95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 19 February 2019

Sec. Environmental Psychology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00305

This article is part of the Research Topic The Natural World as a Resource for Learning and Development: From Schoolyards to Wilderness View all 13 articles

Do experiences with nature – from wilderness backpacking to plants in a preschool, to a wetland lesson on frogs—promote learning? Until recently, claims outstripped evidence on this question. But the field has matured, not only substantiating previously unwarranted claims but deepening our understanding of the cause-and-effect relationship between nature and learning. Hundreds of studies now bear on this question, and converging evidence strongly suggests that experiences of nature boost academic learning, personal development, and environmental stewardship. This brief integrative review summarizes recent advances and the current state of our understanding. The research on personal development and environmental stewardship is compelling although not quantitative. Report after report – from independent observers as well as participants themselves – indicate shifts in perseverance, problem solving, critical thinking, leadership, teamwork, and resilience. Similarly, over fifty studies point to nature playing a key role in the development of pro-environmental behavior, particularly by fostering an emotional connection to nature. In academic contexts, nature-based instruction outperforms traditional instruction. The evidence here is particularly strong, including experimental evidence; evidence across a wide range of samples and instructional approaches; outcomes such as standardized test scores and graduation rates; and evidence for specific explanatory mechanisms and active ingredients. Nature may promote learning by improving learners’ attention, levels of stress, self-discipline, interest and enjoyment in learning, and physical activity and fitness. Nature also appears to provide a calmer, quieter, safer context for learning; a warmer, more cooperative context for learning; and a combination of “loose parts” and autonomy that fosters developmentally beneficial forms of play. It is time to take nature seriously as a resource for learning – particularly for students not effectively reached by traditional instruction.

The intuition that “nature is good for children” is widely held, and yet, historically, the evidence for this intuition has been uncompelling, with a distressing number of weak studies and inflated claims. Now, however, an impressive body of work has accrued and converging lines of evidence paint a convincing picture.

This integrative mini-review (see Supplementary Material for methods) summarizes what we know about the role of nature experiences in learning and development. It draws on a wide array of peer-reviewed scientific evidence, ranging from research in the inner city, to the study of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, to neurocognitive and physiological explorations. Our overarching question was, “do nature experiences promote learning and child development?”

Throughout our review, we took care to distinguish between evidence for cause-and-effect relationships and evidence for associations; causal language (e.g., “affects,” “boosts,” “is reduced by”) is used only where justified by experimental evidence. Where converging, but not experimental, evidence points to a likely cause-and-effect relationship, our language is qualified accordingly (e.g., “seems to increase”). Table 1 summarizes recent advances in this area and explains how those advances contribute to our confidence in a cause-and-effect relationship between nature and learning and development.

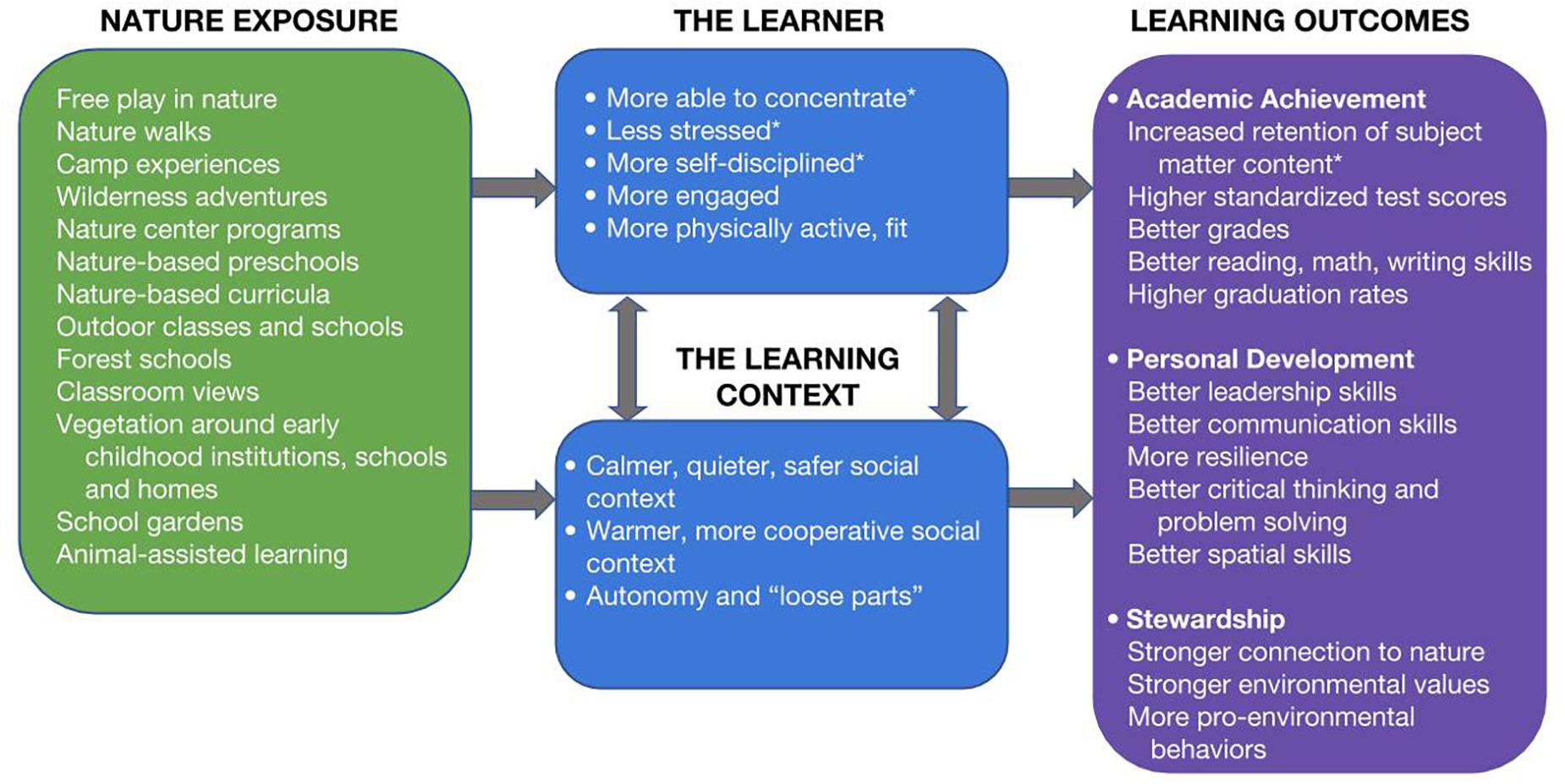

What emerged from this critical review was a coherent narrative (Figure 1): experiences with nature do promote children’s academic learning and seem to promote children’s development as persons and as environmental stewards – and at least eight distinct pathways plausibly contribute to these outcomes. Below, we discuss the evidence for each of the eight pathways and then the evidence tying nature to learning, personal development, and the development of stewardship.

Figure 1. Nature-based learning: exposures, probable mechanisms, and outcomes. This Figure summarizes the state of the scientific literature on nature and learning. The items and pathways here emerged from our review as opposed to guiding our review; thus each item listed has been empirically associated with one or more other items in the figure. Relationships for which there is cause-and-effect evidence are indicated with an asterisk; for example, “more able to concentrate” is asterisked because experimental research has demonstrated that exposure to nature boosts concentration. Similarly, “increased retention of subject matter” is asterisked because experimental research has demonstrated that exposure to nature in the course of learning boosts retention of that material. Here and throughout this review, causal language (e.g., “affects,” “increases,” “boosts,” “is reduced by”) is used only where experimental evidence (the gold standard for assessing cause-and-effect) warrants. Where converging evidence suggests a causal relationship but no experimental evidence is available, we use qualified causal language (e.g., “seems to increase”). The green box lists forms of nature exposure that have been tied with learning, whether directly (nature -> learning) or indirectly, via one or more of the mechanisms listed (nature -> mechanism -> learning). In this review, “nature” includes experiences of nature not only in wilderness but also within largely human-made contexts. Thus a classroom with a view of trees offers an experience of nature not offered by its counterpart facing the school parking lot. This review encompassed experiences of nature regardless of context – whether through play, relaxation, or educational activities, and in informal, non-formal and formal settings. The blue boxes show probable mechanisms – intermediary variables which have been empirically tied to both nature and learning. For example, the ability to concentrate is rejuvenated by exposure to nature and plays an important role in learning. Natural settings may affect learning both by directly fostering a learner’s capacity to learn and by providing a more supportive context for learning. The purple box lists learning outcomes that have been tied to contact with nature. In this review, “learning” encompasses changes in knowledge, skills, behaviors, attitudes, and values. A database of articles found in the three phases of the review process (ending in 2018) is available at: https://goo.gl/FZ1CA9.

Five of the eight plausible pathways between nature and learning we identified are centered in the learner. Learning is likely to improve when a learner is more attentive (Rowe and Rowe, 1992; Mantzicopoulos and Morrison, 1994); less stressed (Grannis, 1992; Leppink et al., 2016); more self-disciplined (Mischel et al., 1988; Duckworth and Seligman, 2005); more engaged and interested (Taylor et al., 2014 for review); and more physically active and fit (for reviews, see Álvarez-Bueno et al., 2017; Santana et al., 2017). Evidence suggests that contact with nature contributes to each of these states or conditions in learners.

The rejuvenating effect of nature on mentally fatigued adults (e.g., Hartig et al., 1991; Kuo, 2001) and children has been demonstrated in a large body of studies, including field experiments (Faber Taylor and Kuo, 2009) and large-scale longitudinal studies (Dadvand et al., 2015). Students randomly assigned to classrooms with views of greenery perform better on concentration tests than those assigned to purely “built” views or windowless classrooms (Li and Sullivan, 2016). Nature’s rejuvenating effects on attention have been found in students going on field trips (van den Berg and van den Berg, 2011), Swedish preschoolers (Mårtensson et al., 2009), children in Chicago public housing (Faber Taylor et al., 2002), and 5 to 18-year-olds with ADHD (e.g., Kuo and Faber Taylor, 2004), using measures of attention ranging from parent and teacher ratings (O’Haire et al., 2013) to neurocognitive tests (Schutte et al., 2015).

The stress-reducing effects of nature have been documented in adults in a large body of controlled experiments (see Kuo, 2015; Supplementary Material for review) and the available evidence points to a similar effect in children. Nature has been related to lower levels of both self-reported and physiological measures of stress in children (Bell and Dyment, 2008; Chawla, 2015; Wiens et al., 2016). Recently, an experimental study showed that a window view of vegetation from a high school classroom yields systematic decreases in heart rate and self-reported stress, whereas built views do not (Li and Sullivan, 2016). Further, students learning in a forest setting one day a week showed healthier diurnal rhythms in cortisol in that setting than a comparison group that learned indoors – cortisol dropped over the course of the school day when lessons were held in the forest but not in the classroom – and these effects could not be attributed to the physical activity associated with learning outdoors (Dettweiler et al., 2017).

In adults, the effects of viewing scenes of nature on self-discipline have been demonstrated experimentally using tests of impulse control (Berry et al., 2014; Chow and Lau, 2015). In children, nature contact has been tied to greater self-discipline in children from inner city Chicago (Faber Taylor et al., 2002) to residential Barcelona (Amoly et al., 2014) and in experimental (Sahoo and Senapati, 2014), longitudinal (Ulset et al., 2017), and large-scale cross-sectional studies (Amoly et al., 2014). These benefits have been shown for neurotypical children as well as for children with ADHD (Sahoo and Senapati, 2014) and learning difficulties (Ho et al., 2017). The types of self-discipline assessed include delay of gratification (Faber Taylor et al., 2002) and parent ratings of hyperactivity (Flouri et al., 2014), and the types of “nature” include not just “greenness” but contact with horses in animal-assisted learning (Ho et al., 2017). Note that impulse control effects are not always statistically significant (e.g., Amoly et al., 2014; Schutte et al., 2015). Nonetheless, in general, impulse control is better during or after children’s contact with nature.

Student motivation, enjoyment, and engagement are better in natural settings, perhaps because of nature’s reliably positive effects on mood (e.g., Takayama et al., 2014). In previous reviews (Blair, 2009; Becker et al., 2017) and recent studies (e.g., Skinner and Chi, 2014; Alon and Tal, 2015; Lekies et al., 2015), students and teachers report strikingly high levels of student engagement and motivation, during both student-elected and school-mandated nature activities. Importantly, learning in and around nature is associated with intrinsic motivation (Fägerstam and Blom, 2012; Hobbs, 2015), which, unlike extrinsic motivation, is crucial for student engagement and longevity of interest in learning. The positivity of learning in nature seem to ripple outward, as seen in learners’ engagement in subsequent, indoor lessons (Kuo et al., 2018a), ratings of course curriculum, materials, and resources (Benfield et al., 2015) and interest in school in general (Blair, 2009; Becker et al., 2017), as well as lower levels of chronic absenteeism (MacNaughton et al., 2017). Encouragingly, learning in nature may improve motivation most in those students who are least motivated in traditional classrooms (Dettweiler et al., 2015).

While the evidence tying green space to physical activity is extremely mixed (see Lachowitz and Jones, 2011 for review), children’s time outdoors is consistently tied to both higher levels of physical activity and physical fitness: the more time children spend outdoors, the greater their physical activity, the lesser their sedentary behavior, and the better their cardiorespiratory fitness (Gray et al., 2015). Importantly, cardiorespiratory fitness is the component of physical fitness most clearly tied to academic performance (Santana et al., 2017). Further, there is some indication greener school grounds can counter children’s trend toward decreasing physical activity as they approach adolescence: in one study, girls with access to more green space and woodlands, and boys with access to ball fields, were more likely to remain physically active as they got older (Pagels et al., 2014). This pattern is echoed in later life: in older adults, physical activity declines with age – but among those living in greener neighborhoods the decline is smaller (Dalton et al., 2016).

In addition to its effects on learners, natural settings and features may provide a more supportive context for learning in at least three ways. Greener environments may foster learning because they are calmer and quieter, because they foster warmer relationships, and because the combination of “loose parts” and relative autonomy elicits particularly beneficial forms of play.

Both formal and informal learning are associated with a greater sense of calmness or peace when conducted in greener settings (Maynard et al., 2013; Nedovic and Morrissey, 2013; Chawla et al., 2014). Problematic and disruptive behaviors such as talking out of turn or pushing among children are less frequent in natural settings than in the classroom (Bassette and Taber-Doughty, 2013; Nedovic and Morrissey, 2013; O’Haire et al., 2013; Chawla et al., 2014). Further, in greener learning environments, students who previously experienced difficulties in traditional classrooms are better able to remove themselves from conflicts and demonstrate better self-control (Maynard et al., 2013; Ruiz-Gallardo et al., 2013; Swank et al., 2017). The social environment of the classroom has long been recognized as important for learning (Rutter, 2000). Calmer environments have been tied to greater student engagement and academic success (Wessler, 2003; McCormick et al., 2015).

Images of nature have prosocial effects in adults (e.g., Weinstein et al., 2009) and greener settings are tied to the development of meaningful and trusting friendships between peers (White, 2012; Chawla et al., 2014; Warber et al., 2015). Maynard et al. (2013) theorize that natural settings provide a less restrictive context for learning than the traditional classroom, giving children more freedom to engage with one another and form ties. Indeed, learning in greener settings has been consistently tied to the bridging of both socio-cultural differences and interpersonal barriers (e.g., personality conflicts) that can interfere with group functioning in the classroom (White, 2012; Cooley et al., 2014; Warber et al., 2015). Finally, learning in nature facilitates cooperation and comfort between students and teachers, perhaps by providing a more level playing-field wherein the teacher is seen as a partner in learning (Scott and Colquhoun, 2013). More cooperative learning environments promote student engagement and academic performance (Patrick et al., 2007; McCormick et al., 2015).

In his “theory of loose parts,” Nicholson (1972) posited that the “stuff” of nature – sticks, stones, bugs, dirt, water – could promote child development by encouraging creative, self-directed play. Indeed, teachers’ and principals’ observations suggest children’s play becomes strikingly more creative, physically active, and more social in the presence of loose parts (e.g., Bundy et al., 2008, 2009). Interestingly, it appears that nature, loose parts, and autonomy can each independently contribute to outcomes (see Bundy et al., 2009; Niemiec and Ryan, 2009; Studente et al., 2016, respectively), raising the possibility of synergy among these factors. Although the effects of loose parts play on child development have yet to be quantitatively demonstrated (Gibson et al., 2017), the potential contributions of more creative, more social, more physically active play to cognitive, social and physical development seem clear.

In school settings, incorporating nature in instruction improves academic achievement over traditional instruction. In a randomized controlled trial of school garden-based instruction involving over 3,000 students, students gained more knowledge than waitlist control peers taking traditional classes; moreover, the more garden-based instruction, the larger the gains (Wells et al., 2015). Further, among the over 200 other tests of nature-based instruction’s academic outcomes, the vast majority of findings are positive (for reviews, see Williams and Dixon, 2013; Becker et al., 2017) – and here, too, the most impressive findings come from studies employing the largest doses of nature-based instruction (e.g., Ernst and Stanek, 2006). Findings have been consistently positive across diverse student populations, academic subjects, instructors and instructional approaches, educational settings, and research designs.

Interestingly, both the pedagogy and setting of nature-based instruction may contribute to its effects. Hands-on, student-centered, activity-based and discussion-based instruction each outperform traditional instruction—even when conducted indoors (Granger et al., 2012; Freeman et al., 2014; Kontra et al., 2015). And simply conducting traditional instruction in a more natural setting may boost outcomes. In multiple studies, the greener a school’s surroundings, the better its standardized test performance – even after accounting for poverty and other factors (e.g., Sivarajah et al., 2018)—and classrooms with green views yield similar findings (Benfield et al., 2015; although c.f. Doxey et al., 2009). The frequency of positive findings on nature-based instruction likely reflects the combination of a better pedagogy and a better educational setting.

In and outside the context of formal instruction, experiences of nature seem to contribute to additional outcomes. First, not only do experiences of nature enhance academic learning, but they seem to foster personal development – the acquisition of intrapersonal and interpersonal assets such as perseverance, critical thinking, leadership, and communication skills. While quantitative research on these outcomes is rare, the qualitative work is voluminous, striking, and near-unanimous (for reviews, see Cason and Gillis, 1994; Williams and Dixon, 2013; Becker et al., 2017). Teachers, parents, and students report that wilderness and other nature experiences boost self-confidence, critical thinking, and problem-solving (e.g., Kochanowski and Carr, 2014; Truong et al., 2016) as well as leadership and communication skills such as making important decisions, listening to others, and voicing opinions in a group (e.g., Jostad et al., 2012; Cooley et al., 2014). Students emerge more resilient, with a greater capacity to meet challenges and thrive in adverse situations (Beightol et al., 2012; Cooley et al., 2014; Harun and Salamuddin, 2014; Warber et al., 2015; Richmond et al., 2017). Interestingly, greener everyday settings may also boost positive coping (Kuo, 2001) and buffer children from the impacts of stressful life events (Wells and Evans, 2003).

And second, spending time in nature appears to grow environmental stewards. Adults who care strongly for nature commonly attribute their caring to time, and particularly play, in nature as children – and a diverse body of studies backs them up (for review, see Chawla and Derr, 2012). Interestingly, the key ingredient in childhood nature experiences that leads to adult stewardship behavior does not seem to be conservation knowledge (knowledge of how and why to conserve). Although knowledge of how and why to conserve, which could presumably be taught in a classroom setting, has typically been assumed to drive stewardship behavior, it is relatively unimportant in predicting conservation behavior (Otto and Pensini, 2017). By contrast, an emotional connection to nature, which may be more difficult to acquire in a classroom, is a powerful predictor of children’s conservation behavior, explaining 69% of the variance (Otto and Pensini, 2017). Indeed, environmental attitudes may foster the acquisition of environmental knowledge (Fremery and Bogner, 2014) rather than vice versa. As spending time in nature fosters an emotional connection to nature and, in turn, conservation attitudes and behavior, direct contact with nature may be the most effective way to grow environmental stewards (Lekies et al., 2015).

Do experiences with nature really promote learning? A scientist sampling some of the studies in this area might well be dismayed initially – as we were – at the frequency of weak research designs and overly optimistic claims. But a thorough review reveals an evidence base stronger, deeper, and broader than this first impression might suggest: weak research designs are supplemented with strong ones; striking findings are replicated in multiple contexts; the research on nature and learning now includes evidence of mechanisms; and findings from entirely outside the study of nature and learning point to the same conclusions.

Robust phenomena are often robust because they are multiply determined. The eight likely pathways between exposure to nature and learning identified here may account for the consistency of the nature-learning connection. Certainly it seems likely that increasing a student’s ability to concentrate, interest in the material, and self-discipline simultaneously would enhance their learning more than any of these effects alone. Moreover, in a group setting, effects on individual learners improve the learning context; when Danika fidgets less, her seatmates Jamal and JiaYing experience fewer disruptions and concentrate better; when Danika, Jamal, and JiaYing are less disruptive, the whole class learns better. These synergies – within and between students – may help explain how relatively small differences in schoolyard green cover predict significant differences in end-of-year academic achievement performance (e.g., Matsuoka, 2010; Kuo et al., 2018b).

An important question arose in the course of our review: is nature-based instruction effective for students for whom traditional instruction is ineffective? Although this review was not structured to systematically assess this question, the benefits of nature-based learning for disadvantaged students were a striking leitmotif in our reading. Not only can nature-based learning work better for disadvantaged students (McCree et al., 2018; Sivarajah et al., 2018), but it appears to boost interest in uninterested students (Dettweiler et al., 2015; Truong et al., 2016), improve some grades (Camassao and Jagannathan, 2018), and reduce disruptive episodes and dropouts among “at risk” students (Ruiz-Gallardo et al., 2013). Nature-based learning may sometimes even erase race- and income-related gaps (e.g., Taylor et al., 1998). Further, anecdotes abound in which students who ordinarily struggle in the classroom emerge as leaders in natural settings. If nature is equigenic, giving low-performing students a chance to succeed and even shine, the need to document this capacity is pressing. In the United States, where sixth graders in the richest school districts are four grade levels ahead of children in the poorest districts (Reardon et al., 2017), this need is urgent.

Fully assessing and making use of the benefits of nature-based instruction can serve all children. The available evidence suggests that experiences of nature help children acquire some of the skills, attitudes, and behaviors most needed in the 21st century. “Non-cognitive factors” such as perseverance, self-efficacy, resilience, social skills, leadership, and communication skills – so important in life beyond school (National Research Council, 2012) – are increasingly recognized by the business community and policy makers as essential in a rapidly changing world. And for generations growing up in the Anthropocene, environmental stewardship may be as important as any academic content knowledge.

We conclude it is time to take nature seriously as a resource for learning and development. It is time to bring nature and nature-based pedagogy into formal education – to expand existing, isolated efforts into increasingly mainstream practices. Action research should assess the benefits of school gardens, green schoolyards and green walls in classrooms. Principals and school boards should support, not discourage, teachers’ efforts to hold classes outdoors, take regular field trips, and partner with nearby nature centers, farms, and forest preserves. Teachers who have pioneered nature-based instruction should serve as models and coaches, helping others address its challenges and take full advantage of its benefits.

All authors co-wrote and edited the manuscript. MK provided leadership for decisions of content, framing, and style and led the creation of the Figure and Table. MB created the SoNBL literature database on which this review is based. CJ serves as the principal investigator of the Science of Nature-Based Learning Collaborative Research Network project; in addition to initiating this project and substantially shaping the Figure and Table, she solicited feedback from Network members.

This literature review was conducted under the auspices of the Science of Nature-Based Learning Collaborative Research Network (NBLR Network) supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. NSF 1540919. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank the members of the NBLR Network for their diverse contributions of expertise, skills, resources and passion for connecting children to nature: Marc Berman, Judy Braus, Greg Cajete, Cheryl Charles, Louise Chawla, Scott Chazdon, Angie Chen, Avery Cleary, Nilda Cosco, Andrea Faber Taylor, Megan Gunnar, Erin Hashimoto-Martell, Peter Kahn, Sarah Milligan Toffler, Robin Moore, Scott Sampson, David Sobel, David Strayer, Jason Watson, Sheila Williams Ridge, Dilafruz Williams, and Tamra Willis.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00305/full#supplementary-material

Alon, N. L., and Tal, T. (2015). Student self-reported learning outcomes of field trips: the pedagogical impact. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 37, 1279–1298. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2015.1034797

Álvarez-Bueno, C., Pesce, C., Cavero-Redondo, I., Sánchez-López, M., Garrido-Miguel, M., and Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. (2017). Academic achievement and physical activity: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 140:e20171498. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1498

Amoly, E., Dadvand, P., Forns, J., López-Vicente, M., Basagaña, X., Julvez, J., et al. (2014). Green and blue spaces and behavioral development in Barcelona schoolchildren: the breathe project. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 1351–1358. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408215

Bassette, L. A., and Taber-Doughty, T. (2013). The effects of a dog reading visitation program on academic engagement behavior in three elementary students with emotional and behavioral difficulties: a single case design. Child Youth Care Forum 42, 239–256. doi: 10.1007/s10566-013-9197-y

Becker, C., Lauterbach, G., Spengler, S., Dettweiler, U., and Mess, F. (2017). Effects of regular classes in outdoor education settings: a systematic review on students’ learning, social and health dimensions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:E485. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14050485

Beightol, J., Jevertson, J., Gray, S., Carter, S., and Gass, M. A. (2012). Adventure education and resilience enhancement: a mixed methods study. J. Exp. Educ. 35, 307–325.

Bell, A. C., and Dyment, J. E. (2008). Grounds for health: the intersection of school grounds and health-promoting schools. Environ. Educ. Res. 14, 77–90. doi: 10.1080/13504620701843426

Benfield, J. A., Rainbolt, G. N., Bell, P. A., and Donovan, G. H. (2015). Classrooms with nature views: evidence of different student perceptions and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 47, 140–157. doi: 10.1177/0013916513499583

Berry, M. S., Sweeney, M. M., Morath, J., Odum, A. L., and Jordan, K. E. (2014). The nature of impulsivity: visual exposure to natural environments decreases impulsive decision-making in a delay discounting task. PLoS One 9:e97915. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097915

Blair, D. (2009). The child in the garden: an evaluative review of the benefits of school gardening. J. Environ. Educ. 40, 15–38. doi: 10.3200/JOEE.40.2.15-38

Bundy, A. C., Luckett, T., Naughton, G. A., Tranter, P. J., Wyver, S. R., Ragen, J., et al. (2008). Playful interaction: occupational therapy for all children on the school playground. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 62, 522–527. doi: 10.5014/ajot.62.5.522

Bundy, A. C., Luckett, T., Tranter, P. J., Naughten, G. A., Wyver, S. R., Ragen, J., et al. (2009). The risk is that there is ”no risk”: a simple innovative intervention to increase children’s activity levels. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 17, 33–45. doi: 10.1080/09669760802699878

Camassao, M. J., and Jagannathan, R. (2018). Nature thru nature: creating natural science identities in populations of disadvantaged children through community education partnership. J. Environ. Educ. 49, 30–42. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2017.1357524

Cason, D., and Gillis, H. L. (1994). A meta-analysis of outdoor adventure programming with adolescents. J. Exp. Educ. 17, 40–47. doi: 10.1177/105382599401700109

Chawla, L. (2015). Benefits of nature contact for children. J. Plan. Lit. 30, 433–452. doi: 10.1177/0885412215595441

Chawla, L., and Derr, V. (2012). “The development of conservation behaviors in childhood and youth,” in The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology, ed. S. D. Clayton (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 527–555.

Chawla, L., Keena, K., Pevec, I., and Stanley, E. (2014). Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health Place 28, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.001

Chow, J. T., and Lau, S. (2015). Nature gives us strength: exposure to nature counteracts ego-depletion. J. Soc. Psychol. 155, 70–85. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2014.972310

Cooley, S. J., Holland, M. J. G., Cumming, J., Novakovic, E. G., and Burns, V. E. (2014). Introducing the use of a semi-structured video diary room to investigate students’ learning experiences during an outdoor adventure education groupwork skills course. High. Educ. 67, 105–121. doi: 10.1007/s10734-013-9645-5

Dadvand, P., Niewenhuijsen, M. J., Esnaola, M., Forns, J., Basagaña, X., Alvarez-Pedrero, M., et al. (2015). Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.U.S.A. 112, 7937–7942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503402112

Dalton, A. M., Wareham, N., Griffin, S., and Jones, A. P. (2016). Neighbourhood greenspace is associated with a slower decline in physical activity in older adults: a prospective cohort study. SSM Popul. Health 2, 683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.09.006

Dettweiler, U., Becker, C., Auestad, B. H., Simon, P., and Kirsch, P. (2017). Stress in school. Some empirical hints on the circadian cortisol rhythm of children in outdoor and indoor classes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:475. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14050475

Dettweiler, U., Ünlü, A., Lauterbach, G., Becker, C., and Gschrey, B. (2015). Investigating the motivational behavior of pupils during outdoor science teaching within self-determination theory. Front. Psychol. 6:125. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00125

Doxey, J., Waliczek, T. M., and Zajicek, J. M. (2009). The impact of interior plants in university classrooms on student course performance and on student perceptions of the course and instructor. Hortic. Sci. 44, 384–391. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.44.2.384

Duckworth, A. L., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychol. Sci. 16, 939–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x

Ernst, J., and Stanek, D. (2006). The prairie science class: a model for re-visioning environmental education within the national wildlife refuge system. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 11, 255–265. doi: 10.1080/10871200600803010

Faber Taylor, A., Kuo, F., and Sullivan, W. (2002). Views of nature and self-discipline: evidence from inner city children. J. Environ. Psychol. 22, 49–63. doi: 10.1006/jevp.2001.0241

Faber Taylor, A., and Kuo, F. E. (2009). Children with attention deficits concentrate better after walk in the park. J. Atten. Disord. 12, 402–409. doi: 10.1177/1087054708323000

Fägerstam, E., and Blom, J. (2012). Learning biology and mathematics outdoors: effects and attitudes in a Swedish high school context. J. Advent. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 13, 56–75. doi: 10.1080/14729679.2011.647432

Flouri, E., Midouhas, E., and Joshi, H. (2014). The role of urban neighbourhood green space in children’s emotional and behavioural resilience. J. Environ. Psychol. 40, 179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.06.007

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. PNAS 111, 8410–8415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Fremery, C., and Bogner, F. X. (2014). Cognitive learning in authentic environments in relation to green attitude preferences. Stud. Educ. Eval. 44, 9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2014.11.002

Gibson, J. L., Cornell, M., and Gill, T. (2017). A systematic review of research into the impact of loose parts play on children’s cognitive, social and emotional development. School Ment. Health 9, 295–309. doi: 10.1007/s12310-017-9220-9

Granger, E. M., Bevis, T. H., Saka, Y., Southerland, S. A., Sampson, V., and Tate, R. L. (2012). The efficacy of student-centered instruction in supporting science learning. Science 338, 105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1223709

Grannis, J. C. (1992). Students’ stress, distress, and achievement in an urban intermediate school. J. Early Adolesc. 12, 4–27. doi: 10.1177/0272431692012001001

Gray, C., Gibbons, R., Larouche, R., Sandseter, E. B., Bienenstock, A., Brussoni, M., et al. (2015). What is the relationship between outdoor time and physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and physical fitness in children? A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 6455–6474. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606455

Hartig, T., Mang, M., and Evans, G. W. (1991). Restorative effects of natural environmental experiences. Environ. Behav. 23, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/0013916591231001

Harun, M. T., and Salamuddin, N. (2014). Promoting social skills through outdoor education and assessing its effects. Asian Soc. Sci. 10, 71–78. doi: 10.5539/ass.v10n5p71

Hill, A. B. (1965). The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proc. R. Soc. Med. 58, 295–300.

Ho, N. F., Zhou, J., Fung, D. S. S., Kua, P. H. J., and Huang, Y. X. (2017). Equine-assisted learning in youths at-risk for school or social failure. Cogent Educ. 4:1334430. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2017.1334430

Hobbs, L. K. (2015). Play-based science learning activities: engaging adults and children with informal science learning for preschoolers. Sci. Commun. 37, 405–414. doi: 10.1177/1075547015574017

Jostad, J., Paisley, K., and Gookin, J. (2012). Wilderness-based semester learning: understanding the NOLS experience. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 4, 16–26. doi: 10.7768/1948-5123.1115

Kochanowski, L., and Carr, V. (2014). Nature playscapes as contexts for fostering self-determination. Chil. Youth Environ. 24, 146–167. doi: 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.24.2.0146

Kontra, C., Lyons, D. J., Fischer, S. M., and Beilock, S. L. (2015). Physical experience enhances learning. Psychol. Sci. 26, 737–749. doi: 10.1177/0956797615569355

Kuo, F. E. (2001). Coping with poverty: impacts of environment and attention in the inner city. Environ. Behav. 33, 5–34. doi: 10.1177/00139160121972846

Kuo, F. E., and Faber Taylor, A. (2004). A potential natural treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a national study. Am. J. Public Health 94, 1580–1586. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.9.1580

Kuo, M. (2015). How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Supplemental material. Front. Psychol. 6:1093. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01093

Kuo, M., Browning, M. H. E. M., and Penner, M. L. (2018a). Do lessons in nature boost subsequent classroom engagement? Refueling students in flight. Front. Psychol. 8:2253. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02253

Kuo, M., Browning, M. H. E. M., Sachdeva, S., Westphal, L., and Lee, K. (2018b). Might school performance grow on trees? Examining the link between “greenness” and academic achievement in urban, high-poverty schools. Front. Psychol. 9:1669. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01669

Lachowitz, K., and Jones, A. P. (2011). Greenspace and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 12, e183–e189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00827.x

Lekies, K. S., Lost, G., and Rode, J. (2015). Urban youth’s experiences of nature: implications for outdoor adventure education. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 9, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2015.03.002

Leppink, E. W., Odlaug, B. L., Lust, K., Christenson, G., and Grant, J. E. (2016). The young and the stressed: stress, impulse control, and health in college students. J. Nervous Ment. Disord. 204, 931–938. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000586

Li, D., and Sullivan, W. C. (2016). Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue. Landsc. Urban Plan. 148, 149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.12.015

MacNaughton, P., Eitland, E., Kloog, I., Schwartz, J., and Allen, J. (2017). Impact of particulate matter exposure and surrounding “greenness” on chronic absenteeism in Massachusetts public schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:E207. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020207

Mantzicopoulos, P. Y., and Morrison, D. (1994). A comparison of boys and girls with attention problems: kindergarten through second grade. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 64, 522–533. doi: 10.1037/h0079560

Mårtensson, F., Boldemann, C., Soderstrom, M., Blennow, M., Englund, J.-E., and Grahn, P. (2009). Outdoor environmental assessment of attention promoting settings for preschool children. Health Place 15, 1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.07.002

Matsuoka, R. H. (2010). Student performance and high school landscapes: examining the links. Landsc. Urban Plan. 97, 273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.06.011

Maynard, T., Waters, J., and Clement, C. (2013). Child-initiated learning, the outdoor environment and the “underachieving” child. Early Years 33, 212–225. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2013.771152

McCormick, M. P., Cappella, E., O’Conner, E. E., and McClowry, S. G. (2015). Social-emotional learning and academic achievement: using causal methods to explore classroom-level mechanisms. AERA Open 1, 1–26. doi: 10.1177/2332858415603959

McCree, M., Cutting, R., and Sherwin, D. (2018). The hare and the tortoise go to forest school: taking the scenic route to academic attainment via emotional wellbeing outdoors. Early Child Dev. Care 188, 980–996. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2018.1446430

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., and Peake, P. (1988). The nature of adolescent competencies predicted by preschool delay of gratification. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 687–696. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.4.687

National Research Council. (2012). Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nedovic, S., and Morrissey, A. (2013). Calm, active and focused: children’s responses to an organic outdoor learning environment. Learn. Environ. Res. 16, 281–295. doi: 10.1007/s10984-013-9127-9

Nicholson, S. (1972). The theory of loose parts, an important principle for design methodology. Stud. Des. Educ. Craft Technol. 4, 5–14.

Niemiec, C. P., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory Res. Educ. 7, 133–144. doi: 10.1177/1477878509104318

O’Haire, M. E., Mckenzie, S. J., McCune, S., and Slaughter, V. (2013). Effects of animal-assisted activities with guinea pigs in the primary school classroom. Anthrozoos 26, 455–458. doi: 10.2752/175303713X13697429463835

Otto, S., and Pensini, P. (2017). Nature-based environmental education of children: environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Glob. Environ. Change 47, 88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.09.009

Pagels, P., Raustorp, A., Ponce De Leon, A., Mårtensson, F., Kylin, M., and Boldemann, C. (2014). A repeated measurement study investigating the impact of school outdoor environment upon physical activity across ages and seasons in Swedish second, fifth and eighth graders. Biomed Central Public Health 14:803. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-803

Patrick, H., Ryan, A. M., and Kaplan, A. (2007). Early adolescents’ perceptions of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 83–98. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.83

Reardon, S. F., Kalogrides, D., and Shores, K. (2017). The Geography of Racial/Ethnic Test Score Gaps (CEPA Working Paper No.16-10). Available at: Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis: http://cepa.stanford.edu/wp16-10

Richmond, D., Sibthorp, J., Gookin, J., Annorella, S., and Ferri, S. (2017). Complementing classroom learning through outdoor adventure education: out-of-school-time experiences that make a difference. J. Advent. Educ. Outdoor Learn. 18, 1–17.

Rowe, K. J., and Rowe, K. S. (1992). The relationship between inattentiveness in the classroom and reading achievement: part B: an explanatory study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 31, 357–368. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00026

Ruiz-Gallardo, J., Verde, A., and Valdes, A. (2013). Garden-based learning: an experience with “at risk” secondary education students. J. Environ. Educ. 44, 252–270. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2013.786669

Rutter, M. (2000). “School effects on pupil progress: research findings and policy implications,” in Psychology of Education: Major Themes, Vol. 1, eds P. K. Smith and A. D. Pellegrini (London: Falmer Press), 3–150.

Sahoo, S. K., and Senapati, A. (2014). Effect of sensory diet through outdoor play on functional behaviour in children with ADHD. Indian J. Occup. Ther.46, 49–54.

Santana, C. C. A., Azevedo, L. B., Cattuzzo, M. T., Hill, J. O., Andrade, L. P., and Prado, W. L. (2017). Physical fitness and academic performance in youth: a systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 27, 579–603. doi: 10.1111/sms.12773

Schutte, A. R., Torquati, J. C., and Beattie, H. L. (2015). Impact of urban nature on executive functioning in early and middle childhood. Environ. Behav. 49, 3–30. doi: 10.1177/0013916515603095

Scott, G., and Colquhoun, D. (2013). Changing spaces, changing relationships: the positive impact of learning out of doors. Aust. J. Outdoor Educ. 17, 47–53. doi: 10.1007/BF03400955

Sivarajah, S., Smith, S. M., and Thomas, S. C. (2018). Tree cover and species composition effects on academic performance of primary school students. PLoS One 13:e0193254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193254

Skinner, E. A., and Chi, U. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and engagement as “active ingredients” in garden-based education: examining models and measures derived from self-determination theory. J. Environ. Educ. 43, 16–36. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2011.596856

Studente, S., Seppala, N., and Sadowska, N. (2016). Facilitating creative thinking in the classroom: investigating the effects of plants and the colour green on visual and verbal creativity. Think. Skills Creat. 19, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2015.09.001

Swank, J. M., Cheung, C., Prikhidko, A., and Su, Y.-W. (2017). Nature-based child-centered play therapy and behavioral concerns: a single-case design. Int. J. Play Ther. 26, 47–57. doi: 10.1037/pla0000031

Takayama, N., Korpela, K., Lee, J., Morikawa, T., Tsunetsugu, Y., Park, B. J., et al. (2014). Emotional, restorative, and vitalizing effects of forest and urban environments at four sites in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 7207–7230. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110707207

Taylor, A. F., Wiley, A., Kuo, F. E., and Sullivan, W. C. (1998). Growing up in the inner city: green spaces as places to grow. Environ. Behav. 30, 3–27. doi: 10.1177/0013916598301001

Taylor, G., Jungert, T., Mageau, G. A., Schattke, K., Dedic, H., Rosenfield, S., et al. (2014). A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: the unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 39, 342–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.08.002

Truong, S., Gray, T., and Ward, K. (2016). “Sowing and growing” life skills through garden-based learning to re-engage disengaged youth. Learn. Landsc. 10, 361–385.

Ulset, V., Vitaro, F., Brendgren, M., Bekkus, M., and Borge, A. I. H. (2017). Time spent outdoors during preschool: links with children’s cognitive and behavioral development. J. Environ. Psychol. 52, 69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.05.007

van den Berg, A. E., and van den Berg, C. G. (2011). A comparison of children with ADHD in a natural and built setting. Child Care Health Dev. 37, 430–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01172.x

Warber, S. L., DeHurdy, A. A., Bialko, M. F., Marselle, M. R., and Irvine, K. N. (2015). Addressing “nature-deficit disorder”: a mixed methods pilot study of young adults attending a wilderness camp. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 1–13. doi: 10.1155/2015/651827

Weinstein, N., Przybylski, A. K., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Can nature make us more caring? Effects of immersion in nature on intrinsic aspirations and generosity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 35, 1315–1329. doi: 10.1177/0146167209341649

Wells, N. M., and Evans, G. W. (2003). Nearby nature: a buffer of life stress among rural children. Environ. Behav. 25:311. doi: 10.1177/0013916503035003001

Wells, N. M., Myers, B. M., Todd, L. E., Barale, K., Gaolach, B., Ferenz, G., et al. (2015). The effects of school gardens on children’s science knowledge: a randomized controlled trial of low-income elementary schools. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 37, 2858–2878. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2015.1112048

Wessler, S. L. (2003). Rebuilding classroom relationships – It’s hard to learn when you’re scared. Educ. Leadersh. 61, 40–43.

White, R. (2012). A sociocultural investigation of the efficacy of outdoor education to improve learning engagement. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 17, 13–23. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2012.652422

Wiens, V., Kyngäs, H., and Pölkki, T. (2016). The meaning of seasonal changes, nature, and animals for adolescent girls’ wellbeing in northern Finland. A qualitative descriptive study. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being 11:30160. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.30160

Keywords: literature review, green space, instruction, teaching, environmental education, nature-based learning, green schoolyard

Citation: Kuo M, Barnes M and Jordan C (2019) Do Experiences With Nature Promote Learning? Converging Evidence of a Cause-and-Effect Relationship. Front. Psychol. 10:305. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00305

Received: 06 September 2018; Accepted: 31 January 2019;

Published: 19 February 2019.

Edited by:

Donald William Hine, University of New England, AustraliaReviewed by:

Tristan Leslie Snell, Monash University, AustraliaCopyright © 2019 Kuo, Barnes and Jordan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ming Kuo, ZmVrdW9AaWxsaW5vaXMuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.