94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 25 April 2016

Sec. Quantitative Psychology and Measurement

Volume 7 - 2016 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00547

Louisa Picco1*

Louisa Picco1* Edimanysah Abdin1

Edimanysah Abdin1 Siow Ann Chong1

Siow Ann Chong1 Shirlene Pang1

Shirlene Pang1 Saleha Shafie1

Saleha Shafie1 Boon Yiang Chua1

Boon Yiang Chua1 Janhavi A. Vaingankar1

Janhavi A. Vaingankar1 Lue Ping Ong2

Lue Ping Ong2 Jenny Tay1

Jenny Tay1 Mythily Subramaniam1

Mythily Subramaniam1Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help (ATSPPH) are complex. Help seeking preferences are influenced by various attitudinal and socio-demographic factors and can often result in unmet needs, treatment gaps, and delays in help-seeking. The aims of the current study were to explore the factor structure of the ATSPPH short form (-SF) scale and determine whether any significant socio-demographic differences exist in terms of help-seeking attitudes. Data were extracted from a population-based survey conducted among Singapore residents aged 18–65 years. Respondents provided socio-demographic information and were administered the ATSPPH-SF. Weighted mean and standard error of the mean were calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Confirmatory factor analysis and exploratory factor analysis were performed to establish the validity of the factor structure of the ATSPPH-SF scale. Multivariable linear regressions were conducted to examine predictors of each of the ATSPPH-SF factors. The factor analysis revealed that the ATSPPH-SF formed three distinct dimensions: “Openness to seeking professional help,” “Value in seeking professional help,” and “Preference to cope on one's own.” Multiple linear regression analyses showed that age, ethnicity, marital status, education, and income were significantly associated with the ATSPPH-SF factors. Population subgroups that were less open to or saw less value in seeking psychological help should be targeted via culturally appropriate education campaigns and tailored and supportive interventions.

There has been a growing interest in people's attitudes toward seeking psychological help. While recent research has shown an increase in the number of people seeking help from psychological services, there is still a significant number who choose not to seek help for mental health problems. This underutilization is often related to stigma (Jorm et al., 2007; Gulliver et al., 2010), reluctance to disclose a diagnosis (Hinson and Swanson, 1993) and anticipated costs (Vogel and Wester, 2003). In addition, attitudinal barriers such as choosing to handle the problem on one's own (Rickwood et al., 2007; Gulliver et al., 2010; Chong et al., 2012b; Wilson and Deane, 2012) and thinking the problem will go away (Thompson et al., 2004; Sareen et al., 2007) further contribute to underutilization of mental health services.

Other important components which may influence help-seeking for mental health problems include the perceived helpfulness of service providers and the benefits of seeking treatment from these providers (Jorm et al., 1997a; Angermeyer et al., 1999; Rickwood et al., 2007; Rughani et al., 2011), knowledge and understanding of specific risk factors and causes of mental health problems, and attitudes toward mental illnesses (Jorm et al., 1997a,b). Individuals who held negative views about the effectiveness of mental health services were unlikely to express an intention to access such services (Bayer and Peay, 1997; Angermeyer et al., 1999). Several studies have also shown that people who have sought professional help at some time in their lives have more positive attitudes toward help-seeking than those who have not (Halgin et al., 1987; Lin and Parikh, 1999).

Whilst various attitudinal barriers to help-seeking have been identified, research has also consistently found socio-demographic factors to be associated with positive help-seeking attitudes including female gender (Fischer and Turner, 1970; Yeh, 2002; Vogel and Wester, 2003; Ang et al., 2004; Nam et al., 2010), higher socioeconomic status (Figueroa et al., 1984), and higher educational level (Sheikh and Furnham, 2000; Goh and Ang, 2007). Research has also shown there to be some subcultural factors affecting attitudes toward help-seeking (Fischer and Farina, 1995; Zhang and Dixon, 2003; Goh and Ang, 2007).

In order to better understand attitudes toward help-seeking behavior and related mental health service utilization, various conceptualizations have been adopted and applied. Fischer and Turner (1970) suggested that one's attitude toward receiving help underlies actual help-seeking behavior and this assumption has been the cornerstone of research on help-seeking attitudes. In order to determine attitudes in help-seeking, Fischer and Turner (1970) developed the 29-item Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help (ATSPPH) scale, the most widely used contemporary assessment of help-seeking attitudes. The ATSPPH has consistently shown to have acceptable psychometric properties in a range of samples and the scale has been used extensively in both Western and Eastern settings (Fischer and Farina, 1995; Razali and Najib, 2000; Sheikh and Furnham, 2000; Nam et al., 2010).

This is to our knowledge, the only standardized instrument to access attitudes toward help-seeking that has been both psychometrically examined and used in a sizeable number of studies. Whilst there are a few similar measures, such as the Inventory of Attitudes toward Seeking Mental Health Services (Mackenzie et al., 2004) and the Willingness to Seek Help Questionnaire (Cohen, 1999) these are used far less frequently and have their limitations, including a lack of brevity, inability to assess constructs that are focused on global treatment attitudes, availability of limited psychometric data and they are often not generalizable as they have been validated in specific populations such as students (Kushner and Sher, 1989; Komiya et al., 2000; Mackenzie et al., 2004; Elhai et al., 2008). The authors subsequently developed a shortened uni-dimensional 10-item scale (ATSPPH-SF) which has also been extensively used (Fischer and Farina, 1995). This shortened version similarly has documented psychometric support (Fischer and Farina, 1995; Komiya et al., 2000; Vogel et al., 2005; Elhai et al., 2008).

There have been a few studies that have explored the factor structure of the ATSPPH-SF, with mixed findings. One study among college students and primary care patients found the ATSPPH-SF scale to have a two factor model (Elhai et al., 2008), while a local study conducted in Singapore among trainee teachers and undergraduate teachers found that removing one item and having a 9-item uni-dimensional scale, produced the best fit (Ang et al., 2007). To date, the majority of research using the ATSPPH or ATSPPH-SF scale has focused on specific population sub-groups such as students or teachers, and whilst several studies have looked at Asian populations, the majority of these have been Asians living in Western countries. The gaps in the existing literature warrant the need for multi-ethnic population based research studies which explore ATSPPH. Furthermore, having a greater understanding of attitudes toward help-seeking is imperative as these attitudes have the potential to be mutable, in facilitating individuals' access to treatment (Bhugra and Hicks, 2004).

Singapore is a multi-ethnic country in Southeast Asia, and in 2015, the resident population was 3.9 million, comprising predominantly of Chinese, Malays, and Indians (Department of Statistics, 2015). Ang et al. (2004) explored the effects of gender and sex role orientation on ATSPPH among student trainee teachers in Singapore. They found females had more positive overall attitudes toward professional help-seeking and were more willing to recognize a personal need for professional help compared to males.

Another local study investigated the extent to which people prefer to seek professional help and whether they actually sought professional help for their mental or emotional problems (Ng et al., 2003). Findings revealed that only 37% of the general population would seek professional help if they experienced a serious emotional or mental problem. The authors concluded that while psychiatric disturbance was the most important factor determining mental health service use, attitudes toward seeking professional help were an important enabling factor of utilization and this apparent lack of acceptance contributes to unmet needs. The aims of the current study were to firstly explore the factor structure of the ATSPPH-SF scale among the multi-ethnic general population in Singapore and secondly, determine whether any significant socio-demographic differences exist in terms of help-seeking attitudes.

Data from the current study came from a larger comprehensive, population-based, cross-sectional mental health literacy survey conducted between March 2014 and April 2015 among Singapore citizens and Permanent Residents aged 18–65 years, who were residing in Singapore during the survey period. Respondents were randomly selected via a national registry that maintains the names and socio-demographic details such as age, gender, ethnicity, and household addresses of all residents in Singapore. Residents living outside of Singapore, those who were unable to be contacted due to incomplete or incorrect addresses and those who were unable to complete the interview in one of the specified languages were excluded from the survey. Trained interviewers administered the questionnaire in English, Mandarin, Malay, or Tamil, based on the respondent's preference. A total of 3006 people completed the face-to-face interview, equating to an overall response rate of 71.1%.

The study was approved by the relevant institutional and ethics committee (National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board). All respondents provided written informed consent and for those aged below 21 years, written informed consent was also obtained from their legally acceptable representative, parent, or guardian. Additional information pertaining to the methods and procedures is described elsewhere (Subramaniam et al., 2016).

The 10-item ATSPPH-SF (Fischer and Farina, 1995) was used to measure general ATSPPH for mental health issues. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (3 = Agree, 0 = Disagree), where items 2, 4, 8, 9, and 10 are reverse scored. Scores are then summed together, with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes toward seeking professional help. The correlation between the 10-item short form and the original 29-item scale was 0.87 (Fischer and Farina, 1995).

Socio-demographic information relating to the participants was also collected using a structured questionnaire and included age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, educational status, and income.

Cognitive interviews were conducted with 75 lay members of the population to ensure the items and terminology used in the ATSPPH-SF scale was understood as intended. This cognitive model was applied in a manner that is designed to ultimately improve the quality of survey questions through the study of comprehension, retrieval, judgment, and response processes (Willis, 2004). Respondents were instructed by trained interviewers who systematically probed on whether they could repeat the questions and what came to their mind when they heard a particular phrase or term and they were asked how they decided on their response. Respondents also reported any word they did not understand and any word or expression that they found offensive or unacceptable; and where alternative words or expressions exist for one item or expression, the respondent was asked which of the alternatives conforms better to their usual language. Minor changes were made to the ATSPPH-SF scale, to improve cultural understanding, after seeking permission from the developer (Edward. H. Fischer).

All estimates were weighted to adjust for over sampling and post-stratified for age and ethnicity distributions between the survey sample and the Singapore resident population in the year 2012. Weighted mean and standard error of the mean were calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) were performed to establish the validity of the factor structure of the ATSPPH-SF scale. CFA models were estimated to test the one and two factor structure model proposed previously by Ang et al. (2007) and Elhai et al. (2008), among the whole sample, however this resulted in a poor model fit. We therefore re-analyzed the data using EFA, among a random half of the sample (n = 1500), in order to identify the number of underlying factors, with all rotated loadings freely estimated using oblique Geomin rotation method. This was followed by CFA (n = 1502) to confirm the factor structure yielded by EFA with the second half of the sample (Neumann et al., 2008). Several criteria were used to determine the number of factors such as eigenvalue-based procedures including the number of eigenvalues >1.0 and scree plot, pattern of loadings on each factor (i.e., number of non-loading or double-loading items), and interpretability of each solution.

All structural equation modeling analyses were performed on polychoric correlation matrixes using Mplus version 7.0 with the weighted least squares with mean and variance adjusted chi-square statistic (WLSMV) estimator for categorical variables. The WLSMV estimation was used due to fact that this estimator is more suited to the ordered-categorical nature of Likert scales than traditional maximum likelihood estimation (Beauducel and Herzberg, 2006).

We used several criteria to determine the best fit model. We chose 0.4 as a cutoff for size of loading to be interpreted (Brown, 2006). Overall model fit was measured using a range of goodness-of-fit statistics based on the following criteria: the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Cutoff values suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) were used—a cutoff value of close to 0.08 for SRMR, close to 0.95 for TLI and CFI, and values smaller than 0.08 or 0.06 for the RMSEA support respectively acceptable and good model fit (Browne and Cudeck, 1993). We calculated the reliability of the scale using Composite Reliability Index (CRI) based on CFA measurement parameters.

where is the squared sum of unstandardized factor loadings, and Σθii is the sum of unstandardized measurement error variances (Raykov, 1997, 2004; Brown, 2006).

We also conducted separate multivariable linear regressions to examine factors associated with each of the ATSPPH-SF scores (dependent variables) to examine which of the following dummy coded variables (independent variables) predicted the ATSPPH-SF scores: age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, and income.

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample (n = 3006). The mean age of the respondents was 40.9 years. About 50.9% of the respondents were males, 74.7% were Chinese, 12.8% were Malays, 9.1% were Indians, and 3.3% belonged to other ethnic groups.

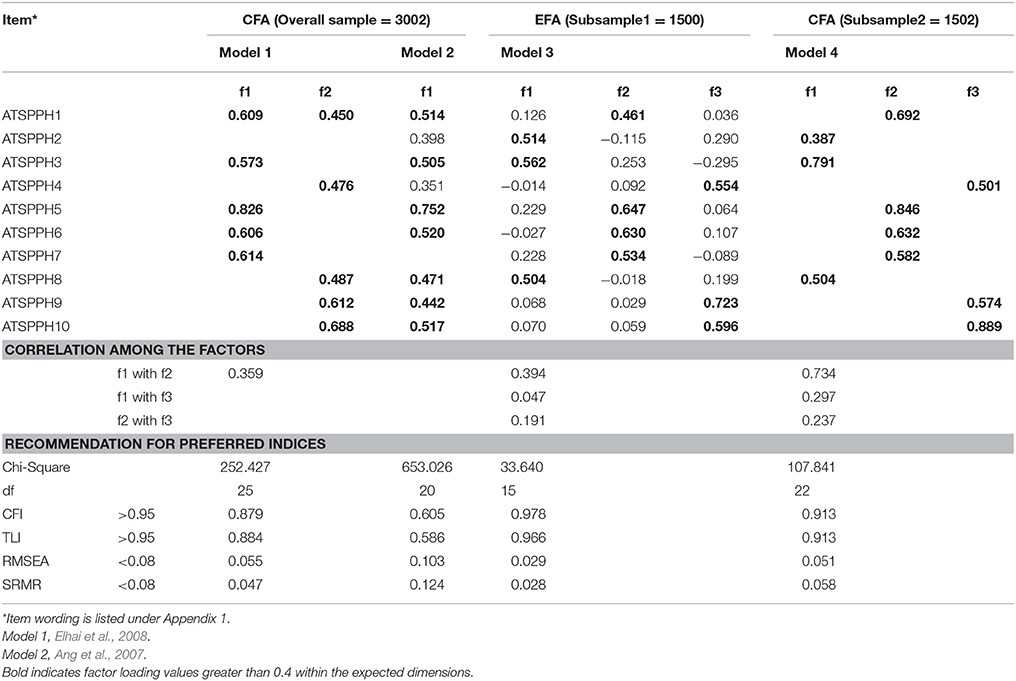

Table 2 provides the factor loadings and model fits for the CFA and EFA models of the ATSPPH-SF scale. First we examined a two factor structure for the ATSPPH-SF as proposed by Elhai et al. (2008) using CFA (Model 1). Although this model indicated higher factor loadings (all loadings above 0.4), the fit indices were poor especially for CFI and TLI indices [ = 252.427(25), CFI = 0.879, TLI = 0.884, RMSEA = 0.055, SRMR = 0.047]. We also examined the nine item uni-dimensional model suggested by Ang et al. (2007) however found that this had poor factor loadings and fit indices (Model 2). Therefore, we decided to further analyse using EFA. In EFA, a three factor structure provided a good fit, 33.64(15), CFI = 0.978, TLI = 0.966, RMSEA = 0.029, SRMR = 0.028, with high factor loadings (Model 3). Inspection of eigenvalues >1.0 and scree plot supported the three factor solution. The findings from the factor analysis revealed that the ATSPPH-SF scale formed three distinct dimensions comprising “Openness to seeking professional help,” “Value in seeking professional help,” and “Preference to cope on one's own.” Following this, we then used CFA to confirm this new structure (Model 4). The CRI for the overall scale as well as for the “Openness to seeking professional help,” “Value in seeking professional help,” and “Preference to cope on one's own” dimensions were 0.97, 0.88, 0.88, and 0.86, respectively.

Table 2. Factor loadings and model fits for the CFA and EFA models of the 10-item Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale.

Table 3 shows the socio-demographic correlates of ATSPPH-SF factor scores calculated by summing items with substantial loadings (>0.30) derived from the EFA Model 3. Multiple linear regression analyses revealed that age, ethnicity, marital status, education, and income were significantly associated with the ATSPPH-SF factors. Those aged 18–34 years and never married, were significantly associated with higher “Openness to seeking professional help,” while Malay ethnicity and lower education were significantly associated with lower openness scores. Both Malay and Indian ethnicity, secondary/O and N level education and A level/diploma, were significantly associated with lower “Value in seeking professional help” scores, while lower education and having an income of $SGD2000-5999 were significantly associated with higher “Preference to cope on one's own” scores.

This study examined the factor structure of the ATSPPH-SF scale and determined the socio-demographic differences relating to ATSPPH. EFA revealed that the ATSPPH-SF scale comprised three distinct components; the first relates to openness to seeking professional help for psychological or emotional problems, the second is about the value in seeking professional help, while the third relates to coping on one's own and choosing not to seek psychological help. It was evident that EFA supports this three factor structure given the good fit, high factor loading as well a good reliability. CFA also confirmed an acceptable model fit with CFI and TLI cut offs being above 0.95 (Bentler, 1990), while the RMSEA cut off was below 0.8. Further research to reconfirm this factor structure in an external dataset is warranted.

This is somewhat different to previous research which has found two distinct factors comprising “Openness to Seeking Treatment for Emotional Problems,” and “Value and Need in Seeking Treatment” (Elhai et al., 2008) among a college student and medical patient population in the USA. It is also different from that associated with the original ATSPPH-SF which had a one factor structure (Fischer and Farina, 1995). In a study among trainee teachers and undergraduate students in Singapore, Ang et al. (2007) also tested the uni-dimensional factor structure of the ATSPPH-SF scale using CFA. In both population subgroups they found item 7, “A person with an emotional problem is not likely to solve it alone; he or she is more likely to solve it with professional help” to be problematic, due to the double-barreled nature of the question. Due to the problematic wording and poor factor loading, the item was dropped and CFA revealed a very good fit for a uni-dimensional, 9-item scale; however when this model was applied to the general Singapore population used in our study, the factor loading and fit indices were poor. The small sample size used by Ang et al. (2007), which was specific to student and trainee teacher populations could explain the differences in factor structures between this and our study, which used a large generalizable, multi-ethnic sample.

Among the three factor ATSPPH-SF scale, we found various socio-demographic correlates associated with each factor. Firstly younger age (18–34 years) was significantly associated with increased openness to seek professional psychological help. The research to date has shown that age related differences in help-seeking attitudes are inconsistent. Older adults have been known to display negative attitudes to help-seeking (Estes, 1995; Segal et al., 2005) and whilst there can be multiple barriers to seeking professional help, actual attitudes of older adults are seen to be the most significant (Currin et al., 1998; Hatfield, 1999). Contrary to this, other studies have shown older adults' attitudes toward seeking help are generally positive (Robb et al., 2003). Given these inconsistencies, there is a need to further explore the impact of age on openness to seeking psychological help and help-seeking attitudes in general.

Interestingly we found there to be no gender differences in relation to any of the three ATSPPH-SF factors. The extant literature has shown that females are significantly more likely to have positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, compared to their male counterparts (Fischer and Turner, 1970; Yeh, 2002; Addis and Mahalik, 2003; Vogel and Wester, 2003; Ang et al., 2004; Nam et al., 2010). There is however some evidence which supports the lack of gender differences with regards to ATSPPH, which has largely come from studies among Asian Americans and Asian international students (Atkinson et al., 1995; Zhang and Dixon, 2003) which may suggest that ethnic or cultural differences may intersect with gender differences and influence help-seeking attitudes.

The literature has shown that various ethnic groups differ widely in relation to help-seeking patterns, utilization and attitudes toward mental health services (Bayer and Peay, 1997; Van OS et al., 1997) and therefore it was not surprising to find ethnic differences in relation to ATSPPH in our study. Malays were significantly less likely to be open to seeking psychological help, whilst both Malays and Indians were less likely to value seeking psychological help. These findings can be explained by various influencing factors.

The first relates to religion. A study conducted in Malaysia examining the impact of culture on illness perceptions and help-seeking behaviors among Chinese and Malays found cultural differences, whereby Malays endorsed religious attributions and help-seeking behaviors such as prayer and seeking traditional treatment from “bomohs” (traditional healers), more than Chinese (Edman and Koon, 2000). These findings are also similar to those of Hatfield et al. (1996) which found the value of Islamic prayer to be an important way of seeking help for mental illness and could therefore explain the ethnic differences observed in our study. The second is in relation to illness attribution. Help-seeking attitudes are often linked to illness attributions, where mental illnesses are often attributed to supernatural causes by Indians and Malays (Razali et al., 1996; Banerjee and Roy, 1998; Sheikh and Furnham, 2000) which may influence their help-seeking attitudes. Finally, the third is in relation to cultural and family influences. Research has consistently shown that Asians prefer to seek help from less formal sources such as family for mental health problems (Lin et al., 1982; Leong, 1986; Atkinson et al., 1995; Yeh, 2002). Alternatively, it could be the family that decides where further help should be sought (Lin and Cheung, 1999; Razali and Najib, 2000); these preferences and influences are likely to explain why Malays and Indians see less value in seeking professional psychological help.

Stigma associated with seeking psychological help could also be an underlying factor. In a recent study among the same population, which examined the extent and correlates of stigma toward people with mental illness, the authors found that those of Malay and Indian ethnicity were significantly more likely to perceive those with a mental illness to be “weak not sick” (Subramaniam et al., 2016). Given that people with a mental illness were characterized as having a weakness, under the control of the person, rather than a real medical problem, this may affect their openness to and value in seeking psychological help.

Marital status has been shown to be a predictor of ATSPPH and in our study we found that those who were never married were more open to seeking professional help. Difficulties forming or maintaining relationships and lack of social support from a partner may be strong impetuses for those not married to be more open to seeking help (Leaf et al., 1988; Gallo et al., 1995). Marital status could also be related to age, whereby younger people are less likely to be married and were also found to be more open to seeking professional help.

Lower education has consistently been associated with negative ATSPPH (Sheikh and Furnham, 2000; Al-Krenawi et al., 2004; Goh and Ang, 2007), a finding which is consistent with our study where we found lower education was associated with less openness to and value in seeking psychological professional help. Our findings suggest that respondents with higher education viewed psychological help-seeking more favorably, which can be explained by having greater knowledge of psychological help-seeking options and/or the associated benefits of such treatments. Interestingly, lower education was also significantly associated with increased self-coping or a greater preference to cope on one's own and again this may be due to limited knowledge or understanding about the benefits of seeking professional psychological help.

The findings from our study should be viewed in light of the following limitations. Whilst we looked at various socio-demographic predictors of ATSPPH, we did not explore other characteristics such as prior contact with or exposure to mental health services. Whilst the differences in attitudes were determined using multiple logistic regression, further examination or alternative analyses such as multi-group CFA or latent mean differences are recommended in the future. Furthermore, as the current study focused on attitudes in relation to seeking professional psychological help, there is a need for future research to examine whether attitudes are indeed associated with actual utilization of and satisfaction with services. Finally, the reliance on self-report by the respondents has the possibility of social desirability bias, especially since the questions measured ATSPPH.

This study, among a nationally representative sample, with a response rate of 71%, has indicated various socio-demographic correlates related to ATSPPH including age, ethnicity, marital status, and education. Given that there is a tremendous treatment gap associated with mental illnesses in Singapore (Chong et al., 2012a), there is a need to further investigate the associations between help-seeking attitudes and actual help-seeking behavior. Research exploring the effects of culture, religion, and ethnicity on help-seeking attitudes to gain a greater understanding of how these complex and inter-related constructs influence and impact help-seeking attitudes, is also warranted. As ethnicity was a significant correlate of help-seeking attitudes, where Malays and Indians were less open to seeking professional help and saw less value in such help, culturally appropriate education efforts to highlight and inform these population sub-groups about professional psychological and the benefits of such treatment, are required. These findings also have important implications in terms of service planning and increasing utilization; given that those with less education had a greater preference to cope on one's own, there is a need to improve outreach and encourage help-seeking from professional psychological services, via tailored and supportive interventions.

In view of the detrimental effects associated with under-utilization, treatment delays, and gaps in mental healthcare delivery, there is a need to address and gain a greater understanding about help-seeking attitudes, behaviors, and preferences for people with a mental illness. Researchers have sought to explain underutilization of professional psychological services among Asian populations and three major reasons have been postulated: (1) lack of trust in helping professionals and their services (Nu, 1987; Pan, 1996); (2) lack of knowledge about the availability of services (Leong, 1986); and the stigma associated with formal help-seeking (Leong, 1986; Mau and Jepsen, 1988). Exploring these potential barriers within the Singapore context could help to improve and change help-seeking attitudes and behaviors in the future.

LP was involved with the study design, collected, and verified data and wrote the manuscript. EA was involved in the data analysis and interpretation and provided inputs into the manuscript. SAC assisted in study design, interpreted the data, and provided intellectual inputs on the manuscript. SP, SS, BYC, JV played an active role in data collection, clean up, refining analysis plan, and drafting the manuscript. LPO provided clinical inputs and interpretations into the findings and provided inputs and edits to the manuscript. JT was involved with the study design and provided inputs into the manuscript. MS supervised the overall study design, provided inputs on the manuscript content, and approved the manuscript version to be published.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported by Singapore Ministry of Health's National Medical Research Council under its Health Services Research Competitive Research Grant (Grant number HSRG/0036/2013). We would like to acknowledge Professor Fischer who was one of the developers of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help scale who was agreeable for adaptations to be made to the scale where needed.

Addis, M. E., and Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am. Psychol. 58, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.5

Al-Krenawi, A., Graham, J. R., Dean, Y. Z., and Eltaiba, N. (2004). Cross-national study of attitudes towards seeking professional help: Jordan, United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Arabs in Israel. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 50, 102–114. doi: 10.1177/0020764004040957

Ang, R. P., Lau, S., Tan, A. I., and Lim, K. M. (2007). Refining the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale: factorial invariance across two Asian samples. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 40, 130–141.

Ang, R. P., Lim, K. M., Tan, A. G., and Yau, T. Y. (2004). Effects of gender and sex role orientation on help-seeking attitudes. Curr. Psychol. 23, 203–214. doi: 10.1007/s12144-004-1020-3

Angermeyer, M. C., Matschinger, H., and Riedel-Heller, S. G. (1999). Whom to ask for help in case of mental disorder? Preferences of the lay public. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 34, 202–210. doi: 10.1007/s001270050134

Atkinson, D. R., Lowe, S., and Matthews, L. (1995). Asian American acculturation, gender, and willingness to seek counseling. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 23, 130–138. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.1995.tb00268.x

Banerjee, G., and Roy, S. (1998). Determinants of help-seeking behaviour of families of schizophrenic patients attending a teaching hospital in India: an indigenous explanatory model. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 44, 199–214. doi: 10.1177/002076409804400306

Bayer, J. K., and Peay, M. Y. (1997). Predicting intention to seek help from professional mental health services. Aust. N.Z. J. Psychiatry 31, 504–513. doi: 10.3109/00048679709065072

Beauducel, A., and Herzberg, P. Y. (2006). On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Struct. Equ. Modeling 13, 186–203. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Bhugra, D., and Hicks, M. H. R. (2004). Effect of an educational pamphlet on help-seeking attitudes for depression among British South Asian women. Psychiatr. Serv. 55, 827–829. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.827

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1993). “Alternative ways of assessing model fit,” in Testing Structural Equation Models, eds K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (Newbury Park, CA: Sage), 136–162.

Chong, S. A., Abdin, E., Sherbourne, C., Vaingankar, J., and Heng, D. (2012a). Treatment gap in common mental disorders: the Singapore perspective. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 21, 195–202. doi: 10.1017/S2045796011000771

Chong, S. A., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J. A., Kwok, K. W., and Subramaniam, M. (2012b). Where do people with mental disorders in Singapore go to for help? Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore 41, 154–160.

Cohen, B. (1999). Measuring the willingness to seek help. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 26, 67–83. doi: 10.1300/J079v26n01_04

Currin, J. B., Hayslip, B. Jr., Schneider, L. J., and Kooken, R. A. (1998). Cohort differences in attitude toward mental heath services among older persons. Psychotherapy 4, 507–518.

Department of Statistics (2015). Population and Population Structure. Available online at: http://www.singstat.gov.sg/statistics/browse-by-theme/population-and-population-structure (Accessed November 06, 15).

Hinson, J. A., and Swanson, J. L. (1993). Willingness to seek help as a function of self-disclosure and problem severity. J. Couns. Dev. 71, 465–470. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1993.tb02666.x

Edman, J. L., and Koon, T. Y. (2000). Mental illness beliefs in Malaysia: ethnic and intergenerational comparisons. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 46, 101–109. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600203

Elhai, J. D., Schweinle, W., and Anderson, S. M. (2008). Reliability and validity of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form. Psychiatry Res. 159, 320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.020

Estes, C. L. (1995). “Mental health services for the elderly: key policy elements,” in Emerging Issues in Mental Health and Aging, ed M. Gatz (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 303–328.

Figueroa, R. H., Calhoun, J. R., and Ford, R. (1984). Student utilization of university psychological services. Coll. Stud. J. 18, 186–196.

Fischer, E. H., and Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: a shortened form and considerations for research. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 36, 368–373.

Fischer, E. H., and Turner, J. L. (1970). Orientations to seeking professional help: development and research utility of an attitudes scale. J. Couns. Clin. Psychol. 35, 79–90. doi: 10.1037/h0029636

Goh, D. P., and Ang, R. P. (2007). An introduction to association rule mining: an application in counseling and help-seeking behaviour of adolescents. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 259–266. doi: 10.3758/BF03193156

Halgin, R. P., Weaver, D. D., Edell, W. S., and Spencer, P. G. (1987). Relation of depression and help-seeking to attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. J. Couns. Psychol. 34, 177–185. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.34.2.177

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Gallo, J. J., Marino, S., Ford, D., and Anthony, J. C. (1995). Filters on the pathway to mental health care, II: sociodemographic factors. Psychol. Med. 25, 1149–1160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033122

Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., and Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 10:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

Hatfield, A. B. (1999). Barriers to serving older adults with a psychiatric disability. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 22, 270–276. doi: 10.1037/h0095234

Hatfield, B., Mohamad, H., Rahim, Z., and Tanweer, H. (1996). Mental health and the Asian communities: a local survey. Br. J. Soc. Work 26, 315–336. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a011098

Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., and Pollitt, P. (1997a). Mental health literacy: a survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med. J. Aust. 166, 182–186.

Jorm, A. F., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., and Pollitt, P. (1997b). Public beliefs about causes and risk factors for depression and schizophrenia. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 32, 143–148.

Jorm, A. F., Wright, A., and Morgan, A. J. (2007). Where to seek help for a mental disorder? National survey of the beliefs of Australian youth and their parents. Med. J. Aust. 187, 556–560.

Komiya, N., Good, G. E., and Sherrod, N. B. (2000). Emotional openness as a predictor of college students' attitudes toward seeking psychological help. J. Couns. Psychol. 47, 138–143. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.138

Kushner, M. G., and Sher, K. J. (1989). Fears of psychological treatment and its relation to mental health service avoidance. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 20, 251–257. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.20.4.251

Leong, F. T. L. (1986). Counseling and psychotherapy with Asian Americans: review of the literature. J. Couns. Psychol. 33, 196–206. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.33.2.196

Leaf, P. J., Bruce, M. L., Tischler, G. L., Freeman, D. H. Jr., Weissman, M. M., and Myers, J. K. (1988). Factors affecting the utilization of specialty and general medical mental health services. Med. Care 26, 9–26. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198801000-00002

Lin, E., and Parikh, S. V. (1999). Sociodemographic, clinical and attitudinal characteristics of the untreated depressed in Ontario. J. Affect. Disord. 53, 153–162. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00116-5

Lin, K. M., and Cheung, F. (1999). Mental health issues for Asian. Am. Psychiatr. Serv. 50, 774–780.

Lin, K. M., Inui, T. S., Klienman, A. K., and Womack, W. M. (1982). Sociocultural determinants of help-seeking behaviour of patients with mental illness. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 170, 78–85. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198202000-00003

Mackenzie, C. S., Knox, V. J., Gekoski, W. L., and Macaulay, H. L. (2004). An adaptation and extension of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help scale. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 34, 2410–2435. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01984.x

Mau, W. C., and Jepsen, D. A. (1988). Attitudes towards counselors and counseling processes: a comparison of Chinese and American graduate students. J. Couns. Dev. 67, 189–192. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1988.tb02090.x

Nam, S. K., Chu, H. J., Lee, M. K., Lee, J. H., Kim, N., and Lee, S. M. (2010). A meta-analysis of gender differences in attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. J. Am. Coll. Health 59, 110–116. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.483714

Neumann, C. S., Malterer, M. B., and Newman, J. P. (2008). Factor structure of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI): findings from a large incarcerated sample. Psychol Assess. 20, 169–174. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.169

Ng, T. P., Fones, C. S. L., and Kua, E. H. (2003). Preference, need and utilization of mental health services, Singapore National Mental Health Survey. Aust. N.Z. J. Psychiatry 37, 613–619. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01233.x

Nu, G. (1987). Meaning and function of counseling work at a university counseling center in Taiwan. Guid. Quart. 20, 2–7.

Pan, T. (1996). Difficulties with and solutions of counseling at university counseling centers in Taiwan. Guid. Quart. 22, 2–9.

Raykov, T. (1997). Scale reliability, Cronbach's coefficient alpha, and violations of essential tau-equivalence with fixed congeneric components. Multivariate Behav. Res., 32, 329–353. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3204_2

Raykov, T. (2004). Behavioral scale reliability and measurement invariance evaluation using latent variable modeling. Behav. Ther. 35, 299–331. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80041-8

Razali, S. M., Khan, U. A., and Hasanah, C. I. (1996). Belief in supernatural causes of mental illness among Malay patients: impact on treatment. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 94, 229–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09854.x

Razali, S. M., and Najib, M. A. M. (2000). Help-seeking pathways among Malay psychiatric patients. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 46, 281–288. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600405

Rickwood, D., Deane, F. P., and Wilson, C. (2007). When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Med. J. Aust. 187, S35–S39.

Robb, C., Haley, W. E., Becker, M. A., Polivka, L. A., and Chwa, H.-J. (2003). Attitudes towards mental health care in younger and older adults: similarities and differences. Aging Ment. Health 7, 142–152. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000072321

Rughani, J., Deane, F. P., and Wilson, C. J. (2011). Rural adolescents' help-seeking intentions for emotional problems: the influence of perceived benefits and stoicism. Aust. J. Rural Health 19, 64–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01185.x

Sareen, J., Jagdeo, A., Cox, B. J., Clara, I., ten Have, M., Belik, S., et al. (2007). Perceived barriers to mental health service utilization in the United States, Ontario, and The Netherlands. Psychiatr. Serv. 58, 357–364. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.357

Segal, D. L., Mincic, M. S., Coolidge, F. L., and O'Riley, A. (2005). Beliefs about mental illness and willingness to seek help: a cross-sectional study. Aging Ment. Health 9, 363–367.

Sheikh, S., and Furnham, A. (2000). A cross-cultural study of mental health beliefs and attitudes towards seeking professional help. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 35, 326–334. doi: 10.1007/s001270050246

Subramaniam, S., Abdin, E., Picco, L., Pang, S., Shafie, S., Vaingankar, J. A., et al. (2016). Stigma towards people with mental disorders and its components - a perspective from multi-ethnic Singapore. Epidemiol. Psychiatric Sci. 1, 1–12. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000159

Thompson, A., Hunt, C., and Issakidis, C. (2004). Why wait? Reasons for delay and prompts to seek help for mental health problems in an Australian clinical sample. Social Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 39, 810–817. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0816-7

Van OS, J., McKenzie, K., and Jones, P. (1997). Cultural differences in pathways to care, service use and treated outcomes. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 10, 178–182.

Vogel, D. L., and Wester, S. R. (2003). To seek help or not to seek help: the risks of self-disclosure. J. Couns. Psychol. 50, 351–361. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.50.3.351

Vogel, D. L., Wester, S. R., Wei, M., and Boysen, G. A. (2005). The role of outcome expectations and attitudes on decisions to seek professional help. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 459–470. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.459

Willis, G. B. (2004). Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design, 1st Edn. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Wilson, C. J., and Deane, F. P. (2012). Brief Report: need for autonomy and other perceived barriers relating to adolescents' intentions to seek professional mental health care. J. Adolesc. 35, 233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.06.011

Yeh, C. J. (2002). Taiwanese students' gender, age, interdependent and independent self-construal, and collective self-esteem as predictors of professional psychological help-seeking attitudes. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 8, 19–29. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.1.19

Zhang, N., and Dixon, D. N. (2003). Acculturation and attitudes of Asian international students toward seeking psychological help. J. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 31, 205–222. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2003.tb00544.x

1. If I thought I was having a mental breakdown, my first thought would be to get professional attention.

2. Talking about problems with a psychologist seems to me as a poor way to get rid of emotional problems.

3. If I were experiencing a serious emotional crisis, I would be sure that psychotherapy would be useful.

4. I admire people who are willing to cope with their problems and fears without seeking professional help.

5. I would want to get psychological help if I were worried or upset for a long period of time.

6. I might want to have psychological counseling in the future.

7. A person with an emotional problem is not likely to solve it alone; he or she is more likely to solve it with professional help.

8. Given the amount of time and money involved in psychotherapy, I am not sure that it would benefit someone like me.

9. People should solve their own problems, therefore, getting psychological counseling would be their last resort.

10. Personal and emotional troubles, like most things in life, tend to work out by themselves.

Keywords: attitudes, psychological help-seeking, mental illness, Singapore

Citation: Picco L, Abdin E, Chong SA, Pang S, Shafie S, Chua BY, Vaingankar JA, Ong LP, Tay J and Subramaniam M (2016) Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help: Factor Structure and Socio-Demographic Predictors. Front. Psychol. 7:547. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00547

Received: 15 December 2015; Accepted: 01 April 2016;

Published: 25 April 2016.

Edited by:

Pietro Cipresso, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, ItalyReviewed by:

Carol Van Hulle, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USACopyright © 2016 Picco, Abdin, Chong, Pang, Shafie, Chua, Vaingankar, Ong, Tay and Subramaniam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Louisa Picco, bG91aXNhX3BpY2NvQGltaC5jb20uc2c=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.