95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 04 February 2014

Sec. Emotion Science

Volume 5 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00030

This article is part of the Research Topic Emotion and Aging: Recent Evidence from Brain and Behavior View all 15 articles

Facial expressions convey important information on emotional states of our interaction partners. However, in interactions between younger and older adults, there is evidence for a reduced ability to accurately decode emotional facial expressions. Previous studies have often followed up this phenomenon by examining the effect of the observers' age. However, decoding emotional faces is also likely to be influenced by stimulus features, and age-related changes in the face such as wrinkles and folds may render facial expressions of older adults harder to decode. In this paper, we review theoretical frameworks and empirical findings on age effects on decoding emotional expressions, with an emphasis on age-of-face effects. We conclude that the age of the face plays an important role for facial expression decoding. Lower expressivity, age-related changes in the face, less elaborated emotion schemas for older faces, negative attitudes toward older adults, and different visual scan patterns and neural processing of older than younger faces may lower decoding accuracy for older faces. Furthermore, age-related stereotypes and age-related changes in the face may bias the attribution of specific emotions such as sadness to older faces.

Facial expressions convey important information on emotional states of our interaction partners (Ekman et al., 1982). Thus, the correct interpretation of facial expressions may facilitate emotional understanding and enhance the quality of interpersonal communication.

Recent evidence suggests that the correct interpretation of emotional expressions may be negatively affected in older age due to processes related to both the sender and the observer. The majority of the extant research has focused on the influence of the observers' age and concludes that older observers have deficits in the decoding of specific emotions (see Ruffman et al., 2008; Isaacowitz and Stanley, 2011, for reviews).

The age of those showing the facial expressions was initially less often considered. As a possible reason, the influential model of face processing by Bruce and Young (1986) postulated that the decoding of facial expressions is robust to the idiosyncratic features of a given face, which might be influenced by age, sex or other factors. However, this proposition has been subject to controversial debate (e.g., Schweinberger and Soukup, 1998; Schyns and Oliva, 1999; Kaufmann and Schweinberger, 2004; Calder and Young, 2005; Aviezer et al., 2011; Barret et al., 2011). Instead, it is likely that wrinkles, folds and the sag of facial musculature in the older face affect the interpretation of facial expressions. This assumption has been confirmed by recent results of decoding accuracy varying with the age of the face (Malatesta et al., 1987b; Borod et al., 2004; Ebner and Johnson, 2009, 2010; Murphy et al., 2010; Richter et al., 2011; Riediger et al., 2011; Hess et al., 2012; Ebner et al., 2012, 2013; Hühnel et al., 2014). Previous reviews have mainly focused on the age of the observer (Ruffman et al., 2008; Isaacowitz and Stanley, 2011) or on age-of-face effects on face identity recognition (e.g., Rhodes and Anastasi, 2012). Adding to this work, the present review is the first to focus on the influence of facial age on expression decoding and its possible underlying mechanisms, taking into account most recent work on this subject published after these previous reviews. Our aim was to compile and evaluate findings, thereby focusing on the question to which extent methodological differences between studies may account for inconsistent results. Further, we wish to identify unresolved research questions and suggest topics for future research. We will first give a very brief overview of the influence of the observers' age on decoding accuracy and the mechanisms underlying these effects. However, as this research has already been reviewed elsewhere (Ruffman et al., 2008; Isaacowitz and Stanley, 2011), we will mainly focus on the influence of the faces' age.

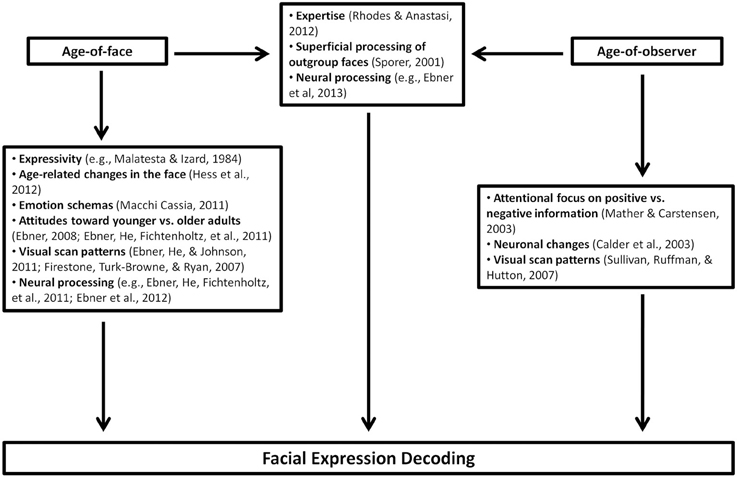

An age-related decline in decoding facial expressions has been repeatedly reported (e.g., Calder et al., 2003; Ruffman et al., 2008; Isaacowitz and Stanley, 2011). However, recent evidence suggests that this decline is confined to specific emotions. An overview of mechanisms underlying emotion-specific effects of the observers' age on facial expression decoding is given in Figure 1 (right part). Some studies found an age-related deficit in decoding negative, but not positive emotional expressions (Phillips et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2006; Keightley et al., 2007; Ebner and Johnson, 2009). In addition, older observers had a greater bias toward thinking that individuals were feeling happy when they were displaying either enjoyment or non-enjoyment smiles (Slessor et al., 2010; but see Riediger et al., under review). These results have been accounted for by an information processing bias by older observers, leading to increased attention toward positive compared to negative information (Mather and Carstensen, 2003). This explanation is based on the socioemotional selectivity theory (SST, Carstensen and Charles, 1998), stating that older persons are, due to their limited future time perspective, inclined to engage in tasks related to emotional balance and well-being. Younger persons, in contrast, favor information seeking over emotionally rewarding goals and, thus, may be more inclined to attend to other persons' negative emotional states (Carstensen and Mikels, 2005). However, Isaacowitz and Stanley (2011) argued that the preserved ability to decode happiness may as well be due to the relative ease of the task, when happiness is the only positive response option. Supporting this assumption, age effects for positive emotions emerged when the task was more difficult (Isaacowitz et al., 2007). Further evidence against the SST-based account is that the majority of research on emotional prosody and body language suggests that older observers have difficulties to decode positive as well as negative emotions (emotional prosody: Taler et al., 2006; Ruffman et al., 2009a,b; Lambrecht et al., 2012, body language: Ruffman et al., 2009a,b, but see Montepare et al., 1999, for an exception).

Figure 1. Overview of mechanisms underlying effects of the age of the face (left part) and the age of the observer (right part) as well as own-age effects (central part) on facial expression decoding.

Further conflicting the SST-based account, some studies found an age-related improvement in decoding disgust, together with no age differences for happiness and an age-related deficit in decoding sadness (Suzuki et al., 2007), or anger, fear and sadness (Calder et al., 2003). There are two alternative explanations for these findings.

The first explanation is based on observed age differences in visual scan patterns: older observers focus primarily on the lower part of the face and neglect the upper part (Wong et al., 2005; Sullivan et al., 2007). As the upper part plays a more important role for expressions of anger, fear and sadness, but not for disgust and happiness (Calder et al., 2000), this may explain why older observers are especially impaired in decoding these emotions. In line with this explanation, older observers' poor performance for decoding anger, fear and sadness correlated with fewer fixations to the top half of faces (Wong et al., 2005). However, Ebner et al. (2011c) found that visual scan patterns were independent of the observers' age, but rather varied with the expression. Thus, evidence for age differences in visual scan patterns is mixed. Furthermore, as already mentioned above, older observers' difficulties are not restricted to decoding facial expressions, but also emerge when decoding emotional prosody and bodily expression, at least rendering visual scan patterns as sole underlying mechanism unlikely.

The second explanation states that the brain regions that are responsible for decoding emotions, differ between the various emotions and that these regions are also differently affected by age-related changes (Ruffman et al., 2008; Ebner and Johnson, 2009; Ebner et al., 2012). As the frontal region, which is especially important for anger and sadness (Murphy et al., 2003), and the amygdala, which is important for fear (Murphy et al., 2003; Adolphs et al., 2005), are particularly affected by age-related changes (Jack et al., 1997; Bartzokis et al., 2003), a stronger age-related decline in decoding these emotions is predicted. In contrast, the basal ganglia, playing an important role for disgust (Phan et al., 2002), are less strongly affected by age-related changes (Raz, 2000; Williams et al., 2006), possibly resulting in a relatively preserved ability to decode disgust. Wong et al. (2005) further suggested that age-related declines in the frontal eye field, an area in the frontal lobe, may lead to deficits in visual attention, possibly leading to dysfunctional visual scan patterns. In addition, recent fMRI studies investigating brain activity in younger and older observers while viewing emotional faces suggest functional brain changes with age (Williams et al., 2006; Keightley et al., 2007). Although the pattern of results is somewhat mixed, older observers showed less amygdala activation (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003; Fischer et al., 2005, 2010), but more prefrontal cortex activation (Gunning-Dixon et al., 2003; Fischer et al., 2010) compared to younger observers when viewing emotional faces. Fischer et al. (2005) suggested that this may represent an attempt to compensate for diminished functions in other brain regions than the frontal brain. Williams et al. (2006) further argued that this may reflect a shift from automatic processing to a more controlled processing of emotional information, possibly enabling older observers to better selectively control reactions to negative stimuli and finally leading to better emotional well-being. However, it may also be important to consider the valence of the facial expressions, and to differentiate between dorsomedial (dmPFC) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). A recent study (Ebner et al., 2012) suggests that the vmPFC is more involved in affective and evaluative processing, whereas the dmPFC is involved in cognitively more complex processing. This functional dissociation seems to be largely comparable between younger and older observers. However, older observers showed increased dmPFC activity to negative faces, but decreased dmPFC to positive faces, possibly representing more controlled processing of negative compared to positive faces in older observers (Ebner et al., 2012).

Concerning the age of the face, the majority of previous research found that posed emotional facial expressions were decoded less accurately in older compared to younger faces, irrespective of the target emotion (Borod et al., 2004; Riediger et al., 2011; Ebner et al., 2012, 2013) or with the exception of happiness (Ebner and Johnson, 2009; Ebner et al., 2011c), which may be due to ceiling effects. Hess et al. (2012) confirmed this finding with artificially created face stimuli displaying identical expressions for younger and older faces. As an exception, Ebner et al. (2010) found no age difference for posed fear expressions, but for happiness, anger, sadness, disgust, and neutrality expressions. Taken together, these results suggest that decoding emotional expressions is more difficult in older compared with younger faces. However, results obtained with spontaneous, dynamic expressions yielded a more heterogeneous pattern of results. Whereas Richter et al. (2011) confirmed the generally lower decoding accuracy for older faces, and Murphy et al. (2010) found a more accurate differentiation between posed and spontaneous dynamic smiles in younger than older faces, Riediger et al. (under review) found no main effect of facial age on the differentiation between spontaneous and posed dynamic smiles, Malatesta et al. (1987b) found no significant age difference on decoding emotional facial expressions and Hühnel et al. (2014) found even higher decoding accuracy for older faces displaying sadness. In the following, we will discuss possible mechanisms underlying these results. An overview of these studies is given in Table 1 and an overview of the underlying mechanisms is given in Figure 1 (left part).

One possible explanation for reduced decoding accuracy for older faces may be that there actually is a difference in the way older and younger adults express emotions in their faces. Supporting this assumption, older adults performed worse than younger adults when following muscle-by-muscle instructions for constructing facial prototypes of emotional expressions (Levenson et al., 1991). Thus, due to age-related changes in flexibility and controllability of muscle tissue, the intentional display of facial emotions may become less successful with age and displays of unintended blended emotions may become more likely (Ebner et al., 2011c). In line with this assumption, observers more accurately judged whether videotaped speakers were telling the truth or lying when the speakers were older than when they were younger (Ruffman et al., 2012). Borod et al. (2004) further argued that an age-related decline in the frontal lobe may change emotional facial expressions, as frontal structures are especially important for the production of facial expressions and are highly vulnerable to aging.

Notably, these explanations may only account for age effects in posed expressions. For spontaneous expressions, results rather point to the assumption that younger and older adults do not differ in expressivity. In several studies, younger and older adults were filmed while reliving an emotional event or watching emotional film clips. Afterwards, their facial reactions were analyzed with objective coding systems such as FACS (Ekman et al., 1978), or MAX (Izard, 1979). An overview of these studies is given in Table 2. Although an early study suggested that older adults display more masked, that is, dissimulated, mixed and fragmented facial expressions than younger adults (Malatesta and Izard, 1984), later studies did not confirm these age differences in expressivity (Levenson et al., 1991; Tsai et al., 2000; Kunz et al., 2008), or even found higher expressivity for older faces (Malatesta-Magai et al., 1992). Thus, intentional displays of emotions may become less successful with age, but spontaneous emotional facial reactions seem to remain equally expressive throughout the life span. Besides, lower decoding accuracy for older faces cannot be fully explained by age differences in expressivity, because this effect has also been found when artificially created face stimuli controlled for expressivity were used (Hess et al., 2012).

Nevertheless, analyses of spontaneous facial expressions suggest that there may be age-related “dialects,” that is, slight differences in the way older and younger adults express certain emotions. For example, older adults expressed sadness mainly through a lowered head, whereas younger adults also showed lowered brows (Malatesta and Izard, 1984). While reliving anger and sadness eliciting episodes, younger adults showed longer durations of shame, contempt and joy expressions, which may be interpreted as a cynical, self-conscious, perhaps mocking facial presentation that is common in younger adults (Magai et al., 2006). Older adults, on the other hand, showed more knitted brows, possibly indexing a generalized distress configuration in a regulated form, serving to indicate that negative emotion is present, but protecting social partners from emotional contagion (Magai et al., 2006). Notably, these age differences were not related to a corresponding age difference in experienced emotions (Malatesta and Izard, 1984; Magai et al., 2006). However, it is unclear whether these differences are actually due to the participants' age, or whether these are cohort-specific differences. Thus, long-term studies examining several cohorts in different ages would be necessary to follow up this question.

Decoding accuracy for older faces may also be reduced due to age-related changes in the face such as wrinkles and folds (see Albert et al., 2007; Porcheron et al., 2013; for overviews of age-related changes in the face). The wrinkles and folds in the older face may resemble emotional facial expressions and lead to the impression of a permanent affective state (Hess et al., 2008). These background affects may make older adults' facial expressions more ambiguous and reduce the signal clarity (Ebner and Johnson, 2009; Hess et al., 2012). Thus, when emotional expressions were rated on multiple intensity scales for target as well as non-target emotions instead of forced-choice scales, raters attributed less of the target emotions, but more non-target emotions to older faces (Riediger et al., 2011; Hess et al., 2012). Further supporting this account, no age-of-target effects emerged for decoding emotional prosody (Dupuis and Pichora-Fuller, 2011), suggesting that lowered decoding accuracy for older targets may be specific to faces.

These age-related changes in the face may also systematically bias emotional attributions. Hess et al. (2008) suggested that facial expressions and morphological features can have similar effects on emotional attributions (“functional equivalence hypothesis”). Thus, age-related changes in the face may both reduce the signal clarity and bias emotional attributions. Physiognomic features that are frequently found in older faces, such as for example down-turned corners of the mouth may be misinterpreted as emotional expressions. Supporting this assumption, older faces received more sadness attributions than younger faces (Malatesta and Izard, 1984).

However, so far it is unclear whether these effects are due to general aging effects per se (e.g., loss of muscle tone) or due to trace emotions (Malatesta et al., 1987a). Interestingly, emotions participants attributed to older senders' neutral expressions were congruent with senders' dominant trait emotions (Malatesta et al., 1987a). Thus, frequently experienced emotions may leave a trace on the face (“habitual emotional expressions”), so that in older age, the neutral expression resembles these emotions. However, to our knowledge, this result has not yet been replicated. Clearly, more research on the relationship between emotionality and age-related changes in the face is needed. Here, long-term studies may constitute a valuable extension of previous research.

As an alternative explanation for reduced decoding accuracy for older faces, Ebner et al. (2011a) suggested that facial expression prototypes are more likely young faces. The authors argue that emotion schemas may be developed in childhood from the young faces of parents and TV and movie depictions of facial expressions, where older individuals are underrepresented (Signorielli, 2004). Thus, emotion schemas may be better calibrated to decode emotions in younger than older faces. A strong effect of the frequency of contact with faces of specific age groups has been confirmed for face identity recognition (Harrison and Hole, 2009). Furthermore, studies investigating the ability to discriminate among individual faces suggest that early in childhood, perceptual processes become tuned to adult faces as the faces children have been most frequently exposed to since birth (see Macchi Cassia, 2011, for a review). Thus, 3-year old children who had frequent contact with elderly people showed no processing advantage for younger over older adult faces, whereas non-experienced children did (Proietti et al., 2013). However, these processes may still be modulated by experience with faces of different age groups during adulthood (Macchi Cassia, 2011). As not only younger, but also older adults substantially differ in the amount of contact with older people (Wiese et al., 2012), emotion schemas for older faces may still vary in older observers.

Pertaining to decoding accuracy, this explanation still needs empirical investigation. Future studies could examine a sample with frequent contact with older adults during childhood, for example children that grew up in multi-generational homes. If this sample showed less difference in decoding accuracy between younger and older faces than a control group, this would support the hypothesis of less elaborated emotion schemas as an underlying mechanism. Furthermore, the influence of experience with older faces during early and late adulthood may be investigated by examining individuals of varying age and with varying amount of contact with older adults.

An alternative explanation may be that younger adults are preferred over older adults (Ebner and Johnson, 2009). Although there are both positive and negative elements in age stereotypes (e.g., Hummert et al., 2004; Kornadt and Rothermund, 2011), both younger and older adults showed more positive implicit attitudes (Ebner et al., 2011b) and explicit evaluations (Ebner, 2008) of younger than older faces. In addition, young adults implicitly associated themselves more closely with the concept of being young than old (Wiese et al., 2013b).

Furthermore, as individuals resort on stereotype knowledge about social groups when decoding ambiguous facial expressions of strangers (Hess and Kirouac, 2000), stereotypes may also, just like age-related changes in the face, bias the attribution of emotions. For example, if individuals hold the stereotype of older persons being less satisfied, they may be more prone to attribute sadness and less prone to attribute happiness to an older compared to a younger face. Higher decoding accuracy for emotions corresponding to stereotypes and lower decoding accuracy for emotions contradicting stereotypes may result. This may not that much apply to the posed expressions typically used in emotion decoding studies, which are rather unambiguous, but more to spontaneous expressions that we encounter in everyday life, which can be mixtures of several emotions, or be masked behind socially more desirable emotions. In line with this assumption, for spontaneous expressions, Hühnel et al. (2014) did not replicate the pattern of generally lower decoding accuracy for older faces. Instead, happiness and disgust were more accurately decoded in younger faces, whereas sadness was more accurately decoded in older faces. Also, the previously mentioned result that older faces received more sadness attributions (Malatesta and Izard, 1984) may not only be due to age-related changes in the face, but also to age-related stereotypes. In this vein, observers attributed more pain (Matheson, 1997), but less anger (Malatesta and Izard, 1984) to older faces. In addition, individuals displaying a happy facial expression were perceived as younger than individuals displaying a fearful, angry, disgusted or sad expression (Voelkle et al., 2012). In the same vein, Bzdok et al. (2012) found a negative association between the perceived age and happiness of faces. Although this pattern of results is somewhat mixed, it seems that youth is more likely associated with happiness, whereas older age is more likely associated with sadness.

However, aging stereotypes in emotional domains were not found in explicit measures, possibly because they are socially undesirable. When participants were directly asked to describe “typical” younger and older individuals, relatively neutral stereotypes in social and emotional domains were found (Boduroglu et al., 2006). Also, not all studies using spontaneous expressions found emotion-specific effects of the faces' age on decoding accuracy (Malatesta et al., 1987b; Richter et al., 2011). Furthermore, contradicting the assumed association between youth and happiness, Riediger et al. (under review) found a more frequent attribution of positive emotions to smiles shown by older compared to younger individuals. Clearly, more research is needed, using more subtle or implicit measures for age-related stereotypes, such as IAT (implicit association test), and relating them to attributed emotions.

There is some evidence that visual scan patterns may differ, depending on the age of the face that is being observed. Specifically, both younger and older observers looked longer at the eye region of older than younger neutral faces, and longer at the mouth region of younger than older neutral faces (Firestone et al., 2007). Considering the above mentioned higher importance of the eye region for expressions of anger, fear, and sadness, and the mouth region for sadness and disgust, one could expect higher decoding accuracy for younger than older faces for disgust and happiness, but not for anger, fear and sadness. However, among the studies examining age-of-face effects on decoding accuracy, only one was in line with this pattern (Hühnel et al., 2014). The majority of previous research found lower decoding accuracy for older faces, independent of the type of expression. Furthermore, other studies found that visual scan patterns were independent of the faces' age (He et al., 2011) or depended on the type of expression (Ebner et al., 2011c). Thus, Ebner et al. (2011c) only confirmed the result of longer looking at the eye region of older than younger faces for expressions of anger. For disgust, the opposite pattern with longer looking at the lower half of older than younger faces was found. There were no age differences for happy, fearful, sad or neutral faces. Thus, the result of different visual scan patterns for younger than older faces may not be generalizable across all facial expressions. In addition, whereas young observers' expression identification of young faces was better the longer they looked at the upper half of faces, older observers' expression identification of young faces was better the longer they looked at the lower half of faces (Ebner et al., 2011c). Thus, the assumption of one visual scan pattern leading to higher accuracy for both younger and older observers and younger and older faces might not always be appropriate.

Considering these mixed results, more research on this topic, relating visual scan patterns for faces with varying age and facial expressions to decoding accuracy is needed to decide whether visual scan patterns may account for age-of-face effects on decoding accuracy. So far, evidence rather contradicts the assumption of visual scan patterns as an underlying mechanism.

To our knowledge, previous EEG studies only examined the neural processing of neutral, but not emotional younger and older faces (e.g., Wiese et al., 2008, 2012; Ebner et al., 2011b; Wolff et al., 2012). These studies revealed that the age of the face influenced both early and late ERP components (Ebner et al., 2011b), suggesting that age already influences early processing stages. For older faces, enlarged amplitudes of the N170, a negative deflection over occipito-temporal sites, have been found (Wiese et al., 2008, 2012), suggesting that structural encoding may be more difficult for older faces. Further, enlarged Late Positive Potentials (LPP, a positive deflection over parietal sites) for older faces suggest more controlled processing of older than younger faces (Ebner et al., 2011b). This latter assumption is further supported by recent fMRI results of greater dmPFC activation for older than younger emotional faces (Ebner et al., 2012). However, so far only very little research on neural processing of younger and older emotional faces has been conducted, allowing no definite conclusion on neural processing as an underlying mechanism. Thus, further research examining the relation of neural processing of emotional younger and older faces to decoding accuracy is needed.

Apart from the above mentioned main effects of the ages of the observer and the face, age congruence between the observer and the face might influence decoding accuracy as well. As emotions are less accurately decoded in out-group than in-group faces (Thibault et al., 2006) and age is an important social category, one could expect an own-age advantage in face processing.

In line with this assumption, participants tended to look longer at own-age faces and longer looking at own-age faces predicted better own-age expression identification (Ebner et al., 2011c); they were more distracted by own-age faces (Ebner and Johnson, 2010) and fMRI-Studies report different activities for own-age than other-age faces (Wright et al., 2008; Ebner et al., 2011a, 2013), possibly indexing a preference for and more interest in own-age faces. Some EEG-studies report partly comparable own-age and own-race effects on ERPs for neutral faces (Wiese et al., 2008; Ebner et al., 2011b; but see Wiese, 2012; Wiese et al., 2013a, for partly different ERP correlates). Furthermore, several studies found that participants remembered own-age faces better than other-age faces (see Rhodes and Anastasi, 2012, for a meta-analysis). There are two main explanations for this latter finding. Firstly, social cognitive theories suggest that faces of out-group members are cognitively disregarded and more superficially processed than faces of in-group members (Sporer, 2001). Secondly, more experience or contact with members of the own age group may lead to higher perceptual expertise with own-age faces (Rhodes and Anastasi, 2012) and to higher familiarity with the expressive style of the own age group (Malatesta et al., 1987b). So far, evidence is more in line with the latter explanation, as the amount of contact appears to be related to face identity recognition (Harrison and Hole, 2009; Wiese et al., 2012, 2013b; Wolff et al., 2012) and facial expression decoding accuracy (Ebner and Johnson, 2009) of other-age faces. Hugenberg and colleagues (Hugenberg et al., 2010, 2013) suggested an integration of both theories in the Categorization- Individuation Model, which may also be useful to explain the own-age advantage. According to this model, own-group biases may be due to the combined influence of social categorization, the motivation to individuate and perceptual experience (Hugenberg et al., 2010). An overview of possible mechanisms underlying own-age effects on decoding accuracy is given in Figure 1 (central part).

It is likely to assume that these in-group effects in face processing also influence facial expression decoding. Usually, facial expressions of in-group members are more accurately decoded than expressions of out-group members, even if group membership is manipulated (Thibault et al., 2006; Young and Hugenberg, 2010). In addition, automatic affective responses to other persons' emotional expressions are congruent for ingroup members, but incongruent for outgroup members (Weisbuch and Ambady, 2008). In an early study, Malatesta et al. (1987b) confirmed an own-age advantage in facial expression decoding accuracy. In addition, Riediger et al. (under review) reported an own-age effect on the ability to differentiate between spontaneous and posed smiles. Surprisingly though, the majority of the extant research found no own-age advantage (Borod et al., 2004; Ebner and Johnson, 2009; Murphy et al., 2010; Ebner et al., 2011c, 2012, 2013; Hühnel et al., 2014) or an own-age advantage that was confined to specific emotions (Riediger et al., 2011). Thus, age congruence between the observer and sender of facial expressions seems to play a minor role for facial expression decoding, and the features that are important for identity recognition of faces may not be identical to those that are important for decoding facial expressions (Ebner and Johnson, 2009).

To sum up, the age of the face seems to play an important role for the interpretation of facial expressions. Posed expressions are less accurately decoded in older compared with younger faces. However, for spontaneous expressions, results are rather mixed. As a possible explanation, older adults are less expressive when posing emotional expressions, but equally expressive when spontaneously showing emotions. Yet at the same time, age stereotypes and age-related changes in physiognomic features of the face may bias the attribution of certain emotions. Contrariwise, age congruence between observer and sender of facial expressions may only play a minor role for expression decoding.

Concerning the underlying mechanisms, more research is needed to decide which of the suggested mechanisms are likely to underlie age-of-face effects on decoding accuracy. Age differences in expressivity are unlikely to be the sole underlying mechanism, as age-of-face effects have also been found when expressivity was controlled for (Hess et al., 2012). Further, previous research rather argues against visual scan patterns as an underlying mechanism. For the remaining mechanisms, i.e., age-related changes in the face, emotion schemas, attitudes toward older adults, and neural processing, more research is needed to judge the applicability of these accounts. It is unlikely to assume only one single mechanism driving age-of-face effects. Rather, multiple mechanisms seem to affect decoding accuracy.

One of the aims of the present review was to outline promising areas of future research. Although several mechanisms have been proposed to underlie age-of-face effects on decoding accuracy, only very little research directly tested the influence of these mechanisms. Thus, in our view, the most important objective for future research in this area will be to directly examine the influence of each of these variables on decoding accuracy for younger and older faces. An overview of some interesting questions for future research is given in Box 1. For example, further EEG and fMRI studies would be suited to relate neural processing of younger and older emotional faces to decoding accuracy. In addition, long-term studies on age-related changes in the face and their relation to frequently experienced emotions, and on changes in emotion schemas, which may be related to contact frequency with different age groups, may shed further light on gradual evolvement of these mechanisms. Further research is also needed on the relationship between age-related stereotypes and decoding biases. Furthermore, so far the question whether age-of-target effects are specific for facial expressions, or whether they also emerge in other emotion channels, is not yet fully resolved, as there is only one previous study analyzing age-of-target effects on decoding emotional prosody (Dupuis and Pichora-Fuller, 2011). Finally, future studies may examine whether the lower decoding accuracy for older faces affects the quality of interpersonal interactions and relationships. Thus, we think that exploring age-of-face effects on facial expression decoding and the underlying mechanisms is a promising and interesting area for future research.

Box 1. Questions for future research.

Are age-related dialects for facial expressions due to aging effects per se (such as changes in flexibility and controllability of muscle tissue), or due to cohort-specific differences (such as differences in display rules)?

Does the frequency of contact to older adults during childhood and adulthood modulate age-of-face effects on decoding accuracy?

Are age-related changes in facial physiognomic features that resemble certain emotions due to aging effects per se (such as loss of muscle tone) or due to frequently experienced emotions, leaving a trace on the face?

Are age-related response biases in emotion decoding tasks related to implicit and explicit stereotypes of aging?

Is the lower decoding accuracy for older faces related to more negative attitudes toward older than younger adults?

Do visual scan patterns differ for younger and older emotional faces? If yes, might this effect explain age-of-face effects on decoding accuracy?

Are age-of-face effects on expression decoding related to differences in neural processing of younger and older emotional faces?

What is the time course of neural processing of age and emotional expression of a face?

Does the age of the target affect emotion decoding in other emotion channels than facial expressions, such as emotional prosody or body language?

Does the lower decoding accuracy for older faces affect the quality of interpersonal interactions and relationships for older adults?

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This research was supported by grant WE 4836/1-1 from the German Research Foundation.

Adolphs, R., Gosselin, F., Buchanan, T. W., Tranel, D., Schyns, P., and Damasio, A. R. (2005). A mechanism for impaired fear recognition after amygdala damage. Nature 433, 68–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03086

Albert, A. M., Ricanek, K., and Patterson, E. (2007). A review of the literature on the aging adult skull and face: implications for forensic science research and applications. Forensic Sci. Int. 172, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.03.015

Aviezer, H., Bentin, S., Dudarev, V., and Hassin, R. R. (2011). The automacity of emotional face-context integration. Emotion 11, 1406–1414. doi: 10.1037/a0023578

Barret, L. F., Mesquita, B., and Gendron, M. (2011). Context in emotion perception. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20, 286–290. doi: 10.1177/0963721411422522

Bartzokis, G., Cummings, J. L., Sultzer, D., Henderson, V. W., Nuechterlein, K. H., and Mintz, J. (2003). White matter structural integrity in healthy aging adults and patients with Alzheimer disease: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch. Neurol. 60, 393–398. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.393

Boduroglu, A., Yoon, C., Luo, T., and Park, D. C. (2006). Age-related stereotypes: a comparison of American and Chinese cultures. Gerontology 52, 324–333. doi: 10.1159/000094614

Borod, J., Yecker, S., Brickman, A., Moreno, C., Sliwinski, M., Foldi, N., et al. (2004). Changes in posed facial expression of emotion across the adult life span. Exp. Aging Res. 30, 305–331. doi: 10.1080/03610730490484399

Bruce, V., and Young, A. (1986). Understanding face recognition. Br. J. Psychol. 77, 305–327. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1986.tb02199.x

Bzdok, D., Langner, R., Hoffstaedter, F., Turetsky, B. I., Zilles, K., and Eickhoff, S. B. (2012). The modular neuroarchitecture of social judgments on faces. Cereb. Cortex 22, 951–961. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr166

Calder, A. J., Keane, J., Manly, T., Sprengelmeyer, R., Scott, S., Nimmo-Smith, I., et al. (2003). Facial expression recognition across the adult life span. Neuropsychologia 41, 195–202. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00149-5

Calder, A. J., and Young, A. W. (2005). Understanding the recognition of facial identity and facial expression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 641–651. doi: 10.1038/nrn1724

Calder, A. J., Young, A. W., Keane, J., and Dean, M. (2000). Configural information in facial expression perception. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 26, 527–551. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.26.2.527

Carstensen, L. L., and Charles, S. T. (1998). Emotion in the second half of life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 7, 144–149. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10836825

Carstensen, L. L., and Mikels, J. A. (2005). At the intersection of emotion and cognition—aging and the positivity effect. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 14, 117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00348.x

Dupuis, K., and Pichora-Fuller, M. K. (2011). Recognition of emotional speech for younger and older talkers: behavioural findings from the toronto emotional speech set. Canadian Acoustics 39, 182–183. Available online at: http://jcaa.caa-aca.ca/index.php/jcaa/article/view/2471

Ebner, N. C. (2008). Age of face matters: age-group differences in ratings of young and old faces. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 130–136. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.1.130

Ebner, N. C., Gluth, S., Johnson, M. R., Raye, C. L., Mitchell, K. J., and Johnson, M. K. (2011a). Medial prefrontal cortex activity when thinking about others depends on their age. Neurocase 17, 260–269. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2010.536953

Ebner, N. C., He, Y., Fichtenholtz, H. M., McCarthy, G., and Johnson, M. K. (2011b). Electrophysiological correlates of processing faces of younger and older individuals. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 6, 526–535. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq074

Ebner, N. C., He, Y., and Johnson, M. K. (2011c). Age and emotion affect how we look at a face: visual scan patterns differ for own-age versus other-age emotional faces. Cogn. Emot. 25, 983–997. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.540817

Ebner, N. C., and Johnson, M. K. (2009). Young and older emotional faces: are there age group differences in expression identification and memory? Emotion 9, 329–339. doi: 10.1037/a0015179

Ebner, N. C., and Johnson, M. K. (2010). Age-group differences in interference from young and older emotional faces. Cogn. Emot. 24, 1095–1116. doi: 10.1080/02699930903128395

Ebner, N. C., Johnson, M. K., and Fischer, H. (2012). Neural mechanisms of reading facial emotions in young and older adults. Front. Psychol. 3:223. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00223

Ebner, N. C., Johnson, M. R., Rieckmann, A., Durbin, K. A., Johnson, M. K., and Fischer, H. (2013). Processing own-age vs. other-age faces: neuro-behavioral correlates and effects of emotion. Neuroimage 78, 363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.029

Ebner, N. C., Riediger, M., and Lindenberger, U. (2010). FACES- a database of facial expressions in young, middle-aged, and older women and men: development and validation. Behav. Res. Methods 42, 351–362. doi: 10.3758/BRM.42.1.351

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., and Ellsworth, P. (1982). “Does the human face provide accurate information?” in Emotion in the Human Face, ed P. Ekman (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 56–97.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., and Hager, J. C. (1978). Facial Action Coding System (FACS). Palo Alto, California: Consulting.

Firestone, A., Turk-Browne, N. B., and Ryan, J. D. (2007). Age-related deficits in face recognition are related to underlying changes in scanning behavior. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 14, 594–607. doi: 10.1080/13825580600899717

Fischer, H., Nyberg, L., and Bäckman, L. (2010). Age-related differences in brain regions supporting successful encoding of emotional faces. Cortex 46, 490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.05.011

Fischer, H., Sandblom, J., Gavazzeni, J., Fransson, P., Wright, C. I., and Bäckman, L. (2005). Age-differential patterns of brain activation during perception of angry faces. Neurosci. Lett. 386, 99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.002

Gross, J. J., and Levenson, R. W. (1993). Emotional suppression—physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 64, 970–986. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.970

Gunning-Dixon, F. M., Gur, R. C., Perkins, A. C., Schroeder, L., Turner, T., Turetsky, B. I., et al. (2003). Age-related differences in brain activation during emotional face processing. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 285–295. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00099-4

Harrison, V., and Hole, G. J. (2009). Evidence for a contact-based explanation of the own-age bias in face recognition. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 16, 264–269. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.2.264

He, Y., Ebner, N. C., and Johnson, M. K. (2011). What predicts the own-age bias in face recognition memory? Soc. Cogn. 29, 97–109. doi: 10.1521/soco.2011.29.1.97

Hess, U., Adams, R. B., and Kleck, R. E. (2008). “The devil is in the details: the meanings of faces and how they influence the meanings of facial expressions,” in Affective Computing: Focus on Emotion Expression, Synthesis, and Recognition, ed J. Or (I-techonline/I-Tech), 45–56. Available online at: http://www.intechopen.com/books/affective_computing/the_devil_is_in_the_details_-_the_meanings_of_faces_and_how_they_influence_the_meanings_of_facial_. doi: 10.5772/6187

Hess, U., Adams, R. B. J., Simard, A., Stevenson, M. T., and Kleck, R. E. (2012). Smiling and sad wrinkles: age-related changes in the face and the perception of emotions and intentions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1377–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.05.018

Hess, U., and Kirouac, G. (2000). “Emotion expression in groups,” in Handbook of Emotions, ed M. Lewis (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 368–381.

Hugenberg, K., Wilson, J. P., See, P. E., and Young, S. G. (2013). Towards a synthetic model of own group biases in face memory. Vis. Cogn. 21, 1392–1417. doi: 10.1080/13506285.2013.821429

Hugenberg, K., Young, S. G., Bernstein, M. J., and Sacco, D. F. (2010). The categorization-individuation model: an integrative account of the other-race recognition deficit. Psychol. Rev. 117, 1168–1187. doi: 10.1037/a0020463

Hühnel, I., Fölster, M., Werheid, K., and Hess, U. (2014). Empathic reactions of younger and older adults: no age related decline in affective responding. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 50, 136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.09.011

Hummert, M. L., Garstka, T. A., Ryan, E. B., and Bonnesen, J. L. (2004). “The role of age stereotypes in interpersonal communication,” in Handbook of Communication and Aging Research, 2nd Edn, eds J. F. Nussbaum and J. Coupland (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 91–114.

Isaacowitz, D. M., Löckenhoff, C. E., Lane, R. D., Wright, R., Sechrest, L., Riedel, R., et al. (2007). Age differences in recognition of emotion in lexical stimuli and facial expressions. Psychol. Aging 22, 147–159. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.147

Isaacowitz, D. M., and Stanley, J. T. (2011). Bringing an ecological perspective to the study of aging and recognition of emotional facial expressions: past, current, and future methods. J. Nonverbal Behav. 35, 261–278. doi: 10.1007/s10919-011-0113-6

Izard, C. E. (1979). The Maximally Discriminitive Facial Movements Coding System, MAX. Newark, DE: University of Delaware.

Jack, C. R., Petersen, R. C., Xu, Y. C., Waring, S. C., O'Brien, P. C., Tangalos, E. G., et al. (1997). Medial temporal atrophy on MRI in normal aging and very mild Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 49, 786–794. doi: 10.1212/WNL.49.3.786

Kaufmann, J. M., and Schweinberger, S. R. (2004). Expression influences the recognition of familiar faces. Perception 33, 399–408. doi: 10.1068/p5083

Keightley, M. L., Chiew, K. S., Winocur, G., and Grady, C. L. (2007). Age-related differences in brain activity underlying identification of emotional expressions in faces. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2, 292–302. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm024

Kornadt, A. E., and Rothermund, K. (2011). Contexts of aging: assessing evaluative age stereotypes in different life domains. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 66, 547–556. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr036

Kunz, M., Mylius, V., Schepelmann, K., and Lautenbacher, S. (2008). Impact of age on the facial expression of pain. J. Psychosom. Res. 64, 311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.09.010

Lambrecht, L., Kreifelts, B., and Wildgruber, D. (2012). Age-related decrease in recognition of emotional facial and prosodic expressions. Emotion 12, 529–539. doi: 10.1037/a0026827

Levenson, R. W., Carstensen, L. L., Friesen, W. V., and Ekman, P. (1991). Emotion, physiology, and expression in old age. Psychol. Aging 6, 28–35. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.6.1.28

Macchi Cassia, V. (2011). Age biases in face processing: the effects of experience across development. Br. J. Psychol. 102, 816–829. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.2011.02046.x

Magai, C., Consedine, N. S., Krivoshekova, Y. S., Kudadjie-Gyamfi, E., and McPherson, R. (2006). Emotion experience and expression across the adult life span: insights from a multimodal assessment study. Psychol. Aging 21, 303–317. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.303

Malatesta, C. Z., Fiore, M. J., and Messina, J. J. (1987a). Affect, personality, and facial expressive characteristics of older people. Psychol. Aging 2, 64–69. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.2.1.64

Malatesta, C. Z., Izard, C. E., Culver, C., and Nicolich, M. (1987b). Emotion communication skills in young, middle-aged, an older women. Psychol. Aging 2, 193–203. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.2.2.193

Malatesta, C. Z., and Izard, C. E. (1984). “The facial expression of emotion: young, middle-aged, and older adult expressions,” in Emotion in Adult Development, eds C. Z. Malatesta and C. E. Izard (London: Sage Publications), 253–273.

Malatesta-Magai, C., Jonas, R., Shepard, B., and Culver, L. C. (1992). Type A behavior pattern and emotion expression in younger and older adults. Psychol. Aging 7, 551–561. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.4.551

Mather, M., and Carstensen, L. L. (2003). Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychol. Sci. 14, 409–415. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01455

Matheson, D. H. (1997). The painful truth: interpretation of facial expressions of pain in older adults. J. Nonverbal Behav. 21, 223–238. doi: 10.1023/A:1024973615079

Minear, M., and Park, D. C. (2004). A lifespan database of adult facial stimuli. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36, 630–633. doi: 10.3758/BF03206543

Montepare, J., Koff, E., Zaitchik, D., and Albert, M. (1999). The use of body movements and gestures as cues to emotions in younger and older adults. J. Nonverbal Behav. 23, 133–152. doi: 10.1023/A:1021435526134

Murphy, F. C., Nimmo-Smith, I., and Lawrence, A. D. (2003). Functional neuroanatomy of emotions: a meta-analysis. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 3, 207–233. doi: 10.3758/CABN.3.3.207

Murphy, N. A., Lehrfeld, J. M., and Isaacowitz, D. M. (2010). Recognition of posed and spontaneous dynamic smiles in young and older adults. Psychol. Aging 25, 811–821. doi: 10.1037/a0019888

Phan, K. L., Wager, T., Taylor, S. F., and Liberzon, I. (2002). Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: a meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. Neuroimage 16, 331–348. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1087

Phillips, L. H., MacLean, R. D. J., and Allen, R. (2002). Age and the understanding of emotions: neuropsychological and sociocognitive perspectives. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 57, P526–P530. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.P526

Porcheron, A., Mauger, E., and Russell, R. (2013). Aspects of facial contrast decrease with age and are cues for age perception. PLoS ONE 8:e57985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057985

Proietti, V., Pisacane, A., and Macchi Cassia, V. (2013). Natural experience modulates the processing of older adult faces in young adults and 3-year-old children. PLoS ONE 8:e57499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057499

Raz, N. (2000). “Aging of the brain and its impact on cognitive performance: integration of structural and functional findings,” in The Handbook of Aging and Cognition, 2nd Edn, eds F. I. M. Craik and T. A. Salthouse (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 1–90.

Rhodes, M. G., and Anastasi, J. S. (2012). The own-age bias in face recognition: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol. Bull. 138, 146–174. doi: 10.1037/a0025750

Richter, D., Dietzel, C., and Kunzmann, U. (2011). Age differences in emotion recognition: the task matters. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 66, 48–55. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq068

Riediger, M., Voelkle, M. C., Ebner, N. C., and Lindenberger, U. (2011). Beyond “happy, angry, or sad?” Age-of-poser and age-of-rater effects on multi-dimensional emotion perception. Cogn. Emot. 25, 968–982. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.540812

Ruffman, T., Halberstadt, J., and Murray, J. (2009a). Recognition of facial, auditory, and bodily emotions in older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 64, 696–703. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp072

Ruffman, T., Sullivan, S., and Dittrich, W. (2009b). Older adults' recognition of bodily and auditory expressions of emotion. Psychol. Aging 24, 614. doi: 10.1037/a0016356

Ruffman, T., Henry, J. D., Livingstone, V., and Phillips, L. H. (2008). A meta-analytic review of emotion recognition and aging: implications for neuropsychological models of aging. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 32, 863–881. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.01.001

Ruffman, T., Murray, J., Halberstadt, J., and Vater, T. (2012). Age-related differeces in deception. Psychol. Aging 27, 543–549. doi: 10.1037/a0023380

Schweinberger, S. R., and Soukup, G. R. (1998). Asymmetric relationships among perceptions of facial identity, emotion, and facial speech. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 24, 1748–1765. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.24.6.1748

Schyns, P. G., and Oliva, A. (1999). Dr. Angry and Mr. Smile: when categorizazion flexibly modifies the perception of faces in rapid visual presentations. Cognition 69, 243–265. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(98)00069-9

Signorielli, N. (2004). Aging on television: messages relating to gender, race, and occupation in prime time. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 48, 279–301. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4802_7

Slessor, G., Miles, L. K., Bull, R., and Phillips, L. H. (2010). Age-related changes in detecting happiness: discriminating between enjoyment and nonenjoyment smiles. Psychol. Aging 25, 246–250. doi: 10.1037/a0018248

Sporer, S. L. (2001). Recognizing faces of other ethnic groups: an integration of theories. Psychol. Pub. Policy Law 7:36. doi: 10.1037/1076-8971.7.1.36

Sullivan, S., Ruffman, T., and Hutton, S. B. (2007). Age differences in emotion recognition skills and the visual scanning of emotion faces. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 62, P53–P60. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.P53

Suzuki, A., Hoshino, T., Shigemasu, K., and Kawamura, M. (2007). Decline or improvement? Age-related differences in facial expression recognition. Biol. Psychol. 74, 75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.07.003

Taler, V., Baum, S., and Saumier, D. (2006). “Perception of linguistic and affective prosody in younger and older adults,” in Paper presented at the Twenty-eighth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, (Vancouver), 2216–2221.

Thibault, P., Bourgeois, P., and Hess, U. (2006). The effect of group-identification on emotion recognition: the case of cats and basketball players. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 42, 676–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2005.10.006

Tsai, J. L., Levenson, R. W., and Carstensen, L. L. (2000). Autonomic, subjective, and expressive responses to emotional films in older and younger Chinese Americans and European Americans. Psychol. Aging 15, 684–693. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.15.4.684

Voelkle, M. C., Ebner, N. C., Lindenberger, U., and Riediger, M. (2012). Let me guess how old you are: effects of age, gender, and facial expression on perceptions of age. Psychol. Aging 27, 265–277. doi: 10.1037/a0025065

Weisbuch, M., and Ambady, N. (2008). Affective divergence: automatic responses to others' emotions depend on group membership. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95, 1063–1079. doi: 10.1037/a0011993

Wiese, H. (2012). The role of age and ethnic group in face recognition memory: ERP evidence from a combined own-age and own-race bias study. Biol. Psychol. 89, 137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.10.002

Wiese, H., Komes, J., and Schweinberger, S. R. (2012). Daily-life contact affects the own-age bias and neural correlates of face memory in elderly participants. Neuropsychologia 50, 3496–3508. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.09.022

Wiese, H., Komes, J., and Schweinberger, S. R. (2013a). Ageing faces in ageing minds: a review on the own-age bias in face recognition. Vis. Cogn. 21, 1337–1363. doi: 10.1080/13506285.2013.823139

Wiese, H., Wolff, N., Steffens, M. C., and Schweinberger, S. R. (2013b). How experience shapes memory for faces: an event-related potential study on the own-age bias. Biol. Psychol. 94, 369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.07.001

Wiese, H., Schweinberger, S. R., and Hansen, K. (2008). The age of the beholder: ERP evidence of an own-age bias in face memory. Neuropsychologia 46, 2973–2985. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.06.007

Williams, L. M., Brown, K. J., Palmer, D., Liddell, B. J., Kemp, A. H., Olivieri, G., et al. (2006). The mellow years? Neural basis of improving emotional stability over age. J. Neurosci. 26, 6422–6430. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0022-06.2006

Wolff, N., Wiese, H., and Schweinberger, S. R. (2012). Face recognition memory across the adult life span: event-related potential evidence from the own-age bias. Psychol. Aging 27, 1066–1081. doi: 10.1037/a0029112

Wong, B., Cronin-Golomb, A., and Neargarder, S. (2005). Patterns of visual scanning as predictors of emotion identification in normal aging. Neuropsychology 19, 739–749. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.6.739

Wright, C. I., Negreira, A., Gold, A. L., Britton, J. C., Williams, D., and Barrett, L. F. (2008). Neural correlates of novelty and face-age effects in young and elderly adults. Neuroimage 42, 956–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.015

Keywords: emotional facial expressions, facial expression decoding, older face, aging, own-age advantage, response bias, expressivity

Citation: Fölster M, Hess U and Werheid K (2014) Facial age affects emotional expression decoding. Front. Psychol. 5:30. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00030

Received: 29 October 2013; Paper pending published: 10 January 2014;

Accepted: 10 January 2014; Published online: 04 February 2014.

Edited by:

Natalie Ebner, University of Florida, USAReviewed by:

Natalie Ebner, University of Florida, USACopyright © 2014 Fölster, Hess and Werheid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mara Fölster, Clinical Gerontopsychology, Department of Psychology, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Rudower Chaussee 18, 12489 Berlin, Germany e-mail:bWFyYS5mb2Vsc3RlckBodS1iZXJsaW4uZGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.