- 1Central Texas Veterans Health Care System – Veterans Health Administration, VISN 17 Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans, Waco, TX, United States

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Dell Medical School of the University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

- 3Institute of Health and Society, University of Worcester, Worcester, United Kingdom

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is strongly associated with exposure to war related trauma in military and veteran populations. In growing recognition that PTSD may influence and be influenced by social support and family systems, research has begun to explore the effects that war related trauma and the ensuing PTSD may have on varied aspects of close relationship and family functioning. Far less research, however, has examined the influence of war-related PTSD on parent-child functioning in this population. This paper provides a timely review of emergent literature to examine the impacts that PTSD may have on parenting behaviors and children’s outcomes with a focus on studies of military and veterans of international conflicts since post-9/11. The review sheds light on the pathways through which PTSD may impact parent-child relationships, and proposes the cognitive-behavioral interpersonal theory of PTSD as a theoretical formulation and extends this to parenting/children. The review identifies the strengths and limitations in the extant research and proposes directions for future research and methodological practice to better capture the complex interplay of PTSD and parenting in military and veteran families.

Introduction

The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in samples of United States military service members and veterans who deployed to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has recently been estimated to be as high as 23% (Fulton et al., 2015). In growing recognition that PTSD may influence and be influenced by social support and family systems, research has begun to explore the effects that military-related PTSD may have on varied aspects of close relationship and family functioning (Vogt et al., 2016; Wagner et al., 2016). Understanding these associations is essential, as social and relationship functioning may have important implications for treatment and prevention of PTSD.

In the United States alone, estimates suggest 43% of current service members are parents to at least one dependent child (Department of Defense, 2014). Given the high rates of PTSD in those who deployed, these numbers highlight the need for improved understanding of parent-child functioning in military populations. A robust body of research has explored the effects of deployment on child adjustment (see Creech et al., 2014; Alfano et al., 2016 for reviews). Until recently, far less research had examined the influence of parental PTSD on parent-child functioning. Recent growth of studies in this area underscored the need for a new review of the literature.

Sample of Studies and Analysis

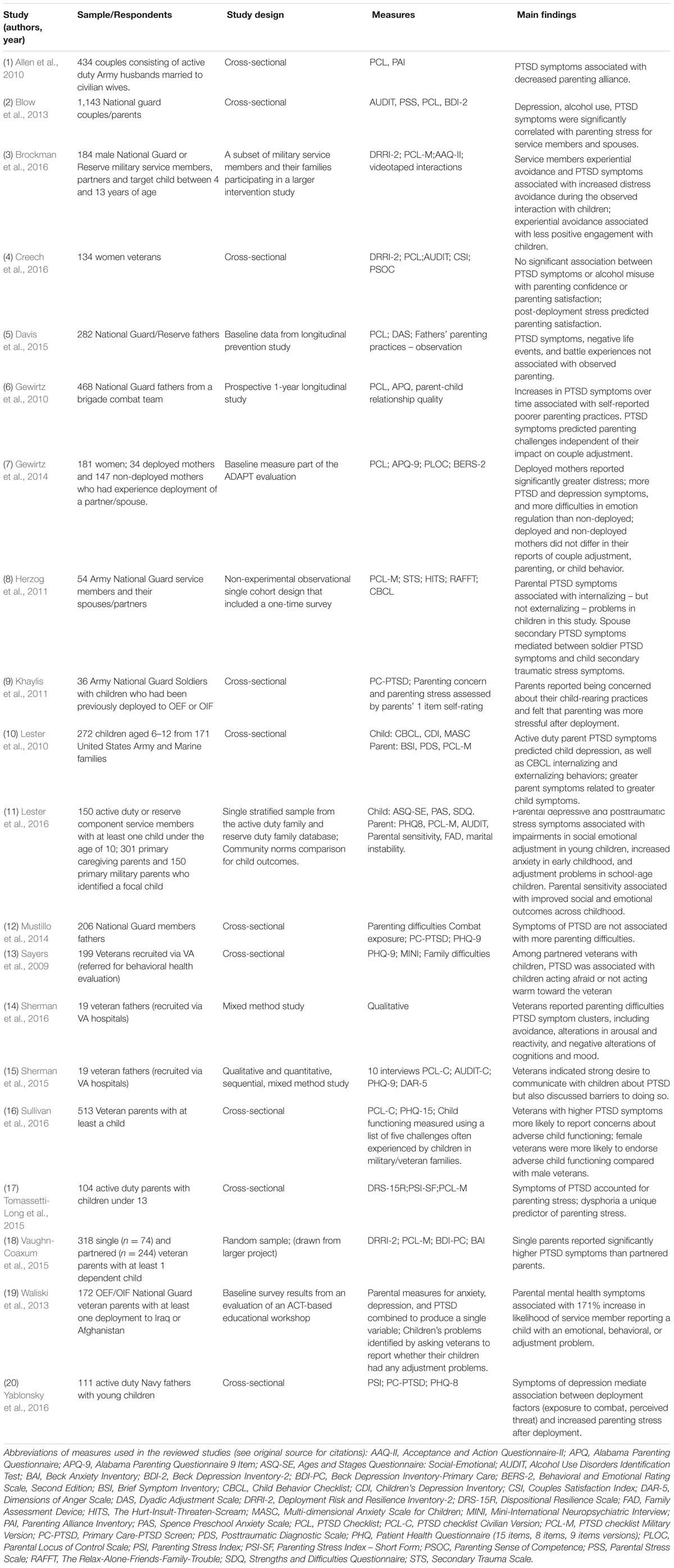

This review examined post-9/11 and cross-cultural research on the influence of military-related PTSD and common comorbidities on parenting, child outcomes, and parent-child functioning. We also extend the cognitive-behavioral interpersonal theory of PTSD (Monson et al., 2012) to parent-child functioning. Literature searches of PsycINFO, MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science from 2001 to 2016 were performed. Key words included: ‘military/soldier∗/arm∗/combat/veteran∗’ AND ‘Iraq/Afgha-nistan/OIF/OEF’ AND ‘parent∗/maternal/paternal’ AND ‘PTSD/posttraumatic stress’ AND (‘child∗’ AND ‘outcome/problem/disorder’). Hand-searches were conducted via the reference lists of selected papers. A total of 83 studies were retrieved and assessed according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) reported data on parenting and/or child outcomes of military personnel or veterans deployed to Iraq and/or Afghanistan, (2) included measures of military parent’s PTSD; (3) peer-reviewed and reported in English. A quality appraisal of the studies (on criteria including population, representativeness, sample size, validity of outcome measures and statistical power of results) was undertaken independently by the two authors and inclusion was determined by agreement. This systematic search identified 20 studies (summarized in Table 1). Although the aim was to identify research globally, all studies that satisfied the inclusion criteria were exclusively United States based. Given the heterogeneity of studies in terms of samples, design and outcome measures used (which precluded the use of meta-analysis) a narrative synthesis was employed as method of analysis.

Advancing Cognitive-Behavioral Interpersonal Theory to Parent-Child Functioning

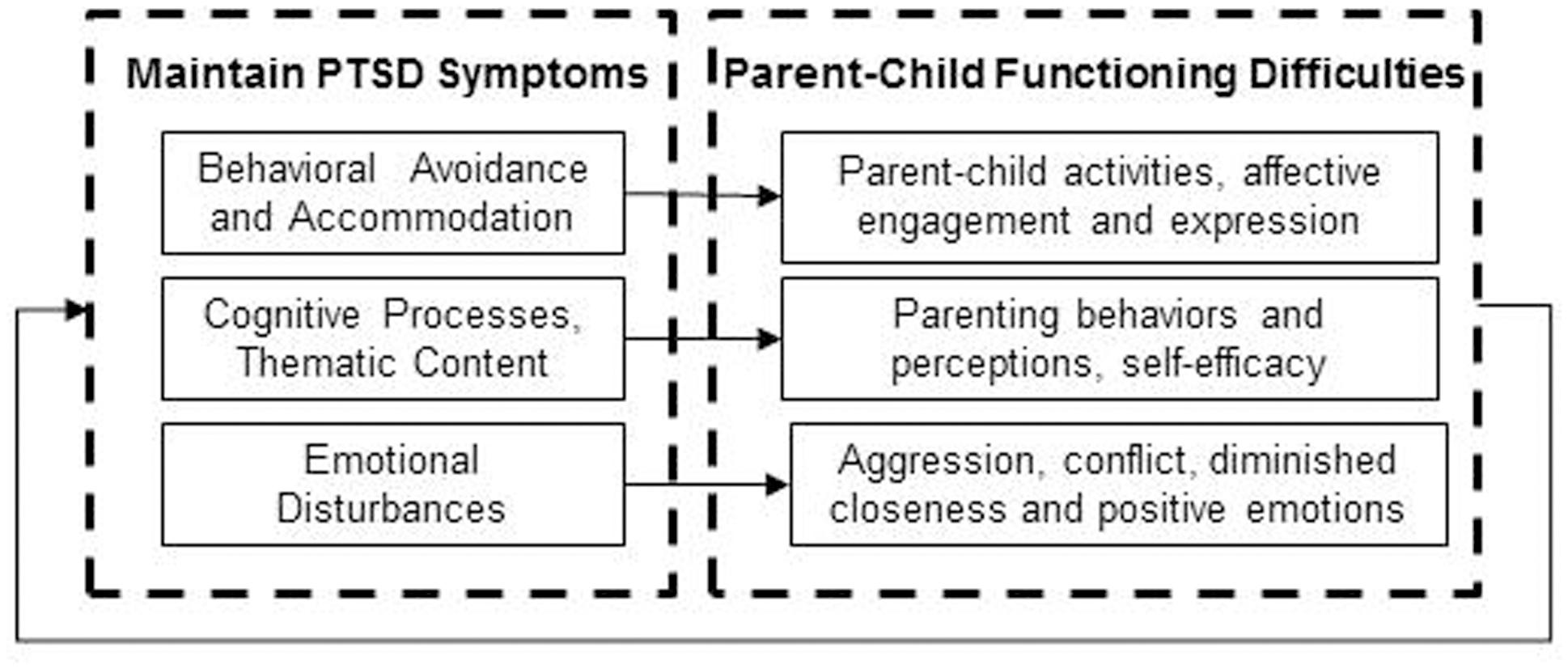

The cognitive-behavioral interpersonal theory of PTSD (C-BIT) emphasizes the roles of three processes that both maintain PTSD symptoms and negatively impact intimate relationship functioning: (1) behavioral avoidance and accommodation, (2) cognitive processes and thematic content, (3) emotional disturbances (Dekel and Monson, 2010; Monson et al., 2010). We are not aware of prior extensions of this theory to parent-child functioning, however, we argue that the processes implicated in the association between PTSD and intimate relationship functioning are applicable to parent-child functioning (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. The cognitive-behavioral interpersonal theory of PTSD applied to parent-child difficulties.

Within this model, behavioral avoidance and accommodation refer to the process through which PTSD avoidance symptoms are negatively reinforcing and thereby maintain trauma-related distress (e.g., Monson et al., 2012). The parent-child relationship may be adversely impacted if behavioral avoidance symptoms interfere with participating in parent-child activities or emotional numbing symptoms interfere with affective engagement and expression (e.g., Sherman et al., 2016). Supporting this view are several studies from Vietnam era samples implicating the avoidance symptoms of PTSD as being particularly deleterious to parenting (Ruscio et al., 2002; Samper et al., 2004). In turn, the family system, including children, may accommodate avoidance symptoms by facilitating avoidance behaviors, thereby further reinforcing this process and maintaining PTSD symptoms. For example, family members may modify their own activities so that one member may not encounter reminders that cause trauma-related distress (such as not attending a school function because a parent finds crowds distressing). Accommodation behaviors have only recently begun to be researched in intimate relationships (e.g., Fredman et al., 2014); further work is needed to examine accommodation in parent-child relationships.

Within the C-BIT model, cognitive processes and thematic content refer to rigid and maladaptive schemas about the world and past experiences and disruptions to core themes such as power, trust, control, and intimacy (Resick et al., 2014). Cognitive processes associated with PTSD such as attention bias toward threat and amplified attention to safety may influence parental perceptions of their child’s behaviors as more negative and enhance concerns about safety, and this is likely to influence parenting behaviors. Cognitive biases may also influence parental self-efficacy. For example, some veterans describe negative evaluations of themselves as parents, feelings of unworthiness as a parent, and alienation or detachment from their children (Sherman et al., 2016).

Emotional disturbances such as blunted positive emotions and increased anger, shame, guilt, and sadness are common to PTSD are thought to further impair family processes through disruptions to closeness, positive emotional experiences and emotional expression (Monson et al., 2012). For example, recent work has linked the dysphoria symptom cluster of PTSD to increased parenting stress in combat-exposed veterans (Tomassetti-Long et al., 2015). In their recent qualitative work, Sherman et al. (2016) noted that many veterans with PTSD spoke about the negative influence of emotional disturbances on their parenting. The influence of anger and aggression on parenting was another theme that emerged in Sherman’s study (2016), a finding that has been well-validated in two quantitative studies drawn from the United States National Comorbidity study and its replication. Specifically, parents with PTSD were more likely to report moderate and severe physical aggression with their children (Leen-Feldner et al., 2011), and the emotional numbing symptoms of PTSD were predictive of parent-child aggression (Lauterbach et al., 2007).

Influence of Parent-Child Functioning On PTSD

At its core, the C-BIT model is bidirectional, suggesting that while PTSD influences family functioning, family functioning also influences PTSD. Several recent studies of veterans seeking healthcare at United States Veterans Affairs facilities provide initial support for an influence of parent-child functioning on PTSD. A study of the records of over 100,000 veterans found those with dependent children were about 40% more likely to have a diagnosis of PTSD during their first year of VA use, compared to counterparts without dependent children (Janke-Stedronsky et al., 2016). In another study, having minor children living in the home was related to increased PTSD symptom severity (Jobe-Shields et al., 2015). In a sample of veterans who had recently deployed, Vaughn-Coaxum et al. (2015) found that compared to partnered parents, single parents reported significantly greater post-deployment symptoms of PTSD even when controlling for combat exposure. Collectively this work suggests parenting status may enhance risk for PTSD symptoms after combat trauma exposure, particularly in single parents. One explanation for the association between parenting status and increased PTSD symptoms may be related to concerns about the well-being of family members while in the warzone, and how such concern may amplify perceptions of threat (Vogt et al., 2011). In addition, higher levels of parent-child functioning problems are likely to amplify PTSD symptoms, particularly during times of stress.

Influence of PTSD on Parenting Outcomes Including Parenting Behaviors

Across samples of United States service members and veterans with recent deployments to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, symptoms of PTSD as well as depression have been implicated as predictors of parent-reported difficulties on a variety of indicators of parent-child functioning. For example, in samples comprised primarily of male National Guard/Reserve parents with recent deployments, PTSD symptoms were associated with concerns about child-rearing (Khaylis et al., 2011). In two other studies symptoms of depression but not PTSD were associated with perceived parenting difficulties (Mustillo et al., 2014) and increased parenting stress (Blow et al., 2013).

In a study of United States National Guard/Reserve fathers enrolled in a clinical trial to improve parenting after deployment, fathers, partners, and children were observed during a 5-min video interaction of a structured task (Brockman et al., 2016). Interactions were coded for the occurrence of positive engagement, withdrawal, avoidance and reactivity-coercion behaviors. At the univariate level, PTSD symptoms were associated with increased distress avoidance (fear, wariness, ignoring or low empathy in response to aversive behavior or affective distress of the child) during the observed interaction with children (Brockman et al., 2016). Mediational analyses indicated experiential avoidance (unwillingness or inability to remain in contact with negative thoughts, feelings or sensations) appeared to diminish the association between PTSD and observed parent-child interactions patterns and was associated with less positive engagement with children.

A study of 34 National Guard/Reserve mothers who had previously deployed (data drawn from the same clinical trial as above) reported higher PTSD symptoms and depression compared to 147 non-deployed mothers whose partners were deployed, however, there was no difference between the two groups on measures of parenting behaviors, parenting efficacy, or parent reported child functioning (Gewirtz et al., 2014). In another study examining United States veteran mothers randomly sampled from one geographic region, results indicated no association between PTSD symptoms or alcohol misuse with parenting satisfaction or confidence (Creech et al., 2016). Instead, parenting satisfaction was predicted by post-deployment stress exposure (number of life stressors after deployment such robbery or job loss). Results from both of these studies must be interpreted cautiously, however, due a small sample size of mothers who had previously deployed.

In a sample of active duty United States Army fathers (drawn from a study of the effectiveness of a marriage education workshop), baseline PTSD symptoms were associated with decreased parenting alliance, a measure of cooperation and communication between parents (Allen et al., 2010). In a random sample comprised primarily of active duty service members, Tomassetti-Long et al. (2015) reported that the dysphoria component of PTSD was a unique predictor of parental stress in recently deployed fathers, though it should be noted that parenting stress in the sample overall was very low. This study also found the personality variable hardiness to be protective against parenting and posttraumatic stress. In a sample of active duty United States Navy fathers, symptoms of depression but not PTSD appeared to mediate an association between several deployment factors (exposure to combat, perceived threat) and increased parenting stress after deployment (Yablonsky et al., 2016).

In a sample of United States Veteran parents referred for evaluation, PTSD symptoms and the psychomotor symptoms of depression were associated with increased likelihood of reporting “children acting afraid or not being warm” (Sayers et al., 2009). Within another treatment seeking group of Veterans, Sherman and colleagues examined veteran perspectives on the influence of PTSD on parenting. Interviews focused on communication with children about PTSD among a sample of 19 veteran parents who were diagnosed with PTSD. Veterans commented on barriers to talking with children about PTSD as well as motivations to do so, however, many also indicated such communication was challenging (Sherman et al., 2015). Results from a second study described themes related to the influence of specific PTSD symptom clusters on aspects of parenting (Sherman et al., 2016). Avoidance symptoms were described as interfering with participating in children’s activities and alterations in cognitions and mood were described as influencing self-worth as a parent, family engagement, and attachment. Importantly, some veterans described the influence of irritability and anger on their parenting behavior, with some describing incidents of aggression or aggressive urges toward children.

We were only able to find two studies in recent samples of veteran and military families that examined observed or self-reported parenting behaviors. Increases in PTSD symptoms 1 year after returning from a combat deployment to Iraq were associated with self-report of poorer parenting behaviors (less positive parenting, more inconsistent discipline, and less supervision) (Gewirtz et al., 2010). However, in a second study using observed parenting behaviors, there was no association between post-deployment PTSD symptoms with parenting behaviors (Davis et al., 2015). The authors suggested the difference in findings may be that observed parenting behaviors are only impaired at higher levels of PTSD symptoms and noted that a relatively small percentage of both samples exceeded cut-offs for probable PTSD.

Influence of PTSD on Child Outcomes

Lester et al. (2010) examined behavioral and emotional problems of 272 children aged 6–12 from 171 United States Army and Marine families with a parent currently or recently deployed. Although children’s scores on depression and externalizing/internalizing (according to both parent and self-reports) were comparable to normative data; active duty parent PTSD symptoms predicted child depression, as well as internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Lester et al. (2016) also examined the relationship between parental PTSD and children’s outcomes in a national probability sample comprising 150 active duty or reserve component service members with at least one child under the age of 10. The findings highlighted a small but significant association between military parental PTSD severity and preschool child separation anxiety, as well as increased emotional and behavioral problems in school-aged children.

In another study exploring secondary traumatic stress symptoms in spouses and children of 54 National Guard families, Herzog et al. (2011) found a moderate relationship between PTSD symptoms in service members and secondary trauma symptoms in children. Children’s internalizing but not externalizing problems were symptomatic of secondary trauma stress in children, and were mediated by the spouse’s secondary trauma stress symptoms. However, only seven families were identified with high levels of military-related PTSD.

Several studies examined parent’s perceptions of children’s symptoms. Waliski et al. (2013) reported on a sample of 172 National Guard parents who were asked whether they had a child with any emotional, behavioral, or adjustment problems. Parents who reported greater mental health symptoms (including, but not specific to PTSD) and lower satisfaction with family and social relationships also reported having a child with problems. Overall, mental health symptoms resulted in a 171% increase in the likelihood of a service member reporting a child with an emotional, behavioral, or adjustment problem.

Similarly, Sullivan et al. (2016) surveyed a non-random sample of 513 veterans living in southern California), who reported having at least one child. Child functioning was measured using a list of five challenges often experienced by children in military/veteran families (i.e., concerns about behavior, academic performance, peer relationships, emotional problems, and physical problems). Although most veterans did not report significant symptoms, veterans who reported higher levels of PTSD symptomatology were also more likely to report negative perceptions about their child’s functioning. Veteran fathers were significantly less likely to report concerns about negative child functioning compared with veteran mothers.

Though collectively these studies suggest that parental PTSD symptoms may increase the likelihood of parents reporting adjustment problem in their children, it is important to note that in the absence of standardized measure or cross-informant reports, a parent’s perception alone may not be an accurate nor reliable indicator of the actual behavioral problems of the child. It is possible that such reporting could be an indication of cognitive bias inherent in PTSD, which may lead a family member with PTSD to perceive more negative behavior in their close family members, which will be consistent with C-BIT theory (Dekel and Monson, 2010).

Conclusion

With regard to parenting outcomes, the studies reviewed indicated there is an association between parental PTSD symptoms in male military service members or veterans with self-reported parent-child functioning difficulties (Sayers et al., 2009; Allen et al., 2010; Khaylis et al., 2011). Consistent with the C-BIT model’s emphasis on the deleterious impacts of emotional disturbances on family functioning, new research indicates symptoms of depression may play an important role in parent-child functioning after deployment (Blow et al., 2013; Mustillo et al., 2014; Yablonsky et al., 2016). Several studies identified promising mechanisms through which PTSD symptoms may influence specific parenting difficulties – a considerable advance beyond what was previously available. For example, Brockman et al. (2016) found that while PTSD symptoms influenced parental distress avoidance, higher experiential avoidance was associated with less positive engagement with children. The work of Sherman and colleagues delineated several ways in which PTSD symptoms may directly influence parent-child functioning by implicating communication as a problem area and by linking specific symptoms of PTSD to areas of difficulty. With regard to other parenting behaviors, findings were somewhat conflicting, suggesting an association between PTSD with self-reported poorer parenting behaviors, but not with observed parenting behaviors (Gewirtz et al., 2010; Davis et al., 2015). More work is needed in this area. The two studies conducted in samples of women veterans and service members (Gewirtz et al., 2014; Creech et al., 2016) underscore the need for further work to understand the influence of military-related PTSD on parent-child functioning of mothers.

With respect to parental PTSD and child outcomes, there appears to be consensus that in active duty samples, parental PTSD symptoms have an effect on children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms, including depression, social emotional adjustment in young children, increased anxiety in early childhood, and adjustment problems in school-age children. However, these studies do not provide any insight whether the child outcomes are impacted differently if the active duty parent was the mother or the father. When such distinction is made, in veteran samples (e.g., Gewirtz et al., 2014; Sullivan et al., 2016), the results appear contradictory and suggest that female veterans were more likely to endorse adverse child functioning compared with male veterans. Studies comprising National Guard samples suggest a relationship between parental PTSD and child internalizing but not externalizing problems. However, few studies utilized standardized measures of child outcomes.

Directions for Future Research

The studies included in this review underscored several important considerations for future research. First, we were unable to find studies undertaken in non-United States populations. This may be a function of the databases used in the review or the requirement that studies were published in English; however, it is imperative that research begins to measure these processes in other countries. Second, as the number of women in the military continues to increase (at least in the United States) more work must oversample for women so that an understanding of the influence of military-related PTSD on mothers can be developed. Third, although work has been separately undertaken in United States reserve component service members as well as in active duty samples, less work is available that enables a comparison between the two. This may be important as the resources available to active duty are different than those available to reserve component service members and veterans. Finally, longitudinal and nationally representative studies that utilize standardized measures of PTSD and child outcomes will enable comparisons across studies and with community samples.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to literature searches and writing of this paper. Both authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

GM’s contribution to this manuscript was supported by a Fulbright Scholar Award.

Disclaimer

The contents of this manuscript are those of the authors and do notnecessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ∗ Denotes studies included in the review.

References

Alfano, C. A., Lau, S., Balderas, J., Bunnell, B. E., and Beidel, D. C. (2016). The impact of military deployment on children: placing developmental risk in context. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 43, 17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.003

∗Allen, E. S., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., and Markman, H. J. (2010). Hitting home: relationships between recent deployment, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. J. Fam. Psychol. 24, 280–288. doi: 10.1037/a0019405

∗Blow, A. J., Gorman, L., Ganoczy, D., Kees, M., Kashy, D. A., Valenstein, M., et al. (2013). Hazardous drinking and family functioning in National Guard veterans and spouses postdeployment. J. Fam. Psychol. 27, 303–313. doi: 10.1037/a0031881

∗Brockman, C.,Snyder, J., Gewirtz, A., Gird, S. R., Quattlebaum, J., Schmidt, N., et al. (2016). Relationship of service members’ deployment trauma, PTSD symptoms, and experiential avoidance to postdeployment family reengagement. J. Fam. Psychol. 30, 52–62. doi: 10.1037/fam0000152

Creech, S. K., Hadley, W., and Borsari, B. (2014). The impact of military deployment and reintegration on children and parenting: a systematic review. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 45, 452–464. doi: 10.1037/a0035055

∗Creech, S. K., Swift, R., Zlotnick, C., Taft, C., and Street, A. E. (2016). Combat exposure, mental health, and relationship functioning among women veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. J. Fam. Psychol. 30, 43–51. doi: 10.1037/fam0000145

∗Davis, L., Hanson, S. K., Zamir, O., Gewirtz, A. H., and Degarmo, D. S. (2015). Associations of contextual risk and protective factors with fathers’ parenting practices in the postdeployment environment. Psychol. Serv. 12, 250–260. doi: 10.1037/ser0000038

Dekel, R., and Monson, C. M. (2010). Military-related post-traumatic stress disorder and family relations: current knowledge and future directions. Aggress. Violent Behav. 15, 303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2010.03.001

Department of Defense (2014). 2013 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community. Available at: http://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2013-Demographics-Report.pdf

Fredman, S. J., Vorstenbosch, V., Wagner, A. C., Macdonald, A., and Monson, C. M. (2014). Partner accommodation in posttraumatic stress disorder: initial testing of the significant others’ responses to trauma Scale (SORTS). J. Anxiety Disord. 28, 372–381. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.04.001

Fulton, J. J., Calhoun, P. S., Wagner, H. R., Schry, A. R., Hair, L. P., Feeling, N., et al. (2015). The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in operation enduring freedom/operation Iraqi freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans: a meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 31, 98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.02.003

∗Gewirtz, A. H., Mcmorris, B. J., Hanson, S., and Davis, L. (2014). Family adjustment of deployed and nondeployed mothers in families with a parent deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 45, 465–477. doi: 10.1037/a0036235

∗Gewirtz, A. H., Polusny, M. A., Degarmo, D. S., Khaylis, A., and Erbes, C. R. (2010). Posttraumatic stress symptoms among National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq: associations with parenting behaviors and couple adjustment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 78, 599–610. doi: 10.1037/a0020571

∗Herzog, J. R., Everson, R. B., and Whitworth, J. D. (2011). Do secondary trauma symptoms in spouses of combat-exposed National Guard soldiers mediate impacts of soldiers’ trauma exposure on their children? Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 28, 459–473. doi: 10.1007/s10560-011-0243-z

Janke-Stedronsky, S. R., Greenawalt, D. S., Stock, E. M., Tsan, J. Y., Maccarthy, A. A., Maccarthy, D. J., et al. (2016). Association of parental status and diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans of Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom. Psychol. Trauma 8, 72–79. doi: 10.1037/tra0000014

Jobe-Shields, L., Flanagan, J. C., Killeen, T., and Back, S. E. (2015). Family composition and symptom severity among Veterans with comorbid PTSD and substance use disorders. Addict. Behav. 50, 117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.019

∗Khaylis, A., Polusny, M. A., Erbes, C. R., Gewirtz, A., and Rath, M. (2011). Posttraumatic stress, family adjustment, and treatment preferences among National Guard soldiers deployed to OEF/OIF. Mil. Med. 176, 126–131.

Lauterbach, D., Bak, C., Reiland, S., Mason, S., Lute, M. R., and Earls, L. (2007). Quality of parental relationships among persons with a lifetime history of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma. Stress 20, 161–172. doi: 10.1002/jts.20194

Leen-Feldner, E. W., Feldner, M. T., Bunaciu, L., and Blumenthal, H. (2011). Associations between parental posttraumatic stress disorder and both offspring internalizing problems and parental aggression within the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication. J. Anxiety Disord. 25, 169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.017

∗Lester, P., Aralis, H., Sinclair, M., Kiff, C., Lee, K.-H., Mustillo, S., et al. (2016). The impact of deployment on parental, family and child adjustment in military families. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 47, 938–949.

∗Lester, P., Peterson, K., Reeves, J., Knauss, L., Glover, D., Mogil, C., et al. (2010). The long war and parental combat deployment: effects on military children and at-home spouses. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 49, 310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.003

Monson, C. M., Fredman, S. J., and Dekel, R. (2010). “Posttraumatic stress disorder in an interpersonal context,” in Interpersonal Processes in the Anxiety Disorders: Implications for Understanding Psychopathology and Treatment, ed. J. G. Beck (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 179–208. doi: 10.1037/12084-000

Monson, C. M., Fredman, S. J., Dekel, R., and Macdonald, A. (2012). “Family models of posttraumatic stress disorder,” in The Oxford Handbook of Traumatic Stress Disorders, eds J. G. Beck and D. M. Sloan (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 219–234. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399066.013.0015

∗Mustillo, S., Xu, M., and Wadsworth, S. M. (2014). Traumatic combat exposure and parenting among national guard fathers: an application of the ecological model. Fathering 12, 303–319. doi: 10.3149/fth.1203.303

Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., and Chard, K. M. (2014). Cognitive Processing Therapy: Veteran/Military Version: Therapist and Patient Materials Manual. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

Ruscio, A. M., Weathers, F. W., King, L. A., and King, D. W. (2002). Male war-zone veterans’ perceived relationships with their children: the importance of emotional numbing. J. Trauma. Stress 15, 351–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1020125006371

Samper, R. E., Taft, C. T., King, D. W., and King, L. A. (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and parenting satisfaction among a national sample of male Vietnam veterans. J. Trauma. Stress 17, 311–315. doi: 10.1023/b:jots.0000038479.30903.ed

∗Sayers, S. L., Farrow, V. A., Ross, J., and Oslin, D. W. (2009). Family problems among recently returned military veterans referred for a mental health evaluation. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70, 163–170. doi: 10.4088/jcp.07m03863

∗Sherman, M. D., Larsen, J., Straits-Troster, K., Erbes, C., and Tassey, J. (2015). Veteran–child communication about parental PTSD: a mixed methods pilot study. J. Fam. Psychol. 29, 595–603. doi: 10.1037/fam0000124

∗Sherman, M. D., Smith, J. L. G., Straits-Troster, K., Larsen, J. L., and Gewirtz, A. (2016). Veterans’ perceptions of the impact of PTSD on their parenting and children. Psychol. Serv. 13, 401–410. doi: 10.1037/ser0000101

∗Sullivan, K., Barr, N., Kintzle, S., Gilreath, T., and Castro, C. A. (2016). PTSD and physical health symptoms among veterans: association with child and relationship functioning. Marriage Fam. Rev. 52, 689–705. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2016.1157122

∗Tomassetti-Long, V. J., Nicholson, B. C., Madson, M. B., and Dahlen, E. R. (2015). Hardiness, parenting stress, and PTSD symptomatology in U.S. Afghanistan/Iraq era veteran fathers. Psychol. Men Masc. 16, 239–245. doi: 10.1037/a0037307

∗Vaughn-Coaxum, R., Smith, B. N., Iverson, K. M., and Vogt, D. (2015). Family stressors and postdeployment mental health in single versus partnered parents deployed in support of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Psychol. Serv. 12, 241–249. doi: 10.1037/ser0000026

Vogt, D., Smith, B., Elwy, R., Martin, J., Schultz, M., Drainoni, M.-L., et al. (2011). Predeployment, deployment, and postdeployment risk factors for posttraumatic stress symptomatology in female and male OEF/OIF veterans. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 120, 819–831. doi: 10.1037/a0024457

Vogt, D., Smith, B. N., Fox, A. B., Amoroso, T., Taverna, E., and Schnurr, P. P. (2016). Consequences of PTSD for the work and family quality of life of female and male U.S. Afghanistan and Iraq War veterans. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 52, 341–352.

Wagner, A. C., Monson, C. M., and Hart, T. L. (2016). Understanding social factors in the context of trauma: implications for measurement and intervention. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 25, 831–853. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1152341

∗Waliski, A., Blevins, D., Spencer, H. J., Roca, J. V., and Kirchner, J. (2013). Family relationships, mental health, and injury among OEF/OIF veterans postdeployment. Mil. Behav. Health 1, 100–106. doi: 10.1080/21635781.2013.831335

Keywords: parenting, PTSD, child-parent functioning, parenting behaviors, child outcomes, military and veteran parents

Citation: Creech SK and Misca G (2017) Parenting with PTSD: A Review of Research on the Influence of PTSD on Parent-Child Functioning in Military and Veteran Families. Front. Psychol. 8:1101. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01101

Received: 26 January 2017; Accepted: 13 June 2017;

Published: 30 June 2017.

Edited by:

Danny Horesh, Bar-Ilan University, IsraelReviewed by:

Szabolcs Keri, University of Szeged, HungaryMiguel E. Rentería, QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Australia

Copyright © 2017 Creech and Misca. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gabriela Misca, Zy5taXNjYUB3b3JjLmFjLnVr

Suzannah K. Creech

Suzannah K. Creech Gabriela Misca

Gabriela Misca