95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 28 June 2017

Sec. Psychopathology

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00112

This article is part of the Research Topic Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Consequences of Maladaptive Habits View all 11 articles

Hoarding disorder is characterized by a persistent difficulty discarding items, the desire to save items to avoid negative feelings associated with discarding them, significant accumulation of possessions that clutter active living areas and significant distress or impairment in areas of functioning. We present a case of a 52-year-old married man who was referred to the psychiatry department for collecting various objects that were deposited unorganized in the patient’s house. He reported to get anxious when someone else discarded some of these items. This behavior had started about 20 years earlier and it worsened with time. The garage, attic, and surroundings of his house were cluttered with these objects. On admission, in the mental status examination, it was observed that the patient was vigil, calm, and oriented; his mood was depressed; his speech was organized, logic, and coherent; and there were no psychotic symptoms. A psychotherapeutic plan was designed for the patient, including psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and exposure to discarding objects. A pharmacological treatment with fluvoxamine 100 mg tid and quetiapine 200 mg was added to the therapeutic plan, with the progressive improvement of the symptoms. Nine months later, the patient was able to sell/recycle most of the items. Studies evaluating treatment for HD are necessary to improve the quality of life of the patients and to reduce the hazards associated with the disorder.

The concept of hoarding was defined in 1996 as a behavioral phenomenon of acquisition of objects and failure to discard objects (1).

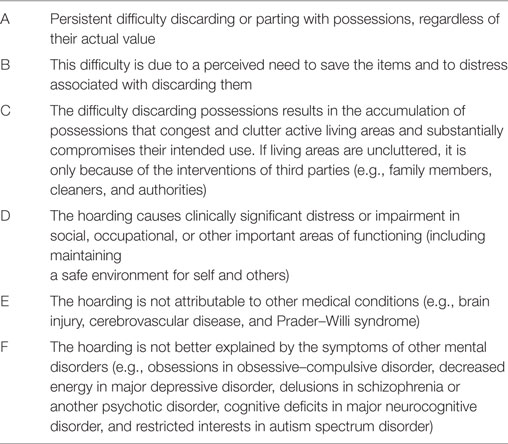

Compulsive hoarding was first included as diagnostic criteria for obsessive–compulsive personality disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—third Edition Revised. Clinical hoarding began to be considered secondary to some disorders, such as dementia, residual schizophrenia, eating disorders, brain injury, autism spectrum disorders, or compulsive buying (2). Later, hoarding was considered a subtype or dimension of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), with this behavior being seen in about 18–40% patients (2). However, hoarding would be seen frequently independent from other psychiatric disorders. After focusing on the epidemiological, phenomenological, and neurobiological aspects of hoarding, hoarding disorder (HD) was included as an isolated entity, in OCD spectrum, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth Edition (DSM-V). The criteria for diagnosis of HD in DSM-V are a persistent difficulty discarding items, the desire to save items in order to avoid negative feelings associated with discarding them, significant accumulation of possessions that clutter active living areas, and significant distress or impairment in areas of functioning (Table 1) (3). Usually, these items are perceived to be useful in the future or to be esthetic or cause an emotional attachment (1, 4). If clutter is severe, it can cause threats to public health and safety (such as fire hazards and falls) (5).

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for Hoarding disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-V).

In contrast to hoarding in OCD, the thoughts of not discarding in patients with HD are not considered by the patients to be intrusive, repetitive, or egodystonic (6). Besides, stress in HD is associated with the consequence of the clutter of the items and not related to the content of the thoughts associated with the reasons to not discard objects.

Compulsive hoarding affects about 2–5% of the population (7–9). Hoarding behaviors usually start at a subclinical level in early adolescence and worsens with each decade (10–12). Often the disorder becomes clinically significant only in middle-aged patients, with the distress associated to HD being caused by the intervention of others, such as relatives or local authorities (13). Stressful or traumatic events may be associated with the onset of hoarding symptoms (11).

Other psychiatric disorders often co-occur with HD. The most frequent comorbidity is a major depression, which can be present in up to 50% of the cases (14). Attention deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) is also a common comorbidity with HD, with some studies suggesting association with inattentive symptoms of the disorder (15). Poorer general health is also associated with HD (16).

The cognitive behavioral model conceptualized for HD proposes that compulsive hoarding develops through emotional responses associated with the beliefs about possessions. This model proposes (1, 17):

1. Information processing deficits (including avoiding/delaying decisions with fear of making wrong decisions, self-report of inattentiveness and difficulty remembering/recording memories, and deficits in categorization/organization).

2. Emotional attachment and beliefs (of responsibility and control) for the possessions.

3. Maladaptive behavioral patterns (avoiding discarding objects which is associated with negative emotions, and acquiring and saving associated with positive emotions).

4. The cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) designed to address HD involves assessment and psychoeducation on symptoms, motivation enhancement, cognitive restructuring, exposure to non-acquiring, and discarding and prevention of relapse (17, 18). One meta-analysis that focused on the results of CBT in patients with HD showed that symptoms decrease significantly after treatment with large effect size, especially with the difficulty to discard component of the disease (17). In the same study, rates of clinically significant changes were modest, with most patients continuing to score in the clinical range at posttreatment (17). Pharmacological treatment of HD disorder is not well established, since most studies evaluating treatment were made in patients with an OCD diagnosis with a hoarding component. Most of these studies used serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and the results were associated with poor response to treatment (19). A meta-analysis evaluated the effect of pharmacotherapy in patients with pathological hoarding (either diagnosed with OCD with hoarding component or HD) and response to treatment observed was 37–76% (20). In this study, only two studies focused on patients with HD. An open label trial used venlafaxine in monotherapy, in which 70% of the patients were classified as responders (decrease of ≥30% in the UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale and Saving Inventory—Revised and at least “much improved” on the Clinical Global Impression-Improvement) (21). The second study, a case series (n = 4) using methylphenidate, since there are some studies that point out the association between HD and ADHD, did not have significance in the resolution of hoarding symptoms (22).

We present a case of a 52-year-old married man, who has the sixth grade, and works as a mechanic. He has no previous history of medical conditions. As a psychiatric background, he reported depressive symptoms following the death of his only son 22 years ago.

The patient was referred to treatment at the psychiatry department of Hospital de Braga for the first time by his family doctor for collecting various objects, predominantly stones, papers, and damaged pieces of cars that were deposited unorganized in the patient’s house. The patient collected these items because he thought they were valuable and/or usable in the future, but recognized that the collection was exaggerated. He could not discard any of these items, even if he never used them when needed. He reported to get anxious when someone else discarded some of these items. This behavior had started about 20 years earlier and it worsened with time. Despite, the thoughts of the possible use of these items were the reason why he could not throw out the possessions, these thoughts were not considered intrusive, repetitive, or egodystonic. The garage, attic, and surroundings of his house were cluttered with these objects (Figure 1). The clutter in his house is classified in to seven categories according to the clutter image rating (23, 24).

Figure 1. Patient’s house at beginning of medical intervention. Photo was taken and provided by patient. Consent for publication was obtained.

On admission, in the mental status examination, it was observed that the patient was vigil, calm, and oriented; his mood was depressed; his speech was organized, logic, and coherent; and there were no psychotic symptoms.

A psychotherapeutic plan for the patient was designed. The goals were to understand and educate the patient on his symptoms and beliefs, so he could understand the need of treatment. Cognitive restructuring of the beliefs and exposure to non-acquire and discard the objects saved were also explored. Along with the psychotherapeutic plan, a pharmacological treatment with fluvoxamine 100 mg id and trazodone 150 mg id was made, to treat the coexistent depressive symptoms and insomnia. During the first 6 months of treatment, the patient continued to buy and collect objects. Then, fluvoxamine was gradually augmented to 100 mg tid and quetiapine 200 mg was added to the treatment plan, with progressive improvement in the symptoms and the patient being able to sell/recycle most of the items after 9 months of this treatment (Figure 2). The patient is currently medicated with quetiapine 100 mg id for insomnia and organized the spaces cluttered (Figure 3). The patient and his wife were very gratified with the results.

Figure 3. Patient’s house after medical treatment. Photo was taken and provided by the patient. Consent for publication was obtained.

This study was performed in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki 2008 and was approved by the ethics eommittee of Hospital of Braga. We obtained informed written consent from the patient authorizing publication of clinical case and his photographs. His anonymity has been preserved.

We presented a patient who suffered from HD. The case was managed with both pharmacotherapy and a reduced number of psychotherapeutic sessions, which may be of interest in times of restrictions on available psychiatric and psychotherapeutic resources.

The clinical features of his object hoarding showed a typical pattern. The patient had an inability to discard objects and had an accumulation behavior with a long evolution over time. He was referred to the psychiatric treatment about 20 years after the beginning of the accumulation symptoms. Delay in seeking treatment for HD is very common and, if not treated, the evolution of the disorder occurs with progressive worsening of the behaviors.

The possessions collected did not have any value, and the thought that the possessions may be needed in the future did not have any characteristics of an obsession, such as being repetitive or egodystonic. In the same vein, the anxiety caused by the disorder was associated with the fact that he did not want to get rid of the items because he thought they could be valuable and no thought of something bad could happen, as typical in OCD. In addition, collected items disturbed the normal organization of his house and were cluttered.

Interestingly, the accumulation behavior began a few years after the death of his son. In fact, HD onset (as other obsessive-related disorders) is commonly associated with chronic stress and important life events (11, 25).

Hoarding disorder is mainly treated with CBT, including psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, classic cognitive techniques focused on dysfunctional beliefs, and exposures targeting sorting and discarding. Patients could also benefit with some pharmacological interventions.

In the presented case, the psychotherapeutic plan included a reduced number of sessions (basically due to limitations on available resources) and a combined pharmacologic approach.

Although no medications are currently marketed to treat HD, some studies identified benefits with the use of serotoninergic drugs in this disorder as in other disorders of the obsessive spectrum (19, 26). Treatment with fluvoxamine was chosen, not only for its characteristics of reduction of anxiety but also to address insomnia and depressive symptoms presented by the patient. Given that the patient did not tolerate trazodone, it was necessary to optimize the treatment for this problem, which constituted an opportunity for the use of quetiapine. Although there are no studies to evaluate the efficacy of quetiapine in this disorder, this case study illustrates its benefit that besides improving the sleep it seems to have contributed to lower the levels of anxiety in this patient.

Overall, the conjugation of described psychotherapeutic and pharmacotherapeutic approach contributed to significant improvement of the patient’s symptoms until sustained remission.

Future studies regarding the treatment of HD are necessary to address the difficulties of these patients and to improve their quality of life.

This study was performed in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki 2008 and was approved by the ethics Committee of Hospital of Braga. We obtained informed written consent from the patient authorizing publication of clinical case and his photographs. His anonymity has been preserved.

DV and PM observed the patient, collected and analyzed the data. DV, JG, and PM wrote the paper. All authors approved the final work.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Frost RO, Hartl TL. A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther (1996) 34(4):341–50. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(95)00071-2

2. Pertusa A, Frost RO, Fullana MA, Samuels J, Steketee G, Tolin D, et al. Refining the diagnostic boundaries of compulsive hoarding: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev (2010) 30(4):371–86. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.007

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publ (2013). 947 p.

4. Steketee G, Frost R. Compulsive hoarding: current status of the research. Clin Psychol Rev (2003) 23(7):905–27. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2003.08.002

5. Frost RO, Steketee G, Williams L. Hoarding: a community health problem. Health Soc Care Community (2000) 8(4):229–34. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2524.2000.00245.x

6. Morgado P, Freitas D, Bessa JM, Sousa N, Cerqueira JJ. Perceived stress in obsessive–compulsive disorder is related with obsessive but not compulsive symptoms. Front Psychiatry (2013) 2(4):21.

7. Iervolino AC, Perroud N, Fullana MA, Guipponi M, Cherkas L, Collier DA, et al. Prevalence and heritability of compulsive hoarding: a twin study. Am J Psychiatry (2009) 166(10):1156–61. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121789

8. Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Grados MA, Cullen B, Riddle MA, Liang K, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behav Res Ther (2008) 46(7):836–44. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.004

9. Mueller A, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Glaesmer H, de Zwaan M. The prevalence of compulsive hoarding and its association with compulsive buying in a German population-based sample. Behav Res Ther (2009) 47(8):705–9. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.005

10. Ayers CR, Saxena S, Golshan S, Wetherell JL. Age at onset and clinical features of late life compulsive hoarding. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2010) 25(2):142–9. doi:10.1002/gps.2310

11. Grisham JR, Frost RO, Steketee G, Kim H-J, Hood S. Age of onset of compulsive hoarding. J Anxiety Disord (2006) 20(5):675–86. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.07.004

12. Tolin DF, Meunier SA, Frost RO, Steketee G. Course of compulsive hoarding and its relationship to life events. Depress Anxiety (2010) 27(9):829–38. doi:10.1002/da.20684

13. Mataix-Cols D, Frost RO, Pertusa A, Clark LA, Saxena S, Leckman JF, et al. Hoarding disorder: a new diagnosis for DSM-V? Depress Anxiety (2010) 27(6):556–72. doi:10.1002/da.20693

14. Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin DF. Comorbidity in hoarding disorder. Depress Anxiety (2011) 28(10):876–84. doi:10.1002/da.20861

15. Tolin DF, Villavicencio A. Inattention, but not OCD, predicts the core features of hoarding disorder. Behav Res Ther (2011) 49:120–5. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.002

16. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Gray KD, Fitch KE. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiatry Res (2008) 160(2):200–11. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.008

17. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, Muroff J. Cognitive behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety (2015) 32(3):158–66. doi:10.1002/da.22327

18. Frost RO, Steketee G, Greene KA. Cognitive and behavioral treatment of compulsive hoarding. Brief Treat Crisis Interv (2003) 3(3):323. doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhg024

19. Saxena S. Neurobiology and treatment of compulsive hoarding. CNS Spectr (2008) 13(S14):29–36. doi:10.1017/S1092852900026912

20. Brakoulias V, Eslick GD, Starcevic V. A meta-analysis of the response of pathological hoarding to pharmacotherapy. Psychiatry Res (2015) 229(1–2):272–6. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.019

21. Saxena S, Sumner J. Venlafaxine extended-release treatment of hoarding disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol (2014) 29(5):266–73. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000036

22. Rodriguez CI, Bender J, Morrison S, Mehendru R, Tolin D, Simpson HB. Does extended release methylphenidate help adults with hoarding disorder? A case series. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2013) 33(3):444–7. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318290115e

23. Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin D, Renaud S. Development and validation of the clutter image rating. J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2008) 30:193–203. doi:10.1007/s10862-007-9068-7

24. International OCD Foundation. Clutter Image Rating. (2017). Available from: http://hoardingdisordersuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/clutter-image-ratings.pdf

25. Morgado P, Sousa N, Cerqueira JJ. The impact of stress in decision making in the context of uncertainty. J Neurosci Res (2015) 93(6):839–47. doi:10.1002/jnr.23521

Keywords: hoarding disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorders, antipsychotics, psychotherapy, clinical case study

Citation: Vilaverde D, Gonçalves J and Morgado P (2017) Hoarding Disorder: A Case Report. Front. Psychiatry 8:112. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00112

Received: 31 March 2017; Accepted: 09 June 2017;

Published: 28 June 2017

Edited by:

Leandro Fernandes Malloy-Diniz, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, BrazilReviewed by:

Michael Grady Wheaton, Yeshiva University, United StatesCopyright: © 2017 Vilaverde, Gonçalves and Morgado. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pedro Morgado, cGVkcm9tb3JnYWRvQG1lZC51bWluaG8ucHQ=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.