- Farmingdale State College, Farmingdale, NY, United States

Introduction: Past research on the “bamboo ceiling” tend to focus on the barriers it presents, with few studies examining individuals who break through the bamboo ceiling. The purpose of this study is to explain the psychological factors driving the individual differences between East Asian Americans who break through the bamboo ceiling and those who do not.

Methodology: This two-study sequential mixed-methods exploratory research study included 19 one-on-one semi-structured interviews and 338 survey respondents by East Asian Americans.

Results: In Study 1, based on 19 one-on-one semi cultural essentialism and bicultural identity integration emerged from the interview data as contributing factors. Interviewees who exhibited essentialist or social constructionist beliefs showed different behavioral and career patterns. This mediating relationship was supported in Study 2. Taken together, it was found that East Asian Americans who had less essentialist views of culture were more likely to have a fluid and integrated bicultural identity and more likely to break the bamboo ceiling in their careers.

Discussion: The findings from both qualitative and quantitative data suggest that having more fluid concepts of culture, associating with more integrated bicultural identities, may improve career prospects in a multicultural work environment. This article offers practical implications for Asian Americans who desire to achieve their career goals to be authentic self while remaining adaptable and developing a mindset of “flexibility.”

Introduction

Asian Americans are Americans of East Asian, Southeast Asian, or South Asian origin. The 2020 U.S. Census reported that 20.6 million people, comprising 6.2% of the total population, identified as Asian, showcasing a remarkably diversity within this demographic (Monte and Shin, 2022). Although Asian Americans are well represented in higher education and professional careers, their presence in the highest levels of management tends to be disproportionately lacking (Hyun, 2006; Thatchenkery and Sugiyama, 2011; Yang, 2011; Yu, 2020). This under-representation of Asian Americans in upper management in the U.S. is known as the “bamboo ceiling” (Hyun, 2006; Yu, 2020), a term specifically describing the invisible barrier hindering Asian Americans from advancing to leadership positions in organizations (Hyun, 2006). This is particularly important given the U.S. workforce has become increasingly diverse, with a growing demand on achieving Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) goals pressuring organizations to examine their current practices and policies. The presence of a bamboo ceiling would present a barrier to DEI initiatives and goals, especially with the rapid growing population of Asian Americans.

It should be noted that although Asian representation in upper management is lacking, there is still representation. Analysis done on U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) data over time does show Asians in American managerial positions (Gee and Peck, 2015; Gee et al., 2015). However, it is unclear why some Asians advance to upper management positions while others do not. Career attainment is influenced by external barriers as well as individual-level factors. Most of the research on the bamboo ceiling tend to focus on external structural barriers contributing to Asian underrepresentation, such as the ethnic homogeneity of social networks (Lu, 2022), perceived discrimination (Yu, 2020), or aversive racism (Williams, 2008). Research on individual-level factors have primarily focused on underdeveloped leadership skills (Gee et al., 2015), with a select few examining why some Asians do break through the bamboo ceiling (cf. Kawahara et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2020, 2022; Lu, 2022). As the population of cultural minorities grow, continued research on the internal individual factors can contribute to our understanding of how culture elements influence perspectives and behaviors and empower individuals to navigate challenges, career advancement, and promote resilience in existing organizational structures. Considering the documented cultural differences between Asians and mainstream Americans (Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Cai et al., 2011; Fehrenbacher et al., 2018; Benson et al., 2020), the question remains: What are some of the cultural-psychological factors at the individual level that impact the different career outcomes of Asian Americans?

In this study, we utilized a sequential two-study mixed methods design, integrating both qualitative and quantitative methods, to better understand the possible individual cultural-psychological factors that influence the career attainment of Asian Americans. As the bamboo ceiling is a cultural phenomenon prevalent among East Asian Americans (Yu, 2020; Lu et al., 2022), e.g., Asian Americans of Chinese, Japanese, and/or Korean descent, we focused on East Asian Americans due to the challenge of addressing the diverse range of Asian subgroups comprehensively. We envision this study as a foundational step for future research, aspiring to capture the intricate and distinct experiences of various East Asians. In the first qualitative study, we interviewed East Asian Americans working in the U.S. to gain a fundamental understanding of the potential underlying cultural-psychological factors for their career attainment. Cultural essentialism, the belief that members of a particular culture share fixed and universal characteristics (Chao et al., 2007; Chao and Kung, 2015), and bicultural identity integration, how biculturals manage their dual cultural identities (Benet-Martínez et al., 2002), emerged as the psychological factors to explain the different perceptions of their cultural identities and behaviors at their workplaces. We then conducted a quantitative survey of East Asian Americans to validate the findings from the first qualitative study. The combined results show that cultural essentialism and bicultural identity influencing the behavioral and career outcomes: East Asian Americans who had less essentialist views of culture were more likely to have fluid and integrated bicultural identity and more likely to achieve attainment in their careers.

Our study advances knowledge of cultural essentialism and demonstrates its effect on bicultural identity integration. Our findings shed light on how cultural mindset can directly or indirectly influence the career outcomes of biculturals in a culturally diverse working environment. The understanding of cultural essentialism as a barrier for growth can potentially empower East Asian Americans to navigate professional growth opportunities when facing structural and systemic obstacles. The findings indicate important managerial implications for companies to foster a social constructionist mindset among employees from all backgrounds to develop more inclusive workplaces.

Study 1 literature review

Causes of the bamboo ceiling

Many discussions of Asian American achievement in the U.S. note that although Asian Americans are well represented in higher education and professional career, their presence in progressively higher levels of management tend to be disproportionately lacking (Hyun, 2006; Hechler, 2011; Thatchenkery and Sugiyama, 2011; Yang, 2011). Gee et al. (2015) analyzed 2013 EEOC data and noted that although Asian Americans represented roughly 27% of the reported professional workforce, they only represented around 14% of the executive workforce. An updated report by Gee and Peck (2015) analyzing 2015 EEOC data showed no improvement in the intervening two years. The pattern is further reinforced by more recent data counting only 32 Asian American CEOs in Fortune 500 and S&P 500 companies (Yu, 2020).

Williams (2008) argued for aversive racism and shifting standards as reasons why Asian Americans are rarely promoted to managerial positions in the US workforce. Mosenkis (2010) reviewed bamboo ceiling research and lists several possible factors contributing to the bamboo ceiling, such as systematic discrimination, underperformance on the workplace, and differences in values systems relative to mainstream American culture. Gee et al. (2015), citing Catalyst (2003), argued for “underdeveloped leadership skills,” with cultural deference to authority, ineffective communications, political naiveté, and risk aversion being the primary skills lacking among Asian Americans.

It should be noted that although Asian representation in upper management is lacking, there is still a representation. EEOC data reviewed and analyzed by Gee still show a number of Asians in American managerial positions. However, it is unclear why some Asians can climb the corporate ladder to upper management positions, while others are not able of doing so. Furthermore, research also shows that not all Asian Americans are similarly affected by the bamboo ceiling phenomenon. Lu et al. (2020) and Yu (2020) both noted that South Asian Americans seem to not encounter as many barriers in their career outcome attainment. Lu's series of studies further discovered that differences in assertiveness (Lu et al., 2020), ethnic homophily of social networks (Lu, 2022), and negotiation behaviors (Lu, 2023), between East and South Asian Americans contributed to different career outcomes.

The prevailing literature reviewed earlier, exploring the origins of the bamboo ceiling, has predominantly focused on behavioral or task-oriented deficiencies among Asians who do not progress to higher positions, as well as systemic and organization factors (Mosenkis, 2010; Yu, 2020). Related research on Asian American career selection and development also acknowledges the intricate interplay between structural and cultural factors from individual, familial, communal, and societal levels influencing the career experience of Asian Americans (Tu and Okazaki, 2021). In this study, we shift our attention from the externally oriented factors, which are undoubtedly important and valid, to the exploration of potential internal cultural-psychological factors that might influence the career attainment of East Asian American. Hyun (2006) highlighted various avenues for Asian Americans to overcome the bamboo ceiling, however ultimately concluded that absent systemic or organizational shifts, the responsibility falls upon Asian Americans to explore individual factors within their cultural backgrounds. This implies a need for personal self-awareness among Asian Americans to further understand how cultural elements can influence their perspectives, behaviors, and decision-making. Such awareness can empower individuals to navigate professional challenges and contribute to their own career advancement within the existing organizational structures. Therefore, an exploration of individual cultural psychological factors becomes essential and will involve recognizing and leveraging cultural strengths or addressing cultural barriers, thereby facilitating personal growth and resilience in the face of systemic obstacles.

Study 1 methodology

Participants and procedures

The objective of Study 1 is exploratory in nature and to understand the perspectives of East Asian American interviewees regarding their cultural background or identity in relation to their career attainment. Considering the extensive range of cultural-psychological frameworks available in existing literature, we chose to employ a qualitative approach in Study 1 allow for a detailed exploration of individual experiences, perceptions, and beliefs related to their career attainment. This qualitative phase is crucial to allow us uncovering new insights and to refine the research focus and bodies of literature. It lays the groundwork for us identifying relevant variables and generating hypothesis for the subsequent quantitative examination. All research methodologies used were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the authors' home institution.

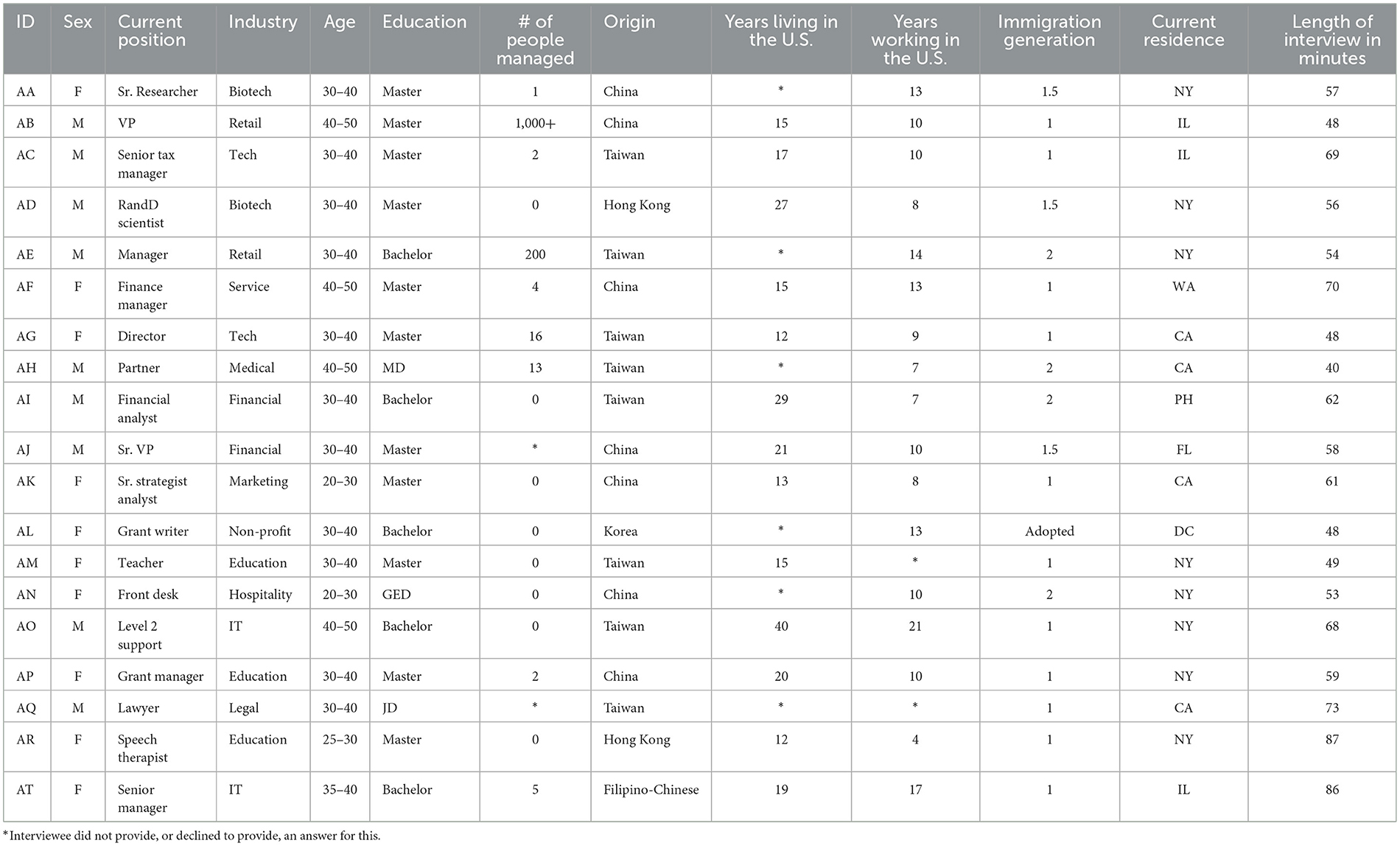

The qualitative data was collected through semi-structured individual interviews conducted by the authors. Participants were recruited using the snowball method, starting with our own personal social networks. A general recruitment pitch was used to obtain the widest possible range of different individual and career profiles, and required only interviewees be Asians in the U.S. In order to limit self-selection bias, the recruitment language only stated that the authors were conducting a study on East Asian American career progress in the U.S. and would like to interview any willing individual. This resulted in face-to-face or phone interviews with 19 East Asian Americans. No interviewees were excluded by the authors, with exception of two participants who could not be reached or withdrew prior to the actual interview and were therefore removed from the interview sample pool. Interviewees were not compensated for their time. Table 1 provides the individual profiles of the interviewees.

The interviewees were between 20 to 40 years of age with some years of professional experience to meet the research question requirement. They were first-, 1.5-, and second-generation immigrants with Chinese cultural backgrounds, except for one Korean interviewee adopted by an American family. We defined first generation as those who were foreign born and immigrated to the U.S. after the age of 13, 1.5 generation as those who immigrated before the age of 13, and second generation as those born in the U.S. (cf. Lee and Zhou, 2014). Education levels ranged from GED, bachelor, master, to MD/JD. The interviewees also came from various industries such as retail, finance, education, legal, education, or non- profit organizations. They also had diverse jobs, such as attorney, manager, researcher, grant writer, or front desk clerk. Eight of the interviewees were in managerial positions with direct or indirect employees reporting to them; one of the interviewees was a Vice-President of a major retailer in the Midwest, indirectly managing more than a thousand employees. We attempted to recruit both managerial and non-managerial interviewees to explore possible differences between the two groups. Every interviewee was educated in the U.S. and had lived or worked in the U.S. for more than a decade. The diverse backgrounds of interview participants allowed us to identify a common theme across their diverse characteristics.

Before each interview, we informed the interviewee of the purpose of our study and obtained consent for recording and follow-up as needed. The interviewees were asked their language preference for the interviews. English was chosen by everyone due to being their primary or only language at work. Therefore, all interviews were conducted in English and lasted an hour on average. The chosen set of semi-structured interview questions was designed to comprehensively explore the participants' experiences and perspectives relevant to our objective of Study 1. We initiated the interviews with inquiries about participants' demographic, educational, and professional backgrounds to establish a contextual foundation. The subsequent major questions were strategically formulated to understand key aspects of their career experiences: (a) Their career trajectory, how they felt about their career progress, and possible reasons for their progressions; (b) Whether they thought being an Asian American had any influence on their career; (c) Whether they felt more Asian or more American, what the differences were, and how they felt as Asian Americans; (d) We also asked about the diversity of their workplace and their social circle at work and outside of work. These questions were selected to capture a nuanced understanding of the participants' cultural, professional, and social contexts, aligning with the study's focus on the interplay between their perceptions of cultural factors and career experiences in organizational settings. All interviews were recorded and transcribed to a total of 308 pages of transcribed text.

Study 1 analysis

Given the exploratory nature of Study 1, we followed the interpretive tradition rather than deductive explanation (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Orlikowski, 2000). Data analysis started while we were conducting the interviews. We adopted the “pattern coding” approach (Miles and Huberman, 1994), a way to identify emergent themes, configurations, or explanations. We analyzed and compared continuing themes and concepts to refine insight and develop conceptual categories through an interactive process of moving iteratively between the data, emerging constructs, and previous literature (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Corley and Gioia, 2004).

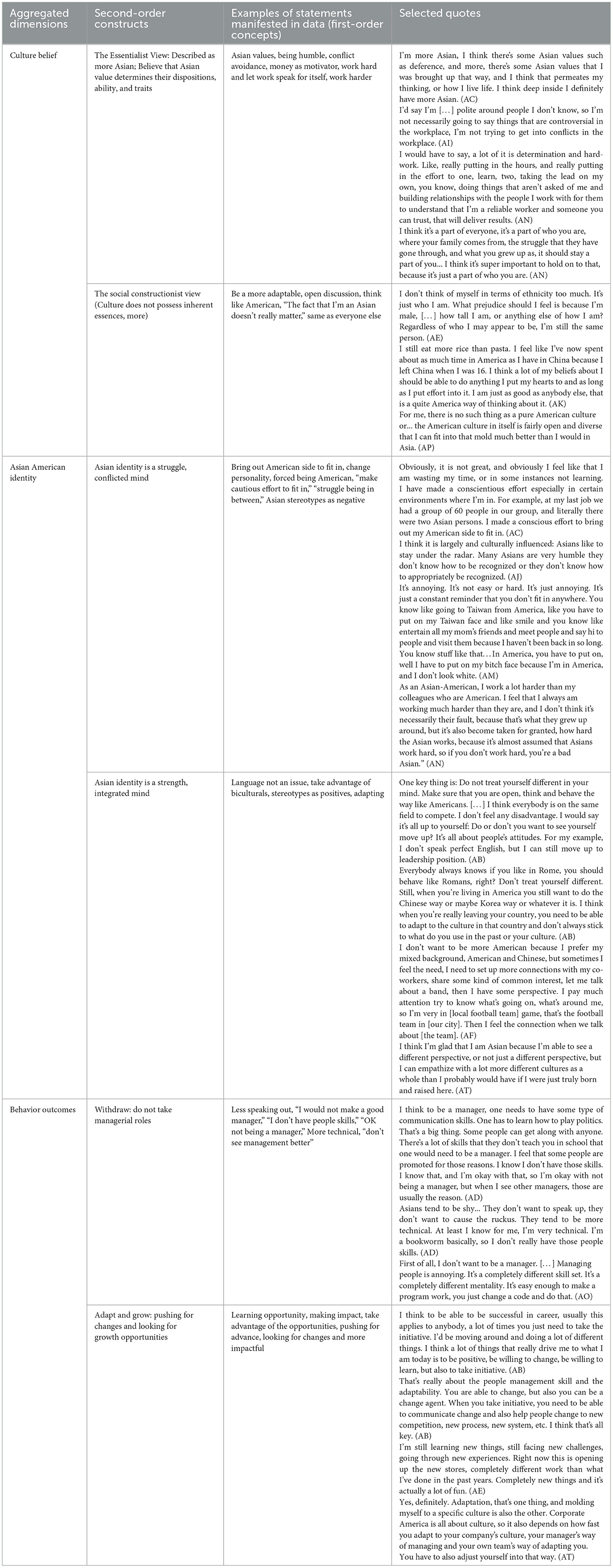

We first conducted a first-level coding to identify key emerged concepts (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). We shifted back and forth between the raw data and existing literature to identify the emerged theme (Strauss and Corbin, 1998; Charmaz, 2006). We initially explored possible factors that may have influenced participants' career paths, such as social networks, work environment, and level of acculturation in U.S. culture. However, we were most interested in any individual differences between those who felt they had achieved or not achieved their own career goals due to individual cultural factors. It was at this point that the concepts of cultural essentialism (Levy et al., 2006; Chao et al., 2007) and bicultural identity integration (BII; Benet-Martínez et al., 2002) emerged from the data when the interviewees, being from diverse educational and professional backgrounds, discussed their perceived differences between their heritage and host cultures and their perspectives toward their Asian American identities. We therefore investigated essentialism and BII literature and focused on how the two bodies of research related to the beliefs, attitudes, cultural identities, and career outcomes of our interviewees. Equipped with the understanding of the literature, we grouped the first-level concepts into second-level abstract codes, categorizing their views on cultures, attitude toward identity, behaviors at the workplaces, and career attainment outcomes. Subsequently, we aggregated these second-level codes into theoretical dimensions. In the later stages of the analysis, we used the emerged codes to analyze the remaining interviews. This analysis process helped us identify common themes among the interviewees and map out potential relationships between the codes. The determination of theoretical saturation was not based on a fixed number of interviews but rather on the point at which no new properties or conceptual insights were emerging from the data (Glaser, 1992). We reached this decision through constant comparison and analysis of the gathered information, ensuring that the data saturation point was driven by the richness and depth of the content. We decided to conclude interviews after ensuring that additional interviews yielded no further meaningful contributions to the theoretical framework (Charmaz, 2006). Table 2 presents the data structure resulting from our overall analysis with the selected quotes for each theme from the interviewees.

Table 2. Data structure: cultural belief, identity, and career outcomes with selected quotes from interviewees.

Study 1 results

Culture beliefs

Interviewees in Study 1 demonstrated two distinctive beliefs toward their Asian heritage culture and their influences on living and working in the U.S.

The essentialist view

The interviewees who endorsed the essentialist view reflect the belief that culture determines a person's dispositions and unalterable physical and psychological markers as an indication of one's ability and traits (Chao et al., 2013). Prior research shows when discussing personal experiences in the two cultures, individuals who endorse an essentialist belief would represent the Chinese and American cultures as incompatible, discrete entities (Chao et al., 2013). Our interviewees who endorsed essentialist beliefs often described themselves as “more Asian” and emphasized that their culture was an important part of their identity and that their ethnicity had a significant impact on the decisions they made regarding their lives and careers. For example, AH, a second-generation immigrant, is a partner in a medical association. Despite his success in the medical field, he expressed no interest in managerial roles such as department chief, and commented on the impact of ethnic background on his career choice:

I think of course [ethnicity] has influenced… My parents were both within the science field. My father was studying engineering. My mother was studying chemistry in college. Of course, they emphasized more science. […] There's no doubt that it's something that made me moved to medicine because it's something that is more predictable and secure. The Asian background is one of the reasons why I took that as well. (AH)

The social constructionist view

On the contrary, the interviewees who endorsed the social constructionist view indicate their belief that culture is a social construction and that culture does not possess inherent essences (Chao et al., 2013). Contrary to those who endorsed essentialist views, the interviewees who endorsed social constructionist views did not view being different as a disadvantage. They did not think that their love for ethnic cuisine or their adherence to cultural traditions at home set them apart from their co-workers. Most importantly, they believed that being Asian did not matter for their career, nor did they think about their ethnicity at work. AE, a manager at a major retailer and a second-generation immigrant, commented:

I don't think of myself in terms of ethnicity too much. It's just who I am. What prejudice should I feel is because I'm male, […] how tall I am, or anything else of how I am? Regardless of who I may appear to be, I'm still the same person. (AE)

Asian-American identities

When describing their self-perception as Asian Americans, interviewees conveyed two distinct perspectives concerning their identities.

Conflicted identity

Interviewees who endorsed culture essentialism were more cautious of the distinctions between Asian and American workplace culture. They also made the extra effort to fit into their work or cultural environment and exhibited more emotional stress from such effort. AC, a senior tax manager, described his own struggle:

Obviously, it is not great, and obviously I feel like that I am wasting my time, or in some instances not learning. I have made a conscientious effort especially in certain environments where I'm in. For example, at my last job we had a group of 60 people in our group, and literally there were two Asian persons. I made a conscious effort to bring out my American side to fit in. (AC)

Consistent with prior research that essentialists would experience more difficulty in passing between cultures, manifest in greater cognitive effort when switching rapidly between cultural frames and greater emotional reactivity when describing personal experiences with both cultures (Chao et al., 2013), interviewees demonstrated their sensitivity and effort to fit into their host cultural environment and their emotional stress when switching between different cultural frames. They described themselves as being “in-between” American and Asian cultures, resulting in conflicting identities. They did not think their non-Asian counterparts would be interested in their cultural preferences, such as music or food, therefore they opted not to discuss them. They also perceived being social minorities as disadvantageous because they “look different.”

Integrated identity

On the other hand, social constructionists talked about how easily they could switch between their home and host cultures. Compared to Asian Americans who held an essentialist views, they paid less attention on their cultural background at work and were more likely to align their responses with American culture (No et al., 2008). AB, a Vice-President of a major retail company, discussed the factors that drove his success:

One key thing is: Do not treat yourself different in your mind. Make sure that you are open, think and behave the way like Americans. […] I think everybody is on the same field to compete. I don't feel any disadvantage. I would say it's all up to yourself: Do or don't you want to see yourself move up? It's all about people's attitudes. I don't speak perfect English, but I can still move up to leadership position. (AB)

AB's statement indicated that he saw himself being equal to others and aligned his mindset and behaviors to the American work environment. He did not consider his apparent imperfect English or his love of Chinese traditional food preventing him from thinking or behaving as his American peers. This shows that despite being aware of cultural differences, he didn't perceive himself as being different from his peers in the host culture environment.

AJ spoke of his experiences in taking advantage of Asian stereotypes. In contrast to those with essentialist views, he felt Asian stereotypes positively brought him advantages and opportunities to handle challenging tasks:

I'm probably one of the dumbest Asians you'll ever meet. One, I don't fulfill the smart analytical or the mathematical type. I think I'm more sociable than the typical Asian. That's where I really standout and shine when I play the stereotype to my advantage but using my social skills to gain more presence. […] I have learned to grow myself as a public speaker, so I speak on many occasions at different conferences. That's not a role that many Asians play so I think that is unique for me to be remembered by a large presence of non-Asians. (AJ)

The quotes above show that social constructionists emphasize the flexibility of adapting to different cultural environment for different experiences. They do not present cognitive difficulties when they have to switch rapidly between different cultural frames, nor show emotional reactivity when discussing their bicultural identity (Chao et al., 2013). Overall, they demonstrated a more integrated mind, more easily switching between different cultural environments, and appreciated the advantages brought by their identities.

Behavior outcomes and career paths

With differing views on their culture and perceptions of their Asian American identity, we also observed how these different beliefs and perceptions shaped their behaviors differently in organization settings.

Withdraw

Among those who endorse essentialist views, the focus on their Asian ethnicity indirectly diminished their desire to taking the leadership roles at the workplace. They often selected career paths guided by cultural expectations and may not have had confidence in their capacity to break free from these predefined boundaries. They justified their lack of interest in leadership position by saying “I am not good [at] being a manager” or they did not have the personality or skills. AD, an R&D scientist in the bio-tech industry, described himself matching common impressions of Asians:

Asians tend to be shy... They don't want to speak up, they don't want to cause the ruckus. They tend to be more technical. At least I know for me, I'm very technical. I'm a bookworm basically, so I don't really have those people skills. (AD)

When asked about becoming a manager, AD said:

A lot of being a manager or managing people, it's about personality, and sometimes you just don't have it. Sometimes no amount of training can fix that… I'm certainly not one of them…At this age I know the type of person I am, I know what I'm capable of and what I'm not capable of. I have a pretty good idea of the type of work I would excel at and the type of work that I would not enjoy doing. I see myself as more of a scientist than a manager. I think that's basically what I've decided in my 30 years of age. (AD)

Adapt and grow

The interviewees with social constructionist views concentrated on identifying learning and growth opportunities through understanding their own “strengths” and “weaknesses,” and strategically planned their upward career trajectory and “pushing for changes.” AG, a first-generation immigrant and a director in a large technology company, described the reason she prefers leadership role by making a larger impact in her organization:

Basically, I want help people make better decisions, for example, using better products and understand what users want, build products to solve problems. It's a quantifiable measurement, like “I make additional 10 million for our company this quarter.” I think those are part of the impacts that I'm hoping for. (AG)

At the opposite end of the spectrum, the interviewees with social constructionist views all exhibited career progress. They tended to use the phrases such as “positive attitudes,” “adapting,” “take initiatives,” “take the learning opportunity,” “pushing for changes,” and “building teams,” which could predict their career attainment in many organizational settings. For them, “being Americanized” at the workplace mean adopting the American way of “thinking,” “speaking,” “acting,” and “perspective,” rather than sharing the same music or food, or sports (e.g., a Simpsons reference or college football). They constantly looked out for way to improve themselves, take on new challenges, have new experiences, and have a bigger effect on their lives, not only adjusting themselves but also influencing others. As AB summarized:

That's really about the people management skill and the adaptability. You are able to change, but also you can be a change agent. When you take initiative, you need to be able to communicate change and also help people change to new competition, new process, new system, etc. I think that's all keys. (AB)

Study 1 discussion

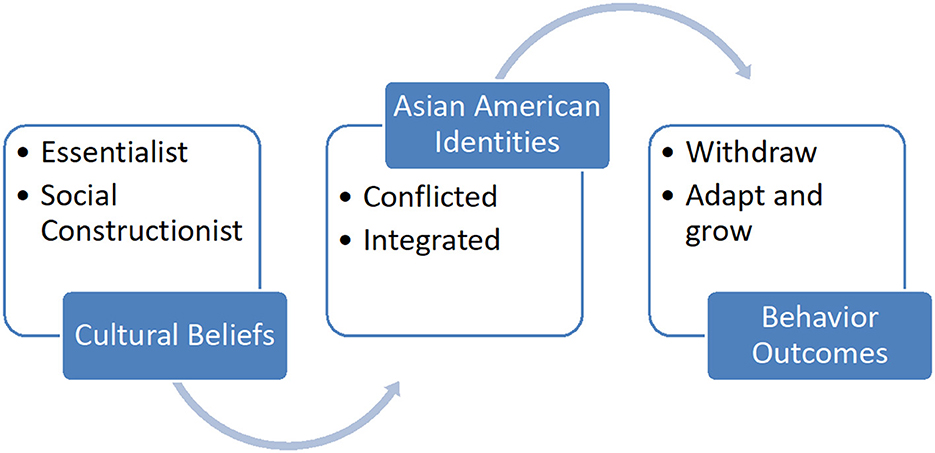

In Study 1, while we did not observe the “bamboo ceiling” situation in all of our interviewees, it is essential to acknowledge that our interviewees demonstrated diverse experiences in terms of career attainment. Although common themes emerged within each cultural viewpoint, such as essentialist and social constructionist perspectives, there were nuanced variations among individuals. Some participants, particularly those holding essentialist views, perceived their Asian identity as influencing their career progression. In contrast, those with social constructionist views often did not perceive their Asian identity as a significant factor, neither hindering nor facilitating their career advancement. This divergence highlights the complexity of how cultural perspectives interact with individual experiences, contributing to a range of perceptions and outcomes in career attainment among Asian Americans in our study. Overall, the themes that emerged from the qualitative data suggested that an essentialist belief in culture may contribute to a conflicted Asian American identity, potentially serving as a cognitive hurdle in the host cultural environment. This varied perception and cognitive impact, as illuminated by our participants, could be associated with diverse career outcomes and behavioral responses within the organizational context. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model emerged from the qualitative data. The relationship between cultural beliefs, Asian American identities, and behavior outcomes.

The two bodies of literature that related most to the qualitative data were that of cultural essentialism and bicultural identity integration. A limitation in Study 1 was that most of the interviewees came from Chinese cultural backgrounds. We designed Study 2 to address this limitation and to quantitatively testing the emerged relationship by recruiting participants from more diversified East Asian cultural groups. Based on the emerged themes in Study 1, Study 2 aimed to answer the now evolved specific research question: How do cultural essentialism and bicultural identities impact the career attainment of East Asian Americans? We conducted a literature review of the two frameworks, focusing on the possible explanations for the observed phenomenon from Study 1 and developed hypotheses for Study 2.

Study 2 literature review

Cultural essentialism

The concept of essentialism emerged from “lay theory,” which describes psychological phenomenon that individuals commonly understand and interpret racial/ethnic information and direct their behaviors in interracial/ethnic settings (Wegener and Petty, 1998; Hong et al., 2009). Laypeople's beliefs regarding the essential nature of social categories establish the mindsets through which individuals construct and interpret their social experiences (Hong et al., 2009). It reflects how people routinely think about, believe, and identify both social and non-social categories, such as race, ethnicity, or gender (Gelman and Wellman, 1991; Haslam et al., 2004). Lay beliefs lie along a continuum: At one end of this continuum, people with essential beliefs hold that different social groups represent unalterable traits and abilities as human natures; at the other end of this continuum, the social constructionists (non-essentialists) believe that social categories are arbitrary and malleable social constructions (Chao et al., 2007; Tadmor et al., 2013). Endorsement of the essentialism vs. the social constructionism are associated with different encoding and representation of social information, which affect feelings, motivation, and competence in navigating between racial and cultural boundaries (Hong et al., 2009).

With the rapid increase in intercultural contact, research on essentialism has drawn increasing attention in recent years and shows the impact of culture as a social category. An extension of essentialism, culture essentialism refers to people's common-sense understanding of culture, a belief that cultures have some underlying essence that influences how members of a culture behave (Fischer, 2011). Specifically, culture essentialism entails the belief that culture is a fixed and biological construct independent of human perception, vs. a social construct in which human perception plays a role (No et al., 2008). People's beliefs about culture can influence how they interpret and structure their experiences in a multicultural society, and impact their psychological processes when individuals must deal with two apparently discrete cultures (Chao and Kung, 2015). In the context of acculturation, individuals who believe in the essentialist theory of culture tend to adhere more rigidly to their ethnic culture; while individuals who believe a social constructionist theory of culture would assimilate more with the majority culture (No et al., 2008). Essentializing culture hinders bicultural individuals' navigation between cultures and can result in emotional stress when passing between cultures (Chao et al., 2007). Further, Tadmor et al. (2013) show that essentialist mindset induces a habitual closed-mindedness that reduces creativity. Culture essentialism has generally been regarded as a harmful cognitive process that results in stereotyping, prejudice and leads to intergroup biases, conflicts and hostilities (Levy et al., 2006; Dar-Nimrod and Heine, 2011; Chao et al., 2013). However, the negative outcome of cultural essentialism is also debatable (cf. Ryazanov and Christenfeld, 2018). Study showed that cultural essentialism can be associate with more open-mindedness as a personality characteristic and lead to more effective cultural sensitivity and learning (Fischer, 2011). Ryazanov and Christenfeld (2018) proposed that essentialism can be used as a strategy to reduce blame and contributes to identity, particularly when the underlying essence is perceived as good. The collective literature shows that the cultural essentialism is potentially context dependent. Depending on the situation, cultural essentialism can either facilitate cultural learning or inhibit intercultural interaction.

Research suggests that cultural essentialism, as a belief system, significantly influences individuals' thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (No et al., 2008; Tadmor et al., 2013). Moreover, the impact of cultural essentialism is highly contextual, depending on the situated environment of individuals (Pauker et al., 2020). Those endorsing essentialist beliefs tend to avoid intercultural interactions (Chao and Kung, 2015). This avoidance is more feasible for majority groups, like European Americans in the U.S., potentially lead to cultural racism or stronger stereotyping, and prejudice toward minority cultural groups (Verkuyten and Brug, 2004; Young et al., 2013; Bernardo et al., 2016). Conversely, for minority groups such as Asians living in the U.S., interaction with the majority group is inevitable due to their immersion in a cultural environment defined by the majority (Chao and Kung, 2015). Individuals who strongly endorse an essentialist view of culture tend to resist assimilating, maintain a rigid connection to their ethnic culture, and respond in ways typical of their own cultural norms (No et al., 2008). Therefore, in a multicultural work environment, East Asian Americans holding essentialist beliefs are likely less adaptive to the workplace's cultural dynamics and less willing to interact with people from other cultural backgrounds (Lu, 2022). Additionally, culture essentialism may also lead to a narrowed perspectives on career choices, causing individuals to overlook the full spectrum of their skills and abilities, and thus limit their opportunity for leadership positions and career attainment. Based on the above, we develop the follow hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Cultural essentialism will negatively predict East Asian American career attainment.

Bicultural identity integration

The other theme that emerged from the qualitative results is how the bicultural interviewees felt about their dual cultural identities. Biculturals are individuals who live “have been exposed to and have internalized more than one culture” (Huynh et al., 2018, p. 1581), resulting in the need to manage two different cultural identities. How different biculturals manage their dual cultural identities can be framed in terms of how compatible the two cultural identities are, also referred to as bicultural identity integration (BII; Benet-Martínez et al., 2002). BII is further separated into two facets: Blendedness and Harmony.1 Blendedness refers to how biculturals perceive their dual cultural identities as being compartmentalized or fused (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos, 2005), while Harmony refers to the degree of conflict biculturals feel between their two cultural identities (Miramontez et al., 2008). The primary findings of BII research show that BII moderates how biculturals respond to cultural stimulus in cultural priming studies (Benet-Martínez et al., 2002; Benet-Martínez and Haritatos, 2005; Cheng et al., 2006; Nguyen and Benet-Martínez, 2007; Mok and Morris, 2009; Mok et al., 2010). Individuals with higher levels of BII see their dual cultural identities as fused and harmonious and respond appropriately to cultural stimulus. An Asian American with high BII who is presented with Asian cultural stimulus behaves more Asian. Conversely, individuals with lower levels of BII see their dual cultural identities as separated and conflicting and respond contrastively to cultural stimulus. When presented with Asian cultural stimulus, an Asian American with low BII behaves more American instead. BII has also been shown to be correlated with various stress related outcomes, with high levels of BII correlated with lower levels of isolation and self-criticism (Fung et al., 2021), lesser perceived stress (Yim et al., 2019), lower levels of depression (Ho, 2013), and higher psychological adjustment during cross-cultural interactions (Chen et al., 2008).

Most of the BII research has focused on the moderating effects of Harmony. Less is known about the specific effects of Blendedness. However BII scholars have noted that the two facets possess distinct psychological antecedents (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos, 2005), and proposed that Blendedness is related to more performance-related aspects of biculturalism, while Harmony is related to more psychologically-related aspects (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos, 2005; Huff et al., 2017, 2020; Tikhonov et al., 2019).

Benet-Martínez and Haritatos (2005), drawing upon Yzerbyt et al. (2001), proposed that that biculturals holding more essentialist views of culture may perceive their dual cultural identities as separate. In other words, biculturals with stronger essentialist views tend to develop less integrated bicultural identities, potentially impacting their ability to effectively adapt in the host culture (cf. Benet-Martínez et al., 2002). This notion finds support in No et al. (2008) study, which revealed that essentialist East Asian Americans perceived less similarity in the personality profiles of Asian Americans and White Americans. Additionally, it aligns with findings from Miramontez et al. (2008), indicating that higher levels of Blendedness, but not Harmony, was associated with a higher level of perception of overlap in the personalities of Latinos/Mexicans and Anglo-Americans. Consequently, we hypothesize that higher levels of essentialism would predict lower levels of BII:

Hypothesis 2: Higher levels of cultural essentialism will relate to lower levels of BII.

In contrast, individuals holding social construction beliefs tend to perceive greater similarities between two cultures and consistently identify and assimilate toward their host culture (Chao et al., 2007; No et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009). This is congruent with discussions in bicultural literature on BII, which relates to how biculturals view their dual cultural identities as either compatible or incompatible (Benet-Martínez et al., 2002). Specifically, Nguyen and Benet-Martínez (2007) noted that research show biculturalism having a significant, moderate, and positive effect on sociocultural adjustment factors such as “academic achievement, career success, and social skills” (emphasis added; Nguyen and Benet-Martínez, 2012). Chen et al. (2008) similarly show that BII influences how biculturals adjust to the cultural environment around them. Given that biculturals with more essentialist views would be less integrated (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos, 2005), this may lead to unfavorable career outcomes for biculturals. In this context, BII acts as a mediator between cultural views and acculturation outcomes. In the present study, the acculturation adjustment outcome would be career attainment in a host culture, diverging from previous examinations that primarily investigated mental health outcomes (Tikhonov et al., 2019). Based on the observation, we propose the mediating role of BII:

Hypothesis 3: Bicultural Identity Integration will mediate the relationship between cultural essentialism and East Asian American career attainment.

Study 2 methodology

Participants

Participants for the quantitative Study 2 were obtained via a panel data provider. The panel company was asked to recruit East Asians working in a full-time position in the U.S. at a company with more than 50 employees. A simple power analysis indicated that in order to detect a conservatively small effect size, a sample size of around 600 participants would be required. A conservatively small effect size was estimated due to uncertainty regarding the effect size of the anticipated findings. A total of 478 responses were collected. After filtering out non-East Asian participants, participants who did not meet the employment requirements, incomplete responses, and participants who failed attention checks, 338 responses remained. Although this sample size was below that originally estimated for a small effect size, we proceeded with data analysis due to a lack of further funding necessary to attain the full estimated sample size. There was also the possibility that the original sample size estimate was overly conservative, and that the effect size would be larger than expected.

For the ethnicities of the participants, 218 (63.7%) self-identified as Asian American, 99 (9.6%) as Chinese, 33 (9.6%) as Japanese, 31 (9.1%) as Korean, and 7 (17.13%) as Other Asian. In terms of sex, 50% of the participants self-identified as male and 50% self-identified as female. The mean age of the sample population was 40.37 years old (SD = 10.87). For education, 10.4% of the participations had obtained a doctorate or other post graduate degree, 34.3% had obtained a master's degree, 43.8% a 4-year degree, with the remaining 11.5% having obtained a 2-year degree or less. Most of the participants were second generation immigrants (38.5%), followed by first generation (28.7%), 1.5 generation (21.3%), and third generation and beyond (11.5%).

Study 2 procedures and measures

All participants completed the surveys online at times and locations of their convenience. No additional incentives were provided to participants for completing the study materials beyond what participants were paid for in accordance with their agreement with the panel company. The surveys presented to the participants are as follows, with each participant receiving the surveys in randomized order.

Career attainment

Participants were first asked questions regarding their employment background. This included questions such as their current position and industry. Participants were also asked to indicate their current salary and the number of times they have been promoted (Seibert et al., 1999). The current salary and the number of promotions received over a given participant's entire career were used as the primary dependent variables of interest for this study. Promotions was measured by the number of times participants have been promoted in their entire careers. Salary was measured using a 12-point Likert scale, with 1 being “Less than $10,000” and 12 being “More than $150,000.”

Cultural essentialism

Participants then filled out a scale to assess their cultural essentialism. The scale was adopted from No et al. (2008), which was validated on Asian American samples. This is a 7-point Likert scale consisting of two sub-scales, one for assessing essentialist views, with items such as “Although a person can adapt to different cultures, it is hard if not impossible to change the dispositions of a person's culture” (4 items, α = 0.84), and one for assessing social constructionist views, with items such as “Cultures are just arbitrary categories and can be changed if necessary” (4 items, α = 0.81).

Because lay beliefs lies along a continuum, the social constructionist subscale items were reversed scored and an overall cultural essentialism score was calculated by averaging the reversed social constructionist items and the essentialist items, as originally developed and used by No et al. (2008). The resulting values reflected participants' relative endorsement of essentialist views of culture above those of the social constructionist views of culture. The higher the score, the more the participants endorse an essentialist view of culture. The overall culture essentialism score was then used for further statistical analysis in this study.

Bicultural identity integration

In order to assess the bicultural identity integration of the participants, the Bicultural Identity Integration Scale-2 (BIIS-2; Huynh et al., 2018) was used. The BIIS-2 is a 5-point Likert scale consisting of two subscales, Blendedness and Harmony. The Blendedness subscale includes items such as “I feel Asian and American at the same time” and “I find it difficult to combine Asian and American cultures” (9 items, α = 0.88). The Harmony subscale includes items such as “I find it easy to harmonize Asian and American cultures” and “I feel that my Asian and American cultures and complementary” (9 items, α = 0.82). As the BIIS-2 as designed consists of two subscales, each of which assess “two different and psychometrically independent components” (Nguyen and Benet-Martínez, 2007), analysis was conducted using each subscale independently.

Behavioral acculturation

The participants' acculturation levels, and biculturalism, were also assessed in order to serve as control variables, given the effect of acculturation on career outcomes (Reynolds and Constantine, 2007). We adopted Tsai et al.'s (2000) General Ethnicity Questionnaire (GEQ) for this study. The GEQ is a 39-item, 5-point general behavioral Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) measure of acculturation that can be tailored to the culture of interest, and has been used by Tsai and colleagues to examine acculturation behavior of Asian and American cultures, with items such as “I listen to American [Asian] music,” and “I celebrate American [Asian] holidays” (GEQ-American, α = 0.91, GEQ-Asian, α = 0.90). All participants filled out two versions of the GEQ: American and Asian, presented in randomized order.

Demographics background

At the conclusion of the data collection, participants were asked to complete a demographics questionnaire designed primarily to collect information about the cultural background of the participants, and included such questions as sex, age, immigration generation, languages spoken, and current location by state.

Study 2 results

Self-reported acculturation measures indicate that the participants in Study 2 were more acculturated in American culture (M = 3.57, SD = 0.54) than Asian culture (M = 3.40, SD = 0.52), t(337) = 3.76, p < 0.05, Cohen's d = 0.31. The different levels of acculturation are in line with results from past uses of the GEQ (Tsai et al., 2000; Miramontez et al., 2008; Wan et al., 2019), which also discovered significantly differing levels of acculturation amongst biculturals in host cultures. Participants received on average 3.2 promotions over their careers, with salaries averaging $70,000 to $79,000. The correlations for study variables, along with the means and standard deviations for each, are presented in Table 3. The relatively low correlations between study variables indicated good discriminant validity, further reinforced by an analysis of the hterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratios of study constructs per Henseler et al. (2015). A common latent variable analysis using SEM (cf. Podsakoff et al., 2003) also did not meet the threshold of concern for common method variance.

Table 3. Observed correlations, means, and standard deviations of variables in the quantitative study.

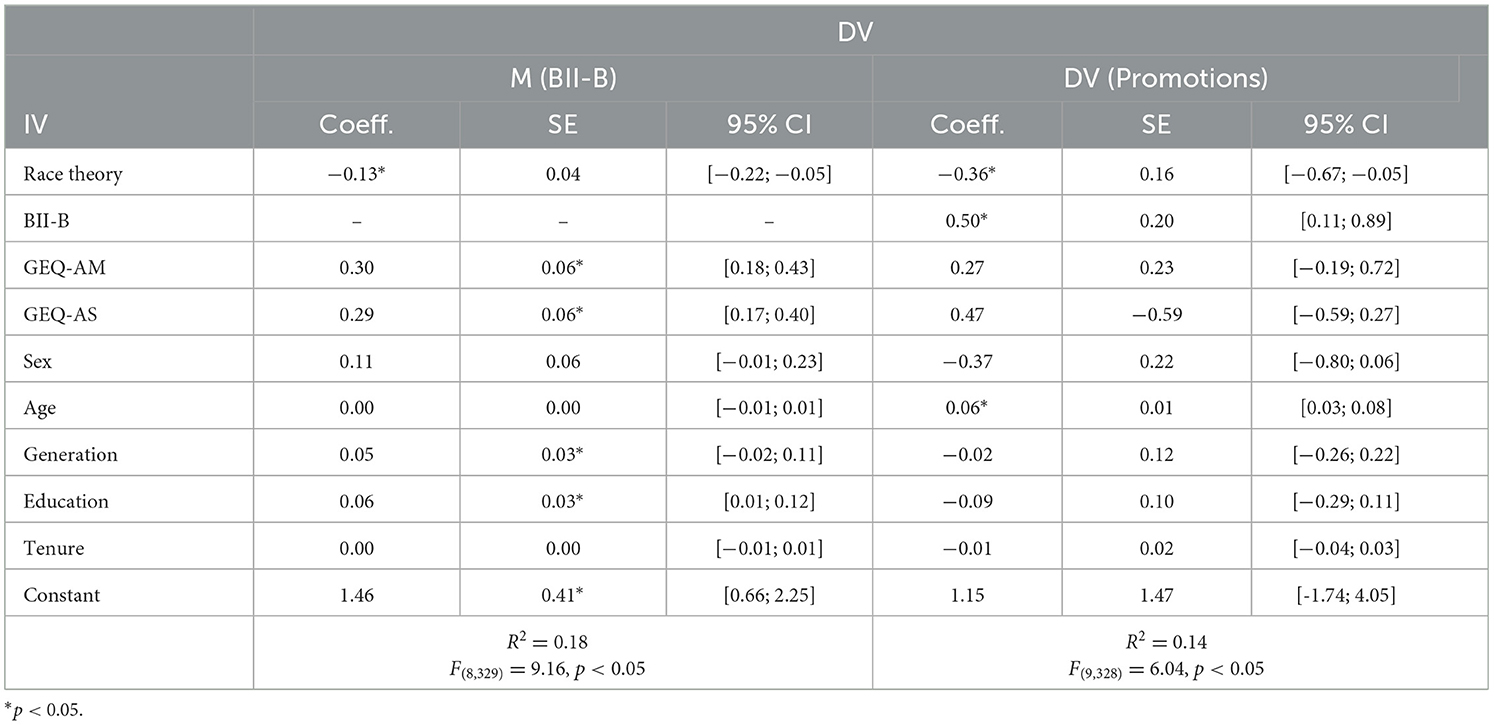

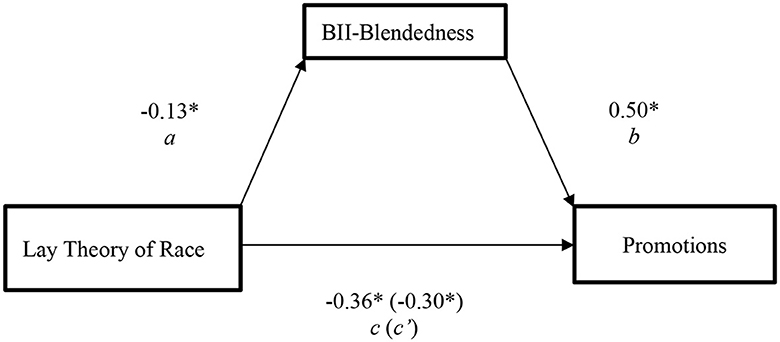

In order to test for the direct and indirect effects to determine mediation, Preacher and Hayes' PROCESS bootstrapping method was used, using a bootstrap sample size of 5,000. PROCESS is a path based analytical tool for SPSS and SAS that can be used for mediation analysis (Hayes et al., 2017). Analysis was conducted while controlling for factors that could have an effect on career outcomes: acculturation, age, sex (cf. Goldberg et al., 2004), level of education (Lerman, 2000), immigration generation (Fitzsimmons et al., 2020), and job tenure; however this did not materially change the results. As seen in Table 4 and Figure 2, participants who had higher levels of cultural essentialism also had lower levels of BII-Blendednness (a = −0.13), supporting Hypothesis 1, and participants who had higher levels of BII-Blendedness also received more promotions in their careers (b = 0.50). Participants who had higher levels of cultural essentialism also had received less promotions in their careers independent of its effect on BII-Blendedness (c' = 0.30). Therefore, BII-Blendedness partially mediated the relationship between cultural essentialism and number of promotions received. However, there was no significant effect for salary received even after controlling for different states where the participants resided in. Additionally, no significant effect was found for Harmony. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported. Figure 2 depicts the mediation model and the coefficients for each path.

Figure 2. Regression coefficients for the relationship between lay theory of race and number of promotions as mediated by BII-Blendedness. The regression coefficient between lay theory of race and number of promotions, controlling for BII-Blendedness, is in parentheses. *p < 0.05.

Discussion of findings

Using a sequential mixed-method, this study sought to discover the possible individual-level psychological factors that contribute to some East Asian Americans breaking through the bamboo ceiling. While the findings are straightforward, there are several implications which we will discuss below, along with the limitations and future research direction for each implication.

Primary findings

The combined findings suggest that participants who viewed the cultural differences between their ethnic and the host cultures as fixed and insurmountable received less promotions, and this relationship was mediated by whether they viewed their two cultural identities overlapping. Our review of the current literature earlier suggests that individuals with higher levels of cultural essentialism would also perceive greater distance between their bicultural identities (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos, 2005), which in turn would lead to decreased career attainment in the host culture (Nguyen and Benet-Martínez, 2012). This could also be described as follows: In a multicultural working environment, participants' “mindset” regarding culture could influence the “perception” of their bicultural identity, leading to distinct “behaviors” when switching between different cultural frames.

That salary as a dependent variable did not result in significant findings is acknowledged as one of the limitations of this study. This may be due to variance in the data pertaining to geographical location, industry, and employee position. Given that salary and compensation are greatly influenced by the aforementioned variables, it is therefore likely that results would not be found without further subgroup analysis or refinement of the collected data. However, the current sample size, and the quality of responses given for job title and industry, did not allow for such analysis, and is acknowledged as a limitation of this study.

Theoretical contributions

This study contributes to the understanding of cultural essentialism in the context of career progress for Asian Americans in a multicultural work environment. Prior literature on cultural essentialism shows the negative impact of essentialism on individual's stereotyping, prejudice which leads to intergroup biases, conflicts and hostilities (Levy et al., 2006; Dar-Nimrod and Heine, 2011; Chao et al., 2013). Our study demonstrates that cultural essentialism can pose a potential barrier to career attainment for Asian American in multicultural work environments. The impact of essentialism goes beyond influencing individuals' career choices and paths to conform to cultural norms; it can also restrict their ability to fully express their unique skills, perspectives, and potential, ultimately limiting their opportunities for career attainment. Further, by examining the role of cultural essentialism for Asian Americans as biculturals, this study expands our understanding of how essentialist beliefs can manifest in different contexts and affect individuals' behavior and career outcomes. Our findings provide an alternate explanation for Asian American who overcame the Bamboo Ceiling: their view of culture as a social construct may enable them to be more flexible in adapting to their environment. Rather than feeling constrained by cultural expectations, they may be more willing to explore diverse means of personal and professional growth to achieve their full potential.

The findings from this study additionally contribute to BII literature in several ways. The first is that we provide empirical evidence to support the previously proposed relationship between essentialism and BII (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos, 2005). Specifically, Benet-Martinez and Haritatos have suggested that the primary psychological mechanism at play is that biculturals with higher levels of essentialism perceive the boundaries between cultures as more rigid. This perception, in turn, makes them less open to incorporating new elements into their cultural identity. While this specific proposed mechanism has not been examined in depth, Moftizadeh et al. (2021) showed that more essentialized view of cultural identities lead to the perception that majority and minority cultures are mutually exclusive. That is, individuals with higher levels of essentialism would perceive that the two cultures could not coexist, with the adaptation of one culture necessitating the forgoing of the other. Although Moftizadeh et al. (2021)'s findings were limited to examining minority members (specifically Somalis) in British society, the fact that their results are similar to those of the current study provides initial empirical support for Benet-Martinez and Haritatos's proposal.

The current study further informs BII literature due to the differential findings between Blendedness and Harmony. That is, significant results were obtained for BII-Blendedness, but not BII-Harmony. Previous literature had noted that Blendedness has been shown to relate to more performance-related aspects of biculturalism, or how biculturals perform as biculturals, while Harmony relates to more psychologically-related aspects of biculturalism, or how biculturals feel about being bicultural (Benet-Martínez and Haritatos, 2005; Huff et al., 2017, 2020; Huynh et al., 2018; Tikhonov et al., 2019). This interpretation is supported by the results from Study 2, which indicated that Blendedness, but not Harmony, had a mediation effect. These findings suggest that the dependent variables of interest in the current study more accurately reflect a bicultural's performative aspects rather than their emotional state. This study advances BII research by introducing a novel approach—employing BII as a mediator, rather than an independent or moderating variable in most prior studies. Moreover, our contribution extends to the empirical examination of Blendedness, a facet less explored in existing BII studies that has predominantly concentrated Harmony.

Practical recommendations

Although it is possible to interpret the results of this study as an argument in favor of cultural minorities eschewing their own ethnic and cultural identities to obtain career attainment, we strongly caution against such interpretations. First and foremost, this study seeks to explain why some East Asian Americans achieved career attainment while others did not. As such, we emphasize that the results should not be seen as dictating how members of cultural minority should behave but rather as an analysis of individual level distinctions in the current socio-cultural context. The distinct outcomes for essentialist and social constructionist are crucial for efforts to advance East Asian Americans' careers and to increase organizational inclusiveness. In another words, this study does not advocate that Asian Americans give up their Asian identity and culture in order to succeed more in the U.S., but rather that Asian Americans maintain flexible identities in order to react in manners consistent with their cultural environment. We would also like to emphasize that Study 1 interviewees who advanced in their career did not become fully assimilated, meaning they maintained their ethnic and cultural identities. They continued to have a strong connection with their Asian social networks and still appreciated food, music, or movies from their home culture. However, they were able to adapt to many cultural situations thanks to their social constructionist stance, which allowed for a more fluid and blended bicultural identity.

Here it would be important to consider biculturals' contribution to intercultural interactions. Given the ability of biculturals to navigate between cultures, they could play a valuable role as cultural brokers between organizations and institutions that systematically impede minority achievement. Furthermore, because biculturalism has also been shown to buffer against certain forms of racism and acculturation stress (Nguyen and Benet-Martínez, 2007; Marks et al., 2022), biculturals may be better able to maintain their motivation to succeed in the face of societal obstacles while also acting as change agents to alter the cultural/racial ideology of the organization (cf. Vázquez-Montilla et al., 2012). Individually, cultural minorities can concentrate what they can control, possibly influence and transform their working surroundings, and promote an inclusive organizational culture.

Finally, we note that there are various factors that influence an individual's career attainment, including societal barriers, organizational structural challenges, and mentorship relations. Therefore, the insights derived from this study should not be utilized in isolation but rather as integral components of a broader DEI initiative.

Recommendations for organizations

This understanding can be valuable for companies seeking to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in their workplace and upper management. Given that essentialism is linked to diversity ideologies (Bernardo et al., 2016), organizations may examine their diversity programs aiming to foster intercultural interactions to increasing openness to other cultures and cultural intelligence, rather than to disregard or focus on cultural differences (Cho et al., 2018). Organization could also leverage the strength of integrated biculturals as cultural brokers and change agent to drive an organizational cultural embracing DEI. We believe an organization environment encouraging intercultural interactions will result in the desired outcome of organizational inclusiveness for employee development and growth.

Limitations and future research

Due to the correlational nature of the data, our study supports the negative association between essentialism and career attainment for cultural minorities but does not prove a causal relationship. Longitudinal studies can be utilized in future research to better examine causality. Additionally, the relationship between the variables may be reversible because social essentialism is contextual and can change as a result of personal experience or education (Pauker et al., 2020). As a result, less career attainment for cultural minorities may lead to a deeper belief of cultural essentialism. Nevertheless, more research is required before a reverse causal relationship can be established because current literature has not thoroughly examined how essentialism develops past early childhood and because ongoing research may identify various aspects of racial essentialism, some which may change in response to education while others may not (Tawa, 2020; Tawa et al., 2020).

Our qualitative data also provided rich insights to further examine other possible factors, such as gender, work environment diversity, and mentors, that can affect the career attainment of cultural minorities. Statements from several of the interviewees in particular demonstrated that gender might play a more prominent role in career growth in traditionally male dominated information technology fields. However, this sentiment was not shared by all interviewees and would warrant further research. In a similar vein, a further difference that merits closer examination is that, while some interviewees indicated that mentors had played an important role in navigating their career growth, others made no mention of mentors and seemed to have relied heavily on themselves.

Last, our study is the restriction of sample recruitment to East Asians in the U.S., preventing generalizability to other immigrant populations. The combined findings from the two studies suggest that East Asian Americans who view of culture as unchanging and who, as a result, have less integrated bicultural identities may have limited opportunities for career attainment in the host culture. This is especially important in light of the results. Future research should investigate whether similar phenomena exist among other immigrant populations in the U.S., especially given that the term “Asian American” can encompass a wide range of diverse ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Our exploration of “bamboo ceiling” establishes the relationship between cultural essentialism, bicultural identity integration, and career outcomes of East Asian Americans. We demonstrate that East Asian Americans who have less cultural essentialism have more integrated bicultural identities are more likely to achieve their career goals and attainment. With the increasing culturally mixed environment, we hope our study will stimulate interest in exploring the critical implications of cultural essentialism on intercultural interactions. The following from Hyun's initial exploration of the bamboo ceiling best summarizes the primary takeaway message for our findings:

“As an Asian American, it's your responsibility to take charge of your career. […] They have nothing to do with undermining your cultural values and everything to do with operating flexibly in a competitive work environment.”

Jane Hyun, Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Farmingdale State College Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because interview questions may have potentially involved sensitive information regarding workplace practices and discrimination. Signed informed consent would have provided a link between the participant's identity and the study. Therefore a waiver of documentation of consent was requested, granted, and oral consent was obtained instead.

Author contributions

AC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Data collection for this study was financially support by Farmingdale State College's Summer Scholarship Support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Different bicultural scholars use different terms for the same two facets: Distance/Blendedness, or Conflict/Harmony. For the sake of consistency, throughout this paper we will refer to the two facets as Blendedness and Harmony.

References

Benet-Martínez, V., and Haritatos, J. (2005). Bicultural identity integration (BII): components and psychosocial antecedents. J. Person. 73, 1015–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00337.x

Benet-Martínez, V., Leu, J., Lee, F., and Morris, M. W. (2002). Negotiating biculturalism: Cultural frame switching in biculturals with oppositional versus compatible cultural identities. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 33, 492–516. doi: 10.1177/0022022102033005005

Benson, G. S., McIntosh, C. K., Salazar, M., and Vaziri, H. (2020). Cultural values and definitions of career success. Hum. Resour. Manage. J. 30, 392–421. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12266

Bernardo, A. B., Salanga, M. G. C., Tjipto, S., Hutapea, B., Yeung, S. S., and Khan, A. (2016). Contrasting lay theories of polyculturalism and multiculturalism: associations with essentialist beliefs of race in six Asian cultural groups. Cross-Cult. Res. 50, 231–250. doi: 10.1177/1069397116641895

Cai, H., Sedikides, C., Gaertner, L., Wang, C., Carvallo, M., Xu, Y., et al. (2011). Tactical self-enhancement in China: Is modesty at the service of self-enhancement in East Asian culture? Soc. Psychol. Person. Sci. 2, 59–64. doi: 10.1177/1948550610376599

Catalyst (2003). Advancing Asian women in the workplace: What managers need to know. Catalyst. Available online at: https://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/advancing-asian-women-workplace-what-managers-need-know (accessed September 25, 2018).

Chao, M. M., Chen, J., Roisman, G. I., and Hong, Y-Y. (2007). Essentializing race: implications for bicultural individuals' cognition and physiological reactivity. Psychol. Sci. 18, 341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01901.x

Chao, M. M., Hong, Y., and Chiu, C. (2013). Essentializing race: its implications on racial categorization. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 104:619. doi: 10.1037/a0031332

Chao, M. M., and Kung, F. Y. (2015). An essentialism perspective on intercultural processes. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 18, 91–100. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12089

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. New York: Sage.

Chen, S. X., Benet-Martínez, V., and Harris Bond, M. (2008). Bicultural Identity, bilingualism, and psychological adjustment in multicultural societies: immigration-based and globalization-based acculturation. J. Person. 76, 803–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00505.x

Cheng, C.-Y., Lee, F., and Benet-Martínez, V. (2006). Assimilation and contrast effects in cultural frame switching: Bicultural identity integration and valence of cultural cues. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 37, 742–760. doi: 10.1177/0022022106292081

Cho, J., Tadmor, C. T., and Morris, M. W. (2018). Are all diversity ideologies creatively equal? The diverging consequences of colorblindness, multiculturalism, and polyculturalism. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 49, 1376–1401. doi: 10.1177/0022022118793528

Corley, K. G., and Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Admin. Sci. Quart. 49, 173–208. doi: 10.2307/4131471

Dar-Nimrod, I., and Heine, S. J. (2011). Some thoughts on essence placeholders, interactionism, and heritability: Reply to Haslam (2011) and Turkheimer (2011). Psychol. Bull. 137, 829–833. doi: 10.1037/a0024678

Fehrenbacher, D., Roetzel, P. G., and Pedell, B. (2018). The influence of culture and framing on investment decision-making: the case of Vietnam and Germany. Cross Cult. Strat. Manage. 25, 763–780. doi: 10.1108/CCSM-10-2017-0139

Fischer, R. (2011). Cross-cultural training effects on cultural essentialism beliefs and cultural intelligence. Int. J. Interc. Relat. 35, 767–775. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.005

Fitzsimmons, S. R., Baggs, J., and Brannen, M. Y. (2020). Intersectional arithmetic: How gender, race and mother tongue combine to impact immigrants' work outcomes. J. World Bus. 55:101013. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101013

Fung, J., Lin, C., and Joo, S. (2021). Factors associated with burnout, marital conflict, and life satisfaction among Chinese American church leaders. J. Psychol. Theol. 50, 276–291. doi: 10.1177/00916471211011594

Gee, B., and Peck, D. (2015). Scant Progress for Minorities in Cracking the Glass Ceiling From 2007-2015. New York, NY: Ascend Foundation.

Gee, B., Peck, D., and Wong, J. (2015). Hidden in Plain Sight: Asian American Leaders in Silicon Valley. New York, NY: Ascend Foundation.

Gelman, S. A., and Wellman, H. M. (1991). Insides and essences: early understandings of the non-obvious. Cognition 38, 213–244. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(91)90007-Q

Glaser, B.G. (1992). Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis: Emergence vs Forcing. London: Sociology Press.

Goldberg, C. B., Finkelstein, L. M., Perry, E. L., and Konrad, A. M. (2004). Job and industry fit: The effects of age and gender matches on career progress outcomes. J. Organiz. Behav. 25, 807–829. doi: 10.1002/job.269

Haslam, N., Bastian, B., and Bissett, M. (2004). Essentialist beliefs about personality and their implications. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 30, 1661–1673. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271182

Hayes, A. F., Montoya, A. K., and Rockwood, N. J. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Austral. Market. J. 25, 76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

Hechler, D. (2011). NAPABA helps Asian-American lawyers beat stereotypes while expanding skills. Corporate Counsel. Available online at: http://www.corpcounsel.com/id=1202491095475/NAPABA-Helps-AsianAmerican-Lawyers-Beat-Stereotypes-While-Expanding-Skills (accessed February 28, 2013).

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Ho, J.C.-C. (2013). Associations of bicultural identity integration with psychological well-being and cortisol responses to a laboratory stressor. Thesis. University of California, Irvine. doi: 10.1037/e512142015-857

Hong, Y., Chao, M. M., and No, S. (2009). Dynamic interracial/intercultural processes: the role of lay theories of race. J. Person. 77, 1283–1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00582.x

Huff, S. T., Lee, F., and Hong, Y. (2017). Bicultural and generalized identity integration predicts interpersonal tolerance. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 48, 644–666. doi: 10.1177/0022022117701193

Huff, S. T., Saleem, M., and Rivas-Drake, D. (2020). Examining the role of majority group attitudes and bicultural identity integration on bicultural students' behavioral responses toward White Americans. Cult. Diver. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 26, 149–162. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000284

Huynh, Q.-L., Benet-Martínez, V., and Nguyen, A.-M. D. (2018). Measuring variations in bicultural identity across U.S. ethnic and generational groups: development and validation of the Bicultural Identity Integration Scale - Version 2 (BIIS-2). Psychol. Assess. 30, 1581–1596. doi: 10.1037/pas0000606

Hyun, J. (2006). Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling: Career Strategies for Asians. New York: HarperCollins.

Kawahara, D. M., Pal, M. S., and Chin, J. L. (2013). The leadership experiences of Asian Americans. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 4:240. doi: 10.1037/a0035196

Lee, J., and Zhou, M. (2014). The success frame and achievement paradox: the costs and consequences for Asian Americans. Race Soc. Problems 6, 38–55. doi: 10.1007/s12552-014-9112-7

Lerman, R. I. (2000). ‘Improving Career Outcomes for Youth: Lessons from the U.S. and OECD Experience'. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Levy, S. R., Chiu, C., and Hong, Y. (2006). Lay theories and intergroup relations. Group Proc. Intergroup Rel. 9, 5–24. doi: 10.1177/1368430206059855

Lu, J. G. (2022). A social network perspective on the Bamboo Ceiling: ethnic homophily explains why East Asians but not South Asians are underrepresented in leadership in multiethnic environments. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 122, 959–982. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000292

Lu, J. G. (2023). Asians don't ask? Relational concerns, negotiation propensity, and starting salaries. J. Appl. Psychol. 108, 273–290. doi: 10.1037/apl0001017

Lu, J. G., Nisbett, R. E., and Morris, M. W. (2020). Why East Asians but not South Asians are underrepresented in leadership positions in the United States. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 117, 4590–4600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918896117

Lu, J. G., Nisbett, R. E., and Morris, M. W. (2022). The surprising underperformance of East Asians in US law and business schools: The liability of low assertiveness and the ameliorative potential of online classrooms. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 119:e2118244119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2118244119

Marks, L. R., Yeoward, J., Fickling, M., and Tate, K. (2022). The role of racial microaggressions and bicultural self-efficacy on work volition in racially diverse adults. J. Career Dev. 49, 311–325. doi: 10.1177/0894845320949706

Markus, H. R., and Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 98:224. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.98.2.224

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. New York: Sage.

Miramontez, D. R., Benet-Martínez, V., and Nguyen, A.-M. D. (2008). Bicultural identity integration and self/group personality perceptions. Self Ident. 7, 430–445. doi: 10.1080/15298860701833119

Moftizadeh, N., Zagefka, H., and Mohamed, A. (2021). Essentialism affects the perceived compatability of minority culture maintenance and majority culture adoption preferences. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 60, 635–652. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12421

Mok, A., Cheng, C.-Y., and Morris, M. W. (2010). Matching versus mismatching cultural norms in performance appraisal: effects of the cultural setting and bicultural identity integration. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 10, 17–35. doi: 10.1177/1470595809359584

Mok, A., and Morris, M. W. (2009). Cultural chameleons and iconoclasts: assimilation and reactance to cultural cues in biculturals' expressed personalities as a function of identity conflict. J. Exper. Soc. Psychol. 45, 884–889. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.04.004

Monte, L. M., and Shin, H. B. (2022). Broad Diversity of Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander Population, The Census Bureau. Available online at: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/05/aanhpi-population-diverse-geographically-dispersed.html (accessed January 3, 2024).

Mosenkis, J. (2010). Finding the Bamboo Ceiling: Understanding East Asian Barriers to Promotion in US Workplaces. Doctoral dissertation. The University of Chicago.

Nguyen, A.-M. D., and Benet-Martínez, V. (2007). Biculturalism unpacked: components, measurement, individual differences, and outcomes. Soc. Person. Psychol. Compass 1, 101–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00029.x

Nguyen, A.-M. D., and Benet-Martínez, V. (2012). Biculturalism and adjustment: a meta-analysis. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 44, 122–159. doi: 10.1177/0022022111435097

No, S., Hong, Y. Y., Liao, H.-Y., Lee, K., Wood, D., and Chao, M. M. (2008). Lay theory of race affects and moderates Asian Americans' responses toward American culture. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 95:991. doi: 10.1037/a0012978