Context and repetition in word learning

- School of Psychology, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK

Although shared storybook reading is a common activity believed to improve the language skills of preschool children, how children learn new vocabulary from such experiences has been largely neglected in the literature. The current study systematically explores the effects of repeatedly reading the same storybooks on both young children’s fast and slow mapping abilities. Specially created storybooks were read to 3-year-old children three times during the course of 1 week. Each of the nine storybooks contained two novel name–object pairs. At each session, children either heard three different stories with the same two novel name–object pairs or the same story three times. Importantly, all children heard each novel name the same number of times. Both immediate recall and retention were tested with a four-alternative forced-choice task with pictures of the novel objects. Children who heard the same stories repeatedly were very accurate on both the immediate recall and retention tasks. In contrast, children who heard different stories were only accurate on immediate recall during the last two sessions and failed to learn any of the new words. Overall, then, we found a dramatic increase in children’s ability to both recall and retain novel name–object associations encountered during shared storybook reading when they heard the same stories multiple times in succession. Results are discussed in terms of contextual cueing effects observed in other cognitive domains.

Introduction

Reading storybooks to preschool children is an ubiquitous activity in many western homes (Simcock and DeLoache, 2006). Numerous studies have documented that shared storybook reading promotes later academic performance (Lonigan and Whitehurst, 1998), reading fluency (Ardoin et al., 2008), and print knowledge (Lonigan et al., 2008). Most studies exploring shared storybook reading focus on pragmatic factors, such as parent–child social interaction (e.g., Bus, 2001; Fletcher and Reese, 2005), adult reading style (e.g., Sénéchal et al., 1995a; Blake et al., 2006), asking open-ended questions during reading (e.g., Whitehurst et al., 1988; Valdez-Menchaca and Whitehurst, 1992) and providing explanations of target words (e.g., Penno et al., 2002). Recently, several studies have explored how the types of illustrations used influences how well children can generalize after having been read a picture book (e.g., Ganea et al., 2009; Tare et al., 2010). Such studies demonstrate that children learn more from picture books with realistic photographs or color drawings than simple line drawings (Simcock and DeLoache, 2006, 2008). Overall, however, few empirical studies have explored how being read to influences young children’s ability to learn new words from storybooks. This is particularly surprising given how common this activity is in preschool children’s everyday experiences (Lonigan et al., 2008).

The studies on children’s ability to learn words via storybooks have predominately focused on school-aged children and have attempted to teach children many words simultaneously – with modest results (see, Biemiller and Boote, 2006 for a review). For example, Brett et al. (1996) attempted to teach fourth grade students 20 target words over the course of 1 week. Children were only able to learn approximately three words, even when teachers defined the words as they read. Similarly, Elley (1989) attempted to teach 7-year-old children 20 target words over the course of 1 week. Again, children were only able to learn on average 3.44 of the target words. In a study with younger children, Sénéchal and Cornell (1993) used a story to introduce 10 target words. Both 4- and 5-year-old children demonstrated learning of approximately three to four words (both when tested immediately and after a 1-week delay).

In addition to attempting to teach many words simultaneously, the extant literature on word learning via storybooks often lacks rigorous experimental control regarding children’s experiences during the study, stimulus presentation and the target words themselves. First, children in control groups often receive less shared reading exposure than their peers in experimental groups. In some cases, children in control groups do not receive any exposure to the storybooks during the study (see, Lonigan et al., 2008, for a review). Second, many studies use commercially available storybooks as stimuli (e.g., Sénéchal et al., 1995b; Brett et al., 1996; Penno et al., 2002). Several authors have noted problems with using such books, including target words not occurring equally often across books (Robbins and Ehri, 1994), books being different lengths (Sénéchal et al., 1995a), children having difficulty relating to the plots (Elley, 1989), and different books not being equally memorable (Cornell et al., 1988). Finally, several studies use target words that are synonyms for words children already know, such as infant instead of baby or snapshot instead of picture (Sénéchal and Cornell, 1993; Sénéchal, 1997). Sénéchal and Cornell (1993) have argued that using of synonyms of known words changes the word learning task to one in which children are merely learning a new word for a known concept. When investigating the underlying cognitive mechanisms supporting children’s word learning, the use of novel words is especially important because it is otherwise uncertain whether one is testing knowledge acquired over the course of the experiment or a priori knowledge (for a similar argument see, Bornstein and Mash, 2010). Given these methodological issues, it is unclear how reading storybooks to preschool children may facilitate word learning and which cognitive and developmental mechanisms may support this process. Clearly, a controlled investigation of children’s word learning via storybooks with novel words is needed (for a similar commission see, Sénéchal, 1997). The goal of the current study is to explore whether preschool children can learn words via storybooks and the mechanisms that may support word learning in the shared storybook reading context.

Word learning is a complicated process that includes both forming an initial, rough hypothesis of the new word’s meaning (fast mapping, Carey, 1978) and gradually incorporating that new word into memory (slow mapping, Carey, 1978; Capone and McGregor, 2005; Swingley, 2010). For example, imagine a child looking at a page of a storybook when she hears the novel word zorch. To form an initial hypothesis of what the word zorch means, the child must segment the word from the speech stream and determine its referent in the current picture, which may also depict several other possible referents (Sénéchal et al., 1995b; Sénéchal, 1997; Horst and Samuelson, 2008). For example, the picture may show a girl holding a novel object in front of a piano. If the child knows the words girl and piano, then the child can determine that zorch must refer to the novel object via mutual exclusivity (Markman, 1990) or process-of-elimination (aka disjunctive syllogism, Halberda, 2006). However, forming this initial hypothesis does not mean that the child has really learned the word (Riches et al., 2005; Horst and Samuelson, 2008). Indeed, processing demands might prevent young children from learning the correct name–object association after only a single exposure (Mather and Plunkett, 2009).

To fully learn the new word the child must encode the novel word form (e.g., the individual phonemes in sequence), encode something about the referent (e.g., its shape, its color) and store this information into memory in such a way that the information is linked and can be retrieved at a later point in time (Sénéchal et al., 1995b; Bloom, 2000; Horst and Samuelson, 2008), including if the child encounters a new exemplar from the novel category or the word in a new context (Schafer, 2005). That is, slow mapping involves forming a robust memory representation of the name–object association, such that it can withstand a delay. This memory representation emerges gradually during the extended slow mapping phase (Carey, 1978). During slow mapping, repeated encounters allow the child to strengthen the name–object association (see also, Simcock and DeLoache, 2008; Smith and Yu, 2008). Specifically, the statistical regularity with which a novel name and its referent co-occur helps strengthen these representations (Horst et al., 2006). For example, the zorch name–object association will be strengthened throughout the shared storybook reading episode as the child hears the word zorch and sees the novel object in each new context, such as in different pictures on subsequent pages (for a similar argument, see Rohlfing et al., 2003). Note, on this view, known and novel names are on a continuum of familiarity. That is, each known name starts out as a novel name and each novel name has the potential to become a known name with repeated encounters (for a similar argument see, Horst et al., 2006; McMurray et al., 2009).

Sénéchal and Cornell (1993) have argued that shared book reading may facilitate word learning because of its repetitive nature. Specifically, multiple readings provide children with additional opportunities to encode, associate and store information about new words or information, resulting in stronger memory representations (see also, Sénéchal et al., 1995b; Simcock and DeLoache, 2008). Further, hearing the same stories repeatedly likely helps preschool children to predict what will happen next (Ardoin et al., 2008). Children clearly learn from hearing the same story repeatedly, as is demonstrated by their ability to correct parents if they deviate from the text (Sulzby, 1985). It is possible, then, that repeatedly reading the same stories not only serves to entertain young children, but also to teach them new words.

Robbins and Ehri (1994) read kindergarteners the same story twice 2–4 days apart and tested their recall of 11 target words following the second reading. Target words were unfamiliar words substituted for known words in the story (e.g., chortle was substituted for laugh). Target words comprised multiple word types (i.e., one noun, two adjectives, eight verbs), four of which were illustrated in the story. Eight target words occurred twice in the story, three occurred once. Overall, children learned 1.24 target words (16%). The authors failed to find a correlation between number of occurrences and learning probability. Also, because every child heard the story twice, the effect of repeated reading remains unknown. In contrast, Sénéchal (1997) read a story to three groups of 3- to 4-year-old children before testing their recall of 10 target words. One group was read a story once and two groups were read the same story three times over 2 days (with and without the reader asking children questions during the reading). Like Robbins and Ehri (1994), the 10 target words were synonyms for known words (two verbs, eight nouns). Each target word occurred once in the story. Overall, children who heard the story three times learned approximately 5.10 target words (50%) and children who heard the story once learned 3.2 words (30%). These studies demonstrate that repeated readings facilitate learning via storybooks. However, because these studies have only tested recall, the effect of repeatedly reading the same stories on children’s ability to retain new words remains unknown.

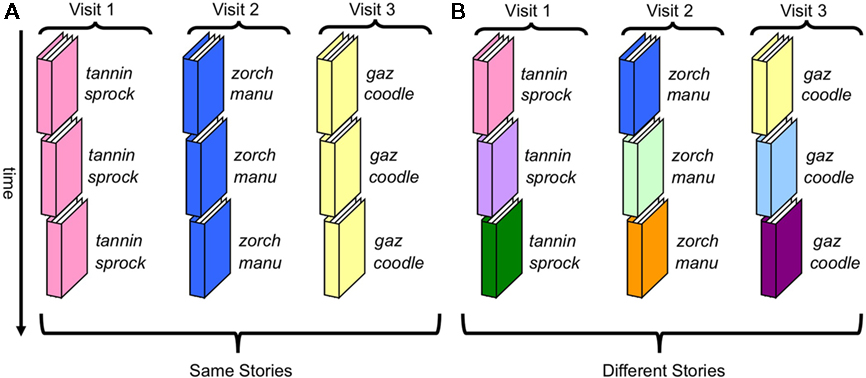

Thus, in the current study we explored how repeatedly reading the same storybooks facilitates young children’s ability to both recall and retain novel words. Taking the advice from previous research, we only presented novel words (Sénéchal and Cornell, 1993; Sénéchal, 1997; Bornstein and Mash, 2010), we only used nouns (Robbins and Ehri, 1994), we presented target words multiple times in each story (Robbins and Ehri, 1994) and we read stories with characters with whom children could identify (Elley, 1989). Specifically, we created nine storybooks to teach children six novel name–object pairs over the course of 1 week. Importantly, all children heard the same number of novel names the same number of times over the course of the study. However, one group of children encountered these novel words by being read the same stories repeatedly on the same day while another group of children encountered these words by being read different stories. To test children’s fast mapping from storybooks, at the end of each visit we tested children’s immediate recall for the name–object pairs encountered during that visit. To test children’s slow mapping from storybooks, at the end of the study we tested children’s retention for the name–object pairs encountered during the first two visits.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Sixteen 3-year-old monolingual, British English speaking children participated. Children were from primarily white, middle-class backgrounds, and lived in an urban area on the English Channel. Families were recruited from a lab database of parents interested in participating in child language research. Parents were contacted by email and telephone. Ethical approval was granted by the Schools of Psychology and Life Sciences Ethics Committee and adhered to the guidelines set out by the British Psychological Society. Informed consent was obtained from each child’s parent and each child assented to participating.

Children were randomly assigned to either the same stories condition (n = 8, 4 girls, Mage = 43 months, 10 days, SD = 3 months, 9 days, range = 39 months, 12 days to 46 months, 17 days) or to the different stories condition (n = 8, 5 girls, Mage = 43 months, 18 days, SD = 2 months, 15 days, range = 39 months, 28 days to 48 months, 17 days). There was no difference between groups in age, t(14) = 0.18, ns, d = 0.09. Children were visited in their homes three times within 1 week, with approximately 3 days between visits (M = 2.50 days, SD = 0.89 days, range = 1.00–3.5 days). There were no differences between groups in SES, t(14) = 0.82, ns, d = 0.42, all children came from middle-class families. There was also no difference between groups in maternal education: all of the mothers had completed A-levels (cf. completed high school). One mother in each condition had completed a Higher National Diploma (cf. associates degree). In the same stories condition, four mothers had a bachelor’s degree and one mother had a master’s degree. In the different stories condition, five mothers had a bachelor’s degree and one mother had a Ph.D. Each child received a small gift after each of the first two visits (e.g., a sparkly pencil) and a larger gift (e.g., stuffed animal) after the final visit.

Stimuli

Storybooks

Nine storybooks were created for this study. Throughout each story, two novel objects were each named four times but were not the focus of the plot. Three triads of storybooks were created. The Very Naughty Puppy, Nosy Rosie at the Restaurant, and Rosie’s Bad Baking Day each depicted the same two novel objects that were used like kitchen tools: an inverted sling shot that was used like a hand mixer (sprock) and a kinetic wheel that was used like a rolling pin (tannin). Mischief at the Toyshop, I Don’t Want to Share! and The Mystery Auntie each depicted the same two novel objects that were used like inside toys: a striped cup-and-ball game (zorch) and a giant, blue pen with orange, rubber strings on the end (manu). Finally, New Friend at the Park, Trouble at the Library, and The Surprisingly Good Bad Day each depicted the same two novel objects that were used like outside toys: a plastic ball catcher (coodle) and a black-and-white orb that changed color when bounced (gaz). It was important to include more than one novel name–object pair in each story to ensure that when answering recall questions children were not simply choosing the only item that had been previously named (see also, Schafer and Plunkett, 1998).

Storybook plots surrounded the everyday activities of one family with either the brother (Josh) or sister (Rosie) as the protagonist. Stories were written for 3-year-old children and included an age-appropriate moral, e.g., sharing is fun, pick up after yourself or don’t run off while shopping. We explicitly chose plots that could be familiar to children (e.g., running off in a store, wanting a pet) because previous research found that familiar plot contexts facilitated children’s understanding of stories (Kim and Hall, 2002). Storybooks were written in standard British English (e.g., “Rosie tried hard to forget about having a pet and passed the tannin to her mum” rather than the more American: “Rosie tried hard not to think about having a pet and handed the tannin to her mom”).

Storybook illustrations were made by taking digital photographs of models acting out individual scenes (e.g., Mischief at the Toyshop includes a posed picture of Rosie exiting the toyshop with a toy in her hand followed by the security guard who has his hand on her shoulder). Photographs were then edited in Photoshop using the poster edges feature to make them look like drawings typical of commercially available children’s books (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Examples of the pictures used in different books containing the tannin (A) or zorch (B). (A) From left to right, the pictures are from: The Very Naughty Puppy (p. 2), Rosie’s Bad Baking Day (p. 6), and Nosy Rosie at the Restaurant (p. 7) and (B) The Mystery Auntie (p. 3), Mischief at the Toyshop (p. 9), and I Don’t Want to Share! (p. 7).

Each story was 10 pages long, including the cover. All stories had approximately the same number of total words (M = 381.33, SD = 29.75, range = 340–428) and words per page (M = 42.22, SD = 3.07, range = 38–47). The length and complexity of the books reflected those of commercially available books suitable for preschoolers. Copies of the materials are available from the authors.

Sixteen staff members at a local private daycare center (Mage = 26 years, 7 months, SD = 8 years, 6 months, range = 18 years, 3 months to 46 years, 3 days, 15 women) rated the stories. Adults were blind to both to the hypotheses and design of the main experiment. Ethical approval was granted by the School of Psychology Ethics Committee and adhered to the guidelines set out by the British Psychological Society. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. Adults were tested individually and rated stories using a Dell laptop computer in a quiet room at the daycare center. Using PowerPoint to display the stories, adults were given all nine stories to read in a random order. Adults read each story at their own pace and used the arrow keys to advance to the next page. After each story, adults were given a paper questionnaire and asked to rate the stories using a 5-point Likert-scale on how likely 3-year-old children would like the storybook overall, how comparable the plot was to commercially available books for 3- to 4-year-old children and how comparable the pictures were to commercially available books for 3- to 4-year-old children. Results indicated there were no differences between stories in adults impressions of how likely children were to like them overall [F(8,120) = 0.59, ns,  ] or how the plots [F(8,120) = 1.69, ns,

] or how the plots [F(8,120) = 1.69, ns,  ] and pictures [F(8,120) = 0.64, ns,

] and pictures [F(8,120) = 0.64, ns,  ] compared to commercially available books. The daycare center was given £50 in bookshop gift certificates for the staff members’ participation.

] compared to commercially available books. The daycare center was given £50 in bookshop gift certificates for the staff members’ participation.

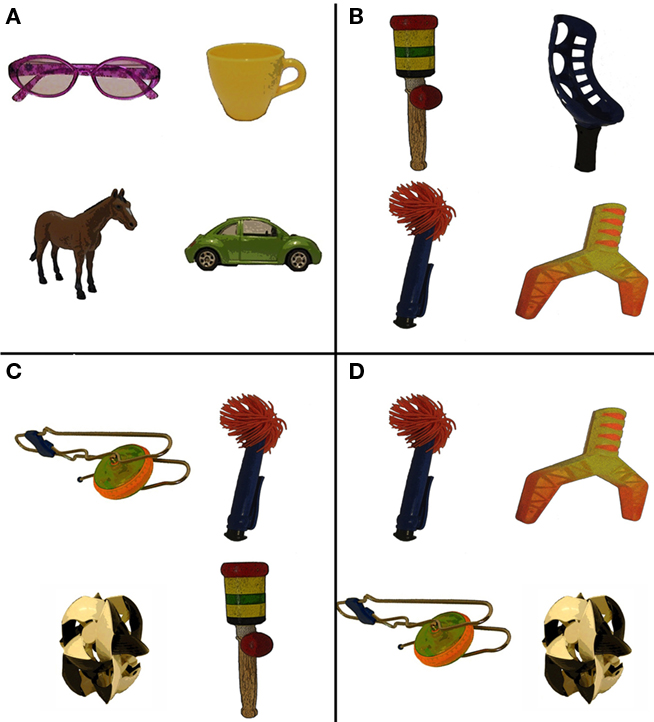

Test stimuli

To test whether children learned the words presented in the stories, a test booklet with three practice pages and 13 test pages was created (for similar methods with test booklets see, Goodman et al., 1998). Each A4 page of the test booklet included four pictures that were approximately the same size (M = 4.07 cm × 6.43 cm, SD = 1.25 cm). Pictures appeared on a decontextualized white background (see also, Meints et al., 2004; Schafer, 2005). We did not use the same pictures from the storybooks as testing with different pictures forces children to extend their newly formed name–object associations to a new representation of the referent (see, Sénéchal and Cornell, 1993; for a similar argument see also, Schafer, 2005).

Booklet pictures were made the same way as the storybook pictures (i.e., photographs of real objects altered using poster edges). One picture appeared in each quadrant (i.e., top left, top right, bottom left, bottom right (see also, Robbins and Ehri, 1994; Sénéchal, 1997)). Each practice page depicted four different familiar objects (e.g., glasses, cup, horse, and toy car, see Figure 2A). Each test page depicted four novel objects, each of which appeared in the stories (see Figures 2B–D). Across pages, novel objects appeared both with and without their direct competitors. For example, the manu (pen) and zorch (cup-and-ball game) were direct competitors because they appeared in the same stories. The manu and zorch both appeared on four test pages (i.e., with their direct competitor) and appeared individually on nine pages (i.e., without their direct competitor).

Figure 2. Examples of the objects shown on four test booklet pages. (A) an example from a practice page used for warm-up trials (p. i) and (B–D) examples from test pages used for both immediate recall and retention trials (pp. 5, 6, 8, respectively).

Other stimuli

A plastic, toy tea set (one teapot, one lid, two cups, two saucers) was used to familiarize the child to the experimenter at the beginning of the first visit.

Experimental Procedure

On each visit the experimenter sat with the child in a quiet room (usually on the living room couch) and either read three different stories or the same story three consecutive times, depending on condition.

At the beginning of the first visit, the experimenter and child played with a tea set to familiarize the child to the experimenter. The tea party continued until the child was comfortable enough to pass dishes to the experimenter or pour her tea (cf. Horst et al., 2009).

Reading phase

During the reading phase, children sat close to the experimenter to ensure the pictures were easy to see. If the child asked questions during the story the experimenter avoided naming any objects and encouraged the child to return attention to the story (e.g., “Hm. Let’s read on and see what happens next!”). Children’s questions and comments were neither encouraged nor discouraged (for a similar method, see Sénéchal and Cornell, 1993). Parents sat nearby and were instructed to remain quiet and avoid talking during the reading phase.

Children in the different stories condition were read all nine stories by the end of the week (see Figure 3). The order in which they heard the stories on each visit was counterbalanced across participants using a Latin Square design. All nine stories were read across children in the same stories condition (e.g., three children encountered the sprock and tannin in The Naughty Puppy, three in Rosie’s Bad Baking Day, and two in Nosy Rosie at the Restaurant). The order in which the novel name–object pairs (e.g., sprock and tannin) were encountered over the course of the experiment was also counterbalanced across participants using a Latin Square design.

Figure 3. Example of the procedure for children in the same stories condition (A) and different stories condition (B).

Thus, on each visit, every child encountered two name–object pairs 12 times each. For example, every child encountered the sprock 12 times and the zorch 12 times. Importantly, the number of naming instances and encounters was identical across conditions.

Warm-up trials

Immediately after the third story, the experimenter proceeded to the test phase, which began with warm-up trials to get the child used to pointing to pictures in the test booklet and to ensure the child understood the task. The experimenter opened the test booklet to a practice page and asked the child to point to each of the four pictures in a random order (e.g., “can you point to the dog?”) for a total of four warm-up trials. For example, the child might be shown practice page 1 (see Figure 2A), and asked to point to the cup, then the car, then the horse and finally the glasses. Thus, at the end of the warm-up trials the child had practiced pointing to an object in each quadrant (e.g., top left) on the page. Children were praised for correct choices (100% of trials). On each visit the experimenter presented the warm-up trials using a different practice page from the test booklet. The order in which the practice pages were used was counterbalanced across participants using a Latin Square. The trial order for each page was randomly determined for each child.

Immediate recall trials

Next, the experimenter tested immediate recall using the test booklet. In total, the child was asked to point to each of that visit’s target novel objects twice. For example, if the child heard the three stories with the manu and zorch, then the child would be presented with two manu and two zorch trials. On each trial, the experimenter turned to a different test page and asked the child to point to one of the four novel objects. For example, the child might first see page 8 (see Figure 2D), which depicted the pen, inverted slingshot, kinetic wheel and orb, and be asked to point to the manu (pen). Later, the child might see page 5 (see Figure 2B), which depicted the cup-and-ball game, the ball catcher, the pen and the inverted slingshot and be asked to point to the manu again. Across trials, targets were presented once with their direct competitor (i.e., the other novel object encountered during that visit) and once without their direct competitor. For example, the child would be presented with one manu trial where the zorch was also present among the competitors (e.g., Figure 2B) and one manu trial where the zorch was not present among the competitors (e.g., Figure 2D). Trial order, pages used and quadrant (e.g., top left) were counterbalanced within and across participants. The experimenter used a different test page for each test trial. Across participants, the same page was used to test different words. For example, page 5 was used to test zorch, coodle, manu, and sprock across participants. On the first and second visits, the experimenter only tested the child on that visit’s target novel name–object pairs (e.g., manu and zorch). That is, children only received warm-up trials and immediate recall trials on the first and second visit.

Retention trials

On the final visit, children received warm-up, immediate recall and retention trials. After the warm-up trials, the experimenter tested the child on that visit’s target novel name–object pairs (e.g., gaz and coodle) and then tested retention by testing the child on the name–object pairs from visits 1 and 2 (e.g., manu, zorch, sprock, and tannin). The retention trials were identical to the immediate recall trials except that children were asked to recall the name–object pairs that they had not seen or heard since visit 1 or 2. The order of the retention test (i.e., whether the trials for the name–object pairs from visit 1 or 2 were presented first) was counterbalanced across participants.

Coding

Children’s responses were noted on a datasheet by the experimenter during the session. To ensure reliability, parents also noted children’s responses for 25% of the children in each condition for all 16 trials (four warm-up, four immediate test, eight retention) on the final visit. Parents were naïve to the experimental hypotheses of the study (in fact, they were unaware that there were two conditions until after the experiment ended). Parents were given a coding sheet on which to mark the quadrant to which the child pointed (e.g., top left). During the reliability sessions, the child sat between the experimenter and parent and the experimenter noted children’s responses to the side, out of the parent’s view. Parents also noted responses out of the experimenter’s view. In general, children made very clear, unambiguous choices during the test trials. Inter-coder reliability was 100%.

Results

Preliminary analyses indicated that there were no differences between conditions in the total number of days over the course of the experiment [t(14) = 1.45, ns, d = 0.72], or average number of days between experimental sessions [t(14) = 1.57, ns, d = 0.78]. In the following analyses we first compare children’s performance to chance levels and then compare children’s performance between conditions.

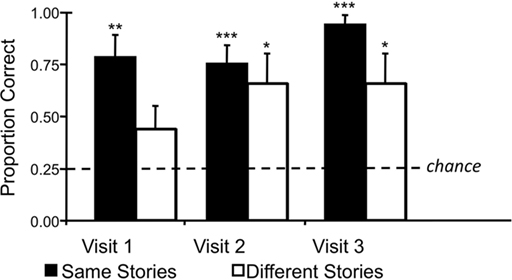

Immediate Recall

Overall, children did very well on the initial tests (see Figure 4). Children in the same stories condition chose the target object significantly more than expected by chance on each of the three visits, all ps < 0.001. Children in the different stories condition also chose the target object significantly more than expected by chance on the last two visits, both ps < 0.05, however, they did not choose the target significantly more than expected by chance on the first visit. We ran paired t-tests comparing recall accuracy between visits 1 and 3 and between visits 2 and 3 for the same stories condition, t(7) = 1.36, p > 0.22, d = 0.80, t(7) = 2.39, p = 0.05, d = 1.09, respectively. We also ran the test comparing visits 1 and 2 (p > 0.73) as well as identical t-tests for the different stories condition (all ps > 0.23). With Bonferroni correction none of these tests were significant.

Figure 4. Results from the immediate recall trials as a function of visit. The y-axis represents proportion of correct choices on the four-alternative test trials. The dotted line represents chance (0.25). Error bars represent one standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To test for differences between conditions, children’s proportion of correct choices were entered into a mixed-design ANOVA with Condition (Same Stories, Different Stories) as a between-subjects factor and Visit (First, Second, Third) as a repeated-measure. The ANOVA yielded a main effect of Condition, F(1,28) = 5.72, p < 0.05,  . Follow-up Fischer’s PLSD confirmed that children in the same stories condition were significantly better at choosing the target object at test than children in the different stories condition p < 0.05. Clearly, reading children the same stories repeatedly has a strong, positive effect on immediate recall for new words.

. Follow-up Fischer’s PLSD confirmed that children in the same stories condition were significantly better at choosing the target object at test than children in the different stories condition p < 0.05. Clearly, reading children the same stories repeatedly has a strong, positive effect on immediate recall for new words.

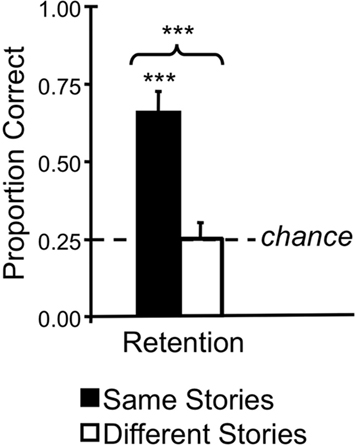

Retention

Of particular interest is how well children retained the novel name–object pairs. Children who heard the same stories repeatedly retained words at significantly greater than chance levels t(7) = 6.64, p < 0.001, d = 2.34 (see Figure 5). In contrast, children who heard the same number of novel name naming instances, but from different stories, did not retain at levels different from chance t(7) = 0.05, ns. Most importantly, children in the same stories condition performed 150% better on the retention trials than children in the different stories condition, t(14) = 5.25, p < 0.0001, d = 2.62 (see Figure 5). Overall then, these data suggest that reading children stories multiple times in succession has a dramatic beneficial effect on vocabulary learning.

Figure 5. Results from the retention trials. The y-axis represents proportion of correct choices on the four-alternative test trials. The dotted line represents chance (0.25). Error bars represent one standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

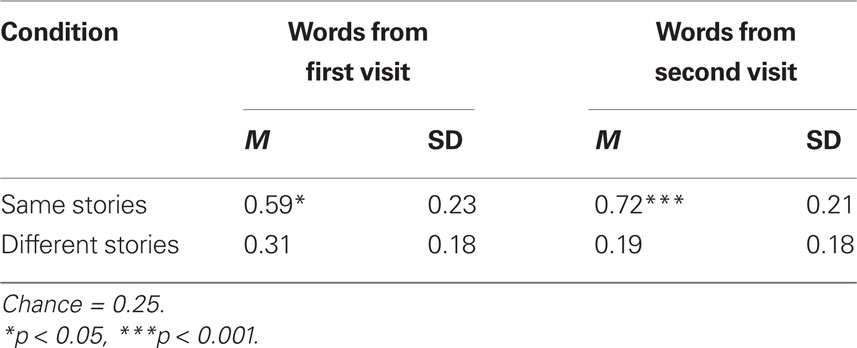

To test for differences between conditions and between when the words were introduced (i.e., delay before testing), children’s proportion of correct choices on the retention task were entered into a mixed-design ANOVA with Condition (Same Stories, Different Stories) as a between-subjects factor and Visit when the target words were initially presented (First, Second) as a repeated-measure (see Table 1). The ANOVA yielded a main effect of Condition, F(1,14) = 27.51, p < 0.001,  . Follow-up Fischer’s PLSD again confirmed that children in the same stories condition were significantly better at choosing the target object on the retention test than children in the different stories condition p < 0.05. No main effect of Visit was found. That is, children’s performance on the retention trials was not simply due to the effects of primacy or recency.

. Follow-up Fischer’s PLSD again confirmed that children in the same stories condition were significantly better at choosing the target object on the retention test than children in the different stories condition p < 0.05. No main effect of Visit was found. That is, children’s performance on the retention trials was not simply due to the effects of primacy or recency.

The Effect of Competition

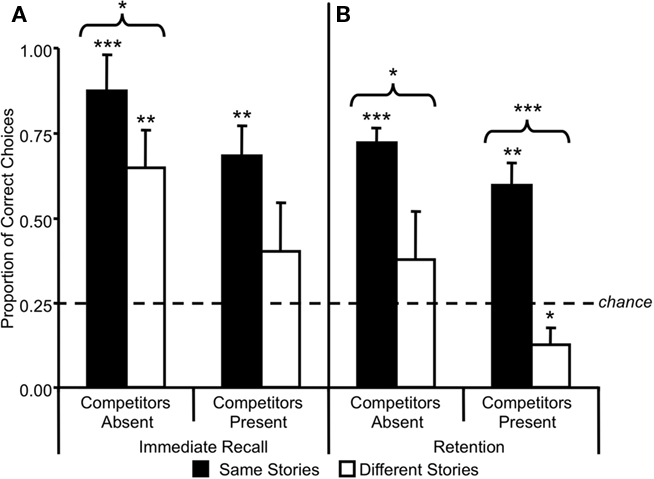

Finally, we were interested in whether competition between target words influenced children’s ability to learn words from storybooks. Specifically, we were interested in children’s performance as a function of whether the direct competitor (the other name–object pair that they had encountered on the same visit) was present or absent on the test trials. If children are learning both words at the same time, choosing the target on test trials should be more difficult when the direct competitor is present. First we analyzed the effect of competition on children’s immediate recall, then on their retention.

Competition on immediate recall

Children who heard the same stories repeatedly recalled the name–object pairs at levels significantly greater than chance both when the direct competitor was absent [t(7) = 14.66, p < 0.001, d = 5.17] and when the direct competitor was present [t(7) = 4.27, p < 0.01, d = 1.51, see Figure 6A]. In contrast, children who heard different stories only recalled the name–object pairs at levels significantly greater than chance when the direct competitor was absent [t(7) = 4.75, p < 0.01, d = 1.75], but not when the direct competitor was present [t(7) = 1.27, ns, d = 0.45, see Figure 6A]. That is, when the direct competitor was present the recall task was much more difficult for children who had heard different stories.

Figure 6. Results from the recall (A) and retention trials (B) as a function of whether the direct competitor was present. The y-axis represents proportion of correct choices on the four-alternative test trials. The dotted line represents chance (0.25). Error bars represent one standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To test for differences between conditions children’s proportion of correct choices on the immediate recall trials were submitted to a mixed-design ANOVA with Condition (Same Stories, Different Stories) as a between-subjects factor and Competition (Direct Competitor Present, Direct Competitor Absent) as a repeated-measure. The ANOVA yielded both a main effect of Condition, F(1,14) = 5.15, p < 0.05,  , and a main effect of Competition, F(1,14) = 12.70, p < 0.01,

, and a main effect of Competition, F(1,14) = 12.70, p < 0.01,  , see Figure 6A. Follow-up Fisher’s PLSD confirmed that children in the same stories condition were significantly more accurate than children in the different stories condition, p < 0.05, and that all children were more accurate when the direct competitor was absent than when it was present, p < 0.01. No other significant effects were found.

, see Figure 6A. Follow-up Fisher’s PLSD confirmed that children in the same stories condition were significantly more accurate than children in the different stories condition, p < 0.05, and that all children were more accurate when the direct competitor was absent than when it was present, p < 0.01. No other significant effects were found.

Competition on retention

Children who heard the same stories repeatedly also retained the name–object pairs at levels significantly greater than chance both when the direct competitor was absent [t(7) = 6.35, p < 0.001, d = 2.25] and when the direct competitor was present [t(7) = 5.22, p < 0.01, d = 5.22, see Figure 6B]. This is important because it suggests that these children were retaining the mappings for both words (the target and its direct competitor) and that their good performance on the retention trials was not simply due to good performance on trials where the direct competitor was absent. In contrast, children who heard different stories did not retain the name–object pairs at levels significantly greater than chance when the direct competitor was absent [t(7) = 1.32, ns, d = 1.75], and performed significantly less well than chance when the direct competitor was present [t(7) = −2.65, p < 0.05, d = −0.94, see Figure 6B]. Like the recall task, when the direct competitor was present the retention task was much more difficult for children who had heard different stories.

To test for differences between conditions children’s proportion of correct choices on the retention trials were submitted to a mixed-design ANOVA with Condition (Same Stories, Different Stories) as a between-subjects factor and Competition (Direct Competitor Present, Direct Competitor Absent) as a repeated-measure. The ANOVA yielded a main effect of Condition, F(1, 14) = 27.51, p < 0.001,  and a main effect of Competition, F(1,14) = 7.88, p = 0.01,

and a main effect of Competition, F(1,14) = 7.88, p = 0.01,  , see Figure 6B. Follow-up Fisher’s PLSD also confirmed that children in the same stories condition were significantly more accurate than children in the different stories condition, p < 0.001, and that all children were more accurate when the direct competitor was absent than when it was present, p = 0.01. No other significant effects were found. Taken together, these data suggest that competition between target words influences both recall and retention for new words encountered via shared storybook experience.

, see Figure 6B. Follow-up Fisher’s PLSD also confirmed that children in the same stories condition were significantly more accurate than children in the different stories condition, p < 0.001, and that all children were more accurate when the direct competitor was absent than when it was present, p = 0.01. No other significant effects were found. Taken together, these data suggest that competition between target words influences both recall and retention for new words encountered via shared storybook experience.

Discussion

The majority of children under 6 years of age own more than 50 books and approximately 80% of these children are read books in a typical day (Rideout et al., 2003). Indeed, much to the chagrin of their parents, young children often request stories to be read repeatedly (Sulzby, 1985; Crawley et al., 1999). Further, repetition has been shown to facilitate learning in general. Thus, in the current study we explored whether being repeatedly read the same storybooks facilitates young children’s word learning.

We systematically explored the effects of repeatedly reading the same storybooks in immediate succession on young children’s ability to recall and retain novel words. We read specially created storybooks to 3-year-old children over the course of 1 week. At each of the three sessions, children either heard three different stories with the same two novel name–object pairs or the same story three times. Using a four-alternative forced-choice task with pictures of the novel objects, we tested both immediate recall and retention in a decontextualized context (Schafer, 2005). Children who heard the same stories repeatedly were very accurate on both the immediate recall and retention tasks. In contrast, children who heard different stories were only accurate on immediate recall during the last two sessions and failed to demonstrate any ability to retain the new name–object associations. Importantly, all children had heard each novel word the same number of times during their shared storybook reading experiences. Overall, we found a dramatic increase in children’s ability to both recall and retain novel name–object associations encountered during shared storybook reading when they heard the same stories multiple times in succession.

Taken together, these findings add to a growing body of research demonstrating that children can learn words from incidental and non-ostensive contexts (Rice, 1990; Akhtar et al., 2001; Floor and Akhtar, 2006, see also Smith and Yu, 2008). These findings are also consistent with recent research demonstrating that re-reading the same picture books or re-watching the same television program facilitates learning. For example, Simcock and DeLoache (2008) recently showed 18- and 24-month-old children picture books of a child constructing a rattle. Children were either shown the book twice or four times in succession. Children who were exposed to four repetitions imitated the rattle-production sequence more accurately than those who only received two exposures. Similarly, preschool children who watched the same episode of a children’s television program five times performed much better on comprehension questions than children who had only seen the episode once (Crawley et al., 1999, for a similar effect, see Mares, 2006). Finally, using both picture books and additional materials (e.g., pictures cards), Schafer (2005) found that 1-year-old toddlers could learn up to five of eight target words in a 12-week training study. Again, re-reading facilitates learning.

Interestingly, in the current study we found a large effect without the use of dialogic reading (i.e., asking questions, expanding and modeling answers). In the current study we were interested in determining how well children learn words from storybooks based on the cognitive and perceptual demands of the task in the absence of dialogic reading. Several studies have already shown the usefulness of social interaction and pragmatic cues for word learning, in various situations (e.g., Heibeck and Markman, 1987; Baldwin, 1991; Moore et al., 1999; Jaswal and Markman, 2001; Booth and Waxman, 2003; Tomasello and Haberl, 2003). Further studies have demonstrated that children clearly benefit from similar social interaction during shared storybook reading. For example, children learn more from books when they are asked questions during reading (Sénéchal et al., 1995b; Blewitt et al., 2009), when the reader or child points to pictures as referents are introduced (Cornell et al., 1988; Sénéchal et al., 1995b) and when brief explanations are provided as new words are encountered (Brett et al., 1996). In light of these and similar findings it is likely that the effects found here would have been even stronger if dialogic reading techniques and additional pragmatic cues had been used. In contrast, the effects found here would likely have been weaker if the target words had included multiple word types (e.g., verbs, adjectives) rather than only nouns as other word types may be more difficult (Robbins and Ehri, 1994), in part because of lower imageability (see, Bird et al., 2001 for a review). Further, the findings from our analyses of competition between name–object pairs suggests that children in the different stories condition may have performed better if the direct competitors were always absent on test trials.

The findings from the current study are consistent with the account of word learning presented by Horst and Samuelson (2008) who argue that both highlighting the target object and decreasing attention to the competitor objects facilitates word learning via fast mapping. Highlighting the target object or object category can be achieved in several ways. First, one way to highlight the target is to increase encoding opportunities via repetition. Specifically, repetition may lead to stronger memory representations by increasing the attributes stored in memory (Simcock and DeLoache, 2008). Second, presenting children with a category (that is, multiple objects from the same category) may facilitate word learning by enabling comparison processes (see also, Schafer, 2005). For example, applying a common name to multiple, different exemplars invites children to compare those exemplars and draws their attention to their shared commonalities (Gentner and Namy, 1999; Waxman, 2003; Casasola et al., 2009). Finally, pragmatic cues such as eye gaze (Moore et al., 1999) and gesture (Booth et al., 2008) can highlight the target. Such cues may help children hone in on the target and spend more time encoding something about that object, thus contributing to the gradual slow mapping phase. However, some research has failed to find an advantage of such cues in the shared storybook reading domain (Cornell et al., 1988). Decreasing attention to the competitors can also be accomplished in several ways. For example, using lexical contrast (Carey and Bartlett, 1978), presenting fewer competitors overall (Horst et al., 2010), and repeating competitors throughout the task. In the current study, we sought to both highlight children’s attention to the target objects and decrease their attention to possible competitors via repetition. Specifically, by re-reading the same stories we have created a situation reminiscent of the “contextual cueing” (Chun and Jiang, 1998) effects observed in visual cognition research.

There is a rich literature in the visual cognition domain suggesting an advantage when contexts are repeated over learning (for a review, see Chun, 2000). Numerous studies have documented facilitation effects in processing visual stimuli when contexts (backdrops) are repeated (Jiang and Leung, 2005; Brockmole et al., 2008). Here, we show a contextual cueing effect for processing new words when contexts (stories) are repeated. In this case, we use “context” to refer to an individual illustration, which included a target referent and several possible competitors. This is generally consistent with the use of this term in the visual cognition literature (e.g., Chun and Jiang, 1998) and the fast mapping and word learning literature (e.g., Meints et al., 2004; Horst and Samuelson, 2008), but see Rohlfing et al., (2003) for alternative suggestions. Because storybooks typically include interesting and detailed illustrations, it is not surprising that we would find a similar effect to one observed in the visual cognition literature. Recent research on shared storybook reading demonstrates that both parents (Phillips et al., 2008) and children (Evans and Saint-Aubin, 2005) do not attend to the text during shared storybook reading experiences, further suggesting that the illustrations are an important part of the task for young children.

We hypothesize that children in the current study performed better in the same stories condition because the contextual repetition required fewer attentional resources, thus enabling children to better attend to the novel aspects of the stories: the new words. In other domains, contextual repetition enables inhibition of return (Chao and Yeh, 2006), that is, avoiding attending to something to which one previously attended. Here, contextual repetition likely enabled children to allocate less attention to the plots, characters and scenes as well as more attention to the novel name–object pairs each time the same story was repeated. Hearing the same stories repeatedly may also have helped children to predict what was to come next (Ardoin et al., 2008), again freeing up attentional resources. Taken together, these data suggest a role for both explicit learning (of the target) and implicit learning (of the context) in child language acquisition.

Of course, there are other possible explanations for these data. One possibility is that we tested children too early in the slow mapping phase. Biemiller and Boote (2006) argue that when the same word meaning is encountered in another context, a richer reference is likely to be established. It is possible, then, that children who heard different stories would eventually perform better than children who heard the same stories repeatedly – but that we tested children too early in the current study. Similarly, it is possible that these children would have performed better in a different task, such as extension trials in which they were asked to generalize a newly fast-mapped novel name to a new instance from the novel object category.

A second possibility is that the children in the two conditions focused on different aspects of the stories. Research on children’s reading fluency suggests that presenting words in different contexts may increase attention to the unknown words (Ardoin et al., 2008). It is possible, then, that children in the different stories condition focused more on the novel words while children in the same stories condition focused more on the novel objects. Because children were asked to recall the objects at test, the children in the same stories condition could have been at an advantage.

Finally, a third possibility is that some, but not too much, variability does facilitate word learning via storybooks. There was some variability in each story, because each novel object was depicted four times. For example, the tannin is seen four times in The Very Naughty Puppy: when Rosie helps make dinner, is asked to clean up, when the puppy chews it during the night and when the father fixes it. Thus, there was some variability even for children in the same stories condition, who saw each object depicted in four pictures. However, there was much more variability for children in the different stories condition, who saw each object depicted in 12 different pictures. We have not yet ruled out the possibility that there is a “sweet spot” for variability, which is much closer to the level of variability that the children in the same stories condition encountered. Also, although the two conditions did not differ in SES and maternal education it is possible that children in the same stories condition had larger vocabularies or some other a priori advantage over children in the different stories condition. New research is needed to address these alternative possibilities.

This study represents a first step in understanding how young children learn words from being read to and the underlying cognitive processes that support such learning. Future research should explore the role of variability in word learning, for example, whether there might be gains from variable inputs that cannot be observed in as little as 1 week, as well as other ways in which word learning can be facilitated via shared storybook reading, such as presenting multiple instances from to-be-learned novel categories (see also, Schafer, 2005). Much remains to be explored as few studies have investigated how children retain novel words encountered via shared storybook reading (but see, Sénéchal and Cornell, 1993).

Overall, the current study has multiple implications for understanding how young children acquire new words from storybooks and for word learning more generally. It demonstrates that repetition is important for learning new vocabulary from books. This is consistent with recent research suggesting that statistical learning is the mechanism underlying cross-situational word learning (Yu and Smith, 2007). These data also provide good news for parents: it is not necessarily the number of different books that matter, but rather following requests to “read it again!” This may be particularly encouraging for families from disadvantaged communities who tend to have fewer books available at home (Raikes et al., 2006). Taken together, this study provides novel insight into children’s amazing language acquisition abilities.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Portions of these data were presented as the second author’s undergraduate dissertation to the University of Sussex. We would like to thank Vanessa R. Simmering and Shannon Ross-Sheehy for helpful discussions and John J. Lipinski and Bob McMurray for reading previous versions of the manuscript. We also thank Ryan G. Kavlie and Emilly J. Scott for assistance in preparing the figures and Katherine E. Twomey and Sophie E. Williams for general assistance. We especially thank Conner Armstrong, Tyran Armstrong, Joseph Barnes, Judith Barnes, Alexander Baulch, Samantha Bryan, Susie Dart, Laura Heaps, Timothy Telford, Laura Walkden and her dog Bruno for posing as models in the storybook pictures, and Eastgate Baptist Church for the use of its facilities to create the various locations for the storybook scenes. Finally, we thank the parents, children, and staff at Early Years Childcare, Hove, who participated.

References

Akhtar, N., Jipson, J., and Callanan, M. A. (2001). Learning words through overhearing. Child Dev. 72, 416–430.

Ardoin, S. P., Eckert, T. L., and Cole, C. A. S. (2008). Promoting generalization of reading: a comparison of two fluency-based interventions for improving general education student’s oral reading rate. J. Behav. Educ. 17, 237–252.

Baldwin, D. A. (1991). Infants’ contribution to the achievement of joint reference. Child Dev. 62, 875–890.

Biemiller, A., and Boote, C. (2006). An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 44–62.

Bird, H., Franklin, S., and Howard, D. (2001). Age of acquisition and imageability ratings for a large set of words, including verbs and function words. Behav. Res. Methods 33, 73–79.

Blake, J., Macdonald, S., Bayrami, L., Agosta, V., and Milian, A. (2006). Book reading styles in dual-parent and single-mother families. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 76, 501–515.

Blewitt, P., Rump, K. M., Shealy, S. E., and Cook, S. A. (2009). Shared book reading: when and how questions affect young children’s word learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 294–304.

Booth, A. E., McGregor, K. K., and Rohlfing, K. J. (2008). Socio-pragmatics and attention: contributions to gesturally guided word learning in toddlers. Lang. Learn. Dev. 4, 179–202.

Booth, A. E., and Waxman, S. R. (2003). Mapping words to the world in infancy, infants’ expectations for count nouns and adjectives. J. Cogn. Dev. 4, 357–381.

Bornstein, M. H., and Mash, C. (2010). Experience-based and on-line categorization of objects in early infancy. Child Dev. 81, 884–897.

Brett, A., Rothlein, L., and Hurley, M. (1996). Vocabulary acquisition from listening to stories and explanations of target words. Elem. School J. 96, 415–422.

Brockmole, J. R., Hambrick, D. Z., Windisch, D. J., and Henderson, J. M. (2008). The role of meaning in contextual cueing: evidence from chess expertise. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 61, 1886–1896.

Bus, A. G. (2001). “Parent–child book reading through the lens of attachment theory,” in Literacy and Motivation: Reading Engagement in Individuals and Groups, eds L. Verhoeven and C. Snow (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 39–53.

Capone, N. C., and McGregor, K. K. (2005). The effect of semantic representation on toddler’s word retrieval. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 48, 1468–1480.

Carey, S. (1978). “The child as word learner,” in Linguistic Theory and Psychological Reality, eds M. Halle, J. Bresnan, and A. Miller (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 264–293.

Carey, S., and Bartlett, E. (1978). Acquiring a single new word. Proc. Stanford Child Lang. Conf. 15, 17–29.

Casasola, M., Bhagwat, J., and Burke, A. S. (2009). Learning to form a spatial category of tight-fit relations: how experience with a label can give a boost. Dev. Psychol. 45, 711–723.

Chao, H.-F., and Yeh, Y.-Y. (2006). Inhibition of return lasts longer at repeatedly stimulated locations than at novel locations. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 13, 896–901.

Chun, M. M., and Jiang, Y. (1998). Contextual cueing: implicit learning and memory of visual context guides spatial attention. Cogn. Psychol. 36, 28–71.

Cornell, E. H., Sénéchal, M., and Broda, L. S. (1988). Recall of picture books by 3-year-old children: testing and repetition effects in joint reading activities. J. Educ. Psychol. 80, 537–542.

Crawley, A. M., Anderson, D. R., Wilder, A., Williams, M., and Santomero, A. (1999). Effects of repeated exposures to a single episode of the television program Blue’s Clues on the viewing behaviors and comprehension of preschool children. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 630–637.

Evans, M. A., and Saint-Aubin, J. (2005). What children are looking at during shared storybook reading. Psychol. Sci. 16, 913–920.

Fletcher, K. L., and Reese, E. (2005). Picture book reading with young children: a conceptual framework. Dev. Rev. 25, 64–103.

Floor, P., and Akhtar, N. (2006). Can 18-month-old infants learn words by listening in on conversations? Infancy 9, 327–339.

Ganea, P. A., Allen, M. L., Butler, L., Carey, S., and DeLoache, J. S. (2009). Toddlers’ referential understanding of pictures. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 104, 283–295.

Gentner, D., and Namy, L. L. (1999). Comparison in the development of categories. Cogn. Dev. 14, 487–513.

Goodman, J. C., McDonough, L., and Brown, N. B. (1998). The role of semantic context and memory in the acquisition of novel nouns. Child Dev. 69, 1330–1344.

Halberda, J. (2006). Is this a dax which I see before me? Use of the logical argument disjunctive syllogism supports word-learning in children and adults. Cogn. Psychol. 53, 310–344.

Heibeck, T. H., and Markman, E. M. (1987). Word learning in children – an examination of fast mapping. Child Dev. 58, 1021–1034.

Horst, J. S., Ellis, A. E., Samuelson, L. K., Trejo, E., Worzalla, S. L., Peltan, J. R., and Oakes, L. M. (2009). Toddlers can adaptively change how they categorize: same objects, same session, two different categorical distinctions. Dev. Sci. 12, 96–105.

Horst, J. S., McMurray, B., and Samuelson, L. K. (2006). “Online processing is essential for learning: understanding fast mapping and word learning in a dynamic connectionist architecture,” in Proceedings from the 28th Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Vancouver, 339–344.

Horst, J. S., and Samuelson, L. K. (2008). Fast mapping but poor retention by 24-month-old infants. Infancy 13, 128–157.

Horst, J. S., Scott, E. J., and Pollard, J. P. (2010). The role of competition in word learning via referent selection. Dev. Sci. 13, 706–713.

Jaswal, V. K., and Markman, E. M. (2001). Learning proper and common names in inferential versus ostensive contexts. Child Dev. 72, 768–786.

Jiang, Y., and Leung, A. W. (2005). Implicit learning of ignored visual context. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 12, 100–106.

Kim, D., and Hall, J. K. (2002). The role of an interactive book reading program in the development of second language pragmatic competence. Mod. Lang. J. 86, 332–348.

Lonigan, C. J., Shanahan, T., and Cunningham, A. (2008). “Impact of shared-reading intervention on young children’s early literacy skills,” in Developing Early Literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel (Washington, DC: National Institute for Literacy), 153–171.

Lonigan, C. J., and Whitehurst, G. J. (1998). Relative efficacy of parent and teacher involvement in a shared-reading intervention for preschool children from low-income backgrounds. Early Child. Res. Q. 13, 263–290.

Mares, M.-L. (2006). Repetition increases children’s comprehension of television content – up to a point. Commun. Monogr. 73, 216–241.

Mather, E., and Plunkett, K. (2009). Learning words over time: the role of stimulus repetition in mutual exclusivity. Infancy 14, 60–76.

McMurray, B., Horst, J. S., Toscano, J., and Samuelson, L. K. (2009). “Connectionist learning and dynamic processing: symbiotic developmental mechanisms,” in Towards a New Grand Theory of Development? Connectionism and Dynamic Systems Theory Reconsidered, eds J. P. Spencer, M. Thomas, and J. McClelland (New York: Oxford University Press), 218–249.

Meints, K., Plunkett, K., Harris, P. L., and Dimmock, D. (2004). The cow on the high street: effects of background context on early naming. Cogn. Dev. 19, 275–290.

Moore, C., Angelopoulos, M., and Bennett, P. (1999). Word learning in the context of referential and salience cues. Dev. Psychol. 351, 60–68.

Penno, J. F., Wilkenson, I. A., and Moore, D. W. (2002). Vocabulary acquisition from teacher explanation and repeated listening to stories: do they overcome the Matthew effect? J. Educ. Psychol. 94, 23–33.

Phillips, L. M., Norris, S. P., and Anderson, J. (2008). Unlocking the door: is parents’ reading to children the key to early literacy development? Can. Psychol. 49, 82–88.

Raikes, H., Luze, G., Brooks-Gunn, J., Raikes, H. A., Pan, B. A., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Constantine, J., Tarullo, L. B., and Rodriguez, E. T. (2006). Mother–child bookreading in low-income families: correlates and outcomes during the first three years of life. Child Dev. 77, 924–953.

Rice, M. (1990). “Preschoolers’ QUIL: quick incidental learning of words,” in Children’s Language, eds G. Conti-Ramsden and C. E. Snow (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 171–194.

Riches, N. G., Tomasello, M., and Conti-Ramsden, G. (2005). Verb learning in children with SLI: frequency and spacing effects. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 48, 1397–1411.

Rideout, V. J., Vanderwater, E. A., and Wartella, E. A. (2003). Zero to Six. Electronic Media in the Lives of Infants, Toddlers and Preschoolers. Menlo Park, CA: The Kaiser Family Foundation.

Robbins, C., and Ehri, L. C. (1994). Reading storybooks to kindergartners helps them learn new vocabulary words. J. Educ. Psychol. 86, 54–64.

Rohlfing, K. J., Rehm, M., and Geocke, K. U. (2003). Situatedness: the interplay between contexts and situation. J. Cogn. Cult. 3, 132–156.

Schafer, G. (2005). Infants can learn decontextualized words before their first birthday. Child Dev. 76, 87–96.

Schafer, G., and Plunkett, K. (1998). Rapid word learning by fifteen-month-olds under tightly controlled conditions. Child Dev. 69, 309–320.

Sénéchal, M. (1997). The differential effect of storybook reading on preschoolers’ acquisition of expressive and receptive vocabulary. J. Child Lang. 24, 123–138.

Sénéchal, M., and Cornell, E. H. (1993). Vocabulary acquisition through shared reading experiences. Read. Res. Q. 28, 361–374.

Sénéchal, M., Cornell, E. H., and Broda, L. S. (1995a). Age-related differences in the organization of parent–infant interactions during picture-book reading. Early Child. Res. Q. 10, 317–337.

Sénéchal, M., Thomas, E., and Monker, J.-A. (1995b). Individual differences in 4-year-old children’s acquisition of vocabulary during storybook reading. J. Educ. Psychol. 87, 218–229.

Simcock, G., and DeLoache, J. S. (2006). Get the picture? The effects of iconicity on toddlers’ reenactment from picture books. Dev. Psychol. 42, 1352–1357.

Simcock, G., and DeLoache, J. S. (2008). The effect of repetition on infants’ imitation from picture books varying in iconicity. Infancy 13, 687–697.

Smith, L. B., and Yu, C. (2008). Infants rapidly learn word-referent mappings via cross-situational statistics. Cognition 106, 1558–1568.

Sulzby, E. (1985). Children’s emergent reading of favorite storybooks: a developmental study. Read. Res. Q. 20, 458–481.

Swingley, D. (2010). Fast mapping and slow mapping in children’s word learning. Lang. Learn. Dev. 6, 179–183.

Tare, M., Chiong, C., Ganea, P., and DeLoache, J. S. (2010). Less is more: how manipulative features affect children’s learning from picture books. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 31, 395–400.

Tomasello, M., and Haberl, K. (2003). Understanding attention: 12- and 18-month-olds know what is new for other persons. Dev. Psychol. 39, 906–912.

Valdez-Menchaca, M. C., and Whitehurst, G. J. (1992). Accelerating language development through picture book reading: a systematic extension to Mexican day care. Dev. Psychol. 28, 1106–1114.

Waxman, S. R. (2003). “Links between object categorization and naming: origins and emergence in human infants,” in Early Category and Concept Development: Making Sense of the Blooming, Buzzing Confusion, eds D. H. Rakison and L. M. Oakes (New York: Oxford University Press), 213–241.

Whitehurst, G. J., Falco, F. L., Lonigan, C. J., Fischel, J. E., DeBaryshe, B. D., Valdez-Menchaca, M. C., and Caulfield, M. (1988). Accelerating language development through picture book reading. Dev. Psychol. 24, 552–559.

Keywords: shared book reading, fast mapping, word learning, contextual learning, language acquisition

Citation: Horst JS, Parsons KL and Bryan NM (2011) Get the story straight: contextual repetition promotes word learning from storybooks. Front. Psychology 2:17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00017

Received: 26 June 2010;

Accepted: 21 January 2011;

Published online: 17 February 2011.

Edited by:

Katie Alcock, Lancaster University, UKReviewed by:

Katharina Rohlfing, Bielefeld University, GermanyKerstin Meints, University of Lincoln, UK

Copyright: © 2011 Horst, Parsons and Bryan. This is an open-access article subject to an exclusive license agreement between the authors and Frontiers Media SA, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Jessica S. Horst, School of Psychology, University of Sussex, Pevensey 1 Building, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9QH, UK.e-mail:amVzc2ljYUBzdXNzZXguYWMudWs=