- Institute of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany

Forms of democratic backsliding can be observed in many parts of the world. However, some conclusions are overly sweeping or alarmist. A detailed case-based regional analysis reveals distinct patterns in this regard. This study highlights some recent findings from a longitudinal international research project, the Transformation Research Initiative “(TRI), which is now based at the Center for Research on Democracy (CREDO) at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. The project involves country and regional experts from all major world areas. The results presented here are derived from the Varieties of Democracy “(V-Dem) data at the macro level, World Values Surveys” (WVS) data on the micro level, and selected case studies. Only a few key findings can be presented here. For a detailed account, see van Beek (ed., 2022).

1 Introduction

In contemporary society, numerous factors elicit concern: the recent pandemic, which carries long-term ramifications; the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, which has global economic and political repercussions, including issues related to energy, food, and renewed competition among global systems; instances of democratic backsliding; the rise of populism; and increasing social polarization. Indeed, we are experiencing a confluence of crises. However, one must inquire: Is there also a pervasive crisis of democracy?

According to the V-Dem report (2022), “The level of democracy … has reverted to levels observed in 1989. The past three decades of democratic advancements have now been negated” (Executive Summary, p. 6). This assessment is based on population-weighted indices of both liberal and electoral democracy. However, in my opinion, this perspective is overly broad and alarmist.

For example, the situation in India alone significantly influences the global trend (liberal democracy index: 2014–0.54; 2021–0.36; electoral democracy index: 2014–0.67, 2021–0.44). While Prime Minister Modi’s and the BJP’s Hindu nationalist policies have affected democratic indicators, India, with its federal system, independent judiciary, media, and robust opposition and civil society, continues to function as an electoral democracy.1 A more nuanced approach and thorough analyses are required.

Although numerous studies have explored democratic backsliding (e.g., Bermeo, 2016; Freedom House, 2020; Haggard and Kaufman, 2021) and even the potential loss of lives (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018), the resilience and long-term strengths of democracies have garnered insufficient attention. A notable exception is the special issue of “Democratization” (Merkel and Lührmann, 2021). In their definition, they state: “Democratic resilience is the ability of a democratic system, its institutions, political actors, and citizens to prevent or respond to external and internal challenges, stresses, and assaults through one or more of three potential reactions: to endure without changes, to adapt through internal modifications, and to recover without losing the democratic character of its regime, along with its core institutions, organizations, and processes. The more resilient democracies are at all four levels of the political system (political community, institutions, actors, citizens), the less vulnerable they tend to be in both the present and the future” (p. 874).

This definition is notably comprehensive and can be further specified: Democracies, by their very nature, are conflictual and dynamic systems. The primary feedback mechanisms, in a functional sense, consist of regular competitive elections and a high level of political participation. These are the key elements of a “polyarchy,” as articulated by Dahl (1971), or, in contemporary terminology, an „electoral democracy.” To classify elections as “equal, free, and fair,” they must be safeguarded by an independent electoral commission and, if necessary, the judiciary, thereby introducing a normative dimension. Furthermore, fundamental human rights and liberties, including freedom of speech and the right to information, must also be preserved for a political system to qualify as a genuinely “liberal democracy.” The main mechanisms of democratic resilience at the institutional (macro-) level encompass both vertical (electorate – representatives) and horizontal (inter-institutional: legislative – executive – judiciary) accountability. At the meso-level, particularly within large-scale representative democracies, a well-functioning party system that facilitates the representation of all significant social groupings, coupled with independent media—both public and private—is essential. At the societal level, a democratic political culture that upholds central democratic values and basic human rights is of paramount importance. Therefore, central feedback and self-cleansing mechanisms to safeguard democracies and enhance their resilience can be assured.

In contrast to broad global assertions, such as the aforementioned statement from V-Dem (2022), a more nuanced analysis is required. Initially, I will present a succinct regional overview, addressing both macro- and micro-level perspectives, which already reveal several discrepancies. This will be followed by an in-depth examination of disparate cases within each region, drawing upon the comprehensive chapters authored by regional experts in van Beek (2022). The next step involves a cross-regional analysis of all 16 cases considered, utilizing the configurational method of “Qualitative Comparative Analysis” (QCA) to test various prevalent hypotheses in empirical democratic theory. Through this methodology, detailed case-based information is integrated with broader assessments from V-Dem and other sources (the debate concerning “objective” versus “subjective” measures of democracy and their temporal changes is not the focus here; refer to Little and Meng, 2023; Miller, 2023). This approach facilitates the reduction of individual case complexity and enables the identification of overarching patterns and predominant common factors regarding both democratic backsliding and resilience. The conclusions drawn from this analysis suggest potential remedies in this regard and indicate further significant areas for research.

2 Regional analysis

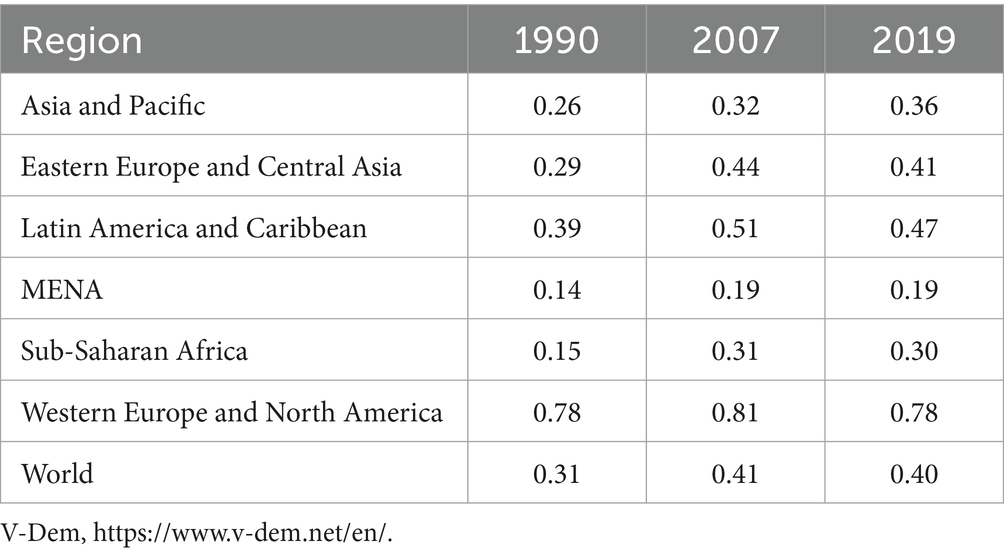

Differentiating by major world regions offers a clearer insight (Table 1):

Significant advancements in liberal democracy were evident across all regions at the macro level from 1990 to 2007, prior to the onset of the “Great Recession.” Subsequent declines are most pronounced in Eastern Europe, Latin America, Western Europe, and the United States, although they remain relatively minimal on a global scale.

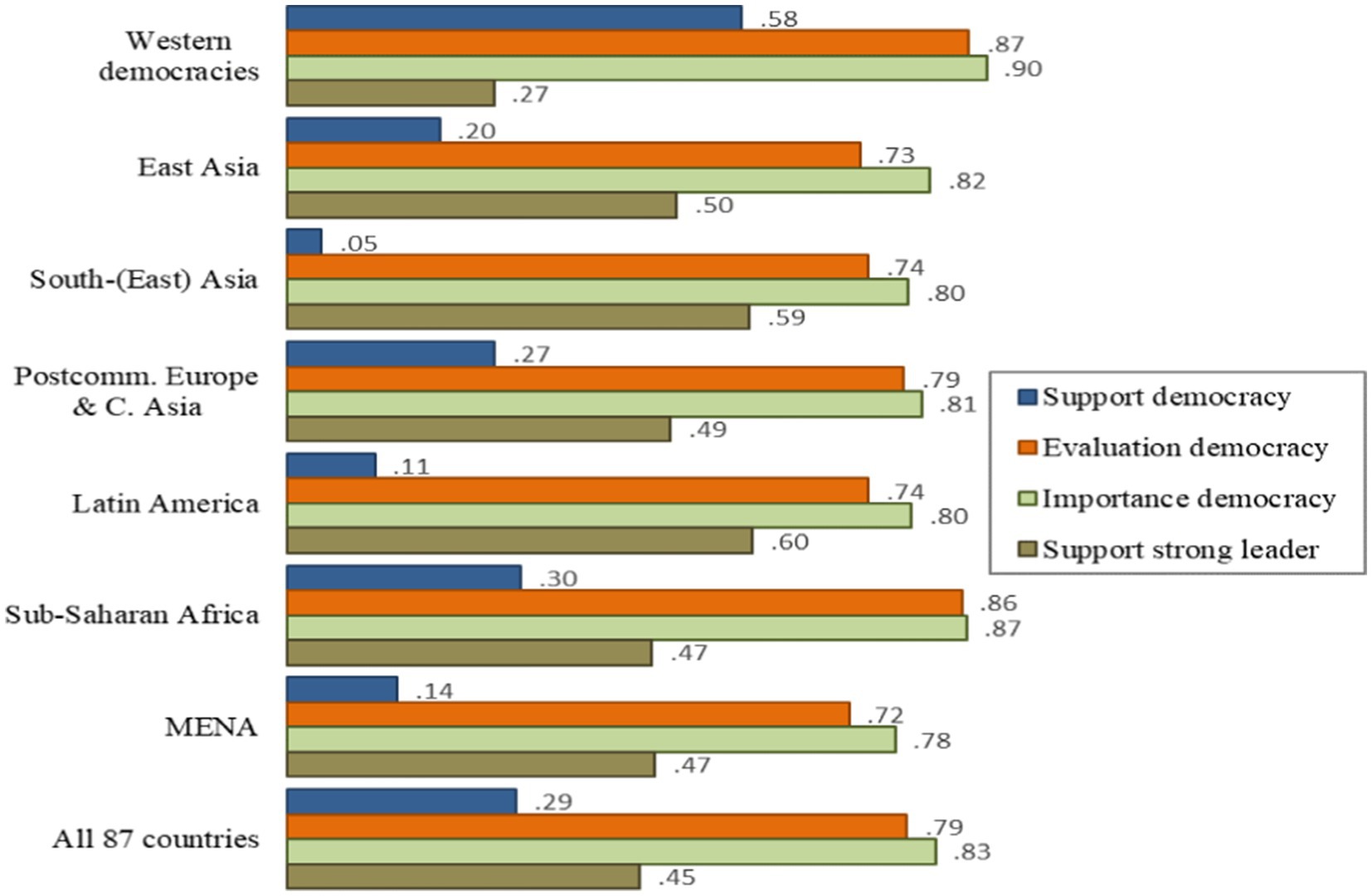

In addition to this comprehensive macro assessment, we examined the perceptions surrounding such developments and the support for democracy at the micro-level by utilizing data from the World Values Surveys (2024) (combining WVS and EVS into IVS) across major world regions. This indicator is rather rigorous, as it relies on independent evaluations of democracy, autocratic governance, or military regimes, and it subtracts the score for authoritarian regimes from the overall democracy score. Figure 1 illustrates these indicators by region for the most recent survey wave, provided by Ursula Hoffmann-Lange, co-author of this project.

Figure 1. Support for democracy, evaluation of democracy, the significance of living in a democracy, and backing for a strong leader who is not required to engage with parliament and elections by world region (wave 2017–2020 only). Source: IVS 1981–2020, 87 countries, equilibrated weight, wave 7.

Consequently, democracy is generally regarded positively in all regions; however, net support for democracy remains strong only in established Western democracies, though there are some regional variations.

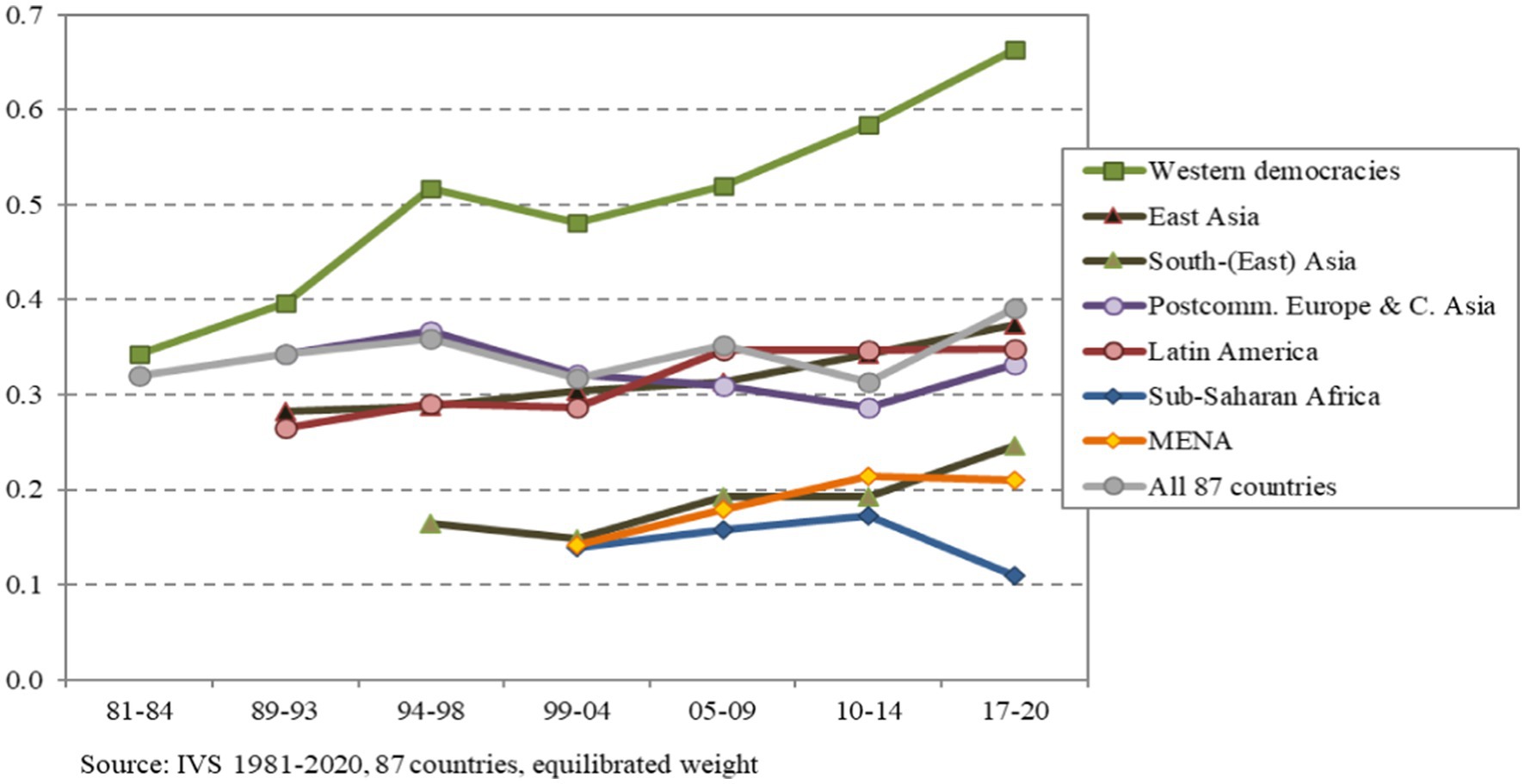

Another critically significant aspect of the underlying cultural conditions, as emphasized by Welzel (2013) and Inglehart (2018), is the enhancement of “emancipative values,” including gender equality and the “free choice of lifestyle,” which encompasses tolerance for divorce, abortion, and homosexuality (Figure 2):

Figure 2. Global support for freedom of choice by region. Source: IVS 1981–2020, 87 countries, equilibrated weight.

Once again, the increase is most pronounced in the established Western democracies; however, a noticeable overall increase is also observable in the countries represented by 87 IVS that have longitudinal data (indicated by the gray line).

3 Case-based accounts

Subsequently, we examined the concepts of resilience and backsliding through selected pairwise and triple case-based comparisons within each region. In each region, this employs a Most Similar Cases Different Outcomes (MSDO) design. The selected pairwise and triple comparisons are as follows (the authors of the respective chapters are indicated in parentheses):

• North America: Canada and the United States (Laurence Whitehead).

• Western Europe: Germany and Italy (Hans-Dieter Klingemann and Ebru Canan Sokullu).

• Post-communist Eastern Europe: Estonia and Poland (Vello Pettai).

• Latin America: Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay (Laurence Whitehead).

• East Asia: South Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines (Dennis L.C. Weng).

• Sub-Saharan Africa: South Africa and Kenya (Cindy Steenekamp and Catherine Musuva).

The democratic case studies of Sweden (conducted by Hans Agné and Tommy Möller) and Turkey (analyzed by Ebru Canan Sokullu), which have experienced significant democratic decline in recent years, were included as a lower threshold. This resulted in a total of 16 cases for the cross-area analysis. In this manner, we accounted for regional historical and geopolitical commonalities while seeking more comprehensive case-based explanations for the differing outcomes.

This analysis elucidated specific strengths and weaknesses associated with democratic resilience. These aspects were partly due to institutional characteristics or particular political practices, while some also stemmed from longstanding political and cultural differences, along with recurring economic and political crises. Examples of the former category include the practical immutability of the electoral college in the United States, which significantly distorts the popular vote (Dahl, 2002), the politically questionable legacy of the Pinochet constitution in Chile, and the frequent mutual institutional obstruction between the two houses of the Italian parliament.

Among the factors contributing to democratic backsliding were institutional changes enacted by governing parties, as well as practices aimed at undermining fair electoral competition. For example, the independence of the judiciary faced considerable pressure in cases such as Poland and Turkey or was influenced by politically motivated appointments. Other questionable political practices included significant levels of party and campaign financing, alongside gerrymandering in the United States, as well as instances of electoral fraud and political corruption in countries such as Kenya and the Philippines. Furthermore, the plurality and political independence of the media were threatened in several instances, particularly in Turkey, Poland, and during Berlusconi’s administration in Italy.

Political parties and party systems similarly displayed several weaknesses, such as the extremely fluid and highly personalized systems in Kenya and the Philippines. In Italy, during the early 1990s, the entire established party system collapsed and was replaced by a diverse array of groups and social movements that transformed into political parties, such as Lega Nord and the Cinque Stelle. The communist legacy in Poland and Estonia had differing impacts on their party systems, resulting in an unstable multi-party system with a persistent role for ex-communists in the former and a relatively stable moderate party system in the latter. A greater degree of political polarization can be observed in many instances, including several of the overall more resilient cases.

On the political-cultural front, strong neopatrimonialism and clientelist practices are evident in countries such as Kenya, the Philippines, and Turkey. Long-standing regional cultural divisions in Germany and Italy continue to influence political matters. Occasionally, as observed in Argentina and Italy, normative support for democracy in principle is accompanied by a significant level of political dissatisfaction regarding the actual institutional features of the regime, government performance, or political incumbents.

Some contrasts also became apparent between relatively resilient political institutions and a low level of democratic support, as observed in South Africa, and high levels of democratic support and participation but weak institutionalization, as in Kenya. This once again raises Eckstein’s (1988) broader question regarding the “congruence” between these two levels.

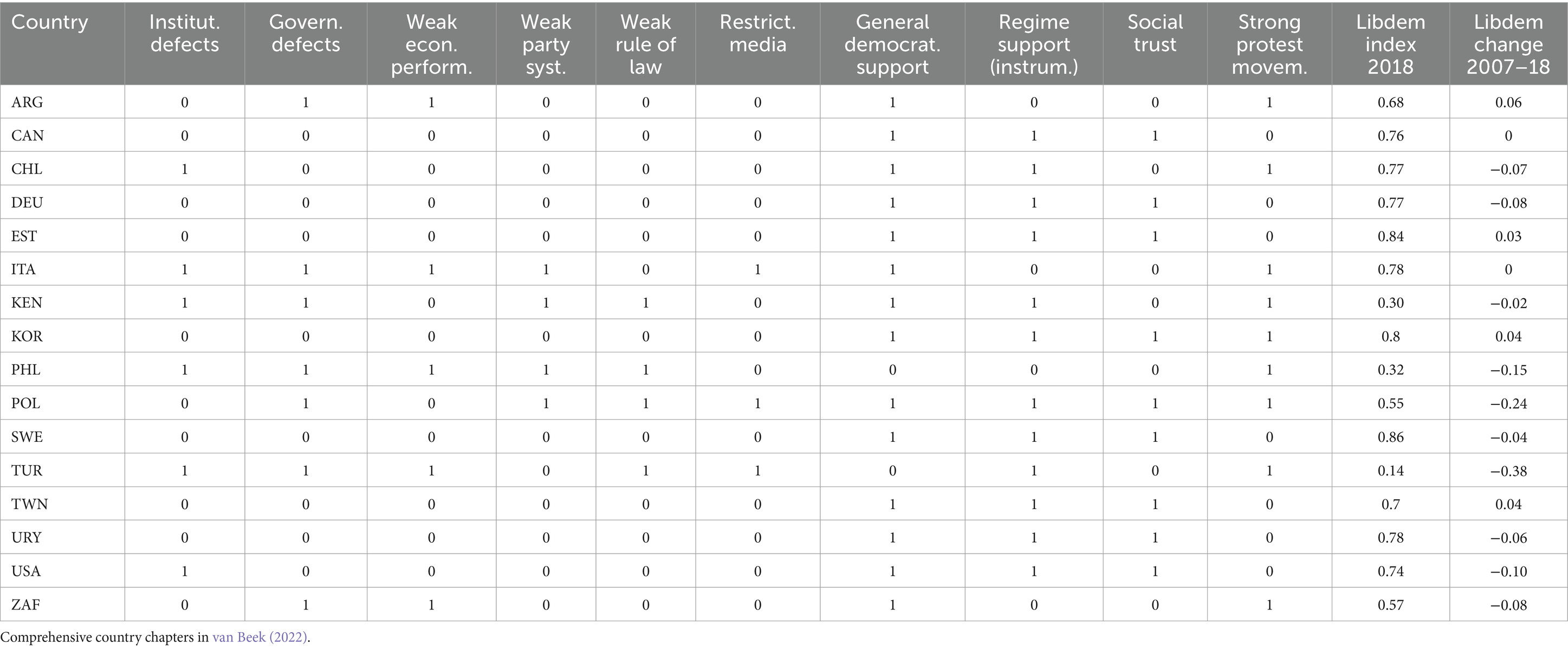

Despite these issues and shortcomings in many of the contrasting cases discussed, deeper political and cultural resilience, along with institutional stability or adaptability, has also been noted. Sweden stands out as the leading example in this regard, while Germany, Taiwan, and Uruguay are also notable cases. Among our examples, the most significant negative shifts in liberal democracy occurred in Turkey, Poland, and the US Improvements were observed in Argentina, Estonia, South Korea, and Taiwan. The overall results are summarized in Table 2:

4 Cross-area analysis

In this context, we examined significant hypotheses of empirical democratic theory using QCA across various regions (for this approach, see Ahram et al., 2018) for our 16 macro-level cases, utilizing data from V-Dem, UNDP, and the World Bank concerning socio-economic changes, rising social inequality, populism, considerable social polarization, gender inequality, good governance, and related issues. This employs a Most Different Cases Same Outcome (MDSO) design (across regions). QCA greatly minimizes complexity through Boolean algebra, resulting in configurational constellations of conditions (Rihoux and Ragin, 2009). This method is particularly beneficial for small to medium numbers of cases where large N statistical analyses are not feasible.

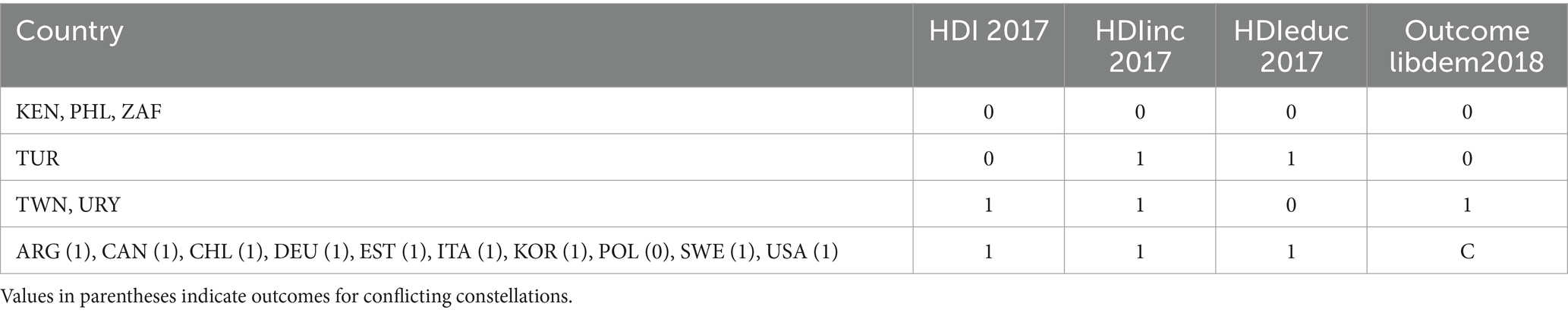

One example is the well-known “Lipset hypothesis” (Lipset, 1959; Przeworski et al., 2000), which examines the effects of higher socio-economic development on democratic growth and stability. Socio-economic development was assessed using the “Human Development Index” (HDI2017) alongside two sub-dimensions: income level (HDIinc2017) and educational attainment (HDUeduc2017) (UNDP, 2020). The cluster analysis of TOSMANA (2019) indicated a threshold value of 0.75, which is suitable for distinguishing between high and low conditions for a “crisp set” analysis. In Boolean algebra, this is represented as a QCA “truth table,” which outlines the conditions of the 16 cases and the corresponding outcome (Table 3).

The Lipset hypothesis is largely confirmed here, both positively and negatively: more developed countries tend to achieve high scores in liberal democracy, with Poland being the only exception, as it is developed yet has a lower score.

QCA can simplify this further to the formula (outcome 1, incorporating logical remainders (R) and contradictions (C)):

1RC: HDI2017 * HDIinc2017 (ARG, CAN, CHL, DEU, EST, KOR, POL, SWE, US, ITA, TWN, URY)

(* signifies “and” in Boolean algebra; upper-case letters denote high values).

This indicates that a combination of a high HDI and high income accounts for the outcome of 11 positive cases, with Poland being the exception.

For the outcome of a low level of democracy, we derived the simplified formula:

0R: hdi2017 (KEN, PHL, ZAF, TUR)

This suggests that all unique negative outcomes, such as those observed in Kenya, the Philippines, South Africa, and Turkey, can be attributed to a low HDI value.

Similarly, we examined broader social-structural and political-cultural conditions, including significant social inequality, neopatrimonialism, clientelism, and social polarization (for a comprehensive discussion of these conditions, please refer to Berg-Schlosser, 2007). In our analysis of the output side of political systems, we further evaluated actual governmental processes and performance. The data provided by the World Bank (2024) regarding “good governance” remains the sole source that offers a more thorough coverage of this dimension. This dataset includes indices pertaining to “government effectiveness” (i.e., the quality of the bureaucracy and public services), “regulatory burden” (i.e., market-unfriendly policies such as price and trade controls), and “graft” (i.e., the utilization of public power for private gain), encompassing various forms of corruption, nepotism, or clientelism, as well as “political stability,” or its converse, the degree of social unrest and violence. Here, graft is classified as “control of corruption” (CCorr) or the lack thereof.

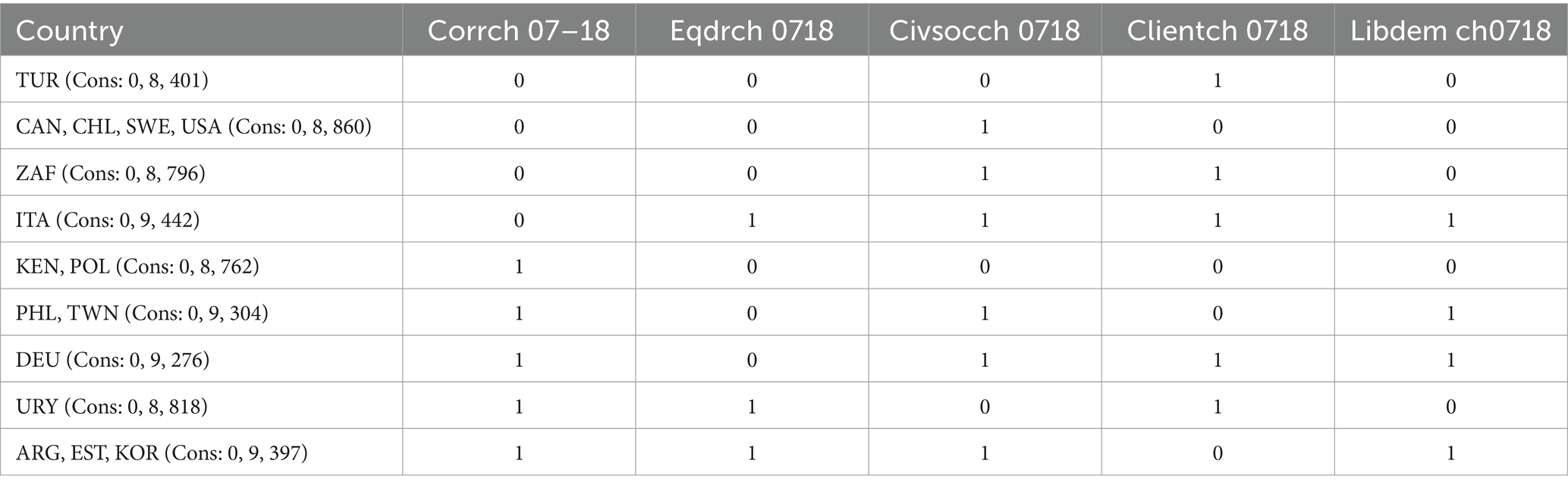

Finally, we examined several potentially positive factors for enhancing democracy, including changes in civil society participation, the core civil society index, the political empowerment of women index, and the egalitarian component index. Current V-Dem data could be utilized for these factors. I am unable to present all the tested conditions and variations of QCA here. The most significant individual conditions for a positive outcome were identified as control of corruption, equitable distribution of resources, a robust civil society, and low clientelism. A combination of the changes in these conditions from 2007 to 2018, employing fuzzy set QCA (i.e., using continuous rather than dichotomized scales), is illustrated in the next truth table (Table 4):

The resulting most reduced formulas are as follows:

Result 1R:

CORRCH07-18 * CIVSOCCH0718 + EQDRCH0718 * CIVSOCCH0718

consistency: 0.8597; coverage: 0.8970

(+ signifies or in Boolean algebra)

This suggests that constructive advancements in civil society, alongside enhanced measures to combat corruption and a fairer allocation of resources, have contributed to the improvement of liberal democracy. This enhancement encompasses nearly 90% of favorable instances, demonstrating a high degree of consistency through a robust subset relationship. Each term represents a sufficient condition, while a strong civil society is regarded as a necessary condition, as it is included within both terms.

Result 0R:

~ CORRCH07-18 + ~ CIVSOCCH0718 + CLIENTCH0718

consistency: 0.8367; coverage: 0.9450

(the symbol ~ indicates a negative value)

Conversely, the backsliding of liberal democracy can be attributed to an escalation of corruption, a deterioration of civil society, or a reinforcement of clientelism, with coverage of the negative outcomes approaching 95%, albeit with a marginally lower consistency.

5 Performance by regime types

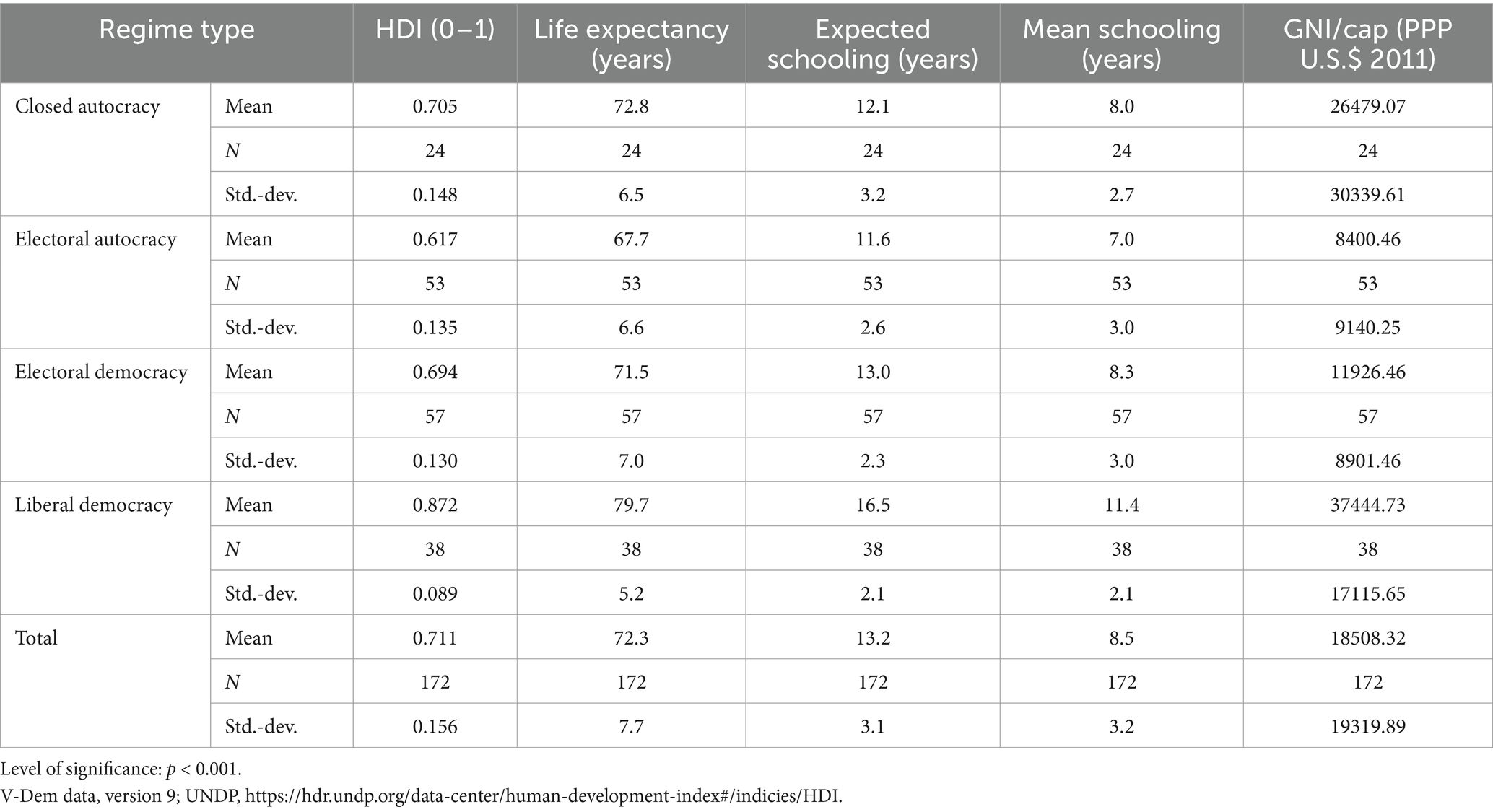

Finally, an evaluation of the socio-economic performance of major regime types and the quality of governance can highlight the strengths of liberal democracies on a global scale (Table 5):

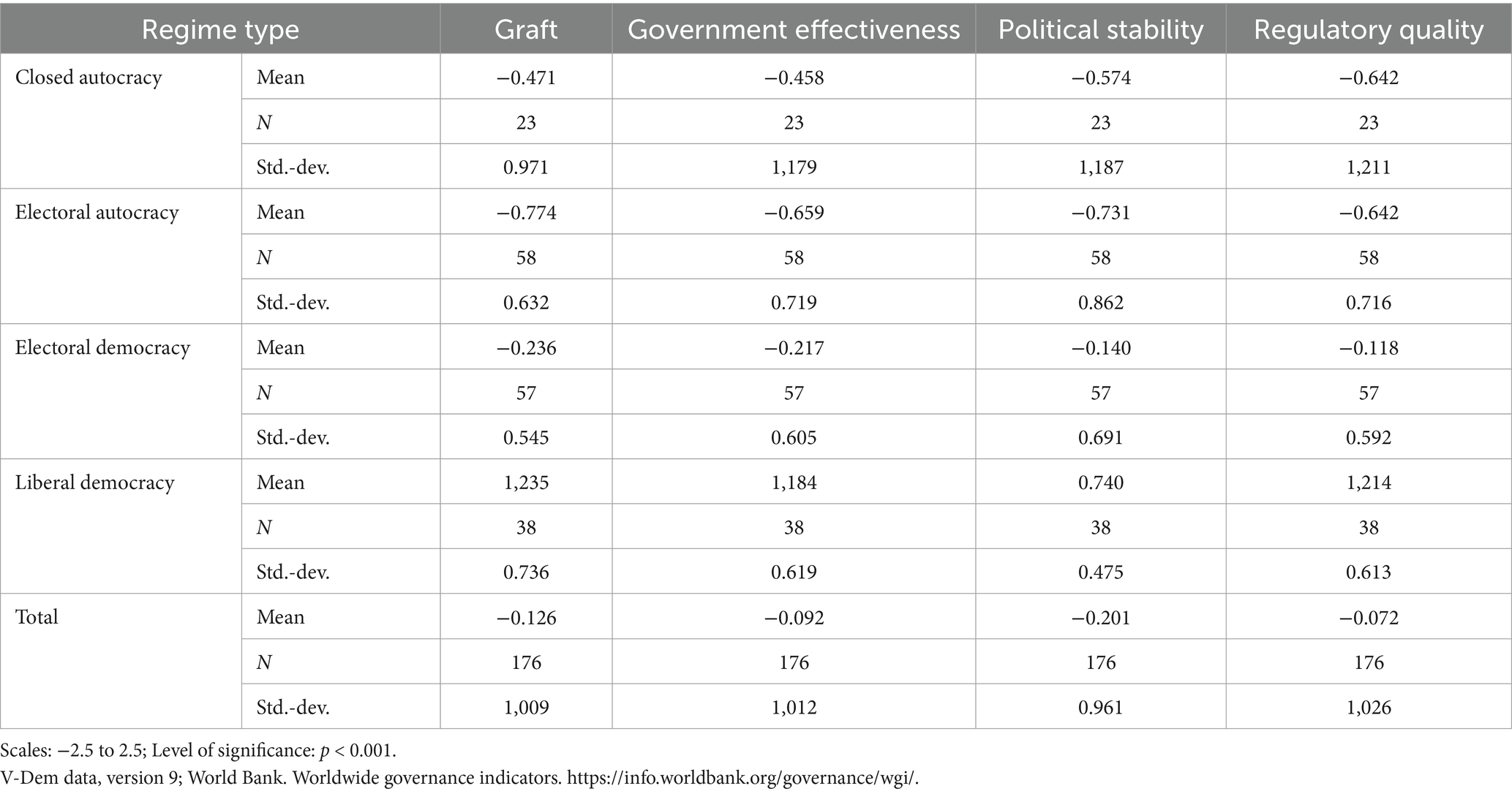

Liberal democracies evidently possess the highest socio-economic scores, followed by closed autocracies in terms of HDI and life expectancy. Electoral democracies rank next, showing a somewhat superior score for education. Electoral autocracies perform the worst (Table 6).

The governance performance is even clearer: liberal democracies achieve positive scores across all indicators, followed by electoral democracies and closed autocracies. Electoral autocracies, yet again, rank the lowest.

6 Conclusion

Our comprehensive findings demonstrate that there is no justification for widespread democratic defeatism. The regional differentiation already emphasizes both negative and positive developments at the macro and micro levels. Minor fluctuations in choice values and an increase in gender equality have been observed. The comparative case analyses have unveiled specific strengths and weaknesses regarding democratic resilience within each region. Subsequently, the cross-regional analysis has identified several key factors that contribute to strengthening liberal democracy. These factors include enhanced control of corruption, a more equitable distribution of resources, and the fortification of civil society. Additionally, this analysis suggests potential remedies in these domains.

Finally, the assessment of socioeconomic performance and governance quality by major regime types on a global scale highlights the strengths of liberal democracies. Indeed, effective governance is a crucial factor contributing to enhanced socio-economic performance. Notably, the failures of populist leaders such as Boris Johnson, Trump, and Bolsonaro support this assertion. In contrast, the “hybrid” electoral autocracies rank the lowest in performance. This also has positive implications for the revitalized competition within the international system. Furthermore, the social upheavals in Belarus, Iran, Myanmar, and elsewhere reveal the vulnerabilities and limitations of repressive regimes.

In summary, a cautious sense of democratic optimism appears warranted (see also Levitsky and Way, 2023). To paraphrase Mark Twain, the claims regarding the “death of democracy” have been grossly exaggerated. Moving forward, it is essential to conduct a more comprehensive analysis of the factors contributing to democratic resilience, as well as specific areas of concern. Similarly, it would be prudent to renew our focus on transitions from authoritarianism, as exemplified by concepts such as “ruptura” or “transición pactada “within the framework established by O’Donnell et al. (1986). The internal divisions between hardliners and softliners across various factions may again prove crucial. In light of the multiple crises facing the contemporary world, the effective functioning of democracies is not the primary challenge; rather, it can serve as part of the solution. Similarly, a rights-based international order and the reinforcement of global institutions can lead us in a beneficial direction.

Author’s note

This article is based on a paper presented at the World Congress of the International Political Science Association (IPSA) in Buenos Aires in July 2023 and has been slightly updated for publication.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: UNDP, https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI, V-Dem https://www.v-dem.net/en/, World Values Surveys, https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp, https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/.

Author contributions

DB-S: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Open Access funding provided by the Open Access Publishing Fund of Philipps-Universität Marburg.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The results of the 2024 General Election, which showed substantial losses for the BJP and demonstrated the well-functioning of democratic procedures and vertical accountability, seem to have vindicated this statement.

References

Ahram, A., Koellner, P., and Sil, R. (Eds.) (2018). Comparative area studies – Methodological Rationales & Cross-Regional Applications. Oxford: OUP.

Berg-Schlosser, D. (2007). Democratization – The state of the art. 2nd Edn. Opladen, Farmington Hills: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Eckstein, H. (1988). A culturalist theory of political change. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 82, 789–804. doi: 10.2307/1962491

Haggard, S., and Kaufman, R. (2021). Backsliding: Democratic regress in the contemporary world. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Levitsky, S., and Way, L. A. (2023). Democracy's surprising resilience. J. Democr. 34, 5–20. doi: 10.1353/jod.2023.a907684

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: economic development and political legitimacy. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 53, 69–105. doi: 10.2307/1951731

Little, A. T., and Meng, A. (2023). “Measuring democratic backsliding” in PS: Political Science & Politics, (Cambridge University Press) 57, 149–161.

Merkel, W., and Lührmann, A. (2021). Resilience of democracies: responses to illiberal and authoritarian challenges. Democratization 28, 869–884. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2021.1928081

Miller, M. (2023). “How the objective approach fails in democracies” in PS: Political Science & Politics, (Cambridge University Press) 57, 202–207.

O’Donnell, G., Schmitter, P., and Whitehead, L. (Eds.) (1986). Transitions from authoritarian rule: Prospects for democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and development. Cambridge: CUP.

TOSMANA. (2019). Available at: www.tosmana.net

UNDP. (2020). Available at: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI.

V-Dem. (2022). Available at: https://www.v-dem.net/en/

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising: Human empowerment and the quest for emancipation. Cambridge: CUP.

World Bank. (2024). Worldwide governance indicators. Available at: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/

World Values Surveys. (2024). Available at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp

Keywords: democratic resilience, democratic backsliding, political support, emancipative values, good governance, system competition

Citation: Berg-Schlosser D (2025) Democratic resilience or retreat? A cross-area analysis. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1447925. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1447925

Edited by:

Oliver Fernando Hidalgo, University of Passau, GermanyReviewed by:

Sorina Soare, University of Florence, ItalyBarkhad Mohamoud Kaariye, Ardaa Research Institute, Ethiopia

Copyright © 2025 Berg-Schlosser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dirk Berg-Schlosser, YmVyZ3NjaGxAc3RhZmYudW5pLW1hcmJ1cmcuZGU=

Dirk Berg-Schlosser

Dirk Berg-Schlosser