94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol., 17 November 2015

Sec. Psychology for Clinical Settings

Volume 6 - 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01756

This study investigated the impact of violent experiences during childhood, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and appetitive aggression on everyday violent behavior in Burundian females with varying participation in war. Moreover, group differences in trauma-related and aggression variables were expected. Appetitive aggression describes the perception of violence perpetration as fascinating and appealing and is a common phenomenon in former combatants. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 158 females, either former combatants, supporters of armed forces or civilians during the civil war in Burundi. The PTSD Symptom Scale Interview was used to assess PTSD symptom severity, the Appetitive Aggression Scale to measure appetitive aggression and the Domestic and Community Violence Checklist to assess both childhood maltreatment and recent aggressive behavior. Former combatants had experienced more traumatic events, perpetrated more violence and reported higher levels of appetitive aggression than supporters and civilians. They also suffered more severely from PTSD symptoms than civilians but not than supporters. The groups did not differ regarding childhood maltreatment. Both appetitive aggression and childhood violence predicted ongoing aggressive behavior, whereas the latter outperformed PTSD symptom severity. These findings support current research showing that adverse childhood experiences and a positive attitude toward aggression serve as the basis for aggressive behavior and promote an ongoing cycle of violence in post-conflict regions. Female members of armed groups are in need of demobilization procedures including trauma-related care and interventions addressing appetitive aggression.

Even several years after the establishment of peace, the inhabitants in post-conflict regions still struggle with the aftermath of war. Poverty, poor health, lack of security, and high rates of violence pose major challenges to both the individual and the overarching society (Saile et al., 2014). War-affected individuals often contend with significant mental health complications. In line with the building block effect, i.e., mental ill-health due to cumulative exposure to traumatic stressors (Neuner et al., 2004), prevalence rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in war-affected populations are severely elevated (e.g., Steel et al., 2002; Karunakara et al., 2004; Nandi et al., 2015). In addition, a growing body of research demonstrates a link between traumatization and enhanced aggressive behavior in military personnel that continues after deployment (Byrne and Riggs, 1996; Morland et al., 2012; MacManus et al., 2013). For some individuals returning from combat, PTSD symptoms, such as hyperarousal and angry outbursts, are exhibited in violent behavior (Galovski and Lyons, 2004; Orth and Wieland, 2006).

Though high rates of PTSD are present among former combatants, hyperarousal cannot fully account for the high prevalence of violence observed in post-war societies. In fact, Elbert et al. (2010) postulated that active combatants and child soldiers might perceive the perpetration of brutal aggressive acts as appealing and intrinsically rewarding. This perception of violence as exciting, i.e., appetitive aggression, has been reported by a variety of combatants in different post-conflict regions. Several studies suggest that appetitive aggression helps combatants maintain functionality and cope with trauma-related mental health symptoms in life threatening and violent environments (e.g., Hecker et al., 2012; Weierstall et al., 2013a,b). While developing appetitive aggression in such adverse environments seems to be beneficial in order to regain feelings of power and control, it most likely also enhances the likelihood of violent behavior (Crombach and Elbert, 2015). Moreover, high levels of appetitive aggression impede the successful reintegration of former combatants (Maedl et al., 2010).

Beyond the impact of PTSD and appetitive aggression in explaining ongoing violence in post-conflict regions, research has also focused on the effect of childhood maltreatment. According to the cycle of violence hypothesis (Widom, 1989), adverse childhood experiences culminate in aggressive behavior toward one’s own children – thus producing an ongoing climate of violence in families. This trans-generational effect of childhood maltreatment was also observed in Sub-Saharan African post-conflict regions. Rwandan parents with histories of childhood abuse had an elevated risk of perpetrating violence against their own children (Rieder and Elbert, 2013; Roth et al., 2014). However, the impact of childhood maltreatment and trauma-related disorders on abusive child-rearing practices is not yet fully understood (Pears and Capaldi, 2001; Catani, 2010).

The majority of studies focusing on the relationship between combat exposure and ongoing violence in post-conflict regions almost exclusively focused on male combatants or soldiers (McKay and Mazurana, 2004; Coulter et al., 2008; Herrmann and Palmieri, 2010). However, studies indicate that females in conflict regions are also active agents of warfare and make up a proportion to 30% of members of armed groups (Brett, 2002; Mazurana, 2004). Girl soldiers were part of fighting forces in 55 countries, 38 of these were involved in internal wars between 1990 and 2003 (McKay and Mazurana, 2004). Females cover a variety of tasks, ranging from supportive, caretaking roles (e.g., cooking or washing) to performing as armed combatants (Mazurana and Carlson, 2004; Coulter et al., 2008; Annan et al., 2009). Some also hold central commanding roles, having achieved high-ranking military positions and authority (Mazurana, 2004; Coulter et al., 2008). For many, membership in an armed group is accompanied by an expansion of traditional gender roles and thereby new possibilities (Coulter et al., 2008).

Though the number of quantitative studies about women or girls at war has been increasing, little is known about the challenges with which female, former members of armed groups contend post-war. Only a minority have been formally included in disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration processes (Schauer and Elbert, 2010). In a review of US soldiers, female active-duty service members were found to be at the same risk for developing PTSD as their male counterparts (Chaumba and Bride, 2010). In a survey about youth in Uganda, girls abducted by Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) reported 20% higher rates of psychological distress compared to female non-abductees, even years after their return home (Annan et al., 2011).

In probably all cultures, females are assumed to be less aggressive than males (Richardson, 2005; Stockley and Campbell, 2013). However, sex differences vary depending on the social context and different forms of aggression (Archer, 2004; Campbell, 2006). From an evolutionary point of view, it has been argued that males have been more involved in competition regarding social status, wealth, and sexual partners, and that for them aggressive behavior might be a promising strategy (Wilson et al., 2002). Campbell (2013) argues, due to their evolutionary higher involvement in raising children females prefer strategies with lower risk to get injured such as indirect forms of aggression in order to not jeopardize reproductive success. In contrast, Richardson and Hammock (2007) emphasize the impact of gender role expectations, as the traditional role model of femininity is inconsistent with aggressive acts. Concerning appetitive aggression in females, studies are limited and inconsistent. In a sample of Rwandan genocide perpetrators, females reported lower levels than males (Weierstall et al., 2011). In contrast, no gender effect in the prediction of appetitive aggression was revealed in a sample of Columbian ex-combatants (Weierstall et al., 2013a). Meyer-Parlapanis et al. (submitted) found that females when having experienced similar combat-related events can develop levels comparable to males. Aiming to further strengthen the knowledge about the challenges female ex-combatants face post-war, particularly in Sub-Saharan African post-conflict regions, the present study was conducted.

Burundi was selected for data collection owing to its continued struggle in the aftermath of a long-lasting civil war. It is a small but densely populated state in the African Great Lakes Region that has suffered a long history of ethnic violent conflicts. In 1993 the conflict escalated into a civil war between the Tutsi-dominated army and armed Hutu rebel groups (United States Institute of Peace, 2002). Throughout this conflict over 300,000 people, mostly civilians, were killed. The war ended in 2006 (Uvin, 2009), and the last demobilizations of rebel members officially took place in 2009 (World Bank, 2009). Today, the country continues to grapple with high levels of violence. The recent violent outbursts in response to political elections exemplify the sustained fragility of peace in Burundi (United Nations, 2015).

With the present study it was aimed to assess how females in settings like Burundi cope with adverse experiences made throughout their lives. Female, former members of armed groups were compared to civilians who had never been active agents in the civil war. Former rebels were further allocated to two groups: combatants having participated in active fighting or supporters having been only involved in supportive, non-military tasks.

We investigated differences in exposure to childhood violence and traumatic events, as well as the perpetration of violent acts and their consequences for mental health in terms of PTSD and appetitive aggression. Moreover, we assessed predictors of low-threshold daily aggressive behavior to gain insight into the cycle of violence. The highest levels of exposure to both traumatic and perpetrated events were expected within former members of armed groups as well as high levels of appetitive aggression in former combatants due to their combat experience. A similar pattern was assumed to hold true for PTSD symptoms because of the building block effect. Finally, threshold changes in aggressive behavior were expected between the groups. It was hypothesized that high levels of appetitive aggression and PTSD contribute to perpetrating more recent aggressive acts. Furthermore, the impact of experienced childhood maltreatment on the assumed relationships between PTSD, appetitive aggression and violent behavior was of interest.

Semi-structured diagnostic interviews were conducted with 158 women in Burundi who had either been former combatants (n = 54), supporters of armed groups without involvement in fighting (n = 50), or civilians (serving as control group, n = 54). One former combatant was excluded prior to data analysis due to discrepancies in the information provided. Demographics of the three groups are shown in Table 1.

Respective statistical tests indicated no significant differences between the groups in age, number of children, education, and working situation (all p ≥ 0.07). Former combatants and supporters did not differ regarding military variables (all p ≥ 0.37).

Data collection was carried out in fall 2014 in Bujumbura, Burundi. Former armed group members were invited to the study with the help of a local contact person from an official national veteran association. Female civilians inhabiting the same neighborhoods as the former members of armed groups were invited to participate as controls. A mixed team of experienced clinical psychologists from the University of Konstanz and trained local psychology students conducted the interviews. The latter either worked as translators (English/French – Kirundi) or performed interviews on their own following intensive training. They had gathered extensive experience in previous projects and were closely supervised to guarantee high interviewer reliability. Each interview lasted about 2–3 h and took place in either the rooms of the Centre for Mental Health (Centre Akabanga) or at a military training compound (Camp Muha) in Bujumbura, both provided by the Burundian army. Interviewers ensured that the interviews were conducted privately. Participants received 10,000 BIF (approximately 5€) for compensation and a refund of transport costs. In addition, respondents were offered to participate in another study (not reported here). The Ethical Review Boards of both the University of Konstanz and the University Lumière of Bujumbura approved the study. All participants provided informed consent.

All instruments were translated and blindly back translated from a validated English or French version into Kirundi. Differences in meaning were discussed with both translators and a team of local psychologists until a consensus was reached.

Participants were asked for age, level of education, working situation, and number of children. When applicable, details about participation in the rebel movement were asked (year of and age at entry, forced or voluntary joining, duration spent in the armed group).

A 20-item event list that has been applied in different contexts with populations affected by violent conflicts (Neuner et al., 2004; Nandi et al., 2015) was used to assess lifetime traumatic load. Events from the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa et al., 1997) were incorporated as well as different war-related witnessed and self-experienced events (e.g., being attacked). It was asked whether or not certain events had been experienced. Thus, items were coded dichotomously with 0 (no) or 1 (yes). Event types were summed up to measure the total traumatic load.

To assess lifetime self-committed violence, 15 different types of perpetrated violence (e.g., committed assaults, mutilation) were assessed. The checklist has been applied in different combatant samples (Weierstall and Elbert, 2011). Coding of items was the same as for traumatic event types.

Exposure to violence during childhood was assessed with a 30-item culturally adapted version of the Domestic and Community Violence Checklist (DCVC, for details see Hermenau et al., 2011; Crombach and Elbert, 2014). It incorporates different experiences of maltreatment from various dimensions (psychological, physical, sexual violence, neglect) ranging from small (e.g., being pinched) to very severe events (e.g., sexual abuse). Again, all items were coded dichotomously and summed up. The sum score represents the number of experiences, ranging from 0 to 30.

In order to measure the level of perpetration of violence, questions from the DCVC were also asked from a perpetrator’s perspective (e.g., have you pinched someone) during the period of the last 3 months. Three items were added to assess reactive components of current aggression (e.g., Have you fought back, because you were attacked), whereas one item was removed (having witnessed sexual abuse), as this was not transformable into a perpetrator’s perspective. Items were coded in the same manner and summed up as above, reaching a sum score from 0 to 32.

To assess the extent of propensity toward appetitive aggression the Appetitive Aggression Scale (AAS) was used (Weierstall and Elbert, 2011). It contains 15 items about the positive and exhilarating perception of violence related to a combatant setting (e.g., “Is it exciting for you if you make an opponent really suffer?”) and were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (I totally disagree) to 4 (I totally agree). Items were summed up to create a sum score between 0 and 60. Internal consistency was very high in the current study (Cronbach’s α = 0.95)

The PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview (PSS-I, Foa et al., 1993; Foa and Tolin, 2000) was used to assess the frequency of PTSD symptoms. It is comprised of 17 items, each referring to one of the symptoms for PTSD according to DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). Answers are scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (five or more times per week/almost always). Items are summed up to a sum score ranging between 0 and 51. The PSS-I has proven validity in comparable samples (Ertl et al., 2010) and good psychometric properties (Foa and Tolin, 2000). Internal consistency in the current study was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

SPSS 21.0 was used for statistical analysis. A MANOVA, followed by alpha-adjusted univariate F-tests, was calculated to assess group differences regarding childhood violence, traumatic events, perpetrated event types, PTSD symptom severity, and appetitive aggression. Post hoc tests were conducted using Games-Howell. To assess predictors of current aggressive behavior hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses were conducted. Group membership was dummy-coded with combatants as reference group.

No univariate or multivariate outliers were found. Skewness and curtosis of variables as well as homogeneity of variances among groups gave no rise for concern. Pillai’s criterion was used in the MANOVA due to its robustness against violations of homogeneity of covariance. The residuals of the regression analysis were normally distributed and independent, assumptions of homoscedasticity and linearity met. Multicollinearity was of no concern. All analyses were two-tailed and based on α = 0.05 level of significance.

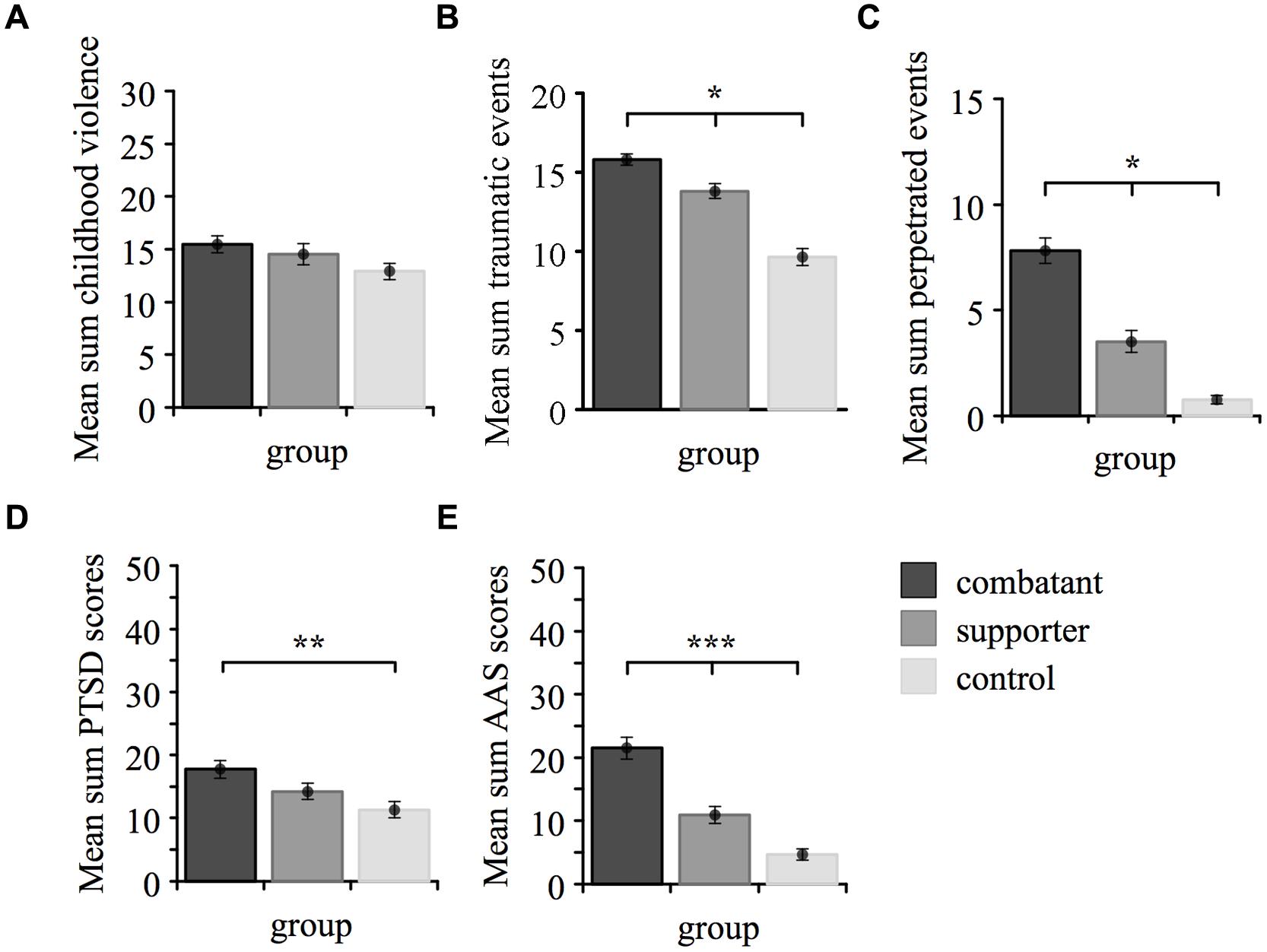

Using Pillai’s trace, MANOVA showed a significant multivariate effect of group membership, V = 0.54, F(8,298) = 13.86, p < 0.001. Univariate F-tests revealed significant group differences with large effect sizes in traumatic event types, F(2,152) = 46.92, p < 0.001, = 0.38, perpetrated event types, F(2,152) = 59.01, p < 0.001, = 0.44 and appetitive aggression, F(2,152) = 41.17, p < 0.001, = 0.35. Former combatants had significantly higher rates compared to both former supporters and controls. A group difference with moderate effect size was found for PTSD symptom severity, F(2,152) = 5.96, p < 0.01, = 0.07. Combatants suffered more severely from PTSD symptoms than controls, but did not differ from supporters. Groups did not differ regarding childhood violence, F(2,152) = 2.38, p = 0.1. The results of post hoc comparisons are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Differences between the three groups regarding (A) childhood violence, (B) traumatic event types, (C) perpetrated event types, (D) posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom severity and (E) appetitive aggression. Mean sum scores are plotted on the ordinate, whereas each bar refers to a group. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

As illustrated in Table 2, trauma-related variables (traumatic event types, childhood violence, PTSD symptom severity) were moderately associated. Appetitive aggression and perpetrated event types showed a strong association. Overall, trauma- and aggression-related variables correlated with moderate to high size.

To assess predictors for current aggressive behavior, in a first step the two dummy-coded variables of group membership variables were entered [F(2,152) = 3.77, p = 0.025, R2adjusted = 0.04]. Belonging to the group of controls (p < 0.01) or supporters (p = 0.09) was associated with lower levels of current aggressive behavior compared to combatants. After adding appetitive aggression and PTSD symptom severity as predictors in the second step, there was a significant model improvement [F(2,150) = 18.01, p < 0.001, R2adjusted = 0.21]. As illustrated in Table 3, both, PTSD symptom severity and appetitive aggression were positively related to current aggressive behavior. Group membership proved insignificant After including childhood violence, the model substantially improved in terms of variance explained [F(1,149) = 40.03, p < 0.001, R2adjusted = 0.37]. Higher levels of both appetitive aggression and childhood violence were significantly related to current aggressive behavior. However, PTSD symptom severity now failed to reach significance. Adding interaction terms did not improve the model in terms of higher variance explained, nor did they reach significance.

In the present study former combatants reported higher exposure to traumatic events and greater involvement in lifetime perpetration of aggressive acts compared to both former supporters and civilians. In accordance with the building block effect, symptoms of PTSD were also highest among former combatants. Being an active agent of warfare resulted in greater damage of trauma-related mental health in comparison to those who had witnessed war-related actions or were victims of the civil war. These results coincide with previously published studies on former male combatants presenting high impairment due to PTSD (e.g., Weierstall et al., 2013a; Nandi et al., 2015) and on psychological problems in former girl soldiers (Annan et al., 2011).

Severe physical punishment as well as high rates of sexual abuse are typical experiences for girls when growing up in armed groups (McKay and Mazurana, 2004). As more than 50% joined the armed groups when they were younger than 18, they were at particular risk for exposure to high levels of violence during childhood. However, the individuals in the three groups did not differ regarding their exposure to adverse experiences during childhood. A possible explanation could be that domestic violence and corporal punishment are a widespread phenomenon within the Burundian society. Thus, all females are likely to have experienced severe forms of childhood maltreatment. Moreover, due to the civil war and irrespectively of their own involvement many girls grew up in disrupted families and adverse conditions.

Regarding appetitive aggression, the highest levels were present among former female combatants even several years after the end of the civil war. Compared to civilians, elevated levels of appetitive aggression were also found in supporters. A recent study on Burundian former male combatants and active soldiers identified both exposure to traumatic events and lifetime involvement in violent offenses as principal risk factors for appetitive aggression (Nandi et al., 2015). These factors might also account for differences in appetitive aggression between former female supporters and civilians, as the former reported greater exposure to traumatic events and perpetration of violent acts. Moreover, as self-committed violence is known to be strongly correlated with appetitive aggression (e.g., Hecker et al., 2012; Weierstall et al., 2013b) previously found differences between males and females (Weierstall et al., 2011) are likely to originate from a substantial gender difference in exposure to warfare. In all war scenarios, male combatants are exposed to combat more frequently and for a longer period of time, resulting in a higher probability to be shaped by these environments. In favor of this interpretation are the results of Meyer-Parlapanis et al. (submitted) with matched samples and thus comparable levels of both exposure to traumatic events and perpetration of violence. However, it may well be possible that men are more easily attracted to participate in armed conflicts whereas this may be true only for a selection of women. Our results demonstrate, that those women who are exposed to fighting and combat, develop levels of appetitive aggression similar to their male counterparts (Weierstall et al., 2013a; Meyer-Parlapanis et al., submitted) which can be considered as stable and long-term adaptation to adverse and insecure environments (Crombach and Elbert, 2014).

Furthermore, evidence was provided that appetitive aggression, PTSD symptoms and violence experienced during childhood are important factors explaining the perpetration of everyday violence. Consistent to previous research, appetitive aggression appears to be crucial in thriving, ongoing violent behavior in post-conflict regions (Crombach and Elbert, 2014), highlighting the importance to focus on in demobilization processes of former combatants. In contrast to appetitive aggression, PTSD and violence experienced during childhood seem to influence aggressive behavior via the same mechanism, indicated by the fact that the former lost its predictive value as soon as the latter was included in the regression model. Research has found PTSD symptoms of hyperarousal to be associated with deficits in self-regulatory competences (Galovski and Lyons, 2004; Orth and Wieland, 2006; Tull et al., 2007). Also a history of childhood abuse is related to a lack of the development of behavioral control strategies (Brodsky et al., 2001; Roy, 2005). On a neurobiological level, both are linked to altered neurobiological brain circuitries (Elbert et al., 2006; Kolassa and Elbert, 2007; Braquehais et al., 2010), which partially overlap with neurobiological changes found in persons with low behavioral control strategies (Braquehais et al., 2010). These alterations in the neural circuitry due to impeded regulatory competences predispose individuals to react aggressively (Davidson, 2000; DeWall et al., 2007) and are likely to be the underlying mechanism of childhood maltreatment outperforming PTSD in predicting current aggressive behavior. Hereby, primarily anger-driven reactive forms of aggression are affected, whereas appetitive aggression presents a distinct brain pattern (Moran et al., 2014). Thus, appetitive aggression and childhood maltreatment independently contribute to different forms of aggression resulting in an overall enhanced level of aggressive acts further promoting the cycle of violence.

The current study has some limitations. Relying on self-report, memory effects and social desirability might have biased reporting appetitive aggression and aggressive acts, possibly underestimating their impact. Furthermore, the context in which violent acts occurred was not assessed. In a traditional patriarchal society such as Burundi it is likely that the females perpetrated a significant part of violence against their own children, promoting a trans-generational cycle of violence (Roth et al., 2014; Crombach and Bambonyé, 2015). However, females reported both domestic and community violence, hence posing a threat to the overall development of a peaceful society. A more detailed assessment of the context might have yielded information about who is affected most by enhanced female aggressiveness.

The retrospective cohort-design limits interpretations regarding causality and direction of the reported effects. Only the chronological restrictions of the variables within the aggression model render the determined relationships between cause-and-effect plausible. Furthermore, selective dropout might have influenced the results. Severely affected women with high rates of PTSD might not have been able to participate in the interviews. Lastly, buffering effects of the community were not targeted in the current study. It is unclear, if social rejection of former fighters, who might have violated traditional gender roles, also occurred in the Burundian context. Moreover, the impact of social support, which can serve as a protective factor especially among females (Chaumba and Bride, 2010), has not been approached at all.

The present study demonstrates that in order to disrupt the cycle of violence in post-conflict regions and to help promote and sustain long lasting peace building processes, it is essential to address adverse childhood experiences, appetitive aggression and trauma-related ill-health in females formerly associated with combat. Moreover, neglecting to provide adequate resources to females in demobilization processes (Schauer and Elbert, 2010) leaves them vulnerable in the challenges related to their victimhood. Living in societies in which women are typically charged with the role of homemaking, these untreated female members of armed groups often transition directly into the roles as caregivers for their children. For those suffering from PTSD symptomology and other mental health complications, trading in guns for cooking spoons invariably places their children at risk for being the next victims in the cycle of violence. Hence prospective studies should be aimed at implementing therapeutic interventions in this particular population, comprising perspectives of both perpetrator and victim. Moreover, the evaluation of their effectiveness in terms of decreasing future aggressive acts and improving mental health is a meaningful next step. Lastly, in order to further disentangle the cycle of violence precedents and risk factors of appetitive aggression should be identified with a focus on potential differences in its development between males and females.

The research project was funded by grants to TE from the DFG and the ERC.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to sincerely thank our cooperation partner University Lumière, Bujumbura. Special thanks go to Gina-Alida Gatore, Gynelle Mugisha, Hervé Mugisha, Jean-Arnaud Muhoza, Landry-Robert Ndaboroheye, Thierry Ndayikengurukiye, Lydia Nitamga and Amini-Ahmed Rushoza for your great commitment and excellent work as interviewers and translators. We would also like to thank Jean-Baptiste Niyungeko from Burundi Red Cross and Faida Neema for helping us to contact the participants. Finally, thanks to all the Burundian women who agreed to share their stories.

American Psychiatric Association [APA] (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: Author.

Annan, J., Blattman, C., Mazurana, D., and Carlson, K. (2009). Women and Girls at War: “Wives,” Mothers, and Fighters in Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army. Available: http://www.hicn.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/wp63.pdf [Accessed May 6, 2015].

Annan, J., Blattman, C., Mazurana, D., and Carlson, K. (2011). Civil war, reintegration, and gender in Northern Uganda. J. Conflict Resolut. 55, 877–908. doi: 10.1177/0022002711408013

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: a meta-analytic review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8, 291–322. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291.supp

Braquehais, M. D., Oquendo, M. A., Baca-Garcia, E., and Sher, L. (2010). Is impulsivity a link between childhood abuse and suicide? Compr. Psychiatry 51, 121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.05.003

Brett, R. (2002). Girl Soldiers: Challenging the Assumptions. New York, NY: Quaker United Nations Office.

Brodsky, B. S., Oquendo, M., Ellis, S. P., Haas, G. L., Malone, J. M., and Mann, J. J. (2001). The relationship of childhood abuse to impulsivity and suicidal behavior in adults with major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 158, 1871–1877. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1871

Byrne, C. A., and Riggs, D. S. (1996). The cycle of trauma: relationship aggression in male Vietnam veterans with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Violence Vict. 11, 213–225.

Campbell, A. (2006). Sex differences in direct aggression: what are the psychological mediators? Aggress. Violent Behav. 11, 237–264. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2005.09.002

Campbell, A. (2013). “High stakes and low risks: women and aggression,” in A Mind of Her Own: The Evolutionary Psychology of Women (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Catani, C. (2010). War at home – a review of the relationship between war trauma and family violence. Verhaltenstherapie 20, 19–27. doi: 10.1159/000261994

Chaumba, J., and Bride, B. E. (2010). Trauma experiences and posttraumatic stress disorder among women in the United States military. Soc. Work Ment. Health 8, 280–303. doi: 10.1080/15332980903328557

Coulter, C., Persson, M., and Utas, M. (2008). Young Female Fighters in African Wars: Conflict and its Consequences. Stockholm: Sweden Elanders Sverige AB.

Crombach, A., and Bambonyé, M. (2015). Intergenerational violence in Burundi: experienced childhood maltreatment increases the risk of abusive child rearing and intimate partner violence. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol (in press).

Crombach, A., and Elbert, T. (2014). The benefits of aggressive traits: a study with current and former street children in Burundi. Child Abuse Negl. 38, 1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.12.003

Crombach, A., and Elbert, T. (2015). Controlling offensive behavior using narrative exposure therapy: a randomized controlled trial of former street children. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 3, 270–282. doi: 10.1177/2167702614534239

Davidson, R. J. (2000). Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation–a possible prelude to violence. Science 289, 591–594. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591

DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., Stillman, T. F., and Gailliot, M. T. (2007). Violence restrained: effects of self-regulation and its depletion on aggression. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 43, 62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.12.005

Elbert, T., Rockstroh, B., Kolassa, I.-T., Schauer, M., and Neuner, F. (2006). “The influence of organized violence and terror on brain and mind: a co-constructive perspective,” in Lifespan Development and the Brain: The Perspective of Biocultural Co-Constructivism, eds P. Baltes, P. Reuter-Lorenz, and F. Roesler (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 326–363.

Elbert, T., Weierstall, R., and Schauer, M. (2010). Fascination violence: on mind and brain of man hunters. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 260(Suppl. 2), S100–S105. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0144-8

Ertl, V., Pfeiffer, A., Saile, R., Schauer, E., Elbert, T., and Neuner, F. (2010). Validation of a mental health assessment in an African conflict population. Psychol. Assess. 22, 318–324. doi: 10.1037/a0018810

Foa, E. B., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L., and Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychol. Assess. 9, 445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.09.005

Foa, E. B., Riggs, D. S., Dancu, C. V., and Rothbaum, B. O. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma. Stress 6, 459–473. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490060405

Foa, E. B., and Tolin, D. F. (2000). Comparison of the PTSD symptom scale-interview version and the clinician administered PTSD scale. J. Trauma. Stress 13, 181–191. doi: 10.1023/A:1007781909213

Galovski, T., and Lyons, J. A. (2004). Psychological sequelae of combat violence: a review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggress. Violent Behav. 9, 477–501. doi: 10.1016/s1359-1789(03)00045-4

Hecker, T., Hermenau, K., Maedl, A., Elbert, T., and Schauer, M. (2012). Appetitive aggression in former combatants – derived from the ingoing conflict in DR Congo. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 35, 244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.02.016

Hermenau, K., Hecker, T., Ruf, M., Schauer, E., Elbert, T., and Schauer, M. (2011). Childhood adversity, mental ill-health and aggressive behavior in an African orphanage: changes in response to trauma-focused therapy and the implementation of a new instructional system. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 5, 29. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-5-29

Herrmann, I., and Palmieri, D. (2010). Between Amazons and Sabines: a historical approach to women and war. Int. Rev. Red Cross 92, 19–30. doi: 10.1017/s1816383109990531

Karunakara, U. K., Neuner, F., Schauer, M., Singh, K., Hill, K., Elbert, T., et al. (2004). Traumatic events and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder amongst Sudanese nationals, refugees and Ugandans in the West Nile. Afr. Health Sci. 4, 83–93.

Kolassa, I.-T., and Elbert, T. (2007). Structural and functional neuroplasticity in relation to traumatic stress. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 16, 321–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00529.x

MacManus, D., Dean, K., Jones, M., Rona, R. J., Greenberg, N., Hull, L., et al. (2013). Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a data linkage cohort study. Lancet 381, 907–917. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60354-2

Maedl, A., Schauer, E., Odenwald, M., and Elbert, T. (2010). “Psychological rehabilitation of ex-combatants in non-western, post-conflict settings,” in Trauma Rehabilitation after War and Conflict: Community and Individual Perspectives, ed. E. Martz (New York, NY: Springer), 177–214.

Mazurana, D. (2004). Women in Armed Opposition Groups Speak on War, Protection and Obligations under International Humanitarian and Human Rights Law. Available: http://www.icrc.org/eng/assets/files/other/women_armed_groups_2005.pdffrom [Accessed May 10, 2015].

Mazurana, D., and Carlson, K. (2004). From Combat to Community: Women and Girls of Sierra Leone. Cambridge, MA: Women’s Policy Commission, Harvard University.

McKay, S., and Mazurana, D. E. (2004). Where are the Girls? Girls in Fighting Forces in Northern Uganda, Sierre Leone and Mozambique: Their Lives During and After War, Rights & Democracy. Montréal, QC: International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

Moran, J. K., Weierstall, R., and Elbert, T. (2014). Differences in brain circuitry for appetitive and reactive aggression as revealed by realistic auditory scripts. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8:425. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00425

Morland, L. A., Love, A. R., Mackintosh, M.-A., Greene, C. J., and Rosen, C. S. (2012). Treating anger and aggression in military populations: research updates and clinical implications. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 19, 305–322. doi: 10.1111/cpsp12007

Nandi, C., Crombach, A., Bambonye, M., Elbert, T., and Weierstall, R. (2015). Predictors of posttraumatic stress and appetitive aggression in active soldiers and former combatants. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 6, 26553. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.26553

Neuner, F., Schauer, M., Karunakara, U., Klaschik, C., Robert, C., and Elbert, T. (2004). Psychological trauma and evidence for enhanced vulnerability for posttraumatic stress disorder through previous trauma among West Nile refugees. BMC Psychiatry 4:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-34

Orth, U., and Wieland, E. (2006). Anger, hostility, and posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults: a meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 74, 698–706. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.698

Pears, K. C., and Capaldi, D. M. (2001). Intergenerational transmission of abuse: a two– generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse Negl. 25, 1439–1461. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00286-1

Richardson, D. S. (2005). The myth of female passivity: thirty years of revelations about female aggression. Psychol. Women Q. 29, 238–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00218.x

Richardson, D. S., and Hammock, G. S. (2007). Social context of human aggression: are we paying too much attention to gender? Aggress. Violent Behav. 12, 417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2006.11.001

Rieder, H., and Elbert, T. (2013). The relationship between organized violence, family violence and mental health: findings from a community-based survey in Muhanga, Southern Rwanda. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 4:21329. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.21329

Roth, M., Neuner, F., and Elbert, T. (2014). Transgenerational consequences of PTSD: risk factors for the mental health of children whose mothers have been exposed to the Rwandan genocide. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 8, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-8-12

Roy, A. (2005). Childhood trauma and impulsivity. Possible relevance to suicidal behavior. Arch. Suicide Res. 9, 147–151. doi: 10.1080/13811110590903990

Saile, R., Ertl, V., Neuner, F., and Catani, C. (2014). Does war contribute to family violence against children? Findings from a two-generational multi-informant study in Northern Uganda. Child Abuse Negl. 38, 135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.10.007

Schauer, E., and Elbert, T. (2010). “The psychological impact of child soldiering,” in Trauma Rehabilitation after War and Conflict: Community and Individual Perspectives, ed. E. Martz (New York, NY: Springer), 311–360.

Steel, Z., Silove, D., Phan, T., and Bauman, A. (2002). Long-term effect of psychological trauma on the mental health of Vietnamese refugees resettled in Australia: a population-based study. Lancet 360, 1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11142-1

Stockley, P., and Campbell, A. (2013). Female competition and aggression: interdisciplinary perspectives. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20130073. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0073

Tull, M. T., Barrett, H. M., Mcmillan, E. S., and Roemer, L. (2007). A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behav. Ther. 38, 303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.001

United Nations (2015). Concerned Over Potential Violence in Burundi, UN Chief Urges Resumption of Dialogue [Online]. Available: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=51056-.VYQGwFXtlHw [Accessed June 19, 2015].

United States Institute of Peace (2002). International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi: Final Report [Online]. Available: http://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/file/resources/collections/commissions/Burundi-Report.pdf [Accessed 25 June, 2015].

Weierstall, R., Bueno Castellanos, C. P., Neuner, F., and Elbert, T. (2013a). Relations among appetitive aggression, post-traumatic stress and motives for demobilization: a study in former Colombian combatants. Confl. Health 7, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-7-9

Weierstall, R., Haer, R., Banholzer, L., and Elbert, T. (2013b). Becoming cruel: appetitive aggression released by detrimental socialisation in former Congolese soldiers. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 37, 505–513. doi: 10.1177/0165025413499126

Weierstall, R., and Elbert, T. (2011). The appetitive aggression scale-development of an instrument for the assessment of human’s attraction to violence. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2:8430. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.8430

Weierstall, R., Schaal, S., Schalinski, I., Dusingizemungu, J. P., and Elbert, T. (2011). The thrill of being violent as an antidote to posttraumatic stress disorder in Rwandese genocide perpetrators. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2:6345. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.6345

Wilson, M., Daly, M., and Pound, N. (2002). “An evolutionary psychological perspective on the modulation of competitive confrontation and risk-taking,” in Hormones, Brain and Behavior, eds D. W. Pfaff, A. P. Arnold, A. M. Ertgen, S. E. Fahrbach, and R. T. Rubin (Amsterdam: Academic Press), 381–408.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), trauma, childhood maltreatment, violence, aggression, female combatant, Burundi, post-conflict country

Citation: Augsburger M, Meyer-Parlapanis D, Bambonye M, Elbert T and Crombach A (2015) Appetitive Aggression and Adverse Childhood Experiences Shape Violent Behavior in Females Formerly Associated with Combat. Front. Psychol. 6:1756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01756

Received: 31 August 2015; Accepted: 02 November 2015;

Published: 17 November 2015.

Edited by:

J. P. Ginsberg, Dorn VA Medical Center, USACopyright © 2015 Augsburger, Meyer-Parlapanis, Bambonye, Elbert and Crombach. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mareike Augsburger, bWFyZWlrZS5hdWdzYnVyZ2VyQHVuaS1rb25zdGFuei5kZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.