- 1School of Politics and Law, Shaoyang University, Shaoyang, China

- 2School of Psychology, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China

- 3Department of Education, Luliang University, Luliang, China

- 4Department of Medical Psychology, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

Extensive psychological interventions primarily target the negative symptoms of depression and the deficits in positive resources have been systematically neglected. So far, little attention has been devoted to psychological capital (PsyCap) intervention from the perspective of developing positive resources. The aim of the present pilot study was to evaluate the efficacy of psychological capital intervention (PCI) for depression in a randomized controlled trial. A total of 56 patients were randomized to either care as usual (CAU) for normal medication or psychological capital intervention (PCI) group, where the normal medication was supplemented with the PCI. Participants were assessed at pre- and post-treatment, as well as 6-month follow-up, on measures of depressive symptoms and PsyCap. The PCI group displayed significantly larger improvements in PsyCap and larger reductions in depression symptoms from pre- to post treatment compared to control group. Improvements were sustained over the 6-month follow-up period. Targeting the positive resources intervention in the PCI may be effective against the treatment of depression.

Introduction

Depression is a highly prevalent mental disorder with lifetime prevalence rates for depression at over 16% (Kessler, 2003). It is recurrent, debilitating and even lethal. The onset of depression is accompanied by a host of undesirable health, social consequences, it also creates a substantial financial burden (Dunlop et al., 2005; Lopez and Mathers, 2006; Kessler, 2012; Papakostas and Ionescu, 2014). Given these ramifications, it is critical to concentrate on intervention efforts.

Currently, depression intervention to date has focused largely on fixing negative or pathological feelings, thoughts and behaviors (Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009). Previous studies have examined the efficacy of psychological treatments for depression including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy and problem solving therapy (Hollon and Ponniah, 2010; Cuijpers et al., 2011; Barth et al., 2016). There are no major differences in efficacy between these psychotherapies and all demonstrated their efficacy (Cuijpers et al., 2008).

However, for some depressed individuals, therapies that mainly focused on negative emotions and cognitive biases may be counterproductive to their recovery and may disrupt the therapeutic alliance (Burns and Nolen-Hoeksema, 1992; Castonguay et al., 2004). Thus, some researches elucidated that positive psychology interventions, which aims to cultivate positive resources (i.e., positive feelings, behaviors and cognitions) may serve as an important yet underexplored intervention approach in facilitating recovery from depression (Fredrickson, 2013; Layous et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2017).

Evidence across multiple units of analysis reveals that depression is associated with absence of positive resources (Hofmann et al., 2012). Additionally, there is robust evidence that decreased positive resources are implicated in apathy, inattentiveness, lack of interest and lack of self-confidence and sadness, which are pivotal characteristics of depression (Watson et al., 1988; Clark and Watson, 1991). Recent studies have noted that positive resources can reduce the depressive symptoms and might play a protective role in the development of depression (Bos et al., 2013; Lindahl and Archer, 2013; Raes et al., 2014; Boumparis et al., 2016). The unique link between positive resources and depression suggests that intervention targeting the positive resources may fill a particularly important gap left by extant treatment. A typical example for positive resources is psychological capital. Psychological capital (PsyCap), describes an individual’s psychological capacity that can be developed, and managed for performance improvement (Luthans, 2002). Psychological capital is composed of: (1) hope: persevering toward goals and when necessary, redirecting paths to goals in order to succeed; (2) self-efficacy: having confidence to succeed a challenging tasks; (3) optimism: making a positive attribution regarding succeeding now and in the future; (4) resiliency: when beset by problems and adversity, sustaining and bouncing back and even beyond to attain success (Luthans and Youssef, 2004; Luthans et al., 2007a). Recent research demonstrated that PsyCap was significantly related to symptoms of depression (Bakker et al., 2017). In addition, evidences indicated that PsyCap can significantly moderated the associations of depression and stress, could be a positive resource for combating depression (Liu et al., 2012; Shen et al., 2014).

The PsyCap intervention (PCI) is a highly focused training session which draws from past research in terms of hope, self-efficacy, optimism and resilience (Luthans et al., 2007b). According to the resource activation theory, PCI concentrating on positive aspects of the person (i.e., resource priming), can promote positive perception, behavioral and emotion, which in turn enhance resource realization and lead to a positive mood (Grawe and Grawe-Gerber, 1999; Flückiger and Wüsten, 2009). There is accumulating evidence that PCI can drastically increase the individual’s level of PsyCap, well-being and organizational behaviors (Luthans et al., 2010; Avey et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2014; Nolzen, 2018). However, to our best of knowledge, no studies have examined the effect of PCI in the treatment of depression.

The central aim of the current pilot study was to test the efficacy of PCI in a sample of depressed individuals. We hypothesized that participants assigned the PCI group would report greater reductions of depression symptoms and greater improvements on the level of psychological capital at post-intervention than the control group that only received the usual care. To our knowledge, no studies have examined PCI in depression treatment-seeking samples. That was the central goal of the current research.

Materials and Methods

Participants

A total of 56 outpatients seeking treatment for depression were recruited from the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, the Third hospital of Shanxi Medical University and Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences. Patients were eligible for the study if they present with clinically elevated symptoms of depression during the previous 2-week period and were aged between 18 and 65 years. To ensure that participants could complete the program safely and to apprehend of our findings, participants with (1) concurrent psychotherapy for depression during past 4 weeks; (2) a history of head injury, stroke, seizure, other central nervous system disease; (3) substance abuse; (4) a lifetime diagnosis of anxiety, bipolar disorder type I or II, schizophrenia; (5) strong suicidal ideation were excluded.

Diagnostic assessment was based on a structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV criteria by the experienced clinical experts. Participants enrollment statistics and progress through the study are presented in Supplementary Figure S1. Of the 56 participants who were randomized to the PCI (n = 31) or control group (n = 25), two participants in the PCI discontinued treatment due to inconvenient to hospital following session 3. Thus, 54 participants (n = 29 in the PCI and n = 25 in the control group) were included in the study (see Supplementary Appendix B). Patients in each condition were equally likely to receive medication.

Measurement

In addition to basic demographic characteristics (gender, marital status, family residence, education, and family history), the following two scales were assessed:

Depression

Depression were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which is a widely used 20-item self-report scale designed to measure depressive symptoms in a general population. Items are scored on a 4-point scale, with the total of CES-D score ranging between 0 and 60. A score of 16 points or more is generally considered suggestive of a depressive disorder, higher scores imply more severe depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). The coefficient alpha of the CES-D scale of the present study was 0.93.

Pychological Capital (PsyCap)

Positive PsyCap Questionnaire (PPQ) consists of 26 items on a 7-point scale to assess hope, self-efficacy, optimism and resilience (Zhang et al., 2010). It is a reliable and valid measure of PsyCap. In current study, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of PsyCap showed a good fit to the data (χ2/df = 2.075, RMSEA = 0.065, TLI = 0.909, IFI = 0.926). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90. In terms of each subscale, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87 for hope, 0.91 for self-efficacy, 0.86 for optimism, 0.90 for resilience.

Procedure

All subjects gave written informed consent prior to their participation in the study and the study was approved by the ethical review board of Shaoyang University. Participants who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the research were invited to complete the baseline evaluation. Following the baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to either the PCI or CAU group according to a random number generator.

Participants assigned to the PCI group completed four 45-minute weekly sessions of the PCI protocol (see Supplementary Appendix A). Prior to the first intervention, the researcher concentrated upon the introduction of each module and the general explanation of the effects of positive and negative emotions on depression. Following the last treatment session or approximately 4 weeks after the baseline, participants completed post-test sessions, which were identical to the pre-test. To establish the duration of treatment effects, participants in the PCI group completed the assessments 6-month following the post-test session.

Care as usual participants completed the pre-and post-assessment at a 4-week interval. Treatment were offered the PCI protocol after the study was terminated.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 in an intent-to-treat (ITT) basis (PCI = 29, CAU = 25), with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. Primarily outcome measures were analyzed descriptively. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used as a statistical technique to test group differences at post-treatment controlling for the pretreatment scores. Effect sizes including within-group and between- group controlled effect sizes were calculated to establish the magnitude of treatment response (Lakens, 2013).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Demographic characteristics in both PCI group and CAU group at baseline were presented in Supplementary Appendix B. The two groups did not statistically differ in terms of gender, marital status, education, home residence, family history of depression, age (ps > 0.05).

Main Treatment Effects

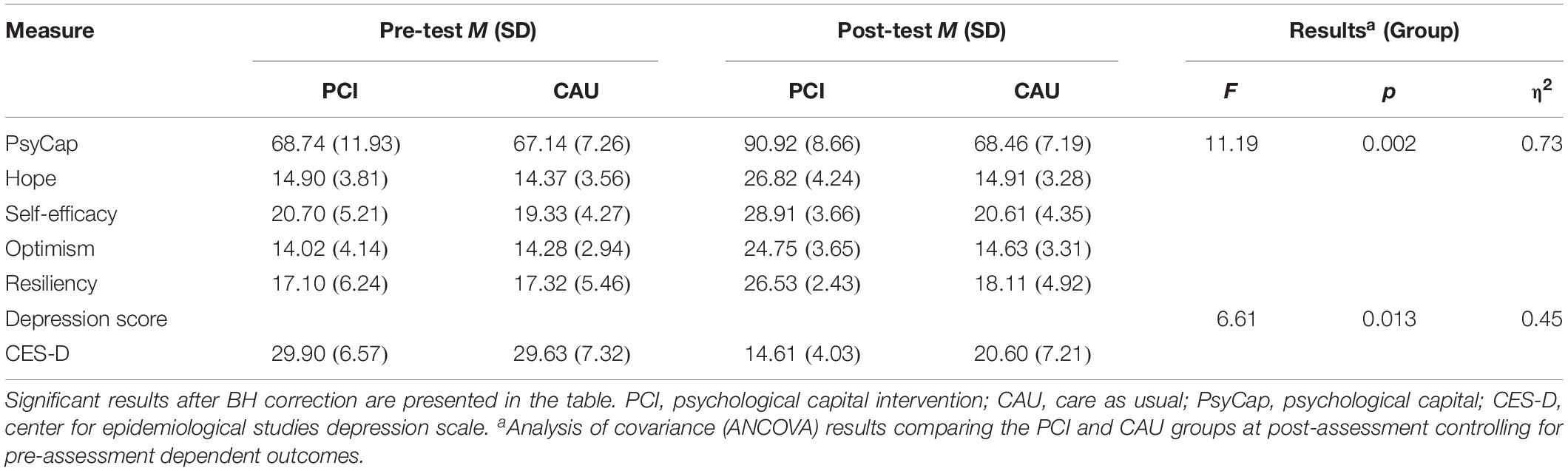

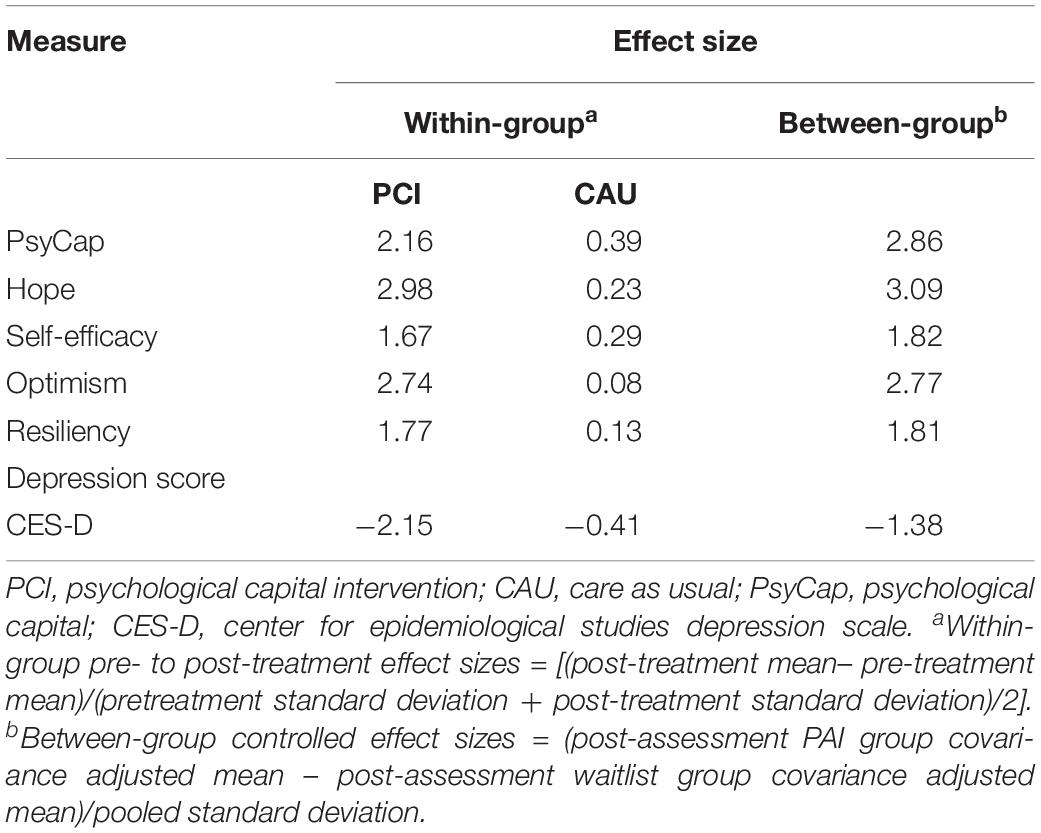

Table 1 displayed the details about the means, standard deviations and results of the ANCOVAs for the main outcomes. The results of ANCOVAs revealed that individuals in the PCI group demonstrated significantly greater PsyCap at post-treatment compared to participants in the CAU group. ANCOVA results also revealed that the PCI group reported experiencing significantly fewer symptoms of depression, at post-treatment relative to participants in the CAU group. As shown in Table 2, a significant treatment effect for the PCI group both within- and between-group was observed.

Maintenance of Treatment Effects

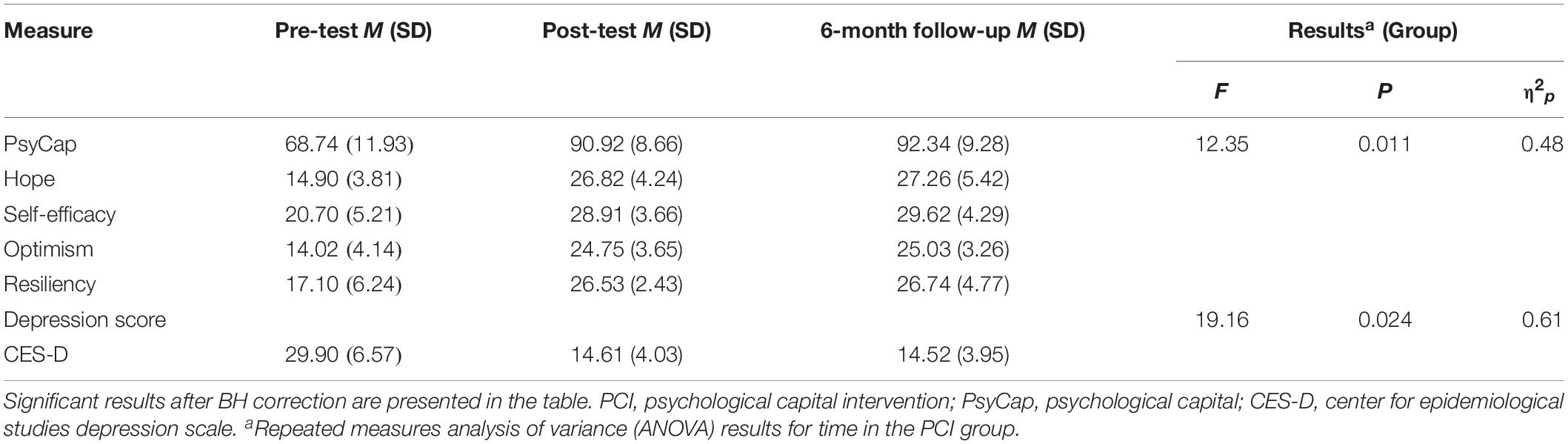

Table 3 depicted the means, standard deviations and results of the repeated measures ANOVAS in the PCI group at pre, post-test and 6-month follow-up. The repeated measures ANOVAs indicated significant main effects of Time. Post hoc test revealed that the main outcomes of significant difference from pre- to post-test and from pre- to 6-month follow-up for the PCI group (ps < 0.05), however, post-test and 6-month follow-up did not significantly differ (ps > 0.05).

Discussion

The findings of the present pilot study confirm that PCI resulted in significant significantly greater increases in PsyCap and decreases in depressive symptoms compared to a CAU group. Treatment effects were large in magnitude and persisted up to 6-months following termination of treatment. The current preliminary findings emphasis the potential value of targeting the positive resources in depression treatment directly, suggesting that PCI may be beneficial for individuals with impairing symptoms of depression. We took the first step in evaluating the efficacy of PCI for depression. Given that this is the first attempt to use the PCI for depression, our research extends the knowledge of treatment of depression and the application of PCI.

The PCI regimen shares much in common with other positive psychological interventions that focused on developing positive emotions as hope, gratitude, interest, pride, inspiration, love, joy and the establishment of strengths, skills, resilience and goals (Hobfoll, 2002; Seligman et al., 2005; Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009; Dunn, 2012; Santos et al., 2013; Carr and Finnegan, 2014; Boumparis et al., 2016; Kwok et al., 2016). The principal differences between the PCI regimen and other similar programs is that combing the four components of PCI, these four resources compose a higherorder construct which is based on the commonalities these four first-order constructs share (Hobfoll, 2002; Luthans et al., 2007a; Avey et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2014; Nolzen, 2018). Integrating with the function of hope, self-efficacy, optimism and resilience, they might yield larger effect size than the sum of parts.

On the basis of these outcome data, we conclude that PCI has not only yield larger effects on PsyCap, but also on depression intervention. It is noteworthy that targeting the positive resources (PsyCap) resulted in reductions in depressive symptoms, changes that were comparable to those prevailing empirically establish interventions (McCarty et al., 2013; Carr and Finnegan, 2014; Reiter and Wilz, 2015; Kwok et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2017). The results may be explained by multiple reasons from the perspective of positive psychology. One explanation might be that PCI teaches the individuals some strategies to develop the positive cognition, emotions and behaviors. These positive resources help the participants to deal with current emotion problems and enhance the capabilities to cope with future stress and adversities. Another explanation might be that individuals are born with the instinct to obtain happiness and the potential for continuous growth. Even individuals suffering from mental disorder such as depressive disorder have positive qualities and abilities which are inhibited compared with normal people. Through intervention regimen like PCI, the inhibited positive abilities developed so that they can recover from depression (Grawe and Grawe-Gerber, 1999; Flückiger and Wüsten, 2009; Reiter and Wilz, 2015). Hence, targeting the positive resource of depression is effective for depression treatment.

Limitations

Strengths of this pilot study also include that we control the common method bias by adopting the self-report and structured interview and we used PCI for depression intervention which provide the new horizon for the treatment. The current findings should be interpreted in the context of several caveats. First, the efficacy of the PCI was evaluated in a small sample, which suggest limited power to detect statistically significant effects. Larger trials should be conducted to replicate and determine the stability of the effect. Second, another limitation of the current study may be the lack of correction for possible alpha inflation, however all tests were a priori planned comparisons and Bonferroni corrections with our small sample size would significantly reduce power. Third, outcomes were only examined at pre-, post-test and after 6-month. These results highlight the need for further research investigating multiple repeated assessments of the outcome and using longitudinal statistical models. In addition, wider recruitment, from other provinces and other ethnic would enhance the power of our data and the generalizability of our finding. These are issues that we are in the process of addressing in follow-up studies.

Implications

This study is the first to investigate the effect of PCI on depression. The findings suggest that the intervention enhanced the levels of PsyCap, which in turn contribute to consequent decrease in depression symptoms. The current findings have several implications for clinical and public health in suggesting viable targets for the development of (1) education campaigns and health promotion and maintaining individual health or (2) treatment plans for depression or (3) other psychopathology.

Firstly, future public health messaging should emphasis how individuals using a variety of positive resources (e.g., PsyCap) as both prevention and management. Individuals who are not currently depressed but are interested in maintaining positive health could focus on building positive resources. That is, developing hope, self-efficacy, optimism and resilience.

Secondly, depression individuals benefit from developing positive resources (e.g., PCI) and over time can develop a suite of personalized options to be reliably used to prevent or manage depression symptoms.

Thirdly, the current findings also have promising application for a range of psychiatric conditions, including subsyndromal cases that fail to meet diagnostic criteria but may experience the functional impairment. The current intervention was tailored to depression, nevertheless, the PCI might be applied to other forms of psychopathology like anxiety, phobia or increasing the personals’ strengths, well-being, or other positive psychological resources.

Conclusion

Results of the current pilot study provided initial support for the efficacy of PCI for depression treatment. The findings support the potential value of explicitly targeting the absence of positive resources in depression. Future research using more rigorous control conditions in larger samples is needed.

Data Availability

The datasets for this manuscript are not publicly available because the data involved the subject’s privacy, the subjects didn’t agree to public. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to cmpzb25nQHNpbmEuY24=.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of Shaoyang University with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Shaoyang University.

Author Contributions

RS, NS, and XS designed the study. RS analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Outstanding Youth Program of Education Department of Hunan Province (15B222).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the people who participated in the study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01816/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Descriptive summaries of the treatment outcome measures of PsyCap for the PCI group.

APPENDIX A | Psychological Capital Intervention (PCI) Protocol.

APPENDIX B | Patient Demographic Characteristics.

References

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., and Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 22, 127–152. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.20070

Bakker, D. J., Lyons, S. T., and Conlon, P. D. (2017). An exploration of the relationship between psychological capital and depression among first-year doctor of veterinary medicine students. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 44, 50–62. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0116-006R

Barth, J., Munder, T., Gerger, H., Nüesch, E., Trelle, S., Znoj, H., et al. (2016). Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: a network meta-analysis. Focus 14, 229–243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001454

Bos, S. C., Macedo, A., Marques, M., Pereira, A. T., Maia, B. R., Soares, M. J., et al. (2013). Is positive affect in pregnancy protective of postpartum depression? Rev. Bras. Psiquiatria 35, 5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.rbp.2011.11.002

Boumparis, N., Karyotaki, E., Kleiboer, A., Hofmann, S. G., and Cuijpers, P. (2016). The effect of psychotherapeutic interventions on positive and negative affect in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect Dis. 202, 153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.019

Burns, D. D., and Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1992). Therapeutic empathy and recovery from depression in cognitive-behavioral therapy: a structural equation model. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 60, 441–449. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.441

Carr, A., and Finnegan, L. (2014). The Say ‘Yes’ to Life (SYTL) program: a positive psychology group intervention for depression. J. Contemp. Psychother. 45, 109–118. doi: 10.1007/s10879-014-9269-9

Castonguay, L. G., Schut, A. J., Aikens, D. E., Constantino, M. J., Laurenceau, J.-P., Bologh, L., et al. (2004). Integrative cognitive therapy for depression: a preliminary investigation. J. Psychother. Integr. 14, 4–20. doi: 10.1037/1053-0479.14.1.4

Clark, L. A., and Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 100, 316–336. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316

Cuijpers, P., Andersson, G., Donker, T., and van Straten, A. (2011). Psychological treatment of depression: results of a series of meta-analyses. Nordic J. Psychiatry 65, 354–364. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.596570

Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., Warmerdam, L., and Andersson, G. (2008). Psychological treatment of depression: a meta-analytic database of randomized studies. BMC Psychiatry 8:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-36

Dunlop, D. D., Manheim, L. M., Song, J., Lyons, J. S., and Chang, R. W. (2005). Incidence of disability among preretirement adults: the impact of depression. Am. J. Public Health 95, 2003–2008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050948

Dunn, B. D. (2012). Helping depressed clients reconnect to positive emotion experience: current insights and future directions. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 19, 326–340. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1799

Flückiger, C., and Wüsten, G. (2009). Ressourcenaktivierung: Ein Manual für die Praxis. 2. Aufl. Bern: Hans Huber.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). “Positive emotions broaden and build,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, eds E. A. Plant and P. G. Devine (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 1–53. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

Grawe, K., and Grawe-Gerber, M. (1999). Resource activation: a primary change principle in psychotherapy. Psychotherapeut 44, 63–73.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 6, 307–324. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Fang, A., and Asnaani, A. (2012). Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depress. Anxiety 29, 409–416. doi: 10.1002/da.21888

Hollon, S. D., and Ponniah, K. (2010). A review of empirically supported psychological therapies for mood disorders in adults. Depress. Anxiety 27, 891–932. doi: 10.1002/da.20741

Kwok, S. Y., Gu, M., and Kit, K. T. K. (2016). Positive psychology intervention to alleviate child depression and increase life satisfaction. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 26, 350–361. doi: 10.1177/1049731516629799

Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and anovas. Front. Psychol. 4:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

Layous, K., Chancellor, J., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 123, 3–12. doi: 10.1037/a0034709

Lindahl, M., and Archer, T. (2013). Depressive expression and anti-depressive protection in adolescence: stress, positive affect, motivation and self-efficacy. Psychology 04, 495–505. doi: 10.4236/psych.2013.46070

Liu, L., Chang, Y., Fu, J., Wang, J., and Wang, L. (2012). The mediating role of psychological capital on the association between occupational stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese physicians: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 12:219. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-219

Lopez, A. D., and Mathers, C. D. (2006). Measuring the global burden of disease and epidemiological transitions: 2002-2030. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 100, 481–499. doi: 10.1179/136485906X97417

Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 23, 695–706. doi: 10.1002/job.165

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., and Peterson, S. J. (2010). The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 21, 41–67. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.20034

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., and Norman, S. M. (2007a). Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with preformance and satisfication. Pers. Psychol. 60, 541–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

Luthans, F., Youssef, C. M., and Avolio, B. J. (2007b). Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Luthans, F., and Youssef, C. M. (2004). Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 33, 143–160. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.01.003

McCarty, C. A., Violette, H. D., Duong, M. T., Cruz, R. A., and McCauley, E. (2013). A randomized trial of the positive thoughts and action program for depression among early adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 42, 554–563. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.782817

Newman, A., Ucbasaran, D., Zhu, F., and Hirst, G. (2014). Psychological capital: a review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 35, S120–S138. doi: 10.1002/job.1916

Nolzen, N. (2018). The concept of psychological capital: a comprehensive review. Manag. Rev. Q. 68, 237–277. doi: 10.1007/s11301-018-0138-6

Papakostas, G. I., and Ionescu, D. F. (2014). Updates and trends in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 75, 1419–1421. doi: 10.4088/jcp.14ac09610

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Measur. 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

Raes, F., Smets, J., Wessel, I., Van Den Eede, F., Nelis, S., Franck, E., et al. (2014). Turning the pink cloud grey: dampening of positive affect predicts postpartum depressive symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 77, 64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.04.003

Reiter, C., and Wilz, G. (2015). Resource diary: a positive writing intervention for promoting well-being and preventing depression in adolescence. J. Posit. Psychol. 11, 99–108. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1025423

Santos, V., Paes, F., Pereira, V., Arias-Carrión, O., Silva, A. C., Carta, M. G., et al. (2013). The role of positive emotion and contributions of positive psychology in depression treatment: systematic review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 9, 221–237. doi: 10.2174/1745017901309010221

Seligman, M. E., Steen, T. A., Park, N., and Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 60, 410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.60.5.410

Shen, X., Yang, Y. L., Wang, Y., Liu, L., Wang, S., and Wang, L. (2014). The association between occupational stress and depressive symptoms and the mediating role of psychological capital among Chinese university teachers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 14:329. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0329-1

Sin, N. L., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 65, 467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593

Taylor, C. T., Lyubomirsky, S., and Stein, M. B. (2017). Upregulating the positive affect system in anxiety and depression: outcomes of a positive activity intervention. Depress. Anxiety 34, 267–280. doi: 10.1002/da.22593

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Keywords: depression, psychological capital, intervention, positive psychology, pilot study

Citation: Song R, Sun N and Song X (2019) The Efficacy of Psychological Capital Intervention (PCI) for Depression From the Perspective of Positive Psychology: A Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 10:1816. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01816

Received: 09 March 2019; Accepted: 22 July 2019;

Published: 07 August 2019.

Edited by:

Changiz Mohiyeddini, Northeastern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Fu-Sheng Tsai, Cheng Shiu University, TaiwanRita Francisco, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal

Copyright © 2019 Song, Sun and Song. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruijun Song, cmpzb25nQHNpbmEuY24=

†Co-first authors

Ruijun Song

Ruijun Song Nana Sun3†

Nana Sun3†