- Center for Science in the Public Interest, Washington, DC, United States

The internet is drastically changing how U.S. consumers shop for groceries, order food from restaurants, and interact with food marketing. There is an urgent need for new policies to help ensure that the internet is a force for good when it comes to food access, transparency, and nutrition. This article outlines actions that federal agencies—like the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Federal Trade Commission (FTC)—and state and local governments can take to improve the online food environment. We recommend policies in three settings: online grocery retail, online restaurant ordering, and marketing on social media and other online platforms. For example, USDA could finalize regulations increasing access to online WIC and remove barriers to accessing online SNAP by requiring large retailers to waive online delivery and service fees for SNAP purchases. FDA could improve access to nutrition information by issuing guidance describing what product information should be available at the online point of selection. FTC could give better guidance on appropriate tactics when marketing to children and collect better data on how companies are marketing food to children online. Finally, state governments could pass laws like New York’s recently introduced Predatory Marketing Prevention Act to address false and misleading advertising of unhealthy foods aimed at children and other vulnerable groups.

Introduction

The internet is drastically changing how U.S. consumers shop for groceries, order food from restaurants, and interact with food marketing. Nearly one in five U.S. consumers buys groceries online at least once per month (1). Two-thirds of restaurant sales are generated by orders placed online or by phone (2). Half of consumers (51%) say third-party apps are their preferred way to browse for food, and 86% order on third-party apps at least twice a month (3).

Online ordering and delivery present new opportunities to expand food access. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, an online purchasing pilot allowing consumers with low-incomes to use Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits for online grocery shopping in several states led to an 8% reduction in the prevalence of food insufficiency (4).

However, the online food environment also presents new challenges for supporting consumers in making informed, healthy choices. Online food shoppers lack consistent access to the same product information as in-store shoppers (5, 6) and face an onslaught of marketing messages, often aimed at luring them to purchase less healthy products (7). Food companies also advertise through social media (8) and other online settings like children’s educational websites (9), often targeting children who are particularly vulnerable to such marketing (10).

There is an urgent need for new policies to help ensure the internet is a force for good. Many U.S. food laws were written before the internet and are an uneasy fit for the digital age. While Congress can pass new legislation to improve the online food environment, existing laws give ample authority for federal regulators—like the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Federal Trade Commission (FTC)—to adapt old laws to new environments. The Supreme Court recently struck down the Chevron judicial doctrine (11), denying any special deference to agencies in interpreting their own statutes, and expanded the “major questions” doctrine (12), preventing agencies from taking new actions of “vast economic and political significance” without clear direction from Congress. But federal regulators still have the ability to apply existing laws to emerging industries. State and local governments can also adopt policies to strengthen consumer protections when federal law does not preempt such policies.

This article presents legally feasible policy opportunities to promote food access, transparency and fairness, and nutrition in three settings: online grocery retail, online restaurant ordering, and marketing on social media and other online platforms.

Online grocery retail

Online grocery shopping could improve food access, especially for the 40 million Americans living in areas with low income and low food access (13). The brick-and-mortar retail environment could still be improved to promote healthy foods, but healthy choices are even less clear in online grocery retail. Nutrition information can be hard to find for food sold online (5). Further, food and beverage manufacturers pay grocery stores large amounts of money to promote and place predominantly unhealthy products in prominent store locations (14), both in store (15) and online (16).

Increasing food access

In 2023, 42.2 million Americans participated in SNAP (17) and another 6.6 million participated in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) (18). These essential USDA programs support healthy food access for people with low incomes. The option of using SNAP and WIC benefits online further facilitates food access and offers program participants an equitable shopping experience. It’s a particularly important option for people who live in urban and rural food deserts (19), are immunocompromised, have mobility limitations, lack access to or funds for transportation, or are single parents.

Online SNAP purchasing is now available in all 50 states and Washington D.C. (20). In April 2023, 3.7 million households shopped online using SNAP. However, SNAP participants cite delivery and service fees as a barrier to utilizing their benefits online (21). USDA should consider reimbursing smaller, independent retailers for online delivery and service fees and requiring larger retailers to waive these fees for SNAP purchases.

Unlike online SNAP, online WIC purchasing is not yet widely available, but it would be especially beneficial because pregnancy and small children introduce challenges for in-person shopping. Current program rules technically prohibit using WIC benefits online (22), although the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act granted USDA authority to issue waivers relaxing these regulations, allowing funding for 7 states and one tribe to implement WIC online purchasing pilots (23). USDA should finalize its proposed rule from February 2023 that would modernize WIC to allow for online ordering in all states (24).

Increasing information access

Currently, information required on food packaging to promote transparency and inform consumers’ choices is not always available to online shoppers. Even when available, it can be difficult to read, hard to find, incomplete, or inaccurate (5). Absent or inaccurate information poses a particular risk to people with food allergies and those managing diet-related chronic conditions.

In April 2023, FDA issued a Request for Information regarding food labeling in online grocery shopping (25). Consumer health advocates asked FDA to encourage or require online food retailers to disclose key product information at the online point of sale and to provide specifications for format and accessibility (26). Industry stakeholders shared challenges facing the information supply chain, such as the lack of uniform standards for when, how, and to whom suppliers must provide new or updated product information and images when there are new products or changes to existing products’ labels or formulations, and when and how online sellers must update the information on their webpages.

To improve transparency and information access for online grocery shoppers, FDA and USDA should issue guidance encouraging online sellers to ensure that the same nutrition, ingredient, and allergen information available in stores is available, easy to find, and easy to read at the online point of sale. To address challenges facing the food industry in managing the transfer of food information, the guidance should establish best practices for how and when product information and images should be transmitted from manufacturer to retailer to consumer. It should also encourage product webpages to be configured with Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliance and accessibility in mind. Finally, it should encourage sellers of recently reformulated products with multiple formulations in commerce at the same time to alert consumers to this fact and provide consumers with product information for every version they might receive.

New federal legislation could mandate compliance with such guidance by all food sellers (27). However, to make online labeling mandatory for many retailers without new legislation, USDA could issue regulations making available, accessible online information a requirement for SNAP- and WIC-authorized online retailers. This would affect the majority of retailers, as about 257,000 U.S. food retailers (28) (84% of all U.S. food retailers) (29) accept SNAP. All online shoppers (those using SNAP benefits and other forms of payment) would have increased access to information. To support retailers, USDA should assist with data management and webpage updates through the SNAP EBT Modernization Technical Assistance Center (30).

Encouraging healthy choices

There are numerous policies underway aimed at supporting consumers in making healthier choices at the grocery store. These policies must consider both in-store and online settings. One example is FDA’s proposed regulation establishing a mandatory, standardized front-of-package nutrition labeling (FOPNL) system to help consumers, particularly those with lower nutrition knowledge, quickly and easily identify foods that can help them build a healthy eating pattern (31). This policy initiative is described in detail elsewhere (31, 32). FDA’s regulations, or subsequent guidance, should specify that FOPNL should appear on all images of the product’s principal display panel displayed on product webpages.

Another example is state and local policies requiring healthy placement standards for food retail establishments to make it easier for customers and their children to avoid marketing and impulse purchases of drinks and snacks high in sugar and salt. Berkeley (33) and Perris (34), California have passed policies requiring all large retailers to place only healthy foods and beverages in checkout aisles. Similar future policies should specify how these requirements apply online and should also be considered at the federal level. To benefit consumers in all 50 states without necessitating federal legislation, USDA should consider establishing mandatory healthy food marketing and product placement standards for SNAP-authorized retailers (21). FTC should consider issuing guidance for retailers on how to place foods and beverages in the checkout aisle—including the virtual equivalent of the checkout aisle. The Farm Bill should authorize pilot projects to test and inform the implementation of such requirements for SNAP-authorized retailers.

Online restaurant ordering

Restaurant foods in the U.S. are often high in calories, sodium, and added sugars (35). FDA requires calorie disclosures on all menus from U.S. chain restaurants with 20 or more locations, Philadelphia requires sodium warnings on chain restaurant menu items that contain more than a day’s worth of sodium (2,300 milligrams), and New York City (NYC) requires those same sodium warnings plus warnings on chain restaurant menu items containing more than a day’s worth of added sugars (50 grams) (36–39). These labeling policies can improve the nutritional quality of food orders (40, 41) and encourage restaurants to sell healthier items (42). To have their full intended benefit, requirements for nutrition information and safety warnings must apply to menus regardless of where people view them, whether in a physical restaurant, on a website, or on a third-party ordering app.

Federal calorie labeling

FDA regulations explicitly apply menu labeling requirements to “menus on the Internet” (43). These regulations clearly cover menus on restaurants’ websites and mobile apps, but whether those same menus are still covered when they are posted or maintained by restaurants on third-party platforms (TPPs) has been a topic of debate. In 2023, FDA published a draft guidance stating that calorie labeling for menus on TPPs is voluntary, implying that such menus are exempt from federal menu labeling requirements (44). A coalition of consumer health organizations pushed back, filing a petition calling on FDA to make calorie labeling for menus on TPPs mandatory, not voluntary, in their final guidance and arguing that the agency has full authority to do so (45).

The argument over FDA authority amounts to a question of control. While TPPs themselves are not subject to FDA’s regulatory authority, FDA does have authority to regulate menus that are posted by restaurants covered under the federal menu labeling law. Therefore, advocates contend that FDA can require restaurants that post and control menus on TPPs to include calorie information. All major TPPs allow restaurants to upload and update their own menus on the platforms through merchant portals (45), plus Grubhub and DoorDash have stated that the majority of orders on their platforms come from partnered restaurants (i.e., restaurants that have agreed to partner with the TPP by posting and updating their menus using the merchant portal) (46). Thus, covered restaurants should be required to comply with calorie labeling when they post menus on a TPP, just as they must comply when they post menus on a proprietary website or mobile app.

Applying federal menu labeling requirements to menus on TPPs is essential for ensuring consistent calorie information access. While there is strong compliance with calorie disclosure requirements on printed menus and website menus (47), the prevalence of calorie labeling on TPPs is currently low (6). A 2022 study found at least one calorie disclosure on only 58% of menus on DoorDash, 51% of menus on Uber Eats, and 12% of menus on Grubhub (6).

To increase compliance with federal menu labeling requirements, FDA should issue final guidance clarifying that the requirements do apply to menus that covered restaurants post on TPPs.

State and local nutrient warnings

Similar to FDA’s calorie labeling regulations, local nutrient warning policies apply to menus on restaurant websites and mobile apps, but so far have not been interpreted to apply when those same menus are posted on TPPs. Philadelphia’s guidance to restaurants says sodium warning labels must appear on websites and mobile applications if the covered establishment takes orders using these methods, but they are “not required on third-party sites (e.g., Uber Eats, Caviar, Grubhub)” (48). NYC’s policy exempts “third party online ordering sites, such as Seamless or Grub Hub, because the companies operating these websites are not food service establishments with a Health Department permit” (37).

As additional policies are developed to warn consumers about menu items with extremely high levels of sodium and other nutrients like added sugars, they should include menus on TPPs. Furthermore, NYC and Philadelphia policymakers should encourage TPPs to provide the capability to add warnings beside menu items through their merchant portals and should encourage merchants to utilize this feature.

Marketing on social media and other online platforms

Children’s exposure to marketing via social media and other online platforms is concerning because food marketing exposure can impact children’s food preferences, choices, and intake (49), and their ability to understand the persuasive intent of advertising is not yet fully developed (10). Much of the food marketed to kids online is unhealthy. In one study, 72% of children and adolescents were exposed to food and beverage advertising on social media apps, and the most common exposures were to ads for fast-food restaurants, sugar-sweetened beverages, and candy and chocolate (50).

The FTC Act allows FTC to regulate unfair and deceptive business practices, including certain online marketing activities (51). FTC’s Endorsement Guides address unfair and deceptive advertising practices in advertisements containing endorsements, defined as “any advertising, marketing, or promotional message for a product that consumers are likely to believe reflects the opinions, beliefs, findings, or experiences of a party other than the sponsoring advertiser” (52), including—for example— social media posts from paid influencers. In 2023, FTC updated the Endorsement Guides to include a section titled “Endorsements Directed to Children,” which notes that practices that may be appropriate in content aimed at adult audiences may not be appropriate in content aimed at children (53). However, FTC does not provide practical advice for handling endorsements in content specifically aimed at children, stating only “Practices that would not ordinarily be questioned in advertisements addressed to adults might be questioned in such cases” (53). The agency should better protect children from unfair unhealthy food and beverage advertising online by providing more specific language on best practices for endorsement disclosure for advertisements aimed at children.

The FTC Act’s “6(b) authority” also empowers FTC to require businesses to file reports and answer questions about their business practices, and to publish wide-ranging agency studies based on such reports and information (54–56). FTC used its 6(b) authority to conduct investigations and publish reports on food industry expenditures on marketing to children in 2008 and 2012 (57, 58). These reports provided insight into companies’ spending on marketing to children, which products are most frequently advertised, and through which channels children are exposed to food advertising (57, 58). However, the most recent of these reports used data from 2009 (58). FTC should publish an updated food-marketing-to-kids report, paying special attention to digital marketing, including how companies may be disproportionately advertising to specific demographic groups and marketing on online learning platforms. This report would help inform regulatory, legislative, and industry self-regulatory activities.

Finally, state governments should leverage their consumer protection statutes and pass policies to strengthen them. For example, New York’s proposed Predatory Marketing Prevention Act would direct courts to consider the age of the target audience and other factors that might affect comprehension in determining when food marketing (which includes online marketing) is false or misleading, enhancing the state attorney general’s ability to prosecute companies for such predatory marketing (59).

Nutrition misinformation is another serious concern in the online food marketing environment. FDA and FTC have limited authority to address false and misleading statements that are not tied to the promotion of specific products or brands, but a clear step FTC can take to promote public trust in advertising is to take action more often against social media influencers who fail to disclose sponsored content. While such actions cannot eliminate misleading information from the internet, transparency regarding funding for endorsements helps consumers evaluate the trustworthiness of the message. In 2023, the agency sent warning letters to the American Beverage Association, Canadian Sugar Institute, and 12 nutrition influencers for failing to employ required disclosures on paid advertisements that promoted the safety of aspartame and sugary products (60). FTC should continue to monitor and take action against such violations and establish a means for the public to easily report known or suspected violations.

Discussion

As the online food environment becomes increasingly influential in guiding consumers’ access to food and information, federal regulators and state and local lawmakers should take advantage of the many policy opportunities to promote food access, transparency, and healthy choices through online food sales and marketing.

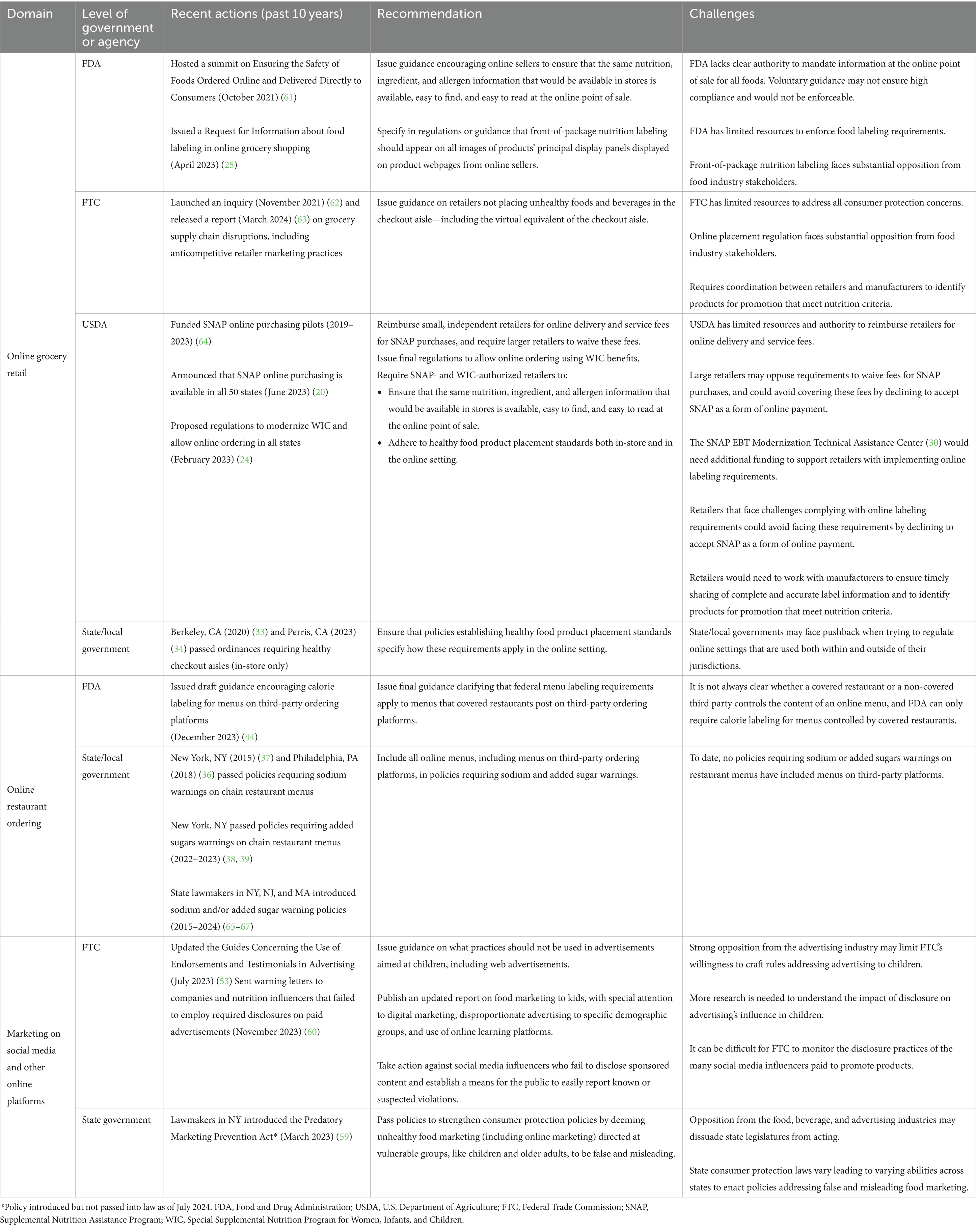

In doing so, policymakers must consider the challenges and potential unintended consequences of implementing new policies (see Table 1).

Table 1. Recent actions and policy recommendations to promote food access, transparency, and healthy food choices online.

FDA and FTC have limited resources for policy enforcement. State and local governments may face pushback when adopting policies that apply to online settings accessed from both within and outside of their jurisdictions. Retailers could decide not to accept online SNAP payments to avoid complying with labeling and marketing requirements tied to online SNAP, thus negating recent improvements in food access from online SNAP expansion. New food labeling and marketing requirements often face opposition from the food industry, including threats to increase food prices. And policies restricting food marketing to kids online must contend with privacy concerns, such as balancing the need to know the age of users with the risks of collecting personal information. Fortunately, these challenges are not insurmountable and policies can be creatively and flexibly designed to avoid such unintended consequences.

Future research should explore policies outside the scope of this article but related to consumer protection in the online food environment, including those seeking to decrease prices of food sold online (e.g., commission fee caps and price discrimination), improve wages and workplace protections for food delivery workers, increase food safety (e.g., safe handling protocols for delivery drivers and bikers), and ensure data privacy and security (e.g., protection of user data and prohibition of unfair ad targeting based on factors such as SNAP status or age).

The online food environment presents myriad challenges and opportunities for improving food access, transparency, and nutrition. Federal, state, and local policymakers must meet the moment and ensure adequate regulation of online spaces to support consumers in making informed, healthy choices.

Author contributions

EG: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft. KM: Writing – original draft. EF: Writing – original draft. SJ: Writing – review & editing. JJ: Writing – review & editing. CL: Writing – review & editing. DN: Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing. KG: Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors declare financial support from Bloomberg Philanthropies (Grant ID: 71208, www.bloomberg.org) and the John Sperling Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Restrepo, BJ, and Zeballos, E. New survey data show online grocery shopping prevalence and frequency in the United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; February 8, 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2024/february/new-survey-data-show-online-grocery-shopping-prevalence-and-frequency-in-the-united-states/

2. Convenience Store News. Remote food orders are now restaurants’ primary source of revenue. Available at: https://csnews.com/remote-food-orders-are-now-restaurants-primary-source-revenue (Accessed June 25, 2024).

3. DoorDash Merchant Blog. (2024). Consumer trends in Restaurant & Alcohol Delivery. Published May 14, 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://get.doordash.com/en-us/blog/online-ordering-habits.

4. Jones, K, Leschewski, A, Jones, J, and Melo, G. The supplemental nutrition assistance program online purchasing Pilot’s impact on food insufficiency. Food Policy. (2023) 121:102538. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2023.102538

5. Pomeranz, JL, Cash, SB, Springer, M, Del Giudice, IM, and Mozaffarian, D. Opportunities to address the failure of online food retailers to ensure access to required food labelling information in the USA. Public Health Nutr. (2022) 25:1375–83. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021004638

6. Greenthal, E, Sorscher, S, Pomeranz, JL, and Cash, SB. Availability of calorie information on online menus from chain restaurants in the USA: current prevalence and legal landscape. Public Health Nutr. (2023) 26:3239–46. doi: 10.1017/S1368980023001799

7. McCarthy, J, Minovi, D, and Wootan, MG. Scroll and Shop: Food Marketing Migrates Online. Center for Science in the Public Interest; January 2020. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.cspinet.org/resource/report-scroll-and-shop

8. Brooks, R, Christidis, R, Carah, N, Kelly, B, Martino, F, and Backholer, K. Turning users into 'unofficial brand ambassadors': marketing of unhealthy food and non-alcoholic beverages on TikTok. BMJ Glob Health. (2022) 7:9112. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009112

9. Emond, JA, Fleming-Milici, F, McCarthy, J, Ribakove, S, Chester, J, Golin, J, et al. Unhealthy food marketing on commercial educational websites: remote learning and gaps in regulation. Am J Prev Med. (2021) 60:587–91. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.10.008

10. Packer, J, Croker, H, Goddings, AL, Boyland, EJ, Stansfield, C, Russell, SJ, et al. Advertising and young People's critical reasoning abilities: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. (2022) 150:e2022057780. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057780

13. Rhone, A, Williams, R, and Dicken, C. Low-income and low-Foodstore-access census tracts, 2015–19. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service Published June 2022. Accessed July 9, 2024. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=104157

14. Rivlin, G. Rigged: Supermarket Shelves for Sale. (2016). Available at: https://www.cspinet.org/resource/rigged

15. Petimar, J, Moran, AJ, Grummon, AH, Anderson, E, Lurie, P, John, S, et al. In-store marketing and supermarket purchases: associations overall and by transaction SNAP status. Am J Prev Med. (2023) 65:587–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.02.029

16. Moran, AJ, Headrick, G, Perez, C, Greatsinger, A, Taillie, LS, Zatz, L, et al. Food marketing practices of major online grocery retailers in the United States, 2019-2020. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2022) 122:2295–2310.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2022.04.003

17. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Costs Published May 10, 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-annualsummary-5.pdf

18. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. WIC Program Participation and Costs Published May 10, 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/wisummary-5.pdf

19. Brandt, EJ, Silvestri, DM, Mande, JR, Holland, ML, and Ross, JS. Availability of grocery delivery to food deserts in states participating in the online purchase pilot. JAMA Netw Open. (2019) 2:e1916444. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16444

20. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. USDA Celebrates SNAP Online Purchasing Now Available in All 50 States Published June 9, 2023. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/news-item/fns-010.23

21. John, S, Johnson, J, Nelms, A, Bresnahan, C, Tucker, AC, and Wolfson, JA. Recommendations to promote healthy retail food environments: key Federal Policy Opportunities for the farm bill. Center for Science in the Public Interest;(2023). Available at: https://www.cspinet.org/resource/report-title-recommendations-promote-healthy-retail-food-environments

22. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. Task Force on Supplemental Food Delivery in the WIC Program—Recommendations Report, (2021). Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/food-delivery-task-force-recommendations-report

23. Center for Nutrition and Health Impact. Online shopping projects. WICShop+ Published (2024). Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.wicshopplus.org/projects

24. 88 Fed. Reg. 11516. Special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children (WIC): online ordering and transactions and food delivery revisions to meet the needs of a modern, data-driven program. (2023). Federal Register, the Daily Journal of the United States Government.

25. 88 Fed. Reg. 24808. Food labeling in online grocery shopping; request for information. (2023). Federal Register, the Daily Journal of the United States Government.

26. Center for Science in the Public Interest. Comment on request for information re: food labeling in online grocery shopping. Published, (2023). Available at: https://www.cspinet.org/resource/comment-request-information-re-food-labeling-online-grocery-shopping

28. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. SNAP Retailer: Getting Started Published June 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/retailer.

29. Primary analysis of data from U.S. Census Bureau 2021 CBP and NES Combined Report (https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/econ/nonemployer-statistics/2021-combined-report.html) and County Business Patterns: 2021 (https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2021/econ/cbp/2021-cbp.html).

30. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. SNAP EBT modernization technical assistance center (SEMTAC). Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/grant/snap-ebt-modernization-technical-assistance-center

31. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Front-of-package nutrition labeling. Published April 30, 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/front-package-nutrition-labeling

32. Center for Science in the Public Interest. Petition to FDA asking for mandatory front-of-package nutrition labels. Available at: https://www.cspinet.org/resource/petition-fda-asking-mandatory-front-package-nutrition-labels

35. Vercammen, KA, Frelier, JM, Moran, AJ, Dunn, CG, Musicus, AA, Wolfson, JA, et al. Calorie and nutrient profile of combination meals at U.S. fast food and fast casual restaurants. Am J Prev Med. (2019) 57:e77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.008

36. City of Philadelphia Department of Public Health. New sodium warning labels coming to Philadelphia chain restaurants. City of Philadelphia. Published September 17, 2019. (Accessed June 25, 2024). Available at: https://www.phila.gov/2019-09-17-new-sodium-warning-labels-coming-to-philadelphia-chain-restaurants/.

37. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. New sodium (salt) warning rule: what food service establishments need to know. Published (2023). Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/cardio/sodium-warning-rule.pdf

40. Crockett, RA, King, SE, Marteau, TM, Prevost, AT, Bignardi, G, Roberts, NW, et al. Nutritional labelling for healthier food or non-alcoholic drink purchasing and consumption. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 2:Cd009315. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009315.pub2

41. Petimar, J, Zhang, F, Cleveland, LP, Simon, D, Gortmaker, SL, Polacsek, M, et al. Estimating the effect of calorie menu labeling on calories purchased in a large restaurant franchise in the southern United States: quasi-experimental study. BMJ. (2019) 367:l5837. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5837

42. Grummon, AH, Petimar, J, Soto, MJ, Bleich, SN, Simon, D, Cleveland, LP, et al. Changes in calorie content of menu items at large chain restaurants after implementation of calorie labels. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2141353. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.41353

44. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry: menu labeling supplemental guidance (edition 2). Published December 2023. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/draft-guidance-industry-menu-labeling-supplemental-guidance-edition-2.

45. Center for Science in the Public Interest. Citizen petition for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to issue final guidance requiring covered establishments that post and/or maintain menus on third-party platforms to include calories and additional nutrition labeling, (2024). Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://www.cspinet.org/resource/petition-fda-issue-final-guidance-requiring-covered-establishments-include-calories-and

46. Dawson, G. What to do if your restaurant is listed on a third-party marketplace without your permission. Nation’s Restaurant News February 2, (2020). Available at: https://www.nrn.com/technology/what-do-if-your-restaurant-listed-thirdparty-marketplace-without-your-permission

47. Cleveland, LP, Simon, D, and Block, JP. Federal calorie labelling compliance at US chain restaurants. Obes Sci Pract. (2020) 6:207–14. doi: 10.1002/osp4.400

48. Food Fit Philly. Understanding Philadelphia’s sodium warning law: what chains need to know. Published may 28, 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. Available at: https://foodfitphilly.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Sodium-warning-label-admin-guidance-document-rev-2024.pdf

49. Boyland, E, McGale, L, Maden, M, Hounsome, J, Boland, A, Angus, K, et al. Association of Food and Nonalcoholic Beverage Marketing with Children and Adolescents' eating behaviors and health: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. (2022) 176:e221037. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.1037

50. Potvin Kent, M, Pauze, E, Roy, EA, de Billy, N, and Czoli, C. Children and adolescents' exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatr Obes. (2019) 14:e12508. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12508

52. 16 C.F.R. § 255. Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising. United States Code of Federal Regulations.

53. 88 Fed. Reg. 48102. Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising. (2023). Federal Register, the Daily Journal of the United States Government.

56. Federal Trade Commission. A brief overview of the Federal Trade Commission’s investigative, law enforcement, and rulemaking authority. (2021). Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/about-ftc/mission/enforcement-authority

57. Federal Trade Commission. Marketing food to children and adolescents: a review of industry expenditures, activities, and self-regulation: a Federal Trade Commission Report to congress. (2008). Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/reports/marketing-food-children-adolescents-review-industry-expenditures-activities-self-regulation-federal

58. Federal Trade Commission. Review of food marketing to children and adolescents – follow up report. (2012). Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/reports/review-food-marketing-children-adolescents-follow-report

59. New York State Senate Bill 2023-S213B. An act to amend the agriculture and markets law, the general business law and the public health law, in relation to food and food product advertising (2023).

60. Federal Trade Commission. FTC warns two trade associations and a dozen influencers about social media posts promoting consumption of aspartame or sugar. (2023). Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/11/ftc-warns-two-trade-associations-dozen-influencers-about-social-media-posts-promoting-consumption

61. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. New era of smarter food safety summit on E-commerce: ensuring the safety of foods ordered online and delivered directly to consumers. (2021). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/workshops-meetings-webinars-food-and-dietary-supplements/new-era-smarter-food-safety-summit-e-commerce-ensuring-safety-foods-ordered-online-and-delivered

62. Federal Trade Commission. FTC launches inquiry into supply chain disruptions. (2021). Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2021/11/ftc-launches-inquiry-supply-chain-disruptions

63. Federal Trade Commission. Feeding America in a time of crisis: FTC staff report on the United States grocery supply chain and the COVID-19 pandemic. (2024). Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/reports/feeding-america-time-crisis-ftc-staff-report-united-states-grocery-supply-chain-covid-19-pandemic.

64. U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot (n.d.) Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/online

65. New York State Bills A8266 (2015-2016), A4534 (2017-2018), A3871 (2019-2020), A8860 (2021-2022), A6529/S213B (2023-2024). An act to amend the public health law, in relation to requiring chain restaurants to label menu items that have a high content of sodium (2023).

66. New Jersey State Assembly Bill A1429. An Act concerning retail food establishments and supplementing Title 26 of the Revised Statutes (2022).

67. Legis, MA. S.1396/H.2210 (2023-2024). An Act to Protect Youth from the Health Risks of Sugary Drinks. Massachusetts state legislature. Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Bills/193/H2210

Keywords: food environment, food policy, food access, food labeling, food marketing, nutrition, online food retail, online food delivery

Citation: Greenthal E, Marx K, Friedman E, John S, Johnson J, LiPuma C, Nara D, Sorscher S, Gardner K and Musicus A (2024) Navigating the online food environment: policy pathways for promoting food access, transparency, and healthy food choices online. Front. Nutr. 11:1473303. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1473303

Edited by:

Wenhui Feng, Tufts University, United StatesReviewed by:

Anna Kiss, University of Szeged, HungaryCopyright © 2024 Greenthal, Marx, Friedman, John, Johnson, LiPuma, Nara, Sorscher, Gardner and Musicus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eva Greenthal, ZWdyZWVudGhhbEBjc3BpbmV0Lm9yZw==

Eva Greenthal

Eva Greenthal Katherine Marx

Katherine Marx Emily Friedman

Emily Friedman