95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 18 April 2019

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00487

This article is part of the Research Topic Dyadic Coping View all 19 articles

In Iran, dual-career couples face many stressors due to their demands of balancing work and family. Moreover, the experience of this stress can negatively affect partners’ martial quality. Recent studies have shown the positive impact of dyadic coping on well-being; however, a majority of this research has been conducted with Western cultures. As such, there is a dearth of literature on understanding how supportive and common dyadic coping may have a positive association with work-family stress for couples in Iran. Using a sample of 206 heterosexual dual-career couples from Iran, this study examines the associations between job stress and marital quality, and possible moderating effects of common and perceived partner supportive dyadic coping. As predicted, job stress was negatively associated with marital quality, and this association with further moderated by gender, such that women who experienced greater job stress also reported lower marital quality. Additionally, dyadic coping moderated the association between job stress and marital quality. Common dyadic coping attenuated the negative association between job stress and marital quality. The findings shed light on the possible beneficial effects of teaching supportive and common dyadic coping techniques to dual-career couples in Iran.

Iran is in transition from a society that once focused on agricultural economics to one that is now focused on industrial economy, urbanization, mass media development, and public education (Askari-Nodoushan et al., 2009). In recent decades, family values, structures, and norms have undergone wide-ranging changes due to the shifts in the structure of the Irian society, because of industrialization, urbanization and the expansion of mass media, as well as cultural and value changes, individualism from the dissemination of Western ideas and values (Azadarmaki et al., 2012). These changes have led to shifts in the structure of societies, which can be best observed in changes in the cultural ideals of individualism (Askari-Nodoushan et al., 2009). Examples of this change include the increased age of marriage in 2016 (women: from 18.4 to 23.4; men: from 25 to 27.4), decreasing fertility from 6.3 in 1986 to 1.75 in 2016 (Shojaei and Yazdkhasti, 2017), and increased divorce rates from 8.6 in 1991 to 34.1 in 2018 (Statistics Center of Iran, 2018).

Changes in the Iranian society have also had an impact on the formation and expansion of a nuclear family (Abbasi-Shavazi and McDonald, 2008), wherein husbands were once thought to have the authority in the household due to their economic responsibility, and wives were thought to be responsible for child-rearing (Richter et al., 2014). Due to the modernization of society, women’s increase in educational attainment and rates of employment (Saraie and Tajdari, 2011), women are now thought to have an equal role in all the decision-making of issues related to family (Askari-Nodoushan et al., 2009). The participation of women in the workforce has caused fundamental changes in family and occupational structures, including the increase in dual-career couples (Schaer et al., 2008), so that it has gradually become the dominant model of marital life in most countries (Haddock et al., 2006).

Despite the increase of women in the workforce, which comes along with managing the demands of work-related stress, women in Iran are still expected to attend to their family roles as wives and mothers (Rafatjah, 2011). Consequently, in dual-career families, both partners must perform multiple tasks as well as maintain efforts to create a balance between these roles (Atta et al., 2013). Research on 155 dual-career couples in Bangladesh has shown that childcare, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and marital relations are the most important challenges for dual-career couples (Sultana et al., 2014). Consequently, the balance of work and family roles can be stressful (Rafatjah, 2011), and may lead to conflicts between partners (Soleimanian and Nazari, 2007; Nazari and Goli, 2008; Oreizi et al., 2011), which over time can lead to decreased marital quality.

Given the overwhelming number of dual-career couples in Iran (Khosravi et al., 2010; Motahari et al., 2012; Fallahchai and Khaluee, 2016; Mazhari et al., 2016), investigating the unique stressors these couples may face is an important concern for mental health practitioners working with these couples (Saginak and Saginak, 2005). Few studies have investigated marital quality in dual-career couples in a collectivist context (Quek et al., 2011), which leaves a dearth of understanding on factors can affect partners’ marital quality. Given the changing cultural climate in Iran, it is necessary for relational scholars to examine ways in which dual-career couples can cope with stress in order to possible reduce marital dissatisfaction (Soleimanian and Nazari, 2007). Additionally, dyadic coping has been found to moderate the associations between work-family conflicts in Canada (Lapierre and Allen, 2006), as well as preventing the harmful effects of stress on relational functioning and physical and mental health (Levesque et al., 2014; Merz et al., 2014).

Job stress is defined as a reaction to the experience of stressors related to work domains (Wierda-Boer et al., 2009), which can be accompanied by role-overload due to occupational and family responsibilities. Not surprisingly, job stress can also affect within the family due to stress spillover and crossover (Neff and Karney, 2005), ultimately leading to a decrease in marital quality in both partners. Stress spillover refers to how the stress experienced from an aspect of life (e.g., occupation) spills over causing stress to another aspect (e.g., family) (Geurts and Demerouti, 2003). For example, when a person has a stressful day at work this may affect the way they interact with their partner (e.g., shutting down), causing stress at home. Work-family spillover is defined as the transfer of the effects of work and family on one another that generate similarity between work and family (Edwards and Rothbard, 2000) and work-family spillover transfers from one domain (e.g., occupation) to another domain (family) (Haines et al., 2006; Schaer et al., 2008). Stress spillover in marital relationships can lead to negative behaviors, such as anger toward the partners (Schulz et al., 2004), which, can negatively affects marital satisfaction (Randall and Bodenmann, 2017). Stress crossover refers to the interpersonal transfer of stress from one partner to another (Haines et al., 2006). For example, one partner’s experience of stress can affect their partner’s experience as well (Randall et al., 2017). Bodenmann et al. (2007) demonstrated that stress outside the relationship (external stress; Randall and Bodenmann, 2009) significantly triggers stress within the relationship (internal stress), which is commonly found to be associated with marital quality.

Not surprisingly, the experience of job stress has been found to reduce marital quality in both partners (Obradovic and Cudina-Obradovic, 2009). A majority of research in this domain has been conducted in the United States or with Western samples and has found that men were affected by work-family conflict as much as women, however, women were more likely to be affected by family-work conflict than men (e.g., Tatman et al., 2006). However, recent research is starting to examine these associations with non-Western samples. For example, Sandberg et al. (2012) examined the association between family-to-work spillover job satisfaction and health using a sample of 1026 married workers in Singapore. Results of this study showed that marital distress was a significant predictor of job satisfaction and health. Taken together, given the negative associations between job-stress and marital quality (Neff and Karney, 2007; van Steenbergen et al., 2011) and increased rates of divorce in Iran (National Organization for Civil Registration, 2017), it is important to consider ways in which couples could cope with stress that may prevent the harmful effects of stress on relational well-being (Randall and Bodenmann, 2009, 2017; Merz et al., 2014).

The conceptualization of stress as a dyadic construct, one that affects both partners in a romantic relationship (Randall and Bodenmann, 2009). Given this conceptualization, partners can attempt to cope with stress by engaging in (positive) dyadic coping. Specifically, dyadic coping refers to the ways in which partners cope with stress in the context of their relationship (Bodenmann et al., 2011). Although positive and negative forms of dyadic coping exist (see Bodenmann, 2005), here we focus specifically on positive forms of dyadic coping given its strong association with relational well-being for couples around the world (Falconier et al., 2016). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis by Falconier et al. (2015) found that supportive and common dyadic coping were found to be powerful (positive) predictors of relationship satisfaction (e.g., Bodenmann and Cina, 2006; Ruffieux et al., 2014).

Positive forms of dyadic coping can be classified into three categories: supportive dyadic coping, delegated dyadic coping, and common dyadic coping (Bodenmann, 2005). Supportive dyadic coping refers to the efforts that one couple makes to express empathic understanding, solidarity with his/her partner, and providing practical. For example, if a partner is under stress, his/her partner may respond by expressing empathy and then providing practical advice on how to help cope with the stress. Delegated dyadic coping refers to a new division of tasks in which one partner asks for practical support. For example, a partner takes over certain tasks of the partner when his/her partner asks for help. Lastly, common dyadic coping represents the joint efforts of couples to deal with stress. For example, both partners engage in joint problem solving when they face a stressful situation (e.g., work-family conflict). Furthermore, research suggests that common dyadic coping plays an important role in reducing negative daily stress (e.g., Bodenmann et al., 2011; Falconier et al., 2015), increasing the quality of the relationship, reducing symptoms of depression and distress in both couples (Rottmann et al., 2015).

Prior research has focused on the direct association between dyadic coping and marital quality (e.g., Iafrate et al., 2012; Falconier et al., 2015; Gasbarrini et al., 2015), as well as on the indirect association (i.e., moderation) between variables (e.g., Falconier et al., 2013; Levesque et al., 2014; Herzberg and Sierau, 2016).

Bodenmann et al. (2006a) who examined the association between dyadic coping and marital quality among 90 Swiss couples over a 2 year period found that dyadic coping was positively correlated with relationship quality for couples. Additionally, using a sample of 187 heterosexual couples from Switzerland, Levesque et al. (2014) investigated dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction. Results from this study showed that, among men, perspective-taking significantly increased their partner’s desire to use positive dyadic coping strategies. For female, empathy increased their partners’ coping strategies.

Dyadic coping has also been shown to have moderating effects on the association between stress and individual and relational well-being. For example, supportive and common dyadic coping were found to reduce the negative associations between immigration stress on relationship satisfaction for 104 Latino immigrant couples in the United States, especially for women (Falconier et al., 2013). The results of the study by Merz et al. (2014), examined the moderation role of dyadic coping in association between internal stress and relationship satisfaction on 131 couples, showed that dyadic coping reduced the effects of chronic stress on relationship satisfaction especially in women. Most recently, Hilpert et al. (2018) studied stress and coping processes at both between- and within-person levels in 84 dual-earning couples in China. The results of this study indicated that at the between persons level, both in men and women, the association between stress and relationship outcomes was decreased if the partner provided more support, but at the level of within persons, the results indicated that partner support had only a significant buffer effect in women. Taken together, supportive dyadic coping has been shown to be effective in reducing stress and improving the quality of relationships (Vedes et al., 2013); however, this has yet to be examined in dual- career couples, especially those from Iran, which is the goal of the present study.

The goal of the present study is to investigate the association between job stress and marital quality in dual-career couples from Iran. Additionally, given the robust positive associations between dyadic coping and relational outcomes found across cultures (Falconier et al., 2016), we also examine how supportive and common dyadic coping may moderate the association between job stress and marital quality. To do so, we collected dyadic data from both partners in a romantic relationship, which allows us to examine both actor and partner effects (Kenny et al., 2006). Actor effects refer to the associations of partner’s reports of their independent variable (job stress) on their dependent variable (marital quality), whereas partner effects refer to the associations between how one partner’s reports job stress are associated with their partner’s marital quality.

In sum, we tested the following hypotheses (H):

H1: In line with research that has found a positive association between job stress and marital conflict in dual-career couples from the United States and Western Europe (Michel et al., 2009; Allen and Finkelstein, 2014; Fellows et al., 2016; Yucel, 2017), it is hypothesized that a partner’s job stress will be negatively associated with one’s own (actor effect) and their partner’s marital quality (partner effect).

H2a: Based upon prior studies suggesting that supportive dyadic coping moderates the negative association between stress and relationship quality (Bodenmann, 2005; Bodenmann et al., 2010; Vedes et al., 2013; Rottmann et al., 2015; Breitenstein et al., 2018) it is hypothesized that perception of partner’s of supportive dyadic coping will moderate the association between job stress and his/her own marital quality. Moreover, it is hypothesized that actual reports of supportive dyadic coping will be associated with partner’s reports of marital quality (partner effect).

H2b: Based on prior studies that have found a positive association between common dyadic coping and relationship quality (Bodenmann, 2005; Bodenmann et al., 2010; Papp and Witt, 2010), it is hypothesized that common dyadic coping will moderate the association between job stress and marital quality, such that for individuals who perceive their partner as engaging in common dyadic coping, they will also show a positive association between their coping with job stress and their marital quality (actor effects). Additionally, we hypothesize that we will also find a positive association between self-reported job stress and perception of marital quality.

Although studies have found men and women report the same levels of stress in work-family conflict (Barnett and Gareis, 2006; Martinengo et al., 2010), men and women show different behavioral patterns in response to stress; women showed a higher level of negative spillover than men (Mennino et al., 2005). Related to job-stress in particular, Barling et al. (2004) have shown that there are important gender differences in the degree to which job and family stress is transmitted to negative family processes, including cognitions, behaviors, and interactions within the family that lead to negative outcomes. Given this, we also examine whether gender will moderate the association between job stress and marital quality.

This research was reviewed and approved by the ethics and research committee of Hormozgan University prior to the start of data collection. All participants provided written and informed consent. They were recruited in person from civil institutions, local police, education and social services in Shiraz, Iran. Participants had to meet the following criteria in order to participate (a) married for at least 2 years, (b) both of the partners had to have been working at least 2 years, and (c) have full-time employment status. Eligible couples were given two packages of research questionnaire in separate envelopes with a unique ID. Participants were asked to fill in their questionnaires independently from their spouse and send back the questionnaires upon completion.

Data were collected from 238 couples; however, 32 couples were removed from the current analysis for having incomplete data. The final sample consisted of 206 heterosexual couples (n = 412 individuals). On average, the men were 35.7 years old (SD = 9.1 years; range: 25–62 years) and women were 31.1 years old (SD = 9.3 years; range: 21–51 years). The sample was highly education with 62.6% of participants reporting having B.A. degrees, 26.2% had M.A. and Ph.D. degrees, and 11.2% had high school diplomas. Participants reported being married for an average of 11 years (SD = 7.2). The average number of children was 2 ranging from 1 to 3.

Standard demographic information relating to age, gender, level of education, length of relationship, number of children was collected. See Table 1 for descriptive information.

Participant’s perception of job stress was measured using the Persian version of the Health and Safety (HSE) Management Standards Indicator Tool (HSE-MS IT; Cousins et al., 2004). The HSE-MS IT is a 35-item on a 5-point Likert type scale (1 = never to 5 = always) developed to measure work-related stress risk factors at an organizational level (Marcatto et al., 2014). This measure showed good reliability in the current study for men and women (α = 0.82 and 0.85, respectively).

Participants’ reports of marital quality were measured using the Persian version of Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Sanai Zakir, 2000; DAS; Spanier, 2001). The DAS includes 32 items used to assess partners’ marital quality (e.g., Fişiloǧlu and Demir, 2000; Chiara et al., 2014; Bachem et al., 2018). Twenty-seven items are rated on a 6- point Likert scale (15 items: 0 = always disagree to 5 = always agree; 12 items 0 = never to 5 = all the time); two items are on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never to 4 = everyday); two items are yes/no type questions (0 = no 1 = yes); and one is on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = extremely unhappy to 7 = perfect). Items are summed, wherein higher scores are reflective of greater marital quality. Results of current study showed good reliability for men and women (α = 0.86 and 0.87, respectively).

The Persian version of the Dyadic Coping Inventory (DCI; Fallahchai et al., 2017) was used to measure participant’s reports of dyadic coping. The DCI is a self-report instrument consisting of 37 items, with responses arranged on a 5-point likert-type scale (1 = never to 5 = always). The DCI contains six subscales to measure each partner’s stress communication and specific dyadic coping; however, for the purpose of our study, we examined the following: emotion-focused dyadic coping, problem-focused dyadic coping, and common dyadic coping. To create a composite score of perceived partner supportive dyadic coping, we took the average of emotion-focused and problem-focused supportive dyadic coping. For each area assessed, participants reported on their own and their perceived partner behaviors; reports of perceived partner dyadic coping were used in the present analysis. This measure showed good reliability for perceived partner supportive dyadic coping for men and women (α = 0.83 and 0.84, respectively), and common dyadic coping for men and women (α = 0.88 and 0.89, respectively).

Age (e.g., Michel et al., 2009; Spell et al., 2009), relationship length, and the number of children (e.g., Hassan et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Mache et al., 2015) have been previously found to be negatively associated with work-family conflicts. As such, we controlled for these variables in our analysis.

Dyadic data – data collected from two partners – contains sources of interdependence between partners’ reports (Kenny et al., 2006). Analyses were run with Actor-Partner Interdependence-Model (APIMs) (Cook and Kenny, 2005) which allows researchers to control for the interdependence between reporting partners’ scores, and also examine both actor and partner effects. To analyze both actor and partner effects, we used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for distinguishable dyads (e.g., men and women) because SEM allows for the estimation the association between variables free from measurement error, while also including the examination of the goodness of fit of the base models and the measurement structure of all study variables simultaneously (Ledermann and Kenny, 2017).

In order to evaluate model fit, we used the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; 0.01 = excellent fit; 0.05 = good fit; 0.08 = mediocre fit; MacCallum et al., 1996), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI; 0.95 = excellent fit; 0.90 = adequate fit; Hu and Bentler, 1999). Each model contained the control variables noted above. All analyses were conducted using AMOS 21 (Arbuckle, 2006).

Descriptive statistics for the study variables are presented in Table 1. Results showed significant gender differences in self-reported job stress; wives reported significantly higher scores in job stress (t = -2.04, p = 0.03). Interestingly, compared to wives, husbands reported higher marital quality (t = 1.90, p = 0.02). We did not find differences between husbands and wives reports of engaging in partner supportive dyadic coping.

Significant correlations among the scales ranged from (-0.43 < r > 0.77) for both husbands and wives. Table 2 shows correlations among measured variables for husbands (above the diagonal), for wives (below the diagonal).

A model with the direct actor and partner effects of job stress predicting change in spouses’ marital quality was examined. Gender was included in the models to test whether the associations between job stress and marital quality differed between husbands and wives. The model fit well: χ2 = 8.789, p < 0.45, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.02.

It was hypothesized that job stress would have a main effect on marital quality after controlling for age, marital duration, and number of child. Results indicated that there was a significant negative association between one’s own job stress and marital quality for both husbands and wives (actor effect; husbands: β = -0.32, p < 0.001; wives: β = -0.42, p < 0.001). Additionally, we found partner effects for job stress and marital quality for both husbands (β = -0.41, p < 0.001) and wives (β = -0.34, p < 0.001); one’s reports of job stress was negatively associated with their partner’s reports of marital quality (see Figure 1).

Moreover, results indicated the actor association differed by gender. For example, significant gender differences were found in associations between job stress and marital quality (β = -0.39, p < 0.01), for wives. Specifically, when wives reported greater job stress they also reported lower marital quality. However, gender did not moderate the partner effect.

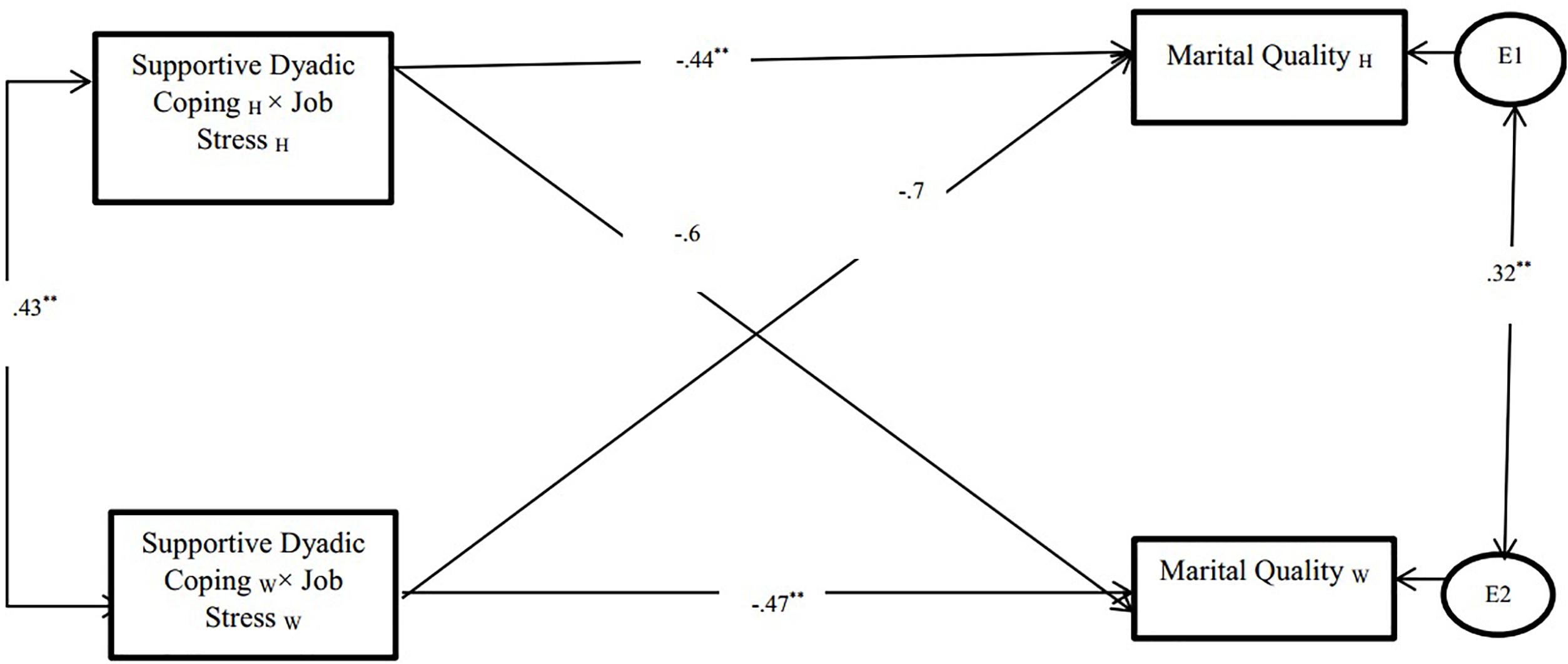

The Goodness-of-fit for the model with perceived partner supportive dyadic coping as the moderator was very good: χ2 = 6.45; p = 0.451; with CFI = 0.92 and RMSEA = 0.04. All the actor effects were significant and in the expected direction, but the partner effects were not significant.

The structural path from the interaction between husbands’ perceived partner supportive dyadic coping and husbands’ job stress to husbands’ marital quality was significant (β = -0.44, p < 0.001), which suggests that when husbands perceive their wife as engaging in supportive dyadic coping they report greater marital quality. Additionally, results found that perceived partner supportive dyadic coping moderated the association between job stress and marital quality, this effect was significant for wives (β = -0.47, p < 0.001).

Results showed that the interaction between husbands’ perceived partner supportive dyadic coping and husbands’ job stress to wives’ marital quality was not significant (β = -0.6, p > 0.05), and the interaction between wives’ perceived partner supportive dyadic coping and wives’ job stress to husbands’ marital quality was not significant (β = -0.7, p > 0.05). Therefore, the partner effects were not significant both for husbands and wives (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Association between perceived partner supportive dyadic coping and marital quality. ∗∗p < 0.01; W, Wives; H, Husbands. “Supportive dyadic coping” was measured by partner’s perception of their partner’s engagement in dyadic coping.

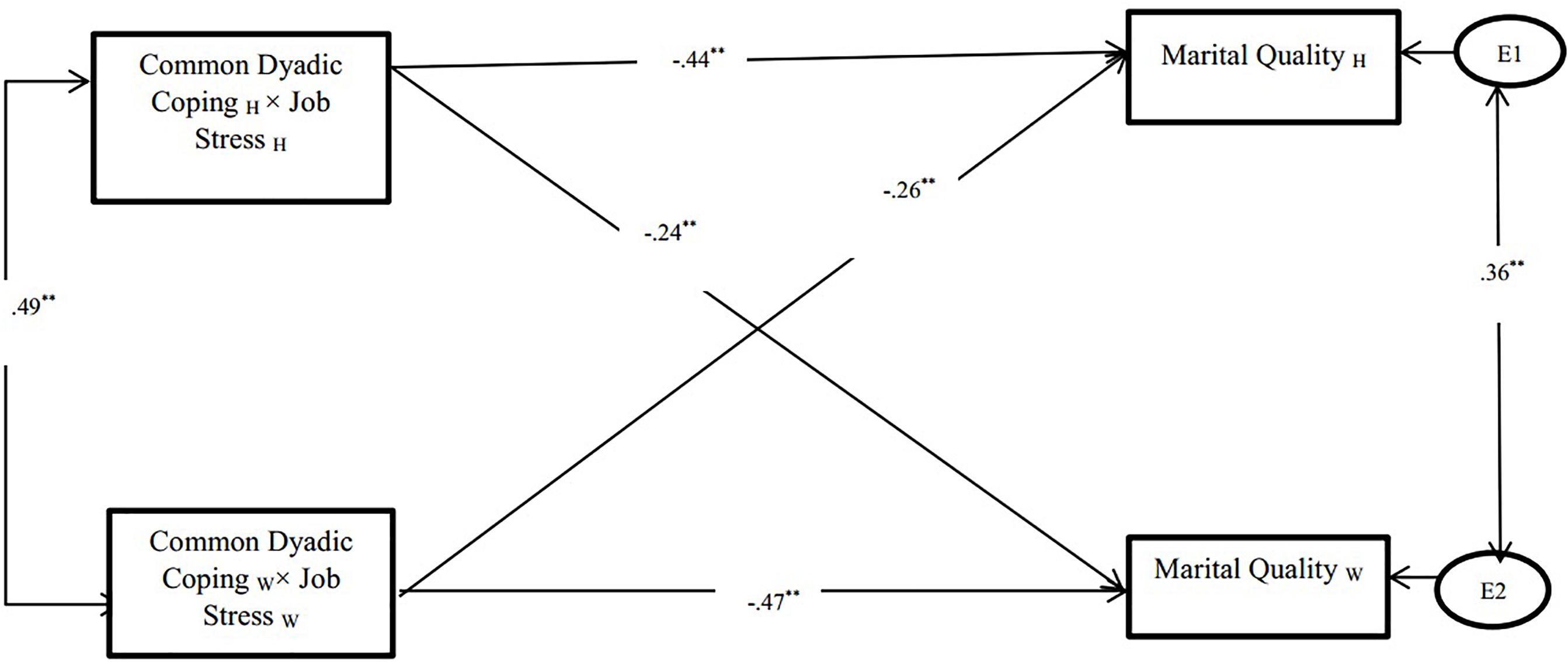

Results of estimating the APIM revealed very good Goodness-of-fit for the model (χ2 = 5.23, p = 0.32 with CFI = 0.96 and RMSEA = 0.031).

The structural path from the interaction between common dyadic coping and job stress to marital quality was significant. This effect was found for both husbands (β = -0.44, p < 0.001) and wives (β = -0.47, p < 0.001).

Results showed that the interaction between husbands’ common dyadic coping and husbands’ job stress to wives’ marital quality was significant (β = -0.24, p < 0.05). Moreover, the interaction between wives’ common dyadic coping and wives’ job stress to husbands’ marital quality was significant (β = -0.26, p < 0.05) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Association between common dyadic coping and marital quality. ∗∗p < 0.01; W, Wives; H, Husbands.

Taken together, results revealed that perceived partner supportive dyadic coping and common dyadic coping moderated the negative association between job stress and marital quality in expected directions.

Given the change of social-cultural structure in Iran (Askari-Nodoushan et al., 2009; Azadarmaki et al., 2012), and the increase of dual-career couples (Soleimanian and Nazari, 2007; Ghodrati, 2015), the aim of this study was to investigate the association between job stress and marital quality for dual- career couples, and assess possible moderating associations of supportive and common dyadic coping. Results from this study largely support our hypotheses, however, interesting gender differences emerged, which are explained below.

We hypothesized that a partner’s job stress would be negatively associated with one’s own marital quality (actor effect) and their partner’s marital quality (partner effect). Findings of this study found that both wives and husbands in a dual- career marriage report similar levels of job stress, and these reports were similarly associated with marital quality (both actor and partner effects). This finding is in line with the results of previous studies (Anafarta, 2011; Šimunic and Gregov, 2012; Efeoǧlu and Ozcan, 2013) suggesting dual- career couples experience a lot of job stress, which is associated with marital quality (Buck and Neff, 2012; Sandberg et al., 2012).

We hypothesized that supportive and common dyadic coping would moderate the association between job stress and their own marital quality (actor effect) and partner’s reports of marital quality (partner effect). Below we expand upon the results from these models.

Data from this study supported our hypothesis, suggesting that perceived partner supportive dyadic coping moderated the negative association of job stress and marital quality for husbands and wives. Said differently, when individuals reported greater partner’s supportive dyadic coping, they also experienced higher level of marital quality. These results are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Wunderer and Schneewind, 2008; Papp and Witt, 2010; Falconier et al., 2013; Herzberg, 2013; Nicholls and Perry, 2016), which have found supportive dyadic coping to have a beneficial effect on marital quality (Bodenmann et al., 2006b, 2016; Falconier et al., 2013; Breitenstein et al., 2018).

Data from this study supported our hypothesis, suggesting that common dyadic coping moderated the negative association of job stress (actor and partner effect) for both husbands and wives. These results are in line with previous studies that have found that common dyadic coping may play a moderating role in association between stress and marital outcomes (i.e., relationship satisfaction, marital quality) (e.g., Bodenmann, 2005; Bodenmann et al., 2010; Falconier et al., 2013). Given that common dyadic coping refer to partners’ perception of handling stressful situations, these results support understanding stress and coping as a dyadic context (Randall and Bodenmann, 2009, 2017). In situations where one of the partners, or both, faces a significant stressor, viewing stress as a dyadic stress (i.e., “our stress”) and engaging in common dyadic coping can help partners cope with the stress, by fostering a sense of “we-ness” within the couple (Vedes et al., unpublished). Therefore, this strong association between positive dyadic coping techniques and ability to cope with stress suggests that the way in which couples manage and interact with stress and conflict in their marital life is considered as the most important determinants of marital satisfaction (Vedes et al., 2013), and the satisfaction of the relationship may dependent on positive dyadic coping during times of distress (Falconier et al., 2015).

Another goal of the present study was to examine possible gender differences between job stress and marital quality. Results from this study revealed that when wives reported greater job stress they also reported lower marital quality, however, this effect was not found for husbands. One’s is a very important culture is a very important factor for predicting gender differences in the coping process between couples (Hilpert et al., 2016). In Iran Khojasteh mehr et al. (2013) in their research with 150 couples, found that dyadic coping in women had a greater effect on their marital satisfaction than men, because the support that women under stress receive from their husbands has a great influence on the quality of their marital life.

Additionally, women may engage in greater dyadic coping behaviors due to their greater attentiveness to their partner’s needs (Bodenmann et al., 2006a), as women are thought to be more sensitive to changes in their marital relationships (Bodenmann et al., 2004). This greater engagement in dyadic coping behaviors may be particularly true for couples who come from a society wherein men and women carry different roles and responsibilities in the relationship (see Hilpert et al., 2016).

Although this study is one of the few studies that has used a dyadic sample of dual-career couples from Iran to examine associations between job stress and marital quality, it is notwithstanding limitations. First, data for this study was based on cross-sectional data, which limits our ability to make causal inferences and further test associations between stress spillover and crossover. To better address for stress spillover (i.e., external stress to internal stress; see Randall and Bodenmann, 2009) and crossover future research should utilize longitudinal data (e.g., Bodenmann and Cina, 2006; Bodenmann et al., 2006a). Second, this study relied on the use of self-report assessments, which may contain bias (Spector, 1994). As such, future research is encouraged to use a multi-method approach that includes more objective measures, such as observational measures and interview methods, which may provide a better understanding of the nature of how and when supportive dyadic coping is utilized especially given the cultural context. Third, it is important to examine other variables that may further moderate the association between job stress and marital quality. One such variable is the presence of children in the home. Having a child affects the work-family conflict (Mennino et al., 2005), and negatively affects the individual’s job performance (Patel et al., 2006), as such the presence of children may. Lastly, this study chose to focus on supportive and common dyadic coping due to its robust positive associations with relationship well-being (see Falconier et al., 2015). To further understand the role of dyadic coping in the context of dual-career couples, future research should also examine other types of dyadic coping (e.g., delegated and negative dyadic coping), which may help relationship researchers and clinicians working with couples identify other forms of effective coping on the relationship between job stress and marital quality. Also, considering the cultural differences between Iran and Western countries regarding gender roles and its possible effects on family-work conflict of the couples, it is suggested that future research would measure specific gender roles.

The number of dual- career couples is increasing in Iran (Ghodrati, 2015). In addition to stress common to all couples (Jackson et al., 2016), some couples may experience higher levels of stress due to work-family conflicts (Nohe et al., 2015), which can have negative implications on their relational well-being (Randall and Bodenmann, 2009, 2017). Recent research cross-culturally has shown that supportive and common dyadic coping have buffering effect on reducing the impact of stress and can enhance marital quality (Bodenmann et al., 2010; Falconier et al., 2016).

Perhaps not surprisingly, the results of this study found that job stress was negatively associated with marital quality; however, perceived partner supportive and common dyadic coping moderated the association. The findings of this study have improved our understanding of stress processes in marital quality of dual- career couples. The findings of this study improve our understanding of stress and coping processes for dual-career couples in Iran, and the importance of engaging in supportive and common dyadic coping. These findings suggest that dyadic coping plays a very important role both in reducing stress and improving the quality of relationships in dual-career couples in Iran. The findings of this study are important implications for relationship researchers and clinical experts in understanding the effects of work-family stress on marital quality in dual-career couples and their gender differences in their rate and effect of job stress. Moreover, teaching coping skills can be effective both in reducing stress and improving the quality.

MF organized the database and performed the statistical analysis. RF wrote the first draft of the manuscript and performed the statistical analysis. MF, RF, and AR wrote the sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., and McDonald, R. (2008). “Family change in Iran: religion, revolution, and the state,” in Proceedings of the International Family Change: Ideational Perspectives, eds R. Jayakody, A. Thornton, and W. Axinn (New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group).

Allen, T. D., and Finkelstein, L. M. (2014). Work-family conflict among members of full-time dual-earner couples: an examination of family life stage, gender, and age. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 19, 376–384. doi: 10.1037/a0036941

Anafarta, N. (2011). The relationship between work-family conflict and job satisfaction: a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. Int. J. Bus. Manage. 6:168. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v6n4p168

Askari-Nodoushan, A., Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., and Sadeghi, R. (2009). Mothers, daughters and marriage: intergenerational differences in ideas and attitudes of marriage in Yazd. Womens Strateg. Stud. 11, 7–36.

Atta, M., Adil, A., Shujja, S., and Shakir, S. (2013). Role of trust in marital satisfaction among single and dual-career couples. Int. J. Res. Stud. Psychol. 2, 53–62.

Azadarmaki, T., Sharifi Saei, M., Isari, M., and Talebi, S. (2012). The typology of premarital sex patterns in Iran. Sociol. Cult. Stud. 2, 1–34.

Bachem, R., Levin, Y., Zhou, X., Zerach, G., and Solomon, Z. (2018). The role of parental posttraumatic stress, marital adjustment, and dyadic self-disclosure in intergenerational transmission of trauma: a family system approach. J. Marit. Fam. Ther. 44, 543–555. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12266

Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., and Frone, M. R. (eds) (2004). Handbook of Work Stress. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12266

Barnett, R. C., and Gareis, K. C. (2006). “Role theory perspectives on work and family,” in The Work and Family Handbook: Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives, Methods, And Approaches, eds M. Pitt-Catsouphes, E. E. Kossek, and S. Sweet (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 209–221.

Bodenmann, G. (2005). “Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning,” in Couples Coping with Stress: Emerging Perspectives on Dyadic Coping, eds T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, and G. Bodenmann (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 33–50.

Bodenmann, G., Charvoz, L., Widmer, K., and Bradbury, T. (2004). Differences in individual and dyadic coping among low and high depressed, partially remitted, and non-depressed persons. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 75–85. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000013655.45146.47

Bodenmann, G., and Cina, A. (2006). Stress and coping among stable satisfied, stable-dissatisfied and separated/divorced Swiss couples: a 5- year prospective longitudinal study. J. Divorce Remarriage 44, 71–89. doi: 10.1300/j087v44n01_04

Bodenmann, G., Ledermann, T., Blattner, D., and Galluzzo, C. (2006a). Associations among everyday stress, critical life events, and sexual problems. J. Nervous Ment. Dis. 194, 494–501. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000228504.15569.b6

Bodenmann, G., Ledermann, T., and Bradbury, T. N. (2007). Stress, sex, and satisfaction in marriage. Pers. Relat. 14, 551–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00171.x

Bodenmann, G., Meuwly, N., Bradbury, T. N., Gmelch, S., and Ledermann, T. (2010). Stress, anger, and verbal aggression in intimate relationships: moderating effects of individual and dyadic coping. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 27, 408–424. doi: 10.1177/0265407510361616

Bodenmann, G., Meuwly, N., and Kayser, K. (2011). Two conceptualizations of dyadic coping and their potential for predicting relationship quality and individual well-being. Eur. Psychol. 16, 255–266. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000068

Bodenmann, G., Pihet, S., and Kayser, K. (2006b). The relationship between dyadic coping and marital quality: a 2-year longitudinal study. J. Fam. Psychol. 20, 485–493. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.485

Bodenmann, G., Randall, A. K., and Falconier, M. K. (2016). Coping in Couples: The Systemic Transactional Model (STM). Couples Coping with Stress: A Cross Cultural Perspective. New York, NY: Routledge, 5–22.

Breitenstein, C. J., Milek, A., Nussbeck, F. W., Davila, J., and Bodenmann, G. (2018). Stress, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction in late adolescent couples. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 35, 770–790. doi: 10.1177/0265407517698049

Buck, A. A., and Neff, L. A. (2012). Stress spillover in early marriage: the role of self-regulatory depletion. J. Fam. Psychol. 26, 698–708. doi: 10.1037/a0029260

Chiara, G., Eva, G., Elisa, M., Luca, T., and Piera, B. (2014). Psychometrical properties of the dyadic adjustment scale for measurement of marital quality with Italian couples. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 127, 499–503. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.298

Cook, W. L., and Kenny, D. A. (2005). the actor-partner interdependence model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 29, 101–109. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000405

Cousins, R., MacKay, C. J., Clarke, S. D., Kelly, C., Kelly, P. J., and McCaig, R. H. (2004). Management standards’ and work related stress in the UK: practical development. Work Stress 18, 113–136. doi: 10.1080/02678370410001734322

Edwards, J. R., and Rothbard, N. P. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: clarifying the relationships between work and family constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 178–199. doi: 10.5465/amr.2000.2791609

Efeoǧlu, I. E., and Ozcan, S. (2013). Work-family conflict and its association with job performance and family satisfaction among physicians. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 7, 43–48.

Falconier, M., Randall, A., and Bodenmann, G. (2016). Couples Coping with Stress – A Cultural Perspective. Abingdon: Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9781315644394

Falconier, M. K., Jackson, J. B., Hilpert, P., and Bodenmann, G. (2015). Dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 42, 28–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.002

Falconier, M. K., Nussbeck, F., and Bodenmann, G. (2013). Immigration stress and relationship satisfaction in Latino couples: the role of dyadic coping. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 32, 813–843. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2013.32.8.813

Fallahchai, R., Fallahi, M., Charhartangi, S. H., and Bodenmann, G. (2017). Psychometric properties and factorial validity of the dyadic coping inventory – the persian version. Curr. Psychol.

Fallahchai, R., and Khaluee, S. (2016). Comparison of quality of life and psychological well-being among dual career couples and single career couples. J. Modern Ind. 7, 19–27.

Fellows, K. J., Chiu, H.-Y., Hill, E. J., and Hawkins, A. J. (2016). Work-family conflict and couple relationship quality: a meta-analytic study. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 37, 509–518. doi: 10.1007/s10834-015-9450-7

Fişiloǧlu, H., and Demir, A. (2000). Applicability of the dyadic adjustment scale for measurement of marital quality with Turkish couples. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 16, 214–218. doi: 10.1027//1015-5759.16.3.214

Gasbarrini, M. F., Snyder, D. K., Iafrate, R., Bertoni, A., Margola, D., Gasbarrini, M. F., et al. (2015). Investigating the relation between shared stressors and marital satisfaction: the moderating effects of dyadic coping and communication. Fam. Sci. 6, 143–149. doi: 10.1080/19424620.2015.1082044

Geurts, S. A. E., and Demerouti, E. (2003). “Work/non-work interface: a review of theories and findings,” in The Handbook of Work and Health Psychology, eds M. J. Schabracq, J. A. M. Winnubst, and C. L. Cooper (Chichester: Wiley), 279–312. doi: 10.1002/0470013400.ch14

Ghodrati, H. (2015). Women’s employment fluctuations in Iran and its deviations from the world trends. J. Soc. Dev. 9, 29–52.

Haddock, S. A., Zimmerman, T. S., Lyness, K. P., and Ziemba, S. J. (2006). Practices of dual earner couples successfully balancing work and family. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 27, 207–234. doi: 10.1007/s10834-006-9014-y

Haines, V. Y., Marchand, A., and Harvey, S. (2006). Crossover of workplace aggression experiences in dual-earner couples. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 11, 305–314. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.305

Hassan, Z., Dollard, M. F., and Winefield, A. H. (2010). Work-family conflict in east vs western countries. Cross Cult. Manage. 17, 30–49. doi: 10.1108/13527601011016899

Herzberg, P. (2013). Coping in relationships: the interplay between individual and dyadic coping and their effects on relationship satisfaction. Anxiety Stress Coping 26, 136–153. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2012.655726

Herzberg, P. Y., and Sierau, S. (2016). “Dyadic coping in German in couples,” in Couples Coping with Stress, eds M. Falconier, A. Randall, and G. Bodenmann (New York, NY: Routledge), 122–126.

Hilpert, P., Randall, A. K., Sorokowski, P., Atkins, D. C., Sorokowska, A., Ahmadi, K., et al. (2016). The associations of dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction vary between and within nations: a 35-nation study. Front. Psychol. 7:1106. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01106

Hilpert, P., Xu, F., Milek, A., Atkins, D. C., Bodenmann, G., and Bradbury, T. N. (2018). Couples coping with stress: between-person differences and within-person processes. J. Fam. Psychol. 32, 366–374. doi: 10.1037/fam0000380

Hu, L.-T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Iafrate, R., Bertoni, A., Margola, D., Cigoli, V., and Acitelli, L. (2012). The link between perceptual congruence and couple relationship satisfaction in dyadic coping. Eur. Psychol. 17, 73–82. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000069

Jackson, G. L., Trail, T. E., Kennedy, D. P., Williamson, H. C., Bradbury, T. N., and Karney, B. R. (2016). The salience and severity of relationship problems among low-income couples. J. Fam. Psychol. 30, 2–11. doi: 10.1037/fam0000158

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., and Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic Data Analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. doi: 10.1037/fam0000158

Khojasteh mehr, R., Naderi, F., and Sodani, M. (2013). The mediating role of dyadic coping on the relationship between marital standards and marital satisfaction. J. Manage. Syst. 3, 47–67.

Khosravi, M., Azami, S., Elahifar, A., and Dekani, M. (2010). Comparison of couples’ marital satisfaction with both single-staffed couples with respect to their general health. Woman Fam. Stud. 3, 27–37.

Lapierre, L. M., and Allen, T. D. (2006). Work-supportive family, family-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 11, 169–181. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169

Ledermann, T., and Kenny, D. A. (2017). Analyzing dyadic data with multilevel modeling versus structural equation modeling: a tale of two methods. J. Fam. Psychol. 31, 442–452. doi: 10.1037/fam0000290

Levesque, C., Lafontaine, M. F., Caron, A., Flesch, J. L., and Bjornson, S. (2014). Dyadic empathy, dyadic coping, and relationship satisfaction: a dyadic model. Eur. J. Psychol. 10, 118–134. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2016.1208698

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., and Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1, 130–149. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

Mache, S., Bernburg, M., Vitzthum, K., Groneberg, D. A., Klapp, B. F., and Danzer, G. (2015). Managing work–family conflict in the medical profession: working conditions and individual resources as related factors. BMJ Open 5:e006871. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006871

Marcatto, F., Colautti, L., Filon, F. L., Luís, O. D., and Ferrante, D. (2014). The HSE management standards indicator tool: concurrent and construct validity. Occup. Med. 64, 365–371. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu038

Martinengo, G., Jacob, J. I., and Jeffrey Hill, E. (2010). Gender and the work-family interface: exploring differences across the family life course. J. Fam. Issues 31, 1363–1390. doi: 10.1177/0192513X10361709

Mazhari, M., Zahrakar, K., Shakarami, M., Davarniya, R., and Abdollah Zadeh, A. (2016). The effect of Relationship Enhancement Program (REP) on reducing marital conflicts of dual- career couples. Iran J. Nurs. 29, 32–44. doi: 10.29252/ijn.29.102.32

Mennino, S. F., Rubin, B. A., and Brayfield, A. (2005). Home-to-job and job-to home spillover: the impact of company policies and workplace culture. Sociol. Q. 46, 107–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2005.00006.x

Merz, C. A., Meuwly, N., Randall, A. K., and Bodenmann, G. (2014). Engaging in dyadic coping: buffering the impact of everyday stress on prospective relationship satisfaction. Fam. Sci. 5, 30–37. doi: 10.1080/19424620.2014.927385

Michel, J. S., Mitchelson, J. K., Kotrba, L. M., LeBreton, J. L., and Baltes, B. B. (2009). A comparative test of work-family conflict models and critical examination of work family linkages. J. Vocat. Behav. 74, 199–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.005

Motahari, Z., Kh, A., Behzadpoor, S., and Azmoodeh, F. (2012). Effectiveness of mindfulness on reducing couple burnout in mothers with ADHD children. J. Fam. Couns. Psychother. 3, 592–612.

National Organization for Civil Registration (2017). The Rate of Marriage and Divorce in Iran. Available at: http://www.sabteahval.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=4773

Nazari, A., and Goli, M. (2008). The effects of solution- focused psychotherapy on the marital satisfaction of dual career couples. J. Knowl. Health 2, 35–40.

Neff, L. A., and Karney, B. R. (2005). To know you is to love you: the implications of global adoration and specific accuracy for marital relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88, 480–497. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.480

Neff, L. A., and Karney, B. R. (2007). Stress crossover in newlywed marriage: a longitudinal and dyadic perspective. J. Marriage Fam. 69, 594–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00394.x

Nicholls, A. R., and Perry, J. L. (2016). Perceptions of coach–athlete relationship are more important to coaches than athletes in predicting dyadic coping and stress appraisals: an actor–partner independence mediation model. Front. Psychol. 7:447. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00447

Nohe, C., Meier, L. L., Sonntag, K., and Michel, A. (2015). The chicken or the egg? A meta-analysis of panel studies of the relationship between work-family conflict and strain. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 522–536. doi: 10.1037/a0038012

Obradovic, J., and Cudina-Obradovic, M. (2009). Work-related stressors of work-family conflict and stress crossover on marriage quality. Društvena Istraživanja 18, 437–460.

Oreizi, H., Dibaji, M., and Sadeghi, M. (2011). Investigation the relationship of work-family conflict with perceived organizational support, job stress and self-mastery in expatriate workers. Res. Clin. Psychol. Couns. 2, 151–170.

Papp, L. M., and Witt, N. L. (2010). Romantic partners’ individual coping strategies and dyadic coping: implications for relationship functioning. J. Fam. Psychol. 24, 551–559. doi: 10.1037/a0020836

Patel, C. J., Govender, V., Paruk, Z., and Ramgoon, S. (2006). Working mothers: family-work conflict, job performance and family/work variables. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 32, 39–45. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v32i2.238

Quek, K. M. T., Knudson-Martin, C., Orpen, S., and Victor, J. (2011). Gender equality during the transition to parenthood: a longitudinal study of dual career couples in Singapore. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 28, 943–962. doi: 10.1177/0265407510397989

Randall, A. K., and Bodenmann, G. (2009). The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004

Randall, A. K., and Bodenmann, G. (2017). Stress and its associations with relationship satisfaction. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 13, 96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.010

Randall, A. K., Totenhagen, C. J., Walsh, K. J., Adams, C., and Tao, C. (2017). Coping with workplace minority stress: associations between dyadic coping and anxiety among women in same-sex relationships. J. Lesbian Stud. 21, 70–87. doi: 10.1080/10894160.2016.1142353

Richter, J., Rostami, A., and Ghazinour, M. (2014). Marital satisfaction, coping, and social support in female medical staff members in Tehran University Hospitals. Interpersona 8, 115–127. doi: 10.5964/ijpr.v8i1.139

Rottmann, N., Hansen, D. G., Larsen, P. V., Nicolaisen, A., Flyger, H., Johansen, C., et al. (2015). Dyadic coping within couples dealing with breast cancer: a longitudinal, population-based study. Health Psychol. 34, 486–495. doi: 10.1037/hea0000218

Ruffieux, M., Nussbeck, F. W., and Bodenmann, G. (2014). Long-term prediction of relationship satisfaction and stability by stress, coping, communication, and well-being. J. Divorce Remarriage 55, 485–501. doi: 10.1080/10502556.2014.931767

Saginak, K. A., and Saginak, M. A. (2005). Balancing work and family: equity, gender, and marital satisfaction. Fam. J. 13, 162–166. doi: 10.1177/1066480704273230

Sanai Zakir, B. (2000). Marriage and Family Assessment Scales. Tehran: Besat Publications. doi: 10.1177/1066480704273230

Sandberg, J. G., Yorgason, J. B., Miller, R. B., and Hill, E. J. (2012). Family to-work spillover in Singapore: marital distress, physical and mental health, and work satisfaction. Fam. Relat. 61, 1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00682.x

Saraie, H., and Tajdari, A. (2011). Left discourse in Iran: global ideas in Iranian context. Sociol. Cult. Stud. 1, 7–23.

Schaer, M., Bodenmann, G., and Klink, T. (2008). Balancing work and relationship: couples coping enhancement training (CCET) in the workplace. Appl. Psychol. 57, 71–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00355.x

Schulz, M. S., Cowan, P. A., Pape Cowan, C., and Brennan, R. T. (2004). Coming home upset: gender, marital satisfaction, and the daily spillover of workday experience into couple interactions. J. Fam. Psychol. 18, 250–263. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.250

Shojaei, J., and Yazdkhasti, B. (2017). A systematic review of studies of fertility decline in the last two decades. Womens Strateg. Stud. 19, 137–159.

Šimunic, A., and Gregov, L. (2012). Conflict between work and family roles and satisfaction among nurses in different shift systems in Croatia: a questionnaire survey. Arch. Ind. Hygiene Toxicol. 63, 189–197. doi: 10.2478/10004-1254-63-2012-2159

Soleimanian, A., and Nazari, A. M. (2007). Investigation and comparison of marital satisfaction of dual- career couples and one couple employed. Couns. Res. 6, 103–122. doi: 10.2478/10004-1254-63-2012-2159

Spanier, G. B. (2001). Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS): User’s manual MHS. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?id=eaM9mwEACAAJ

Spector, P. E. (1994). Using self-report questionnaires in OB research: a comment on the use of a controversial method. J. Organ. Behav. 15, 385–392. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150503

Spell, C. S., Haar, J., and O’Driscoll, M. (2009). Managing work-family conflict: exploring individual and organizational options. N. Z. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 9, 200–215. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150503

Statistics Center of Iran (2018). Marriage and Divorce in the First and Second Years of Marriage in Iran. Available at: https://www.amar.org.ir

Sultana, N., Tabassum, A., and Abdullah, A. M. (2014). Dual-career couples in Bangladesh: exploring the challenges. Can. J. Fam. Youth 6, 29–57.

Tatman, A. W., Hovestadt, A. J., Yelsma, P., Fenell, D. L., and Canfield, B. S. (2006). Work and family conflict: an often overlooked issue in couple and family therapy. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 28, 39–51. doi: 10.1007/s10591-006-9693-4

van Steenbergen, E. F., Kluwer, E. S., and Karney, B. R. (2011). Workload and the trajectory of marital satisfaction in newlyweds: job satisfaction, gender, and parental status as moderators. J. Fam. Psychol. 25, 345–355. doi: 10.1037/a0023653

Vedes, A., Nussbeck, F., Bodenmann, G., Lind, W., and Ferreira, A. (2013). Psychometric properties and validity of the dyadic coping inventory in portuguese. Swiss J. Psychol. 72, 149–157. doi: 10.1024/1421-0185/a000108

Wang, P., Lawler, J. J., and Shi, K. (2010). Work-family conflict, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and gender: evidences from Asia. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 17, 298–308. doi: 10.1177/1548051810368546

Wierda-Boer, H. H., Gerris, J. R., and Vermulst, A. A. (2009). Personality, stress, and work-family interferences in dual earner couples. J. Individ. Differ. 30, 6–19. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001.30.1.6

Wunderer, E., and Schneewind, K. (2008). The relationship between marital standards, dyadic coping and marital satisfaction. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 462–476. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.405

Keywords: job stress, Iranian dual-career couples, dyadic coping, marital quality, work-family conflict

Citation: Fallahchai R, Fallahi M and Randall AK (2019) A Dyadic Approach to Understanding Associations Between Job Stress, Marital Quality, and Dyadic Coping for Dual-Career Couples in Iran. Front. Psychol. 10:487. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00487

Received: 21 June 2018; Accepted: 19 February 2019;

Published: 18 April 2019.

Edited by:

Gianluca Castelnuovo, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Tanja Zimmermann, Hannover Medical School, GermanyCopyright © 2019 Fallahchai, Fallahi and Randall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Reza Fallahchai, ci5mYWxsYWhjaGFpQGhvcm1vemdhbi5hYy5pcg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.