- The School of Creative Arts Therapies, Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

This research encompasses a systematic scoping review of literature and research pertaining to the open studio approach to art therapy, which originated with the work of artists in psychiatric hospitals in the 1940's. As art therapy became a profession, it sought recognition by adopting theories from other therapeutic disciplines. Today, however, there is an increase in the prevalence of studio practice that emphasizes art as the core of the therapeutic work; moreover, contemporary art therapy approaches even venture beyond the traditional definition of the profession to the realm of social action. Consequently, open studio practice has become more widespread and is currently implemented in many different contexts among a wide range of populations. The purpose of this research was to accurately map out world literature and research on the open studio approach to art therapy as well as identify relevant publications and main themes. Therefore, the systematic scoping review was not restricted to specific periods, languages, settings, or populations. Publications were identified through a rigorous, replicable, and extensive search of international literature in data bases and hand searches in art therapy journals; in addition, special efforts were made to locate unpublished research and literature. Data was charted using a tool developed by the researchers, based on the review questions. Results indicate that most of the literature relating to the open studio approach dates from the 1990's: only a few earlier publications were found. Over the last decade, the literature has grown in volume in comparison to previous decades, reflecting an increasing prevalence of the open studio approach. This growing mass of publications reflects an historic development in the field of art therapy. This research also identifies core principles as well as a wide range of variations on the open studio model, in addition to unique characteristics that vary according to context and therapeutic approach. It explores open studio practice within different settings and populations and pinpoints gaps of knowledge that can indicate the need for further research.

Introduction

The open studio approach to art therapy positions art as the focus of the therapeutic work (Moon, 2016). It originates from the early days of the art therapy profession, when artists, influenced by humanistic approaches to psychiatry, brought the studio into psychiatric hospitals (Hogan, 2001). As the art therapy profession evolved, it adopted theories from clinical psychology in order to gain recognition; Allen (1992) termed this the “clinification syndrome.” Following developments in recent decades in the field of art therapy, open studio practices have become more diverse and more prevalent in a wider range of contexts (Kapitan, 2008). This article presents a systematic scoping review of existing literature and research pertaining to the open studio approach to art therapy. It seeks to map out variations and common core principles of the practice as well as unique aspects that emerge from a range of contexts and therapeutic approaches.

What is the Open Studio Approach to Art Therapy?

In 1946, Edward Adamson began to work as an “art master” at the Netherne Psychiatric Hospital in the south of London. The hospital's head psychiatrist, Dr. E. Cunningham Dax, asked him to open an art studio to research the role of art in diagnosis and treatment (Hogan, 2001). His vague job description did not fall within the realms of occupational therapist or art teacher, and this perhaps gave him an opportunity to offer the patients a space where they could express themselves through artistic creation and a deferential and non-invasive approach that respected the patient's autonomy (Pitman, 2016). Mary Huntoon also began her work the same year at the Winter VA Hospital in Topeka, Kansas. Both an artist and art teacher, she established a studio at the hospital that served as a space in which patients could express themselves through artmaking. In 1947, she received a grant to research the “studio as laboratory for research observation,” and even organized hospital exhibitions of her patients' artwork. The guiding principle of her work was that artistic creation has therapeutic value (Wix, 2000).

The open studio reflects the art as therapy approach, in which the artistic processes and outcomes are central to the therapeutic work and incorporate healing qualities (Kramer, 2000), as opposed to other approaches, in which art serves as a foundation for an interpretative process based on theories from various disciplines. The main features of the open studio approach emphasize artistic creation and provide the venue and conditions for this process. The artmaking process is not directed or moderated by the facilitators, and the sessions, deliberately longer than clinical sessions, enable profound engagement and sufficient time for the creative process to evolve. The nature of the space and its organization are vitally important to the establishment of a welcoming and enabling atmosphere. The emphasis is on the individual's creative process in a group setting that represents communality (Allen, 1995; Malchiodi, 1995; McNiff, 1995; Shapiro, 2014; Moon, 2016). Allen (1983) conceived the term “open studio” to describe a model of group art therapy that she implemented in a short-term psychiatric unit; the model offered participants the freedom to choose to take part and engage in artmaking, and she herself would participate in the artmaking alongside them. These ideas emerged out of Allen's exploration of her roots as an artist and her vision of the centrality of art in the therapeutic process (Allen, 1995). Moon (2016) explores the meaning of the word “open” as it is used in “open studio,” and suggests that this openness is reflected in different aspects, such as the freedom to choose the materials; the process that is neither steered or moderated; and the open and optional invitation that allows the participant to choose whether to participate and for how long. This openness is also present in community-based models, which are open to anyone who wants to participate, and no screening or intake processes are involved. Openness can also refer to the facilitation process, in which facilitators are full partners as they engage in artmaking alongside participants (Moon, 2016).

Open studio practice allows participants to work at their own pace, regulate their interactions with other participants according to their abilities, and use the group and the space according to their needs. This approach incorporates aspects of a community life where individuals live together and separately (Deco, 1998). The community aspect, together with the space for individual expression and the therapeutic benefits of artistic creation, make this model also relevant beyond the clinical setting. Over time, the open studio has moved from within the confines of the psychiatric hospital and is implemented in diverse forms and in many settings. For example, Kapitan (2008) describes the use of art as a means for healing communities in regions hit by catastrophe and trauma; in prisons; and when dealing with children at risk, She challenges the present definition of art therapy, and suggests expanding it to social settings where the healing powers of art can be put to good use. The studio approach, with its inherent communal aspect, is especially suitable for these contexts. Based on the literature, the open studio approach is used in many different social spaces. These range from an open studio project for youth at risk described by Block et al. (2005) and a community-based model of a studio for people with disabilities (Vick and Sexton-Radek, 2008) to other models of community studios such as “art hives,” which are neighborhood spaces for creative work in Canada (Timm-Bottos and Reilly, 2015). Therapeutic models based on the open studio approach are also operated in educational spaces: Henley (1995) asserts the importance of a studio space for art therapy in a school for special education; Heller (2015), who studied an open studio at a school found that participation in an open studio enhanced children's reflective abilities, empowered them and increased their sense of self-efficacy.

As the open studio model has been used in a wide variety of contexts and settings, it has been adapted to the unique needs of different populations. This diversity, enabled by the flexible nature of this approach (reflected in the name “open studio”) underlines the importance of its closer examination, as well as the identification of common core principles and unique features that have emerged from specific contexts or therapeutic approaches.

The Open Studio in Research

Many studies have underlined the contribution of artmaking to an improved quality of life. One study, in which adults were invited to create freely in an open studio-like space, found that the artmaking reinforced positive feelings, reduced negativity and significantly enhanced the sense of self-efficacy (Kaimal and Ray, 2017). Artmaking in rehabilitative settings builds confidence, encourages creativity, and contributes to a greater sense of social belonging and well-being, as well as an enhanced quality of life (Sapouna and Pamer, 2014). Art-based interventions were also found to be helpful in processing grief (Finn, 2003), encouraging expression among children who had experienced trauma (Klorer, 2005), and coping with crisis (Tyson and Baffour, 2004). Open studio research, which is growing and expanding in recent years, focuses for the most part on the therapeutic efficacy of the approach. For instance, a mixed method study that examined the influence of an open studio group on the mood of patients who were hospitalized in an acute care psychiatric setting (Chiu et al., 2015) revealed that negative moods decreased following participation in the group. Griffith, Seymour & Goldberg's mixed method study (2015) demonstrates the positive therapeutic effect of a community-based open studio setting on homeless individuals; it examines the effect of participation in an open studio setting and an art cooperative on life achievement, and suggests art therapy as a therapeutic tool for addressing financial and psycho-social needs of homeless individuals. The researchers found a positive significant correlation between participation in the open studio group and life achievement, i.e., finding a job, rehabilitation, finding housing, initiative and more. In addition, participants who took part in the open studio and sold their artwork through the art cooperative showed a greater increase in life achievement than participants who only attended the open studio. The sale of artwork created in the studio emphasizes the open studio's rehabilitative role, in addition to its therapeutic goals.

The studio approach, which allows for expression of healthy aspects of individual personality, is especially relevant today in light of the prevalence of post-modern approaches to mental health, such as the recovery approach (Anthony, 1993) and the well-being theory (Seligman, 2011), which discard the medical approach and emphasize health and well-being. Moreover, as Allen (1992) asserts, art, as the focus of therapeutic work, anchors the work of the art therapist and reduces the clinification process that characterizes the work of art therapists who work in mental health care systems.

The Systematic Scoping Review

Systematic scoping reviews entail the systematic search and summary of qualitative and quantitative studies, case studies, and articles written on a certain subject (Peters et al., 2015). They are useful when a large body of literature has not yet been reviewed, especially when existing materials are heterogeneous in nature. Systematic scoping reviews identify, evaluate and summarize findings pertaining to all the relevant literature, and, in this way, summarize all current knowledge and make it accessible to professionals in this field (Peters et al., 2015).

The systematic scoping review includes a structured and systematic search for articles and studies according to a pre-determined protocol of search criteria and a systematic representation of the findings (Tricco et al., 2018).

As this is the first systematic review of the open studio approach to art therapy, the systematic scoping review method was chosen because of its methodical and comprehensive compilation of information. While systematic scoping reviews mainly consist of research-based literature, we decided to include theoretical literature as well, as it documents the development and principles of the open studio approach. Through this integrated review of quantitative and qualitative research and information found in both theoretical and empirical literature, we sought to gain a profound understanding of the phenomenon under examination.

The Present Study

The purpose of this study was to map out and examine the scope of the open studio approach to art therapy as reflected in professional, clinical and research literature. Variations on the model were also reviewed, as well as common characteristics and unique differences. The review also identifies trends and aspects that need further research. For the purpose of the study, a research question was formulated based on PCC (population, concept, content) key concepts (Tricco et al., 2018). These concepts were chosen because this research examined existing variations of the open studio approach as implemented among different populations and settings.

The present review related to the following questions:

1. Based on the literature, what do we know about the open studio approach to art therapy?

2. What kinds of publications/studies exist on the open studio approach to art therapy?

3. In what contexts and venues is this approach implemented and among what populations?

4. What are the common factors and the unique difference in the way the approach is implemented in all its variations?

5. Are there changes in the open studio approach over time, and how are they reflected in the writing on this subject?

Method

The purpose of the search process was to identify existing publications pertaining to the open studio approach to art therapy. The search was carried out in a systematic, replicable and comprehensive manner from May to September 2019, and the database search was conducted on May 31st. The search encompassed leading data bases: PUBMED; PsycINFO; Scopus; Cochrane; Cinahl; Eric; ProQuest Dissertations; World Cat; ULI; and Web of Science; as well as a manual search of art therapy journals in English such as The Arts in Psychotherapy Journal; Art Therapy Journal; International Art Therapy Journal; The Canadian Art Therapy Journal; Journal of Clinical Art Therapy; and journals in Israel such as Beyn Hamilim and The Academic Journal of Creative Arts Therapies. The search was carried out using three search parameters: title, abstract and key words. The search strategy included the following terms: “open studio” or “studio approach” or “community art studio” or “art hive” or “social action art studio” or “studio art therapy” or “therapeutic studio” or “community-based art studio.” In Hebrew, the keyword was “studio patuach” which is the Hebrew translation for “open studio.” In addition, a search for gray material was conducted (unpublished research or articles, lectures given at conferences, etc.) by reaching out to leading experts in the field and scanning websites of professional associations, conference proceedings, and reference lists of findings that came up in the systematic search. The search was conducted in English and Hebrew. Our decision was based on several considerations. First, our assumption was that most of the existing literature is in English. Secondly, the researchers' knowledge of these languages enabled a more efficient search and screening process. Thirdly, we assumed that most of the articles published in other languages include an abstract in English, and we would be able to translate them if, based on this abstract, they would potentially be included in the review.

The findings were screened by two researchers who applied the pre-determined inclusion criteria and worked independently of one another, using the “Covidence” software for systematic review management. The researchers resolved disagreements on publication selection by discussing the disagreements and reaching a consensus.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Based on the research strategy, quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method studies were included, as were action research, case studies, articles and chapters from books about the open studio approach to art therapy. According to the systematic scoping review method, published findings were included as well as unpublished full texts. Findings relating to a wide range of settings and populations were included (different age groups, normative as well as clinical populations, and populations from different cultures). In addition, as this is the first systematic scoping review of this field, the search was not restricted to specific years. Finally, as was explained in detail above, we included publications in any language that came up in the systematic search.

Exclusion criteria for this review were applied to findings that did not reference art therapy or the open studio approach. However, we did include findings relating to the studio approach though they referenced models that did not define themselves as art therapy per se because of political or ideological reasons; in essence, however, these models did adhere to the principles of the open studio approach to art therapy. These include, for example, disability studios (Lentz, 2008). Similarly, keeping with systematic scoping review protocol, studies and relevant articles that are currently being written, and no full text is yet available, were not included.

Data Charting

Extraction of relevant information was done in a systematic manner according to PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) (Tricco et al., 2018), and using a tool developed by the researchers based on the research questions. The data extraction process included classification of findings according to (a) type of publication (research, case studies, theoretical material); (b) research method (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, mixed method); (c) date of publication; (d) characteristics of population (age, type of pathology/normative); (e) setting (clinical, community, educational, therapist training); (f) intervention type (facilitators engaging in artmaking alongside participants or not; exhibition or no exhibition of art work; facilitators' perception of open studio participants as artist, participant or client; length and frequency of sessions; make up of group (regular participants or continuously changing group); (g) country; (h) results of studies.

Results

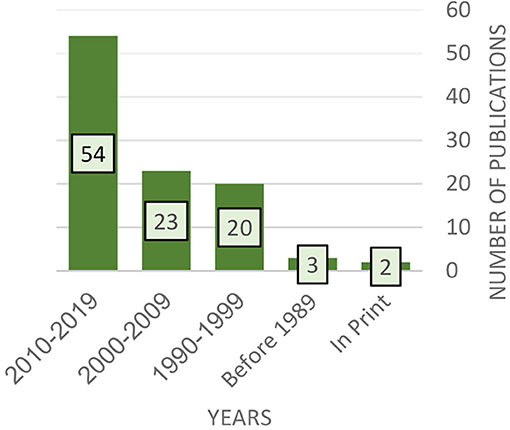

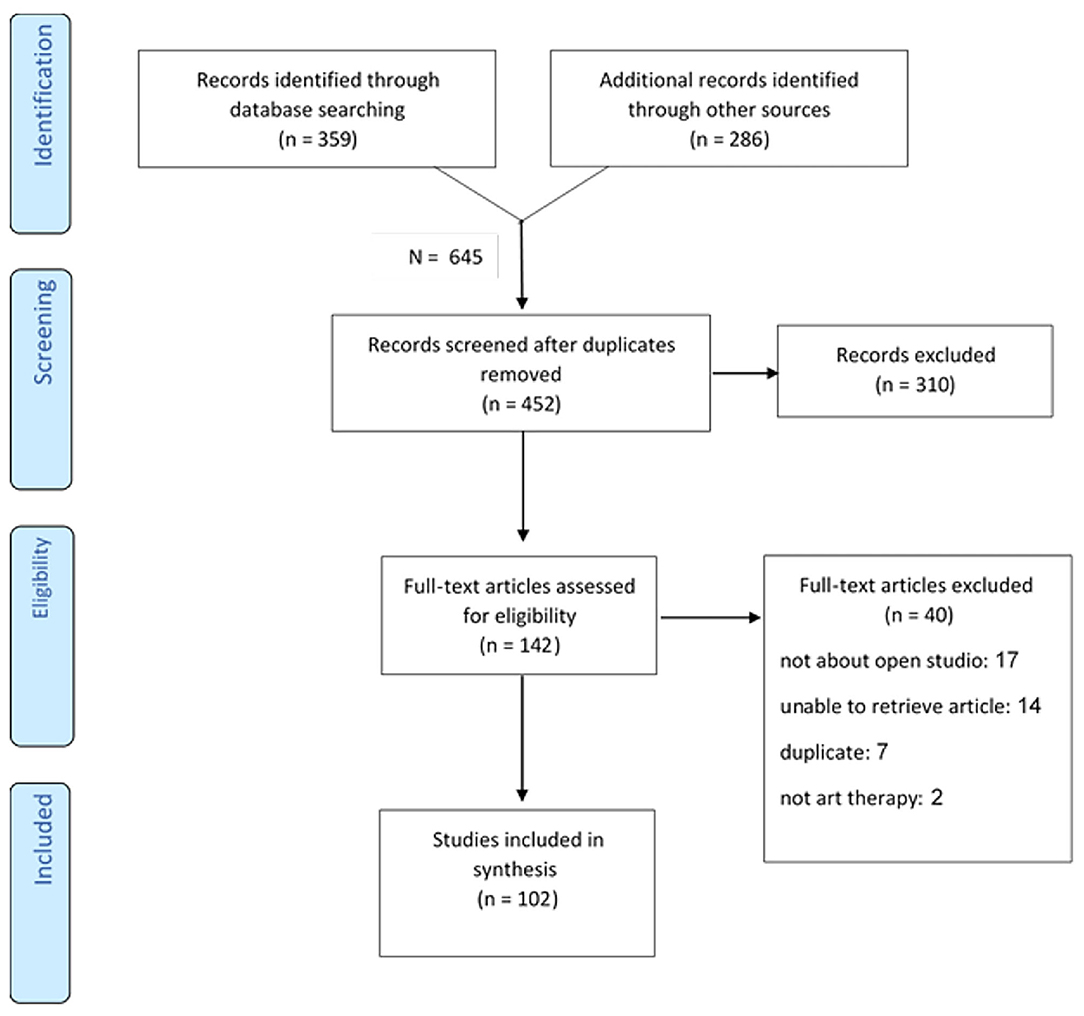

The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) presents the systematic search and screening process. Three hundred fifty-nine publications were found as a result of the systematic search of data bases, and 286 publications were found following a manual search of journals, a scan for gray literature on websites of professional associations in Israel and abroad, and a review of conference proceedings. Altogether, 645 publications were found. Out of these, 193 findings were duplicates, so 452 articles remained to be screened. The first screening, conducted by the two researchers independently of one another, was done according to title and abstract. At this point, 310 articles were discarded from the review following application of the protocol's inclusion criteria, and 142 publications remained. During the second screening stage, the inclusion criteria were applied to the full texts of the publications. Fourty publications were excluded for the following reasons: 17 did not pertain to the studio approach; the text of 14 findings was inaccessible; 7 were duplicates; 2 were not about art therapy. Fourteen publications (mainly theses) included in the first stage of the screening were not included in the review, because the full text was inaccessible. Several attempts were made to obtain these full texts, including requests submitted to the libraries of the relevant universities and colleges that were turned down. In addition, we attempted to obtain contact information for the authors. Finally, 102, i.e., 16% of the publications identified through the first systematic search were found suitable to be included in the review.

Figure 1. Systematic search according to the PRISMA statement methodology, extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018).

Publication Characteristics

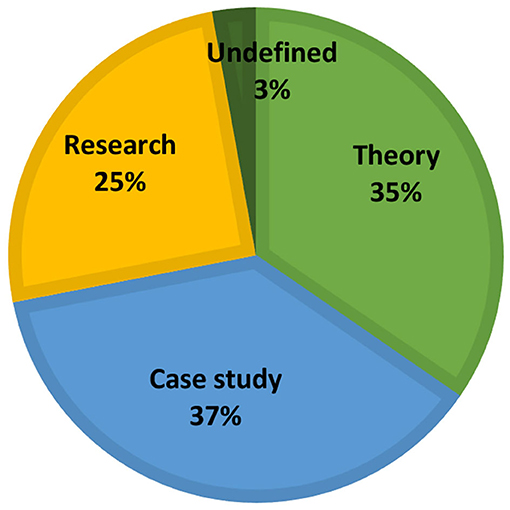

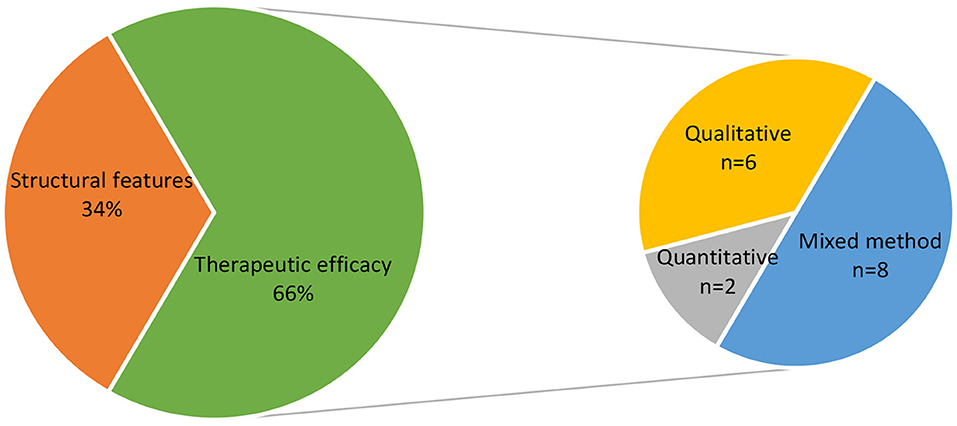

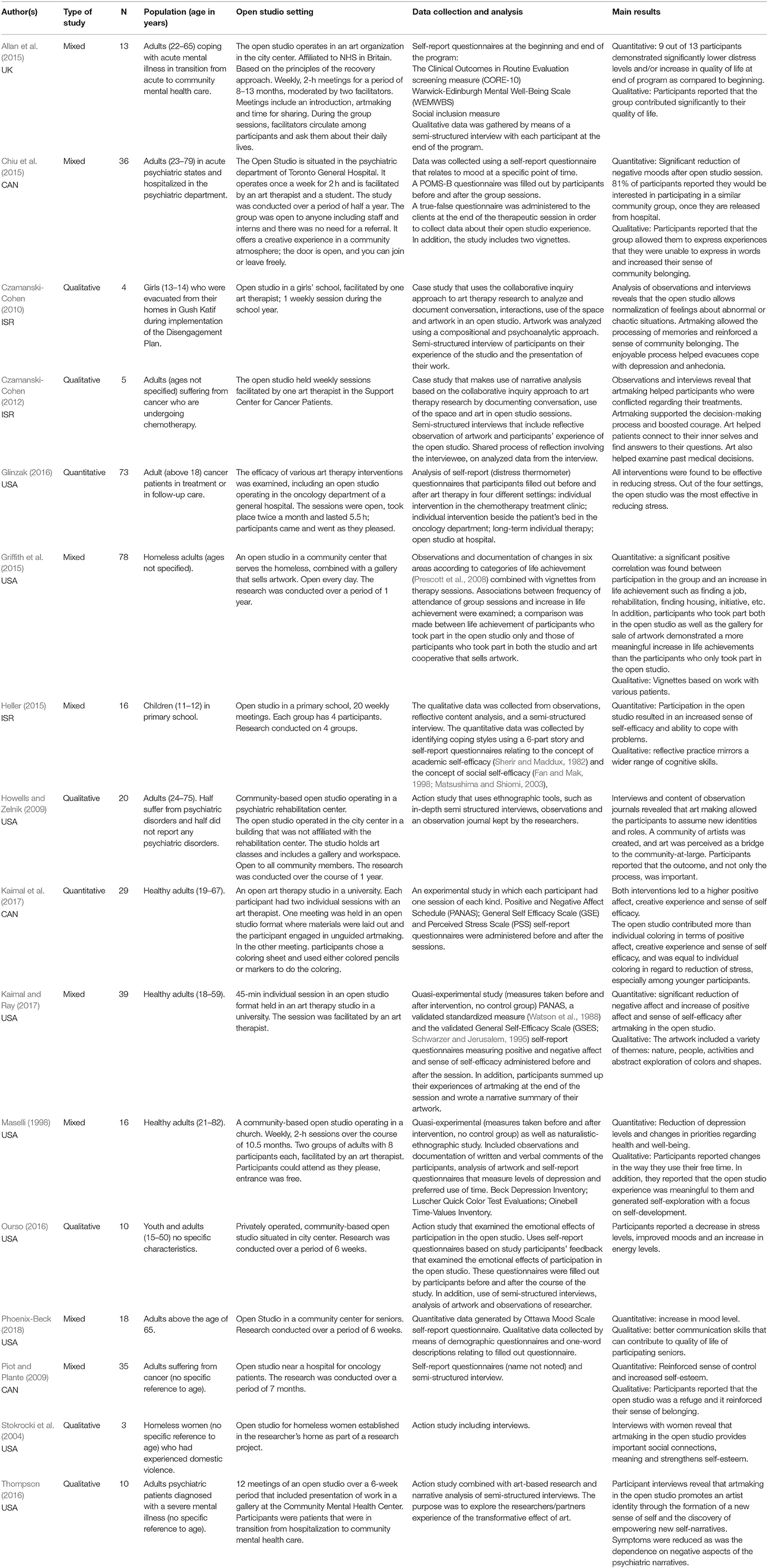

The 645 findings that resulted from the systematic search process include articles and studies from art therapy, art, art education, architecture, television, theater, music, computers and more. Out of these, 102 fit the inclusion criteria that define the studio approach to art therapy. Figure 2 shows the distribution of results according to publication type. Thirty seven% of the publications are case studies, 35% are articles on theoretical aspects of the studio approach, and 25% are studies. 3% of the publications do not belong to one of these categories and include book reviews or proposals for potential open studio programs. 66% of the studies conducted on the open studio approach deal with its therapeutic efficacy, and 34% deal with structural features, studio conditions and how the intervention takes place (Figure 3). Among the studies that examined therapeutic efficacy, most of the studies are mixed-method studies (n = 8), qualitative studies and action studies (n = 6), and a minority are quantitative studies (n = 2) (Figure 3). As shown in Table 1, these quantitative and mixed method studies were predominantly based on self-report questionnaires such as distress scales, mood questionnaires, questionnaires that measure sense of self-efficacy, and more. Three of the mixed method and quantitative studies were quasi-experimental, i.e., measurements were conducted before and after the intervention and there was no control group. The qualitative information in the mixed-method and qualitative studies was generated using semi-structured interviews and analysis based on a narrative approach; observations and transcriptions of sessions; documentation and analysis of artwork using art-based research methods; participants reflections on their creative work; and more.

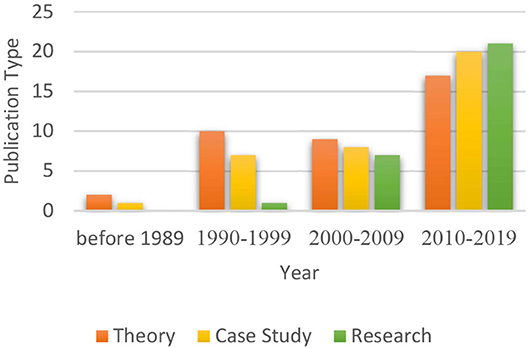

As Figure 4 reveals, most of the existing publications on the open studio approach are from the 1990's or later, and this volume of work has been growing steadily since. The number of publications, which has almost doubled in the last decade, can indicate the increasing popularity of this method. Initially, the literature was mainly theoretical in nature; in recent years, however, the number of research-based publications has grown steadily and even exceeds that of theory-based texts (see Figure 5). This could indicate that the open studio approach is increasingly accepted as part of art therapy practice and that there is growing academic interest in this model.

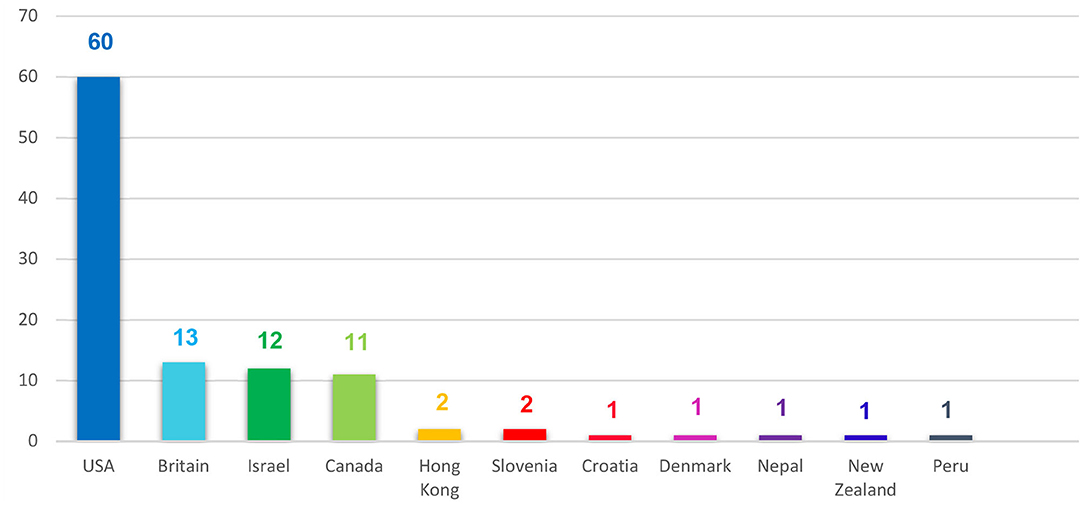

Regarding the geographical scope of the open studio approach to art therapy, the current research reveals that open studio models are mainly prevalent in North America and Europe (Figure 6). It is possible that our findings were influenced by the search languages (i.e., English and Hebrew); nevertheless, taking into account certain cultural and geo-political factors, they probably reflect the geographical prevalence of the open studio approach as well the global distribution of the art therapy profession and practice quite accurately.

Participant Characteristics

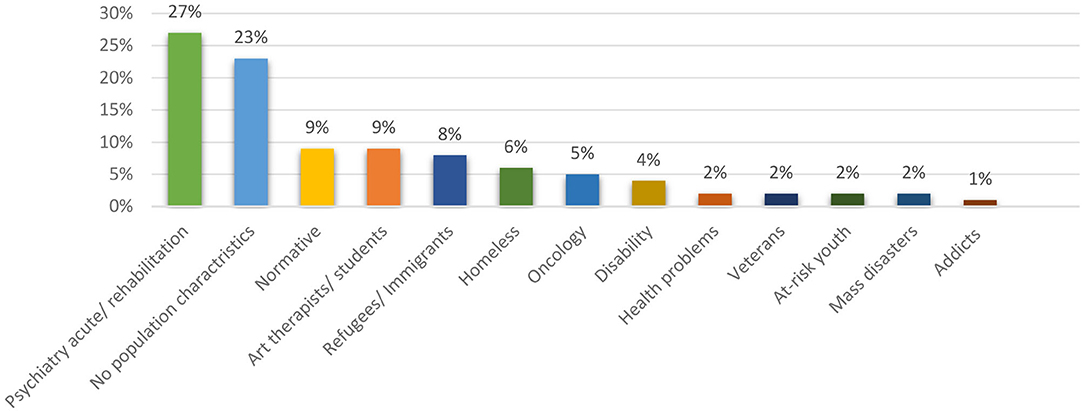

Figure 7, which presents the populations among which the open studio approach to art therapy is practiced, reveals that 61% of the findings relate to populations that are coping with challenges; in a significant number of cases, the open studio model is implemented among populations dealing with psychiatric problems (27%). The open studio was also implemented among the following populations: immigrants and refugees (8%); the homeless (6%); oncology patients (5%); people with disabilities (4%) people with various health problems (2%) victims of mass disasters (2%); army veterans (2%) youth at-risk (2%) and drug-addicts (1%). 18% of the findings relate to normative populations, including a specific focus on students of art therapy and art therapists. 21% of the findings do not specify type of population.

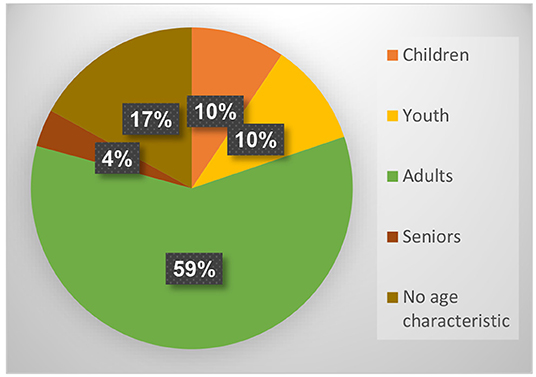

In addition, we found that most of the texts relating to the open studio approach to art therapy focused on adults (59%). We also found that 10% of the publications relate to youth, 10% relate to children, and 4% to seniors (Figure 8). 17% of the findings do not specify ages or cannot be classified according to specific age criteria.

Intervention Characteristics

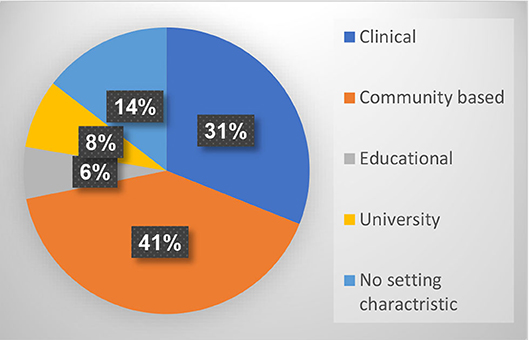

Figure 9, which presents the distribution of open studio settings, shows that most of the publications relate to community-based settings (41%), including art centers, churches, shelters for the homeless, rehabilitation centers for those suffering from mental health disorders, harm reduction centers, stores, galleries, museums, and more. 31% of the publications deal with an open studio in a medical setting, such as a psychiatric hospital, general hospital, clinic, and more. 8% focus on academic settings including use of the open studio model to train art therapists or to conduct academic research. 6% refer to educational settings, i.e., open studio programs in schools, and 14% of the publications do not refer to a specific setting.

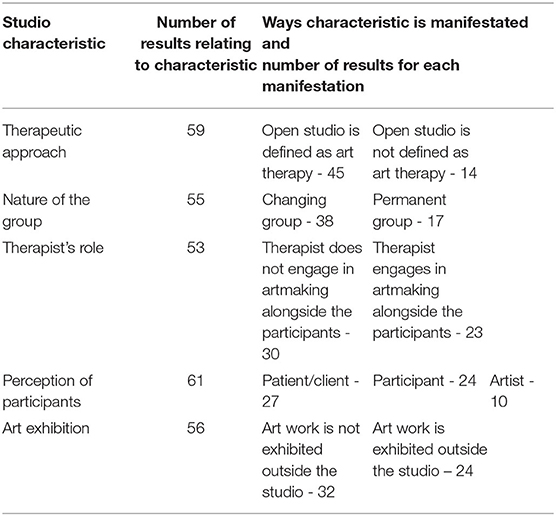

Two main themes emerge from the findings: (a) the primary therapeutic role of art; and (b) the flexibility of the open studio model, enabling it to serve the needs of a wide range of populations in many different settings. Among this variety of uses, there are differences not only in population and setting, but also in regard to therapists' viewpoints. Table 2 presents these main differences between the various models in relation to: (a) Group composition: most of the findings that refer to the composition of the open studio group describe a changing group of participants. Groups of this kind can be found in psychiatric departments (Gonzalez-Dolginko, 2016), in cancer treatment centers (Piot and Plante, 2009) and in community-based models, where the studio is permanent and the participants come and go, and stay as much as they wish (drop in studio). Some open studio models serve a regular group of participants, such as in schools (Czamanski-Cohen, 2010) or training programs for art therapists, which are implemented for a specific period of time (Wix, 1995); (b) The facilitator's role, which differs according to his or her therapeutic approach: most findings that reference this aspect describe a model in which the facilitator does not engage in artmaking; rather, these facilitators concentrate on holding the space, witnessing or helping participants (Deco, 1998). The facilitators support the creative process (Braun, 1997) and allow for the birth of the artwork (Shapiro, 2014). One approach even suggests that the moderator should assume the role of the participant-artist's apprentice (Atkinson and D'Innocenzo, 2014); this idea stems from the belief that the artist knows best when it comes to his or her life and art. There are open studio approaches where the moderator works alongside participants as a partner (Marshall-Tierney, 2014) and models the creative process. In these cases, the status of moderator is equal to that of participant (Allen, 1995). These studios symbolize a shift from the hierarchy of therapist and patient to a more intersubjective approach based on equality (Allen, 1993). Another aspect of facilitation in the open studio is that often there is a group of facilitators holding the space. This strengthens the communality of this model, moreover it enables the facilitators to alternate different facilitation roles and participants to develop a relationship with the studio as a holistic entity that includes all that is in its space (Shapiro, 2014); (c) Facilitators' perception of participants: most of the findings that relate to the way open studio participants are perceived see participants primarily as “clients” or “patients” (e.g., Deco, 1998). This attitude prevails in clinical or community-based settings in which participants cope with mental health challenges. Other models of community- based settings stress aspects of individual welfare and social services and refer to participants as “participants.” The intention is that participants take part in the studio and engage in the creative process without being committed to an aesthetic outcome; the emphasis is on participation in the creative process and not the final product (e.g., Block et al., 2005). The perception of the participant as “artist” is characteristic of a minority of open studio models (e.g., Lentz, 2008) that emphasize aspects of health and normalization; this perception is more common among community-based models; (d) Exhibiting artwork: in most descriptions of the open studio, artwork is hung or exhibited in the studio space, but not outside the studio. In addition to the ethical need to maintain confidentiality, this convention stems from emphasis on the creative process that is characteristic of the therapeutic approach. Exhibition of the artwork may shift the focus to the quality and aesthetics of the outcome and undermine the authenticity and spontaneity of the creative process. In some models, exhibitions are organized for people outside the studio (Thompson, 2009), and some models encourage sale of the participants' artwork as part of the therapeutic process (Griffith et al., 2015). Exhibition and recognition of the artwork gives the artist a presence and voice within the social space and this is empowering and therapeutic in itself; (e) Length: the length of the studio session is geared to allow an in-depth process; most of the publications that refer to the length of the sessions describe sessions that range from 1.5 to 2 h (61%) or beyond that, 3–6 h (31%). Most models of open studios operate regularly in institutions or communities; however, some models are implemented for a limited time as a response to specific situations that demand therapeutic solutions, such as natural disasters (Linton, 2017). These circumstances sometimes dictate the need for a temporary, portable studio (Kalmanowitz and Lloyd, 2011). The internal structure that art therapists carry with them makes it possible for them to set up a portable studio in a wide variety of settings. This internal structure includes sensitivity and awareness of the power of artmaking and imagery, its ability to represent human experience, and the belief in human strength and resources. The patient is not perceived as helpless and the therapist is not seen as the one who has all the answers. Moreover, imagery is interpreted in more than one way to allow the therapeutic process to reach its full potential. Moreover, this vision enables an atmosphere that encourages expression, engagement in the creative process and a tapping of individual resources (Kalmanowitz and Lloyd, 2011); (f) Theoretical foundation: Ideological and political considerations stemming from professional perceptions of pathology and health determine whether a certain model classifies itself as art therapy, or not. Questions then arise as to what makes the open studio a model for art therapy and how does open studio practice position itself within the defined boundaries of the profession (e.g., Kapitan, 2008). A study of community studio art programs designed to empower people with disabilities and support their integration into society (Vick and Sexton-Radek, 2008) revealed that studios in the US define themselves differently than their European counterparts. European programs do not define themselves as art therapy; moreover, they emphasize the artistic talent of participants as well as the outcome. The US studios, in comparison, influenced by traditional art therapy principles, value process much more than the artistic talents of the participants reflected in the outcome. Facilitators in American settings tend to work on artistic projects alongside the participants, as partners and to enable modeling; in European programs, in comparison, moderators offer participants aesthetic and technical feedback on their work. Furthermore, studios for participants with disabilities are based on the assumption that people who are dealing with an ongoing situation in life are not sick; efforts made to destigmatize disability through activities that have social value and help reduce the experience of “otherness” (Vick and Sexton-Radek, 2008) reflect this attitude. The European programs tend to describe themselves as “not art therapy” due to what seems to be a narrow and outdated belief that the role of art therapy is to interpret the patient's artwork in order to find psychological or pathological meaning (Vick and Sexton-Radek, 2008).

Vick and Sexton-Radek (2008) assert that art therapy has moved away from a narrow medicine-based approach and taken of new professional, social and rehabilitative dimensions. This necessitates a redefinition of the therapeutic boundaries of art therapy.

Discussion

Results show that most of the literature about the open studio is from the 1990's or later. This supports Wix's (2010) claim that studio practice has been overlooked in the documentation of art therapy history even though it has had a key role in the development of this field. Wix (2010) asserts that art therapy's bias toward its psychological rather than its artistic roots created lacunas in both theory and practice. She argues that bringing the studio history of art therapy to light will ground the profession in its artistic roots (Wix, 2010). The many and varied descriptions of the open studio approach in the literature enable identification of common core principles that are not dependent on setting or type of population. The open studio approach is grounded in the central role of art and an open and non-moderated creative process. The facilitator is responsible for holding the space in order to allow for individual expression in a group setting. The length of the session enables engagement in the creative process; it is also important that the studio is a liminal space (Timm-Bottos, 2016) and has a special atmosphere. These “art as therapy” approach-based principles define the appropriate physical place, therapeutic and artistic space, and session length that allow full engagement in the creative process.

Beyond its common core principles, the open studio is a flexible therapeutic model that can be implemented among different populations and in different settings. The literature shows there are different names for interventions that have the same principles, and this variety of names also reflects the shift in focus from one model to another, for example, open studio group (Deco, 1998), open studio process (Allen, 1995), community-based art studio (Vick and Sexton-Radek, 2008), therapeutic studio (Kapitan, 2008), art hive (Timm-Bottos, 2016), disability studio (Lentz, 2008), inhabited studio (Kalmanowitz, 2016), and portable studio (Kalmanowitz and Lloyd, 2011).

The following two examples serve to illustrate the diverse range of open studio components, which are presented in detail in the chapter on results. This variety of practices corroborates Shapiro's (2014) claim that the open studio is a dynamic entity and its unique character is shaped by the participants' specific needs, the features of each specific setting and the facilitators' worldview. The OSP (open studio process), for example, emphasizes the spiritual aspect of the studio by combining art and writing. In addition to the creative process, it utilizes two central elements, intention and witnessing, as fundamental mindfulness tools (Allen, 2016). Another example is the studio-based practice implemented by an artist collective that combines art and music in Kerrville State Hospital. It includes exhibition of the participants' work across a wide range of platforms, including art exhibitions, cultural events, quarterly art magazines, fashion shows, performance opportunities, and more. Through these displays of artistic creativity, individuals are recognized for their contribution to society, and this reduces stigma both inside and outside the walls of this psychiatric institution (Peterson and Etter, 2017).

From a theoretical perspective, the open studio incorporates Winnicot's (1958) concept of “the capacity to be alone in the presence of another,” which, in his view, is one of the most important indications of emotional maturity. Winnicott suggests that the capacity to be alone develops in the presence of a reliable mother. The constant and dependable studio environment, including physical organization of the space and the presence of the group and facilitators, creates trust and makes it possible for the participants to “be alone” and engage in an internal dialogue through the process of artmaking (Deco, 1998).

Allen (2016) explores spiritual aspects of the open studio, and describes an energy or life force that is manifested through the creative process and images that emerge when one engages in artwork alongside another person, an action which involves taking risk and being open to the unknown. Each participant has something unique to bring to life and to share with others (Allen, 2016). McNiff (1995) addresses the “transformative spirits” that are embodied in the images created in the studio. He stresses the importance of the group, as it is inherently more intelligent, creative and resourceful than any individual; moreover, it represents the empowering support of a community that is shaped by a multiplicity of participants and images. McNiff (1995) perceives the studio as a vessel of creative transformation in which the creative process heals and transforms life.

Wix (2010) relates to the studio as a location that enables integration: “These locations of fruitful interdependency invite the reason of the heart to integrate with the reason of the mind and to foster engagements with self, materials, and others” (p. 182). Shapiro (2014) suggests that transference occurs in the art studio setting; the object of this transference is the studio space itself, which can perhaps be seen as fulfilling a co-therapist role. Participants often attribute magical qualities to this therapeutic space because it enables the expression of their inner and imaginary worlds. Honig et al. (2019), who study the role of studio practice in an art therapy training program, propose expanding the therapist-client-art triad, which offers a foundation for understanding the potential space of art therapy, to a pentagonal model consisting of therapist, client, art, space and group. This expanded model can provide a deeper understanding of the potential space of the art studio and enable exploration of the relations between therapeutic dimensions. Space and group, in addition to the participant, art and facilitator, are central dimensions in the open studio approach and they expand our understanding of the contexts in which therapeutic and artistic processes take place.

Moreover, it seems that the studio approach to art therapy mirrors the expansion of art therapy to social and community spaces (Kapitan, 2008). Timm-Bottos (2016) asserts that art hives, which are based on the community art studio, purposely blur the distinctions between art therapy, art education, critical cultural studies, popular pedagogy, public science, and creative arts, and create a liminal place between home and institution that allows for healing, reparation and innovation. Crane and Byrne (2020) relate to the open studio as a third space in art therapy education, in which the students explore their own capabilities and limitations through practice with art materials, as they undergo a creative process in the presence of others. This enables them to discover inner wisdom and embodied knowledge that is grounded in practice. The open studio is offered as a liminal space between academic classes and the experience of clinical practice, in which students are free to take risks and make the connections in order to experience and witness transformation as it happens (Crane and Byrne, 2020).

Limitations

This systematic scoping review has several limitations. First, because the search was done primarily in English and Hebrew, we may not have identified publications in other languages. However, as the term “open studio” is used in many disciplines, expanding the search terms to other languages would have created volumes of irrelevant data. In addition to English-language publications, the search identified nine publications in Hebrew, two publications in French and one in Spanish. If the search strategy had included the term “open studio” in other languages, additional publications may have come up in the search. In other words, we can assume that our findings do not represent all publications on the subject of the open studio approach to art therapy.

Another limitation relates to literature published before the digital era. It may be that articles published before the 1980's are not accessible through the systematic scoping of data bases, and earlier publications on the open studio approach may be missing from this present review. Nevertheless, it may also be that the studio approach to art therapy is less present in literature published before the 1980's due to trends in the development of the art therapy field (Malchiodi, 1995; Wix, 2010).

In addition, though this review includes chapters from books that are important to the thinking and practice of the studio approach, there is a possibility that not all book chapters were found and included in this review. Notably, publications of this kind are usually not included in systematic scoping reviews because they are difficult to locate.

Finally, as explained above, 14 relevant and yet unpublished findings were not included because we were unable to obtain them.

Conclusions

This review reveals an increase in publications relating to the open studio over time, the prevalence of this approach, and the increasing implementation of its various models among diverse populations in many contexts. Several common principles guide the practice of this approach. They are (a) the central role of art and artmaking in the healing process; (b) the studio as an enabling space; (c) the importance of individual expression within the group or community space; and (d) the role of the facilitator as enabling and encouraging creative processes. Studies on the therapeutic efficacy of the open studio approach reveal that open studios make a positive contribution to the lives of participants (Table 1). As this is the first systematic scoping review of this field, we sought to map out existing literature and outline the main characteristics of the open studio approach. There is room for further expansion of this review to include additional languages.

Findings revealed that most of the research is based on qualitative or mixed method studies. A review of the limitations referenced in these studies reveals that generalizations are difficult to make because of small sample sizes and short time periods; no comparative studies were conducted between intervention and control groups. There is a need for additional research involving larger samples and a longer time frame, and for comparative studies of intervention and control groups. At a time when there is a preference for evidence-based therapeutic interventions, and despite the need for rigorous quantitative studies that can support assumptions that the open studio is an effective therapeutic intervention, there is a lack of meticulous, empirical research.

In-depth studies that examine open studio participants' processes and experiences, as well as the studio's components and how they contribute to the therapeutic process, can shed more light on how the open studio serves as a therapeutic intervention in art therapy. In addition, findings show that there are very few publications and studies on how the open studio serves children, youth and seniors. There is room for more research on the use of this approach among these populations. A final topic for research is the way in which the open studio influences the community in community-based settings, and whether encounters between members of the community within the open studio have an impact on the community outside the studio.

In summary, the strength of the open studio model is its inherent flexibility, which enables implementation in many different contexts among diverse populations. In addition, this model encourages individual development within a group or community. It may be that these features, the expansion of art therapy to social and community spaces and the central role of art in the therapeutic approach contribute to the increasing prevalence of this approach. Furthermore, the open studio approach may be an appropriate response to the new social challenges that have emerged in recent decades, such as refugee crises or natural disasters.

The open studio approach represents a return to the roots of the art therapy profession where art serves as a foundation for healing and psychological transformation, as well as a move beyond the walls of the psychiatric hospital, to social and community environments. As Kapitan claims, “The “studio” in the largest sense is perhaps an archetype or deep structure wanting to be made visible and re-connecting art therapists to the places and communities they wish to belong in some fundamental way” (Kapitan, 2003, p. 14). This return to the core principles of the art therapy profession counteracts the trend of “clinification” (Allen, 1992) that perhaps represented a desire to be affiliated with psychotherapy and the mental health professions. It may signify that the field of art therapy is undergoing a significant differentiation and individuation process. In addition, it may reveal the impact of recent community mental healthcare approaches, such as the salutogenic or healing and resilience models. These models resonate with the open studio approach that emphasizes the health, strength, creativity and empowerment of the participant-artist.

Author Contributions

DF researcher and author. MB was the supervisor for this research and one of the reviewers in the process of the scoping review screening. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep appreciation to Janice Shapiro, who developed the open studio approach to art therapy in Israel. For three decades, her unique model was implemented among adolescents at the Eitanim psychiatric hospital. An art therapist, supervisor and lecturer, Janice has trained generations of Israeli art therapists in the spirit of this approach; her valuable contribution laid the foundations for the continuing evolution of the open studio approach in Israel.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568042/full#supplementary-material

References

Allan, J., Barford, H., Horwood, F., Stevens, J., and Tanti, G. (2015). ATIC: developing a recovery-based art therapy practice. Int. J. Art Ther. 20:14. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2014.968597

Allen, P. B. (1992). Artist in residence: an alternative to “clinification” for art therapists. Art Ther. 9, 22–29. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1992.10758933

Allen, P. B. (1995). Coyote comes in from the cold: the evolution of the open studio concept. Art Ther. 12, 161–166. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1995.10759153

Allen, P. B. (2016). “Art making as spiritual path: the open studio process as a way to practice art therapy”, in Approaches to Art Therapy: Theory and Technique (3rd ed.), ed J.A. Rubin (London: Routledge), 271–285.

Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychos. Rehab. J. 16, 11–23. doi: 10.1037/h0095655

Atkinson, E., and D'Innocenzo, L. M. (2014). Integration Art: A New Approach to Art Therapy. (Master's thesis). [Chicago (IL)]: The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Block, D., Harris, T., and Laing, S. (2005). Open studio process as a model of social action: a program for at-risk youth. Art Ther. 22, 32–38. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2005.10129459

Braun, L. N. (1997). In from the cold: art therapy with homeless men. Art Ther. 14, 118–122. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1987.10759266

Chiu, G., Hancock, J., and Waddell, A. (2015). Expressive arts therapy group helps improve mood state in an acute care psychiatric setting. Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 28, 34–42. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2015.1100577

Crane, T., and Byrne, L. (2020). Risk, rupture and change: Exploring the liminal space of the Open Studio in art therapy education. Arts Psychother. 69:101666. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2020.101666

Czamanski-Cohen, J. (2010). “Oh! Now I remember”: the use of a studio approach to art therapy with internally displaced people. Arts Psychother. 37, 407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2010.09.003

Czamanski-Cohen, J. (2012). The use of art in the medical decision-making process of oncology patients. Art Ther. 29, 60–67. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2012.680049

Deco, S. (1998). “Return to the open studio group: Art therapy groups in acute psychiatry,” in: Art Psychotherapy Groups, eds S. Skaife, and V. Huet (London: Routledge), 100–107.

Fan, C., and Mak, A. S. (1998). Measuring social self-efficacy in a culturally diverse student opulation. Soc. Behav. Pers. 26, 131–144.

Finn, C. A. (2003). Helping students cope with loss: incorporating art into group counseling. J. Special. Group Work. 28, 155–165. doi: 10.1080/714860157

Glinzak, L. (2016). Effects of art therapy on distress levels of adults with cancer: a proxy pretest study. Art Ther. 33, 27–34. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2016.1127687

Gonzalez-Dolginko, B. (2016). Assigning meaning to art to optimize the patient experience in short-term psychiatry (L'attribution de sens à l'art pour optimiser l'expérience des patients en psychiatrie à court terme). Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 29:57. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2016.1233376

Griffith, F. J., Seymour, L., and Goldberg, M. (2015). Reframing art therapy to meet psychosocial and financial needs in homelessness. Arts Psychother. 46, 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2015.09.007

Heller, A. (2015). The Contribution of “Open Studio” Program based Experiential -Learning to Developing Reflection Abilities and Self Efficacy of Elementary-School Children. (dissertation). [Cluj-Napoca (RO)]: Babes-Bolyai University.

Henley, D. (1995). A consideration of the studio as therapeutic intervention. Art Ther. 12, 188–190. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1995.10759158

Honig, O., Rinat, S., and Feldman, A. (2019). Studio Art Therapy as a Utopic Space (Structured or Open), a Space for Art Therapy Training and Analytic Group Art Therapy. Beit Berl College: Faculty of Arts – Hamidrasha.

Howells, V., and Zelnik, T. (2009). Making art: a qualitative study of personal and group transformation in a community arts studio. Psychiatr. Rehab. J. 32, 215–222. doi: 10.2975/32.3.2009.215.222

Kaimal, G., Mensinger, J. L., Drass, J. M., and Dieterich-Hartwell, R. M. (2017). Art therapist-facilitated open studio versus coloring: differences in outcomes of affect, stress, creative agency, and self-efficacy (Studio ouvert animé par un art-thérapeute versus coloriage : différences de résultats sur l'affect, le stress, l'agentivi). Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 30, 56–68. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2017.1375827

Kaimal, G., and Ray, K. D. (2017). Free art-making in an art therapy open studio: changes in affect and self- efficacy. Arts Health. 9, 154–166. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2016.1217248

Kalmanowitz, D. (2016). Inhabited studio: Art therapy and mindfulness, resilience, adversity and refugees. Int. J. Art Ther. 21, 75–84. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2016.1170053

Kalmanowitz, D., and Lloyd, B. (2011). “Inside- out Outside- in: Found Objects and Portable Studio,” in Art in Action: Expressive Arts Therapy and Social Change, eds E. G. Levine and S. K. Levine (London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers), 104–127.

Kapitan, L. (2003). Re-enchanting Art Therapy: Transformational Practices for Restoring Creative Vitality. Springfield: Charles C Thomas.

Kapitan, L. (2008). “Not Art Therapy”: revisiting the therapeutic studio in the narrative of the profession. Art Ther. 25, 2–3. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2008.10129349

Klorer, P. G. (2005). Expressive therapy with severely maltreated children: neuroscience contributions. Art Ther. 22, 213–220. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2005.10129523

Lentz, R. (2008). What we talk about when we talk about art therapy: an outsider's guide to identity crisis. Art Ther. 25, 13–14. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2008.10129355

Linton, J. (2017). A natural response to a natural disaster: the art of crisis in nepal (Une réponse naturelle à une catastrophe naturelle : art de crise au Népal). Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 30:31. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2017.1317201

Malchiodi, C. A. (1995). Studio approaches to art therapy. Art Ther. 12, 154–156. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1995.10759151

Marshall-Tierney, A. (2014). Making art with and without patients in acute settings. Int. J. Art Ther. 19, 96–106. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2014.913256

Maselli, R. L. (1998). An open studio pilot program: Art therapy in a health and wellness outreach ministry. (Master's thesis). [Pepper Pike (OH)]: Ursuline College.

Matsushima, R., and Shiomi, K. (2003). Social self-efficacy and interpersonal stress in adolescence. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 31, 323–332.

Moon, C. H. (2016). “Open studio approach to art therapy”, in The Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy, eds. D. E. Gussak and M. L. Rosal (Oxford; Malden: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.), 112–121. doi: 10.1002/9781118306543.ch11

Ourso, L. K. (2016). Open Studio Art Therapy: A Participatory Study. (Master's thesis). [Saint Mary of the Woods (IN)]: Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College.

Peters, M., Godfrey, C., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., and Baldini Soares, C. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthcare 13, 141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

Peterson, J., and Etter, A. (2017). Creating community and shattering stigma: collaborative arts interventions for the forensic population (Création de communauté et réduction de la stigmatisation : interventions artistiques collaboratives avec des personnes bénéficiant de services de psych. Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 30:78. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2017.1381511

Phoenix-Beck, H. (2018). Painting a Positive Mood: Open Studio Art With Older Adults. (Master's thesis). [Belmont (CA)]: Notre Dame de Namur University.

Piot, V., and Plante, P. (2009). L'approach studio libre en oncologie: description de l'atelier d'art-therapie offert par maurice brault à la fondation québécoise du cancer (The open studio approach in oncology: A description of the art therapy workshop offered by Maurice Brault). Revue Québécoise Psychol. 30, 99–119.

Prescott, M. V., Sekendur, B., Bailey, B., and Hoshino, J. (2008). Art making as a component and facilitator of resiliency with homeless youth. Art Ther. J. Am. Art Ther. Assoc., 25, 156–163. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2008.10129549

Sapouna, L., and Pamer, E. (2014). The transformative potential of the arts in mental health recovery – an irish research project. Arts Health. 8, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2014.957329

Schwarzer, R., and Jerusalem, M. (1995). “Generalized self-efficacy scale,” in Measures in Health Psychology: A User's Portfolio, Causal and Control Beliefs, eds J. Weinman, S. Wright and M. Johnston (Windsor: Nfer-Nelson), 35–37.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York, NY: Free Press.

Shapiro, J. (2014). “Open studio: model for art therapy based on spontaneous creation process from an open, non-directing therapeutic approach,” in Creation – The Heart of Therapy. ed Berger, R. (Kiryat Bialik: Ach Publications), 135–158.

Sherir, M., and Maddux, J. (1982). The self-efficacy scale: construction and validation. Psychol. Rep. 52, 663–671.

Stokrocki, M., Andrews, S. S., and Saemundsdottir, S. (2004). The role of art for homeless women and survivors of domestic violence. Visual Arts Res. 29, 73–82.

Thompson, G. (2009). Artistic sensibility in the studio and gallery model: revisiting process and product. Art Ther. 26, 159–166. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2009.10129609

Thompson, G. (2016). Aesthetic Action and Self-Construction of an Artist Identity: The Impact of Art and Art Therapy on Subjectivity and Mental Illness in Qualitative Research. (dissertation). [New York (NY)]: Saybrook University.

Timm-Bottos, J. (2016). Beyond counseling and psychotherapy, there is a field, i'll meet you there. Art Ther. 33, 160–162. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2016.1199248

Timm-Bottos, J., and Reilly, R. C. (2015). “Neighborhood art hives: engaging communities in teaching and learning”, in The SAGE Sourcebook of Service-Learning and Civic Engagement, eds. O. Delano- Oriaran, M. W. Penick- Parks and S. Fondrie (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications) 179–184. doi: 10.4135/9781483346625.n34

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

Tyson, E. H., and Baffour, T. (2004). Arts-based strengths: A solution-focused intervention with adolescents in an acute-care psychiatric setting. Arts Psychother. 31, 213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2004.06.004

Vick, R. M., and Sexton-Radek, K. (2008). community-based art studios in europe and the united states: a comparative study. Art Ther. 25, 4–10. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2008.10129353

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070.

Winnicot, D. W. (1958). “The capacity to be alone,” in Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment, eds M. Masud and R. Khan (London: Hogarth).

Wix, L. (1995). The intern studio: a pilot study. Art Ther. 12, 175–178. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1995.10759155

Wix, L. (2000). Looking for what's lost: the artistic roots of art therapy: mary huntoon. Art Ther. 17, 168–176. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2000.10129699

Keywords: open studio, art therapy, scoping review, art-based, community-based

Citation: Finkel D and Bat Or M (2020) The Open Studio Approach to Art Therapy: A Systematic Scoping Review. Front. Psychol. 11:568042. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568042

Received: 02 June 2020; Accepted: 15 September 2020;

Published: 20 October 2020.

Edited by:

Jennifer Drake, Brooklyn College (CUNY), United StatesReviewed by:

Christopher Bull, Lancaster University, United KingdomGioia Chilton, George Washington University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Finkel and Bat Or. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela Finkel, ZGFuaWVsYWZpbmtlbEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Daniela Finkel

Daniela Finkel Michal Bat Or

Michal Bat Or