Introduction

The South Asia region is falling significantly short of achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG-2) nutrition targets by 2030 (1). While there has been some progress in the last decade in select nutrition indicators such as exclusive breastfeeding (2012: 47%, 2022: 60%) and stunting among children under five (2012: 40%, 2022: 30%), two barometers reflective of the state of women's nutrition have remain unchanged—children born with low birth weight (25%, 2012 and 2022) and women aged 15–49 years who are anemic (48%, 2012 and 2019) (1). South Asia still hosts 114 million underweight girls and women (50% of the global burden), while a rise in overweight and obesity now also affects 20% of this group in the region (2). Clearly, despite several bouts of intentional efforts by governments, multilateral organizations and civil society, progress to tackle poor maternal nutrition in South Asia has not been swift enough.

To restate the fundamentals, poor maternal nutrition is a key concern because it perpetuates multigenerational cycles of malnutrition. It is a key driver of in-utero malnutrition resulting in children born with low birth weight, which in turn is associated with faltered growth in infancy and future risks of developing diabetes and obesity (3). There is compelling evidence that poor maternal nutrition is caused by interrelated drivers rooted in social injustice—poverty, harmful social and gender norms, low status of women, and low women's self-efficacy are at play alongside the harsh realities of gender segregation in labor markets, wage gaps and time poverty. These experiences remain root drivers of unequal opportunities for women and girls, denying them the power and resources to access nutrition and health services and make choices about what and how much to eat—which is often last and least (4–7). To compound these difficulties, as many as 28 per cent of young women are married as children in South Asia and three in four child brides give birth while they are still adolescents, with these girls experiencing compromised agency and increased risks to birth outcomes and for their own nutrition (2, 8).

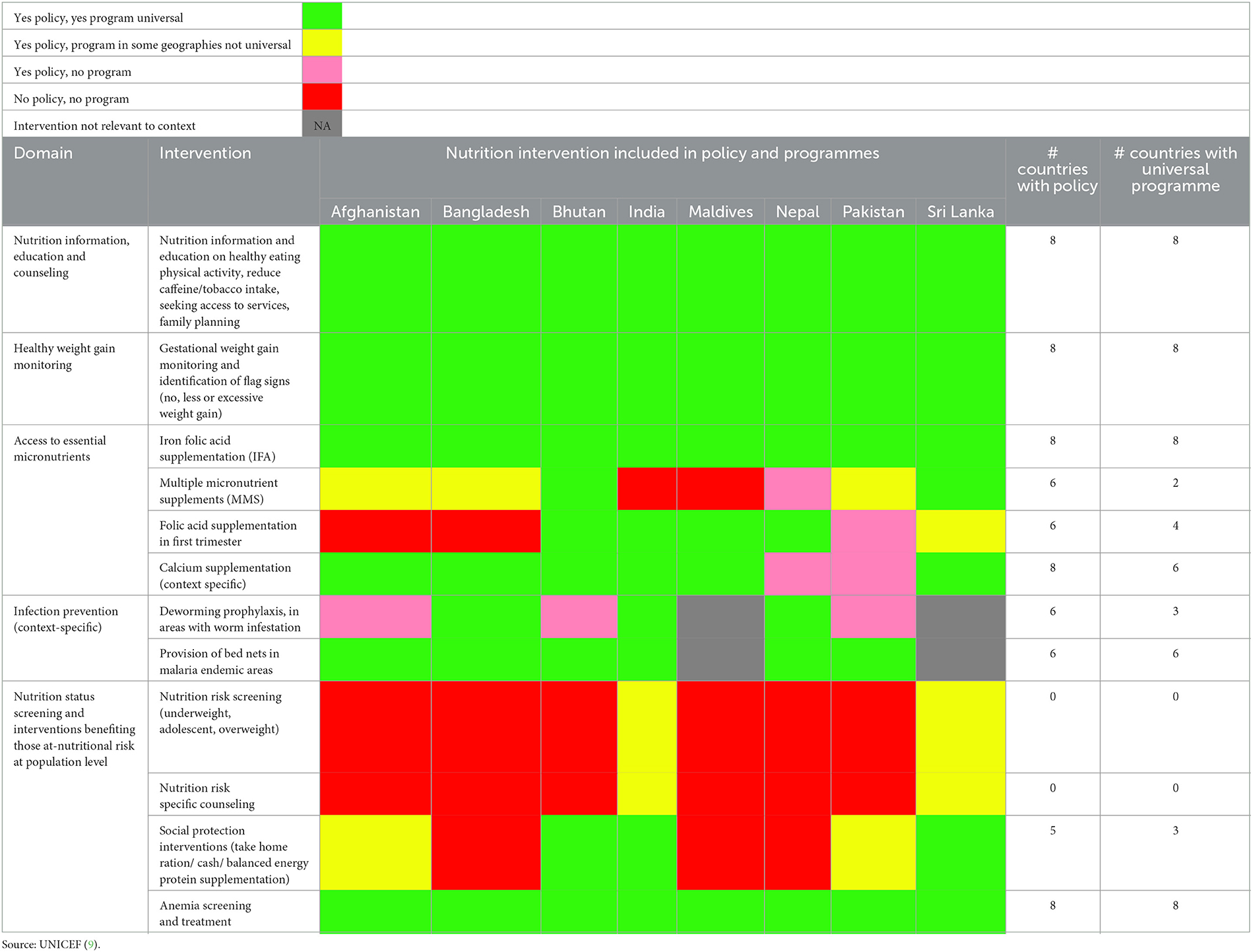

To achieve the goal of ensuring women have access to nutritious diets, nutrition services and positive nutrition practices, programmes should include a package of five essential nutrition actions: (i) access to fortified nutritious foods; (ii) micronutrient supplementation; (iii) nutrition information, education and counseling; (iv) safeguards against infections; and (v) healthy weight gain monitoring, nutrition risk screening and services for those most at-nutritional-risk at individual and population levels (cash, food vouchers, food rations and balanced energy and protein supplements). While most countries in the region do have strong policy and programme frameworks for delivering nutrition actions for pregnancy (Table 1), effective coverage of programmes remains low. About one in three women and girls in South Asia do not receive an antenatal check-up in the first trimester and in most countries in the region < 50% of women consume iron supplementation for at least 90 days of their pregnancy (9). Existing maternal service delivery platforms have programmatic challenges that constrain the availability of essential maternal nutrition services. To name but a few: (1) Priority is still accorded to reducing maternal mortality and not morbidity. Focus remains on delivering interventions to reduce child mortality and severe maternal anemia, but not on maternal morbidity or services available at women's life stages beyond pregnancy. (2) A lack of operational know-how on enacting time-efficient workflows to deliver all constituents of nutrition services at maternal and child contact points (10). (3) A cadre of trainers who understand nutrition and dietetics to support the maternal nutrition component of medical training is missing. (4) When nurses' and health providers' training takes place, the nutrition component is often weak or neglected (11). (5) Women who are thin, short, anemic, obese or with depression require “extra care” (12, 13) but this is often absent due to a lack of localized operational guidance for screening and management (10). At the planning level, there are opportunity gaps in including essential nutrition items (supplies, training, human resources, cadre, monitoring and research) in sectoral plans and budgets and missed opportunities to integrate height-weight gain monitoring, nutrition screening, macro and micronutrient supplementation, counseling and special care for nutritional risks for women into the same platforms that also reach children (14, 15). (7) Finally, despite increased attention to the need to address preconception nutrition, this is rarely provided owing to a lack of robust delivery platforms or large-scale implementation exemplars to provide the resources and programmatic know-how to cater for a large population in need.

Table 1. Availability of policies and programmes for delivering essential nutrition actions in pregnancy across South Asia.

To accelerate improvements in maternal nutrition—before, during and after pregnancy—the United Nations Children's Fund Regional Office for South Asia convened a regional conference on “Nourishing South Asia: Scaling-up equitable nutritional care for girls and women in South Asia,” from 18–20 September 2023 in Kathmandu, Nepal (16). The conference brought together 120 stakeholders from the eight countries that encompass the South Asia region (Afghanistan, Bhutan, Maldives, Bangladesh, Nepal, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) to take stock of countries' progress against regional commitments made in 2018 and discuss challenges and shifts needed to accelerate this progress. Details of the conference methodology have been described elsewhere (17). Briefly, the participants included senior government policy decision-makers, researchers, implementation champions, jurists, United Nations partners and development partners working on adolescent and women's nutrition (country delegations size was 6–16 per country). The conference format included 16 oral presentations, two panel discussions, a marketplace with 22 posters from the eight countries showcasing on-ground experiences and open space technology-based participatory group discussions. Each country delegations used open space methodology (18) methodology to discuss existing policies and programmes against each of the five essential nutrition actions. For those interventions which had a policy and programme, using a rubric provided (Supplementary File 1a) the country delegations identified systems bottlenecks in programme delivery, which have been described in Supplementary Files 1b–d; identified priority country actions and framework for action, which was consolidated into a call to action, which has been described below.

2023 regional call for five actions for improving maternal nutrition

Develop national plans with commensurate budgetary allocations

These plans and budgets should be developed with clear targets to foster acceleration and guarantee delivery and coverage of a package of essential nutrition actions for adolescent girls and women—before, during and after pregnancy. Investments will be needed from multiple sectors, especially education, health, social protection and food systems. There is a need to increase investments to improve food environments in order to protect women from nutrient-poor and unhealthy ultra-processed foods and beverages and curb the rise in overweight and obesity. Plans should account for the differential strategies needed to reach the most marginalized communities, for example by increasing the reach of social safety nets through food assistance, cash transfers and maternity benefits which target economically vulnerable women.

Implement solutions that are not “to” women but “through and for” women

Leveraging women's movements and coalitions will enhance the visibility of women's nutrition rights within the broader women's rights agenda. This will include accelerating multi-sector actions that address the harmful gender and social norms that underlie maternal malnutrition and especially target those that work toward keeping girls in school, delay age at marriage and strengthen family planning (to delay age at first pregnancy and reduce the number of pregnancies).

Review and update service delivery intervention packages and toolkits to ensure comprehensiveness and alignment with global guidelines/recommendations to address all forms of malnutrition

Service delivery implementation strategies should be periodically reviewed and refined by incorporating learning from systems bottleneck analyses and systems research on “what works” at scale. Introducing innovative products with proven effectiveness such as Multiple Micronutrient Supplements (MMS) and delivering them at-scale within routine government systems offers one path to success in addressing the high burden of micronutrient deficiencies in pregnancy (19). To enhance the impact of these programmes, it would also be useful to design, develop and implement a minimum nutrition package for preconception care and women's health before, between and beyond pregnancies, delivered through maternal health, family planning and women empowerment platforms using available evidence and learnings from the region (20–22).

Be intentional in scaling up efforts to address social and geographical inequalities that slow progress in nutrition, especially among girls and women living in the most challenging circumstances

This would entail identifying and working to close service delivery gaps, particularly at the subnational level. Extra attention and targeted nutrition action should be provided to reach malnourished adolescent girls and women who are at economic, social or geographic disadvantage. Social enterprises offer many opportunities to narrow inequities in nutrition outcomes by leveraging research and development capabilities, infrastructure, and capital from the private sector, reaching those consumer segments that could afford to buy low-cost products or services and cross-subsidizing products and services for nutrition by generating surplus from for-profit activities (23). e.g., women-led social enterprises in Afghanistan, India, Bangladesh and Nepal have worked to link “field to plate.” Setting up micro-enterprises, establishing market linkage and food fortification and processing units, community cooking, and creating grain and seed banks. These approaches aim to enhance livelihoods, agricultural practices, and household food security. They have undertake activities to establish private clinics to provide primary healthcare support to women as their right (23, 24). In humanitarian settings, creating friendly spaces for girls and women may offer the best entry point for integrated programming, particularly in contexts where movements are restricted, and girls and women are confined to their homes (25).

Invest in knowledge—data and systems research, alliances and cross-border sharing

This would entail strengthening survey data systems and routine programme monitoring systems to close data gaps and improve the quality and timeliness of data for tracking nutritional status and the coverage of interventions. Promoting transparency in how this data is used and disseminated will further ensure that progress in implementation of strategies are both accessible and accountable to the communities they aim to serve. Strengthening academic–government collaboration in evidence-based policymaking and promoting exchange of knowledge and experience both within and between countries in South Asia can be implemented to foster support networks and a culture of cross-learning within the region to improve girls' and women's nutrition.

A year since the 2023 call to action

Each country identified their priority action(s) during the 2023 regional conference (17). UNCEF country offices with other development partners have been supporting national/sub-national governments to mobilize the required political, technical, and financial commitments to execute priority actions identified in regional conference (Supplementary Files 1c, d) through acceleration plans/strategies. In September, 2024—a year since the conference- UNICEF released a stock-take report—Progress and Promise: Nourishing girls and women in South Asia (26) to capture nineteen examples of on-ground implementation since the call to action. These examples serve as testimony to the ongoing efforts across the region to improve access to essential nutrition actions for accelerating maternal nutrition. Briefly, six countries in region have initiated integration of preventive multiple micronutrient supplementation in antenatal care (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal and Sri Lanka). Afghanistan and Pakistan have initiated cash transfer to women leveraging poverty alleviation platforms. Indian state of Maharashtra and Srilanka have strengthened and scaled-up preconception care programmes.

On-ground implementation was further propelled through launch of global maternal nutrition acceleration plan with assured financing through child nutrition matched fund (19) for 15 countries globally, which include five countries from South Asia.

Conclusion

South Asia remains the make-or-break region to turn around the global nutrition crises affecting girls and women and accelerate progress on the 2030 SDG nutrition targets. We urge governments in the region and their development partners to respond to the call to action and put “women at the centre” of convergent multi-sector nutrition solutions. Countries should seize the opportunity to tailor programmes to manage different nutritional risks, strengthen their focus on integrating preconception nutrition into maternal nutrition programmes, and address the gender inequalities that prevent women accessing nutritious diets, nutrition services and positive practices. Improving girls and women's nutrition is critical for accelerating progress on all SDG nutrition targets. We must not wait for another call to action to state once again what has already been asserted this decade—tackling women's malnutrition matters for nourishing South Asia!

Author contributions

VS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number UNICEF RISING 2.0 Nutrition Anchor Grant INV-042828).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1498171/full#supplementary-material

References

1. FAO IFAD UNICEF WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 – Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. Rome: FAO (2024). doi: 10.4060/cd1254en

2. United Nations Children's Fund. Undernourished and Overlooked: A Global Nutrition Crisis in Adolescent Girls and Women. UNICEF Child Nutrition Report Series (2023). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/136876/file/Full%20report%20(English).pdf

3. Yajnik C. Early life origins of the epidemic of the double burden of malnutrition: life can only be understood backwards. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. (2024) 28:100453. doi: 10.1016/j.lansea.2024.100453

4. United Nations Children's Fund. UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia- Stop stunting: power of maternal nutrition - conference report. (2018). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/7701/file/%20Stop%20Stunting%20-%20Power%20of%20Maternal%20Nutrition.%20Conference%20Report.pdf.pdf

5. Murira Z, Torlesse H. Unlocking the power of maternal nutrition to improve nutritional care of women in South Asia. Emerg Nutr Netw Nutr Exch South Asia. (2019) 1:4–5.

6. Rao N. The achievement of food and nutrition security in South Asia is deeply gendered. Nat Food. (2020) 1:206–9. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0059-0

7. Chaudhuri S, Roy M, McDonald LM, Emendack L. Coping behaviours and the concept of time poverty: a review of perceived social and health outcomes of food insecurity on women and children. Food Sec. (2021) 13:1049–68. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01171-x

8. United Nations Children's Fund. 10 million additional girls at risk of child marriage due to COVID-19. (2021). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/eap/press-releases/10-million-additional-girls-risk-child-marriage-due-covid-19-unicef

9. United Nations Children's Fund. UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia Progress in Improving Nutritional Care for Girls and Women 15-49 Years, Factsheet 2023b. Paris: UNICEF (2023).

10. Sethi V, Mishra A, Ahirwar KS, Singh AP, Pawar S, Awasthy P, et al. Integrating an algorithmic and health systems thinking approach to improve the uptake of government antenatal nutrition services in Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh (India), 2018 to 2021. Health Policy Plan. (2023) 38:454–63. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czad011

11. Dimaria-Ghalili RA, Edwards M, Friedman G, Jaferi A, Kohlmeier M, Kris-Etherton P, et al. Capacity building in nutrition science: revisiting the curricula for medical professionals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2013) 1306:21–40. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12334

12. Higgins A, Downes C, Monahan M, Gill A, Lamb SA, Carroll M, et al. Barriers to midwives and nurses addressing mental health issues with women during the perinatal period: the mind mothers study. J Clin Nurs. (2018) 27:1872–83. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14252

13. Lawrence W, Vogel C, Strömmer S, Morris T, Treadgold B, Watson D, et al. How can we best use opportunities provided by routine maternity care to engage women in improving their diets and health? Matern Child Nutr. (2020) 16:e12900. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12900

14. Choedon T, Dinachandra K, Sethi V, Kumar P. Screening and management of maternal malnutrition in nutritional rehabilitation centers as a routine service: a feasibility study in Kalawati Saran Children Hospital, New Delhi. Indian J Community Med. (2021) 46:241–6.

15. Saini A, Shukla R, Joe W, Kapur A. Improving nutrition budgeting in health sector plans: evidence from India's anaemia control strategy. Matern Child Nutr. (2022) 18:e13253. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13253

16. United Nations Children's Fund. UNICEF calls for more investment as South Asia remains global epicentre for undernourished and anaemic adolescent girls and women. (2023). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/press-releases/unicef-calls-more-investment-south-asia-remains-global-epicentre-undernourished-and

17. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Regional Conference on Nourishing South Asia: Scaling-up Equitable Nutritional Care for Girls and Women in South Asia, 18–20 September 2023, Kathmandu, Nepal – Summary of conference deliberations. (2024). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/29611/file/Conference%20Report.pdf.pdf

19. United Nations Children's Fund. Improving maternal nutrition: an acceleration plan to prevent malnutrition and anaemia during pregnancy (2024–2025). (2024). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/maternal-nutrition-acceleration-plan

20. Nilaweera I, Rowel D, Hemachandra N, Abdulloeva S, Mapitigama N. Delivering care to address a double burden of maternal malnutrition in Srilanka. Emerg Nutr Netw Nutr Exch South Asia. (2019) 1:17–9.

21. Taneja S, Chowdhury R, Dhabhai N, Upadhyay RP, Mazumder S, Sharma S, et al. Impact of a package of health, nutrition, psychosocial support, and WaSH interventions delivered during preconception, pregnancy, and early childhood periods on birth outcomes and linear growth at 24 months of age: factorial, individually randomised controlled trial. BMJ. (2022) 379:e072046. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072046

22. Kumar A, Sethi V, Wagt A, Parhi RN, Bhattacharjee S, Unisa S, et al. Evaluation of impact of engaging federations of women groups to improve women's nutrition interventions- before, during and after pregnancy in social and economically backward geographies: evidence from three eastern Indian States. PLoS ONE. (2023) 18:e0291866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0291866

23. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Harnessing Women's Groups and Movements across South Asia to Advance Women's Nutrition Rights, UNICEF Nourishing South Asia Reports, Issue 2, UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia, Kathmandu. (2024). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/29046/file/2.%20NSR%20Issue%202%20-%20women%20groups%20.pdf.pdf

24. Ojong SA, Temmerman M, Khosla R, Bustreo F. Women's health and rights in the twenty-first century. Nat Med. (2024) 30:1547–55. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03036-0

25. UK Aid. Afghanistan - girls' education challenge. (2022). Available at: https://girlseducationchallenge.org/countries/country/afghanistan

26. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Progress and Promise: Nourishing Girls and Women in South Asia UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia Kathmandu 2024. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/29601/file/%20Progress%20and%20promise%20report.pdf.pdf

Keywords: maternal nutrition, South Asia, women's nutrition, adolescent nutrition, Malnutrition, call to action

Citation: Sethi V and Murira Z (2025) Galvanizing and sustaining momentum are critical to improve maternal nutrition in South Asia. Front. Nutr. 12:1498171. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1498171

Received: 18 September 2024; Accepted: 13 January 2025;

Published: 31 January 2025.

Edited by:

Roberto Fernandes Da Costa, Autonomous University of Chile, ChileReviewed by:

Emanuel Orozco, National Institute of Public Health, MexicoHélène Delisle, Montreal University, Canada

Copyright © 2025 Sethi and Murira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vani Sethi, dnNldGhpQHVuaWNlZi5vcmc=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Vani Sethi

Vani Sethi Zivai Murira

Zivai Murira