- AdventHealth Research Institute, AdventHealth, Orlando, FL, United States

Background: A psychoeducational group program for nurse leaders was developed based on the four themes of resilience, insight, self-compassion, and empowerment and involves therapeutic processing with a licensed mental health professional to alleviate burnout symptoms and protect wellbeing. The program was tested in a randomized controlled trial, which included a qualitative component to examine unit-based nurse leaders' perspectives of their job role and their experiences in the psychoeducational group program.

Methods: Online semi-structured interviews with 18 unit-based nurse leaders were conducted after completion of the program. Thematic analysis using the six-step process identified by Braun and Clarke resulted in the establishment of final themes.

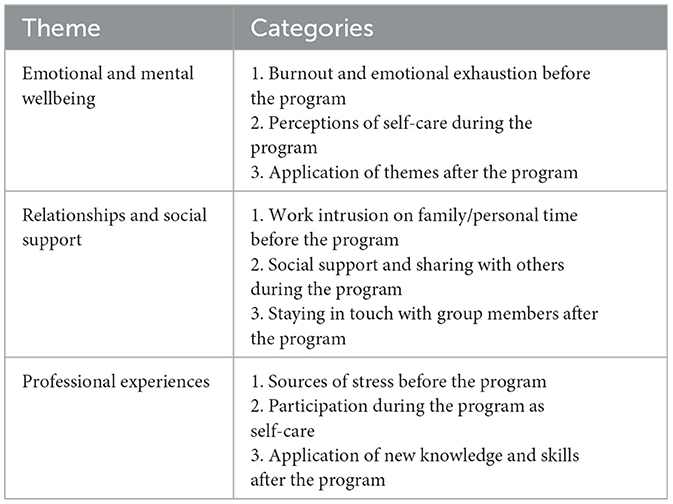

Results: Three primary themes emerged from the data analysis: emotional and mental wellbeing, relationships and social support, and professional experiences. There were nine sub-themes, which included temporal exploration of the themes before, during, and after the program as participants experienced transformation and growth. Findings illustrate that unit-based nurse leaders contend with many workplace stressors that impact their mental health. The psychoeducational group program enabled participants to prioritize self-care, contributed to participants feeling empowered to make positive changes in their work and home lives, and fostered a sense of connection and belonging. Participants also expressed a perceived improvement in their ability to be effective leaders.

Conclusions: These qualitative findings can help guide future implementation efforts of wellbeing programs for unit-based nurse leaders.

Introduction

Unit-based nurse leaders play a crucial role in patient outcomes, staff retention, and organizational culture (Choi et al., 2022; Hughes, 2019). However, the job often comes with many sources of stress, such as workload, low support, lack of resources, and staffing issues (Labrague, 2020; Membrive-Jiménez et al., 2020; Steege et al., 2017). A recent study of nurse managers indicates a rate of over 50% of those surveyed intend to leave their current position within 5 years (Warden et al., 2021). Work overload, insufficient resources, and lack of empowerment have been cited as factors contributing to unit-based nurse leader burnout and turnover intention (Hewko et al., 2015; Wong and Spence Laschinger, 2015). As unit-based nurse leaders are instrumental personnel in establishing quality nursing care and a professional practice environment (Warshawsky et al., 2022), it is imperative to identify interventions that support burnout prevention and recovery. While addressing burnout requires systemic changes in the work environment, individual-level interventions can be offered to healthcare workers to buffer against acute and chronic stress and prevent escalation to more severe stress injuries (Gray et al., 2019; Shanafelt et al., 2020).

One such individual-level intervention is a psychoeducational group program called RISE (Bailey et al., 2023). The program's title is an acronym for the four themes of resilience, insight, self-compassion, and empowerment. These themes are conceptualized as skill sets to mitigate burnout symptoms, improve coping behaviors, and nurture greater support (Bailey et al., 2023; Sawyer et al., 2022). Previous organizational efforts targeting nurse wellbeing and burnout prevention have primarily focused on resilience education (Joyce et al., 2018; Robertson et al., 2015). While education is crucial for prevention efforts, it may not be sufficient in addressing pre-existing stress injuries in nurses and nurse leaders. Designed to go beyond simply education, this program utilizes an integrative therapeutic approach grounded in acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 2006), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Beck, 1964, 1979), and mindfulness (Kabat-Zinn, 2003) to provide healing and recovery (Bailey et al., 2023). ACT, CBT, and mindfulness-based interventions have been documented as effective methods to improve psychological health and decrease stress reactions among healthcare workers (Barrett and Stewart, 2021; Gaupp et al., 2020; Prudenzi et al., 2022; Suleiman-Martos et al., 2020).

The RISE themes guide all learning and intervention activity. Resilience is included in the approach given the evidence supporting its positive effect on wellbeing and coping (Hart et al., 2014; Joyce et al., 2018). Insight is recognized as a significant vehicle of change, growth, and healing across a variety of theoretical approaches in counseling and psychotherapy (Bailey et al., 2023). Studies on self-compassion continue to show it may be protective against compassion fatigue and burnout (Raab, 2014). Importantly, self-compassion is a source of resilience and strength when facing adversity (Germer and Neff, 2013), and teaching self-compassion and self-care skills is an important feature in interventions that aim to reduce burnout and compassion fatigue (Duarte et al., 2016). Empowerment was included in the theoretical approach given the mental health and organizational benefits of feeling empowered, including organizational commitment, turnover intentions, innovation, wellbeing, and job satisfaction (Seibert et al., 2011; Spence Laschinger et al., 2014). Both structural and psychological empowerment are negatively correlated with burnout and psychological empowerment had a mediating effect on burnout (Meng et al., 2016).

The psychoeducational group program, led by a licensed mental health professional, involves weekly sessions that incorporate a variety of methods, including didactic education, therapeutic processing, self-reflection, skill development, and interpersonal learning. Psychoeducational groups have become a preferred and powerful modality for symptom reduction and personal growth in various settings (Corey et al., 2014; Yalom, 1995). The components of RISE were informed by group counseling theory, best practice standards, and legal and ethical requirements for group practice (American Counseling Association, 2014; American Group Counseling Association, 2007; Bailey et al., 2023; Corey et al., 2014; Thomas and Pender, 2008; Yalom and Leszcz, 2020).

The program was originally developed for direct care nurses in 2018 and subsequently tested in a pilot study and randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Sawyer et al., 2022). Results from these studies show the feasibility of the program and its effectiveness in improving wellbeing outcomes. Given the preliminary evidence and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was adapted for unit-based nurse leaders, specifically nurse managers and assistant nurse managers in 2021 (Bailey et al., 2023; Sawyer et al., 2021, 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic put an immense amount of stress and pressure on unit-based nurse leaders. Not only were they called upon to manage frequent and extreme changes, but they were also relied upon to support direct care nurses who were exposed to trauma and unprecedented loss (Bender et al., 2021; d'Ettorre et al., 2021). This part of their job role contributed to their distress as they attempted to manage their own grief and exhaustion (Lavoie-Tremblay et al., 2022; Udod et al., 2021; White, 2021). Importantly, the adaptation of RISE included the addition of post-traumatic growth and authentic leadership as theoretical underpinnings (Sawyer et al., 2022).

After completing focus groups and program adaptation, RISE for Nurse Leaders was tested in a pilot study (Sawyer et al., 2022) and subsequent RCT. Results showed feasibility and statistically significant improvements in post-traumatic growth, self-reflection and insight, self-compassion, psychological empowerment, and compassion satisfaction, as well as significant reductions in perceived stress, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress (Sawyer et al., 2023). The RCT with unit-based nurse leaders included a qualitative component, which involved semi-structured interviews with study participants who completed the program. The quantitative results have been previously published (Sawyer et al., 2023), so the aim of this article is to describe the qualitative study design and results of the thematic analysis.

Current study

The research question that guides this qualitative study is: how does learning and integrating the knowledge and skills associated with the constructs of the RISE program (resilience, insight, self-compassion, and empowerment) influence the personal resources necessary to mitigate and prevent occupational burnout in unit-based nurse leaders?

Theoretical model

This study was informed by the Jobs Demands-Resources model (Demerouti et al., 2001). This model posits that excessive demands, whether physical, social, or organizational, contribute to exhaustion, whereas the provision of resources, both internal and external, bolsters wellbeing and organizational commitment (Demerouti et al., 2001). Both increased demands and poor provision of or access to resources contributes to burnout (Schaufeli, 2017). Improving personal or internal resources—accessing existing strengths and characteristics while teaching how to leverage newly acquired coping skills and knowledge—can help mitigate the effects of burnout and contribute to job motivation (Demerouti et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2016). The concepts inherent in the RISE program and strategies, such as mindfulness and peer support, are integral to the changes precipitated by increasing awareness of and access to increased personal resources (Bailey et al., 2023; Bakker et al., 2004; Grover et al., 2017; Tremblay and Messervey, 2011).

Methods

Study design

This qualitative study utilized voluntary video-conferencing interviews with participants who attended the program. Braun and Clarke's guidance on conduct of thematic analysis directed data management and interpretation, including the six-step process of familiarization with data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Participants

As previously described (Sawyer et al., 2023), the inclusion criteria for participants in the RCT were: adult ≥18 years old; licensed as a registered nurse (RN); nurse manager (NM) or assistant nurse manager (ANM) employed by the healthcare organization in a hospital-based setting at selected campuses in Florida; and able to speak, read, and understand English fluently. The exclusion criterion in this study was employment as a direct care nurse or in another level of nursing leadership (i.e., director of nursing, executive leader). In the initial study invitation and consent document, participants were informed of the opportunity to participate in a post-program 1:1 interview to reflect on their experiences in the program. After the completion of the psychoeducational group program for both intervention and waitlist control groups, participants were invited via email. All participants who completed the program were eligible to participate in the interviews. Interested participants were self-selected into a convenience sample. Because participation in the interviews was a voluntary component of study activities, no data regarding reasons electing not to participate were collected. If after the analysis phase data were not saturated, follow-up invitations via email to participate in interviews would have been sent.

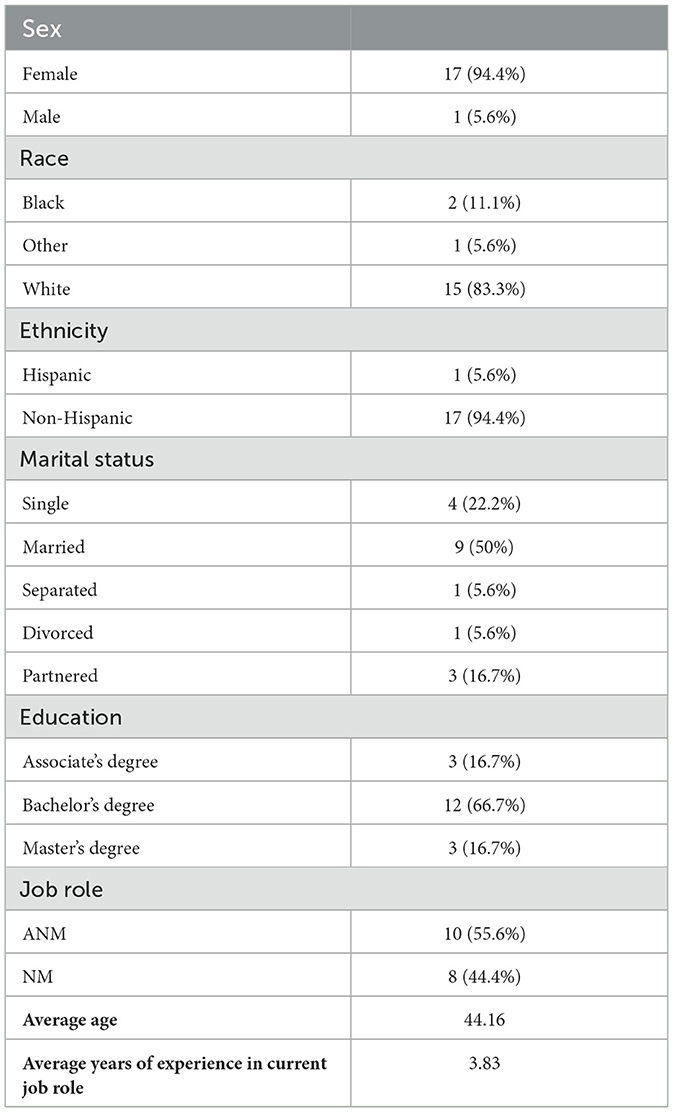

A total of 18 participants completed an interview. Table 1 shows the participants' demographic characteristics.

Setting

The RCT (Sawyer et al., 2023) was conducted at a multistate healthcare system headquartered in Florida. The Microsoft Teams interviews occurred in July 2022 for the intervention group, which attended the program in March through May 2022, and December 2022 for the wait-list control group, which attended the program in September through November 2022. The wait-list control group attended the program 3 months after the intervention group to allow for between-group comparisons in the quantitative outcomes. As the interviews took place through videoconferencing, individuals could opt to participate from their work office or from their home on a day off work. Most participants elected to conduct the interview while they were at work.

Data collection

A master's-level bio-behavioral researcher (SLH), who is trained and experienced in interview facilitation, led the scheduled 60-minute interviews. She had no relationship with the participants before the interviews. Due to the established relationship with participants through program delivery and to avoid any possible assumptions and biases that could influence the results, the study team member who developed and delivered the intervention (AKB) was not involved in the interviews.

All participants were given options of time blocks from which to schedule their interviews. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewer introduced herself as a member of the study team, explained the purpose of the interview, and informed the participant that the interview would be recorded and transcribed. A semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary material 1) was utilized to ask participants about their roles as unit-based nurse leaders, their experiences in the psychoeducational group program, definitions and facilitators of wellbeing and self-care, personal and professional impacts of the pandemic, and opportunities for program improvement. The interviews were conducted, recorded, and transcribed on Microsoft Teams. The transcriptions were manually checked for accuracy and corrected by members of the study team and then reviewed in tandem with the recorded interviews during data analysis for further refinement. Interview duration ranged from 23 to 60 minutes, with an average of 38 minutes.

Ideally, qualitative sample sizes range from 3 to 35 subjects (Guest et al., 2006) and data collection should continue until saturation is achieved. In samples with similar characteristics (i.e., job descriptions), typically 9–17 interviews is adequate (Hennink et al., 2017). Although formal analysis did not take place until after completion of all of the interviews, it was evident that saturation had been achieved. Regardless, all participants who volunteered their time would have been given the opportunity to engage in interviews and share opinions on the program as a courtesy.

Data analysis

The study's principal investigator (AS) used Braun and Clarke's model of thematic analysis to code responses, which were then aggregated into six themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Familiarization with data involved detailed review of transcripts and recorded interviews. Themes emerged through thoughtful review of transcripts and codes, guided by the four step process of initialization, construction, rectification, and finalization described by Vaismoradi et al. (2016). After initial coding was completed, the interviewer (SH) compared established codes and themes to original transcripts. Collaborative analysis of data resulted in minor changes to original coding, but themes remained consistent. Through this process, significance of themes was established through a collaborative approach.

Following best practices to ensure rigor in data collection and analysis, techniques to establish credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability were undertaken (Creswell and Miller, 2000; Lincoln and Guba, 1985). The interviewer engaged in a reflexivity narrative before beginning study activities and acknowledged potential biases toward effectiveness of the program and noted the need to avoid prompting for positive experiences (Olmos-Vega et al., 2023). Peer debriefing took place throughout the data collection process within the study team, with the intervention facilitator as a subject matter expert, and with another qualitative researcher (Creswell and Miller, 2000). Ad hoc, online meetings between the interviewer and intervention facilitator took place to seek additional context when program activities were discussed. Triangulation from published literature, previous studies (Sawyer et al., 2022), and ongoing data collection informed the interview process and data analysis, as participants were asked to corroborate, expand on, or disagree with statements previous interviewees offered. An audit trail, including process notes and data synthesis, was maintained (Wolf, 2003). Overall, data structuring and integration were completed collaboratively through a process of theme identification and revision. The developer and study interventionist (AKB) was not involved in the thematic analysis to eliminate potential for bias given familiarity with the programming and participants.

The process of identifying emerging themes involved categorizing and recategorizing codes within the context of the theoretical model and review of original transcripts. During this process, a temporal pattern of codes emerged that reflected change processes for participants. For example, regarding the work experience, emotional and mental wellbeing emerged as a code. Symptoms of burnout like depersonalization (e.g., “it's hard to have empathy”) and emotional exhaustion (e.g., “there's a lot of emotional toll”) evolved into descriptions of balance (e.g., “slow down and enjoy life”) and empowerment (e.g., “I can make it through it”). The process of coping skills acquisition and development (i.e., additional psychological resources) facilitated a shift in the balance between job demands and resources (Demerouti et al., 2001). The original themes that were more granular and conceptualized negative mental health (e.g., burnout and distress) and positive mental health (e.g., balance and empowerment) were combined into one theme to capture the continuum of mental and emotional health experiences. Similarly, the theme of professional experiences arose from examination of numerous codes that reflected stress and distress that transformed into action and application of coping skills. Codes that described overwhelming stress at work and understaffing contrasted post-program codes that embodied sharing of learned lessons and enacting mindfulness at work. These professional experiences reflect the newly leveraged internal resources that can help mitigate the environmental demands of the workplace and change perceptions of the availability and scope of personal resources (Demerouti et al., 2001; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

Ethical considerations

The study received approval from the institutional review board (IRBNet #1839775) as a qualitative component of the RCT registered as NCT05254600 on ClinicalTrials.gov. Before engaging in any study-related tasks, participants provided informed consent. The informed consent document was distributed electronically, and a study coordinator and the principal investigator were available to respond to any questions or concerns from potential participants. A study coordinator met with each potential participant through video conferencing to read and review the entire consent document, and then, electronic signatures were obtained. Electronic copies of the signed consent form were emailed to the participants. This study adhered to ethical principles including autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice, and it met the research obligations pertaining to consent, confidentiality, and safety. The study team upheld participant privacy during participation and data gathering, provided participants with comprehensive details about the study verbally and in writing, and made it clear that they would be able to withdraw from the study at any point without the need for justification.

Results

Table 2 shows the following three themes that emerged most consistently: (1) emotional and mental wellbeing, (2) relationships and social support, and (3) professional experiences. Each theme is described below along with sub-categories and participants' statements to illustrate their perceptions before, during, and after the intervention.

Theme 1: emotional and mental wellbeing

Burnout and emotional exhaustion before the program

Participants shared that they were experiencing burnout, including emotional exhaustion, before they attended the program. High job demands that exceed resources can be predictive of decreased job satisfaction, distress, and burnout (Adriaenssens et al., 2017; Barello et al., 2021).

I was exhausted mentally, physically, emotionally. I could sleep all day when I get off work and all night the next night and take a nap the next day, too. I was like, okay, I need to regain some balance and some of me. I love being a nurse. I love taking care of patients and helping them, but at some point, I matter.

-Participant 17

Nurse leaders described feeling burdened with the requirements of achieving specific metrics, rounding for patient satisfaction, completing administrative tasks for personnel management, and maintaining an open-door policy with direct reports.

I was consumed. I took my computer home all week and all weekend. I sat in front of my computer. Because I couldn't get things done during the week, so I would try to get them done at home because “patient experience, patient experience, patient experience,” rounding on 30 patients, and then the accountability. Did you get this done? Did you get that done? It was so much.

-Participant 3

Many participants expressed that being accountable for the unit 24 hours a day, 7 days a week had detrimental effects on their wellbeing. Technology can exacerbate the feelings of exhaustion associated with 24/7 accountability as email and text messages encroach on time away from work (Steege et al., 2017).

There is a lot of pressure and stress. I mean, the demands are 24 h a day. They text you all the time. They text you on the weekend, you know, 11:00 at night. They are still texting.

-Participant 3

Perceptions of self-care during the program

Participants reported learning the importance of self-awareness and self-care in the program and practicing skills related to both concepts. Although there was knowledge about the importance of these practices, nearly all participants acknowledged that they were undermined by their work-related responsibilities. Nearly 70% of nurses surveyed in the United States reported putting work responsibilities before their own needs (American Nurses Association, 2017).

It is hard because caregivers feel like we have to take care of everybody else and somehow taking care of ourselves takes away from that… One of the things that I was talking to another manager about was how we always say, “You have to put your own oxygen mask on first.” That's a little reminder that when you take care of yourself, you take better care of other people.

-Participant 15

Before the program, several participants felt that self-care was tantamount to selfishness. Although professional nursing organizations and nursing theoretical frameworks describe self-care as an ethical imperative (Linton and Koonmen, 2020), those in caring professions often need education and support to learn to prioritize themselves.

Think of it like a pyramid. If I am on the bottom of the structure, and I am not strong enough, then everything I have built will crumble. I have to know that self-care is not selfishness. That's something that [the program] taught me because I always kind of felt selfish about it.

-Participant 9

Through their participation in the program, nurse leaders expressed an understanding of the association between self-awareness and self-care. Conceptually, awareness is a predominant attribute of self-care in nursing, and when paired with knowledge and skills, awareness precipitates empowerment to care for oneself (Martínez et al., 2021).

Self-care means to be aware of my own feelings and pay attention to and not ignore them. It is like when you have a car, and you hear a sound that doesn't sound right. Then, what do you do? You take it right away to the mechanic. But what do we do if I am feeling tired? You don't rest, right? And you are supposed to.

-Participant 4

Participants noted the usefulness of program resources like the feelings chart, which is a comprehensive list of emotions that helped them name their emotional experiences. They shared how they learned that self-care activities, including emotion identification, are integral to the stress recovery process. These practices widely vary between individuals, ranging from manicures to spending time with grandchildren to emotional expression.

Application of themes after the program

The four program themes—resilience, insight, self-compassion, and empowerment—resonated with participants as they were able to enact the concepts and skills rooted in the program. In therapeutic settings, the application of learned skills supports better outcomes (Hoet et al., 2018). Nurse leaders reported practical applications of the program constructs, both in personal and professional settings.

Reframing and owning the word “resilience” in light of its overuse during the COVID-19 pandemic was meaningful to nurse leaders. The words “resilient” and “hero” led to resentment among many nurses during the pandemic because they were put at personal risk while working under tremendous emotional strain with ever-increasing demands.

Don't tell me I am resilient because I was not resilient. I just got knocked down, and I got back up. And then, I got knocked down even harder and was told I was not doing what I needed to do and needed to fix it… I think they took a word [resilience], and they turned it [into] manipulative nastiness. If that's what resilience is, I never want to be resilient ever again in my life.

-Participant 11

Instead, resilience was introduced in the program as the ability to harness both internal and external resources to support oneself through hardships and recovery. Resilience in nursing is defined as a “complex and dynamic process” (Cooper et al., 2020, p. 567). The message that resilience can be cultivated and nurtured was appreciated by nurse leaders.

I have learned that I am more resilient than what I thought I was. I thought I was just this person that just gives up. But in reality, every day I go and try again, it is every day that I am more resilient than before. It is every day that I have a new strength that I didn't know and can unlock about myself.

-Participant 7

Insight was demonstrated among participants as both self-awareness and extending more understanding to others in the workplace. For nurse leaders, insight often encompassed placing emotions and coping strategies in context. This new insight contributed to an observed increase in emotional intelligence, which has been associated with more empowerment and improved leadership (Akerjordet and Severinsson, 2008).

[The program] has made me more aware. I probably never thought about how I dealt with things. I just like to put things in a little box and put it to the side… We box [emotions] up. We put it to the side, and if I have time, I will get back to that. If not, then as long as it is not affecting what I am doing right now, I am good with it, and I am just aware of that now. I think I have always done it, but I just feel like I am definitely aware of it to where now sometimes I'm like, okay, I guess I should pull that box out and deal with all this. And, you know, empty one of the boxes in the attic.

-Participant 2

The concept of self-compassion impacted many nurse leaders who balance weighty expectations from leadership and direct reports with their own perfectionism. Despite readily extending compassion to others, nurses often need permission to extend compassion to themselves (Andrews et al., 2020). The program afforded this permission and emphasized the need for self-compassion when faced with unrealistic expectations.

Probably was the biggest thing to give myself grace, to give myself forgiveness, because I am my worst critic… I see a bunch of people that do half the work that I do, and I still do not think I am doing enough. But if I can't get it done, then they probably need to hire somebody else to support me…probably three people if I am not here. That probably was the biggest thing—to know that I am enough.

-Participant 11

Empowerment is associated with job satisfaction in frontline nurse managers (Penconek et al., 2021). On the other hand, feeling disempowered can cause antipathy and frustration. Some nurse leaders noted that tasks over which they had no influence, such as mandatory patient satisfaction rounds, detracted from their sense of empowerment. Conversely, taking action in meaningful ways was reinforced in the program, such as setting and enforcing work-life boundaries, and provided a new sense of empowerment.

I had not taken a single day off in 2 years…During [the program], I took a week and a half of vacation for the first time ever.

-Participant 6

In addition to the four program themes, participants adopted several skills, techniques, and strategies introduced in the program to cope with stressors and reframe challenges. Chief among these was mindfulness-based deep breathing exercises. The appealing aspects of this practice include great rewards for minimal time commitment. Breathing-based interventions, as part of broader educational or therapeutic programs, have been shown to reduce anxiety in healthcare providers (Melnyk et al., 2020). Deep breathing can be practiced at work inconspicuously and can facilitate an emotional reset.

To take those 5 or 10 min a day for you and breathe, you know, just really focus. If you feel like something is going on during the day, or you start to get anxious, you are allowed to go shut it off and just breathe for a few minutes and refocus… I feel like it has almost made me a calmer person.

-Participant 2

For many participants, the program allowed engaging in a level of introspection and quality of life assessment that they had not previously explored. Turning attention inward instead of outward was enlightening and prompted some participants to continue their self-improvement by seeking additional support.

Honestly, until [the program], I really never thought about boundaries. I never thought about self-care. It was never something I even thought of. It was [the program] that got me thinking, “Hey, I probably should consider these things.” On my last day of [the program], I made an appointment with a therapist. I'm working on getting the help I need to help me set boundaries.

-Participant 6

Theme 2: relationships and social support

Work intrusion on family/personal time before the program

Participants emphasized that they felt the need to be available 24/7 even when they were not scheduled to be working. It was common for them to perceive a role expectation to always respond to emails, phone calls, and text messages, which detracts from their quality of life and intrudes on family and personal time. Previous research on the role of unit-based nurse leaders aligns with this theme. Work-life conflict is a predictor of turnover intent, while satisfaction with work-life balance is negatively associated with burnout (Kelly et al., 2019; Labrague, 2020).

It is the planned things that happen on off-hours that are really frustrating to me. I am scheduled to work 8:00 to 5:00. Every single day. But it is those things that are at 7:00 at night, we will have this call, or on Saturday, we will have this call at 10:00… I know the job is 24 h. I know that it is. If it is something that comes up, I want to work on it. I want to fix it. Right then and there. But there is too much, way too much.

-Participant 6

Related to the never-ending work cycle, participants identified a lack of boundaries that affected their personal and professional lives. The emotional turmoil of job-related pressures does not remain within the walls of the hospital and can impact the families of nurse leaders who see their loved ones suffering.

It was so much, and my husband and I sat down because my kids had been like, “Mom, you come home and cry every day… you're so sad all the time.” My husband said, “Okay, you have to make a decision.” He said, “I know that you love your team and that you love your unit…but you're losing yourself and we're losing you.”

-Participant 3

Social support and sharing with others during the program

Participants felt that they benefited from social support received by other program participants. The weekly groups were divided by job role of ANM or NM. Oftentimes, group members worked at different hospital campuses and did not know each other before the program start. Generally, they felt open when talking to the other group members after the initial introduction and seemed to appreciate the sense of confidentiality afforded by mixing with leaders from different campuses than their own.

I was super happy that it was like none of us knew each other because that would make it harder, more difficult to share if you knew all these people. So, I thought that was definitely a cool concept, how it was set up that even though we were all [from the same organization] but we were [from] different facilities.

-Participant 2

Therapeutic group participants often feel unsure and hesitant about personal disclosure when first starting the group (Brown, 2018; Corey et al., 2014; Yalom and Leszcz, 2020). As the group develops cohesion and builds trust, members take more risks related to self-disclosure and vulnerability (i.e., emotional honesty, authentic responding) (Brown, 2018; Corey et al., 2014; Yalom and Leszcz, 2020). Vulnerability is difficult in a profession that expects emotional fortitude, but the validation of feelings and a psychologically safe environment cultivate connection and sharing. Activities built into the curriculum, such as directed self-reflection, group discussion, and sharing in dyads, are intended to foster this environment and encourage deeper self-disclosure, vulnerability, and catharsis.

I think for the most part there were some of us a little bit more reserved at the beginning, but by midway, they started being a little bit more open. There were tears. I think every one of us cried during the sessions… I think it was a good group. A good, perfect mixture of different service lines and backgrounds because we can all relate to each other. And I do think it helps just to know that someone else was going through the same thing.

-Participant 8

The social support from others in similar work roles was encouraging, because as one participant noted, frontline nurse leaders often work in silos. Particularly those promoted to management positions after being direct care nurses may experience a sense of isolation. Feeling caught between the demands of management and direct reports can create feelings of loneliness and a need for a sense of belonging (Solbakken et al., 2022). Feeling less alone, validated, and heard by others in a non-judgmental setting afforded tremendous benefits.

Just hearing that the common experiences, the common frustrations…it was definitely therapeutic. It was nice to just have people to listen to and you know how they have dealt with some of these things, … listening, learning, and just that camaraderie was definitely very nice.

-Participant 16

Staying in touch with group members after the program

Efforts to maintain relationships with other group members after the conclusion of the program sessions varied. Some participants felt the experience was finite, and the benefits of peer social support during the sessions themselves were adequate. Others made more lasting connections.

I gained a good support group. We have a chat started with the people from [the program], so that's nice. If anybody is having a bad day, we can reach out and stay in touch a little, especially on the hard days and just share.

-Participant 14

As the duration of the 9-week intervention was relatively brief, the individual groups varied in the pace of their comfort with disclosure and establishment of trust. It can take time for a support group to establish an identity, and the education literature determined that group cohesion is an emergent process in an online small group setting (Reschke et al., 2021; Zamecnik et al., 2022). It is likely a matter of individual preferences and group dynamics that influenced the decision to maintain social contact after the conclusion of group sessions.

Theme 3: professional experiences

Sources of stress before the program

The numerous sources of job-related stressors in frontline nurse leaders include role complexity, staffing and resources, high expectations, and volume of work (Labrague et al., 2018; Shirey et al., 2010). Existing stressors among participants were exacerbated by the pandemic, which frequently put further strain on staffing and created interpersonal tensions.

A substantial collection of literature describes the stress of the pandemic and how it affected healthcare workers, including the mental, physical, social, spiritual, and professional ramifications (de Pablo et al., 2020; Mercado et al., 2022; Smallwood et al., 2022). The stress of the pandemic impacted nurse leaders as they encountered new responsibilities and pressures, such as distributing scarce personal protective equipment (PPE), dealing with fear of contagion among staff, and managing uncertainty due to mixed and sometimes conflicting messages from leadership (Aydogdu, 2023; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022; White, 2021). Unit-based nurse leaders often suffered themselves as they witnessed unprecedented death and felt tremendous empathy for their direct reports, particularly nurses who were new to the profession.

When Delta was here, we had almost a month, if not 2 months, where nobody left the ICU alive. And it was such a huge burden on everybody. Because they were young, they were old, they were healthy, they were sick. Anybody and everybody. So, we were so afraid for ourselves, for our loved ones. And we felt like we were losing hope. Nothing we can do is going to save them.

-Participant 15

Some participants explained that the pandemic was an opportunity for them to get back to direct care and be involved in clinical work. They expressed the importance of “jumping back in” and feeling like they could make an impact and add meaning and purpose to their work during a time of chaos and disruption to normal operations.

I got back to the clinical a little bit because it was all hands on deck. So, I was able to get in, get my hands dirty, just really help and be clinically on the unit, which was great. I was able to step back a little bit from the administrative. The meetings went away…

-Participant 16

Not only did the pandemic affect nurse leaders, but so did the process of returning to normal. Some participants began their job role during the pandemic, so that was “normal” for them. The “return to normal” involved learning new processes and a sudden reemergence of things to do that created more work.

When we talk about getting back to normal, it is not just like you flip on a switch, and we are back to normal. We have to relearn everything, and the staff have to relearn everything. And we have to start from the very bottom. It is frustrating because before COVID-19, we performed at a 10. Now, we're performing at a three at best.

-Participant 10

In addition, the widespread respect and appreciation of nurses during the pandemic began to fade into “business as usual,” and some of the abuses and indignities that nurses faced before the pandemic began to reemerge and worsen.

During COVID-19, nurses were superheroes, right? They had pictures of us all over the place… But now, we are back to patients who are yelling at us, and patients who are throwing things at us, and literally patients are hitting us. I mean, nurses get hit all the time… So, I think that is really damaging to the psyche of a nurse.

-Participant 10

Nursing staff turnover has increased substantially since pre-pandemic levels and reports indicate a nursing vacancy rate of 15.7% (NSI Nursing Solutions, 2023). Increased nurse-patient ratios, inexperienced staff, and mental health of staff are all concerns of unit-based nurse leaders (Baudoin et al., 2022; Lasater et al., 2021; Vázquez-Calatayud et al., 2022). Participant responses aligned with these concerns as they navigated staffing challenges, mentoring, and safety. They reported that their new nurses were unprepared without hands-on clinical practice during the pandemic, while their experienced nurses were overburdened and resentful of the pay rates of traveling and contracted nurses.

With all the new hires, I absolutely hate giving them five and six patients. Some of them have been out of orientation 1 or 2 weeks, and it is just not fair to them. They have a ton of questions, which I would much rather them ask questions than to mess up, but it takes so much time for me because everybody and their brother comes to me. And I'm like, okay, at some point I need to do my work.

-Participant 17

Furthermore, several frontline nurse leaders disclosed interpersonal conflict at work, involving peers, fellow leaders, and direct reports. Scheduling issues, personality clashes, and perceptions of lack of teamwork all contributed to these conflicts. Interpersonal conflict is associated with nurse manager job stress (Kath et al., 2013), and perceptions of unfair treatment and irresponsible behavior by others can lead to resentment among nurses (Wright et al., 2014). Although bullying in nursing is well-documented, research about upward bullying is emerging (Gaudine et al., 2019). Incivility between ANMs and NMs contributed to job-related stress to the point where some participants expressed a desire to transfer to another department to avoid further conflict.

It is really hard working with somebody who just absolutely refuses to work with you.

-Participant 1

Participation during the program as self-care

Self-care is increasingly identified as an imperative for personal and professional development among nurses and nurse leaders (Green et al., 2023; Ogilvie et al., 2021). Participants considered making the time to engage in nine 90-minute weekly sessions to be a sacrifice of valuable work time. During this time, they were asked to close their doors and ignore their phone calls and emails. However, many viewed enrolling in the program as a first step in terms of investing in their self-care and practicing boundary setting.

I was put into this group during this super busy time and learned that as busy as you are, you should always take time for yourself, and that was something that I did. I gave [the program] that time and that learning to myself. I really appreciated that there were people going through the same thing I was, and we were talking about it, and I learned from [them] during very busy hours of my life, a very busy time of my life. I took it for me, and I was proud of myself for doing it.

-Participant 5

Application of new knowledge and skills after the program

As unit-based nurse leaders, participants had the opportunity not only to internalize the knowledge and skills learned in the program, but to “pay it forward”—both in sharing strategies with direct reports and by becoming more mindful leaders. Mindfulness in nurse leaders can facilitate reduced perceptions of demand-related stress in their nurses, and being a present, compassionate leader helps to build bonds of trust with staff (Liu et al., 2021; Papadopoulos et al., 2021). Participants reported integrating practices like breathing exercises and mindfulness moments into team huddles, and their own self-awareness and insight helped them recognize signs of stress in their staff.

I think the biggest thing is that I can identify when someone is in a tizzy, for lack of a better word. I do not take it on myself, which I would have before, and I wanted to fix it, but I identify it and try to help them identify it. I wish someone before would have said to me, “You're not alone, and this sucks, and this is not you.”

-Participant 11

Some participants experienced substantive improvements in personal outlook based on increased personal insight, feelings of empowerment to make change, and newly enacted self-care and coping strategies. As a result, they became more caring leaders and intended to continue their growth and professional development with these factors in mind.

[Mid-program] I changed who I was, and it was dramatic. I realized how much a “thank you” means and how if my cup is not full, I cannot ever fill everybody's cup… By filling my cup and working on myself, I have noticed such a huge increase in my team's demeanor… They all knew that I was doing it because I am like, “I cannot take care of you all if I cannot take care of myself, I am working on me.” They all were very supportive of it.

-Participant 11

Discussion

This study offered insight into unit-based nurse leaders' perspectives of their job role and their experiences in a psychoeducational group program that provided them with knowledge and skills to help mitigate the impact of burnout. Specifically, the findings categorized into three main themes provide accounts of these experiences related to their (1) emotional and mental wellbeing, (2) relationships and social support, and (3) professional experiences before, during, and after the psychoeducational group intervention. Findings provide further support for the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of the evidence-based intervention as a means to bolster personal resources to counter the pressing job demands of unit-based nurse leaders (Adriaenssens et al., 2017; Sawyer et al., 2022).

The first theme highlights a known dimension of nursing management, which is that it is a profession that impacts emotional and mental wellbeing. Though limited, existing literature on the effects of work in nursing management align with our findings. Role overload has been identified as the principle contributor to workplace stress for nurse managers, which has negative implications for mental health (Kath et al., 2013; Labrague et al., 2018; Membrive-Jiménez et al., 2020; Steege et al., 2017). In a recent survey, 75% of nurse managers reported that stress from work had a negative impact on personal life (Martin et al., 2023). When work-related stress is cumulative and chronic, it may lead to compassion fatigue and burnout, decrease work-related quality of life, and increase intent to leave (Hewko et al., 2015; Warshawsky and Havens, 2014). This emerged as a sub-theme, as the analysis revealed that participants experienced burnout and exhaustion before the psychoeducational group program.

However, strategies emerged among study participants for coping and recovering from these stressors. Prioritization of self-care was identified as key to balancing the demands of work and home for individuals who often act as caretakers in both settings. While some previous research has focused on basic wellness behaviors (e.g., nutrition, sleep, and physical activity) as manifestations of self-care for nurses (Couser and Cutshall, 2020; Ross et al., 2019), other studies have considered more holistic approaches that incorporate mindfulness, journaling, and guided imagery (Blackburn et al., 2020). The program maintains an individualized, integrated approach wherein self-care may include any or all of these elements as determined by each participant's needs and preferences. The program guides participants to cultivate awareness to identify their personal needs and how to attend to them.

Findings suggest that participation in the program can lead to positive mental wellbeing outcomes. Thematic analysis of the interviews revealed that participation in the program facilitates insight and self-awareness, interpersonal connection through social support, and skill development, which are target aims of the intervention (Sawyer et al., 2023). Greater self-awareness amidst complex job demands contributes to perceptions of competence and job efficacy among nurse managers (Younas et al., 2021).

Insight-oriented activities related to program themes (resilience, insight, self-compassion, and empowerment) guided the participants to identify and leverage personal resources that may mitigate the ostensibly controllable aspects of burnout. As both burnout and job satisfaction are contingent on a variety of personal and environmental factors (Lee and Cummings, 2008; Penconek et al., 2021; Spence Laschinger and Finegan, 2008), the program focused on harnessing individual strengths and resources, authentic living, mindfulness, and reappraisal of one's relationship with work through self-compassion and values alignment, which contributes to greater emotional and mental wellbeing.

Additionally, the qualitative findings indicate that empowerment among participants manifested as the ability to establish and enforce boundaries that included more work-life balance and time for self-care. The interviews provided this collective view that informs the interpretation of the quantitative finding of improved empowerment over all study time points (Sawyer et al., 2023). Although participants did not specifically label their experiences using the term of empowerment, they widely acknowledged taking empowering actions. The program was designed to lead to incremental change and benefit over time as skills build upon themselves. Over the 9 weeks, participants gained more comfort with self-evaluation, allowing them to take more thoughtful, informed action in their daily lives, which contributes to confidence and competence (i.e., empowerment). Through emotion regulation, cognitive reappraisal, and values-directed behavior, participants felt more agency related to boundary-setting, interpersonal effectiveness, and adaptive coping. Participants described greater self-determination related to caring for themselves and making choices that are good for their mental wellbeing. Improving one's perception of choice and self-agency can encourage positive change behaviors (Hugh-Jones et al., 2018). The belief that they are competent and have an impact in their work led to empowerment among participants as shown in the scores on the Psychological Empowerment Instrument (Sawyer et al., 2023; Spreitzer, 1995).

A second theme emerged from the analysis of qualitative data: relationships and social support. Interpersonal dynamics come up frequently in relation to work as a nurse leader. The sub-theme of intrusion of work on family time is consistent with literature on nurse manager experiences in their role (Brown et al., 2013). The blurred boundaries between work and home life can contribute to experiences of burnout. Additionally, common symptoms of burnout are exhaustion and irritability, which often interfere in quality connections with personal relationships (Tone Innstrand et al., 2008).

Conversely, personal and professional social connections are integral to nurse leader wellbeing (Cziraki et al., 2014; Kath et al., 2012; Penconek et al., 2021; White, 2021). Nurse managers have identified peer support groups as vital structures that help with networking, perspective-taking, learning, catharsis, and problem-solving (Kramer et al., 2007; Sawyer et al., 2022). Study participants reported that connecting to peers through the group intervention led to feeling less alone, validated, and heard by others in a non-judgmental setting, which benefitted their mental wellbeing. Other peer-support models have been explored in the literature and corroborate these findings. Peterson et al. (2008) reported improvements in burnout and other mental health conditions from peer support groups among healthcare workers. Those who engaged in peer support groups also reported some behavioral changes that supported balance and self-care, including writing down goals and saying “no” more often (Peterson et al., 2008).

The social cohesion formed within this program's groups facilitated normalization and validation of experiences, encouragement for self-reflection, and reassurance during times of vulnerability. Creating a space for peers to explore shared experiences has shown positive effects on wellbeing, and active relational coping has been associated with post-traumatic growth, which is consistent with this study's quantitative finding (Sawyer et al., 2023) of higher post-traumatic growth reported after the program (Rajandram et al., 2011; Sawyer et al., 2023; Shalev et al., 2022). Healthcare organizations have invested resources (e.g., personnel, salary, and education time) into building peer support programs, as they have demonstrated positive impact on compassion satisfaction and burnout (Lowe et al., 2020; Wahl et al., 2018).

Lastly, the maintenance of group member relationships beyond the program varied, and it is likely a matter of individual preference and group dynamics that influenced the decision to maintain social contact after the conclusion of group sessions. The choice and autonomy to keep in touch with fellow group members likely empowered participants to do what is best for them according to personal needs and boundaries.

The third theme that emerged from the analysis was related to professional experiences before, during, and after the psychoeducational group intervention. Results identify sub-themes which describe experiences temporally as participants moved through the program: Sources of Stress Before the Program, Participation During the Program as Self-Care, Application of New Knowledge, and Skills After the Program. Participants articulated the transformation of their professional experiences through program participation and skill development.

The COVID-19 pandemic, staffing, and interpersonal relationships were noted as key drivers of stress by the study participants. Extant research supports these identified factors as detractors from overall wellbeing and job-related satisfaction. Studies of unit-based nurse leader experiences during COVID-19 revealed significant mental and physical consequences, including anxiety and isolation (White, 2021). In addition, a cross-sectional study to identify sources of stress and satisfaction in nurse managers found that adequate staffing and resources were significantly associated with satisfaction whereas conflict with other nurses was a stressor (Jäppinen et al., 2022).

The act of taking time for program participation was identified as self-care by many of the nurses, and prioritization of time for taking care of oneself was a prominent “takeaway.” Other mindfulness and resiliency-based interventions for nurses result in actualized and/or renewed focus on self-care. Nurses have reported alleviation of guilt associated with taking time for self-care and redirecting energies inward (Slatyer et al., 2018). A recent study identified “the need for permission” from themselves and others as key in enabling nurses to practice self-care and self-compassion (Andrews et al., 2020).

Studies of interventions with nurse managers to learn skills related to self-care and mindfulness demonstrate that there is sustainability to these programs and skills learned are applied in the workplace. For example, in one study of nurse managers, mindfulness was associated with positive and constructive conflict resolution styles (Assi et al., 2022). Additionally, Shurab et al. (2024) reported that skills and practices like mindfulness, when taught in an intervention, improve over time and are sustained post-program.

Virtual attendance

Critical to the success of the program were attendance and active participation. The pandemic necessitated the transition of instruction and care to web-based conferencing delivery (Khurshid et al., 2020). Although many participants expressed interest in in-person meetings, the virtual delivery allowed participants from multiple campuses to attend conveniently. Furthermore, as evidence of cohesion and positive group dynamics, participants reported feeling connected to and supported by each other in this online format, which is consistent with other studies involving online interventions (Karagiozi et al., 2022; Lenferink et al., 2020). This study adds to empirical support for effective virtual delivery of mental health programming.

Limitations

As a limitation, this qualitative component of the study gathered the experiences of unit-based nurse leaders who self-selected into participating in this research related to wellbeing in a specific hospital setting. Though the intention was to provide deeper insight into participants' experiences rather than generalize the findings, they pertain to the context in which the study took place and the perceptions of a limited number of individuals within the population. Some participants engaged in interviews at work during a shift and encountered interruptions that may have influenced responses and focus. In addition, although the interviewer made efforts to avoid bias in presentation of questions to participants, it is possible that anticipation of favorable responses may have influenced the tone of conversation.

Conclusions

This study provides an understanding of unit-based nurse leaders' experiences with a program developed to improve wellbeing and reduce burnout. In support of the mechanisms for change and intervention effectiveness, it demonstrated how a virtual psychoeducational group program can encourage learning, peer support, and skill acquisition related to the four program themes of resilience, insight, self-compassion, and empowerment. The skills and knowledge associated with these concepts contribute to the enrichment of personal resources that are protective against the demands of the workplace.

Future research should include investigation into the impact of RISE for Nurse Leaders on the occupational status of participants, including retention, advancement, and unit-transfers. In addition, exploration of the experiences, satisfaction, and retention of direct care nurses who report to RISE for Nurse Leaders participants, as well as patient satisfaction scores, will help align the intervention aims with organizational return on investment.

Implications of this research include support of methodological approaches leveraged in the intervention, including the therapeutic foundations of CBT, ACT and mindfulness, group and individual peer support, skill acquisition, and emotional processing. In addition, this research adds to the body of knowledge regarding effective interventions to mediate burnout, which continues to be a driver of dissatisfaction and turnover in healthcare.

These qualitative findings can guide implementation efforts of wellbeing programs by organizational leaders in healthcare. Process improvement involves active feedback loops in which the experiences and suggestions of nurse leaders are considered in the adaptation of programming. Along with effective training, dissemination, and adoption by the community, implementation efforts must involve stakeholder perspectives to allow the program to be tailored to local contexts while upholding fidelity.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because all transcripts are confidential. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Amanda Sawyer, YW1hbmRhLnNhd3llckBhZHZlbnRoZWFsdGguY29t.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by AdventHealth Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SH: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/forgp.2024.1433400/full#supplementary-material

References

Adriaenssens, J., Hamelink, A., and Bogaert, P. V. (2017). Predictors of occupational stress and well-being in First-Line Nurse Managers: a cross-sectional survey study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 73, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.05.007

Akerjordet, K., and Severinsson, E. (2008). Emotionally intelligent nurse leadership: a literature review study. J. Nurs. Manag. 16, 565–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00893.x

American Counseling Association (2014). 2014 ACA Code of Ethics. Available at: https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/ethics/2014-aca-code-of-ethics.pdf?sfvrsn=55ab73d0_1 (accessed August 1, 2014).

American Group Counseling Association (2007). Practice Guidelines for Group Psychotherapy. Available at: https://www.agpa.org/home/practice-resources/practice-guidelines-for-grouppsychotherapy (accessed June 16, 2007).

American Nurses Association (2017). Executive Summary: American Nurses Association Health Risk Appraisal. Key Findings: October 2013–October 2016. American Nurses Association. Available at: https://www.nursingworld.org/~4aeeeb/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/work-environment/health–safety/ana-healthriskappraisalsummary_2013-2016.pdf (accessed May 16, 2016).

Andrews, H., Tierney, S., and Seers, K. (2020). Needing permission: the experience of self-care and self-compassion in nursing: a constructivist grounded theory study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 101:6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103436

Assi, M. D., Eshah, N. F., and Rayan, A. (2022). The relationship between mindfulness and conflict resolution styles among nurse managers: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Nurs. 8:23779608221142371. doi: 10.1177/23779608221142371

Aydogdu, A. L. F. (2023). Challenges faced by nurse managers during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review. J. Res. Nurs. 28, 54–69. doi: 10.1177/17449871221124968

Bailey, A. K., Sawyer, A. T., and Robinson, P. S. (2023). A psychoeducational group intervention for nurses: rationale, theoretical framework, and development. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurs. Assoc. 29, 232–240. doi: 10.1177/10783903211001116

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 43, 83–104. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20004

Barello, S., Caruso, R., Palamenghi, L., Nania, T., Dellafiore, F., Bonetti, L., et al. (2021). Factors associated with emotional exhaustion in healthcare professionals involved in the COVID-19 pandemic: an application of the job demands-resources model. Int. Archiv. Occup. Environ. Health 94, 1751–1761. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01669-z

Barrett, K., and Stewart, I. (2021). A preliminary comparison of the efficacy of online Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) stress management interventions for social and healthcare workers. Health Soc. Care Commun. 29, 113–126. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13074

Baudoin, C. D., McCauley, A. J., and Davis, A. H. (2022). New graduate nurses in the intensive care setting: preparing them for patient death. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 34, 91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2021.11.007

Bender, A. E., Berg, K. A., Miller, E. K., Evans, K. E., and Holmes, M. R. (2021). “Making sure we are all okay”: healthcare workers' strategies for emotional connectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin. Soc. Work J. 49, 445–455. doi: 10.1007/s10615-020-00781-w

Blackburn, L. M., Thompson, K., Frankenfield, R., Harding, A., and Lindsey, A. (2020). The THRIVE© program: building oncology nurse resilience through self-care strategies. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 47, E25–E34. doi: 10.1188/20.ONF.E25-E34

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualit. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, P., Fraser, K., Wong, C. A., Muise, M., and Cummings, G. (2013). Factors influencing intentions to stay and retention of nurse managers: a systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 21, 459–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01352.x

Choi, P. P., Lee, W. M., Wong, S. S., and Tiu, M. H. (2022). Competencies of nurse managers as predictors of staff nurses' job satisfaction and turnover intention. Int. J. Environ.Res. Publ. Health 19:1811461. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811461

Cooper, A. L., Brown, J. A., Rees, C. S., and Leslie, G. D. (2020). Nurse resilience: a concept analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 29, 553–575. doi: 10.1111/inm.12721

Corey, M., Corey, G., and Corey, C. (2014). Groups: Process and Practice, 9th Edn. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Couser, G., and Cutshall, S. (2020). Developing a course to promote self-care for nurses to address burnout. Online J. Issues Nurs. 25, 1–16. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol25No03PPT55

Creswell, J. W., and Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theor. Into Pract. 39, 124–130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Cziraki, K., McKey, C., Peachey, G., Baxter, P., and Flaherty, B. (2014). Factors that facilitate registered nurses in their first-line nurse manager role. J. Nurs. Manage. 22, 1005–1014. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12093

de Pablo, G. S., Vaquerizo-Serrano, J., Catalan, A., Arango, C., Moreno, C., Ferre, F., et al. (2020). Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 275, 48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.022

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86:499. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

d'Ettorre, G., Ceccarelli, G., Santinelli, L., Vassalini, P., Innocenti, G. P., Alessandri, F., et al. (2021). Post-traumatic stress symptoms in healthcare workers dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:601. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020601

Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., and Cruz, B. (2016). Relationships between nurses' empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 60, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015

Gaudine, A., Patrick, L., and Busby, L. (2019). Nurse leaders' experiences of upwards violence in the workplace: a systematic review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 17, 627–632. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003765

Gaupp, R., Walter, M., Bader, K., Benoy, C., and Lang, U. E. (2020). A two-day acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) workshop increases presence and work functioning in healthcare workers. Front. Psychiat. 11:861. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00861

Germer, C. K., and Neff, K. D. (2013). Self-compassion in clinical practice. J. Clin. Psychol. 69, 856–867. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22021

Gray, P., Senabe, S., Naicker, N., Kgalamono, S., Yassi, A., and Spiegel, J. M. (2019). Workplace-based organizational interventions promoting mental health and happiness among healthcare workers: a realist review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 16:224396. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224396

Green, J. F., Brennan, A. M., Sawyer, A. T., Celano, P., and Robinson, P. S. (2023). Self-care laddering: a new program to encourage exemplary self-care. Nurs. Lead. 21, 290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2022.09.005

Grover, S. L., Teo, S. T., Pick, D., and Roche, M. (2017). Mindfulness as a personal resource to reduce work stress in the job demands-resources model. Stress Health 33, 426–436. doi: 10.1002/smi.2726

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Hart, P. L., Brannan, J. D., and De Chesnay, M. (2014). Resilience in nurses: an integrative review. J. Nurs. Manag. 22, 720–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01485.x

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., and Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., and Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qualit. Health Res. 27, 591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344

Hewko, S. J., Brown, P., Fraser, K. D., Wong, C. A., and Cummings, G. G. (2015). Factors influencing nurse managers' intent to stay or leave: a quantitative analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 23, 1058–1066. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12252

Hoet, A. C., Burgin, C. J., Eddington, K. M., and Silvia, P. J. (2018). Reports of therapy skill use and their efficacy in daily life in the short-term treatment of depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 42, 184–192. doi: 10.1007/s10608-017-9852-y

Huang, J., Wang, Y., and You, X. (2016). The job demands-resources model and job burnout: the mediating role of personal resources. Curr. Psychol. 35, 562–569. doi: 10.1007/s12144-015-9321-2

Hughes, V. (2019). Nurse leader impact: a review. Nurs. Manag. 50, 42–49. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000554338.47637.23

Hugh-Jones, S., Rose, S., Koutsopoulou, G. Z., and Simms-Ellis, R. (2018). How Is stress reduced by a workplace mindfulness intervention? A qualitative study conceptualising experiences of change. Mindfulness 9, 474–487. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0790-2

Jäppinen, K., Roos, M., Slater, P., and Suominen, T. (2022). Connection between nurse managers' stress from workload and overall job stress, job satisfaction and practice environment in central hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 42, 109–116. doi: 10.1177/20571585211018607

Joyce, S., Shand, F., Tighe, J., Laurent, S. J., Bryant, R. A., and Harvey, S. B. (2018). Road to resilience: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resilience training programmes and interventions. Br. Med. J. Open 8:e017858. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017858

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. 10, 144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Karagiozi, K., Margaritidou, P., Tsatali, M., Marina, M., Dimitriou, T., Apostolidis, H., et al. (2022). Comparison of on site versus online psycho education groups and reducing caregiver burden. Clin. Gerontol. 45, 1330–1340. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2021.1940409

Kath, L. M., Stichler, J. F., and Ehrhart, M. G. (2012). Moderators of the negative outcomes of nurse manager stress. J. Nurs. Admin. 42, 215–221. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31824ccd25

Kath, L. M., Stichler, J. F., Ehrhart, M. G., and Sievers, A. (2013). Predictors of nurse manager stress: a dominance analysis of potential work environment stressors. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 50, 1474–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.011

Kelly, L. A., Lefton, C., and Fischer, S. A. (2019). Nurse leader burnout, satisfaction, and work-life balance. J. Nurs. Admin. 49, 404–410. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000784

Khurshid, Z., De Brún, A., Moore, G., and McAuliffe, E. (2020). Virtual adaptation of traditional healthcare quality improvement training in response to COVID-19: a rapid narrative review. Hum. Resour. Health 18, 1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00527-2

Kramer, M., Maguire, P., Schmalenberg, C., Brewer, B., Burke, R., Chmielewski, L., et al. (2007). Nurse manager support: what is it? Structures and practices that promote it. Nurs. Admin. Q. 31, 325–340. doi: 10.1097/01.NAQ.0000290430.34066.43

Labrague, L. J. (2020). Organisational and professional turnover intention among nurse managers: a cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manag. 28, 1275–1285. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13079

Labrague, L. J., McEnroe-Petitte, D. M., Leocadio, M. C., Van Bogaert, P., and Cummings, G. G. (2018). Stress and ways of coping among nurse managers: an integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 27, 1346–1359. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14165

Lasater, K. B., Aiken, L. H., Sloane, D. M., French, R., Martin, B., Reneau, K., et al. (2021). Chronic hospital nurse understaffing meets COVID-19: an observational study. Br. Med. J. Qual. Saf. 30, 639–647. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011512

Lavoie-Tremblay, M., Gélinas, C., Aubé, T., Tchouaket, E., Tremblay, D., Gagnon, M. P., et al. (2022). Influence of caring for COVID-19 patients on nurse's turnover, work satisfaction and quality of care. J. Nurs. Manage. 30, 33–43. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13462

Lee, H., and Cummings, G. G. (2008). Factors influencing job satisfaction of front line nurse managers: a systematic review. J. Nurs. Manage. 16, 768–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00879.x

Lenferink, L., de Keijser, J., Eisma, M., Smid, G., and Boelen, P. (2020). Online cognitive-behavioural therapy for traumatically bereaved people: study protocol for a randomised waitlist-controlled trial. Br. Med. J. Open 10:e035050. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035050

Linton, M., and Koonmen, J. (2020). Self-care as an ethical obligation for nurses. Nurs. Ethics 27, 1694–1702. doi: 10.1177/0969733020940371

Liu, B., Zhao, H., and Lu, Q. (2021). Effect of leader mindfulness on hindrance stress in nurses: the social mindfulness information processing path. J. Adv. Nurs. 77, 4414–4426. doi: 10.1111/jan.14929

Lowe, M. A., Prapanjaroensin, A., Bakitas, M. A., Hites, L., Loan, L. A., Raju, D., et al. (2020). An exploratory study of the influence of perceived organizational support, coworker social support, the nursing practice environment, and nurse demographics on burnout in palliative care nurses. J. Hospice Palliat. Nurs. 22, 465–472. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000686

Martin, S. D., Urban, R. W., Foglia, D. C., Henson, J. S., George, V., and McCaslin, T. (2023). Well-being in acute care nurse managers: a risk analysis of physical and mental health factors. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 20, 126–132. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12646

Martínez, N., Connelly, C. D., Pérez, A., and Calero, P. (2021). Self-care: a concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 8, 418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2021.08.007

Melnyk, B. M., Kelly, S. A., Stephens, J., Dhakal, K., McGovern, C., Tucker, S., et al. (2020). Interventions to improve mental health, well-being, physical health, and lifestyle behaviors in physicians and nurses: a systematic review. Am. J. Health Promot. 34, 929–941. doi: 10.1177/0890117120920451

Membrive-Jiménez, M. J., Pradas-Hernández, L., Suleiman-Martos, N., Vargas-Román, K., Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A., Gomez-Urquiza, J. L., et al. (2020). Burnout in nursing managers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of related factors, levels and prevalence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 17:3983. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113983

Meng, L., Jin, Y., and Guo, J. (2016). Mediating and/or moderating roles of psychological empowerment. Appl. Nurs. Res. 30, 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.11.010

Mercado, M., Wachter, K., Schuster, R. C., Mathis, C. M., Johnson, E., Davis, O. I., et al. (2022). A cross-sectional analysis of factors associated with stress, burnout and turnover intention among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the united states. Health Soc. Care Commun. 30, e2690–e2701. doi: 10.1111/hsc,.13712

NSI Nursing Solutions, I. (2023). 2023 NSI National Health Care Retention and RN Staffing Report. Available at: https://www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Documents/Library/NSI_National_Health_Care_Retention_Report.pdf (accessed May 26, 2023).

Ogilvie, L., Larkin, T. J., and Keller-Unger, J. L. (2021). Unconscious bias and self-care: key components of an integrated, comprehensive health care system nurse manager leadership development program. Nurse Lead. 19, 250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2021.02.012

Olmos-Vega, F. M., Stalmeijer, R. E., Varpio, L., and Kahlke, R. (2023). A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med. Teach. 45, 241–251. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

Papadopoulos, I., Lazzarino, R., Koulouglioti, C., Aagard, M., Akman, Ö., Alpers, L.-M., et al. (2021). The importance of being a compassionate leader: the views of nursing and midwifery managers from around the world. J. Transcult. Nurs. 32, 765–777. doi: 10.1177/10436596211008214

Penconek, T., Tate, K., Bernardes, A., Lee, S., Micaroni, S. P. M., Balsanelli, A. P., et al. (2021). Determinants of nurse manager job satisfaction: a systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 118:103906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103906

Peterson, U., Bergström, G., Samuelsson, M., Asberg, M., and Nygren, A. (2008). Reflecting peer-support groups in the prevention of stress and burnout: randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 63, 506–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04743.x

Prudenzi, A., Graham, C. D., Flaxman, P. E., Wilding, S., Day, F., and O'Connor, D. B. (2022). A workplace Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) intervention for improving healthcare staff psychological distress: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 17:e0266357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266357

Raab, K. (2014). Mindfulness, self-compassion, and empathy among health care professionals: a review of the literature. J. Health Care Chaplain. 20, 95–108. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2014.913876

Rajandram, R. K., Jenewein, J., McGrath, C., and Zwahlen, R. A. (2011). Coping processes relevant to posttraumatic growth: an evidence-based review. Support. Care Cancer 19, 583–589. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1105-0

Reschke, D. J., Dawber, C., Millear, P. M., and Medoro, L. (2021). Group clinical supervision for nurses: process, group cohesion and facilitator effect. Austral. J. Adv. Nurs. 38, 66–74. doi: 10.37464/2020.383.221

Robertson, I. T., Cooper, C. L., Sarkar, M., and Curran, T. (2015). Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: a systematic review. J. Occup. Organ.Psychol. 88, 533–562. doi: 10.1111/joop.12120