- 1Institute of Marine Affairs, Chaguaramas, Trinidad and Tobago

- 2Nippon Foundation-University of Edinburgh Ocean Voices Programme, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Scientific, technical and traditional knowledge are critical for the implementation of the new agreement for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement). A Scientific and Technical Body (STB) is established by Article 49 of the BBNJ Agreement to provide scientific and technical advice to the Conference of the Parties (COP). Since the terms of reference and modalities for the operation of the STB shall be determined by the COP at its first meeting, it is necessary to start work now to identify the optimal set-up for the body. This paper seeks to contribute to the discussion on the possible procedural and operational modalities of the BBNJ Agreement's STB. It outlines the roles and functions assigned to the STB and identifies key advances beyond UNCLOS on equity issues such as gender, traditional knowledge, and geographic representation. Drawing on the lessons from the Legal and Technical Commission (LTC) of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the paper offers perspectives on the options for the composition of the STB. It covers issues such as the number of members and considerations around the need for multi-disciplinary expertise, gender balance, and equitable geographical representation; terms of office; access to, participation in, and transparency of meetings; and decision-making. These lessons learned from existing practice are an integral part of the knowledge-base required by States when making decisions regarding the design and operational modalities of the STB, and more broadly, offer important insights on fit-for-purpose and equitable scientific advisory bodies in environmental governance.

1 Introduction

A new agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS or the Convention) dealing with the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement) was adopted in July 2023 after many years of informal and formal negotiations (Long and Chaves, 2015; Tiller et al., 2019; Mendenhall et al., 2019; De Santo et al., 2020; Mendenhall et al., 2022; Tiller et al., 2023; Mendenhall et al., 2023; Tiller and Mendenhall, 2023). This significant achievement of the Agreement's adoption heralded a new era in the evolution of the BBNJ regime as States have now embarked on the processes of ratification and implementation (Gjerde et al., 2022).

In addition to a Preamble, the BBNJ Agreement contains twelve Parts and two Annexes.1 However, the negotiations, which took place between 2018 and 2023, were primarily structured around four substantive elements—Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs), including the fair and equitable sharing of benefits (Part II); Measures such as Area-Based Management Tools (ABMTs), including Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) (Part III); Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) (Part IV); and Capacity-Building and the Transfer of Marine Technology (CBTMT) (Part V), with a fifth catch-all category for cross-cutting issues. These cross-cutting issues facilitated discussion and negotiation around important considerations on institutional arrangements (Part VI), finance (Part VII), implementation and compliance (Part VIII) and dispute settlement (Part IX).

To facilitate implementation of the BBNJ Agreement and governance of the BBNJ regime, a number of integral institutional mechanisms have been established under the Agreement. These include an Access and Benefit-sharing Committee under Article 15, a Capacity-building and Transfer of Marine Technology Committee under Article 46, a Conference of Parties (COP) under Article 47, a Scientific and Technical Body (STB) under Article 49, a Secretariat under Article 50, a Clearing-House Mechanism under Article 51 and an Implementation and Compliance Committee under Article 55. Notably, a high-level overview of the general functions of these institutional arrangements is provided in the text of the BBNJ Agreement, but detailed terms of reference, modalities for the operation and/or rules of procedure for them still need to be decided upon.2 Of the five bodies established by the Agreement, there is a time bound obligation on the COP to decide the terms of reference and modalities for the STB [Article 49(2)] and the Capacity-building and Transfer of Marine Technology Committee [Article 46(2)] at its first meeting.

The STB is the central means to institutionalize access to science and knowledge under the BBNJ Agreement including by providing scientific and technical advice to the COP (Gaebel et al., 2024). As an essential Body to be operationalized, its terms of reference, modalities for operation, and rules of procedure are among priority areas to be addressed by the COP at its first meeting.3 In this regard, these topics will be deliberated by a Preparatory Commission (Prep Comm) established by the UN General Assembly to prepare for the entry into force and effective implementation of the BBNJ Agreement.4 As such, it is a critical time to explore what an effective STB would entail and require, which can, in part, be informed by current practice. Whilst recognizing that the STB operates within a unique context and will therefore have some BBNJ-specific requirements, it is instructive to consider lessons from existing scientific and technical advisory bodies (Andresen et al., 2018). For example, looking to current practice can illustrate the different design options available to decision-makers, but also help identify where the BBNJ Agreement differs from other instruments and where innovation may be required.

This paper seeks to contribute to the discussion on the procedural and operational modalities of the BBNJ Agreement's STB which will take place in the Prep Comm, the COP, and beyond. In doing so it will draw on the experiences from another technical body established under the ambit of UNCLOS, the Legal and Technical Commission (LTC or the Commission) of the International Seabed Authority (ISA).5 The LTC is an organ of the Council of the ISA and, similar to the STB, it is tasked with providing legal and scientific advice to prepare and support decision-making. Also similar to the STB, the LTC's competence lies in marine areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), albeit specifically the international seabed and the resources found there. By exploring how the LTC operates and functions, including through examination of official documents of the ISA, experiential knowledge from the lead author's involvement as an LTC member, elicited experiences of other persons who have served on the LTC,6 and commentary and research findings from the scholarly literature, lessons have been learned which are applicable in operationalizing the STB. This paper will therefore proceed to contextualize these lessons in order to present useful suggestions going forward on STB set-up and working practices. It will first present an overview of the STB and elucidate its key mandatory and discretionary functions as mandated under the BBNJ Agreement. It will then identify lessons learned from the LTC and, based on this, discuss opportunities when designing and operationalizing the STB.

2 Background

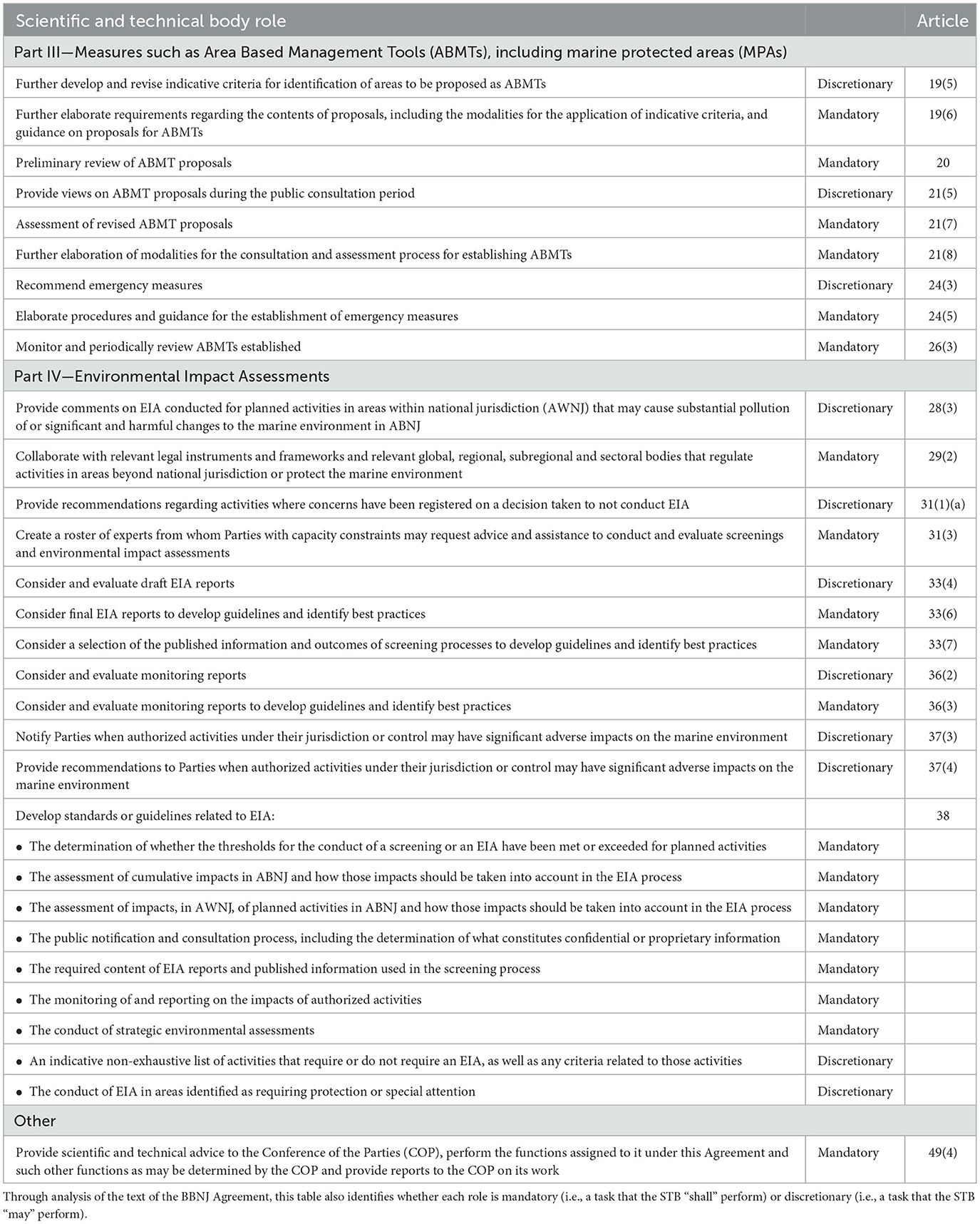

The STB is established in Part VI of the BBNJ Agreement under Article 49. It is here that its mandate is outlined. Acting under the authority and guidance of the COP, the STB is tasked with providing scientific and technical advice to the COP and providing reports to the COP on its work, as well as performing the functions assigned to it under the BBNJ Agreement. These defined functions are numerous but are mainly concentrated in Part III (ABMTs) and Part IV (EIAs) of the Agreement (Table 1). As summarized in Table 1, some of these functions are mandatory and are explicitly mandated as tasks that the STB “shall” (i.e., must) perform, while others are discretionary functions that the Agreement states that the STB may or could perform. In addition, with a view to future proofing the Agreement and allowing scope for the regime to be as adaptable and responsive to changing or unforeseen circumstances as possible, the BBNJ Agreement includes text stating that the STB must also perform any other functions as may be determined by the COP.

The roles and functions of the STB are very similar to those of the LTC. Established under Article 163 of UNCLOS as an organ of the Council of the ISA, the LTC's functions are further elaborated under Article 165 of the Convention. Its roles in relation to activities in the Area7 include, inter alia, formulating and keeping under review the rules, regulations and procedures in relation to activities in the Area; reviewing applications for plans of work; supervising exploration or mining activities (including review of annual reports submitted by contractors); assessing the environmental implications of activities in the Area; developing environmental management plans; and making recommendations to the Council on all matters relating to exploration and exploitation of non-living marine resources.

By virtue of the similarities in role and function, as well as geographical scope (marine areas in ABNJ), the experience of the LTC, which has been in existence since 1997, can provide invaluable lessons learned to help determine some of the critical characteristics of the BBNJ STB. With this in mind, the paper will next go on to offer perspectives on the optimal composition of the STB, including number of members and considerations around the need for multi-disciplinary expertise, gender balance, and equitable geographical representation; terms of office including their length; considerations for facilitating adequate access to, participation in, and transparency of meetings; and the decision-making process of the Body.

3 Operationalizing the STB with lessons from the LTC

3.1 Number of members

The number of members that comprise a scientific advisory body is an important design consideration (Behdinan et al., 2018) and necessitates balancing the need for the body to be large enough to foster participation but not so large that it becomes unwieldy or unable to facilitate high-quality deliberations (van den Hove and Sharman, 2017). In this regard, the BBNJ Agreement is silent on the number of members that should make up the STB.8 The optimal size of the body is therefore a fundamental issue to be resolved and one where the experience of the LTC can be instructive. Since the first election of members of the Commission was held in August 1996, the LTC has had an ever-expanding membership up to present, but this has been for both political and practical reasons, more so the former.

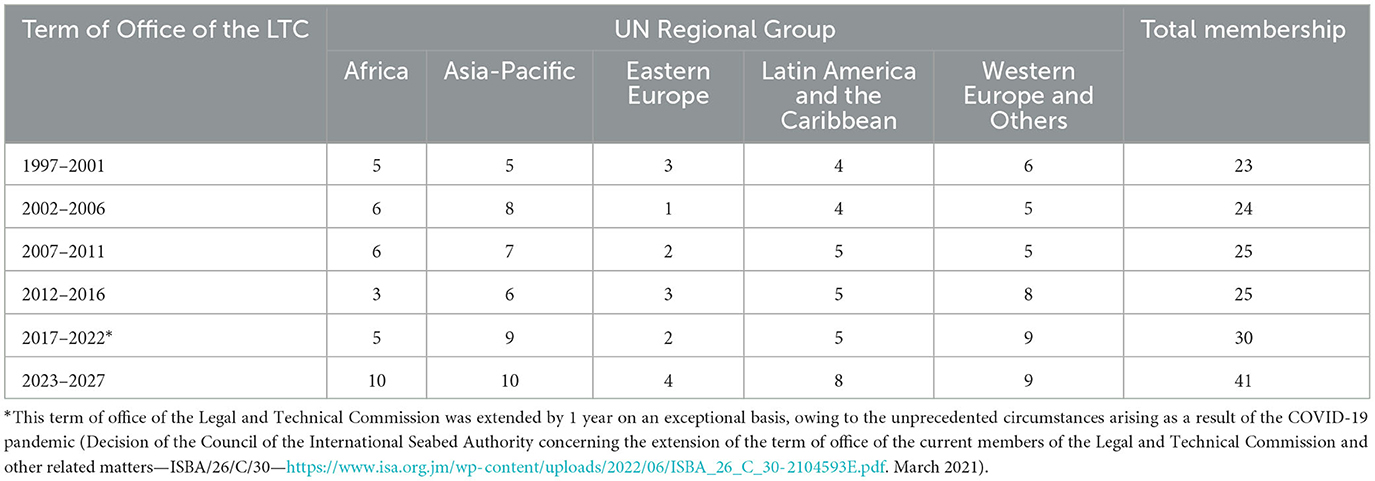

Unlike the BBNJ Agreement, Article 163(2) of UNCLOS specifies that the LTC shall be composed of 15 members. That being said, the Article also gives latitude to the Council of the ISA to increase the size of the Commission with due regard for economy and efficiency. From the LTC's inception the flexibility inherent in Article 163(2) has been leveraged because the Commission has never been composed of 15 members. Instead, the LTC has comprised of 23-41 members in practice, with the number of total members increasing over time (Table 2).

Table 2. Overview of the composition of the Legal and Technical Commission across the respective office terms and regional groups (LTC composition data is made openly available by the ISA, including here: https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/LTC_Membership_1997-2027_Rev_January_2024.xlsx, Accessed March 2025).

Indeed, the experience in the ISA has been that nominations submitted of potential LTC members have always exceeded the number of seats assigned [fifteen as per Article 163(2) of UNCLOS]. However, historically there has been a desire to avoid a vote in electing members of the Commission and as a result, the practice has been to elect by acclamation all of the candidacies submitted. Over the years, and certainly in the most recent elections,9 the inability of the Council to settle on an appropriate balance of regional representation within the body, despite repeated attempts being made,10 has precipitated the ballooning in membership of the LTC.

The first ISA exploration contract was signed in 2001. Since then, exploration activities have steadily increased such that, up to the present day, there have been 31 contracts entered into, split among 22 contractors. In the burgeoning regime, with its attendant heightened interest and prevailing substantive undertakings, an increased workload has inevitably accompanied the aforementioned expansion of the LTC. Indeed, the current Commission, with its 41 members, does have a substantial amount of work to address.11 It is observed that the LTC is kept busy throughout, both in session, during their in-person meetings, and intersessionally. Therefore, although the Commission has had an expansion resulting primarily from political machinations, an expansion based on workload has not been unjustifiable.

That being said, the Commission, through reports issued, have suggested that the LTC has functioned effectively with a membership of 24.12 In thinking about the STB under the BBNJ Agreement and its projected workload, this may be an appropriate base number of members to consider. Of course, scope should be left for adjusting membership numbers, as necessary, through decisions of the COP. As evidenced by the occurrences in ISA, keeping membership of the STB limited and manageable will be important from a cost perspective.13 In addition to this, there should be a desire to avoid too large a Body to maintain efficiency and effective coordination, cultivate collegiality, perpetuate prestige being associated with serving as an elected member of the STB and better encourage accountability, including through social and peer pressure mechanisms.

3.2 Membership composition and expertise

It is acknowledged that the STB will have a mandate that extends across all ABNJ globally, and, given the current and forecasted trajectory of anthropogenic expansion into the ocean (Jouffray et al., 2020), responsibility to provide, as far as practicable, scientific and technical advice pertaining to wide-ranging subject matter. Recognizing this, the BBNJ Agreement, in establishing the STB, has highlighted the need for multidisciplinary expertise, gender balance, and equitable geographical representation in composing the Body. However, finding a balance across expertise, gender, and geographical locations may present challenges in practice (Gaebel et al., 2024; Gopinathan et al., 2018).

(i) Equitable geographic representation

With regard to equitable geographical representation on the LTC, Article 163(4) of UNCLOS uses almost identical language to the BBNJ Agreement in stating that “…due account shall be taken of the need for equitable geographical representation…”. However, as discussed earlier, the lack of specifics on how this particular characteristic of the Commission is to be given effect has contributed to an expanding membership which, some have argued, may not have been necessary from the strict standpoint of being able to fulfill the organ's operational mandate (Willaert, 2020).

The BBNJ COP should be mindful of this and seek to outline, from upfront, clear guidelines endeavoring to achieve equitable geographical representation on the STB. For example, if the STB is to have 25 members, the election guidelines could specify that every regional group of the UN propose five candidates each of whom, once they meet qualification requirements, can appropriately be elected through acclamation by the COP. The regional groups will have the responsibility to internally decide on and nominate their desired candidates. If the regional group cannot settle on their allocated five internally and there are more than this requisite number nominated, those candidates would be subject to election through ballot by all the Parties to the Agreement. Of course, this approach may mean that any increases to the membership of the STB may have to take place in multiples of five unless the COP can decide otherwise. Also, there may still be imbalances in geographical representation if any particular regional group cannot produce five candidates and therefore their allocations must be passed to the other regional groups. However, it is important to note that this proposed approach is a departure point in striving for equitable geographical representation.

(ii) Gender balance

Formalizing a process to achieve gender balance, whilst potentially more challenging, is also of paramount importance. In this regard, the LTC has traditionally been a male dominated sphere.14 For example, for the 2023–2027 term only ten of the forty-one elected members are women. UNCLOS does not speak on gender requirements in its text, including with respect to the ISA, and has no prescriptions pertaining to gender balance in the LTC (Goettsche-Wanli, 2019). As such, the BBNJ Agreement exhibits marked progress under the law of the sea regime as it relates to pronouncing on gender equality (Long, 2021; Kitada and Rodríguez-Chaves, 2024). For example, the Agreement refers to the common interests of humankind (not mankind) in the Preamble, and common heritage of humankind in Article 7(b).15

That being said, achieving gender balance may not be straightforward. Individual State Parties to the Agreement will be responsible for nominating candidates to the STB in what should be independent, sovereign decisions. It may be considered an overreach for the COP to be prescriptive regarding the gender of a State's nominated candidate. However, the language adopted in the BBNJ Agreement can be used to urge Parties to nominate candidates that will progress the goal of achieving gender balance on the STB and also be used by Parties to strengthen the case and justify the selection and/or election of one candidate over another. Additionally, leveraging review mechanisms that are included under the BBNJ Agreement,16 could help foster a reflexive approach, through which progress against gender equity and other considerations for the STB's composition are periodically reviewed.

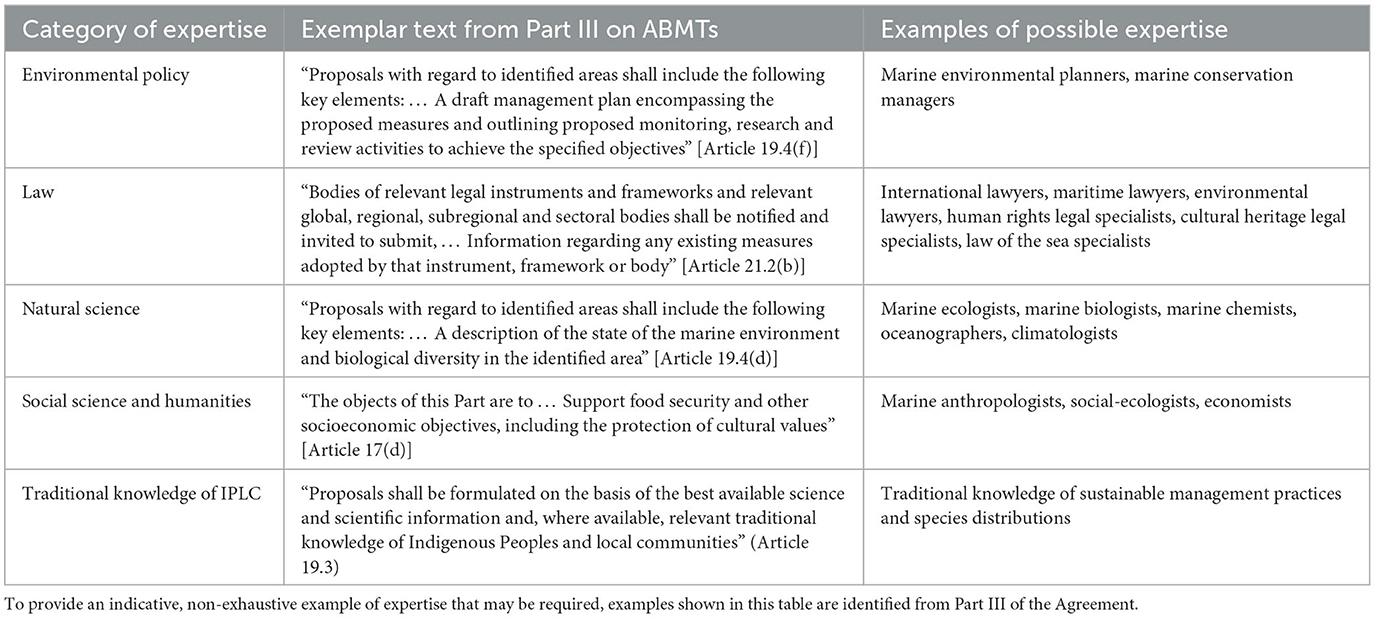

(iii) Multidisciplinary expertise

It is also intended for the BBNJ STB to be multidisciplinary but, again, it may exceed the COP's powers to prescribe to nominating States the field of expertise of their particular candidate. However, lessons can be learned from the LTC which can help further the ambition of achieving a multidisciplinary STB for BBNJ. For example, prior to each nomination and election cycle, the COP could indicate, based on an anticipated program of work, a range of areas of expertise, inclusive of relevant specialties, from which potential STB members can be drawn. Nominations could then fit into these indicated expertise brackets, with attempts to strike a multidisciplinary balance when members are elected. This was the new procedure undertaken for the LTC nominations and elections in the 2023–2027 term where suggested expertise and specialties were identified and, importantly, particular underrepresented fields highlighted.17 The past LTC iterations had a dearth of environmental science practitioners, but through this process, the number of elected members within that area increased for the term, leading to a better, more balanced representation of required competencies.

Based on the roles and functions of the STB as outlined in the BBNJ Agreement, it is possible to identify the expertise that may be required to fulfill these roles. As an example of what this could look like in practice, Table 3 shows results from an initial and preliminary analysis of the text of the BBNJ Agreement, to determine what competences would be required to fulfill more specific duties regarding ABMT proposals [Article 21(7)]. From exercises such as this, it is possible to propose a preliminary, indicative list of suggested expertise and specialties of STB members. This list is definitely non-exhaustive and bears in mind that the BBNJ Agreement, through Article 49(3), leaves scope for the STB to draw on appropriate advice emanating from external actors and individuals as needed. The expertise needed may also evolve over time should COP decisions be adopted in the future which change the roles and functions of the STB and/or as new and different activities emerge and become more prevalent in ABNJ.

In addition to relevant scientific and technical expertise, the BBNJ Agreement specifically highlights that expertise in relevant traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLCs) be included among the disciplines found on the STB. The inclusion of references to traditional knowledge of IPLCs across the BBNJ text was championed chiefly by the Pacific Small Island Developing States (PSIDS) during the negotiations, and reflection of this language in the treaty is another progressive aspect of the Agreement (Mulalap et al., 2020; Smith and Huffer, 2023; Vierros et al., 2020). Similar references have only recently begun to permeate discussions within the ISA, including in the negotiation of the Mining Code's exploitation regulations and in the advancement of the standardized approach for the development, approval and review for regional environmental management plans (REMPs) (Lixinski, 2024).

Holders of traditional knowledge have not been represented on the LTC as of yet, nor have there been members with expertise in traditional knowledge of IPLCs as this was never highlighted in the Convention as necessary for the Commission. However, given observed developments, circumstances may change in the future (Caldeira et al., 2025). For the BBNJ STB though, inclusion of expertise in traditional knowledge of IPLCs is called for, including specific reference in relation to the composition of the STB in Article 49(2). Given the singling out of these forms of knowledge as they relate to the STB, rather than leave it up to chance that any given State nominates a candidate with this specialty for election, it may be necessary to reserve space in the membership of the STB to ensure that representation of traditional knowledge of IPLCs would be separate and apart from that allocated to the regional groups.

3.3 Terms of office

Term length and limits of membership are important considerations in the establishment of any given Body and require finding a balance between the benefits derived from fostering institutional memory, and the benefits of bringing in new members. In the case of the STB, terms should allow enough time for members to become familiar with the work of the Body, its processes, and its practices, in order to afford sufficient opportunity to make positive and worthwhile contributions. At the same time however, this must be balanced with the need to periodically inject new personalities, novel ideas, and fresh perspectives to avoid stagnation of both the members and the Body as a whole, as well as foster principles of inclusivity and participation.

The BBNJ Agreement leaves details on the terms of STB members to be decided in the first COP. It lies in contrast to the LTC where the terms of appointment were outlined in the Convention itself. Article 163(6) of UNCLOS specifies that members of the LTC shall be appointed for 5 years but they are eligible for re-election for a further term. Therefore, many LTC members in the past have served 10 consecutive years. Several long-standing LTC members have intimated that it took them a few years to get comfortable in their roles on the Commission and fully proficient in carrying out their duties. For the STB, a 4- or 5-year term does seem like an appropriate length, with the opportunity to serve an additional term being available to those members who wish to be re-elected.

For continuity purposes, and the ability to provide mentorship when needed, after the conclusion of the first term of the STB, it would be prudent in subsequent terms for the Body to have a mix of new members alongside members who have served before. Therefore, to achieve this, the first term membership of the STB would have to be unique, where half of the members would only serve one term. This would allow for half of the incoming members on the second term to be new and provide the basis for a mix of old and new members on the STB going forward. Considerations for how this would be operationalized in practice are important. For first term members there may always be some who are desirous of serving only one term, then the remainder who mandatorily must only serve one term may be randomly chosen. After the first term of the STB, for each subsequent term, the profiles of members who are being re-elected would also inform the expertise and gender ideally required from new members and where they would originate from geographically.

3.4 Participation in meetings

A commonly cited criticism of the LTC is its perceived secretive nature which stems from, among other things, meetings of the Commission being closed and consequently, important technical and substantive discussions being held in private (Ardron et al., 2023; Morgera and Lily, 2022; Willaert, 2020). Indeed, the Rules of Procedure of the LTC specify that “meetings of the Commission shall be held in private unless the Commission decides otherwise”.18 It goes on to state that “(t)he Commission shall take into account the desirability of holding open meetings when issues of general interest to members of the Authority, which do not involve the discussion of confidential information, are being discussed”. The general practice in the Commission's operations however has been to hold closed meetings with the leeway to hold open meetings very rarely exercised.19 The lack of transparency in the decision-making processes of the LTC are among factors that have led some commentators to question the social legitimacy of the deep seabed mining regime (Jaeckel et al., 2023).

Transparency was an important element of the negotiating process of the BBNJ Agreement, especially post-COVID-19 pandemic (Mendenhall et al., 2022; Tiller et al., 2023). It included encouraging a high level of international organization and civil society access, by allowing their presence in most negotiating rooms and using UN web platforms to broadcast many of the sessions. The adopted Agreement also includes Article 48 on Transparency in which paragraph 1 obligates the COP to promote transparency in decision-making processes while paragraph 2 mandates all meetings of subsidiary bodies be open to observers participating in accordance with the rules of procedure unless otherwise decided by the COP.

In implementation, it is important for the BBNJ process to maintain, and improve upon, its inclusivity and participatory nature including within the bodies established under the Agreement. Therefore, in formulating the rules of procedure for the STB, unlike with the case of the LTC, closed meetings should be the exception, if it all, rather than the norm. The rules of procedure should encourage observer participation including by allowing access to accredited international and civil society organizations. Article 38(1)(d) of the BBNJ Agreement mandates the STB to develop standards or guidelines for consideration and adoption by the COP on what constitutes confidential or proprietary information within the context of EIA public notification and consultation processes. This guidance may prove useful in determining the parameters for if and when STB meetings should be closed to observers.

With a view to better encouraging participation by STB members themselves in the meetings of the Body, two practices of the LTC provide valuable lessons learned. The first is that funding, when available, be provided for STB members from developing countries to cover costs associated with attending the meetings. In the LTC, members from developing countries, through a formal request from their government, can request support from the ISA's Voluntary Trust Fund to defray the costs of participation in meetings. Depending on how much money is in the Voluntary Trust Fund, these requests provide for airfare as well a per diem which covers expenses such as meals and accommodation. The BBNJ Agreement has established a similar voluntary trust fund under Article 52(4) which is meant to facilitate the participation of developing States Parties in meetings of the bodies under the Agreement, of which the STB is one. Evidently, it will be important to keep this voluntary trust fund well resourced. The voluntary trust fund established during the negotiation of the BBNJ Agreement for a similar purpose faced challenges at various points in funding delegates who applied (Hassanali, 2022). This is not a BBNJ-specific problem, noting that the Voluntary Trust Fund of the ISA has also, on occasion, faced constraints in its ability to fund LTC members to attend meetings.

The second practice of the LTC that would be useful to embrace in the BBNJ's STB would be having full translation services for meetings, in the six official UN languages (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish). Rules 24-27 of the rules of procedure of the LTC provide for full interpretation of speeches and interventions at LTC meetings as well as translation of all recommendations and reports published by the Commission. The STB needs to follow suit, especially given its requirement for equitable geographical representation on the Body.

As a final point on participation and specifically within the context of consultation, apart from the Secretariat who will service the meetings of and provide administrative support to the STB, and the Clearing-House Mechanism which will indeed be an integral part of the STB's operations (Gaebel et al., under review)20, other specialist subsidiary bodies under the BBNJ Agreement, such as the Access and Benefit-sharing Committee, the Implementation and Compliance Committee and the Capacity-building and Transfer of Marine Technology Committee, will likely have the need to interface and interact with the STB, and vice versa, on substantive matters. The modalities for operation and rules of procedure of the STB, and all subsidiary bodies under the Agreement, should be such that this can be seamlessly done, as required. If there were, for example, a need to channel communication through the COP, this in itself may cause undue delay. Having a Rule in the STB's rules of procedure similar to Rule 15 of the LTC's rules of procedure21 may suffice in facilitating the desired type of interaction. Since the terms of reference and modalities for the operation of the CBTMT Committee also are to be decided by the COP at its first meeting, there is an opportunity to consider interaction between this Committee and the STB to ensure harmony between these two bodies and set the scene for interaction between all bodies under the Agreement.

3.5 Decision-making

As a pluralistic, multidisciplinary body with an influential role under the BBNJ Agreement, including through the recommendations it makes to the COP, the STB's rules on decision-making are also therefore important. Article 47(5) of the BBNJ Agreement sets out the decision-making process of the COP whereby every effort to adopt decisions and recommendations by consensus shall be made. It goes on to say that if all efforts to reach consensus have been exhausted, decisions and recommendations of the COP on questions of substance shall be adopted by a two-thirds majority of the Parties present and voting, and decisions on questions of procedure shall be adopted by a majority of the Parties present and voting. It is prudent that if the COP already allows decisions and recommendations to be adopted by qualified majority voting after the exhaustion of attempts to reach consensus, this could also be the practice endorsed for the STB.

In this regard, the LTC practices decision-making by consensus and voting. Generally, decision-making is done by consensus and if all attempts to reach decisions by consensus have been exhausted then decisions are taken by a majority of the members present and voting. Members of the Commission have agreed that this process has worked well within the LTC's context. In outlining the rules of procedure for the STB, the BBNJ COP may therefore consider adopting, mutatis mutandis, the language used in Section VIII (Rules 43-52) of the LTC's rules of procedure.22

3.6 Serving in expert capacity

A final point that is related to decision-making by STB members is that, although they will be nominated by individual States Parties to the Agreement, they are intended to serve on the STB in their “expert capacity and in the best interests of the Agreement” [Article 49(2)], i.e., personal capacity as opposed to being an agent of the State who nominated them. Recognition and acknowledgment of this fact is a first, albeit admittedly imperfect step to contribute to minimizing political influence on the STB and its members. In the case of the LTC, it is understood that members serve in their personal capacity. However, this is not officially stated in the Convention nor in the rules of procedure of the Commission.23 In drafting the rules of procedure for the STB, for the erasure of all doubt, it may be useful to explicitly state that members of the STB will serve in their personal capacity.

4 Discussion and conclusions

Provision of scientific advice and the embracing of diverse and varying knowledge systems was crucial in the negotiation of a fit for purpose BBNJ Agreement through, among other things, helping delegates to better understand the marine ecosystem of ABNJ and its roles and functions, elucidating the problems at hand and potential solutions, and in highlighting the numerous gaps in knowledge that exist (Morgera, 2021; Mulalap et al., 2020; Orangias, 2022; Popova et al., 2019; Tessnow-von Wysocki and Vadrot, 2020, 2024; Vierros et al., 2020). As a reflection of this, the establishment of a mechanism to provide scientific advice under the Agreement was relatively uncontroversial with early convergence on the need for such an institutional arrangement.24 This was eventually concretized in the form of the STB established under Article 49.

With the BBNJ Agreement now adopted and entry into force on the horizon, immediate attention must be directed into finalizing finer details concerning the STB. Getting these details right is key to the Body's efficient and effective operationalization. Their significance is even more pronounced given the importance of the STB to adequate and competent implementation of the BBNJ regime (e.g., Morgera et al., 2023). Gaebel et al. (2024), through interviews with BBNJ stakeholders, identified several key characteristics of an appropriately designed and implemented STB. These included it being:

• Multidisciplinary and incorporative of diverse knowledge systems.

• Inclusive, equitable and participatory.

• Proficient and pertinent.

• Influential within the decision-making process.

• De-politicized and separate from political influences.

• Transparent and accountable.

• Synergistic with the existing governance framework.

• Dynamic and adaptable to changing conditions and needs.

With these in mind, and in light of the need to develop the terms of reference, modalities for operation and rules of procedure for the STB beyond characteristics already outlined in the BBNJ Agreement, the following key recommendations are proposed based on the lessons from the LTC identified in this paper:

1. Size: When States design the STB, the balance should be struck between wide participation and representation and effectiveness. One option would be for the STB to initially comprise of 26 members, serving in their personal capacity, with five seats allocated to each UN Regional Group and one additional seat for a member with expertise in relevant traditional knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

2. Term: Considering the need to enhance institutional memory and continuity, whilst allowing for new perspectives, the Body should have five-year terms of office with the opportunity for members to serve one additional term. There should be a mix of old members and new members in each STB term. An anticipated program of work for the forthcoming term and the profiles of the members to be re-elected can provide the basis for determining the recommended characteristics of new membership nominees e.g., areas of expertise and gender.

3. Expertise: Expertise of the initial STB membership should include persons appropriately qualified in relevant fields such as Environmental Policy (e.g., marine environmental planning, marine conservation management); Law (e.g., international law, maritime law; environmental law, law of the sea specialists); Natural Science (e.g., marine ecology, marine biology, marine chemistry, oceanography, climatology); and Social Science (e.g., marine anthropology, social-ecology, economics). Relevant traditional knowledge holders and/or experts must also have representation. The composition of the STB and its representativeness across required disciplines and knowledge systems should be periodically reviewed and assessed.

4. Transparency: Noting the emphasis on transparency and accountability across the BBNJ Agreement, meetings of the STB should be open to accredited observers except when confidential information is being discussed.

5. Inclusivity: To further enhance participation and inclusivity, the STB needs to be afforded full translation services during its meetings and in respect to any of its decisions, recommendations and other outcome documents. Also, members of the STB from developing countries should be funded to attend meetings, including through use of the voluntary trust fund established under the Agreement. In this regard, it is of utmost importance to keep this fund well-resourced.

6. Decision-making: In line with other decision-making arrangements in the BBNJ Agreement, decision-making under the STB should be primarily by consensus but there must also be the ability to vote if needed.

With regard to some of these recommendations and certainly on additional issues such as confidentiality and frequency of meetings, the rules of procedure of the LTC can provide useful language that can serve as a basis for drafting the rules of procedure of the STB. There are also further issues requiring consideration such as:

- The modalities through which the STB will interact with other bodies under the Agreement;

- The process for the STB to draw upon advice from other relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies (IFBs) as well as other scientists and experts, and how it may be determined which are relevant [as per Article 49(3)];

- Interpretation of “relevant” traditional knowledge and “suitable qualifications” [as per Article 49(2)];

- Enabling conditions and mechanisms and capacity-building needs for participation in STB.

In addressing these issues, it is pertinent to consider lessons from existing bodies including, but of course not limited to, the LTC. The BBNJ Agreement is an important opportunity to institute modern best practice principles for expert advice. In doing so there may not be a need to fully reinvent the wheel, just to ensure that the wheel is road-worthy for the path that is to be traveled.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CG: Writing – review & editing. HH-D: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Nippon Foundation for supporting this research through the Nippon Foundation – University of Edinburgh Ocean Voices Programme.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The BBNJ Agreement—https://www.un.org/bbnjagreement/sites/default/files/2024-08/Text%20of%20the%20Agreement%20in%20English.pdf.

2. ^Matters to be addressed at the first meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction—Note by the Secretariat—A/AC.296/2024/3—https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n24/114/28/pdf/n2411428.pdf. April 2024.

3. ^Statement of the Co-Chair of the Preparatory Commission for the Entry into Force of the Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction and the Convening of the First Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Agreement at the closing of the organizational meeting—A/AC.296/2024/4—https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n24/190/93/pdf/n2419093.pdf. July 2024.

4. ^Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 24 April 2024—Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction—A/RES/78/272 https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n24/117/55/pdf/n2411755.pdf. April 2024.

5. ^The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is an autonomous international organization established under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1994 Agreement). The ISA is the organization through which States Parties to UNCLOS organize and control all mineral-resources-related activities in the Area for the benefit of humankind as a whole. In so doing, ISA has the mandate to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects that may arise from deep-seabed-related activities. https://www.isa.org.jm/about-isa/.

6. ^Experiential knowledge is increasingly recognized as an important form of evidence and can have a significant influence on the effectiveness of outcomes in environmental conservation and governance (Fazey et al., 2006).

7. ^The “Area” is a term of art under UNCLOS and refers to the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction. See UNCLOS, Article 1(1).

8. ^Of the five bodies established by the BBNJ Agreement, only the ABS Committee has the number of members specified–15 members—Article 15(2).

9. ^Decision of the Council of the International Seabed Authority relating to the election of members of the Legal and Technical Commission—ISBA/27/C/41—see operative paragraph 3—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/ISBA_27_C_41-2211998E.pdf. July 2022.

10. ^See, for example, Letter dated 8 July 2020 from the facilitator appointed by the Council regarding the election of members of the Legal and Technical Commission addressed to the Secretary-General of the International Seabed Authority—ISBA/26/C/20—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ISBA_26_C_20-2009608E.pdf. July 2020.

11. ^Functions, working practices and anticipated program of work of the Legal and Technical Commission for the period from 2023 to 2027—Note by the Secretariat—ISBA/28/LTC/2—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2301444E.pdf. January 2023.

12. ^Election of members of the Legal and Technical Commission—Report of the Secretary-General—ISBA/23/C/2—see operative paragraph 23—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/isba-23c-2en.pdf. November 2016.

13. ^Election of members of the Legal and Technical Commission—Report of the Secretary-General—ISBA/24/C/14—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/isba24c-14-en.pdf. May 2018.

14. ^Legal and Technical Commission membership—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/LTC_Membership_1997-2027_Rev_January_2024.xlsx.

15. ^The other committees established by the Agreement also refer to the need for membership to take into account gender balance [Article 15(2); Article 46(2); Article 52(14); Article 55(2)].

16. ^For example, the COP is to review and evaluate the implementation of the Agreement to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the provisions contained therein (Article 47.6; Article 47.8).

17. ^Election of members of the Legal and Technical Commission—Report of the Secretary-General—ISBA/26/C/14—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ISBA_26_C_14-2006125E.pdf. April 2020.

18. ^Decision of the Council of the Authority concerning the Rules of Procedure of the Legal and Technical Commission—ISBA/6/C/9—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/isba_6_c_9_rop_of_ltc.pdf. July 2000.

19. ^Functions, working practices and anticipated program of work of the Legal and Technical Commission for the period from 2023 to 2027—Note by the Secretariat—ISBA/28/LTC/2—see operative paragraph 23—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2301444E.pdf. January 2023.

20. ^Gaebel et al. (under review). Practical considerations for the development of a clearing-house mechanism for marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. Front. Ocean Sustain.

21. ^Rules of Procedure of the Legal and Technical Commission—Rule 15—In the exercise of its functions, the Commission may, where appropriate, consult another commission, any competent organ of the United Nations or of its specialized agencies or any international organizations with competence in the subject-matter of such consultation.

22. ^Decision of the Council of the Authority concerning the Rules of Procedure of the Legal and Technical Commission—ISBA/6/C/9—https://www.isa.org.jm/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/isba_6_c_9_rop_of_ltc.pdf. July 2000.

23. ^Rule 11 of the Rules of Procedure of the LTC does mandate that, before assuming their duties, members of the Commission must make a written declaration which includes affirmation that, among other things, the member will perform his/her duties “honorably, faithfully, impartially, and conscientiously”.

24. ^Report of the Preparatory Committee established by General Assembly resolution 69/292—See Part III. Recommendations of the Preparatory Commission. Section A. https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n17/237/36/pdf/n1723736.pdf. July 2017.

References

Andresen, S., Baral, P., Hoffman, S. J., and Fafard, P. (2018). What can be learned from experience with scientific advisory committees in the field of international environmental politics? Glob. Chall. 2:1800055. doi: 10.1002/gch2.201800055

Ardron, J., Lily, H., and Jaeckel, A. (2023). “Public participation in the governance of deep-seabed mining in the Area,” in Research Handbook on International Marine Environmental Law (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 361–384.

Behdinan, A., Gunn, E., Baral, P., Sritharan, L., Fafard, P., Hoffman, S. J., et al. (2018). An overview of systematic reviews to inform the institutional design of scientific advisory committees. Glob. Chall. 2:1800019. doi: 10.1002/gch2.201800019

Caldeira, M., Sekinairai, A. T., and Vierros, M. (2025). Weaving science and traditional knowledge: toward sustainable solutions for ocean management. Mar. Pol. 174:106591. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2025.106591

De Santo, E. M., Mendenhall, E., Nyman, E., and Tiller, R. (2020). Stuck in the middle with you (and not much time left): the third intergovernmental conference on biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Pol. 117:103957. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103957

Fazey, I., Fazey, J. A., Salisbury, J. G., Lindenmayer, D. B., and Dovers, S. (2006). The nature and role of experiential knowledge for environmental conservation. Environ. Conserv. 33, 1–10. doi: 10.1017/S037689290600275X

Gaebel, C., Novo, P., Johnson, D. E., and Roberts, J. M. (2024). Institutionalising science and knowledge under the agreement for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ): stakeholder perspectives on a fit-for-purpose Scientific and Technical Body. Mar. Pol. 161:105998. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105998

Gjerde, K. M., Clark, N. A., Chazot, C., Cremers, K., Harden-Davies, H., Kachelriess, D., et al. (2022). Getting beyond yes: fast-tracking implementation of the United Nations agreement for marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. NPJ Ocean Sustain. 1:6. doi: 10.1038/s44183-022-00006-2

Goettsche-Wanli, G. (2019). “Gender and the Law of the Sea: a Global Perspective,” in Gender and the Law of the Sea (Leiden: Brill Nijhoff), 25–82.

Gopinathan, U., Hoffman, S. J., and Ottersen, T. (2018). Scientific advisory committees at the World Health Organization: a qualitative study of how their design affects quality, relevance, and legitimacy. Glob. Chall. 2:1700074. doi: 10.1002/gch2.201700074

Hassanali, K. (2022). Participating in negotiation of a new ocean treaty under the law of the sea convention—experiences of and lessons from a group of small-island developing states. Front. Mar. Sci. 9”902747. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.902747

Jaeckel, A., Harden-Davies, H., Amon, D. J., van der Grient, J., Hanich, Q., van Leeuwen, J., et al. (2023). Deep seabed mining lacks social legitimacy. NPJ Ocean Sustain. 2:1. doi: 10.1038/s44183-023-00009-7

Jouffray, J. B., Blasiak, R., Norström, A. V., Österblom, H., and Nyström, M. (2020). The blue acceleration: the trajectory of human expansion into the ocean. One Earth 2, 43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.12.016

Kitada, M., and Rodríguez-Chaves, M. (2024). Advancing gender equality in contemporary ocean affairs. Int. J. Mar. Coastal Law 39, 508–518. doi: 10.1163/15718085-bja10199

Lixinski, L. (2024). Integrating culture, heritage, and identity in deep seabed mining regulation. AJIL Unbound 118, 78–82. doi: 10.1017/aju.2024.7

Long, R. (2021). “Beholding the emerging biodiversity agreement through a looking glass: what capacity-building and gender equality norms should be found there?,” in Marine Biodiversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction, 241–272.

Long, R., and Chaves, M. R. (2015). Anatomy of a new international instrument for marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. Environ. Liabil 6, 213–229. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1883467

Mendenhall, E., De Santo, E., Jankila, M., Nyman, E., and Tiller, R. (2022). Direction, not detail: progress towards consensus at the fourth intergovernmental conference on biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Pol. 146:105309. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105309

Mendenhall, E., Santo, E., Nyman, E., and Tiller, R. (2019). A soft treaty, hard to reach: the second inter-governmental conference for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Pol. 108:103664. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103664

Mendenhall, E., Tiller, R., and Nyman, E. (2023). The ship has reached the shore: the final session of the ‘Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction'negotiations. Mar. Pol. 155:105686. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105686

Morgera, E. (2021). “The relevance of the human right to science for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction: a new legally binding instrument to support co-production of ocean knowledge across scales,” in International Law and Marine Areas Beyond National jurisdiction, 242–274. Brill Nijhoff.

Morgera, E., and Lily, H. (2022). Public participation at the International Seabed Authority: an international human rights law analysis. Rev. Eur. Compar. Int. Environ. Law 31, 374–388. doi: 10.1111/reel.12472

Morgera, E., McQuaid, K., La Bianca, G., Niner, H., Shannon, L., Strand, M., et al. (2023). Addressing the ocean-climate nexus in the BBNJ agreement: strategic environmental assessments, human rights and equity in ocean science. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 38, 447–479. doi: 10.1163/15718085-bja10139

Mulalap, C. Y., Frere, T., Huffer, E., Hviding, E., Paul, K., Smith, A., et al. (2020). Traditional knowledge and the BBNJ instrument. Mar. Pol. 122:104103. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104103

Orangias, J. (2022). The nexus between international law and science: an analysis of scientific expert bodies in multilateral treaty-making. Int. Commun. Law Rev. 25, 60–93. doi: 10.1163/18719732-bja10068

Popova, E., Vousden, D., Sauer, W. H., Mohammed, E. Y., Allain, V., Downey-Breedt, N., et al. (2019). Ecological connectivity between the areas beyond national jurisdiction and coastal waters: safeguarding interests of coastal communities in developing countries. Mar. Pol. 104, 90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.02.050

Smith, A., and Huffer, E. (2023). Protecting pacific ocean biodiversity: the role of intangible cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and the United Nations mechanisms. Histor. Environ. 33, 42–60.

Tessnow-von Wysocki, I., and Vadrot, A. B. (2020). The voice of science on marine biodiversity negotiations: a systematic literature review. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:614282. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.614282

Tessnow-von Wysocki, I., and Vadrot, A. B. (2024). Pathways of scientific input into intergovernmental negotiations: a new agreement on marine biodiversity. Int. Environ. Agreem. Pol. Law Econ. 24, 325–348. doi: 10.1007/s10784-024-09642-0

Tiller, R., De Santo, E., Mendenhall, E., and Nyman, E. (2019). The once and future treaty: towards a new regime for biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Pol. 99, 239–242. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.10.046

Tiller, R., and Mendenhall, E. (2023). And so it begins—The adoption of the ‘Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction'treaty. Mar. Pol. 157:105836. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105836

Tiller, R., Mendenhall, E., De Santo, E., and Nyman, E. (2023). Shake it off: negotiations suspended, but hope simmering, after a lack of consensus at the fifth intergovernmental conference on biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction. Mar. Pol. 148:105457. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105457

van den Hove, S., and Sharman, M. (2017). “Interfaces between science and policy for environmental governance: lessons and open questions from the European Platform for Biodiversity Research Strategy.” in Interfaces Between Science and Society (Oxfordshire: Routledge), 185–208.

Vierros, M. K., Harrison, A. L., Sloat, M. R., Crespo, G. O., Moore, J. W., Dunn, D. C., et al. (2020). Considering indigenous peoples and local communities in governance of the global ocean commons. Mar. Pol. 119:104039. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104039

Keywords: biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction, scientific advisory bodies, ocean governance, areas beyond national jurisdiction, UNCLOS

Citation: Hassanali K, Gaebel C and Harden-Davies H (2025) Considerations in the set up and functioning of the Scientific and Technical Body under the BBNJ Agreement—lessons from the Legal and Technical Commission of the International Seabed Authority. Front. Ocean Sustain. 3:1572943. doi: 10.3389/focsu.2025.1572943

Received: 07 February 2025; Accepted: 13 March 2025;

Published: 03 April 2025.

Edited by:

Sebastian Christoph Alexander Ferse, IPB University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Yen-Chiang Chang, Dalian Maritime University, ChinaMara Ntona, University of Strathclyde, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Hassanali, Gaebel and Harden-Davies. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kahlil Hassanali, a2FobGlsX2hhc3NhbmFsaUBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==; a2FobGlsLmhhc3NhbmFsaUBnb3YudHQ=

Kahlil Hassanali

Kahlil Hassanali Christine Gaebel

Christine Gaebel Harriet Harden-Davies2

Harriet Harden-Davies2