- 1Clinical Medical College, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 2Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 3Nanjing Hospital of Chinese Medicine Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

- 4Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Xinglin College, Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Background: This case–control study aimed to examine the association between the frequency of potentially risky beverage consumption, levels of anxiety, and the prevalence of endometrial polyps.

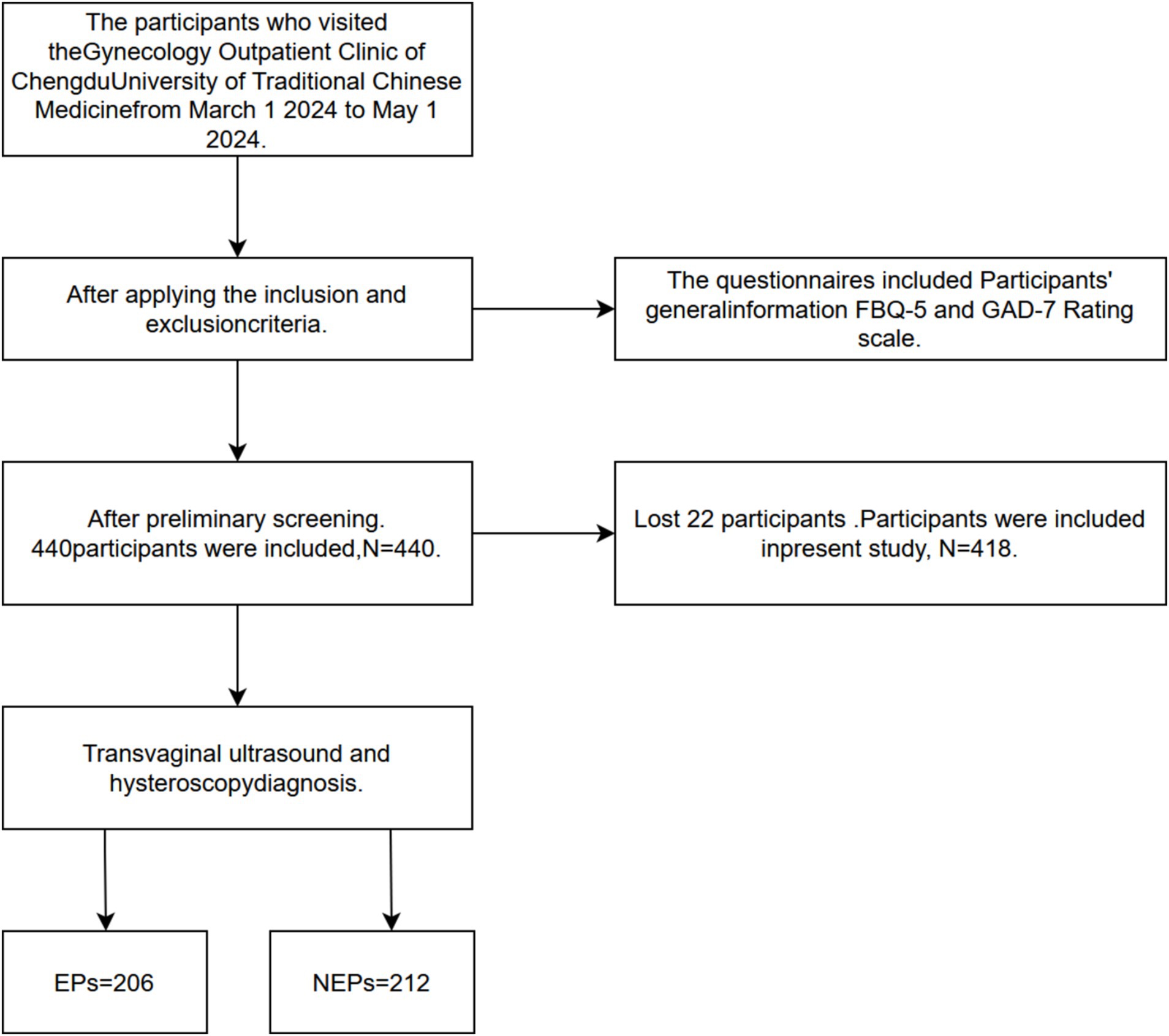

Methods: A total of 418 participants were enrolled in the study, comprising 206 cases and 212 controls. The case group consisted of patients who visited the gynecological clinic at the Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and were diagnosed with endometrial polyps (Eps) based on international diagnostic criteria. The control group consisted of women of childbearing age who visited the gynecological clinic with similar clinical symptoms but did not have EPs. Basic information, consumption of potentially risky beverages (PRB), and anxiety levels for both groups were collected through a questionnaire survey. Finally, the relationship between the frequency of PRB consumption, anxiety levels, and the prevalence of EPs was evaluated.

Results: In this study, we identified a significant positive association between the consumption of PRB and the prevalence of EPs. PRB intake was categorized into three groups based on the cumulative total score: 5–8 for the Low potentially risky beverages (LPRB) intake group, 9–12 for the medium potentially risky beverages (MPRB) intake group, and 13–21 for the high potentially risky beverages (HPRB) intake group. The results revealed that PRB consumption frequency was significantly associated with EPs (OR: 2.348, 95% CI: 1.153–4.78), with higher PRB intake correlating with an increased risk of EPs (p-value: 0.014). However, no significant difference was observed between the LPRB, MPRB, HPRB intake frequency groups and the different levels of anxiety (p-value: 0.793).

Conclusion: Increased consumption of PRB was clearly associated with a greater risk of EPs, and over half of the participants exhibited varying degrees of anxiety. These findings suggest that the risk of EPs can be mitigated by controlling beverage intake and highlight the need for increased attention to women’s mental health.

Clinical trial registration: NCT06295510.

Introduction

Endometrial polyps (EPs) are common gynecological conditions and represent a frequent intrauterine lesion resulting from local hyperplasia of the endometrium, primarily affecting women of childbearing age. Epidemiological studies indicate that EPs account for 24 to 25% of gynecological diseases in Chinese women (1). Moreover, the recurrence rate of Eps is high (2). The incidence of EPs is age-dependent, contributing to 10–40% of abnormal uterine bleeding before menopause and 10.1–38.0% after menopause (3). Most scholars believe that the pathogenesis of EPs is related to hormonal imbalances and inflammation and that factors such as obesity, advanced age, estrogen stimulation, and angiogenesis are closely related to the occurrence and progression of endometriosis (4). The clinical symptoms of EPs are not typical and include heavy menstrual bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding, and prolonged menstrual duration. EPs not only affect the quality of life of patients but are also are directly associated with reduced fertility (5). Studies have shown that EPs can obstruct fallopian tube opening and occupy space in the uterine cavity, thus obstructing sperm transport and embryo implantation. In addition, the local inflammatory response mediated by EPs affects sperm survival and inhibits embryo implantation and development. Patients with EPs experience reduced endometrial receptivity and sexual intercourse frequency, ultimately resulting in lower pregnancy rates (6).

According to the most recent survey, the probability of a combined diagnosis of EPs in women with unexplained infertility ranges from 16.5 to 26.5%, while the incidence of primary infertility ranges from 3.8 to 38.5%, and the incidence of secondary infertility ranges from 1.8 to 17% (7). Currently, there is no effective treatment for EPs. Hysteroscopic endometrial resection is the preferred method for treating EPs, but postoperative recurrence rates remain high, ranging from 33.33 to 52% (8); as follow-up time increases, the recurrence rate of EPs also rises. Consequently, identifying effective prevention and treatment strategies has become an urgent issue that requires resolution.

A large number of studies have shown that changes in dietary structure and intake are important factors in disease prevention. Although no direct link has been found between dietary intake and EPs, several studies indicate a significant association between different diets and endometrial-related diseases. Sakine Ghasemisedaghat et al. reported that the consumption of plant protein and vitamin K could reduce the incidence of endometriosis, whereas the consumption of animal protein, haem iron, and a high glycemic load was associated with an increased incidence of endometriosis (9). SHIVAPPA N et al. reported a moderate positive correlation between high glycemic load (but not the glycemic index) and endometrial cancer (10).

In recent years, more attention has been paid to the adjustment of dietary structure, but the harm of beverage intake to health has been ignored. The increase of beverage intake is also an important risk factor leading to the increase of chronic diseases. Studies have shown that milk tea, carbonated drinks, and sugar-sweetened beverages are significantly associated with increased depression in college students (11), carbonated drinks have been linked to osteoporosis and type 2 diabetes (12); sugar-sweetened beverages have shown the strongest harmful effects, with clear associations with various health outcomes (13); caffeine intake is associated with fluctuations in estrogen levels (14); and soy milk, which contains a high concentration of isoflavones, is related to hormonal fluctuations, including estrogen levels, in women (15). The high contents of sugars, unsaturated fats, additives, hormones, proinflammatory substances, and other components in these beverages may pose significant health risks (16). Considering the varying degrees of harm these five beverages may cause to human health, carbonated drinks, soy milk, sugar-sweetened beverages, milk tea, and coffee were classified as PRB in this study (12). This study evaluated the intake of these beverages and examined the correlation between their consumption and the incidence of EPs. There is a well-established relationship between the occurrence of EPs and the levels of hormones as well as proinflammatory substances (17). It can be speculated that the increased intake of these PRB may be a key factor contributing to the rising incidence of EPs. This study aims to clarify the relationship between the incidence of EPs, the intake of PRB, and anxiety levels, thereby providing evidence-based insights to assist in dietary recommendations and the prevention of EPs among female patients.

Methods

Study design, population, and sample size

In this study, women of childbearing age who attended the gynecological outpatient department of the Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine between 1st Mar 2024 and 1st May 2024 were selected as study participants, and the sample size was determined via the following Equation 1,

In this study, r represents the case-to-control ratio, which is set to 1, indicating an equal number of cases and controls. Zα/2 represents the standard normal variable for a significance level of 0.05/2, which equals 1.96, whereas Zβ indicates a power of 90%, corresponding to a value of 1.28. P1 denotes the proportion of cases, specifically the prevalence of EPs reported in previous studies, which is 0.14. P2 represents the proportion of the control group. Following extensive discussions between the author and statisticians, it is assumed that the proportion of gynecological patients of childbearing age without EPs is 0.27. P is the average proportion of cases to the control group, which is calculated as P1 + P2. After calculation, the required sample size was determined to be 206. To ensure adequate age representation in matching cases and controls, as well as the validity of the sample size, we plan to recruit 220 cases and 220 controls. To mitigate potential recall bias, a contradictory response option was added to assess the accuracy of the questionnaire responses. If any discrepancies were identified between the presurvey and postsurvey answers, the corresponding questionnaire was excluded. Additionally, some participants expressed concerns about information security; as a result, 22 participants opted to withdraw from the survey. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 206 valid questionnaires from the case group and 212 from the control group (Figure 1). The tool used in Figure 1,1 The tool used in Figure 2 is GraphPad Prism 8.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women aged 18–49 years who present at the gynecologic clinic will be eligible for inclusion in this study. The inclusion criteria for the study group were as follows: (1) aged between 18 and 49 years; (2) had a diagnosis of EPs confirmed by transvaginal ultrasound; (3) had primary complaints, including intermenstrual bleeding, irregular menstruation, abnormal uterine bleeding, dysmenorrhea, or excessive menstrual bleeding; and (4) provided informed consent after the study’s purpose was explained. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) inability to accurately recall beverage intake 1 month prior; (2) accurate recall of beverage intake 1 month prior but with logical inconsistencies; (3) The use of hormonal medications for more than 1 month, including contraceptives, estrogen, progestins, and other related drugs; (4) history of long-term hormonal drug use; and (5) presence of significant mental disorders. Patients with similar complaints who do not have EPs will be assigned to the control group.

Questionnaire design

General questionnaire

The general questionnaire collected basic demographic and lifestyle information, including height, weight, age, residence (with consideration of environmental pollution levels), education level, family income per capita, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, marital history, sexual history, and abortion history.

FBQ-5 beverage frequency scale

A self-designed Beverage Frequency Questionnaire (FBQ-5) was used to assess participants’ beverage consumption over the past month. To minimize recall bias, a contradictory option was included to enhance the accuracy of responses. The beverage categories included carbonated drinks, soy milk, sugar-sweetened beverages, milk tea, and coffee. Beverage consumption frequencies were classified as follows: ‘almost never,’ ‘occasionally’ (0–1 times per week), ‘sometimes’ (1–2 times per week), ‘often’ (3–4 times per week), and ‘always’ (5 or more times per week), with scores ranging from 1 to 5, where higher scores indicated more frequent consumption of PRB. The cumulative score ranged from 5 to 25. Based on quartile ranges, scores of 5–8 were categorized into the LPRB group, 9–12 into the MPRB group, and 13–25 into the HPRB group. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire were assessed, with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.893 and a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.788, indicating good construct validity.

GAD-7 anxiety rating scale

Psychological anxiety is prevalent among women, as indicated by several studies. Therefore, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale was used to assess the anxiety levels of participants in this study (18). This instrument has been validated as a reliable tool for assessing anxiety in the Chinese population, including pregnant women (19). Seven items with typical anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks were measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale: 0 = never, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half of the days, and 3 = nearly every day. A cut-off score of 5 or higher was considered to indicate anxiety (20). In this study, anxiety levels in women were assessed using seven questions from the GAD-7 scale. Based on the cumulative GAD-7 score, anxiety severity was classified as follows: none (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), and severe (15–21).

Statistical methods

Data analysis was conducted via SPSS 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, United States). Cronbach’s alpha, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test were employed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the FBQ-5 and GAD-7 scales. Continuous variables are expressed as the means ± standard deviations, and independent sample tests were used to compare differences between the means of continuous variables among cases and controls. Differences among multiple groups were assessed via analysis of variance (ANOVA). In cases of significant differences among groups, pairwise comparisons were conducted via the least significant difference (LSD) method. The Spearman correlation test was used to analyze the relationships among categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify independent predictors of the prevalence of EPs. The significance level was set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed), and p < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

General data statistics of enrolled patients

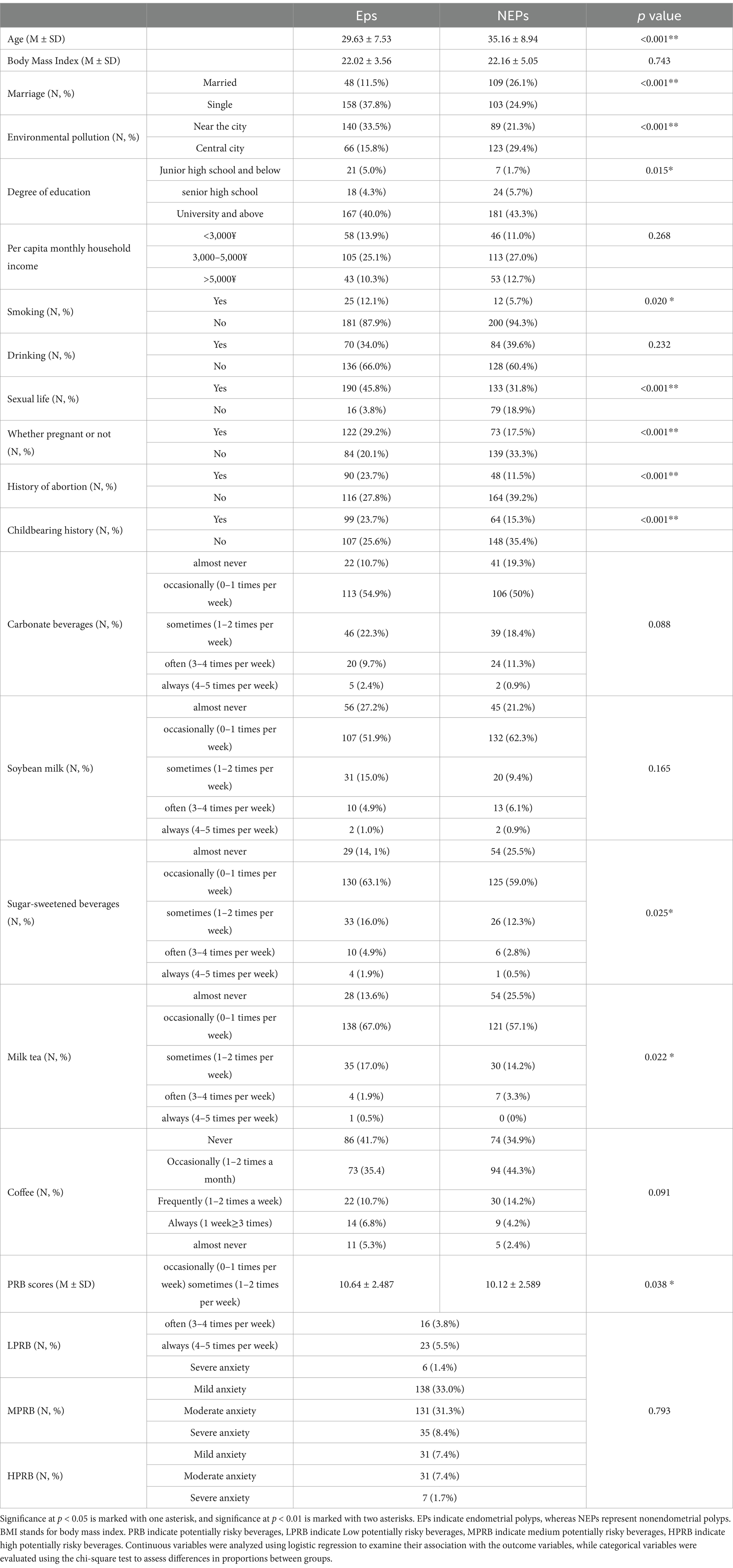

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the case and control groups, as well as the frequency of consumption of five types of PRB. A total of 418 participants were included, with 206 in the EPs group and 212 in the nonendometrial polyps (NEPs) group. As shown in the table, the average age of the EPs group (29.63 ± 7.53) was significantly younger than that of the NEPs group (35.16 ± 8.94), suggesting that EPs tend to occur at a younger age. The incidence of EPs was also significantly associated with marital status (p < 0.001), environmental pollution (p < 0.001), education level (p = 0.015), sexual activity (p < 0.001), pregnancy history (p < 0.001), abortion history (p < 0.001), smoking history (p = 0.020), and reproductive history (p < 0.001), with all variables showing statistical significance (p < 0.05). However, no significant difference was observed between the different levels of anxiety and the low, medium, and high PRB intake groups (p = 0.793). Based on these findings, we conclude that, compared to the control group, patients with EPs tend to be younger, and women who are sexually inactive have a significantly lower probability of developing EPs compared to those who are sexually active. Additionally, women with higher education levels are less likely to have EPs than those with lower education levels. Moreover, the average cumulative scores for the frequency of PRB intake were significantly higher in the EPs group than in the control group (p = 0.038). However, no significant differences were found in the incidence of EPs with respect to family per capita monthly income (p = 0.268) or drinking history (p = 0.232).

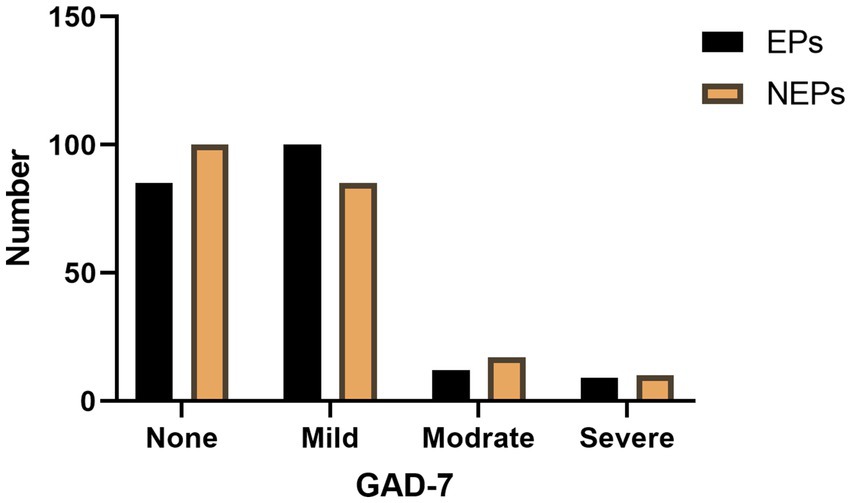

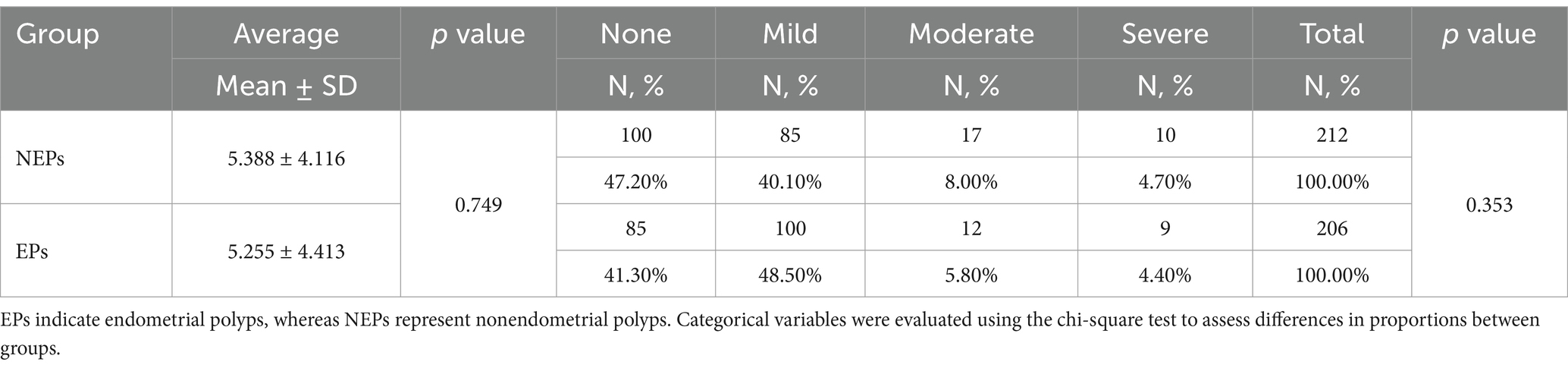

The relationship between anxiety and EPs

Table 2 analyzes the relationship between different levels of anxiety and Eps. It can be concluded from the table that there is no statistical significance between the average cumulative score of anxiety level and Eps (p = 0.749), and there is no statistical significance between different levels of anxiety and Eps (p = 0.353). Table 1 also analyzes the relationship between LPRB, MPRB, HPRB and different anxiety levels, and the statistical result (p = 0.793) shows that there is no statistical significance between PRB intake and different anxiety levels. Based on the above results, we can conclude that anxiety is a universal phenomenon in women of childbearing age, and more than half of the people who participated in this study have some degree of anxiety. Appeal to the social audience of women’s mental health.

Relationship Between PRB and EPs

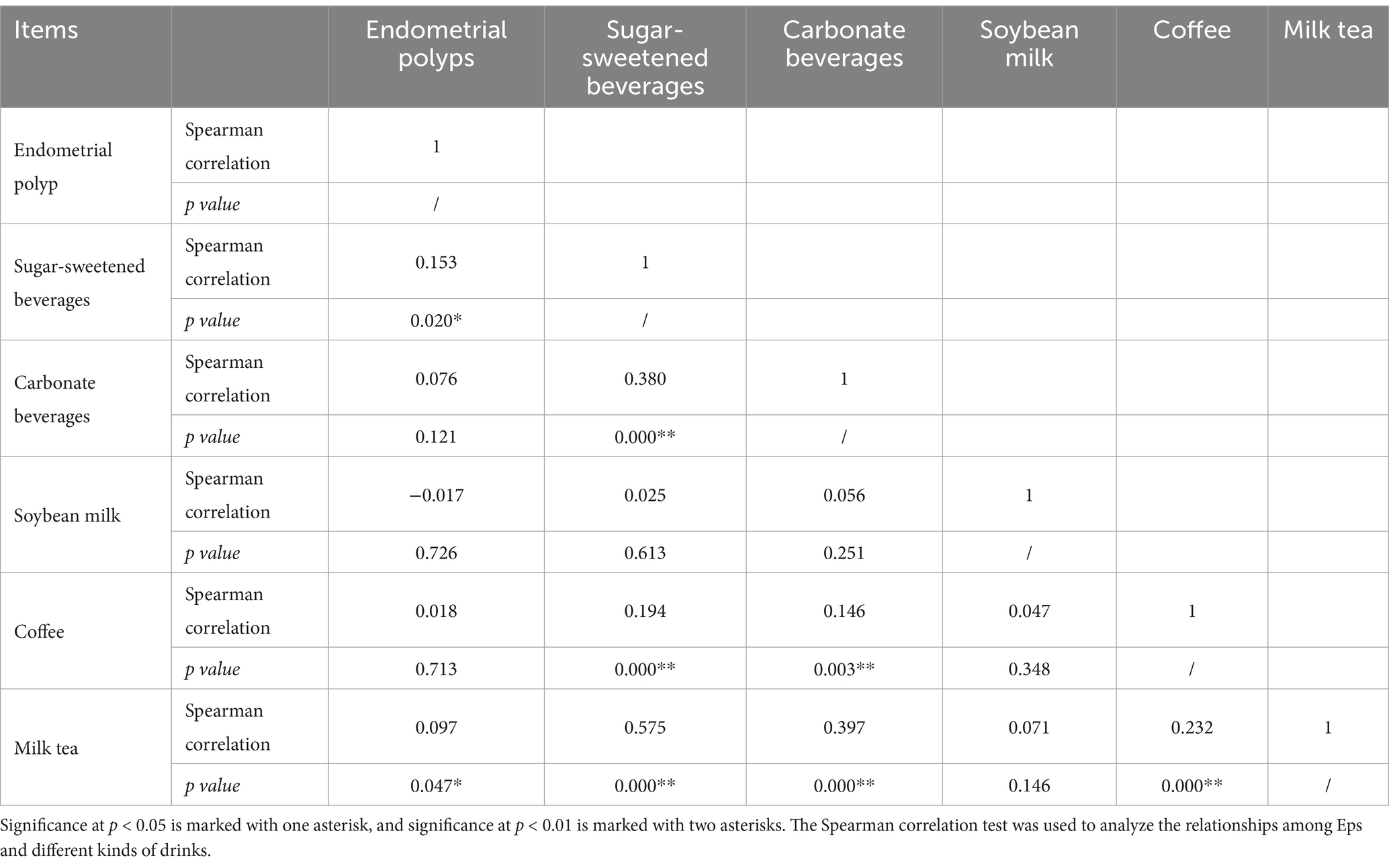

The Spearman correlation test was employed to assess the relationship between five types of PRB and the incidence of EPs (Table 3). The analysis revealed that sugar-sweetened beverages (p = 0.020) and milk tea (p = 0.047) were significantly associated with the occurrence of EPs. These findings suggest that higher consumption of milk tea and sugar-sweetened beverages may increase the risk of developing EPs.

Table 3. Analysis of the correlation between five types of potentially risky beverages and the incidence of endometrial polyps.

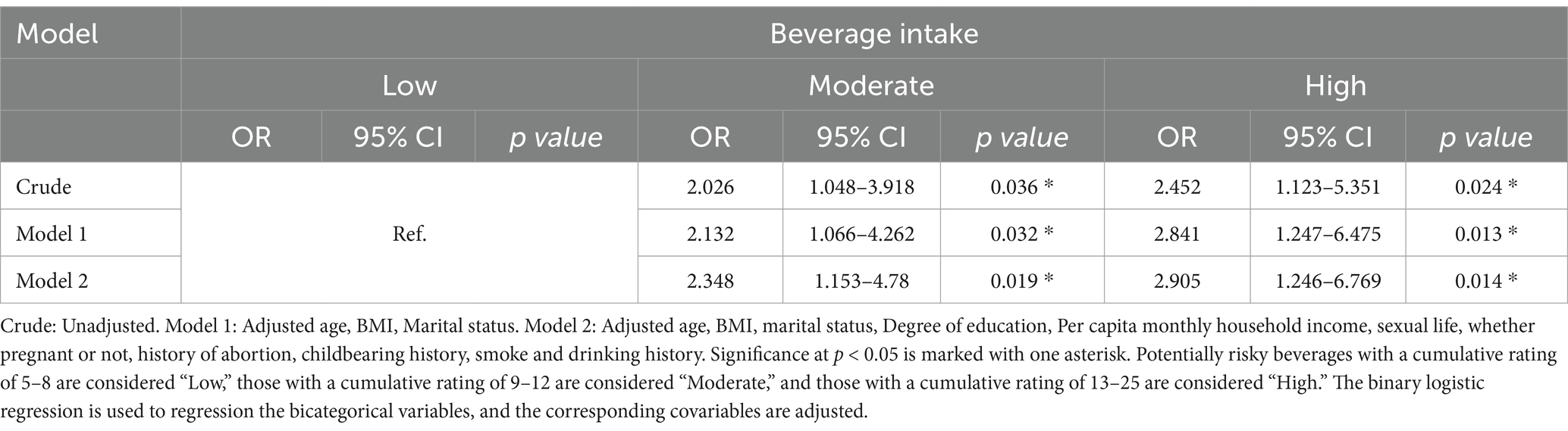

This study employs logistic regression to investigate the relationship between PRB intake and the risk of developing EPs (Table 4). In the analysis of unadjusted covariates, the results indicate that the MPRB drinks has an odds ratio (OR) of 2.026 (95% CI: 1.048–3.918, p = 0.036), whereas the high-income group has an OR of 2.452 (95% CI: 1.123–5.351, p = 0.024). Both groups had odds ratios greater than 1, suggesting that PRB intake may be associated with an elevated risk of ectopic pregnancies (EPs). Model 1 adjusts for age, body mass index, marital status, and other relevant factors, and the results remain consistent with the unadjusted analysis. Model 2 adjusts for age, body mass index, marital status, education level, household income, sexual history, pregnancy history, history of miscarriage and childbirth, and smoking and drinking habits. The results remain consistent with those of the previous models. Overall, the findings suggest that MPRB and HPRB intake are associated with an elevated risk of EPs, with odds ratios of 2.348 (95% CI: 1.153–4.780, p = 0.019) and 2.905 (95% CI: 1.2466.769, p = 0.0014), respectively.

Table 4. Regression analysis of logistics between potentially risky beverages and endometrial polyps.

Discussion

This case–control study found that high frequency consumption of PRB was associated with an increased prevalence of EPs. This is the first paper on the relationship between potentially risky beverage intake and the prevalence of EPs. We also explored the association between different levels of anxiety and EPs, which has certain guiding implications for women’s health.

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, despite the lack of statistical significance between anxiety levels and EPs (p = 0.353), over half of the women in both the EPs group (58.7%) and the NEPs group (52.8%) exhibited varying degrees of anxiety. Anxiety is very common among women and affects their mental health (21). Chronic anxiety can increase the risk of more serious diseases, such as major depressive episodes (22), cardiovascular disease (23), reproductive and postpartum health (24), and menopausal health (25). Dora Koller et al. reported a correlation between endometriosis and women’s mental health (26), and Rooney KL studies revealed a correlation between anxiety and infertility in women (27). Although our study did not identify a significant association between anxiety levels and EPs, the fact that more than half of the participants experienced anxiety highlights the need for increased societal focus on the mental health of women.

We conducted a comprehensive assessment of beverage intake on the basis of beverage type and frequency. The PRB included in this assessment included carbonated drinks, soy milk, sugary beverages, milk tea, and coffee. Current research indicates that excessive consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with the onset of various diseases. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that high sugar intake increases the risk of dental caries, overweight and obesity. Additional studies have shown that the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages can increase the risk of chronic diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, gout, cancer, and premature death, thereby increasing the overall burden of disease (28). A recent review of the evidence regarding the health outcomes of sugar intake, which comprehensively summarized the relationship between dietary sugar intake and multisystem diseases, indicated that high dietary sugar intake typically has a detrimental effect on health, particularly in its association with metabolic diseases (29). The highest level of evidence was for effects on body weight, followed by gout, HDL cholesterol, and metabolic syndrome (12). Currently, the relationship between excessive sugar intake and EPs remains inadequately understood; however, metabolic disturbances associated with high sugar consumption may contribute to an increased risk of EPs. Excessive sugar intake, for example, can lead to obesity, and adipose tissue in obese women secretes elevated levels of estrogen. This excess estrogen can stimulate endometrial hyperplasia, thereby increasing the risk of polyp formation (30). Furthermore, excessive sugar intake may contribute to the development of insulin resistance, which is closely associated with endocrine disorders, including polycystic ovary syndrome (31). A high-sugar diet promotes the occurrence of chronic low-grade inflammation in the body; especially under hyperglycemic conditions, the body’s immune system may be disrupted, and more proinflammatory cytokines may be produced (32). Long-term inflammation may lead to abnormal hyperplasia of the endometrium and the formation of polyps (33).

Milk tea has become a highly popular daily beverage in China. Unlike traditional tea, milk tea contains not only tea but also relatively high levels of sugar, creamers, saturated fat, and additives. High consumption of sugar and creamers increases the risk of obesity, whereas excessive saturated fat negatively impacts lipid metabolism and increases cardiovascular risk (34). The correlation analysis revealed that milk tea intake was significantly associated with EPs (OR = 0.097, p = 0.047), which aligns with the adverse health effects associated with sugar-sweetened beverages.

Our study revealed no significant associations between coffee, soy milk, or carbonated beverages and the prevalence of EPs. However, this did not imply that these beverages are either safe or harmful. Current research on coffee presents mixed findings. Caffeine is the primary component of coffee. One study examining the relationship between caffeine and estrogen levels reported that increased caffeine intake may increase estrogen levels (14). Caffeine consumption is associated with favorable effects on a variety of health outcomes in women, including some diseases related to estrogen metabolism (35). Moreover, caffeine intake is often linked to increased social stress, greater life burdens, reduced physical activity, and poor sleep quality. Unhealthy lifestyles, characterized by poor psychological well-being, inadequate sleep, and a lack of exercise, are frequently associated with a higher incidence of chronic diseases (36). Further cohort studies and gene-related research are necessary to investigate the potential causal relationship between coffee consumption and endometrial health. This study revealed that soy milk and other soy products contain phytoestrogens, primarily isoflavones, which have a weak effect, and typical dietary intake does not result in significant endocrine disruption (37). Conversely, these phytoestrogens may have a beneficial effect on regulating estrogen levels in the body, acting as “antiestrogens” when estrogen levels are excessively high. Alternatively, when estrogen levels are low, these compounds may exert a mild estrogenic effect, aiding in the regulation of hormonal balance (38). Additionally, our correlation analysis indicates that there may be a beneficial relationship between the two (OR = −0.17, p = 0.726).

Sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages, commonly referred to as soft drinks, are made by carbonating liquid with carbon dioxide gas and sweetening the mixture. Their main components include white sugars, coloring agents, flavorings, carbonated water, acidulants, and sweeteners (39). Carbonated beverages are widely consumed in daily life. An increasing body of research has identified a strong link between the long-term consumption of carbonated beverages and numerous health issues (40), including excessive caloric intake, reduced consumption of dairy products and other nutrients, and a heightened risk of dental caries, osteoporosis, depression, behavioral disorders, and other psychological problems (41). This consumption is also closely associated with obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, gout, and high blood pressure, particularly in children and adolescents (42), gout is closely associated with hypertension (43). A case–control study examining the relationship between carbonated beverages and obesity revealed a monotonic, linear dose–response association between Sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages consumption and obesity (p = 0.02), as well as increases in BMI and percentage of body fat mass (39). Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and age at menarche in a prospective study of American girls (44). Frequent consumption of carbonated beverages is associated with earlier menarche, and a 1-year decrease in the age of menarche correlates with a 5% increased risk of breast cancer (45, 46). Suggesting a correlation between carbonated beverage consumption and women’s health. Carbonated beverage consumption may induce a state of chronic inflammation in the body, which can result in the production of additional proinflammatory cytokines (47, 48). A chronic inflammatory environment can contribute to the development of EPs (49).

Limitations and prospects of the current study

One of the strengths of this case–control study is that it is the first to examine the relationship between the incidence of EPs and the frequency of consumption of PRB in women of childbearing age, while also exploring the connection between EPs and different levels of anxiety. In everyday life, understanding the intake of PRB among women of reproductive age holds important guiding significance, emphasizing the need for society to pay attention to the dietary habits and mental health of this population.

However, the study has several limitations. The participants were patients from the gynecological outpatient department at Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and the cases were sourced from a specific region, which means the findings primarily reflect the relationship between PRB intake and EPs among women in southwest China. Despite this, all patients with EPs met international diagnostic criteria, and strict inclusion criteria were applied to ensure the accuracy of the results.

The questionnaire was designed to assess the frequency of PRB consumption but did not include a quantitative evaluation of total beverage intake, which limited the ability to analyze the linear correlation between beverage consumption and EPs. However, by categorizing beverage intake based on frequency, it was divided into low, medium, and high levels, which better represented the actual intake patterns to some extent, providing a crucial analytical foundation for investigating the relationship between beverage intake levels and the occurrence of EPs.

Furthermore, since age and reproductive history may influence the risk of EPs, this study controlled for these potential confounders by using logistic regression to ensure the accuracy of the findings. To mitigate recall bias, a contradictory option was included in the questionnaire to verify the accuracy of responses. If contradictory answers were identified, the corresponding data were excluded to ensure the integrity of the dataset.

Despite these limitations, the study was designed in strict accordance with the STROBE observational study guidelines, and the statistical analysis was properly conducted.

Conclusion

Based on the results, there was a significant correlation between increased intake of PRB and a higher prevalence of EPs. Additionally, more than half of the participants exhibited varying degrees of anxiety, underscoring the importance of addressing women’s health concerns in society. This study also provides a valuable reference for future research aiming to quantitatively evaluate the linear relationship between beverage consumption and EPs.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

This observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and registered in the ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT06295510). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

RF: Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine-Wei Shaobin National Renowned Traditional Chinese Medicine Experts Workshop Construction Project, National Renowned Traditional Chinese Medicine Experts Inheritance Workshop Construction Project, project no. 2100601-Chinese Medicine (Ethnic Medicine) Special Project (May 2022–December 2024).

Acknowledgments

Thank you for the great contribution to the field included in the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1538405/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

EPs, Endometrial polyps; NEPs, Nonendometrial polyps; PRB, Potentially risky beverages; LPRB, Low potentially risky beverages; MPRB, Medium potentially risky beverages; HPRB, High potentially risky beverages; FBQ, Beverage frequency questionnaire.

Footnotes

References

1. Linshan, H, and Liangwu, Z. Progress in the treatment of endometrial polyps with Chinese and Western medicine. Chinese Foreign Med Res. (2023) 21:173–7. doi: 10.14033/j.cnki.cfmr.2023.30.042

2. Sasaki, LMP, Andrade, KRC, Figueiredo, A, Wanderley, MDS, and Pereira, MG. Factors associated with malignancy in Hysteroscopically resected endometrial polyps: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2018) 25:777–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.02.004

3. AAGL practice report. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of endometrial polyps. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2012) 19:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.09.003

4. Yunhua, Y, Xishi, L, and Chan, NJ. Fibrosis and expression of estrogen and progesterone receptor in polypoid endometriosis and its clinical significance. J Fudan University (medical edition) (2024) 51:1–9.

5. Al Chami, A, and Saridogan, E. Endometrial polyps and subfertility. J Obstet Gynaecol India. (2017) 67:9–14. doi: 10.1007/s13224-016-0929-4

6. Zhao, T, and Zhijing, S. Management of endometrial polyps in women of childbearing age. Advan modern obstetrics and gynecol. (2023) 32:708–10. doi: 10.13283/j.cnki.xdfckjz.2023.09.011

7. Nijkang, NP, Anderson, L, Markham, R, and Manconi, F. Endometrial polyps: pathogenesis, sequelae and treatment. SAGE Open Med. (2019) 7:2050312119848247. doi: 10.1177/2050312119848247

8. Li, J, Zhaoxia, W, Li, Z, Qingling, R, Zhenzhong, S, and Chengdong, L. Study on the mechanism of regulating Caspase-1/GSDMD signaling pathway by adding Guizhi Poria pills to prevent recurrence of endometrial polyps after operation. Liaoning J Traditional Chinese Med :1–10.

9. Ghasemisedaghat, S, Eslamian, G, Kazemi, SN, Rashidkhani, B, and Taheripanah, R. Association of fertility diet score with endometriosis: a case-control study. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1222018. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1222018

10. Shivappa, N, Hébert, JR, Zucchetto, A, Montella, M, Serraino, D, la, C, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and endometrial cancer risk in an Italian case-control study. Br J Nutr. (2016) 115:138–46. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515004171

11. Xu, H, Yang, Z, Liu, D, Yu, C, Zhao, Y, Yang, J, et al. Mediating effect of physical sub-health in the association of sugar-sweetened beverages consumption with depressive symptoms in Chinese college students: a structural equation model. J Affect Disord. (2023) 342:157–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.09.020

12. Qin, P, Li, Q, Zhao, Y, Chen, Q, Sun, X, Liu, Y, et al. Sugar and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and all-cause mortality: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. (2020) 35:655–71. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00655-y

13. Malik, VS, and Hu, FB. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2022) 18:205–18. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00627-6

14. Sisti, JS, Hankinson, SE, Caporaso, NE, Gu, F, Tamimi, RM, Rosner, B, et al. Caffeine, coffee, and tea intake and urinary estrogens and estrogen metabolites in premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2015) 24:1174–83. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0246

15. Nardi, J, Moras, PB, Koeppe, C, Dallegrave, E, Leal, MB, and Rossato-Grando, LG. Prepubertal subchronic exposure to soy milk and glyphosate leads to endocrine disruption. Food Chem Toxicol. (2017) 100:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.12.030

16. Ma, X, Nan, F, Liang, H, Shu, P, Fan, X, Song, X, et al. Excessive intake of sugar: An accomplice of inflammation. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:988481. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.988481

17. Cicinelli, E, Bettocchi, S, de Ziegler, D, Loizzi, V, Cormio, G, Marinaccio, M, et al. Chronic endometritis, a common disease hidden behind endometrial polyps in premenopausal women: first evidence from a case-control study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2019) 26:1346–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.01.012

18. Spitzer, RL, Kroenke, K, Williams, JB, and Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

19. Tong, X, An, D, McGonigal, A, Park, SP, and Zhou, D. Validation of the generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. (2016) 120:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.11.019

20. Austin, MV, Mule, V, Hadzi-Pavlovic, D, and Reilly, N. Screening for anxiety disorders in third trimester pregnancy: a comparison of four brief measures. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2022) 25:389–97. doi: 10.1007/s00737-021-01166-9

21. Weiss, SJ, Simeonova, DI, Kimmel, MC, Battle, CL, Maki, PM, and Flynn, HA. Anxiety and physical health problems increase the odds of women having more severe symptoms of depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2016) 19:491–9. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0575-3

22. Women and anxiety disorders: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Proceedings of a conference, November 19-21, 2003, Chantilly, Virginia. USA CNS Spectr. (2004) 9:1–16.

23. Wang, X, Gao, D, and Zhang, X. Association of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms with Risk of cardiovascular disease in middle-aged and older Chinese women. Asia Pac J Public Health. (2024) 36:184–91. doi: 10.1177/10105395241237664

24. Cao, LB, Hao, Q, Liu, Y, Sun, Q, Wu, B, Chen, L, et al. Anxiety level during the second localized COVID-19 pandemic among quarantined infertile women: a cross-sectional survey in China. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:647483. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.647483

25. Wang, H, Zhang, Q, Lin, Y, Liu, Y, Xu, Z, and Yang, J. Keep moving to retain the healthy self: the influence of physical exercise in health anxiety among Chinese menopausal women. Behav Sci Basel. (2023) 13:140. doi: 10.3390/bs13020140

26. Koller, D, Pathak, GA, Wendt, FR, Tylee, DS, Levey, DF, Overstreet, C, et al. Epidemiologic and genetic associations of endometriosis with depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. JAMA Netw Open. (2023) 6:e2251214. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.51214

27. Rooney, KL, and Domar, AD. The relationship between stress and infertility. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2018) 20:41–7. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.1/klrooney

28. Shen Liping, WANG, Zhengyuan, FJ, Caicui, DING, and Jiajie, ZANG. Research progress on health hazards and control strategies of sugar-sweetened beverages. Environ Occup Med. (2023) 40:769–74.

29. Huang, Y, Chen, Z, Chen, B, Li, J, Yuan, X, Li, J, et al. Dietary sugar consumption and health: umbrella review. BMJ. (2023) 381:e071609. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071609

30. Agnew, HJ, Kitson, SJ, and Crosbie, EJ. Gynecological malignancies and obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. (2023) 88:102337. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2023.102337

31. Qi, Z, Ping, C, Liping, Y, Jianhua, S, and Zibo, M. The relationship between insulin resistance, hyperandrogenemia and mitochondrial oxidative stress in PCOS. Chinese J Comparative Med. 34:1–6.

32. Ding, Y, Meng, W, Yang, H, Chongqi, Z, Haihua, B, Dan, W, et al. Effect of curcumin analogue H8 on inflammatory factors of human renal tubular epithelial cells in high glucose environment. Chin J Gerontol. (2021) 41:3758–62.

33. Kuai Dan, TANG, Qingtao, LX, Yingmei, WANG, Wenyan, TIAN, and Huiying, ZHANG. Advances in the pathogenesis of endometrial polyps. J Reprod Med. (2024) 33:1109–13.

34. Shi Zechuan, SUN, Zhuo, WANGZ, Song Qi, QU, and Mengying, ZANGJ. Nutritional characteristics of 122 kinds of commercially available milk tea in Shanghai. Chengdu, Sichuan, China: 14th Asian nutrition congress (2023).

35. Hou, C, Zeng, Y, Chen, W, Han, X, Yang, H, Ying, Z, et al. Medical conditions associated with coffee consumption: disease-trajectory and comorbidity network analyses of a prospective cohort study in UK biobank. Am J Clin Nutr. (2022) 116:730–40. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqac148

36. Raza, ML, Haghipanah, M, and Moradikor, N. Coffee and stress management: how does coffee affect the stress response? Prog Brain Res. (2024) 288:59–80. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2024.06.013

37. Scientists reveal a link between soy isoflavone intake and lower risk for coronary heart disease. Chinese J Food Sci Technol. (2020) 20:155.

38. Experts dispel the rumor that drinking soy milk is prone to breast cancer: soy reduces the risk of breast cancer. Soybean. Science. (2016) 35:233.

39. Martin-Calvo, N, Martínez-González, MA, Bes-Rastrollo, M, Gea, A, Ochoa, MC, and Marti, A. Sugar-sweetened carbonated beverage consumption and childhood/adolescent obesity: a case-control study. Public Health Nutr. (2014) 17:2185–93. doi: 10.1017/S136898001300356X

40. Pereira, MA. Sugar-sweetened and artificially-sweetened beverages in relation to obesity risk. Adv Nutr. (2014) 5:797–808. doi: 10.3945/an.114.007062

41. Narita, Z, Hidese, S, Kanehara, R, Tachimori, H, Hori, H, Kim, Y, et al. Association of sugary drinks, carbonated beverages, vegetable and fruit juices, sweetened and black coffee, and green tea with subsequent depression: a five-year cohort study. Clin Nutr. (2024) 43:1395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2024.04.017

42. Hirahatake, KM, Jacobs, DR, Shikany, JM, Jiang, L, Wong, ND, Steffen, LM, et al. Cumulative intake of artificially sweetened and sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in young adults: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Am J Clin Nutr. (2019) 110:733–41. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz154

43. Huffman, MD. Association or causation of sugar-sweetened beverages and coronary heart disease: recalling sir Austin Bradford Hill. Circulation. (2012) 125:1718–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.097634

44. Carwile, JL, Willett, WC, Spiegelman, D, Hertzmark, E, Rich-Edwards, J, Frazier, AL, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and age at menarche in a prospective study of US girls. Hum Reprod. (2015) 30:675–83. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu349

45. Rosner, B, Colditz, GA, and Willett, WC. Reproductive risk factors in a prospective study of breast cancer: the Nurses' health study. Am J Epidemiol. (1994) 139:819–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117079

46. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. (2012) 13:1141–51. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70425-4

47. Liu, S, Manson, JE, Buring, JE, Stampfer, MJ, Willett, WC, and Ridker, PM. Relation between a diet with a high glycemic load and plasma concentrations of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. (2002) 75:492–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.3.492

48. Ludwig, DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. (2002) 287:2414–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2414

Keywords: endometrial polyps, potentially risky beverages, anxiety, female, logistic

Citation: Fu R, Zhang S, Cai C, Wang X, Jiang Y, Zhuang X, Zhang J, Ji X and Yang C (2025) Association between the intake of potentially risky beverages and the occurrence of endometrial polyps: a case–control study. Front. Nutr. 12:1538405. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1538405

Edited by:

Dorota Formanowicz, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, PolandReviewed by:

Nahla Al-Bayyari, Al-Balqa Applied University, JordanMałgorzata Mizgier, Poznan University of Physical Education, Poland

Kalina Maćkowiak, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland

Copyright © 2025 Fu, Zhang, Cai, Wang, Jiang, Zhuang, Zhang, Ji and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ji Xiaoli, aml4aWFvbGkxMDMwQDE2My5jb20=; Chengcheng Yang, MTUwMzkzODU2QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Rui Fu

Rui Fu Shipeng Zhang

Shipeng Zhang Chang Cai1,2

Chang Cai1,2 Yanjie Jiang

Yanjie Jiang Jiating Zhang

Jiating Zhang Xiaoli Ji

Xiaoli Ji