Abstract

V-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF) kinase, which was encoded by BRAF gene, plays critical roles in cell signaling, growth, and survival. Mutations in BRAF gene will lead to cancer development and progression. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), BRAF mutations commonly occur in never-smokers, women, and aggressive histological types and accounts for 1%–2% of adenocarcinoma. Traditional chemotherapy presents limited efficacy in BRAF-mutated NSCLC patients. However, the advent of targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have greatly altered the treatment pattern of NSCLC. However, ICI monotherapy presents limited activity in BRAF-mutated patients. Hence, the current standard treatment of choice for advanced NSCLC with BRAF mutations are BRAF-targeted therapy. However, intrinsic or extrinsic mechanisms of resistance to BRAF-directed tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) can emerge in patients. Hence, there are still some problems facing us regarding BRAF-mutated NSCLC. In this review, we summarized the BRAF mutation types, the diagnostic challenges that BRAF mutations present, the strategies to treatment for BRAF-mutated NSCLC, and resistance mechanisms of BRAF-targeted therapy.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality in China (1). Lung cancer could be divided into non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC); of these, approximately 60% of NSCLC were adenocarcinoma (2). Generally, about 80% of lung adenocarcinoma harbors driver mutations in east Asians (3). Over the past decades, targeted therapies have dramatically revolutionized the treatment pattern of NSCLC and greatly improved the prognosis of NSCLC patients.

V-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF) gene encodes BRAF kinase, a member of mammalian cytosolic serine/threonine kinases, which plays important roles in cell signaling, growth, and survival (4–6). BRAF mutations are rare mutations in NSCLC, which account for 2% of lung adenocarcinoma, and more frequently occur in never-smokers, women, and aggressive histological types (micropapillary) (7). Additionally, BRAF V600E mutations are mostly mutually exclusive with most druggable abnormalities present in this tumor (8, 9). It should be noted that certain BRAF mutations can coexist with KRAS mutations (9). However, routine platinum-based chemotherapy presents lower efficacy and is associated with poorer survival (10). Currently, the advent of BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has transformed the landscape of BRAF-mutated NSCLC. In the present review, we will discuss BRAF biology within the context of oncogenesis. In addition, we will describe the evolving science of molecularly targeted therapies and ICIs for BRAF-dependent cancers.

BRAF Mutations in Cancer

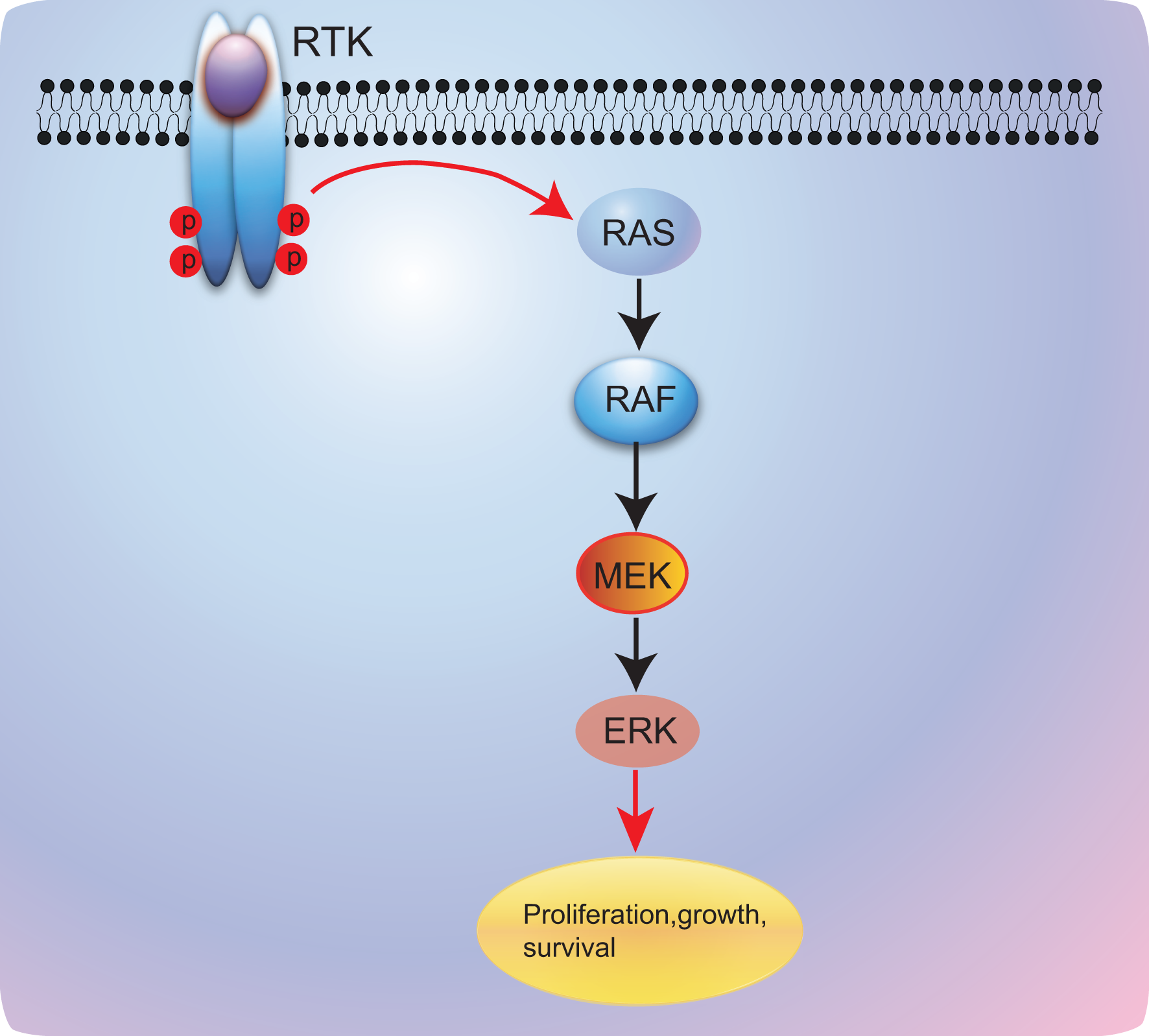

BRAF is involved in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway that includes the rat sarcoma (RAS)–rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF)–mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK)–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) mitogen-activated protein kinase. After activation of epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR), RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK pathway will be activated and modulate cell proliferation and survival (11) (Figure 1). In normal tissue, the BRAF kinase is generally silenced via negative feedback once the signal has moved on to the next point in the cascade. However, when BRAF mutations occur, the activation of the RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK pathway will be sustained and will lead to uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation; this makes BRAF mutations potential oncogenic drivers (12, 13). Generally, BRAF mutations commonly present in human cancers with an 8% incidence in all human cancers, predominantly in hairy cell leukemia (100%) (14), melanoma tumors (40%–50%) (15–17), thyroid carcinoma (10%–70%, based on the histologic classification) (18, 19), colorectal cancer (10%) (20, 21), and rarely in lung cancer (1%–2%) (11, 22).

Figure 1

RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway. RTK, receptor tyrosine kinase; RAS, rat sarcoma; RAF, v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase.

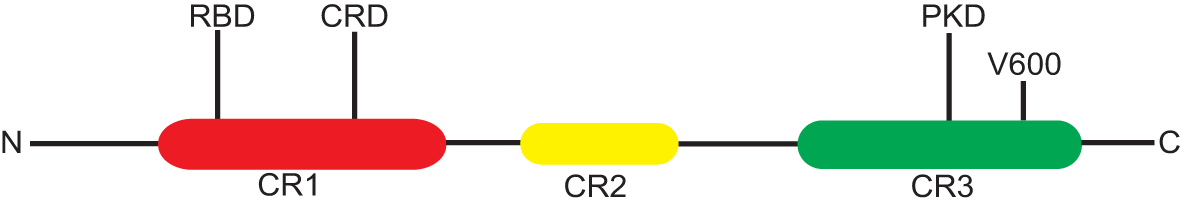

BRAF mutations could be divided into three classes based on mutation site. Class I mutants including V600E/K/D/R, which occurs in the valine residue at amino acid position 600 of exon 15, promote constitutive activation of MAPK pathway, causing strong activation of BRAF kinase; in addition, this type of mutations often presents high sensitivity to BRAF and MEK inhibitors (23, 24). Class II mutants, including K601, L597, G464, and G469 mutations, are located in the activation segment or P-loop and signal as RAS-independent dimers (24, 25).

Class III mutants that occur in the P-loop, catalytic loop, or DFG motif have impaired BRAF kinase activity; however, the activity of MAPK pathway signaling is enhanced via Raf-1 proto-oncogene CRAF activation (Figure 2) (24). All the class II and III mutations are non-V600 mutations, and BRAF mutations are usually classified as V600 mutations and non-V600 mutations in routine clinical practice. Actually, approximately 50% of BRAF mutations in NSCLC are non-V600 mutations (26–28). In addition, class II and III BRAF mutations are sensitive to current BRAF inhibitors; hence, novel-generation BRAF inhibitors warrant being developed.

Figure 2

The structure of BRAF gene. N, C, amino and carboxyl end; RBD, Ras-binding domain; CR, conserved region; CRD, cysteine-rich domain; PKD, protein kinase domain; CR1/2/3; conserved region-1/2/3, CR1 contains RBD and CRD, V600E mutation occurs in CR3.

BRAF Deletion Mutations

Several previous studies have demonstrated that BRAF deletion mutations can occur in melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and thyroid cancer; in addition, activating BRAF deletion mutations might serve as a type of resistance mechanism to BRAF inhibitors plus MEK inhibitors (29–31). Generally, deletion mutations happen adjacent to the αC helix in the kinase domain of BRAF, resulting in enhanced kinase activity by suppressing the αC helix in its active conformation (29). This type of BRAF mutation is similar to class I mutants functioning as RAS-independent monomers (31).

BRAF Fusions

At least 18 different 5´ fusion partners have been found across different cancer types including NSCLC, and the most common fusion partner is AGK in NSCLC (13, 32). The occurrence rate of BRAF fusions is smaller than 1% in NSCLC, and all NSCLCs with BRAF fusions were adenocarcinomas or NSCLC with adenocarcinoma features. Most BRAF fusion patterns are in-frame with breakpoints on the BRAF kinase domain (13, 32). In addition, remarkably, conserved fusions have been reported to occur in 85% of astrocytic pilocytomas (33). Activating BRAF fusions occur in truncation of the N-terminal CR1 auto-inhibitory domain, leading to the constitutive activation of BRAF pathway that resembles class II BRAF mutants (34). Up to now, limited data have revealed the activities of BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors in treating BRAF fusion mutations.

Detection of BRAF Mutations

Single-gene assays for BRAF mutations are extensively used across other cancer types including melanoma. The most commonly used assay is RT-PCR. So far, the cobas 4800 BRAF V600 Mutation Test and THxID-BRAF kit are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved companion diagnostic tests (35–37). In addition, laboratory-developed tests also could be applied to test a patient’s BRAF mutation status, although confirmatory tests via other methods are necessary. The major advantages of RT-PCR are faster turnaround time, better reproducibility, higher specificity and sensitivity, and lower cost compared with multiple gene sequencing methods. However, most of these methods are merely for BRAF V600E mutation located in exon 15. They lack the ability to detect exon 11 mutations that also are seen in NSCLC (38). Hence, next-generation sequencing (NGS) including a multiple gene panel should be applied to evaluate V600E mutation and non-V600E mutations that could happen in exon 11 and exon 15 (15, 26).

The other kind of single-gene test is immunohistochemistry (IHC) for BRAF mutations. However, the only available antibody used in IHC for mutant BRAF protein is monoclonal antibody VE1. The advantage of this method is to identify a qualitative change (i.e., the presence or absence of the protein), but the accuracy is limited in quantitating changes in expression than other antibody-based assays, such as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (39). The limitation of this test is similar to RT-PCR that only can test BRAF-V600E mutation. In addition, only a few cases of lung cancer have shown that VE1 clone has the potential to stain between 90% and 100% of p.V600E-mutant adenocarcinomas (40). It was previously reported that IHC using VE1 antibody is incapable of testing non-V600E mutation (41). However, another study has demonstrated that 599T insertion mutation in 1/21 cases stained with VE1 is positive for VE1 antibody. Hence, no standard recommendation or consensus was obtained for using BRAF p.V600E IHC (VE1) testing in NSCLC; extension validation must be deployed when IHC is used to test BRAF-V600E mutation.

Next-Generation Sequencing

As mentioned above, single-gene tests for BRAF mutation are unable to identify mutations occurring in exon 11; hence, a multiple-gene panel including BRAF mutations is more practical. In addition, with more novel rare driver genes discovered, there is an increased need for multigene testing compared to single-gene approaches. Current guidelines for gene testing in NSCLC should include BRAF, mesenchymal epithelial transition factor receptor (MET), rearranged during transfection (RET), Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2), neurotrophic tropomyosin receptor kinase (NTRK), and Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog (KRAS) for cases in which the common oncogenic drivers (EGFR, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), and ROS proto-oncogene 1 (ROS1) are negative and whenever an adequate technique is available (42). The advantages of NGS are as follows: 1) fewer tumor tissue; 2) facilitates testing of multiple biomarkers; 3) includes emerging biomarkers for clinical trial enrollment. Generally, it is more economical than sequential testing (43, 44). However, because of more data, interpreting the NGS reports becomes complex and its availability in the community or rural region is poor. Besides, the turnaround time of NGS is longer than those of RT-PCR and IHC assay. Hence, multiple-gene RT-PCR kit might be a more reasonable choice for gene tests.

Current Treatment Landscape

Chemotherapy

The activities of chemotherapy have been fully explored in patients with BRAF V600E mutation advanced NSCLC. Documented studies have revealed that advanced NSCLC patients harboring BRAF V600E mutations present poor prognosis when administered with chemotherapy; in addition, patients with BRAF V600E mutations appear to be insensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy (45–47). However, several reports showed that NSCLC patients harboring BRAF V600E mutations seemed to have extended survival compared with patients without oncogenic drivers (47, 48). Additionally, Claire Tissot et al. (49) have reported that patients’ survival is not connected with BRAF mutation status. Another French study also observed similar results that BRAF mutation was not prognostic of overall survival (50). In addition, a recent study suggested that class I BRAF V600E mutations have the potential to be less aggressive than class II and III non-V600E mutations, which present more possibilities to occur in brain metastases and RAS co-alterations; hence, this specific behavior made non-V600E patients have shorter progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) to chemotherapy, although the difference might be driven by fewer extrathoracic metastases and higher use of targeted therapies in class I patients (51). However, because of limited cases included in these studies, the results presented here should be interpreted with caution. Hence, future larger randomized trials are urgently warranted.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Monotherapy

Previous retrospective small-sample studies have found that BRAF-mutated NSCLC patients tend to display positive programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression (52–56); however, because of limited cases, no clear correlation between PD-L1 and BRAF mutations were found. Recently, a study including 29 NSCLC patients harboring BRAF mutations showed us that approximately 69% (20/29) of patients were PD-L1 positive; among them, over 40% (13/29) of patients presented higher PD-L1 expression (PD-L1 ≥50%). In addition, BRAF-mutated NSCLC patients were correlated with low/intermediate tumor mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite-stable status (57). In this study, researchers have reported that patients harboring BRAF mutations displayed limited response to ICIs. Additionally, several retrospective studies also observed a similar phenomenon. The objective response rate (ORR) to single anti–PD-(L)1 agent in BRAF-mutant patients is about 10%–30%, with a median PFS of 2–4 months, which is equal to that of a second-line ICI monotherapy in wild-type NSCLC (57–61) (Table 1). Combining these data, we can conclude that ORR and PFS of patients with BRAF non-V600E are higher than those in patients harboring BRAF V600E mutations, but OS results seem paradoxical, potential exploration might be that BRAF V600E mutations could benefit from targeted therapy. On the other hand, non-V600E mutations usually happen in smokers, and smoking status was found to be related to response to immunotherapy (62). In summary, these data indicated limited efficacy of ICIs in BRAF-mutant NSCLC. Recently, a case with BRAF V600E mutation presented durable response to ICI combined chemotherapy with PFS of 20 months (63). This is the first evidence of patients with BRAF V600E alteration treated with ICI combination regimens. This case provided evidence that the ICI combined regimens might be a promising choice for BRAF V600E-mutated NSCLC. Further prospective clinical trials are eagerly needed.

Table 1

| Trial | Mutation type | Numbers | objective response rate (ORR) | progression free survival (PFS) | overall survival (OS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunotarget | V600E | 17 | NA | 1.8 | 8.2 |

| Non-V600E | 18 | NA | 4.1 | 17.2 | |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer center (MSKCC) | V600E | 10 | 10 | 1.4 | 26 |

| Non-V600E | 36 | 22 | 3.2 | 24 | |

| Isarel lung cancer group (ICLG) | V600E | 12 | 25 | 3.7 | NA |

| Non-V600E | 10 | 33 | 4.1 | ||

| Expanded Access Program (EAP) Nivolumab | BRAF | 11 | 9 | NA | 10.3 |

| French Lung Cancer Group (GFPC) 01-2018 | V600E | 26 | 26 | 5.3 | 22.5 |

| Non-V600E | 18 | 35 | 4.9 | 12 |

ICI monotherapy for BRAF-mutated NSCLC.

Targeted Therapy

Sorafenib, an early-generation BRAF inhibitor, was developed as a targeted therapy against BRAF mutant kinase. Sorafenib is an oral multikinase inhibitor that displays activities to target B/C-RAF, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor (VEGFR2/3), platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR-β), and c-Kit (64, 65). Preclinical models suggested that sorafenib could suppress various cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth via inhibiting MEK and ERK phosphorylation (64). These studies provide a theoretical basis for sorafenib as a BRAF inhibitor. However, a previous study showed that the antitumor activities of sorafenib are correlated with EGFR mutation status but not K-ras mutation status (67). Carter et al. (68) have demonstrated that concurrent administration of sorafenib with chemotherapeutics could effectively delay tumor growth without increasing toxicity. These data promoted some researchers who have designed clinical trials to testify the value of sorafenib in NSCLC; however, these trials have not tested the patients’ BRAF mutation status (69, 70). Hence, whether sorafenib could serve as a BRAF inhibitor remains to be explored.

Dabrafenib and vemurafenib, novel-generation BRAF inhibitors, are ATP-competitive inhibitors of BRAF kinase. Both agents are specific in targeting BRAF V600E mutations. Vemurafenib was initially tested in a “basket” study including multiple non-melanoma cancers with BRAF V600 mutants. In the NSCLC cohort, 20 pretreated NSCLC patients were included and achieved a 42% ORR and 7.3 months of PFS (Table 2) (71). Gautschi et al. (72) also found that vemurafenib showed promising antitumor activities in BRAF V600-mutated NSCLC patients. Additionally, a recent research revealed that vemurafenib was specifically targeting BRAF-V600 mutants but was ineffective in patients with BRAF non-V600 mutants (73). Combining these data, current lung cancer guidelines recommended that vemurafenib could serve as an optional regimen in certain circumstances. A prospective trial showed that dabrafenib had clinical activity in BRAF V600-mutant NSCLC, and dabrafenib might act as a promising treatment choice for patients harboring BRAF V600E-mutant NSCLC, which lacks effective treatment options (74). In addition, a recent study has reported that BGB-283, a novel inhibitor of key RAF family kinases, showed promising antitumor activity with acceptable toxicity in patients with BRAF V600-mutated solid tumors including NSCLC (75). However, the activity of single BRAF inhibitors is limited; hence, researchers began to explore combination therapy. Several studies are ongoing to investigate the novel BRAF inhibitors in BRAF-mutated NSCLC patients.

Table 2

| Trial | Treatment lines | Agents | ORR | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01524978 | ≥2 | Vemurafenib | 42% | 7.3 | NA |

| EURAF Cohort | ≥2 | Vemurafenib, dabrafenib, or sorafenib | 53% | 5.0 | 10.8 |

| AcSé | ≥2 | Vemurafenib | 44.9% | 5.2 | 10 |

| NCT01336634 | ≥2 | Dabrafenib | 33% | 5.5 | NA |

| NCT02610361 | ≥2 | BGB-283 | 20% | NA | NA |

| NCT01336634 | ≥2 | Dabrafenib+Trametinib | 63% | 10.2 | 18.2 |

| NCT01336634 | 1 | Dabrafenib+Trametinib | 64% | 10.9 | 24.6 |

| NCT02974725 | ≥2 | LXH254+LTT462 | 66.7% | NA | NA |

Targeted therapy for BRAF-mutated NSCLC.

Dabrafenib plus trametinib, a type of MEK inhibitor, was the first explored combination regimen focusing on BRAF pathway inhibition. A previous phase 2, multicohort, multicenter, non-randomized, open-label study included 36 patients harboring BRAF V600E mutant who were treated with first-line dabrafenib plus trametinib. The ORR was 64% and PFS was 14.6 months, as assessed by an independent review committee; in addition, an OS of 24.6 months was achieved (76, 77). This study indicated that dual blockade of the BRAF pathway with BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors could produce a much stronger efficacy. Besides, dabrafenib plus trametinib combination as second-line or later setting was also evaluated (76, 77). Surprisingly, dual blockade of the BRAF pathway achieved similar results compared to that in first-line setting, with 63.2% ORR and almost 10 months of PFS. This study further confirmed the survival advantage of dabrafenib plus trametinib combination compared to single agents. Furthermore, LXH254, a novel BRAF/CRAF inhibitor, plus LTT462, an ERK1/2 inhibitor, was explored to evaluate its activity in patients with advanced/metastatic K-ras- or BRAF-mutant NSCLC in a phase Ib dose escalation study; preliminary analysis showed signs of efficacy in patients with BRAF-mutant NSCLC (78). Dose expansion is ongoing, and further efficacy analysis remains to be seen.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Combined Therapy

ICIs have transformed the treatment pattern of advanced NSCLC without oncogenic driver mutations. However, the activity of ICIs in NSCLC with oncogenic driver mutations remains limited. Recently, Lu et al. reported a case diagnosed with stage IV NSCLC with BRAF V600E mutation that achieved a longer response after being treated with atezolizumab plus chemotherapy (63). This study suggested that ICI combined therapy might be a promising regimen for NSCLC with BRAF V600E mutations. In addition, preclinical data revealed that selumetinib and trametinib could improve T-cell activation and increase CTLA-4 expression. Besides, anti-Cytotoxic T lymphocyte associate protein-4 (CTLA-4) antibody plus selumetinib and trametinib presented a survival benefit in mice bearing tumors with K-ras mutation (79, 80). Based on the preclinical data, Hellmann et al. (81) have designed a study to investigate the safety and clinical activity of combining a MEK inhibitor, cobimetinib, and a PD-L1 inhibitor, atezolizumab, in patients with solid tumors (n = 152). Among them, 28 NSCLC patients were recruited. For NSCLC patients, the median OS was 13.2 months, and the ORR was 18% (81). Additionally, another phase I/II trial was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of durvalumab plus tremelimumab with continuous or intermittent administration of selumetinib in advanced NSCLC patients (82) (Table 3). Up to now, clinical trials in melanoma have demonstrated the activities of ICI plus BRAF-targeted therapy; notably, the safety profile of this combination regimen warranted more attention. In addition, for NSCLC, data about ICI-combined BRAF-targeted therapies remained limited. The safety and clinical efficacy of this pattern warrant further investigation.

Table 3

| Trial | Phase | Treatment lines | Experimental arm | Enrolled population | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03600701 | II | ≥2 | Atezolizumab+combimetinib | Metastatic, Recurrent, or Refractory non-small cell lung cancer | Recruiting |

| NCT03299088 | Ib | ≥2 | Pembrolizumab+trametinib | Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer with K-ras gene mutations | Active |

| NCT03225664 | Ib/II | ≥2 | Pembrolizumab+trametinib | Recurrent non-small cell lung cancer | Active |

Several ongoing trials of ICIs combined with targeted therapy.

Mechanisms of Resistance to BRAF Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Exactly as other targeted therapies in NSCLC, resistance to BRAF pathway inhibitors would inevitably occur, leading to disease progression. However, information about resistance mechanisms of BRAF pathway inhibitors is poorly defined.

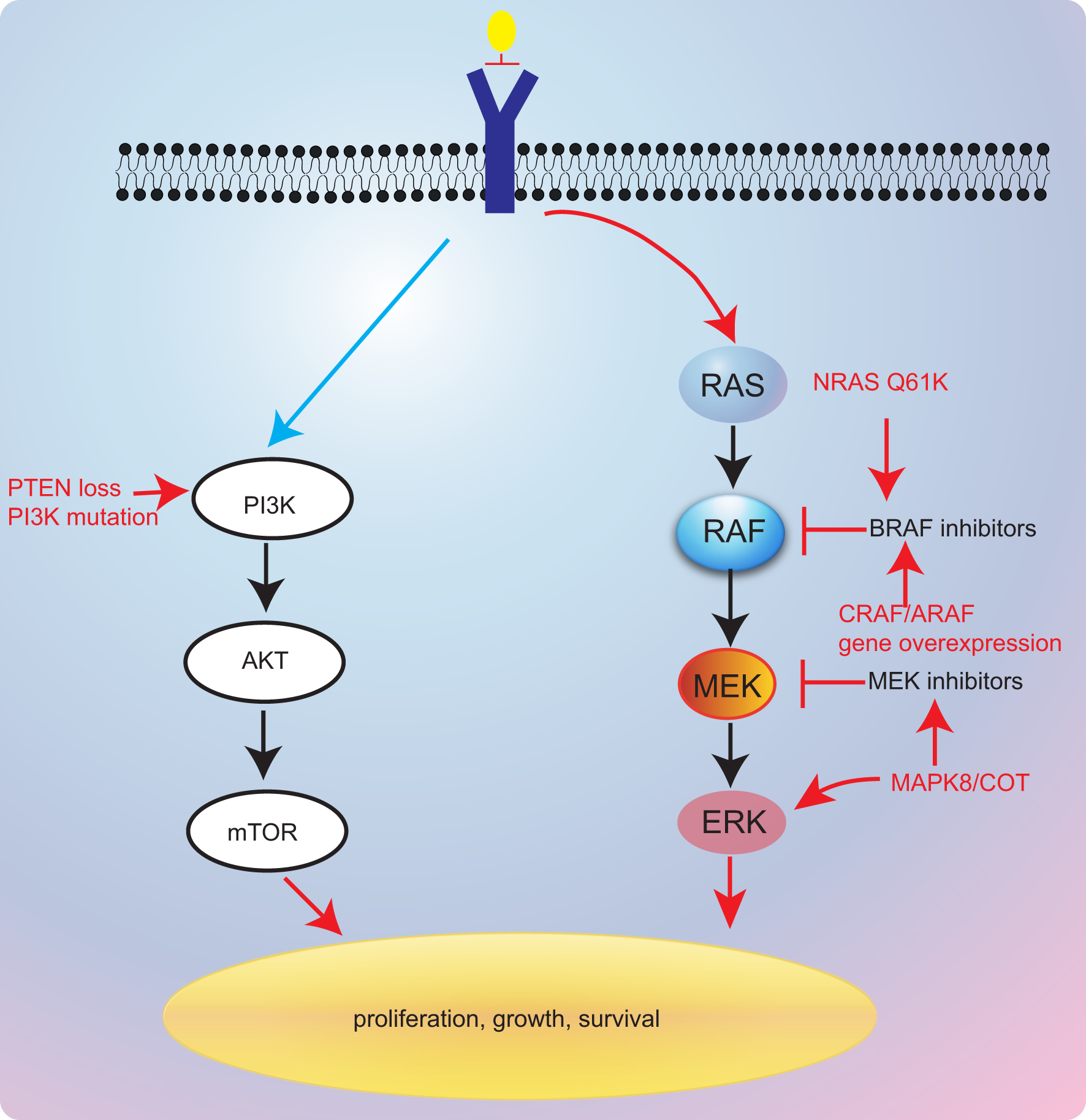

Currently, bypass activation is the main cause of secondary resistance of targeted therapy. However, there is limited report thus far that has revealed the resistance mechanisms of BRAF inhibitors in BRAF V600E NSCLC. In melanoma, other isoforms of RAF proteins (CRAF and A-Raf proto-oncogene (ARAF)) could also activate the MAPK pathway when BRAF was inhibited, which leads to resistance to BRAF pathway inhibitors (83). Several studies have also demonstrated that MAPK pathway stimulation by MAP3K8 or COT is associated with BRAF inhibitor resistance (83, 84) (Figure 3). However, the combination of BRAF inhibitors and MEK inhibitors could effectively reverse the resistance to monotherapy in BRAF-mutant NSCLC.

Figure 3

Resistance mechanisms of targeted therapies.

Additionally, Rudin et al. (85) have reported that acquired K-ras G12D mutation might be contributing to secondary resistance to dabrafenib. Coincidentally, K-ras G12V was also considered as mediating resistance to BRAF inhibitors (86). Besides, in a previous case report, researchers presented a case that was treated with dabrafenib and trametinib that developed N-ras Q61K mutation (87). These reports revealed that RAS gene might a critical gene modulator in resistance mechanisms to BRAF/MEK inhibitors. The last European Society For Medical Oncology (ESMO) congress reported a novel combination of LXH254 and LTT462 that might overcome RAS-related resistance to BRAF/MEK inhibitors (78). This regimen has shown antitumor activity in BRAF-mutant and K-ras-mutated patients. However, further investigation remains warranted.

Inactivation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a tumor suppressor, was also found to be involved in resistance to BRAF inhibitors in melanoma (88–90). A previous study has suggested that shorter PFS to anti-BRAF drugs was found in PTEN-deficient patients, further supporting the role of PTEN in resistance to BRAF inhibitors (91). Notably, PTEN lack-of-function alterations may be resistant to dabrafenib–trametinib combinations, the current standard of care, which lacks effective resolutions to this resistance.

Conclusions

Targeted therapy in driver gene-positive NSCLC has obtained significant progress and greatly revolutionized the landscape of NSCLC. However, the current treatment choice for BRAF-mutated NSCLC patients is not satisfactory because of lower incidence. Current guidelines recommend dabrafenib plus tremetinib as the only one standard targeted therapy option for BRAF-mutated NSCLC. However, the underlying resistance mechanisms of this combination regimen have not been clearly defined; in addition, current targeted therapy specifically targeted to BRAF V600E mutation exhibited poorer efficacy against non-V600E mutation.

Furthermore, clinical investigations will be also confronted with ongoing challenges. Firstly, randomized prospective phase III trials are difficult to conduct owing to the low incidence of BRAF mutant-positive NSCLC. Secondly, the utility and ethics of randomizing patients to a control arm with poorer efficacy and shorter survival durations are controversial. In addition, several studies have demonstrated that ICIs could show efficacy in this population; the problem that lies ahead is which regimen should be given first.

In the future, the activity of chemoimmunotherapy and combinations of TKIs with chemotherapy, anti VEGF/VEGFR agents, and/or immunotherapy in patients with BRAF-mutated cancers needs to be determined. In addition, the development of agents targeting non-V600E mutations should speed up.

Funding

This work was funded by the joint construction project of Henan Province and Ministry (No. LHGJ20190013).

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

(I) Conception and design: Ningning Yan, Shujing Shen, and Xingya Li. (II) Article writing: All authors. (III) Final approval of article: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

ChenWZhengRBaadePDZhangSZengHBrayFet al. Cancer Statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin (2016) 66:115–32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338

2

WangPZouJWuJZhangCMaCYuJet al. Clinical Profiles and Trend Analysis of Newly Diagnosed Lung Cancer in a Tertiary Care Hospital of East China During 2011-2015. J Thorac Dis (2017) 9:1973–9. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.102

3

ZhouFZhouC. Lung Cancer in Never Smokers-the East Asian Experience. Transl Lung Cancer Res (2018) 7:450–63. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.05.14

4

WellbrockCKarasaridesMMaraisR. The RAF Proteins Take Centre Stage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol (2004) 5:875–85. doi: 10.1038/nrm1498

5

BeeramMPatnaikARowinskyEK. Raf: A Strategic Target for Therapeutic Development Against Cancer. J Clin Oncol (2005) 23:6771–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.036

6

JonesonTBar-SagiD. Ras Effectors and Their Role in Mitogenesis and Oncogenesis. J Mol Med (Berl) (1997) 75:587–93. doi: 10.1007/s001090050143

7

Nguyen-NgocTBouchaabHAdjeiAAPetersS. BRAF Alterations as Therapeutic Targets in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol (2015) 10:1396–403. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000644

8

PlanchardDJohnsonBE. BRAF Adds an Additional Piece of the Puzzle to Precision Oncology-Based Treatment Strategies in Lung Cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med (2018) 142:796–7. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0088-ED

9

LiSLiLZhuYHuang CCQinYLiuHet al. Coexistence of EGFR With KRAS, or BRAF, or PIK3CA Somatic Mutations in Lung Cancer: A Comprehensive Mutation Profiling From 5125 Chinese Cohorts. Br J Cancer (2014) 110:2812–20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.210

10

BarlesiFMazieresJMerlioJPDebieuvreDMosserJLenaHet al. Routine Molecular Profiling of Patients With Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Results of a 1-Year Nationwide Programme of the French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup (IFCT). Lancet (2016) 387:1415–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00004-0

11

LeonettiAFacchinettiFRossiGMinariRContiAFribouletLet al. BRAF in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Pickaxing Another Brick in the Wall. Cancer Treat Rev (2018) 66:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.04.006

12

AmaralTSinnbergTMeierFKreplerCLevesqueMNiessnerHet al. The Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway in Melanoma Part I - Activation and Primary Resistance Mechanisms to BRAF Inhibition. Eur J Cancer (2017) 73:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.010

13

RossJSWangKChmieleckiJGayLJohnsonAChudnovskyJet al. The Distribution of BRAF Gene Fusions in Solid Tumors and Response to Targeted Therapy. Int J Cancer (2016) 138:881–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29825

14

MaitreECornetETroussardX. Hairy Cell Leukemia: 2020 Update on Diagnosis, Risk Stratification, and Treatment. Am J Hematol (2019) 94:1413–22. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25653

15

DaviesHBignellGRCoxCStephensPEdkinsSCleggSet al. Mutations of the BRAF Gene in Human Cancer. Nature (2002) 417:949–54. doi: 10.1038/nature00766

16

CurtinJAFridlyandJKageshitaTPatelHNBusamKJKutznerHet al. Distinct Sets of Genetic Alterations in Melanoma. N Engl J Med (2005) 353:2135–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092

17

JakobJABassettRLJrNgCSCurryJLJosephRWAlvaradoGCet al. NRAS Mutation Status Is an Independent Prognostic Factor in Metastatic Melanoma. Cancer (2012) 118:4014–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26724

18

YarchoanMLiVolsiVABroseMS. BRAF Mutation and Thyroid Cancer Recurrence. J Clin Oncol (2015) 33:7–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.3657

19

LassalleSHofmanVIlieMButoriCBozecASantiniJet al. Clinical Impact of the Detection of BRAF Mutations in Thyroid Pathology: Potential Usefulness as Diagnostic, Prognostic and Theragnostic Applications. Curr Med Chem (2010) 17:1839–50. doi: 10.2174/092986710791111189

20

FrenchAJSargentDJBurgartLJFosterNRKabatBFGoldbergRet al. Prognostic Significance of Defective Mismatch Repair and BRAF V600E in Patients With Colon Cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2008) 14:3408–15. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1489

21

LochheadPKuchibaAImamuraYLiaoXYYamauchiMNishiharaRet al. Microsatellite Instability and BRAF Mutation Testing in Colorectal Cancer Prognostication. J Natl Cancer Inst (2013) 105:1151–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt173

22

CaparicaRde CastroGJrGil-BazoICaglevicCCalogeroRGiallombardoMet al. BRAF Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Has Finally Janus Opened the Door? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol (2016) 101:32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.02.012

23

DanknerMRoseAANRajkumarSSiegelPMWatsonIR. Classifying BRAF Alterations in Cancer: New Rational Therapeutic Strategies for Actionable Mutations. Oncogene (2018) 37:3183–99. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0171-x

24

YaoZTorresNMTaoAGaoYJLuoLSLiŁQet al. BRAF Mutants Evade ERK-Dependent Feedback by Different Mechanisms That Determine Their Sensitivity to Pharmacologic Inhibition. Cancer Cell (2015) 28:370–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.08.001

25

YaoZYaegerRRodrik-OutmezguineVSTaoATorresNMChangMTet al. Tumours With Class 3 BRAF Mutants are Sensitive to the Inhibition of Activated RAS. Nature (2017) 548:234–8. doi: 10.1038/nature23291

26

PaikPKArcilaMEFaraMSimaCSMillerVAKrisMGet al. Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Lung Adenocarcinomas Harboring BRAF Mutations. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29:2046–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1280

27

LitvakAMPaikPKWooKMSimaCSHellmannMDArcilaMEet al. Clinical Characteristics and Course of 63 Patients With BRAF Mutant Lung Cancers. J Thorac Oncol (2014) 9:1669–74. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000344

28

Cancer Genome Atlas Research NetworkComprehensive Molecular Profiling of Lung Adenocarcinoma. Nature (2014) 511:543–50. doi: 10.1038/nature13385

29

FosterSAWhalenDMÖzenAWongchenkoMJYinJPYenIet al. Activation Mechanism of Oncogenic Deletion Mutations in BRAF, EGFR, and HER2. Cancer Cell (2016) 29:477–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.02.010

30

JohnsonDBChildressMAChalmersZRFramptonGMAliSMRubinsteinSMet al. BRAF Internal Deletions and Resistance to BRAF/MEK Inhibitor Therapy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res (2018) 31:432–6. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12674

31

ChenSHZhangYVan HornRDYinTGBuchananSYadavVet al. Oncogenic BRAF Deletions That Function as Homodimers and Are Sensitive to Inhibition by RAF Dimer Inhibitor Ly3009120. Cancer Discov (2016) 6:300–15. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0896

32

ZehirABenayedRShahRHSyedAMiddhaSKimHRet al. Mutational Landscape of Metastatic Cancer Revealed From Prospective Clinical Sequencing of 10,000 Patients. Nat Med (2017) 23:703–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.4333

33

JonesDTHutterBJägerNKorshunovAKoolMWarnatzHJet al. Recurrent Somatic Alterations of FGFR1 and NTRK2 in Pilocytic Astrocytoma. Nat Genet (2013) 45:927–32. doi: 10.1038/ng.2682

34

JonesDTKocialkowskiSLiuLPearsonDMBäcklundLMIchimuraKet al. Tandem Duplication Producing a Novel Oncogenic BRAF Fusion Gene Defines the Majority of Pilocytic Astrocytomas. Cancer Res (2008) 68:8673–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2097

35

SlominskiAWortsmanJNickoloffBMcClatcheyKMihmMCRossJS. Molecular Pathology of Malignant Melanoma. Am J Clin Pathol (1998) 110:788–94. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/110.6.788

36

BradishJRChengL. Molecular Pathology of Malignant Melanoma: Changing the Clinical Practice Paradigm Toward a Personalized Approach. Hum Pathol (2014) 45:1315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.04.001

37

ShollLMAndeaABridgeJAChengLDaviesMAEhteshamiMet al. Template for Reporting Results of Biomarker Testing of Specimens From Patients With Melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med (2016) 140:355–7. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0278-CP

38

LindemanNICaglePTAisnerDLArcilaMEBeasleyMBBernickerEHet al. Updated Molecular Testing Guideline for the Selection of Lung Cancer Patients for Treatment With Targeted Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med (2018) 142:321–46. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0388-CP

39

DunstanRWWhartonKAJrQuigleyCLoweA. The Use of Immunohistochemistry for Biomarker Assessment–Can it Compete With Other Technologies? Toxicol Pathol (2011) 39:988–1002. doi: 10.1177/0192623311419163

40

IlieMLongEHofmanVDadoneBMarquetteCHMourouxJet al. Diagnostic Value of Immunohistochemistry for the Detection of the BRAFV600E Mutation in Primary Lung Adenocarcinoma Caucasian Patients. Ann Oncol (2013) 24:742–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds534

41

SasakiHShimizuSTaniYShitaraMOkudaKHikosakaYet al. Usefulness of Immunohistochemistry for the Detection of the BRAF V600E Mutation in Japanese Lung Adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer (2013) 82:51–4. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.06.014

42

CallesARiessJWBrahmerJR. Checkpoint Blockade in Lung Cancer With Driver Mutation: Choose the Road Wisely. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book (2020) 40:372–84. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_280795

43

HirschFRKerrKMBunnPAJrKimESObasajuCPérolMet al. Molecular and Immune Biomarker Testing in Squamous-Cell Lung Cancer: Effect of Current and Future Therapies and Technologies. Clin Lung Cancer (2018) 19:331–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.03.014

44

YuTMMorrisonCGoldEJTradonskyALaytonAJ. Multiple Biomarker Testing Tissue Consumption and Completion Rates With Single-Gene Tests and Investigational Use of Oncomine Dx Target Test for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Single-Center Analysis. Clin Lung Cancer (2019) 20:20–29.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.08.010

45

CardarellaSOginoANishinoMButaneyMShenJLydonCet al. Clinical, Pathologic, and Biologic Features Associated With BRAF Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2013) 19:4532–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0657

46

MarchettiAFelicioniLMalatestaSSciarrottaMGGuettiLChellaAet al. Clinical Features and Outcome of Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring BRAF Mutations. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29:3574–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.9638

47

DingXZhangZJiangTLiXFZhaoCSuBet al. Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Outcomes of Chinese Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and BRAF Mutation. Cancer Med (2017) 6:555–62. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1014

48

KrisMGJohnsonBEBerryLDKwiatkowskiDJIafrateAJWistubaIIet al. Using Multiplexed Assays of Oncogenic Drivers in Lung Cancers to Select Targeted Drugs. Jama (2014) 311:1998–2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3741

49

TissotCCouraudSTanguyRBringuierPPGirardNSouquetPJ. Clinical Characteristics and Outcome of Patients With Lung Cancer Harboring BRAF Mutations. Lung Cancer (2016) 91:23–8.

50

CouraudSBarlesiFFontaine-DeraluelleCDebieuvreDMerlioJPMoreauLet al. Clinical Outcomes of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients With BRAF Mutations: Results From the French Cooperative Thoracic Intergroup Biomarkers France Study. Eur J Cancer (2019) 116:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.04.016

51

Dagogo-JackIMartinezPYeapBYAmbrogioCFerrisLALydonCet al. Impact of BRAF Mutation Class on Disease Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in BRAF-Mutant Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2019) 25:158–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2062

52

YangCYLinMWChangYLWuCTYangPC. Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1 Expression in Surgically Resected Stage I Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma and its Correlation With Driver Mutations and Clinical Outcomes. Eur J Cancer (2014) 50:1361–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.01.018

53

YangCYLinMWChangYLWuCTYangPC. Programmed Cell Death-Ligand 1 Expression Is Associated With a Favourable Immune Microenvironment and Better Overall Survival in Stage I Pulmonary Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Eur J Cancer (2016) 57:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.033

54

SongZYuXChengGZhangY. Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Expression Associated With Molecular Characteristics in Surgically Resected Lung Adenocarcinoma. J Transl Med (2016) 14:188. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0943-4

55

LanBMaCZhangCChaiSJWangPLDingLet al. Association Between PD-L1 Expression and Driver Gene Status in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Oncotarget (2018) 9:7684–99. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23969

56

TsengJSYangTYWuCYKuWHChenKCHsuKHet al. Characteristics and Predictive Value of PD-L1 Status in Real-World Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. J Immunother (2018) 41:292–9. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000226

57

DudnikEPeledNNechushtanHWollnerMOnnAAgbaryaAet al. BRAF Mutant Lung Cancer: Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression, Tumor Mutational Burden, Microsatellite Instability Status, and Response to Immune Check-Point Inhibitors. J Thorac Oncol (2018) 13:1128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.024

58

MazieresJDrilonALusqueAMhannaLCortotABMezquitaLet al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer and Oncogenic Driver Alterations: Results From the IMMUNOTARGET Registry. Ann Oncol (2019) 30:1321–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz167

59

GuisierFDubos-ArvisCViñasFDoubreHRicordelCRopertSet al. Efficacy and Safety of Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Patients With Advanced NSCLC With BRAF, HER2, or MET Mutations or RET Translocation: GFPC 01-2018. J Thorac Oncol (2020) 15:628–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.129

60

RihawiKGiannarelliDGalettaDDelmonteAGiavarraMTurciDet al. BRAF Mutant NSCLC and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Results From a Real-World Experience. J Thorac Oncol (2019) 14:e57–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.11.036

61

OffinMPakTMondacaSMontecalvoJRekhtmanNHalpennyDet al. P1.04-39 Molecular Characteristics, Immunophenotype, and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response in BRAF Non-V600 Mutant Lung Cancers. J Thorac Oncol (2019) 14:S455. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.08.942

62

GainorJFRizviHJimenez AguilarESkoulidisFYeapBYNaidooJet al. Clinical Activity of Programmed Cell Death 1 (PD-1) Blockade in Never, Light, and Heavy Smokers With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and PD-L1 Expression ≥50. Ann Oncol (2020) 31:404–11. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.11.015

63

NiuXSunYPlanchardDChiuLTBaiJAiXHet al. Durable Response to the Combination of Atezolizumab With Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in an Untreated Non-Smoking Lung Adenocarcinoma Patient With BRAF V600E Mutation: A Case Report. Front Oncol (2021) 11:634920. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.634920

64

WilhelmSMCarterCTangLWilkieDMcNabolaARongHet al. BAY 43-9006 Exhibits Broad Spectrum Oral Antitumor Activity and Targets the RAF/MEK/ERK Pathway and Receptor Tyrosine Kinases Involved in Tumor Progression and Angiogenesis. Cancer Res (2004) 64:7099–109. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1443

65

BlumenscheinGJr. Sorafenib in Lung Cancer: Clinical Developments and Future Directions. J Thorac Oncol (2008) 3:S124–127. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318174e085

66

GollobJAWilhelmSCarterCKelleySL. Role of Raf Kinase in Cancer: Therapeutic Potential of Targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK Signal Transduction Pathway. Semin Oncol (2006) 33:392–406. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.002

67

Paz-AresLHirshVZhangLMarinisFDYangJCHWakeleeHAet al. Monotherapy Administration of Sorafenib in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (MISSION) Trial: A Phase III, Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Sorafenib in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Predominantly Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer After 2 or 3 Previous Treatment Regimens. J Thorac Oncol (2015) 10:1745–53. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000693

68

CarterCAChenCBrinkCVincentPMaxuitenkoYYGilbertKSet al. Sorafenib Is Efficacious and Tolerated in Combination With Cytotoxic or Cytostatic Agents in Preclinical Models of Human Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (2007) 59:183–95. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0257-y

69

BlumenscheinGRJrGatzemeierUFossellaFStewartDJCupitLCihonFet al. Phase II, Multicenter, Uncontrolled Trial of Single-Agent Sorafenib in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory, Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27:4274–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.0541

70

WakeleeHALeeJWHannaNHTraynorAMCarboneDPSchillerJH. A Double-Blind Randomized Discontinuation Phase-II Study of Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006) in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E2501. J Thorac Oncol (2012) 7:1574–82. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31826149ba

71

HymanDMPuzanovISubbiahVFarisJEChauIBlayJYet al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers With BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med (2015) 373:726–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309

72

GautschiOMiliaJCabarrouBBluthgenMVBesseBSmitEFet al. Targeted Therapy for Patients With BRAF-Mutant Lung Cancer: Results From the European EURAF Cohort. J Thorac Oncol (2015) 10:1451–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000625

73

MazieresJCropetCMontanéLBarlesiFSouquetPJQuantinXet al. Vemurafenib in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients With BRAF(V600) and BRAF(nonV600) Mutations. Ann Oncol (2020) 31:289–94. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.022

74

PlanchardDKimTMMazieresJQuoixERielyGBarlesiFet al. Dabrafenib in Patients With BRAF(V600E)-Positive Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Single-Arm, Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol (2016) 17:642–50. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00077-2

75

DesaiJGanHBarrowCJamesonMAtkinsonVHaydonAet al. Phase I, Open-Label, Dose-Escalation/Dose-Expansion Study of Lifirafenib (BGB-283), an RAF Family Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients With Solid Tumors. J Clin Oncol (2020) 38:2140–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02654

76

PlanchardDBesseBGroenHJMHashemiSMSMazieresJKimTMet al. Phase 2 Study of Dabrafenib Plus Trametinib in Patients With BRAF V600E-Mutant Metastatic NSCLC: Updated 5-Year Survival Rates and Genomic Analysis. J Thorac Oncol (2021) 17(1):103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.08.011

77

PlanchardDSmitEFGroenHJMMazieresJBesseBHellandAet al. Dabrafenib Plus Trametinib in Patients With Previously Untreated BRAF(V600E)-Mutant Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: An Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol (2017) 18:1307–16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30679-4

78

WolfJPlanchardDHeistRSSolomonBSebastianMSantoroAet al. 1387p Phase Ib Study of LXH254 + LTT462 in Patients With KRAS- or BRAF-Mutant NSCLC. Ann Oncol (2020) 31:S881–2. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.1701

79

ChoiHDengJLiSSilkTDongLBreaEJet al. Pulsatile MEK Inhibition Improves Anti-Tumor Immunity and T Cell Function in Murine Kras Mutant Lung Cancer. Cell Rep (2019) 27:806–19.e805. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.066

80

PoonEMullinsSWatkinsAWilliamsGSKoopmannJOGenovaGDet al. The MEK Inhibitor Selumetinib Complements CTLA-4 Blockade by Reprogramming the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer (2017) 5:63. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0268-8

81

HellmannMDKimTWLeeCBGohBCMillerWHJrOhDYet al. Phase Ib Study of Atezolizumab Combined With Cobimetinib in Patients With Solid Tumors. Ann Oncol (2019) 30:1134–42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz113

82

GaudreauPOLeeJJHeymachJVGibbonsDL. Phase I/II Trial of Immunotherapy With Durvalumab and Tremelimumab With Continuous or Intermittent MEK Inhibitor Selumetinib in NSCLC: Early Trial Report. Clin Lung Cancer (2020) 21:384–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2020.02.019

83

VillanuevaJVulturAHerlynM. Resistance to BRAF Inhibitors: Unraveling Mechanisms and Future Treatment Options. Cancer Res (2011) 71:7137–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1243

84

JohannessenCMBoehmJSKimSYThomasSRWardwellLJohnsonLAet al. COT Drives Resistance to RAF Inhibition Through MAP Kinase Pathway Reactivation. Nature (2010) 468:968–72. doi: 10.1038/nature09627

85

RudinCMHongKStreitM. Molecular Characterization of Acquired Resistance to the BRAF Inhibitor Dabrafenib in a Patient With BRAF-Mutant Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol (2013) 8:e41–42. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828bb1b3

86

NiemantsverdrietMSchuuringEElstATWekkenAJKempenLCBergAVet al. KRAS Mutation as a Resistance Mechanism to BRAF/MEK Inhibition in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol (2018) 13:e249–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.07.103

87

AbravanelDLNishinoMShollLMAmbrogioCAwadMM. An Acquired NRAS Q61K Mutation in BRAF V600E-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma Resistant to Dabrafenib Plus Trametinib. J Thorac Oncol (2018) 13:e131–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.03.026

88

WeeSJaganiZXiangKXLooADorschMYaoYMet al. PI3K Pathway Activation Mediates Resistance to MEK Inhibitors in KRAS Mutant Cancers. Cancer Res (2009) 69:4286–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4765

89

ShiHHugoWKongXHongAKoyaRCMoriceauGet al. Acquired Resistance and Clonal Evolution in Melanoma During BRAF Inhibitor Therapy. Cancer Discovery (2014) 4:80–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0642

90

ObaidNMBedardKHuangWY. Strategies for Overcoming Resistance in Tumours Harboring BRAF Mutations. Int J Mol Sci (2017) 18(3):585. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030585

91

NathansonKLMartinAMWubbenhorstBGreshockJLetreroRD'AndreaKet al. Tumor Genetic Analyses of Patients With Metastatic Melanoma Treated With the BRAF Inhibitor Dabrafenib (GSK2118436). Clin Cancer Res (2013) 19:4868–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0827

Summary

Keywords

BRAF, NSCLC, targeted therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Citation

Yan N, Guo S, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Shen S and Li X (2022) BRAF-Mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Current Treatment Status and Future Perspective. Front. Oncol. 12:863043. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.863043

Received

26 January 2022

Accepted

22 February 2022

Published

31 March 2022

Volume

12 - 2022

Edited by

Chunxia Su, Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital, China

Reviewed by

Fan Yun, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, China; Qingzhu Jia, Army Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Yan, Guo, Zhang, Zhang, Shen and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ningning Yan, yanningrj@alumni.sjtu.edu.cn; yanningrj@163.com; Xingya Li, fcclixy1@zzu.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Thoracic Oncology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Oncology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.