- 1Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Aalto University School of Science, AALTO, Espoo, Finland

- 2The Finnish Research Impact Foundation, Helsinki, Finland

Introduction: This article reviews the discussion concerning hybrid work (HW) during and after the pandemic. We argue that understanding hybrid work as simply dividing working time between an office and another location limits the potential of organizing work sustainably based on organizations' goals and employee needs. Understanding the core nature of hybridity as a flexible and systemic entity and a “combination of two or more things” impacting work outcomes such as wellbeing and performance opens a much richer view of organizing work now and in the future. The critical questions are: What is the core nature of hybridity when two or more things are combined in work, and what factors influence configuring them? Moreover, what are their potential wellbeing and performance outcomes?

Methods: To discover core elements, we reviewed how the HW concept was defined in consulting companies' publications, business journals, and international organizations' publications, mainly focusing on challenges and opportunities for hybrid work during COVID-19. We also analyzed how the concept was used in European questionnaire findings from 27 EU countries during the pandemic. The potential wellbeing and performance outcomes were studied using a sample of prior literature reviews on remote and telework. To identify “Two or more things” in the discussions, we broke down the HW concepts into the physical, virtual, social, and temporal work elements and their sub-elements and designable features.

Results: We found that the concepts used in the discussions on hybrid work reflect traditional views of remote and telework as a combination of working at home and in the office.

Discussion: We suggest configuring hybrid work as a flexible entity, which opens a perspective to design and implement diverse types of hybrid work that are much more prosperous and sustainable than just combining onsite and offsite work. The expected wellbeing and performance outcomes can be controversial due to the misfit of the hybrid work elements with the organizational purpose, employee needs and expectations, and non-observed contextual factors in implementations.

1 Introduction

Hybrid refers to the “combination of two or more things.” Illustrative examples of the use of two elements are: “a hybrid of two roses,” “a hybrid car,” and “a Finnish-Congolese background.” However, potentially, more elements could be used. We aim to show examples of more elements and how they can be combined.

The use of the term in the context of work started soon after the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the autumn of 2020, and the discussion, definition, and development of the concept of “hybrid work” (HW) has continued since. The discussion concerned the time after the pandemic and what working life and workplaces would be like. However, the discussion quickly turned to examining hybridity from a relatively narrow perspective, which defines hybrid work as flexibility in place and time. In this concept, work is done partly from the employer's premises and partly from home or elsewhere, using digital tools to communicate and collaborate. This formulation resembles the traditional notion of telework (Nilles, 2000).

After 3 years, however, there are still open questions: What are the elements, content, and effects of hybrid work in practice at the level of the individual, organization, and society? Or does this form of work only reflect the development of previous remote work, or is it a qualitatively new form of work? And what factors influence the configuration of the elements and impact the wellbeing and performance outcomes of employees and organizations. The issue is very much “under construction.” Clarifying the concept and its operationalizations would enable us to see emerging new ways of working more richly than just combining place and time. A more versatile view would also open more opportunities to design, implement, and sustainably develop work according to organizations' goals and employees' needs.

Thus, we seek to contribute to this discussion by reviewing the existing definitions of hybrid work in the literature, analyzing hybrid work definitions emerging in our questionnaire data, reflecting them to the traditional concepts of telework, and proposing a conceptual model of hybrid work that addresses its true nature and contextual and temporal dependency. Our research questions are: What is the core nature of hybridity when two or more things are combined in work, and what factors influence configuring them? Moreover, what are their potential wellbeing and performance outcomes?

For the analysis, we first constructed a preliminary hybrid work model using the workspace concept based on the field theory of Lewin (1972) and the “Ba” concept of Nonaka et al. (2000). We then used this model to classify, map, and critically assess the ongoing discussions during the pandemic in publications on hybrid work and made our conclusions concerning its core contents. This content analysis was complemented by an analysis of empirical data collected through a survey in Europe. In addition, we sought potential additional elements and features related to hybrid work from our material. Finally, we compared our findings with the traditional definitions and operationalizations of remote work and telework and reviewed findings of their wellbeing and performance outcomes. Based on the above, we also suggest some practical implications for the future.

2 The changing context of work

2.1 Remote work is here to stay

Before the outbreak of the pandemic, differences in the levels of remote work, i.e., working anywhere, and telework, i.e., working anywhere using personal electronic devices, among countries were driven by factors such as the type of profession, gender, organization of work, and deep-rooted practices and regulations in common use, as well as management culture in organizations and countries themselves. As far as working from home permanently, ILO data (ILO, 2021a) indicate that 7.9% of the global workforce—~260 million workers, including artisans and self-employed business owners—worked from home permanently before the pandemic. Company employees accounted for 18.8% of the total number of fully home-based workers worldwide. However, in high-income countries, this number was as high as 55.1% (ILO, 2020a), mostly comprising teleworking employees.

The pandemic brought a well-known change to remote working from home (WFH). A global survey (N = 208,807, from 190 countries) by the Boston Consulting Group and The Network between October and early December 2020 showed a global shift to full or part-time work-from-home models from an average of 31% before the COVID-19 pandemic to 51% during the pandemic, especially among digital and knowledge-based workers (Strack et al., 2021). There was a large variation among countries (e.g., 90% in the Netherlands; 37% in China) and job types (e.g., IT and technology, 77%; manual work and manufacturing, 19%) worldwide. According to Hatayama et al. (2020), the amenability of employers to allow employees to have internet access at home was an important determinant of working from home.

Today, surveys worldwide show that the trend of flexible hybrid work arrangements continued after the pandemic. A global survey (Aksoy et al., 2023) shows that full-time employees worked from home 0.9 days per week, on average, looking across 34 countries in April–May 2023. Work from home (WFH) levels were higher in English-speaking countries. Full-time employees worked an average of 1.4 full-paid days per week from home across Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States (US). By comparison, WFH levels average only 0.7 days per week in the seven Asian countries, 0.8 in the European countries, and 0.9 for four Latin American countries and South Africa. In a study1 (WORK 3.0, 2022), 42% of leaders across the Asia Pacific expected that their company's employees post-COVID-19 would spend < 50% of their time on site at the company office. In the US, in June 2024: 61% of employees worked full-time on-site in their main workplace, 12% were fully remote, and 27% in a hybrid arrangement (Barrero et al., 2021).

Similar findings are available from other continents. For example, a recent European study (Sostero et al., 2024) reveals a widespread increase in the prevalence of work from home across EU countries. The telework rates have slightly receded from their peak during the pandemic. However, they remain markedly higher than before the pandemic nearly everywhere in the EU, reflecting a lasting shift in work practices. Sostero et al. underline that despite this common trend, stark disparities persist, especially between urban and rural areas, capital regions, and the rest, and across countries. The regression analysis of the study shows that differences in occupational structures account for the largest share of this variation.

Overall, flexible work arrangements prevail and can be expected to increase. It is worth noting that the studies during and after the pandemic have concentrated on home-based remote and telework and how they can be combined with onsite work. In hybrid work, home and office are only specific options for future locations where you can work. Teleworkability—or better “hybridizability”—concerns potentially a larger group of jobs.

2.2 Teleworkability

Sostero with his colleagues (2020) estimated already before the pandemic that 37% of employees having contractual arrangements in the European Union (EU) are teleworkable, which is very close to the number of teleworkers indicated in real-time surveys at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. However, the figures fluctuate (the number of workers returning to the office increased after the pandemic). One-fifth of employees (22%) were working from home at least some of the time in 2021, doubling the rate since before the pandemic, with 12% sometimes working from home (Eurofound, 2023b). Because of differences in employment structures, the portion of teleworkable employment ranges between 33 and 44% across the EU. According to Sostero et al. (2020), even starker differences in teleworkability emerge between high-income and low-income workers, between white- and blue-collar workers, and among genders. However, the enforced closure of workplaces during the pandemic also resulted in many new teleworkers among low- and mid-level clerical and administrative workers with limited access to such working arrangements.

Like in Europe, Dingel and Neiman (2020) found that 37% of jobs in the United States can be performed at home, with significant variation across occupations. Managers and those working with computers, finance, and professional and business services can largely work from home. In contrast, frontline employees such as health care practitioners and cleaning, construction, and production workers cannot. Those who can work from home usually earn more. This divide is not new, as the 2002 review by Bailey and Kurland already acknowledged it.

Overall, the increased number of remote workers, mainly from home, and the increased autonomy to choose the location of work, i.e., working from anywhere, gave rise to the concept of hybrid work and the motif to analyze the concept of “Hybrid Work” in more detail.

3 Framework of hybrid work

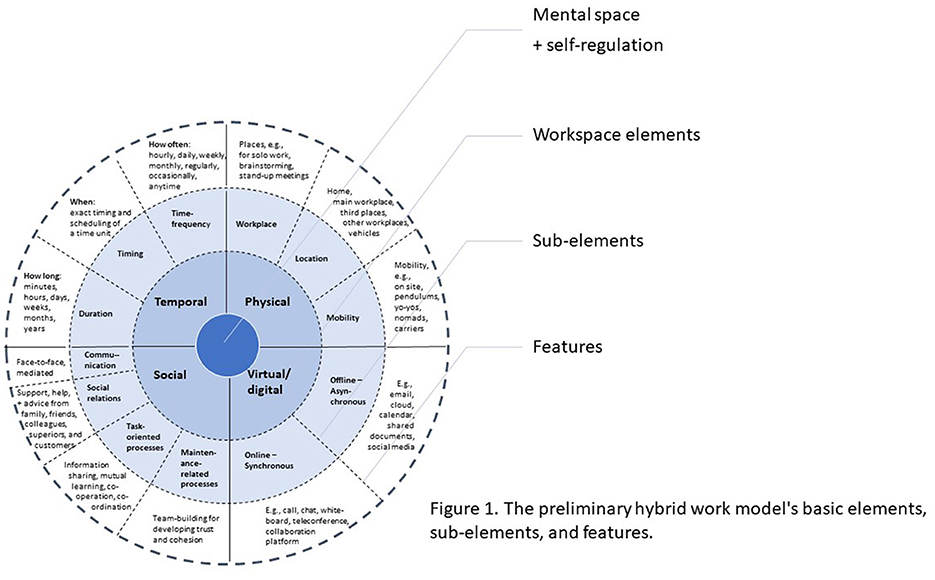

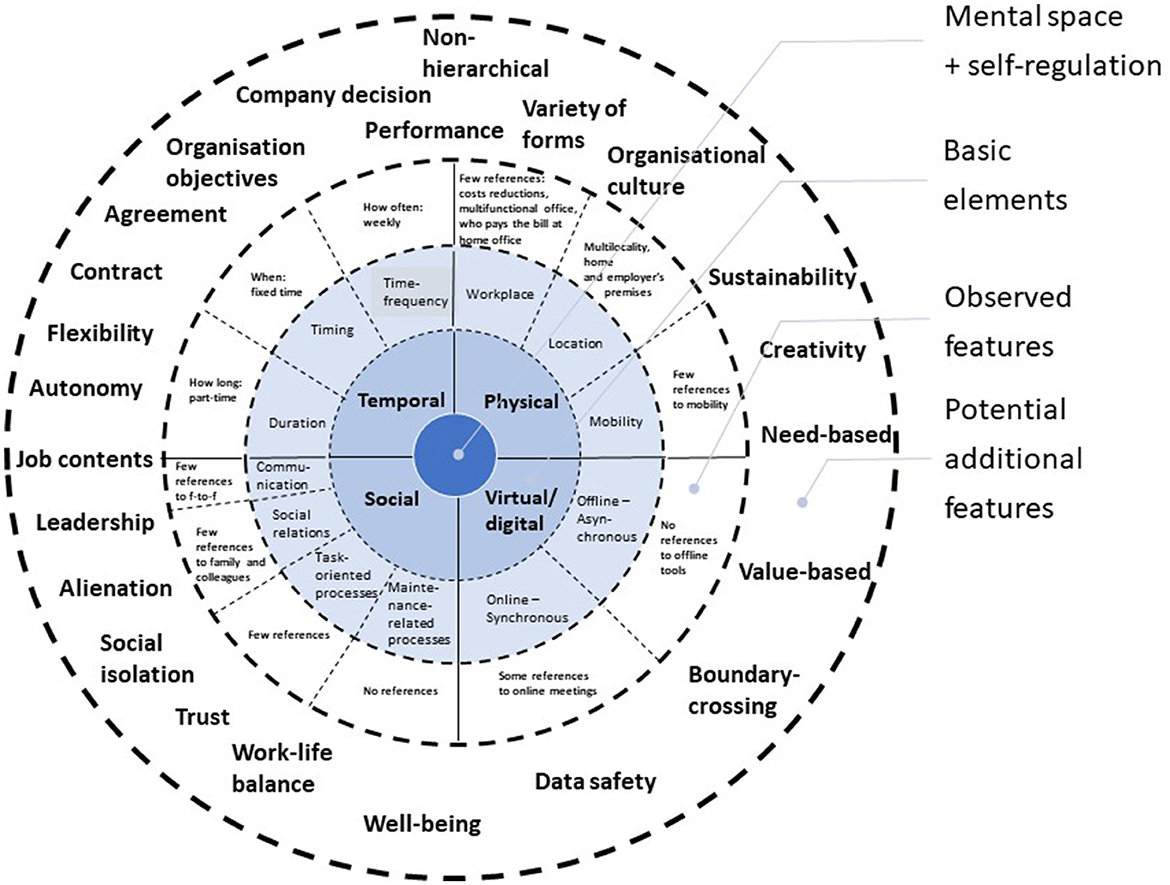

The first step in analyzing the concepts of “hybrid work” as a more complex entity than simply working at home and on-site was to build a framework for mapping the concepts used in the discussions during the pandemic and its aftermath. The framework was constructed based on the field theory and workspace concepts and their operationalizations. The basic although preliminary model with its elements, sub-elements, and features is shown in Figure 1. They were used in the analysis of literature and discourse documents during the pandemic. Figure 3 shows the findings of the discussions in literature and country reports. In addition, the analyses produced some additional features to be used in building future hybrid work practices.

3.1 Framework elements

The preliminary framework is grounded on the workspace concept that returns to the field theory of Lewin (1972) and the “Ba” concept of Nonaka et al. (2000). Lewin introduced the idea that everyone exists in a psychological force field called the “life space” determining and limiting his or her behavior. “Life space” is a highly subjective environment that characterizes the world as the individual sees it while remaining embedded in the objective elements of physical and social fields. “Mental space,” one of the concepts we use in this article, is equivalent to the “Life space” as the experienced state and mood of an individual. In the mental space, an individual regulates his or her living and working activities with his or her mind. According to Lewin (1951), behavior (B) is the function (f) of a person (P) and his/her environment (E), B = f (P, E). Similarly, individuals, teams, and organizations are actors in active, goal-directed interaction with their environments, as the action regulation theory argues (Hacker, 2021). Nonaka et al. (2000) further enlarged the concept of life space with their concept of “Ba.” It refers to a shared context where those who interact and communicate share, create, and utilize knowledge. Ba does not just refer to a physical space but a specific time and space that integrates spaces as layers starting from the physical space. Ba unifies the physical space (such as an open office), the virtual space (such as chatting using digital collaboration platforms), the social space (such as onsite interaction with colleagues), and the mental space (such as individual everyday perceptions, experiences, moods, ideas, values, and ideals) shared by people with common goals in a working context. Based on the above theorizing, the basic elements of the hybrid work model were constructed. For individuals or groups, current work contexts are combinations of physical, virtual, and social elements that can broadly and flexibly change over time, driven by changing goals and job demands (Bakker and Demerouti, 2017). Because of the strong influence of time on the experienced mental state, we use “Temporal space” as the fourth contextual element to describe how other spaces change in time (Figure 1).

In this preliminary hybrid work model, each basic element has its sub-elements, and each sub-element has designable, adjustable, and specific features or characteristics such as working at home, using online technologies, communicating face-to-face, and working fixed days at the office each week. Some hybrid work definitions we analyzed used locations, workplaces, and time as the defining sub-elements of a hybrid workspace. For example, the following expressions were used: “working in [the] office and [at] home,” “not [a] dedicated workplace in [the] office,” and “working elsewhere”; others referred to the sub-elements of temporal space: “two home days” and “three office days” referring to duration, and “occasional telework” referring to time-frequency. Next, the four basic contextual elements and their sub-elements with some features are described in more detail.

3.2 Elements and sub-elements of workspaces

Building on the idea that “hybrid” refers to the combination of two or more things, we propose that the basic contextual elements of hybrid work are physical space, virtual or digital space, social space, and temporal space, i.e., time; they make up the combinable “things” with their sub-elements and features. They all influence mental space, i.e., how an individual perceives and experiences his or her “life space” as a behavioral opportunity and acts on it. They not only offer benefits and opportunities for fluent performance but also create challenges and hindrances, putting pressure on individuals to maintain their wellbeing. Affordances, i.e., the action potentials of the basic contextual elements, are evident in the features of their sub-elements. The basic elements and sub-elements often cross their boundaries. For example, virtual and social spaces partially overlap regarding communication-related collaboration. Social interaction takes place both technology-mediated and face-to-face. How these elements interplay and intersect depends on the concrete needs of work arrangements, i.e., hybridizing mechanisms (see below). The workspace concept requires some more explanations. Therefore, the basic contextual elements and sub-elements are described in more detail below.

3.2.1 Physical space

Location, workplace, and mobility are the sub-elements of physical space, each having specific features. Location refers to the geographical nature of the workplace, for example, in the office and at home, in neighborhoods, urban and rural areas, different parts of the country, other countries, and across the globe. The physical space enables working in each location and becomes a workplace by providing a practical physical context and tools for work. Examples of workplaces are (Vartiainen, 2007, p. 29): (1) the employee's home, (2) the main workplace (the employer's premises), (3) vehicles, such as cars, busses, trams, trains, planes, and ships, (4) a customer's or partner's premises or alternative premises of the company (“other workplaces”), and (5) hotels, cafés, parks, etc. (“third workplaces”). Oldenburg (1989), for example, lists cafés, coffee shops, community centers, general stores, bars, and other places to meet people occasionally as “third workplaces.”

A critical question regarding the functionality of each workplace is what it affords as working environment, i.e., how usable and ergonomic it is in practice, how such a place should be furnished, and what kind of tools are needed and available for work. In practice, the quality of a workplace as a physical premise and a working context varies according to an organization's and its employees' resources.

Mobility is a sub-element of physical space because it allows opportunities to use many locations and places daily and weekly as a work environment. Multi-location causes changes not only in workplaces but also in their virtual and social characteristics. For example, the availability of internet connections and social disruptions vary from place to place. The form of mobility is a designable feature as it can be chosen, i.e., whether it is regular mobility between home and office or complete, continuous mobility within and between several places.

A workplace, its location, and the amount of mobility are designable spatial sub-elements; for example, a desk in an open office space and a living room at home can be options as worksites or may involve working mainly in an office or elsewhere. The availability of workplaces in different locations and the opportunity to choose which and when workplaces to use are potent enablers of hybrid work.

3.2.2. Virtual space

A “virtual space” refers to the global Internet, online platforms, and an organization-wide intranet as a workplace for the digital laborer and a collaborative working environment (CWE) for members of dispersed teams. A virtual workplace is such a place in a virtual space that is used for work and collaboration. Complex virtual spaces integrate many communication tools, such as email, audio and videoconferencing, group calendar, chat, document management and presence awareness tools, into a collaborative working environment, such as a three-dimensional (3D) virtual environment, that is, a virtual world.

An important feature of virtual space is that its tools enable organization members to work alone and together offline (asynchronously) and online (synchronously) when employees are physically dispersed across multiple locations. The pandemic forced many to telework from home and learn to use digital technologies for the first time, as communication tools and collaboration platforms became necessary. New tools and applications were used; for example, online meetings became routine, and many restaurants adopted virtual ordering and delivery services.

3.2.3. Social space

A social space is one of the defining elements in hybrid work, as individual solo work is more an exception than a rule. Social space covers communication and social interaction for different purposes in physical and virtual settings. For example, social support, such as advice and help, can come from various sources, including co-workers, supervisors, customers, family, and friends (Taylor, 2011) both face-to-face and online. People may have the option to work in solitude, doing remote work alone or in person with others, online or offline, asynchronously or synchronously, and at the main workplace or any other location.

A sub-element of the social space is communication, which is a prerequisite for other sub-elements, which are the maintenance of social relations and the processes related to task and team building. Communication is a critical and necessary enabler of social interaction and collaboration in hybrid work. The basic types of interaction in collaborative efforts—that is, task- and group-oriented processes—are based on communication among individuals (e.g., Andriessen, 2003, p. 144–145) and between human actors and AI tools. Task-oriented processes in interactions include information sharing and mutual learning, cooperation, and coordination processes between interaction participants. Information is shared by providing and developing information and knowledge. Cooperation refers to working together in practice; for example, designing a concept, product, or service together. Coordination is needed to adjust each group member's work to the work of others and the goal of the whole group. For example, simple tasks require less coordination, and their competence requirements are lower than in the case of complex tasks. Group maintenance-oriented processes refer to team building for developing trust and cohesion in collaboration. Factors that enable hybrid work at the team level should support these processes. The main criterion when selecting collaboration technologies is the complexity of communication and collaboration tasks. To navigate such complexity, various available adaptation mechanisms include, for example, providing recruitment or training, or changing the tasks, context or tools used.

3.2.4. Temporal space

In addition to the flexible use of physical, virtual, and social spaces, the determining factor in the hybrid work model is the flexibility of time. The temporal element has three sub-elements: duration, timing, and time-frequency. “Duration” concerns how long something happens in time units, i.e., minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, or years. For example, a hybrid employee may be allowed to work 2 weeks per month remotely or can work 4 weeks abroad. “Timing” refers to when something is done or comes about, whether something happens during certain hours of the day or certain days in a week. For example, a hybrid employee may work at home during the morning and on the employer's premises the whole day on Monday and Friday. “Time-frequency” is how often something happens during a period, whether something happens every hour, daily, weekly, monthly, or constantly, and whether it happens regularly or occasionally. For example, a hybrid employee may occasionally work at home.

The temporal element is closely related to other space elements. Time is critical because contextual demands and available resources in flexible hybrid work constantly change. The work environment changes over time—sometimes slowly, but also unexpectedly—pressing an organization to change. An example of an unexpected external reason experienced across the globe was the pandemic that began in the early 2020s. It forced millions of people to swiftly shift to remote work and telework, transforming a home into a workplace. Other minor reasons, such as service and product demand changes, can also initiate change. There are several reasons for the change; they are often external but can also be internal, such as missing organizational skills.

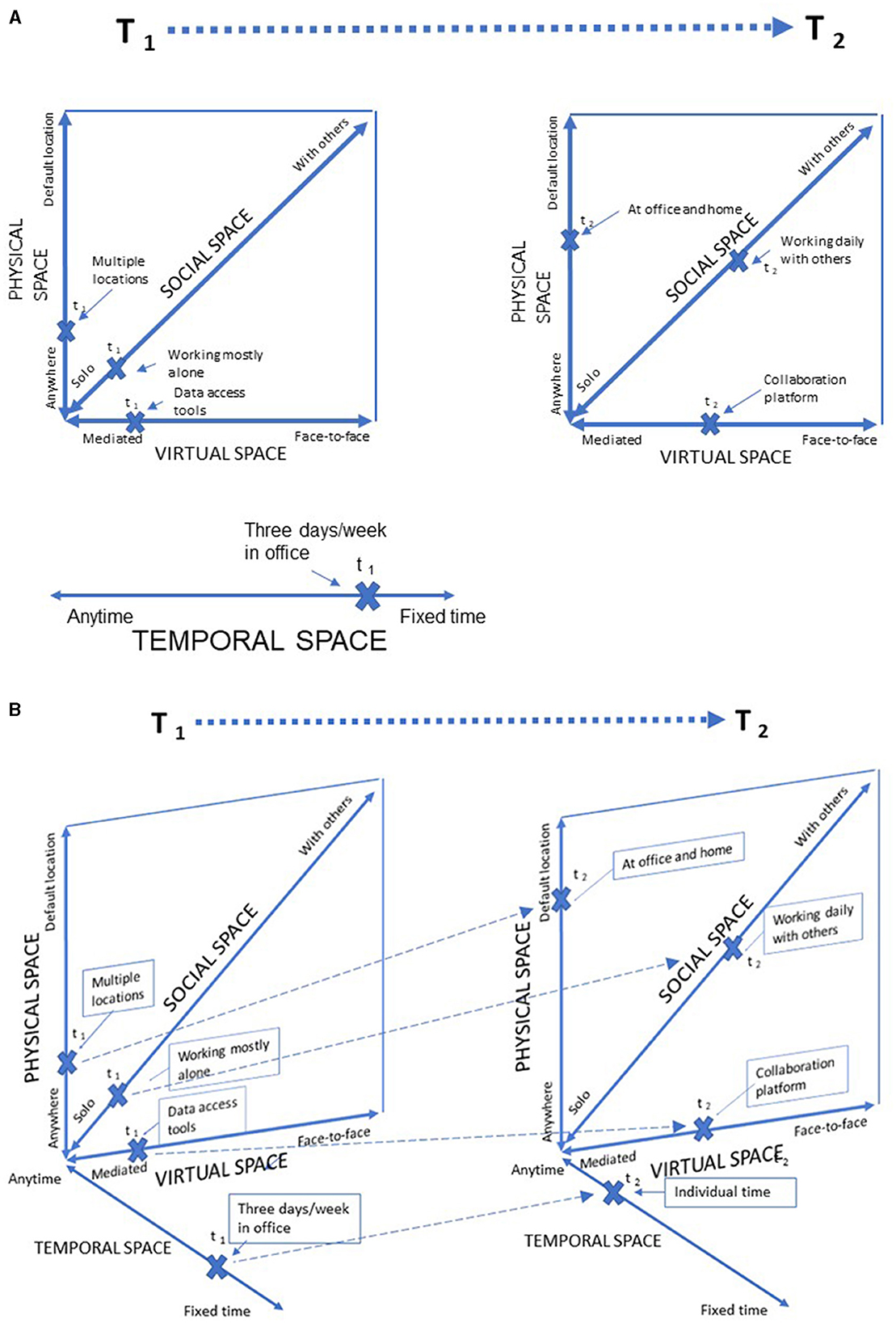

The change reflects the needed configuration of the basic elements, sub-elements, and features. Figures 2A, B illustrate how using multiple locations, working mainly alone, and using digital tools to access data sources change during a given period into working both in the office and at home, daily with others, and through collaboration platforms.

Figure 2. (A) The interdependence of basic elements, sub-elements, and features in T1 and T2 (time) and contextual demands. (B) Changing goals and contexts over time bring dynamism to hybrid work elements.

We used the hybrid work model above with its elements to analyze hybrid work concepts in the professional literature and empirically. Then, we also compared the analysis outcomes to the traditional remote and telework concepts to find their resemblances. We, first, reviewed how the HW concept was defined in consulting companies' publications, business journals, and international organizations' publications, mainly focusing on professional challenges and opportunities for hybrid work during COVID-19. Secondly, we used empirical data collected through a standardized questionnaire circulated in 27 European Union (EU) countries between 15 December 2021 and 7 January 2022 to analyze the evolving hybrid work concept. In addition, we synthesized a sample of empirical reviews on telework's wellbeing and performance outcomes to determine the potential outcomes in present and future hybrid work.

Our methodological approach is hermeneutic (Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2014) and can also be described as abductive by nature regarding the research process. The body of hybrid work knowledge continuously and gradually developed even as the study progressed, which increased our understanding and insights and helped to develop the contents for a more advanced hybrid work model. The details of the study and analyses are available in the technical report (Vartiainen and Vanharanta, 2023).

4 Hybrid work in professional discussion

Extensive previous literature on flexible forms of working consists of conceptual and empirical studies and practice-oriented professional publications (Vartiainen, 2024). First, we focused on professional discussions. During the pandemic in 2020–2022, discussions on hybrid work concepts emerged in the publications of consulting companies, international organizations, and business journals. This literature typically raises challenges and proposes guidelines for implementing and working in flexible work arrangements.

4.1 Material and its analysis

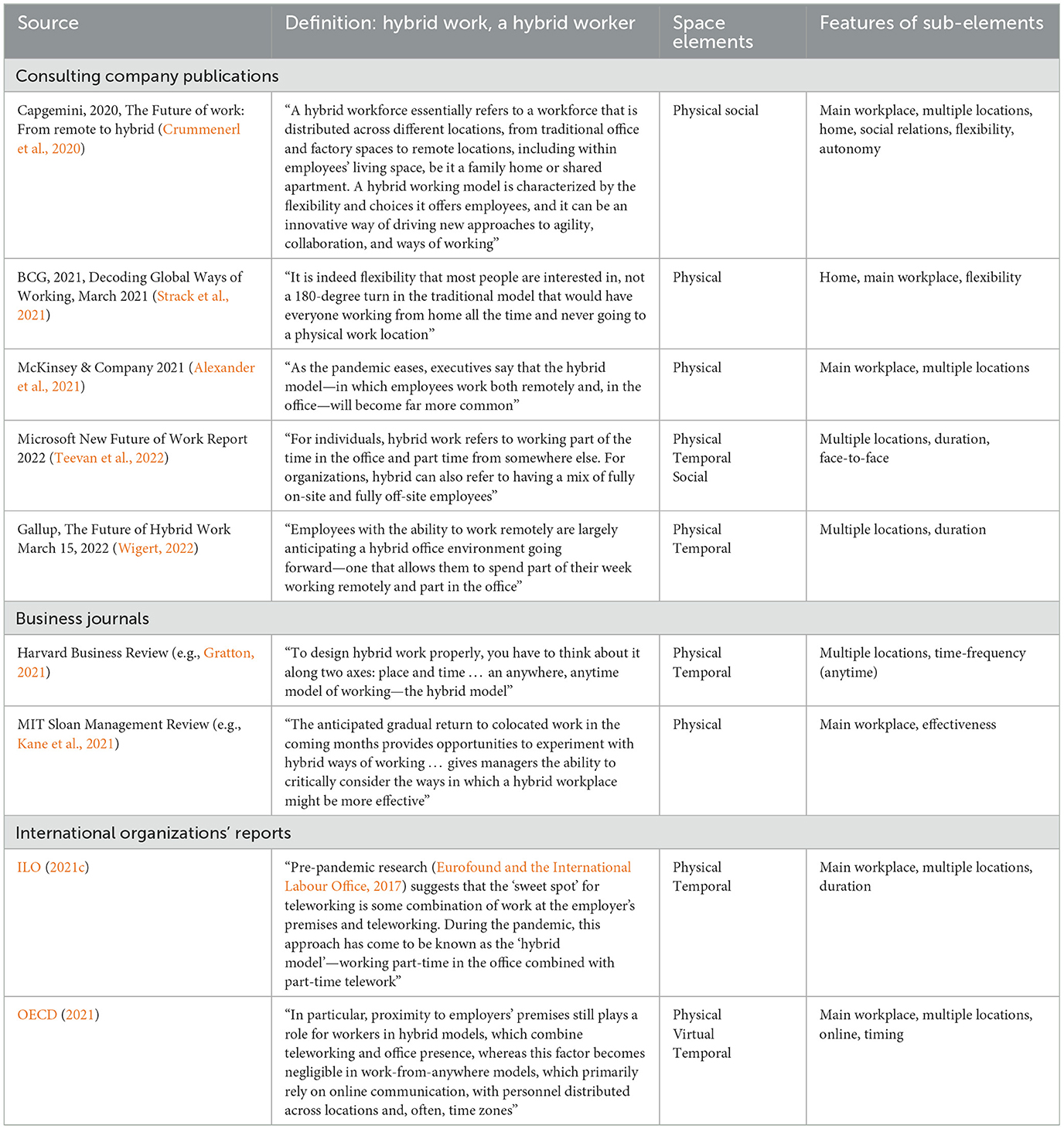

We collected a sample of such works to determine how hybrid work has been defined.2 The articles were read, paragraphs mentioning the definition of hybrid work and related concepts were searched, and the content was described in terms of the basic elements and sub-elements of hybrid work and their features (Table 1).

Table 1. Examples of hybrid work definitions by consulting companies, business journals, and international organizations during the pandemic (modified from Vartiainen and Vanharanta, 2023, 26–27).

4.2 Hybrid work definitions in professional discussion

The resulting comparison shows that physical space was the major element used in the definitions of hybrid work, referencing a flexible mixture of locations—working both on the employer's premises and elsewhere remotely. In addition, the temporal element was used, i.e., to indicate when, how often, and for how long work is done in different places. For some reason, social and virtual spaces were seldom mentioned. However, additional features, such as flexibility, agility, and the use of autonomy by both employers and employees, were mentioned. These features specified the contents of space elements and enlarge the hybrid work concept beyond physical, time, and social aspects to mental attributions.

5 Hybrid work in European discussion

Secondly, to explore how different actors and institutions in Europe defined hybrid work during the pandemic, we analyzed extensive data collected from all EU-27 member states. Below, we describe this data, the analysis process, and the findings in more detail.

5.1 Material and its analysis

The data from Europe (EU) were collected through a standardized questionnaire (Appendix 1) circulated to the Network of Eurofound Correspondents (NEC) covering all EU-27 member states from 15th December 2021 to 7th January 20223 (Eurofound, 2023a). The questionnaire, accompanied by a short note informing recipients of the context of the questionnaire, asked a correspondent in each country to collect data about:

• Existing definitions of hybrid work or similar concept(s) referring to the situation in which work is performed partly from the employer's premises and partly from other locations, indicating the original designation(s), its source(s), and the main differences among different concepts, if applicable.

Data were received for all 27 EU member countries, i.e., 27 country-specific reports, including rich materials. They included the correspondents' summaries based on available statistics, regulations, legislation documents, court decisions, collective agreements, media discussions, and extant literature, as well as interviews in the case of some countries. The length of country reports varied from eight to 19 pages. The country reports included much secondary material, i.e., links to various documents that were also downloaded. This supplementary material consisted of 246 documents, including research reports by various research institutes and other public and private organizations, guidelines and statements by social partners and government organizations, descriptions of telework practices by the government and other public and private organizations, information on updates to telework legislation, and online articles discussing the related experiences, plans and views of organizations and HR professionals. To give a few examples, the documents included, among others, an employment prospects survey carried out by ManpowerGroup in Greece, a proposal for changes in teleworking legislation by a Finnish trade union (AKAVA), and an online article published by Ireland's National Television and Radio Broadcaster, RTÉ, on HR professionals' views on hybrid work.

Our content analysis proceeded using Atlas.ti software that is a workbench for the qualitative analysis of large bodies of text, graphics, and audio and video data. First, the sources mentioning hybrid work or a similar concept and who mentioned them were identified in the country reports. Then, the core content of each definition was coded into basic and sub-elements, as well as the features of hybrid work, as described above. Not all reports explicitly mentioned “hybrid work”; instead, traditional remote work and telework definitions were often used.4 We did not include these reports in this analysis because of their explicit commitment to the traditional remote and telework definitions. However, we searched for similar concepts resembling hybrid work and analyzed their contents. This process generated an understanding of how the concept of HW is construed differently by various actors and what the main elements of HW are in current discussions in EU member states.

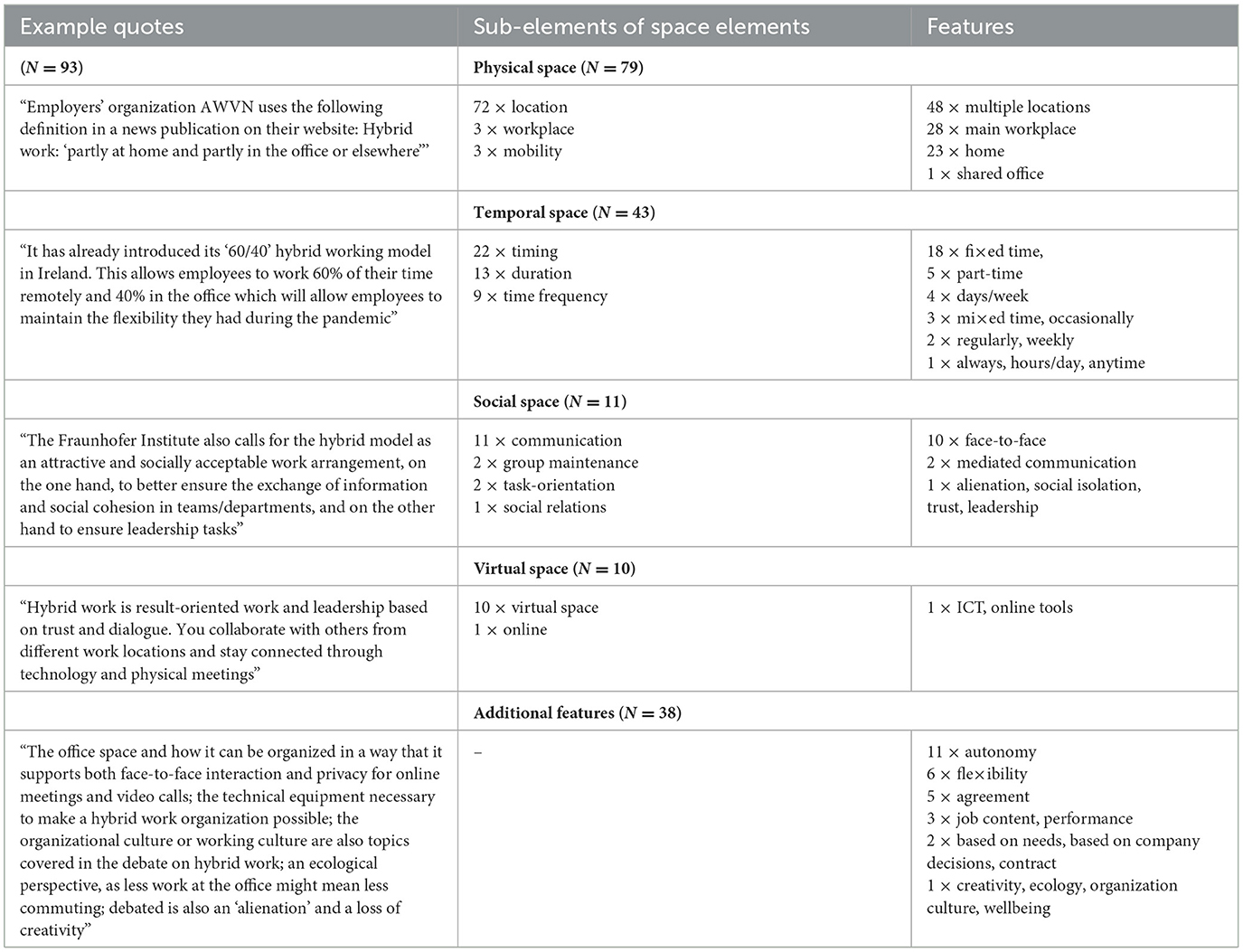

5.2 Hybrid work definitions in Europe

We identified 93 definitions of hybrid work from the country reports and supplementary material (Table 2). Physical and temporal elements were again the most commonly used to define hybrid work. Social space, virtual space, and their sub-elements were sometimes used.

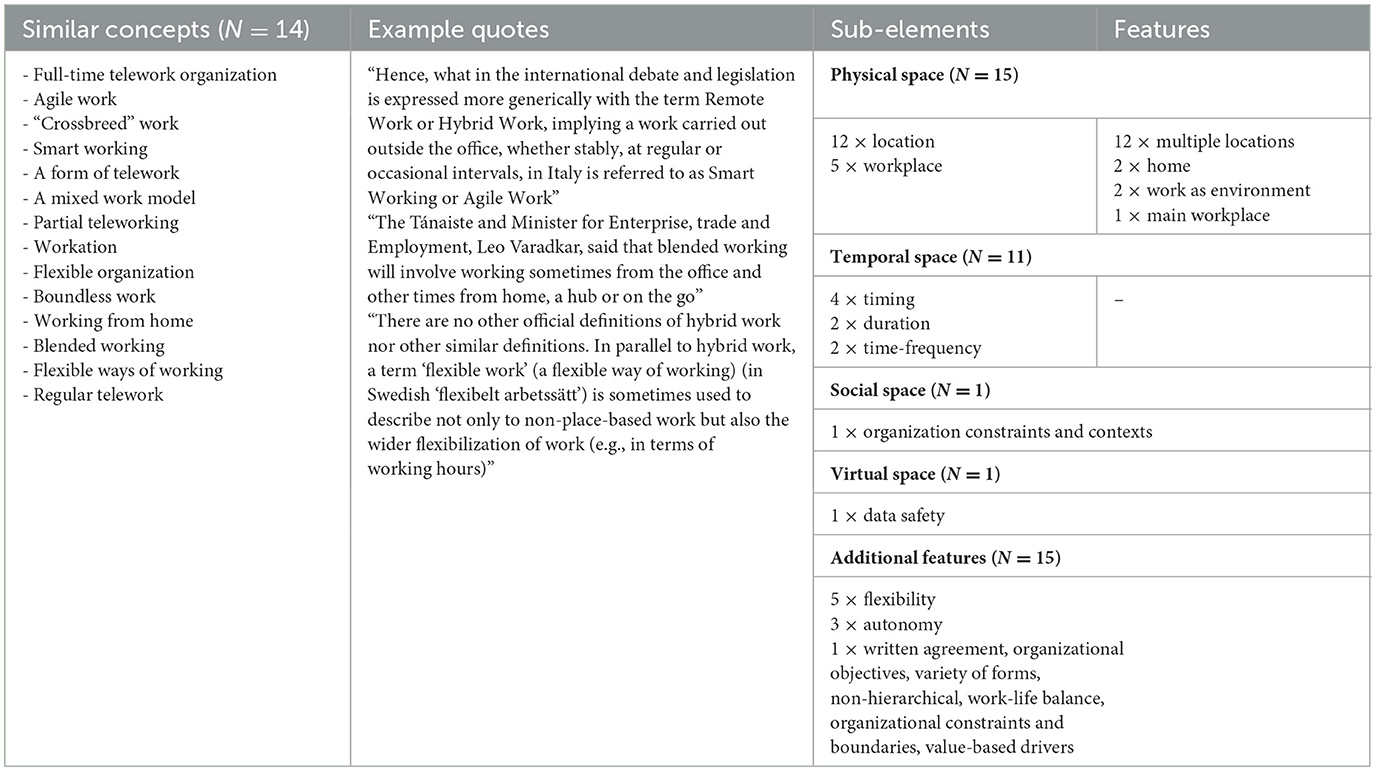

Table 2. Examples of typical hybrid work definitions (N = 93) and the number of elements, sub-elements, and features mentioned in the excerpts from the correspondents' reports (Vartiainen and Vanharanta, 2023, p. 29).

Physical space was described in terms of working in multiple locations, especially at the main workplace and home. The quality of workplaces in different locations was almost not discussed at all. Time was another defining element in answer to the questions of when, for how long, and how often work took place. This meant working at fixed times during the week, month, or year at the office and remotely, for example, three office days and two telework days each week. Social space was discussed regarding how communication and collaborative interaction were arranged. Usually, the meaning and significance of face-to-face contact were underlined, and sometimes, they were related to building trust and leadership and avoiding social isolation and alienation. Virtual space was also sometimes—though not in all cases—referred to as the basic element of hybrid work. Autonomy, flexibility, agreements, and contracts were additional features in hybrid work. It was also expected that employees' needs, organizational culture, wellbeing, and ecological issues would be considered when designing and organizing hybrid work, including job content and performance.

5.3 Similar concepts

We also explored whether hybrid work has been defined without explicitly using the concept of hybrid work in the country reports with a resembling concept. We found 16 citations with altogether 14 different concepts. For example, “smart working,” “agile work,” “flexible work,” and “blended working” were defined with the same basic elements as hybrid work and mostly in terms of the physical space, time, and virtual space elements, as shown in Table 3. The physical space of work in the future was characterized as working in multiple locations, at home, and at the main workplace. In terms of time, this was characterized by decisions about when work would take place (“timing”) and for how long time (“duration”). Virtual space was only referred to in terms of data safety. In addition, future work was defined as having different forms and being autonomous, flexible, and non-hierarchical. In some additional definitions, it was also described as being based on the organization's goals, values, and written agreements and crossing its constraints and boundaries. For example, one respondent defined “workation,” referring to working in distant locations, as follows:

A working model in which the employer arranges for employees to work abroad or in a resort city in the same country, where part of the time is devoted to doing work, part of the time is devoted to professional self-development, and part of the time is for rest.

Table 3. Examples of similar concepts to hybrid work in additional definitions, and the number of elements, sub-elements, and features in the correspondents' reports (Vartiainen and Vanharanta, 2023, p. 30–31).

In all, it can be concluded that the definitions of hybrid work and similar concepts at the EU member state level typically mention physical and temporal space elements, sub-elements, and features. Even when the concepts differed, their content was similar. For example, “blended working” was defined as working sometimes from the office and other times from home, at a hub, or on the go. This definition is reminiscent of the concept of multilocational work.

5.4 Hybrid work vs telework

The long history of remote work and telework (Nilles et al., 1976; Vartiainen, 2021a,b) has surfaced many types of “new ways of working,” such as telecommuting, telework, ICT-based mobile work, and online work on platforms. They have been continuously implemented and, therefore, been thoroughly reviewed and previously discussed and studied over the last several decades. However, we ask if the traditional definitions and their operationalization compare with the definitions in hybrid work discussions during the pandemic and if they are enough after the pandemic.

When we compare the hybrid work definitions in the recent discussions and country reports with the earlier definitions of remote work and telework, we can see that they use the same basic elements. However, the former is even more streamlined, as shown below.

The European Framework Agreement (ETUC et al., 2002) defines telework as

A form of organizing and/or performing work, using information technology, in the context of an employment contract/relationship, where work, which could also be performed at the employer's premises, is carried out away from those premises on a regular basis.

This definition of telework includes physical space (location), virtual space (ICT), and time (time-frequency) elements in addition to referring to a feature of an employment contract/relationship.

Later, telework and ICT-based mobile work were defined (Eurofound, 2015; Eurofound and the International Labour Office, 2017; Eurofound, 2020, p. 1) as

Telework and ICT-based mobile work (TICTM) is any type of work arrangement where workers work remotely, away from an employer's premises or fixed location, using digital technologies such as networks, laptops, mobile phones and the internet.

The International Labor Organization (ILO, 2020b, p. 6) defined telework as

A subcategory of the broader concept of remote work. It includes workers who use information and communications technology (ICT) or landline telephones to carry out the work remotely. Similar to remote work, telework can be carried out in different locations outside the default place of work. What makes telework a unique category is that the work carried out remotely includes the use of personal electronic devices.

These definitions of remote work and telework, and ICT-based mobile work include only physical space (excluding the main workplace) and virtual space (ICT) elements in addition to flexible arrangements.

We can conclude that virtual and social elements are almost entirely missing in the definitions of hybrid work produced during the pandemic. Although the newer definitions include virtuality, they are evocative of the “classical” definitions of remote work, telework, and ICT-based mobile work. However, some additional features were proposed and used in the definitions of hybrid work during the pandemic. First, the newer definitions added the features of flexibility and autonomy in arrangements of physical and temporal spaces. Second, they characterized hybrid work with more detailed—but individualized—features. These individualized features highlight the need to develop contracts and agreements, prevent isolation and alienation, support wellbeing, work-life balance, and creativity, and invest in developing leadership. This indicates that changing job responsibilities and working environments impact how hybrid work is defined, designed and implemented in organizations and practiced in a localized and flexible manner. Finally, the additional features also reflect the potential and opportunities of hybrid work.

6 Expected wellbeing and performance outcomes in hybrid work

Thirdly, we sketched the potential wellbeing and performance outcomes of present and future hybrid work by reviewing prior empirical remote and telework literature on wellbeing and performance. Wellbeing reflects the effects of basic contextual elements on an individual's mental state and is simultaneously a resource for performance. Smooth performance, on the other hand, reflects the success of hybrid work arrangements from the point of view of the organization's management. They are both indicators of the functional success of hybrid work. We do not yet know much about the wellbeing and performance outcomes of existing hybrid work models. Therefore, we can mainly rely on available empirical-based reviews about the wellbeing and performance outcomes of traditional remote, telework, and home-based remote work before and during the pandemic.

6.1 Material and its analysis

We collected a sample of literature reviews (N = 14) about traditional remote and telework outcomes. The available reviews have been conducted in many ways (Pericic and Tanveer, 2019). Three main review types are (Donthu et al., 2021, p. 287): systematic literature review, meta-analysis, and bibliometric analysis. A systematic literature review summarizes and synthesizes the findings of existing literature on a research topic or field. Meta-analysis summarizes the empirical evidence of a relationship between independent, intervening, and dependent variables while uncovering relationships not studied in existing studies. Bibliometric analysis summarizes large quantities of data to present a research topic or field's intellectual structure and emerging trends. Typically, a thorough search strategy for data involves multiple databases, articles, dissertations, conference proceedings, abstracts, and sources of gray literature. In the oldest reviews of our sample, the data was manually collected and analyzed systematically, and their contents were compared. In most systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the analysis followed the (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2010) to ensure the quality of the review.

Our own review was done manually by selecting examples of review articles published before, during, and after the pandemic. The following items were identified in each review: the objective or research question, the analysis method, including the number of types of data, measures of telework and wellbeing and performance outcomes, and the findings concerning them. Our sample review articles also include information about the impacts of intervening variables as mediators or moderators, e.g., autonomy, isolation, perceived autonomy, lower work-family conflict, etc., on outcomes. However, these dependencies are not reported in this article.

6.2 Telework, wellbeing and performance

The findings reported in this article only concentrate on telework's wellbeing and behavioral outcomes, i.e., performance, effectiveness, and productivity, answering the question: What are the potential wellbeing and performance outcomes of hybrid work? The main variables are telework, wellbeing, and performance.

6.2.1. Telework

Traditionally (e.g., Bailey and Kurland, 2002; Gajendran and Harrison, 2007), telework is defined as an alternative work arrangement in which employees perform tasks elsewhere that are normally done in a primary or central workplace, using electronic media to interact with others inside and outside the organization.

6.2.2. Wellbeing

Taris and Schaufeli (2015) conceptualized wellbeing at individual levels on two dimensions: (1) wellbeing as a context-free, e.g., general quality of life, or as a domain-specific concept, e.g., work-related wellbeing, and (2) wellbeing as an affective state or as a multi-dimensional construct. Context-free (or global) measures of affective wellbeing often consist of scales whose items refer to a range of positive, e.g., excited and inspired, as well as negative, e.g., hostile and nervous, states. Because hybrid work can be especially multi-faceted and appears quite complex, the domain-specific and multidimensional conceptualization of wellbeing is preferable in remote, telework, and hybrid work. In an example of the domain-specific multidimensional conceptualization of work-related wellbeing, Van Horn et al. (2004) distinguished five dimensions: the affective dimension of wellbeing at work, e.g., job satisfaction; the cognitive dimension, e.g., ability to concentrate at work; the professional dimension, e.g., autonomy; the social dimension, e.g., quality of social functioning at work; and the psychosomatic dimension, e.g., health complaints. The review articles used mostly the domain-specific multidimensional conceptualizations of wellbeing.

6.2.3. Performance

Performance and productivity are the key concepts to measure and evaluate behavioral outcomes. Performance is of high economic interest to organizations. Taris and Schaufeli (2015, p. 21) distinguish between process performance, i.e., what is done and how it is done, and outcome performance, i.e., whether these actions achieve the intended goal. The outcome performance can also be defined with the term “effectiveness.” It is measured subjectively based on employees' perceptions of their performance, those of their colleagues, or the employer's assessment. An objective measurement relies on the actual outcomes of performance, i.e., the number and quality of concrete products or services. For example, Bloom et al. (2015) measured the performance of home-based order takers as teleworkers by comparing the number of phone calls answered and the number of orders taken. Productivity is a ratio of output (O) and input (I). Productivity was measured by calculating phone calls (O) answered per minute (I).

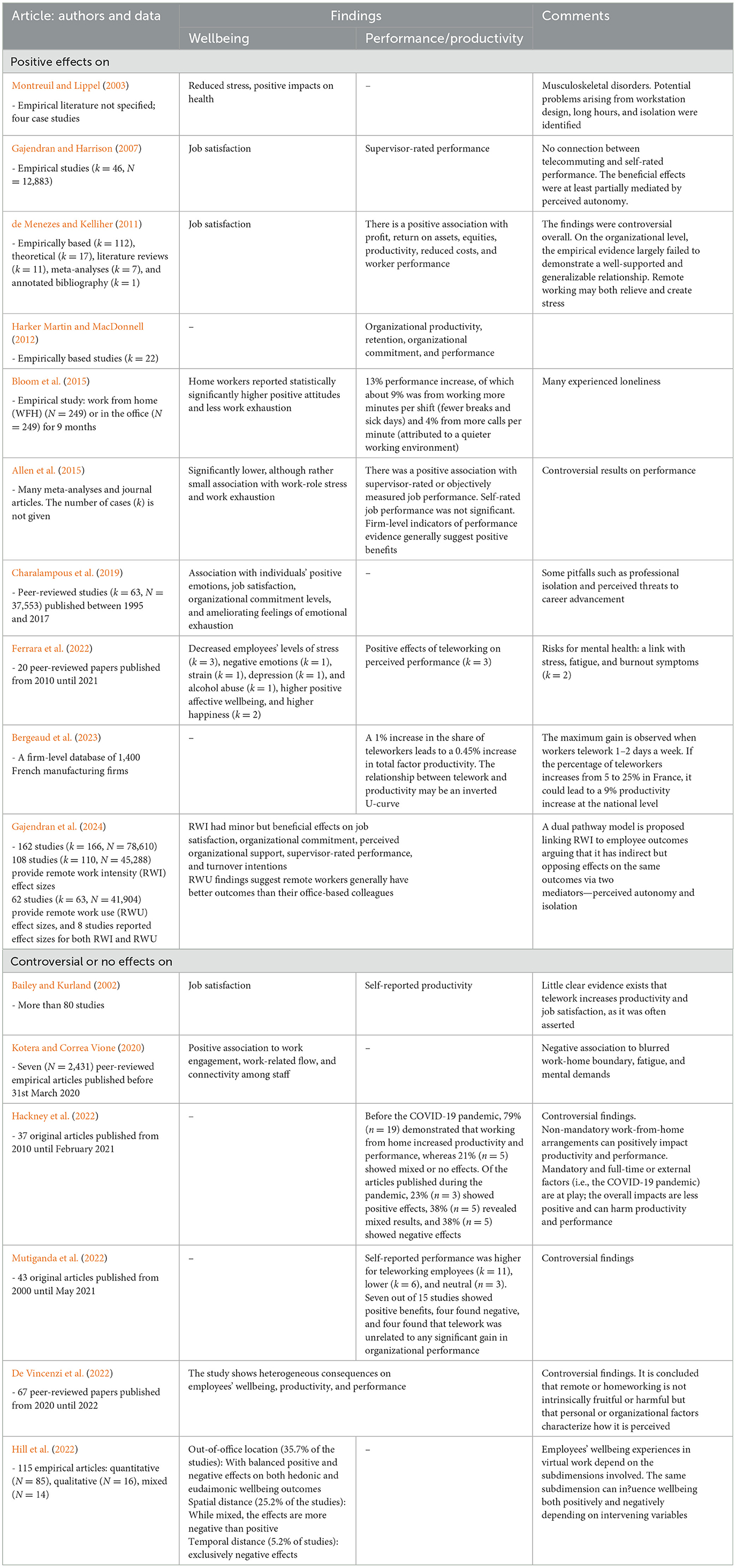

6.3 Wellbeing and performance outcomes

In the reviews, telework as the independent variable was operationalized traditionally as working outside the conventional workplace and communicating with computer-based technologies. However, its metrics varied. Remote work intensity (RWI), e.g., days of the week and part-time and full-time work, was used often as the measure, in addition to time and location flexibility, spatial and temporal distance, working at home, and multi-locality. Wellbeing as the dependent variable was operationalized in the review articles mostly as domain-specific and multi-dimensional phenomena. For example, measures include job satisfaction, health, e.g., musculoskeletal problems, work exhaustion, affective and social wellbeing, loneliness and isolation, psychosocial risks and technostress, burnout, and the quality of the work-family interface. Self- and supervisor-reported and objective ratings were used to measure performance. On the organizational level, financial outcomes, absence, labor turnover, the quality of goods and services, and commitment were used as indicators of performance outcomes. Table 4 shows that reviews (n = 14) inform telework's positive, however, mostly controversial impacts on wellbeing and performance.

Table 4. Summary of the review article sample (N = 14), including the effects of telework on wellbeing and productivity/performance.

Positive wellbeing outcomes on the individual level were shown as job satisfaction (N = 6/14), reduced stress, strain, and exhaustion (N = 5/14), increased positive emotions, affective attitudes, work-related flow, and happiness (N = 5/14). On the organizational level, the positive wellbeing outcomes were seen in organizational commitment, work engagement, and support (3/14). One review shows no effects on job satisfaction (Bailey and Kurland, 2002), while another has mixed but primarily negative wellbeing outcomes (Hill et al., 2022). Positive impacts were noticed in organizational performance and productivity (N = 5/14) and supervisor-reported (N = 3/14), self-reported (N = 2/14), and objective (N = 2/14) performance.

Almost all reviews informed about controversial outcomes and their reasons in addition to positive results. In terms of wellbeing, long working hours can cause musculoskeletal disorders, and blurred work-home boundaries may increase fatigue and mental demands, risks to mental health, professional isolation, and feelings of loneliness. There were also controversial results regarding performance, such as differences in self- and supervisor-rated performance. Similar limited evidence has been found in other systematic reviews (Crawford, 2022; Vleeshouwers et al., 2022). For example, Vleeshouwers et al. (2022) reviewed how telework from home affects the psychosocial work environment. They found limited overall evidence rated as either low or very low quality. However, flexibility and autonomy were discussed as potential mediating variables in the relationship between WFH and the psychosocial work environment. They also note that telework from home is not a homogeneous construct. It may cover differing work situations, such as the number of hours worked from home, tasks performed, or job type. This may also limit the generalizability of findings. Moreover, the included studies showed significant variation in how several work environment factors were defined.

Overall, there are many reasons behind the controversial empirical findings. It is too simplistic to claim that remote and telework are related to positive—or negative—outcomes without knowing the practical arrangements of hybrid work in target organizations. In practice, hybrid work—and remote and telework—are flexible configurations, as stated above. How they are arranged depends on the organization's purpose, contextual demands, and available resources, including employees' needs. It may be that some critical work elements, sub-elements, or features have remained in shadow when designing the research settings: “one research design does not fit all empirical studies.”

7 Flexible hybrid work

7.1 Flexible work arrangements

Now, a question arises: Are the above-described four elements—physical, virtual, social, and temporal—enough to define, design, and implement hybrid work and explain its outcomes such as wellbeing and performance? The literature and survey data analysis findings show that hybrid work's potential basic elements, sub-elements, and features were only partly used in the hybrid work definitions and operationalizations during the pandemic as shown in two middle circles in Figure 3. So, based on that, there are even too many elements in the model if we consider the discussions reflect the reality of hybrid work implementations. However, the content analysis also showed that many new features (outer circle in Figure 3) were proposed to be considered in planning and implementing hybrid work. This suggests that actors close to the practice saw hybrid work as a promise for flexible work arrangements, not simply as working on-site and elsewhere, possibly using communication technologies for collaboration. This also confirmed our proposition about the diversity of hybrid work as its true nature.

Figure 3. An extended hybrid model: The main elements, sub-elements, and features of hybrid work and related characterizations in country reports and in the literature (inner circles) and the proposed additional features (outer circle).

The suggested new features to be considered first underline the flexibility of such arrangements in terms of physical and virtual space and time. Second, they characterize hybrid work in more detail, such as using multiple and different types of locations for working. In addition, individually perceived Autonomy is considered important, and written agreements on how work can be arranged at the individual, team, and organizational levels were underlined. Attention was also given to organizational values and objectives as drivers when deciding on which form of hybrid work would be implemented and applying it, nor were organizational constraints and boundaries, data safety, and work-life balance forgotten. This shows that changes in work content and job demands (Bakker and Demerouti, 2017) affect how hybrid work is planned and implemented in practice in local organizations flexibly, customized, and in ways appropriate to the context. Finally, the ability to adjust multiple features also reflects the future potential of hybrid work; there are not only two or three types of hybrid work—more options are available.

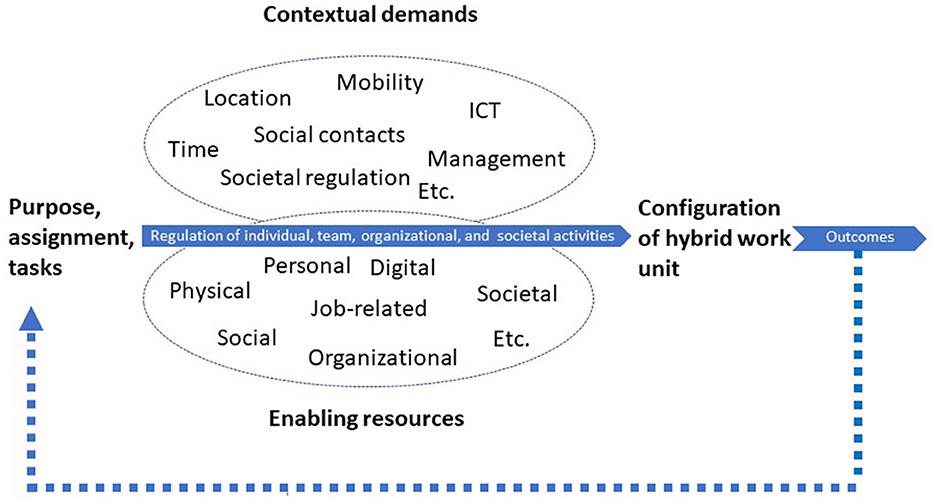

7.2 Hybridizing mechanism

The type of hybrid work is configured during its design and implementation process. The hybridizing mechanism (Figure 4) shows the main factors influencing the configuration of hybrid work units from the available elements, sub-elements, and features. When a hybrid work unit is seen as a working system within a larger environment, its specific mandate, structure, form, and work process itself, with its wellbeing and performance outcomes, are largely determined by three intertwined and partly embedded factors: the purpose of the work in an organization, the hindering or enabling demands of its context, and the available resources.

Figure 4. Generic hybridizing mechanism: Factor sets (i.e., purpose, content, resources) and their elements and features influence the configuration of a hybrid work unit (e.g. a team working in a hybrid manner) and its potential outcomes.

An individual or a collective actor guides the hybridizing mechanism. In work organizations, an actor—on different levels (an individual, a team, an organization, a society)—strives to operate purposefully in its environment by regulating actions by balancing present environmental demands and using available resources for goal achievement. The practical implication of this reasoning is that each organization or even team can build its model and implement its hybrid work practices by combining and integrating the basic elements, sub-elements, and their features, as well as additional ones if needed.

Organizations do not exist without some purpose. Common goals characterize the organization's purpose, and joint efforts and commitment from its members are expected to be generated to achieve them. Usually, the objectives are set by the organization's management, with or without consulting employees, and are related to productivity and economic outcomes. The organization's values, such as sustainability, often justify profit expectations. On the other hand, individuals are guided by their basic psychological needs, such as autonomy, competencies, and social relations with others (Deci and Ryan, 2012). On the individual and team levels, the organizational objectives define the complexity of individual and collective assignments and tasks, i.e., is routine and/or creative task execution required in work? Bell and Kozlowski (2002) claimed that task complexity has critical implications for the structure and processes of teams. Analogously, the content of tasks influences the structure and workflow of the hybrid work unit and the resources needed to regulate work activities. It is evident that goal setting, values, and needs impact the elements and features needed to develop and implement hybrid work arrangements. The wellbeing and performance outcomes of an individually or collectively regulated work process can be used as evaluation criteria of hybrid work arrangements' sustainability, i.e., whether the elements used to suit their features and whether the resources are sufficient.

8 Discussion

Our analysis of hybrid work definitions presented in the professional publications and country reports during the pandemic shows that the physical space element—remote work in multiple locations and working at the main workplace—and the temporal element, i.e., when, for how long, and how often work is done in each location and workplace, are the elements most frequently used to characterize hybrid work. These definitions include social and virtual elements only occasionally. It seems that the discussion during the pandemic and after it has been dominated by traditional remote work and telework concepts, although some additional job features are available. This discussion has also stabilized the present discussion of hybrid work unilaterally to concern working onsite and occasionally elsewhere. However, hybrid work has more options.

8.1 The core nature of hybrid work

We consider flexibility to be the core nature of hybridity. Hybridity is a heuristic way to flexibly organize work and its preconditions to meet expected changes, such as product and market changes, and unexpected changes, such as pandemics, natural disasters, and conflicts. The need for flexibility and hybrid solutions in specific jobs, tasks, and working contexts for individuals, teams, projects, and whole organizations requires tailoring hybrid work elements and their features on a case-by-case basis. Its form depends on an organization's agreed purpose and goal, contextual demands, available resources, and the needs of employees. Therefore, traditional remote work and telework are just specific forms of hybrid work, as it is possible to combine the above-mentioned elements with their designable features flexibly. For example, traditional telework combines certain physical, temporal, and virtual elements and their features. Thus, it could be logically reasoned that other types of remote work and telework are just specific types of hybrid configurations, and even manual work can include hybrid elements; for example, an artisan might design products using 3D design software and manufacture them by hand at home. The potential for variety in hybrid work increases even more when hybridity at the team and organizational levels is considered. In a sense, the concept of hybrid work is vague and almost empty if its contents are not described and defined by using its concrete sub-elements and features.

The hybrid work model is systemic as it consists of interrelated components. Typically, a systemic approach is used to identify a system's basic, designable, functional, and concrete elements; this involves analyzing the differences among activity systems, their environment, and interaction. The meaning of hybridity in each case is determined by the observer's understanding of the nature of the system and the ways it adapts to its environment, utilizes its features and resources productively, and successfully develops work processes, including creating new processes. Work processes are goal- or purpose-driven and individually or collectively regulated. The systemic approach opens possibilities to discuss “hybridity” on the individual, team, organization, and societal levels, as these can all be seen as active “systems” in their respective environments. A hybrid workplace is “systemic” in that it consists of “two or more things” that interplay with each other. As Besharov and Mitzinneck (2020, p. 3) argue, “to achieve both analytical rigor and real-world relevance, research must account for variation in how hybridity is organizationally configured, temporally situated, and institutionally embedded.”

8.2 Practical implications

Today, the transformation of hybrid work continues, and it is a moving target. However, some “normalization” is occurring. Employees have partly returned to their main workplace after being forced to work remotely from home, often blending remote work flexibility with on-site work, and typically working remotely 2 days a week (Barrero et al., 2021). Many large companies and state and municipal organizations have formulated organization-wide hybrid work policies, giving some framework to tailored and localized work arrangements on the team and individual levels. Micro-, small, and medium-sized companies have quickly adapted to the new reality and organized activities flexibly. Surveys worldwide show that the trend of flexible hybrid work arrangements is expected to continue (Aksoy et al., 2023).

The transition is not always smooth, and some jolts are expected, as are some unanswered questions. Many open questions appear as challenges and ambivalent tensions, such as isolation, loneliness, and longing for colleagues in fully remote work, and what are the performance outcomes. Another tension is whether online interaction can substitute face-to-face interaction or if the two are complementary. In hybrid work, at least some collaboration occurs online using still-developing technologies. A third tension is that hybrid and fully remote work leads to lower office demand. This is a challenge to property owners—what should be done with extra office premises? One of the societal challenges is that remote-capable or teleworkable jobs constitute only part of the workforce, and not all workplaces can flexibly organize their activities. Many frontline employees in service positions, such as nurses in health care and salespersons in shops, need close, face-to-face contact with their clients. Manufacturing products on the shop floor often requires a full-time presence or at least the keen attention of an employee. This difference may lead to the “hybrid work divide,” creating a group of privileged professions that enjoy autonomy and flexibility. In contrast, other groups are strictly tied to in-person work processes (Eurofound, 2023b). However, from the perspective of hybrid work as a combination of “two or more things,” these professions could also benefit from considering work content as a combination of basic work elements, sub-elements, and their features. It is possible to reformulate such jobs by rebuilding their structure to include previously missing elements and their features.

The types of hybrid work that appeared after the pandemic will determine what resources are needed to address the current situation. It seems evident that hybrid work will be a flexible mixture of using various places—including the home and main office—as digitalized workplaces. Flexible work models have many forms, as their implementation depends on the purpose and goals of the work, the work processes involved, and employees' needs. The location and workplace are important: work is done flexibly in physical and virtual spaces. Time is also important: work is carried out from 8 am to 4 pm or 24/7 as synchronous and asynchronous solo work or with one or more people. Leaders should manage their time and ensure sustainable working conditions that is their employees do not overload themselves and can cope with their job demands. Communication in hybrid work will occur both face-to-face and in a digital manner. Technology's role is crucial as an enabler of collaboration, knowledge-seeking, and elaboration in solo work. Hybrid work essentially includes collaboration consisting of both task- and relationship-related communication. Members of the same or different organizations will work interdependently in purely virtual or hybrid contexts where individuals communicate via e-mail, videoconferencing, teleconferencing, and other virtual interactions.

The characteristics involved in designing a hybrid work system can be clustered into the following:

• Designable basic elements such as the location and physical premises of the workplace, time arrangements, social structure and relations, and available digital tools and platforms.

• Negotiable secondary features include decisions about arrangements and implementation, agreements about relevant mechanisms, management styles, leadership and working practices, and necessary competencies.

• Tertiary features emerging from hybrid work processes and their implementation, such as tensions and contradictions, require reflection and dialogue among involved actors.

• Outcome features such as wellbeing, performance, effectiveness, and productivity are based on how the primary, secondary, and tertiary feature elements are realized. And, they can be used as the measures of the design success.

How and in which order design and implementation finally happen depends on an organization's culture and values, decision-making traditions, and present practices. This implies that the design and implementation can start from the expected outcome features, for example, by aiming to identify the best hybrid work composition to ensure the wellbeing and performance of employees.

Hybrid work has many manifestations as a flexible way of organizing work. We do not yet know the functional outcomes of different combinations of hybridity. At present, rather few studies about this topic have been conducted and published, but their number is increasing. Most concern remote work and telework from home and at the office, with a lack of attention to other elements. There is a need to cluster, measure, and evaluate hybrid work solutions, even though they are heterogeneous. What common indicators can be used? A reality test of implemented hybrid solutions could provide a starting point for considering various indicators. The basic elements, sub-elements, and features used should be described in each case. In addition, data should include information about wellbeing and performance outcomes on the individual, team, and organization levels; job demands, and available resources used; organizational goals, purpose, and values; and individual needs and resources. Based on this information, conclusions for team- and organization-level agreements can be established and refined, as can the need for relevant regulation and legislation.

8.3 Future of work

In the future, the development and growth of telework and remote and digital online work will be tightly integrated with the development of technologies, expanding 5G bandwidths and emerging 6G bandwidths, artificial intelligence (AI) applications, 3-D working environments, and ever-smarter mobile devices. Through broadband mobile internet and digital labor platforms, there is access to multiple communication functions, including email, the internet, instant messaging, text messaging, and company networks. It is evident that digitalization changes the working environment, impacts working processes, tasks, and job content, and affects structures and organizations, products, and services in many ways, resulting in the need for new competencies, organization, and ways of working (Schaffers et al., 2020).

Some authors have outlined the future of post-pandemic work for organizations and individuals (Rhymer, 2023). For example, Malhotra (2021) expects that knowledge work will increasingly be performed virtually, from switching to telework during the pandemic. The structure of organizations is expected to become more open, engaging external independent freelancers outside the organization to work together on an ad hoc basis. An individual may work as part of multiple teams and on temporary projects. Therefore, individuals can and will have multiple reporting lines, and organizations will become more matrixed. For individuals, Malhotra highlights changes in locational, temporal, and goal-related autonomy. However, according to him, the future of work will create challenges for organizations—and individuals—such as maintaining organizational culture and identity, monitoring performance, motivating dispersed employees, providing learning feedback, enabling work-life balance, and fostering social inclusion.

Indeed, recent developments have resulted in several new types of organizations and jobs—some hybrids of old elements and some completely new. On the organizational level, there are examples of “all remote” dispersed companies. For example, Choudhury et al. (2020, p. 2) describe the company “GitLab,” which does not have a physical office but employs 1,000 people in more than 60 countries. An organization is typically the context where hybrid work is organized.

Other examples of completely remote organizational configurations include freelancers on online and offline platforms. Although the number of platform workers is still low, it is growing, mainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic (ILO, 2021b). For example, the Online Labor Index (OLI) produced by Kässi and Lehdonvirta (2018, see also Kässi et al., 2021) showed that in May 2021, the number of projects started on platforms increased by 93% from May 2016. A recent white paper (World Economic Forum, 2024, p. 7) aimed to identify jobs that can be performed from anywhere in the world. The jobs were deconstructed into tasks, and assessed whether these tasks could be performed from anywhere. Global digital jobs and a global digital workforce were defined (p. 7) as “jobs and workforces distributed across borders in different geographies, empowered by digital tools to perform their tasks, connect, and communicate globally.” Two hundred eighteen job types out of 5,400 were conducive to becoming global digital jobs, i.e., 73 million workers out of the 820 million global workers represented by the International Labor Organization (ILO)'s occupation employment statistics. By 2030, these jobs were expected to rise to around 92 million.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MV: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. OV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Across the Asia Pacific, 2,170 leaders participated in the Hybrid Leadership survey from Australia and New Zealand, India, Indonesia, Japan, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, and some other countries. In addition, 27 senior executives were interviewed.

2. ^This included material from Accenture, the Adecco Group, the ADP Research Institute, Boston Consulting Group, Deloitte, Gallup, Gapgemini, Howspace, KPMG, McKinsey & Company, and Microsoft; Harvard Business Review, MIT Sloan Management Review; ILO, and OECD.

3. ^Eurofound is the EU Agency for the improvement of living and working conditions. Eurofound has at its disposal a network of national correspondents, based in all Member States plus Norway. The correspondents usually work in research units of universities and institutes. Input from the correspondents supports Eurofound's research by gathering, analysing and reporting on specific developments (policies, practices and regulations) in the EU Member States. Alongside these regular inputs, national correspondents also provide national information related to specific research questions such as hybrid work, which are either published in a comparative overview or feed into larger-scale research reports.

4. ^According to the European framework agreement on telework from the year 2002, teleworking is “a form of organizing and/or performing work, using information technology, in the context of an employment contract/relationship, where work that could be performed at the employer's premises is carried out away from those premises on a regular basis.” See https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/industrial-relations-dictionary/telework.

References

Aksoy, C. G., Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., Davis, S. J., Dolls, M., Zarate, P., et al. (2023). Working from home around the globe: 2023 Report. Available: https://wfhresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/GSWA-2023.pdf (accessed July 18, 2023).

Alexander, A., Cracknell, R., De Smet, A., Langstaff, M., Mysore, M., Ravid, D., et al. (2021). What Executives are Saying about the Future of Hybrid Work. New York, NY: McKinsey Global Publishing.

Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D., and Shockley, K. M. (2015). How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 16, 40–68. doi: 10.1177/1529100615593273

Andriessen, J. H. E. (2003). Working with Groupware: Understanding and Evaluating Collaboration Technology. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-0067-6

Bailey, D. E., and Kurland, N. B. (2002). A review of telework research: findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. J. Organ. Behav. 23, 383–400. doi: 10.1002/job.144

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 273–285. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N., and Davis, S. J. (2021). Why Working From Home Will Stick (April 22, 2021). University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2020-174. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3741644

Bell, B., and Kozlowski, S. (2002). A typology of virtual teams: Implications for effective leadership. Group Organ Manag. 27, 14–49. doi: 10.1177/1059601102027001003

Bergeaud, A., Cette, G., and Drapala, S. (2023). Telework and productivity: insights from an original survey. Appl. Econ. Lett. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4015066

Besharov, M., and Mitzinneck, B. (2020). “Heterogeneity in organizational hybridity: a configurational, situated, and dynamic approach,” in Organizational Hybridity: Perspectives, Processes, Promises, Research in the Sociology of Organizations; Vol. 69, eds. M. Besharov, and B. Mitzinneck (Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 3–25. doi: 10.1108/S0733-558X20200000069001

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., and Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 130, 165–218. doi: 10.1093/qje/qju032

Boell, S. K., and Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. (2014). A hermeneutic approach for conducting literature reviews and literature searches. Commun. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 34:12. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.03412

Charalampous, M., Grant, C. A., Tramontano, C., and Michailidis, E. (2019). Systematically reviewing remote e-workers' well-being at work: a multidimensional approach. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 28, 51–73. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2018.1541886

Choudhury, P., Crowston, K., Dahlander, L., Minervini, M. S., and Raghuram, S. (2020). GitLab: work where you want, when you want. J. Organ. Des. 9:23. doi: 10.1186/s41469-020-00087-8

Crawford, J. (2022). Working from home, telework, and psychological wellbeing? A systematic review. Sustainability 14:su141911874. doi: 10.3390/su141911874

Crummenerl, C., Perronet, C., Ravindranath, S., Paolini, S., Lamothe, I., Schastok, I., et al. (2020). The future of work: From remote to hybrid. Capgemini Research Institute. Available at: http://www.capgemini.com/researchinstitute/ (accessed July 18, 2023).

de Menezes, L. M., and Kelliher, C. (2011). Flexible working and performance: a systematic review of the evidence for a business case. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 13, 452–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00301.x

De Vincenzi, C., Pansini, M., Ferrara, B., and Buonomo, I. Benevene, P. (2022). Consequences of COVID-19 on employees in remote working: challenges, risks and opportunities an evidence-based literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:11672. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811672

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2012). “Self-determination theory,” in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, Vol. 1, eds. P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins (London: Sage), 416–437. doi: 10.4135/9781446249215.n21

Dingel, J. I., and Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 189:104235. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., and Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 133(C), 285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

ETUC UNICE/UEAPME, and CEEP. (2002). European framework agreement on telework. Available at: https://resourcecentre.etuc.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/Telework%202002_Framework%20Agreement%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed July 18, 2023).

Eurofound (2020). Telework and ICT-based mobile work: Flexible working in the digital age, New forms of employment series. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound (2023a). Hybrid work in Europe: Concept and practice. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound (2023b). Living and working in Europe 2022. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound and the International Labour Office (2017). Working anytime, anywhere: The effects on the world of work. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, and the International Labour Office, Geneva. Available at: http://eurofound.link/ef1658 (accessed July 18, 2023).

Ferrara, B., Pansini, M., De Vincenzi, C., Buonomo, I., and Benevene, P. (2022). Investigating the role of remote working on employees' performance and well-being: an evidence-based systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:1237. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912373

Gajendran, R. S., and Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 1524–1541. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524

Gajendran, R. S., Ponnapalli, A. R., Wang, C., and Javalagi, A. A. (2024). A dual pathway model of remote work intensity: a meta-analysis of its simultaneous positive and negative effects. Pers. Psychol. 1–36. doi: 10.1111/peps.12641

Gratton, L. (2021). How to do hybrid right? Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2021/05/how-to-do-hybrid-right (accessed September 1, 2024).

Hacker, W. (2021). Psychische Regulation von Arbeitstätigkeiten 4.0. Zürich: vdf Hochschulverlag AG. doi: 10.3218/4040-1

Hackney, A., Yung, M., Somasundram, K. G., Nowrouzi-Kia, B., Oakman, J., Yazdani, A., et al. (2022). Working in the digital economy: a systematic review of the impact of work from home arrangements on personal and organizational performance and productivity. PLoS ONE 17:e0274728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274728

Harker Martin, B., and MacDonnell, R. (2012). Is telework effective for organizations? A meta-analysis of empirical research on perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes. Manag. Res. Rev. 35, 602–616. doi: 10.1108/01409171211238820

Hatayama, M., Viollaz, M., and Winkler, H. (2020). Jobs' amenability to working from home: Evidence from skills surveys for 53 countries. Policy Research Working Paper No. 9241. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-9241

Hill, N. S., Axtell, C., Raghuram, S., and Nurmi, N. (2022). Unpacking virtual work's dual effects on employee well-being: an integrative review and future research agenda. J. Manage. 50, 752–792. doi: 10.1177/01492063221131535

ILO (2020a). Working from home: Estimating the worldwide potential, Policy Brief. Available at: wcms_743447.pdf (ilo.org) (accessed July 18, 2023).

ILO (2020b). COVID-19: Guidance for labour statistics data collection, 5/June/2020, ILO technical note. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—stat/documents/publication/wcms_741145.pdf (accessed July 18, 2023).