94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 29 May 2017

Sec. Cognition

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00847

Economic status played an important role in the modulation of economic decision making. The present fMRI study aimed at investigating how economic status modulated behavioral and neural responses to unfairness in a modified Ultimatum Game (UG). During scanning, participants played as responders in the UG, and they were informed of the economic status of proposers before receiving offers. At the behavioral level, higher rejection rates and lower fairness ratings were revealed when proposers were in high economic status than in low economic status. Besides, the most time-consuming decisions tended to occur at lower unfairness level when the proposers were in high (relative to low) economic status. At the neural level, stronger activation of left thalamus was revealed when fair offers were proposed by proposers in high rather than in low economic status. Greater activation of right medial prefrontal cortex was revealed during acceptance to unfair offers in high economic status condition rather than in low economic status condition. Taken together, these findings shed light on the significance of proposers’ economic status in responders’ social decision making in UG.

Human behaviors in social decision-making are under the influence of unfairness-related decision making. In the past decades, an abundance of findings were provided that people insisted on maintaining fairness norms even at the cost of themselves. Among all the economic games, Ultimatum Game (UG) is a primary experimental tool used to explore the underlying mechanisms of human fairness (Guth et al., 1982; Thaler, 1988; Camerer and Thaler, 1995). A typical UG involves two players, one player (proposer) decides how to split a sum of money, and the other one (responder) decides whether to accept the division or not. If the responder accepts, both of them get the suggested division of money, otherwise they received nothing. Past researches revealed that, in spite of personal loss, people would reject extremely unfair offers to punish norm-violating behaviors (Guth et al., 1982), indicating the importance of perception of unfairness in social decision making.

Several fairness-related brain regions involved in UG, such as anterior insula (AI), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), have been identified in previous neuroimaging studies (Sanfey et al., 2003; Guroglu et al., 2010, 2011). It was suggested that the involvement of AI and ACC in UG were associated with negative affect elicited by unfair offers and with detecting and responding to violating fairness-related norms (Sanfey et al., 2003; Montague and Lohrenz, 2007; Guroglu et al., 2010, 2011). Moreover, the activation of DLPFC was associated with top–down inhibition of self-interested impulses to accept unfair offers and with integrating information and selecting appropriate responses to unfair offers (Buckholtz et al., 2008; Guroglu et al., 2010; Buckholtz and Marois, 2012).

Previous researches have demonstrated that economic status played a role in the modulation of economic decision making (Holm and Engseld, 2005; Haile et al., 2008). It was indicated that during a UG task, proposers preferred to give higher offers to responders in low economic status rather than ones in high economic status (Holm and Engseld, 2005). It was also revealed that with the increase of age, children began to take others’ economic status into account during resource allocation, i.e., they would give more resource to poor individuals than wealthy ones during a resource allocation task (Paulus, 2014).

However, most studies focused on how proposers might consider economic status of responders in the bargaining, few of them shed light on the effect of proposers’ economic status during responders’ decision making. Previous research demonstrated that people in the higher socioeconomic status who owned more resources were likely to engage in more prosocial behaviors and volunteered more (Granzin and Olsen, 1991; Penner et al., 2005; Piff et al., 2010) than others who were in the lower socioeconomic status. Thus individuals in superior economic status might be expected to give a higher offer in the UG task and therefore unfair offers proposed by high socioeconomic status individuals might induce larger discrepancy with expectation, resulting in stronger emotional response. Hence it is likely that people would reject more unfair offers from people in superior economic status.

In the present study, we used a modified UG in which participants acted as responders and were informed of proposers’ economic status before receiving offers. We aimed to investigate three following questions. Firstly, we were interested in how proposers’ economic status modulated responders’ perception of unfairness. It was predicted that participants would consider proposers’ economic status so that they would feel higher level of unfairness when offered by proposers in superior economic status rather than those in inferior status. Secondly, we tried to reveal how proposers’ economic status modulated participants’ response to unfair offers. We predicted that participants would reject more unfair offers from proposers in superior (relative to inferior) economic status. Moreover, we tried to explore the neural mechanisms underlying the modulating effect of proposer’s economic status on unfairness-related social decision making. Recent studies have shown that thalamus (Zink et al., 2008; Hu et al., 2016), which was associated with social emotional arousal, and the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) (Zink et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2014), which was related to recognizing intentions and motives of others, were involved in processing of social status. As social status and economic status are both included in social hierarchies (Zink et al., 2008), the thalamus and MPFC may also engaged in encode economic status by processing responders’ perception of unfairness and responses to unfair offers related to economic status.

Twenty one right-handed volunteers [12 females, mean age = 22.8 ± 1.4 (SD) years] took part in this study. All the participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and none of them reported any abnormal neurological history. One participant was excluded from further statistical analyses due to severe head motion (>3°) during scanning. And two participants had to be excluded because of no acceptance responses to unfair offers in the High economic status condition. Written informed consent was acquired from all the participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of East China Normal University.

Seventy two common Chinese names were abbreviated (i.e., “Zhang L.” was an abbreviation of “Zhang Liang”) and displayed as proposers in the procedure. These names were randomly allocated to two conditions (Economic Status: High and Low). In each condition, there were 36 names [12 for fair proposals (¥25: ¥25), and 6 for each of unfair proposals (¥5: ¥45, ¥10: ¥40, ¥15: ¥35 and ¥20: ¥30)]. The gender and number of words were counterbalanced across names in different conditions.

Participants were told that they would participate in an economic game with 72 different partners (students from the same university with them), along with an instruction introducing the rule of the game. Participants were told that proposers’ monthly family income was collected as economic status using a 10-step economic ladder in this study (Adler et al., 2000), with step-1 indicating the lowest economic status, and step-10 indicating the highest economic status. The economic status of the proposers in this study was either on step-1 or on step-10. They were also told that the proposals were obtained from different proposers before the experiment. And participants would also be asked about their own economic status after the experiment (Figure 1). Then participants were told that they would be presented with a proposal from one of the proposers about how to split ¥50 between them, and they could decide to either accept or reject the proposal with acceptance leading to the suggested split and rejection leaving both of them nothing. As for the payment, participants were told that both of themselves and the proposers would be paid according to their decision in each trial after some kind of transformation. They would be paid with a basic payment for their participation (¥50, ≈8.04 US$) plus the amount of money obtained from a random selection of 6% trials in the game.

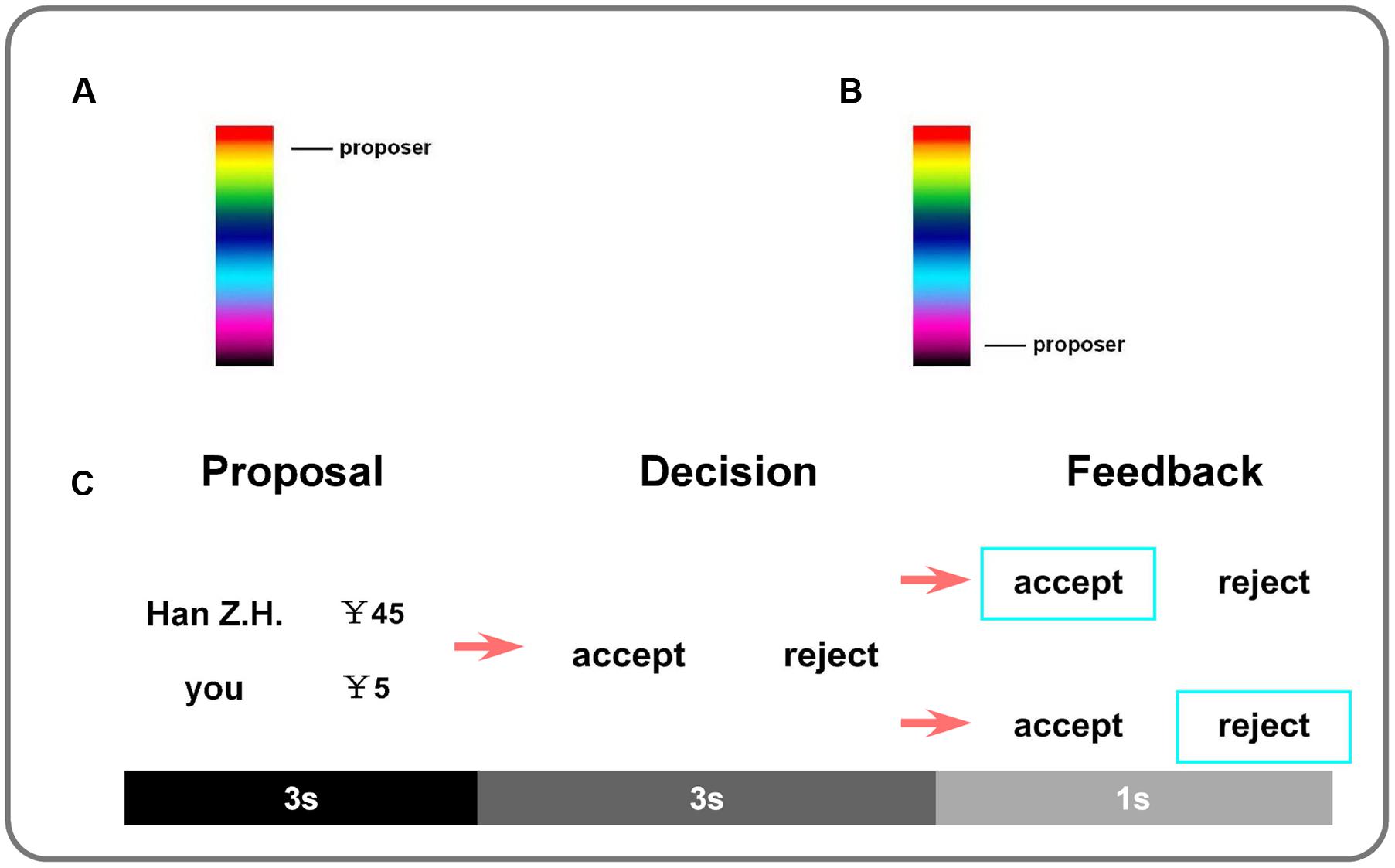

FIGURE 1. Participants were scanned while playing the game for 12 blocks (six High economic status blocks and six Low economic status blocks). Proposer’s economic status was displayed at the beginning of every block. (A) An arrow pointing to the top of the histogram indicating the High economic status, (B) An arrow pointing to the bottom of the histogram indicating the Low economic status. In each block, there were two fair proposals and four different unfair proposals (¥5: ¥45, ¥10: ¥40, ¥15: ¥35 and ¥20: ¥30). (C) In each trial, the proposal screen was presented for 3 s to display the split between the proposer and the participant (responder). Then the decision cue appeared and participants were required to decide whether to accept or reject the offer within 3 s by pressing corresponding buttons. Once they responded, a blue frame outside the selected choice would be presented for 1 s to provide feedback of their decision.

Before scanning, participants practiced four blocks included 24 trials on a laptop. There were 12 blocks during scanning, including six blocks in which all the proposers were in high economic status and another six blocks in which all the proposers were in low economic status. Different status blocks were alternated with one another and counterbalanced across the participants (ABABABABABAB for half of the participants and BABABABABABA for the rest). Each block lasted for 70∼75.8 s, with a 5-s rest between every two blocks. Before each block, a 6-s cue of proposer’s economic status was displayed by a graduated color histogram to inform the participants about the economic status of the proposers in the following block, with an arrow pointing to the bottom of the histogram indicating the Low economic status, and pointing to the top of the histogram indicating the High economic status. Each block contained two fair proposals and four different unfair proposals (¥5: ¥45, ¥10: ¥40, ¥15: ¥35, and ¥20: ¥30). All of the trials in a block were presented in a random order. For each trial, the proposal screen was presented for 3 s to display the split between the proposer and the participant (responder). Then a decision cue appeared and participants were required to decide whether to accept or reject the offer within 3 s by pressing the corresponding buttons of the magnet-compatible button Box (i.e., right index finger for acceptance and right middle finger for rejection). Once they responded, a blue frame outside the selected choice would be presented for 1 s to provide participants with the feedback of their decision. The intervals between trials were jittered from 2 to 4 s. There was also one jittered blank (500∼1500 ms) between the proposal screen and the decision cue.

After scanning, the same stimuli including proposers’ economic statuses and proposals were presented again. Participants were asked to rate the fairness of each offer on a 9-point Likert-type scale with 1 indicating extremely unfair and 9 indicating extremely fair. And participants were also asked to rate their own economic status from 1 indicating the lowest economic status and 10 indicating the highest economic status.

Participants were scanned using a 3T Siemens scanner at the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Magnetic Resonance of East China Normal University. Firstly, we acquired anatomical images of each participants using a T1-weighted, multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) sequence (TR = 2530 ms, TE = 2.34 ms, 192 slices, slice thickness = 1 mm, FOV = 256 mm, matrix size = 256 ∗ 256) (Cheng et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). After that, a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) was used to acquire the sequence functional images (TR = 2400 ms, TE = 30 ms, FOV = 220 mm, matrix size = 64 ∗ 64, 39 slices, slice thickness = 3 mm) (Cheng et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015).

SPM8 software package (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London) was employed to perform the preprocessing and statistical analyses of brain imaging data. The first five functional images were excluded from each subject to allow scanner equilibrium effects. Then, all functional images were slice timing corrected, realigned, normalized into the MNI space (resampled at 2 mm ∗ 2 mm ∗ 2 mm voxels), and smoothed with an 8-mm full-width half maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel (Cheng et al., 2015).

First-level analyses were then performed for each subject using general linear models (GLM) implemented in SPM8. We modeled onsets of the proposal screens and onsets of the decision cues for six types of events, including LF (fair offers in the Low economic status condition), LUA (accepted unfair offers in the Low economic status condition), LUR (rejected unfair offers in the Low economic status condition), HF (fair offers in the High economic status condition), HUA (accepted unfair offers in the High economic status condition) and HUR (rejected unfair offers in the High economic status condition). Additionally regressors of no interest were the cues of proposers’ economic status, the feedbacks for acceptance, the feedbacks for rejection, and proposal screen and decision cue for trials which participants failed to respond to. All these regressors were modeled with zero duration and convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF). Moreover, six realignment parameters and one overall mean during the whole phase were included in the design matrix as well. To filter the low-frequency noise, a cutoff of 192 s was applied. During first-level analyses, six contrast images (LF, LUA, LUR, HF, HUA, HUR) for proposal presentation were acquired from each participant and were fed into another flexible design in the second-level analyses.

Brain activities related to unfairness were defined by contrasting fair trials with unfair trials and the reverse contrasts. Brain activations corresponding to economic status were identified by the (High – Low) and reverse contrasts. The (Reject–Accept)Unfair and reverse contrasts were tested to compute brain activations related to participant’s responses (rejecting and accepting unfair offers). Then, the economic status ∗ unfairness interactions defined by (Unfair – Fair)High – (Unfair – Fair)Low and their reverse contrasts were computed to explore how contexts affect unfairness in all trials. The economic status ∗ response interactions defined by (Reject – Accept)Unfair High – (Reject – Accept)Unfair Low and their reverse contrasts were also tested to extract specific regions showing modulation of responders’ responses to unfair offers by different contexts. A voxel-level threshold of p < 0.001 (uncorrected) and a cluster-level FWE correction p < 0.05 were used. To further test how the economic status affected brain activations to perception of unfairness and response to unfair offers, specific activations identified in the interactions were used to compute regions of interest (ROIs). All the significant voxels in the activated clusters within 6 mm spherical regions centered on the peak or local maximum coordinates were included in each ROI. Beta estimates across ROIs were extracted for further statistics using the MarsBaR toolbox in SPM8.

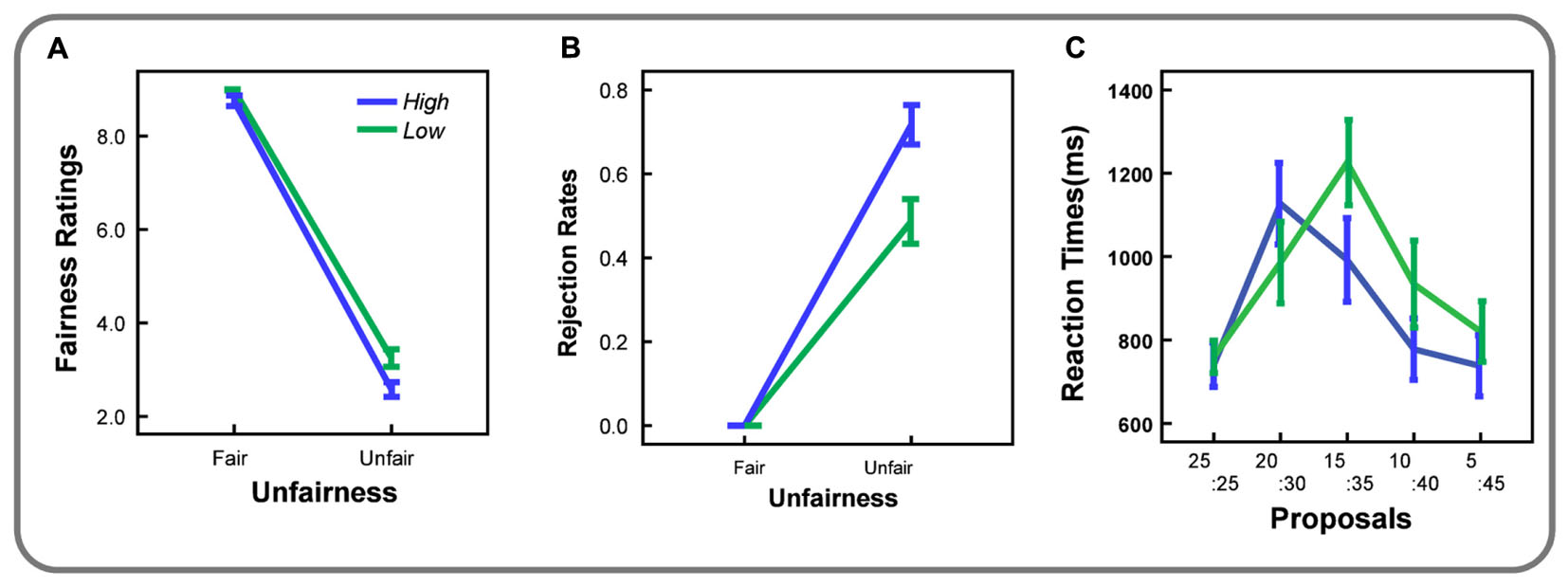

The behavioral variable of interest was the fairness ratings of UG offers (Figure 2A). A 2 (economic status: low vs. high) ∗ 2 (unfairness: fair vs. unfair) ANOVA revealed significant main effects of economic status [F(1,17) = 28.00, p < 0.01, = 0.62) and unfairness [F(1,17) = 1575.88, p < 0.01, = 0.99], indicating higher ratings in the Low economic status condition than in the High economic status condition and decreased ratings to unfair offers than fair offers. The interaction was significant [F(1,17) = 16.42, p < 0.01, = 0.49]. Paired t-tests revealed higher ratings in the Low economic status condition relative to the High economic status condition whether the offers were fair [t(17) = 7.42, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 0.50] or not [t(17) = 2.12, p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.75].

FIGURE 2. (A) Fairness ratings, (B) Rejection rates, and (C) Reaction times were plotted as a function of unfairness level in both economic status conditions. Error bars indicate SEM.

The behavioral variable of interest was the rejection rates (Figure 2B). A 2 (economic status: low vs. high) ∗ 2 (unfairness: fair vs. unfair) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant main effects of economic status [F(1,17) = 118.96, p < 0.01, = 0.88] and unfairness [F(1,17) = 622.42, p < 0.01, = 0.97], indicating higher rejection rates in high economic status than in low economic status conditions. A significant interaction was also found [F(1,17) = 118.96, p < 0.01, = 0.88]. Further paired t-tests showed that, although participants accepted all the fair offers, they rejected some of the unfair offers. Rejection rates for unfair trials in the High economic status condition were significantly higher than those in the Low economic status condition [t(17) > 10.91, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 2.57].

Given that UG is a time-consuming social decision making task, which involves complicated trade-off among motivations favoring either acceptance or rejection, reaction times (RT) was also analyzed in the present study. For RTs, a 2 (economic status: low vs. high) ∗ 5 (unfairness level: ¥25: ¥25 vs. ¥20: ¥30 vs. ¥15: ¥35 vs. ¥10: ¥40 vs. ¥5: ¥45) ANOVA was also carried out (Figure 2C). Results showed the main effects of economic status [F(4,68) = 5.48, p < 0.05, = 0.24) and unfairness level [F(4,68) = 17.70, p < 0.01, = 0.51], indicating longer RTs in the Low economic status condition than in the High economic status condition, and longer RTs for medium unfairness levels (¥20: ¥30 and ¥15: ¥35) than for high unfairness levels (¥10: ¥40 and ¥5: ¥45). The interaction was also significant [F(4,68) = 6.43, p < 0.01, = 0.27]. Paired t-tests revealed that, RTs for trials of ¥15: ¥35 in the Low economic status condition were significantly longer than RTs for trials of other offers (ts > 3.55, ps < 0.01, Cohen’s ds > 0.83). And in the High economic status condition, the average of RTs for trials of ¥20: ¥30 was the longest among all offer conditions. RTs for trials of ¥20: ¥30 were significantly longer than that of other offers (ts > 5.62, ps < 0.01, Cohen’s ds > 1.32), except for RTs for trials of ¥15: ¥35 [t(17) = 1.64, p > 0.1]. We then carried out a further chi-square test to investigate whether the probability of observing longest RT from a participant on two unfairness levels (¥20: ¥30, ¥15: ¥35) would be different between economic statuses. Results revealed significant difference when proposers were in high and low economic status (χ2 = 7.20, p < 0.05, w = 1.07).

Additionally, a one-sample t-test was also used to check participants’ own economic status. The average rating was 4.67 ± 0.97 (SD), which was significantly higher than the Low economic status and lower than the High economic status (ts > 16.03, ps < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 3.78). It indicated that economic status of participants was inferior to the High economic status and superior to the Low economic status.

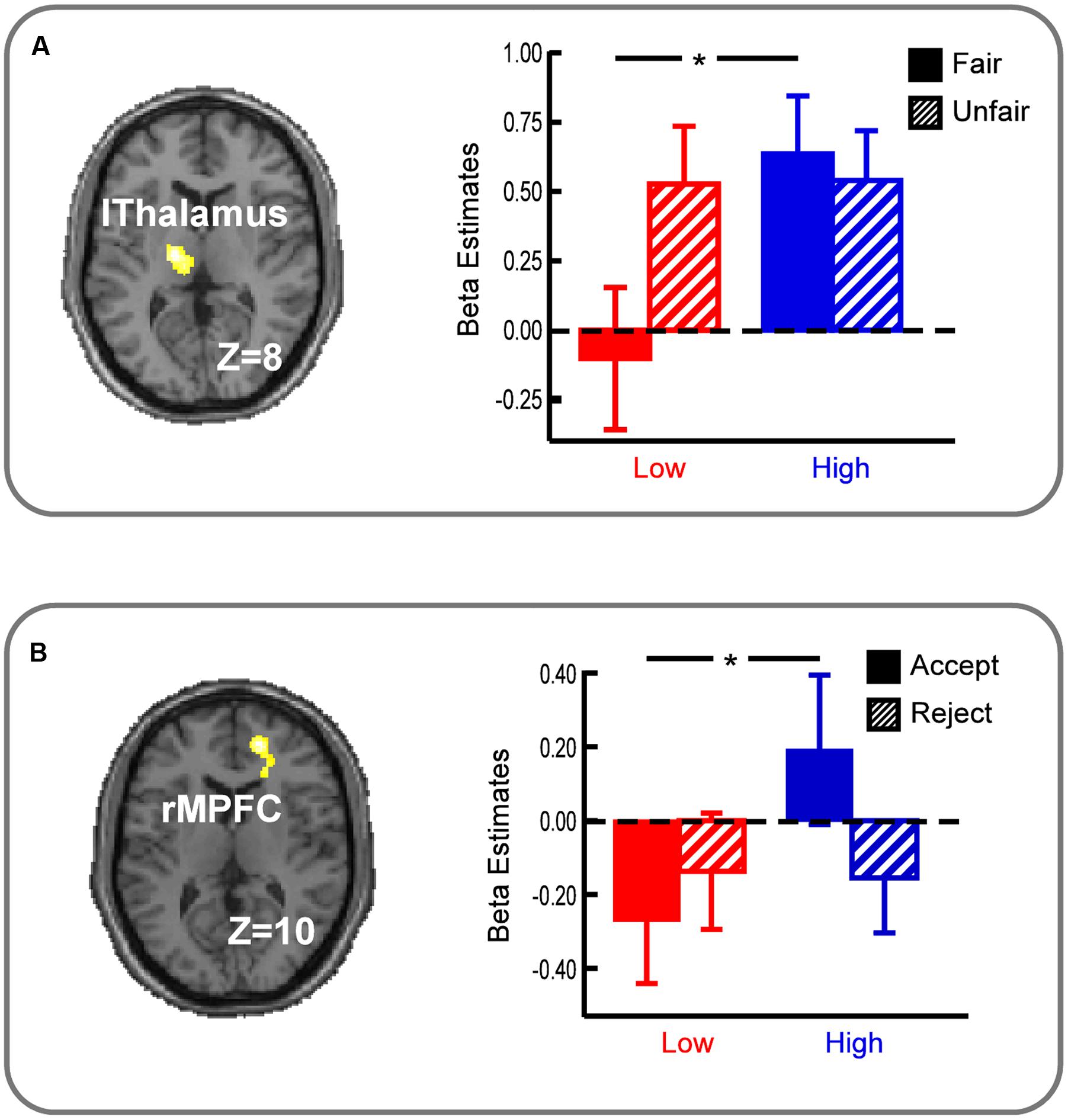

Interaction between unfairness and economic status was computed by the [(Unfair – Fair)Low – (Unfair – Fair)High] and the reverse contrasts. The [(Unfair – Fair)Low – (Unfair – Fair)High] contrast showed activations in left thalamus (MNI -16 -14 8), and the reverse contrast showed no significant activations (Table 1). As shown in Figure 3A, analyses on beta estimates revealed that left thalamus activated stronger in the HF conditions compared with the LF conditions (p < 0.01), and showed no significant activation difference between the HU conditions and the LU conditions (p > 0.1).

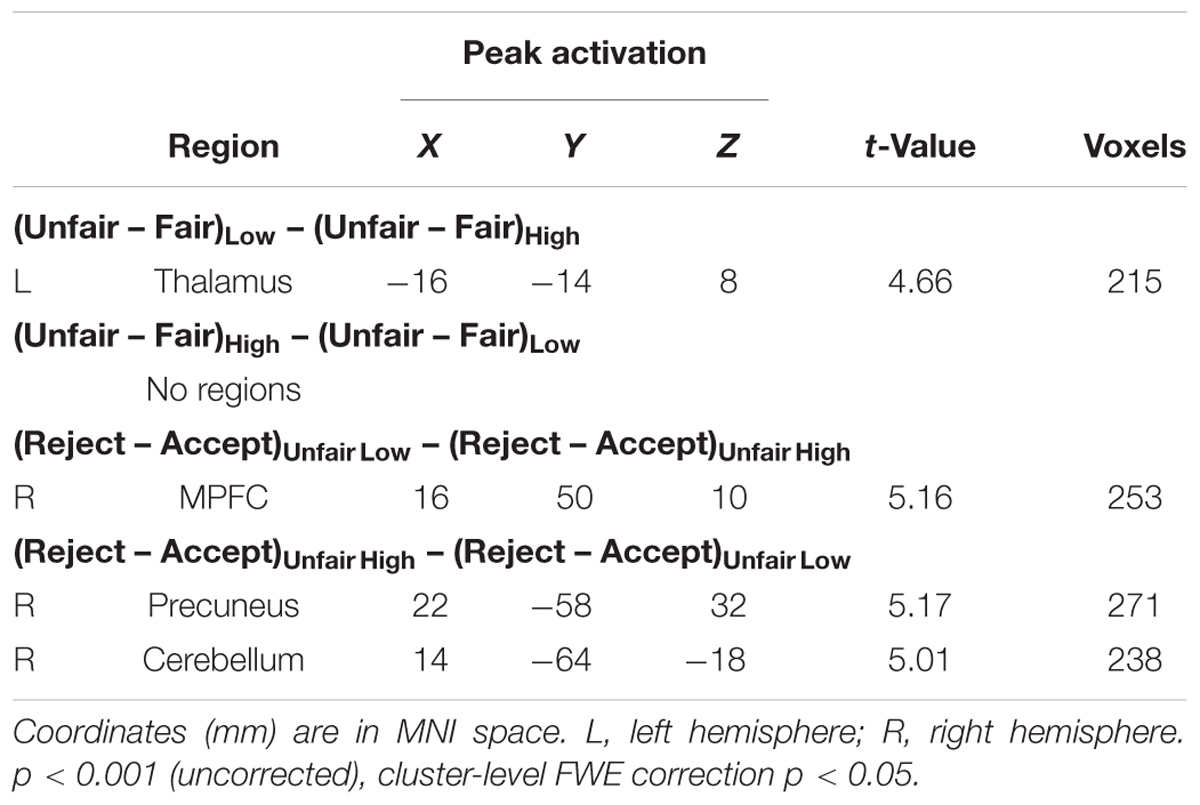

TABLE 1. Regions showing unfairness ∗ economic status interactions and responses during unfair trials ∗ economic status interactions.

FIGURE 3. (A) Left Thalamus showed the modulation of economic status on perception of unfairness. (B) Right MPFC showed the modulation of economic status on responses to unfair offers. l, left hemisphere; r, right hemisphere. All the activations survived the voxel-level threshold of uncorrected p < 0.001 with the cluster-level threshold of Family wise error (FWE) corrected p < 0.05. Error bars indicate SEM. ∗p < 0.01.

Additionally, main effect of unfairness was also computed by the (Unfair – Fair) and the reverse contrasts. Consistent with previous researches (Sanfey et al., 2003; Guroglu et al., 2010, 2011), the (Unfair – Fair) contrast revealed activations in bilateral DLPFC (MNI -48 26 32; 40 16 42), left AI (MNI -30 20 4) and right ACC (MNI 10 34 28). No region of interest was activated in the reverse contrast (Table 2).

Interaction between responses and economic status was computed by the [(Reject – Accept)Unfair Low – (Reject – Accept) Unfair High] and the reverse contrasts. The [(Reject – Accept) Unfair Low – (Reject – Accept)Unfair High] contrast showed activations in right MPFC (MNI 16 50 10), and no region of interest was activated in the reverse contrast (Table 1). Right MPFC revealed to be more active in the HUA conditions than in the LUA conditions (p < 0.01), and showed no significant activation difference between the HUR conditions and the LUR conditions (p > 0.1) (Figure 3B).

In this study, we used a modified UG to investigate how economic status of proposers modulated responders’ unfairness-related decision making and the underlying neural mechanisms. When facing with proposers in high (relative to low) economic status, participants felt higher level of unfairness, and significant left thalamus activations was found when receiving fair offers from proposers in high economic status rather than ones in low economic status. Moreover, participants rejected more unfair offers, and stronger right MPFC activations were observed during acceptance of unfair offers by individuals in high economic status compared with ones in low economic status.

Consistent with our prediction, lower fairness ratings were revealed in the High economic status condition than in the Low economic status condition, whether participants received unfair or fair offers. As proposers in high economic status owned more resources than participants in low economic status, the lower ratings suggested that people in superior economic status were expected to give higher offers.

Significant activation of thalamus was identified in interaction between economic status and perception of unfairness of responders. Activations to fair offers were higher in the High economic status condition compared with those in the low condition. Previous studies about processing of social status revealed that the thalamus was most activated when viewing information from superior status, and it was argued by the researchers that thalamus was associated with an emotional arousal response to the superior player (Zink et al., 2008). Since economic status and social status were both involved in human social hierarchies (Zink et al., 2008), it suggested that activation of thalamus in this study might also reflect such emotional arousal related to economic status. Moreover, as shown in fairness ratings to fair offers, participants gave lower ratings to offers in the High (relative to Low) economic status condition, indicating that people felt unfair even if proposers in high economic status gave equal splits. So the increasing activation of thalamus might be related to the emotional arousal so that participants might feel higher level of unfairness to proposers in high economic status, even when they proposed fair offers. Additionally, consistent with previous studies in which thalamus engaged in processing of perception of unfairness (Kirk et al., 2011; Servaas et al., 2015), stronger activations to unfair offers were observed both in the High and Low economic status condition.

Participants were more likely to reject unfair offers when the proposers were in high economic status rather than in low economic status, indicating that economic status exerted influence on response to unfair offers. Furthermore, longest RTs were found when participants were offered ¥20 from proposers in high economic status. But if offered by proposers in low economic status, the longest RTs of responders were observed when the offer was ¥15. This result indicated that participants had to make tradeoff between self-interest and fairness perception at a higher offer when offered by proposers in high economic status than in low economic status. In consideration of the higher expectation on distribution from proposers in high economic status, responses to proposers in high economic status became a time-consuming work at a lower unfairness level than responses to ones in low economic status.

Activation of MPFC revealed higher activations to accept unfair offers from proposers in high economic status compared with in low economic status. MPFC was engaged in processing of socioeconomic status and associated with recognizing intentions and motives of other people (Frith and Frith, 2003; Frith and Frith, 2006; Zink et al., 2008). Although unfair offers from people in high economic status were more likely to be rejected and rated as more unfair, however, more rejections leaded to a higher cost of participants. Higher activations in MPFC suggested that, in view of personal loss, participants would accept the unfair offers from proposers in high economic status after thinking about the thoughts and feelings of them in order to rationalize the decisions from proposers.

The present study explored how economic status would modulate unfairness-related decision making. Focusing on modulation of perception of unfairness by economic status, fairness ratings were found lower when offered by proposers in high economic status than in low economic status, and stronger thalamus activations were induced when receiving fair offers from proposers in high economic status than in low economic status. With respect to modulation of responses to unfairness by economic status, responses to proposers in high (relative to low) economic status became most time-consuming at a lower unfairness level, and people tended to reject unfair offers from proposers in high economic status. Moreover, increased MPFC activations were observed when accepting unfair offers from individuals in high economic status. To conclude, both perception of unfairness and responses to it were behaviorally and neurally modulated by economic status.

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Ethics Committee of East China Normal University with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of East China Normal University.

YZ, XC, LZ, GY, and XG devised the concept and supervised the study. YZ and JX collected the data. YZ, XC, LZ, LL, and XG joined in the interpretation of data. YZ, XC, LZ, and LL carried out the writing of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [31271090; 71371180]; and the Key Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China [14AZD106]; and the Outstanding Doctoral Dissertation Cultivation Plan of Action (PY2015042).

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., and Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol. 19, 586–592. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Buckholtz, J. W., Asplund, C. L., Dux, P. E., Zald, D. H., Gore, J. C., Jones, O. D., et al. (2008). The neural correlates of third-party punishment. Neuron 60, 930–940. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.016

Buckholtz, J. W., and Marois, R. (2012). The roots of modern justice: cognitive and neural foundations of social norms and their enforcement. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 655–661. doi: 10.1038/nn.3087

Camerer, C., and Thaler, R. H. (1995). Anomalies: ultimatums, dictators and manners. J. Econ. Perspect. 9, 209–219. doi: 10.1257/jep.9.2.209

Cheng, X., Zheng, L., Li, L., Guo, X., Wang, Q., Lord, A., et al. (2015). Power to punish norm violations affects the neural processes of fairness-related decision making. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 9:344. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00344

Frith, C. D., and Frith, U. (2006). The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron 50, 531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.001

Frith, U., and Frith, C. D. (2003). Development and neurophysiology of mentalizing. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 358, 459–473. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1218

Granzin, K. L., and Olsen, J. E. (1991). Characterizing participants in activities protecting the environment: a focus on donating, recycling, and conservation behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 10, 1–27.

Guroglu, B., van den Bos, W., Rombouts, S. A. R. B., and Crone, E. A. (2010). Unfair? It depends: neural correlates of fairness in social context. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 5, 414–423. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq013

Guroglu, B., van den Bos, W., van Dijk, E., Rombouts, S. A., and Crone, E. A. (2011). Dissociable brain networks involved in development of fairness considerations: understanding intentionality behind unfairness. Neuroimage 57, 634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.032

Guth, W., Schmittberger, R., and Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 3, 367–388. doi: 10.1016/0167-2681(82)90011-7

Haile, D., Sadrieh, A., and Verbon, H. A. A. (2008). Cross-racial envy and underinvestment in South African partnerships. Cambridge J. Econ. 32, 703–724. doi: 10.1093/cje/ben011

Holm, H., and Engseld, P. (2005). Choosing bargaining partners – an experimental study on the impact of information about income, status and gender. Exp. Econ. 8, 183–216. doi: 10.1007/s10683-005-1463-x

Hu, J., Blue, P. R., Yu, H., Gong, X., Xiang, Y., Jiang, C., et al. (2016). Social status modulates the neural response to unfairness. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11, 1–10. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv086

Kirk, U., Downar, J., and Montague, P. R. (2011). Interoception drives increased rational decision-making in meditators playing the ultimatum game. Front. Neurosci. 5:49. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00049

Montague, P. R., and Lohrenz, T. (2007). To detect and correct: norm violations and their enforcement. Neuron 56, 14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.020

Paulus, M. (2014). The early origins of human charity: developmental changes in preschoolers’ sharing with poor and wealthy individuals. Front. Psychol. 5:344. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00344

Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., and Schroeder, D. A. (2005). Prosocial behavior: multilevel perspectives. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 365–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070141

Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., Cote, S., Cheng, B. H., and Keltner, D. (2010). Having less, giving more: the influence of social class on prosocial behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 771–784. doi: 10.1037/a0020092

Sanfey, A. G., Rilling, J. K., Aronson, J. A., Nystrom, L. E., and Cohen, J. D. (2003). The neural basis of economic decision-making in the ultimatum game. Science 300, 1755–1758. doi: 10.1126/science.1082976

Servaas, M. N., Aleman, A., Marsman, J.-B. C., Renken, R. J., Riese, H., and Ormel, J. (2015). Lower dorsal striatum activation in association with neuroticism during the acceptance of unfair offers. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 15, 537–552. doi: 10.3758/s13415-015-0342-y

Thaler, R. H. (1988). Anomalies – the winners curse. J. Econ. Perspect. 2, 191–202. doi: 10.1257/jep.2.1.191

Wang, F., Kessels, H. W., and Hu, H. (2014). The mouse that roared: neural mechanisms of social hierarchy. Trends Neurosci. 37, 674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.07.005

Wang, X., Zheng, L., Cheng, X., Li, L., Sun, L., Wang, Q., et al. (2015). Actor-recipient role affects neural responses to self in emotional situations. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 9:83. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00083

Keywords: ultimatum game (UG), economic status, fMRI, perception of unfairness, decision making

Citation: Zheng Y, Cheng X, Xu J, Zheng L, Li L, Yang G and Guo X (2017) Proposers’ Economic Status Affects Behavioral and Neural Responses to Unfairness. Front. Psychol. 8:847. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00847

Received: 17 March 2017; Accepted: 09 May 2017;

Published: 29 May 2017.

Edited by:

Tifei Yuan, Nanjing Normal University, ChinaReviewed by:

Qi Li, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (UCAS), ChinaCopyright © 2017 Zheng, Cheng, Xu, Zheng, Li, Yang and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Li Zheng, bHpoZW5nQHBzeS5lY251LmVkdS5jbg== Guang Yang, Z3lhbmdAcGh5LmVjbnUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.