94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Pharmacol., 22 December 2022

Sec. Neuropharmacology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1094351

This article is part of the Research TopicTranslational Advances in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and other Dementia: Molecular Mechanisms, Biomarkers, Diagnosis, and Therapies, Volume IIIView all 42 articles

Arunkumar Subramanian1†

Arunkumar Subramanian1† T. Tamilanban1*†

T. Tamilanban1*† Abdulrhman Alsayari2,3

Abdulrhman Alsayari2,3 Gobinath Ramachawolran4*

Gobinath Ramachawolran4* Ling Shing Wong5*

Ling Shing Wong5* Mahendran Sekar6*†

Mahendran Sekar6*† Siew Hua Gan7

Siew Hua Gan7 Vetriselvan Subramaniyan8

Vetriselvan Subramaniyan8 Suresh V. Chinni9,10

Suresh V. Chinni9,10 Nur Najihah Izzati Mat Rani11

Nur Najihah Izzati Mat Rani11 Nagaraja Suryadevara8

Nagaraja Suryadevara8 Shadma Wahab2,3

Shadma Wahab2,3The primary and considerable weakening event affecting elderly individuals is age-dependent cognitive decline and dementia. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the chief cause of progressive dementia, and it is characterized by irreparable loss of cognitive abilities, forming senile plaques having Amyloid Beta (Aβ) aggregates and neurofibrillary tangles with considerable amounts of tau in affected hippocampus and cortex regions of human brains. AD affects millions of people worldwide, and the count is showing an increasing trend. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the underlying mechanisms at molecular levels to generate novel insights into the pathogenesis of AD and other cognitive deficits. A growing body of evidence elicits the regulatory relationship between the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway and AD. In addition, the role of autophagy, a systematic degradation, and recycling of cellular components like accumulated proteins and damaged organelles in AD, is also pivotal. The present review describes different mechanisms and signaling regulations highlighting the trilateral association of autophagy, the mTOR pathway, and AD with a description of inhibiting drugs/molecules of mTOR, a strategic target in AD. Downregulation of mTOR signaling triggers autophagy activation, degrading the misfolded proteins and preventing the further accumulation of misfolded proteins that inhibit the progression of AD. Other target mechanisms such as autophagosome maturation, and autophagy-lysosomal pathway, may initiate a faulty autophagy process resulting in senile plaques due to defective lysosomal acidification and alteration in lysosomal pH. Hence, the strong link between mTOR and autophagy can be explored further as a potential mechanism for AD therapy.

Many individuals above 65 years of age tend to suffer from a general progressive neurodegenerative disorder called Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Scheltens et al., 2016). The disorder includes the formation of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) aggregates as a result of proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and, to date, has no effective treatment (Oddo et al., 2006). Age is the prime risk factor for the progression of AD, the prevalent type of dementia spreading across the world, where 40 million individuals are affected (Selkoe and Hardy, 2016), and the count is expected to triple by 2050 (Galvan and Hart, 2016).

In terms of genetics, AD-inherited patients show the presence of a mutated amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene with an autosomal dominant trait and mutated presenilin genes. Clinically, AD is also illustrated by cognitive impairment, overproduction of Aβ aggregates, and tau protein’s hyper-phosphorylation in many basic research studies. AD is a gradually progressive neurodegenerative disease prominently consisting of 1) neuritic senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) (Figure 1) 2) shrinkage of the hippocampus region, resulting in the accumulation of Aβ aggregates in the medial temporal lobe, and 3) neocortical structures of the affected human brain (De-Paula et al., 2012).

AD, an essential type of dementia, mainly affects various brain functions like behavior, thinking, and memory. These symptoms, in due course, increase the worsening of daily activities. Memory is lost when 1) crucial meetings are forgotten, 2) familiar tasks such as cooking, driving, writing, and speaking are disoriented, and 3) varied mood swings and withdrawal from relations and family happens (Breijyeh and Karaman, 2020). In addition, many risk factors are correlated with AD, making it a multifactorial disease (Figure 2).

Autophagy, defined as “self-eating,” is a self and systematic degradable process occurring within the cell for recycling cellular components like protein aggregates, misfolded proteins, and unwanted cell organelles (Glick et al., 2010; Fornai and Puglisi-Allegra, 2021). Recent studies on AD mainly focus on autophagy’s contribution to its pathology (Leidal et al., 2018; Aman et al., 2021; Pang et al., 2022). Like other cells, neurons can gather toxic substances/organelles during senescence and require autophagy activation to maintain cell homeostasis (Mariño et al., 2011).

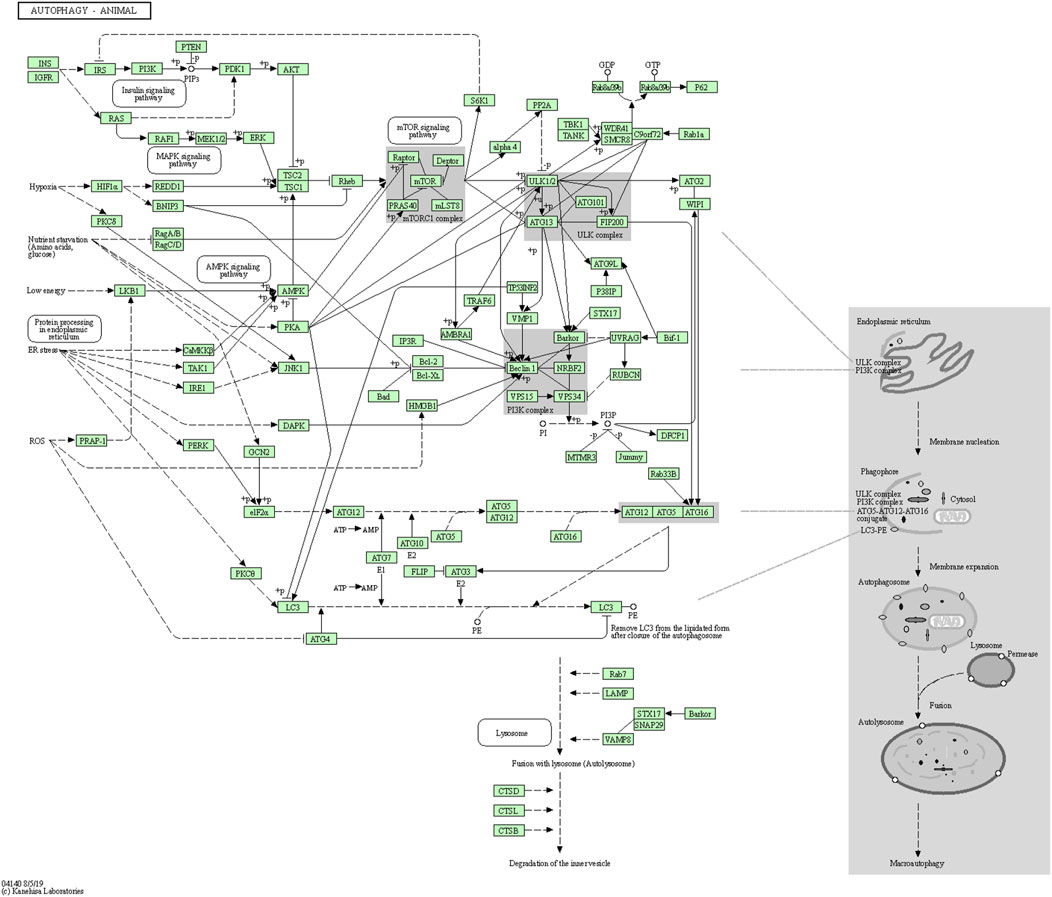

A recent study reported that autophagy-related genes, namely ATG18, ATG8a, and ATG1 in Drosophila melanogaster insect model, are down-regulated with age and neuron dysfunction (Zhang et al., 2013). The autophagic flux represents the complete dynamic steps of autophagy including autophagosome formation, maturation, fusion with lysosomes, and subsequent breakdown, followed by the release of macromolecules back into the cytosol (Klionsky, 2008). The autophagy pathway includes releasing various factors, proteins, and signaling molecules. It is associated with other signaling pathways like adenosine monophosphate protein kinase (AMPK), Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and insulin signaling. The pictorial representation of the autophagy pathway in Homo sapiens retrieved from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database is shown in Figure 3 (Kanehisa, 2000).

FIGURE 3. Autophagy pathway (KEGG Id: hsa04140), highlighting its association with the mTOR signaling pathway.

AD worsens with aging, expressing its symptoms and affecting many brain functions, among which cognitive dysfunction (loss of synapses) and memory loss are prominent (Scheltens et al., 2016). In AD, extracellular senile plaques have amyloid beta particles and intraneural NFT, constituting the major part of aggregated MAPT/Tau protein (Loera-Valencia et al., 2019). The focus on the defects of autophagic flux in AD will not only update the current monitoring methods but also provide visions for developing autophagy-related therapeutics for treating the disease. Through the mTOR signaling, beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptides are accumulated by altering APP metabolism and upregulating β and γ secretases while the mTOR inhibits autophagy function. Moreover, dysregulation of mTOR is allied with many human diseases, like cancer and neurological and metabolic diseases (Chong et al., 2010; Dazert and Hall, 2011; Meng et al., 2013), with more focus now shown on mTOR’s role in the AD’s pathology.

The mTOR is a member of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase-related family with conserved Ser/Thr protein kinase and can respond to environmental stimuli like nutrient concentration, energy state, and growth factors (Yoon, 2017). mTOR is significant for cell growth, metabolism, proliferation, protein translation, and autophagy. Several studies on AD pathology are supported by ample evidence, stressing the association between AD and mTOR signaling (Wang et al., 2014a). The present review is on the divergent mechanistic regulations of autophagy and mTOR proteins, the available inhibitors for mTOR, and how all these combined factors apply to AD’s treatment.

Autophagy is a highly conserved pathway for degrading long-lived intracellular proteins, protein aggregates, and organelles (e.g., mitochondrial) via lysosomes to maintain homeostasis under physiological conditions (Dikic and Elazar, 2018). Many studies have reported that altered autophagy is directly related to multiple chronic diseases, including AD. Inducing autophagy may therefore result in the removal of Aβ accumulations (Zhang et al., 2022) providing a beneficial effect in preclinical AD models, indicating that autophagy is a reliable tool for developing therapeutic compounds for AD treatment (Figure 4). Moreover, chaperone-mediated autophagy and mitophagy have also been associated with AD (Cuervo and Wong, 2014; Kerr et al., 2017).

The body of scientific evidence suggests the impact of defective mitophagy in the aggregation of faulty autophagosomal vacuoles. Calcium ion imbalance, altered pH, and increased oxidative stress play an important role in this faulty mitochondrial dysfunction mechanism leading to AD progression (Nixon et al., 2008; Nixon, 2013; Medina et al., 2015). Ashrafi et al. (2015) claimed the involvement of PINK1 and PARK2 genes in mitochondrial health maintenance. Mutations occurring in these genes may result in an impaired mitophagy process leading to the clustering of defective autophagosomal vacuoles (Ashrafi and Schwarz, 2015). Another study proposed that mutations in the PSEN1 gene might induce an altered autophagy/mitophagy pathway. This mutation can lead to reduced lysosomal hydrolase activity accelerating the lysosome alkalization resulting in AD (Coffey et al., 2014).

Alteration of the autophagy-lysosome pathway contributes to APP (Torres et al., 2012) and APP-CTFb degradation, overall leading to Aβ aggregate formation. This step also eventually inhibits MAPT/tau aggregates degradation (Inoue et al., 2012) which further induces neurodegeneration. Autophagy is critical in regulating inflammation, where autophagy inducers can also cause glial cells’ autophagy via neuron cross-talks (Zhang et al., 2022). Characterization of autophagy-lysosomes impairment in various AD stages, molecules, and genetic types may also pave the way to generate avenues for novel therapeutics.

In another in vitro model study, the overexpression of let-7b promoted Aβ1-40 to trigger the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR pathway in neuroblastoma (SK-N-SH) cells, subsequently inhibiting autophagy and promoting apoptosis (Ji et al., 2006). Some evidence also emphasizes that uncontrolled Aβ accumulations generated more neurotoxicity and progression of AD (Tomiyama et al., 1996). Investigation on Aβ neurotoxicity usually represents SK-N-SH cells and Aβ1-40 as the AD’s cell models (Muñoz and Inestrosa, 1999), thus suggesting that age-induced reduction in autophagy-related gene expression is interlinked with AD in the later stages (Pang et al., 2022). In AD cells, the removal of abnormal protein aggregates can be achieved by utilizing autophagy mechanisms (Metcalf et al., 2012).

Lysosomal acidification and the dysregulation of the V-ATPase complex are common metabolic interruptions associated with AD (Ward et al., 2016) (Colacurcio and Nixon, 2016). But, recent study findings reveal the defective acidification of autolysosomes may induce faulty autophagic build-up of Aβ in neurons (Lee et al., 2022). Therefore, autophagy-stimulating agents/drugs, like mTOR inhibition, remain a potential therapeutic agent for AD without altering the autophagy-lysosomal pathway.

mTOR is a 289-kD Ser/Thr multidomain protein with an FKBP12 binding and kinase domain which controls many physiological processes. mTOR coordinates the upstream signaling components such as glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3), growth factors, insulin, AMPK, and PI-3K/Akt (Ferrer et al., 2002; Griffin et al., 2005; Kaper et al., 2006; Gouras, 2013). AD pathogenesis depends on both the down- and upstream regions of mTOR signaling (Cai et al., 2015). Several research studies have highlighted the dysregulation of the mTOR pathway in other diseases like cancer and diabetes (Hsieh and Edlind, 2014) (Habib and Liang, 2014), cardiovascular disease (Chong et al., 2011; Yang and Ming, 2012), aging (Gharibi et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2014), neurodegenerative diseases (Jiang et al., 2013; Sarkar, 2013) as well as obesity (Martínez-Martínez et al., 2014). In fact, some reports stated that mTOR activation contributes to AD progression and interferes with the clinical manifestation and AD pathology (Paccalin et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2010).

Hyperactivated mTOR, the able cause of AD, is regulated with various upstream signaling cascades like GSK3, AMPK (PI3-K)/Akt, and IGF-1. It is also observed that many diseases like mitochondrial dysfunction, auto-immunity, and cancer affect these pathways, causing uncontrolled stimulation of mTOR and leading to tau protein hyperphosphorylation. The phenomenon leads to the formation of NFTs and paired helical filaments (PHFs), the characteristic symptom of AD. Additionally, Aβ plaques are also formed due to the direct inhibition of autophagy by mTOR activation, which induces tau protein hyperphosphorylation and mTOR activities, thus enhancing the advancement of AD (Mueed et al., 2019).

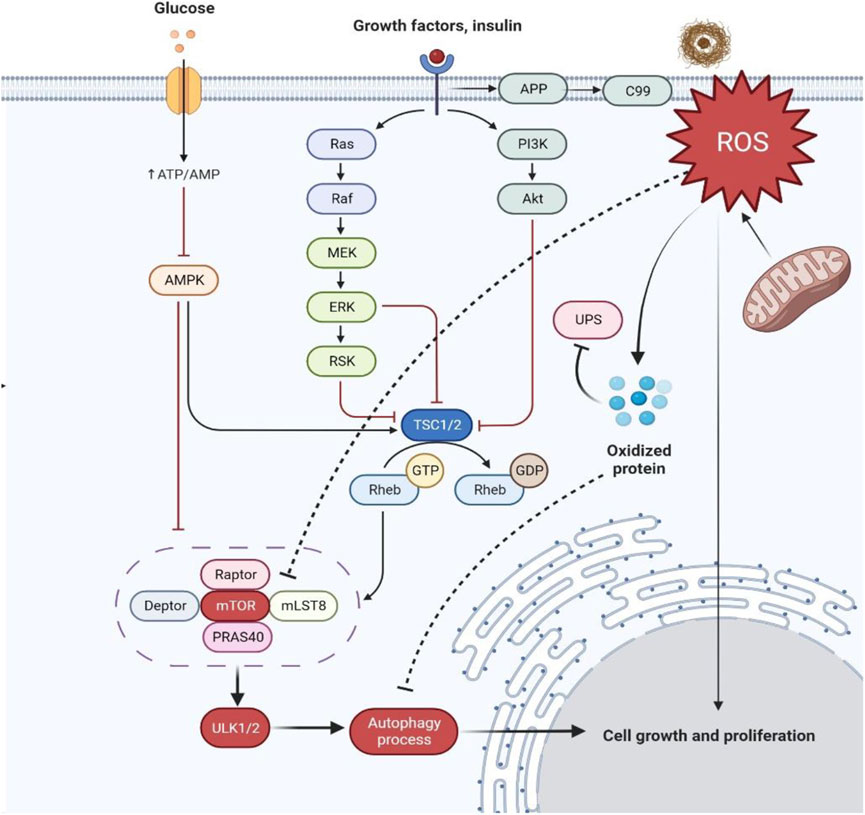

Furthermore, it was reported that mitochondrial and nuclear DNA oxidation in AD brains occur with increased levels of 8-oxo-2-dehydroguaninie, 5-hydroxyuracil, and 8-hydroxyadenine in temporal, frontal, and parietal lobes of AD brains (Santos et al., 2012; Perluigi et al., 2021). Likewise, in hippocampus regions of AD brains, heavy levels of 8-hydroxyguanine were also reported (Lovell and Markesbery, 2007; Siman et al., 2015) investigated the selective expression and toxicity of diseased tau by a viral vector approach in the mouse lateral perforant pathway to understanding the activity of rapamycin and its neuroprotective effect. Rapamycin was found to simultaneously inhibit mTOR protein kinase and stimulates autophagy (Siman et al., 2015). The study’s qualitative and quantitative histological findings and morphometric methods revealed a significant reduction in the disease’s symptomatic effects of tau in the perforant pathway upon chronic systematic rapamycin treatment. Henceforth, the progression in the early stages of AD can be addressed by lowering the tau toxicity effect (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Schematic representation of hyperactivation of mTOR in AD dysregulating insulin signaling and producing more oxidized proteins. Abbreviations: APP, Amyloid precursor protein; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; UPS, Ubiquitin-proteasome system; P13K, Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; Akt, Ak strain transforming; Ras, Rat sarcoma; Raf, Rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; MEK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase; ERK, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; RSK, Ribosomal S6 kinase; TSC1/2, Tuberous sclerosis proteins 1/2; GTP, Rheb, Ras homolog enriched in the brain; GDP, Guanosine diphosphate; mTOR, Mammalian target of rapamycin; mLST8, Mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein eight; PRAS40, Proline-rich AKT substrate of 40 kDa; ULK1/2, Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ATP/AMP, Adenosine triphosphate/adenosine monophosphate.

Under controlled conditions, decreased levels of free radical or reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Aβ aggregates coordinate stress responses like ubiquitin protease system (UPS), autophagy, and unfolded protein response (UPR) and remove damaged cell organelles and other compounds. Under diseased conditions, ROS are overproduced for the control of protein quality leading to the formation of more oxidized proteins because of protein dysfunction and also leading to the dysregulation of insulin signaling (Tramutola et al., 2015; Höhn et al., 2020).

During the persistent circumstance of AD pathology, the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex (mTORC1) regulation is lost, resulting in aggregate formation inside the cell. Indeed, the levels of eukaryotic Initiative Factor 4E (eIF4E) (Li et al., 2005), phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1) (Li et al., 2005), ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 (p70S6K) (Sun et al., 2013), Akt activation (Griffin et al., 2005) and mTOR phosphorylation (at Ser248) are considerably increased in AD-affected brains. These alterations correlate with Braak staging and tau pathology resulting in protein translation disorder. The cognitive decline during AD and mTOR hyperactivation co-exists (Caccamo et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2013). In addition, the levels of phosphate and tensin homologue (PTEN) immunoreactive neurons are decreased in the temporal cortex and hippocampus regions of AD-affected brains showing a negative correlation with senile plaque and NFT formations (Griffin et al., 2005).

The PI3K/Akt signaling is attenuated by PTEN, followed by the dephosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), resulting in the Akt signal hyper-activation to trigger the mTORC1 activity further. This phenomenon leads to the inhibition of autophagy, contributing to Aβ clearance. However, the chances of insulin desensitization need to be checked, which further interrupts Akt activation, as reported in the post-mortem AD brain (Shafei et al., 2017).

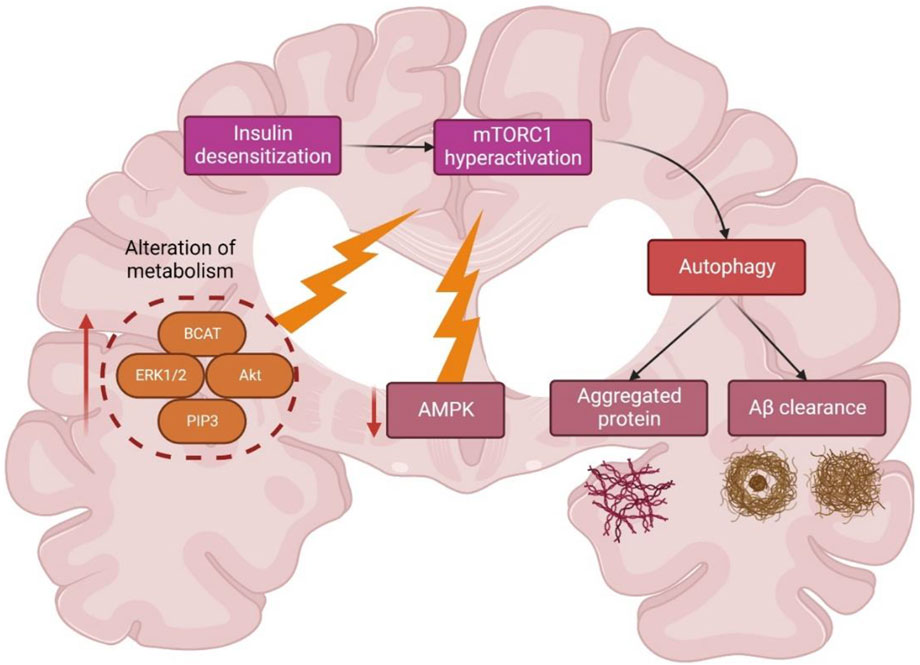

Insulin activation of mTORC1 triggers the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK)1/2 pathway, which is upregulated in AD brain and cell models (Morales-Corraliza et al., 2016). During AD, Aβ aggregates worsened mTORC1 signaling due to 40 kDa proline-rich Akt substrate phosphorylation (PRAS40), leading to mTORC1 activity enhancement and autophagy inhibition (Caccamo et al., 2011; Tramutola et al., 2015) (Figure 6). A study (Caccamo et al., 2010) showed the significance of future targets for neuron health regulation by using drug molecules like rapamycin which can inhibit mTOR and induce autophagy by alleviating the accumulation of Aβ peptides. Nevertheless, the mTORC1 upstream region is interlinked with other mechanisms like glucose metabolism, insulin resistance, and AD pathology, thus complicating further studies (Shafei et al., 2017).

FIGURE 6. Schematic representation of different metabolic regulations of autophagy and mTOR in Alzheimer’s disease. Abbreviations: BCAT, Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase; ERK1/2; extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; Akt, Ak strain transforming; PIP3, Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1.

In the brains affected with AD, autophagy’s function is altered, leading to the deposition of many toxic proteins. There are many genes, factors, and mechanisms interlinked with the autophagy pathway, which include neuro-inflammation, mTOR signaling, the endocannabinoid system, and UCHL1, UBQLN1, SNCA, PSEN1, MAPT, ITPR1, GFAP, FOXO1, CTSD, CLU, CDK5, BECN1, BCL2, ATG7 signaling pathways (Uddin et al., 2018).

Many autophagy inducers or mTOR inhibitors are used for AD treatment. However, there are several autophagy-inducing agents which require validation. For instance, primary mTORC1 inhibitors termed rapalogs are effective in AD models, while secondary compounds like torins have not been verified. The mTORC1 activity will be blocked by these molecules, like ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors (Zheng and Jiang, 2015). The alteration of cell signaling concerning the mTOR pathway may protect neurons and pose a new approach for neurodegenerative disorders.

Most molecules like calpeptin, minoxidil, and BH3 mimetics, which are autophagy-independent and mTOR-dependent, were not examined in AD models (Sarkar, 2013) (Levine et al., 2015) (Pierzynowska et al., 2018). Henceforward, the studies on the mechanism of autophagy induction by these molecules and the side effects are becoming more relevant for AD treatment (Schmukler and Pinkas-Kramarski, 2020).

AD has become a globally reported disease with 24 million victims, and the cases are expected to quadruple in due course over the years. Despite the worldwide prevalence, only two types of drug molecules, namely N-methyl d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists and cholinesterase enzyme inhibitors, have been approved for AD treatment.

Treatment strategies for AD include the use of symptomatic agents such as cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., donepezil and rivastigmine), disease-modifying therapeutics (e.g., aducanumab and gantenerumab), disease-modifying agents (e.g., lithium and riluzole), chaperone proteins (HSPs), vacuolar sorting protein 35 and several other extracts from natural products (Breijyeh and Karaman, 2020). Many drugs are designed with the function of activating autophagic flux and inhibiting mTOR signaling for AD diagnosis. In recent years, many studies revealed that rapamycin has neuroprotective activity and can act as a pro-autophagy molecule in animal and cell models (Kaeberlein and Galvan, 2019). The toxic nature of various amyloidogenic peptides responds to rapamycin treatment in neuron cell cultures (Boland et al., 2008; Spilman et al., 2010). Similar positive results were observed in other animal models with parameters like aging, protein misfolding, neurotoxicity, and inheritance leading to neurodegeneration (Malagelada et al., 2010).

Several studies on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-affected patients with lithium conveyed positive results in clinical trials (Fornai et al., 2008), and also, recently, the efficiency of rapamycin in AD-affected patients was validated in randomized placebo-controlled Phase-II clinical trials (Mandrioli et al., 2018). Autophagy, i.e., autophagic flux and its modulation, needs 1) complicated and multifaceted signaling, 2) integration coupling of environmental conditions, and 3) functional cell communications that include differentiation, proliferation, and cytoplasmic homeostasis (Thellung et al., 2019).

Rapamycin, a member of the macrolide class, and its analogs, generally known as rapalogs, are meant for the inhibition of mTOR signaling. The said first-generation mTOR inhibitors like everolimus, rapamycin and temsirolimus bind to the 12-kDa FK506 binding protein (FKBP-12) outside the ATP binding pocket and inhibit the mTORC1 kinase activity, keeping mTORC2 unaltered (Ballou and Lin, 2008).

The drugs acting as autophagy activators can be a novel approach for neural protection by reducing the toxicity levels of misfolded proteins (Thellung et al., 2019). In general, all neurodegenerative disorders show similar pathogenic mechanisms like autophagic flux impairment losing the ability to degrade the neurotoxic oligomers of wrongly folded proteins. Nevertheless, the autophagy process can be pharmacologically activated by hindering the enzymatic activity of mTORC1. Consequently, its autophagy suppressing activity, found in the physiological condition, is lost. Similarly, rapamycin is the first drug that acts pharmacologically by enhancing autophagy inducing neuroprotection, and offering the clearance of oligomers. This step necessitates disease-modifying strategies to trigger the development of new compounds and also the modification of existing drug molecules for better pro-autophagic potentiality.

The rapalogs and rapamycin act as autophagy inducers by stabilizing raptor-mTOR connectivity and inhibiting mTOR stimulation (Lamming et al., 2013). Torin1 and dactolisib can also inhibit mTOR signaling. Other compounds that activate AMPK signaling, like trehalose, metformin, and resveratrol, promote mTOR inactivation and are AMPK-dependent (Figure 7). Furthermore, compounds such as Apelins (Jiang et al., 2020), Tramadol (Soltani et al., 2020), Curcumin (Wang et al., 2014b; Zhu and Bu, 2017), Cubebene (Li et al., 2019), Gemfibrozil (Luo et al., 2020), β-asarone (Wang et al., 2020) and Salidroside (Rong et al., 2020) promote inhibition of mTOR via inhibition of phosphoinositide/Akt pathway.

One of the key considerations in assessing the effect of autophagy induction on AD prevention is that the chemical molecules are non-specific and, therefore, may affect other processes in the cell. Henceforth, to verify and understand the effects and treatment modes of the molecules, the autophagy-inducing agent enhancing autophagy in AD must be demonstrated, on which the therapeutic effect of the said molecule relies on.

Table 1 lists several autophagy inducers and their mechanism of autophagy induction, which acts via the direct or indirect inhibition of mTOR (Heras-Sandoval et al., 2020). Few other drugs/molecules were also claimed to induce autophagy, but they may trigger defective autophagy process by modifying the autophagosome formation, autophagosome maturation, and the autophagy-lysosomal pathway via faulty lysosomal acidification (Uddin et al., 2019). Another critical challenge is whether the autophagy inducers virtually influence all AD types and whether it must be applied to populations based on the disease stage and the patient genetic history.

Overall, since the combined hypothesis on molecular mechanisms of neuron destruction in various neurodegenerative disorders includes autophagy pathway malfunction leading to oligomer aggregation, analysis of the utilization of pro-autophagic drugs will validate this role further, even in AD conditions. Specifically, existing and novel compounds are under preclinical and clinical trials for the induction of autophagy through oligomer clearance. Besides, many existing drugs will have off-target effects. Hence, there remains the necessity for developing novel assays for detecting autophagic flux in clinical trials of animal and human models.

Despite the collection of huge data in the current review on the role of autophagy in AD treatment, the proper functioning of autophagy and the mechanical induction of autophagy by drug compounds is decisive for aging and neurons in a natural way. The defect in the autophagic mechanism of neurons is one of the projecting factors that generate neurodegenerative disorders like AD. Although its therapeutic effect requires further validation studies, and since autophagy is mainly affected in AD, autophagy remains a primary innovation as a new therapeutic target in the form of autophagy inducers.

The Aβ and tau protein metabolism pathways, mTOR signaling, and autophagy’s role are significant, including mediating effects in neuro-inflammation and endo-cannabinoid systems, and are tremendously influenced by the autophagy process acting as intermediating agents during AD conditions. Therefore, therapeutic approaches targeting the autophagy mechanism would pave the way for expanding novel strategies for AD management. The new approaches should include therapeutics that inhibit mTOR signaling and induce autophagy without altering the other interconnected mechanisms.

Writing—original draft: AS, TT, GR, LSW, and MS; Conceptualisation: AS, TT, GR, LSW, and MS; Supervision: AS, TT, GR, LSW, and MS; Resources: AS, TT, AA, GR, LSW, MS, SHG, VS, SVC, NNIMR, NS and SW; Data curation: AS, TT, AA, GR, LSW, MS, SHG, VS, SVC, NNIMR, NS and SW; Writing—review and editing: AS, TT, AA, GR, LSW, MS, SHG, VS, SVC, NNIMR, NS and SW. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Groups Project under grant number (RGP.2/58/43). All the authors of this manuscript extend their appreciation to their respective Departments/Universities for successful completion of this study. The figures in this manuscript were created with the support of https://biorender.com under a paid subscription.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aman, Y., Schmauck-Medina, T., Hansen, M., Morimoto, R. I., Simon, A. K., Bjedov, I., et al. (2021). Autophagy in healthy aging and disease. Nat. Aging 1, 634–650. doi:10.1038/s43587-021-00098-4

Ashrafi, G., and Schwarz, T. L. (2015). PINK1- and PARK2-mediated local mitophagy in distal neuronal axons. Autophagy 11, 187–189. doi:10.1080/15548627.2014.996021

Ballou, L. M., and Lin, R. Z. (2008). Rapamycin and mTOR kinase inhibitors. J. Chem. Biol. 1, 27–36. doi:10.1007/s12154-008-0003-5

Boland, B., Kumar, A., Lee, S., Platt, F. M., Wegiel, J., Yu, W. H., et al. (2008). Autophagy induction and autophagosome clearance in neurons: Relationship to autophagic pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 28, 6926–6937. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0800-08.2008

Breijyeh, Z., and Karaman, R. (2020). Comprehensive review on Alzheimer’s disease: Causes and treatment. Molecules 25, 5789. doi:10.3390/molecules25245789

Caccamo, A., Majumder, S., Richardson, A., Strong, R., and Oddo, S. (2010). Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-beta, and tau: Effects on cognitive impairments. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13107–13120. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.100420

Caccamo, A., Maldonado, M. A., Majumder, S., Medina, D. X., Holbein, W., Magrí, A., et al. (2011). Naturally secreted amyloid-β increases mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity via a PRAS40-mediated mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8924–8932. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.180638

Cai, Z., Zhou, Y., Xiao, M., Yan, L.-J., and He, W. (2015). Activation of mTOR: A culprit of alzheimer& rsquo;s disease? Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 1015, 1015–1030. doi:10.2147/NDT.S75717

Chong, Z. Z., Shang, Y. C., and Maiese, K. (2011). Cardiovascular disease and mTOR signaling. Trends cardiovasc. Med. 21, 151–155. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2012.04.005

Chong, Z. Z., Shang, Y. C., Zhang, L., Wang, S., and Maiese, K. (2010). Mammalian target of rapamycin: Hitting the bull’s-eye for neurological disorders. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 3, 374–391. doi:10.4161/oxim.3.6.14787

Coffey, E. E., Beckel, J. M., Laties, A. M., and Mitchell, C. H. (2014). Lysosomal alkalization and dysfunction in human fibroblasts with the Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin 1 A246E mutation can be reversed with cAMP. Neuroscience 263, 111–124. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.01.001

Colacurcio, D. J., and Nixon, R. A. (2016). Disorders of lysosomal acidification—the emerging role of v-ATPase in aging and neurodegenerative disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 32, 75–88. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.004

Cuervo, A. M., and Wong, E. (2014). Chaperone-mediated autophagy: Roles in disease and aging. Cell Res. 24, 92–104. doi:10.1038/cr.2013.153

Dazert, E., and Hall, M. N. (2011). mTOR signaling in disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 744–755. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2011.09.003

De-Paula, V. J., Radanovic, M., Diniz, B. S., and Forlenza, O. V. (2012). Alzheimer’s Dis., 329–352. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5416-4_14

Dikic, I., and Elazar, Z. (2018). Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 349–364. doi:10.1038/s41580-018-0003-4

Ferrer, I., Barrachina, M., and Puig, B. (2002). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is associated with neuronal and glial hyperphosphorylated tau deposits in Alzheimer’s disease, Pick’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 104, 583–591. doi:10.1007/s00401-002-0587-8

Fornai, F., Longone, P., Cafaro, L., Kastsiuchenka, O., Ferrucci, M., Manca, M. L., et al. (2008). Lithium delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 2052–2057. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708022105

Fornai, F., and Puglisi-Allegra, S. (2021). Autophagy status as a gateway for stress-induced catecholamine interplay in neurodegeneration. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 123, 238–256. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.015

Galvan, V., and Hart, M. J. (2016). Vascular mTOR-dependent mechanisms linking the control of aging to Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis. 1862, 992–1007. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.11.010

Gharibi, B., Farzadi, S., Ghuman, M., and Hughes, F. J. (2014). Inhibition of akt/mTOR attenuates age-related changes in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 32, 2256–2266. doi:10.1002/stem.1709

Glick, D., Barth, S., and Macleod, K. F. (2010). Autophagy: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Pathol. 221, 3–12. doi:10.1002/path.2697

Gouras, G. K. (2013). mTOR: at the crossroads of aging, chaperones, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 124, 747–748. doi:10.1111/jnc.12098

Griffin, R. J., Moloney, A., Kelliher, M., Johnston, J. A., Ravid, R., Dockery, P., et al. (2005). Activation of Akt/PKB, increased phosphorylation of Akt substrates and loss and altered distribution of Akt and PTEN are features of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J. Neurochem. 93, 105–117. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02949.x

Habib, S. L., and Liang, S. (2014). Hyperactivation of Akt/mTOR and deficiency in tuberin increased the oxidative DNA damage in kidney cancer patients with diabetes. Oncotarget 5, 2542–2550. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.1833

Heras-Sandoval, D., Pérez-Rojas, J. M., and Pedraza-Chaverri, J. (2020). Novel compounds for the modulation of mTOR and autophagy to treat neurodegenerative diseases. Cell. Signal. 65, 109442. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109442

Höhn, A., Tramutola, A., and Cascella, R. (2020). Proteostasis failure in neurodegenerative diseases: Focus on oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 5497046. doi:10.1155/2020/5497046

Hsieh, A., and Edlind, M. (2014). PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling in prostate cancer progression and androgen deprivation therapy resistance. Asian J. Androl. 16, 378–386. doi:10.4103/1008-682X.122876

Inoue, K., Rispoli, J., Kaphzan, H., Klann, E., Chen, E. I., Kim, J., et al. (2012). Macroautophagy deficiency mediates age-dependent neurodegeneration through a phospho-tau pathway. Mol. Neurodegener. 7, 48. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-7-48

Ji, Z.-S., Müllendorff, K., Cheng, I. H., Miranda, R. D., Huang, Y., and Mahley, R. W. (2006). Reactivity of apolipoprotein E4 and amyloid beta peptide: Lysosomal stability and neurodegeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2683–2692. doi:10.1074/jbc.M506646200

Jiang, T.-F., Zhang, Y.-J., Zhou, H.-Y., Wang, H.-M., Tian, L.-P., Liu, J., et al. (2013). Curcumin ameliorates the neurodegenerative pathology in A53T α-synuclein cell model of Parkinson’s disease through the downregulation of mTOR/p70S6K signaling and the recovery of macroautophagy. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 8, 356–369. doi:10.1007/s11481-012-9431-7

Jiang, W., Zhao, P., and Zhang, X. (2020). Apelin promotes ECM synthesis by enhancing autophagy flux via TFEB in human degenerative NP cells under oxidative stress. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 4897170–4897178. doi:10.1155/2020/4897170

Kaeberlein, M., and Galvan, V. (2019). Rapamycin and Alzheimer’s disease: Time for a clinical trial? Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaar4289. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aar4289

Kanehisa, M., and Goto, S. (2000). Kegg: Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.27

Kaper, F., Dornhoefer, N., and Giaccia, A. J. (2006). Mutations in the PI3K/PTEN/TSC2 pathway contribute to mammalian target of rapamycin activity and increased translation under hypoxic conditions. Cancer Res. 66, 1561–1569. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3375

Kerr, J. S., Adriaanse, B. A., Greig, N. H., Mattson, M. P., Cader, M. Z., Bohr, V. A., et al. (2017). Mitophagy and Alzheimer’s disease: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 40, 151–166. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2017.01.002

Klionsky, D. J. (2008). Autophagy revisited: A conversation with christian de Duve. Autophagy 4, 740–743. doi:10.4161/auto.6398

Lamming, D. W., Ye, L., Sabatini, D. M., and Baur, J. A. (2013). Rapalogs and mTOR inhibitors as anti-aging therapeutics. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 980–989. doi:10.1172/JCI64099

Lee, J.-H., Yang, D.-S., Goulbourne, C. N., Im, E., Stavrides, P., Pensalfini, A., et al. (2022). Faulty autolysosome acidification in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models induces autophagic build-up of Aβ in neurons, yielding senile plaques. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 688–701. doi:10.1038/s41593-022-01084-8

Leidal, A. M., Levine, B., and Debnath, J. (2018). Autophagy and the cell biology of age-related disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 1338–1348. doi:10.1038/s41556-018-0235-8

Levine, B., Packer, M., and Codogno, P. (2015). Development of autophagy inducers in clinical medicine. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 14–24. doi:10.1172/JCI73938

Li, X., Alafuzoff, I., Soininen, H., Winblad, B., and Pei, J.-J. (2005). Levels of mTOR and its downstream targets 4E-BP1, eEF2, and eEF2 kinase in relationships with tau in Alzheimer’s disease brain. FEBS J. 272, 4211–4220. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04833.x

Li, X., Song, J., and Dong, R. (2019). Cubeben induces autophagy via PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway to protect primary neurons against amyloid beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Cytotechnology 71, 679–686. doi:10.1007/s10616-019-00313-6

Loera-Valencia, R., Cedazo-Minguez, A., Kenigsberg, P. A., Page, G., Duarte, A. I., Giusti, P., et al. (2019). Current and emerging avenues for Alzheimer’s disease drug targets. J. Intern. Med. 286, 398–437. doi:10.1111/joim.12959

Lovell, M. A., and Markesbery, W. R. (2007). Oxidative DNA damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 7497–7504. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm821

Luo, R., Su, L.-Y., Li, G., Yang, J., Liu, Q., Yang, L.-X., et al. (2020). Activation of PPARA-mediated autophagy reduces Alzheimer disease-like pathology and cognitive decline in a murine model. Autophagy 16, 52–69. doi:10.1080/15548627.2019.1596488

Ma, T., Hoeffer, C. A., Capetillo-Zarate, E., Yu, F., Wong, H., Lin, M. T., et al. (2010). Dysregulation of the mTOR pathway mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 5, e12845. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012845

Malagelada, C., Jin, Z. H., Jackson-Lewis, V., Przedborski, S., and Greene, L. A. (2010). Rapamycin protects against neuron death in in vitro andin vivo models of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 30, 1166–1175. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3944-09.2010

Mandrioli, J., D’Amico, R., Zucchi, E., Gessani, A., Fini, N., Fasano, A., et al. (2018). Rapamycin treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Protocol for a phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, clinical trial (RAP-ALS trial). Med. Baltim. 97, e11119. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011119

Mariño, G., Madeo, F., and Kroemer, G. (2011). Autophagy for tissue homeostasis and neuroprotection. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 198–206. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.001

Martínez-Martínez, E., Jurado-López, R., Valero-Muñoz, M., Bartolomé, M. V., Ballesteros, S., Luaces, M., et al. (2014). Leptin induces cardiac fibrosis through galectin-3, mTOR and oxidative stress: Potential role in obesity. J. Hypertens. 32, 1104–1114. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000149

Medina, D. L., Di Paola, S., Peluso, I., Armani, A., De Stefani, D., Venditti, R., et al. (2015). Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 288–299. doi:10.1038/ncb3114

Meng, X.-F., Yu, J.-T., Song, J.-H., Chi, S., and Tan, L. (2013). Role of the mTOR signaling pathway in epilepsy. J. Neurol. Sci. 332, 4–15. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2013.05.029

Metcalf, D. J., García-Arencibia, M., Hochfeld, W. E., and Rubinsztein, D. C. (2012). Autophagy and misfolded proteins in neurodegeneration. Exp. Neurol. 238, 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.11.003

Morales-Corraliza, J., Wong, H., Mazzella, M. J., Che, S., Lee, S. H., Petkova, E., et al. (2016). Brain-wide insulin resistance, tau phosphorylation changes, and hippocampal neprilysin and amyloid-β alterations in a monkey model of type 1 diabetes. J. Neurosci. 36, 4248–4258. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4640-14.2016

Mueed, Z., Tandon, P., Maurya, S. K., Deval, R., Kamal, M. A., and Poddar, N. K. (2019). Tau and mTOR: The hotspots for multifarious diseases in Alzheimer’s development. Front. Neurosci. 12, 1017. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.01017

Muñoz, F. J., and Inestrosa, N. C. (1999). Neurotoxicity of acetylcholinesterase amyloid beta-peptide aggregates is dependent on the type of Abeta peptide and the AChE concentration present in the complexes. FEBS Lett. 450, 205–209. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00468-8

Nixon, R. A. (2013). The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 19, 983–997. doi:10.1038/nm.3232

Nixon, R. A., Yang, D.-S., and Lee, J.-H. (2008). Neurodegenerative lysosomal disorders: A continuum from development to late age. Autophagy 4, 590–599. doi:10.4161/auto.6259

Oddo, S., Caccamo, A., Smith, I. F., Green, K. N., and LaFerla, F. M. (2006). A dynamic relationship between intracellular and extracellular pools of Abeta. Am. J. Pathol. 168, 184–194. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2006.050593

Paccalin, M., Pain-Barc, S., Pluchon, C., Paul, C., Besson, M.-N., Carret-Rebillat, A.-S., et al. (2006). Activated mTOR and PKR kinases in lymphocytes correlate with memory and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 22, 320–326. doi:10.1159/000095562

Pang, Y., Lin, W., Zhan, L., Zhang, J., Zhang, S., Jin, H., et al. (2022). Inhibiting autophagy pathway of PI3K/AKT/mTOR promotes apoptosis in SK-N-sh cell model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 6069682. doi:10.1155/2022/6069682

Perluigi, M., Di Domenico, F., Barone, E., and Butterfield, D. A. (2021). mTOR in Alzheimer disease and its earlier stages: Links to oxidative damage in the progression of this dementing disorder. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 169, 382–396. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.04.025

Pierzynowska, K., Gaffke, L., Cyske, Z., Puchalski, M., Rintz, E., Bartkowski, M., et al. (2018). Autophagy stimulation as a promising approach in treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Metab. Brain Dis. 33, 989–1008. doi:10.1007/s11011-018-0214-6

Rong, L., Li, Z., Leng, X., Li, H., Ma, Y., Chen, Y., et al. (2020). Salidroside induces apoptosis and protective autophagy in human gastric cancer AGS cells through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 122, 109726. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109726

Santos, R. X., Correia, S. C., Zhu, X., Lee, H.-G., Petersen, R. B., Nunomura, A., et al. (2012). Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA oxidation in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic. Res. 46, 565–576. doi:10.3109/10715762.2011.648188

Sarkar, S. (2013). Regulation of autophagy by mTOR-dependent and mTOR-independent pathways: Autophagy dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases and therapeutic application of autophagy enhancers. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41, 1103–1130. doi:10.1042/BST20130134

Scheltens, P., Blennow, K., Breteler, M. M. B., de Strooper, B., Frisoni, G. B., Salloway, S., et al. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 388, 505–517. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1

Schmukler, E., and Pinkas-Kramarski, R. (2020). Autophagy induction in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Dev. Res. 81, 184–193. doi:10.1002/ddr.21605

Selkoe, D. J., and Hardy, J. (2016). The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 595–608. doi:10.15252/emmm.201606210

Shafei, M. A., Harris, M., and Conway, M. E. (2017). Divergent metabolic regulation of autophagy and mTORC1—early events in Alzheimer’s disease? Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 173. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2017.00173

Siman, R., Cocca, R., and Dong, Y. (2015). The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin mitigates perforant pathway neurodegeneration and synapse loss in a mouse model of early-stage alzheimer-type tauopathy. PLoS One 10, e0142340. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142340

Soltani, R., Boroujeni, M. E., Aghajanpour, F., Khatmi, A., Ezi, S., Mirbehbahani, S. H., et al. (2020). Tramadol exposure upregulated apoptosis, inflammation and autophagy in PC12 cells and rat’s striatum: An in vitro- in vivo approach. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 109, 101820. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2020.101820

Spilman, P., Podlutskaya, N., Hart, M. J., Debnath, J., Gorostiza, O., Bredesen, D., et al. (2010). Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin abolishes cognitive deficits and reduces amyloid-β levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 5, e9979. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009979

Sun, Y.-X., Ji, X., Mao, X., Xie, L., Jia, J., Galvan, V., et al. (2013). Differential activation of mTOR complex 1 signaling in human brain with mild to severe Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 38, 437–444. doi:10.3233/JAD-131124

Thellung, S., Corsaro, A., Nizzari, M., Barbieri, F., and Florio, T. (2019). Autophagy activator drugs: A new opportunity in neuroprotection from misfolded protein toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 901. doi:10.3390/ijms20040901

Tomiyama, T., Shoji, A., Kataoka, K., Suwa, Y., Asano, S., Kaneko, H., et al. (1996). Inhibition of amyloid beta protein aggregation and neurotoxicity by rifampicin. Its possible function as a hydroxyl radical scavenger. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6839–6844. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.12.6839

Torres, M., Jimenez, S., Sanchez-Varo, R., Navarro, V., Trujillo-Estrada, L., Sanchez-Mejias, E., et al. (2012). Defective lysosomal proteolysis and axonal transport are early pathogenic events that worsen with age leading to increased APP metabolism and synaptic Abeta in transgenic APP/PS1 hippocampus. Mol. Neurodegener. 7, 59. doi:10.1186/1750-1326-7-59

Tramutola, A., Triplett, J. C., Di Domenico, F., Niedowicz, D. M., Murphy, M. P., Coccia, R., et al. (2015). Alteration of mTOR signaling occurs early in the progression of alzheimer disease (AD): Analysis of brain from subjects with pre-clinical AD, amnestic mild cognitive impairment and late-stage AD. J. Neurochem. 133, 739–749. doi:10.1111/jnc.13037

Uddin, M. S., Mamun, A. Al, Labu, Z. K., Hidalgo-Lanussa, O., Barreto, G. E., and Ashraf, G. M. (2019). Autophagic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Cellular and molecular mechanistic approaches to halt Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 8094–8112. doi:10.1002/jcp.27588

Uddin, M. S., Stachowiak, A., Mamun, A. Al, Tzvetkov, N. T., Takeda, S., Atanasov, A. G., et al. (2018). Autophagy and Alzheimer’s disease: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10, 04. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2018.00004

Wang, C., Yu, J.-T., Miao, D., Wu, Z.-C., Tan, M.-S., and Tan, L. (2014a). Targeting the mTOR signaling network for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Mol. Neurobiol. 49, 120–135. doi:10.1007/s12035-013-8505-8

Wang, C., Zhang, X., Teng, Z., Zhang, T., and Li, Y. (2014b). Downregulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in curcumin-induced autophagy in APP/PS1 double transgenic mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 740, 312–320. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.06.051

Wang, N., Wang, H., Li, L., Li, Y., and Zhang, R. (2020). β-Asarone inhibits amyloid-β by promoting autophagy in a cell model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1529. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01529

Ward, C., Martinez-Lopez, N., Otten, E. G., Carroll, B., Maetzel, D., Singh, R., et al. (2016). Autophagy, lipophagy and lysosomal lipid storage disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1861, 269–284. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.01.006

Yang, F., Chu, X., Yin, M., Liu, X., Yuan, H., Niu, Y., et al. (2014). mTOR and autophagy in normal brain aging and caloric restriction ameliorating age-related cognition deficits. Behav. Brain Res. 264, 82–90. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2014.02.005

Yang, Z., and Ming, X.-F. (2012). mTOR signalling: the molecular interface connecting metabolic stress, aging and cardiovascular diseases. Obes. Rev. 13, 58–68. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01038.x

Yoon, M.-S. (2017). The role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in insulin signaling. Nutrients 9, 1176. doi:10.3390/nu9111176

Zhang, W., Xu, C., Sun, J., Shen, H.-M., Wang, J., and Yang, C. (2022). Impairment of the autophagy–lysosomal pathway in Alzheimer’s diseases: Pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 12, 1019–1040. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2022.01.008

Zhang, X., Chen, S., Huang, K., and Le, W. (2013). Why should autophagic flux be assessed? Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 34, 595–599. doi:10.1038/aps.2012.184

Zheng, Y., and Jiang, Y. (2015). mTOR inhibitors at a glance. Mol. Cell. Pharmacol. 7, 15–20. doi:10.4255/mcpharmacol.15.02

Zhu, Y., and Bu, S. (2017). Curcumin induces autophagy, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest in human pancreatic cancer cells. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 5787218. doi:10.1155/2017/5787218

AD Alzheimer’s Disease

APP Amyloid Precursor Protein

NFTs Neurofibrillary Tangles

mTOR Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin

mTORC1 Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex

UCHL-1 Ubiquitin C-Terminal hydrolase L1

UBQLN1 Ubiquitin-1

SNCA Alpha Synuclein gene

PSEN1 Presenilin-1

MAPT Microtubule Associated Protein tau

ITPR1 Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor type-I

GFAP Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

FOXO1 Forkhead Box Protein O1

CTSD Cathepsin D

CLU Clusterin

CDK5 Cyclin dependent kinase 5

BECN1 Beclin-1

BCL 2 B-Cell lymphoma 2

ATGs Autophagy-related genes

AMPK AMP-activated Protein Kinase

APPCTF C-terminal Fragments of Amyloid Precursor Protein

PI3K Phosphatidyl Inositol 3 Kinase

AKT Serine/Threonine kinase

PHFs Paired Helical Filament

ROS Reactive Oxygen Species

UPS Ubiquitin Protease System

UPR Unfolded Protein Response

EIF4E Eukaryotic Initiative Factor 4E

Ebp1 ErbB3-Binding Protein

P70s6k Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase beta-1

PTEN Phosphate and Tensin Homologue

FKBP FK506 Binding Protein

ATP Adenosine Triphosphate

GSK3β Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta

PARK2 Parkin 2

PINK1 PTEN induced putative kinase 1

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, mTOR pathway, dementia, autophagy, tau protein

Citation: Subramanian A, Tamilanban T, Alsayari A, Ramachawolran G, Wong LS, Sekar M, Gan SH, Subramaniyan V, Chinni SV, Izzati Mat Rani NN, Suryadevara N and Wahab S (2022) Trilateral association of autophagy, mTOR and Alzheimer’s disease: Potential pathway in the development for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1094351. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1094351

Received: 10 November 2022; Accepted: 12 December 2022;

Published: 22 December 2022.

Edited by:

Woon-Man Kung, Chinese Culture University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Yoana Rabanal, University of Castilla-La Mancha, SpainCopyright © 2022 Subramanian, Tamilanban, Alsayari, Ramachawolran, Wong, Sekar, Gan, Subramaniyan, Chinni, Izzati Mat Rani, Suryadevara and Wahab. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: T. Tamilanban, tamilant@srmist.edu.in; Gobinath Ramachawolran, r.gobinath@rcsiucd.edu.my; Ling Shing Wong, lingshing.wong@newinti.edu.my; Mahendran Sekar, mahendransekar@unikl.edu.my

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.