- 1Frontier Research Institute for Interdisciplinary Sciences, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan

- 2Behavioral Medicine, Graduated School of Medicine, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan

- 3Psychosomatic Medicine, Tohoku University Hospital, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan

The personality construct alexithymia is characterized by the difficulty in identifying and describing feelings with an externally oriented thinking pattern and a limited imaginative capacity (Nemiah et al., 1976). Alexithymia was first described as a specific cognitive and affective style of patients with classic psychosomatic diseases who showed little insight into their emotions and failed to respond to dynamic psychotherapy (Sifneos, 1967). Studies have found that alexithymia contributes to various medical conditions, including gastrointestinal diseases, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, chronic pain, renal failure, eating disorders, panic disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorders (Taylor et al., 1997). Alexithymia has been recognized as a risk factor for various physical and mental health problems; however, the mechanism that links alexithymia with these physical symptoms remains unclear.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are one of the conditions associated with alexithymia that has a high prevalence (Porcelli and Todarello, 2007). FGIDs are characterized by chronically recurring gastrointestinal symptoms in the absence of structural or biochemical abnormalities (Drossman, 2016). FGIDs are defined as disorders of the gut-brain interaction, which is a complex interaction that may be dysregulated by microbial dysbiosis within the gut, altered mucosal immune function, altered gut signaling (visceral hypersensitivity), and central nervous system modulation of gut signaling and motor function (Drossman and Hasler, 2016). FGIDs have been studied from a biopsychosocial perspective and shown that psychological and social factors have an impact on FGIDs (Van Oudenhove et al., 2016). Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional dyspepsia (FD) are the most widely recognized FGIDs with a prevalence of 11.2% (Lovell and Ford, 2012) and 10–30% (Mahadeva and Goh, 2006) worldwide, respectively.

To identify the association between alexithymia and FGIDs, we searched the relevant papers on PubMed from 1985 until September 2017 for full-text articles with a combination of “alexithymia” and “functional gastrointestinal disorders,” “irritable bowel syndrome,” “functional dyspepsia,” or “gastrointestinal” in the title of abstract. The first version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale was published in 1985 (Taylor et al., 1985).

Alexithymia in FGIDs

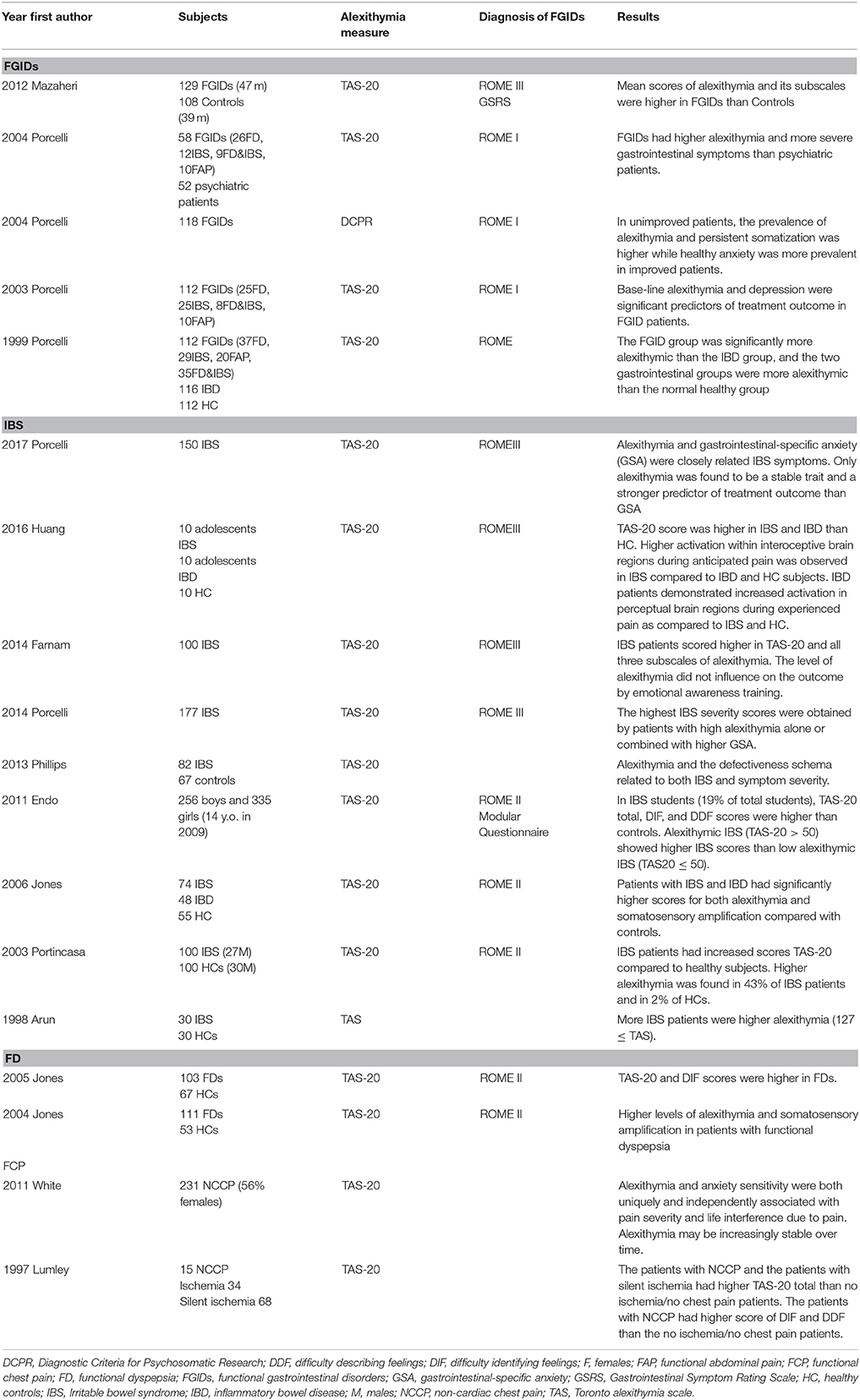

The studies of alexithymia in FGIDs are summarized in Table 1. A high prevalence of alexithymia has been reported in patients with FGIDs (Porcelli et al., 1999, 2003, 2004b; Mazaheri et al., 2012). Alexithymia was a negative predictor of treatment outcome (failure to improve) in FGIDs (Porcelli et al., 2003, 2004b), while health anxiety (hypochondria) predicted improvement (Porcelli et al., 2004b). Relative to depression, alexithymia was the stronger predictor for poor outcome (Porcelli et al., 2003). In a comparison between FGID patients with comorbid psychopathology and psychiatric outpatients with comorbid FGIDs, gastrointestinal symptoms were not significantly different between groups, but the FGIDs patients with psychopathology were more alexithymic and visited a gastroenterologist (Porcelli et al., 2004a). Alexithymia may contribute to the onset or maintenance of FGIDs independent of psychiatric disorders such as anxiety or depression, and illness behavior to seek medical help.

In patients with IBS, the prevalence of alexithymia or alexithymia level was high (Arun, 1998; Jones et al., 2006; Endo et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2013; Farnam et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2016) and IBS severity was positively associated with alexithymia (Endo et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2013; Porcelli et al., 2014). Furthermore, alexithymia and gastrointestinal-specific anxiety (GAS) were closely related to IBS symptoms (Porcelli et al., 2014, 2017), and the highest IBS severity was associated with alexithymia alone (Porcelli et al., 2014); only alexithymia was found to be a stable trait and a stronger predictor of treatment outcome of IBS (Porcelli et al., 2017). In addition to alexithymia, the same study found that somatosensory amplification, which refers to the tendency to experience somatic sensation as intense, was also higher in patients with IBS (Jones et al., 2006). In one randomized clinical trial to evaluate the therapeutic effect of emotional awareness training, alexithymia did not correlate with the overall outcome of pain severity or pain frequency (Farnam et al., 2014). Thus, alexithymia may be a more reliable trait than GAS and is associated with the severity of IBS.

In two functional dyspepsia studies from the same group, a high level of alexithymia was found in patients with FD (Jones et al., 2004, 2005). Level of somatoform amplification was also higher in patients with FD than in controls, but there was no correlation between somatosensory amplification and alexithymia (Jones et al., 2004).

The alexithymia score was high (Lumley et al., 1996) in patients with non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP), which is now categorized as functional chest pain as part of esophageal disorders of FGIDs (Drossman, 2016), and alexithymia and anxiety sensitivity were both uniquely associated with pain severity (White et al., 2011).

Alexithymia in Other Gastrointestinal Conditions

Inflammatory bowel disorders (IBD) are classic psychosomatic diseases (Sifneos, 1967; Taylor et al., 1981), and several studies have demonstrated that patients with IBD have high alexithymia (Porcelli et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2016). In these cases, alexithymia was associated with a poor quality of life (Mazaheri et al., 2012). One study reported that the FGID group was significantly more alexithymic than the IBD group (Porcelli et al., 1999), while another study found that patients with IBS and IBD did not differ from one another in terms of alexithymia severity (Jones et al., 2006). Alexithymia levels were related to the abdominal symptoms, but not with upper endoscopy findings (van Kerkhoven et al., 2006). On the other hand, a previous study demonstrated that alexithymia was higher in the peptic ulcer group than in the erosive gastritis group (Fukunishi et al., 1997), and both adenoma and adenocarcinoma patients had higher alexithymia scores than controls (Lauriola et al., 2011). Interestingly, in a 3-year prospective study with 60 colorectal cancer patients who underwent elective cholecystectomy, the high alexithymia group showed a significantly higher health related quality of life than did the lower alexithymia group during the postoperative period (Ripetti et al., 2008). Alexithymia predicted better outcomes of postoperative psychosocial adjustment several years after pelvic pouch surgery for ulcerative colitis (Weinryb et al., 2003). These studies indicate that alexithymia might be advantageous for psychosocial adaptation after surgery.

Alexithymia Measurement

Most of studies which listed in Table 1 used 20-itemToronto alexithymia scale (TAS-20) (Bagby et al., 1994a,b). The TAS-20 is a self-reported measurement and has been used as a reliable, validated, and common metric for measuring alexithymia in a broad variety of studies (Lumley et al., 2007). On the other hand, there is an argument that TAS-20 tends to correlate with negative affect, such as anxiety and depression, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the influence of negative emotions from that of alexithymia on the clinical conditions (Subic-Wrana et al., 2005). The Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale (LEAS) is another self-report measurement and has been demonstrated no overlap with measures of negative effect (Lane and Schwartz, 1987; Subic-Wrana et al., 2005). Of note that TAS-20 and LEAS are not correlated well (Subic-Wrana et al., 2005). In addition, some researchers questioned whether self-report measures is appropriate to measure alexithymia and they recommend the use of multiple methods of measurement (Kooiman et al., 2002; Bagby et al., 2006). There has been various instruments developed such as observer-rated measures including the modified Beth Israel Hospital Psychosomatic Questionnaire (BIQ), the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire (BVAQ) (Morera et al., 2005), and the Toronto Structured Interview for Alexithymia (TSIA) (Caretti et al., 2011). Differences in the evaluation method of Alexithymia are fundamentally problematic in interpreting the influence of alexithymia on clinical conditions. We need a consensus on suitable assessment of alexithymia in accordance with various study designs, including epidemiologic, exploratory, and clinical researches.

Influence of Alexithymia on FGIDs

Alexithymia may contribute to an increased severity of FGID or a poor outcome independent of anxiety and depression from the epidemiological studies listed in Table 1. What is the possible mechanism and clinical implication of this association between alexithymia and FGID?

Enhanced perception of visceral stimuli called visceral hypersensitivity is one of the key features of IBS (Drossman and Hasler, 2016). One hypothesis is that alexithymia may enhance the visceral hypersensitivity in IBS. High alexithymia patients often have a tendency to amplify somatic sensations (Porcelli and Todarello, 2007) and sustain the physiological component of emotion response systems (Lumley et al., 2007). The data that support this theory, though, are inconsistent. A somatosensory amplification score (SSAS) was positively correlated with an alexithymia score in patients with somatoform disorder (Tominaga et al., 2014) or those with psychosomatic illness (Nakao et al., 2002), but not in patients with FD (Jones et al., 2004). Healthy subjects with alexithymia showed less sensitivity to a heartbeat detection test (Murphy et al., 2017) and pain from heat exposure (Pollatos et al., 2015), but were hyper sensitive to visceral pain induced by rectal distention (Kano et al., 2003). The insula, which corresponds to the visceral sensory cortex, in patients with alexithymia was strongly activated by visceral pain (Kano et al., 2003, 2015) or from watching pictures of others experiencing pain (Moriguchi et al., 2007). In contrast, the insula was activated less by imagining others' pain (Bird et al., 2010). In the chronic pain conditions, in which a high prevalence of alexithymia has been reported, the association between alexithymia and pain intensity is not always clear (Di Tella and Castelli, 2016). It has been suggested that not only sensory component of pain but also affective component of pain may contribute to the relationship between alexithymia and chronic pain conditions (Di Tella and Castelli, 2016). It is an important issue to be clarified that alexithymia is related to the visceral hypersensitivity. Amplifying visceral or somatic sensation has several aspects: subjective evaluation of physiological sensation such as level of pain or accuracy of heartbeat, subjective believe of their physical condition as measured by questionnaires on the sensory system, and cognitive process such as a mismatch between the actual image of somatic/visceral sensation represented in the brain and the subjective predicted state. The mismatch between actual physiological state and prediction has been hypothesized as one of the pathophysiology of IBS (Mayer, 2011). In addition, the influence of alexithymia on visceral sensation is different between healthy subjects and pathological conditions. It is required to investigate how alexithymia contribute to these aspects over healthy and pathological conditions in a large sample population.

Another possible mechanism may be the influence of alexithymia on physiological stress system including autonomic nervous system (ANS) and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. These systems are main mediators of brain-gut interaction and alteration of these systems has been reported in FGIDs (Chang, 2011; Drossman, 2016; Kano et al., 2017). Subjects with high alexithymia showed lower skin conductance reactivity at baseline (Gaigg et al., 2016) and during emotional imaginary (Constantinou et al., 2014; Peasley-Miklus et al., 2016) and electrical stimulation (Starita et al., 2016), that indicates physiological hypo-arousal and ANS dysfunction in alexithymia. Cortisol response was increased during anticipation of stress associated with alexithymia (de Timary et al., 2008; Hua et al., 2014). Healthy individual with higher TAS-20 subscale, difficulty of identifying feelings score demonstrated increased adrenocorticotropic hormone response to corolectal distention (Kano et al., 2007). There may be direct association between alexithymia and these stress response system or possibly alteration of visceral sensation is a prerequisite of the change of stress response system.

In conclusion, alexithymia may contribute to an increased severity of FGID or a poor outcome measured by TAS-20. The empirical data may indicate that the association between FGIDs and alexithymia may not be explained simply by “somatosensory amplification,” but biased interpretation of their symptoms not based on appropriate bodily sensation. The physiological component of the emotional or stress response system may be altered; however, the direction of causation between these alterations and the alexithymic cognitive and affective style is not clear. The studies on the association between alexithymia and physiological aspect of FGID has been sparse. Future studies are required to make a consensus of measurement of alexithymia, and elucidate the physiological mechanism of link between alexithymia and FGID.

Author Contributions

MK: Drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript; YE: Critical revision of the manuscript; SF: Critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science (for MK, Grant No. 26460898).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bagby, R. M., Paker, J. D., and Talor, G. J. (1994a). The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia scale I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 38, 33–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90006-X

Bagby, R. M., Talor, G. J., and Paker, J. D. (1994b). The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia Scale II Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. J. Psychosom. Res. 38, 23–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1

Bagby, R. M., Taylor, G. J., Parker, J. D., and Dickens, S. E. (2006). The development of the Toronto structured interview for alexithymia: item selection, factor structure, reliability and concurrent validity. Psychother. Psychosom. 75, 25–39. doi: 10.1159/000089224

Bird, G., Silani, G., Brindley, R., White, S., Frith, U., and Singer, T. (2010). Empathic brain responses in insula are modulated by levels of alexithymia but not autism. Brain 133(Pt 5), 1515–1525. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq060

Caretti, V., Porcelli, P., Solano, L., Schimmenti, A., Bagby, R. M., and Taylor, G. J. (2011). Reliability and validity of the Toronto structured interview for alexithymia in a mixed clinical and nonclinical sample from Italy. Psychiatry Res. 187, 432–436. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.02.015

Chang, L. (2011). The role of stress on physiological responses and clinical symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 140, 761–765. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.032

Constantinou, E., Panayiotou, G., and Theodorou, M. (2014). Emotion processing deficits in alexithymia and response to a depth of processing intervention. Biol. Psychol. 103, 212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.09.011

de Timary, P., Roy, E., Luminet, O., Fillée, C., and Mikolajczak, M. (2008). Relationship between alexithymia, alexithymia factors and salivary cortisol in men exposed to a social stress test. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33, 1160–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.06.005

Di Tella, M., and Castelli, L. (2016). Alexithymia in chronic pain disorders. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 18:41. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0592-x

Drossman, D. A. (2016). Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 150, 1262–1279. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032

Drossman, D. A., and Hasler, W. L. (2016). Rome IV-functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology 150, 1257–1261. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035

Endo, Y., Shoji, T., Fukudo, S., Machida, T., Machida, T., Noda, S., et al. (2011). The features of adolescent irritable bowel syndrome in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26(Suppl. 3), 106–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06637.x

Farnam, A., Somi, M. H., Farhang, S., Mahdavi, N., and Ali Besharat, M. (2014). The therapeutic effect of adding emotional awareness training to standard medical treatment for irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 20, 3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000442934.38704.3a

Fukunishi, S., Kikuchi, M., Kaji, N., and Yamasaki, K. (1997). Can scores on alexithymia distinguish patients with peptic ulcer and erosive gastritis? Psychol. Rep. 80(3 Pt 1), 995–1004. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.3.995

Gaigg, S. B., Cornell, A. S., and Bird, G. (2016). The psychophysiological mechanisms of alexithymia in autism spectrum disorder. Autism 22, 227–231. doi: 10.1177/1362361316667062

Hua, J., Le Scanff, C., Larue, J., Jose, F., Martin, J. C., Devillers, L., et al. (2014). Global stress response during a social stress test: impact of alexithymia and its subfactors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 50, 53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.08.003

Huang, J. S., Terrones, L., Simmons, A. N., Kaye, W., and Strigo, I. (2016). A pilot study of fMRI responses to somatic pain stimuli in youth with functional and inflammatory gastrointestinal disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 63, 500–507. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001390

Jones, M. P., Roth, L. M., and Crowell, M. D. (2005). Symptom reporting by functional dyspeptics during the water load test. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100, 1334–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40802.x

Jones, M. P., Schettler, A., Olden, K., and Crowell, M. D. (2004). Alexithymia and somatosensory amplification in functional dyspepsia. Psychosomatics 45, 508–516. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.6.508

Jones, M. P., Wessinger, S., and Crowell, M. D. (2006). Coping strategies and interpersonal support in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4, 474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.012

Kano, M., Fukudo, S., Gyoba, J., Kamachi, M., Tagawa, M., Mochizuki, H., et al. (2003). Specific brain processing of facial expressions in people with alexithymia: an H2 15O-PET study. Brain 126(Pt 6), 1474–1484. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg131

Kano, M., Hamaguchi, T., Itoh, M., Yanai, K., and Fukudo, S. (2007). Correlation between alexithymia and hypersensitivity to visceral stimulation in human. Pain 132, 252–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.032

Kano, M., Muratsubaki, T., Morishita, J., Yagihashi, M., Ly, H. G., Dupont, P., et al. (2015). Influence of alexithymia on brain activity during rectal distention in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Psychother. Psychosomat. 84, 37–37.

Kano, M., Muratsubaki, T., Van Oudenhove, L., Morishita, J., Yoshizawa, M., Kohno, K., et al. (2017). Altered brain and gut responses to corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Sci. Rep. 7:12425. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09635-x

Kooiman, C. G., Spinhoven, P., and Trijsburg, R. W. (2002). The assessment of alexithymia: a critical review of the literature and a psychometric study of the Toronto alexithymia scale-20. J. Psychosom. Res. 53, 1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00348-3

Lane, R. D., and Schwartz, G. E. (1987). Levels of emotional awareness - a cognitive developmental theory and its application to psychopathology. Am. J. Psychiatry 144, 133–143.

Lauriola, M., Panno, A., Tomai, M., Ricciardi, V., and Potenza, A. E. (2011). Is alexithymia related to colon cancer? A survey of patients undergoing a screening colonoscopy examination. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 18, 410–415. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9267-y

Lovell, R. M., and Ford, A. C. (2012). Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 712.e4–721.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029

Lumley, M. A., Neely, L. C., and Burger, A. J. (2007). The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: implications for understanding and treating health problems. J. Pers. Assess. 89, 230–246. doi: 10.1080/00223890701629698

Lumley, M. A., Ovies, T., Stettner, L., Wehmer, F., and Lakey, B. (1996). Alexithymia, social support and health problems. J. Psychosom. Res. 41, 519–530. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00227-9

Mahadeva, S., and Goh, K. L. (2006). Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 2661–2666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2661

Mayer, E. A. (2011). Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut–brain communication. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 453–466. doi: 10.1038/nrn3071

Mazaheri, M., Afshar, H., Weinland, S., Mohammadi, N., and Adibi, P. (2012). Alexithymia and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (FGID). Med. Arch. 66:28. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2012.66.28-32

Morera, O. F., Culhane, S. E., Watson, P. J., and Skewes, M. C. (2005). Assessing the reliability and validity of the Bermond-Vorst alexithymia questionnaire among U.S. Anglo and U.S. Hispanic samples. J. Psychosom. Res. 58, 289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.001

Moriguchi, Y., Decety, J., Ohnishi, T., Maeda, M., Mori, T., Nemoto, K., et al. (2007). Empathy and judging other's pain: an fMRI study of alexithymia. Cereb. Cortex 17, 2223–2234. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl130

Murphy, J., Brewer, R., Catmur, C., and Bird, G. (2017). Interoception and psychopathology: a developmental neuroscience perspective. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 23, 45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2016.12.006

Nakao, M., Barsky, A. J., Kumano, H., and Kuboki, T. (2002). Relationship between somatosensory amplification and alexithymia in a Japanese psychosomatic clinic. Psychosomatics 43, 55–60. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.1.55

Nemiah, J. C., Freyberger, H., and Sifneos, P. E. (1976). Alexithymia: A View of the Psychosomatic Process. London: Butterworths.

Peasley-Miklus, C. E., Panayiotou, G., and Vrana, S. R. (2016). Alexithymia predicts arousal-based processing deficits and discordance between emotion response systems during emotional imagery. Emotion 16, 164–174. doi: 10.1037/emo0000086

Phillips, K., Wright, B. J., and Kent, S. (2013). Psychosocial predictors of irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis and symptom severity. J. Psychosom. Res. 75, 467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.08.002

Pollatos, O., Dietel, A., Gündel, H., and Duschek, S. (2015). Alexithymic trait, painful heat stimulation, and everyday pain experience. Front. Psychiatry 6:139. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00139

Porcelli, P., Affatati, V., Bellomo, A., De Carne, M., Todarello, O., and Taylor, G. J. (2004a). Alexithymia and psychopathology in patients with psychiatric and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychother. Psychosom. 73, 84–91. doi: 10.1159/000075539

Porcelli, P., De Carne, M., and Leandro, G. (2014). Alexithymia and gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Compr. Psychiatry 55, 1647–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.05.022

Porcelli, P., De Carne, M., and Leandro, G. (2017). The role of alexithymia and gastrointestinal-specific anxiety as predictors of treatment outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Compr. Psychiatry 73, 127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.11.010

Porcelli, P., De Carne, M., and Todarello, O. (2004b). Prediction of treatment outcome of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders by the diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research. Psychother. Psychosom. 73, 166–173. doi: 10.1159/000076454

Porcelli, P., Bagby R. M., Taylor, G. J., De Carne, M., Leandro, G., and Todarello, O. (2003). Alexithymia as predictor of treatment outcome in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom. Med. 65, 911–918. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000089064.13681.3B

Porcelli, P., Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., and De Carne, M. (1999). Alexithymia and functional gastrointestinal disorders. A comparison with inflammatory bowel disease. Psychother. Psychosom. 68, 263–269. doi: 10.1159/000012342

Porcelli, P., and Todarello, O. (2007). Psychological factors affecting functional gastrointestinal disorders. Adv. Psychosom. Med. 28, 34–56. doi: 10.1159/000106796

Ripetti, V., Ausania, F., Bruni, R., Campoli, G., and Coppola, R. (2008). Quality of life following colorectal cancer surgery: the role of alexithymia. Eur. Surg. Res. 41, 324–330. doi: 10.1159/000155898

Sifneos, P. E. (1967). Clinical observations on some patients suffering from a variety of psychosomatic diseases. Acta Med. Psychosomat. 7, 1–10.

Starita, F., Làdavas, E., and di Pellegrino, G. (2016). Reduced anticipation of negative emotional events in alexithymia. Sci. Rep. 6:27664. doi: 10.1038/srep27664

Subic-Wrana, C., Bruder, S., Thomas, W., Lane, R. D., and Köhle, K. (2005). Emotional awareness deficits in inpatients of a psychosomatic ward: a comparison of two different measures of alexithymia. Psychosom. Med. 67, 483–489. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000160461.19239.13

Taylor, G., Doody, K., and Newman, A. (1981). Alexithymic characteristics in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Can. J. Psychiatry 26, 470–474. doi: 10.1177/070674378102600706

Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., and Parker, J. D. A. (1997). Disorder of Affect Regulation: Alexithymia in Medical and Psychiatric Illness. Toronto, ON: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, G. J., Ryan, D., and Bagby, R. M. (1985). Toward the development of a new self-report alexithymia scale. Psychother. Psychosom. 44, 191–199. doi: 10.1159/000287912

Tominaga, T., Choi, H., Nagoshi, Y., Wada, Y., and Fukui, K. (2014). Relationship between alexithymia and coping strategies in patients with somatoform disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 10, 55–62. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S55956

van Kerkhoven, L. A., van Rossum, L. G., van Oijen, M. G., Tan, A. C., Witteman, E. M., Laheij, R. J., et al. (2006). Alexithymia is associated with gastrointestinal symptoms, but does not predict endoscopy outcome in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 40, 195–199. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200603000-00005

Van Oudenhove, L., Crowell, M. D., Drossman, D. A., Halpert, A. D., Keefer, L., Lackner, J. M., et al. (2016). Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 150, 1355–1367. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.027

Weinryb, R. M., Gustavsson, J. P., and Barber, J. P. (2003). Personality traits predicting long-term adjustment after surgery for ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Psychol. 59, 1015–1029. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10191

Keywords: alexithymia, functional gastrointestinal disorders, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, functional dyspepsia, somatoform amplification

Citation: Kano M, Endo Y and Fukudo S (2018) Association Between Alexithymia and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Front. Psychol. 9:599. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00599

Received: 10 November 2017; Accepted: 10 April 2018;

Published: 25 April 2018.

Edited by:

Valentina Tesio, Università degli Studi di Torino, ItalyReviewed by:

Harald Gündel, Universitätsklinikum Ulm, GermanyCopyright © 2018 Kano, Endo and Fukudo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michiko Kano, bWthbm9AbWVkLnRvaG9rdS5hYy5qcA==

Michiko Kano

Michiko Kano Yuka Endo

Yuka Endo Shin Fukudo2,3

Shin Fukudo2,3