94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Psychol. , 20 June 2011

Sec. Psychoanalysis and Neuropsychoanalysis

volume 2 - 2011 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00125

Mathieu Arminjon1,2*

Mathieu Arminjon1,2*In the 1980s, the terms “cognitive unconscious” were invented to denominate a perspective on unconscious mental processes independent from the psychoanalytical views. For several reasons, the two approaches to unconscious are generally conceived as irreducible. Nowadays, we are witnessing a certain convergence between both fields. The aim of this paper consists in examining the four basic postulates of Freudian unconscious at the light of neurocognitive sciences. They posit: (1) that some psychological processes are unconsciously performed and causally determine conscious processes, (2) that they are governed by their own cognitive rules, (3) that they set out their own intentions, (4) and that they lead to a conflicting organization of psyche. We show that each of these postulates is the subject of empirical and theoretical works. If the two fields refer to more or less similar mechanisms, we propose that their opposition rests on an epistemological misunderstanding. As a conclusion, we promote a conservative reunification of the two perspectives.

Since Freud’s time psychoanalysts have allowed a major gap to grow between psychoanalysis and other scientific approaches. The following discussion is representative of a larger pattern in the (non) dialog between psychoanalysis and neuro-biology: Edelman (1992), in Bright Air, Brilliant Fire, described the conversation he used to have with Jacques Monod on Freud. The latter used to claim being entirely aware of his motives: “and entirely responsible for [its] actions. They are all conscious.” Edelman, an admiring of Freud’s, once responded to him in exasperation, “Jacques, let’s put it this way. Everything that Freud said applies to me, and none of it to you.”

Both Edelman and Jacob are materialists, at least naturalists. Does it mean that for them, the existence of the Freudian unconscious depends on the opinion we have on Freud’s theories and not on facts? Moreover, if the two biologists share a more or less similar brain, can they have two different kinds of unconscious; among which only one (the cognitive one) is scientifically observable? The aim of this article is to review out the empirical and theoretical convergences between the two fields pleading in favor of a common and objective representation of unconscious processes (see Table 1).

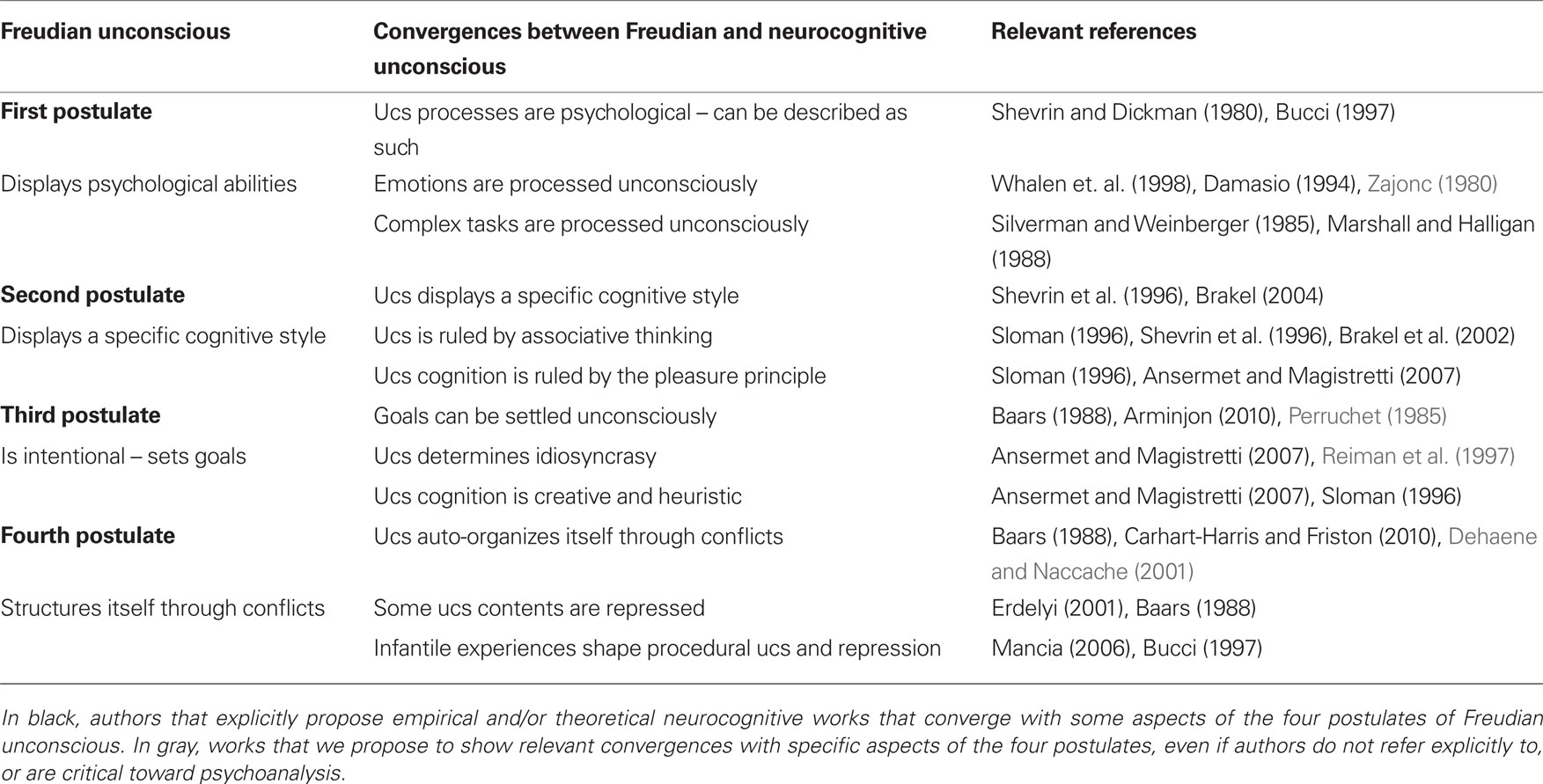

Table 1. Labels attached to unconscious (ucs) in the neurocognitive literature, aligned on the four postulates of Freudian unconscious.

Some researchers have already attempted to consider Freudian hypotheses at the light of cognitive science and neuroscience (Figure 1). Among them, Shevrin and Dickman (1980), in a seminal paper, started out from the common consensus that defines unconscious processes are (1) psychological events that are unknown to the patient but that actively affect its behavior, and adduced empirical data in favor of the more challenging Freudian postulate that (2) unconscious processes are ruled by specific laws of organization. We find this strategy – which take the basic Freudian postulates as suggestions to progressively define and evaluate unconscious life – to be extremely helpful. Thus, along the same lines, we first review cognitive and neuroscience data in favor of the first two postulates, and then we propose two others postulates to round out the Freudian paradigm: (3) the unconscious processes are goal directed; and (4) the unconscious processes are conflicting. In conclusion we propose that current experimental and theoretical works reveal that the opposition between Freudian and cognitive unconscious rests on a methodological misunderstanding.

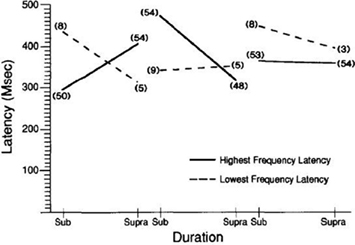

Figure 1. Relationship between latency and duration for highest and lowest frequencies by word category. (Left) Unconscious conflict words (U); (middle) conscious symptom words (C); (right) Osgood unpleasant words (E–). Numbers in parentheses are the frequency averages.

One of the first and most persistent criticisms of Freud is that the existence of unconscious representations is self-contradictory. More recently, functionalism has articulated claims that are structurally homologous to Freud’s, according to which cognition is a sub-personal computation of internal representations. Some philosophers still object to such talk, on the basis of the supposition that representation is by nature conscious (Searle, 1992). Recently, psychologists (Greenwald, 1992; Loftus and Klinger, 1992) have posed this question in terms of whether the unconscious is smart or dumb. In other words, the question of whether unconscious processes can be said to be psychological depends on what extent they are as “intelligent” as conscious ones. In this section we aim to review the principal works showing that unconscious processes are neither “dumb,” nor limited to primitive or weak forms of cognition.

The philosopher Dennett claims that psychological representations are not mental entities coded in cognitive or biological systems (Dennett, 1987). They refer to psychological descriptions cuing biological regulation traits, which are not psychological per se. Shevrin and Dickman (1980) bites the bullet and proposes that: “by psychological we mean simply that all categories of descriptive terminology applicable to conscious experience can also be applied to unconscious processes.” Such a statement is consistent with Dennett’s criticism of realistic psychology, and in line with the central tenet of Freud’s epistemology (Arminjon, 2010). As a matter of fact we have only indirect experience of a psychological unconscious, inferred from overt behaviors. Obviously, it has been one of the most promising Freudian contributions to talk about, at least heuristically, unconscious “perceptions,” “judgments,” “affects,” and so forth. But the question now is whether those heuristic concepts, applied to the unconscious, are consistent with neurocognitive data.

Brain imaging has shown that many subliminal stimuli activate brain regions without the subject being able to report those influences. For example, Whalen et al. (1998) presented pictures of human faces bearing fearful or happy expressions that were sequenced 33 ms before neutral faces that backward masked the face. Respondents were then asked about the human facial expressions and did not report seeing the fearful or happy faces. Nevertheless, the emotionally charged human faces triggered the subject’s amygdalae. Hence, there is reason to think that affective stimuli can cause effects on the subliminal level, and certain stimuli – say, fearful faces – are more intensely received than other ones. This in itself indicates some primitive hierarchizing organization. But how complex is that organization? Are emotional effects too simple for unconscious processes to be called smart, that is, to make discriminations based on an autonomously produced structure?

The study of patients with brain damage has brought out evidence about even more complex unconscious processes. Patients with damage to primary visual cortex are able to make accurate pointing movements toward object they report not seeing. The classic research of Goodale and Milner (1992)has reported that while blind sight subjects consciously express impairment in finding and seeing mobile slots, they still succeed in posting a card in it. Hence, unconscious visual perception is able not only to deal with basic one-dimensional images, but also with three-dimensional data like shape, orientation, size, etc. These results are in line with the hypothesis of two visual neural pathways by Ungerleider and Mishkin (1982): the ventral one processing conscious representations allowing object identification and the dorsal one, unconsciously analyzing the visual field in a pragmatic way.

The work of Goodale and Milner and the two visual pathways hypothesis not only show the material mechanism by which unconscious processing of complex representations occurs, but do so in maintaining a clear-cut distinction between upper and higher processing levels. Marshall and Halligan (1988) have proceeded further in the realm of higher-level processing. They chose for their experiment a patient who suffered from lesions on the right side of the brain, which was expressed in unilateral neglect, a condition in which the patient turns away from, forgets or ignores objects in the contralesional space. To test the cognitive processing of unimpaired sensorimotor inputs, a patient with unilateral neglect was presented with two line drawings of a house, one above the other. Sometimes they were identical, and sometimes one of the houses was on fire. When the flames came from the right hand side of the house, she correctly identified whether the pictures were the same or different. When the flames came from the left hand side of the house, however the other house was not on fire, she identified them as the same. However, when asked which house she would prefer to live in, 80% of the time, she chose the house that was not on fire, even though she judged them to be the same1. These answers seem to show an “unconscious awareness” of the sensory data she received through her healthy ventral pathway and primary cortex. Two conclusions can be drawn. First, these findings suggest that the ventral pathway’s complex representational faculties could be processed unconsciously. Second, it seems that the differences between unconscious and conscious processes are not strictly determined by anatomical and hierarchical reasons. Thus, from the functional point of view, the richness of unconscious processes may stem from their capacities to perform the tasks usually taken as necessitating consciousness. The latter conclusion contrasts with the claim, based upon the evolution of brain development, according to which “intelligent” conscious processes probably are based on such recent brain arrangements as the forebrain, while unconscious ones might take place within primitive structures as the brainstem. We will see in Sections “Third Postulate: Unconscious Intentions or Goal-directed Unconscious Processes” and “Fourth Postulate: Conflict as a Cause of Psychic (Auto)Organization” how the automatic/controlled dichotomy is another formulation of the primitive-poor/recent-rich opposition.

Postulating the existence of unconscious processes supposes admitting psychic continuity and determinism. It means that psychological discontinuities – displayed by symptoms, parapraxes, gaps, and so forth – can be explained by unconscious causes. As Shevrin et al. (1996) puts it: “anything properly described as psychological can potentially provide psychological explanations and causes.” So, to be considered as psychological, unconscious representations might have intentional (at least intentional-like) effects on conscious cognition. Since Stroop’s (1935) paper about interference in serial verbal reactions, we know that unconscious semantic processing does interfere with overt semantic tasks. If subjects are asked to say the color of words as faster as they can, for instance saying red when the presented word “blue” is painted in red, responses are slower when meaning and colors are incongruent and faster when congruent (for example when the word “red” is painted in red). The reason that response latency increases is that the consciousness must necessarily repress the automatic semantic analysis of the word.

Numerous studies have confirmed these unconscious causal effects, especially those investigating subliminal effects. Priming is defined as a non-conscious form of memory that involves a change in the ability to identify, produce, or classify an item as a result of a previous encounter with it. Zajonc (1980) has shown how emotional stimuli of which we are unaware “color” our judgments. For example, pictures of smiling or scowling faces were subliminally presented to subjects prior to the task of rating the attractiveness of Chinese ideographs. Not only the affective values of priming had effects on the choice of the targets, but also suboptimal stimulations impacted judgments differently than optimal ones. Murphy and Zajonc (1993) report priming stimuli to induce “free floating” effects on non-specific objects. In contrast, optimal ones induced cognitive constraints that permitted directing affective priming onto specific targets. The limited precision of unconscious affects is paralleled by the limitation of unconscious cognitive capacities. For instance, Sperling (1960) presented subjects a brief flash of 12 letters. The subjects succeeded in reporting a limited number of them (on average, about five). The point, here, is that subjects “unconsciously choose” the letters to report. As a matter of fact, all the items had to be unconsciously represented before being selected. It is noteworthy that measurements show that the longer the time between the exposure and the report is important, the weaker are the subjects to report the items they have seen. Thus, the non-selected items have vanished from memory during the remembering task. From those limited memorial capacities, we can conclude that if unconscious processes are not dumb, it is even too optimistic to endow them with full intelligence2.

Nevertheless, one can ask whether those studies are methodologically consistent with the way Freud theorized in terms of unconscious processes. Sperling’s study simply shows how conscious attention is necessary for items to be encoded, but leaves open the question whether unconscious processes are able to actively perform complex tasks (we will review debates on unconscious learning in the Third Postulate: Unconscious Intentions or Goal-directed Unconscious Processes). On the other hand, one may ask whether the subliminal paradigm, as it is commonly used, is adequate to evaluate the Freudian theory especially as it insists on endogenous motives linked with an idiosyncratic inner life (Arminjon et al., 2010). Even if we admit that awareness is a prerequisite to perform tasks with unknown and neutral stimuli, we can imagine specific stimuli to have complex impacts on the subjects’ inner life. What might happen with cognitive or affective stimuli having connections or entering in “resonance” with the patient’s affectivity? Would they have a merely diffuse influence, or even vanish as rapidly as in the Sperling’s task? Such questions are difficult to answer empirically, principally because of the methodological difficulties one encounters when trying to set up experiments on subjectivity. A psychoanalytic-style study (Silverman and Weinberger, 1985) has nevertheless shown how such a subliminal text as “mommy and I are one” has a positive effect on self-motivation that is lacking when we substitute a more neutral phrase like “people are walking” and while a negative one such as “destroy mother” has a destructive effect. Meta-analysis has shown the effect to be reproducible, but the reasons why are still challenged (Hardaway, 1990; Weinberger and Hardaway, 1990). Numerous researchers have claimed such phrases to be far too complex for unconscious cognition. For instance, Greenwald and Liu (1985) and Draine (1997) have shown two-word grammatical combinations to be beyond the analytic powers of unconscious cognition. The subliminal phrase might have subliminal effect only in virtue of the words’ valence taken isolatedly. Nevertheless, other phrases have been tested and have never displayed such effect (Greenwald, 1992).

It is noteworthy that, in this study, the stimulus is not idiosyncratic. Yet, its universal affective valence might compensate for its generality. If the unconscious seems to be limited in processing complex representations, we might ask whether affective idiosyncratic values influence, for instance, the number of items one can retrieve. Anyway, the study of unconscious capacities, as affective processing or memory, might offer some surprising results if one chooses stimuli that have specific connections to the subjects’ inner life. This epistemological point emphasizes that we cannot infer unconscious is dumb from its incapacity to perform what we do consciously. In others words, one of the most important Freudian contribution consists in having apprehended unconscious per se and not such as the strict negation of consciousness. Here, one finds a dimension for research in which the psychoanalytical insistence on subjective conditions of stimuli perception might inspire cognitive sciences.

The analysis of the first postulate has produced evidence of particularities of unconscious and conscious processes from numerous psychological studies. A rule of thumb is that unconscious processes are more sensitive to affective stimuli, whereas conscious processes involve more complex representational processing. Thus, each seems to display a specific kind of functioning. To introduce the relevance of the second psychoanalytic postulate in the current scientific context, we need to keep in mind how Freudian concepts have different extensions if considered from the first or the second topic perspectives – that is, from the “id” and the “ego.” Freud introduced these two concepts to reconfigure the boundaries of the unconscious–conscious dichotomy. The theory states that some aspects of the Id may become conscious, while some of the ego may be unconscious. Thus, the shift from reducing unconscious determinants to the sole repressed representations to a descriptive cognitive topology has left open room for a plurality of unconscious processes (including the cognitive one?). According to Carhart-Harris and Friston (2010) the Id overlaps the characteristics Freud attributed to unconscious system. However, the Id might nominate a system subserving a specific mode of cognition, more than a psychic region or apparatus. In the following section we aim to show how such a perspective leads unconscious processes to be understood as an alternative type of cognition better than a weakened one.

Given the observations he made in his clinical practice, Freud theorized that psychosis, dreams, and free associations reveal a mode of cognition ordinarily suppressed or inhibited. As Freud (1936) puts it, in the unconscious, “the so-called “primary process” prevails, there is no synthesis of ideas, affects are liable to displacement, opposites are not mutually exclusive and may even coincide and condensation occurs as a matter of course. The sovereign principle is (…) that of obtaining pleasure.” In addition, the primary process is regarded as timeless, and irrational: “there are in this system no negation, no doubt, no degrees of certainty” (Freud, 1915c). This brings up the question: what are the current reasons for postulating two separate mode of cognition?

An interesting experiment addressing this question has been performed by Shevrin et al. (1996). In spite of being only based on subliminal and supraliminal stimulations, authors have respected the Freudian paradigm in working around the limits encoded in the protocols of normal psychological experiments, which are generally and intentionally blind to the individual differences that are claimed as determinants in psychoanalytical clinical work. Shevrin and his associates tried to test the power of idiosyncratic stimuli while working on subliminal perception, generally using universal emotional ones (i.e., those triggering the same emotional reactions in the normal subject). They have constituted lists of affect-laden words selected by clinicians on the basis of extensive interviews of patients. One list referenced the conscious articulation, on the patient’s part, of their psychic conflicts; the second referenced their unconscious psychic conflicts. Two conditions were evaluated:(1) words linked to the participants’ unconscious conflicts, presented subliminally and supraliminal, (2) words tied to their conscious symptoms, presented subliminally and supraliminally. The subject’s ERPs (evoked-response potential) were recorded. The results show different patterns of responses triggered by subliminal and supraliminal exposure (Figure 2). The unconscious conflict words presented subliminally showed a specific time–frequency pattern – high frequencies appear before lower ones – the conscious conflict words presented supraliminally, displayed a reverse pattern. In the supraliminal condition, the patterns for both categories of words were reversed too. Results suggest both kinds of words being associated and processed differently. Shevrin and his associates concluded from this experiment that these promising neurobiological evidence points to the existence of two separate and hermetic systems.

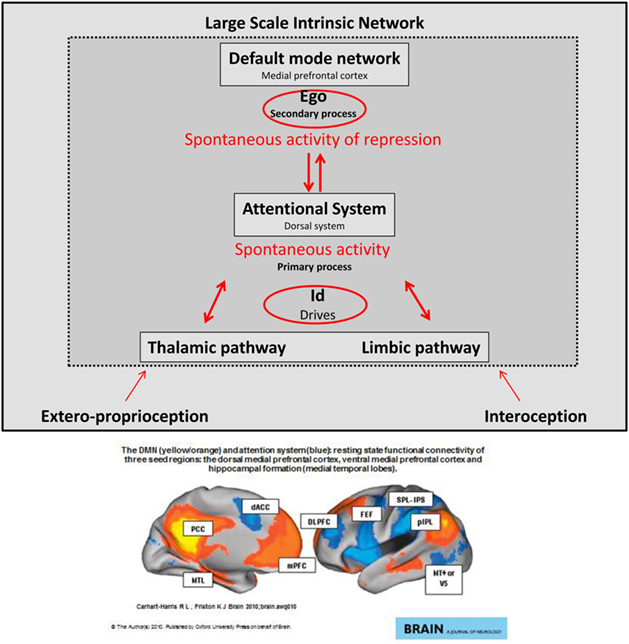

Figure 2. (Above) Convergences between Freud’s second topic and brain’s Large Intrinsic Network, after Carhart-Harris and Friston (2010). (Below) The default network (yellow/orange): the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, ventral medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal formation, when activated are correlated with the deactivation of the attentional system (blue): superior parietal lobule, intraparietal sulcus, the motion-sensitive middle temporal area, the frontal eye fields, the dorsal anterior cingulate, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the ventral premotor cortex, and the frontal operculum.

More generally, the existence of two psychic modes has ceased to be merely an exotic Freudian claim, even if still challenged (Shanks, 2010 for a review). The tenants of the dual-processing theories posit a similar statement acknowledging Freud being one of the first (among others) to posit the existence of two distinct modes of psychic functioning (for a review on dual-processes theories, see Evans, 2008). Despite the fact that there are major disputes among advocates of dual-processing theories, the common statements make a clear distinction between cognitive processes that are fast, automatic and unconscious, and those that are slow, deliberative and conscious. Such a statement, appeared in the 1970s (Posner and Snyder, 1975; Schneider and Shiffrin, 1977), has emerged as a compromise solution to the old debate on the mechanism of cognition, whether it is best taken as a composite of parallel processors or as a controlled, computer-like, sequential computation. If the former hypothesis seems to be more neurobiologically realistic, the latter still might best account for the phenomenological conscious experience. In the context of the present essay, it is noteworthy that numerous authors have showed the two modes of cognition to be reifiable, complementary, and, sometime, to be conflicting. The first is generally supposed to be rule-based, i.e., to describe the world by capturing causal, logical, hierarchical structures (Sloman, 1996). The second is thought to be associative, i.e., encoding statistical regularities, drawing inferences on the basis of similarity and contiguity. Medin et al. (1990) have proposed those cognitive modes to entail two kinds of categorization: attributional and relational similarities. For instance, categorization according to relational similarities associates whales with mammals on account of their obeying the rules defining mammals as vertebrates, air breathing, placental animals – but the categorization by attributional similarities associates whales with fishes. Similarly, “cigars” and “cigarets” belong to the same category in respect of their relational similarities, but cigars may be attributionally associated with phalluses, by reason of salient and not conceptual similarities. Brakel et al. (2002) have proposed to use Medin experimental design to test three hypotheses drawn from the assumption that primary processes use attributional categorizations and secondary processes use relational ones. In accordance with Freud’s view, studies show (1) that attributional categorization predominates when stimuli are presented subliminally, whereas relational categorization prevails when stimuli are presented supraliminally. Moreover, Freud hypothesized that the child, at age seven, experiences a mental change that results in the dominance of the primary process over the secondary ones. As predicted, (2) the same categorizing task shows the predominance of attributional categorization until about the age of seven. Lastly, (3) it has been confirmed that patients with anxiety disorders display a marked tendency to favor attributional categorization. To sum up, the primary process might be an early cognition mode inhibited by the secondary ones, especially because of cognition and cultural maturation. Both modes might process in parallel, sometime dominating in abnormal psychological states or during specific conscious states.

Evidently, the existence of two cognitive styles seems well admitted. The irrational nature of primary processes – i.e., not obeying the principle of non-contradiction – has to be acknowledged by contrast with the ruled-based function of secondary process. The timeless characteristic might be seen as an aftermath of the primary process tolerance for contradiction. We can hypothesize that the sense of time depends on the causal nature of secondary process thinking. At a neurobiological level, Kaplan-Solms and Solms (2000) have proposed “the ventromesial frontal cortex [to] perform the fundamental economic transformation that inhibits the primary process of the mind.” In fact, the authors report cases of bilateral ventromesial damage that correlates with contradictions in patients’ thought and separate temporal events amalgamation. Kaplan-Solms and Solms conclude that the ventromesial cortex underpins the functions Freud attributed to the ego.

Some neuroscientists even acknowledged the Freudian perspective to represent a more consistent biological model because of its inclusion of motivations or drives. As Sloman (1996) puts it, Freud “describes a primary process in which energy spreads around the psyche, collecting at ideas that are important to the individual and making them more intensive. He held this process responsible for channeling wish fulfillment and pain avoidance. On the other hand, a person must try to satisfy this urges in a world full of obstacles and boundaries. Gratification must sometimes be delayed. Inhibiting this primary process, and thus making both gratifications more likely in the long run and behavior more socially acceptable, is secondary process thought, governed by the reality principle.”

As mentioned by Sloman, the primary process is ruled by the pleasure principle, and not by reality. In its Project for a scientific psychology, Freud speculated that unicellular organisms are governed by the need to avoid excitation (Arminjon et al., 2010). As a consequence, he supposed that pluricellular organisms cannot evade inner stimuli without splitting themselves. Consequently, they have to balance excitations to low level. This biological conception can be seen as a homeostatic proto-theory applied to psyche. The natural tendency of the cells (or as we would say, neurons) is to avoid energy accumulation by discharging it. This idea led Freud to imagine the brain as having to bind energy in order to reach the minimal possible energetic state. Hence, the primary process might be characterized by “motile” or “free” energy, diffused throughout the whole neural system. Freud hypothesized that in order to perform a specific action, the secondary process has to inhibit (to bind) the mobile energy. Thus, the inhibition is processed by the formation of learning pathways. However, Freud imagined the Ego to auto-organize itself in this way, by inhibiting free energy. For instance, an inner need is linked to motor representations that previously led to satisfaction. Thus, when they feel angriness; newborns activate these encoded pathways and hallucinate the desired satisfaction. This pseudo-satisfaction might represent a short-term relief while waiting for the real satisfaction. Energy accumulation might explain the emergence of goal representation. Yet, the real question is not to determine the optimal strategy for achieving satisfaction, but how to inhibit the irrelevant detours. Freud has resolved the problem by referring to Helmholtz’s model according to which the state of the selection and improvement of actions at time t1 is derived from the comparison of previously successful actions, intentions, motor sensations, and/or perceptions. For instance, the hallucination or activation of the motor patterns can be taken as a prediction of the desired states. In case of non-congruence between intentions and actions in the aftermath, the system has to select other motor patterns or to improve it. In any cases, both necessitate inhibition.

New perspectives have been brought out on the “free-energy” model (Friston et al., 2006). Raichle and Snyder (2007) have shown that the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the inferior parietal lobule, the lateral and inferior temporal cortex and the medial temporal lobes constitute the “default mode network” underlying self-referential processing and autobiographical recollection. It has been proposed (Kaplan-Solms and Solms, 2000) that these structures, including the ventromesial frontal cortex, perform the ego functions. As a matter of fact, there is a low degree of connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the medial temporal lobe in childhood that increases during the brain development. This development is hypothesized to be related to the dynamic control and modulation of hedonic and emotional functions. According to a recent article by Carhart-Harris and Friston (2010), “the brain uses internal hierarchical models to predict its sensory input and suggests that neuronal activity (and synaptic connections) try to minimize the ensuing prediction error or (Helmholtz) free energy.” The higher-level processing might form predictions from sensory input and convey them backward to low-level structures (Figure 3). As a consequence, free energy or prediction error is reduced in lower-level systems so as to optimize the representation of the inner or outer world, that is to say, of the nature and the origin of stimuli. The prediction-error reduction is conjectured to explain how biological systems display homeostasis, understood as the maintenance of a constant low energetic basal state. In a way, equilibrium has to be maintained between primary and secondary processes. The Ego role of the medial prefrontal cortex seems to be confirmed by its connectivity reduction in schizophrenia (Whitfield-Gabrieli et al., 2009) or the necessity to activate the medial prefrontal cortex to inhibit memories in posttraumatic disorders (Shin et al., 2006). In other words, in normal conditions, primary and secondary processes have reciprocal and equilibrated influences. Nevertheless, in pathological states, the pleasure principle might have oversized effects, that is to say, may allow irrational, a temporal, and associative cognition, instead of the reality principle, dominate. Hence, the dynamic constraints exerted by the two cognitive styles Freud imagined appear to be corroborated by current speculative models of localized brain function and several neurological facts. Most importantly, the way the two modes interact and neutralize themselves may condition a range of impaired states, from the eruption of some elements from the primary process to the total loss of the reality principle.

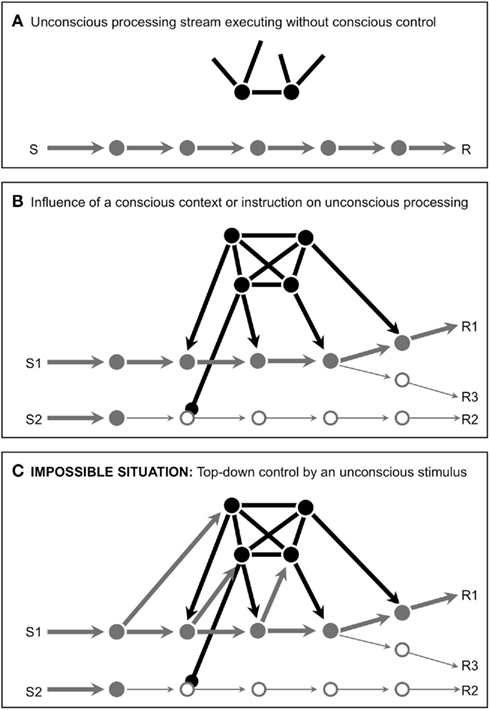

Figure 3. Since the study by Merikle, unconscious processes are said to be unable to influence conscious processing without being reportable, after Dehaene and Naccache (2001). (A) Unconscious processing stream executing without conscious control. (B) Influence of a conscious context or instruction on unconscious processing. (C) Impossible situation: top-down control by an unconscious stimulus.

The existence of two distinct modes of cognition is generally accepted in the scientific community, even if the specific characteristics of each mode are still a matter of dispute. If we suppose, as did Freud, that unconscious processes are complex, psychological, and cognitively independent and exert a causal influence on consciousness, the question becomes whether it makes sense to impute intentionality and goal directedness to the unconscious. As we have seen, the general assumption makes a clear-cut distinction between immediate, automatic and unconscious processes and those that are mediated, deliberative and conscious. Only the latter are generally admitted to match with the feelings associated with conscious control. In this section, we want to show that debates concerning the existence of unconscious intentions have led numerous researchers to challenge the distinction between automatic and control systems. On the one hand the impossibility for unconscious intention to be set up and perform out of conscious control is now challenged. On the other hand, the automaticity of unconscious processes is constructed in opposition with the apparent control consciousness seems to exert. Challenging these postulates leads to a new view concerning brain and mind organization with repercussions for how we are to understand unconscious processes and the role of consciousness.

Posner and Snyder (1975) produced a dual-processing theory according to which recognition of a target stimulus first proceeds unconsciously. During the first step, that is to say prior to the threshold of awareness, a stimulus is compared to the others encoded in long-term memory. Such a position is compatible with the associative and distributed characterization of unconscious processes. It supposes the same stimuli to be encoded in different areas, in different codes and processed in parallel. Then, consciousness might impose: “a serial order upon what are essentially widespread parallel processes initiated by a stimulus” (Posner et al., 1973). Posner’s model has helped form a dogma according to which conscious attention is a prerequisite to any kind of voluntary control exerts on unconscious automatic processes. The study by Merikle et al. (1995) is one of the best illustrations of the central role attributed to consciousness in the setting of a cognitive strategy. Like the Stroop task, subjects were asked to classify a colored string preceded by a prime word naming the color. The Stroop effect was obtained when the situation presented congruence between names and colors in comparison to non-congruence. But the reverse effect appeared when manipulating the predictability of congruent matches, for instance in presenting 75% of incongruent trials. The subject responded faster by predicting likely outcomes. However, if the pairs were presented subliminally, the effect collapsed and the Stroop effect returned to normal. As Dehaene and Naccache (2001)conclude: “we tentatively suggest, as a generalization, that the strategic operations which are associated with planning a novel strategy, evaluating it, controlling its execution, and correcting possible errors cannot be accomplished unconsciously” (Figure 4). In other words, no intentional strategy can be set up unconsciously. Such conclusion seems to be confirmed by blindsight patients’ incapacity to display spontaneous visually guided behavior in their impaired field, whereas they succeed to localize or recognize objects when forced (Dennett, 1991; Weiskrantz, 1997; Dehaene and Naccache, 2001).

Figure 4. Symbolic representation of the hierarchy of connections between competing brain processors, after Dehaene and Naccache (2001). Processors are mobilized into the workspace. As a counterpart, even if active, some others are kept out (repressed) of it.

Nevertheless, others works has emerged to support the thesis of unconscious autonomous intentions setting. One of the most convincing demonstrations (Perruchet, 1985, see Shanks, 2010, for challenges to this result) has involved dissociating learning from awareness. Subjects were presented tones that were, in half the cases, followed by an air puff directed at their eyes. In-between the two events, they were asked to rate their subjective expectation for the tone to be followed by the air puff. The analysis revealed subjects to be more likely to blink their eyes after reinforced trials associating the tone with the puff; however, their subjective expectation that air puff would occur tended to decrease. Thus, participants (consciously) expected a different outcome to occur compared to their unconscious intentions. Thus, the Perruchet effect argues in favor of implicit learning, allowing (at least basic) unconscious strategies to be set up.

However, certain questions arise in view of these findings. First, does the Freudian unconscious require the existence of the unconscious capacity to set goals, i.e., to set goals without consciousness being involved? Second, does the exogenous origin of stimuli, in Merikle’s experiments, modify Dehaene and Naccache’s conclusion? On the one hand, the conscious origin of goal-directed intention is not incompatible with the Freudian theory. Freud (1915) clearly claims that repressed contents have their original source in consciousness. Actually, the psychoanalytic paradigm is not incompatible with unconscious contents having been consciously perceived before becoming unconscious and automatic. On the other hand, such claim also does not forbid the hypothesis of unconscious intentionality. For instance, consider the somatic marker hypothesis by Damasio (1994). The Damasian hypothesis posits that the brainstem, hypothalamus, insular cortex and the right somatosensory cortex map to certain bodily states and cognitive processes. Somatic markers might play a preselecting role on strategies before being processed at a cognitive (rational) level. Thus, emotional mechanisms might process independently of conscious processes and interfere with the latter in prioritizing certain options (i.e., dumping or repressing3 them). The somatic markers evolve on the basis of past experiences that may have been conscious once. But the latter condition does not prohibit the somatic markers having, now, their “own intentions” (sometimes in contradiction with conscious ones), even if considered as automatics and non-conscious.

Moreover, synaptic transmission is modulated by experiences. Facilitated synapses, those that fire together, constitute the neuronal assemblies underpinning our memories (Buzsaki, 2004). The inscription of experience is not a picture of experiences. As a dynamical process, plasticity introduces discontinuity throughout the inscription of experience (Ansermet and Magistretti, 2007). Traces are associated with previous ones, combined with other sets of traces and desires and, finally, constitute a dynamic and autonomous inner life. So, if consciousness is a prerequisite for the setting of strategies that might, in the future, be processed unconsciously, we can hypothesize that synaptic plasticity must induce new and idiosyncratic associations, which suggest that they could be seen as unconsciously elaborated intentions that do not require consciousness to be perform and control. Such a claim gains in credibility when one considers theories of autopoesis. Kauffman (1995) has shown how artificial cells, in random Boolean network, reach homeostatic and more or less steady structures. In other words, novel strategies might self-organize without any top down or conscious control, as an “order for free” emerges from systems evolving at the edge of chaos. From this and similar complexity theories, we can produce an account that diminishes the need to postulate consciousness as the ever present prerequisite for decision-making-like mechanisms. But if we can challenge the postulate according to which unconscious intentions cannot be set up and perform out of consciousness control, conscious control is disputable too4.

The question of unconscious intentions is intimately linked to the sense that consciousness is ultimately a matter of control. Accordingly, criticisms of the “old concepts” of psychology are coordinated with the project of showing how the “feeling” of control is a “user illusion,” disguising the actual relation of the consciousness and the unconscious. Thus, according to Bargh (2005), for example, conscious control is an illusion resting on the subjective experience of “making a choice or forming an intention, and then enacting the decision or behavior, and tak[ing] this as incontrovertible evidence that the intention caused the outcome.” The renewed interest in the nature of unconscious activity has been driven by the growing suspicion about the actual scope of consciousness in the behavior of human beings (Wegner, 2003).

Libet (2004), in a series of famous experiments, showed that electrical potential precedes intentional movement by a minimum of 550 and 250 ms before subject’s awareness of its will to act. As well, the evidence for dissociating consciousness from learning and initiating actions logically leads to the premise that willful actions have no direct causative power. For example, in a study by Wegner and Wheatley (1999) test subjects, grouped in couples (one of whom was a confederate of the experimenters) were asked to point, with a cursor, at pictures referring to objects. Instructions were given over headphones so as to manipulate the subjects into believing that they were moving the cursor, whereas the confederates were doing it. When congruent words–pictures were presented about 1–5 s before the action, subjects reported having intentionally moved the cursor. The feeling dissipated when the words were presented 30 s before or 1 s after the action occurred. From the fallibility of conscious attribution, the authors concluded that the real mechanisms initiating behaviors might actually never be present in consciousness. As the authors put it “… if conscious will is an experience that arises from the interpretation of cues to cognitive causality, then apparent mental causation is generated by an interpretative process that is fundamentally separate from the mechanistic process of real mental causation” (Wegner and Wheatley, 1999).

From his work on split-brain patients, Gazzaniga (1985) hypothesized the existence of a cerebral system that retrospectively constructed such interpretations from behavior outcomes. In this context, it is noteworthy that we have abundant evidences that interpretations are often constituted at the expense of facts. Numerous reports show that subjects who are ignorant of the real causes of action will often invent false but consistent stories. Split-brain patients and subjects who were cued, in their neglected side, to perform certain actions will, when asked, fabulate explanations to rationalize their behaviors. Gazzaniga supposes this “interpreter” to be generally localized in the left hemisphere. In the same line Nisbett and Wilson (1977) have shown that introspective reports are generally stylized so as to be consistent with cultural and personal theories; moreover, self-analysis of choices impaired the quality of decisions that usually occur automatically (Wilson et al., 1993). From this body of evidences, it is logical to suppose that conscious reports might be simply the retroactive constructions of a narrative self (see Gallagher, 2000 for a review) or an autobiographical self (Damasio, 1999), which functions to enable the sense of a continuous self. In this way, the “illusion” of control has a biological and social function.

In the same line, brain anatomy seems to support the idea that conscious control is an illusion. Frith et al. (2000) argue that intended movements are represented in the prefrontal and premotor cortex, whereas representations guiding action are encoded in the parietal cortex. Moreover, studies have shown that working memory, usually considered as the prerequisite of conscious awareness, is not a unitary mechanism, but is rather a distributed function localized in different areas of the frontal and prefrontal cortex (Baddeley, 1986). According to Bargh (2005), “The storage of current intentions in brain locations that are anatomically separate from their associated and currently operating action programs would appear to be nothing less than the neural basis for non-conscious goal pursuit and other forms of unintended behavior.” In other words, action programs might function without and independently of conscious control. As a matter of fact, patients with unilateral or bilateral frontal lesions cannot inhibit grasping or using objects falling in their perceptual fields. This observation supports the claim that conscious intentions are not necessary for complex actions to be perfectly performed and guided (Lhermitte, 1983). Obviously the psychoanalytic field has to consider with a great interest such promising data even if, as we have seen, the endogenous setting of unconscious intentions is not a corner stone of psychoanalysis. Yet, by opening a room for unconsciously settled goals, neuropsychology makes even more obvious the reasons that led Freud to claim (against the academic psychology of its time) “the ego is not master in its own house” (Freud, 1917).

If subjects do not have access to the real causes underlying their intentions, the automatic/controlled (Posner and Snyder, 1975) dichotomy is threatened. So, the very question turns to determine the causative impact consciousness might have on unconscious processes. If consciousness is not necessary for the setting of novel strategies, it might trigger a momentary cognitive “reset” (Baars, 1988) allowing for new adaptive associations (Cleeremans, 2008). Instead of being taken as a controlling instance, it might be more relevantly conceived as a brief neurocognitive dynamic state catalyzing reorganization of unconscious associations through plasticity and reconsolidation (Alberini, 2005; Dudai, 2006; Arminjon et al., 2010). The latter hypothesis might provide to psychoanalytic insight and its curative effects a neurocognitive ground.

For several researchers involved in the psychoanalytic field, the Freudian unconscious is, for dynamic reasons, still dramatically irreducible to the cognitive unconscious. They point cognitive models in which any unconscious ideation can, in principle, reach consciousness. If in actuality they do not, the reason has to do simply with brain structure (on those questions, see Wilson, 2002). Moreover, according to the psychoanalytic field, cognitive unconscious processes are composed by perceptive, learning etc. mechanisms, far from the infantile primitive drives and desires Freud supposed as the basis of unconscious motivation. As a matter of fact, from the beginning of his psychoanalytical career, Freud put forward the idea of opposing forces as exerting an ontogenetic and organizing role for inner life. As seen above, equilibrium is supposed to result from the secondary process that involves the inhibition of the primary one. A second major dynamic and economic opposition, overlapping the latter, is tied with pleasure and unpleasure principles. In Freud’s words, what is displeasure for one system might represent pleasure for another (Freud, 1920). With the second topic theoretic shift, conflicts involve the disjunction between the Id as the “reservoir” of drives, the ego, and the super ego as the depositary of social norms. Conflicts are thus conceived between instances even as they operate within them, as in the case of ego cleavage. Last but not least, the pleasure/unpleasure principle led Freud to its most challenged concepts: opposition between death and life drives (1920). In this section we show that new models of brain function suggest that Freud’s dynamic was prescient. If the first wave of cognitive models seemed to show that the Freudian unconscious was partly misconstrued, the latest researches, under the paradigm of distributed cognitive functions, are much more in line with Freud’s theories.

As seen above, disputes about the existence of unconscious intentions have reflected a paradigm shift in cognitive neuroscience. Neuroscientists have criticized the attribution of complete control to the consciousness, as well as the classical opposition between automatic versus controlled processes, in the light of distributed and parallel models of brain functioning. As Freud supposed, cognitive processes are not linear, but could easily be regarded as using conflict as an organizing principle. As we have seen, the Posner’s model stemmed from the assumption that consciousness is serial and of a limited capacity. As Allport (1989) put it, writing about models previous to that of the one devised by Broadbent (1958), “information not selected was therefore excluded from semantic categorization identification, and selection, according to this interpretation, was synonymous with selective processing, that is, shutting out of non-selected information from further analysis.” Such arbitrary parameters (which exclude the notion of the active unconscious a priori) were challenged by Shaffer (1975)who demonstrated that attention was not always limited to one channel. For instance, if we can listen to a speech and copy-type at the same time, we can hardly read aloud a text and audio-type at the same time. Hence, if the brain can process different kinds of representations in parallel, the limitations of attention might not depend on limited representational capacities, neither on the rigid limitations of a central control capacity, but on specific interferences between different modalities.

Along the same lines is the work that has been done with negligent patients, who are unaware of objects on their left side, or distant objects, or isolated sensory modalities. Obviously, the great variety of their spatial attention disturbances pleads in favor of a distributed attentional system. Hence, in contrast with one channel attention models, Allport proposed that a multiplicity of specialized systems might underlie discrete attentional resources, which in turn would suppose numerous and distinct types of constraints corresponding to the system itself and its interrelation with other systems. According to Allport’s (1989) model: (1) The environment is partly unpredictable, (2) systems have to manage multiple and concurrent goals in order to adapt to the inner and outer world, (3) discrete systems have to coordinate all their subcomponents to impose their own “goals,” (4) attentional systems require selective priority assignments in order to coordinate the conflicting intentions in a consistent active or dynamical attentional set. As a consequence, the so-called limited capacity of consciousness might be seen as an indirect and unexpected result, a compromise emerging from competitive and distributed subsystems. In this model, lower subsystems or subsets of microfeatures will still operate even outside of the scope of conscious attention. As Shevrin et al. (1996) put it: “As a consequence, the notions of automatic and controlled lose their distinctness: control process, in the sense of being affected by motives, can go on outside of the focus of current attention (…). The picture one can draw from Allport’s model begins to approximate a psychoanalytic model in which internal and unconscious motives, that are related to basic needs or drives, shape cognitive processes both within and outside consciousness, once we link consciousness with the current attentional engagement.” So, the question is how or according to which organization principle, cognitive processes are really shaped by the multiplicity of basic needs?

Allport’s model lends support to the thesis of there being logically consistent unconscious goals or motives. As a correlate of the third postulate, it entails that subsystems not within the scope of awareness at some given time are not therefore shut off and are still at work, even if they do not represent a current priority. The Freudian theory, according to which unconscious processes are silently active and can interfere with conscious processes, appears as even more plausible once this picture of attention is given. Another consequence is that all the models that project the functioning of multiple systems while one is raised into consciousness elevate conflict and inhibition to central causes of auto-organization. Allport’s model, like Freud’s, takes attention to be at the frontier of inner and outer world. The monitoring of both worlds involves the competition of each subsystem inter alia for attention space. In this context, the theoretical foundations of current neuroscience models are in line with the Freudian claims about psychic conflicts, especially with such concepts as that of compromise formations, repression etc.

For instance, Driver and Vuilleumier (2001) have shown how neglect behavior following brain lesions is not the result of primary cortex impairment. Rather, neglect appears as an example of conscious attention functioning in normal subjects as a means to modulate brain activity. We generally perceive the stimuli that are filtered in order to fill our attempts. Single-neuron recordings show that, for a same stimulus, neuronal activity varies as a function of the attentional state of the observer (Parasuraman, 1998). Neglect patients are able to detect, in their neglected left side, a stimulus in isolation, whereas they fail to consciously perceive it if another stimulus is presented at the same time. Inversely, stimuli linked together (gestalt) are more likely to be perceived than isolated ones. As an explanation, lesions in neglect patients’ parietal cortex might induce a bias in the competition of brain areas. According to Driver and Vuilleumier (2001), the “winner-takes-all” principle by Desimone and Duncan (1995), might be applicable here, according to which “multiple concurrent stimuli always compete to drive neurons and dominate the network (and thus ultimately to dominate awareness and behavior).”

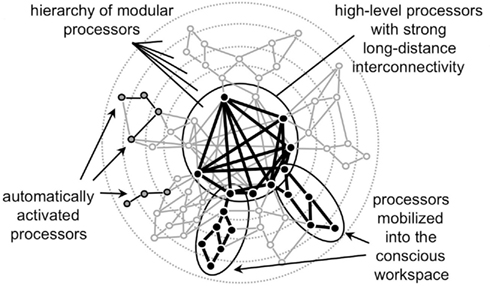

Even if its adherents may challenge the Freudian implications of this position, the neuronal model of a global workspace can easily be seen as one of the best examples of the rebirth of psychodynamic(Baars, 1988). Deriving its claims from the hypothesis that the brain is composed of low-level subspecial functions, the hypothesis of attention conflicts posits consciousness to emerge (bottom up) when many subcomponents exchange information and synchronize their activities forming a group or a “neuronal global workspace.” According Posner and Dehaene (1994): “top-down attentional amplification is the mechanism by which modular processes can be temporarily mobilized and made available to the global workspace, and therefore to consciousness.” One can figure out how spontaneous generation of stochastic activity might induce the synchronization of groups of neurons in order to respond to contextual inner and outer needs. Neuron of one assembly might “win” the struggle for priority against subspecial neurons of another. Multiple biological needs (drives), mapped at a cortical level, might enter in competition to impose the priority of their satisfaction.

This picture of a dynamic hierarchy also allows establishing a typology of the different unconscious processes coordinated with their conscious accessibility. Naccache (2006) has hypothesized three categories of unconscious. The first is that of a structural unconscious which is incapable of surfacing to the consciousness. Such a structural unconscious must rest on the functional architecture of the brain, i.e., the synaptic ponderation. For instance, Zajonc (1968) demonstrated that repeated exposure to stimuli orients unconscious preference toward it. Structural unconscious, similarly, might refer to the procedural processes performed without awareness, as in using language or playing an instrument, without there being a dimension that enters into conscious articulation. In echo with the Freudian approach, we can add to the structural unconscious all the somatic representations of the internal milieu that never became conscious. A second category5 of unconscious systems subsumes unconscious representations connected to the global workspace, but not currently top-down amplified, as is in the case of the rich representational unconscious processes we cited in the first part of this paper. For instance, subliminal stimuli are perceived unconsciously and need time to be mobilized in the workspace through a “self-sustained long-distance loop.” Finally, another category of unconscious processes consists of those that could become conscious but that did not, for a reason or another, for instance, the words in the study by Sperling in section 1 (only few words become conscious but it could have been any of them). How are we to distinguish the second and third categories? All unconscious contents of the third category contain the capacity to be articulated in the consciousness. Those contents can or could have been conscious. Freud named those representations that remain outside of the sweep of the consciousness for contingent reasons, preconscious contents.

What about repressed unconscious? Before Freud introduced the second topic, he qualified as unconscious only repressed representations. He distinguished (1915) two kinds of repression, one operating consciously and the second unconsciously6. Anderson and Green (2001) have shown how repression initiated consciously can be empirically presented. So, the remaining but important psychoanalytical question is whether repression can be initiated unconsciously. Despite the lack of empirical studies, one could propose suppression to be automated as part of a suppressing neural route (Wilson and Dunn, 2004, for a review). As seen in part three, it does not make a difference if repression has been unconsciously set up, or is based on some initial conscious processes progressively made automatic. Nevertheless, the workspace model yields a somewhat relevant framework for the Freudian preconscious–unconscious distinction. In order to preserve the specificity of the second category of the unconscious, Dehaene and Naccache (2001) focused on the defining role of dynamic constraints, which involve those contents that have been bracketed from the consciousness on account of the fact that they have not been top-down amplified. This claims sound all the more Freudian if we keep in mind that in the global workspace model, microfeatures (for us drives) have to struggle to impose their output (Figure 4). Conversely, to be top-down amplified, they have to fit the workspace values. To become a dominant coalition, microfeatures have to engage a bottom up struggle to impose themselves7.

Both processes might overlap the two kinds of repressing mechanisms. One can easily construct scenarios in which top-down attentional amplification functions to “avoid” certain representations for explicit reasons. Others might not be admitted in the global workspace, even if trying to8. Many reason for their repression might be raised, especially affective ones. Here we can think of the Damasian somatic markers hypothesis. As we seen in part 3, “Third Postulate: Unconscious Intentions or Goal-directed Unconscious Processes”, some strategies are preselected before reaching rational deliberations. In a way, they are automatically avoided (unconsciously repressed) because they activate a negative somatic state. In such cases, these “repressed” contents might remain unconscious, not for anatomical or structural reasons as in Naccache’s first category, but rather for dynamic ones. As seen in part two, the medial prefrontal cortex blockade of memories is hypothesized to play such role. Thus, despite Naccache’s conclusions (Naccache, 2006), the Freudian model is consistent with conflicting models, including the workspace model, which is theoretically a good match for Freud’s first topic tripartition, with one exception.

New pictures of the different kinds of unconscious converge to distinguish procedural memory from the repressed unconscious contents. It is noteworthy that current research insists on the structural role of infantile experiences. Neurobiological and inter-personal perspectives posit interactions between newborns and care givers (self-objects) to be necessary for babies to regulate their inner conflicts. The compromise formation of solutions to homeostatic imbalances entailed by the activation of drives and their affective aftermaths may be structured during infancy and last for the entire life span. Shore (2009) – (for a critical account see Kaplan-Solms and Solms, 2000) has proposed the right hemisphere to underpin attachment as a primitive and mostly unconscious system: the right hemisphere is tightly connected to the limbic system; the right dorsomedial prefrontal cortex is supposed to process self-referential stimuli and to be activated in recollection of personally affect-laden life events (Reiman et al., 1997). Moreover, the right hemisphere has tentatively been identified as the location of empathic mirroring, fleshing out the hypothesis according to which attachment result from a “right hemisphere to right hemisphere communication.” Hence, infant experiences might have a deep impact on brain structures underpinning the unconscious processes regulating desires and motives, more than determining specific representational contents per se (Mancia, 2006). In other words, the unconscious do not process infantile representations, but is significantly dynamically structured by infantile experiences. Such a statement is consistent with the model by Bucci (1997) that emphasizes the early presymbolic and plurimodal symbolic encoding of affective and sensory experiences. In the same line, Mancia proposed these experiences to shape newborns’ procedural memory and form an implicit “unrepressed memory” distinct from the repressed one, that needs the maturation of explicit memory and symbolic abilities. Stemmed on the existence of two separate, but connected, neuronal systems underpinning the two kinds of memory – respectively Amygdala for implicit memory, hippocampus and frontal cortex for explicit one – the model posits that the unrepressed unconscious determinates the way defense mechanisms interfere with explicit contents retrieval. In this way, infantile experiences might shape the modes of compromise solutions one constitutes to solve inner conflicts.

We have started from the seminal paper of Shevrin and Dickman (1980) according to whom the existence of unconscious complex psychological processes is hardly doubted by mainstream cognitive science. We have shown that the unconscious–conscious dichotomy is not accounted for by the primitive/complex and dumb/smart ones devised by one evolutionary theory of the brain. Instead, we have tried to show that unconscious processes have to be taken as a complex cognitive style per se, rather than as a weaker form of cognition. If we accept the independence and complexity of unconscious processes, we must consider whether the evidences show that the unconscious could be goal directed. As we have shown, the positive answer to this question challenges the traditional partition of the mind into unconscious–automated and conscious-controlled processes. The interest among neuroscientists in the conscious control illusions seems to lead to the same conclusion. Accordingly, in a more speculative way, we have shown the consequences for abandoning the automatic–controlled paradigm in favor of the distributed and competitive conception of cerebral functions. It is with this picture of the dynamical organization of brain processes that we find a scientifically informed framework for the relevant conjunction of the neuroscientific discoveries and the Freudian hypotheses.

Actually, psychoanalysts might argue this view to be too narrow and adding some further postulates and dimensions. Yet, we just have tried to fill in the implications of Shevrin and Dickman’s basic listing of the Freudian unconscious specificities and hope more evidences to be uncovered for the list to be clarified and completed. In the waiting, it no longer seems unrealistic to posit Freud’s hypotheses on unconscious as something psychological, displaying its specific rules, having its own goals to satisfy and being at least partly composed of repressed contents. In return, the psychoanalytical field has to take into account that current works exceed the characteristics that Freud was attributing to the unconscious processes. This means that the unconscious has not to be restricted to infantile contents, drives or repressing mechanisms. Paradoxically, in showing how almost all cognitive functions may be processed unconsciously, current researches appear as more Freudian than Freud was himself. But more importantly, these new mechanisms can lead to new explanations for clinical phenomena and call for a refinement of metapsychological categories. Lastly, we can learn from the present essay that if cognition is mostly performed unconsciously, the both fields have to improve their definition of conscious processes. If consciousness does not exert a direct control on behavior, we have to establish which role the serial and narrative productions of the conscious subject plays. Because of its specific clinical standpoint, psychoanalysis can surely yield relevant outlooks on this topic.

This review calls for a last remark on the so-called opposition between the cognitive and Freudian unconscious. In contradiction with the somewhat jocular implication of Edelman’s anecdote, we have tried to show that there is no reason in operating a clear-cut distinction between the two kinds of unconscious. So far, they share an interest for the same cognitive processes and, in definitive, for the same brain9. The latter conclusion is grounded in empirical data, not in the Edelman’s or Monod’s subjective convictions that Freud was totally right or wrong. Such a position is relevant for psychoanalysis if it wants to put its hypotheses in line with current scientific works. Yet, this does not mean that psychoanalysis has to be dissolved or reduced into “more fundamental” approaches. On the contrary, the Freudian unconscious is a compound of heuristic hypotheses on cognition that allows emphasizing specific phenomena in the specific context of the cure. Thus, one can ask whether the opposition between cognitive and Freudian unconscious rests on a misunderstanding. Actually, cognitive approaches are characterized by a specific methodology, calling for empirical facts, and not by imposing themselves ideological claims about the unconscious per se. So, neurocognitive science cannot raise an in principled objection to psychoanalysis’s theses. What about the reciprocal claim?

If psychoanalysis extends itself to include a robust sense of neuroscientifically informed experimentations as an alternative source of hypothesis and confirmation – in addition to, and not in opposition with clinic – the gap between the cognitive and Freudian unconscious would vanish. As the dynamic studies tensions between physic forces, without contravening to the law of physics, Freudian metapsychology might name a dynamic perspective on cognitive tensions. As such, it does not contravene current neurobiological knowledge, at least in the strict limits of the four postulates examined here.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This research was supported by the Agalma Foundation.

Alberini, C. M. (2005). Mechanisms of memory stabilization: are consolidation and reconsolidation similar or distinct processes? Trends Neurosci. 28, 51–56.

Allport, A. (1989). “Visual attention,” in Foundations of Cognitive Science, ed. M. I. Posner (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 631–682.

Anderson, M. C., and Green, C. (2001). Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control. Nature 410, 366–369.

Ansermet, F., and Magistretti, P. J. (2007). Biology of Freedom: Neural Plasticity, Experience and the Unconscious. New York: Other Press.

Arminjon, M. (2010). Les intentions du corps, Psychanalyse, biologie et sciences de l’esprit. Montréal: Editions Liber, Collection “Voix Psychanalytiques”.

Arminjon, M., Ansermet, F., and Magistretti, P. J. (2010). The homeostatic psyche: Freudian theory and somatic markers. J. Physiol. 104, 272–278.

Baars, B. J. (1988). “Momentary forgetting as a “resetting” of a conscious global workspace due to competition between incompatible contexts,” in Psychodynamics and Cognition, ed. M. J. Horowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 269–293.

Bargh, J. A. (2005). “Bypassing the will: toward demystifying the nonconscious control of social behavior,” in The New Unconscious, eds R. Hassin, J. Uleman, and J. Bargh (New York: Oxford), 37–58.

Brakel, L. A. W. (2004). The psychoanalytic assumption of the primary process: extra psychoanalytic evidence. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 52, 1131–1161.

Brakel, L. A. W., Shevrin, H., and Villa, K. (2002). The priority of primary process categorizing: experimental evidence supporting a psychoanalytic developmental hypothesis. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 50, 483–505.

Bucci, W. (1997). Psychoanalysis and Cognitive Science: A Multiple Code Theory. New York: Guilford Press.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., and Friston, K. J. (2010). The default-mode, ego-functions and free-energy: a neurobiological account of Freudian ideas. Brain 133, 1265–1283.

Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ Error, Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: A. Grosset/Putnam Book.

Damasio, A. (1999). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Dehaene, S., and Naccache, L. (2001). Towards a cognitive neuroscience of consciousness: basic evidence and a workspace framework. Cognition 79, 1–37.

Desimone, R., and Duncan, J. (1995). Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 193–222.

Draine, S. C. (1997). Analytic Limitations of Unconscious Language Processing. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Driver, J., and Vuilleumier, P. (2001). Perceptual awareness and its loss in unilateral neglect and extinction. Cognition 79, 39–88.

Dudai, Y. (2006). Reconsolidation: the advantage of being refocused. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 174–178.

Evans, J. S. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment and social cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59, 255–278.

Freud, A. (1936). The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense. New York: International Universities Press.

Freud, S. (1915a). “Instincts and their vicissitudes,” in Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 14, ed. J. Strachey (London: Hogarth Press), 111–140.

Freud, S. (1915b). “Beyond the pleasure principle,” in Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 18, ed. J. Strachey (London: Hogarth Press), 111–140.

Freud, S. (1915c). “The unconscious,” in Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 14, ed. J. Strachey (London: Hogarth Press), 166–215.

Freud, S. (1917). “A difficulty in the path of psycho-analysis,” in Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 17, ed. J. Strachey (London: Hogarth Press), 135–144.

Freud, S. (1920). “Beyond the pleasure principle”, in Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 18 (London: Hogarth Press), 1–64.

Friston, K., Kilner, J., and Harrison, L. (2006). A free energy principle for the brain. J. Physiol. Paris 100, 70–87.

Frith, C. D., Blakemore, S. J., and Wolpert, D. M. (2000). Abnormalities in the awareness andcontrol of action. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355, 1771–1788.

Gallagher, S. (2000). Philosophical conceptions of the self: implications for cognitive science. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 14–21.

Gazzaniga, M. S. (1985). The Social Brain: Discovering the Networks of the Mind. New York: Basic Books.

Goodale, M. A., and Milner, A. D. (1992). Separate visual pathways for perception and action. Trends Neurosci. 15, 20–25.

Greenwald, A. G., and Liu, T. J. (1985). Limited unconscious processing of meaning. Paper Presented at Meetings of the Psychonomic Society, Boston.

Hardaway, R. A. (1990). Subliminally activated symbiotic fantasies: facts and artifacts. Psychol. Bull. 107, 177–195.

Kaplan-Solms, K., and Solms, M. (2000). Clinical Studies in Neuro-Psychoanalysis: Introduction to a Depth Neuropsychology. London: Karnac Books.

Kauffman, S. (1995). At Home in the Universe: The Search for Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lhermitte, F. (1983). “Utilization behavior” and its relation to lesions of the frontal lobe. Brain 106, 237–255.

Libet, B. (2004). Mind Time: The Temporal Factor in Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Loftus, E. F., and Klinger, M. R. (1992). Is the unconscious smart of dumb? Am. Psychol. 47, 761–765.

Mancia, M. (2006). Implicit memory and early unrepressed unconscious: their role in the therapeutic process (how the neurosciences can contribute to psychoanalysis). Int. J. Psychoanal. 87, 83–103.

Marshall, J. C., and Halligan, P. W. (1988). Blindsight and insight in visuo-spatial neglect. Nature 336, 766–767.

Medin, D., Goldstone, R., and Gentner, D. (1990). Similarity involving attributes and relations: judgments of similarity and differences are not inverses. Psychol. Sci. 1, 64–69.

Merikle, P. M., Joordens, S., and Stolz, J. A. (1995). Measuring the relative magnitude of unconscious influences. Conscious. Cogn. 4, 422–439.

Murphy, S. T., and Zajonc, R. B. (1993). Affect, cognition, and awareness: affective priming with optimal and suboptimal stimulus exposures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 64, 723–739.

Naccache, L. (2006). Le nouvel inconscient: Freud, Christophe Colomb des neurosciences. Paris: O. Jacob.

Nisbett, R. E., and Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports onmental processes. Psychol. Rev. 8, 231–259.

Parasuraman, I. (1998). “The attentive brain: Issues and prospects”, in The Attentive Brain, ed. R. Parasuraman (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 401–423.

Perruchet, P. (1985). A pitfall for the expectancy theory of eyeblink conditioning. Pavlov. J. Biol. Sci. 20, 163–170.

Posner, M. I., Klein, R. M., Summers, J., and Buggie, S. (1973). On the selection of signals. Mem. Cognit. 1, 2–12.

Posner, M. I., and Snyder, C. R. R. (1975). “Attention and cognitive control”, in Information Processing and Cognition: The Loyola Symposium, ed. R. Solso (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 669–682.

Raichle, M. E., and Snyder, A. Z. (2007). A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage 37, 1083–1090; discussion 1097–1099.

Reiman, E. M., Lane, R. D., Ahern, G. L., Schwartz, G. E., Davidson, R. J., Friston, K. J., Yun, L. S., and Chen, K. (1997). Neuroanatomical correlates of externally and internally generated human emotion. Am. J. Psychiatry 154, 918–925.

Schneider, W., and Shiffrin, R. M. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: 1. Detection, search, and attention. Psychol. Rev. 84, 1–66.

Shaffer, L. H. (1975). “Multiple attention in continuous verbal tasks,” in Attention and Performance V, eds P. M. A. Rabbit, and S. Dornic (New York: Academic Press), 157–167.

Shevrin, H., Bond, J. A., Brakel, L. A. W., Hertel, R. K., and Williams, W. J. (1996). Conscious and Unconscious Processes: Psychodynamic, Cognitive, and Neurophysiological Convergences. New York: Guilford Press.

Shevrin, H., and Dickman, S. (1980). The psychological unconscious: a necessary assumption for all psychological theory? Am. Psychol. 35, 421–434.

Shin, L. M., Rauch, S. L., and Pitman, R. K. (2006). Amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and hippocampal function in PTSD. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1071, 67–79.

Shore, A. N. (2009). Relational trauma and the developing right brain an interface of psychoanalytic self psychology and neuroscience. Self and systems. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1159, 189–203.

Silverman, L., and Weinberger, J. (1985). Mommy and I are one: implications for psychotherapy. Am. Psychol. 40, 1296–1308.

Sperling, G. (1960). The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 74, 1–30.

Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 18, 643–662.

Ungerleider, L. G., and Mishkin, M. (1982). “Two cortical visual systems,” in Analysis of Visual Behavior, eds D. J. Ingle, M. A. Goodale, and R. J. W. Mansfield (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 549–586.

Wegner, D. M. (2003). The mind’s best trick: how we experience conscious will. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7, 65–69.

Wegner, D. M., and Wheatley, T. (1999). Apparent mental causation: sources of the experience of will. Am. Psychol. 54, 480–492.

Weinberger, J., and Hardaway, R. (1990). Separating science from myth in subliminal psychodynamic activation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 10, 727–756.

Weiskrantz, L. (1997). Consciousness Lost and Found: A Neuropsychological Exploration. New York: Oxford University Press.

Whalen, P. J., Rauch, S. L., Etcoff, N. L., McInerney, S. C., Lee, M. B., and Jenike, M. A. (1998). Masked representations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J. Neurosci. 18, 411–418.

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., Thermenos, H. W., Milanovic, S., Tsuang, M. T., Faraone, S. V., McCarley, R. W., Shenton, M. E., Green, A. I., Nieto-Castanon, A., LaViolette, P., Wojcik, J., Gabrieli, J. D., and Seidman, L. J. (2009). Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of sons with schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1279–1284.

Wilson, T. D. (2002). Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, T. D., and Dunn, E. (2004). Self-knowledge: its limits, value, and potential for improvement. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 493–518.

Wilson, T. D., Lisle, D. J., Schooler, J. W., Hodges, S. D., Klaaren, K. J., and LaFleur, S. J. (1993). Introspecting about reasons can reduce post-choice satisfaction. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 19, 331–39.

Keywords: Freud, psychoanalysis, neuroscience, cognitive styles, intentions, conflict, cognition

Citation: Arminjon M (2011) The four postulates of Freudian unconscious neurocognitive convergences. Front. Psychology 2:125. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00125

Received: 29 March 2011; Paper pending published: 29 April 2011;

Accepted: 30 May 2011; Published online: 20 June 2011.

Edited by:

Perrine Marie Ruby, Insitut National de Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, FranceReviewed by: