95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Organ. Psychol. , 03 May 2024

Sec. Performance and Development

Volume 2 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/forgp.2024.1353959

The purpose of this study is to empirically establish which effects the facets of servant leadership have on the facets of commitment to supervisor and which effect the facets of commitment to supervisor have on the facets of organizational commitment. To this end, we conducted a survey with 1,756 participants, who roughly represent the German workforce by gender and age, to measure organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership. To test the relationship between the facets of the examined constructs, we analyzed our data using partial least squares path modeling. Our results indicate that commitment to supervisor serves as a relevant, but not the only, antecedent of organizational commitment. Furthermore, our results indicate that affective and normative commitment to supervisor is relatively strongly affected by the servant leadership facets empowerment and stewardship, relatively moderately by forgiveness, authenticity and humility, and relatively weakly by standing back and accountability. Organizations are advised to prioritize the afore-mentioned facets of servant leadership in a corresponding order when selecting and developing managers as servant leaders. The results and findings of our study provide rather comprehensive insights in the complex relationships of organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership, which can serve as a basis for further research and assist the managerial practice.

Organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership gain popularity and relevance in both, the managerial practice and academia. Our research aims to empirically establish the relationship between the facets of these constructs. More precisely, we examine which effect the facets of servant leadership have on the facets of commitment to supervisor and which effect the facets of commitment to supervisor have on the facets of organizational commitment. To this end, we will introduce organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership and hypothesize their relationships, i.e., the hypothesized effects of servant leadership on commitment to supervisor and the hypothesized effects of commitment to supervisor to organizational commitment, in the following three subsections. On this basis, we will present our hypothesized model and the research questions in the fourth subsection of the introduction.

The labor markets of advanced economies have changed over the recent years. Against the backdrop of advancements in technology, shortages of qualified personnel and, therewith, an intensified competition for talents, many employers changed their perspective from mainly focussing on recruiting new employees to also emphasizing the retention and subsequent development of the employees with the highest performance potential (Claus, 2019). An organization's objective of retaining employees means that the employees intend to stay with their employer and actually do so. This intention to stay with an employer is determined by organizational commitment (e.g., Jenkins and Paul Thomlinson, 1992; Yang, 2008; Guzeller and Celiker, 2020), which can be understood as an employee's psychological attachment to an organization (Porter et al., 1974).

The effects of organizational commitment, however, are not limited to the intention to stay with an employer. Positives outcomes of high levels of (affective and normative) organizational commitment can be higher levels of work attendance, performance and organizational citizenship behavior (Meyer et al., 2002), amongst others. These effects underscore the relevance of organizational commitment for companies, which is also supported by the growing number of academic publications examining organizational commitment over the recent two decades.

There is a relatively long tradition in understanding organizational commitment as a multi-dimensional construct. Mowday et al. (1982) regard accepting the organization's goals and values, putting in extra-effort for the organization, and motivation to remain with the organization as dimensions of organizational commitment. O'Reilly and Chatman (1986) conceptualize organizational commitment on the dimensions of compliance, identification and internalization.

Arguably, the nowadays most widely used and accepted model of organizational commitment is the Three-Component Model by Meyer and Allen's (1991, 1997), which distinguishes between affective, continuance and normative commitment. Even though empirical support for the three-dimensional structure can be found (Meyer et al., 2002), criticism regarding conceptual and empirical inconsistencies arose (Solinger et al., 2008). Thus, Solinger et al. (2008) suggest that organizational commitment should be more firmly rooted in the “classic” theory of attitudes (e.g., Rosenberg and Hovland, 1960) and especially in Eagly and Chaiken's (1993) Composite Attitude-Behavior Model, which shows similarities to the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980) and its advancement, the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1985, 1988, 1991). Against this backdrop, Gansser and Godbersen (2023) proposed the Four-Component Model of Organizational Commitment with the aim to integrate Meyer and Allen's (1991, 1997) Three-Component Model with an attitudinal approach, suggested by Solinger et al. (2008). The Four-Component Model of Organizational Commitment, which could be empirically confirmed in several studies (Gansser and Godbersen, 2017; Godbersen and Scharpf, 2021; Godbersen et al., 2021, 2022), consists of the following dimensions or facets:

• The affective facet of organizational commitment represents an emotional attachment to and identification with an employer. Affective organizational commitment can be understood as “want to stay.” This facet corresponds with the affective component of the Three-Component Model (Meyer and Allen, 1991, 1997) and the attitude toward the target of the Composite Attitude-Behavior Model (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993). Furthermore, it roughly resembles the attitude of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1985, 1988, 1991).

• The cognitive facet of organizational commitment represents a rather rational bond, in the sense that the employee has to stay with his or her employer because he or she does not see better and easily accessible alternatives. Cognitive organizational commitment can be understood as “have to stay.” This facet corresponds with the continuance component of the Three-Component Model (Meyer and Allen, 1991, 1997) and the utilitarian outcomes of the Composite Attitude-Behavior Model (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993). Furthermore, it roughly resembles the perceived behavioral control of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1985, 1988, 1991).

• The normative facet of organizational commitment represents a felt moral obligation to an employer based on personal values and thoughts of reciprocal considerations. Normative organizational commitment can be understood as “should stay.” This facet corresponds with the normative component of the Three-Component Model (Meyer and Allen, 1991, 1997) and the normative outcomes and self-identity outcomes of the Composite Attitude-Behavior Model (Eagly and Chaiken, 1993). Furthermore, it roughly resembles the subjective norm of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1985, 1988, 1991).

• The contractual facet of organizational commitment represents the formal dependence on an employer because of a contract.

Virtually every aspect of working conditions and human resource practices can have an effect on organizational commitment, as a meta-analysis of Kooij et al. (2010) demonstrates. Amongst others, job enrichment (Putri and Setianan, 2019), working time (Godbersen et al., 2022), organizational climate (McMurray et al., 2004) and organizational support (Rhoades et al., 2001) can be seen as antecedents of organizational commitment.

We pointed out that the entire context and every aspect of work situations can affect organizational commitment in the previous section. However, we would like to highlight the crucial role of the supervisor's behavior and leadership style for organizational commitment, as he or she is often perceived as a representative of the organization by its employees (Levinson, 1965; Eisenberger et al., 1986). In this context, the relevance of the leadership style for organizational commitment could be empirical confirmed, as the meta-analysis of Jackson et al. (2013) shows. Thus, it appears plausible to assume that not only the supervisor's leadership style and behavior affect organizational commitment but also commitment to supervisor itself can be seen as an antecedent of organizational commitment.

The necessary condition for this assumption is the differentiation between organizational commitment and commitment to supervisor, which is in line with the understanding of employees having different foci of commitment beyond just the organization (Reichers, 1985; Meyer et al., 1993), e.g., work groups, management or supervisors (Becker, 1992; Clugston et al., 2000; Stinglhamber and Vandenberghe, 2003; Vandenberghe et al., 2004; Pohl and Paillé, 2011). Such a differentiated perspective on commitment is supported by findings that the antecedents, consequences and correlates differ between the foci of commitment (Becker, 1992; Becker and Kernan, 2003; Cheng et al., 2003; Redman and Snape, 2005; Riketta and Van Dick, 2005; Pohl and Paillé, 2011). This means that, even though a supervisor is perceived as a representative of an organization, he or she is still a different entity, which can be the target of its own commitment (Stinglhamber and Vandenberghe, 2003; Landry et al., 2010).

The sufficient condition for the assumption that commitment to supervisor is an antecedent of organizational commitment can be found from two perspectives, the perspective of an organization and the perspective of employees. From an organization's perspective, the overall objective is organizational commitment, as an employee should productively and sustainably engage with the organization. Thus, commitment to supervisor should be understood as the antecedent of organizational commitment. From the perspective of an employee, the theorisation of commitment by Becker et al. (1996) also supports the notion that commitment to supervisor precedes organizational commitment. Based on Lewin's (1943) field theory, they argue that a local focus of commitment, e.g., commitment to supervisor, is psychologically more proximal and has, therefore, more immediate and stronger effects on an employee than a global focus like organizational commitment.

On an empirical level, Vandenberghe et al. (2004) determine that commitment to supervisor affects organizational commitment. Further empirical support for this assumption stems from several studies documenting the effects of commitment to supervisor on outcomes related to organizational commitment, such as turnover intentions and turnover (Vandenberghe and Bentein, 2010; Huyghebaert et al., 2019), innovative work behavior, seeking feedback for self-improvement and error reporting (Chughtai, 2013) and work creativity (Imam et al., 2020).

Whilst commitment to supervisor is conceptualized and operationalised as a one-dimensional construct (i.e., affective commitment to supervisor) in most of the afore-mentioned studies, the studies of Becker and Kernan (2003) and Landry et al. (2010) support the idea of multiple dimensions of commitment to supervisor, as these dimensions lead to different outcomes. Such a multi-dimensional conceptualization allows a more comprehensive and differentiated understanding of commitment to supervisor and should be consistent with the conceptualization of organizational commitment. In this context, Landry et al. (2010), who used the Three-Component Model (Meyer and Allen, 1991, 1997) as a starting point, could validate the same dimensions for commitment to supervisor as for organizational commitment, i.e., the affective, normative and continuance component, with the latter component divided into two sub-dimensions. We outlined the criticism of the Three-Component Model (Meyer and Allen, 1991, 1997) in Section 1.1 and proposed the use of its advancement, the Four-Component Model of Organizational Commitment (Gansser and Godbersen, 2023), which follows a slightly different dimensionality. Against this backdrop, we follow the dimensions of the Four-Component Model for conceptualizing commitment to supervisor: affective, cognitive, normative and contractual commitment to supervisor.

Apart from rather general constructs like culture (Clugston et al., 2000), several antecedents of commitment to supervisor are determined that are more closely linked to the supervisor and his or her behavior, such as affective employee-supervisor relationship and professional respect (Vandenberghe et al., 2004), and supervisor support (Stinglhamber and Vandenberghe, 2003). Furthermore, the leadership style in general (Polston-Murdoch, 2013) and specific leadership styles, like authentic leadership (Emuwa, 2013; Imam et al., 2020) and servant leadership (Sokoll, 2014), could be linked to commitment to supervisor.

Against this backdrop, it needs to be determined which supervisor's behavior is crucial for commitment to supervisor. The leadership style springs to mind, as it reflects the overall and normally long-term behavior of a supervisor. We propose servant leadership as an antecedent of commitment to supervisor, as servant leadership incorporates societal, organization-oriented, employee-focused and moral aspects more than other leadership styles, like transformational, authentic and spiritual leadership (Sendjaya et al., 2008). This rather holistic view is argumentatively substantiated by looking at the outcomes for organizations and their employees (Liden et al., 2008; van Dierendonck and Nuijten, 2011) and empirically supported by meta-analyses conducted by Hoch et al. (2018) and Eva et al. (2019).

In this context, the core characterization of a servant leader as “the servant-leader is a servant first” (Greenleaf, 1977, p. 7) might appear self-explanatory and potentially superficial. However, it emphasizes the focus of a servant leader, which is not on himself or herself but on the advancement of a society or larger community, an organization and its members (Gutierrez-Broncano et al., 2024). Advancing a society, an organization and its members can be achieved on multiple dimensions. Accordingly, servant leadership was conceptualized and operationalised on several dimensions (Laub, 1999; Dennis and Bocarnea, 2005; Barbuto and Wheeler, 2006; Wong and Davey, 2007; Liden et al., 2008; Sendjaya et al., 2008; Reed et al., 2011).

Based on an extensive literature review, theoretical consideration and empirical refinement, van Dierendonck and Nuijten (2011) developed and confirmed eight facets of servant leadership (also cf. Verdorfer and Peus, 2014), which we will follow henceforth:

• Empowerment refers to enabling and encouraging the personal development, autonomous performances and decision-making of followers.

• Standing back refers to shifting the focus from the leader to the followers when it comes to taking credits for successes.

• Accountability refers to giving followers responsibility for their decisions and actions and holding them accountable for their performances.

• Forgiveness refers to forgiving mistakes and wrong-doings of followers.

• Courage refers to taking risks and facing challenges based on values and beliefs.

• Authenticity refers to the leader expressing his or her true emotions, motivations and values.

• Humility refers to the ability of the leader to accept his or her short-comings or failures and his or her willingness to overcome these with the help of others.

• Stewardship refers to taking responsibility and focussing on a long-term vision and the common good.

We introduced four facets of organizational commitment, i.e., affective, cognitive, normative and contractual organizational commitment, in Section 1.1. In Section 1.2, we conceptualized the same facets for commitment to supervisor and hypothesized them as antecedents of the facets of organizational commitment. In Section 1.3, we argued that the eight facets of servant leadership, i.e., empowerment, standing back, accountability, forgiveness, courage, authenticity, humility and stewardship, should be seen as determinants of the facets of commitment to supervisor. This hypothesized model is represented in Figure 1. Correspondingly, our empirical research follows two research questions:

• RQ1: Which effect do the facets of commitment to supervisor have on the facets of organizational commitment?

• RQ2: Which effect do the facets of servant leadership have on the facets of commitment to supervisor?

Figure 1. Hypothesized model representing the effects of the facets of servant leadership (left) on the facets of commitment to supervisor (center) and the effects of the facets of commitment to supervisor (center) on the facets of organizational commitment (right) (own representation).

The research design and measurement instruments are presented in the following two subsections.

An online questionnaire was used to collect the data between 01 September and 31 October 2023. Students of FOM University of Applied Sciences from the study centers Munich and Stuttgart recruited the participants by using a predefined quota, which is based on the employed population in Germany by gender and age groups (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2023).

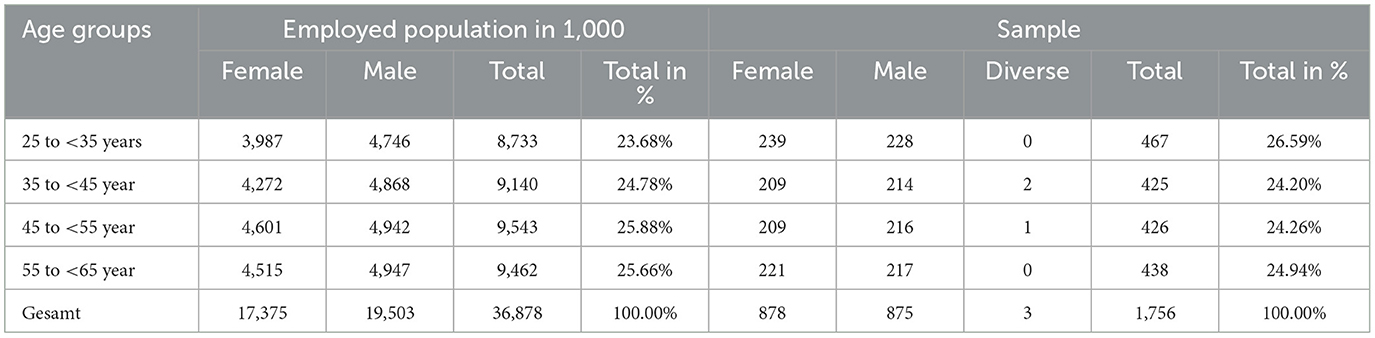

The sample consists of 1,756 fully answered questionnaires. The youngest participant is 25 years of age and the oldest 64 years of age. The average age is 43.49 years (SD = 11.97). 50.00% of the sample are female, 49.83% male and 0.17% diverse. The distribution of gender and age groups within the sample roughly matches the respective distribution of the employed population in Germany, as can be seen in Table 1. This indicates a high level of representativity. However, it should be noted that the data was only collected in the areas of Munich and Stuttgart which means that the southern regions of Germany are predominantly represented in the sample.

Table 1. Employed population in Germany by gender and age groups (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2023) and sample by gender and age groups (n = 1,756).

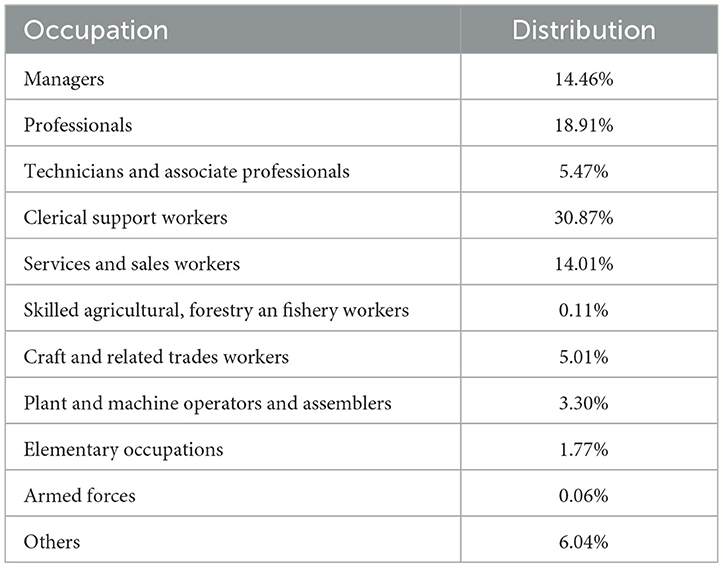

Full-time employed participants are represented in the sample at 78.76%, whilst 21.24% of the participants are part-time employed. Of the participants, 26.42% hold personnel responsibility and 73.58% do not hold personnel responsibility. The occupations of the participants, based on the classification by the International Labour Organization (2012), are represented in Table 2. 11.22% of the participants are with their employer less than a year, 29.61% 1–5 years, 17.65% 6–10 years and 41.51% more than 10 years. The company size by employees is represented in the sample as follows: < 10 employees: 6.04%; 10–49 employees: 15.77%; 50–249 employees: 15.55%; 250 or more employees: 62.64%.

Table 2. Occupation of the participants, based on the classification by the International Labour Organization (2012) (n = 1,756).

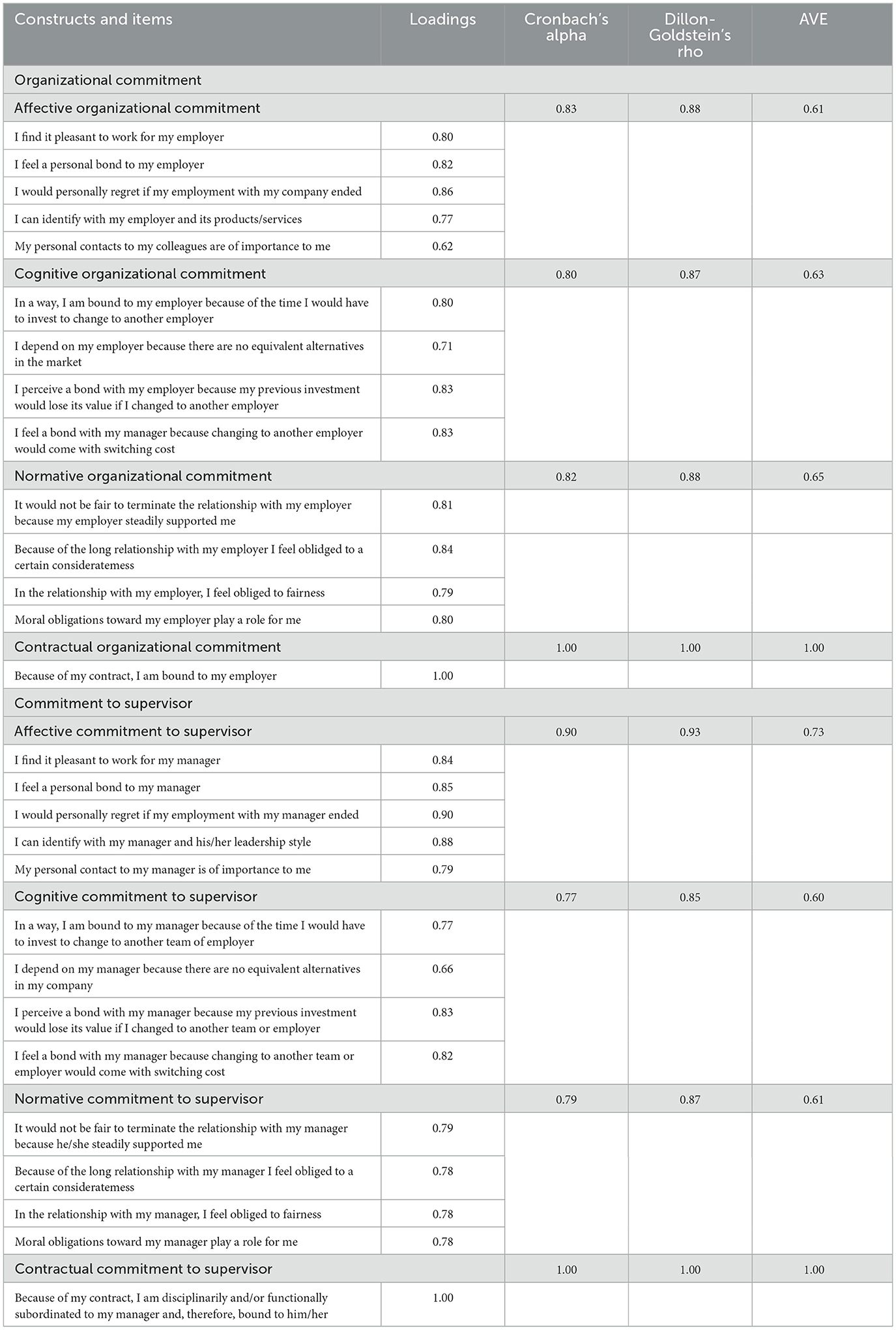

Our hypothesized model, which we introduced in Section 1.4, serves as the theoretical basis of our measurement. We measured the four facets of organizational commitment with the Four-Component Model of Organizational Commitment (Gansser and Godbersen, 2023), which consists of 14 items. To measure the affective, cognitive, normative and contractual facets of commitment to supervisor, we also used the Four-Component Model of Organizational Commitment (Gansser and Godbersen, 2023), but reformulated the items so that they refer to the supervisor rather than the organization. The items of our operationalisation of organizational commitment and commitment to leader are represented in Table 3; the German items used in our questionnaire can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 3. Constructs and items of organizational commitment and commitment to supervisor with loadings, Cronbach's alpha, Dillon-Goldstein's rho and average variance extracted (AVE) (n = 1,756).

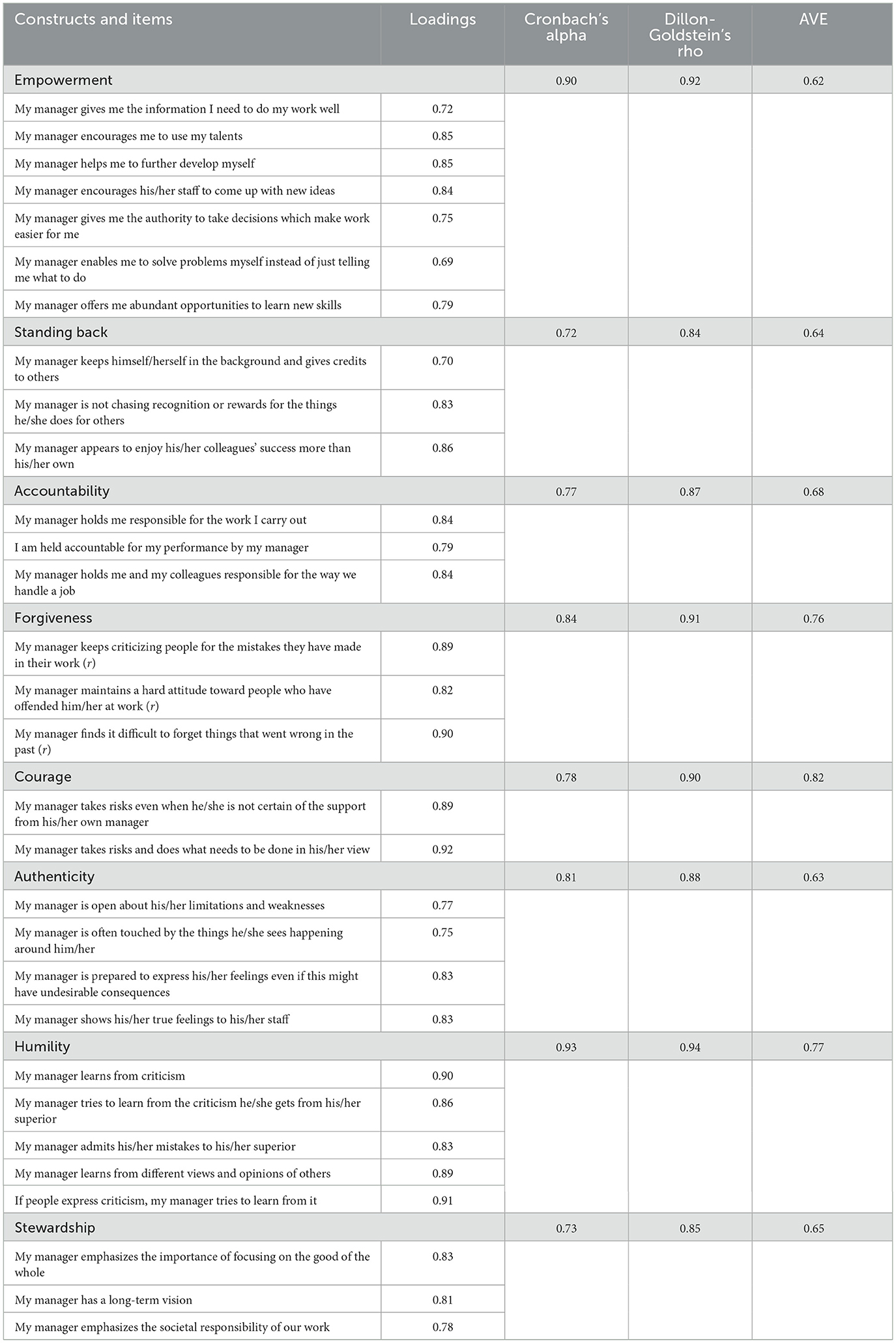

Our measurement of the eight facets of servant leadership is based on the German version of the Servant Leadership Survey (Verdorfer and Peus, 2014), which is based on the Servant Leadership Survey by van Dierendonck and Nuijten (2011). The Servant Leadership Survey consists of 30 items, which are represented in Table 4. The German items we applied in our survey can be found in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 4. Constructs and items of servant leadership with loadings, Cronbach's alpha, Dillon-Goldstein's rho and average variance extracted (AVE; n = 1,756).

The items of all of the constructs, i.e., facets of organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership, were measured on six-step scales from 1 “do not agree at all” (German: “stimme überhaupt nicht zu”) to 6 “agree in full” (German: “stimme voll und ganz zu”). The analysis of our data was conducted with R (R Core Team, 2017). Partial least squares path modeling with the R-package plspm (Sanchez, 2013) forms the core of our analysis.

We determined the loadings of the items and Cronbach's alpha, Dillon-Goldstein's rho and average variance extracted for the examined constructs to test the adequacy of our measurement instruments. The respective results for organizational commitment and commitment to supervisor are represented in Table 3. All of the items load on their respective constructs above 0.60. The lowest value for Cronbach's alpha is 0.77, for Dillon-Goldstein's rho 0.85 and for average variance extracted 0.61. These results indicate a good adequacy of our measurement of the organizational commitment and commitment to supervisor facets.

The item loadings and Cronbach's alpha, Dillon-Goldstein's rho and average variance extracted for the constructs of servant leadership are represented in Table 4. All of the items load on their respective constructs above 0.60. The lowest value for Cronbach's alpha is 0.72, for Dillon-Goldstein's rho 0.84 and for average variance extracted 0.63. These results indicate a good adequacy of our measurement of the servant leadership facets.

The following subsections contain the descriptive statistics, the results for the effects of commitment to supervisor on organizational commitment and the results for the effects of servant leadership on commitment to supervisor.

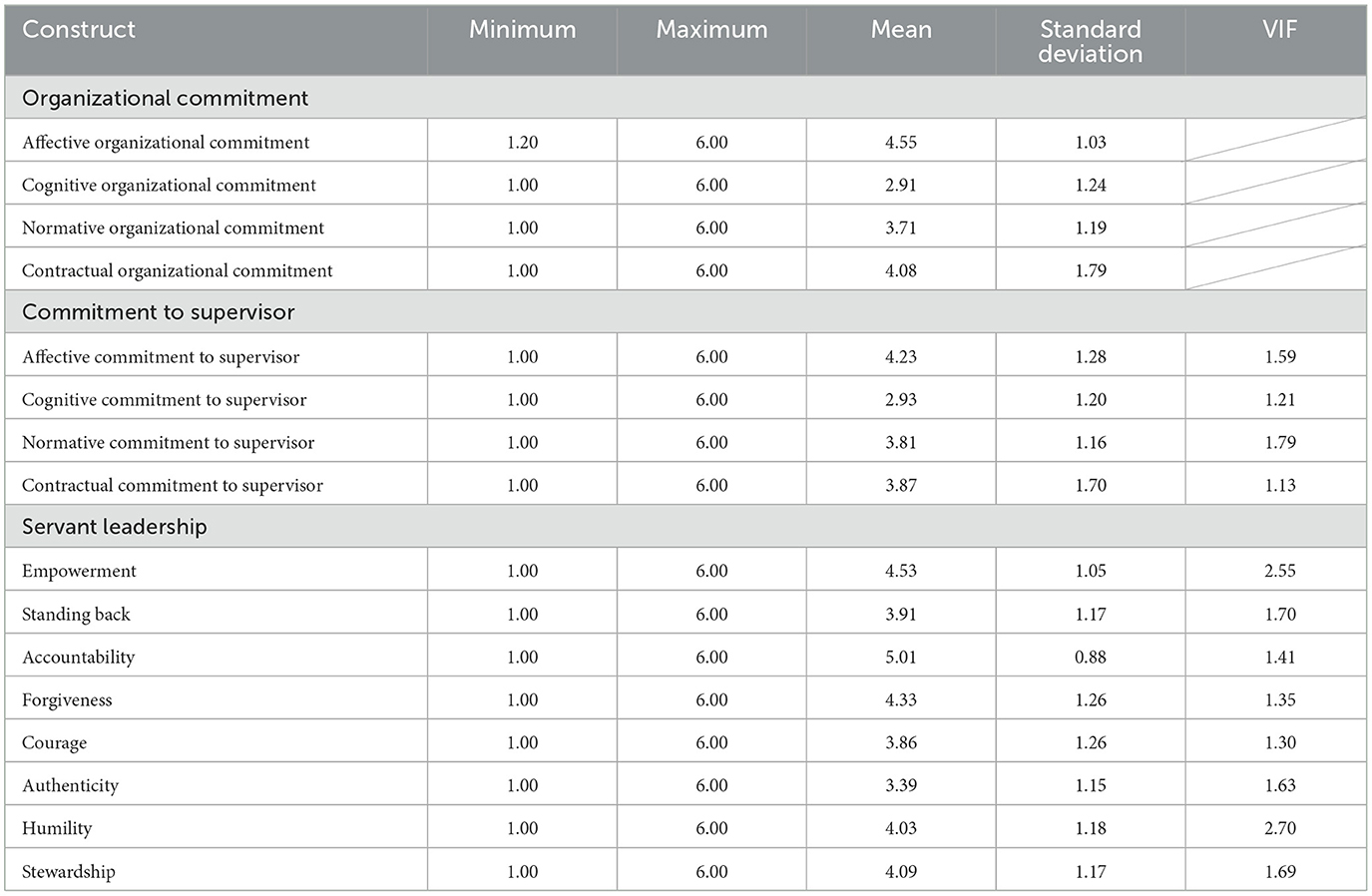

The descriptive statistics of the examined constructs are represented in Table 5. The facets of organizational commitment and commitment to supervisor show a similar pattern. Affective commitment has the highest values. The values of normative and contractual commitment are on a lower level but still above the calculatory middle of the scale of 3.50, whilst cognitive commitment shows values below the middle of the scale. With the exception of authenticity, all of the facets of servant leadership score higher than 3.50, the calculatory middle of the scale. We also tested the independent variables (facets of commitment to supervisor and facets of servant leadership) for multicollinearity by calculating variance inflation factors (VIF) using the R package faraway (Faraway, 2022). The variance inflation factors with values ranging from 1.13 to 2.70 indicate that effects of multicollinearity can be neglected.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of the facets of organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership (n = 1,756).

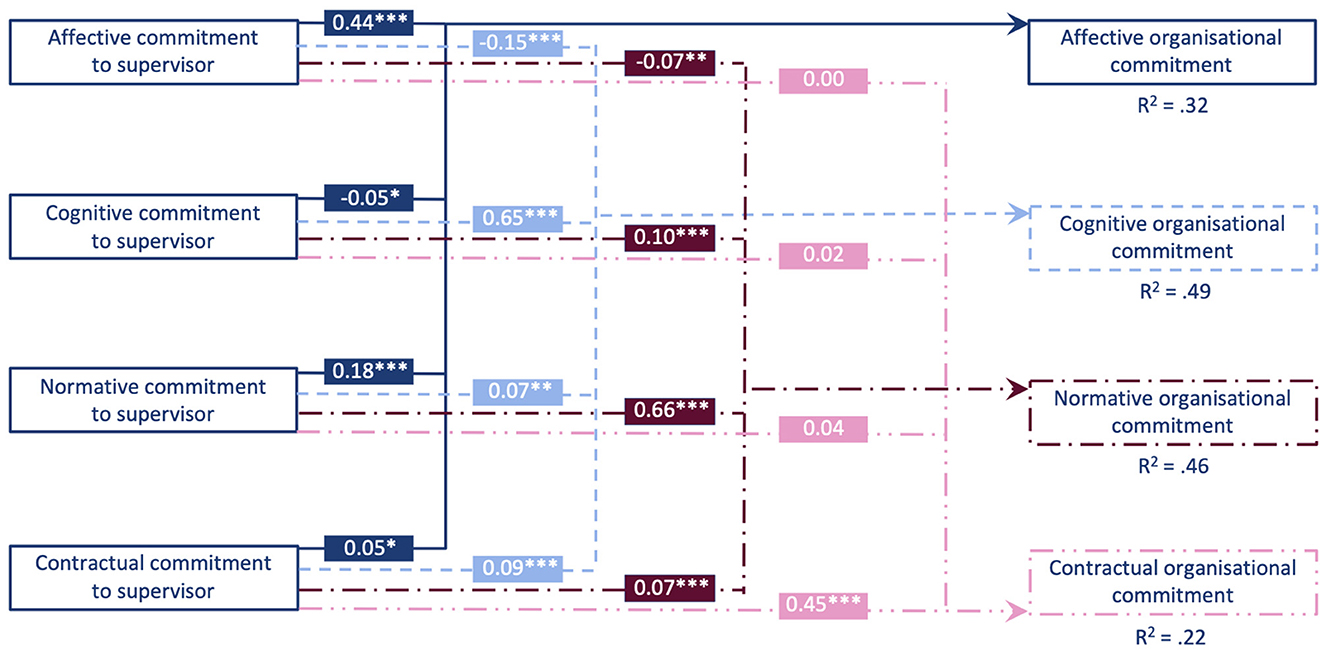

The effects of the facets of commitment to supervisor on the facets of organizational commitment are represented in Figure 2, including path coefficients, significance levels and R2 for the dependent variables. R2 ranges from 0.22 to 0.49, with cognitive organizational commitment (R2 = 0.49) showing the highest value, followed by normative organizational commitment (R2 = 0.46), affective organizational commitment (R2 = 0.32) and contractual organizational commitment (R2 = 0.22).

Figure 2. Effects of the facets of commitment to supervisor on the facets of organizational commitment (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n = 1,756).

For each facet of organizational commitment, the highest path coefficient with a p-value smaller than 0.001 stems from its corresponding facet of commitment to supervisor, e.g., affective commitment to supervisor has the highest impact on affective organizational commitment compared with the other facets of commitment to supervisor.

Apart from the relationships of the corresponding commitment facets, affective organizational commitment is negatively affected by cognitive commitment to supervisor on a relatively weak level, positively affected by normative commitment on a relatively moderate level and positively affected by contractual commitment to supervisor on a relatively weak level.

Cognitive organizational commitment is negatively affected by affective commitment to supervisor on a relatively moderate level and positively affected by normative and contractual commitment to supervisor on a relatively weak level.

Normative organizational commitment is negatively affected by affective commitment to supervisor on a relatively weak level and positively affected by cognitive and contractual commitment to supervisor on a relatively weak level.

Contractual organizational commitment is not affected by affective, cognitive and normative commitment to supervisor on a significant level (p < 0.05).

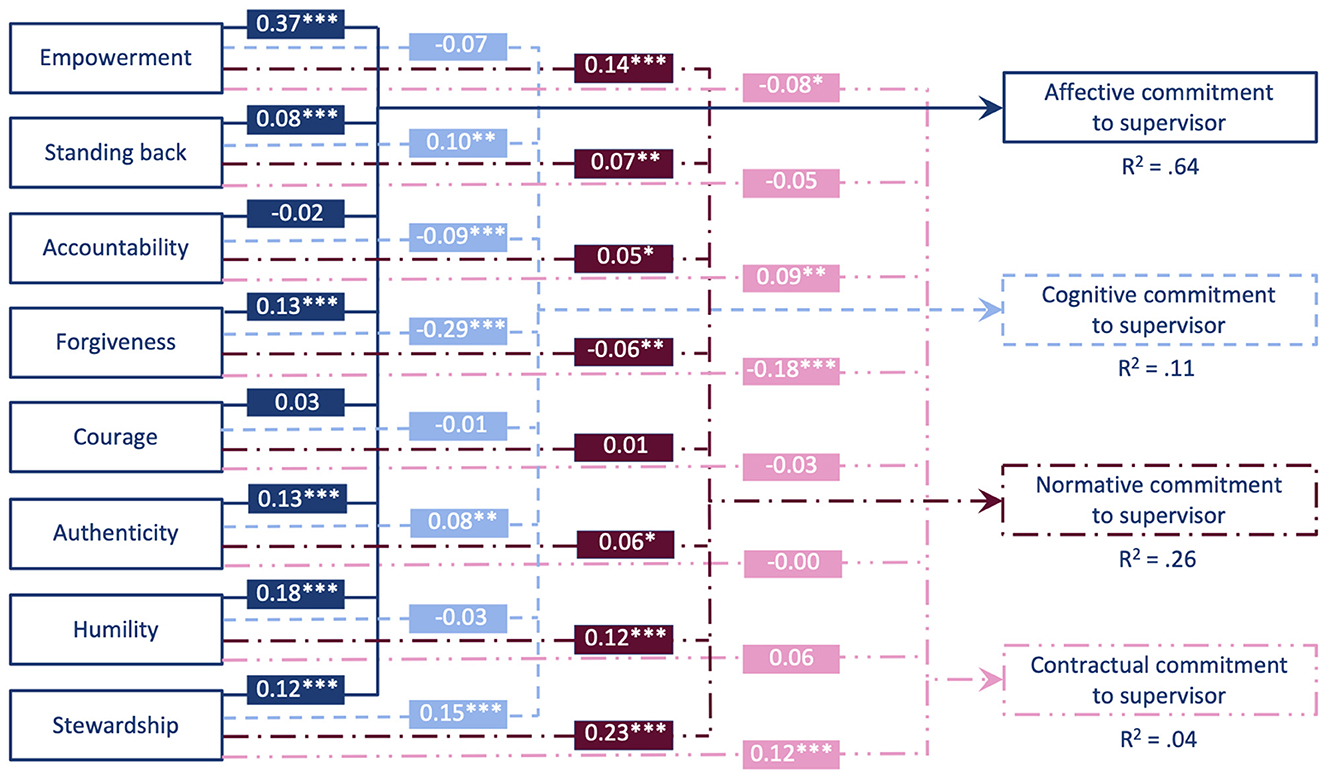

The effects of the facets of servant leadership on commitment to supervisor are represented in Figure 3, including path coefficients, significance levels and R2 for the dependent variables. R2 ranges from 0.04 to 0.64, with affective commitment to supervisor (R2 = 0.64) showing the highest value, followed by normative commitment to supervisor (R2 = 0.26), cognitive commitment to supervisor (R2 = 0.11) and contractual commitment to supervisor (R2 = 0.04).

Figure 3. Effects of the facets of servant leadership on the facets of commitment to supervisor (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; n = 1,756).

Affective organizational commitment is relatively strongly affected by empowerment, relatively moderately by forgiveness, authenticity, humility and stewardship and relatively weakly by standing back. All of these path coefficients are positive.

Cognitive commitment to supervisor is negatively affected by forgiveness on a relatively strong level, positively affected by stewardship on a relatively moderate level and, on a relatively weak level, positively affected by standing back, authenticity and negatively by accountability.

Normative commitment to supervisor is relatively strongly affected by stewardship, relatively moderately by empowerment and humility and relatively weakly by standing back accountability and authenticity, whilst forgiveness negatively affects normative commitment to supervisor on a relatively weak level.

Contractual commitment to supervisor is positively affected by stewardship and negatively affected by forgiveness on a relatively moderate level, whilst empowerment has a relatively weak negative and accountability a relatively weak positive effect on contractual commitment to supervisor.

The implications of our results, the limitations of our study and an outlook are discussed in the following two subsections.

We presented the R2 values for the facets of organizational commitment in Section 3. They indicate that the facets of commitment to supervisor explain 22% to 49% of the variance of the facets of organizational commitment, whilst there must be other not examined factors that can explain the remaining 51%−78% of their variance. This means that commitment to supervisor can be understood as a substantial determinant of organizational commitment, but not the only one.

We could also show that each facet of commitment to supervisor has the strongest effect on its corresponding facet of organizational commitment, e.g., affective commitment to supervisor has the strongest effect on affective organizational commitment. Furthermore, our results reveal that the effects of facets of commitment to supervisor roughly match the correlation structure of the facets of organizational commitment documented in other studies (e.g., Meyer et al., 2002; Gansser and Godbersen, 2023): a positive relationship between affective and normative commitment, and weak or negative relationships between affective and normative commitment with cognitive commitment.

These findings indicate that the four facets of commitment to supervisor, introduced and examined in this study, can be integrated into the overall research and managerial application of employee commitment. Thus, organizations are advised to utilize commitment to supervisor in human resources and managerial considerations when aiming at increasing organizational commitment. Arguably, the integration of commitment to supervisor is even more important for larger and multinational corporations, as the supervisor's psychological proximity and therewith relevance for employees (Becker et al., 1996) might grow in comparison to the representation of an even more abstract and psychological distant corporation.

Other studies show that affective organizational commitment has stronger effects on employee-related outcomes, like job satisfaction, and organizational objectives, like work performance, than normative organizational commitment, whereas cognitive organizational commitment negatively correlates with the afore-mentioned constructs (e.g., Meyer et al., 2002; Cooper-Hakim and Viswesvaran, 2005). Thus, most of the rationally behaving organizations will focus on affective organizational commitment and, with a second priority, on normative organizational commitment. In this case and not very surprising, organizations should improve affective commitment to supervisor and additionally normative commitment to supervisor as central antecedents of their corresponding facets of organizational commitment. This means that supervisors should be sensitized to the respective effects of their behavior on their subordinates and trained accordingly.

The relevance of servant leadership for the facets of commitment to supervisor becomes evident by looking at the variance of the respective commitment facets that can be explained by the facets of servant leadership (cf. R2 in Section 3). The facets of servant leadership can explain a large amount of variance of affective commitment to supervisor (64%), a relatively moderate amount of variance of normative commitment to supervisor (26%) and a relatively low amounts of variance of cognitive (11%) and contractual commitment to supervisor (4%). This indicates that servant leadership shows a high potential to strengthen the commitment of employees to their supervisor on the favorable dimensions of affective and normative commitment, even though it cannot be seen as a panacea for commitment to supervisor. Thus, organizations are advised to introduce and further the concept of servant leaders. This advice is supported by the findings of Hoch et al. (2018) who come to the conclusion that servant leadership can explain favorable outcomes better than other leadership styles. Furthermore, organizations should be aware that servant leadership does not only lead to commitment to supervisor but also to other positive results with regard to employee attitudes, behaviors and performances (Eva et al., 2019).

As pointed out above, it might be beneficial for organizations to strengthen the employees' affective and normative commitment to their supervisors. When hiring, promoting and developing good servant leaders, organizations should prioritize their managers' abilities on servant leadership facets, based on the significant path coefficients presented in Section 3 (also cf. characterization of the servant leadership facets in Section 1.3):

• First priority—Servant leadership facets of empowerment and stewardship: Servant leaders should enable, encourage and support both, the development of their subordinates and the fulfillment of larger visions or goals.

• Second priority—Servant leadership facets of forgiveness, authenticity and humility: Servant leaders should show their true self with regard to accepting their own mistakes and short-comings and those of their subordinates.

• Third priority—Servant leadership facets of standing back and accountability: Servant leaders should set up clear responsibilities for tasks and take themselves back when it comes to taking credits for successes.

Additionally, organizations may pay attention on personal characteristics of managers who show servant leadership behavior. Even though empirical evidence is scarce, servant leaders seem to be rather agreeable and self-confident, less extraverted, and strongly identify with their organization (Eva et al., 2019).

In the afore-presented paragraphs, we focused on the facets of commitment to supervisor, which, through their respective facets of organization commitment, lead to favorable outcomes for organizations (e.g., Meyer et al., 2002; Cooper-Hakim and Viswesvaran, 2005), i.e., affective and normative commitment. However, our results also reveal which facets of servant leadership impact the for organizations less favorable facets of commitment to supervisor, i.e., cognitive and contractual commitment.

Cognitive commitment to supervisor, which can be understood as an employee having to stay with his or her supervisor because of a lack of better and easily accessible alternatives (cf. Section 1), can be slightly strengthend if a supervisor shows stronger behavior in the servant leadership facets of standing back and authenticity and can be moderately strengthened if the supervisor shows stronger behavior in the servant leadership facet of stewardship (cf. path coefficients in Section 3). This means that an employee is less likey to regard other supervisors as better alternatives if the supervisor shows his or her true self, let his or her subordinates take credit for successes, and envisions and enables the achievement of greater goals. Furthermore, the cognitive commitment to supervisor can be strengthend if the supervisor delegates less responsibilities and holds his or her subordinates less accounteable for their performances (servant leadership facet of accountability) and especially is less forgiving with regard to mistakes of his or her subordinates (servant leadership facet of forgiveness), as the negative path coefficients, presented in Section 3, indicate. These negative effects might be surprising at first glance, as one would intuitively think that more servant leadership would lead to more employee commitment. At second glance, these findings make sense because the concepts of servant leadership and cognitive commitment even contradict each other to a large degree. Whilst servant leaders support their subordinates to take responsibility, actively create a “better world” and reach their full individual potential, cognitive commitment represents the result of a rational process, in which merely the pros and cons of given alternatives are assessed. More specifically, reducing the servant leadership facets of accountability and especially forgiveness means taking away some leeway from employees which may foster the rational process of weighing the positives and negatives within a fixed mental framework. This also means from an inverted perspective that a stronger emphasis on accountability and forgiveness on the side of a supervisor weakens cognitive commitment and its respective processes on the side of his or her employees. The finding of a negative impact of servant leadership and especially accountability and forgiveness on cognitive commitment to supervisor is also supported by other studies, as the meta-analysis of Meyer et al. (2002) shows. This meta-analysis reveals that transformational leadership and interactional justice correlate with continuance commitment negatively. Transformational leadership bears resemblance to servant leadership as a whole, interactional justice is concepually related to accountability and forgiveness, and continuance commitment is similar to cognitive commitment. The effect of reducing cognitive commitment through strengthening accountability and forgiveness can even benefit organizations, as cognitive employee commitment can lead to negative outcomes for employees, e.g., reduced work satisfaction, and for organizations, e.g., lower work performance (e.g., Meyer et al., 2002; Cooper-Hakim and Viswesvaran, 2005). However, the afore-mentioned implications have to be taken with caution, as the facets of servant leadership can only explain 11% of the variance of cognitive commitment to supervisor (cf. R2 in Section 3).

The R2 value for contractual commitment to supervisor is even lower and indicates that the facets of servant leadership can only explain 4% of its variance. Thus, changes in contractual commitment can hardly be attributed to servant leadership. If one wants to do this regardless, accountability and stewardship seem to strengthen contractual commitment to supervisor, whilst empowerment and forgiveness seem to have a weakening effect. These effects might be tentatively explained through the emphasis employees place on formal work contracts vs. psychological contracts, which can be defined as an “individual's belief in the terms and conditions of a reciprocal exchange agreement between the focal person and another group” (Rousseau, 1989, p. 123). On one hand, employees might emphasize more on formal rules, like their work contracts, if they are given more responsibilities (servant leadership facet of accountability) and are convinced that they are working toward a greater or common good (servant leadership facet of stewardship). Both aspects could lead to more individual independence so that an employee's reciprocal relationship with his or her supervisor and, therewith, the psychological contract might be weakened; conversely, the contractual commitment might gain more prominence for an employee. On the other hand, employees might focus more on psychological contracts with their supervisor if their self-esteem is strengthened through their personal development (servant leadership facet of empowerment) and their mistakes are forgiven too often or too easily (servant leadership facet of forgiveness). In these cases, employees might perceive a lack of formal rules, which means a lesser commitment to their formal contract.

The implications, presented in the paragraphs above, lead to further implications on a theoretical and research level. Our findings do not only show that a supervisor and an organization represent different foci of employee commitment (Reichers, 1985; Becker, 1992; Meyer et al., 1993; Clugston et al., 2000; Stinglhamber and Vandenberghe, 2003; Vandenberghe et al., 2004; Pohl and Paillé, 2011) but also that commitment to supervisor serves as an antecedent of organizational commitment, confirming the findings of Vandenberghe et al. (2004). Moreover, our findings empirically support a multi-dimensional understanding of commitment to supervisor, as can be found in Becker and Kernan (2003) and Landry et al. (2010). In this context, we could show that the Four-Component Model of Commitment (Gansser and Godbersen, 2023) can provide differentiated and integrated insights for both, commitment to supervisor and organizational commitment. Our study lends further empirical support to the relevance of leadership styles for commitment to supervisor in general (e.g., Emuwa, 2013; Polston-Murdoch, 2013; Imam et al., 2020) and, more specifically, shows the large explanatory power of servant leadership (also cf. Sokoll, 2014). Whilst other studies could demonstrate the positive effects of servant leadership on favorable organizational outcomes (Hoch et al., 2018; Eva et al., 2019), our findings indicate that commitment to supervisor, as a construct that is relatively directly related to a leadership style, could be understood as a central mediator between servant leadership and organizational outcomes.

Additionally, we would like to highlight the negative effect of forgiveness on cognitive, normative and contractual commitment to supervisor. We argued above that employees might feel less cognitively and contractually commited to their supervisor if he or she fogivess too quickly or too easily, due to more individual leeway (cognitive commitment) and a perceived lack of formal rules (contractual commitment). A similar process might occur with regard to normative commitment. If a wrong-doer is forgiven to quickly and to easily without having excused, explained or apoligised for his or her wrong-doing, the relationship between the forgiven and the forgiver can suffer due to an unsolved conflict (Bies et al., 2016). In this context, it is noteworthy that the processes of forgiving and accepting forgiveness need time, which is often invested otherwise in organizations (Bies et al., 2016). Such a process of only superficially and not actually forgiving can lack reciprocal fairness and justices in an employee-supervisor relationship. As reciprocal fairness and justice are core characteristics of normative commitment (cf. Section 1), too much forgiveness can lead to reduced normative commitment to supervisor. On a more general level, forgiveness might have its limitations in the workplace, as it is rather associated with interpersonal close relationships, such as families or friends (McCullough et al., 1997). Even though forgiving is widely regarded as a desirable trait, it can also have religious connotations (Chusmir and Parker, 1991) and can be perceived as a weakness of a supervisor (Nietzsche, 1887/1967). Thus, the appropriateness of forgiveness in the context of work might be questioned in general (Bies et al., 2016).

In our study, we could show that commitment to supervisor is a relevant antecedent of organizational commitment and servant leadership is a relevant antecedent of commitment to supervisor. Our sample indicates a high degree of representativity for the German workforce with regard to gender and age. As we, however, collected our data in the areas of Munich and Stuttgart, the south of Germany is overrepresented in our study. Therefore, a nationwide survey that geographically covers all of Germany might be fruitful. A cross-cultural study might be even more insightful to broaden and deepen the understanding of the examined constructs and their relationships. In this context, especially high-context cultures, e.g., countries from Asia, South America or southern Europe, should be compared with low-context cultures, like Germany or North America (Hall, 1976).

We could empirically establish the relationships between organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership. Moreover, future research might look beyond the constructs of organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership, and integrate further attitudinal, behavioral and performance-related aspects on the side of employees, supervisors and organizations, e.g., occupational commitment, voice behavior or supervisor performance. This perspective is especially valid for the facets of servant leadership, as their antecedents are under-researched, as Eva et al. (2019) pointed out. Furthermore, a better understanding of the antecedents of servant leadership might provide organizations and managers with a more detailed guideline to improve servant leadership behavior.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical approval was not required for this study involving humans because the study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical review and approval were not required for this study in accordance with the institutional requirements. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

HG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SR: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/forgp.2024.1353959/full#supplementary-material

Ajzen, I. (1985). “From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior,” in Action Control, eds J. Kuhl, and J. Beckmann (New York, NY: Springer), 11–39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Barbuto, J. E., and Wheeler, D. W. (2006). Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group Organ. Manage. 31, 300–326. doi: 10.1177/1059601106287091

Becker, T. E. (1992). Foci and bases of commitment: are they distinctions worth making? Acad. Manag. J. 35, 232–244. doi: 10.5465/256481

Becker, T. E., Billings, R. S., Eveleth, D. M., and Gilbert, N. L. (1996). Foci and bases of employee commitment: implications for job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 39, 464–482. doi: 10.2307/256788

Becker, T. E., and Kernan, M. C. (2003). Matching commitment to supervisors and organizations to in-role and extra-role performance. Hum. Perform. 16, 327–348. doi: 10.1207/S15327043HUP1604_1

Bies, R. J., Barclay, L. J., Tripp, T. M., and Aquino, K. (2016). A systems perspective on forgiveness in organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 10, 245–318. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2016.1120956

Cheng, B.-S., Jiang, D.-Y., and Riley, J. H. (2003). Organizational commitment, supervisory commitment, and employee outcomes in the Chinese context: proximal hypo- thesis or global hypothesis? J. Organ. Behav. 24, 313–334. doi: 10.1002/job.190

Chughtai, A. A. (2013). Linking affective commitment to supervisor to work outcomes. J. Manag. Psychol. 28, 606–627. doi: 10.1108/JMP-09-2011-0050

Chusmir, L. H., and Parker, B. (1991). Gender and situational differences in managers' values: a look at work and home lives. J. Bus. Res. 23, 325–335. doi: 10.1016/0148-2963(91)90018-S

Claus, L. (2019). HR disruption—time already to reinvent talent management. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 22, 207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.brq.2019.04.002

Clugston, M., Howell, J. P., and Dorfman, P. W. (2000). Does cultural socialization predict multiple bases and foci of commitment? J. Manage. 26, 5–30. doi: 10.1177/014920630002600106

Cooper-Hakim, A., and Viswesvaran, C. (2005). The construct of work commitment: testing an integrative framework. Psychol. Bull. 131, 241–259. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.241

Dennis, R. S., and Bocarnea, M. (2005). Development of the servant leadership assessment instrument. Leadership Org. Dev. J. 26, 600–615. doi: 10.1108/01437730510633692

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., and Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 71, 500–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

Emuwa, A. (2013). Authentic leadership: commitment to supervisor, follower empowerment, and procedural justice climate. Emerg. Leadersh. Journeys 6, 45–65.

Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., Van Dierendonck, D., and Liden, R. C. (2019). Servant leadership: a systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh. Q. 30, 111–132. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

Faraway, J. (2022). Package ‘faraway'. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/faraway/faraway.pdf (accessed November 30, 2023).

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior. An Introduction to Theory and Research. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Gansser, O., and Godbersen, H. (2017). Mitarbeiterbindung durch betriebliches gesundheitsmanagement in theorie und praxis. Z. Führung Organ. 86, 108–116.

Gansser, O., and Godbersen, H. (2023). Vier-Komponenten-Modell der Mitarbeiterbindung. Available online at: https://zis.gesis.org/skala/Gansser-Godbersen-Vier-Komponenten-Modell-der-Mitarbeiterbindung (accessed November 30, 2023).

Godbersen, H., Moser, S., and Gansser, O. (2021). Arbeitszufriedenheit und mitarbeiterbindung bei frauen - empirische erkenntnisse und handlungsansätze für unternehmen. Z. Führung Organ. 90, 95–103.

Godbersen, H., Ruiz Fernández, S., Machura, M., Parlak, D., Wirtz, C., Gansser, O., et al. (2022). “Work-life balance measures, work-life balance, and organisational commitment – a structural analysis,” in ipo Schriftenreihe der FOM Band 3, eds M. Zimmer, and C. Rüttgers (Potsdam: MA Akademie Verlags- und Druck-Gesellschaft mbH).

Godbersen, H., and Scharpf, J. (2021). Effekte von agilem projektmanagement - wie sich der agilitätsgrad auf die arbeitszufriedenheit und mitarbeiterbindung auswirkt. Z. Führung Organ. 90, 394–401.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Gutierrez-Broncano, S., Linuesa-Langreo, J., Ruiz-Palomino, P., and Yánez-Araque, B. (2024). General manager servant leadership and firm adaptive capacity: the heterogeneous effect of social capital in family versus non-family firms. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 118:103690. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2024.103690

Guzeller, C. O., and Celiker, N. (2020). Examining the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention via a meta-analysis. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 14, 102–120. doi: 10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2019-0094

Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., and Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. J. Manage. 44, 501–529. doi: 10.1177/0149206316665461

Huyghebaert, T., Gillet, N., Audusseau, O., and Fouquereau, E. (2019). Perceived career opportunities, commitment to the supervisor, social isolation: their effects on nurses' well-being and turnover. J. Nurs. Manag. 27, 207–214. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12666

Imam, H., Naqvi, M. B., Naqvi, S. A., and Chambel, M. J. (2020). Authentic leadership: unleashing employee creativity through empowerment and commitment to the supervisor. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 41, 847–864. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-05-2019-0203

International Labour Organization (2012). International Standard Classification of Occupations. Structure, group definitions and correspondence tables. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Jackson, T. A., Meyer, J. P., and Wang, X. H. (2013). Leadership, commitment, and culture: a meta-analysis. J. Lead. Organ. Stud. 20, 84–106. doi: 10.1177/1548051812466919

Jenkins, M., and Paul Thomlinson, R. (1992). Organisational commitment and job satisfaction as predictors of employee turnover intentions. Manag. Res. News 15, 18–22. doi: 10.1108/eb028263

Kooij, D. T. A. M., Jansen, P. G. W., Dikkers, J. S. E., and De Lange, A. H. (2010). The influence of age on the associations between HR practices and both affective commitment and job satisfaction: a meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 31, 1111–1136. doi: 10.1002/job.666

Landry, G., Panaccio, A., and Vandenberghe, C. (2010). Dimensionality and consequences of employee commitment to supervisors: a two-study examination. J. Psychol. 144, 285–312. doi: 10.1080/00223981003648302

Laub, J. A. (1999). Assessing the servant organization: development of the servant organizational leadership assessment (SOLA) instrument [Dissertation]. Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL.

Levinson, H. (1965). Reciprocation: the relationship between man and organization. Adm. Sci. Q. 9, 370–390. doi: 10.2307/2391032

Lewin, K. (1943). Defining the field at a given time. Psychol. Rev. 50, 292–310. doi: 10.1037/h0062738

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., and Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 19, 161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

McCullough, M. E., Worthington, E. L. Jr., and Rachal, K. C. (1997). Interprsonal forgiving in close relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73, 321–336. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.321

McMurray, A. J., Scott, D. R., and Pace, R. W. (2004). The relationship between organizational commitment and organizational climate in manufacturing. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 15, 473–488. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1116

Meyer, J. P., and Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualisation of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1, 61–89. doi: 10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., and Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 78, 538–551. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., and Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 61, 20–52. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., and Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-509370-5.50005-8

Nietzsche, F. (1887/1967). On the Genealogy of Morals (Transl. by. W. Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale). New York, NY: Vintage.

O'Reilly, C. A., and Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: the effects of compliance, identification and internalization on prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 71, 492–499. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.492

Pohl, S., and Paillé, P. (2011). The impact of perceived organizational commitment and leader commitment on organizational citizenship behaviour. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 14, 145–161. doi: 10.1108/IJOTB-14-02-2011-B001

Polston-Murdoch, L. (2013). An Investigation of path-goal theory, relationship of leadership style, supervisor-related commitment, and gender. Emerg. Leadersh. J. 6, 13–44.

Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., and Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 59, 603–609. doi: 10.1037/h0037335

Putri, Q. H., and Setianan, A. R. (2019). Job enrichment, organizational commitment, and intention to quit: the mediating role of employee engagement. Probl. Perspect. Manag 17, 518–526. doi: 10.21511/ppm.17(2)0.2019.40

R Core Team (2017). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed November 30, 2023).

Redman, T., and Snape, E. (2005). Unpacking commitment: multiple loyalties and employee behaviour. J. Manag. Stud. 42, 301–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00498.x

Reed, L. L., Vidaver-Cohen, D., and Colwell, S. R. (2011). A new scale to measure executive servant leadership: development, analysis, and implications for research. J. Bus. Ethics 101, 415–434. doi: 10.1007/s10551-010-0729-1

Reichers, A. E. (1985). A review and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 10, 465–476. doi: 10.2307/258128

Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., and Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: the contribution of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 825–836. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

Riketta, M., and Van Dick, R. (2005). Foci of attachment in organizations: a meta-analytic comparison of the strength and correlates of workgroup versus organizational identification and commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 67, 490–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.06.001

Rosenberg, M. J., and Hovland, C. I. (1960). “Cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of attitudes,” in Attitude Organization and Change: An Analysis of Consistency Among Attitude Components (Yales Studies in Attitude and Communication), eds M. J. Rosenberg, C. I. Hovland, W. J. McGuire, R. P. Abelson, and J. W. Brehm (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press), 1–14.

Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2, 121–139. doi: 10.1007/BF01384942

Sanchez, G. (2013). PLS Path Modeling with R. Available online at: https://www.gastonsanchez.com/PLS_Path_Modeling_with_R.pdf (accessed November 30, 2023).

Sendjaya, S., Sarros, J. C., and Santora, J. C. (2008). Defining and measuring servant leadership behaviour in organizations. J. Manag. Stud. 45, 402–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00761.x

Sokoll, S. (2014). Servant leadership and employee commitment to a supervisor. Int. J. Leadersh. Stud. 8, 88–104.

Solinger, O. N., van Olffen, W., and Roe, R. A. (2008). Beyond the three-component model of organizational commitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 70–83. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.70

Statistisches Bundesamt (2023). Mikrozensus. Bevölkerung, Erwerbstätige, Erwerbslose, Erwerbspersonen, Nichterwerbspersonen aus Hauptwohnsitzhaushalten: Deutschland, Jahre, Geschlecht, Altersgruppen. Available online at: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=tableandcode=12211-0001andbypass=trueandlevelindex=1andlevelid=1690285775292#abreadcrumb (accessed November 30, 2023).

Stinglhamber, F., and Vandenberghe, C. (2003). Organizations and supervisors as sources of support and targets of commitment: a longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 24, 251–270. doi: 10.1002/job.192

van Dierendonck, D., and Nuijten, I. (2011). The servant leadership survey: development and validation of a multidimensional measure. J. Bus. Psychol. 26, 249–267. doi: 10.1007/s10869-010-9194-1

Vandenberghe, C., and Bentein, K. (2010). A closer look at the relationship between affective commitment to supervisors and organizations and turnover. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 82, 331–348. doi: 10.1348/096317908X312641

Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., and Stinglhamber, F. (2004). Affective commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: antecedents and outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 64, 47–71. doi: 10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00029-0

Verdorfer, A. P., and Peus, C. (2014). The measurement of servant leadership: validation of a German version of the Servant Leadership Survey (SLS). Z. Arbeits Organ. Psychol. 58, 1–16. doi: 10.1026/0932-4089/a000133

Wong, P. T. P., and Davey, D. (2007). “Best practices in servant leadership,” in Paper presented at the Servant Leadership Research Roundtable, School of Global Leadership and Entrepreneurship (Virginia Beach VA: Regent University).

Keywords: organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor, employee commitment, servant leadership, servant leader

Citation: Godbersen H, Dudek B and Ruiz Fernández S (2024) The relationship between organizational commitment, commitment to supervisor and servant leadership. Front. Organ. Psychol. 2:1353959. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2024.1353959

Received: 11 December 2023; Accepted: 09 April 2024;

Published: 03 May 2024.

Edited by:

Pablo Ruiz-Palomino, University of Castilla-La Mancha, SpainReviewed by:

Ranjita Islam, Queensland University of Technology, AustraliaCopyright © 2024 Godbersen, Dudek and Ruiz Fernández. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hendrik Godbersen, aGVuZHJpay5nb2RiZXJzZW5AZm9tLmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.