- 1Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, ON, Canada

- 2Department of Social Psychology and Quantitative Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

- 3King's College London, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, London, United Kingdom

Following the logic of the “happy-productive worker” hypothesis, organizations have been increasingly interested in new ways to elicit employee wellbeing. Consequently, research on mindfulness in work contexts has been burgeoning in recent years, as both conceptual and empirical reviews substantiated its importance as a cost-effective approach to promoting employee wellbeing. The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether employee happiness extends or transcends the conventional notions of employee wellbeing. More specifically, we invoke the positive psychology literature to argue that (a) employee happiness is related but distinct from employee wellbeing and (b) that initial levels of employee wellbeing might moderate the effect of mindfulness-based interventions. We conducted a secondary analysis of a publicly available dataset to test our predictions: focusing on 35 healthcare professionals from a healthcare organization in Barcelona, Spain. More precisely, employing a multivariate hierarchical regression, we compared if the incremental effect of an eight-week mindfulness-based strength intervention (MBSI) over a Mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) might be moderated by employees' initial levels before the intervention starts. Our results supported a moderating effect of employees' initial psychological wellbeing on a MBSI versus MBI. Implications for theory and practice are discussed.

Introduction

Almost a century ago, the “Hawthorne studies” showed that there is a compelling business case for promoting employee happiness beyond the inherent value of creating environments that support peak performance and optimal functioning (for a review, see Peiró et al., 2019). Yet, a 100 years later, it still is unclear to organizational psychologist of what “happiness” would mean in work contexts. For example, within the organizational psychology literature, job satisfaction, employee wellbeing, and happiness are three constructs that tend be used interchangeably when referring to the idea behind the “happy-productive worker” hypothesis.

However, some conceptual clarification might be useful to better understand what the happy-productive worker hypothesis entails. Such clarification is important to avoid the “jingle-jangle” fallacy (Thorndike, 1904) when studying employee health and wellbeing. In short, the jingle-jangle fallacy refers to the erroneous assumption that two different things are the same (i.e., labeling “jingle” as “jangle” and “jangle as “jingle”). We illustrate this by comparing job satisfaction, employee wellbeing, and employee happiness in work contexts.

As Judge et al. (2001) argued, job satisfaction is probably one of the most researched outcomes in I/O psychology. Job satisfaction captures positive attitudes of employees toward different facets of their work, such as pay, coworkers, supervisors, processes, and so forth (Spector, 1985). Job satisfaction matters, because the meta-analytic link between job satisfaction and performance has been thoroughly established (Judge et al., 2001), and a 2023 survey by the Pew Center show that, in general, 51% of US employees report being satisfied with their jobs (Horowitz and Parker, 2023). With the emergence of the positive psychology movement, and its application to promote wellbeing in work settings (e.g., Peterson and Park, 2006), organizational psychologists seem to have shifted their focus, moving from the study of job satisfaction toward the study of employee wellbeing.

One reason for this shift might be that focusing on employee wellbeing allows thinking about the happy-productive worker hypothesis in a new perspective not captured by the study of job satisfaction. For example, the same 2023 survey by the Pew Center shows that when inspecting among generational cohorts, people aged 18–29 have lowest wellbeing when compared to other generational cohorts, only 44% see their jobs as enjoyable and 39% as fulfilling. Instead, again, young adults between 18 and 29 find their jobs as more stressful (32%) and overwhelming (23%) than other generational cohorts (Horowitz and Parker, 2023). The discrepancy here has implications for practice given that if managers focus on job satisfaction metrics rather than the employee wellbeing metrics, managers might make wrong decisions, given that nowadays it is not enough for employees to be content or satisfied with their jobs, but there is an increasing need to find a deeper sense of purpose and fulfillment in it.

The increasing interest in employee wellbeing seems to generalize to other geographical contexts as well. An econometric study spanning 20 European countries highlight the considerable productivity gains associated with positive subjective wellbeing (DiMaria et al., 2020). DiMaria et al. (2020) underscore the concrete organizational benefits of prioritizing employee subjective wellbeing, emphasizing the substantial economic advantages of such efforts. Thus, under the premise that a happy worker is a productive worker, fostering employee wellbeing seems to be an inherently worthy endeavor that might also be good for business.

Now that the productivity gains from promoting employee wellbeing are widely acknowledged in organizations, a pertinent question might arise for organizational decision makers: Is fostering employee satisfaction and wellbeing enough to sustain organizational productivity in our firm? Or should our organization strive to surpass the pursuit of employee satisfaction and wellbeing and cultivate instead an enduring sense of happiness within their employees? If so, a relevant yet practical question said decision makers could ask is what interventions could increase employee happiness across varying baseline levels of employee wellbeing. We believe that exploring the above research questions empirically might provide a modest yet interesting contribution to the employee health and wellbeing literature.

Our first research objective is to explore antecedents of happiness at work. Our rationale being that if “a happy employee is a productive employee”, it would seem important for organizations to promote the happiness of their employees, as this will likely relate to productivity gains. Given that abundant research has been conducted on both the effect of job satisfaction (Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2024) and employee subjective wellbeing (e.g., Jebb et al., 2020) on employee productivity, the main objective of the present study is exploring what increases happiness in work contexts (further referred to as employee happiness).

Monzani et al. (2021a) established that a Mindfulness-Based Strengths Intervention (MBSI) promoted employee wellbeing above and beyond the effects of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI) for health care professionals. Based on the findings of Monzani et al. (2021a), we believe that the habitual practice of mindfulness alongside the activation of character strengths might be a cost-effective intervention that organizations should consider if interested in creating lasting employee happiness. Mindfulness involves the “self-regulation of attention with an approach of curiosity, openness, and acceptance” (Bishop et al., 2004, as cited in Niemiec and Lissing, 2016). It is the practice of intentionally focusing one's attention on the present moment without judgment, embodying a state of awareness without purpose or intent (Niemiec and Lissing, 2016).

However, Monzani et al. (2021a) did not explore if an MBSI would increase employee happiness above and beyond an MBI. Consequently, to purse this first research objective, the present study will benchmark the effect of two similar interventions on employee happiness. Given the exploratory nature of our first research objective, a secondary objective is required to qualify our potential findings. Thus, our secondary objective is to determine under which conditions these interventions are more effective. As we elaborate on below, we anticipate that there will be differences in employee happiness according to the baseline level of participants' psychological wellbeing.

Thus, the present study reports a secondary analysis of a publicly available dataset published by Monzani et al. (2021a). We aim to contribute to this field by exploring whether a MBSI, like Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice (MBSP; Niemiec, 2014), can enhance employee happiness after controlling for baseline levels of hedonic and eudaimonic (described next) employee wellbeing, as well as related constructs, such as psychological needs satisfaction (Deci and Ryan, 2000). As such, the present study joins an ongoing conversation among positive organizational scholars about what practices enable employees to achieve optimal functioning at work (Youssef and Luthans, 2007).

Theoretical framework

Employee happiness

Recent theoretical and empirical findings support the idea that achieving happiness at work is both possible and valuable for organizations. Although counter-intuitive, the positive psychology literature argues that happiness and wellbeing are two separate constructs with clear differences. We unpack those differences below, and then present recent empirical studies identifying antecedents and mechanisms of employee happiness in the following paragraphs.

The first difference between happiness and wellbeing is how they are conceptualized. Happiness in general has been theorized and studied as a unidimensional construct, whereas the extant literature agrees that wellbeing is a multi-dimensional construct (e.g., hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing). For example, hedonic wellbeing has been defined as the pursuit of pleasurable emotional states and the avoidance of dis-pleasurable states. In general, Diener's notion of life satisfaction describes hedonic wellbeing (Kahneman et al., 1999), and in work contexts, job satisfaction is a metric that captures employee hedonic wellbeing. Finally, Monzani et al. (2021a) evidenced that Watson et al.'s (1988) measure of positive affect can be used as a metric for the pleasurable states inherent to hedonic wellbeing in healthcare contexts.

In line with the Aristotelian Virtue Ethics tradition, positive psychologists understand psychological (or eudaimonic) wellbeing as a deeper search for meaning, purpose, and self-actualization, even if such pursuit requires a temporary state of dis-pleasure in sights of distal and more lasting sense of subjective wellbeing (Waterman, 2008). Happiness scholars argue that although very valuable, these two types of wellbeing are distinct from an overall sense of happiness (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999; Lyubomirsky et al., 2011), understood as a trait-like personal attribute rather than a psychological state (Raibley, 2012). It seems plausible then that employee psychological wellbeing should be related or even be an antecedent of employee happiness.

Given the various dimensions of wellbeing and happiness explored above, it is also important to recognize how different cultural contexts shape these constructs. In the eastern cultures of Southern Asia, such as India, bringing one's spirituality to the work context is not unusual. Despite that workplace spirituality emanates from a different philosophical tradition, workplace spirituality has shown to have similar relations to the work-related outcomes studied in Western Cultures. For example, in a sample composed of 207 manufacturing and service managers spread across different locations throughout India, workplace spirituality predicted employee job satisfaction, affective and normative commitment, as well as work engagement (Garg, 2017). Moreover, and more closely related to the present study, extant research also identified gratitude as an individual factor that has been related to employee happiness (Garg et al., 2022). Finally, a study by Garg et al. (2022) advanced the literature on employee (and workplace) happiness, by evidencing how both psychological and social capital mediate the relation between employee happiness and one of its antecedents (e.g., gratitude) in educational contexts.

Insights from both Western and Eastern traditions remind us that working should be more than trading hours for a paycheque. Moreover, extant research on employee attitudes and psychological states supports these insights. Thus, as theory and practice consistently suggest that there is value in findings new ways to promote happiness at work, in the next sections, we propose an intervention that draws from Western and Eastern philosophical traditions to increase employee happiness, after isolating the effect of the antecedents of happiness described above.

Mindfulness

Our literature review shows that mindfulness research has grown exponentially in the last decades. As empirical findings suggest, the habitual practice of mindfulness increases a person's self-awareness, helps to identify blind spots in self-knowledge, and assists in the aligning of a person's actual self (who one perceives to be) and our ideal self (whom one aspires to be; Brown et al., 2007; Ivtzan et al., 2011; Carlson et al., 2013; Niemiec and Lissing, 2016). Therefore, it is unsurprising that several types of MBIs have emerged in recent decades.

MBIs are intentionally structured programs integrating mindfulness principles and techniques into Western psychology practices. Various programs and therapies, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Kabat-Zinn, 2003), Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (Segal et al., 2018), and Mindful Self-Compassion (Germer and Neff, 2019) are conceptually grounded on MBIs. We focus on a MBSP (Niemiec, 2014), a program designed to target character strengths and mindfulness. More recently, MBIs have captured the interest of HR and talent managers, given their capacity to elicit employee wellbeing (Good et al., 2016; Monzani et al., 2021a).

Mindfulness at work

Management scholars are increasingly focused on understanding how firms integrate mindfulness and character development into their daily activities, recognizing the potential for these practices to enhance organizational effectiveness, employee wellbeing and overall performance. A recent integrative review has summarized the extensive literature on mindfulness in work contexts, unpacking its primary mechanisms and relation to employee outcomes (Good et al., 2016). In short, these authors conclude that the habitual exercise of entering a mindfulness state expands how employees perceive and experience their work tasks by shifting from cognitive to experiential information processing, enhancing employee focus and attention.

A recent second-order meta-analysis, summarizing 13 first-order meta-analyses and comprising of 311 intervention studies, demonstrates the significant impact that mindfulness practices have in several work contexts—a medium-to-large meta-analytic effect on improving hedonic wellbeing by reducing negative emotions (g = −0.74) and increasing overall eudaimonic wellbeing (g = 0.58), as predicted (Monzani et al., 2021a). Two considerations arise from Monzani et al.'s (2021a) results. First, Hedges g is an effect size measure akin to Cohen's d, but it is advantageous in that it is a robust statistic that corrects for small sample sizes, and as such increases its credibility. Second, we can convert Monzani et al.'s (2021a) Hedges' values (i.e., g = −0.74 and g = 0.58) to their comparable Pearson's bivariate correlation values (r = 0.35 and r =0.28, respectively). Because Monzani et al. (2021a) conducted this second-order meta-analysis while correcting for the sampling variance of 13 first-order meta-analyses (i.e., based on 311 studies with a combined sample size of approximately 19,000 participants) and reported pooled reliability estimates (e.g., 0.88 and 0.86 for the outcome measures), it seems likely that these values approximate the true population effect sizes of MBIs on both hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing criteria. However, because these authors were pursuing a different study objective than the present study, Monzani et al. (2021a) did not produce meta-analytical estimates of the effect of MBIs on employee happiness as defined above. Our study aims to advance a step forward in this direction, by exploring the gap that Monzani et al.'s (2021a) study omitted, without attempting to conduct another meta-analysis.

Monzani et al.'s (2021a) results illustrate how mindfulness positively affects employees operating within high-stress environments. We believe that those effects occur because habitual mindfulness practices facilitate a shift in consciousness from cognitive processing to experiential awareness, offering a valuable coping mechanism to deal with an overwhelming amount of information that leaders and employees are exposed and expected to process in modern work environments. Some examples include a constant stream of emails, messages, reports, data, and tasks that can lead to feeling overwhelmed, difficulty focusing, and difficulty prioritizing tasks.

Mindfulness practices, as demonstrated by Monzani et al. (2021a), help individuals manage this overload by improving focus, attention, and the ability to stay present in the moment rather than getting caught up in the sheer volume of information. In other words, it gives individuals the means to cope with information overload across diverse work settings. Thus, benchmarking how different MBI types affect employee happiness is an important endeavor that should be of interest to other organizational stakeholders (talent mangers, managers, etc.).

Developing character in organizations

The contemporary understanding of character draws heavily from the definition of virtuous character in the Aristotelian virtue ethics tradition (Aristotle, 2014). More precisely, it speaks to the qualities and attributes defining an individual's excellence and enabling them to achieve optimal functioning across various social contexts (Wright and Huang, 2008; Crossan et al., 2013; Niemiec, 2018). This definition includes integrity, empathy, judgment, and courage, which shape how individuals interact with others and influence their decision-making processes, ethical behavior, and overall effectiveness in both personal and professional lives. Suppose one's character is understood as the set, or collection, of qualities and attributes that define an individual's excellence. In that case, the strength of one's character is cultivated through the conscious and habitual practice of moral and ethical values, virtuous behaviors, and even an adaptive activation of inherited traits. Positive psychology literature often delineates these collections as character strengths (Seligman and Peterson, 2004).

Character strengths, as defined by the Values in Action Inventory (VIA; Seligman and Peterson, 2004) and MBSP (Niemiec, 2014), encompass a range of positive attributes such as kindness, gratitude, humility, self-regulation, and perseverance, among others. Engaging in behaviors that align with these character strengths enhances personal wellbeing and contributes to a fulfilling and purposeful life (Schutte and Malouff, 2019; Bates-Krakoff et al., 2022). Similarly, recent integrative reviews have sparked renewed scholarly interest in understanding how the habitual practice of character within work contexts translates into increased employee performance and wellbeing (Seligman and Peterson, 2004; Peterson and Park, 2006; Wright et al., 2007; Donaldson and Ko, 2010; Donaldson et al., 2019; Monzani et al., 2021b; Seijts et al., 2022). Donaldson et al.'s (2019) meta-analysis of positive psychology interventions at work show that character-strengths based interventions had a moderate effect (g = 0.35) on employee wellbeing. Despite this effect, it is not as substantive as the effect of MBIs on employee wellbeing, Monzani et al. (2021a) argue, that it might be compounded with it. Thus, it seems logical for organizations interested in attracting, retaining, and developing talent to promote practices that enable individuals to achieve optimal functioning at work. A recent Society for Human Resources Management report found a $4 return on investment for every $1 spent on workplace wellbeing (Milligan, 2017; Ellis et al., 2024).

Enhancing employee happiness by integrating mindfulness and character

Monzani et al. (2021a) evidenced that wellbeing practices that blend mindfulness and character strengths development were more effective in promoting employee wellbeing than mindfulness-based practices alone. Their logic posits that the two foundational traditions underlying these wellness practices are not antagonistic but synergistic, meaning they could mutually reinforce their effects. However, as previously noted, there is limited evidence within work contexts to determine if this synergistic effect also extends and applies to employees' overall general assessments of their happiness levels, as operationalized by scholars such as Lyubomirsky and Lepper (1999).

Building on the logic of positive organizational scholars, human endeavors such as ventures and enterprises could also provide a fertile ground for achieving eudaimonia—a state of enduring happiness grounded in purpose, meaning, and harmony between individuals and their environments. Eudaimonic happiness differs from hedonic happiness, a concept akin to the contemporary view of happiness, that is, as reducing displeasure and increasing pleasurable states (Ryan and Deci, 2001). While extrinsic rewards, such as promotions, bonuses, and other status-enhancing practices might create a temporary bump in hedonic happiness, this bump is usually short-lived (as are the associated wellbeing implications).

Hedonic wellbeing interventions tend to be short-lived. This reduced half-life happens because sustaining hedonia requires constant reinforcement, or what some scholars have termed the hedonic treadmill (Waterman, 2007). The notion of a hedonic treadmill refers to the tendency for individuals to return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite experiencing positive or negative life events. The treadmill metaphor implies that even temporary boosts or drops in happiness due to life events, such as getting a promotion (hedonic boost), or a breakup (hedonic drop) tend to return to a baseline level over time. This concept implies that material gains or setbacks might not have a lasting impact on overall employees' wellbeing or employee happiness.

The second-order meta-analysis conducted by Monzani et al. (2021a) showed that existing MBIs are very effective in reducing negative emotional states (hedonic wellbeing) and increasing overall wellbeing (eudaimonic wellbeing). These findings suggest that MBIs could also effectively increase employee happiness levels. Specifically, in their follow-up field experiment, comparing the effects of an MBI to an MBSI on employee wellbeing (considering both its hedonic and eudaimonic facets), the most significant increase across conditions was observed in the facet of Ryff and Keyes's (1995) measure of psychological wellbeing (focused on positive relations with others). This effect remained significant even after controlling for employees' degree of psychological needs satisfaction (Deci and Ryan, 2000).

The results reported by Monzani et al. (2021a) leads us to theorize that once the need for relatedness is fulfilled, the practice of MBSI not only opens the door to a higher level of eudaimonic wellbeing (which was substantiated by the authors) but might also enable a deeper sense of overall happiness (Deci and Ryan, 2008), which we operationalized as employee happiness, as discussed above. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: A Mindfulness-Based Strengths Intervention (MBSI) is more effective than a Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI) in promoting employee eudaimonic happiness (Time 8).

Exploring boundary conditions: the moderator effect of baseline wellbeing

Given that Monzani et al. (2021a) randomly assigned participants to their experimental conditions, the assumption is that initial levels of individual differences would also be randomly distributed across conditions. However, it is plausible that even after a random assignment, participants might still vary in their initial levels of less easily observable constructs, such as initial psychological states and psychological wellbeing. Given that both theoretical (Ryan and Deci, 2001) and empirical studies (e.g., Dogan et al., 2013) suggest a connection between psychological wellbeing and happiness (as related constructs), it is plausible that the baseline levels of psychological wellbeing could influence and impact the outcome effects of these interventions on employee happiness.

More precisely, drawing from the meta-analytic findings by Monzani et al. (2021a), it is evident that MBIs are more effective at reducing negative emotional states compared to increasing overall wellbeing in a general context. Concurrently, research suggests that character strengths interventions alone have a strong positive impact on psychological wellbeing compared to other positive interventions in work contexts (see Donaldson et al., 2019) such as work-life balance initiatives, positive feedback and recognition, training in emotional intelligence, or social support programs.

The MBSI, which integrates character development alongside mindfulness, might not yield significant additional or incremental effects on related constructs, such as employee eudaimonic happiness, particularly if employees already experience high levels of psychological wellbeing (i.e., a ceiling effect; Vogt, 2005). A ceiling effect would suggest then that an MBSI might be more efficient in promoting employee happiness for those employees with lower levels of baseline wellbeing. As character strength use becomes a habit of being, it facilitates cultivating improved relationships with others and attaining a newfound sense of self-mastery, autonomy, and so forth. Engaging in the concurrent development of one's character alongside mindfulness offers individuals with low-baseline wellbeing a pathway to cultivate eudaimonic happiness. This process involves a deliberate focus on bridging the gap between their current state of functioning and an ideal state of optimal performance and fulfillment within their work. This expectation stems from the notion that mindfulness can enhance an individual's experiential awareness of their current levels of psychological wellbeing, enabling individuals to gain a higher awareness and appreciation of the goodness within and around them. In that sense, MBIs amplify the consciousness recognition of the positive facets of psychological wellbeing that individuals are already experiencing. We therefore formulate the following exploratory hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Employees' initial psychological wellbeing levels (Time 1) moderates the incremental effect of an MBSI over an MBI on employee happiness (Time 8).

Materials and methods

Sample

We conducted a secondary analysis of an existing dataset utilized in the study by Monzani et al. (2021a). Since the present study utilized an existing dataset, the following description refers to the sampling design of the original Monzani et al. (2021a) study. The Monzani et al. (2021a) study involved 35 healthcare professionals from a healthcare organization in Barcelona, Spain.

The MBSI group comprised of 16 women and two men aged 18 to 33 (M = 23.72; SD = 5.17). The MBI group comprised of 16 women and one man, aged 17 to 40 years old (M = 23.58; SD = 7.34). The MBI group participated in mindfulness meditation activities concurrently for the same duration and number of weeks as the MBSI group (8 weeks). Specifically, the MBI group did not partake in activities designed to target and enhance the utilization and understanding of character strengths. The employed dataset is accessible on the Open Science Framework website under the following link: https://osf.io/q3phb/?view_only=6855880e05b7416db96eb3220892d104.

Procedure

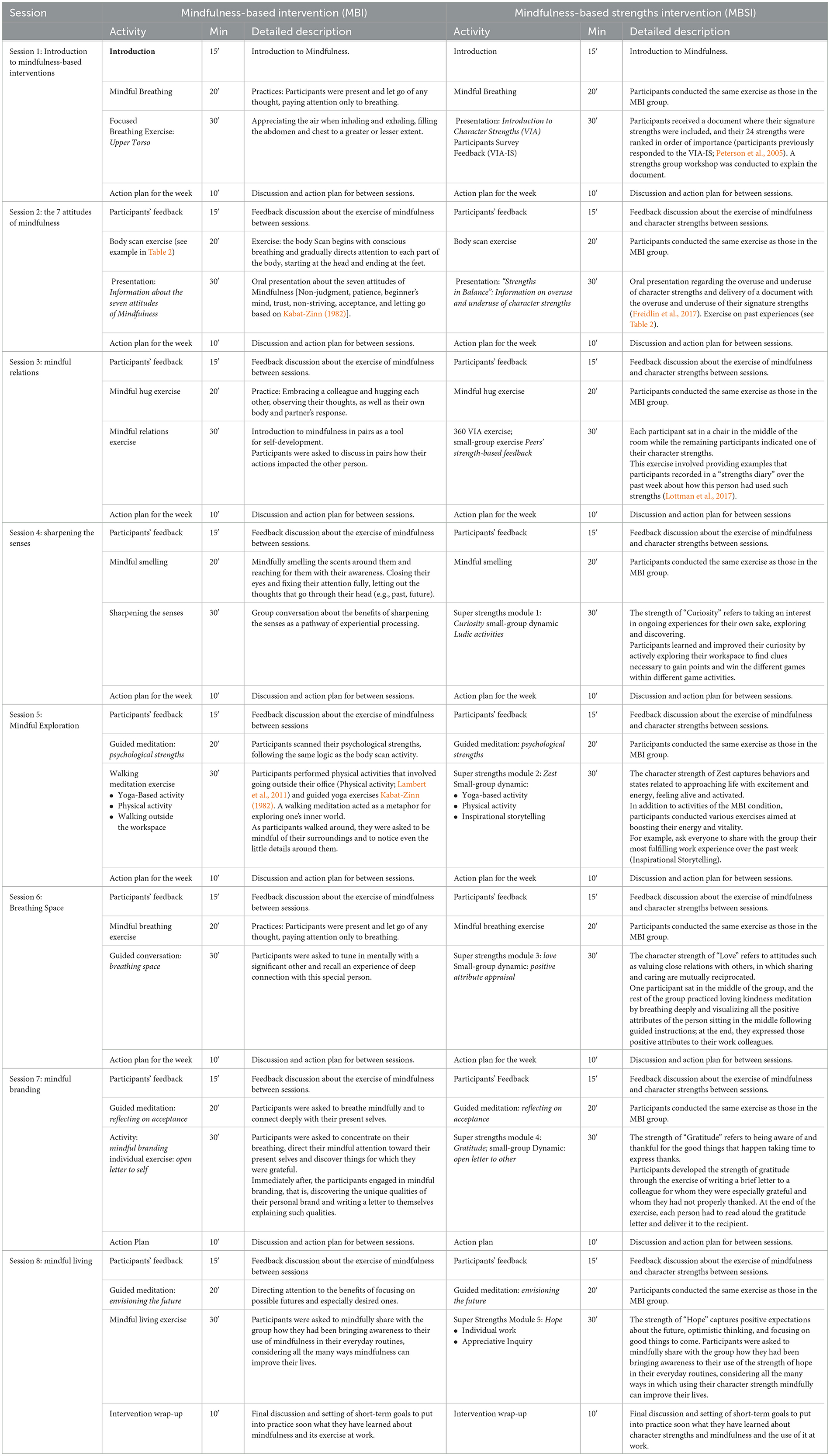

Given that the present work is a secondary analysis of a publicly available dataset, we only summarize the field experiment's procedure (for a full description, see Monzani et al., 2021a). Before the study began, participants were randomly assigned to the MBSI or MBI group. Similarly, before and after the sessions (Time 1 and Time 8, respectively), all participants were asked to complete self-report measures to capture any score variation. However, only the MBSI group participated in the character strength activities (see Table 1), which lasted 8 weeks (one session per week, for a total of eight sessions) and each session lasted 75 min (see Table 1).

Table 1. Comparative table for mindfulness-based intervention and mindfulness-based strengths intervention field experiment conditions.

As shown in Table 1, the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS; Peterson et al., 2005) self-assessment tool was used to rank participants' character strengths, providing insights into their top strengths, personal qualities, and virtues. In contrast, the MBI group only participated in mindfulness-based activities.

Monzani et al. (2021a) did not have a “pure” control group (i.e., “no-treatment”). That is, an MBI group was preferred to a pure control group approach to avoid the wait-list effect (Hesser et al., 2011), which refers to potential changes in participants' behavior or outcomes while they are in a control group awaiting an intervention, which they know they will receive.

Measures

Psychological need satisfaction

The Need Satisfaction scale (La Guardia et al., 2000) includes three items for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, respectively, with total need satisfaction assessed as the average of the nine items. This measure is well-suited for a work context as it assessed the fulfillment of basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—which are critical for employee motivation and wellbeing in organizational settings (Deci and Ryan, 2000) and have been linked to enhancing job satisfaction, performance, and reduced turnover (Van den Broeck et al., 2010).

Participants were asked to evaluate the extent to which their fundamental needs are fulfilled in the presence of specific target figures, such as their parents, romantic partner, best friend, roommate, and significant adult. This measure uses a 7-point Likert scale, where higher responses indicate a greater degree to which their psychological, emotional, and social needs are satisfied. Cronbach's alpha was α =0.85 for Time 1.

Positive affect

Ten items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scale developed by Watson et al. (1988) were used to assess positive affect. This scale comprises various descriptors of emotions and feelings, allowing participants to indicate the intensity of their positive emotional experiences. Participants matched their feelings to the words using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Very slightly or Not at All” to 5 = “Extremely”. Some sample items are “Hopeful” and “Excited”. Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.92 for Time 1.

Psychological unrest

The CORE-OM scale, Spanish version (Evans et al., 2002; Feixas et al., 2012) captured the dis-pleasurable facet of hedonic wellbeing. This scale describes the influence of feelings and emotions on daily functioning. Sample items are “Tension and anxiety have prevented me from doing important things” or “I have felt terribly alone and isolated”. Scores ranged from 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “most or all the time”. Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.92 for Time 1.

Psychological wellbeing (Spanish version)

To measure eudaimonic wellbeing, Díaz et al.'s (2006) Spanish version of the Ryff Psychological Wellbeing scale (Ryff and Keyes, 1995) was used. This scale comprehensively assesses an individual's psychological functioning across six dimensions, offering valuable insights into overall wellbeing (self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth). It consists of a total of 29 items, scored on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly disagree” to 6 = “Strongly agree”). Given our small sample size, we aggregated the different facets of wellbeing into a single indicator. Little et al. (2002) argue that parceling is justified when the factorial structure of a scale has been established. Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.82 for Time 1.

Employee happiness

We used three items from the Subjective Happiness Scale (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999). This scale consists of four items, with respondents providing ratings on a 7-point Likert scale. The first item was “In general, I consider myself...,” and the response scale ranged from 1 = “Not a very happy person” to 7 = “A very happy person”. The second item was “Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself…” and the response scale for this item ranged from 1 = “less happy” to 7 = “happier”. The third item was “Some people are generally very happy. They enjoy life regardless of what is going on, getting the most out of everything. To what extent does this characterization describe you?” and it ranged from 1 = “not at all” to 7 = “a great deal”. Cronbach's alpha was α = 0.83 for Time 1 and α =0.88 for Time 8.

Data analysis

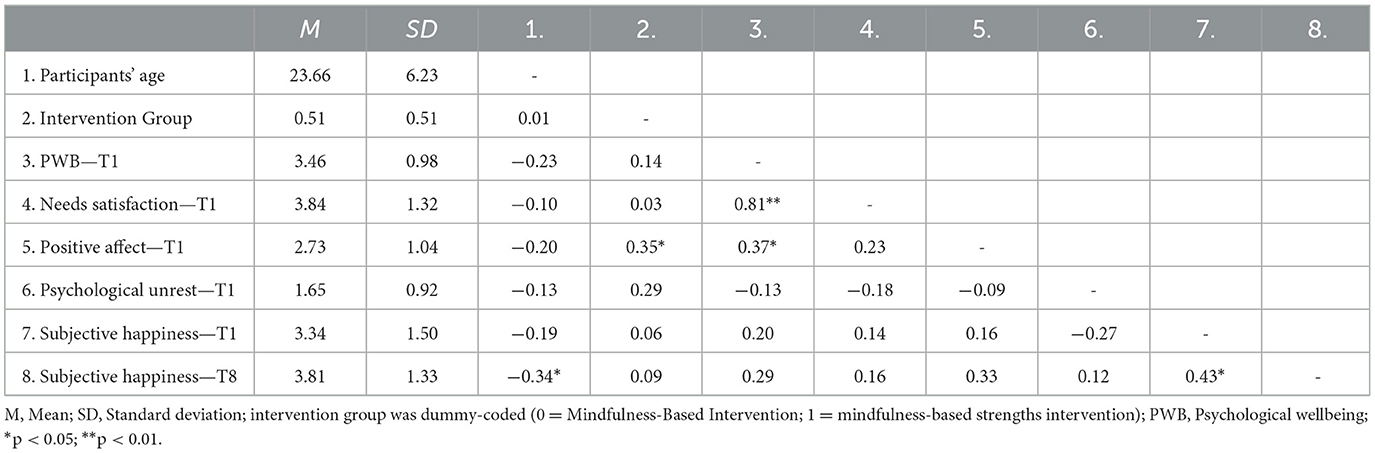

We began by assessing the simple associations between our variables, which allowed us to assess how related (or not) our constructs were to each other. Therefore, we used simple Pearson correlations between all our variables of interest. This included participant's age and intervention group (dummy-coded: 0 = MBI; 1 = MBSI); initial measures for psychological wellbeing, needs satisfaction, positive affect, psychological unrest, and subjective happiness (i.e., at Time 1); and a final measure for subjective happiness (i.e., at Time 8).

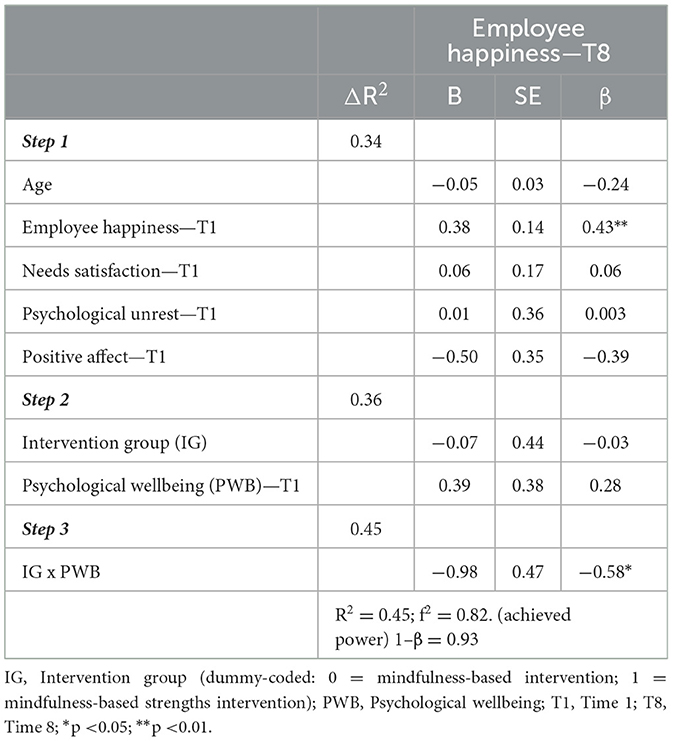

To test our hypotheses, we employed a multivariate hierarchical regression for the interactive effect of mindfulness-based intervention type and employees' initial levels of psychological wellbeing (Time 1) on employees' happiness (Time 8). We began by adding age and all baseline measures (Time 1): subjective happiness, need satisfaction, psychological unrest, and positive affect. Next, we added individual terms for the dummy-coded intervention group and psychological wellbeing (Time 1). Lastly, an interaction term was added for our intervention group and psychological wellbeing (Time 1). Dawson's (2013) guidelines were used for conducting simple slopes analysis.

Results

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and Pearson's bivariate correlations for all variables in our study. As expected, psychological wellbeing was positively correlated with both needs satisfaction and positive affect (all at Time 1), while participants' age negatively correlated with their final levels of subjective happiness (Time 8). The absence of other significant correlations might suggest the presence of potential interactive effects between the constructs (see Table 2).

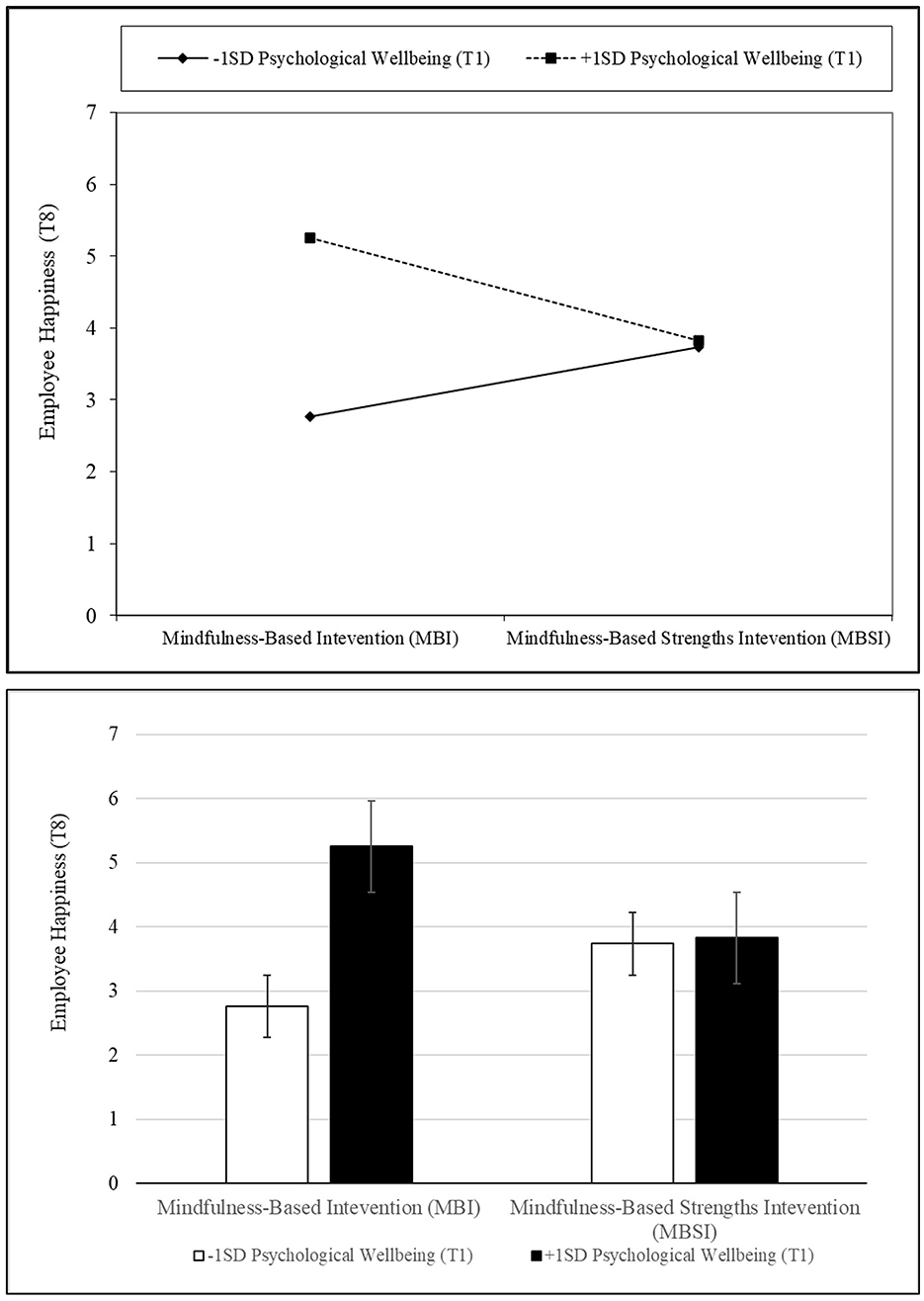

The regression coefficients in Table 3, alongside Figure 1, show how the initial levels of psychological wellbeing (Time 1) moderated the incremental effect of an MBSI intervention type (over an MBI) on employee happiness (Time 8). Simple slope analyses revealed a statistically significant slope for the MBSI intervention [β = −1.16, t(1, 27) = −3.09, p < 0.001]. In contrast, the slope for the MBI intervention was non-significant [β = 0.75, t(1, 27) = 0.75, p = 0.41; see upper panel of Figure 1]. This finding indicates that the effect of the MBSI intervention was substantially stronger in those participants with low initial levels of psychological wellbeing compared to those with high levels. There were no observable differences in employee happiness scores between intervention types when initial levels of psychological wellbeing were high (+1SD; see Figure 1). Our results do not support Hypothesis 1 but support Hypothesis 2.

Table 3. Multivariate hierarchical regression for the interactive effect of mindfulness-based intervention type and employees' initial levels of psychological wellbeing (time 1) on employees' happiness (time 8).

Figure 1. Interaction effect between intervention group and baseline levels of psychological wellbeing (Time 1) on employee happiness (Time 8).

Discussion

The present study assesses the effectiveness of two interventions on employee happiness. In the present study, happiness is understood as a personal attribute rather than a distinct psychological state separate from subjective wellbeing (Raibley, 2012). Our study offers a modest yet valuable empirical contribution to the literature on workplace wellbeing, particularly by exploring this question within a sample of healthcare professionals who must navigate high-stress work environments. Our study's relevance to workplace wellbeing is captured in the logic of the “happy-productive worker” hypothesis (Peiró et al., 2019).

We conducted a secondary analysis of a publicly available dataset to untangle the effects of positive interventions on employee happiness at different degrees of psychological wellbeing. More precisely, this dataset was utilized to examine the effectiveness of a MBSI in promoting employee wellbeing compared to a standard MBI. The longitudinal design of this field experiment allowed us to unpack if this type of intervention could explain changes in employee happiness, after isolating the effect of other related constructs. Interestingly, our results did not indicate a direct effect of the MBSI intervention on the change in employee happiness across time (Hypothesis 1).

Instead, we found that the predicted effect of the MBSI was contingent on the initial levels of psychological wellbeing (Hypothesis 2). Psychological wellbeing is a well-established measure of eudaimonic wellbeing, sometimes equated to happiness in the positive psychology literature (Ryan and Deci, 2001; Huta and Waterman, 2014). A finding that might be of interest to positive organizational scholars is that these results hold after controlling for initial levels of psychological needs satisfaction (Ryan and Deci, 2000), initial happiness levels, positive affect, psychological unrest, and participants' age, highlighting the nuanced relationship between participants' initial baseline levels of psychological wellbeing and the impact of these interventions. We discuss implications for theory and practice in the following sections.

Theoretical implications

Our study provides a modest yet meaningful contribution to the theoretical conversation on employee wellbeing and happiness (Huta and Ryan, 2010; Huta and Waterman, 2014). First, the results from our study contribute to expanding the nomological network of Lyubomirsky's (2007) happiness construct, by studying what increases happiness in work settings. Our results support the perspective that distinguishes happiness (at work) from (employee) wellbeing. Thus, as suggested in our earlier theorizing (Raibley, 2012), these constructs should not be used interchangeably in work settings. To the extent of our knowledge, our study is novel in that it is the first to benchmark how a MBSI influences employee happiness against a well-established MBI, after isolating the effect of other constructs that have been conceptually and empirically related to employee happiness.

Second, our findings provide a contribution that complements existing frameworks of mindfulness at work (Good et al., 2016). Good et al.'s (2016) framework organizes prior studies in work settings. These reviewed studies seem to have focused more deeply on the instrumental value of mindfulness, rather than its inherent spiritual value as millenary practice. In other words, these studies appear to portray mindfulness as a “tool” that can enhance individual performance, that is, the “productive” side of the “happy-productive worker” hypothesis. Our findings help to flip the script by showing that an enriched mindfulness program affects the “happy” side of the “happy-productive worker” equation.

Our enriched mindfulness intervention (i.e., the MBSI) has the potential to inform the emerging literature on workplace spirituality (Garg, 2017), and specifically as an intervention that can increase gratitude (Niemiec, 2012, 2022; Chérif et al., 2021). Although in Western cultures the notion of workplace spirituality might be frowned upon by some managers, it is an important aspect of work in other cultures that western cultures could learn from. We agree with Garg et al. (2022), that a happy workforce is an asset, and that “workplace happiness is [or should be] one of the most prized and sought-after goals for any organization” (p. 1). However, we also believe that employing MBIs for the pursuit of happiness through honest work is an inherently valuable endeavor worthy of scholarly attention, beyond its potential contribution to increasing organizational profits. In this regard, as an anonymous reviewer notices, our MSBI showed a clear compensatory effect for those who need it the most, as the improvement in employee happiness occurs in people who have low baseline psychological wellbeing.

The third theoretical insight of our work might inform the job crafting literature (Rudolph et al., 2017). Our results suggest that the habitual practice of mindfulness at work can increase employee functioning to optimal levels (Monzani et al., 2021a) and sustain such enhanced functioning through employee happiness. Incorporating a brief mindful practice when crafting job roles could allow employees to sustain optimal functioning in time. Therefore, future research should explore the synergistic effect of combining job crafting activities by incorporating MBI or MBSI practices and test their effectiveness in eliciting employee wellbeing and happiness.

Our results show that although all participants in the primary study performed similar job activities, the MBSI condition with lower baseline levels of psychological wellbeing (-1SD) reported experiencing even greater happiness by the end of the intervention (i.e., at Time 8) than those in the MBI condition. This finding suggests that when employees experience high levels of employee wellbeing, a ceiling effect to positive interventions on employee happiness might be triggered (for a detailed statistical explanation, see Vogt, 2005). Future studies should theoretically explore the why of this ceiling effect to support this logic further or challenge it with other counterfactual explanations.

Practical implications

This section addresses why organizational leaders and talent managers should prioritize embedding mindfulness character in organizations. First, addressing the apparent shift in employee expectations in a post-pandemic world is imperative. Promoting mental health and wellbeing at work is no longer seen as a work “perk” that separates “great places to work” from “not so great places to work”, but rather, these practices are now considered a baseline expectation. This last point seems particularly true for the new generational cohorts entering the workforce. In other words, although counter-intuitive for some managers, creating a culture of care, rather fostering intra-organizational competition, can be a source of competitive advantage when attempting to attract and retain talent, but more importantly, when attempting to develop talent (Ellis et al., 2024).

Our research has significant practical implications for talent management professionals interested in employing MBIs to promote workplace wellbeing in healthcare settings. The findings indicate that cultivating character alongside mindfulness matters more for fostering employee happiness in individuals experiencing symptoms of reduced wellbeing, such as work distress or burnout. Unfortunately, distress or burnout is extremely common in healthcare contexts, beyond the task-related demands of said work context (Buunk et al., 2010). On the other hand, MBIs and MBSIs were equally effective for healthcare professionals already at high levels of wellbeing despite operating in a highly stressful work context.

However, such organizational practices cannot endure without the support of organizational leaders. It is widely recognized that, for better or for worse, the actions and behaviors of organizational leaders serve as a model for the rest of the organization to emulate. Therefore, as leaders play a key role in shaping positive affective climates within teams and a firm's broader organizational culture (Monzani and Van Dick, 2020), they can support a culture of care if they champion initiatives oriented toward increasing workplace wellbeing and happiness. Finally, to provide a practical contribution for leaders and managers interested in promoting wellbeing and happiness at work, we offer a detailed description of our intervention in Table 1, which human resource and talent managers can easily implement and is, at first glance, more cost-effective than other alternatives.

Limitations

As with any other study, our work is not without limitations. First, although the primary study made a consistent effort to avoid a common source of bias in social sciences (e.g., tested the impact of an exogenous intervention in a field experiment and used a longitudinal design), all constructs in the primary study were self-reported (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Despite the idea that perceptions may be more important than objective data to understand what people feel, think, and do (Wood et al., 2011), future research might want to triangulate self-report data with other methods, such as physiological indicators of wellbeing (e.g., heart-rate variability, sleep pattern analysis, and so forth). Thus, combining self-reports with observational data would be valuable.

Second, this study did not have a pure control condition. This means following employees during the same period and measuring the same constructs. However, given that we conducted a secondary analysis of a publicly available dataset, we could not mitigate this design limitation statistically. Yet, as Monzani et al. (2021a) discuss in their limitations section, the study's field experimental nature prevented these authors from implanting all the controls that would have been available in a laboratory setting (Podsakoff and Podsakoff, 2019). We call for future research that replicates our study to explore if our results generalize to other settings. For example, future research could attempt to replicate ours in larger corporations, with more formalized structures and more complex interpersonal dynamics. Another issue is that most participants were women, the predominant anatomical sex of healthcare professionals in the country where our study was conducted (i.e., Spain). Further, it would be beneficial to utilize interventions with more sessions, a diverse range of activities, and longitudinal (enduring) effects.

Third, the primary study's sample derives from a firm in the healthcare sector and thus, other professions, occupations, or trades were not included, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Similarly, our sample size was lower than if the study was conducted employing primary data. Monzani et al. (2021a) argue that data collection was limited due to situational constraints that impeded further data collection efforts (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic).

In this regard, an anonymous reviewer argued that the statistical power of this sample is insufficient to detect small effect sizes (e.g., Pearson's correlation or standardized regression coefficients) and thus we cannot adequately reject Hypothesis 1. In other words, we do not know whether there were no overall differences in employee happiness across experimental conditions after the program ended (at Time 8), or if we could not detect it due to lack of statistical power (i.e., a Type II error). That being said, it is also true that while simple correlations provide an initial understanding of the relationships between variables, more advanced techniques like multivariate hierarchical regression can uncover deeper insights, especially when interactions or covariates are considered. Additionally, multivariate analyses often reveal meaningful relationships that may not appear in bivariate correlations due to their ability to account for the shared variance among predictors (Cohen, 1988, 1992).

Therefore, we attempted to mitigate this concern by employing multivariate hierarchical regression, given that it allows to control for confounding variables and explore potential interaction effects that may not be evident in a correlation. This is particularly important in intervention studies where complex relationships exist. Moderation models can provide the utility needed to detect these interactions, while allowing us to understand the nuanced effects of interventions, even when initial correlations are weak or non-significant (Hayes, 2022). As seen in Table 3, post-hoc power analyses revealed that our multivariate regression model did have enough statistical power to detect small effect sizes and provided further information that allowed us to reject Hypothesis 1 with some degree of confidence of not making a Type II error.

Despite these limitations, we anticipate that extended mindfulness and character development programs could potentially stimulate a higher impact on the variables explored in this study, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of the intervention. Implementing a new follow-up evaluation system to assess the sustained effects for several months after the intervention would be beneficial to determine the persistence and long-term efficacy (Seligman et al., 2005). Similarly, future studies should explore whether the MBI program (Mindfulness alone) experiences quicker decay over time compared with the MBSI program (Mindfulness and character strengths).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Board - University of Barcelona. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AR: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SB: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JE: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the insightful and useful comments of two reviewers, whose comments were extremely helpful to improve the quality of our paper. Lucas Monzani and Sonja Bruschetto would like to dedicate this article to their dogs, Logan and Reggie, who were caring and supporting companions during this manuscript's writing and review processes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bates-Krakoff, J., Parente, A., McGrath, R., Rashid, T., and Niemiec, R. M. (2022). Are character strength-based positive interventions effective for eliciting positive behavioral outcomes? A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Wellbeing 12, 56–80. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v12i3.2111

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2004). Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. 11, 230–241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., and Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol. Inq. 18, 211–237. doi: 10.1080/10478400701598298

Buunk, A. P., Zurriaga, R., and Peíro, J. M. (2010). Social comparison as a predictor of changes in burnout among nurses. Anxiety Stress Coping 23, 181–194. doi: 10.1080/10615800902971521

Carlson, S. M., Koenig, M. A., and Harms, M. B. (2013). Theory of mind. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 4, 391–402. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1232

Chérif, L., Wood, V. M., and Watier, C. (2021). Testing the effectiveness of a strengths-based intervention targeting all 24 strengths: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Rep. 124, 1174–1183. doi: 10.1177/0033294120937441

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences., 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Crossan, M. M., Mazutis, D., and Seijts, G. (2013). In search of virtue: the role of virtues, values and character strengths in ethical decision making. J. Bus. Ethics 113, 567–581. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1680-8

Dawson, J. F. (2013). Moderation in management research: what, why, when, and how. J. Bus. Psychol. 29, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2008). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and wellbeing: an introduction. J. Happiness Stud. 9, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1

Díaz, D., Rodríguez-Carvajal, R., Blanco, A., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Gallardo, I., Valle, C., et al. (2006). Spanish adaptation of the psychological wellbeing scales (PWBS). Psicothema 18, 572–577.

DiMaria, C. H., Peroni, C., and Sarracino, F. (2020). Happiness matters: productivity gains from subjective wellbeing. J. Happiness Stud. 21, 139–160. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00074-1

Dogan, T., Totan, T., and Sapmaz, F. (2013). Role Self-esteem, psychological wellbeing, emotional self-efficacy, affect balance happiness: path model. Eur. Sci. J. 9, 31–42.

Donaldson, S. I., and Ko, I. (2010). Positive organizational psychology, behavior, and scholarship: a review of the emerging literature and evidence base. J. Posit. Psychol. 5, 177–191. doi: 10.1080/17439761003790930

Donaldson, S. I., Lee, J. Y., and Donaldson, S. I. (2019). Evaluating positive psychology interventions at work: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 4, 113–134. doi: 10.1007/s41042-019-00021-8

Ellis, C. L., Monzani, L., and Bruschetto, S. (2024). Character development and mindfulness. Amplify 37, 8–14.

Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., Mcgrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., et al. (2002). Towards standardized brief outcome measure: psychometric properties utility theCORE-OM. Br. J. Psychiat. 180, 51–60. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.1.51

Feixas, G., Evans, C., Trujillo, Saúl, L., Botella, L., Corbella, S., et al. (2012). La version española del CORE-OM: Clinical outcomes routine evaluation-outcome measure. Revista de Psicoterapia 89:641. doi: 10.33898/rdp.v23i89.641

Freidlin, P., Littman-Ovadia, H., and Niemiec, R. M. (2017). Positive psychopathology: social anxiety via character strengths underuse and overuse. Pers. Individ. Diff. 108, 50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.003

Garg, N. (2017). Workplace spirituality and employee wellbeing: an empirical exploration. J. Hum. Values 23, 129–147. doi: 10.1177/0971685816689741

Garg, N., Mahipalan, M., Poulose, S., and Burgess, J. (2022). Does gratitude ensure workplace happiness among university teachers? Examining the role of social and psychological capital and spiritual climate. Front. Psychol. 13:849412. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.849412

Germer, C., and Neff, K. (2019). Mindful self-compassion (MSC). Handbook mindfulness-based programmes: Routledge. 357–367. doi: 10.4324/9781315265438-28

Good, D. J., Lyddy, C. J., Glomb, T. M., Bono, J. E., Brown, K. W., Duffy, M. K., et al. (2016). Contemplating mindfulness at work. J. Manage. 42, 114–142. doi: 10.1177/0149206315617003

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Publications. Available at: https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=MglQEAAAQBAJ (accessed October 5, 2024).

Hesser, H., Weise, C., Westin, V. Z., and Andersson, G. (2011). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive-behavioral therapy for tinnitus distress. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.006

Horowitz, J. M., and Parker, K. (2023). “How Americans view their jobs,” in Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/03/30/how-americans-view-their-jobs/ (accessed January 2, 2024).

Huta, V., and Ryan, R. M. (2010). Pursuing pleasure or virtue: the differential and overlapping wellbeing benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. J. Happiness Stud. 11, 735–762. doi: 10.1007/s10902-009-9171-4

Huta, V., and Waterman, A. S. (2014). Eudaimonia and its distinction from hedonia: developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. J. Happiness Stud. 15, 1425–1456. doi: 10.1007/s10902-013-9485-0

Ivtzan, I., Gardner, H. E., and Smailova, Z. (2011). Mindfulness meditation and curiosity: The contributing factors to wellbeing and the process of closing the self-discrepancy gap. Int. J. Wellbeing 1, 316–327. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v1i3.2

Jebb, A. T., Morrison, M., Tay, L., and Diener, E. (2020). Subjective wellbeing around the world: Trends and predictors across the life span. Psychol. Sci. 31, 293–305. doi: 10.1177/0956797619898826

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., and Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 127, 376–407. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.376

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 4, 33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Constructivism in the Human Sci. 8, 73–107.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., and Schwarz, N. (1999). Wellbeing: Foundations hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Rubenstein, A. L., and Barnes, T. S. (2024). The role of attitudes in work behavior. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 11:1333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-101022-101333

La Guardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: a self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and wellbeing. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 367–384. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.3.367

Lambert, N. M., Gwinn, A. M., Fincham, F. D., and Stillman, T. F. (2011). Feeling tired? How sharing positive experiences can boost vitality. Int. J. Wellbeing 1, 307–314. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v1i3.1

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., and Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Modeling 9, 151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1

Lottman, T. J., Zawaly, S., and Niemiec, R. (2017). “Well-being and well-doing: Bringing mindfulness and character strengths to the early childhood classroom and home,” in Positive Psychology Interventions in Practice, ed. C. Proctor (Springer International Publishing), 83–105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-51787-2_6

Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). The How of Happiness: A Practical Guide to Getting the Life you Want. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Lyubomirsky, S., Dickerhoof, R., Boehm, J. K., and Sheldon, K. M. (2011). Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: an experimental longitudinal intervention to boost wellbeing. Emotion 11, 391–402. doi: 10.1037/a0022575

Lyubomirsky, S., and Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 46, 137–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1006824100041

Milligan, S. (2017). Employers Take Wellness to a Higher Level. Available at: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0917/pages/employers-take-wellness-to-a-higher-level.aspx (accessed January 2, 2024).

Monzani, L., Escartín, J., Ceja, L., and Bakker, A. B. (2021a). Blending mindfulness practices and character strengths increases employee well-being: a second-order meta-analysis and a follow-up field experiment. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 31, 1025–1062. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12360

Monzani, L., Seijts, G. H., and Crossan, M. M. (2021b). Character matters: The network structure of leader character and its relation to follower positive outcomes. PLoS ONE. 16:e0255940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255940

Monzani, L., and Van Dick, R. (2020). Positive Leadership in Organizations. Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology.

Niemiec, R. M. (2012). Mindful living: Character strengths interventions as pathways for the five mindfulness trainings. Int. J. Wellbeing 2, 22–33. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v2i1.2

Niemiec, R. M. (2014). Mindfulness and Character Strengths: A Practical Guide to Flourishing. Toronto, ON: Hogrefe Publishing.

Niemiec, R. M. (2018). Character Strengths Interventions: A Field Guide for Practitioners. Toronto, ON: Hogrefe Publishing.

Niemiec, R. M. (2022). Pathways to peace: character strengths for personal, relational, intragroup, and intergroup peace. J. Posit. Psychol. 17, 219–232. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2021.2016909

Niemiec, R. M., and Lissing, J. (2016). “Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice (MBSP) for Enhancing Wellbeing, Managing Problems, and Boosting Positive Relationships,” in Mindfulness in Positive Psychology: The Science of Meditation and Wellbeing, eds. I. Ivtzan and T. Lomas (London: Routledge), 15–36.

Peiró, J. M., Kozusznik, M. W., Rodríguez-Molina, I., and Tordera, N. (2019). The happy-productive worker model and beyond: patterns of wellbeing and performance at work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16030479

Peterson, C., and Park, N. (2006). Character strengths in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 1149–1154. doi: 10.1002/job.398

Peterson, C., Park, N., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: the full life versus the empty life. J. Happiness Stud. 6, 25–41. doi: 10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Podsakoff, P. M., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2019). Experimental designs in management and leadership research: strengths, limitations, and recommendations for improving publishability. Leadersh. Q. 30, 11–33. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.11.002

Raibley, J. R. (2012). Happiness is not Wellbeing. J. Happiness Stud. 13, 1105–1129. doi: 10.1007/s10902-011-9309-z

Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., and Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 102, 112–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Ryff, C. D., and Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological wellbeing revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69, 719–727. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

Schutte, N. S., and Malouff, J. M. (2019). The impact of signature character strengths interventions: a meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 20, 1179–1196. doi: 10.1007/s10902-018-9990-2

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., and Teasdale, J. D. (2018). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression, Second Edition: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Publications. Available at: https://books.google.com/books/about/Mindfulness_Based_Cognitive_Therapy_for.html?id=QHRVDwAAQBAJ (accessed January 10, 2024).

Seijts, G. H., Monzani, L., Woodley, H. J. R., and Mohan, G. (2022). The effects of character on the perceived stressfulness of life events and subjective wellbeing of undergraduate business students. J. Manage. Educ. 46, 106–139. doi: 10.1177/1052562920980108

Seligman, M., and Peterson, C. (2004). Character Strengths Virtues: Handbook Classification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., and Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 60, 410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

Spector, P. E. (1985). Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: development of the Job Satisfaction Survey. Am. J. Community Psychol. 13, 693–713. doi: 10.1007/BF00929796

Thorndike, E. L. (1904). An Introduction to the Theory of Mental and Social Measurements. New York, New York, USA: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Van den Broeck, A., Vansteenkiste, M., De Witte, H., Soenens, B., and Lens, W. (2010). Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: Construction and initial validation of the Work-Related Basic Need Satisfaction Scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 83, 981–1002. doi: 10.1348/096317909X481382

Waterman, A. S. (2007). On the importance of distinguishing hedonia and eudaimonia when contemplating the hedonic treadmill. Am. Psychol. 62, 612–613. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X62.6.612

Waterman, A. S. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: a eudaimonist's perspective. J. Posit. Psychol. 3, 234–252. doi: 10.1080/17439760802303002

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., and Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Kashdan, T. B., and Hurling, R. (2011). Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in wellbeing over time: a longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Pers. Individ. Dif. 50, 15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.004

Wright, T. A., Cropanzano, R., and Bonett, D. G. (2007). The moderating role of employee positive well being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 12, 93–104. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.2.93

Wright, T. A., and Huang, C.-C. (2008). Character in organizational research: past directions and future prospects. J. Organ. Behav. 29, 981–987. doi: 10.1002/job.521

Keywords: mindfulness, character, happiness, wellbeing, field experiment

Citation: Monzani L, Ruiz Pardo A, Bruschetto S, Ellis C and Escartin J (2024) Mindfulness, character, and workplace happiness: the moderating role of baseline levels of employee wellbeing. Front. Organ. Psychol. 2:1397143. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2024.1397143

Received: 06 March 2024; Accepted: 25 October 2024;

Published: 18 November 2024.

Edited by:

Sajad Rezaei, University of Worcester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Silvia Cristina da Costa Dutra, University of Zaragoza, SpainNaval Garg, Delhi Technological University, India

Copyright © 2024 Monzani, Ruiz Pardo, Bruschetto, Ellis and Escartin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lucas Monzani, bG1vbnphbmlAaXZleS5jYQ==

Lucas Monzani

Lucas Monzani Ana Ruiz Pardo

Ana Ruiz Pardo Sonja Bruschetto

Sonja Bruschetto Cassandra Ellis

Cassandra Ellis Jordi Escartin2,3

Jordi Escartin2,3