- 1School of Medicine, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Department of Ophthalmology, Saarland University Medical Center, Homburg/Saar, Germany

- 3Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Medical Faculty, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

- 4Institute of Physiology, Center for Space Medicine and Extreme Environments Berlin, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 5Université Paris Cité, Faculté de Pharmacie, MTCI ED 563, Paris, France

- 6INSERM UMRS 970 Paris Centre de Recherche Cardiovasculaire (PARCC), Paris, France

- 7Ocular Surface Center, Department of Ophthalmology, Baylor College of Medicine, Cullen Eye Institute, Houston, TX, United States

- 8Department of Ophthalmology, Otago University, Dunedin, New Zealand

- 9Department of Ophthalmology, Girona University, Girona, Spain

- 10Antimicrobial Resistance and Mobile Elements Group, Ingham Institute of Applied Medical Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 11Beyond 700 Pty Ltd, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Human spaceflight subjects the body to numerous and unique challenges. Astronauts frequently report a sense of sinonasal congestion upon entering microgravity for which the exact pathomechanisms are unknown. However, cephalad fluid shift seems to be its primary cause, with CO2 levels and environmental irritants playing ancillary roles. Current management focuses on pharmacotherapy comprising oral and nasal decongestants and antihistamines. These are among the most commonly used treatments in astronauts. With longer and more distant space missions on the horizon, there is a need for efficacious and payload-sparing non-pharmacological interventions. Neurostimulation is a promising countermeasure technology for many ailments on Earth. In this paper, we explore the risk factors and current treatment modalities for sinonasal congestion in astronauts, highlight the limitations of existing approaches, and argue for why neurostimulation should be considered.

1 Introduction

The sinonasal system consists of the air-filled nasal cavity, including the turbinates, and the adjacent sinuses, separated by the nasal septum. Its mucosal lining, rich in blood vessels, glands, and nerve endings, supports functions such as smelling, humidifying, cleaning, and warming inhaled air, while also providing immune defense (Elad et al., 2008; Sahin-Yilmaz and Naclerio, 2011). The nasal cycle, alternating congestion and decongestion between sides, helps maintain nasal functions but can be disrupted by nasal congestion, which also affects adjacent organs such as the eyes and ears (Pendolino et al., 2018; Susaman et al., 2021).

In-flight nasal congestion and sinonasal symptoms (facial pressure and pain or “sinus pain”) were reported by 62% of space shuttle crew members during postflight medical debriefings (Clément, 2011; Khan et al., 2024). Congestion was the most common otorhinolaryngological complaint among ISS astronauts and one of the most frequent complaints in general (Alexander, 2021). Thus, NASA considers nasal congestion highly likely to occur during any space mission (NASA, 2016).

Sinonasal congestion, like dry eye disease, is more of a nuisance than an immediate medical risk (Ax et al., 2023). However, it can interfere with mission tasks, thereby compromising productivity, cause fluid loss from the body through mouth breathing, and change smell and taste (Rudmik et al., 2014; Lane et al., 2016; Hummel et al., 2017; Marshburn et al., 2019). Nasal congestion increases the likelihood of barotrauma in situations of environmental pressure changes such as during extravehicular activity (Iannella et al., 2017; Pilmanis and Clark, 2019; Chen et al., 2023). Moreover, it can exacerbate the already highly prevalent sleep issues in orbit (Albornoz-Miranda et al., 2023). Over time, mucosal edema might impair the nasal cycle, cause eustachian tube dysfunction and reduce ventilation of the paranasal sinuses, thereby increasing infection risk (Marshburn et al., 2019; Macias et al., 2020; Susaman et al., 2021). An unexpected but likely consequence of mucosal swelling could be tear dysfunction through decreased nasal tear drainage and tear production; nasal breathing contributes around 30% to basal tear secretion (Gupta et al., 1997; Ax et al., 2023). Nasal congestion in combination with elevated CO2 levels may also contribute to the frequent headaches observed during spaceflight (Law et al., 2014; Kazaz et al., 2021).

2 Potential mechanisms and risk factors

2.1 Cephalad fluid shift

Microgravity causes ∼2L of fluid to move towards the upper body and head of astronauts within the first 6–10 h (Thornton et al., 1987). This phenomenon is called cephalad fluid shift (CFS), typified by facial puffiness and bird legs (Thornton et al., 1974). CFS is the major contributing factor to sinonasal congestion in astronauts (Hargens and Richardson, 2009; Marshall-Goebel et al., 2019; Stenger and Macias, 2020). CFS-related congestion is likely to occur in the abundant spongy tissue filled with venous sinusoids in the nasal mucosa (Burnham, 1941; Ng et al., 1999). These tissues have limited ways of regulating their microcirculation during CFS and therefore experience fluid extravasation (Aratow et al., 1991; Parazynski et al., 1991). On-orbit examination shows increased erythema and edema of the nasal mucosa (Harris et al., 1997). Periorbital puffiness, facial edema and thickening of the eyelids last to varying degrees for the entire duration of microgravity exposure making persistent intranasal swelling likely (Schneider et al., 2016; Hamilton, 2019; Karlin et al., 2021).

The effects of CFS are difficult to study upon return to Earth because they disappear. Nevertheless, magnetic resonance imaging showed increased mastoid effusions after ISS missions although there were no changes in the paranasal sinuses (Inglesby et al., 2020). Asymptomatic mastoid effusions are also known to occur in supine patients (head-down bed rest, intensive care unit patients) making a strong case for CFS being their primary cause (Huyett et al., 2017; Lecheler et al., 2021). Remarkably, facial tissue thickness was below control values immediately on return to Earth reaching baseline values after 4 days (Kirsch et al., 1993).

2.2 CO2 levels

CO2 levels are at least 10 times higher on the ISS than on Earth (Law et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2020). CO2 is a potent vasodilator and may lead to further engorgement of the nasal mucosal vessels (Ito et al., 2003).

This factor might partially explain why sinonasal symptoms persist over many months even though facial puffiness redistributes a few days after entering microgravity (Kirsch et al., 1993; Cole et al., 2019). CO2 has also been implicated in dry eye disease and headaches in astronauts (Law et al., 2014; Sampige et al., 2024).

However, while similarly high CO2 levels are found in submarines, decongestant use in submariners is ∼150 times lower than in astronauts suggesting that CO2 might just be a minor contributor to sinonasal congestion in microgravity (Wotring, 2015).

Enigmatically, CO2 applied directly to the nasal mucosa is used to treat both nasal congestion and migraine headaches likely by suppressing neuropeptide release from the trigeminal nerves (Hurst, 1931; Casale et al., 2008; Spierings, 2024).

2.3 Environmental irritants

Despite extensive screening of astronauts for allergies, allergic symptoms are prevalent and contribute to sinonasal congestion (Wotring, 2015). Most likely, this is caused by increased exposure to bioaerosols as dust does not settle in microgravity and spacecraft are closed environments in which allergens and irritants accumulate, and microbe growth is promoted (Oubre et al., 2016; Jahn et al., 2021).

Even in the absence of a specific allergy, nasal mucosa might become hyperreactive to irritants and allergens in space because of immune system alterations (Crucian et al., 2013; Torun et al., 2021). Changes to the nasal microbiome might further contribute to mucosal inflammation (Salzano et al., 2018). Nasal toxicity of extraterrestrial dust should also be considered for upcoming Moon and Mars missions (Miranda et al., 2023). Lunar dust has already demonstrated its irritative properties during the Apollo missions (Hardison et al., 2023), and Martian dust contains dust contains irritant, reactive perchlorates (Davila et al., 2013; Crotts, 2014).

3 Countermeasures

3.1 Pharmacological countermeasures

Astronauts take decongestant medication and antihistamines to combat sinonasal symptoms. The use of antibiotics is uncommon since acute respiratory infection and consequent bacterial sinusitis are very rare due to strict preflight screening and quarantine regimens (Alexander, 2021; Vernikos, 2022). Decongestants mimic sympathetic activation leading to vasoconstriction and reduced mucosal swelling (Johnson and Hricik, 1993), while antihistamines block the vasodilative effect of histamine at the H1 receptor (Ashina et al., 2015).

Decongestants are the most common medication used chronically (>7 days) by ISS astronauts, and the third most used in the acute context. Overall, 55% of astronauts reported use of decongestant medication with 2.4 medication uses per crew member for ISS missions (Wotring, 2015). Monitoring medication use relies on astronauts self-reporting during postflight debriefings or flight physician notes from private medical conferences. Thus, actual decongestant use is likely to be higher due to underreporting (Wotring, 2015; Blue et al., 2019).

Pharmacotherapy during spaceflight has assumed that pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are comparable to those on Earth (Grover and Pathak, 2020; Barchetti et al., 2024). This may not be completely true, given the different outcomes reported by astronauts. Regarding decongestants, 21% of astronauts report them being very effective with the remainder stating “somewhat effective” (39%), “ineffective” (2%) or “unknown” (37%) due to lack of information (Blue et al., 2019).

Topical decongestants come in the form of drops and sprays. Nasal drop application in microgravity is problematic because a globule of fluid must be wicked into the nose instead of “dropping” it. These globules risk resource waste and overdose because they are three to six times the size of a regular drop (Mader et al., 2019). Long-term use could lead to dependency and drug-induced rhinitis inherent with topical decongestants (Varghese et al., 2010).

Contact of the dropper bottle with the mucosa prohibits sharing among crew members due to contamination (Aydin et al., 2007). Nasal sprays have the additional risk of (bio)aerosol generation.

Systemic drugs are easier to use but more likely than topical ones to have side effects that involve other organs, such as exacerbating dry eye symptoms through their anticholinergic effects (Gomes et al., 2017; Unsal et al., 2018). Payload requirements, finite supplies and use-by dates limit medication availability in space. Despite the presence of a pharmacy onboard the ISS, the awareness by astronauts that medications are a scarce resource leads to a reluctance to use them even when potentially beneficial (Barchetti et al., 2024).

3.2 Non-pharmacological and environmental countermeasures

Non-pharmacological solutions remove the restrictions associated with medication use. To counter CFS, a low-tech solution such as Braslet occlusion cuffs sequesters fluid in the lower extremities and reduces facial puffiness (Hamilton et al., 2012). Whether this also ameliorates symptoms is unclear (Schneider et al., 2016). Lower body negative pressure and artificial gravity are other alternatives but are technically more challenging (Clement et al., 2015; Hamilton, 2019).

CO2-related symptoms might be reduced by more effective approaches to monitor and scrub the cabin atmosphere of excess CO2 (Georgescu et al., 2020; Georgescu et al., 2021). Similarly, better air filtration and cabin hygiene could reduce bioaerosols, leading to fewer allergic symptoms (Haines et al., 2019; Marshburn et al., 2019).

3.3 Neurostimulation

Engorgement of the nasal vasculature through CFS and other factors (CO2, environmental irritants) is the main cause of sinonasal symptoms in astronauts (Stenger and Macias, 2020). Nasal vessels are modulated by nerve fibers of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) (Baraniuk and Merck, 2009; Kahana-Zweig et al., 2016) whereby sympathetic vasoconstriction chiefly determines nasal patency on Earth (Lung, 1995; Susaman et al., 2021). The ANS also partly mediates mucociliary clearance, a process essential for the removal of mucus and irritants, which is potentially impaired in space (Beule, 2010; Prisk, 2019; Smith et al., 2024). Thus, dysfunction of the ANS contributes causally to sinonasal congestion (Yao et al., 2018).

In astronauts, targeted sympathetic activation might counteract both CFS and CO2-related vasodilation in the nasal mucosa (Shusterman et al., 2023). Neurostimulation is a technique that offers therapy by targeted modulation of neural activity. It is widely used in treating conditions as diverse as epilepsy, diabetes, and chronic pain (Errico, 2018; Mehta et al., 2018; Stanton-Hicks, 2018).

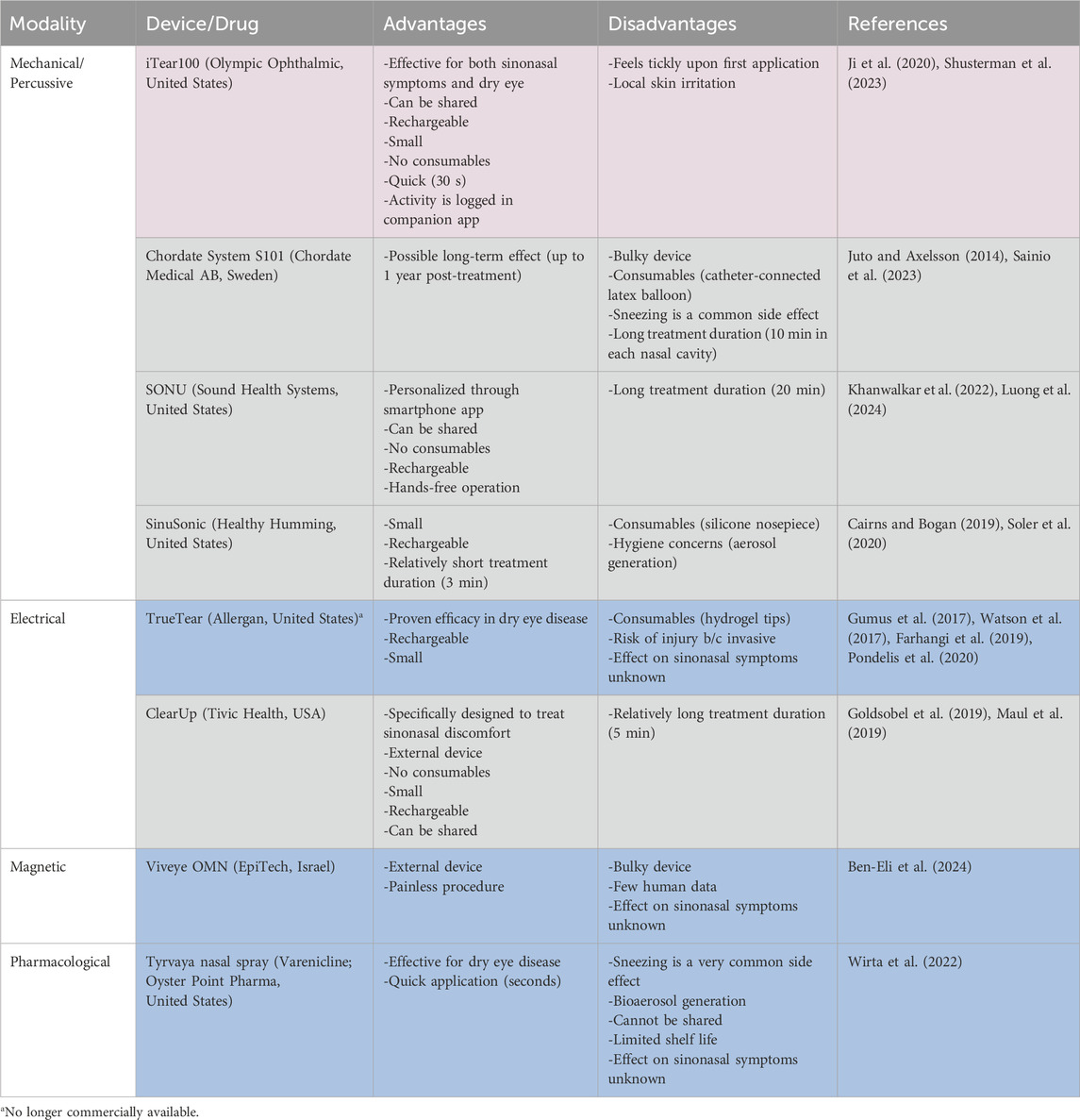

On Earth, several neurostimulation methods have been introduced to relieve nasal congestion in allergic and chronic rhinosinusitis patients (Phillips et al., 2022; Shusterman et al., 2023). Similar methods are being explored for treating dry eye disease (Mittal et al., 2021). In both cases, the target nerve is the anterior branch of the ethmoidal nerve, itself part of the trigeminal nerve (Dieckmann et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020). This nerve can be accessed intra-nasally through electrical, mechanical, and pharmaceutical stimulation as well as extra-nasally through mechanical and magnetic stimulation (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of Nasal Neurostimulation modalities/types (Blue: ocular; grey: nasal; violet: both).

Proven terrestrial efficacy does not automatically deem an approach suitable for use in space. Some neurostimulation devices are too bulky whereas others need consumables to function (Table 1). Extra-nasal devices have a smaller injury risk compared to intra-nasal (invasive) devices. Additionally, intra-nasal devices trigger sneezing as a side effect more frequently which might expedite the spread of disease vectors throughout the spacecraft cabin (Mermel, 2013; Wirta et al., 2022).

Pharmacological neurostimulation comes with all described constraints associated with pharmacotherapy in space and thus offers no clear advantages over drugs already in use.

In our view, there are currently three devices which can be considered for use in astronauts (Table 1).

1. iTear100 is an extranasal mechanical neurostimulator that has proven effective for treating both ocular and sinonasal symptoms.

2. SONU is a vibrational headband that gets programmed to match the natural resonant frequency of the sinonasal cavity of the individual.

3. ClearUp uses extranasal electrical stimulation and is specifically approved to treat sinonasal symptoms.

The advantages of these devices are that they are small in size, rechargeable, lack consumables, and have minimal side effects. A single device can be utilized by multiple crewmembers and use can be logged automatically to provide accurate data on use frequency (Wotring and Smith, 2020). However, there are still many unknowns associated with their appropriate application: ideal modality (electrical versus mechanical), intensity and frequency of application, duration and size of treatment effect as well as possible adaptation to the stimulus remain to be determined in astronauts. Device settings may also be tailored to the individual astronaut by developing treatment protocols (e.g., duration, intensity, frequency of stimulation) based on crewmembers’ specific physiology and needs (Denison and Morrell, 2022).

4 Discussion and conclusion

Sinonasal congestion is very common in astronauts. Mild cases may impact astronaut wellbeing and productivity, while severe cases could substantially hinder the execution of mission-critical tasks. Nasal neurostimulation has the potential to provide a safe and effective non-pharmacological treatment option for sinonasal congestion in astronauts, thus overcoming the limitations of using pharmaceuticals in space. The apparently common practice among astronauts of long-term decongestant use is of particular concern (Wotring, 2015) and could in itself be a significant factor for long-term nasal congestion since continued use decreases responsiveness to subsequent decongestion efforts (Varghese et al., 2010). Neurostimulation is attractive because it offers an avenue to reduce or even replace decongestant use and may also be used to treat different medical conditions such as dry eye disease and thus reducing the number of devices needed on a flight.

With the projected increase in private spaceflight, less stringent astronaut selection criteria will likely become more common (Griko et al., 2022). This could include candidates with preexisting allergic and chronic rhinosinusitis. These astronauts might require more aggressive treatment in orbit (oral medication, etc.) or even surgery prior to the mission to reduce risks of infections (Fokkens et al., 2020).

While there are multiple neurostimulators commercially available, few seem suitable for human spaceflight. Unlimited shelf life, rechargeability, lack of consumables and potential to be used by multiple users are crucial characteristics to be met. Despite these attractive features, they must be tested in space to develop protocols regarding duration, intensity, and use frequency because these might differ from those that are established on Earth. Chiefly, it must be determined whether neurostimulation alone is able to overcome the CFS-related increased fluid pressures. Preliminary studies during parabolic flights and short-duration spaceflights will provide insights.

Author contributions

TA: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. PZ: Writing–review and editing. TB: Conceptualization, Writing–review and editing. KB: Writing–review and editing. CP: Writing–review and editing. FM: Conceptualization, Writing–review and editing. SJ: Supervision, Writing–review and editing. TM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. CSdP receives salary support from Caroline Elles Professorship and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine.

Conflict of interest

Author TM was employed by Beyond 700 Pty Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albornoz-Miranda M., Parrao D., Taverne M. (2023). Sleep disruption, use of sleep-promoting medication and circadian desynchronization in spaceflight crewmembers: evidence in low-Earth orbit and concerns for future deep-space exploration missions. Sleep. Med. X 6, 100080. doi:10.1016/j.sleepx.2023.100080

Aratow M., Hargens A. R., Meyer J. U., Arnaud S. B. (1991). Postural responses of head and foot cutaneous microvascular flow and their sensitivity to bed rest. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 62 (3), 246–251.

Ashina K., Tsubosaka Y., Nakamura T., Omori K., Kobayashi K., Hori M., et al. (2015). Histamine induces vascular hyperpermeability by increasing blood flow and endothelial barrier disruption in vivo. PLoS One 10 (7), e0132367. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132367

Ax T., Ganse B., Fries F. N., Szentmary N., de Paiva C. S., March de Ribot F., et al. (2023). Dry eye disease in astronauts: a narrative review. Front. Physiol. 14, 1281327. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1281327

Aydin E., Hizal E., Akkuzu B., Azap O. (2007). Risk of contamination of nasal sprays in otolaryngologic practice. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 7, 2. doi:10.1186/1472-6815-7-2

Baraniuk J. N., Merck S. J. (2009). Neuroregulation of human nasal mucosa. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1170, 604–609. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04481.x

Barchetti K., Derobertmasure A., Boutouyrie P., Sestili P. (2024). Redefining space pharmacology: bridging knowledge gaps in drug efficacy and safety for deep space missions. Front. Space Technol. 5. doi:10.3389/frspt.2024.1456614

Ben-Eli H., Perelman S., Wajnsztajn D., Solomon A. (2024). Evaluating magnetic stimulation as an innovative approach for treating dry eye syndrome: safety and efficacy initial study. medRxiv, 2024.2003.2027.24304988. doi:10.1101/2024.03.27.24304988

Beule A. G. (2010). Physiology and pathophysiology of respiratory mucosa of the nose and the paranasal sinuses. GMS Curr. Top. Otorhinolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 9, Doc07. doi:10.3205/cto000071

Blue R. S., Bayuse T. M., Daniels V. R., Wotring V. E., Suresh R., Mulcahy R. A., et al. (2019). Supplying a pharmacy for NASA exploration spaceflight: challenges and current understanding. NPJ Microgravity 5, 14. doi:10.1038/s41526-019-0075-2

Burnham H. H. (1941). A clinical study of the inferior turbinate cavernous tissue; its divisions and their significance. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 44 (5), 477–481.

Cairns A., Bogan R. (2019). The SinuSonic: reducing nasal congestion with acoustic vibration and oscillating expiratory pressure. Med. Devices (Auckl) 12, 305–310. doi:10.2147/MDER.S212207

Casale T. B., Romero F. A., Spierings E. L. H. (2008). Intranasal noninhaled carbon dioxide for the symptomatic treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 121 (1), 105–109. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.08.056

Chen T., Pathak S., Hong E. M., Benson B., Johnson A. P., Svider P. F. (2023). Diagnosis and management of barosinusitis: a systematic review. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 132 (1), 50–62. doi:10.1177/00034894211072353

Clement G. R., Bukley A. P., Paloski W. H. (2015). Artificial gravity as a countermeasure for mitigating physiological deconditioning during long-duration space missions. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 9, 92. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2015.00092

Cole R., Coble C., Mason S. S., Baker M. W., Young M. H. (2019). “Nasal congestion on the international space station,” in Aerospace medical association annual scientific meeting (Las Vegas, NV, USA).

Crotts A. (2014). The new Moon: water, exploration, and future habitation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Crucian B., Stowe R., Mehta S., Uchakin P., Quiriarte H., Pierson D., et al. (2013). Immune system dysregulation occurs during short duration spaceflight on board the space shuttle. J. Clin. Immunol. 33 (2), 456–465. doi:10.1007/s10875-012-9824-7

Davila A. F., Willson D., Coates J. D., McKay C. P. (2013). Perchlorate on Mars: a chemical hazard and a resource for humans. Int. J. Astrobiol. 12 (4), 321–325. doi:10.1017/s1473550413000189

Denison T., Morrell M. J. (2022). Neuromodulation in 2035: the neurology future forecasting series. Neurology 98 (2), 65–72. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000013061

Dieckmann G., Fregni F., Hamrah P. (2019). Neurostimulation in dry eye disease-past, present, and future. Ocul. Surf. 17 (1), 20–27. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2018.11.002

Elad D., Wolf M., Keck T. (2008). Air-conditioning in the human nasal cavity. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 163 (1-3), 121–127. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2008.05.002

Errico J. P. (2018). “Insulin resistance, glucose metabolism, inflammation, and the role of neuromodulation as a therapy for type-2 diabetes,” in Neuromodulation, 1565–1573.

Farhangi M., Cheng A. M., Baksh B., Sarantopoulos C. D., Felix E. R., Levitt R. C., et al. (2019). Effect of non-invasive intranasal neurostimulation on tear volume, dryness and ocular pain. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 104, 1310–1316. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-315065

Fokkens W. J., Lund V. J., Hopkins C., Hellings P. W., Kern R., Reitsma S., et al. (2020). European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology 58 (Suppl. S29), 1–464. doi:10.4193/Rhin20.600

Georgescu M. R., Meslem A., Nastase I. (2020). Accumulation and spatial distribution of CO2 in the astronaut's crew quarters on the International Space Station. Build. Environ. 185, 107278. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107278

Georgescu M. R., Meslem A., Nastase I., Bode F. (2021). Personalized ventilation solutions for reducing CO2 levels in the crew quarters of the International Space Station. Build. Environ. 204, 108150. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108150

Goldsobel A. B., Prabhakar N., Gurfein B. T. (2019). Prospective trial examining safety and efficacy of microcurrent stimulation for the treatment of sinus pain and congestion. Bioelectron. Med. 5, 18. doi:10.1186/s42234-019-0035-x

Gomes J. A. P., Azar D. T., Baudouin C., Efron N., Hirayama M., Horwath-Winter J., et al. (2017). TFOS DEWS II iatrogenic report. Ocul. Surf. 15 (3), 511–538. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.004

Griko Y. V., Loftus D. J., Stolc V., Peletskaya E. (2022). Private spaceflight: a new landscape for dealing with medical risk. Life Sci. Space Res. (Amst) 33, 41–47. doi:10.1016/j.lssr.2022.03.001

Grover A., Pathak Y. V. (2020). “Implications of microgravity on microemulsions and nanoemulsions,” in Handbook of space pharmaceuticals. Editors Y. Pathak, M. Araújo dos Santos, and L. Zea (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 1–11.

Gumus K., Schuetzle K. L., Pflugfelder S. C. (2017). Randomized controlled crossover trial comparing the impact of sham or intranasal tear neurostimulation on conjunctival goblet cell degranulation. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 177, 159–168. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.03.002

Gupta A., Heigle T., Pflugfelder S. C. (1997). Nasolacrimal stimulation of aqueous tear production. Cornea 16 (6), 645–648. doi:10.1097/00003226-199711000-00008

Haines S. R., Bope A., Horack J. M., Meyer M. E., Dannemiller K. C. (2019). Quantitative evaluation of bioaerosols in different particle size fractions in dust collected on the International Space Station (ISS). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103 (18), 7767–7782. doi:10.1007/s00253-019-10053-4

Hamilton D. R. (2019). “Cardiovascular aspects of space flight,” in Principles of clinical medicine for space flight. Editors M. R. Barratt, E. S. Baker, and S. L. Pool (New York, NY: Springer), 673–710.

Hamilton D. R., Sargsyan A. E., Garcia K., Ebert D. J., Whitson P. A., Feiveson A. H., et al. (2012). Cardiac and vascular responses to thigh cuffs and respiratory maneuvers on crewmembers of the International Space Station. J. Appl. Physiol. 112 (3), 454–462. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00557.2011

Hardison S. A., Thorp B. D., Ebert C. S., Klatt-Cromwell C. N., Senior B. A., Kimple A. J. (2023). Lunar dust: a unique nasal irritant forgotten by history. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 13 (10), 1849–1851. doi:10.1002/alr.23263

Hargens A. R., Richardson S. (2009). Cardiovascular adaptations, fluid shifts, and countermeasures related to space flight. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 169 (Suppl. 1), S30–S33. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2009.07.005

Harris B. A., Billica R. D., Bishop S. L., Blackwell T., Layne C. S., Harm D. L., et al. (1997). Physical examination during space flight. Mayo Clin. Proc. 72 (4), 301–308. doi:10.4065/72.4.301

Hummel T., Whitcroft K. L., Andrews P., Altundag A., Cinghi C., Costanzo R. M., et al. (2017). Position paper on olfactory dysfunction. Rhinology J. 54 (26), 1–30. doi:10.4193/Rhino16.248

Hurst A. F. (1931). The use of carbon dioxide in the treatment of vasomotor rhinitis, hay fever and asthma. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 24 (4), 441–442. doi:10.1177/003591573102400422

Huyett P., Raz Y., Hirsch B. E., McCall A. A. (2017). Radiographic mastoid and middle ear effusions in intensive care unit subjects. Respir. Care 62 (3), 350–356. doi:10.4187/respcare.05172

Iannella G., Lucertini M., Pasquariello B., Manno A., Angeletti D., Re M., et al. (2017). Eustachian tube evaluation in aviators. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 274 (1), 101–108. doi:10.1007/s00405-016-4198-8

Inglesby D. C., Antonucci M. U., Spampinato M. V., Collins H. R., Meyer T. A., Schlosser R. J., et al. (2020). Spaceflight-associated changes in the opacification of the paranasal sinuses and mastoid air cells in astronauts. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 146, 571–577. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0228

Ito H., Kanno I., Ibaraki M., Hatazawa J., Miura S. (2003). Changes in human cerebral blood flow and cerebral blood volume during hypercapnia and hypocapnia measured by positron emission tomography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 23 (6), 665–670. doi:10.1097/01.WCB.0000067721.64998.F5

Jahn L. G., Bland G. D., Monroe L. W., Sullivan R. C., Meyer M. E. (2021). Single-particle elemental analysis of vacuum bag dust samples collected from the International Space Station by SEM/EDX and sp-ICP-ToF-MS. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 55 (5), 571–585. doi:10.1080/02786826.2021.1874610

Ji M. H., Moshfeghi D. M., Periman L., Kading D., Matossian C., Walman G., et al. (2020). Novel extranasal tear stimulation: pivotal study results. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9 (12), 23. doi:10.1167/tvst.9.12.23

Johnson D. A., Hricik J. G. (1993). The pharmacology of α-adrenergic decongestants. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 13 (6P2). doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1993.tb02779.x

Juto J. E., Axelsson M. (2014). Kinetic oscillation stimulation as treatment of non-allergic rhinitis: an RCT study. Acta Otolaryngol. 134 (5), 506–512. doi:10.3109/00016489.2013.861927

Kahana-Zweig R., Geva-Sagiv M., Weissbrod A., Secundo L., Soroker N., Sobel N. (2016). Measuring and characterizing the human nasal cycle. PLoS One 11 (10), e0162918. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162918

Karlin J. N., Farajzadeh J., Stacy S., Esfandiari M., Rootman D. B. (2021). The effect of zero gravity on eyelid and brow position. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 37 (6), 592–594. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001961

Kazaz H., Bayar Muluk N., Wenig B. L. (2021). “Does nasal disease cause headaches?,” in Challenges in rhinology. Editors C. Cingi, N. Bayar Muluk, G. K. Scadding, and R. Mladina (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 397–404.

Khan F. I., Somawardana I., Dongre R., Khan N. S., Rashidi K., Razmi S., et al. (2024). Clearing new frontiers: sinonasal Health and the future of spaceflight. Ear Nose Throat J. 1455613241274865, 1455613241274865. doi:10.1177/01455613241274865

Khanwalkar A., Johnson J., Zhu W., Johnson E., Lin B., Hwang P. H. (2022). Resonant vibration of the sinonasal cavities for the treatment of nasal congestion. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 12 (1), 120–123. doi:10.1002/alr.22877

Kirsch K. A., Baartz F. J., Gunga H. C., Roecker L., Wicke H. J., Buensch B. (1993). Fluid shifts into and out of superficial tissues under microgravity and terrestrial conditions. Clin. Investigator 71 (9), 687–689. doi:10.1007/bf00209721

Lane H. W., Smith S. M., Kloeris V. L. (2016). “Metabolism and nutrition,” in Space physiology and medicine: from evidence to practice. Editors A. E. Nicogossian, R. S. Williams, C. L. Huntoon, C. R. Doarn, J. D. Polk, and V. S. Schneider (New York, NY: Springer New York), 307–321.

Law J., Van Baalen M., Foy M., Mason S. S., Mendez C., Wear M. L., et al. (2014). Relationship between carbon dioxide levels and reported headaches on the international space station. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 56 (5), 477–483. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000158

Lecheler L., Paulke F., Sonnow L., Limper U., Schwarz D., Jansen S., et al. (2021). Gravity and mastoid effusion. Am. J. Med. 134 (3), e181–e183. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.09.020

Lee A. G., Mader T. H., Gibson C. R., Tarver W., Rabiei P., Riascos R. F., et al. (2020). Spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) and the neuro-ophthalmologic effects of microgravity: a review and an update. NPJ Microgravity 6, 7. doi:10.1038/s41526-020-0097-9

Li L., London N. R., Prevedello D. M., Carrau R. L. (2020). Intraconal anatomy of the anterior ethmoidal neurovascular bundle: implications for surgery in the superomedial orbit. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 34 (3), 394–400. doi:10.1177/1945892420901630

Lung M. A. (1995). The role of the autonomic nerves in the control of nasal circulation. Biol. Signals 4 (3), 179–185. doi:10.1159/000109439

Luong A. U., Yong M., Hwang P. H., Lin B. Y., Gopi P., Mohan V., et al. (2024). Acoustic resonance therapy is safe and effective for the treatment of nasal congestion in rhinitis: a randomized sham-controlled trial. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 14 (5), 919–927.

Macias B. R., Patel N. B., Gibson C. R., Samuels B. C., Laurie S. S., Otto C., et al. (2020). Association of long-duration spaceflight with anterior and posterior ocular structure changes in astronauts and their recovery. JAMA Ophthalmol. 138 (5), 553–559. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.0673

Mader T. H., Gibson C. R., Manuel F. K. (2019). “Ophthalmologic concerns,” in Principles of clinical medicine for space flight. Editors M. R. Barratt, E. S. Baker, and S. L. Pool (New York, NY: Springer), 841–859.

Marshall-Goebel K., Laurie S. S., Alferova I. V., Arbeille P., Aunon-Chancellor S. M., Ebert D. J., et al. (2019). Assessment of jugular venous blood flow stasis and thrombosis during spaceflight. JAMA Netw. Open 2 (11), e1915011. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15011

Marshburn T. H., Lindgren K. N., Moynihan S. (2019). “Acute care,” in Principles of clinical medicine for space flight. Editors M. R. Barratt, E. S. Baker, and S. L. Pool (New York, NY: Springer), 457–480.

Maul X. A., Borchard N. A., Hwang P. H., Nayak J. V. (2019). Microcurrent technology for rapid relief of sinus pain: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical trial. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 9 (4), 352–356. doi:10.1002/alr.22280

Mehta V., Kramer D., Russin J., Liu C., Amar A. (2018). “Vagal nerve simulation,” in Neuromodulation., 999–1009.

Mermel L. A. (2013). Infection prevention and control during prolonged human space travel. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56 (1), 123–130. doi:10.1093/cid/cis861

Miranda S., Marchal S., Cumps L., Dierckx J., Kruger M., Grimm D., et al. (2023). A dusty road for astronauts. Biomedicines 11 (7), 1921. doi:10.3390/biomedicines11071921

Mittal R., Patel S., Galor A. (2021). Alternative therapies for dry eye disease. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 32 (4), 348–361. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000768

NASA (2016). Nasal congestion (space adaptation). HumanResearchWiki. Available at: https://humanresearchroadmap.nasa.gov/Evidence/medicalConditions/Nasal_Congestion_(Space_Adaptation).pdf (Accessed October 21, 2024).

Ng B. A., Ramsey R. G., Corey J. P. (1999). The distribution of nasal erectile mucosa as visualized by magnetic resonance imaging. Ear, Nose and Throat J. 78 (3), 159–166. doi:10.1177/014556139907800309

Oubre C. M., Pierson D. L., Ott C. M. (2016). “Microbiology,” in Space physiology and medicine: from evidence to practice. Editors A. E. Nicogossian, R. S. Williams, C. L. Huntoon, C. R. Doarn, J. D. Polk, and V. S. Schneider (New York, NY: Springer New York), 155–167.

Parazynski S. E., Hargens A. R., Tucker B., Aratow M., Styf J., Crenshaw A. (1991). Transcapillary fluid shifts in tissues of the head and neck during and after simulated microgravity. J. Appl. Physiol. 71 (6), 2469–2475. doi:10.1152/jappl.1991.71.6.2469

Pendolino A. L., Lund V. J., Nardello E., Ottaviano G. (2018). The nasal cycle: a comprehensive review. Rhinol. Online 1 (1), 67–76. doi:10.4193/rhinol/18.021

Phillips K. M., Roozdar P., Hwang P. H. (2022). Applications of vibrational energy in the treatment of sinonasal disease: a scoping review. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 12 (11), 1397–1412. doi:10.1002/alr.22988

Pilmanis A. A., Clark J. B. (2019). “Decompression-related disorders,” in Principles of clinical medicine for space flight. Editors M. R. Barratt, E. S. Baker, and S. L. Pool (New York, NY: Springer), 481–518.

Pondelis N., Dieckmann G. M., Jamali A., Kataguiri P., Senchyna M., Hamrah P. (2020). Infrared meibography allows detection of dimensional changes in meibomian glands following intranasal neurostimulation. Ocul. Surf. 18 (3), 511–516. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2020.03.003

Prisk G. K. (2019). Pulmonary challenges of prolonged journeys to space: taking your lungs to the moon. Med. J. Aust. 211 (6), 271–276. doi:10.5694/mja2.50312

Rudmik L., Smith T. L., Schlosser R. J., Hwang P. H., Mace J. C., Soler Z. M. (2014). Productivity costs in patients with refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 124 (9), 2007–2012. doi:10.1002/lary.24630

Sahin-Yilmaz A., Naclerio R. M. (2011). Anatomy and physiology of the upper airway. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 8 (1), 31–39. doi:10.1513/pats.201007-050RN

Sainio S., Blomgren K., Laulajainen-Hongisto A., Lundberg M. (2023). The effect of single kinetic oscillation stimulation treatment on nonallergic rhinitis. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 8 (2), 373–379. doi:10.1002/lio2.1048

Salzano F. A., Marino L., Salzano G., Botta R. M., Cascone G., D'Agostino Fiorenza U., et al. (2018). Microbiota composition and the integration of exogenous and endogenous signals in reactive nasal inflammation. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2724951. doi:10.1155/2018/2724951

Sampige R., Ong J., Waisberg E., Berdahl J., Lee A. G. (2024). The hypercapnic environment on the International Space Station (ISS): a potential contributing factor to ocular surface symptoms in astronauts. Life Sci. Space Res. 44, 122–125. doi:10.1016/j.lssr.2024.09.002

Schneider V. S., Charles J. B., Conkin J., Prisk G. K. (2016). “Cardiopulmonary system: aeromedical considerations,” in Space physiology and medicine (New York, NY: Springer), 227–244.

Shusterman E. M., E Gertner M., Carmen Choy A., Johnson J., J Friedman N. (2023). Evaluation of a novel external neuromodulation device (iCLEAR™) for the acute relief of rhinitis and rhinosinusitis symptoms. Archives Clin. Med. Case Rep. 07 (01). doi:10.26502/acmcr.96550582

Smith M. B., Chen H., Oliver B. G. G. (2024). The lungs in space: a review of current knowledge and methodologies. Cells 13 (13), 1154. doi:10.3390/cells13131154

Soler Z. M., Nguyen S. A., Salvador C., Lackland T., Desiato V. M., Storck K., et al. (2020). A novel device combining acoustic vibration with oscillating expiratory pressure for the treatment of nasal congestion. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 10 (5), 610–618. doi:10.1002/alr.22537

Spierings E. L. H. (2024). The efficacy of continuous non-inhaled intranasal carbon dioxide (CO2) in the abortive treatment of migraine: results from three randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials. Ann. Headache Med. J. doi:10.30756/ahmj.2024.12.02

Stanton-Hicks M. (2018). “Anatomy and physiology related to peripheral nerve stimulation,” in Neuromodulation, 723–727.

Stenger M. B., Macias B. R. (2020). Sinus space in outer space. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 146 (6), 578. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0274

Susaman N., Cingi C., Mullol J. (2021). “Is the nasal cycle real? How important is it?,” in Challenges in rhinology., 1–8.

Thornton W., Moore T. P., Pool S. L. (1987). Fluid shifts in weightlessness. Aviat. space, Environ. Med. 58 (9 Pt 2), A86–A90.

Thornton W. E., Hoffler G. W., Rummel J. A. (1974). “Anthropometric changes and fluid shifts,” in Proc. Of the skylab life sci. Symp., 2.

Torun M. T., Cingi C., Scadding G. K. (2021). “What is nasal hyperreactivity?,” in Challenges in rhinology, 15–23.

Unsal A. I. A., Basal Y., Birincioglu S., Kocaturk T., Cakmak H., Unsal A., et al. (2018). Ophthalmic adverse effects of nasal decongestants on an experimental rat model. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 81 (1), 53–58. doi:10.5935/0004-2749.20180012

Varghese M., Glaum M. C., Lockey R. F. (2010). Drug-induced rhinitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 40 (3), 381–384. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03450.x

Vernikos J. (2022). “Medications in microgravity: history, facts, and future trends,” in Handbook of space pharmaceuticals. Editors Y. V. Pathak, M. Araújo dos Santos, and L. Zea (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 165–178.

Watson M., Angjeli E., Orrick B., Baba S., Franke M., Holdbrook M., et al. (2017). Effect of the intranasal tear neurostimulator on meibomian glands. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.

Wirta D., Vollmer P., Paauw J., Chiu K. H., Henry E., Striffler K., et al. (2022). Efficacy and safety of OC-01 (varenicline solution) nasal spray on signs and symptoms of dry eye disease: the ONSET-2 phase 3 randomized trial. Ophthalmology 129 (4), 379–387. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.11.004

Wotring V. E. (2015). Medication use by U.S. Crewmembers on the international space station. FASEB J. 29 (11), 4417–4423. doi:10.1096/fj.14-264838

Wotring V. E., Smith L. K. (2020). Dose tracker application for collecting medication use data from international space station crew. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 91 (1), 41–45. doi:10.3357/AMHP.5392.2020

Keywords: sinus pain, nasal congestion, microgravity, countermeasure, neurostimulation, sinusitis, human spaceflight

Citation: Ax T, Zimmermann PH, Bothe TL, Barchetti K, de Paiva CS, March de Ribot F, Jensen SO and Millar TJ (2025) On the nose: nasal neurostimulation as a technology countermeasure for sinonasal congestion in astronauts. Front. Physiol. 16:1536496. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1536496

Received: 29 November 2024; Accepted: 21 January 2025;

Published: 14 February 2025.

Edited by:

Ronan Padraic Murphy, Dublin City University, IrelandReviewed by:

Mark Mims, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, United StatesIgnacio A. Cortés Fuentes, University of Chile, Chile

Copyright © 2025 Ax, Zimmermann, Bothe, Barchetti, de Paiva, March de Ribot, Jensen and Millar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Timon Ax, MjIwNzgwMTFAc3R1ZGVudC53ZXN0ZXJuc3lkbmV5LmVkdS5hdQ==

Timon Ax

Timon Ax Philipp H. Zimmermann3

Philipp H. Zimmermann3 Tomas L. Bothe

Tomas L. Bothe Karen Barchetti

Karen Barchetti Cintia S. de Paiva

Cintia S. de Paiva Francesc March de Ribot

Francesc March de Ribot Slade O. Jensen

Slade O. Jensen Thomas J. Millar

Thomas J. Millar