- Department of Human Sciences, Università degli Studi di Bergamo, Bergamo, Italy

Children get involved in social categorization. Thus, they are able to stigmatize peers as well as to show in-group favoritism theorized by Tajfel and Turner (1986). Moreover, according to Aboud's Cognitive-Developmental Theory (1988, 2003) the intensity of children's stereotypes and negative attitudes toward socially devalued group members changes with age, in line with their cognitive development. In our Western society, which addresses especially females with the message that thinness is beauty, self-efficacy, power, and success, being overweight or obese is one of the most socially devalued and stigmatized conditions among children. Thus, overweight and obese children are more likely to be personally and socially devalued compared to their average size peers. Starting with these theoretical reflections, the objectives of this mini-review are to examine if: (1) obese children show in-group favoritism and thus show less anti-fat attitudes than their thin and normal weight peers; (2) fat stigma is more prevalent toward overweight and obese girls than toward boys; (3) the intensity of weight-related stigma changes with the cognitive development of children.

Introduction

According to Tajfel and Turner (1986), social categorization is a process that allows people to analyze the environment, act efficiently within it, and to identify people's position in society, in relation to the value socially attributed to their group membership. The outcome of this process is the social identity, the part of one's self-concept that derives from group memberships. This self-concept is relational, relative, and comparative. Therefore, people's self-esteem depends on the positive or negative worth conferred to their group membership. Individuals who belong to devalued groups undergo stigmatization. Stigma is a set of negative beliefs and attitudes that are shown by bias, stereotypes, prejudices, rejection, and discrimination toward target groups. Independently from the value ascribed to a group, people tend to evaluate their in-group members more positively than out-group components.

Yee and Brown (1992) stated not only that children get involved in the social categorization process but also that when as young as 3 years old they show in-group favoritism.

Moreover, Aboud (1988, 2003) suggested that children's stereotypes change with their cognitive development. Specifically, per his Cognitive-Developmental Theory, young children's evaluations are dominated by the fear of the unfamiliar and are therefore crude and encompassing toward differences. By approximately 5–8 years of age, children's prejudice reach a peak, as they prefer their in-group to out-groups and then, from about 8 to 9 years of age, it decreases because children increasingly appreciate other people's perspectives.

Stigma, like categorization is context-dependent. Therefore, in different cultures and at different times, stigmatization may affect different groups. Today, in our Western society, obesity appears as one of the most stigmatizing and least socially acceptable conditions among children (Schwimmer et al., 2003). Several studies have highlighted that overweight and obese children are more likely to be victims of aggression than normal size peers and are frequently exposed to peers' intentional negative actions that are physical (e.g., kicking, pushing, hitting), verbal (e.g., being teased, name calling, derogatory remarks,) or relational (e.g., being ignored or avoided, social exclusion, being targets of rumors; Janssen et al., 2004; Griffiths et al., 2006; Puhl and Latner, 2007).

This phenomenon can be explained through the impact of the socially dominant esthetic ideals that equate thinness with beauty, self-efficacy, power, and success and that is pervasive especially for girls more than for boys (Grossi and Ruspini, 2007; Riva, 2012).

Based on the stimulus provided by the aforementioned theories the present review examines if:

1. Obese children show in-group favoritism and thus show less anti-fat attitudes than their thin and normal weight peers.

2. Fat stigma is more prevalent toward overweight and obese girls than toward boys.

3. The intensity of weight-related stigma changes as does the cognitive development of children.

Methods

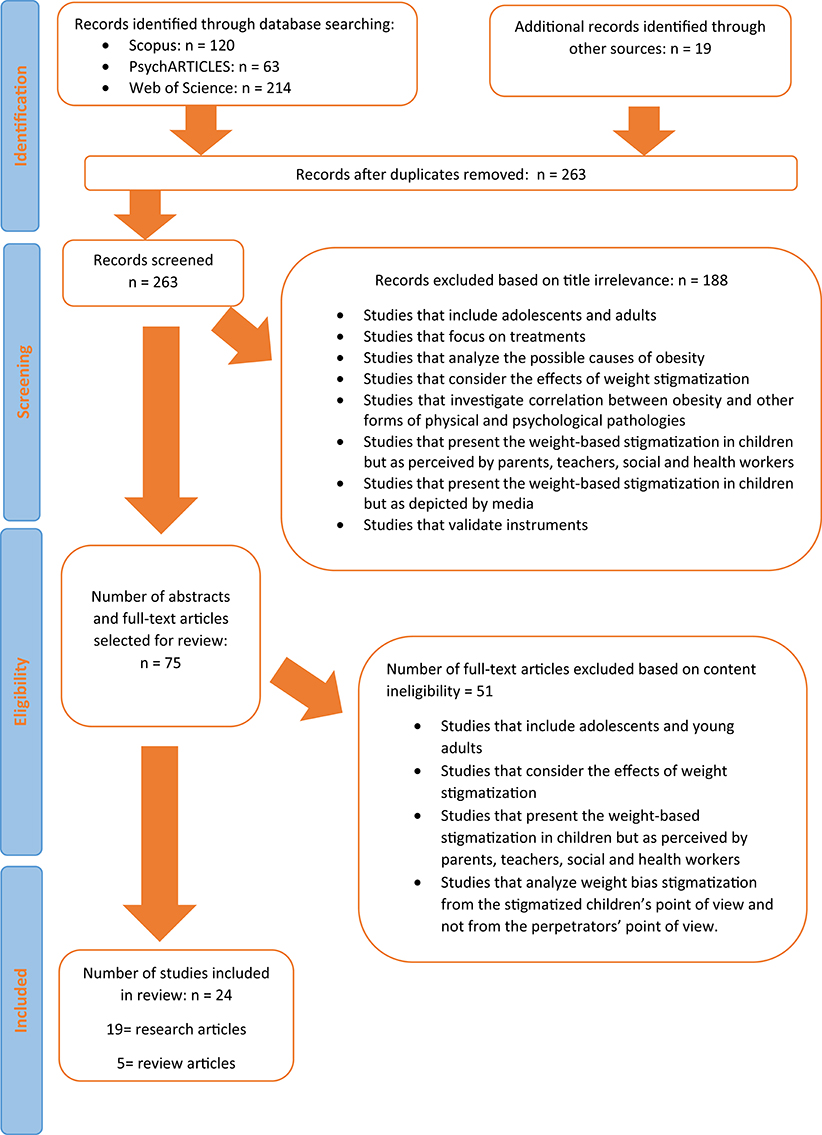

Electronic databases (PsycARTICLES, Scopus and Web of Science) were searched using the following 8 terms “victimization,” “anti-fat bias,” “anti-fat attitude,” “stigmatization,” “stigma,” “discrimination,” “prejudice,” “stereotype” combined with “obese children” or “obesity AND children.” Databases were investigated limiting the search to psychology and social work but excluding any restrictions about articles' year of publication.

Additional manuscripts were derived from the bibliography's analysis of eligible articles.

Studies were included in the review if: (1) the age of participants didn't exceed 11 years old1; (2) the weight-based stigmatization phenomenon was analyzed by the perpetrator's point of view and not by the victims' or by the observers' ones; (3) the main objective of the study was to assess the presence and the nature of this phenomenon instead of focusing on its causes and its effects.

Results

As described in Figure 1, the initial search identified 416 papers. One hundred and fifty-three articles were removed due to duplication, 188 excluded upon review of title and another 38 left out after reading abstracts and full texts. The process resulted in 24 papers for inclusion in the review. Five articles were reviews and thus were not addressed in the results section.

Overall Study Characteristics

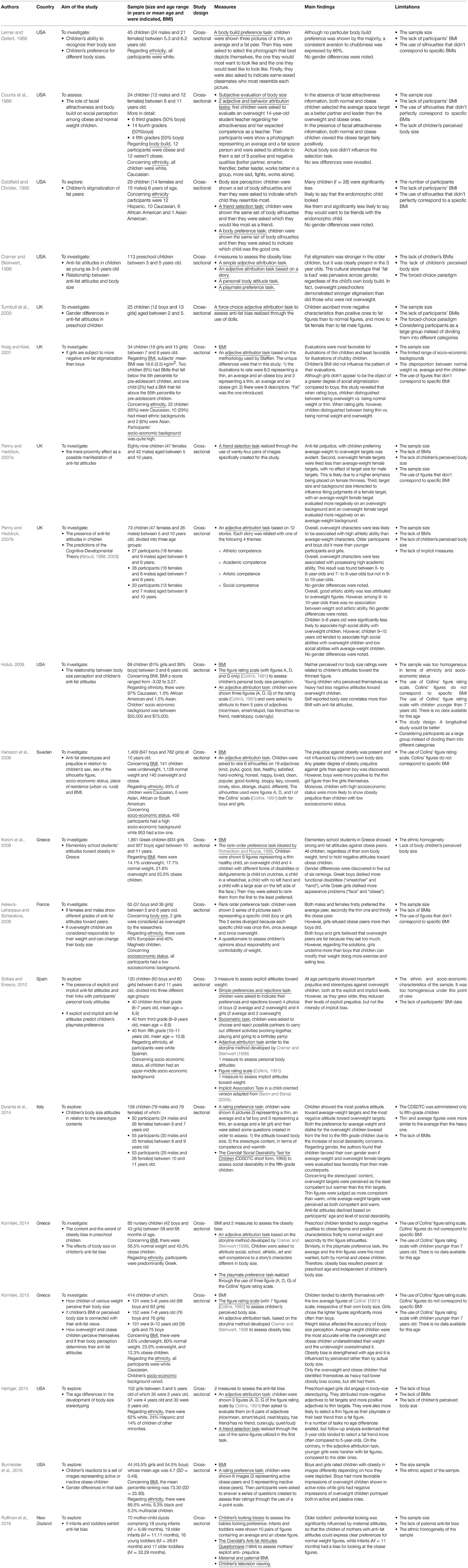

As it can be inferred from Table 1, more than half of the studies took place in Europe (n = 11), 7 in the USA and 1 in New Zealand.

The papers identified produced a sample size ranging from very small (n = 24 children, Counts et al., 1986) to large-scale studies (n = 1, 861 children, Koroni et al., 2009). The age range covered 6 months—11 years old within the articles and all but 1 study included both boys and girls. The exception was Harriger (2015) an girl-only sample.

From an ethnical point of view, the majority of the studies included above all white participants. However, other ethnicities are represented as part of the sample in 6 papers (Goldfield and Chrisler, 1995; Kraig and Keel, 2001; Holub, 2008; Askevis-Leherpeux and Schiaratura, 2009; Hansson, 2009; Harriger, 2015; Burmeister et al., 2016). All studies are cross-sectional.

Anti-fat Stigma and Body Size

The search revealed 8 papers addressing the relationship between anti-fat stigma and body size (Counts et al., 1986; Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Kraig and Keel, 2001; Holub, 2008; Hansson et al., 2009; Koroni et al., 2009; Kornilaki, 2014, 2015; Table 1).

Instruments Used

Regarding the measurement of anti-fat stigmatization, 7 out of 8 studies used an adjective attribution task (Counts et al., 1986; Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Kraig and Keel, 2001; Holub, 2008; Hansson et al., 2009; Kornilaki, 2014, 2015), 2 a playmate preference task (Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Kornilaki, 2014) 1 a rank order preference task (Koroni et al., 2009) and 1 a personal body attitude task (Cramer and Steinwert, 1998)2.

Concerning the measurement of body size, 6 studies calculated participants' BMI while one (Counts et al., 1986) evaluated children's body size by eye. Additionally, 2 also investigated children's perceived body size (Holub, 2008; Kornilaki, 2015).

Findings

Despite the sample and the methodological differences, all studies concluded that actual body size—precisely measured in terms of BMI or even calculated visually by researchers—does not affect children's anti-fat attitudes significantly. Thus, researchers who try to correlate body size and anti-fat bias discovered that overweight and obese children stigmatized their in-group peers as well as thin and average children did or even more so (Cramer and Steinwert, 1995).

However, this unexpected result appears mitigated by the conclusions reached by the two studies that added the perceived body size information to the BMI data. Interestingly, both Holub (2008) and Kornilaki (2015) found a low correlation between children's self-perceived and actual body size especially in overweight and obese children. Specifically, they discovered that the latter categories of children tended to underestimate their body size.

In particular, Kornilaki (2015) observed that the great majority of fat children considered themselves as normal (77.8%) or even thin (9.1%), with only 13.1% correctly identifying with the heaviest silhouette. Moreover, she ascertained that overweight accuracy considerably improved with age (from 11.8% at the age of 5–6 to 24.2% at the age of 9–10) but it steadily remained lower than the one reached by average peers, which went from 68.2% at the age of 5–6 to 86.8% at the age of 9–10. Thus, at every age, more than half of the overweight children identified themselves as average and stigmatized the fat silhouette as if it represented an out-group member. Only the minority of children who recognized their actual body size showed less anti-fat stigma, but still presented it.

Similar conclusions were found by Holub (2008) and stated that perceived body size is the only univariate predictor of anti-fat attitudes in overweight children.

Anti-Fat Stigma and Sex

The search revealed 13 papers addressing the relationship between anti-fat stigma and sex (Lerner and Gellert, 1969; Counts et al., 1986; Goldfield and Chrisler, 1995; Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Turnbull et al., 2000; Kraig and Keel, 2001; Penny and Haddock, 2007a,b; Askevis-Leherpeux and Schiaratura, 2009; Hansson, 2009; Koroni et al., 2009; Durante et al., 2014; Burmeister et al., 2016; Table 1).

Instruments Used

Relative to the measurement of anti-fat stigmatization 6 studies utilized an adjective attribution task (Counts et al., 1986; Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Turnbull et al., 2000; Kraig and Keel, 2001; Penny and Haddock, 2007b; Hansson, 2009), 3 a friend selection task (Goldfield and Chrisler, 1995; Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Penny and Haddock, 2007a) 2 a rank order task (Askevis-Leherpeux and Schiaratura, 2009; Koroni et al., 2009) 2 a rating preference task (Durante et al., 2014; Burmeister et al., 2016), and 3 a body size preference task (Lerner and Gellert, 1969; Goldfield and Chrisler, 1995; Cramer and Steinwert, 1998).

Regarding the measurement of body size, 3 studies calculated participants' BMI (Hansson, 2009; Koroni et al., 2009; Burmeister et al., 2016) while 2 (Counts et al., 1986; Askevis-Leherpeux and Schiaratura, 2009) evaluated children's body size visually.

Moreover, Askevis-Leherpeux and Schiaratura (2009) administered a questionnaire to assess children's opinions about responsibility and controllability of weight and Durante et al. (2014) administered The Crandall Social Desirability Test for Children (1965).

Findings

Firstly, all studies, regardless of the sample and the methodological differences, evidenced that both male and female children as young as 2 years old exhibited anti-fat attitudes toward their overweight and obese peers. Thus, the overweight or obese silhouettes/drawings/photos were overall associated with negative adjectives and less preferred as friends than the normal weight ones.

However, 5 studies found no significant differences between sexes in the degree of anti-fat attitudes shown actively by boys and girls, in the degree of anti-fat bias directed toward male and female stimuli and even in the attitudes expressed toward average and thin figures. Conversely, 8 studies identified sex differences.

In particular, 2 studies (Kraig and Keel, 2001; Hansson et al., 2009) revealed that there was a sex difference regarding the socially valued body size. In particular, Kraig and Keel (2001) noticed that girls didn't seem to be the object of a greater degree of anti-fat bias but, interestingly, when evaluating boys, children distinguished between overweight boys—who were devalued—and normal and thin males—who were both valued. Differently, when evaluating girls, children distinguished between thin peers—who were the most valued—and average and overweight females—who were more devalued.

Hansson et al. (2009), instead, found that boys rated thin girls more positively than the girls themselves did. Thus, both studies underlined the fact that boys could in some sense press girls to value being thin.

Moreover, 6 studies identified a gender difference in anti-fat bias. Turnbull et al. (2000) as well as Penny and Haddock (2007a) found that fat stigma was stronger toward female targets rather than male ones. Moreover, the second group of authors discovered another interesting trend in children, asking them to evaluate a male or female figure who was surrounded by average or overweight characters. In fact, in theory, children should not take into consideration the background characters, but in practice it emerged that the target and background size interacted and influenced judgments regarding female targets. More precisely, an average-weight female target was evaluated more negatively on an overweight background and an overweight female target was evaluated more negatively on an average-weight background.

Other authors revealed that girls exhibited higher more deeply-rooted forms of anti-fat bias than boys. Askevis-Leherpeux and Schiaratura's study (2009) showed that, although boys and girls believed that overweight peers were fat because they ate too much, girls rejected chubby peers more than boys. Moreover, females thought that losing weight depended on willpower and recommended more physical exercises to girls and dieting to boys.

Burmeister et al. (2016) demonstrated that males and females rate obese peers in various images differently depending on how they are portrayed. Specifically, while boys value more positively obese children depicted while doing dynamic activities than doing passive ones, girls are not influenced by them. This phenomenon may be explained considering that boys might have more favorable attitudes toward active overweight children because for males the thin-ideal is mixed with the muscular one. For girls, instead, independently from how they are depicted, obese children still remain obese and for this reason, deplorable.

Similar conclusions were reached by Koroni et al. (2009). These authors, asking Greek children to rank 6 figures representing a thin healthy child, an overweight child and 4 children with different forms of disabilities or disfigurements (a child on crutches, a child in a wheelchair, a child with no left hand and a child with a large scar on the left side of the face), evidenced that boys disliked more functional disabilities (“wheelchair” and “hand”), while girls disliked more appearance problems (“face” and “obese”).

Finally, Durante et al. (2014) found that usually children favored their own gender even if average-weight and overweight female targets were evaluated less favorably than their male counterparts. Thus, in-group favoritism was less evident in girls when rating both average and chubby peers.

Anti-fat Stigma and Age

Generally, all research papers may be used to analyze the relationship between anti-fat attitudes and age. However, from a more analytic point of view, 8 articles address this issue more precisely (Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Turnbull et al., 2000; Penny and Haddock, 2007b; Solbes and Enesco, 2010; Harriger, 2015; Kornilaki, 2015; Durante, 2016; Ruffman, 2016; Table 1).

Instruments Used

Concerning the measurement of anti-fat stigmatization, 6 studies utilized an adjective attribution task (Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Turnbull et al., 2000; Penny and Haddock, 2007b; Solbes and Enesco, 2010; Harriger, 2015; Kornilaki, 2015), 2 a playmate selection task (Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Harriger, 2015), 2 a personal body size attitude task (Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Solbes and Enesco, 2010), 1 a simple preferences and rejections task, a socio-metric task and the Implicit Association Task (Solbes and Enesco, 2010),1 a rating preference task and 1 a looking bias task (Ruffman, 2016).

Regarding the measurement of body size, only 1 study calculated participants' BMI (Kornilaki, 2015).

Moreover, Durante et al. (2014) administered The Crandall Social Desirability Test for Children (1965).

Findings

First, all studies evidenced the presence of anti-fat stigma, demonstrating that it is very pervasive and deeply rooted.

However, analyzing this phenomenon over time the following trend emerges:

In the first place, according to Turnbull et al. (2000) and Ruffman et al. (2016) the anti-fat attitude emerges during the second year of life. In fact, both the adjective attribution task used by the first group of authors and a looking preference task used by the second group of authors revealed this.

Regarding the age group between 3 and 5 year olds, Cramer and Steinwert (1998) recorded that both in the adjective attribution and in the playmate preference tasks fat stigmatization was stronger in older children. Contrarily, Harriger (2015), with an only-girl sample, discovered that in the adjective attribution task younger girls were harsher on fat figures compared to the older ones. However, in the friend selection task, 3-year-old girls selected fat friends more frequently than 5-year-old ones.

Concerning the age group between 5 and 10, Penny and Haddock (2007b) and Kornilaki (2015) reached opposite conclusions. Penny and Haddock found that children 5–8 were less likely to associate being overweight with athletic, artistic and social abilities. On the contrary, this phenomenon didn't emerge in children 9–10, who even tended to attribute social abilities to overweight peers. Conversely, Kornilaki revealed that obesity stigma increased with age.

Finally, concerning children between 6 and 11 both Solbes and Enesco (2010) and Durante et al. (2014) found that anti-fat stigma reduced with age. However, Durante et al. underlined that this phenomenon was directly proportional not only to age but also to the increase of social desirability. Similarly, Solbes and Enesco revealed that as children grew older, they reduced their level of explicit prejudice but not the intensity of the implicit bias.

Conclusion

Regarding the first objective of this paper, it emerged that overweight and obese children show in-group favoritism and thus less anti-fat attitudes only when they correctly perceive their actual body size (Holub, 2008; Kornilaki, 2015). However, according to Kornilaki the majority of fat children don't accurately identify their body even at 9–10 years old. Therefore, children's in-group favoritism may be a rare phenomenon.

Concerning the second aim, the question remained substantially unanswered because 5 articles posit no gender differences (Lerner and Gellert, 1969; Counts et al., 1986; Goldfield and Chrisler, 1995; Cramer and Steinwert, 1998; Penny and Haddock, 2007a) while 8 noticed that girls stigmatize more than boys and are even more often the object of fat prejudice compared to their male peers (Kraig and Keel, 2001; Askevis-Leherpeux and Schiaratura, 2009; Hansson, 2009; Koroni et al., 2009; Durante et al., 2014; Burmeister et al., 2016) However, overall, it can be noted that 4 out of the 5 studies that didn't perceive sex differences were published before 2000.

Finally, concerning the third purpose, most of the studies considered partially or fully corroborated Aboud's Cognitive-Developmental Theory (1988, 2003). In fact, in the adjective attribution task, both Cramer and Steinwert (1998) and Kornilaki (2015) noticed an intensification of the anti-fat bias between 3 and 5 years old, while in the playmate selection task only Cramer and Steinwert recognized it. Moreover, except for Kornilaki (2015), the other studies examined (Penny and Haddock, 2007b; Solbes and Enesco, 2010; Durante et al., 2014) observed an explicit decrease in anti-fat bias starting at 9 years old. However, as noticed by Penny and Haddock, this change may be ascribed to the increase of social desirability and as noticed by Solbes and Enesco, it could be only exterior but not interior.

Three among the possible future developments of this mini-review, which demonstrates the limitation of using a small number of articles written in different time periods, could be: (1) expand the research; (2) consider the effect of the research contexts on the results; (3) more deeply analyze the methodologies used and their impact on the results.

Author Contributions

RD handled the global structure of the work and the literature selection. LC collaborated in the process of literature selection.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^The decision to place the cut off at 11 years old is dictated by the desire to analyze the phenomenon before adolescence.

2. ^It's important to notice that, although the methodologies used are often nominally similar, in practice they are very heterogeneous in terms of the number of adjectives chosen, semantic field they belong to and stimulus figures utilized.

References

Aboud, F. E. (2003). The formation of in-group favoritism and out-group prejudice in young children: are they distinct attitudes? Dev. Psychol. 39, 48–60. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.48

Askevis-Leherpeux, F., and Schiaratura, L. T. (2009). Dès 5 ans, les filles rejettent lobésité. Enfance 2, 241–256. doi: 10.4074/S0013754509002067

Baron, A. S., and Banaji, M. R. (2006). The development of implicit attitudes: evidence of race evaluations from ages 6 and 10 and adulthood. Psychol. Sci. 17, 53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01664.x

Burmeister, J. M., Zbur, S., and Musher-Eizenman, D. (2016). Active versus inactive portrayals of children with obesity. Stigma Health 1, 101–108. doi: 10.1037/sah0000016

Collins, M. E. (1991). Body figure perceptions and preferences among preadolescent children. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 10, 199–208. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199103)10:2<199::AID-EAT2260100209>3.0.CO;2-D

Counts, C. R., Jones, C., Frame, C. L., Jarvie, G. J., and Struss, C. C. (1986). The perception of obesity by normal-weight versus obese school-age children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 7, 113–120.

Cramer, P., and Steinwert, T. (1998). Thin is good, fat is bad: how early does it begin? J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 19, 429–451.

Durante, F., Fasolo, M., Mari, S., and Mazzola, A. F. (2014). Children's attitudes and stereotype content toward thin, avarage-weight and overweight peers. Article 4, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/2158244014534697

Goldfield, A., and Chrisler, J. C. (1995). Body stereotyping and stigmatization of obese persons by first graders. Percept. Mot. Skills 81, 909–910. doi: 10.2466/pms.1995.81.3.909

Griffiths, L. J., Wolke, D., Page, A. S., and Horwood, J. P. (2006). Obesity and bullying: different effects for boys and girls. Arch. Dis. Child 91, 121–125. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.072314

Grossi, G., and Ruspini, E. (a cura di) (2007). Ofelia e Parsifal. Modelli e Differenze Di Genere nel Mondo Dei Media. Milano: Edizioni Libreria Cortina Milano.

Hansson, L. M., Karnehed, N., Tynelius, P., and Rasmussen, F. (2009). Prejudice against obesity among 10-year-olds: a nationwide population-based study. Acta Pediatr. 98, 1176–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01305.x

Harriger, J. A. (2015). Age differences in body size stereotyping in a sample of preschool girls. Eat. Disord. 23, 177–190. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2014.964610

Holub, S. C. (2008). Individual differences in the ant-fat attitudes of preschool-children. The importance of perceived body size. Body Image 5, 317–321. doi: 10.1016/J.bodyim.2008.03.003

Janssen, I., Craig, W. M., Boyce, W. F., and Pickett, W. (2004). Association between overweight and obesity with bullying behaviors in school-aged children. Pediatrics 113, 1187–1194.

Kornilaki, E. N. (2014). Obesity bias in preschool children: do the obese adopt anti-fat-views? Hell. J. Psychol. 11, 26–46. doi: 10.1002/icd.1894

Kornilaki, E. N. (2015). Obesity bias in children: the role of actual and perceived body size. Infant Child Dev. 24, 365–378. doi: 10.1002/icd.1894

Koroni, M., Garagouni-Areou, F., Roussi-Vergou, C. J., Zafiropoulou, M., and Piperakis, S. (2009). The stigmatization of obesity in children. A survey in Greek elementary schools. Appetite 52, 241–144. doi: 10.1016/j.appetet.2008.09.006

Kraig, K. A., and Keel, P. K. (2001). Weight-bases stigmatization in children. Int. J. Obes. 25, 1661–1666. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801813

Lerner, R. M., and Gellert, E. (1969). Body build identification, preference, and aversion in children. Dev. Psychol. 1, 456–462.

Penny, H., and Haddock, G. (2007a). Anti-fat prejudice among children: the mere proximityeffect in 5-10 years old. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 43, 678–683. doi: 10.1016/jesp.2006.07.002

Penny, H., and Haddock, G. (2007b). Children's stereotypes of overweight children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 24, 409–418. doi: 10.1348/026151006X158807

Puhl, R. M., and Latner, J. D. (2007). Stigma, Obesity, and the health of the nation's children. Psychol. Bull. 133, 557–580. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557

Richardson, S. A., and Royce, J. (1968). Race and physical handicap in children’s preference for other children. Child Dev. 39, 467–480.

Riva, C. (2012). Disturbi Alimentari E Imagine Del Corpo: La Narrazione Dei Media. Milano: Guerini Scientifica.

Ruffman, T., O'Brien, K. S., Taumoepeau, M., Latner, J. D., and Hunter, J. A. (2016). Toddlers' bias to look at average versus obese figures relates to maternal anti-fat prejudice. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1422, 195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.10.008

Schwimmer, J. B., Burwinkle, T. M., and Varni, J. W. (2003). Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 289, 18813–11819. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1813

Solbes, I., and Enesco, I. (2010). Explicit and implicit anti-fat attitudes in children and their relationship with their body images. Obes. Facts 3, 23–32. doi: 10.1159/000280417

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1986). “The social identity theory of intergroup behavior,” in Austin The Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds S. Worchel and W. Austin (Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall), 7–24.

Turnbull, J. D., Heaslip, S., and McLeod, H. A. (2000). Pre-school children's attitudes to fat and normal male and female stimulus figures. Int. J. Obes. 24, 1705–1706. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801462

Keywords: children, overweight, obesity, stigma, peer discrimination

Citation: Di Pasquale R and Celsi L (2017) Stigmatization of Overweight and Obese Peers among Children. Front. Psychol. 8:524. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00524

Received: 19 December 2016; Accepted: 22 March 2017;

Published: 20 April 2017.

Edited by:

Caroline Braet, Ghent University, BelgiumCopyright © 2017 Di Pasquale and Celsi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roberta Di Pasquale, cm9iZXJ0YS5kaS1wYXNxdWFsZUB1bmliZy5pdA==

Roberta Di Pasquale

Roberta Di Pasquale Laura Celsi

Laura Celsi