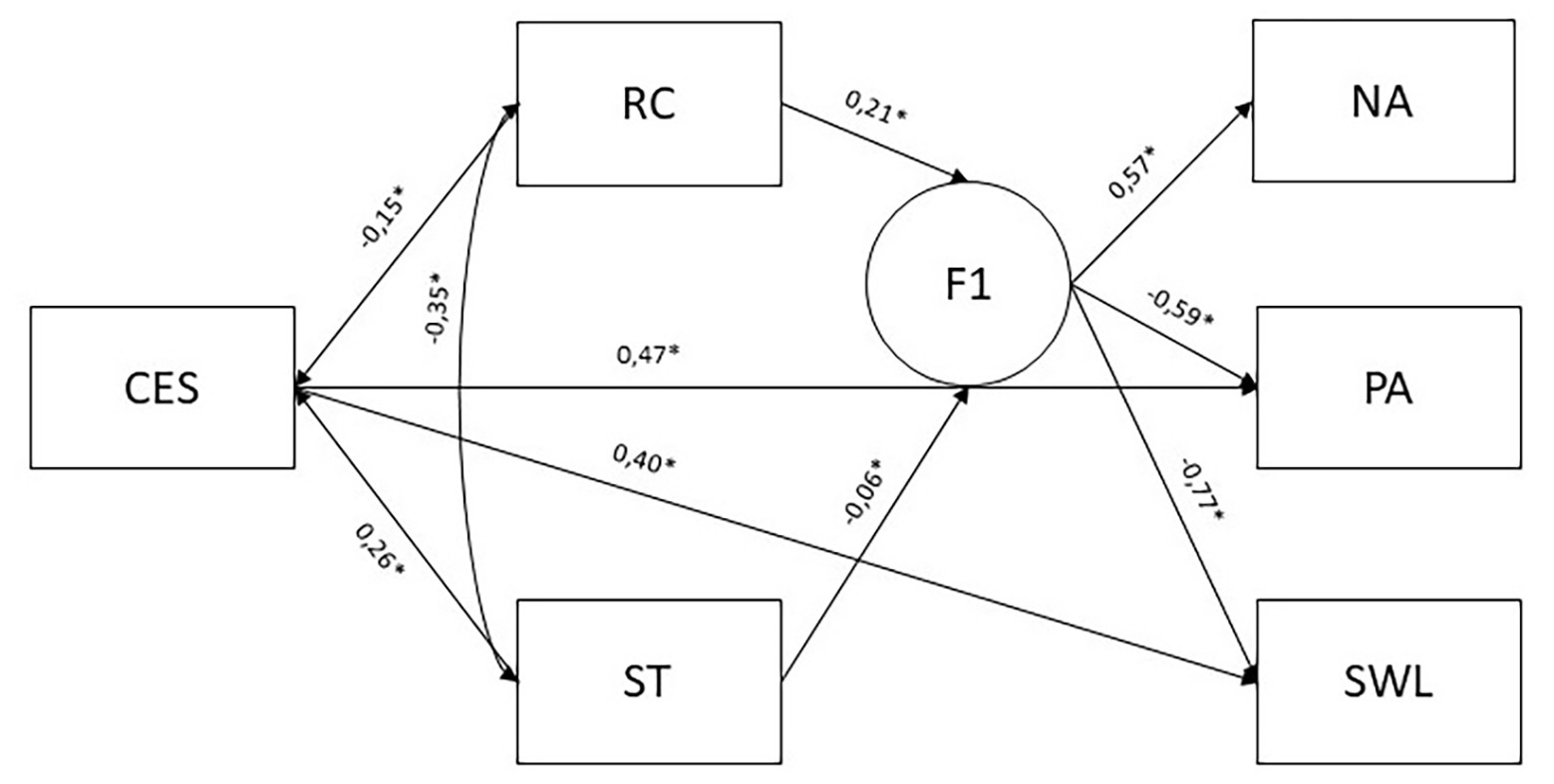

Figure 1 represents the path model and the different loadings among each latent construct.

Figure 1. Structural model of Spiritual Transcendence, Religious Crisis, and Centrality of Event predicting Subjective Well-Being, with standardized estimates. NA, Negative Affect; PA, Positive Affect; SWL, Satisfaction with Life; CES, Centrality Event Scale; ST, Spiritual Transcendence; RC, Religious Crisis.

Concordant with the regression analyses, Centrality of Event, Religious Crisis, and Spiritual Transcendence appears as the most relevant variables explaining SWB – both Positive and Negative Affects.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the impact of migration as a central event in Personal Identity, Spirituality, and Religiousness on SWB. First, our research contributes both to the literature on psychological studies of migration and the psychology of religion.

For psychological research on migration, Centrality of Event plays a significant role in a deeper understanding of the relevance of migration experiences in immigrants’ personal identities. This could partially explain the associations between migration and well-being. Indeed, more research on the relationship between migration and SWB is needed, given that most studies in the field focus on anxiety, depression, or PTSD, as the deficit model that has dominated psychology for decades (Cobb et al., 2019). It is therefore necessary to consider the positive effects of migration on individuals, which can contribute to the development of different facets of identity and psychological well-being. Migration can contribute to personal growth and the achievement of new life opportunities. If the early stages can lead to high levels of anxiety about uncertainty at the same time, they can promote new life projects (Bobowik et al., 2015).

For the psychology of religion – and especially for lines of research focusing on the relationship between religion and SWB (Demir, 2019) – migration to Israel is also a relevant topic, both because of the role of spiritual and religious beliefs linked to the process of migration to Israel, and the stressful conditions in migration processes that could be harmful to well-being.

Centrality of Event and Subjective Well-Being

The results show migration to Israel to be a central event in the identities of Jewish Latin American immigrants. However, contrary to expectations, the present study has identified positive associations between the centrality of migration and SWB. According to the literature on the latter, traumatic and strongly negative events are not as frequently experienced as positively or neutrally perceived events, except for those who experience extremely negative life circumstances (Diener and Diener, 1996; Diener et al., 2018). In this light, “positive” and “negative” perceptions of migration to Israel as a central event may be mediated by motivations for emigration. As mentioned above, ideological and religious reasons have been mentioned among Latin Americans’ motivations for emigration to Israel alongside anti-Semitism and financial and political factors (Rein, 2010, 2013; Siebzehner, 2010, 2016; Klor, 2016). Similar motivations were identified by Tartakovsky and Schwartz (2001) as they developed the Motivation for Emigration Scale, focused on Russian Migrants to Israel. Hence, as there are no precedents for similar measures among Latin American migrants, new scales are needed to advance along this line of research. Furthermore, for a deeper understanding of motivations behind emigration, it is also important to explore not only motivations behind emigrations but also the historical events that have triggered them, specifically for those who emigrate because of anti-Semitism or for political or economic reasons.

An understanding of Latin Americans’ motivations for emigration could go some way to explaining the relationship between the centrality of migration and SWB, but there are other factors not yet properly studied within social psychology that are also relevant to this line of research. As Babis (2016) has pointed out, post-migration stressors for Latin Americans are strong and go beyond language barriers: the integration/isolation process among immigrants is relevant to the community as a whole. Even though acculturation has been widely studied among immigrants in Israel, most of the research has focused on Russians (Roccas et al., 2000; Tartakovsky, 2012) and Africans (Nakash et al., 2015, 2016). Acculturation is particularly relevant in Israel, as intergroup conflict is high in that country (Ditlmann and Samii, 2016; Dugas et al., 2018). Exploring Latin Americans’ perceptions of intergroup conflict in Israel could also be relevant to understanding the relationships between centrality of events, acculturation, and SWB.

Finally, as Argentines are the largest groups among Latin Americans, most research focuses on them. Future studies should focus on identifying the singularities of migratory experiences according to the specificities of each country.

Religion, Spirituality, and Subjective Well-Being

As expected, where religion and spirituality are concerned, Religious Crisis and Spiritual Transcendence played an important role in explaining Satisfaction with Life, Positive Affect, and Negative Affect (Piedmont, 2012; Piedmont and Friedman, 2012). Because of the study’s small sample size (Kline, 2016; Goodboy and Kline, 2017), future studies should explore how motivations for emigration, centrality of events, spiritualty, religion, and well-being interact with each other within larger samples (N > 400; Kline, 2016; Medrano and Muñoz-Navarro, 2017).

Conclusion

Migration to Israel could be considered a Central Event in Migrants’ Identities, having either a positive or negative impact on well-being. Future research is needed to elucidate what variables might be mediating this association. First, this study has only focused on SWB, but “negative” mental health variables such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD should be explored as much as “positive” mental health variables such as Psychological and SWB (Cobb et al., 2019). Second, motivations for emigration should be explored as they may be mediating the relationship between centrality of events and mental health. Third, other variables should be considered within this model. Acculturation and perception of intergroup conflict may be two of the most important related variables. Fourth, religion and spirituality play a specific role in the specific case of migration to Israel and await further assessment. Last, as most studies among Latin Americans focus on Argentines, more research is needed to explore other countries’ migration singularities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Universidad de Buenos Aires, ethics committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

HS devised the structure, analyzed the literature, ran the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This study was conducted within UBACyT 20020170200395BA and PICT-2016-4147, funded by the University of Buenos Aires and the National Agency for Scientific and Technological Promotion (ANPCyT). Funding from Tel Aviv University was obtained to present preliminary results at the international conference, “Migrants, Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Migration to Latin America,” held June 5–June 6, 2019 at the S. Daniel Abraham Center for International and Regional Studies.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the invitation from Raanan Rein (Tel Aviv University) and Stefan Rinke (Freie Universität Berlin) to present initial outcomes on the international conference, “Migrants, Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Migration to Latin America,” held June 5–June 6, 2019 at the S. Daniel Abraham Center for International and Regional Studies.

References

Abu-Raiya, H., Sasson, T., Pargament, K. I., and Rosmarin, D. H. (2020). Religious coping and health and well-being among jews and muslims in Israel. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 30, 202–215. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2020.1727692

Babis, D. (2016). The paradox of integration and isolation within immigrant organisations: the case of a Latin American Association in Israel. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 42, 2226–2243. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1166939

Baerger, D. R., and McAdams, D. P. (1999). Life story coherence and its relation to psychological well-being. Narrat. Inq. 9, 69–96. doi: 10.1075/ni.9.1.05bae

Berlanga-Silvente, V., and Vilà-Baños, R. (2014). Cómo obtener un modelo de regresión logística binaria con SPSS. REIRE. Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació 7, 105–118. doi: 10.1344/reire2014.7.2727

Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 27, 169–190. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

Berntsen, D., and Rubin, D. C. (2006). The centrality of event scale: a measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009

Bobowik, M., Basabe, N., and Páez, D. (2015). The bright side of migration: hedonic, psychological, and social well-being in immigrants in Spain. Soc. Sci. Res. 51, 189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.09.011

Braganza, D., and Piedmont, R. L. (2015). The impact of the core transformation process on spirituality, symptom experience, and psychological maturity in a mixed age sample in India: a pilot study. J. Relig. Health 54, 888–902. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0049-y

Brooks, M., Graham-Kevan, N., Lowe, M., and Robinson, S. (2017). Rumination, event centrality, and perceived control as predictors of post-traumatic growth and distress: the cognitive growth and stress model. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 56, 286–302. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12138

Byrne, B. M. (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. California: Sage Publications.

Campos-Winter, H. (2018). Estudio de la identidad cultural mediante una construcción epistémica del concepto identidad cultural regional. Cinta de moebio 62, 199–212. doi: 10.4067/S0717-554X2018000200199

Cerniglia, L., and Cimino, S. (2012). Minori immigrati ed esperienze traumatiche: una rassegna teorica sui fattori di rischio e di resilienza. Infanzia e adolescenza 11, 1–24.

Cobb, C. L., Branscombe, N. R., Meca, A., Schwartz, S. J., Xie, D., Zea, M. C., et al. (2019). Toward a positive psychology of immigrants. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14, 619–632. doi: 10.1177/1745691619825848

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., and Aiken, L. S. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Psychology Press.

Curtis, E. A., Comiskey, C., and Dempsey, O. (2016). Importance and use of correlational research. Nurs. Res. 23, 20–25. doi: 10.7748/nr.2016.e1382

Darlington, R. B., and Hayes, A. F. (2016). Regression analysis and linear models: Concepts, applications, and implementation. New York: The Guilford Press.

Dein, S., Cook, C. C. H., and Koenig, H. G. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and mental health: current controversies and future directions. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 200, 852–855. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31826b6dle

Demir, E. (2019). The evolution of spirituality, religion and health publications: yesterday, today and tomorrow. J. Relig. Health 58, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10943-018-00739-w

Diener, E., and Diener, C. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychol. Sci. 7, 181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00354.x

Diener, E., Diener, C., Choi, H., and Oishi, S. (2018). Revisiting “most people are happy”—and discovering when they are not. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 166–170. doi: 10.1177/1745691618765111

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Ditlmann, R. K., and Samii, C. (2016). Can intergroup contact affect ingroup dynamics? Insights from a field study with jewish and Arab-palestinian youth in Israel. Peace Confl. 22, 380–392. doi: 10.1037/pac0000217

Dugas, M., Schori-Eyal, N., Kruglanski, A. W., Klar, Y., Touchton-Leonard, K., McNeill, A., et al. (2018). Group-centric attitudes mediate the relationship between need for closure and intergroup hostility. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 21, 1155–1171. doi: 10.1177/1368430217699462

Finklestein, M., and Solomon, Z. (2009). Cumulative trauma, PTSD and dissociation among ethiopian refugees in Israel. J. Trauma Dissociation 10, 38–56. doi: 10.1080/15299730802485151

Foster, R. P. (2001). When immigration is trauma: guidelines for the individual and family clinician. Am. J. Orthop. 71, 153–170. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.2.153

Freiberg, A., and Fernández Liporace, M. (2015). Estilos de aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios ingresantes y avanzados de Buenos Aires. Liberabit 21, 71–79.

Gal, S. (2020). “Childhood experiences of anti-Semitism in Argentina (1976–1983): stories of Trauma, resilience, and long-term outcome” in Anti-semitism and psychiatry. Recognition, prevention, and interventions. eds. H. S. Moffic, J. R. Peteet, A. Hankir, and M. V. Seeman (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 279–293.

Galen, L. (2015). Atheism, wellbeing, and the wager: why not believing in god (with others) is good for you. Sci. Relig. Cult. 2, 54–69. doi: 10.17582/journal.src/2015/2.3.54.69

Gehrt, T. B., Berntsen, D., Hoyle, R. H., and Rubin, D. C. (2018). Psychological and clinical correlates of the centrality of event scale: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 65, 57–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.07.006

Goodboy, A. K., and Kline, R. B. (2017). Statistical and practical concerns with published communication research featuring structural equation modeling. Commun. Res. Rep. 34, 68–77. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2016.1214121

Hashemi, N., Marzban, M., Sebar, B., and Harris, N. (2019). Acculturation and psychological well-being among middle eastern migrants in Australia: the mediating role of social support and perceived discrimination. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 72, 45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.07.002

Hayes, A. F., and Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 98, 39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001

Kalir, B. (2015). The jewish state of anxiety: between moral obligation and fearism in the treatment of african asylum seekers in Israel. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 41, 580–598. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2014.960819

Kao, L. E., Peteet, J. R., and Cook, C. C. H. (2020). Spirituality and mental health. J. Study Spiritual. 10, 42–54. doi: 10.1080/20440243.2020.1726048

Khursheed, M., and Shahnawaz, M. G. (2020). Trauma and post-traumatic growth: spirituality and self-compassion as mediators among parents who lost their young children in a protracted conflict. J. Relig. Health. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-00980-2 [Epub ahead of print]

Kim, C. Y., Kim, S., and Blumberg, F. (2020). Attachment to god and religious coping as mediators in the relation between immigration distress and life satisfaction among Korean Americans. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 1–18. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2020.1748295

King, M., Marston, L., McManus, S., Brugha, T., Meltzer, H., and Bebbington, P. (2013). Religion, spirituality and mental health: results from a national study of English households. Br. J. Psychiatry 202, 68–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112003

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th Edn. New York: The Guilford Press.

Klor, S. (2016). “Marginal immigrants”: jewish-argentine immigration to the state of Israel, 1948–1967. Isr. Stud. 21, 50–76. doi: 10.2979/israelstudies.21.2.03

Koenig, H. G., King, D., and Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. London: Oxford University Press.

Krupnik, A. (2011). “Cuando camino al Kibbutz vieron pasar al Che” in Marginados y Consagrados. Nuevos Estudios sobre la vida judía en la Argentina. eds. E. Kahan, L. Schenquer, D. Setton, and A. Dujovne (Lumiere: Buenos Aires), 311–328.

Krupnik, A. (2020). Migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in Latin America. eds. R. Rein, S. Rinke, and D. M. K. Sheinin (Leiden: Brill), 160–188.

Le, Y. K., Piedmont, R. L., and Wilkins, T. A. (2019). Spirituality, religiousness, personality as predictors of stress and resilience among middle-aged Vietnamese-born American Catholics. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 22, 754–768. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2019.1646235

Lesser, J. (2016). “Jews and Judaism in Latin America” in The Cambridge history of religions in Latin America. eds. V. Garrard-Burnett, P. Freston, and S. C. Dove (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 709–713.

Medrano, L. A., and Muñoz-Navarro, R. (2017). Aproximación conceptual y práctica a losModelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria 11, 219–239. doi: 10.19083/ridu.11.486

Moyano, N. C., Martínez Tais, M., Muñoz, M., and del, P. (2013). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de satisfacción con la vida de diener. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica 22, 191–168.

Nakash, O., Nagar, M., and Lurie, I. (2016). The association between postnatal depression, acculturation and mother–infant bond among eritrean asylum seekers in Israel. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 18, 1232–1236. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0348-8

Nakash, O., Nagar, M., Shoshani, A., and Lurie, I. (2015). The association between acculturation patterns and mental health symptoms among Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers in Israel. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 21, 468–476. doi: 10.1037/a0037534

Pavlov, G., Maydeu-Olivares, A., and Shi, D. (2020). Using the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) to assess exact fit in structural equation models. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 0013164420926231. doi: 10.1177/0013164420926231

Piedmont, R. L. (2009). “The contribution of religiousness and spirituality to subjective wellbeing and satisfaction with life” in International handbook of education for spirituality, care and wellbeing. Vol. 3. eds. M. Souza, L. J. Francis, J. O’Higgins-Norman, and D. Scott (Springer Netherlands), 89–105.

Piedmont, R. L. (2010). Assessment of spirituality and religious sentiments. Technical manual. 2nd Edn. Author.

Piedmont, R. L. (2012). “Overview and development of measure of numinous constructs: the assessment of spirituality and religious sentiments (ASPIRES) scale” in The oxford handbook of psychology and spirituality. ed. L. J. Miller (Oxford University Press), 104–122.

Piedmont, R. L., and Friedman, P. H. (2012). “Spirituality, religiosity, and subjective quality of life” in Handbook of social indicators and quality of life research. eds. K. C. Land, A. C. Michalos, and M. J. Sirgy (Springer Netherlands), 313–329.

Pirutinsky, S., Rosmarin, D. H., and Kirkpatrick, L. A. (2019). Is attachment to god a unique predictor of mental health? Test in a jewish sample. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 29, 161–171. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2019.1565249

Rein, R. (2001). The eichmann kidnapping: its effects on argentine-Israeli relations and the local jewish community. Jew. Soc. Stud. 7, 101–130. doi: 10.1353/jss.2001.0016

Rein, R. (2010). Argentine jews or jewish Argentines?: Essays on ethinicity, identity, and diaspora. Leiden: Brill.

Rein, R. (2013). Searching for home abroad: jews in Argentina and argentines in Israel. Historie–Otázky–Problémy 5, 155–169.

Roccas, S., Horenczyk, G., and Schwartz, S. H. (2000). Acculturation discrepancies and well-being: the moderating role of conformity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 30, 323–334. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(200005/06)30:3<323::AID-EJSP992>3.3.CO;2-X

Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Carp, S., Appel, M., and Kor, A. (2017). Religious coping across a spectrum of religious involvement among jews. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 9, 96–104. doi: 10.1037/rel0000114

Schroeder, L. D., Sjoquist, D. L., and Stephan, P. E. (2016). Understanding regression analysis. Los Angeles: Sage.

Shi, D., Maydeu-Olivares, A., and DiStefano, C. (2018). The relationship between the standardized root mean square residual and model misspecification in factor analysis models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 53, 676–694. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2018.1476221

Shilo, G., Yossef, I., and Savaya, R. (2016). Religious coping strategies and mental health among religious jewish gay and bisexual men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 45, 1551–1561. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0567-4

Siebzehner, B. (2010). “Un imaginario inmigratorio: ideología y pragmatismo entre los latinoamericanos en Israel” in Pertenencia y Alteridad: Los Judíos en América Latina. eds. H. Avni, J. B. Liwerant, S. Della Pergola, A. M. Bejerano, and L. Senkman (Madrid: Iberoamericana Editorial Vervuert), 389–416.

Siebzehner, B. (2016). Destellos de nostalgia: inmigrantes ideológicos de América Latina en el Israel de hoy. Cuadernos Judaicos 33, 301–322. doi: 10.5354/0718-8749.2019.52335

Sigamoney, J. (2018). Resilience of somali migrants: religion and spirituality among migrants in Johannesburg. Altern. J. 22, 81–102. doi: 10.29086/2519-5476/2018/sp22a5

Simkin, H. (2017). Adaptación y Validación al español de la Escala de Evaluación de Espiritualidad y Sentimientos Religiosos (ASPIRES): la trascendencia espiritual en el modelo de los cinco factores. Universitas Psychologica 16, 1–12. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.upsy16-2.aeee

Simkin, H., Matrángolo, G., and Azzollini, S. (2017). Validación argentina de la Escala Abreviada de Centralidad del Evento. Subjetividad y Procesos Cognitivos 21, 205–216.

Simkin, H., Olivera, M., and Azzollini, S. (2016). Validación argentina de la Escala de Balance Afectivo. Revista de Psicología 25, 1–17.

Staugaard, S. R., Johannessen, K. B., Thomsen, Y. D., Bertelsen, M., and Berntsen, D. (2015). Centrality of positive and negative deployment memories predicts posttraumatic growth in danish veterans. J. Clin. Psychol. 71, 362–377. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22142

Sznajder, M. (2015). From Argentina to Israel: escape, evacuation and exile. J. Lat. Am. Stud. 37, 351–377. doi: 10.1017/S0022216X05009041

Tartakovsky, E. (2012). Factors affecting immigrants’ acculturation intentions: a theoretical model and its assessment among adolescent immigrants from Russia and Ukraine in Israel. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 36, 83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.02.003

Tartakovsky, E., Patrakov, E., and Nikulina, M. (2017). The emigration intentions of Russian Jews: the role of socio-demographic variables, social networks, and satisfaction with life. East Eur. Jew. Aff. 47, 242–254. doi: 10.1080/13501674.2017.1396175

Tartakovsky, E., and Schwartz, S. H. (2001). Motivation for emigration, values, wellbeing, and identification among young Russian Jews. Int. J. Psychol. 36, 88–99. doi: 10.1080/00207590042000100

Vathi, Z., and King, R. (eds.) (2017). Return migration and psychosocial wellbeing: Discourses, policy-making and outcomes for migrants and their families. London: Routledge.

Vergara, J. I., Vergara Estévez, J., and Gundermann, H. (2010). Elementos para una teoría crítica de las identidades culturales en América Latina. Utopia y Praxis Latinoamericana 15, 57–79.

Vermeulen, M., Smits, D., Boelen, P. A., Claes, L., Raes, F., and Krans, J. (2019). The Dutch version of the centrality of event scale (CES): associations with negative life events, posttraumatic stress, and depression symptoms in a student population. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 36, 361–371. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000517

Warr, P. B., Barter, J., and Brownbridge, G. (1983). On the independence of positive and negative affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 44, 644–651. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.3.644

Watson, L. A., and Dritschel, B. (2015). “The role of self during autobiographical remembering and psychopathology: evidence from philosophical, behavioral, neural, and cultural investigations” in Clinical perspectives on autobiographical memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 335–358.

Keywords: migration, centrality of events, religion, spirituality, subjective well-being

Citation: Simkin H (2020) The Centrality of Events, Religion, Spirituality, and Subjective Well-Being in Latin American Jewish Immigrants in Israel. Front. Psychol. 11:576402. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.576402

Edited by:

Dario Paez, University of the Basque Country, SpainReviewed by:

Marian Perez-Marin, University of Valencia, SpainNekane Basabe, University of the Basque Country, Spain

Copyright © 2020 Simkin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hugo Simkin, aHVnb3NpbWtpbkBzb2NpYWxlcy51YmEuYXI=orcid.org/0000-0001-7162-146X

Hugo Simkin

Hugo Simkin