- 1Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- 2Laboratoire de Physique de l’Ecole normale supérieure, ENS, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Université Paris Cité, Paris, France

- 3Rudolf Peierls Centre for Theoretical Physics, Clarendon Laboratory, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 4Simons Center for Computational Physical Chemistry, New York University, New York, NY, United States

We study the connection between damage spreading, a phenomenon long discussed in the physics literature, and the coupling of Markov chains, a technique used to bound the mixing time. We discuss in parallel the Edwards–Anderson spin-glass model and the hard-disk system, focusing on how coupling provides bounds on the extension of the paramagnetic and liquid phases. We also work out the connection between path coupling and damage spreading. Numerically, the scaling analysis of the mean coupling time determines a critical point between fast and slow couplings. The exact relationship between fast coupling and disordered phases has not been established rigorously, but we suggest that it will ultimately enhance our understanding of phase behavior in disordered systems.

1 Introduction

Monte Carlo simulations based on Markov chains [36, 37] play an important role in the study of complex systems in physics and other sciences. In a given sample space, Markov chains perform random walks that, in their large-time steady state, visit configurations according to a prescribed stationary distribution (often the Boltzmann distribution). At early times, in contrast, after its start from a given initial configuration, each Markov chain samples different time-dependent distributions. The characterization of convergence (that is, of the mixing timescale [39] for approaching the stationary distribution) is of greatest importance as, by definition, convergence is required for sampling from the prescribed distribution and for estimating mean values of observables (pressure, specific heat, and internal energy) as running averages. Moreover, the mixing timescale by itself carries important information on the sampling problem. In a physics context, the sudden slowdown of mixing and relaxation times (without reference to any observable) often indicates a phase transition. Well-known examples are the slowdown of the Glauber dynamics at the paramagnetic–ferromagnetic transition in the Ising model [22, 41], as well as the glass transition, which is defined through the slowdown of relaxation processes (although it is not of thermodynamic origin). The spin-glass transition is believed to be signaled by a stark increase in the relaxation times at low temperatures [23]. In addition, in certain local Monte Carlo algorithms for particle systems, fast mixing (in a way that we will discuss later) is only possible in the liquid phase [32], so a statement about thermodynamic phases is obtained from an analysis of mixing times without invoking observables. However, establishing mixing and relaxation times can be an arduous task, both in practice and in theory.

As convergence sets in, samples and empirical mean values (running averages) become independent of initial configurations. Much stronger than mere independence, samples can actually become identical for two (or more) different initial configurations. This phenomenon, called coupling, is a focus of the present article. A coupling is a bivariate stochastic process that starts from two far-away initial configurations at time

Figure 1. Coupling for the random walk on a path graph (arrows point into the three directions with equal probabilities, and those leaving the graph are replaced by straight arrows). Left: Classic coupling: the two random walks advance independently until they merge at

The path-coupling approach [13] attempts to bound the global coupling time through an analysis that is local in both time and space. The two far-away initial configurations are imagined as end points of a “path” of many configurations. Configurations that are connected on the path are neighbors in the sample space with respect to a given metric. For the one-dimensional random walk, the metric may correspond to the Euclidean distance (see the lhs of Figure 1). For Ising systems, the metric could be the Hamming distance: neighboring configurations differ by only one spin. Similarly, for low-density systems of

This article presents a unified description of coupling and damage spreading, using spin-glass and hard-sphere models as examples. In Section 2, we provide common definitions, discuss theoretical foundations, and explore the connection between coupling and mixing, as well as the relationship between the aforementioned path coupling and damage spreading. We also introduce the scaling approach to phase transitions that we later apply to the coupling phenomenon. Section 3 is dedicated to spin glasses. We discuss rigorous results and the generally accepted theoretical framework for the spin-glass model introduced by Edwards and Anderson. Additionally, we explore path coupling and damage spreading for this model. We further apply the scaling analysis to its mean coupling time, which suggests a phase transition between fast and slow couplings. Section 4 addresses the hard-sphere model, for which we can generally transpose all the theoretical approaches of Section 3. The conclusions of our work are presented in Section 5.

2 Theoretical foundations

In this section, we discuss some fundamentals of Markov chains and first concentrate on the connection between the convergence of a Markov chain expressed through its mixing time and any of its couplings (Section 2.1). The special case of “monotone” coupling, which we also address, has important consequences for the ferromagnetic Ising model, although it does not apply to spin-glass models or to hard spheres in more than one dimension [49]. We then discuss damage spreading in terms of path coupling (Section 2.2). We will discuss the intimate relationship between a global view on coupling and a purely local view, which only surveys configurations that differ minimally. We finally discuss in Section 2.3 the scaling approach to coupling that later will be shown to apply both to spin glasses and to hard spheres.

2.1 Mixing, coupling, and monotone coupling

We consider a Markov chain with samples

Here,

For a given transition matrix

The bivariate process that updates the two copies

so that the transition matrix of the coupled Markov chain, which acts on two copies of the sample space

Couplings can take a variety of forms. The “classic” coupling performs two statistically independent Markov chains until, by accident, they couple, from when on they are glued together:

(see the lhs of Figure 1). At the coupling time

Transition matrices, as the ones in Equation 2, are implemented in Monte Carlo algorithms with the use of random elements, that is, one or several random numbers for selecting a particle or a spin, for choosing a move, and for accepting or rejecting it, etc. For example, the move from

as it must reproduce the transition matrix

The connection between mixing times and coupling times is as follows ([39], corollary 5.3):

where

A special class of couplings for which the inequality of Equation 3 can be tight (up to logarithms) requires the concept of monotonicity. In monotone couplings, there exists a partial ordering “

With Equation 3, there are thus upper and lower bounds for the monotone coupling time in terms of the mixing time, and the two agree up to a logarithm. For a monotone coupling with extremal elements, one must only survey their evolution, which will bracket all other configurations (see the rhs of Figure 1). Full surveys are possible in other cases [15], but the upper bound in Equation 4 is then often lost.

2.2 Path coupling and damage spreading

We can consider families of Markov chains that correspond to physical systems with size

As mentioned in the introduction, we may imagine the worst-case initial configurations

The path-coupling analysis that is local in sample space and in time yet valid uniformly for any pair of neighboring configurations yields a rigorous global fast-coupling bound. We will discuss the limiting temperature

The path-coupling analysis provides a justification for “damage spreading,” which has been extensively studied for spin systems in the physics literature, with the random-share coupling. As in path coupling, two neighboring initial configurations

2.3 From rigorous to non-rigorous approaches to coupling, scaling approach results

The coupling time in Equation 3 that allows bounding the mixing time follows the worst-case pair of starting configurations,

We use the partial-survey approximation to evaluate the mean coupling time

Assuming that, as

where

with a positive constant

3 Coupling in spin glasses

This section examines the coupling in the Edwards–Anderson model [23] of spin glasses, focusing on the dynamical properties of its Glauber dynamics. We first review known exact results on the thermodynamics of the model in finite dimensions (Section 3.1), followed by an analysis of path coupling and numerical calculations (Section 3.2). Finally, we discuss the physical significance of these findings (Section 3.3).

The Edwards–Anderson model describes

where

We consider two versions of the heat-bath algorithm, namely, random updates and parallel updates. For the random updates, at each time step, starting from a configuration

The classic coupling of Equation 2, applied to the heat-bath algorithm with the random updates, randomly chooses two spins

For the random-share coupling, the heat-bath algorithm for the random update uses a source of randomness

In short, the randomness

where the local field is

For the parallel update on a bipartite lattice, the randomness

The update is performed in two half steps on the two sub-lattices, as described earlier. The coupling corresponding to Equation 7 is monotone only for the ferromagnetic case

3.1 Spin glasses: from rigorous results to numerical simulations

From a mathematical perspective, the fact that the interactions

Mathematically rigorous results for the Edwards–Anderson model in finite dimensions are very few. In systems with random interactions, local regions may exhibit low probabilities but strong correlations, leading to anomalous singularities in the free energy and divergences in high-temperature expansions. In a specific random system, the existence of this type of singularity has been mathematically proven and is known as the Griffiths singularity [29]. This singularity emerges at the phase transition temperature when the random interactions are assumed to be uniform. In the Edwards–Anderson model, the Curie temperature of the ferromagnetic Ising model (with all

Early numerical studies [12, 42] on domain-wall energies at zero temperature, though limited to small system sizes, were the first to propose the existence of a finite-temperature spin-glass transition in three dimensions and the absence of such a transition in two dimensions. These findings were subsequently strengthened by exact algorithms in two dimensions and more sophisticated heuristic algorithms [10], which allowed for larger system sizes and more accurate results. Following them, local Monte Carlo methods, particularly those using the heat-bath algorithm, played a crucial role in confirming these conclusions. These Monte Carlo studies provided direct evidence for a finite-temperature transition in three dimensions [7, 8, 46, 47] and the absence of such a transition in two dimensions [7, 34]. While neither has been proven rigorously, the fact that the ground state of the two-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model can be computed in a time polynomial in

Damage spreading in spin-glass systems was found as a dynamical anomaly in early numerical simulations [14, 18], which showed that it occurs at temperatures higher than the spin-glass transition temperature suggested by other studies. However, it remained unclear whether the anomaly was related to the spin glass transition itself or to the Griffiths singularity. The connection between damage spreading and coupling, which is the focus of this article, was recognized in Ref. [4].

3.2 From path coupling to scaling plots

In the finite-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model, we now consider the random-share coupling for the heat-bath algorithm of Equation 7. To establish coupling, we consider two arbitrary spin configurations as initial states of the two Markov chains and apply the path-coupling argument of Section 2.2. The two configurations differ in at most

Let

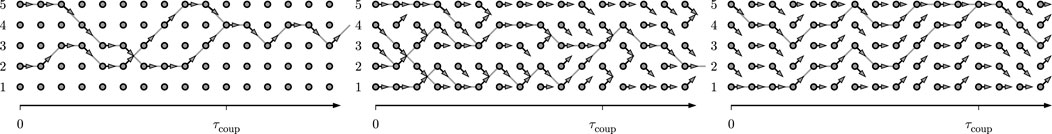

Figure 2. Left: Two spin configurations,

With probability

If

and equivalently,

For

We now numerically evaluate the mean coupling time of the finite-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model in both two and three dimensions in view of the scaling analysis discussed in Section 2.3. The mean coupling time of the two-dimensional model was already evaluated under a random update rule, and it has been demonstrated that a dynamical phase transition occurs in which the size dependence of the coupling time qualitatively changes [4], confirming earlier results [14]. The mean coupling time results presented below are evaluated using the partial-survey approximation with the number

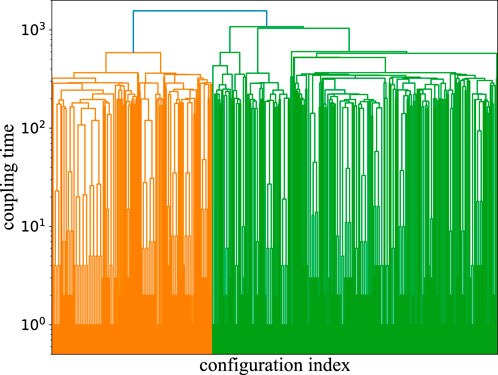

Figure 3. Dendrogram of configurations in the partial-survey approximation for the three-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model with parallel updates at

All the figures shown below represent results averaged over 4,096 realizations of interactions, independent of

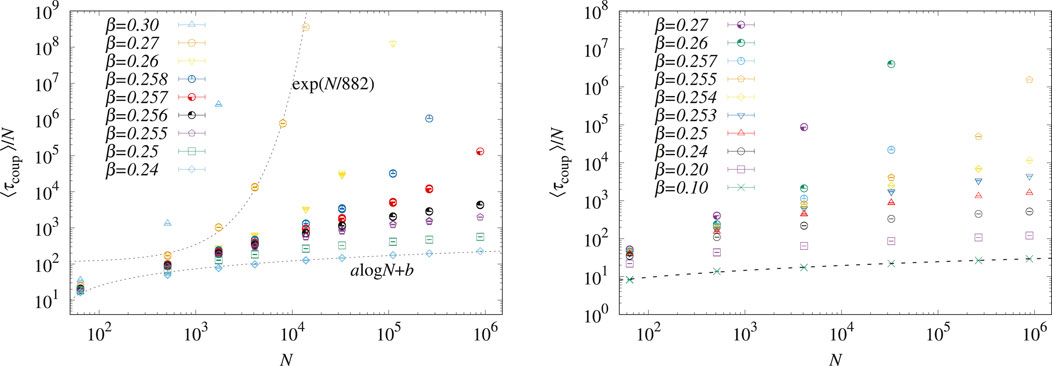

Figure 4. System-size

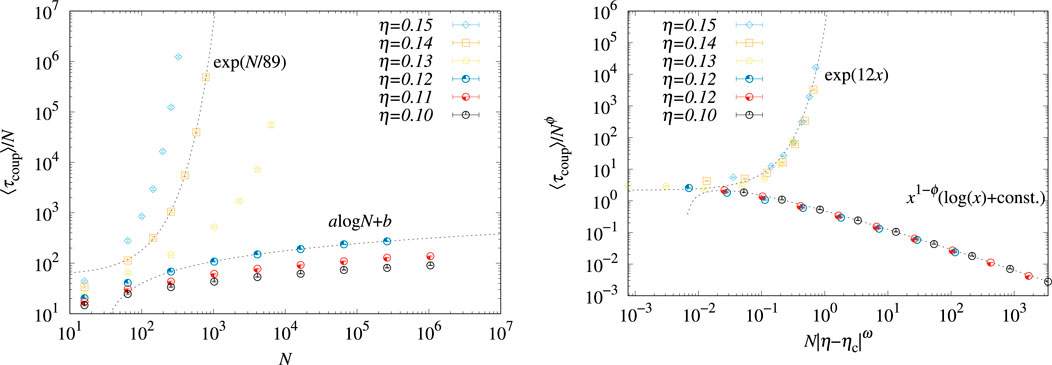

Figure 5 presents finite-size scaling plots of the mean coupling time for the three-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model, comparing both the parallel and random updates. The plot demonstrates that the scaling works well when the appropriate scaling parameters are chosen. This is consistent with the above argument that the transition temperatures,

Figure 5. Finite-size scaling plot of the mean coupling time in the three-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model. Left: Parallel updates (

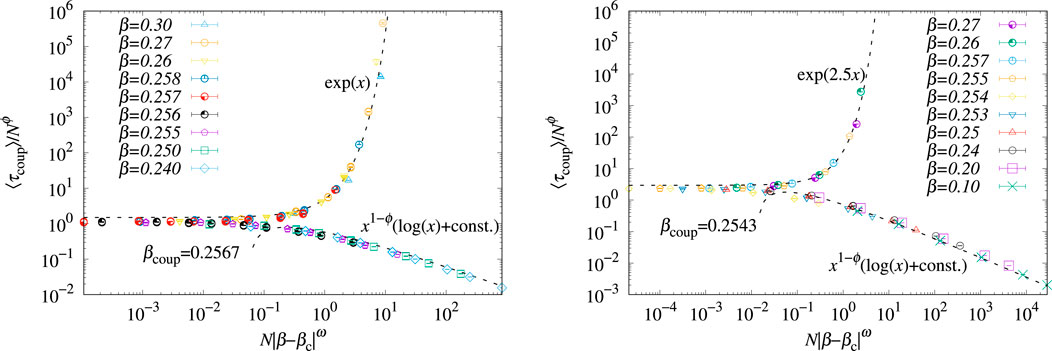

An analogous scaling analysis for the two-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model is shown in Figure 6. The left panel is the analysis result of our own numerical simulations using the sublattice parallel update, while the right panel presents the scaling analysis based on numerical data using the random update from [4]. In both cases, the scaling is consistent with a phase transition in the mean coupling time. As observed in the three-dimensional model,

Figure 6. Finite-size scaling plot of the mean coupling time in the two-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model. Left: Parallel update (our simulations). The obtained parameters are

3.3 Path coupling and damage spreading for spin glasses

Table 1 summarizes the key temperatures discussed in previous sections, including

Table 1. Spin-glass transition and coupling temperatures for the Edwards–Anderson model in two and three dimensions.

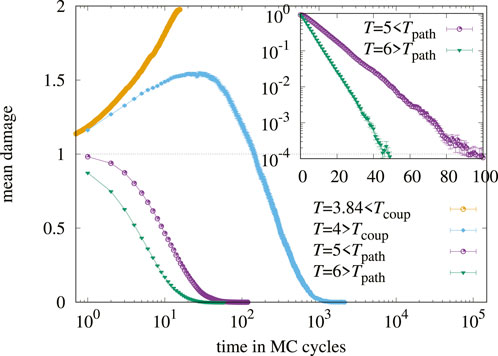

On the one hand, path coupling demonstrates that above

Figure 7. Damage evolution over time for two states differing by a Hamming distance of 1 as initial conditions in random updates of the three-dimensional Edwards–Anderson model. The size is

4 Coupling in hard spheres

In this section, we examine coupling for the hard-sphere system of statistical mechanics. For concreteness, we concentrate on the two-dimensional hard-disk model, which was the object of the historically first study using Markov chains [43]. The model has created an unabating series of works in mathematics, physics, and chemistry [40]. After an introduction to the model and to the Metropolis algorithm [35] that we will mostly consider, we review the very few known exact results on the model (Section 4.1) and then move on to the analysis of path coupling (Section 4.2) and to numerical calculations leading up to our scaling analysis. We finally discuss, following Ref. [32], what, precisely, the behavior of the algorithm teaches us about the physics of the hard-disk model (Section 4.3).

The model describes

where, for simplicity, we have omitted the Cartesian

We consider the “global” Metropolis algorithm: At each time step, and starting from a configuration

Here, the new position is chosen within a square-shaped periodic window of length

The random-share coupling for the global Metropolis algorithm uses the following random element:

This coupling has been considerably refined [31, 32].

4.1 Rigorous results for the thermodynamics of hard spheres

Rigorous results on hard-disk (and hard-sphere) models are very few. It is known that the close-packing density

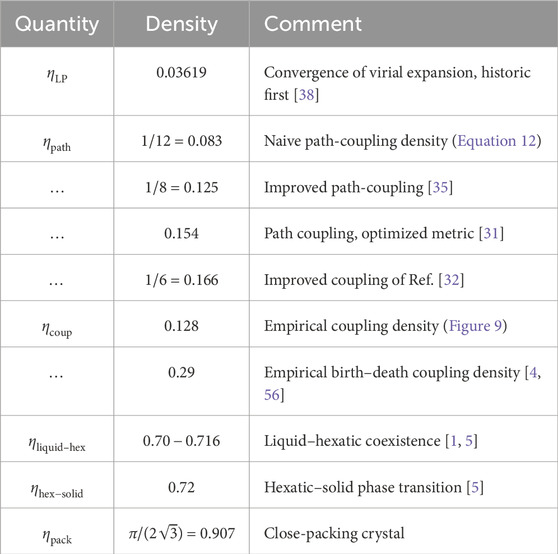

Table 2. Densities in the hard-disk system (see Equation 1 of Ref. [40]) for common definitions of densities). The homogeneous liquid phase empirically extends to a density of 0.70. The homogeneous hexatic phase is from 0.716 to 0.72. The density range from 0.70 to 0.716 corresponds to phase separation.

4.2 Path coupling and scaling plots for hard disks

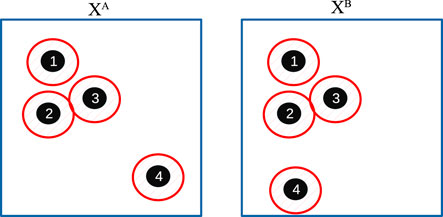

We now consider path coupling for hard disks, using the random map based on Equation 9 and a Hamming metric that counts the number of different disk positions in any two configurations. Let

Figure 8. Hard-disk configurations, differing only in disk

On the other hand, the Hamming distance can be increased from 1 to 2 if a disk different from

where the factor

Again, for

It follows [13] that the Hamming distance between configurations

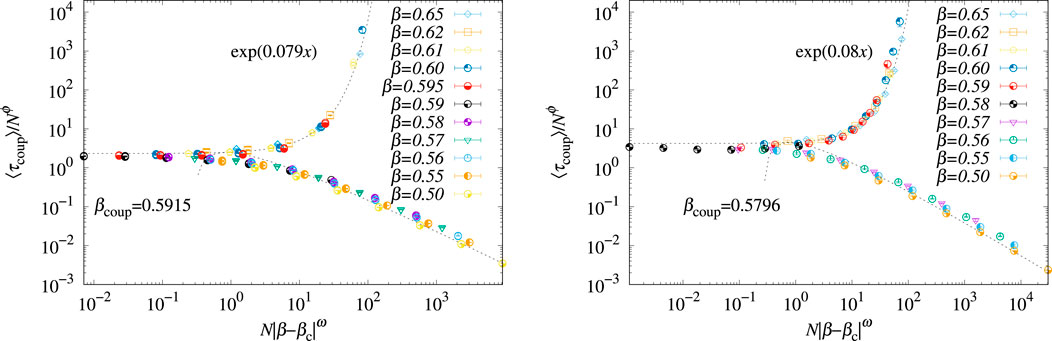

As with the Edwards–Anderson model, we now analyze the mean coupling time of the two-dimensional hard-disk model under the global Metropolis algorithm with the random-share coupling of Equation 9. In this case, we reanalyze the data obtained in Ref. [4], which we replot on the lhs of Figure 9. The analogous scaling ansatz again provides an excellent fit of the data. The critical exponents do not differ significantly from those found in the Edwards–Anderson model, suggesting the possibility of some underlying universality. However, uncovering the intricate physical picture behind this similarity remains an open question for future research. It should be noted that these critical exponents are not directly related to the critical phenomena of physical systems in the conventional sense. Rather, they characterize the “phase transition” in computational algorithms associated with the coupling of Markov chains. From an algorithmic perspective, these exponents are of significant interest as they provide insight into the inherent challenges in achieving fast coupling.

Figure 9. Left: System-size dependence of the mean coupling time at various densities in two-dimensional hard disks (data from Ref. [4]). Right: Finite-size scaling plot of the coupling time with parameters

4.3 Advanced hard-disk couplings, physical implications

The coupling approach to the hard-disk system has been intensely studied in recent years, and the random-share coupling of Equation 9 only provides the simplest possible choice. A number of refined couplings have been proposed. The one proposed in Ref. [35] moves disks differently for the configuration

The crucial connection between fast coupling (thus, fast mixing) and physical ordering was made for the hard-sphere case in Ref. [32], where it was proven that

5 Conclusion

In this article, we have discussed the computational aspects of two of the most challenging models in statistical physics, namely, the Edwards–Anderson model and the hard-disk model. In both these models, there are almost no rigorous results about the phase transitions in non-trivial physical dimensions, that is, above two dimensions for the spin model and above one dimension (away from close packing) for the particle system. Further connections are that the computational algorithms are mostly derivatives of the local-move heat-bath or Metropolis algorithm in both cases. Cluster algorithms have been developed for both systems [21, 34], but they have not really been useful in the physically interesting dimensions. Finally, the two models are united by the fact that they are truly challenging in their physical interpretation: For the Edwards–Anderson model, for a long time, even empirically, there was only a very rough agreed-on value of the transition temperature from the high-temperature paramagnetic phase, which was considerably sharpened in recent times only (see Table 1). No agreement has been reached on the nature of the low-temperature phase. For the hard-disk model, the now agreed-on transition scenario [5] was proposed only a decade ago, after more than 50 years of intense simulation. In that model, even the simplest algorithm, the local Metropolis algorithm, faces extreme challenges, as its irreducibility and ergodicity cannot be guaranteed in the constant-volume ensemble [11, 33].

In this context, the coupling approach provides an interesting yet incomplete view of the high-temperature/low-density phases. In the Edwards–Anderson model, one can easily establish the existence of a path-coupling temperature (see Equation 8), which we think provides a rigorous upper bound for the extension of the paramagnetic phase. For the hard-disk model, the program has been followed through completely, and the coupling result is the currently best lower bound for the extension of the liquid phase. It is fascinating how a result on the speed of a Monte Carlo algorithm can be derived from the behavior of two Markov chains (that is, from coupling) and can then be turned into a statement on the phase behavior. This fascination was sensed early on in the literature on damage spreading that, as we discussed, naturally connects to the path-coupling approach.

Damage spreading has created an extensive literature in physics, but, as we pointed out, that literature has concentrated on the specific random-share protocol, which gives the very low bounding density of Equation 12 when translated to the hard-disk context. In particle systems, there has been much progress from improved couplings and optimized metrics (see Table 2), which we hope can be ported to spin glasses and, more generally, to disordered systems. It would be interesting to see whether our scaling approach can be applied to these more advanced couplings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

KH: writing–original draft and writing–review and editing. WK: writing–original draft and writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by a grant from the Simons Foundation (Grant 839534, MET). This work was also supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. 23H01095, and JST Grant Number JPMJPF2221. This research was conducted within the context of the International Research Project “Non-Reversible Markov chains, Implementations and Applications.”

Acknowledgments

We thank J. L. Lebowitz for an inspiring discussion. KH would like to thank the Ecole Normale Supérieure, ENS, for their kind hospitality during a research stay, which provided a productive environment and variable support for the completion of this work. The authors thank the Supercomputer Center, the Institute for Solid State Physics, and the University of Tokyo for the use of the facilities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Alder BJ, Wainwright TE. Phase transition in elastic disks. Phys Rev (1962) 127:359–61. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.127.359

2. Aldous D, Diaconis P. Shuffling cards and stopping times. The Am Math Monthly (1986) 93:333–48. doi:10.2307/2323590

3. Baity-Jesi M, Baños RA, Cruz A, Fernandez LA, Gil-Narvion JM, Gordillo-Guerrero A, et al. Critical parameters of the three-dimensional Ising spin glass. Phys Rev B (2013) 88:224416. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.88.224416

4. Bernard EP, Chanal C, Krauth W. Damage spreading and coupling in Markov chains. EPL (Europhysics Letters) (2010) 92:60004. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/92/60004

5. Bernard EP, Krauth W. Two-step melting in two dimensions: first-order liquid-hexatic transition. Phys Rev Lett (2011) 107:155704. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.155704

6. Berretti A. Some properties of random Ising models. J Stat Phys (1985) 38:483–96. doi:10.1007/BF01010473

7. Bhatt RN, Young AP. Search for a transition in the three-dimensional ±J Ising spin-glass. Phys Rev Lett (1985) 54:924–7. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.924

8. Bhatt RN, Young AP. Numerical studies of Ising spin glasses in two, three, and four dimensions. Phys Rev B (1988) 37:5606–14. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.37.5606

9. Bieche L, Uhry JP, Maynard R, Rammal R. On the ground states of the frustration model of a spin glass by a matching method of graph theory. J Phys A: Math Gen (1980) 13:2553–76. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/13/8/005

10. Boettcher S. Stiffness of the Edwards-Anderson model in all dimensions. Phys Rev Lett (2005) 95:197205. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.197205

11. Böröczky K. Über stabile Kreis-und Kugelsysteme. Ann Univ Sci Budapest Eötvös Sect Math (1964) 7:79–82.

12. Bray AJ, Moore MA. Lower critical dimension of Ising spin glasses: a numerical study. J Phys C: Solid State Phys (1984) 17:L463–8. doi:10.1088/0022-3719/17/18/004

13. Bubley R, Dyer M. Path coupling: a technique for proving rapid mixing in Markov chains. In: 2013 IEEE 54th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Los Alamitos, CA, USA: IEEE Computer Society (1997). 223.

14. Campbell I, de Arcangelis L. On the damage spreading in Ising spin glasses. Physica A: Stat Mech its Appl (1991) 178:29–43. doi:10.1016/0378-4371(91)90073-l

15. Chanal C, Krauth W. Renormalization group approach to exact sampling. Phys Rev Lett (2008) 100:060601. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.060601

16. Chanal C, Krauth W. Convergence and coupling for spin glasses and hard spheres. Phys Rev E (2010) 81:016705. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.81.016705

17. Creutz M. Monte Carlo study of quantized SU(2) gauge theory. Phys Rev D (1980) 21:2308–15. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.21.2308

18. Derrida B, Weisbuch G. Dynamical phase transitions in 3-dimensional spin glasses. EPL (1987) 4:657–62. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/4/6/004

19. Ding J, Lubetzky E, Peres Y. The mixing time evolution of Glauber dynamics for the mean-field Ising model. Commun Math Phys (2009) 289:725–64. doi:10.1007/s00220-009-0781-9

20. Doeblin W. Exposé de la Théorie des chaînes simples constantes de Markoff à un nombre fini d’états. Rev Math Union Interbalkanique (1938) 2:77.

21. Dress C, Krauth W. Cluster algorithm for hard spheres and related systems. J Phys A: Math Gen (1995) 28:L597–L601. doi:10.1088/0305-4470/28/23/001

22. Dyer M, Sinclair A, Vigoda E, Weitz D. Mixing in time and space for lattice spin systems: a combinatorial view. Random Struct Algorithms (2004) 24:461–79. doi:10.1002/rsa.20004

23. Edwards SF, Anderson PW. Theory of spin glasses. J Phys F: Metal Phys (1975) 5:965–74. doi:10.1088/0305-4608/5/5/017

25. Fröhlich J, Imbrie JZ. Improved perturbation expansion for disordered systems: beating Griffiths singularities. Commun Math Phys (1984) 96:145–80. doi:10.1007/BF01240218

26. Geman S, Geman D. Stochastic relaxation, Gibbs distributions, and the Bayesian restoration of images. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell (1984) PAMI-6:721–41. doi:10.1109/tpami.1984.4767596

27. Glauber RJ. Time-dependent statistics of the Ising model. J Math Phys (1963) 4:294–307. doi:10.1063/1.1703954

28. Griffeath D. A maximal coupling for Markov chains. Z fr̈ Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie Verwandte Gebiete (1975) 31:95–106. doi:10.1007/bf00539434

29. Griffiths RB. Nonanalytic behavior above the critical point in a random Ising ferromagnet. Phys Rev Lett (1969) 23:17–9. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.23.17

30. Hasenbusch M, Pelissetto A, Vicari E. Critical behavior of three-dimensional Ising spin glass models. Phys Rev B (2008) 78:214205. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.78.214205

31. Hayes TP, Moore C. Lower bounds on the critical density in the hard disk model via optimized metrics. arXiv:1407.1930 (2014). doi:10.48550/arXiv.1407.1930

32. Helmuth T, Perkins W, Petti S. Correlation decay for hard spheres via Markov chains. The Ann Appl Probab (2022) 32. doi:10.1214/21-aap1728

33. Höllmer P, Noirault N, Li B, Maggs AC, Krauth W. Sparse hard-disk packings and local Markov chains. J Stat Phys (2022) 187:31. doi:10.1007/s10955-022-02908-4

34. Houdayer J. A cluster Monte Carlo algorithm for 2-dimensional spin glasses. The Eur Phys J B - Condensed Matter Complex Syst (2001) 22:479–84. doi:10.1007/PL00011151

35. Kannan R, Mahoney MW, Montenegro R. Rapid mixing of several Markov chains for a hard-core model. Proc 14th Annual ISAAC (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg), Lecture Notes Computer Sci (2003) 663–75. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-24587-2_68

37. Landau D, Binder K. A guide to Monte Carlo simulations in statistical physics. Cambridge University Press (2013).

38. Lebowitz JL, Penrose O. Convergence of virial expansions. J Math Phys (1964) 5:841–7. doi:10.1063/1.1704186

39. Levin DA, Peres Y, Wilmer EL. Markov chains and mixing times. American Mathematical Society (2008).

40. Li B, Nishikawa Y, Höllmer P, Carillo L, Maggs AC, Krauth W. Hard-disk pressure computations—a historic perspective. J Chem Phys (2022) 157:234111. doi:10.1063/5.0126437

41. Martinelli F. Lectures on Glauber dynamics for discrete spin models. In: P Bernard, editor Lectures on Probability Theory and Statistics: Ecole d’Eté de Probabilités de Saint-Flour XXVII - 1997. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (1999). p. 93–191.

42. McMillan WL. Domain-wall renormalization-group study of the three-dimensional random Ising model. Phys Rev B (1984) 30:476–7. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.30.476

43. Metropolis N, Rosenbluth AW, Rosenbluth MN, Teller AH, Teller E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J Chem Phys (1953) 21:1087–92. doi:10.1063/1.1699114

44. Mezard M, Parisi G, Virasoro M. Spin glass theory and beyond. World Scientific (1986). doi:10.1142/0271

45. Nattermann T, Villain J. Random-field ising systems: a survey of current theoretical views. Phase Transitions (1988) 11:5–51. doi:10.1080/01411598808245480

46. Ogielski AT. Dynamics of three-dimensional Ising spin glasses in thermal equilibrium. Phys Rev B (1985) 32:7384–98. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.32.7384

47. Ogielski AT, Morgenstern I. Critical behavior of three-dimensional Ising spin-glass model. Phys Rev Lett (1985) 54:928–31. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.928

48. Propp JG, Wilson DB. Exact sampling with coupled Markov chains and applications to statistical mechanics. Random Structures and Algorithms (1996) 9:223–52. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-2418(199608/09)9:1/2<223::aid-rsa14>3.3.co;2-r

49. Randall D, Winkler P. Mixing points on an interval. In: C Demetrescu, R Sedgewick, and R Tamassia, editors. Proceedings of the seventh workshop on algorithm engineering and experiments and the second workshop on analytic algorithmics and combinatorics, ALENEX/ANALCO 2005. Vancouver, BC, Canada: SIAM (2005). p. 218–21.

50. Richthammer T. Lower bound on the mean square displacement of particles in the hard disk model. Commun Math Phys (2016) 345:1077–99. doi:10.1007/s00220-016-2584-0

51. Franz S, Parisi G, Virasoro MA. Interfaces and lower critical dimension in a spin glass model. J Phys France (1994) 4:1657–67. doi:10.1051/jp1:1994213

52. Sherrington D, Kirkpatrick S. Solvable model of a spin-glass. Phys Rev Lett (1975) 35:1792–6. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.35.1792

53. Stanley HE, Stauffer D, Kertész J, Herrmann HJ. Dynamics of spreading phenomena in two-dimensional Ising models. Phys Rev Lett (1987) 59:2326–8. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.2326

54. Talagrand M. Spin glasses: a challenge for mathematicians: cavity and mean field models. In: Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete. 3. Folge A Series of Modern Surveys in Mathematics. Springer (2003).

55. Thomas CK, Middleton AA. Exact algorithm for sampling the two-dimensional Ising spin glass. Phys Rev E (2009) 80:046708. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.80.046708

Keywords: spin glasses, hard-sphere model, Markov chains, coupling times, damage spreading, thermodynamic phase transitions, dynamic phase transitions

Citation: Hukushima K and Krauth W (2025) Damage spreading and coupling in spin glasses and hard spheres. Front. Phys. 12:1507250. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2024.1507250

Received: 07 October 2024; Accepted: 17 December 2024;

Published: 13 February 2025.

Edited by:

Federico Ricci-Tersenghi, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Victor Martin-Mayor, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, SpainAlexander Hartmann, University of Oldenburg, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Hukushima and Krauth. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Koji Hukushima, ay1odWt1c2hpbWFAZy5lY2MudS10b2t5by5hYy5qcA==

Koji Hukushima

Koji Hukushima Werner Krauth

Werner Krauth