94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Polit. Sci., 15 August 2024

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1451601

Aditya Kumar Shukla1*†

Aditya Kumar Shukla1*† Shraddha Tripathi2

Shraddha Tripathi2AI is widely accessible now, and it can fuel the spread of misinformation and pose challenges for democracies across the globe. Year 2024, is a significant democratic milestone is expected to occur as more than 60 nations, representing half the global population, prepare to participate in crucial elections. These elections will involve over 4 billion voters and cover various presidential, legislative, and local contests (Ewe, 2023). However, there are concerns about the integrity of specific electoral procedures due to threats of AI-generated misinformation. Recently held parliamentary elections in Bangladesh, on January 7, 2024, and Pakistan Elections, on February 8, 2024, are facing controversy regarding AI-generated content, which claims there have been compromises in the electoral framework. Elections held in Indonesia on February 14, 2024, also faced the challenges of deep fakes. South Asia was vibrant when the elections were held in the largest democracy India, in May–June 2024. Disinformation and Misinformation also posed many challenges in the elections in India. AI-edited videos were circulated among voters in India claiming that the ruling party would end the reservation and change the constitution if they came into power again. Recently held UK elections also faced controversy about the fake AI candidate. These are all the examples, where deepfake video and audio were used to manipulate the voters, these controversies are alarming trends for the upcoming elections in Europe and other countries The United States, with a population of 160 million registered voters, is scheduled to hold its presidential elections on November 5; according to Jazeera (2024). Europe will also be a central focus as the European Union, where the elections for more than 27 countries are due, with around nine other countries, including Russia and Ukraine, preparing for significant national elections at different times during the year. However, the concern of using AI-generated deep fake video, audio, and AI content is challenging these democratic countries. This article examines the measures of the EU for combating AI-generated misinformation in the election year 2024.

Misinformation, disinformation, and deep fakes are significant threats to democratic societies and can potentially undermine the integrity of election processes. The proliferation of misinformation due to the unrestricted and unverified distribution of information on the internet is a growing concern (Dobber et al., 2020). During election cycles, different actors exploit weaknesses to promote their agendas by spreading misinformation through different means. The impact of misinformation on faith in democratic institutions is that it undermines confidence in the integrity of elections, leading to a decline in trust. Additionally, deep fakes, AI-generated synthetic media, can be utilized by malicious actors to achieve illegitimate political goals, potentially influencing political attitudes and election outcomes (Ecker et al., 2024).

Despite concerns about the persuasive effects of deep fakes on voters and election outcomes, research has shown that warnings about deep fakes in political videos may not necessarily improve discernment, highlighting the challenges in combating the spread of misinformation through deep fakes. The continuous improvement and accessibility of deep fake technology make it increasingly difficult to distinguish between real and manipulated videos, posing a significant threat during political elections. The potential misuse of deep fakes in mass voter misinformation campaigns before elections is a growing worry, and individuals struggle to detect deep fakes effectively, leading to concerns about their use as deceptive tools in influencing election processes. The realism and impact scopes of deep fakes, including fake images, audio, and videos, have made them a real threat to society, with the potential to back sophisticated disinformation campaigns that undermine online trust and democratic processes. It is crucial to address the problem of disinformation and deep fakes to safeguard the integrity of democratic institutions and prevent the manipulation of election outcomes.

Recently held parliamentary elections in Bangladesh on January 7, 2024, and Pakistan Elections on February 8, 2024, faced controversy regarding AI-generated content. Apart from this, elections held in Indonesia on February 14, 2024, also faced the challenges of deep fakes. For instance, several reports were registered for promoting disinformation in the recently held elections in Bangladesh. Facebook has taken down pages and accounts of political parties and their supporters for engaging in coordinated, inauthentic behavior (Dad, 2024). In September 2023, the AFP fact-checking team uncovered a coordinated campaign of op-eds by fake experts in Bangladesh. The country ranks low in free speech and accessible media indicators. The Digital Security Act has been used to arrest and imprison people for criticizing the government on social media (Hasan, 2023).

Political parties in Pakistan have also used deep fake videos to spread fake news and create confusion before the latest national elections. Social media accounts posted videos featuring AI-generated voices of the former Pakistan Prime Minister of the country and his legal advisor, calling for a boycott of the election. Apart from this, several media outlets, including the New York Times, have reported that Imran Khan, the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, announced his victory in the election using a synthesized voice. Reports mentioned that Mr. Khan had been incarcerated and disqualified from participating in the election process. However, his party used artificial intelligence to generate a voice that could convey his message to his supporters. Some media houses even fell for these fake videos and reported them as genuine. PTI workers also accused the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) of using deep fakes to spread confusion and influence election results. The reports from Indonesian elections brought to light some notable concerns regarding the use of AI in political campaigning.

The EDMO Task Force on 2024 European Parliament Elections released a report on disinformation narratives during the 2023 elections in Europe. The report analyzed 900 fact-checking articles published in 11 elections in 10 European countries until October 2023. It revealed that there was widespread disinformation about the electoral process, fuelled by unfounded claims of voter fraud, foreign influences, and unfair practices. The report identified unique disinformation trends in each country, influenced by national contexts and global events. The report emphasized the need for robust fact-checking and awareness-raising initiatives to preserve electoral integrity and democratic values (EDMO, 2023).

This report shows proper preparation for the 2024 European Parliament elections is required. The European Union (EU) has already started implementing preventative measures to counter the possible impact of false information and AI-generated deep fakes and employing a multi-faceted approach to tackle the challenge. The EU's plan includes several key initiatives, including legal regulations, collaboration with tech companies, and public awareness campaigns. Under the recently implemented Digital Services Act (DSA; Roth, 2023), large online platforms like Facebook and TikTok must identify and label manipulated audio and imagery, including deep fakes, by August 2025. This regulation aims to increase transparency and user awareness.

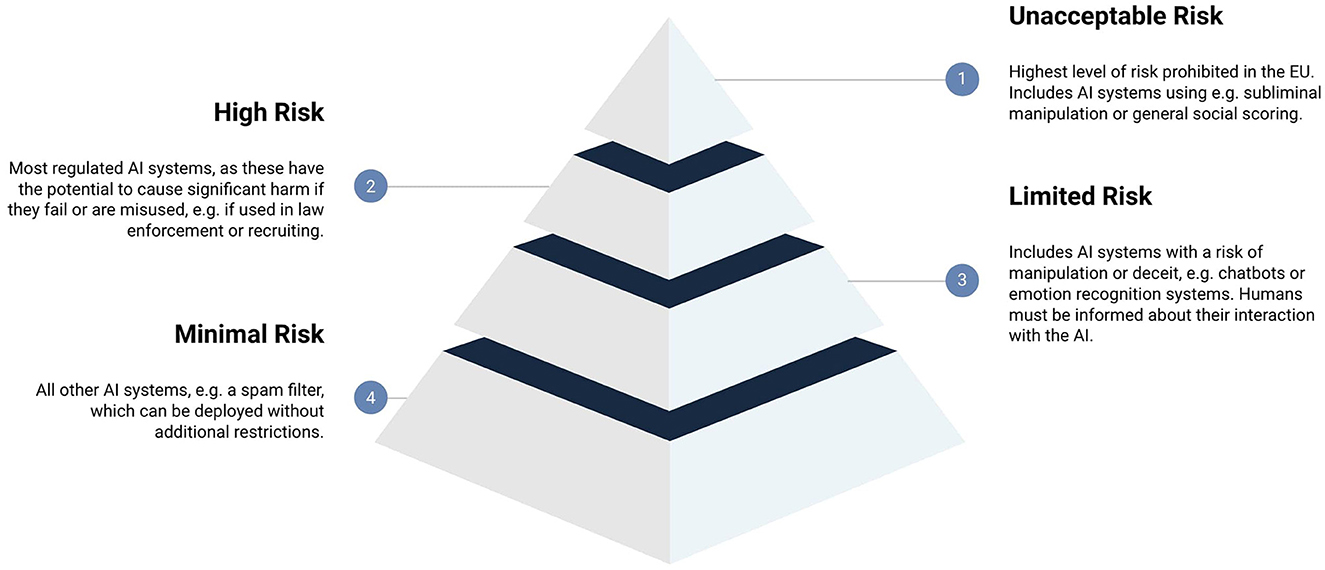

Recently, the AI Act (European Parliament, 2023) got the final approval of the EU Commission. It aims to establish a comprehensive legal framework for AI to mitigate the risks associated with deep fakes. This includes measures like transparency requirements for deep fake creators and distributors, prohibitions on harmful deep fakes, and risk assessments for high-risk AI uses like deep fakes. This act provides the risk-based approach as follows (AI Act, 2024) (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Risks classified by EU ACT. Source: https://www.trail-ml.com/blog/eu-ai-act-how-risk-is-classified.

Minimal risk: AI systems that do not pose any risk to citizens' rights or safety, such as spam filters and video games.

Limited risk: AI systems like chatbots or assistants must be transparent and quickly switched off.

High risk: AI systems that can harm people's interests, such as facial recognition, surgical robots, and applications to sort CVs from job candidates. These systems will be carefully assessed before being put on the market and throughout their lifecycle.

Unacceptable: AI systems that pose a clear threat to the safety, livelihoods, and rights of people, such as social scoring by governments, exploitation of vulnerabilities of children, and use of subliminal techniques. The Commission will ban these systems.

This act also defines disinformation, deep fakes, and AI-generated deep fakes in it Recital 60m, Recital 60v, Recital 70a, Recital 70d, Article 52, Recital 70b, Article 3, first paragraph, point (44) (bl), and Article 52 (3). However, it focuses mainly on marking and watermarking AI content. Marking is necessary but detecting, and removing disinformation after it has spread is also important. Only marking will not help prevent the dissemination of disinformation before it causes harm. It may only be effective in reducing the harmful effects of false information if the audience is well-informed about how to identify and handle it.

Additionally, the EU urges significant tech companies to develop and implement tools for detecting and removing deep fakes from their platforms, especially during critical events like elections. TikTok and Meta, for instance, are creating fact-checking hubs and “election centers” for the upcoming EU elections (AP, 2024). The EU is also investing in public awareness campaigns to educate citizens on identifying deep fakes and being critical consumers of online content. It includes promoting media literacy initiatives and encouraging fact-checking practices.

European Union has taken proactive steps to address this issue, including supporting media literacy initiatives, funding research and development, encouraging platform action, promoting cooperation, considering regulations, and doing acts. It is visible that by putting pressure on social media platforms and other online services to develop clear policies against deepfakes, the EU ensures that users have a safe and trustworthy online experience. By promoting cooperation between online platforms, fact-checking organizations, and law enforcement agencies, the EU creates a more effective system for identifying and removing harmful content. The EU is also educating citizens on critically evaluating online content and improving deepfake detection technologies, which empowers people to make informed decisions about the information they consume. The EU also calls for creating an independent European network of fact-checkers to help analyze the sources and processes of content creation. By these means, the EU ensures that our democratic processes are not manipulated by false information, which is essential to maintaining the integrity of our society.

It is too early to determine the effectiveness of the measures against misinformation, but there are potential benefits and challenges. The benefits include increased transparency, better identification and removal of harmful content, and improved media literacy skills for citizens. Apart from this, the challenges include eradicating misinformation due to online content's volume and evolving nature, balancing freedom of expression with the need to combat harmful content and ensuring the accuracy and neutrality of fact-checking organizations. The EU's multifaceted approach offers promise, but the long-term effectiveness will depend on continuous adaptation and collaboration between various stakeholders.

Using AI-generated deep fakes and disinformation is a growing concern for democratic societies during election cycles. The potential impact of deep fakes on voter attitudes and election outcomes must addressed. Recent reports from recent elections in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Indonesia highlight the alarming trend of using deep fakes and AI-generated content to manipulate election results. Therefore, it is crucial to combat the spread of AI-generated misinformation to safeguard the integrity of democratic institutions and prevent the manipulation of election outcomes. Upcoming elections certainly serve as a crucial test for the effectiveness of the measures taken to tackle disinformation, misinformation, and AI deep fakes. The EU's efforts to address the problem of disinformation and deep fakes during the 2024 election year will be worth watching closely, including the impact of the AI Act. It will demonstrate the EU's commitment to safeguarding the integrity of elections by combating the spread of misinformation.

AS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

AI Act (2024). Shaping Europe's Digital Future. Available at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai (accessed January 5, 2024).

AP (2024). TikTok Prepares to Combat Misinfo, AI Fakes and Influence Ops Ahead of European Union Election. The Economic Times. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/technology/tiktok-prepares-to-combat-misinfo-ai-fakes-and-influence-ops-ahead-of-european-union-election/articleshow/107699941.cms?from=mdr (accessed March 8, 2024).

Dad, N. (2024). The Deepfake Elections Are Here. Context. Available at: https://www.context.news/ai/opinion/the-deepfake-elections-are-here (accessed Feburary 26, 2024).

Dobber, T., Metoui, N., Trilling, D., Helberger, N., and Vreese, C. (2020). Do (microtargeted) deepfakes have real effects on political attitudes? Int. J. Press Polit. 26, 69–91. doi: 10.1177/1940161220944364

Ecker, U., Roozenbeek, J., Tay, L. Q., Cook, J., Oreskes, N., and Lewandowsky, S. (2024). Misinformation poses a bigger threat to democracy than you might think. Nature 630, 29–32. doi: 10.1038/d41586-024-01587-3

EDMO (2023). Disinformation Narratives During the 2023 Elections in Europe. Available at: https://edmo.eu/publications/disinformation-narratives-during-the-2023-elections-in-europe/ (accessed Feburary 25, 2024).

European Parliament (2023). EU AI Act: First Regulation on Artificial Intelligence, Topics. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence (accessed Feburary 20, 2024).

Ewe, K. (2023). The Ultimate Election Year: All the Elections Around the World in 2024. TIME. Available at: https://time.com/6550920/world-elections-2024/ (accessed Feburary 26, 2024).

Hasan, M. (2023). Deep Fakes and Disinformation in Bangladesh. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2023/12/deep-fakes-and-disinformation-in-bangladesh/ (accessed Feburary 20, 2024).

Jazeera, A. (2024). British PM Sunak Says He Expects General Election in Second Half of 2024. Al Jazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/4/british-pm-sunak-says-he-expects-general-election-in-second-half-of-2024 (accessed March 6, 2024).

Roth, E. (2023). The EU's Digital Services Act Is Now in Effect: Here's What That Means. The Verge. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/23845672/eu-digital-services-act-explained (accessed Feburary 21, 2024).

Keywords: AI, misinformation, disinformation, EU, elections

Citation: Shukla AK and Tripathi S (2024) AI-generated misinformation in the election year 2024: measures of European Union. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1451601. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1451601

Received: 19 June 2024; Accepted: 25 July 2024;

Published: 15 August 2024.

Edited by:

Régis Dandoy, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, EcuadorReviewed by:

Tiago Silva, University of Lisbon, PortugalCopyright © 2024 Shukla and Tripathi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aditya Kumar Shukla, ZHIuYWtzaHVrbGEyNkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†ORCID: Aditya Kumar Shukla orcid.org/0000-0002-6808-5384

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.