- Faculty of Social and Educational Scienes, University of Passau, Passau, Germany

This article argues in favour of broadening the classical paradigm of democracy that historically emerged in the West. Without disregarding the undiminished significance of the idea of liberal democracy and its deep commitment to universal human rights, the necessity of a new accentuation of the concept of democracy is accepted in view of the observable democratic processes in non-Western societies. This should help to avoid both the blind spots of Eurocentrism and the misperception of countries as democracies that are merely masking their authoritarian or despotic character. The result is a theory of popular sovereignty that seeks to grasp and combine Western and non-Western conceptions of democracy in a balanced way and is based on a genealogical and comparative perspective of the history of political ideas in the global North and South. In a second step, the theory is then tested using a few selected examples (Confucian democracy, Islamic democracy, African democracy).

1 Introduction

This paper intends to present an innovative theory of Non-Western Democracy based on a genealogic and comparative perspective on the history of political ideas, which includes the potential to demonstrate the differences and similarities between Western and Non-Western democracies simultaneously. Since international and global democratisation processes are mostly no longer assessed as a simple assimilation to patterns of democracy originating in the Western world, but as the authentic emergence of an autochthonous type of democracy,1 it is important to reconceptualise the idea of democracy in a way that allows both to retain its universal requirements, such as human rights, and to avoid the undeniable blind spots of a Eurocentric perspective.2 Such a balanced point of view is not only necessary to avoid a highly ideologized self-image of the West and to become receptive to the democratic self-descriptions of diverse “cultures.” If Western and non-Western ideas of democracy are no longer bundled under any meta-perspective and the concept of non-Western democracy endeavours to manage without reference to the Western realm of experience, there is a danger that the term “democracy” will finally fall victim to arbitrariness.3 Despite all the differences between non-Western and Western idiosyncrasies, the term “democratisation” should mean nothing but the convergence towards a “shared” idea of political life.

Proceeding from this assumption, the main objective of this article is to understand democracy as a framework for constant struggles between contradictory and therefore opposing principles such as freedom vs. equality, popular sovereignty vs. representation, quality vs. quantity as a basic guideline for democratic decision-making, plurality vs. social harmony, individual vs. collective claims and finally universality vs. particularity. Looking at the comparative history of political thought, it will be argued that the idea of democracy consists of significant tensions, paradoxes and aporias and is therefore able to subsume very contrary ideas and social realities under its semantic field. In this vein, it is emphasised that the apparent polarity between Western and non-Western concepts of democracy is a consistent outcome of the historical and contemporary discourse on democracy. Moreover, since any Western or non-Western democratic system that is not merely a mislabelling exercise must have high affinities with all the conflicting norms mentioned above, the coexistence of the following disparate features can be derived as relevant indicators of all democracies: Market economy and welfare state institutions; the influence of lobby groups and the principle of “one person, one vote”; the legislative power of parliaments and public debates, elections or referendums; majority rule and the rule of law; the pluralism of opinions or lifestyles and a collective identity of the people; civil rights and the duty of solidarity; and last but not least, the paradox that every democracy is both similar and dissimilar to other democracies because it reflects both universal principles and a necessarily particular will of the people.4

Therefore, some empirical examples can be used to show and illustrate that non-Western democracies do not require the translation of democratic principles into a distinctively non-Western template or model of democracy (Youngs, 2015, p. 143). Instead, the general impression that non-Western societies want less individualism, more traditional social values, more economic equality and more consensual and participatory politics than Western ones is merely interpreted as different priorities within the same antinomian framework of democracy. In terms of the history of democratic theory, on the one hand, this approach confirms Walter Bryce Gallie’s (1956) classic assertion that democracy—like justice or the arts—is one of those “essentially contested concepts” that lack clear standards of both universally accepted definition and consistent discursive practice.5 On the other hand, democracy is at least identified as a concept with clear contours at its boundaries, which means that it can be shown what all controversies within Western and non-Western democracies are about. The democratic antinomies approach therefore opposes both a transcultural minimal concept of democracy and Christopher Lord’s (2004), notion (analagous to above: Walter Bryce Gallie’s (1956) classical assertion that the concept of democracy is only “boundary contested” by allowing differences and deviations at its edges and peripheries. This means that the widespread search for a unifying core of democracy is turned into its opposite at this point. Instead, the focus is placed on the overarching framework of democratic order(s).

2 The theory of democratic antinomies

2.1 Democracy with adjectives

The application of the concept of antinomy expresses—more emphatically than the rather unspecific “paradox”6 that is often associated with democracy—that the semantic attributions of meaning that can be traced in the context of the history of concepts, ideas and theories of democracy form a network of irresolvable tensions and contradictions. The latter characterise democracy as a concept that brings together the incompatible. Beyond the general controversial nature of political concepts (Göhler et al., 2006), opposing but largely equivalent normative claims are thus extended into the concept of democracy and can consequently be subsumed under it in a plausible manner.7

In order to identify such antinomies of democracy, it makes sense to start with some linguistic analyses. The outlined ambiguity and controversial nature of democracy has led to an attempt in academic jargon to semantically concretise and qualify the range of social realities that are commonly connotated with this concept. This is usually done with the help of certain adjectives, which paradoxically say more about the root concept of democracy than contributing to terminological clarity.8 Such adjectives can be categorised into three groups: Firstly, semantic constructions that are used to overtly reduce the democratic content of an observed political system, such as “guarded,” “guided,” “restrictive,” “embedded” or “military-dominated” democracy, which stand for a mixture of authoritarian and democratic elements. The first group of adjectives traditionally provokes the harshest criticism because, on the one hand, regimes in which democratic forms such as civil rights, free and periodic elections, a multi-party system, separation of powers etc. are insufficiently guaranteed are nevertheless labelled as “democracies” and, on the other hand, because quite a few people suspect Western standards behind the semantics that reduce the criteria of democracy. A second group of adjectives, on the other hand, aims to increase the degree of precision by pointing out particular institutions of a political system that is indisputably categorised as a democracy. These include, for example, parliamentary, (semi-)presidential, federal or social democracy.9 Adjectives that mark the spatial characteristics of the concept can also be assigned to this second category, i.e., the distinction between European, Asian, African or Latin American varieties of democracy or intercultural, global and cosmopolitan approaches to democracy.10

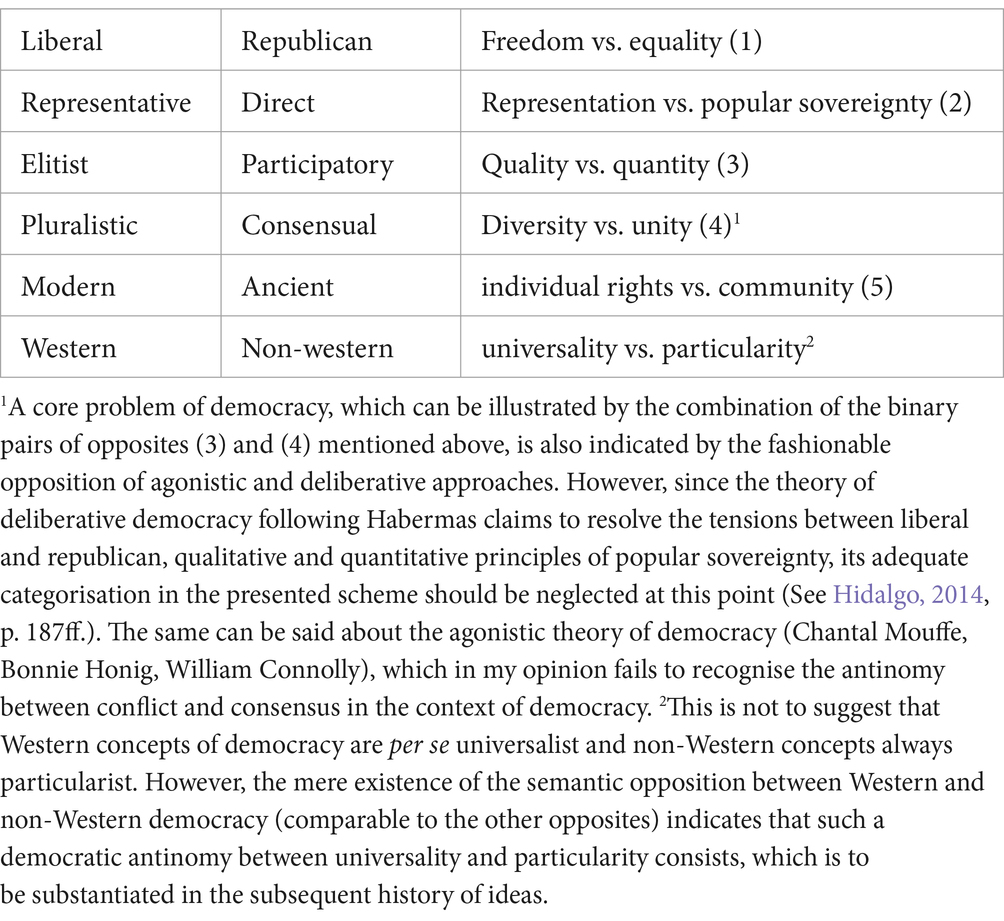

The third category, which is decisive for the detection of democratic antinomies, is formed by those adjectives designating characteristics of democracy that are neither clearly reductive nor intend a—normatively neutral—institutional or spatial precision. This is the case whenever the content of a relevant statement or speech act is itself the subject of a controversy, which at the same time indicates moments of tension and points of contention within the concept of democracy. This impression is reinforced by the fact that adjectives of the third category can usually be arranged along binary oppositions. Without being able or willing to claim completeness, it seems evident that there are at least six pairs of opposites in this regard:

• Liberal vs. republican democracy (1)

• Representative vs. direct democracy (2)

• Elitist11 vs. participatory democracy (3)

• Pluralistic vs. consensual democracy12 (4)

• Modern vs. ancient democracy (5)

• Western vs. non-Western democracy (6)

All of these contrasting semantic constructions indicate aspects of democracy that are generally perceived as legitimate but are nevertheless controversial, both in terms of their normative foundations and the different institutional forms they take. The six pairs of adjectives mentioned above each address something that clearly “belongs” to democracy and therefore deserves to be emphasised, without one of these characteristics becoming a “unique selling point” of democracy at the expense of its antonym. For example, as Frank Cunningham (2002, p. 24–72) has shown, the liberal focus on freedom, individual rights, the rule of law, the separation of powers, and the market economy must by no means absorb the republican heritage of equality, the general will of the people, political participation, civic virtues and a focus on the common good if democracy as a whole is to be categorised as “intact” or “complete” (1). The same applies to the contrasting coexistence between elements of representative (e.g., elections, parliamentarism, indirect legislation, free mandate, proportionality) and direct democracy (popular sovereignty, initiative and consultative procedures such as referendums, petitions and veto rights) in a democratic system (2) or the need for (deliberative) procedures of participation and inclusion on the one hand and the need of democracy for professional competence, expertise and limits to the power of people on the other (3). A similar tension also concerns the observation that democracies are equally challenged to integrate the existing plurality of values, interests and lifestyles and to apply the majority principle for the purpose of generally binding decisions, as well as to evoke a sense of collective identity and social homogeneity (4).

These examples should already demonstrate that in the institutional settings of democratic decision-making, references to each pole of the opposing six pairs of democracy outlined above can always be identified. The relevant emphases can, however, be very different, as the pronounced direct democratic institutions, e.g., in Switzerland, Ireland, Denmark, Italy, Australia or New Zealand demonstrate in contrast to the restrained practices in Germany, Israel, India and Japan or at least at federal level in the USA and Canada (Schiller, 2002; Matsusaka, 2020). The same could be said about the strong liberal political culture in Anglo-Saxon countries and the republican tradition in the French-speaking world.

The spectrum can be extended if we focus on the temporal and spatial discrepancies that illuminate both equally contrasting and equally legitimate sides of democracy as well. In this respect, we can refer to the special case between ancient and modern democracy, since in terms of conceptual history, the attribute “democracy” can hardly be taken away from the political institutions in ancient Athens, although these institutions characterising a strictly community-based political association including slavery, ostracism and the exclusion of women, workers and peasants were strictly incommensurable with modern political concepts of individual rights, emancipation and privacy (5) (Finley, 2019). In addition, the existing distinction between Western and non-Western concepts of democracy (6) should at least be seen as an initial indication that there is a further tension within the concept of democracy, which is to be interpreted as an antinomy: because opposing characteristics of democracy can in turn be understood as equally legitimate, as long as they do apparently not reduce the democratic character of a political society as such.

2.2 Six democratic antinomies—a first overview

The hexagon of opposing ideas of democracy outlined above does not yet provide evidence of antinomic assignments of meaning. In order to prove why the contradictory basic principles of democracy corresponding to the adjectives of the third category can actually be considered equally legitimate, a comprehensive examination of their history of ideas and concepts is necessary. For what we categorise as legitimate today did not simply arise spontaneously. Instead, we look back on a long development of political thought in which the concept of democracy amalgamated with corresponding legitimising ciphers, which resulted in the competition between the aforementioned types of democracy. In this complex historical and intellectual process, democracy has shown itself to be capable of successively bringing to one concept everything that had previously crystallised as “legitimate” in various political discourses. We can recognise this as soon as we look at the most prominent characteristic of each of the subtypes of democracy identified adjectivally, which is summarised schematically in the following Table 1.

With the help of a genealogical reconstruction of the discourse on democracy, it can be shown in this context that the historical debate on the concept, from its beginnings in the Attic polis to the present day, has been about the (impossible) endeavour to bring together those irreconcilable contradictions, i.e., those antinomies, in one and the same term. At this point, a few sparing references must suffice.13

1. Even in antiquity, freedom and equality formed the normative basis of democracy. The insoluble contradiction that exists between the two principles, insofar as (uncontrolled) freedom always produces inequality, while equality can only be achieved through (state) restrictions on freedom, could of course be ignored there, since women, peasants, workers and slaves were excluded from the public space and thus made the time-consuming political participation of citizens in democratic decision-making socio-economically possible. However, even the formal legal link between liberal and egalitarian principles in the modern age could not resolve the fundamental contradiction between freedom and the authority to rule, and liberals and socialists, right-wingers and left-wingers argue endlessly about how far freedom and/or equality may or must extend in political, economic, emancipatory, real or formal terms. Collisions are unavoidable in everyday political life and can only be concealed if one operates with a too narrow concept of equality (which ignores economic aspects) or freedom (which excludes the positive-political dimension of autonomy).

2. The antinomy between popular sovereignty and representation in democracy is closely interwoven with the opposition between freedom and equality and was particularly emphasised by authors such as Hobbes and Rousseau, who decidedly took one side or the other. Hobbes, however, had at least to admit popular sovereignty as a theoretical option in his contractualism, while Rousseau’s practice-oriented writings such as the Lettres de la Montagne or the draft constitution for Poland make certain concessions to the unavoidable representative organisation of legislative power in larger territorial states. Even the later explicit connection between these two evidently contradictory principles in the wake of “Taming the Leviathan” (Locke, Montesquieu, Kant) and the successive development of the modern concept of representative democracy (Spinoza, Federalists, Sieyès, Paine) is by no means to be regarded as a successful theoretical mediation or elimination of the contradiction, but primarily as a conceptual concealment. The resulting pragmatic adaptation of the (originally direct) concept of democracy to the constraints of the representative organisation of power in the modern age finally outweighed all remaining theoretical inconsistencies and can even be found since then in contrary minimal concepts of direct or representative democracy (e.g., Joseph Schumpeter vs. Benjamin Barber).

3. The contradiction between the principles of quality and quantity, i.e., expert and elite rule as well as popular and majority rule, once fuelled the early fundamental criticism of democracy by Plato, Pseudo-Xenophon and others. With Aristotle and the summation theory14 he launched, efforts were soon made to achieve a balance between the political participation of the people/majority and the need for political results independent of it, but the aporia itself could not be resolved. No matter how the people, the masses or the majority participate in political decision-making in democratic systems—through elections, direct democratic institutions and practices or even public discourse in the sense of Habermas’ deliberative democracy—there is always a clear need on the other side not to blindly follow the majority vote but to limit the power of the people to secure a certain output, be it through constitutional restrictions, elements of the mixed constitution or the idea of the free mandate, be it—in extreme cases—even through party bans or emergency decrees. The fact that there are cases in which (majoritarian) democracy must be protected from itself has unfortunately been confirmed too often in history.

4. The next democratic antinomy between unity and plurality, homogeneity and heterogeneity, consensus and conflict implies that the phenomena of social differentiation, pluralism and competition have become obligatory for every modern democracy, but that in return it is nevertheless dependent on the existence of a lien social, a collectively shared identity. This point of contention in democracy was also discussed early on between Plato and Aristotle, before the issue came to a head with Machiavelli. His conflict-orientated model of the republic in the Discorsi broke with the political-theological ideas of harmony in the Middle Age, without neglecting the importance of the forces of social cohesion. However, the institutional containment of conflicts, which Machiavelli had already proposed and which at least presupposes a consensus on the decision-making and regulatory mechanisms to be applied, should not be confused with a cancellation of the conflict as such. The controversy about how much unity a democratic society needs and how much plurality and conflict it can tolerate has therefore remained an evergreen of democratic theory—with intellectual highlights during the constitutional controversies at the time of the Weimar Republic between Carl Schmitt, Hans Kelsen and Herrmann Heller,15 later with Ernst Fraenkel or Jacob L. Talmon or also in the context of the communitarianism controversy in the United States.

5. The unavoidable rivalry between the claims of the individual and the political community, which was modelled in the theory of the social contract in the course of secular processes in the Christian world as well as along the emerging question of the legitimacy of power provoking a harsh ideological opposition between individualism and collectivism in the 18th and 19th centuries, also fulfils the criteria of a semantic antinomy. Only the two principles of individualism and collectivism together constitute democracy and must coexist as competing types of claim, even though—as has been shown in the debate about Kenneth Arrow’s impossibility theorem or the limits of the “invisible hand” revealed by Adam Smith’s game theory16—no clear conclusions can be drawn from individual preferences about the common good (which therefore remains amorphous). In this context, democracy can only refuse to place itself entirely on the side of either the individual or the community, even if in single decisions the favouring of one pole or of the other becomes usually evident.

6. Finally, reference should be made at this point to the fact that democracy is necessarily guided by universal claims such as human rights, but in its concrete political organisation based on endogenous social development processes, the sovereignty of culturally diverse peoples and the freedom of conscience of the members of parliament, it will and must always remain particular. This in turn provokes moments of tension and aporias that have been ruthlessly exposed by the critical analyses and deconstructions of postmodernism. This sixth and (for the time being) last antinomy of democracy is summarised by Ernesto Laclau, who criticised the radically particularistic strategies of some (post-structuralist) approaches as a hermetic retreat into one’s own cultural identity, even to the point of “segregationism” and “self-apartheid,” in order to simultaneously speak out against a universalistic resolution of all tensions and differences between (democratic) cultures in a utopian consensus (Laclau, 1996, p. 32). This leads him to an aporetic and antinomian manifesto of democracy:

“Totality is impossible, and, at the same time, is required by the particular: in that sense, it is present in the particular as that which is absent, as a constitutive lack which constantly forces the particular to be more than itself, to assume a universal role which can only be precarious and unsutured. It is because of this that we can have democratic politics: a succession of finite and particular identities which attempt to assume universal tasks surpassing them; but that, as a result, are never able to entirely conceal the distance between task and identity, and can always be substituted by alternative groups. Incompletion and provisionality belong to the essence of democracy.” (Laclau, 1996, p. 15f.)

Since the concept of democracy appears to be compatible with all the contradictory ideas and principles mentioned above, or rather: incorporated those contradictions, it was able to establish itself in the course of history as a discourse framework and venue for the resulting political conflicts. Conversely, this discourse framework helps to identify the neuralgic points of democracy. Insofar as the opposites are antinomies, i.e., equally well-founded principles, they also designate almost equivalent poles in normative terms. In political debates, these can be articulated in a one-sided or polemical manner without the opposing opinion being labelled “anti-democratic.” Convincing arguments can be found for all single poles to the detriment of the opposing pole; however, the positions that can be derived from this within the framework of democracy must recognise the parallel legitimacy of the opposing opinion—more equality instead of more freedom, expansion of direct democratic or representative institutions etc. On the other hand, the democratic discourse framework is abandoned when an attempt is made to prevent the antinomies of democracy, to resolve the contradiction once and for all or even—in the Hegelian sense—to abolish (or “sublate”) it in the form of a synthesis. The authoritarian or even totalitarian degeneration of democracy, as described by the classics from Aristotle to Talmon and Lefort and as can also be seen in the radicalised positions of Plato, Hobbes, Rousseau, Hegel, Marx or Carl Schmitt, is closely linked to this phenomenon—too much of an intrinsically legitimate democratic side can be responsible for its degeneration. Moreover, this explains the well-known self-destruction mechanism from which democracy cannot escape without betraying its own principles and which goes far beyond the case of the “liquidation” of democracy via the ballot box. In addition to this excess of quantity while neglecting the qualitative, e.g., constitutionally defined limits of democracy, the de facto elimination of the majority principle in the sense of an “militant” democracy can also undermine the government of the people. Alternatively, democracy may fail of its own accord as a result of too much or too little social homogeneity or respect for cultural plurality and diversity, individual demands or community obligations, freedom or equality. What democracy is able to achieve in political practice, on the other hand, is a fragile, always provisional balance between its contradictory principles, a peaceful coexistence of antinomic poles, whereby the constantly necessary rearrangement with the changing conditions of its environment and the balancing of dynamic claims are the main characteristics of any democracy.

3 Non-western patterns of democracy in the mirror of an antinomian framework

The identified antinomies of democracy have far-reaching implications for the topic of non-Western democracy. Since democracy can generally be assumed to be a political concept or a discursive framework that is constituted by irresolvable contradictions, Western and non-Western approaches to democracy can be understood as generally equal attempts to balance the antinomic poles of democracy in their own way through practical arrangements. This means that, with the help of the democratic antinomies reflected in the history of ideas, the scope in which non-Western democratic systems—in contrast to their Western counterparts—can be realised, must be defined, as well as the limits that must be accepted by democracies of all stripes in order to avoid mislabelling.

This assessment results not least from the fact that the tension between non-Western and Western ideas of democracy can itself be seen as an indication or even a logical consequence of the sixth democratic antinomy between universality and partiality. In fact, the first five antinomies flow into the sixth and final antinomy, since the five initially identified areas of tension both provide generalisable criteria for democracy and form concrete particularities that are characterised by their deviation from these criteria. Thus, the antinomic poles of equality, representation, quantity, social homogeneity and individuality are intersubjectively linked to the universal similarity and comparability of all democracies, while the poles of freedom, popular sovereignty, quality, plurality and community make it possible to explain why every democracy is at the same time a unique, particular entity.

In sum, democracies in their theoretical and empirical diversity exhibit the paradox peculiarity of being simultaneously congruent and incongruent: They share the antinomic characteristics of democracy, as a result of which each democracy turns out to be different from all others vice versa. The fundamental contradiction that arises between the universal and particular character of democracy also points to the unavoidable “self-exaggeration” inherent in every democratic project in theory and practice.17

It follows from this that the opposing sides of democracy are to be interpreted against the background of the semantic differentiability between Western and non-Western conceptions of democracy to the effect that the democratic antinomies are simply combined here into divergent convolutions. In meta-theoretical terms, the contrast between non-Western and Western ideas of democracy can therefore be hypostatised as an inherent symptom of the historical discourse on democracy, as the latter is condemned to permanently break through its own claim to universality due to the inevitably particular formations of democracy. The debate on the legitimacy of non-Western democracy is just one particular example of this.

Insofar as the contrast between Western and non-Western democracies is thus part of and an expression of democratic antinomies, the latter can function as a measure of the authenticity and quality of Western and non-Western democracies. After all, the problem with such standards has always been that they have been suspected of inadmissibly absolutising historically contingent ideas generated in the West. Although the democratic antinomies are also reconstructed from the intellectual history of the West, they can reject the idea that there is any definition of democracy at all on which there is consensus—in the West or outside of it—without democracy therefore falling prey to arbitrariness. Moreover, as mentioned above, the antinomies approach regards Western and non-Western democracies as fundamentally equal by assuming that they each seek practical arrangements between the antinomic poles in their own way. In addition, the democratic antinomies reflect why every (Western or non-Western) universal claim is necessarily broken by particular forms of democracy, so that the mere identification of “Western” ideas of democracy conversely demands the coexistence of equivalent “non-Western” ideas of democracy.

Specifically, the democratic antinomies can be operationalised to evaluate non-Western (and Western) democratic ideas and practices by asking whether the antinomies disappear in the respective (nominally democratic) arrangements, i.e., whether only one pole of the antithesis is respected and the other is absorbed or not. On the one hand, such an approach is able to establish an empirically divergent role of individual rights, community obligations, social homogeneity or direct democratic institutions in non-Western versus Western democracies, without having to deny the quality of democracy to such systems on this basis. A boundary is reached when the divergence leads to a form of cancellation (or sublation in the sense of Hegel), i.e., when the legitimacy of individual claims, pluralism etc. is called into question as such.

4 Three examples

The following section uses several examples to demonstrate how the democratic antinomies approach allows for a fair and adequate assessment of non-Western models of democracy. En passant, using the methods of the history of political ideas and of comparative political theory, it is shown that non-Western discourses on democracy as well oscillate around the six basic antinomies being identified in the sections above. A Eurocentric point of view should thus be avoidable.

4.1 Democracy in the Muslim world

For the legitimacy of Islamic ideas of democracy, the democratic antinomies approach includes, for example, that the social integration of religious beliefs and truth claims can form a kind of pre-political basis of society, but must neither predetermine democratic legitimisation procedures (and thus undermine popular sovereignty) nor stand in the way of respectful coexistence with non-Muslim beliefs and lifestyles in the sense of the fourth antinomy (or their political representation). Furthermore, the community obligation must not be emphasised in such a way that the claim of the community becomes so absolute that any individual right is reduced to absurdity (fifth antinomy).

These partial aspects may in principle be immediately obvious, just like the long-known insight that election victories and majorities (including those of Islamist parties) are among the necessary, but by no means sufficient components of democracy in the sense of the quantity principle (third antinomy); however, only the overarching perspective of democratic antinomies provides a suitable framework for developing examination criteria for the “quality” of democracy at all relevant levels and for understanding which components in democracy as a whole must interlock. It is also important to note that the theory of democratic antinomies yields the (measurable) requirement for the actors in real democratic systems to pursue political goals only within a certain scope. That is to say, the commitment to the realpolitik priority of one pole (and specific political decisions are always based on such a priority, for example when taxes are levied, competences are distributed or laws are passed) can never be absolute, but only temporary. On the one hand, this means that such precedence must remain at least theoretically reversible and, on the other hand, must not make decisions in favour of the opposite pole impossible. The latter would be the case, for example, if democracy were reduced to introducing an Islamist state by majority decree on the basis of fixed sources of revelation and then declaring it irredeemable, as the former leader of the Islamist Nahda party (which has won several elections in Tunisia after the Arab spring), Rachid al-Ghannouchi, proposed in the 1990s.18 Fixed constitutional norms have to generate scope for antinomies, not cut it. Conversely, a general ban on religious parties (as happened for instance in Libya 2012) is therefore no less precarious in terms of democratic theory.

Against the background of the application level of democratic antinomies, a differentiated assessment of other Islamic ideas of democracy beyond a Eurocentric perspective would also be possible. A concept of democracy that presupposes the social role of Islam and government control by Islamic scholars (while reducing democracy to a mere technique of rulership), as in the case of the radical Islamist and opponent of secularisation Al-Qaradawi (2009), could easily be classified as incompatible with the normative implications of the democratic antinomies (especially the third and fourth one). In contrast, a comparison with the much more moderate position of Sachedina (2006), which distinguishes between the principles of (democratic) guidance and (non-democratic) governance of Islam in the public sphere, shows that even non-secular views of popular sovereignty in Islam can resort to formulas that respect the antinomies of democracy and are similar to the political role of religion in democratic (civil) society, which is also being claimed more strongly in the West today. The well-known attempts in political practice, such as the constitution of an Islamic democracy briefly introduced by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt after the Arab Spring, can also be fairly assessed by the standard of democratic antinomies.

With regard to the complex relationship between democracy and Islam, the wide range of democratic ideas that appear acceptable against the background of the theory of democratic antinomies is illustrated by the fact that both a very conservative approach such as that of Ramadan (2004) and a left-wing political approach such as that of Esack (2006) are equally covered by it. The decisive factor in each case is the extent to which the either very strong (Ramadan) or very weak (Esack) political role of Islam in democracy retains respect for the opposing principles of democracy in its own way. In case of doubt, the fourth antinomy between unity and diversity plays a key role here, as it allows us to judge whether the arrangement between religious and secular actors that is necessary for any democracy has been successful or not.19 In respect of the relation between democracy and Islam, the fourth antinomy of democracy also makes it evident that the undemocratic cancellation of one of the two antinomic poles can run in both directions: On the one hand, a (homogeneous) Islamic democracy that discriminates against non-Muslims and/or excludes them from the political sphere can be seen as a violation of the principle of democratic pluralism. Conversely, however, the problem can also lie in a lack of social homogeneity and collective identity caused by a form of antidemocratic plurality which, in principle, does not even recognise the collectively binding rules of democracy (cf. Collier, 2009). In the contemporary Muslim world, such an antidemocratic plurality is not only observed in countries such as Iraq or Syria, where the opposition between Sunnis, Shiites and other religious groups obviously prevents sufficient social unity. In Indonesia of the present, a similar “nondemocratic plurality” (Aspinall and Mietzner, 2019)—which has also been called “clientelistic democracy” (Fossati et al., 2020)—is reactivated by a social cleavage separating pluralists from Islamists. This became clear as the incumbent Joko Widodo won the 2019 presidential election with the support of various religious minorities as well as traditionalist Muslims, while his authoritarian-populist challenger Prabowo Subianto was backed by groups advocating a more prominent role for Islam in public life. As a result of that socio-religious polarisation, the (pluralistic) Indonesian government implemented a couple of illiberal measures in order to contain the populist-Islamist alliance, but not without undermining important democratic achievements of the last decade as, e.g., guarantees of freedom, individual rights and the rule of law (antinomies one, three and five).

4.2 Confucian democracy

Another example of applying the theory of democratic antinomies is the approach of Daniel Bell, whose book Beyond Liberal Democracy (2006)—representing many contemporary critics of the West and emphasising the peculiarities and advantages of the tradition of political theory in East Asia—stylised Confucian ideas of democracy, human rights and market economy as a legitimate alternative to the model of Western liberal democracy. The problem here is not so much the rejection of Western democracy as a universal standard and the consideration of the specific East Asian (value) context, in which democracy can and must be realised there in an independent way that is in tension with the West. Instead, Bell’s demand that Western and Asian political theory should learn from each other is even undoubtedly to be supported. However, the difficulty lies rather in the fact that it is not transparent what, apart from all the differences, is the common democratic element between Western and Confucian versions of the government of the people. Instead of forming a tense coexistence of universal and particular components of democracy, Bell’s non-Western and Western democracy stand in direct opposition to each other, in that the East Asian version of popular sovereignty is held up against an explicitly non-liberal, anti-individualistic set of values (antinomies 2, 3, and 5). The boundaries between non-liberal and illiberal (Zakaria, 2003) are blurred here, which is why the East Asian form of democracy hypothesised by Bell inevitably has a democracy-reducing character in the sense of the adjectives of the first category. This is also reflected in the fact that Bell praises some of the advantages of the East Asian world independently of its affinity to democracy. For example, he writes that “some less-than-democratic political systems in the region can also be defended on the grounds that the help to secure the interests of minority groups—and that democratisation can be detrimental to those interests,” which leads him to the general question: “Should we rule out of court the possibility that nondemocratic forms of government can better protect the legitimate interests of minority groups for now and the foreseeable future” (Bell, 2006, p. 185)? In contrast to this, it must be emphasised that serious deficits of “democracies” in the protection of minorities can only be expected as soon as they abolish the antinomies between quantity and quality (antinomy 3) as well as social homogeneity and plurality (antinomy 4), thereby directly forfeiting the character of democracy.20 In addition, Bell obviously uses an alternative political theory discourse that does not ask about the legitimacies, advantages and disadvantages of non-Western democracies, but about a general alternative to (Western) democracy.21 For this reason, he is not satisfied in his statements with contrasting emphases of East Asian democracy (which would have to be evaluated with the help of the antinomic discourse framework), but instead spreads his approach into a dichotomy between Western and non-Western political systems. In doing so, he misses the antinomic “both and” of democracy and transforms the debate into a dichotomous “either or” that lies outside of democratic discourse.22 Finally, Bell reduces the cultural context of the East Asian region in numerous places to the notorious Confucian values, which seem to determine the political formations in East Asia as a uniform normative pre-political basis.23 The actual diversity of the East Asian region is thereby missed (contrary to the fourth democratic antinomy).

As an alternative to Bell’s too one-sided perspective, a more differentiated discourse on the possible compatibility between Confucian and democratic values was launched by Li (1997), He (2010), and Kim (2014). In this context, particularly Li stands for the proposal not to conceal the remaining tensions between Confucian and democratic principles, but to understand democracy as a possibly “independent value system” in China and other East Asian societies. Translated into the logic of democratic antinomies, this means not simply negating the apparently anti-Confucian values of democracy (equality, majority rule, plurality, individualism) by referring to the opposing Confucian principles (hierarchy, expertise, harmony and community) (= antinomies 1, 3, 4, and 5), but allowing them to coexist peacefully (or independently) within a Confucian and democratic society—similar to what ultimately happens in Western, non-Confucian societies, except that there Confucian values are recognised within democracy itself. Kim’s approach, on the other hand, is rather pragmatic but very similar in terms of the results. As consolidated democracies already exist in Taiwan, South Korea and, to a lesser extent, Hong Kong,24 the question is no longer whether Confucianism and democracy are compatible or not, but only which form of democracy is suitable for the East Asian context. And here, according to Kim (2014, p. 247), “the particular mode of Confucian democracy” that attempts to allow the (contradictory) principles of both logics—Confucian and democratic—to coexist, is far more efficient than endeavouring to push through a liberal democracy against all Confucian traditions. In other words, Kim generally mediates between the universal and particular sides of democracy (antinomy 6). In more detail, he favours the (free consensus and the expertise of the) deliberative model of democracy against its (agonistic) conflict model (ibid.: 132), without denying the “fact of pluralism” and therefore the necessity to accommodate “multiple moral goods” (ibid.: 50, 126) and also without to use “meritocratic elitism” of Confucianism as an argument against all democratic participation and equality (ibid.: 85ff.) (see antinomies 1, 3, and 4). And not least, in order to best endure the (antinomic) tensions of democracy, Kim argues for not merely concentrating on the institutional makeup of government (ibid.: 17), but for realising Confucian democracy primarily as a civil society in the sense of Habermas (ibid.: 60ff., 80ff.) with Confucianism as a form of public political culture. Therefore, without explicitly naming the antinomian framework of democracy, Kim’s idea of Confucian democracy moves all too obviously within its contours.

4.3 Democracy in African contexts

As a final example, we will refer to a theoretical discourse concerning democracy which was once started by the Ghanaian political philosopher Kwasi Wiredu and continues in Africa to this day. As part of a greater project he termed “conceptual decolonisation,” Wiredu tried to establish the concept of African “Consensus Democracy” as an alternative to the Western liberal model. In his essay Democracy and Consensus in African Traditional Politics: A Plea for a Non-Party Polity, he argued that already the Ashanti Empire in Ghana that lasted from 1701 until 1901 was a “consensual democracy”:

“It was a democracy because government was by the consent, and subject to the control, of the people as expressed through the representatives. It was consensual because, at least, as a rule, that consent was negotiated on the principle of consensus (By contrast, the majoritarian system might be said to be, in principle, based on consent without consensus).” (Wiredu, 1995, p. 58f.)

According to Wiredu’s view, the adversarial nature of democratic practices in Western societies along cleavages and partisan political lines is not appropriate to African politics. Therefore, modern African democracies should better continue the tradition of consensual democracy instead of moving closer to the (neo-)liberal multi-party system of the West, which, following Wiredu, has a disintegrating effect on the African continent in particular, not least because it exacerbates the struggles between rich and poor people. Thus, for Wiredu, the reanimation of the African tradition of consensual democracy is necessary to emancipate postcolonial/independent African countries from the epistemological and political hegemony of Western powers and to use the aspects of African tribal culture that were appropriate to be embedded in modern African politics in order to improve the self-confidence of African peoples.

In his response to Wiredu, the Nigerian political thinker Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze (1997) criticised that Wiredu’s approach overestimates consensus as a sort of panacea without sufficiently reflecting that the concept could be instrumentalised by dictators and authoritarian parties. Rather precisely, Eze raises three objections against Wiredu’s account of consensual democracy. First, he questioned the source of legitimising political authority in the Ashanti system as well as in consensual democracy as such. For Eze, it was not the wisdom of the chief/the eldest member of the political council to formulate reasonable and persuasive arguments but his sacred aura and the religious belief of the people that were crucial factors in attaining consensus. Second, there is no (rock bottom) identity of interests as Wiredu suggests but a plurality of divergent and competing interests in a society necessarily leading to antagonistic politics. And third, democracy according to Eze (1997, p. 320) may not be confused with an authoritarian and/or religious attainment of consensus but means first of all a social framework which mediates social conflicts and political struggles that arise as a result of the “competitive nature of individuated identities and desires.” And further:

“A democracy’s raison d’être is the legitimation—and ‘management’—of this always already competitive (i.e., inherently political) condition of relativized desires. In this sense, ‘consensus’ or ‘unanimity’ of substantive decisions cannot be the ultimate goal of democracy, but only one of its moments.” (ibid.)

This is not the place to judge whether Wiredu, Eze and/or their successors are right in their views on democracy or not. Instead, it is sufficient to say that the relevant discourse, which could only be briefly recapitulated here, occurs entirely within the framework of democratic antinomies, just like the previously discussed concepts of Islamic or Confucian democracy. Hence, neither Wiredu denies the permanent existence of conflict (which is not simply absorbed by consensus and possible compromises or modi vivendi), nor Eze does ignore that consensus is an important component of democracy in order to mediate the endless political struggle of interests. At a second glance, their arguments even supplement each other and therefore confirm together the antinomian framework of democracy. Moreover, all participants in the relevant political discourse25 apparently set different priorities and emphasise, e.g., the quality of (deliberative) decision making over the quantitative principle of majority rule, consensus over conflict, unity over diversity, collective over individual rights (Wiredu) or vice versa (Eze), without basically neglecting the legitimacy of each opposing position (similar to what happens today in Western debates on deliberative and agonistic democracies). Thus, as long as neither the principle of consensus nor the principle of conflict is made absolute, i.e., the antinomies of democracy are not cancelled out, the solution found in each approach is actually of secondary importance. Proceeding from this, the history of political thought and the methods of comparative political theory are able to demonstrate that also the African debate on democracy26 is much closer to the Western perspective than a popular prejudice asserts, although both discourses must be interpreted independently and cannot be decided by external cultural traditions and actors. However, which view will ultimately prevail, is not a question of political theory, but of political practice.

5 Conclusion

The fact that the development of democracies in the international and global space is by no means to be understood as a copy of Western idiosyncrasies, but rather as particular approaches to a universal idea (Diamond, 2008, p. 17ff.), can now be considered a commonplace of the debate that has launched the term “Non-Western Democracy” for several decades. Behind this is not only the insistence on the consideration of non-Western perspectives in order to avoid Eurocentrism, but also the need to clarify what the “universal” of the democratic idea consists of.

What is obvious here, is the endeavour to identify a democratic core capable of consensus, which simultaneously allows for flexible configurations and divergences at its edges and peripheries.27 In this regard, Tilly (2007), for example, has distilled the overcoming of categorical inequality, the introduction of confidence-building structures and decision-making procedures as well as a functioning control of powers as common characteristics of a long-term, global transition movement towards democracy.28 Today, however, the (in-)direct self-government of the people, consisting of free and equal citizens, is to be regarded as the (universal) “minimal definition” of democracy.

Although the approach of democratic antinomies obviously goes far beyond such minimal concepts, it nonetheless has important points of contact. It is noticeable, for example, that the working definition mentioned above can be easily reconstructed along the lines of the first (freedom and equality) and second antinomy (direct self-government of the people as an illustration of the tension between representation and popular sovereignty) and can thus be used heuristically. The only difference between the two approaches that should be emphasised is that the concept of antinomies fundamentally rejects a “definition” of democracy in the narrow sense of the word29 and instead endeavours to establish a dynamic framework for discourse. In its contours, democracy can be realised in a largely open and flexible way, but it finds normative orientation precisely through the underlying non-decidability of democratic contradictions and controversial issues: in that, on the one hand, divergent emphases are possible with regard to the institutional and social design of every democracy and, on the other hand, the non-resolution of the relevant controversial issues also calls for the coexistence of opposing principles.30 Against the background of the contrast between Western and non-Western democracy, the independence and comparability of the observed political systems is thus preserved and a standard can be established for determining when it is (still) a democracy and when it is not. A narrower, focussed examination of Western and non-Western democracies is possible at any time by using - as in the working definition - only the first two antinomies or other antinomies as partial aspects of the discourse on democratic theory in order to gain at least a preliminary perspective on the necessary components of democracy. All in all, however, the approach presented here is resolutely concerned with the endeavour of being able to depict the complexity of democracy solely along its at least six basic antinomies.

The indispensable identification of the “universal” of democracy with regard to the comparison of its Western and non-Western varieties is consequently not carried out on the basis of the democratic antinomies in the form of a condensation to a specific core, but rather—as outlined in section 4—as an extension of the insoluble contradictions between equality and freedom, representation and popular sovereignty, quantity and quality, unity and plurality, individual and collective claims to a permanent tension between universal characteristics and particular peculiarities. In this respect the universal principles of democracy include above all equal rights of citizens, the representative organisation of power on the basis of the majority principle, a collective identity common to all democracies and, finally, a special link between democracy and the idea of human rights. In return, the peculiarity and uniqueness of every “real” democracy follows clearly from the freedom to create own democratic institutions, the sovereignty of each people, the regionally, culturally and constitutionally different understanding of quality standards and decision-making limits, plurality as a “value” of democracy per se and, finally, the specific character and identity of every (democratic) community.

One problem that cannot be negated, however, is that the risk of blind spots and prejudices in the genealogically reconstructed antinomic discourse framework of democracy is by no means excluded. The overview of six basic democratic antinomies presented in section 2.2 predominantly reflects the view of democracy trained on the basis of the Western-influenced history of political ideas and thus does not offer an objective standard for a completely impartial assessment of non-Western democracy. However, the inevitable incompleteness, imponderables and provisional nature of the democratic antinomian approach do not shake its theoretical and practical relevance in toto, but merely place its scope of application under reserve. In this respect, the concept remains open to future modifications, additions and relativisations, which would preferably come from the field of non-Western political theory or comparative political theory (Dallmayr, 2010b).

In a final analysis of the latter, however, the conceptual advantage of the antinomic understanding of democracy becomes transparent once again, as it allows numerous aspects (that would otherwise be discussed largely unconnected) to be integrated in a systematic manner. In this respect, it is noticeable that Dallmayr’s sketch of a democracy beyond the West or a democracy on a global scale uses very similar formulations to summarise the contradictory nature of the subject. For example, the Alternative Visions and “paths into the Global Village” (Dallmayr, 1998), which take into account post-colonial theories as well as the “non-identity” of political ideas from Africa, Asia and Latin America,31 reflect nothing other than the sixth antinomy between universality and particularity, just as the simultaneity of a global and plural democracy (Dallmayr, 2001)32 or the coexistence between a “cosmopolis” and the necessary “dialogue” between unequal partners do (Dallmayr, 2013). On the other hand, the need for an “integral pluralism” that combines holism and difference and is therefore opposed to the idea of “culture wars” (Dallmayr, 2010c) points to the fourth antinomy of democracy. Moreover, the talk of parallel “tensions and convergences”—in this case between Asian and Western ideas of human rights (Dallmayr, 2001, p. 51ff.)—also suggests an apparent proximity in terms of content to the antinomic understanding of the relationship between Western and non-Western democracy and the decisive contrast between universality and particularity. Finally, the strict demand not to apply a (Western-influenced) minimum consensus for the evaluation of (non-Western) democracies (Dallmayr, 2010a, p. 169ff.) and the plea for the multiple “modes of democracy” (ibid.: 155ff.) coincide with the scope that arises as a result of the antinomic interpretation of democracy for its non-Western variants. However, as Dallmayr refrains from analysing democracy as such in all its contradictions, but—in the wake of Derrida’s démocratie à vénir—insists on the (allegedly) apophatic, i.e., “unspeakable” of democracy,33 the complementary tension between Western and non-Western approaches remains an isolated problem in terms of democratic theory. In contrast, this tension becomes transparent as a characteristic of democracy itself as soon as the antinomy between universality/globality and particularity/plurality becomes tangible as its integral component. As a result, not only the analytical precision in grasping the Western/non-Western contrast as a pre-programmed phenomenon of the democratic movement increases, but also the understanding of why Western and non-Western approaches can in principle claim normative equality regardless of their genesis. According to the antinomies of democracy, Western and non-Western perspectives can only constitute democracy together/in coexistence, as the constitutive contrast between universality and particularity cannot be conceived of in any other way from a global perspective. For the debate on non-Western democracy, this means that—unlike in the past—it should not be located in the periphery, but at the centre of democratic theory.

Author contributions

OH: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The author acknowledges support by the Open Access Publication Fund of University Library Passau.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^See, e.g., Manglapus (1987), Sen (1999, 2006), Dallmayr (2001), Diamond (2008, p. 11–38), and Youngs (2015). Even the latest developments in the theory of modernisation, unlike its classical representatives such as David Lerner, Seymour Martin Lipset or Walt Rostow, no longer assume a quasi-automatic democratic transformation of countries once they have reached the socio-economic and technical standards of the West. Instead, either the interrelationship between economic development and the democratic distribution of power and resources (cf. Vanhanen, 1997, 2003; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005) or an intercultural (or multiple) approach to modernity (cf. Zapf, 1994; Eisenstadt, 2003) are at the centre of their considerations.

2. ^In this respect, the argument presented here should not fall behind post-structuralist and post-colonial critiques of Western universal claims, as formulated, e.g., by Foucault, Derrida, Edward Said or Gayatri Spivak.

3. ^Such arbitrariness is to be feared within the Western discourse on democracy alone, as it seems to have been clear since the obvious self-contradiction of “representative democracy” that the concept of “popular sovereignty” should not be taken too literally. For a comprehensive genealogy of the paradoxical democratic “discovery” of representation, which leads from Rousseau via Sieyès, Kant and Condorcet to Thomas Paine, see Urbinati, 2006.

4. ^The aforementioned contradictory features of democracy can also be used to create a set of methodological guidelines for applying the antinomy framework to empirical research on real-world cases.

5. ^In sum, Gallie pointed out seven criteria in order to signify essentially contested concepts: Appraisiveness, internal complexity, diverse describability, openness, reciprocal recognition, multiple exemplars, and progressive competition (cf. Collier et al., 2006).

6. ^For some classic democratic “paradoxes”, see, e.g., Wollheim, 1962; Mouffe, 2000; Vorländer, 2003, p. 26.

7. ^This not only excludes the problem of logical antinomies, as discussed above all by Bertrand Russell; the semantic antinomies relevant to the field of political theory and social science alone are also not explained with the rigour that would allow the term to indicate an intersubjective demonstration of equivalences between statements and counter-statements. For the necessary distinction from the Kantian concept of antinomy from Critique of Pure Reason, see Hidalgo, 2014, p. 29ff. For a political science adaptation of the concept of antinomy comparable to the argumentation proposed here, using the example of “democratic peace”, see Müller, 2004.

8. ^On the possible “overstretching” of an adjectivally differentiated concept of democracy, see Collier and Levitsky, 1997.

9. ^Overlaps between the first and second group of adjectives occur whenever the institutions emphasised in this way are at the same time in an obvious tension with democracy, such as “one-party” or “military-dominated” democracy. The same applies when, as in the case of electoral democracy, the emphasis on one necessary characteristic of democracy implicitly indicates the absence of other necessary characteristics. Whether this also includes the concept of media democracy, for example, is debatable.

10. ^With regard to the last-mentioned spatial extensions of the concept, there are also overlaps with the first group of adjectives, since an adjective from the second group could indicate a political transformation that runs counter to the other characteristics of democracy. For an analogous criticism of transnational notions of democracy, see, e.g., Dingwerth, 2007; Grugel and Piper, 2007. Apart from that, when non-European democracies are considered, it could be the political impact of a speech act, that such a non-European (or non-Western) democracy is normatively inferior or superior to the European or Western models. However, such an impact could not be derived from the adjective itself.

11. ^The terms “representative” and “elitist” do indeed suggest a meaning that reduces democracy, but current usage reflects the fact that representative institutions and/or political-social elites are now generally regarded as compatible with the government of the people or with popular sovereignty.

12. ^The distinction of majority and consensus democracies (Lijphart, 1999) or competitive and consociational democracies (Lehmbruch, 1993) are due to a very similar contrast within democracy.

13. ^For a more detailed description of the six basic antinomies outlined below, see Hidalgo, 2014, Ch. 3.

14. ^See Politiká 1281a42–b8.

15. ^The antinomic character of the problem is best expressed by Heller (1971, p. 428) when he wrote: “Social homogeneity can never mean the abolition of the necessarily antagonistic social structure.”

16. ^For this, see Nash (1951).

17. ^For this problem, see again the theoretical approach of Laclau (1996) as well as Castoriadis (2010). The self-exaggeration of democracy into a universal approach, which is to be maintained despite all inevitable particularities, forms—if you like—the positive flipside of its immanent self-destruction mechanism. The fact that democracy is constituted by principles that can ultimately lead to its decline gives it the credibility to be “more” than just one particular political system among others.

18. ^See al-Ghannouchi’s book Al-Hurriyat al-àmma fi d-daula al-islamiya (Beirut 1993).

19. ^The figure of twin tolerations (Stepan, 2001) can be seen as a complementary standard to the fourth antinomy of democracy for assessing religious accommodation in a democratic system.

20. ^This fact is ignored by Bell’s comments on the “Implications for Outside Prodemocracy Forces” (Bell, 2006, p. 202ff.). It is not without reason that the (antinomic) constitutional reality in Western democracies presents itself beyond an anti-minority concentration on popular sovereignty, the majority principle and homogeneity and also shows affinities to the corresponding counter-principles: balanced representation, quality and plurality (antinomies 2, 3, and 4).

21. ^This is also complained by Dallmayr (2010a, p. 205ff.), who criticises Bell’s culturally sensitive approach “that the move is not just beyond ‘liberal democracy’ but beyond democracy tout court” (ibid.: 208).

22. ^On the serious difference between a dichotomy, which in Carl Schmitt’s sense suggests a decision in favour of one of two opposing sides, and an antinomy, which allows opposing positions to exist side by side precisely because no decision in favour of one of the two sides is possible, see Hidalgo, 2014, p. 34f.

23. ^Bell (2006, p. 52) himself states that the assumption of a cultural essence in Asia that is fundamentally divergent from the West is doubtful: “There are no distinctly Asian values, and anything that goes by the name of ‘Asian values’ tends to refer to values that are either narrower […] or broader […] than the stated terms of reference.” In this respect, he certainly endeavours to “describe” the influence of the traditional Confucian and legalistic political culture in East Asia with the necessary sensitivity for the different collective identities to be found there (ibid.: 259, 61, 308). However, several chapters of his book identify Confucianism beyond a historically multi-layered and complex discourse tradition with concrete statements by Confucius or Mencius (ibid.: 31, 234–35) and simply equate meritocracy and elitism with “Confucian societies” (ibid.: 154f., 167). The question of the extent to which the relevant social models are authoritarian and thus by no means necessarily correspond to the East Asian value framework is also avoided.

24. ^Kim’s assessment dates from 2014, so it is not disputed here that democracy in Hong Kong has come to an end, at the latest since the promulgation of the National Security Law by Beijing authorities in 2020, which denied the legitimacy of individual claims and pluralism. Nevertheless, Hong Kong can be cited in retrospect as empirical evidence that the realisation of democracy in Confucian Asian societies is possible in principle.

25. ^For a comprehensive discussion of Wiredu’s and Eze’s arguments, see, e.g., Matolino, 2009; Inusah, 2021.

26. ^Further significant contributions to the indigenous democratic values from Africa have been launched (e.g., by Moshi and Osman, 2008; Fayemi, 2009; Sarsar and Adekunle, 2012).

27. ^In this respect, it is worth recalling Christopher Lord’s approach of understanding democracy as merely a “boundary contested concept.”

28. ^Admittedly, Tilly has the rule of law rather than democracy in mind.

29. ^The ultimate impossibility of defining democracy also explains why the democratic position per se can never be identified from a portfolio of different positions in a particular controversy. As democracy is constituted along antinomies, no categorical but always plural programmes can be derived from its concept, which is why a convincing, overall democratic position always depends on the context.

30. ^Insofar as the fourth antinomy between unity and plurality, consensus and conflict “belongs” to democracy, democracy in this context is not to be understood as one-sidedly agonistic, i.e., as a kind of synonym for a certain type of dispute.

31. ^For reasons of space, it was unfortunately not possible to introduce approaches to democracy from Latin America in this paper, although the relevant debate is currently very lively in this subcontinent (see, e.g., Dussel, 2006; Van Cott, 2009; Whitehead, 2010; Dominguez and Shifter, 2013; Masiello, 2018).

32. ^See also in particular the tension between global governance and cultural diversity (Dallmayr, 2001, p. 35ff.).

33. ^For a relevant discussion of Derrida’s apophatic démocratie à venir, see Dallmayr, 2001, p. 147ff.

References

Al-Qaradawi, Y. (2009). “Islam and democracy” in Princeton readings of Islamic thought: Texts and contexts from al-Banna to bin Laden. eds. R. Euben and M. Q. Zaman (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP), 230–245.

Aspinall, E., and Mietzner, M. (2019). Southeast Asia’s troubling elections: nondemocratic pluralism in Indonesia. J. Democr. 30, 104–118. doi: 10.1353/jod.2019.0055

Bell, D. (2006). Beyond Liberal democracy: Political thinking for an East Asian context. Princeton/Oxford: Princeton UP.

Collier, P. (2009). War, guns, and votes: Democracy in dangerous places. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Collier, D., Hidalgo, F. D., and Maciuceanu, A. O. (2006). Essentially contested concepts: debates and applications. J. Polit. Ideol. 11, 211–246. doi: 10.1080/13569310600923782

Collier, D., and Levitsky, S. (1997). Democracy with adjectives: conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Polit. 49, 430–451. doi: 10.1353/wp.1997.0009

Dallmayr, F. (1998). Alternative visions: Paths in the Global Village. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Dallmayr, F. (2001). Achieving our world: Toward a global and plural democracy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Dallmayr, F. (2010b). Comparative political theory: An introduction. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Diamond, L. (2008). The spirit of democracy: The struggle to build free societies throughout the world. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Dingwerth, K. (2007). The new transnationalism: Transnational governance and democratic legitimacy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dominguez, J., and Shifter, M. (2013). Constructing democratic governance in Latin America. 4th Edn. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP.

Esack, F. (2006). “Contemporary democracy and the human rights project for Muslim societies. Challenges for the progressive Muslim intellectual” in Contemporary Islam. Dynamic, not static. ed. A. A. Said (London: Routledge), 117–128.

Eze, E. C. (1997). “Democracy or consensus? Response to Wiredu” in Postcolonial African philosophy. A critical reader. ed. E. C. Eze (Oxford: Oxford: Blackwell), 313–323.

Fayemi, A. K. (2009). Towards an African theory of democracy. Thought Prac. J. Philos. Assoc. Kenya 1, 101–126. doi: 10.4314/RRIAS.V25I1.44929

Fossati, D., Aspinall, E., Muhtadi, B., and Warburton, E. (2020). Ideological representation in clientelistic democracies: the Indonesian case. Elect. Stud. 63, 102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2019.102111

Gallie, W. B. (1956). Essentially contested concepts. Proc. Aristot. Soc. 56, 167–198. doi: 10.1093/aristotelian/56.1.167

Göhler, G., Iser, M., and Kerner, I. (2006). Politische Theorie. 22 umkämpfte Begriffe zur Einführung. Wiesbaden: VS.

He, B. (2010). Four models of the relationship between Confucianism and democracy. J. Chin. Philos. 37, 18–33. doi: 10.1163/15406253-03701003

Inglehart, R., and Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Inusah, H. (2021). Wiredu and Eze on consensual democracy and the question of consensual rationality. S. Afr. J. Philos. 40, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/02580136.2020.1871567

Lehmbruch, G. (1993). Consociational democracy and corporatism in Switzerland. Publius J. Feder. 23, 43–60.

Li, C. (1997). Confucian value and democratic value. J. Value Inq. 31, 183–193. doi: 10.1023/A:1004260324239

Lijphart, A. (1999). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. London: Yale UP.

Manglapus, R. S. (1987). Will of the people: Original democracy in non-Western societies. New York, NY: Greenwood.

Masiello, F. R. (2018). Senses of democracy. Perception, Politics, and Culture in Latin America. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Matolino, B. (2009). A response to Eze’s critique of Wiredu’s consensual democracy. S. Afr. J. Philos. 28, 34–42. doi: 10.4314/sajpem.v28i1.42904

Matsusaka, J. G. (2020). Let the people rule: How direct democracy can meet the populist challenge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP.

Moshi, L., and Osman, A. A. (2008). Democracy and culture. An African perspective. London: Adonis & Abbey.

Müller, H. (2004). The antinomy of democratic peace. Int. Politics 41, 494–520. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800089

Sachedina, A. (2006). “The role of Islam in the Public Square: guidance or governance” in Islamic democratic discourse: Theory, debates, and philosophical perspectives. ed. M. Khan (Lanham: Lexington), 173–191.

Sarsar, S., and Adekunle, J. O. (2012). Democracy in Africa: Political changes and challenges. Durham: Carolina AP.

Sen, A. (2006). Democracy Isn’t ‘Western. Wall Street J. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB114317114522207183 (Accessed April 5, 2024).

Stepan, A. (2001). “The World’s religious systems and democracy. Crafting the twin tolerations” in Arguing comparative politics (Oxford: Oxford UP), 213–254.

Urbinati, N. (2006). Representative democracy: Principles and genealogy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Whitehead, L. (2010). Alternative models of democracy in Latin America. Brown J. World Affairs 17, 75–87.

Wiredu, K. (1995). Democracy and consensus in African traditional politics. A Plea for a non-party polity. Centennial Rev. 39, 53–64.

Wollheim, Richard (1962): A paradox in the theory of democracy, in: Laslett, P., and Runciman, W. G. (eds.): Essays in philosophy, politics and society. 71–87. New York, NY: Blackwell.

Youngs, R. (2015). Exploring “non-Western democracy”. J. Democr. 26, 140–154. doi: 10.1353/jod.2015.0062

Zakaria, F. (2003). The future of freedom: Illiberal democracy at home and abroad. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Keywords: democracy, non-western history of political thought, confucianism, Muslim world, Africa, antinomies, political theory

Citation: Hidalgo OF (2025) The antinomian framework of Western and non-Western democracies—from theory to application. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1420252. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1420252

Edited by:

Clinton Sarker Bennett, State University of New York at New Paltz, United StatesReviewed by:

Wichuda Satidporn, Srinakharinwirot University, ThailandHeike Holbig, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Hidalgo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oliver Fernando Hidalgo, b2xpdmVyLmhpZGFsZ29AdW5pLXBhc3NhdS5kZQ==

Oliver Fernando Hidalgo

Oliver Fernando Hidalgo