95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychol. , 19 March 2012

Sec. Auditory Cognitive Neuroscience

Volume 3 - 2012 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00076

Julia Merrill1

Julia Merrill1 Daniela Sammler1

Daniela Sammler1 Marc Bangert1,2

Marc Bangert1,2 Dirk Goldhahn1

Dirk Goldhahn1 Gabriele Lohmann1

Gabriele Lohmann1 Robert Turner1

Robert Turner1 Angela D. Friederici1*

Angela D. Friederici1*This functional magnetic resonance imaging study examines shared and distinct cortical areas involved in the auditory perception of song and speech at the level of their underlying constituents: words and pitch patterns. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to isolate the neural correlates of the word- and pitch-based discrimination between song and speech, corrected for rhythmic differences in both. Therefore, six conditions, arranged in a subtractive hierarchy were created: sung sentences including words, pitch and rhythm; hummed speech prosody and song melody containing only pitch patterns and rhythm; and as a control the pure musical or speech rhythm. Systematic contrasts between these balanced conditions following their hierarchical organization showed a great overlap between song and speech at all levels in the bilateral temporal lobe, but suggested a differential role of the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and intraparietal sulcus (IPS) in processing song and speech. While the left IFG coded for spoken words and showed predominance over the right IFG in prosodic pitch processing, an opposite lateralization was found for pitch in song. The IPS showed sensitivity to discrete pitch relations in song as opposed to the gliding pitch in speech. Finally, the superior temporal gyrus and premotor cortex coded for general differences between words and pitch patterns, irrespective of whether they were sung or spoken. Thus, song and speech share many features which are reflected in a fundamental similarity of brain areas involved in their perception. However, fine-grained acoustic differences on word and pitch level are reflected in the IPS and the lateralized activity of the IFG.

Nobody would ever confuse a dialog and an aria in an opera such as Mozart’s “The Magic Flute,” just as everybody would be able to tell whether the lyrics of the national anthem were spoken or sung. What makes the difference between song and speech, and how do our brains code for it?

Song and speech are multi-faceted stimuli which are similar and at the same time different in many features. For example, both sung and spoken utterances express meaning through words and thus share the phonology, phonotactics, syntax, and semantics of the communicated language (Brown et al., 2006). However, words in sung and spoken language exhibit important differences in fine-grained acoustic aspects: articulation of the same words is often more precise and vowel duration considerably longer in sung compared to spoken language (Seidner and Wendler, 1978). Furthermore, the formant structure of the vowels is often modified by singing style and technique, as for example reflected in a Singer’s Formant in professional singing (Sundberg, 1970).

Both song and speech have an underlying melody or pitch pattern, but these vary in some detail. Song melody depends on the rule-based (syntactic) arrangement of 11 discrete pitches per octave into scales as described by music theory (cf. Lerdahl and Jackendoff, 1983). The melody underlying a spoken utterance is called prosody and may indicate a speaker’s emotional state (emotional prosody), determine the category of sentences such as question or statement and aid language comprehension in terms of accentuation and boundary marking (linguistic prosody). In contrast to a sung melody, a natural spoken utterance carries a pattern of gliding, not discrete, pitches that are not related to scales but vary rather continuously (for an overview, see Patel, 2008).

Altogether, song and speech, although similar in many aspects, differ in a number of acoustic parameters that our brains may capture and analyze to determine whether a stimulus is sung or spoken. The present study sets out to explore the neurocognitive architecture underlying the perception of song and speech at the level of their underlying constituents – words and pitch patterns.

Previous functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies on the neural correlates of singing and speaking focused predominantly on differences between song and speech production (overt, covert, or imagined; Wildgruber et al., 1996; Riecker et al., 2002; Jeffries et al., 2003; Özdemir et al., 2006; Gunji et al., 2007) or compared production with perception (Callan et al., 2006; Saito et al., 2006) whereas pure perception studies are rare (Sammler et al., 2010; Schön et al., 2010). Two main experimental approaches have been used in this field: either syllable singing of folksongs or known instrumental music was contrasted with the recitation of highly automated word strings (e.g., names of the months; Wildgruber et al., 1996; Riecker et al., 2002), or well-known sung folksongs were contrasted with the spoken lyrics of the same song (Jeffries et al., 2003; Callan et al., 2006; Saito et al., 2006; Gunji et al., 2007).

Despite their above mentioned methodological diversity, most of the production as well as perception studies report a general lateralization effect for speech to the left and for song to the right hemisphere. For example, Callan et al. (2006) compared listening to sung (SNG) and spoken (SPK) versions of well-known Japanese songs and found significantly stronger activation of the right anterior superior temporal gyrus (STG) for SNG and a more strongly left-lateralized activity pattern for SPK. These findings led the authors to suggest that the right or left lateralization could act as a neural determiner for melody or speech processing, respectively. Schön et al. (2010) extended this view by suggesting that within song, linguistic (i.e., words), and musical (i.e., pitch) parameters show a differential hemispheric specialization. Their participants listened to pairs of spoken words, sung words, and “vocalize” (i.e., singing on a syllable) while performing a same/different task. Brain activation patterns related to the processing of musical aspects of song isolated by contrasting the sung vs. spoken words showed more extended activations in the right temporal lobe, whereas the processing of linguistic aspects (such as phonology, syntax, and semantics) determined by contrasting song vs. vocalize showed a predominance in the left temporal lobe.

Thus, both production and perception data seem to suggest a predominant role of the right hemisphere in the processing of song due to pronounced musical features of the stimulus and a stronger left hemisphere involvement in speech due to focused linguistic processing. Notably, the most recent studies (Callan et al., 2006; Schön et al., 2010) allude to the possibility that different aspects of spoken and sung language lead to different lateralization patterns, calling for an experiment that carefully dissects these aspects in order to draw a conclusive picture on the neural distinction of song and speech perception.

Due to a restricted number and the particular choice of experimental conditions, previous studies (Callan et al., 2006; Schön et al., 2010) did not allow for fully separating out the influence of words, pitch patterns, or other (uncontrolled) acoustic parameters on the differential coding for sung and spoken language in the brain.

Particularly, when it comes to the comparison of pitch patterns between song and speech, it must be taken into account that the melodies in song and speech (most obvious when they are produced on sentence level) do not only differ in their pitch contour, but have also different underlying rhythm patterns. Rhythm differences in song and speech concern mainly the periodicity, i.e., the metric conception. Meter describes the grouping of beats and their accentuation. Temporal periodicity in musical meter is much stricter than in speech and the regular periodicities of music allow meter to serve as a mental framework for sound perception. As pointed out by Patel (2008, p. 194) “there is no evidence that speech has a regular beat, or has meter in the sense of multiple periodicities.” Brown and Weishaar (2010) described the differences in terms of a “metric conception” for song as opposed to a “heterometric conception” for speech.

Consequently, the influence of the differential rhythm patterns must be parceled out (for example by adding a respective control condition) in order to draw firm conclusions on melody and prosody processing – which has not been done so far. This is also of specific relevance because the left and right hemispheres are known to have a relative preference for temporal (rhythm) and spectral (pitch) information, respectively (Zatorre, 2001; Jamison et al., 2006; Obleser et al., 2008).

Furthermore, the methodological approaches of the reported fMRI studies were limited to univariate analyses (UVA), which mostly subtract two conditions and provide information about which extended brain regions have a greater mean magnitude of activation for one stimulus relative to another. This activation based method relies on the assumption that a functional region extends over a number of voxels and usually applies spatial smoothing to increase statistical power (Haynes and Rees, 2005, 2006; Kriegeskorte et al., 2006).

Recent methodological developments in neuroimaging have brought up multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA; Haxby et al., 2001; Norman et al., 2006) which does not only take into account activation differences in single voxels, but analyses the information present in multiple voxels. In addition to regions that react more strongly to one condition than another, as in UVA, MVPA can thus also identify brain areas in which a fine spatial pattern of activation of several voxels discriminates between experimental conditions (Kriegeskorte et al., 2006). Notably, this allows identifying the differential involvement of the same brain area in two conditions that would be cancelled out in conventional univariate subtraction methods (Okada et al., 2010).

Univariate analyses and MVPA approaches complement each other in that weak extended activation differences will be boosted by the spatial smoothing employed by the UVA, whereas the MVPA will highlight non-directional differential activation patterns between two conditions. Consequently, the combination of the two methods should define neural networks in a more complete way than each of these methods alone. Note that a considerable overlap of the UVA and MVPA results is not unusual given that the similarity or difference of activation patterns is partly also determined by their spatial average activity level (for studies that explicitly isolate and compare multivariate and univariate contributions to functional brain mapping, see Kriegeskorte et al., 2006; Okada et al., 2010; Abrams et al., 2011).

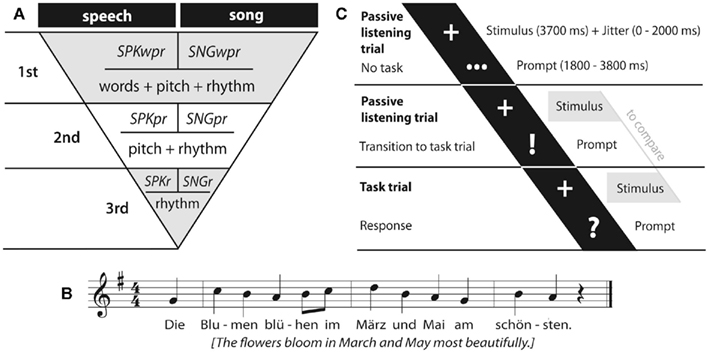

The present study used UVA as well as MVPA in a hierarchical paradigm to isolate the neural correlates of the word- and pitch-based discrimination between song and speech, corrected for the rhythmic differences mentioned above. Song and speech stimuli were constructed such to contain first all the three features (words, pitch and rhythm) of a full sung and spoken sentence, second only the pitch and rhythm patterns, and third, as a control for pitch processing, only the rhythm (see Figure 1). To assure maximal comparability, these three levels were derived from one another, spoken and sung material was kept parallel, task demands were kept as minimal as possible, and the study focused purely on perception. The hierarchical structure of the paradigm allowed us to (i) subtract each level from the above one to obtain brain areas only involved in word (first minus second level) and pitch (second minus third level) processing in either song and speech and (ii) compare these activation patterns.

Figure 1. (A) Experimental design. Six conditions in a subtractive hierarchy on three levels: first level: SPKwpr and SNGwpr (containing words, pitch pattern, and rhythm), second level: SPKpr and SNGpr (containing pitch pattern and rhythm), third level: SPKr and SNGr (containing rhythm). (B) Stimulus example. (C) Timeline of passive listening trial and task trial.

We hypothesized first that words (or text and lyrics) in both song and speech may recruit left frontal and temporal regions where lexical semantics and syntax are processed (for a review, see Bookheimer, 2002; Friederici, 2002, 2011). Second, the neural activation of prosody in speech and melody in song may be driven by its acoustic, pitch-related properties that are known to evoke a relative predominance of right hemispheric involvement (Zatorre, 2001; Jamison et al., 2006; Obleser et al., 2008). Furthermore, we expected differences with respect to gliding and discrete pitches to be reflected in particular brain signatures.

Twenty-one healthy German native speakers (14 male, mean age 24.2 years, SD: 2.4 years) participated in the study. None of the participants were professional musicians, nor had learned to play a musical instrument for more than 2 years. All control participants reported to have normal hearing. Informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki was obtained from each participant prior to the experiment which was approved by the local Ethical Committee.

The paradigm consisted of 6 conditions (with 36 stimuli each) arranged in a subtractive hierarchy: spoken (SPKwpr) and sung sentences (SNGwpr) containing words, pitch patterns, and rhythm; hummed speech prosody (SPKpr) and song melody (SNGpr) containing only pitch patterns and rhythm, as well as the speech or musical rhythm (SPKr and SNGr; see Figure 1A; sample stimuli will be provided on request).

The sentences for the “wpr” stimuli were six different statements, with a constant number of twelve syllables across all conditions. The actual text content (lyrics) was carefully selected in order to be (a) semantically plausible in both, song and propositional speech (it is obviously not plausible to sing about taking the trash out) and (b) both the regular and irregular stress patterns were rhythmically compatible with the underlying melody (a stressed or prominent point in the melody never coincided with an unstressed word or syllable; see Figure 1B).

The six melodies for the sung (SNG) stimuli were composed according to the rules of western tonal music, in related major and minor keys, duple and triple meters, and with and without upbeat depending on the sentences. The lyric/tone relation was mostly syllabic. The melodies had to be highly distinguishable in key, rhythm and meter to make the task feasible (see below).

Melodies and lyrics were both unfamiliar to avoid activations due to long-term memory processes, automatic linguistic (lyric) priming, and task cueing.

Spoken, sung (wpr) and hummed (pr and r) stimuli were recorded by a female trained voice who was instructed to avoid the Singer’s Formant and ornaments like vibrato in the sung stimuli, to speak the spoken stimuli with emotionally neutral prosody and not to stress them rhythmically in order to keep them as natural as possible.

For the rhythm (r) conditions, a hummed tone (G3) was recorded and cut to 170 ms with 20 ms fade in and out. Sequences of hummed tones were created by setting the tone onset on the vowel onsets of each syllable according to the original sung and spoken material using Adobe Audition 3 (Adobe Systems). To control the hummed stimuli (pr and r) to be exactly equal in time and pitch as the spoken and sung sentences (wpr), they were adjusted using Celemony Melodyne Studio X (Celemony Software). All stimuli were cut to 3700 ms, normalized and compressed using Adobe Audition 3 (Adobe Systems).

Across the experiment, each of the 36 stimuli was presented 6 times in a pseudo-random order (see below), interleaved with 20 baseline conditions (no sound played) and 36 task trials (requiring a response), resulting in 272 stimulus presentations in total. In an effort to avoid adaptation effects, exactly the same stimuli, stimuli with the same melody/text, or stimuli from the same level (wpr, pr, r) were not allowed to follow each other in the pseudo-randomized stimulus list.

The duration of the experiment was 34 min. For stimulus presentation and recording of behavioral responses, the software Presentation 13.0 (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) was used.

The participants were instructed to passively listen to the sounds, without being informed about the kind of stimuli, like song or speech, melody, or rhythm. To assure the participants’ attention, 36 task trials required a same/different judgment with the stimulus of the preceding trial. The stimulus of the task trial (e.g., SNGwpr) was always taken from a different hierarchical level than the preceding stimulus (e.g., SNGr) and participants were required to indicate via button press whether the two stimuli were derived from the same original sentence or song. Prior to the experiment, participants received a short training to assure quick and accurate responses.

The timeline of a single passive listening trial (for sounds and silence) is depicted in Figure 1C: The duration of a passive listening trial was 7500 ms, during which the presentation of the stimulus (3700 ms; prompted by “+”) with a jittered onset delay of 0, 500, 1000, 1500, or 2000 ms was followed either by “…” or “!” shown for the remaining trial duration between 1800 and 3800 ms. The three dots (“…”) indicated that no task would follow. The exclamation mark (“!”) informed the listeners that instead, a task trial would follow, i.e., that they had to compare the next stimulus with the stimulus they had just heard.

The timeline of a task trial was analogous to a passive listening trial except for the last prompt, a “?” indicating the time to respond via button press (see Figure 1C). Trials were presented in a fast event-related design. Task trials did not enter data analysis.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging was performed on a 3T Siemens Trio Tim scanner (Erlangen, Germany) at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig. In an anatomical T1-weighted 2D-image (TR 1300 ms, TE 7.4 ms, flip angle 90°) 36 transversal slices were acquired. During the following functional scan one series of 816 BOLD images was continuously acquired using a gradient echo-planar imaging sequence (TR 2500 ms, TE 30 ms, flip angle 90°, matrix 64 × 64). 36 interleaved axial slices (3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm voxel size, 1 mm interslice gap) were collected to cover the whole brain and the cerebellum. We made sure that participants were well able to hear the stimuli in the scanner.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging data were analyzed using SPM8 (Welcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience). Images were realigned, unwarped using a fieldmap scan, spatially normalized into the MNI stereotactic space, and smoothed using a 6 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel. Low-frequency drifts were removed using a temporal high-pass filter with a cut-off of 128 s.

A general linear model using six regressors of interest (one for each of the six conditions) was estimated in each participant. Regressors were modeled using a boxcar function convolved with a hemodynamic response function to create predictor variables for analysis.

The no-stimulus (silent) trials served as an implicit baseline. Contrasts of all six conditions against the baseline were then submitted to a second-level within-subject analysis of variance. Specific contrasts were assessed to identify brain areas involved in word and pitch processing in spoken and sung stimuli in the human brain.

For word processing, the activations for the hummed stimuli were subtracted from the full spoken and sung stimuli separately for song and speech (SPKwpr–SPKpr and SNGwpr–SNGpr). To obtain differences in word processing between song and speech, these results were compared, i.e. [(SPKwpr–SPKpr)–(SNGwpr–SNGpr)] and [(SNGwpr–SNGpr)–(SPKwpr–SPKpr)].

To identify brain areas involved in the pure pitch processing in song and speech, the activation for the rhythm condition was subtracted from the pitch–rhythm condition (SPKpr–SPKr and SNGpr–SNGr) and compared, i.e. [(SPKpr–SPKr)–(SNGpr–SNGr)] and [(SNGpr–SNGr)–(SPKpr–SPKr)].

To identify brain areas that are commonly activated by the different parameters of speech and song, additional conjunction analyses were conducted for words, i.e. [(SPKwpr–SPKpr) ∩ (SNGwpr–SNGpr)] as well as pitch patterns, i.e. [(SPKpr–SPKr) ∩ (SNGpr–SNGr)] using the principle of the minimum statistic compared to the conjunction null (Nichols et al., 2005).

The MVPA was carried out using SPM8 (Welcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience) and PyMVPA 0.4 (Hanke et al., 2009). Images were motion corrected before a temporal high-pass filter with a cut-off of 128 s was applied to remove low-frequency drifts. At this point no spatial smoothing and no normalization into MNI stereotactic space were performed to preserve the fine spatial activity patterns. Next, a contrast of interest was chosen. These contrasts included the same as with the UVA. MVPA was performed using a linear support vector machine (libsvm C-SVC, Chih-Chung Chang, and Chih-Jen Lin). For every task trial of the conditions, one image was selected as input for MVPA. To accommodate hemodynamic response, an image 7 s after stimulus onset was acquired by linear interpolation of the fMRI time series. Data were divided into five subsets each containing seven images per condition to allow for cross validation. Each subset was independently z-scored relative to baseline condition. We used a searchlight approach (Kriegeskorte et al., 2006) with a radius of 6 mm to map brain regions which were differentially activated during both conditions of interest. This resulted in accuracy maps of the whole brain. The resulting images were spatially normalized into the MNI stereotactic space, and smoothed using a 6 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel.

Accuracy maps of all subjects were then submitted to a second-level group analysis comparing the mean accuracy for each voxel to chance level (50%) by means of one-sample t-tests.

In general, analyzing multivariate data is still a methodological quest, specifically regarding the best way of performing group statistics. T-tests on accuracy maps are common practice (Haxby et al., 2001; Tusche et al., 2010; Bogler et al., 2011; Kahnt et al., 2011; Bode et al., 2012) although accuracies are not necessarily normally distributed. Non-parametric tests and especially permutation tests have better theoretical justification, but remain computationally less feasible.

All reported group SPM statistics for the univariate and the multivariate analyses were thresholded at p(cluster-size corrected) <0.05 in combination with p(voxel-level uncorrected) <0.001. The extent of activation is indicated by the number of suprathreshold voxels per cluster.

Localization of brain areas was done with reference to the Juelich Histological Atlas, Harvard-Oxford (Sub)Cortical Structural Atlas and activity within the cerebellum was determined with reference to the atlas of Schmahmann et al. (2000).

To test for the lateralization of effects and specify differences between song and speech in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and intraparietal sulcus (IPS), regions of interest (ROIs) were defined. According to the main activation peaks found in the whole brain analysis, ROIs for left and right BA 47 were taken from the Brodmann Map using the template implemented in MRIcron1. ROIs for the left and right IPS (hIP3) were taken from the SPM-implemented anatomy toolbox (Eickhoff et al., 2005). Contrast values from the uni- (beta values) and multivariate (accuracy values) analyses were extracted for each participant in each ROI by means of MarsBar2. Within-subject analyses of variance (ANOVA) and paired-sample t-tests were performed for each ROI using PASW Statistics 18.0. Normal distribution of the accuracies was verified in all ROIs using Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests (p’s > 0.643).

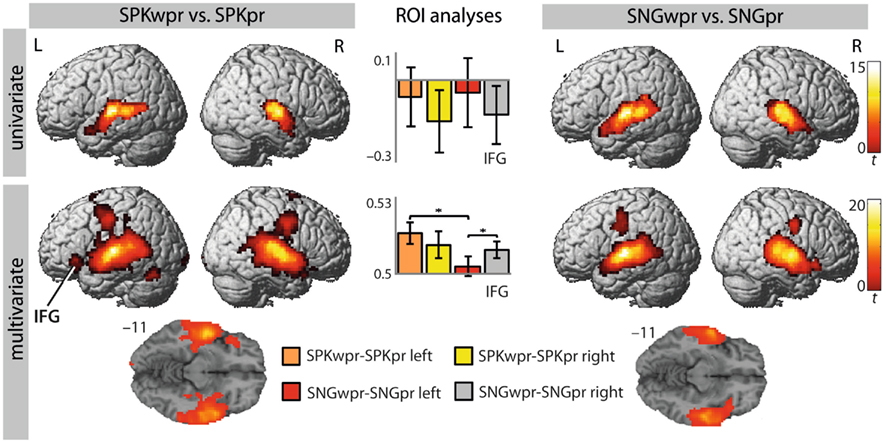

The contrasts of spoken words over prosodic pitch–rhythm patterns (SPKwpr–SPKpr) and sung words over musical pitch–rhythm patterns (SNGwpr–SNGpr) showed similar activated core regions (with more extended cluster activations for the sung stimuli) in the superior temporal sulcus (STG/STS) bilaterally and for the SNGwpr–SNGpr additionally in left medial geniculate body (see Table 1; Figure 2, top row for details).

Figure 2. Brain regions that distinguish between words and pitch–rhythm patterns in song and speech [first vs. second level: SPKwpr vs. SPKpr and SNGwpr vs. SNGpr; p(cluster-size corrected) <0.05 in combination with p(uncorrected) <0.001]. Bargraphs depict beta values (UVA) and accuracy values (MVPA) of the shown contrasts extracted from left and right BA 47. Significant differences between conditions are indicated by an asterisk (*p < 0.05). Colour scales on the right indicate t-values for each row. IFG, inferior frontal gyrus.

The overlap of these activations was nearly complete as evidenced by a conjunction analysis and no significant differences in the direct comparison of both contrasts, i.e. [(SPKwpr–SPKpr)–(SNGwpr–SNGpr)] and [(SNGwpr–SNGpr)–(SPKwpr–SPKpr)].

The MVPA revealed brain regions that distinguish significantly between words and pitch–rhythm patterns for both song (SNGwpr vs. SNGpr) and speech (SPKwpr vs. SPKpr) in the STG/STS and premotor cortex bilaterally (extending into the motor and somatosensory cortex; see Table 1 for details). For speech, in the SPKwpr vs. SPKpr contrast, additional information patterns were found in the supplementary motor area (SMA), the cerebellum, the pars orbitalis of the left IFG (BA 47), the right superior parietal lobule (BA 7), and the visual cortex (BA 17). For song, the SNGwpr vs. SNGpr contrast showed additional peaks in the pars orbitalis of the right IFG (BA 47) and the adjacent frontal operculum (see Figure 2, bottom row).

Interestingly, the results were suggestive of a different lateralization of IFG involvement in spoken and sung words. To further explore this observation, accuracy values were extracted from anatomically defined ROI in the left and right BA 47 (see Materials and Methods) and subjected to an ANOVA for repeated measures with the factors hemisphere (left/right) and modality (speech/song). This analysis showed a significant interaction of hemisphere × modality [F(1,20) = 5.049, p < 0.036], indicating that the left and right BA 47 were differentially involved in discriminating words from pitch in song and speech. Subsequent t-tests for paired samples revealed that in song, right BA 47 showed predominance over left BA 47 [t(20) = −2.485, p < 0.022], whereas the nominally opposite lateralization in speech fell short of significance (p > 0.05). Moreover, left BA 47 showed predominance for word-pitch discrimination in speech compared to song [t(20) = 2.453, p < 0.023; see bar graphs in Figure 2].

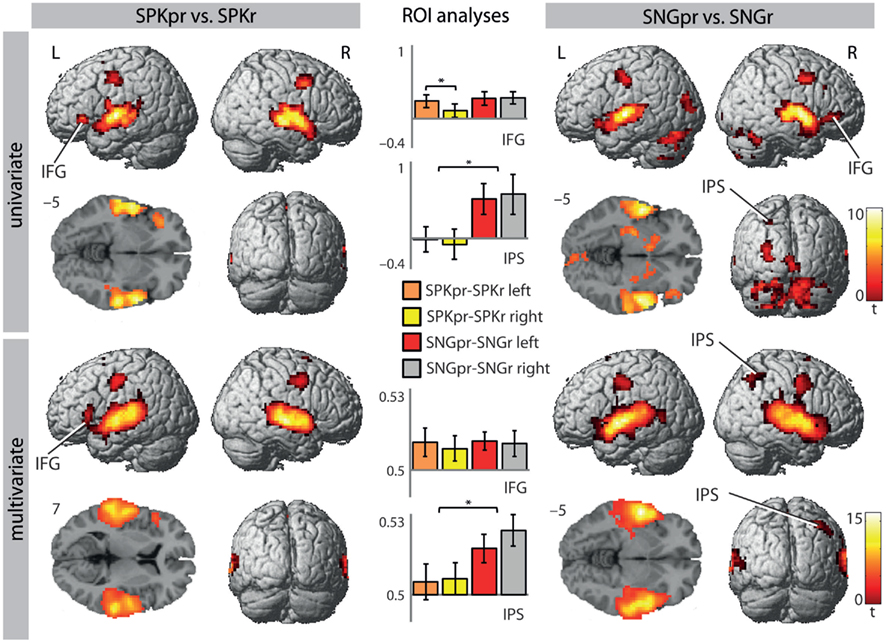

Activation for processing pitch information was revealed in the contrast of prosodic pitch–rhythm patterns vs. prosodic rhythm patterns (SPKpr–SPKr) for speech and in the contrast musical pitch–rhythm patterns vs. musical rhythm patterns (SNGpr–SNGr) for song (Table 2; Figure 3, top row). Note that these contrasts allow for investigating pitch in song and speech corrected for differential rhythm patterns. Both showed activations in the STG/STS bilaterally and in the premotor cortex bilaterally. For speech, the prosodic pitch patterns (SPKpr–SPKr) showed further activations in the pars orbitalis of the left IFG (BA 47) and the SMA.

Figure 3. Brain regions that distinguish between pitch–rhythm patterns and rhythm in song and speech [second vs. third level: SPKpr vs. SPKr and SNGpr vs. SNGr; p(cluster-size corrected) <0.05 in combination with p(uncorrected) <0.001]. Bargraphs depict beta values (UVA) and accuracy values (MVPA) of the shown contrasts extracted from left and right BA 47 and the IPS. Significant results of the ROI analysis are indicated by an asterisk (*p < 0.05). Colour scales on the right indicate t-values for each row. IFG, inferior frontal gyrus; IPS, intraparietal sulcus.

The musical pitch patterns (SNGpr–SNGr) showed further activations in the pars orbitalis of the right IFG (BA 47), the cerebellum bilaterally, the left anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the left lateral occipital cortex, the midline of the visual cortex, the right caudate nucleus, as well as a cluster in the parietal lobe with peaks in the left precuneus and the anterior IPS (see Table 2; Figure 3, top row).

A conjunction analysis of both contrasts showed shared bilateral activations in the STG/STS (planum polare) and in the premotor cortex bilaterally. Despite the differential involvement of IFG, cerebellum and IPS listed above, these differences between pitch-related processes in song and speech fell short of statistical significance in the whole brain analysis.

Again, the results were suggestive of a differential lateralization of IFG activity during pitch processing in speech and song. Therefore, an ANOVA with the repeated measures factors hemisphere (left/right) and modality (speech/song) as well as t-tests for paired samples (comparing the hemispheres within each modality) were conducted on the beta values of the contrast images extracted from ROIs in the left and right BA 47 (see Materials and Methods). This analysis showed a significant interaction of hemisphere × modality [F(1,20) = 5.185, p < 0.034], indicating that the left and right BA 47 were differentially involved in the processing of pitch patterns in speech and song. Subsequent t-tests showed that while left BA 47 was more strongly involved during spoken pitch processing than right BA 47 [t(20) = 2.837, p < 0.01], no such lateralization was found for sung pitch [t(20), p > 0.9]. Furthermore, involvement of right BA 47 was marginally stronger during pitch processing in song compared to speech [t(20) = −2.032, p < 0.056], whereas no such difference was found for left BA 47.

Considering the growing evidence that the IPS is involved in the processing of pitch in music (Zatorre et al., 1994, 2009; Foster and Zatorre, 2010; Klein and Zatorre, 2011) and as the IPS was only activated in the sung pitch contrast (SNGpr–SNGr) and not in the spoken pitch contrast (SPKpr–SPKr), an additional ROI analysis was performed to further explore differences in sung pitch and spoken pitch. Therefore, contrast values were extracted from anatomically defined ROIs in the left and right IPS (see Materials and Methods) and subjected to an ANOVA for repeated measures with the factors hemisphere (left/right) and modality (speech/song). This analysis showed a significant main effect of modality [F(1,20) = 5.565, p < 0.029] and no significant interaction of hemisphere × modality [F(1,20) = 1.421, p > 0.3], indicating that both, the left and the right IPS, were more strongly activated by sung than spoken pitch patterns.

The MVPA revealed brain regions that distinguish between pitch–rhythm patterns and rhythm patterns for both song and speech in the STG/STS bilaterally, bilaterally in the premotor cortex (extending into motor and somatosensory cortex) and SMA. For the SPKpr vs. SPKr comparison a peak in the left IFG (BA 45) was found (see Figure 3, bottom row). For SNGpr vs. SNGr additional clusters were found in the left anterior cingulate gyrus and left anterior IPS. Converging with the UVA results, the ROI analysis on the extracted contrast values revealed that the bilateral IPS was more involved in processing pitch relations in song than in speech, as shown by a significant main effect of modality [F(1,20) = 7.471, p < 0.013] and no significant interaction of hemisphere × modality [F(1,20) = 0.456, p > 0.5].

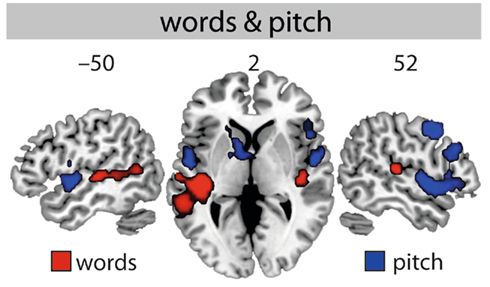

To further explore whether there are brain regions that show stronger activation for words than for pitch patterns and vice versa, irrespective of whether presented as song or speech, two additional contrasts were defined (wpr–pr and pr–r) and compared (see Table 3; Figure 4). The comparison of word and pitch processing [(wpr–pr)–(pr–r)] showed a stronger activation for words in the planum temporale (PT) bilaterally, and the left insula. The reverse comparison [(pr–r)–(wpr–pr)] showed activations for pitch in the planum polare of the STG bilaterally, the pars orbitalis of the right IFG (BA 47), the right premotor cortex, right SMA, left cerebellum, the left caudate and putamen, and the left parietal operculum.

Figure 4. Comparison of word and pitch processing in vocal stimuli. Words-pitch (red) [(wpr–pr)–(pr–r)], pitch-words (blue) [(pr–r)–(wpr–pr)][p(cluster-size corrected) <0.05 in combination with p(uncorrected) <0.001].

The goal of the present study was to clarify how the human brain responds to different parameters in song and speech, and to what extent the neural discrimination relies on phonological and vocalization differences in spoken and sung words and discrete and gliding pitches in speech prosody and song melody. Based on UVA and MVPA of the functional brain activity three main results were obtained: Firstly, song and speech recruited a largely overlapping bilateral temporo-frontal network in which the STG and the premotor cortex were found to code for differences between words and pitch independent of song and speech. Secondly, the left IFG coded for spoken words and showed dominance over the right IFG for pitch in speech, whereas an opposite lateralization was found for pitch in song. Thirdly, the IPS responded more strongly to discrete pitch relations in song compared to pitch in speech.

We will discuss the neuroanatomical findings and their functional significance in more detail below.

The IFG was involved with a differential hemispheric preponderance depending on whether words or melodies were presented in song or speech. The results suggest that the left IFG shows relative predominance in differentiating words and melodies in speech (compared to song) whereas the right IFG (compared to the left) shows predominance indiscriminating words from melodies in song. (This effect was found in the MVPA only, demonstrating the higher sensitivity of MVPA to the differential fine-scale coding of information.) The left IFG involvement in speech most likely reflects the focused processing of segmental linguistic information, such as lexical semantics and syntax (for a review, see Bookheimer, 2002; Friederici, 2002) to decode the message of the heard sentence. The right IFG involvement in song might be due to the specific way sung words are vocalized – as for example characterized by a lengthening of vowels. The right hemisphere is known to process auditory information at broader time scales than the left hemisphere (Giraud et al., 2004; Poeppel et al., 2004; Boemio et al., 2005). This may be a possible reason why the right IFG showed specific sensitivity to sung words. Alternatively, due to the non-directional nature of MVPA results, the right frontal involvement may also reflect the predominant processing of pitch in song. Although our right IFG result stands in apparent contrast to the left IFG activations observed in an UVA for sung words over vocalize by Schön et al. (2010) this discrepancy may be due to the different analysis method and stimulus material employed. Single words when they are sung as in Schön et al. (2010) may draw more attention to segmental information (e.g., meaning) and thus lead to a stronger left-hemispheric involvement than sung sentences (as used in the present study).

The processing of prosodic pitch patterns involved the left IFG (more than the right IFG), whereas melodic pitch patterns activated the right IFG (more than prosodic pitch patterns). The right IFG activation in melody processing is in line with previous results in music (Zatorre et al., 1994; Koelsch and Siebel, 2005; Schmithorst, 2005; Tillmann et al., 2006). Furthermore, this result along with the overall stronger involvement of the right IFG in pitch compared to word processing (Figure 4), is in keeping with the preference of the right hemisphere for processing spectral (as opposed to temporal) stimulus properties (Zatorre and Belin, 2001; Zatorre et al., 2002; Jamison et al., 2006; Obleser et al., 2008).

The left-hemispheric predominance for prosodic pitch is most likely driven by the language-relatedness of the stimuli, superseding the right hemispheric competence of processing spectral information. The lateralization of prosodic processing has been a matter of debate with evidence from functional neuroimaging for both, a left (Gandour et al., 2000, 2003; Hsieh et al., 2001; Klein et al., 2001), or a right hemisphere predominance (Meyer et al., 2002, 2004; Plante et al., 2002; Wildgruber et al., 2002; Gandour et al., 2003). Recent views suggest that the lateralization can be modulated by the function of pitch in language and task demands (Plante et al., 2002; Kotz et al., 2003; Gandour et al., 2004). For example, Gandour et al. (2004) found that pitch in tonal languages was processed in left-lateralized areas when associated with semantic meaning (in native tonal language speakers) and right-lateralized areas when analyzed by lower-level acoustic/auditory processes (in English speakers that were unaware of the semantic content).

Furthermore, Kotz et al. (2003) found that randomly switching between prosodic (i.e., filtered) and normal speech in an event-related paradigm led to an overall left-hemispheric predominance for processing emotional prosody, which might be due to the carry-over of a “speech mode” of auditory processing to filtered speech triggered by the normal speech trials. In line with these findings, our participants may have associated the prosodic pitch patterns with normal speech in order to do the task, leading to an involvement of language-related area in the left IFG.

On a more abstract level, the combined results on speech prosody and musical melody suggest that the lateralization of pitch patterns in the brain may be determined by their function (speech- or song-related) and not their form (being pitch modulations in both speech and song; Friederici, 2011).

The left and right IPS were found to play a significant role in processing musical pitch rather than prosodic pitch. The IPS has been discussed with respect to a number of functions. It is known to be specialized in spatial processing integrating visual, tactile, auditory, and/or motor processing (for a review, see Grefkes and Fink, 2005). It also seems to be involved in non-spatial operations, such as manipulating working memory contents and maintaining or controlling attention (Husain and Nachev, 2007).

Related to the present study, the role of the IPS in pitch processing has attracted increasing attention. In an early study, Zatorre et al. (1994) found a bilateral activation in the inferior parietal lobe for a pitch judgment task (pitch processing) and suggested that a recoding of pitch information might be taking place during the performance of that task. More recent studies extended this interpretation, claiming that the IPS would be involved in a more general processing of pitch intervals and the transformation of auditory information. This idea is supported by the findings of Zatorre et al. (2009) showing an IPS involvement in the mental reversal of imagined melodies, the encoding of relative pitch by comparing transposed with simple melodies (Foster and Zatorre, 2010), as well as the categorical perception of major and minor chords (Klein and Zatorre, 2011).

While these results suggest that the IPS involvement for pitch patterns in song reflects the processing of different interval types or relative pitch per se, it remains to be explained why no similar activation was found in speech (i.e., comparing prosody against its underlying rhythm). It could be argued that the IPS is particularly involved in the processing of discrete pitches and fixed intervals typical in song, and not when perceiving gliding pitches and continuous pitch shifts as in speech. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, no study on prosodic processing has ever reported IPS activations, eventually highlighting the IPS as one brain area that discriminates between discrete and gliding pitch as a core difference between song and speech (Fitch, 2006; Patel, 2008). Further evidence for this hypothesis needs to be collected in future studies.

The temporal lobe exhibited significant overlap between the processing of song and speech, at all different stimulus levels. Interestingly, however, words and pitch (irrespective of whether presented as speech or song) showed a different activation pattern in the temporal lobe. Beyond the antero-lateral STG that was jointly activated by words and pitch, activation for words extended additionally ventrally and posteriorly relative to Heschl’s gyrus, and activation for pitch patterns spread medially and anteriorly.

These results are in line with processing streams for pitch described in the literature. For example, Patterson et al. (2002) described a hierarchy of pitch processing in the temporal lobe. As the processing of auditory sounds proceeded from no pitch (noise) via fixed pitch towards melody, the centre of activity moved antero-laterally away from primary auditory cortex, reflecting the representation of increasingly complex pitch patterns, such as the ones employed in the present study.

Likewise, posterior temporal brain areas, in particular the PT, have been specifically described in the fine-grained analysis of spectro-temporally complex stimuli (Griffiths and Warren, 2002; Warren et al., 2005; Schönwiesner and Zatorre, 2008; Samson et al., 2011) and phonological processing in human speech (Chang et al., 2010). Accordingly, the fact that the PT in our study (location confirmed according to Westbury et al., 1999) showed stronger activation in the contrast of words over pitch for both song and speech may be due to a greater spectro-temporal complexity of the “word”-stimulus (as grounded in, e.g., the fast changing variety of high-band formants in the speech sounds) than the hummed “pitch” stimulus.

A number of brain areas that are classically associated with motor control, i.e., BA 2, 4, 6, SMA, ACC, caudate nucleus and putamen consistently showed activation in our study. This is in line with previous work showing that premotor and motor areas are not only activated in vocal production, but also in passive perception (Callan et al., 2006; Saito et al., 2006; Sammler et al., 2010; Schön et al., 2010), the discrimination of acoustic stimuli (Zatorre et al., 1992; Brown and Martinez, 2007), processes for sub-vocal rehearsal and low-level vocal motor control (ACC; Perry et al., 1999), vocal imagery (SMA; Halpern and Zatorre, 1999), or more generally auditory-to-articulatory mapping (PMC; Hickok et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2008; Kleber et al., 2010). Indeed, our participants reported that they had tried to speak or sing along with the stimuli in their head and, thus, most likely recruited a subset of the above mentioned processes.

In keeping with this, the precentral activation observed in the present study is close to the larynx-phonation area (LPA) identified by Brown et al. (2008) that is thought to mediate both vocalization and audition.

We also found effects in the cerebellum, another area associated with motor control (for an overview, see Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009). Apart from that, the discrimination between spoken words and prosodic pitch patterns (left crus I/VI lobe) as well as musical pitch patterns and musical rhythm (bilaterally, widely distributed, peaks in VI lobule) in the cerebellum fits with its multiple roles in language task (bilateral lobe VI; Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009), sensory auditory processing (especially the left lateral crus I; Petacchi et al., 2005) and motor articulation and perception and the instantiation of internal models of vocal tract articulation (VI lobe; for an overview, see Callan et al., 2007).

Activations observed in the visual cortex (BA 17, 18) seemed to be connected with processing pitch or melodic information. Previous findings support this idea, as similar regions were activated during pitch processing (Zatorre et al., 1992), listening to melodies (Zatorre et al., 1994; Foster and Zatorre, 2010), and singing production (Perry et al., 1999; Kleber et al., 2007). Note that visual prompts did not seem to be responsible, as in Perry et al. (1999) for example participants had their eyes closed, and in the current study participants followed the same visual prompts in all conditions. Following Perry et al. (1999) and Foster and Zatorre (2010), activation might be due to a mental visual imagery.

In summary, the subtractive hierarchy used in the study provided a further step in uncovering brain areas involved in the perception of song and speech. Apart from a considerable overlap of song- and speech-related brain areas, the IFG and IPS were identified as candidate structures involved in discriminating words and pitch patterns in song and speech. While the left IFG coded for spoken words and showed predominance over the right IFG in pitch processing in speech, the right IFG showed predominance over the left for pitch processing in song.

Furthermore, the IPS was qualified as a core area for the processing of musical (i.e., discrete) pitches and intervals as opposed to gliding pitch in speech.

Overall, the data show that subtle differences in stimulus characteristics between speech and song can be dissected and are reflected in differential brain activity, on top of a considerable overlap.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the MPI fMRI staff for technical help for data acquisition, Karsten Müller, Jens Brauer, Carsten Bogler, Johannes Stelzer, and Stefan Kiebel for methodological support, Sven Gutekunst for programming the presentation, Kerstin Flake for help with figures, and Jonas Obleser for helpful discussion. This work was supported by a grant from the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; Grant 01GW0773).

Abrams, D. A., Bhatara, A., Ryali, S., Balaban, E., Levitin, D. J., and Menon, V. (2011). Decoding temporal structure in music and speech relies on shared brain resources but elicits different fine-scale spatial patterns. Cereb. Cortex 21, 1507–1518.

Bode, S., Bogler, C., Soon, C. S., and Haynes, J. D. (2012). The neural encoding of guesses in the human brain. Neuroimage 59, 1924–1931.

Boemio, A., Fromm, S., Braun, A., and Poeppel, D. (2005). Hierarchical and asymmetric temporal sensitivity in human auditory cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 389–395.

Bogler, C., Bode, S., and Haynes, J. D. (2011). Decoding successive computational stages of saliency processing. Curr. Biol. 21, 1667–1671.

Bookheimer, S. (2002). Functional MRI of language: new approaches to understanding the cortical organization of semantic processing. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 151–188.

Brown, S., and Martinez, M. J. (2007). Activation of premotor vocal areas during musical discrimination. Brain Cogn. 63, 59–69.

Brown, S., Martinez, M. J., and Parsons, L. M. (2006). Music and language side by side in the brain: a PET study of the generation of melodies and sentences. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 2791–2803.

Brown, S., Ngan, E., and Liotti, M. (2008). A larynx area in the human motor cortex. Cereb. Cortex 18, 837–845.

Brown, S., and Weishaar, K. (2010). Speech is heterometric: the changing rhythms of speech. Speech Prosody 100074, 1–4.

Callan, D. E., Kawato, M., Parsons, L., and Turner, R. (2007). Speech and song: the role of the cerebellum. Cerebellum 6, 321–327.

Callan, D. E., Tsytsarev, V., Hanakawa, T., Callan, A. M., Katsuhara, M., Fukuyama, H., and Turner, R. (2006). Song and speech: brain regions involved with perception and covert production. Neuroimage 31, 1327–1342.

Chang, E. F., Rieger, J. W., Johnson, K., Berger, M. S., Barbaro, N. M., and Knight, R. T. (2010). Categorical speech representation in human superior temporal gyrus. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1428–1433.

Eickhoff, S., Stephan, K. E., Mohlberg, H., Grefkes, C., Fink, G. R., Amunts, K., and Zilles, K. (2005). A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. Neuroimage 25, 1325–1335.

Fitch, W. T. (2006). The biology and evolution of music: a comparative perspective. Cognition 100, 173–215.

Foster, N., and Zatorre, R. (2010). A role for the intraparietal sulcus in transforming musical pitch information. Cereb. Cortex 20, 1350–1359.

Friederici, A. D. (2002). Towards a neural basis of auditory sentence processing. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 6, 78–84.

Friederici, A. D. (2011). The brain basis of language: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 9, 1357–1392.

Gandour, J., Dzemidzic, M., Wong, D., Lowe, M., Tong, Y., Hsieh, L., Satthamnuwong, N., and Lurito, J. (2003). Temporal integration of speech prosody is shaped by language experience: an fMRI study. Brain Lang. 84, 318–336.

Gandour, J., Tong, Y., Wong, D., Talavage, T., Dzemidzic, M., Xu, Y., Li, X., and Lowew, M. (2004). Hemispheric roles in the perception of speech prosody. Neuroimage 23, 344–357.

Gandour, J., Wong, D., Hsieh, L., Weinzapfel, B., Van Lancker, D., and Hutchins, G. D. (2000). A crosslinguistic PET study of tone perception. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12, 207–222.

Giraud, A. L., Kell, C., Thierfelder, C., Sterzer, P., Russ, M. O., Preibisch, C., and Kleinschmidt, A. (2004). Contributions of sensory input, auditory search and verbal comprehension to cortical activity during speech processing. Cereb. Cortex 14, 247–255.

Grefkes, C., and Fink, G. R. (2005). The functional organization of the intraparietal sulcus in humans and monkeys. J. Anat. 207, 3–17.

Griffiths, T., and Warren, J. D. (2002). The planum temporale as a computational hub. Trends Neurosci. 25, 348–353.

Gunji, A., Ishii, R., Chau, W., Kakigi, R., and Pantev, C. (2007). Rhythmic brain activities related to singing in humans. Neuroimage 34, 426–434.

Halpern, A. R., and Zatorre, R. J. (1999). When that tune runs through your head: a PET investigation of auditory imagery for familiar melodies. Cereb. Cortex 9, 697–704.

Hanke, M., Halchenko, Y. O., Sederberg, P. B., Hanson, S. J., Haxby, J. V., and Pollmann, S. (2009). PyMVPA: a python toolbox for multivariate pattern analysis of f(mri) data. Neuroinformatics 7, 37–53.

Haxby, J., Gobbini, M., Furey, M., Ishai, A., Schouten, J., and Pietrini, P. (2001). Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science 293, 2425–2430.

Haynes, J. D., and Rees, G. (2005). Predicting the orientation of invisible stimuli from activity in human primary visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 686–691.

Haynes, J. D., and Rees, G. (2006). Decoding mental states from brain sensitivity in humans. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 523–534.

Hickok, G., Buchsbaum, B., Humphries, C., and Muftuler, T. (2003). Auditory-motor interaction revealed by f(mri): speech, music, and working memory in area Spt. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 15, 673–682.

Hsieh, L., Gandour, J., Wong, D., and Hutchins, G. D. (2001). Functional heterogeneity of inferior frontal gyrus is shaped by linguistic experience. Brain Lang. 76, 227–252.

Husain, M., and Nachev, P. (2007). Space and the parietal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 11, 30–36.

Jamison, H. L., Watkins, K. E., Bishop, D. V. M., and Matthews, P. M. (2006). Hemispheric specialization for processing auditory nonspeech stimuli. Cereb. Cortex 16, 1266–1275.

Jeffries, K. J., Fritz, J. B., and Braun, A. R. (2003). Words in melody: an H2 15O PET study of brain activation during singing and speaking. Neuroreport 14, 749–754.

Kahnt, T., Grueschow, O., Speck, O., and Haynes, J. D. (2011). Perceptual learning and decision-making in human medial frontal cortex. Neuron 70, 549–559.

Kleber, B., Birbaumer, N., Veit, R., Trevorrow, T., and Lotze, M. (2007). Overt and imagined singing of an italian aria. Neuroimage 36, 889–900.

Kleber, B., Veit, R., Birbaumer, N., Gruzelier, J., and Lotze, M. (2010). The brain of opera singers: experience-dependent changes in functional activation. Cereb. Cortex 20, 1144–1152.

Klein, J. C., and Zatorre, R. (2011). A role for the right superior temporal sulcus in categorical perception of musical chords. Neuropsychologia 49, 878–887.

Klein, J. C., Zatorre, R., Milner, B., and Zhao, V. (2001). A cross-linguistic PET study of tone perception in mandarin chinese and english speakers. Neuroimage 13, 646–653.

Koelsch, S., and Siebel, W. A. (2005). Towards a neural basis of music perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 9, 578–584.

Kotz, S. A., Meyer, M., Alter, K., Besson, M., and von Cramon, Y. D. (2003). On the lateralization of emotional prosody: an event-related functional MR investigation. Brain Lang. 86, 366–376.

Kriegeskorte, N., Goebel, R., and Bandettini, P. (2006). Information-based functional brain mapping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3863–3868.

Lerdahl, F., and Jackendoff, R. (1983). A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Meyer, M., Alter, K., Friederici, A. D., Lohmann, G., and von Cramon, D. Y. (2002). FMRI reveals brain regions mediating slow prosodic modulations in spoken sentences. Hum. Brain Mapp. 17, 73–88.

Meyer, M., Steinhauer, K., Alter, K., Friederici, A. D., and von Cramon, D. Y. (2004). Brain activity varies with modulation of dynamic pitch variance in sentence melody. Brain Lang. 89, 277–289.

Nichols, T., Brett, M., Andersson, J., Wager, T., and Poline, J.-B. (2005). Valid conjunction inference with the minimum statistic. Neuroimage 25, 653–660.

Norman, K. A., Polyn, S. M., Detre, G. J., and Haxby, J. V. (2006). Beyond mind-reading: multi-voxel pattern analysis of fMRI data. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 10, 424–430.

Obleser, J., Eisner, F., and Kotz, S. (2008). Bilateral speech comprehension reflects differential sensitivity to spectral and temporal features. J. Neurosci. 28, 8116–8124.

Okada, K., Rong, F., Venezia, J., Matchin, W., Hsieh, I., Saberi, K., Serences, J. T., and Hickok, G. (2010). Hierarchical organization of human auditory cortex: evidence from acoustic invariance in the response to intelligible speech. Cereb. Cortex 20, 2486–2495.

Özdemir, E., Norton, A., and Schlaug, G. (2006). Shared and distinct neural correlates of singing and speaking. Neuroimage 33, 628–635.

Patterson, R. D., Uppenkamp, S., Johnsrude, I. S., and Griffiths, T. D. (2002). The processing of temporal and melody information in auditory cortex. Neuron 36, 767–776.

Perry, D. W., Zatorre, Robert, J., Petrides, M., Alivisatos, B., Meyer, E., and Evans, A. C. (1999). Localization of cerebral activity during simple singing. Neuroreport 10, 3979–3984.

Petacchi, A., Laird, A. R., Fox, P. T., and Bower, J. M. (2005). Cerebellum and auditory function: an ALE meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 25, 118–128.

Plante, E., Creusere, M., and Sabin, C. (2002). Dissociating sentential prosody from sentence processing: activation interacts with task demands. Neuroimage 17, 401–410.

Poeppel, D., Guillemin, A., Thompson, J., Fritz, J., Bavelier, D., and Braun, A. R. (2004). Auditory lexical decision, categorical perception, and FM direction discriminates differentially engage left and right auditory cortex. Neuropsychologia 42, 183–200.

Riecker, A., Wildgruber, D., Dogil, G., Grodd, W., and Ackermann, H. (2002). Hemispheric lateralization effects of rhythm implementation during syllable repetitions: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 16, 169–176.

Saito, Y., Ishii, K., Yagi, K., Tatsumi, I. F., and Mizusawa, H. (2006). Cerebral networks for spontaneous and synchronized singing and speaking. Neuroreport 17, 1893–1897.

Sammler, D., Baird, A., Valabreque, R., Clement, S., Dupont, S., Belin, P., and Samson, S. (2010). The relationship of lyrics and tunes in the processing of unfamiliar songs: a functional magnetic resonance adaptation study. J. Neurosci. 30, 3572–3578.

Samson, F., Zeffiero, T. A., Toussaint, A., and Belin, P. (2011). Stimulus complexity and categorical effects in human auditory cortex: an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 1:241. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00241.1–23

Schmahmann, J. D., Doyon, J., Toga, A. W., Petrides, M., and Evans, A. C. (2000). MRI Atlas of the Human Cerebellum. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Schmithorst, V. J. (2005). Separate cortical networks involved in music perception: preliminary functional MRI evidence for modularity of music processing. Neuroimage 25, 444–451.

Schön, D., Gordon, R., Campagne, A., Magne, C., Astesano, C. J.-L. A., and Besson, M. (2010). Similar cerebral networks in language, music and song perception. Neuroimage 51, 450–461.

Schönwiesner, M., and Zatorre, R. J. (2008). Depth electrode recording show double dissociation between pitch processing in lateral Heschl’s gyrus and sound onset processing in medial Heschl’s gyrus. Exp. Brain Res. 187, 97–105.

Stoodley, C. J., and Schmahmann, J. D. (2009). Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neurimaging studies. Neuroimage 44, 489–501.

Sundberg, J. (1970). Formant structure and articulation of spoken and sung vowels. Folia Phoniatr. (Basel) 22, 28–48.

Tillmann, B., Koelsch, S., Escoffier, N., Bigand, E., Lalitte, P., Friederici, A. D., and von Cramon, D. Y. (2006). Cognitive priming in sung and instrumental music: activation of inferior frontal cortex. Neuroimage 31, 1771–1782.

Tusche, A., Bode, S., and Haynes, J. D. (2010). Neural responses to unattended products predict later consumer choices. J. Neurosci. 30, 8024–8031.

Warren, J. D., Jennings, A. R., and Griffiths, T. D. (2005). Analysis of the spectral envelope of sounds by the human brain. Neuroimage 24, 1052–1057.

Westbury, C. F., Zatorre, R. J., and Evans, A. C. (1999). Quantitative variability in the planum temporale: a probability map. Cereb. Cortex 9, 392–405.

Wildgruber, D., Ackermann, H., Klose, U., Kardatzki, B., and Grodd, W. (1996). Functional lateralization of speech production at primary motor cortex: a fMRI study. Neuroreport 7, 2791–2795.

Wildgruber, D., Pihan, H., Ackermann, M., Erb, M., and Grodd, W. (2002). Dynamic brain activation during processing of emotional intonation: influence of acoustic parameters, emotional valence, and sex. Neuroimage 15, 856–869.

Wilson, S. M., Saygin, A. P., Sereno, M., and Iacoboni, M. (2004). Listening to speech activates motor areas involved in speech production. Nature 7, 701–702.

Zatorre, R., Evans, A. C., Meyer, E., and Gjedde, A. (1992). Lateralization of phonetic and pitch discrimination in speech processing. Science 256, 846–849.

Zatorre, R., Halpern, A. R., and Bouffard, M. (2009). Mental reversal of imagined melodies: a role for the posterior parietal cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 775–789.

Zatorre, R. J. (2001). Neural specializations for tonal processing. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 930, 193–210.

Zatorre, R. J., and Belin, P. (2001). Spectral and temporal processing in human auditory cortex. Cereb. Cortex 11, 946–953.

Zatorre, R. J., Belin, P., and Penhune, V. B. (2002). Structure and function of auditory cortex: music and speech. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 6, 37–46.

Keywords: song, speech, prosody, melody, pitch, words, fMRI, MVPA

Citation: Merrill J, Sammler D, Bangert M, Goldhahn D, Lohmann G, Turner R and Friederici AD (2012) Perception of words and pitch patterns in song and speech. Front. Psychology 3:76. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00076

Received: 11 November 2011; Accepted: 01 March 2012;

Published online: 19 March 2012.

Edited by:

Pascal Belin, University of Glasgow, UKReviewed by:

Matthew H. Davis, MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, UKCopyright: © 2012 Merrill, Sammler, Bangert, Goldhahn, Lohmann, Turner and Friederici. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Angela D. Friederici, Department of Neuropsychology, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Stephanstraße 1a, 04103 Leipzig, Germany. e-mail:YW5nZWxhZnJAY2JzLm1wZy5kZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.